Validating Plant Disease Resistance Gene Function: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Genomic Tools

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on the validation of plant disease resistance (R) gene function.

Validating Plant Disease Resistance Gene Function: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Genomic Tools

Abstract

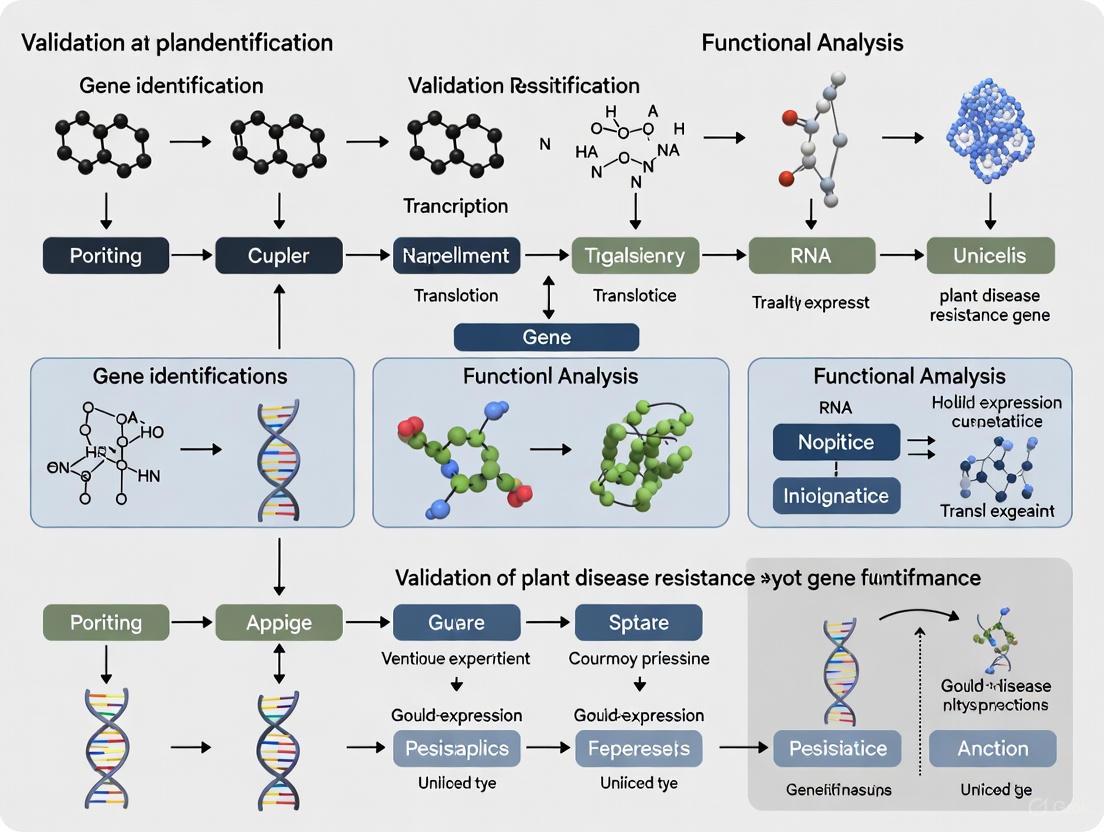

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on the validation of plant disease resistance (R) gene function. It covers the foundational principles of plant immunity and the major classes of R genes, such as NLR proteins. The core of the article details state-of-the-art methodological approaches, including Agrobacterium-mediated transient assays, CRISPR-based genome editing, and TALENs for targeted gene modification. It also addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for these techniques and outlines robust frameworks for the final validation and comparative analysis of resistance traits. By synthesizing traditional and cutting-edge tools, this resource aims to accelerate the functional characterization of R genes for crop improvement and durable disease resistance.

Understanding the Building Blocks: Principles of Plant Immunity and Resistance Gene Families

Plants have evolved a sophisticated, multi-layered innate immune system to defend against diverse pathogens. This system primarily consists of two interconnected tiers: Pattern-Triggered Immunity (PTI) and Effector-Triggered Immunity (ETI). PTI provides the first line of defense through recognition of conserved microbial patterns, while ETI offers a more potent, specific response triggered by detection of pathogen effector proteins. Recent research has revealed that these systems do not operate in isolation but rather function synergistically, with complex cross-talk and shared signaling components amplifying the overall immune response [1]. Understanding the mechanisms, quantitative differences, and experimental approaches to study these systems is fundamental to advancing plant disease resistance research.

Core Concepts: PTI vs. ETI

The plant immune system is often described using the "zig-zag" model, which illustrates the dynamic co-evolutionary arms race between plants and their pathogens [2]. The following table outlines the fundamental characteristics of each immunity tier.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of PTI and ETI

| Feature | Pattern-Triggered Immunity (PTI) | Effector-Triggered Immunity (ETI) |

|---|---|---|

| Triggering Molecule | Pathogen-/Microbe-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs/MAMPs) (e.g., flagellin, chitin) [2] | Pathogen effectors (avirulence factors) |

| Plant Receptors | Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs), often Receptor-Like Kinases (RLKs) or Receptor-Like Proteins (RLPs) located on the cell surface [1] [2] | Intracellular Nucleotide-binding/Leucine-rich Repeat (NLR) receptors [1] [2] |

| Recognition Specificity | Broad-spectrum; detects conserved microbial structures [2] | Strain-specific; often triggered by specific effector variants |

| Primary Function | Basal resistance against non-adapted pathogens [1] | Strong resistance against adapted pathogens, often leading to Hypersensitive Response (HR) [2] |

| Typical Response Strength | Relatively weak, providing baseline resistance [1] [2] | Strong and potent, providing robust and durable resistance [1] [2] |

| Synergy | Works cooperatively with ETI; PTI can be enhanced by ETI components [1] | Works cooperatively with PTI; synergizes to amplify defense signals like reactive oxygen species (ROS) and calcium (Ca²⁺) influx [1] |

Quantitative Comparison of Immune Responses

The quantitative differences in the amplitude and timing of PTI and ETI responses are key to their distinct biological outcomes. The following data, synthesized from empirical studies, provides a comparative profile.

Table 2: Quantitative and Temporal Dynamics of PTI and ETI Responses

| Immune Parameter | PTI Response | ETI Response | Measurement Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROS Burst | Moderate, transient [1] | Strong, sustained [1] | Luminol-based chemiluminescence assay |

| Ca²⁺ Influx | Moderate amplitude [1] | High amplitude [1] | Fluorescent indicators (e.g., aequorin, GCaMP) |

| Transcriptional Reprogramming | Hundreds of genes; slower induction | Thousands of genes; rapid, robust induction | RNA-Seq, Microarrays |

| Hypersensitive Response (HR) | Absent | Localized cell death | Ion leakage measurement, trypan blue staining |

| Systemic Signaling | Induces Priming | Induces Systemic Acquired Resistance (SAR) | Gene expression analysis in distal tissues |

| Onset Kinetics | Rapid (minutes to hours) | Delayed relative to PTI (hours) | Time-course measurements of ROS, MAPK activation |

Experimental Protocols for Dissecting Immunity

Validating the function of immune components requires robust, reproducible assays. Below are detailed protocols for key experiments in plant immunity research.

Bacterial Growth Curves for in planta Resistance

This assay quantitatively measures a plant's ability to restrict pathogen proliferation, a direct indicator of resistance strength.

Application: Used to compare bacterial growth in PTI- or ETI-deficient mutants (e.g., prr or nlr mutants) against wild-type plants after infection with pathogenic or non-pathogenic bacterial strains [3].

Detailed Protocol:

- Plant Material: Use 4-5 week-old plants (e.g., Arabidopsis, tomato).

- Pathogen Preparation: Grow Pseudomonas syringae in King's B medium overnight. Centrifuge, wash, and resuspend the bacteria in 10mM MgCl₂ to an optical density at 600 nm (OD₆₀₀) of 0.1 (~1x10⁸ CFU/mL). Perform serial dilutions for final inoculation doses (e.g., 10⁵ CFU/mL for low-dose spray or 10⁸ CFU/mL for syringe infiltration).

- Inoculation:

- Spray Infiltration: Use a fine-nozzle sprayer to evenly coat abaxial and adaxial leaf surfaces. This method is preferred for simulating natural infection via stomata.

- Syringe Infiltration: Gently press a needleless syringe containing the bacterial suspension against the abaxial leaf side and infiltrate. This method ensures a consistent and known initial inoculum within the apoplast.

- Sampling:

- Day 0 Sample: Immediately after inoculation (or once leaves are dry for spray), harvest leaf discs using a cork borer (e.g., 3 discs per leaf, 3 leaves per replicate).

- Day 3 Sample: Harvest leaf discs from the same plants 72 hours post-inoculation.

