Systematic Protein Localization in Plants: From Computational Prediction to Experimental Validation

This comprehensive review examines the integrated ecosystem of methods for determining protein subcellular localization in plant systems.

Systematic Protein Localization in Plants: From Computational Prediction to Experimental Validation

Abstract

This comprehensive review examines the integrated ecosystem of methods for determining protein subcellular localization in plant systems. Covering both computational prediction tools and experimental validation techniques, we provide researchers with a systematic framework for selecting appropriate methodologies based on their specific research needs. The article explores foundational concepts in protein targeting, details established protocols including fluorescent protein fusions and immunolocalization, addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, and presents rigorous validation approaches. With special emphasis on plant-specific challenges and recent advancements in machine learning prediction tools, this resource serves as an essential guide for plant biologists, pathologists, and researchers in agricultural biotechnology and drug development working with plant systems.

Protein Targeting Fundamentals: Understanding Cellular Addressing in Plants

The Biological Significance of Protein Localization in Plant Physiology

Protein localization is a fundamental determinant of protein function in plant cells. The precise subcellular compartment where a protein resides directly governs its interactions, stability, and biological activity. Understanding protein localization is therefore essential for elucidating diverse physiological processes in plants, from growth and development to stress responses and pathogen interactions [1]. This technical support center provides plant researchers with practical guidance for designing, executing, and troubleshooting protein localization experiments, supporting systematic approaches for defining complete plant proteomes through visualization.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Encountering challenges in your protein localization experiments? This troubleshooting guide addresses frequent problems and provides practical solutions to ensure reliable results.

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions | Prevention Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| High background/autofluorescence | Chlorophyll, cell wall compounds, or phenolic metabolites [2]; Fixation artifacts | Use spectral unmixing; Try alternative fluorophores with longer wavelengths (e.g., RFP, TagBFP) [1]; Optimize fixation protocols or use live-cell imaging | Characterize autofluorescence in untransformed tissue first; Choose fluorophores outside plant autofluorescence spectra |

| Aberrant or unexpected localization | Protein overexpression artifacts; Tag interfering with function or targeting; Non-physiological conditions | Express protein at native levels using endogenous promoters; Try N- vs. C-terminal tags; Validate with full biological replicates under correct conditions [1] | Conduct in silico analysis first (e.g., LOCALIZER [3]); Test multiple tag configurations |

| No fluorescence signal | Poor protein expression; Fluorophore folding/maturation issues; Tag cleaved | Confirm construct sequence fidelity; Use commercially available antibodies against AFP tags for validation [1]; Test FP functionality with known markers | Include a positive control (e.g., free FP targeted to same compartment); Verify fusion protein size via immunoblot |

| Cross-talk in multi-channel imaging | Bleed-through from fluorophore emission spectra overlap [1] | Image each fluorophore separately and test individually; Use sequential scanning with narrow detection bandwidths [1] | Choose fluorophore pairs with minimal spectral overlap (e.g., CFP/YFP, GFP/RFP) [1] |

| Claimed colocalization is not specific | Punctate signal overlaying diffuse signal misinterpreted as positive [1] | Use quantitative colocalization coefficients (e.g., Pearson's correlation); Employ subcellular markers as positive controls [1] | Always include a known marker for the compartment; Perform statistical analysis on multiple cells |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My protein is predicted to localize to the nucleus, but my experimental results show a different pattern. Which result should I trust? Trust your experimental results, but with verification. Computational predictions like LOCALIZER identify potential targeting signals (e.g., NLS) but cannot account for all regulatory mechanisms [3]. Confirm your result by: 1) Using a validated nuclear marker as a positive control [1], 2) Ensuring your experimental conditions (e.g., cell type, stress) are physiologically relevant, and 3) Testing for potential protein-protein interactions that could alter localization.

Q2: How can I distinguish between true protein interaction and simple colocalization? Colocalization indicates proteins reside in the same subcellular compartment, but does not prove direct interaction [1]. To demonstrate interaction, employ complementary techniques such as Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC), which can provide both interaction and localization data [1], or Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET). A true interaction should be validated by multiple independent methods.

Q3: What are the best practices for image processing and presentation to avoid misinterpretation? Always maintain scientific integrity. Apply brightness/contrast adjustments linearly across the entire image. Never obscure data through selective editing. The final published micrograph must accurately represent the original observed localization pattern [1]. Clearly document all manipulations in your methods section.

