Validating Gene Silencing Efficiency in Virus-Resistant Plants: From Foundational Mechanisms to Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on validating gene silencing efficiency, a critical defense mechanism in virus-resistant plants.

Validating Gene Silencing Efficiency in Virus-Resistant Plants: From Foundational Mechanisms to Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on validating gene silencing efficiency, a critical defense mechanism in virus-resistant plants. It covers the foundational principles of antiviral RNA interference (RNAi), explores established and emerging methodological approaches like Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) and Virus-Induced Genome Editing (VIGE), and addresses key troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Furthermore, it presents rigorous validation protocols and a comparative analysis with other gene-silencing technologies, offering a holistic framework for robust functional genomics and the development of next-generation disease-resistant crops.

The Plant's Arsenal: Unraveling Antiviral RNAi Mechanisms and Pathways

In the evolutionary arms race between plants and viruses, RNA interference (RNAi) has emerged as a fundamental defense mechanism, providing sequence-specific protection against viral pathogens. This sophisticated immune system operates through a conserved pathway where viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) is recognized and processed into the effector molecules that guide viral clearance [1] [2]. For researchers validating gene silencing efficiency in virus-resistant plants, understanding the core components of canonical antiviral RNAi—Dicer-like proteins (DCLs), Argonaute proteins (AGOs), and virus-derived small interfering RNAs (vsiRNAs)—is paramount. These elements form an integrated system that detects viral invasion, processes the infectious material into silencing signals, and executes targeted destruction of viral genomes. This guide examines the operational parameters of each component, compares their functional hierarchies, and presents established experimental protocols for quantifying their activity in plant-virus pathosystems.

Core Mechanism of Canonical Antiviral RNAi

The canonical antiviral RNAi pathway constitutes a multi-layered defense cascade that initiates upon viral detection and culminates in targeted viral genome degradation. Double-stranded RNA molecules, formed as viral replication intermediates or through base-pairing of viral transcripts, serve as the primary pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) that activates this system [3] [1]. The host's DCL enzymes recognize and process these dsRNAs into 21-24 nucleotide vsiRNAs, which are then loaded into AGO-containing RISCs. These activated complexes identify complementary viral RNA sequences through base-pairing and mediate their cleavage or translational inhibition [1] [4]. An amplification phase, dependent on host RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RDRs), generates secondary vsiRNAs to reinforce and systemically propagate the silencing signal, providing robust immunity throughout the plant [3] [5].

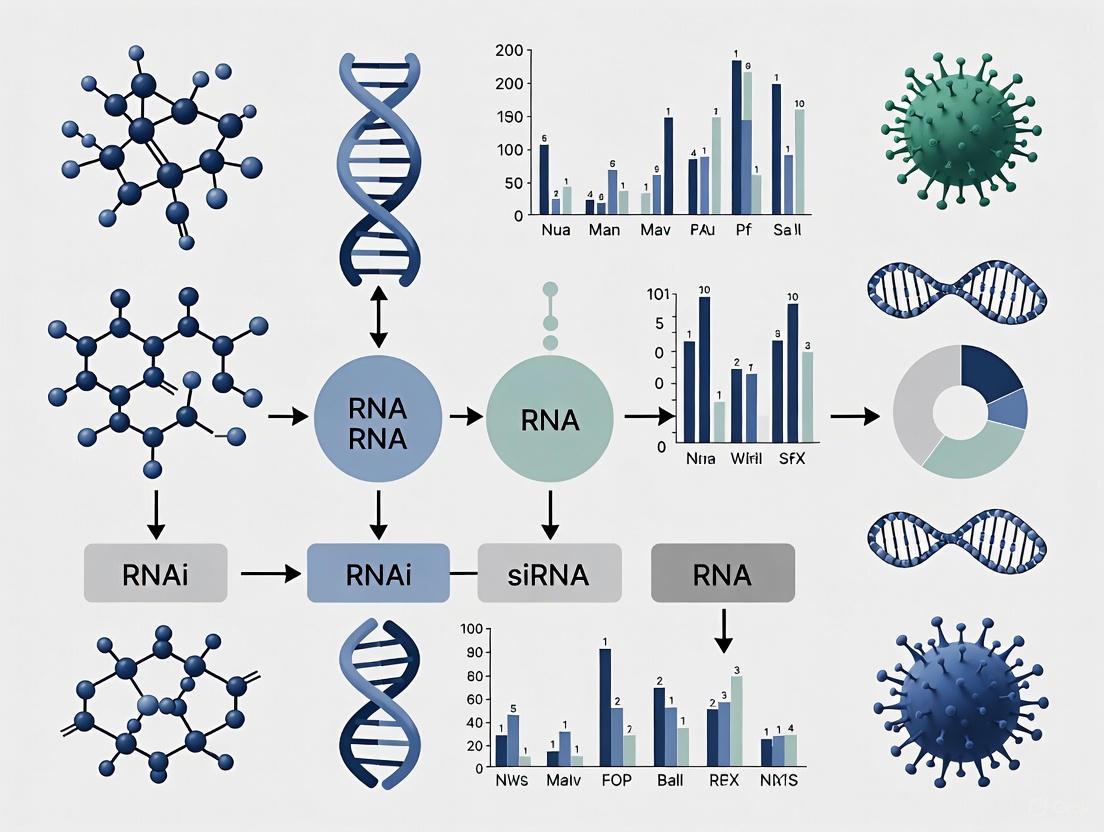

Figure 1: The Canonical Antiviral RNAi Pathway in Plants. This diagram illustrates the sequential phases of antiviral RNAi, from viral detection to systemic immunity. DCL processing of viral dsRNA generates vsiRNAs, which are loaded into AGO-containing RISC complexes to target complementary viral RNAs for degradation. RDR-mediated amplification generates secondary vsiRNAs to reinforce silencing.

Core Component Analysis: DCLs, AGOs, and vsiRNAs

Dicer-like (DCL) Proteins: Viral RNA Sensors and Processors

DCL proteins function as the primary sensors of viral infection, initiating the RNAi response by recognizing and cleaving viral dsRNA into vsiRNAs of specific lengths. In Arabidopsis thaliana, four DCL enzymes (DCL1-4) coordinate antiviral defense with distinct but partially overlapping functions [1] [6]. These large, multi-domain proteins contain conserved functional modules including DExD/H-box helicase domains for RNA unwinding, PAZ domains for recognizing dsRNA termini, tandem RNase III domains for catalytic cleavage, and dsRNA-binding domains (dsRBDs) for substrate interaction [1] [4].

Table 1: Comparative Functions of DCL Proteins in Antiviral Defense

| DCL Protein | Primary siRNA Product | Main Antiviral Role | Redundancy/Backup | Mutant Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCL4 | 21-nt vsiRNAs | Primary defense against RNA viruses | - | Enhanced susceptibility to RNA viruses |

| DCL2 | 22-nt vsiRNAs | Secondary defense when DCL4 compromised | Backups DCL4 against some viruses | Mild susceptibility alone; enhanced with dcl4 mutation |

| DCL3 | 24-nt vsiRNAs | Defense against DNA viruses via RdDM | - | Enhanced susceptibility to DNA viruses |

| DCL1 | 21-nt miRNAs | Indirect regulation via miRNA biogenesis | Promotes DCL4 activity | Developmental defects; altered viral susceptibility |

DCL4 serves as the primary antiviral DCL against RNA viruses, processing viral dsRNA into 21-nucleotide vsiRNAs [1] [6]. DCL2 acts as a backup processor that generates 22-nt vsiRNAs when DCL4 is inhibited or compromised, ensuring robust antiviral protection [1]. In tomato, specific DCL2 homologs (DCL2b) play particularly vital roles against viruses like tomato mosaic virus [1] [6]. DCL3 produces 24-nt vsiRNAs that direct transcriptional silencing of DNA viruses through the RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway [3] [1]. Although DCL1 primarily generates miRNAs for endogenous gene regulation, it indirectly influences antiviral defense by regulating the expression of RNAi components and potentially facilitating other DCL activities [1] [6].

Argonaute (AGO) Proteins: Effector Complex Assemblers

AGO proteins form the catalytic core of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), serving as the executors of antiviral RNAi. These multidomain proteins bind vsiRNAs and use them as guides to identify complementary viral RNA targets [1] [4]. The AGO protein family in plants is diverse, with Arabidopsis encoding 10 AGOs that exhibit functional specialization based on their domain architecture and small RNA binding preferences [5].