- Homogenization and Plating: Surface-sterilize discs in 70% ethanol, then rinse in sterile water. Homogenize discs in 1mL of 10mM MgCl₂. Perform a 10-fold serial dilution and spot-plate 10µL of each dilution onto King's B agar plates supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (e.g., rifampicin) to select for the pathogen.

- Data Analysis: Count colony-forming units (CFU) after a 2-day incubation at 28°C. Calculate CFU per leaf disc or cm². Plot the log-transformed CFU values, comparing the initial (Day 0) and final (Day 3) populations. A significant reduction in bacterial growth in wild-type compared to a mutant indicates the compromised immune function of the mutant.

ROS Burst Measurement

The production of reactive oxygen species is one of the earliest detectable events in both PTI and ETI.

Application: Comparing the amplitude and kinetics of the ROS burst triggered by PAMPs (e.g., flg22) in different genotypes or by pathogens during ETI [1].

Detailed Protocol:

- Leaf Disc Preparation: Harvest leaf discs from healthy, expanded leaves using a cork borer (e.g., 4mm diameter). Float the discs abaxial side down on sterile distilled water in a multi-well plate overnight in the dark to deplete wound-induced ROS.

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a working solution containing 20µM luminol (a chemiluminescent substrate) and 10µg/mL horseradish peroxidase (HRP, an enzyme that amplifies the signal) in distilled water.

- Assay Setup: Remove the water from the leaf discs and replace it with 200µL of the luminol/HRP working solution per well.

- Elicitor Treatment and Measurement: Add the desired elicitor (e.g., 1µM flg22 for PTI) directly to the well. Immediately place the plate into a luminometer or a plate reader capable of measuring luminescence. Take readings every 2-3 minutes for a period of 60-90 minutes.

- Data Analysis: Plot Relative Light Units (RLU) over time. The total ROS produced is often quantified as the integral of the curve over the measurement period, while the peak height indicates the maximum burst intensity.

Signaling Pathways and Synergy

The signaling pathways of PTI and ETI converge on several key downstream responses. The following diagram illustrates the sequential nature of plant immunity and the points of synergy between the two tiers.

Diagram 1: Plant Immune Signaling Pathway. This diagram illustrates the sequential activation of PTI and ETI. PTI is triggered by PAMP-PRR recognition, while ETI is activated by effector-NLR recognition. Both pathways synergize (blue node) to amplify common downstream defense responses like Ca²⁺ influx, ROS production, and defense gene expression. A strong hypersensitive response (HR) is primarily associated with ETI [1] [2].

Case Study: The Dual Role of Pti5 in Aphid Resistance

A compelling example of the complexity of immune signaling is the function of the ethylene response factor Pti5 in tomato resistance against the potato aphid.

- Experimental Finding: The Pti5 gene was transcriptionally upregulated in response to aphid infestation. Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) of Pti5 led to enhanced aphid population growth on both susceptible tomato plants and resistant plants carrying the Mi-1.2 R gene [4] [5].

- Interpretation: This demonstrates that Pti5 contributes to basal resistance (in susceptible plants) and can synergize with R gene-mediated defenses (in resistant plants) to limit pest survival and reproduction—an example of an immune component enhancing overall resistance [4].

- Pathway Independence: Crucially, this study showed that Pti5 induction by aphids was independent of ethylene signaling, as inhibiting ethylene synthesis did not diminish Pti5 upregulation. This reveals the existence of distinct, parallel signaling pathways regulating different aspects of defense (antibiosis vs. antixenosis) [4] [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

Studying PTI and ETI requires a toolkit of specific reagents and genetic materials. The following table lists key resources for designing experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Plant Immunity Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic PAMPs/Effectors | Chemically defined elicitors to trigger specific immune responses. | Flg22 (PTI), Elf18 (PTI), NLP effectors (ETI/PTI) [2] |

| Receptor Mutants | Genetically modified plants to determine the function of specific immune receptors. | fls2 mutant (impaired in flagellin perception), nlr mutants (compromised ETI) [2] [3] |

| Chemical Inhibitors | Tools to dissect signaling pathways by inhibiting specific components. | DPI (inhibits NADPH oxidase and ROS production), LaCl₃ (calcium channel blocker) |

| Reporter Lines | Transgenic plants that visually report immune activation. | pFRK1::LUC (reporter for MAPK activation), Ca²⁺ reporters (GCaMP), ROS probes |

| VIGS Vectors | Virus-Induced Gene Silencing vectors for rapid, transient gene knockdown. | TRV-based vectors for silencing genes like Pti5 in tomato [4] [5] |

| Genome-Edited Lines | Plants with targeted mutations in immune components or susceptibility (S) genes. | CRISPR/Cas9-generated mlo mutants (powdery mildew resistance), SWEET promoter edits (bacterial blight resistance) [2] [3] |

Advanced Applications in Disease Resistance Breeding

Knowledge of PTI and ETI mechanisms directly fuels innovative strategies for crop improvement.

- Editing Susceptibility (S) Genes: A highly successful strategy involves using CRISPR/Cas9 to knockout plant genes that pathogens exploit for infection. For example, knocking out the Mlo gene in barley and other species confers durable, broad-spectrum resistance to powdery mildew fungi. Similarly, editing the promoter of the SWEET sugar transporter family in rice prevents its induction by Xanthomonas bacteria, leading to resistance against bacterial blight [2] [3].

- Engineering NLR Receptors: Advances in understanding NLR structure and function, particularly in rice paired NLRs like Pikp-1/Pikp-2 and RGA4/RGA5, now allow for bioengineering of these receptors. Scientists can modify the integrated domains (IDs) that act as "decoys" to alter effector recognition specificity, creating new R genes effective against a wider array of pathogen strains [2].

- Enhancing PTI via PRR Engineering: Broad-spectrum resistance can be achieved by boosting the PTI layer. This includes transgenic overexpression of Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs) or transferring PRRs between species to confer recognition of new PAMPs. Marker-assisted breeding is also used to stack favorable PTI-enhancing alleles into elite crop varieties [6].

Major Classes of Disease Resistance (R) Genes and Their Domain Architectures

Plant resistance (R) genes are cornerstone components of the plant immune system, encoding proteins that detect pathogen-derived molecules and activate robust defense responses [7]. Understanding their classification and the domain architectures that underpin their function is critical for advancing disease resistance breeding and functional research. R genes are notoriously diverse, with their specific functions dictated by the combination and arrangement of protein domains that facilitate pathogen recognition, signal transduction, and initiation of effector-triggered immunity (ETI) [8] [9]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of major R gene classes, their characteristic domain architectures, and the experimental methodologies defining modern research in the field. The insights provided here are framed within the broader thesis that validating R gene function requires an integrated approach, combining deep learning-based prediction, detailed molecular experimentation, and an understanding of evolutionary principles.

Major R Gene Classes and Domain Architectures

The diversity of R proteins can be systematically categorized based on their domain composition and subcellular localization. The table below summarizes the defining features, functions, and specific domain architectures of the major R gene classes.

Table 1: Major Classes of Plant Resistance (R) Genes and Their Domain Architectures

| R Gene Class | Representative Examples | Domain Architecture | Subcellular Localization | Function & Recognition Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNL (TIR-NBS-LRR) | N, L6, RPP5 [8] [9] | TIR - NBS - LRR [10] [8] | Cytoplasmic [8] | Intracellular receptor; recognizes pathogen effectors, often leading to HR [11] [7]. |

| CNL (CC-NBS-LRR) | I2, RPM1, RPS2 [8] [9] | CC - NBS - LRR [10] [8] | Cytoplasmic [8] | Intracellular receptor; coiled-coil domain facilitates signaling [10] [7]. |

| RLK (Receptor-Like Kinase) | FLS2, Xa21 [8] [9] | eLRR - TM - Kinase [8] | Plasma Membrane [10] [8] | Cell-surface receptor; perceives PAMPs for PTI or effectors for ETI [10] [7]. |

| RLP (Receptor-Like Protein) | CF4, CF9 [8] [9] | eLRR - TM (Short Cytoplasmic Tail) [8] | Plasma Membrane [8] | Cell-surface receptor; lacks kinase domain, requires partners for signaling [8]. |

| Kinase (KIN) | Pto [8] [12] | Kinase [8] | Cytoplasmic / Membrane-Associated [9] | Intracellular serine/threonine kinase; requires NLR (e.g., Prf) for effector recognition [8] [7]. |

Key Domain Functions

- Leucine-Rich Repeat (LRR): This domain is prevalent across multiple R gene classes and is primarily responsible for protein-protein interactions, including specific recognition of pathogen effectors [8] [13]. In cell-surface receptors like RLKs and RLPs, it is extracellular (eLRR), while in NLRs, it is cytoplasmic [8].

- Nucleotide-Binding Site (NBS): A central signaling domain found in cytoplasmic NLR proteins. It is crucial for ATP/GTP binding and hydrolysis, which is necessary for activation of defense responses [11] [7].

- Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor (TIR) and Coiled-Coil (CC): These are N-terminal domains that define the two major subclasses of NLR proteins (TNL and CNL, respectively). They function in downstream signal transduction [10] [8].

- Transmembrane (TM) Domain: Anchors RLK and RLP proteins in the plasma membrane, separating extracellular recognition domains from intracellular signaling regions [8].

Theoretical Models of R Protein Function

The molecular mechanisms by which R proteins perceive pathogens and activate immunity are explained by several key models.

- Guard Hypothesis: This model posits that R proteins (guards) do not directly interact with pathogen effectors but instead monitor ("guard") host proteins (guardees) that are modified by the effector. The alteration of the guardee by the effector triggers activation of the R protein [13] [7]. A classic example is the Arabidopsis RPM1 and RPS2 proteins, which guard the host protein RIN4. Different pathogen effectors modify RIN4, activating the corresponding R protein [13] [9].

- Decoy Model: An extension of the guard hypothesis, this model suggests that some guarded host proteins are not genuine virulence targets but are "decoys" that evolved solely to attract effectors and trigger R protein-mediated immunity. The decoy mimics the operative virulence target but does not contribute to pathogen fitness, explaining its evolutionary stability [13].

- Direct Receptor-Ligand Model: In some cases, R proteins directly bind to pathogen effectors, functioning as classic receptors. This is observed in the interaction between the flax L5, L6, and L7 proteins and the rust fungus AvrL567 effectors, where direct, allele-specific binding occurs [11].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between these models and the "Zig-Zag" model of plant immunity.

Figure 1: R Gene Function in Plant Immunity. This diagram integrates the "Zig-Zag" model with the specific mechanisms of effector perception. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), activating pattern-triggered immunity (PTI). Pathogen effectors suppress PTI but can be perceived by intracellular NLR proteins, activating effector-triggered immunity (ETI). Effector perception occurs via direct binding, the Guard Hypothesis, or the Decoy Model [11] [13] [7].

Experimental Protocols for R Gene Identification and Validation

The discovery and functional characterization of R genes rely on a multi-faceted approach, combining computational prediction, transcriptomic analysis, and molecular validation.

Computational Prediction with PRGminer

The PRGminer tool represents a cutting-edge, deep learning-based methodology for high-throughput prediction of R genes from protein sequences [10].

Table 2: Key Experimental Reagents and Resources for R Gene Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PRGminer Webserver | Deep learning tool for predicting R genes and classifying them into 8 categories from protein sequences. | Initial in silico identification of putative R genes in a newly sequenced plant genome [10]. |

| Phytozome/Ensemble Plants | Public databases for plant genomic and protein sequences. | Source of known R genes and background proteomes for training prediction models and comparative analysis [10]. |

| RT-qPCR Reagents | Fluorescence-based PCR instruments (e.g., Roche LightCycler480), primers, reverse transcriptase. | Quantifying changes in gene expression of candidate R genes in response to pathogen challenge [14] [12]. |

| Reference Genes | Stably expressed endogenous control genes (e.g., for qPCR normalization). | Accurate normalization of gene expression data; selection is critical and can be done with algorithms like geNorm [12]. |

Protocol Overview:

- Data Preparation: Input protein sequences are obtained from the organism of interest.

- Phase I - Identification: The deep learning model analyzes sequence features (e.g., dipeptide composition) to classify the input as an R gene or non-R gene. PRGminer has achieved an accuracy of 95.72% on independent test sets in this phase [10].

- Phase II - Classification: Sequences predicted as R genes are further classified into one of eight specific classes (e.g., CNL, TNL, RLK, etc.) with a reported independent testing accuracy of 97.21% [10].

- Validation: Computational predictions must be followed by experimental validation.

The workflow for this process is illustrated below.

Figure 2: PRGminer Two-Phase Prediction Workflow. This workflow demonstrates the deep learning-based identification and classification of resistance genes [10].

Transcriptomic Validation in Heart Failure Research

While from a different field, the analytical pipeline used in cardiovascular research provides a robust template for R gene validation. A study analyzing heart failure myocardial biopsies employed a rigorous multi-algorithm approach to identify key genes [14].

Protocol Overview:

- Data Sourcing and Preprocessing: Transcriptome data (e.g., RNA-seq) is obtained from public repositories like the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Data is normalized, and batch effects are corrected using R packages like

limma[14]. - Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs): The

limmapackage is used to identify genes with significant expression changes between infected and healthy tissues. The Robust Rank Aggregation (RRA) method can then be applied to integrate results from multiple independent studies, generating a robust, meta-analysis-based list of DEGs [14]. - Co-expression Network Analysis: Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) identifies modules of genes with highly correlated expression patterns. A module significantly associated with the disease trait is identified, and its genes are intersected with the DEGs from RRA to pinpoint crucial candidate genes [14].

- Experimental Validation with RT-qPCR: The expression of shortlisted candidate genes is experimentally validated using Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) in a pathogen-challenged model. This involves RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and amplification on a real-time PCR instrument. Data normalization is performed using stable reference genes [14] [12].

The field of plant disease resistance is underpinned by a sophisticated understanding of R gene classes, their domain architectures, and their operational models. The CNL, TNL, RLK, RLP, and Kinase classes form the core of the plant immune arsenal, each defined by a specific domain combination that dictates function and localization. Research in this area is increasingly powered by integrated methodologies. Computational tools like PRGminer enable the high-throughput discovery of novel R genes, while advanced transcriptomic pipelines and molecular techniques provide the necessary validation of gene function. This comprehensive, multi-disciplinary approach is essential for validating R gene function and ultimately engineering durable disease resistance in crops, securing global food production.

Nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat receptors (NLRs) constitute a pivotal class of intracellular immune receptors that form the core of the plant innate immune system. These proteins function as specialized sensors that detect pathogen-derived effector molecules and initiate robust defense responses, a process known as effector-triggered immunity (ETI) [15] [16]. The NLR family represents one of the largest and most diversified gene families in plant genomes, characterized by rapid evolution and remarkable structural complexity [17]. Understanding NLR structure, function, and evolutionary dynamics is fundamental to advancing plant disease resistance research and developing sustainable crop protection strategies. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of NLR diversity, experimental approaches for their validation, and integrated data to inform research on plant immune receptor function.

Structural Architecture and Classification of NLR Proteins

Core Domain Organization

Plant NLR proteins share a conserved multidomain architecture centered on a nucleotide-binding adaptor shared by APAF-1, R proteins, and CED-4 (NB-ARC) domain and a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) region [18] [19]. The NB-ARC domain functions as a molecular switch, cycling between ADP-bound (inactive) and ATP-bound (active) states to regulate immune signaling [17]. The LRR domain is primarily involved in protein-protein interactions, including effector recognition and autoinhibition [17].

N-terminal Domain Diversity and Classification

The N-terminal domains of NLRs define their primary classification and signaling mechanisms. The major NLR classes include:

- TIR-NLRs (TNLs): Contain a Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor (TIR) domain at the N-terminus. TNL-mediated signaling typically requires the EDS1 (Enhanced Disease Susceptibility 1) pathway [17].

- CC-NLRs (CNLs): Feature a Coiled-Coil (CC) domain at the N-terminus. Most CNLs depend on NDR1 (Non-race-specific Disease Resistance 1) for signaling [17].

- RPW8-NLRs (RNLs): Characterized by an N-terminal RPW8 (Resistance to Powdery Mildew 8) domain. RNLs often function as "helper" NLRs (hNLRs) in signaling networks [15] [16].

Recent phylogenetic and microsynteny analyses have refined CNL classification into three subclasses: CNLA, CNLB, and CNL_C [20]. Additionally, a distinct G10-subclade of NLRs (CCG10-NLR) has been proposed as a monophyletic group with a unique CC domain [19].

Table 1: Major NLR Classes and Their Characteristics

| NLR Class | N-terminal Domain | Signaling Adapter | Primary Functions | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNL | TIR (Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor) | EDS1 | Effector recognition, immune signaling | Dicots, non-flowering plants |

| CNL | CC (Coiled-Coil) | NDR1 | Effector recognition, resistosome formation | Monocots and dicots |

| RNL | RPW8 (Resistance to Powdery Mildew 8) | - | Helper NLR, signal transduction | Monocots and dicots |

Atypical NLRs and Integrated Domains

Many NLRs deviate from the standard architecture by containing additional integrated domains (IDs), forming NLR-ID proteins. These integrated domains—which can include WRKY, kinase, heavy metal-associated (HMA), and zinc-finger BED (zf-BED) domains—often function as "decoys" that mimic pathogen effector targets [15] [19]. When effectors interact with these decoy domains, they trigger NLR activation, enabling pathogen detection [16].