Q4: How do I handle proteins that may localize to multiple compartments? Dual localization is a common biological phenomenon. Use LOCALIZER in "Plant mode" as it is specifically designed to predict dual targeting to compartments like chloroplasts and mitochondria [3]. Experimentally, perform colocalization studies with markers for each suspected compartment across multiple biological replicates and physiological conditions.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Core Methodologies for Protein Localization

Protocol 1: Transient Expression for Protein Localization via Agroinfiltration [1] This method allows for rapid assessment of protein localization in plant leaves.

- Vector Construction: Clone your gene of interest into an appropriate expression vector (e.g., pGD, pSITE series) to create an N- or C-terminal fusion with an Autofluorescent Protein (AFP) like GFP or RFP.

- Agrobacterium Transformation: Transform a suitable Agrobacterium strain (e.g., LBA4404, C58C1) with your constructed vector.

- Culture Preparation:

- Inoculate transformed colonies onto LB agar with appropriate antibiotics. Incubate at 28°C for 1-several days.

- Harvest bacteria and resuspend in agroinfiltration buffer (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl₂, 150 μM acetosyringone, pH 5.9).

- Adjust the suspension to an optimal optical density (OD₆₀₀ typically between 0.2 and 0.5).

- Incubate the suspension at room temperature for 30 minutes to 4 hours.

- Infiltration: Using a syringe without a needle, press the syringe tip against the abaxial (lower) side of a leaf from a suitable host plant (e.g., Nicotiana benthamiana) and gently infiltrate the bacterial suspension.

- Incubation: Grow the infiltrated plants for 2-3 days to allow for protein expression.

- Imaging: Analyze the epidermal cell layer of the infiltrated leaf area using confocal microscopy.

Protocol 2: Live-Cell Immunofluorescence Labeling of Root Hairs [4] This protocol allows for dynamic visualization of cell wall components in living root hairs without fixation.

- Seedling Growth: Grow Arabidopsis seedlings on vertical agar plates under standard conditions.

- Antibody Labeling:

- Place seedlings in a multi-well dish containing a solution of the monoclonal antibody (e.g., LM15 for xyloglucan) diluted in a suitable buffer (e.g., PBS or MS medium).

- Incubate for 60-90 minutes. A low concentration of detergent (e.g., 0.85 mM Triton-X100) can be included, but is not always necessary.

- Washing: Gently rinse the seedlings with buffer to remove unbound antibody.

- Mounting: Mount the seedlings in the same buffer for observation.

- Imaging: Immediately image the live, labeled root hairs using Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM).