Table 2: Antiviral Functions of Major AGO Proteins

| AGO Protein | Loaded siRNA Size | Mechanism of Action | Key Viral Targets | Specialized Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGO1 | 21-nt vsiRNAs | PTGS via mRNA cleavage | RNA viruses | Primary antiviral AGO; redundant with AGO2 |

| AGO2 | 21-nt, 22-nt vsiRNAs | PTGS via mRNA cleavage | RNA viruses | Inducible by viral infection; key against some viruses |

| AGO5 | 21-nt vsiRNAs | PTGS via mRNA cleavage | - | Contributes to antiviral defense |

| AGO7 | 21-nt vsiRNAs | PTGS via mRNA cleavage | - | Specialized in tasiRNA pathway |

| AGO4 | 24-nt vsiRNAs | TGS via RdDM | DNA viruses | Transcriptional silencing of viral minichromosomes |

AGO1 and AGO2 serve as the primary antiviral effectors against RNA viruses, both loading 21-nt vsiRNAs to direct post-transcriptional silencing of viral RNAs [5]. AGO2 expression is often induced by viral infection, suggesting a particularly important role in inducible antiviral defense [5]. For DNA viruses, AGO4 associates with 24-nt vsiRNAs to recruit DNA methyltransferases to viral minichromosomes, enabling transcriptional gene silencing through RdDM [3] [5]. The functional specialization of AGO proteins is influenced by the 5' nucleotide of the vsiRNA and specific amino acid residues in the MID domain that facilitate small RNA sorting [4].

Virus-derived Small Interacting RNAs (vsiRNAs): Specificity Determinants

vsiRNAs represent the specificity determinants of antiviral RNAi, providing the sequence guidance system that enables targeted viral RNA degradation. These 21-24 nucleotide RNAs are generated from perfectly base-paired regions of viral dsRNA through the sequential cleavage activities of DCL enzymes [3] [1]. Unlike mammalian systems, plant vsiRNAs are typically methylated at their 3' termini by HEN1 methyltransferase to enhance stability and prevent uridylation [1].

During viral infection, vsiRNAs are produced from nearly all regions of viral genomes, though certain hotspots—such as highly structured regions or replication origins—often yield abundant vsiRNA populations [7]. These vsiRNAs are dichotomized into primary vsiRNAs (derived directly from viral dsRNA processing) and secondary vsiRNAs (amplified by RDR activities using viral transcripts as templates) [3] [5]. The amplification of silencing signals through RDR6-mediated secondary vsiRNA production is particularly important for systemic silencing and robust antiviral immunity [3].

Experimental Framework for Analyzing Antiviral RNAi Components

Standardized Protocols for Component Validation

Genetic mutant analysis provides the most direct approach for validating the function of core RNAi components in antiviral defense. Using T-DNA insertion lines or CRISPR-Cas9 mutants, researchers can quantify viral accumulation in dcl, ago, or rdr mutants compared to wild-type plants [1] [8]. For example, infection of dcl2/dcl4 double mutants with turnip crinkle virus results in significantly enhanced viral accumulation and more severe disease symptoms compared to single mutants, revealing functional redundancy [1].

Small RNA sequencing represents a powerful methodology for vsiRNA profiling that enables researchers to quantify vsiRNA abundance, size distribution, and genomic origins [7]. The standard protocol involves: (1) extraction of total small RNAs (<200 nt) from virus-infected tissues using silica-based columns; (2) library preparation with adapters ligated to the 3' and 5' ends of small RNAs; (3) high-throughput sequencing (50-75 bp single-end reads); (4) bioinformatic analysis including adapter trimming, alignment to viral and host genomes, and size distribution profiling [7].

Northern blot analysis remains the gold standard for validating vsiRNA production and processing. This method involves: (1) separation of small RNAs in denaturing polyacrylamide gels (15%); (2) electrophoretic transfer to nylon membranes; (3) UV cross-linking; (4) hybridization with biotin- or isotope-labeled DNA/RNA probes complementary to specific vsiRNAs; (5) detection by chemiluminescence or autoradiography [7]. Northern analysis confirmed the identity of three highly abundant RSV-derived vsiRNAs sharing 11 nucleotide conserved sequences [7].

RISC immunoprecipitation assays enable researchers to characterize AGO-vsiRNA associations and identify the specific viral RNAs being targeted. The standard protocol includes: (1) tissue fixation with formaldehyde to crosslink AGO proteins to bound RNAs; (2) cell lysis under denaturing conditions; (3) immunoprecipitation with AGO-specific antibodies; (4) proteinase K treatment to reverse crosslinks; (5) RNA extraction and library preparation for sequencing [5].

Research Reagent Solutions for Antiviral RNAi Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Antiviral RNAi Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Resources | dcl2/dcl4 double mutants, ago1/ago2 mutants, rdr1/rdr6 mutants | Functional validation | Determine component necessity and redundancy in antiviral defense |

| Viral Constructs | VSR-deficient mutants (e.g., FHVΔB2, CMVΔ2b), Reporter viruses | Pathosystem establishment | Enable specific study of RNAi without suppression interference |

| Detection Tools | AGO-specific antibodies, Biotin-labeled LNA probes, HEN1 antibodies | Protein and sRNA analysis | Immunoprecipitation, Northern blotting, protein localization |

| Sequencing Kits | Small RNA library prep kits, Strand-specific RNA-seq kits | High-throughput analysis | vsiRNA profiling, transcriptome analysis of infected tissues |

| Plant Pathosystems | Arabidopsis-TuMV, Arabidopsis-CMV, Tobacco-TMV | Standardized assays | Well-characterized systems for comparative RNAi studies |

The canonical antiviral RNAi pathway represents a sophisticated, integrated defense system wherein DCLs, AGOs, and vsiRNAs function coordinately to detect and neutralize viral pathogens. The functional hierarchy begins with DCL-mediated recognition and processing of viral dsRNAs into vsiRNAs, which are then loaded into AGO-containing RISC complexes to direct sequence-specific viral RNA clearance. This system incorporates substantial functional redundancy (particularly among DCL4/DCL2 and AGO1/AGO2 pairs) that ensures robust immunity even when individual components are compromised.

For researchers engineering virus-resistant crops, key considerations include the expression levels of multiple AGO and DCL genes, the efficiency of vsiRNA biogenesis from target viruses, and the subcellular localization of these components at sites of viral replication. The experimental frameworks outlined herein provide standardized methodologies for quantifying the activity of each RNAi component and assessing the efficacy of engineered resistance strategies. As viral suppressors of RNAi (VSRs) continue to present the foremost challenge to deploying RNAi-based resistance, understanding these core principles enables researchers to develop innovative approaches that bypass or neutralize VSR activity, ultimately leading to more durable and broad-spectrum virus resistance in crop plants.

RNA interference (RNAi) and RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) represent fundamental antiviral defense mechanisms in plants. While the canonical pathways of these processes are well-established, recent research has uncovered non-canonical variations that expand our understanding of plant-virus interactions. This guide provides a comparative analysis of canonical and non-canonical RNAi/RdDM pathways, detailing their distinct mechanisms, components, and functional outcomes. We present experimental data validating the efficiency of these silencing pathways and summarize key methodologies for investigating non-canonical routes, providing researchers with practical tools for advancing antiviral strategies in crop plants.

The classical view of RNAi in plants involves a well-defined pathway where Dicer-like (DCL) proteins process double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) into small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) that guide Argonaute (AGO) proteins to silence complementary viral sequences [3] [9]. Similarly, the canonical RdDM pathway utilizes DCL3-dependent 24-nt siRNAs loaded into AGO4 to direct DNA methylation and transcriptional silencing of viral genomes [3]. However, mounting evidence reveals that plants employ more complex and diverse silencing strategies than previously recognized.

Non-canonical RNAi pathways deviate from these established mechanisms, utilizing different biogenesis pathways, producing atypical small RNA species, or employing alternative effector proteins [3] [10]. These non-canonical routes expand the plant's antiviral arsenal and represent promising targets for enhancing viral resistance in crops. Understanding both canonical and non-canonical pathways is essential for comprehensively validating gene silencing efficiency in virus-resistant plants, as these pathways may operate simultaneously or conditionally depending on the viral pathogen and host context.