Evolutionary Dynamics and Genomic Distribution

NLR Expansion and Contraction Across Plant Lineages

NLR gene families exhibit remarkable variation in size across plant species, reflecting diverse evolutionary pressures and genomic histories. For example, bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) contains over 2,000 NLR genes, while cucumber (Cucumis sativus) has approximately 50-100 NLR genes [17]. This variation is not strictly correlated with genome size; apple (Malus domestica), with a 740 Mb genome, contains nearly 1,000 NLR genes [17].

Comparative genomic analyses reveal that NLR family size often changes significantly during domestication. In asparagus, wild relatives possess larger NLR repertoires (A. setaceus: 63 NLRs; A. kiusianus: 47 NLRs) compared to cultivated garden asparagus (A. officinalis: 27 NLRs), suggesting artificial selection for yield and quality traits led to NLR contraction and increased disease susceptibility [21].

Evolutionary studies across divergent plant lineages, including non-flowering plants like the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha, demonstrate that the core NLR structure and immune function are ancient, dating back approximately 500 million years [22]. The N-terminal domains, particularly CC domains, retain conserved immune functions across these evolutionarily distant species [22].

Lineage-Specific Evolution and Gene Loss

Certain NLR classes show lineage-specific patterns of expansion or loss. A notable example is the absence of TNL genes in monocots, which microsynteny evidence suggests resulted from specific loss events rather than ancestral absence [20]. This pattern persists in modern monocots, with ongoing pseudogenization of TNLs observed in the Oleaceae family, alongside expansion of CCG10-NLRs [23].

Whole-genome duplication events significantly impact NLR evolution. In the Oleaceae family, genes acquired from an ancient whole-genome duplication (~35 million years ago) have been retained across Fraxinus lineages, while the genus Olea has undergone recent gene expansion through new duplications and birth of novel NLR families [23].

Table 2: NLR Gene Family Size Variation Across Plant Species

| Plant Species | Genome Size (Approx.) | NLR Count | Notable Evolutionary Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triticum aestivum (Bread wheat) | 16 Gb | >2,000 | Extreme expansion; polyploidy history |

| Malus domestica (Apple) | 740 Mb | ~1,000 | Expansion in woody perennial |

| Asparagus setaceus (Wild) | - | 63 | Wild relative with expanded repertoire |

| Asparagus officinalis (Cultivated) | - | 27 | Domesticated with NLR contraction |

| Oryza sativa (Rice) | 430 Mb | ~500 | Representative monocot (lacks TNLs) |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | 135 Mb | ~150 | Model dicot with balanced NLR types |

Molecular Mechanisms and Functional Paradigms

Effector Recognition Strategies

NLRs employ diverse molecular strategies to detect pathogen effectors:

Direct Recognition: Some NLRs physically bind pathogen effector proteins through their LRR domains or integrated domains. Examples include the barley MLA proteins recognizing AVRA effectors and the tomato Sw-5b NLR interacting with the tospovirus NSm movement protein [15] [16].

Indirect Recognition (Guard/Decoy Models): Most CNLs monitor host cellular components that are modified by pathogen effectors. In the guard model, NLRs guard functional host proteins ("guardees"); in the decoy model, NLRs monitor non-functional mimics of host targets ("decoys") [16]. The Arabidopsis CNL ZAR1 exemplifies this mechanism, forming a precomplex with the pseudokinase RKS1 that detects uridylylation of the decoy PBL2 by the Xanthomonas effector AvrAC [15] [16].

Activation Mechanisms and Resistosome Formation

Upon effector recognition, NLRs undergo conformational changes that promote nucleotide exchange (ADP to ATP) and oligomerization into signaling complexes called resistosomes [16]. The Arabidopsis ZAR1 resistosome forms a pentameric structure that functions as a calcium-permeable channel at the plasma membrane, initiating defense signaling and programmed cell death [16]. This represents a paradigm shift in understanding how NLRs transduce recognition signals into immune activation.

Subcellular Localization and Signaling Compartments

NLRs localize to diverse subcellular compartments, often determined by their N-terminal domains and pathogen detection requirements:

Plasma Membrane: Several CNLs (e.g., Arabidopsis RPS5, RPM1) localize to the plasma membrane through N-terminal acylation, where they detect modifications to membrane-associated guardees [18].

Nucleocytoplasmic Shuttling: Some NLRs (e.g., barley MLA10, Arabidopsis RPS4) shuttle between cytoplasm and nucleus, activating distinct defense pathways in each compartment [18].

Endomembrane Systems: Certain NLRs target specific organelles; the flax rust resistance proteins L6 and M localize to Golgi apparatus and tonoplast, respectively [18].

Experimental Approaches for NLR Identification and Validation

Genome-Wide NLR Identification and Annotation

Standardized pipelines for NLR identification combine domain-based searches with evolutionary analyses:

Domain Detection: Hidden Markov Model (HMM) searches using the conserved NB-ARC domain (PF00931) as query, followed by validation with InterProScan and NCBI's Batch CD-Search [21].

Classification Tools: NLRtracker, NLR-Annotator, and NLR-Parser extract and classify NLRs from genomic or transcriptomic data [19]. These tools should be benchmarked against reference datasets like RefPlantNLR, which contains 481 experimentally validated NLRs from 31 plant genera [19].

Microsynteny Analysis: Network analysis of conserved gene order provides evolutionary insights, enabling the identification of orthologous NLR loci across species [20].

Expression-Based Functional Screening

Recent high-throughput approaches exploit expression patterns to identify functional NLRs. Contrary to historical assumptions that NLRs are transcriptionally repressed, functional NLRs often show high steady-state expression in uninfected plants [24]. A proof-of-concept study expressing 995 NLRs from diverse grasses in wheat identified 31 new resistance genes (19 against stem rust, 12 against leaf rust) [24].

Table 3: Key Experimental Methods for NLR Functional Analysis

| Method Category | Specific Protocols | Key Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Mining | HMM searches (NB-ARC domain), NLRtracker pipeline, microsynteny analysis | NLR identification, classification, evolutionary studies | Benchmark against RefPlantNLR; validate domain architectures |

| Expression Analysis | RNA-seq of uninfected tissues, expression level screening | Prioritizing functional NLR candidates | Functional NLRs often highly expressed; tissue specificity matters |

| Functional Validation | High-throughput transformation, pathogen inoculation assays | Confirming resistance function, determining specificity | Copy number may affect phenotype; avoid autoimmunity |

| Mechanistic Studies | Subcellular localization, protein-protein interaction assays | Understanding mode of action, signaling pathways | Consider localization changes upon activation |

High-Throughput Functional Validation

Large-scale transformation coupled with phenotyping provides direct evidence of NLR function. A workflow for wheat includes:

- Candidate Selection: Prioritize NLRs based on high expression signatures and phylogenetic distinctness [24].

- Vector Construction: Clone NLR coding sequences with native promoters or constitutive expression systems [24].

- Plant Transformation: Use high-efficiency transformation systems (e.g., Agrobacterium-mediated) to generate transgenic arrays [24].

- Phenotyping: Challenge T0 or T1 plants with pathogens and score for resistance symptoms, hypersensitive response, and pathogen growth [24].

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Resources for NLR Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Datasets | RefPlantNLR (481 validated NLRs) | Benchmarking, classification standards | [19] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | NLRtracker, NLR-Annotator | Genome-wide NLR identification, annotation | [21] [19] |

| Expression Resources | RNA-seq datasets from uninfected tissues | Expression-based candidate prioritization | [24] |

| Experimental Collections | Transgenic NLR arrays (e.g., 995 grass NLRs in wheat) | High-throughput functional screening | [24] |

| Domain Databases | Pfam, InterPro, PRGdb 4.0 | Domain architecture analysis, classification | [21] |

The plant NLR family represents a sophisticated immune receptor system characterized by structural diversity, complex evolutionary dynamics, and versatile pathogen recognition mechanisms. Recent advances in comparative genomics, high-throughput functional screening, and structural biology have dramatically accelerated our understanding of NLR biology. The emerging paradigm reveals NLRs as components of interconnected immune networks that balance rapid pathogen recognition with tight regulatory control to avoid autoimmunity. The experimental approaches and resources summarized in this guide provide a foundation for continued discovery and validation of NLR function, with significant implications for engineering disease resistance in crop species. Future research directions include elucidating resistosome structures for diverse NLR classes, understanding NLR network integration, and developing precision breeding strategies that deploy effective NLR combinations against evolving pathogen populations.

Reference datasets are fundamental pillars in computational biology, serving to define canonical biological features and providing the essential foundation for benchmarking studies [19]. In the study of plant disease resistance, the nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NLR) family represents the predominant class of intracellular immune receptors that detect pathogens and activate robust immune responses [25]. The RefPlantNLR dataset emerged in 2021 as the first comprehensive collection of experimentally validated plant NLR proteins, addressing a critical gap in the field by providing a standardized reference for comparative studies and tool development [19]. This guide objectively examines the performance of RefPlantNLR against alternative resources and methodologies, contextualizing its utility within the broader framework of plant disease resistance gene validation.