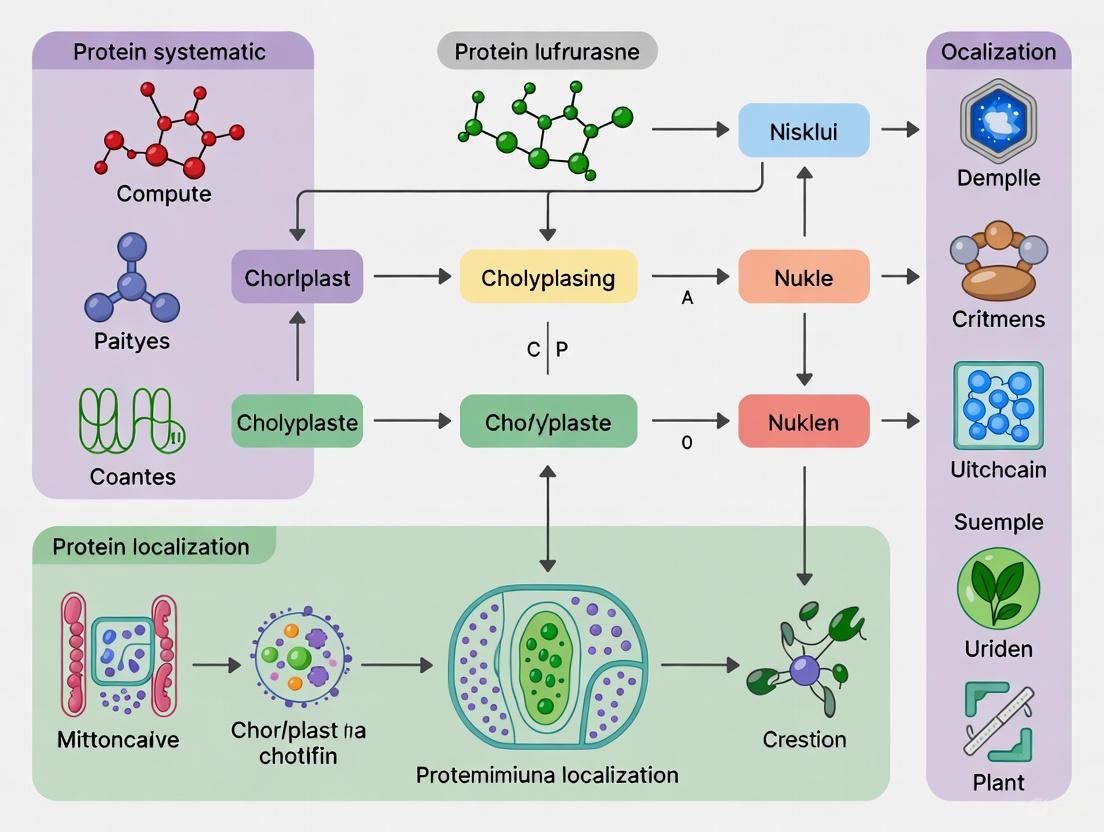

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The diagram below outlines a systematic workflow for determining protein localization, from initial planning to data reporting.

Membrane Trafficking and Cytoskeletal Relationships

This diagram illustrates the key cellular components involved in trafficking and organelle positioning, such as the role of actin in maintaining nuclear position in root hairs.

Data Presentation & Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of Localization Prediction Tools

Selecting the right computational tool is crucial for experimental design. The table below compares the performance of different prediction algorithms.

| Tool | Chloroplast Prediction (MCC/Accuracy) | Mitochondrial Prediction (MCC/Accuracy) | Nuclear Prediction (MCC/Accuracy) | Key Feature / Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOCALIZER | 0.71 / 91.4% [3] | 0.54 / 91.7% [3] | 0.40 / 73.0% [3] | Effector proteins; Dual localization prediction; Plant-specific |

| YLoc+ | Lower than LOCALIZER [3] | Lower than LOCALIZER [3] | Higher than LOCALIZER [3] | Homology-based; Good for nuclear proteins |

| WoLF PSORT | Lower than LOCALIZER [3] | Lower than LOCALIZER [3] | Higher than LOCALIZER [3] | Annotation-based; Good for nuclear proteins |

| TargetP | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | General protein targeting; Assumes transit peptide at N-terminus |

| ChloroP | Not reported | Not applicable | Not applicable | Chloroplast-specific; Assumes transit peptide at N-terminus |

MCC: Matthews Correlation Coefficient

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful localization experiments rely on high-quality reagents and tools. This table lists essential materials and their applications.

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Localization Studies | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Autofluorescent Protein (AFP) Fusions (e.g., GFP, RFP) | Visualize protein dynamics in live cells [1] | N- or C-terminal tagging of protein of interest for confocal microscopy. |

| Subcellular Marker Lines | Reference for specific organelles [1] | Transgenic plants expressing AFP targeted to nucleus, plasma membrane, Golgi, etc. |

| LOCALIZER Software | Predict localization of plant and effector proteins [3] | Prioritize experimental candidates; identify chloroplast transit peptides or NLS. |

| Monoclonal Antibodies (e.g., LM15, LM19) | Label specific cell wall polymers in live or fixed cells [4] | Live-cell immunofluorescence of root hairs to study cell wall dynamics. |

| FRAP (Fluorescence Recovery After Photobleaching) | Measure protein mobility and binding kinetics [7] [8] | Quantify dynamics of membrane-associated proteins [7]. |

| High-Throughput Sorters (e.g., BioSorter, COPAS) | Analyze and sort large samples like protoplasts or calli [9] | Gently sort transformed protoplasts based on fluorescent markers for downstream culture. |

Key Methodologies for Protein Localization

The systematic determination of protein localization is fundamental to understanding protein function in plant cells. The table below summarizes the primary experimental and computational approaches used for this purpose.