Comparative Analysis of Canonical vs. Non-Canonical Pathways

The distinction between canonical and non-canonical RNAi/RdDM pathways lies in their mechanisms, components, and functional outcomes. The tables below summarize the key differences between these pathways based on current research findings.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Canonical and Non-Canonical RNAi Pathways

| Feature | Canonical RNAi | Non-Canonical RNAi |

|---|---|---|

| Trigger Molecule | Viral replication intermediates, perfectly paired dsRNA [3] | Exogenously applied dsRNA, convergent transcripts, atypical dsRNA structures [3] [10] |

| Key Processing Enzymes | DCL2 (22-nt), DCL4 (21-nt) [3] | Non-canonical nucleases, alternative DCL processing [10] [11] |

| sRNA Products | Discrete 21-nt and 22-nt siRNA species [3] [10] | sRNA ladders (~18-30 nt), non-discrete size distribution [3] [10] |

| Effector Complex | AGO1/AGO2 with 21-22nt siRNAs [3] | Potential loading of non-canonical sRNAs into AGOs, functional status unclear [3] |

| Systemic Spread | Efficient cell-to-cell and long-distance movement [3] | Limited systemic movement [10] |

| Amplification | RDR6-dependent secondary siRNA amplification [3] [9] | No transitive amplification [10] |

| Antiviral Efficiency | Strong, sequence-specific viral RNA degradation [3] | Variable efficiency, mechanism not fully understood [10] |

Table 2: Comparative Features of Canonical and Non-Canonical RdDM Pathways

| Feature | Canonical RdDM | Non-Canonical RdDM |

|---|---|---|

| Key Initiating Polymerase | Pol IV [3] | Pol II [3] |

| sRNA Biogenesis | DCL3-dependent 24-nt siRNAs [3] | miRNA-directed, RDR6-dependent, or DCL3-processing of RDR6 products [3] |

| Effector Complex | AGO4 with 24-nt siRNAs [3] [12] | AGO4/RISC with non-canonical sRNAs [3] |

| Methyltransferase Recruitment | DRM2 via AGO4-Pol V interaction [12] | Likely DRM2 via alternative recruitment [3] |

| Genomic Targets | Heterochromatic regions, transposons [3] | Inverted repeats, miRNA targets, protein-coding genes [3] |

| Antiviral Application | Methylation of DNA virus genomes [12] | Potential methylation of viral genomes, not fully characterized [3] |

Experimental Validation of Non-Canonical Pathways

Key Experimental Evidence

Several critical studies have provided empirical evidence for the existence and function of non-canonical RNAi pathways:

3.1.1 Non-canonical sRNA Biogenesis from Exogenous dsRNA A pivotal study investigating the mechanism of spray-induced gene silencing (SIGS) revealed striking differences in small RNA biogenesis when comparing natural viral infection versus externally applied dsRNA. In potato plants infected with potato virus Y (PVY), canonical 21-nt and 22-nt viral siRNAs (vsiRNAs) were produced. In contrast, when PVY-derived dsRNA was externally applied, it generated a non-canonical pool of sRNAs appearing as ladders of ~18-30 nt in length, suggesting an unexpected sRNA biogenesis pathway [10]. These non-canonical sRNAs demonstrated limited systemic movement and did not undergo transitive amplification, indicating fundamental mechanistic differences from canonical RNAi [10].

3.1.2 Non-canonical RdDM Mechanisms Research has identified several RdDM pathways that deviate from the classical Pol IV-RDR2-DCL3-AGO4 axis. These include:

- Inverted repeat- and miRNA-directed DNA methylation: RNA polymerase II transcripts are directly cleaved by DCL3 into 24-nt sRNAs that participate in RdDM [3].

- RDR6-RdDM pathway: 21-22nt siRNAs produced during post-transcriptional gene silencing from Pol II transcripts and processed by DCL2 or DCL4 can activate RISCs that engage in RdDM [3].

- RDR6-DCL3 RdDM pathway: RDR6-mediated dsRNA synthesis followed by DCL3 processing into 24-nt siRNAs that associate with the RdDM pathway [3].

These non-canonical RdDM pathways are primarily distinguished by variations in the steps leading to siRNA biogenesis and may have significant implications for antiviral defense [3].

3.1.3 Conservation in Fungal Systems Non-canonical RNAi pathways are evolutionarily conserved, as demonstrated in fungal systems. In Mucor circinelloides, a non-canonical RNAi pathway (NCRIP) controls virulence and genome stability. This pathway relies on RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRPs) and a novel ribonuclease III-like protein named R3B2—rather than Dicer enzymes—to degrade target transcripts [11]. In the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae, Dicer-independent sRNAs present irregular patterns in length distribution, high strand-specificity, and a preference for cytosine at the penultimate position, unlike their canonical counterparts [13].

Experimental Protocols for Pathway Analysis

To validate the efficiency of gene silencing through both canonical and non-canonical pathways, researchers can employ the following methodologies:

3.2.1 Small RNA Sequencing for Pathway Characterization

- Purpose: To identify and characterize small RNA populations resulting from canonical versus non-canonical processing.

- Method Details: Extract total RNA from virus-infected plants or dsRNA-treated tissues using methods that enrich for small RNAs. Prepare sequencing libraries with protocols that capture the full size range of small RNAs (18-30 nt). Use high-throughput sequencing with sufficient depth to detect low-abundance sRNA species.

- Data Analysis: Bioinformatically separate sRNAs by size distribution. Canonical pathways typically yield sharp peaks at 21-nt and 22-nt sizes, while non-canonical processing produces a broader size range (~18-30 nt) [13] [10]. Analyze 5'-nucleotide preferences and strand-specificity, as these differ between canonical and non-canonical sRNAs [13].

- Validation: Compare sRNA profiles from wild-type plants and RNAi pathway mutants (e.g., dcl2/dcl4 double mutants for canonical pathway disruption) to confirm the involvement of specific processing enzymes.

3.2.2 Bisulfite Sequencing for RdDM Activity

- Purpose: To assess DNA methylation levels at viral genome sequences directed by canonical versus non-canonical RdDM pathways.

- Method Details: Treat genomic DNA from infected or dsRNA-treated plants with bisulfite to convert unmethylated cytosines to uracils. Perform PCR amplification and deep sequencing of viral DNA regions. Analyze conversion rates to determine methylation status at CG, CHG, and CHH contexts [12].

- Pathway Differentiation: Combine bisulfite sequencing with mutants of canonical (e.g., dcl3, ago4) and non-canonical (e.g., rdr6) pathway components to determine which pathway mediates antiviral methylation.

3.2.3 Viral Suppressor Localization Studies

- Purpose: To investigate how viral proteins suppress different RNA silencing pathways.

- Method Details: Express fluorescently tagged viral suppressors (e.g., TYLCV V2 protein) and host proteins (e.g., AGO4) in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves via agroinfiltration. Use co-immunoprecipitation and split-luciferase assays to confirm protein-protein interactions [12]. Employ Cajal body markers (e.g., coilin) to determine subnuclear localization.

- Application: Demonstrated for TYLCV V2, which interacts with AGO4 in Cajal bodies to suppress methylation of the viral genome [12].

Pathway Visualization and Mechanisms

Figure 1: Comparative overview of canonical antiviral RNAi, non-canonical RNAi, and canonical RdDM pathways in plants. Non-canonical RNAi (red) differs from canonical RNAi (blue) in processing, sRNA products, and functional outcomes. Potential crosstalk between non-canonical sRNAs and RdDM components is indicated with a dashed line.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Non-canonical RNAi/RdDM Pathways

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| DCL Mutants | Arabidopsis dcl2/dcl4 double mutants, dcl3 single mutants [3] | Pathway requirement analysis | Determining processing enzyme dependencies for sRNA biogenesis |

| AGO Lines | N. benthamiana AGO4-silenced lines, ago4 mutants [12] | Effector complex analysis | Assessing AGO protein requirements in silencing pathways |

| RdRP Mutants | M. oryzae ΔMoerd-1, M. circinelloides rdrp1Δ [13] [11] | Amplification mechanism studies | Investigating role in secondary siRNA production and non-canonical degradation |

| Viral Clones | TYLCV V2 null mutant (TYLCV-V2null) [12] | Viral suppressor studies | Dissecting viral counter-defense mechanisms against RNAi/RdDM |

| sRNA Sequencing Kits | Commercial small RNA library prep kits | sRNA profiling | Characterizing size distribution and abundance of canonical vs. non-canonical sRNAs |

| Methylation Analysis | Bisulfite conversion kits, DRM2 antibodies [12] | DNA methylation assessment | Measuring RdDM activity at viral genomes |

The expanding landscape of non-canonical RNAi and RdDM pathways reveals a remarkable complexity in plant antiviral defense systems. While canonical pathways provide well-established, efficient silencing mechanisms, non-canonical routes offer alternative strategies that may operate under specific conditions or against particular viral pathogens.

From a practical perspective, understanding these non-canonical pathways opens new avenues for engineering viral resistance in crops. The non-canonical processing of externally applied dsRNA, despite its current limitations in systemic movement and amplification, presents opportunities for developing non-transgenic crop protection strategies through SIGS technology [10]. Similarly, leveraging non-canonical RdDM pathways could enhance resistance to DNA viruses by diversifying the methylation targeting mechanisms beyond the canonical Pol IV pathway.

For researchers validating gene silencing efficiency in virus-resistant plants, these findings underscore the importance of comprehensive analysis that accounts for both canonical and non-canonical pathways. Reliance solely on canonical pathway markers may overlook significant components of the plant's antiviral defense system. Future research should focus on elucidating the precise mechanisms of non-canonical sRNA biogenesis, their loading into effector complexes, and strategies to enhance their efficiency for crop protection applications.