The RefPlantNLR Dataset

RefPlantNLR represents a manually curated collection of 481 experimentally validated NLR proteins from 31 genera belonging to 11 orders of flowering plants [19] [25]. The dataset was constructed through extensive literature curation, with sequences meeting strict criteria for experimental validation, including demonstrated roles in disease resistance, susceptibility, hybrid necrosis, autoimmunity, helper functions, or well-described allelic series [25]. Each entry includes amino acid sequences, coding sequences, locus identifiers, source organisms, and associated literature, providing a comprehensive foundation for comparative analyses [19].

The dataset reveals significant taxonomic bias in current NLR research, with Arabidopsis, cereals (rice, wheat, barley), and Solanaceae species collectively representing approximately three-fourths of all validated NLRs [26]. Furthermore, NLR distribution across structural subclades is uneven, with CC-NLRs and TIR-NLRs constituting nearly 80% of validated receptors, while CCR-NLRs and CCG10-NLRs represent more specialized minorities [26].

Several bioinformatic tools have been developed for NLR annotation and extraction, each employing distinct methodologies and targeting different research applications:

Table 1: NLR Annotation and Extraction Tools

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Input Data | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| NLR-Parser | NLR extraction | Protein/transcript sequences | Predefined motifs for NLR classification [19] |

| RGAugury | NLR and other RG extraction | Protein/transcript sequences | Identifies multiple classes of resistance genes [19] |

| RRGPredictor | NLR and other RG extraction | Protein/transcript sequences | Resistance gene prediction pipeline [19] |

| DRAGO2 | NLR extraction | Protein/transcript sequences | Identifies NLRs with predefined motifs [19] |

| NLR-Annotator | Genome annotation & NLR prediction | Unannotated genome sequences | Predicts genomic locations of NLRs [19] |

| NLGenomeSweeper | Genome-wide NLR identification | Unannotated genome sequences | Identifies NLR loci requiring manual annotation [19] |

| NLRtracker | NLR extraction & annotation | Protein/transcript sequences | Based on RefPlantNLR core features [25] |

Performance Comparison: RefPlantNLR vs. Alternative Tools

Benchmarking Results

The RefPlantNLR dataset was used to systematically evaluate the performance of five NLR annotation tools, revealing critical differences in their capabilities and limitations.

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of NLR Annotation Tools Against RefPlantNLR

| Performance Metric | NLR-Parser | RGAugury | RRGPredictor | DRAGO2 | NLRtracker |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLR Retrieval Rate | High | High | High | High | High |

| Domain Architecture Accuracy | Inconsistent | Inconsistent | Inconsistent | Inconsistent | High |

| Handling of Integrated Domains | Limited | Limited | Limited | Limited | Improved |

| Basis of Annotation | Predefined motifs | Predefined motifs | Predefined motifs | Predefined motifs | RefPlantNLR features |

The benchmarking demonstrated that while most tools successfully retrieved the majority of NLRs present in the RefPlantNLR dataset, they frequently produced domain architectures inconsistent with the manually curated RefPlantNLR annotations [19]. This discrepancy is particularly evident for non-canonical NLRs with integrated domains or unusual architectural features [25].

Experimental Validation Workflows

The true value of reference datasets is realized through their integration into experimental workflows for resistance gene validation. The following diagram illustrates an optimized gene cloning workflow that incorporates reference datasets for rapid identification and validation of NLR genes:

Diagram: Workflow for Rapid NLR Gene Cloning and Validation. This optimized protocol enables gene identification in less than six months by integrating reference datasets for candidate gene prioritization [27].

This workflow was successfully applied to clone the wheat stem rust resistance gene Sr6, achieving identification within 179 days using only three square meters of plant growth space [27]. The process involved screening approximately 4,000 M2 families, identifying 98 loss-of-resistance mutants, with transcriptome analysis of 10 mutants revealing a single consistent NLR transcript carrying EMS-type mutations [27].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

RefPlantNLR Dataset Construction Protocol

The construction of RefPlantNLR followed a rigorous manual curation process:

- Literature Mining: Comprehensive survey of scientific literature for experimentally characterized NLRs

- Validation Criteria Application: Inclusion based on seven evidence categories (disease resistance, susceptibility, hybrid necrosis, autoimmunity, helper function, immune regulation, allelic series)

- Sequence Verification: Confirmation of NB-ARC domain (Pfam PF00931) or P-loop NTPase domain (SSF52540) with plant-specific NLR motifs

- Domain Architecture Annotation: Standardized annotation of N-terminal domains (TIR, CC, CCR, CCG10) and integrated domains

- Metadata Collection: Curation of associated pathogens, effector identities, functional characteristics, and literature references

This protocol resulted in the identification of 479 qualified sequences, with the addition of RXL and AtNRG1.3 bringing the final collection to 481 NLRs [25].

NLRtracker Development and Implementation

Guided by benchmarking results, the researchers developed NLRtracker as a new pipeline that leverages RefPlantNLR core features:

Diagram: NLRtracker Analysis Pipeline. This tool extracts and annotates NLRs based on RefPlantNLR features and facilitates phylogenetic analysis [25].

CRISPR Activation for NLR Functional Validation

Beyond traditional gene cloning, CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) has emerged as a powerful tool for NLR functional validation:

Protocol: CRISPRa-Mediated NLR Validation

- dCas9-VPR System Design: Fusion of deactivated Cas9 to VP64-p65-Rta transcriptional activation domains

- sgRNA Selection: Target sequences in NLR promoter regions

- Plant Transformation: Delivery via Agrobacterium or biolistics

- Transcriptional Activation: Quantitative RT-PCR to measure NLR upregulation

- Phenotypic Assessment: Disease resistance assays to validate function

This approach enables gain-of-function studies without altering DNA sequence, overcoming functional redundancy challenges common in NLR gene families [28]. Successful applications include epigenetic reprogramming of SlWRKY29 in tomato and upregulation of defense genes in Phaseolus vulgaris hairy roots [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NLR Gene Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| RefPlantNLR Dataset | Reference dataset for benchmarking & comparison | Defining canonical NLR features; tool evaluation [19] |

| NLRtracker Pipeline | NLR extraction & annotation | Domain architecture analysis; NB-ARC extraction [25] |

| dCas9 Transcriptional Activators | CRISPRa-mediated gene activation | Gain-of-function studies without DNA alteration [28] |

| EMS Mutagenesis Populations | Forward genetic screens | Identification of loss-of-function NLR mutants [27] |

| Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) | Transient gene silencing | Functional validation of candidate NLR genes [27] |

| NLR-Annotator | Genome-wide NLR prediction | Identification of NLR loci in unannotated genomes [19] |

| RefPlantnlR R Package | NLR domain visualization | Publication-ready domain architecture diagrams [29] |

RefPlantNLR represents a significant advancement in the standardization of plant NLR research, providing an essential reference dataset that has enabled critical benchmarking of annotation tools and revealed important limitations in existing methodologies. The resource has directly facilitated the development of improved analytical pipelines like NLRtracker and supports comparative analyses across plant taxa.

The integration of reference datasets like RefPlantNLR with emerging technologies—including CRISPRa for gain-of-function studies, optimized gene cloning workflows for rapid validation, and multi-omics approaches for systems-level analysis—is accelerating the pace of disease resistance gene discovery and functional characterization. These developments are particularly crucial for addressing the significant biases in current NLR research, which has largely focused on model plants and major crops, leaving substantial diversity in non-flowering plants and understudied taxa unexplored [26].

As the field progresses, the continued expansion and refinement of reference datasets will be essential for capturing the full diversity of NLR architecture and function, ultimately enabling more durable and broad-spectrum disease resistance in crop plants.

Bioinformatic Tools for Initial R Gene Discovery and Sequence Analysis

Plant resistance genes (R-genes) constitute a critical line of defense in plant immune systems, encoding proteins that recognize pathogen-derived molecules and initiate robust defense responses [10] [30]. The identification and characterization of these genes have been revolutionized by bioinformatic tools, which enable researchers to process vast genomic datasets and predict R-genes with increasing accuracy. The plant immune system primarily operates through two layered mechanisms: Pattern-Triggered Immunity (PTI), initiated by cell-surface localized pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that detect conserved pathogen molecules, and Effector-Triggered Immunity (ETI), activated by intracellular nucleotide-binding site leucine-rich repeat (NLR) proteins that recognize specific pathogen effectors [10] [31]. Bioinformatics tools have become indispensable for navigating the complexity of R-gene families, which are often large, diverse, and organized in complex clusters that challenge conventional annotation pipelines [10]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of leading bioinformatic tools for initial R-gene discovery, evaluating their methodologies, performance, and appropriate applications within plant disease resistance research.