| Methodology | Key Features & Applications | Key Reagents/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy [10] [11] | High-resolution imaging for precise subcellular co-localization; creates 3D z-stacks; ideal for distinguishing membrane vs. intracellular protein localization. | Primary & secondary antibodies, fluorophores (e.g., for GFP, RFP), paraformaldehyde (fixative), mounting medium with DAPI/Hoechst (nuclear stain). |

| Computational Prediction [12] | Fast, reliable prediction of subcellular localization from protein sequence data; used for high-throughput screening and hypothesis generation. | Software tools and web servers utilizing machine learning algorithms (e.g., predictors for eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral proteins). |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy [13] | Verifies correct protein folding and secondary structure; used to validate recombinant proteins or check structural changes from mutations. | BeStSel web server for analyzing CD spectra; predicts eight secondary structure components and protein fold stability. |

Experimental Workflow: From Sample to Image

The following diagram outlines a standard workflow for determining protein localization via confocal microscopy, from sample preparation to image analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful protein localization experiments depend on high-quality, specific reagents. This table details essential materials and their functions.

| Research Reagent / Material | Critical Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies [11] | Bind specifically to the protein of interest (antigen). For multiple labeling, they must be derived from different species. |

| Fluorophore-conjugated Secondary Antibodies [11] | Bind to species-specific primary antibodies, providing a detectable fluorescent signal. Must be compatible with available laser wavelengths. |

| Paraformaldehyde [11] | A fixative agent that preserves cellular morphology by cross-linking proteins, maintaining structure during processing and imaging. |

| Blocking Agent (BSA, Milk, Serum) [11] | Reduces non-specific binding of antibodies to the sample, thereby minimizing background noise and improving signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Mounting Medium with Counterstain [11] | Preserves the sample, prevents photobleaching, and often contains a nuclear stain (e.g., DAPI) to identify and locate all cell nuclei. |

| BeStSel Web Server [13] | A computational tool that analyzes Circular Dichroism (CD) spectra to determine protein secondary structure and validate folding. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the single most important factor for a successful multi-color confocal imaging experiment?

Antibody specificity and spectral separation are paramount [11]. The primary antibodies must be raised in different host species, and the fluorophores on the secondary antibodies must have excitation/emission spectra that are distinct enough to be clearly discriminated by the microscope's filters and detectors, preventing cross-talk (spectral bleed-through) [10].

My protein localization results from transient expression of a tagged protein are ambiguous or unexpected. What could be wrong?

This is a common challenge. The tagging of proteins or their overexpression can potentially alter the intracellular localization or the function of the target protein [10]. The tag may interfere with targeting signals, or overexpression may overwhelm the cell's natural protein trafficking systems. Where possible, validate key findings with antibodies against the endogenous protein.

How can I quickly assess if my purified recombinant plant protein is correctly folded before a localization assay?

Circular Dichroism (CD) spectroscopy is a rapid and cost-effective technique for this purpose [13]. It provides a spectrum that serves as a "fingerprint" of the protein's secondary structure. You can use the BeStSel web server to analyze the CD data and verify if the protein's folding matches expectations [13].

My confocal images have a persistent, hazy background. How can I reduce this noise?

The hazy background is typically caused by out-of-focus fluorescence [11]. Ensure your confocal microscope's pinhole is correctly aligned and adjusted. The pinhole is designed to block light emitted from outside the focal plane, which is the primary source of this haze. Using thinner sample sections or optimizing your staining protocol to reduce non-specific antibody binding can also help.

Besides experimental methods, are there computational tools to predict where my protein of interest might be located?

Yes, protein subcellular localization prediction tools are a valuable resource [12]. These computational methods use protein sequence features to predict localization. They are particularly useful for prioritizing proteins for experimental work or for generating hypotheses when no other data is available. Note that these are predictions and require experimental validation.

In plant cell biology, understanding protein function requires precise knowledge of its subcellular location. Proteins are synthesized in the cytoplasm and contain specific targeting signals that direct them to their correct destinations. These signals include transit peptides for chloroplast localization, nuclear localization signals (NLS) for nuclear import, and various other sorting determinants for other organelles. For researchers systematically determining protein localization, recognizing these signals and understanding their mechanisms is fundamental. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and experimental protocols to address common challenges in identifying and validating these targeting signals within the context of plant protein localization studies.