RNA interference (RNAi) serves as a fundamental antiviral defense mechanism in plants, triggering sequence-specific degradation of viral RNAs. In response, plant viruses have evolved sophisticated counter-defense strategies, primarily through the expression of RNA Silencing Suppressors (RSS). These viral proteins employ diverse molecular tactics to inhibit various stages of the RNAi pathway, enabling viral proliferation and systemic infection. This review comprehensively compares the mechanisms and efficiencies of characterized RSS proteins, detailing experimental approaches for their study, and provides essential resources for ongoing research into the molecular arms race between plants and viral pathogens.

RNA interference (RNAi), also known as RNA silencing, represents one of the most crucial plant defense responses against viral invasion [3]. This conserved mechanism recognizes and targets viral nucleic acids through a sequence-specific process. The canonical antiviral RNAi pathway initiates when viral RNAs or their replication intermediates form double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) structures. Host DICER-like (DCL) proteins, specifically DCL2, DCL3, and DCL4, recognize and cleave these viral dsRNAs into virus-derived small interfering RNAs (vsiRNAs) of 21–24 nucleotides in length [3]. These vsiRNAs are then loaded into Argonaute (AGO) proteins to form RNA-induced silencing complexes (RISCs), which guide the cleavage or translational repression of complementary viral RNA transcripts through post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) [3]. Additionally, a transcriptional gene silencing (TGS) branch exists where 24-nt vsiRNAs direct RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) of viral DNA through DCL3 and AGO4 [3]. To amplify the silencing signal, plant RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RDRs), with the assistance of Suppressor of Gene Silencing 3 (SGS3), synthesize secondary dsRNAs using aberrant viral RNAs as templates, generating secondary vsiRNAs that reinforce the antiviral defense [3].

RSS Mechanisms: A Comparative Analysis of Viral Counter-Defense Strategies

During the co-evolutionary arms race with their hosts, nearly all plant viruses have developed counter-defense strategies, most notably through viral RSS proteins that antagonize the host RNAi machinery [3] [14]. These RSS proteins employ diverse molecular tactics to disrupt various stages of antiviral silencing, and their comparative mechanisms are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparative Mechanisms of Characterized RNA Silencing Suppressors (RSS)

| Viral RSS | Source Virus | Target Stage/Component | Molecular Mechanism | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC-Pro | Potyviruses (e.g., BBrMV, PVY) | siRNA amplification | Binds to and inhibits RDR6/SGS3 complex; sequesters siRNAs | In vitro binding assays; transgenic plants showing suppressed silencing [3] [15] |

| P19 | Tombusviruses | siRNA loading | Binds 21-nt siRNAs with high affinity, preventing RISC assembly | Structural studies (X-ray crystallography); siRNA binding assays [14] |

| 2b | Cucumber Mosaic Virus (CMV) | RISC function | Binds to and inhibits AGO1 catalytic activity | Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP); AGO1 cleavage assays [14] [15] |

| Tat | HIV-1 (Animal Virus) | siRNA biogenesis | Binds to Dicer through its basic/RNA-binding domain, inhibiting dsRNA processing | Co-IP; Dicer activity assays in mammalian cells [16] |

| NS1 | Influenza A Virus | siRNA binding | Sequesters siRNAs via dsRNA-binding domain | siRNA binding assays; functional studies in plants and insect systems [16] |

| CP, MP, Clink, NSP | Banana Bunchy Top Virus (BBTV) | Multiple targets | CP, MP, Clink act as RSS; NSP blocks host kinase activity | Transcriptomic analysis; protein-protein interaction studies [15] |

dsRNA Sequestration and Disruption of vsiRNA Biogenesis

Some RSS proteins function by directly binding to dsRNA substrates or interfering with DCL activities. For instance, the Influenza A virus NS1 protein and Vaccinia virus E3L protein contain dsRNA-binding domains that enable them to sequester dsRNA molecules, preventing their recognition and processing by DCL enzymes into vsiRNAs [16]. Similarly, the HIV-1 Tat protein suppresses RNAi by directly binding to the helicase domain of Dicer, thereby inhibiting its dicing activity and the production of mature vsiRNAs [16].

vsiRNA Sequestration

A common strategy among plant viral RSS is the direct binding and sequestration of vsiRNAs. The P19 protein from tombusviruses employs a "molecular ruler" mechanism, forming a head-to-tail homodimer that specifically binds the characteristic 21-nucleotide duplex siRNAs with high affinity, preventing their incorporation into RISC [14]. This effectively neutralizes the silencing signal without affecting miRNA pathways that utilize different AGO proteins.

Inhibition of RISC Assembly and Function

Viral suppressors can directly target the effector complex of RNAi. The 2b protein from Cucumber Mosaic Virus (CMV) inhibits AGO1 catalytic activity, the primary slicer enzyme in antiviral defense [14] [15]. Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) envelope E2 protein and core protein have also been shown to bind and inhibit AGO2 and Dicer, respectively, in mammalian systems, highlighting the evolutionary conservation of this targeting strategy across kingdoms [16].

Interference with Amplification and Systemic Signaling

Many viruses disrupt the amplification of the silencing signal. The HC-Pro protein from potyviruses, including Banana bract mosaic virus (BBrMV), inhibits the RDR6/SGS3-mediated amplification of secondary vsiRNAs [3] [15]. This not only weakens the local defense but also prevents the generation of mobile silencing signals that confer systemic resistance in distant tissues.

Experimental Protocols for RSS Characterization

The identification and functional characterization of RSS proteins rely on a suite of established molecular and biochemical assays. The workflow for RSS characterization, from initial screening to mechanistic studies, is outlined in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for identifying and characterizing RNA Silencing Suppressors (RSS).

Primary Screening: Agroinfiltration Assays

Objective: To rapidly assess potential RSS activity in plant leaves. Protocol:

- Clone the candidate viral gene into a binary expression vector (e.g., pBIN61 or pEAQ) under a strong promoter like the Cauliflower Mosaic Virus 35S (CaMV 35S).

- Infiltrate Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains harboring the RSS construct, along with a reporter silencing system (e.g., GFP), into Nicotiana benthamiana leaves.

- Co-infiltrate with a known silencing trigger, such as a GFP double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) or an inverted repeat construct.

- Monitor fluorescence intensity over 3-7 days using UV illumination or a laser scanner. Sustained GFP fluorescence compared to the control (infiltrated with an empty vector) indicates suppression of RNA silencing [3] [15].

- Quantify the efficiency of suppression by measuring the percentage of leaf area retaining fluorescence or by quantifying GFP mRNA levels using RT-qPCR.

Protein-Protein Interaction Studies

Objective: To identify host RNAi components targeted by the RSS protein. Protocol:

- Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP):

- Express epitope-tagged RSS (e.g., FLAG-RSS) and potential host interaction partners (e.g., AGO1, Dicer) in plant leaves or protoplasts.

- Lyse the plant tissue and incubate with an anti-FLAG antibody conjugated to beads.

- Wash the beads extensively, elute the bound proteins, and analyze by immunoblotting to detect co-precipitated host factors [17] [16].

- Luciferase Complementation Imaging (LCI):

- Fuse the RSS protein to the N-terminal fragment of luciferase (nLUC) and the candidate host protein to the C-terminal fragment (cLUC).

- Co-express both constructs in N. benthamiana leaves. An interaction reconstructs the luciferase enzyme, producing a bioluminescent signal detectable after luciferin application [17].

Nucleic Acid Binding Assays

Objective: To determine if the RSS binds dsRNA or siRNAs. Protocol:

- Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA):

- Purify the recombinant RSS protein.

- Incubate the protein with radiolabeled or fluorescently-labeled dsRNA or siRNAs of varying lengths.

- Resolve the protein-RNA complexes on a native polyacrylamide gel.

- A reduction in RNA mobility (band shift) indicates direct binding. Include unlabeled competitor RNA to demonstrate binding specificity [16].

- Microscale Thermophoresis (MST):

- Label the siRNA or dsRNA with a fluorescent dye.

- Mix the labeled RNA with a serial dilution of the purified RSS protein.

- Load the mixture into capillary tubes and measure the change in fluorescence as a temperature gradient is applied.

- The change in thermophoretic behavior is used to calculate the binding affinity (dissociation constant, Kd) [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful investigation of RSS function requires specific biological and chemical reagents, as cataloged in Table 2.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for RSS and Antiviral RNAi Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Vectors | Delivery and functional analysis of RSS genes in plants | Potato Virus X (PVX), Turnip Mosaic Virus (TuMV), Cucumber Mosaic Virus (CMV) [3] [18] |

| Agrobacterium Strains | Transient expression of genes in plant tissues (Agroinfiltration) | GV3101, LBA4404 [15] |

| Binary Vectors | Cloning and expression of candidate RSS genes | pBIN61, pEAQ-HT (for high-level protein expression) [18] |

| Reporter Systems | Visualizing RNA silencing suppression | GFP, β-glucuronidase (GUS); used in co-infiltration assays [15] |

| Model Plants | In vivo functional studies | Nicotiana benthamiana, Arabidopsis thaliana [3] |

| Antibodies | Detection and purification of tagged proteins and viral components | Anti-FLAG, Anti-GFP, Anti-Myc; virus-specific CP antibodies [17] |

| sRNA Sequencing | Profiling vsiRNA and miRNA populations; assessing RSS impact | High-throughput sequencing of 18-30 nt RNAs from infected vs. healthy plants [3] |

RNA Silencing Suppressors represent a critical adaptation in the ongoing molecular arms race between plants and viruses. Their diverse mechanisms of action, targeting nearly every step of the antiviral RNAi pathway, highlight the evolutionary pressure on viruses to overcome host defenses. The continued development and application of robust experimental protocols—from agroinfiltration-based screening to detailed mechanistic studies of protein and nucleic acid interactions—are essential for uncovering novel RSS factors and understanding their function. This knowledge not only deepens our fundamental understanding of plant-virus interactions but also informs the development of innovative strategies for engineering durable virus resistance in crops, such as deploying CRISPR/Cas systems to disrupt RSS genes or engineer resistant AGO variants.