Comparative Analysis of R-Gene Discovery Tools

Table 1: Core Features of R-Gene Discovery Tools

| Tool Name | Primary Methodology | Input Data | Core Function | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRGminer [10] | Deep Learning (Dipeptide composition) | Protein sequences | R-gene identification & classification into 8 classes | Binary prediction (R-gene/Non-R-gene) + Class assignment |

| PRGdb [32] | Curated database + DRAGO prediction pipeline | Nucleotide or protein sequences | Reference database query & homology-based prediction | Annotated R-gene sequences with functional and taxonomic data |

| Alignment-Based Tools [10] | BLAST, HMMER, InterProScan | Protein sequences | Domain/motif identification & homology search | Domain architecture & similarity-based annotations |

PRGminer represents a significant advancement in prediction technology, employing a two-phase deep learning framework. In Phase I, the tool distinguishes R-genes from non-R-genes using dipeptide composition as sequence representation. Phase II then classifies the predicted R-genes into eight specific classes: CNL (Coiled-coil, Nucleotide-binding site, Leucine-rich repeat), TNL (Toll/interleukin-1 receptor, NBS, LRR), RLK (Receptor-like kinase), RLP (Receptor-like protein), LECRK (Lectin receptor-like kinase), LYK (LysM receptor-like kinase), KIN (Kinase), and TIR (Toll/interleukin-1 receptor) [10].

In contrast, PRGdb (Plant Resistance Gene database) provides a comprehensive knowledge base incorporating multiple data types. The platform hosts manually curated reference R-genes, putative R-genes collected from NCBI, and computationally predicted R-genes generated by its DRAGO (Disease Resistance Analysis and Gene Orthology) pipeline [32]. This combination of curated and predicted data offers researchers both verified references and discovery capabilities.

Traditional alignment-based methods utilize tools like BLAST, HMMER, and InterProScan to identify R-genes through sequence similarity and domain presence. These methods rely on comparing query sequences against databases of known R-gene domains and motifs, making them particularly effective for identifying R-genes with high homology to previously characterized sequences [10].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Table 2: Performance Metrics of R-Gene Discovery Tools

| Tool Name | Accuracy (%) | MCC Value | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRGminer [10] | 95.72-98.75 (Phase I); 97.21-97.55 (Phase II) | 0.91-0.98 (Phase I); 0.92-0.93 (Phase II) | High accuracy with novel sequences; Detailed classification | Limited to 8 predefined classes; Requires protein sequences |

| PRGdb [32] | N/A (Database resource) | N/A | Extensive curated data; Cross-species coverage | Dependent on existing knowledge; Limited to known R-gene architectures |

| Alignment-Based Tools [10] | Varies by tool and dataset | Typically lower than deep learning | Widely accessible; Interpretable results | Performance drops with low-homology sequences |

Experimental validation of PRGminer demonstrated exceptional performance metrics. During independent testing, the tool achieved 95.72% accuracy in Phase I (R-gene identification) with a Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) of 0.91, indicating strong binary classification performance. In Phase II (R-gene classification), it maintained 97.21% accuracy with an MCC of 0.92, reflecting robust multi-class discrimination capability [10]. The k-fold cross-validation during training showed even higher performance (98.75% accuracy in Phase I, 97.55% in Phase II), confirming the model's reliability [10].

PRGdb contains the largest collection of R-genes to date, with over 16,000 known and putative R-genes from 192 plant species challenged by 115 different pathogens [32]. The database includes 73 manually curated reference R-genes, 6,308 putative R-genes from NCBI, and 10,463 computationally predicted R-genes, providing an extensive resource for comparative analysis [32].

Experimental Protocols for R-Gene Analysis

PRGminer Deep Learning Workflow

Objective: Identify and classify protein sequences as R-genes using deep learning.

Input Requirements: Protein sequences in FASTA format.

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Encode protein sequences using dipeptide composition, which represents the frequency of all possible pairs of amino acids throughout the sequence.

- Phase I - R-gene Identification:

- Process encoded sequences through a deep neural network architecture.

- The model outputs a binary classification (R-gene or non-R-gene).

- Sequences classified as non-R-genes are excluded from further analysis.

- Phase II - R-gene Classification:

- R-gene sequences from Phase I are processed through a separate deep learning model.

- The model assigns each sequence to one of eight R-gene classes based on domain architecture.

- Validation: Assess prediction confidence using the built-in evaluation metrics; consider experimental validation for high-priority candidates.

Output Interpretation: The tool provides both binary classification and detailed class assignment, enabling researchers to prioritize candidates for functional validation based on prediction confidence and class-specific interests [10].

PRGdb Database Mining Protocol

Objective: Identify known and putative R-genes using curated database resources.

Input Requirements: Nucleotide or protein sequences, or keyword queries.

Methodology:

- Database Access: Navigate to the PRGdb web interface (http://www.prgdb.org).

- Sequence Query:

- Submit protein or nucleotide sequences for similarity search using BLAST.

- Alternatively, use the DRAGO pipeline for prediction of novel R-genes.

- Keyword Search: Query the database using gene names, plant species, or pathogen information.

- Result Analysis: Filter results by species, pathogen, or R-gene class.

- Comparative Analysis: Utilize the database's integrated tools for cross-species comparison and evolutionary analysis.

Output Interpretation: The database returns annotated sequences with information on known domains, functional characteristics, and associated pathogens, providing a comprehensive overview of R-gene diversity [32].

Visualization of R-Gene Analysis Workflows

PRGminer Deep Learning Pipeline

PRGminer Two-Phase Prediction

Plant Immunity and R-Gene Function

Plant Immune Signaling Pathways

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for R-Gene Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function in R-Gene Research | Example Sources/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Reference R-Gene Datasets | Benchmarking and training prediction models | PRGdb curated collection [32] |

| Protein Sequence Databases | Source material for novel R-gene discovery | Phytozome, Ensemble Plants, NCBI [10] |

| Domain Annotation Tools | Identification of characteristic R-gene domains | InterProScan, HMMER, PfamScan [10] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Implementation of custom prediction models | TensorFlow, PyTorch (for PRGminer-like tools) [10] |

| Plant Genomic Resources | Source of novel sequences for mining | Species-specific genome databases [33] |

Discussion and Research Applications

The integration of bioinformatic tools into R-gene discovery pipelines has dramatically accelerated the pace of plant immunity research. Deep learning approaches like PRGminer offer superior performance for identifying novel R-genes with limited homology to known sequences, making them particularly valuable for studying non-model plant species or rapidly evolving R-gene families [10]. Conversely, curated knowledge bases like PRGdb provide essential context and evolutionary insights that support functional characterization and comparative genomics [32].

For comprehensive R-gene analysis, researchers should adopt a sequential approach: beginning with database mining to establish known relationships, proceeding to deep learning prediction to identify novel candidates, and finally employing experimental validation to confirm function. This integrated strategy leverages the respective strengths of each tool while mitigating their individual limitations.

Future directions in R-gene bioinformatics will likely focus on improving prediction granularity, incorporating structural information, and expanding to include susceptibility gene identification. As these tools evolve, they will continue to empower researchers in developing disease-resistant crops through targeted breeding and genetic engineering, ultimately contributing to enhanced global food security.

A Practical Toolkit: From Transient Assays to Precise Genome Editing

Agrobacterium-Mediated Transient Expression for Rapid Gene Function Screening

In the field of plant functional genomics, rapidly validating the role of candidate genes, especially those involved in complex processes like disease resistance, is a critical research bottleneck. Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression (AMTE) has emerged as a powerful solution, enabling researchers to analyze gene function within days rather than the months required for stable transformation. This technique involves the temporary introduction of genetic material into plant cells using Agrobacterium tumefaciens, resulting in transient but high-level gene expression without integration into the host genome [34]. For plant disease resistance research, this rapid screening capability is particularly valuable, allowing for high-throughput functional analysis of candidate resistance genes and their role in plant-pathogen interactions before committing to lengthy stable transformation approaches [35] [36]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of AMTE methodologies across diverse plant species, detailing optimized protocols and their specific applications in validating plant disease resistance gene function.