Core Concepts: Defining the Key Targeting Signals

What are the primary types of nuclear localization signals (NLS)?

Nuclear localization signals are short peptide sequences that mediate the transport of proteins from the cytoplasm into the nucleus through the nuclear pore complex. The table below summarizes the key types and their characteristics [14].

Table 1: Types of Nuclear Localization Signals (NLS)

| NLS Type | Consensus Motif/Characteristics | Example Sequences | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Monopartite (MP) | 4-8 basic amino acids; K(K/R)X(K/R) [14] | SV40 T-antigen: PKKKRKV [14]; VACM-1/CUL5: PKLKRQ [14] |

Single cluster of basic residues (Arg, Lys) |

| Classical Bipartite (BP) | Two basic clusters separated by a 9-12 amino acid linker; R/K(X)~10-12~KRXK [14] | Nucleoplasmin: KRPAATKKAGQAKKKK [14]; 53BP1: GKRKLITSEEERSPAKRGRKS [14] |

Two clusters are interdependent |

| Non-classical PY-NLS | N-terminal hydrophobic/basic motif + C-terminal R/K/H(X)~2-5~PY motif [14] | hnRNP A1 (hPY-NLS): FGNYNNQSSNFGPMKGGNFGGRSSGPY [14]; Hrp1 (bPY-NLS): Contains HRR and R(X)~2-5~PY [14] |

Rich in proline and tyrosine; disordered structure |

What is a chloroplast transit peptide and how does it function?

Chloroplast transit peptides (TPs) are N-terminal extensions, typically 25-100 amino acids long, that act as a "postal address" for directing nucleus-encoded proteins to chloroplasts [15]. Unlike NLSs, TPs are cleaved off by the Stromal Processing Peptidase (SPP) after the protein is imported into the chloroplast [16]. Their primary sequences are highly heterogeneous, but they provide binding motifs for cytosolic chaperones and the translocon complexes [15]. The import process is mediated by the TOC (Translocon at the Outer Chloroplast membrane) and TIC (Translocon at the Inner Chloroplast membrane) complexes [15].

Table 2: Key Components of the Chloroplast Protein Import Machinery

| Complex/Component | Subunits / Examples | Function in Protein Import |

|---|---|---|

| TOC Complex | Toc159, Toc33, Toc75 [15] | Initial receptor at outer membrane; forms import channel |

| TIC Complex | Multiple subunits (e.g., Tic110) [15] | Translocon at the inner chloroplast membrane |

| Cytosolic Factors | Hsp90, Hsp70, AKR2, sHsp17.8 [15] | Maintain preproteins in import-competent state; target to TOC |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Troubleshooting Protein Localization Experiments

Table 3: Common Issues and Solutions in Protein Localization Studies

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpected Cytoplasmic Retention | NLS is masked or non-functional [14] | Verify NLS sequence integrity; check for protein folding or interaction issues that obscure the NLS. |

| Incorrect Chloroplast Import | Disrupted or inefficient Transit Peptide [16] [15] | Confirm TP sequence is intact and correctly fused upstream of the protein of interest. |

| Weak or No Fluorescent Signal | Low expression of fusion protein; protein instability [1] | Validate fusion protein expression by immunoblotting; try different fluorescent protein tags; optimize promoter strength. |

| Ambiguous Localization Pattern | Lack of specific organellar markers; bleed-through (cross-talk) between fluorescent channels [1] | Always co-express with known organelle markers; image fluorophores separately and use controls to eliminate cross-talk. |

| Artifactual Localization | Overexpression causing mislocalization [1] | Use native promoters or titrate expression levels; confirm findings with complementary methods (e.g., immunocytochemistry). |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My protein has a predicted NLS, but my experimental data shows it is also in the cytoplasm. Why? The continuous shuttling of many proteins between the nucleus and cytoplasm can lead to this observation. Unlike signals for other organelles, NLSs are not cleaved after import, allowing for multiple rounds of transport [17]. The steady-state distribution depends on the balance between nuclear import and export rates. Perform a heterokaryon shuttling assay or use inhibitors of nuclear export to confirm shuttling behavior.