In the ongoing effort to validate gene silencing efficiency in virus-resistant plants, understanding the mobility of RNA silencing signals is a fundamental pursuit. For engineered resistance to be effective, the initial silencing trigger must not only activate locally but also spread systemically throughout the plant, conferring comprehensive protection against viral pathogens. This cell-to-cell and long-distance movement of silencing represents a sophisticated biological communication system that researchers are only beginning to fully decipher. The phenomenon, known as systemic RNA interference (RNAi), enables a localized virus infection to induce silencing that protects the entire plant, a critical feature for developing durable resistance in crops. This article examines the mechanisms underlying this mobility and compares the experimental approaches used to study them, providing researchers with a framework for assessing silencing efficiency in virus-resistant plants.

Mechanisms of Silencing Signal Movement

The Core Pathway: From Viral Trigger to Systemic Immunity

The antiviral RNAi pathway in plants is initially triggered when viral RNAs form double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) structures through inter- or intramolecular base pairing [3]. These dsRNAs are recognized and processed by Dicer-like (DCL) proteins into 21-24 nucleotide virus-derived small interfering RNAs (vsiRNAs) [3]. These vsiRNAs are then loaded onto Argonaute (AGO) proteins to form RNA-induced silencing complexes (RISCs) that guide the sequence-specific degradation of complementary viral RNAs [3]. For the silencing signal to become systemic, this initial response must be amplified and transported.

The core mechanism for signal amplification involves RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RDRs), particularly RDR6, which synthesize secondary dsRNAs using aberrant viral single-stranded RNAs as templates [3]. These secondary dsRNAs are processed into additional vsiRNAs, creating an amplified silencing response that can spread throughout the plant. Research has demonstrated that antiviral RNAi signaling molecules move from cell-to-cell and leaf-to-leaf, thereby initiating systemic antiviral RNAi in distant, initially uninfected plant tissues [3].

Plasmodesmata and Movement Proteins: Gateways for Signal Transport

The physical conduits for cell-to-cell movement of silencing signals are plasmodesmata (PD), the intercellular channels that connect neighboring plant cells [19]. These microchannels are dynamically regulated to control the size exclusion limit (SEL), determining which molecules can pass through. Studies have shown that viral movement proteins (MPs) often increase the PD SEL, facilitating both viral movement and potentially the spread of silencing signals [19].

The Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) MP serves as a prototypical model for understanding these processes. TMV MP binds RNA, associates with viral replication compartments, and increases PD conductivity through multiple mechanisms: (1) remodeling the internal PD structure by interacting with PD-resident protein SYT1; (2) activating callose-degrading enzymes to reduce callose depositions at PD neck regions; and (3) suppressing defense-related signaling that leads to enhanced callose deposition [19]. These PD modifications create pathways through which silencing signals can travel between cells.

Research has demonstrated that this system is so fundamental that TMV MP can even complement the movement of viroids - non-coding infectious RNAs that lack their own movement proteins. A mutant Potato spindle tuber viroid (PSTVd) with impaired movement capability had its transport between epidermal and palisade mesophyll cells restored when TMV MP was provided [19]. This highlights the critical role of MP-mediated transport in systemic silencing spread.

Experimental Approaches for Studying Systemic Silencing

Comparative Analysis of Methodologies

Researchers employ diverse experimental systems to investigate the mobility of silencing signals, each with distinct advantages and applications. The table below summarizes key approaches and their experimental readouts.

Table 1: Experimental Approaches for Studying Systemic Silencing

| Method | Key Components | Experimental Readouts | Applications in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) | TRV, BPMV, WDV viral vectors; Agrobacterium delivery [20] [21] | Silencing efficiency (65-95%); Phenotypic changes; qPCR validation [21] | Functional genomics; Validation of resistance genes [20] |

| Trans-complementation Assays | Heterologous movement proteins; Movement-deficient viruses [19] | Restoration of cell-to-cell movement; Tissue-specific silencing patterns | Studying MP functions; PD gating mechanisms [19] |

| High-Throughput Sequencing | Small RNA libraries; Bioinformatics analysis [22] | vsiRNA profiles (21-24nt); Distribution patterns; Mutation rates | Discovery of novel pathways; Viral evolution studies [3] |

| Exogenous dsRNA Application | Engineered dsRNAs; Spray-based delivery [23] | Protection rates (80-100%); Viral titer reduction; Symptom severity | Crop protection; Field-scale applications [23] |

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) Systems

VIGS has become a powerful tool for studying systemic silencing due to its ability to down-regulate endogenous genes through the plant's post-transcriptional gene silencing machinery [20]. Different viral vectors offer unique advantages:

The Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV) system has been optimized for soybean through Agrobacterium-mediated infection of cotyledon nodes, achieving 65-95% silencing efficiency [21]. The protocol involves:

- Cloning target gene fragments (e.g., GmPDS, GmRpp6907) into pTRV2-GFP vector

- Transforming into Agrobacterium GV3101

- Infecting half-seed explants via immersion for 20-30 minutes

- Monitoring systemic spread through fluorescence and phenotypic changes [21]

The Wheat Dwarf Virus (WDV) system has been successfully adapted for rice, demonstrating rapid infection, high proliferation, and minimal impact on plant development [20]. Key steps include:

- Inserting target sequences (OsPDSi, OsPi21i) into SpeI and StuI restriction sites

- Delivering via vacuum infiltration or friction inoculation

- Validating through qRT-PCR and phenotypic assessment (e.g., photobleaching, disease resistance) [20]

These VIGS systems enable researchers to track the movement of silencing signals from initial infection sites to distal tissues, providing insights into the kinetics and efficiency of systemic spreading.

Advanced Detection and Imaging Methods

Cutting-edge approaches combine molecular techniques with visualization methods to directly observe silencing movement:

High-throughput small RNA sequencing allows researchers to map the distribution and abundance of vsiRNAs throughout the plant, revealing how silencing signals propagate [24]. In studies of mixed viral infections (TSWV and INSV), this approach demonstrated that different viruses are processed distinctly, with TSWV showing much lower levels of small RNAs in co-infections compared to single infections [24].

Fluorescence-based tracking using GFP-tagged proteins enables real-time monitoring of silencing movement. In optimized TRV-VIGS systems, fluorescence signals appear in 2-3 cell layers initially before spreading deeper, with transverse sections showing over 80% of cells exhibiting successful infiltration [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Studying Systemic Silencing

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Applications | Research Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| DCL Mutants | Genetic disruption of vsiRNA biogenesis [3] | Pathway requirement tests | Establishing necessity of specific DCLs |

| AGO Proteins | RISC component analysis [3] | Immunoprecipitation studies | Identifying RNA targets and mobility |

| RDR6/SGS3 Complex | Secondary vsiRNA amplification [3] | Mutant complementation | Signal amplification mechanisms |

| Viral Movement Proteins | PD gating manipulation [19] | Trans-complementation assays | Studying intercellular transport |

| TRV VIGS Vectors | Systemic gene silencing [21] | Functional genomics | High-throughput gene validation |

| HTS Platforms | vsiRNA profiling and mapping [22] | Metagenomic studies | Comprehensive signal tracking |

Implications for Virus-Resistant Plant Validation

Understanding systemic silencing movement has profound implications for developing and validating virus-resistant crops. The efficiency of signal propagation directly correlates with the durability and breadth of resistance. Several emerging technologies leverage this knowledge:

Engineered dsRNA approaches represent a promising application, where externally applied dsRNAs are processed into siRNAs that trigger systemic silencing. Researchers have developed "efficient double-stranded RNA molecules (edsRNAs)" that function as packages broken down into multiple highly effective siRNA molecules after entering plant cells [23]. In laboratory tests against Cucumber mosaic virus, this approach achieved 80-100% plant survival even under high viral load conditions where all untreated plants died [23].

CRISPR-based resistance strategies are increasingly designed to consider signal mobility, with systems engineered to produce mobile silencing signals that can protect meristems and reproductive tissues - critical sites for preventing viral transmission to progeny [25]. This is particularly important for addressing the challenge of vertical transmission, where viruses can remain dormant in seeds for years [26].