Technical Comparison of AMTE Systems Across Plant Species

Table 1: Optimization Parameters for AMTE Across Plant Species

| Plant Species | Optimal Agrobacterium Strain | Key Vector | Infiltration Method | Critical Additives | Optimal Incubation Conditions | Expression Peak | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barley (Monocot) [35] [36] | AGL1, C58C1 | pCBEP | Vacuum or syringe | Acetosyringone | 1 day high humidity, then 2 days darkness | 4 days post-infiltration (dpi) | Screening disease-promoting genes (e.g., rice blast) |

| Arabidopsis [37] | C58C1(pTiB6S3ΔT)H | pBISN1 | Vacuum infiltration (seedlings) | AB salts, MES buffer (pH 5.5) | Co-cultivation in ABM-MS medium | 3 dpi | Signaling pathway analysis, protein localization |

| Sunflower [38] | GV3101 | pBI121 | Infiltration, Injection, Ultrasonic-Vacuum | 0.02% Silwet L-77 | 3 days darkness (injection) | Sustained for 6 days | Abiotic stress gene validation (e.g., HaNAC76) |

| Caragana intermedia [34] | GV3101 | pBI121 | Syringe infiltration | 0.001% Silwet L-77 | Standard growth conditions | 2-3 dpi | Abiotic stress tolerance (e.g., CiDREB1C) |

| Strawberry [39] | GV3101 | RNAi vectors | Syringe (fruit), Vacuum (leaf/root) | 200 µM Acetosyringone | 3h pre-incubation in dark, room temp | 4-6 dpi (fruit) | Tissue-specific assays (e.g., fruit anthocyanin, leaf disease) |

Table 2: Quantitative Efficiency Metrics of AMTE in Various Plants

| Plant Species | Reporter System | Transformation Efficiency | Key Quantitative Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barley [36] | GUS (Fluorometric) | N/D | pCBEP vector produced >2x higher GUS activity than pER8 and pCBDEST. 1-day high humidity increased GUS activity >7-fold. | [36] |

| Arabidopsis [37] | GUS (Histochemical/Fluorometric) | 100% (efr-1 seedlings) | GUS activity in efr-1 mutant was 4x higher than Col-0. ABM-MS medium increased GUS activity 20-fold vs. MS medium. | [37] |

| Sunflower [38] | GUS (Histochemical) | >90% (All 3 methods) | Silwet L-77 increased GUS expression by 44.4% vs. Triton X-100. Optimal OD600 was 0.8. | [38] |

| Strawberry [39] | qRT-PCR, Phenotype | N/D | RNAi-mediated knockdown of EDR1 led to ~6-fold reduction in gene expression and increased susceptibility to Neopestalotiopsis spp. | [39] |

| Citrus [40] | GUS (Assumed) | N/D | Optimized method demonstrated up to a six-fold increase in transient GUS expression. | [40] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Systems

High-Efficiency AMTE in Monocots (Barley)

The optimization of AMTE in barley provides a template for other recalcitrant monocot species [35] [36].

- Vector and Strain Selection: The binary vector pCBEP was found to be superior, driving reporter gene expression more than twice as high as other common vectors like pER8 and pCBDEST when delivered via Agrobacterium strains AGL1 or C58C1 [36].

- Plant Material: Use intact plants of a susceptible variety (e.g., E9) at the 1-leaf seedling stage. The first leaf consistently shows more intense expression than older leaves [36].

- Agrobacterium Culture Preparation: Grow the transformed Agrobacterium strain in an appropriate medium. Re-suspend the bacterial pellet to an optimal density of OD600 = 0.5 in infiltration buffer [36].

- Infiltration: Either vacuum or syringe infiltration can be used with comparable efficiency [36].

- Post-Infiltration Incubation: Place infiltrated plants under high humidity (>98%) for one day, followed by transfer to darkness for two days. This combined treatment significantly boosts transgene expression [36].

- Analysis: Peak protein expression for assays like split-luciferase interaction studies is typically achieved at 4 days post-infiltration (dpi) [36].

AGROBEST: An Optimized System for Arabidopsis Seedlings

The AGROBEST system achieves high transformation efficiency in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, which is often challenging for transient assays [37].

- Strain and Genotype: Use the disarmed Agrobacterium strain C58C1(pTiB6S3ΔT)H containing a pCH32 helper plasmid. For highest efficiency, the EF-Tu receptor mutant efr-1 is recommended, though wild-type Col-0 is also feasible [37].

- Pre-induction: Pre-induce the bacterial culture with acetosyringone (AS) in AB-MES medium (pH 5.5) to activate virulence genes [37].

- Seedling Preparation: Grow Arabidopsis seedlings for 4 days under sterile conditions [37].

- Co-cultivation Medium: The key to high efficiency is using a 1:1 mixture of AB-MES and MS medium (ABM-MS), which maintains an acidic pH of 5.5 and provides essential nutrients and salts for the bacteria [37].

- Infection and Co-cultivation: Incubate seedlings with the pre-induced Agrobacterium in the ABM-MS medium [37].

- Analysis: Robust transient expression, with 100% of seedlings showing homogenous GUS staining in cotyledons, can be observed at 3 days post-infection [37].

Tissue-Specific Transient Assay in Strawberry

This protocol is adapted for octoploid strawberry, covering fruit, leaf, and root/crown tissues [39].

- Strain and Vector: Use GV3101 transformed with the gene of interest in an appropriate RNAi or overexpression vector [39].

- Inoculum Preparation: Harvest bacteria and re-suspend in an activation buffer containing 200 µM acetosyringone. Incubate for 3 hours in the dark at room temperature [39].

- Tissue-Specific Infiltration:

- Incubation and Analysis: Maintain infiltrated tissues under standard growth conditions. For functional analysis like disease resistance assays, challenge the tissues with pathogens (e.g., Neopestalotiopsis spp.) and assess symptoms and gene expression (e.g., by qRT-PCR) around 5-7 days post-infiltration [39].

Application in Plant Disease Resistance Research

AMTE is particularly impactful for dissecting the molecular mechanisms of plant disease resistance, enabling both gain-of-function and loss-of-function studies.

Functional Screening for Susceptibility Genes

A powerful application of AMTE is the high-throughput identification of host genes that promote disease (susceptibility genes). This was demonstrated in barley against the rice blast fungus (Magnaporthe oryzae) [35] [36].

- Experimental Approach: A full-length cDNA library from rice during early blast infection was cloned into the pCBEP vector. This library was screened via AMTE in barley leaves, followed by challenge with the blast fungus [36].

- Findings: The screen identified 15 candidate susceptibility genes from approximately 2000 clones. Four of these encoded chloroplast-related proteins (OsNYC3, OsNUDX21, OsMRS2-9, and OsAk2). Subsequent stable overexpression of these genes in Arabidopsis confirmed their role in enhancing susceptibility to another pathogen, Colletotrichum higginsianum [36].

- Implication: This highlights AMTE's power to rapidly identify key host factors that pathogens exploit to cause disease, providing new targets for breeding resistance.

Validating Resistance Gene Function

AMTE is equally effective for validating the function of known or putative resistance genes, as shown in strawberry.

- Experimental Approach: The function of a strawberry homolog of the Arabidopsis EDR1 gene, a known negative regulator of disease resistance, was tested. An RNAi construct targeting FaEDR1 was transiently expressed in strawberry leaves via vacuum infiltration. The leaves were then challenged with Neopestalotiopsis spp. [39].

- Findings: Leaves with transiently silenced FaEDR1 showed significantly higher susceptibility to the pathogen compared to controls. qRT-PCR confirmed that the gene expression level of EDR1 in the knockdown plants was approximately six-fold lower than in the control, directly linking the gene to resistance [39].

- Implication: This provides a rapid method to confirm the function of resistance genes in a homologous system, bypassing the need for stable transformation.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key signaling components involved in using AMTE for disease resistance gene validation, integrating the examples above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for AMTE Experiments

| Reagent | Function in AMTE | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium Strains | Delivery vehicle for T-DNA into plant cells. | GV3101: Versatile, good for dicots (sunflower, strawberry) [38] [34] [39]. AGL1/C58C1: High efficiency in monocots (barley) and Arabidopsis [36] [37]. |

| Binary Vectors | Carries the gene of interest within T-DNA borders. | pCBEP: Superior expression in monocots [36]. Standard 35S promoters (e.g., pBI121) are widely used [38] [34]. |

| Chemical Inducers | Activate Agrobacterium vir genes, facilitating T-DNA transfer. | Acetosyringone (AS): Most common inducer, used in pre-induction and/or infiltration buffer [36] [39]. |

| Surfactants | Reduce surface tension, improving infiltration. | Silwet L-77: Highly effective, concentration critical (0.001%-0.02%) [38] [34]. |

| Buffering Systems | Maintain optimal pH for Agrobacterium-plant interaction. | AB-MES buffer (pH 5.5): Critical for high efficiency in Arabidopsis (AGROBEST) [37]. |

Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression represents a versatile and powerful platform for accelerating gene function analysis in plants. As the comparative data and protocols in this guide demonstrate, optimized AMTE systems now exist for a wide range of species, from model plants like Arabidopsis to economically important crops like barley, strawberry, and citrus. The ability to rapidly screen and validate genes involved in complex biological processes, particularly disease resistance, makes AMTE an indispensable tool in the plant scientist's toolkit. By enabling high-throughput functional genomics directly in the plant of interest, often within a single week, AMTE significantly shortens the research timeline and provides robust preliminary data to inform subsequent stable transformation efforts or breeding strategies.