Q2: Can a protein localize to more than one organelle? Yes, this phenomenon is known as dual-targeting. For example, the protein NUCLEAR CONTROL OF PEP ACTIVITY (NCP) in Arabidopsis can be targeted to both the nucleus and chloroplasts. This is often regulated by alternative transcription initiation, generating protein isoforms with different targeting signals [18]. Light conditions can influence this process, promoting the production of a long isoform (NCP-L) with a chloroplast transit peptide [18].

Q3: How reliable are computational predictions for targeting signals? Computational tools provide a valuable first pass for identifying potential targeting signals [12]. However, they are predictive and not definitive. The final experimental validation is crucial, as the context of the full protein, its interactions, and post-translational modifications can all influence the functionality of a predicted signal [1]. Tools like ProteinFormer, which uses biological images and a transformer architecture, show state-of-the-art performance but still require empirical confirmation [19].

Q4: What are the best practices for visualizing protein colocalization? True colocalization requires a pixel-for-pixel overlap of signals from two different markers [1]. Always:

- Image each fluorophore separately to avoid cross-talk.

- Use transgenic lines expressing well-characterized organellar markers as a reference.

- Employ statistical methods (e.g., Pearson's correlation coefficient) to quantify colocalization.

- Be cautious in interpretation; proximity does not necessarily prove interaction or identical localization [1].

Experimental Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol: Validating NLS Function via Agrobacterium-Mediated Transient Expression

This protocol is adapted from established methods for protein expression in plant cells [1].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain (e.g., LBA4404, C58C1): For delivering genetic material into plant cells.

- Expression vector (e.g., pGD, pSITE): Plasmid for expressing the protein of interest, typically as a fusion with a fluorescent protein like GFP.

- Agroinfiltration Buffer: 10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl₂, 150 µM acetosyringone, pH 5.9. Facilitates Agrobacterium infection.

Methodology:

- Clone your gene of interest, with and without the putative NLS, into an expression vector containing a fluorescent protein tag (e.g., GFP).

- Transform the constructs into a tractable Agrobacterium strain.

- Grow cultures overnight on selective LB agar plates at 28°C.

- Resuspend the bacteria in agroinfiltration buffer to an optical density at 600 nm (OD~600~) of ~0.5.

- Infiltrate the bacterial suspension into the leaves of a suitable plant (e.g., Nicotiana benthamiana) using a needleless syringe.

- Incubate plants for 2-3 days to allow for protein expression.

- Image the leaf epidermal cells using confocal microscopy. Compare the localization of the full-length protein versus the protein with a mutated/deleted NLS. The nuclear localization should be abolished or reduced upon NLS mutation.

- Include controls: Co-infiltrate with a known nuclear marker (e.g., RFP fused to a classic NLS) to confirm the identity of the nuclear compartment [1].

Protocol: Testing Chloroplast Transit Peptide Function

Research Reagent Solutions:

- TP:GFP Fusion Construct: Plasmid where the putative transit peptide is fused to GFP.

- Chloroplast Marker: A construct for labeling chloroplasts, such as RFP targeted to the chloroplast stroma.

Methodology:

- Fuse the putative transit peptide sequence in-frame to the N-terminus of GFP in an expression vector.

- Follow the transient expression protocol (Steps 2-6 above) to deliver the TP:GFP construct into plant leaves.

- Image the leaf tissue by confocal microscopy. A functional transit peptide will result in GFP fluorescence that overlaps with the chlorophyll autofluorescence (at ~650-680 nm) or a co-expressed stromal marker.

- Critical control: Express GFP alone (without a TP). This should result in fluorescence throughout the cytoplasm and nucleus, but not inside chloroplasts. This confirms that chloroplast import is specific to the fused TP.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Localization Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Protein Tags (e.g., GFP, RFP, YFP) | Tagging proteins for visualization in live cells [1] | Use different colors for co-localization (e.g., GFP/RFP). Test if the tag interferes with protein function or localization. |

| Organellar Markers | Reference points for identifying subcellular compartments [1] | Use transgenic lines or co-express markers for nucleus, chloroplast, ER, etc. (e.g., RFP with an NLS for the nucleus). |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | Efficient transient expression of constructs in plant cells [1] | Strains like LBA4404 are commonly used for infiltration into N. benthamiana leaves. |

| Computational Predictors | In silico identification of potential targeting signals [12] | Tools for predicting NLS, transit peptides, and other signals provide a starting point for experimental design. |

| Confocal Microscopy | High-resolution imaging of protein localization in tissues [1] | Allows for optical sectioning and collection of specific fluorescence emission wavelengths, reducing background noise. |