The movement of silencing signals represents a fundamental aspect of plant immunity that continues to inform the development of virus-resistant crops. As researchers refine their understanding of the molecular players and transport mechanisms, new opportunities emerge for enhancing the efficiency and durability of resistance through optimized systemic silencing.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing VIGS and Advanced Editing Tools

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) has emerged as a potent and flexible tool for functional genomics, enabling rapid characterization of gene functions in plants. This powerful technique operates by exploiting the plant's innate post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) machinery, an antiviral defense mechanism that degrades viral RNA in a sequence-specific manner. When a recombinant viral vector carrying a fragment of a host gene is introduced into a plant, the system processes this into small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) that guide the degradation of complementary endogenous mRNA, leading to knockdown of target gene expression and observable phenotypic changes [27].

The foundational work establishing VIGS was conducted in 1995, when researchers used a Tobacco mosaic virus vector carrying a phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene fragment to induce photo-bleaching phenotypes in Nicotiana benthamiana [27]. Since this pioneering study, the VIGS toolkit has expanded dramatically, with vectors developed from numerous viruses including Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV), Bean Pod Mottle Virus (BPMV), and Cotton Leaf Crumple Virus (CLCrV) [27] [21]. The technology has now been successfully applied in over 50 plant species, spanning model organisms like Arabidopsis thaliana to economically important crops such as soybean, tomato, barley, and cotton [27].

For species where stable genetic transformation remains challenging—including many crops and perennial woody plants—VIGS offers a particularly valuable alternative. It provides a transient silencing approach that bypasses the need for stable transformation, significantly accelerating the pace of gene functional characterization from months to weeks [21] [28]. This advantage is especially pronounced in plants with complex genomes, extensive gene families, or low transformation efficiency, such as pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) and tea oil camellia (Camellia drupifera), where VIGS often represents the only viable tool for high-throughput functional screening [27] [28].

Molecular Mechanism of VIGS

The efficacy of VIGS stems from its exploitation of the plant's natural RNA interference (RNAi) pathway. The process initiates when a recombinant viral vector, engineered to carry a fragment (typically 200-500 base pairs) of a plant gene of interest, is introduced into plant tissues. Once inside the cell, the viral RNA replicates, generating double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) intermediates, which are the primary triggers of the silencing cascade [27].

These dsRNA molecules are recognized and processed by the plant's Dicer-like (DCL) enzymes, which cleave them into 21-24 nucleotide small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). These siRNAs are then incorporated into a multi-component RNA-Induced Silencing Complex (RISC), which uses the siRNA as a guide to identify and catalyze the sequence-specific cleavage of complementary endogenous mRNA transcripts. The resulting degradation of target mRNA leads to reduced protein production and the emergence of observable phenotypes that facilitate gene function characterization [27].

A critical feature of VIGS is its systemic nature—the silencing signal spreads from the initial site of infection throughout the plant via the vascular system, enabling whole-plant studies of gene function. This systemic movement is facilitated by viral movement proteins and involves the trafficking of siRNAs between cells through plasmodesmata [27] [29]. The entire VIGS process, from viral vector inoculation to phenotypic manifestation, typically occurs within 2-4 weeks, making it significantly faster than traditional stable transformation approaches [27].

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular steps in the VIGS mechanism:

Comparative Analysis of VIGS Systems Across Plant Species

VIGS Vector Systems and Their Applications

Various viral vectors have been developed and optimized for VIGS applications in different plant families. These vectors differ in their host range, silencing efficiency, symptom severity, and persistence. The selection of an appropriate vector system is critical for successful gene silencing and depends on the target plant species, tissue type, and experimental objectives [27].

RNA virus-based vectors, particularly those derived from Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV), are among the most widely used systems, especially for Solanaceae plants. TRV vectors feature a bipartite genome organization requiring two plasmid constructs: TRV1, which encodes replicase and movement proteins, and TRV2, which contains the coat protein gene and a multiple cloning site for inserting target sequences [27]. TRV-based systems offer several advantages, including broad host range, efficient systemic movement, ability to target meristematic tissues, and mild viral symptoms that minimize interference with phenotypic analysis [27] [21].

For legumes such as soybean, Bean Pod Mottle Virus (BPMV)-based systems have been extensively utilized due to their high efficiency and reliability. However, BPMV-VIGS often relies on particle bombardment for delivery, which can cause leaf damage that complicates phenotypic evaluation [21]. Recently, TRV-based systems have been successfully adapted for soybean using Agrobacterium-mediated infection through cotyledon nodes, achieving silencing efficiencies ranging from 65% to 95% [21].

Other notable VIGS systems include DNA virus-based vectors such as those derived from geminiviruses (e.g., Cotton Leaf Crumple Virus, CLCrV) and satellite virus-based systems [27]. Each system presents unique advantages and limitations, making them suitable for specific applications and plant species.

Performance Comparison Across Plant Species

The table below summarizes the efficiency and key parameters of VIGS systems across diverse plant species, highlighting the adaptability of this technology to various biological contexts:

Table 1: Comparative Efficiency of VIGS Systems Across Plant Species

| Plant Species | Viral Vector | Delivery Method | Target Gene | Silencing Efficiency | Key Factors for Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soybean (Glycine max) [21] | TRV | Cotyledon node immersion | GmPDS, GmRpp6907, GmRPT4 | 65-95% | Agrobacterium strain, explant type, immersion duration (20-30 min optimal) |

| Tea oil camellia (Camellia drupifera) [28] | TRV | Pericarp cutting immersion | CdCRY1, CdLAC15 | ~69.80% (CdCRY1), ~90.91% (CdLAC15) | Capsule developmental stage, infiltration approach |

| Sunflower (Helianthus annuus) [29] | TRV | Seed vacuum infiltration | HaPDS | Up to 91% (genotype-dependent) | Genotype, vacuum and co-cultivation duration (6h optimal) |

| Taro (Colocasia esculenta) [30] | TRV | Leaf injection, bulb vacuum | CePDS, CeTCP14 | 12.23-27.77% | Bacterial concentration (OD600=1.0 optimal) |

| Blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) [31] | Not specified | Fruit tissue infiltration | VcBAHD-AT1, VcBAHD-AT4 | Effective (abolished acylated anthocyanins) | Tissue-specific optimization, fruit developmental stage |

| Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) [27] | TRV, BBWV2, CMV | Agroinfiltration | Multiple genes for fruit quality, stress resistance | Variable (genotype-dependent) | Plant developmental stage, temperature, light conditions |

Factors Influencing VIGS Efficiency Across Species

The effectiveness of VIGS is governed by multiple interconnected factors that researchers must optimize for each plant system. Plant genotype significantly influences susceptibility to viral infection and subsequent silencing efficiency, as demonstrated in sunflower where infection rates varied from 62% to 91% across different genotypes [29]. Similarly, in pepper, genetic background substantially impacts transformation and silencing efficiency [27].

Developmental stage at inoculation represents another critical determinant. Research in Camellia drupifera revealed that optimal silencing of CdCRY1 and CdLAC15 occurred at early and mid stages of capsule development, respectively [28]. Younger tissues generally exhibit more active spreading of silencing signals compared to mature tissues, as observed in sunflower [29].

Environmental conditions, particularly temperature, profoundly affect VIGS efficiency. Most systems operate optimally within the range of 19-22°C, as higher temperatures can accelerate viral replication but may also enhance plant defense responses that limit silencing spread [27]. Additional factors including light intensity, photoperiod, and humidity further modulate silencing efficacy and must be standardized for reproducible results [27] [29].

The design of the insert fragment is equally crucial for successful silencing. Effective inserts typically range from 200-500 base pairs, with careful bioinformatic analysis essential to ensure specificity and minimize off-target effects. Tools such as the SGN VIGS Tool facilitate the selection of appropriate target sequences [28]. Furthermore, agroinoculum concentration (OD600) significantly impacts silencing efficiency, as demonstrated in taro where increasing OD600 from 0.6 to 1.0 more than doubled the silencing rate from 12.23% to 27.77% [30].