CRISPR/Cas Systems for Knockout, Knock-in, and Precise Gene Editing

In the context of plant disease resistance research, validating the function of a candidate gene requires precise genetic tools to directly link gene sequence to phenotypic outcome. CRISPR/Cas systems have emerged as a versatile toolkit for this purpose, enabling researchers to systematically dissect gene function through targeted knockout, knock-in, and precise editing approaches [28] [41]. Unlike traditional breeding or random mutagenesis, these technologies allow for specific manipulation of disease resistance genes and their regulatory elements in their native genomic context, providing direct causal evidence for gene function [28] [42].

The following comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of primary CRISPR/Cas editing modalities, with experimental data and methodologies specifically relevant to plant disease resistance studies.

Technology Comparison: Performance Metrics and Applications

Table 1: Performance comparison of major CRISPR/Cas editing modalities for plant research

| Editing Modality | Primary Mechanism | Typical Editing Efficiency in Plants | Key Applications in Disease Resistance Research | Technical Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Knockout (KO) | NHEJ repair introduces indels to disrupt gene function [28] | High (Up to 90% reported in maize T1 generation) [42] | Functional validation of susceptibility (S) genes and negative regulators of immunity [41] [43] | Low [44] |

| CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa) | dCas9 fused to transcriptional activators upregulates endogenous genes [28] | Moderate (e.g., 6.97-fold increase for Pv-lectin in bean hairy roots) [28] | Gain-of-function studies for pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) genes and PR genes [28] | Moderate to High [28] |

| Base Editing | Direct chemical conversion of one DNA base to another without DSBs [45] | Varies by system; generally high for specific point mutations | Fine-tuning resistance (R) gene specificity; modifying promoter elements [43] | Moderate [45] |

| Prime Editing | Reverse transcriptase template writes new sequence into target site [45] | Lower than KO but offers high precision | Precise installation of known resistance alleles; protein domain swapping [45] | High [45] |

Table 2: Empirical data from plant editing studies for disease resistance

| Plant Species | Target Gene(s) | Editing Technology | Outcome for Disease Resistance | Key Experimental Metric | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tomato | SlPR-1 | CRISPRa | Enhanced defense against Clavibacter michiganensis [28] | Targeted upregulation of pathogenesis-related gene [28] | [28] |

| Apple | MdDIPM4 | CRISPR Knockout | Improved disease resistance [41] | Gene inactivation [41] | [41] |

| Soybean | GmF3H1, GmF3H2, GmF3FNSII-1 | Multiplex CRISPR Knockout | Enhanced disease resistance [41] | Multiplex gene knockout [41] | [41] |

| Common Bean | PvD1, Pv-thionin, Pv-lectin | CRISPR-dCas9-6×TAL-2×VP64 | Upregulation of defense genes encoding antimicrobial peptides [28] | 6.97-fold increase for Pv-lectin [28] | [28] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Editing Modalities

Protocol for Multiplexed Knockout using a Plant CRISPR Toolkit

This protocol utilizes a modular vector system (e.g., pGreen or pCAMBIA backbones) for efficient assembly of multiple gRNA expression cassettes [44].

- gRNA Module Assembly: Select appropriate gRNA module vectors with Pol III promoters (e.g., AtU6-26p for dicots, OsU3p or TaU3p for monocots). Assemble multiple gRNA expression cassettes into a single binary vector using Golden Gate cloning with BsaI restriction enzyme [44].

- Vector Construction: Clone the assembled gRNA array and a maize-codon optimized Cas9 nuclease into a binary vector with a plant selectable marker (e.g., hygromycin, kanamycin, or Basta resistance) [44].

- Plant Transformation: Introduce the final construct into Agrobacterium tumefaciens and transform the plant species of interest using standard methods (e.g., floral dip for Arabidopsis, particle bombardment or Agrobacterium-mediated for monocots) [44].

- Mutation Analysis: Genotype T0 or T1 transgenic plants by PCR amplification of target regions and sequence the products to detect NHEJ-induced indels. Efficiency can be validated in protoplasts before stable transformation [44].

Protocol for CRISPRa-Mediated Gene Activation

This protocol describes a gain-of-function approach to validate positive regulators of disease resistance.

- System Design: Construct a binary vector expressing a deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) fused to transcriptional activator domains (e.g., VP64, TAL). The dCas9 retains target binding but lacks nuclease activity. Design gRNAs to target the promoter region of the candidate resistance gene [28].

- Delivery and Screening: Transform plants via Agrobacterium-mediated method (or use hairy root transformations for rapid validation in species like Phaseolus vulgaris). Select transgenic lines and quantify gene expression changes via RT-qPCR [28].

- Phenotypic Validation: Challenge the activated transgenic lines with the target pathogen and assess disease symptoms compared to controls. Metrics include lesion size, pathogen biomass, and expression of downstream defense markers [28].

Visualizing CRISPR Workflows and Pathways in Disease Resistance

The following diagrams illustrate core concepts and experimental workflows for using CRISPR/Cas systems in plant disease resistance research.

Diagram 1: A decision workflow for selecting the appropriate CRISPR modality based on the initial hypothesis about a candidate gene's role in disease resistance.

Diagram 2: This pathway illustrates how CRISPRa (yellow nodes) can be used to directly activate downstream defense genes, bypassing upstream signaling to validate their role in conferring disease resistance. This provides direct proof of a gene's contribution to the immune response.

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for CRISPR/Cas plant research

| Reagent / Solution | Critical Function | Example Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Variants | Catalyzes DNA cleavage or provides targeting scaffold | Maize-codon optimized zCas9 showed higher efficiency than human-codon versions in maize [44]. dCas9 is essential for CRISPRa [28]. |

| gRNA Module Vectors | Express guide RNAs for target recognition | Vectors with Pol III promoters (AtU6-26p, OsU3p, TaU3p); TaU3p showed superior performance in monocots [44]. |

| Binary Vector Systems | Agrobacterium-mediated delivery of editing machinery | pGreen (small size) or pCAMBIA (e.g., 1300/2300/3300 series with hygromycin, kanamycin, or Basta resistance) backbones [44]. |

| Programmable Transcriptional Activators (PTAs) | Fuse to dCas9 for gene activation in CRISPRa | Plant-specific PTAs (e.g., dCas9-6×TAL-2×VP64) are being developed to optimize CRISPRa efficiency [28]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticle Spherical Nucleic Acids (LNP-SNAs) | Novel delivery vehicle for editing components | Recent advancement (2025) shows 3x improved editing efficiency and reduced toxicity in human/mammalian cells; potential for future plant application [46]. |

| Bioinformatic Prediction Tools (e.g., Cas-OFFinder) | Identifies specific gRNA targets and predicts off-target sites | Critical for designing specific gRNAs; guides with ≥3 mismatches to other genomic sites, especially in the PAM-proximal region, minimized off-target effects in maize [42]. |

CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa) represents a powerful gain-of-function (GOF) tool that has revolutionized functional genomics in plant disease resistance research. Unlike traditional CRISPR-Cas9 editing that introduces double-stranded DNA breaks to disrupt gene function, CRISPRa employs a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to transcriptional activators to upregulate target genes without altering DNA sequences [28] [47]. This technology enables researchers to precisely control endogenous gene expression in its native genomic context, offering unprecedented opportunities for validating gene function in plant immunity pathways. As agricultural productivity faces increasing threats from pathogens and climate change, CRISPRa provides a sophisticated approach to elucidate defense mechanisms and develop durable disease resistance in crops [28] [48].

Core Mechanism and Technological Evolution

The fundamental CRISPRa system consists of dCas9 fused to transcriptional activation domains such as VP64, which is guided to specific promoter regions by single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) [47]. Upon binding to target DNA sequences, the activator domains recruit transcriptional machinery to initiate or enhance gene expression. This system has evolved significantly from early simple fusions to more sophisticated architectures that enhance activation efficiency:

Advanced CRISPRa Systems:

- SunTag System: Utilizes a protein scaffold with multiple copies of activator domains for enhanced recruitment [47] [49].

- SAM (Synergistic Activation Mediator): Employs an RNA scaffold with MS2 hairpins to recruit additional activation domains [49].

- VPR System: Combines three strong activation domains (VP64, p65, and Rta) in a single fusion protein [49].

These developments have addressed early limitations in activation strength, enabling robust transcriptional upregulation that is essential for studying dose-dependent defense responses in plants [28] [49].

Experimental Validation in Plant Disease Resistance

Case Study 1: Enhanced Bacterial Canker Resistance in Tomato

A recent groundbreaking study demonstrated the successful application of CRISPRa for enhancing resistance to Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis (Cmm), the causative agent of bacterial canker disease in tomato [50].

Experimental Protocol:

- Vector Design: Researchers fused the SET domain of the SlATX1 gene (a histone H3 lysine 4 tri-methyltransferase) to dCas12a (LbCpf1) to create an epigenetic activation system.

- Target Selection: The system was directed to the promoter region of SlPAL2, a key gene in the phenylpropanoid pathway responsible for lignin biosynthesis.

- Plant Transformation: Tomato explants were transformed via biolistics and regenerated through somatic embryogenesis.