Essential Research Reagents and Experimental Protocols

Research Reagent Solutions for VIGS

Successful implementation of VIGS requires specific biological materials and reagents carefully selected for compatibility with the target plant system. The following table outlines core components of the VIGS toolkit:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for VIGS Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Vectors [27] [21] | pTRV1, pTRV2, BPMV, CLCrV | Delivery of target gene fragments to plant cells; TRV-based systems most common for broad host range |

| Agrobacterium Strains [21] [28] | GV3101, LBA4404 | Mediate transfer of viral vectors into plant tissues; GV3101 widely used for efficacy with Solanaceae |

| Selection Antibiotics [28] [29] | Kanamycin, Rifampicin, Gentamicin | Maintain plasmid integrity in bacterial cultures and select for transformed Agrobacterium |

| Induction Compounds [28] | Acetosyringone, MES buffer | Enhance Agrobacterium virulence gene expression and stabilize pH for improved transformation efficiency |

| Plant Selection Markers [21] | GFP, GUS | Visual assessment of infection efficiency and silencing spread through fluorescent or colorimetric detection |

| Target Gene Constructs [28] | PDS, TCP14, WRKY, Rpp6907 | Endogenous genes targeted for silencing; marker genes like PDS provide visual silencing confirmation |

Standardized VIGS Experimental Protocol

The following workflow details a generalized TRV-based VIGS protocol adaptable to various plant species, with specific modifications recommended for different biological systems:

Step 1: Vector Construction and Preparation

- Clone a 200-500 base pair fragment of the target gene into the multiple cloning site of the TRV2 vector using appropriate restriction enzymes or recombination cloning [21] [28].

- Verify insert sequence and orientation through colony PCR and Sanger sequencing.

- Simultaneously maintain the TRV1 vector, which provides essential replication and movement proteins.

Step 2: Agrobacterium Transformation and Culture

- Introduce recombinant TRV1 and TRV2 plasmids into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 using electroporation or freeze-thaw methods [29].

- Plate transformed cells on LB agar containing appropriate antibiotics (e.g., 50 μg/mL kanamycin, 50 μg/mL rifampicin) and incubate at 28°C for 2 days [28] [29].

- Inoculate single colonies into liquid YEB or LB medium with antibiotics and induction supplements (10 mM MES, 20 μM acetosyringone) and culture overnight at 28°C with shaking (200-240 rpm) until OD600 reaches 0.9-1.0 [28].

Step 3: Agroinoculum Preparation and Plant Inoculation

- Harvest bacterial cells by centrifugation (5000 rpm for 15 minutes) and resuspend in infiltration medium (10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES, 200 μM acetosyringone) to the desired OD600 (typically 0.6-1.0) [28] [30].

- Mix TRV1 and TRV2 cultures in 1:1 ratio and incubate at room temperature for 3-4 hours before inoculation.

- Apply the agroinoculum using methods appropriate for the target species:

- Leaf infiltration: Use needleless syringe to infiltrate suspension into abaxial leaf surface [29].

- Vacuum infiltration: Submerge plant tissues (seeds, seedlings, or explants) in bacterial suspension and apply vacuum (25-28 in Hg) for 2-5 minutes [29].

- Cotyledon node immersion: Bisect swollen seeds and immerse explants in bacterial suspension for 20-30 minutes [21].

- Pericarp cutting immersion: For fruits, create incisions in the pericarp and immerse in bacterial suspension [28].

Step 4: Post-Inoculation Incubation and Analysis

- Maintain inoculated plants under controlled environmental conditions (19-22°C, 16-18h light/6-8h dark photoperiod, 45-60% humidity) for 2-4 weeks to allow systemic silencing establishment [27] [29].

- Monitor for visual silencing phenotypes (e.g., photo-bleaching for PDS silencing) beginning at 10-21 days post-inoculation.

- Quantify silencing efficiency through qRT-PCR analysis of target gene expression, comparing VIGS-treated plants to empty vector controls [21] [28].

- Document phenotypic alterations through photography and conduct additional biochemical or physiological assays as required by experimental objectives.

Applications in Plant Functional Genomics and Biotechnology

Functional Characterization of Agronomically Important Genes

VIGS has dramatically accelerated the functional characterization of genes controlling economically valuable traits in crop species. In pepper (Capsicum annuum L.), VIGS has enabled the identification of genes governing fruit quality attributes including color, biochemical composition, and pungency [27]. The technology has similarly elucidated genes regulating plant architecture, development, and metabolic pathways unique to this species [27].

For disease resistance breeding, VIGS provides a rapid means to validate candidate resistance genes before undertaking lengthy stable transformation programs. In soybean, TRV-based VIGS successfully silenced the rust resistance gene GmRpp6907 and the defense-related gene GmRPT4, confirming their roles in pathogen defense [21]. Similarly, in pepper, VIGS has identified genes conferring resistance to bacterial pathogens, oomycetes, and insects [27].

The application of VIGS extends to abiotic stress tolerance, with studies in pepper using the technology to identify genes involved in responses to temperature extremes, salt stress, and osmotic stress [27]. This capability to rapidly connect genes to stress adaptation phenotypes makes VIGS particularly valuable for climate-resilient crop development.

Elucidation of Metabolic Pathways

VIGS has proven instrumental in deciphering biosynthetic pathways of specialized metabolites in plants. A notable application involves the identification of two BAHD-family acyltransferase genes (VcBAHD-AT1 and VcBAHD-AT4) that regulate anthocyanin acylation in blueberries [31]. Using an optimized VIGS system in fruit tissues, researchers demonstrated that silencing either gene completely abolished production of acylated anthocyanins without affecting total anthocyanin levels, confirming their specific role in pigment modification [31].

Similar approaches have been employed to investigate starch biosynthesis in taro, where silencing of CeTCP14 using a TRV-based VIGS system significantly reduced starch accumulation in corms to 70.88%-80.61% of control levels [30]. These findings not only clarified gene function but also identified potential targets for molecular breeding programs aimed at modifying starch content.

Validation of Gene Function in Recalcitrant Species

For plant species with long life cycles or recalcitrance to stable transformation, VIGS offers unprecedented opportunities for functional genomics. In perennial woody species like Camellia drupifera, where stable transformation remains challenging, researchers developed an efficient VIGS system for capsules using pericarp cutting immersion [28]. This system achieved impressive silencing efficiencies of approximately 69.80% for CdCRY1 and 90.91% for CdLAC15, enabling functional analysis of genes involved in pericarp pigmentation [28].

Similar advances have been reported for sunflower, where a seed vacuum infiltration protocol facilitated extensive viral spreading throughout infected plants, with TRV detected in leaves up to node 9 [29]. These developments highlight how VIGS methodology can be adapted to overcome species-specific barriers, opening new possibilities for functional genomics in previously intractable plants.

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Technical Limitations and Optimization Strategies

Despite its considerable advantages, VIGS faces several technical challenges that require careful consideration. Genotype-dependent efficiency remains a significant constraint, as evidenced in sunflower where infection rates varied from 62% to 91% across different genotypes [29]. This variability necessitates optimization for each new genotype, potentially increasing experimental timelines.

Transient nature of silencing represents another limitation, as VIGS typically does not generate heritable mutations. While some studies report silencing persistence for more than two years in Nicotiana benthamiana and transmission to progeny seedlings, most applications provide temporary knockdown rather than permanent knockout [27]. This characteristic makes VIGS less suitable for studying genes involved in late developmental stages or traits requiring multi-generational analysis.

Potential off-target effects present additional concerns, particularly when silencing gene family members with high sequence similarity. Computational tools for careful insert design and empirical validation through multiple independent fragments can help mitigate this risk [28] [29]. Furthermore, viral symptom development may sometimes interfere with phenotypic interpretation, though vectors like TRV that induce mild symptoms are preferred to minimize this issue [27] [21].

Future methodological improvements will likely focus on expanding host ranges, enhancing silencing efficiency in recalcitrant tissues, and developing inducible or tissue-specific systems for precise spatiotemporal control of gene silencing. The integration of CRISPR-based technologies with VIGS may also enable more sophisticated functional genomics approaches, combining rapid screening with targeted genome editing [27].

Integration with Multi-Omics Technologies

The future trajectory of VIGS points toward increased integration with multi-omics platforms for comprehensive functional genomics. VIGS serves as a crucial validation tool within the functional genomics pipeline, connecting genomic sequences to phenotypic outcomes [27]. When combined with genome-wide association studies (GWAS), transcriptomics, metabolomics, and proteomics, VIGS enables researchers to move beyond correlation to causation in gene function analysis [31].

This integrated approach was exemplified in blueberry, where GWAS identified loci associated with anthocyanin acylation, and VIGS subsequently validated the functional roles of candidate BAHD acyltransferase genes [31]. Similar strategies are being employed to accelerate the identification of genes controlling complex traits in crop species, potentially shortening breeding cycles and enhancing precision in marker-assisted selection.

As sequencing technologies continue to advance, generating ever-expanding genomic resources for non-model species, VIGS will play an increasingly vital role in bridging the gap between sequence information and biological function. The development of more efficient, high-throughput VIGS platforms will further solidify this technology's position as an indispensable component of the plant functional genomics toolkit.

The validation of gene function is a critical step in the development of virus-resistant plants. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of cotyledon nodes has emerged as a highly efficient and versatile technique for introducing genetic material into plants, enabling rapid assessment of gene silencing efficiency. Unlike traditional transformation methods that often face challenges with regeneration recalcitrance and genotype dependency, the cotyledon node system leverages the high regenerative capacity of meristematic cells located at the junction of the cotyledon and embryonic axis. This method has proven particularly valuable for functional genomics studies in numerous plant species, including legumes, woody plants, and medicinal species that were previously considered transformation-recalcitrant. The protocols optimized in recent research demonstrate how cotyledon node transformation bypasses many limitations of conventional systems, offering researchers a powerful tool for accelerating crop improvement programs focused on enhancing disease resistance. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of cotyledon node transformation performance across species and details the experimental protocols supporting its application in virus resistance research.

Performance Comparison: Cotyledon Node Transformation Across Species

Table 1: Transformation Efficiency Comparison Across Plant Species and Explant Types

| Plant Species | Explant Type | Transformation Efficiency Key Findings | Key Optimized Parameters | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soybean | Cotyledon Node | 65-95% VIGS efficiency; >80% cell infiltration | Agrobacterium GV3101, 20-30 min immersion | [21] |

| Eureka Lemon | Whole Cotyledonary Node | 14.48% stable transformation; 42.26% regeneration | Solid co-cultivation medium, reduced tissue browning | [32] |

| Sunflower | Cotyledon (transient) | >90% transient transformation | OD600 0.8, 0.02% Silwet L-77, 2h infiltration | [33] |

| Cannabis sativa | Cotyledonary Node | ~70-90% de novo regeneration; genotype-independent | TDZ and NAA containing medium | [34] |

| Nepeta cataria | Cotyledon (VIGS) | 84.4% VIGS efficiency within 3 weeks | TRV vector, Agrobacterium-mediated infiltration | [35] |

| Sugarbeet | Hypocotyl-derived callus | 36% shoot regeneration; 50% molecularly positive | 0.4 OD Agrobacterium, 2-day co-cultivation, dark incubation | [36] |

| Arabidopsis | Suspension cells | ~100% infection rate with optimized protocol | AGL1 strain, solidified medium, Pluronic F68 | [37] |

Table 2: Key Advantages and Limitations of Cotyledon Node Transformation

| Aspect | Cotyledon Node Transformation | Conventional Explant Transformation |

|---|---|---|

| Regeneration Efficiency | High regeneration (42-90%) from pre-existing meristematic cells [32] [34] | Variable, often lower efficiency; highly genotype-dependent |

| Transformation Time | Rapid: VIGS effects in 3 weeks; transient expression within days [21] [35] | Typically longer: often requires multiple months for stable lines |

| Genotype Dependency | Low to moderate: demonstrated across diverse genotypes [34] | Often high: limited to specific amenable genotypes |

| Technical Complexity | Moderate: requires careful explant preparation but minimal tissue culture | High: often requires extensive tissue culture expertise |

| Application Range | Broad: stable transformation, VIGS, transient expression [21] [32] [35] | Typically focused on stable transformation only |

| Browning/Recalcitrance | Minimal browning due to limited exposure to medium [32] | Significant challenge in species like lemon and garlic |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Soybean Cotyledon Node VIGS Protocol

The tobacco rattle virus (TRV)-based virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) system in soybean represents one of the most efficient applications of cotyledon node transformation for gene function validation [21]. The optimized protocol achieves 65-95% silencing efficiency through the following detailed methodology:

Vector Construction: Target gene fragments (200-400 bp) are amplified from soybean cDNA using gene-specific primers with engineered restriction sites (EcoRI and XhoI). The fragments are cloned into the pTRV2-GFP vector, and the resulting recombinant plasmids are transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 [21].

Explant Preparation and Agroinfiltration: Sterilized soybean seeds are soaked in sterile water until swollen, then longitudinally bisected to obtain half-seed explants containing the cotyledon node. Fresh explants are immersed for 20-30 minutes in Agrobacterium suspension (OD600 = 0.8) containing pTRV1 and pTRV2-derivative vectors. This immersion method overcomes the limitations of conventional misting and injection, which show low efficiency due to soybean leaves' thick cuticle and dense trichomes [21].

Evaluation of Infection Efficiency: By the fourth day post-infection, fluorescence microscopy reveals successful infection in over 80% of cells in transverse sections, with initial infiltration penetrating 2-3 cell layers before spreading to deeper cells. This high infection rate translates to effective systemic silencing of endogenous genes throughout the plant [21].

Eureka Lemon Whole Cotyledonary Node Transformation

The transformation protocol for Eureka lemon addresses the severe constraints of conventional epicotyl transformation, which suffers from extreme tissue browning and low efficiency [32]. The whole cotyledonary node system achieves 14.48% transformation efficiency through the following optimized steps:

Explant Excellence: Whole cotyledonary nodes are excised from sterilized seeds and used as explants. Their structural simplicity reduces preparation time and labor compared to traditional epicotyl systems. Critically, most tissue remains outside the medium during co-cultivation, minimizing oxidative browning caused by accumulation of phenolic compounds and cytotoxic quinones [32].

Co-cultivation and Regeneration: Explants are inoculated with Agrobacterium strain GV3101 carrying the pNmGFPer plasmid with eGFP reporter gene. After co-cultivation, the explants are transferred to regeneration medium where calli form at wound sites within 10 days, developing vigorous fascicular shoots by day 15. The regeneration rate of 42.26% for whole cotyledonary nodes is approximately eight times higher than that of epicotyl explants [32].

Confirmation of Stable Transformation: GFP fluorescence is observed in all tissues of regenerated shoots under ultraviolet light, with PCR analysis confirming stable integration of the gfp gene into the Eureka lemon genome. Grafted transgenic plantlets maintain consistent transgene expression [32].

Sunflower Cotyledon Transient Transformation

The optimized transient transformation system for sunflower achieves over 90% efficiency using cotyledon infiltration, providing a rapid platform for gene function validation [33]. The protocol involves:

Infiltration Optimization: Hydroponically grown 3-day-old seedlings are immersed in Agrobacterium GV3101 suspension (OD600 = 0.8) carrying the pBI121 vector with GUS reporter gene. The solution contains 0.02% Silwet L-77 as surfactant, proven superior to Triton X-100 with 44.4% higher GUS gene expression. Optimal immersion time is 2 hours, as longer durations (4-8 hours) cause tissue damage and root necrosis [33].

Alternative Delivery Methods: The study also optimized injection and ultrasonic-vacuum methods. For injection, soil-grown 4-6-day-old seedlings receive Agrobacterium suspension directly into cotyledons, followed by 3 days of dark cultivation. The ultrasonic-vacuum method subjects Petri-dish-cultured 3-day-old seedlings to ultrasonication at 40 kHz for 1 minute followed by vacuum infiltration at 0.05 kPa for 5-10 minutes [33].

Application for Stress Tolerance Genes: The established system successfully validated the salt and drought tolerance function of HaNAC76, a sunflower NAC transcription factor gene, demonstrating the practical application for stress resistance research [33].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Agrobacterium-Mediated Gene Transfer and Plant Regeneration

Figure 1: Comprehensive Workflow for Cotyledon Node Transformation

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) Mechanism

Figure 2: VIGS Mechanism for Gene Function Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cotyledon Node Transformation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes | Optimal Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium Strains | AGL1, GV3101 | AGL1: hypervirulent, high efficiency; GV3101: widely adapted, good for VIGS | OD600 0.4-0.8 for infection |

| Vector Systems | TRV-VIGS, pTRV2-GFP, pNmGFPer | TRV: effective systemic silencing; GFP: visual tracking of transformation | - |

| Surfactants | Silwet L-77, Pluronic F68 | Enhance tissue penetration; reduce surface tension | 0.02-0.05% |

| Induction Compounds | Acetosyringone | Activates Agrobacterium vir genes; enhances T-DNA transfer | 100-200 μM |

| Plant Growth Regulators | TDZ, NAA, BAP, Kinetin | Stimulate de novo shoot regeneration from cotyledon nodes | Species-dependent |

| Antibiotics | Carbenicillin, Kanamycin, Ticarcillin | Select transformed tissues; eliminate Agrobacterium post-co-culture | 50-250 μg/mL |

| Visual Markers | GFP, GUS, RUBY | Non-destructive monitoring of transformation efficiency | - |

| Antioxidants | MES, L-cysteine, DTT | Reduce tissue browning; improve regeneration in recalcitrant species | Varying concentrations |

Agrobacterium-mediated cotyledon node transformation represents a significant advancement in plant genetic engineering, particularly for validating gene silencing efficiency in virus resistance research. The comparative data presented demonstrates its superior performance across multiple plant species, with transformation efficiencies reaching 14.48% in stable transformation and 65-95% in VIGS applications. The method's robustness stems from the high regenerative capacity of cotyledon node cells, reduced tissue browning compared to conventional explants, and applicability across diverse species including previously recalcitrant plants. As plant biotechnology continues to focus on developing virus-resistant cultivars, the cotyledon node transformation system provides researchers with a reliable, efficient tool for rapid gene function validation. The optimized protocols detailed in this guide serve as an essential resource for scientists pursuing crop improvement through genetic approaches.