Visualization of Pathways and Workflows

Nuclear Protein Import Pathway

This diagram illustrates the classical nuclear import pathway. The NLS on the cargo protein is recognized by the importin α/β complex in the cytoplasm. This complex then docks at the Nuclear Pore Complex (NPC) and is translocated into the nucleus. Inside the nucleus, binding of RanGTP to importin β causes a conformational change that leads to the release of the cargo protein [14] [17].

Chloroplast Protein Import Pathway

This diagram shows the pathway for importing nucleus-encoded proteins into chloroplasts. Cytosolic chaperones help target the preprotein (with its transit peptide) to the TOC complex on the outer envelope. The preprotein is then transferred through the TOC and TIC complexes in an ATP-dependent process. Once in the stroma, the transit peptide is cleaved by the Stromal Processing Peptidase (SPP), resulting in the mature protein [15].

Experimental Workflow for Systematic Localization

This workflow outlines a systematic approach for determining protein localization. The process begins with in silico analysis of the protein sequence to predict potential targeting signals. Based on these predictions, constructs are designed for expression as fluorescent protein fusions. These constructs are then transiently expressed in plant tissues, and the localization is visualized using confocal microscopy. The final, critical step is validation, which includes colocalization with known organellar markers [1].

Computational Prediction as a First-Line Exploration Tool

Within the broader thesis on systematic protein localization determination in plants, computational prediction serves as an indispensable first-line exploration tool. These methods enable researchers to generate testable hypotheses about protein function and localization before investing in costly and time-consuming wet-lab experiments. The field has evolved from early pattern-matching algorithms to sophisticated deep learning models that can predict localization for virtually any protein, providing plant biologists with powerful resources to guide their experimental designs [20] [21]. This technical support center provides essential guidance for researchers navigating these computational tools, with content specifically framed for plant science applications where protein mislocalization can impact critical traits from stress resilience to metabolic engineering.

Computational Tool Selection Guide

Key Prediction Tools and Their Applications

Table: Comparison of Major Protein Subcellular Localization Prediction Tools

| Tool Name | Input Type | Key Features | Organism Coverage | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepLoc 2.0/2.1 [22] | Protein sequence | Predicts 10 subcellular localizations; multi-label capability; sorting signal prediction | Eukaryotes | For prokaryotes, use DeepLocPro; Sequence length restrictions apply (truncates sequences >4000 aa) |

| PUPS [23] | Protein sequence + 3 cell stain images | Single-cell level prediction; generalizes to unseen proteins and cell lines; visual output | Human cell lines | Requires nucleus, microtubule, and endoplasmic reticulum stain images |

| LocPro [24] | Protein sequence | Dual-channel representation (ESM2 + PROFEAT); multi-granularity (10 major or 91 sub-localizations) | Eukaryotes | Handles long sequences via segmentation; hybrid CNN-FC-BiLSTM architecture |

| ProteinFormer [25] | Biological images | Transformer architecture; integrates local and global image features; performs well on limited data | Eukaryotes | Specifically designed for microscopy image analysis |

| Light Attention [26] [27] | Protein sequence | Deep learning with attention mechanism; predicts 10 localizations | Eukaryotes | GitHub-based implementation |

Decision Framework for Tool Selection

Choosing the appropriate prediction tool depends on your available data and research question. The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting the most suitable computational approach:

Technical Support & Troubleshooting

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My protein sequence is longer than 4000 amino acids. Will DeepLoc 2.0 be able to process it? Yes, but with important caveats. DeepLoc 2.0 automatically truncates sequences longer than 4000 amino acids in slow mode (1024 in fast mode) from the middle of the sequence [22]. For full-length analysis of very long proteins, consider using LocPro, which employs a segmentation approach that divides long sequences into segments and computes a weighted average of embeddings [24].

Q2: How reliable are computational predictions for plant-specific proteins without experimental validation? Computational predictions should be treated as hypotheses rather than definitive answers, especially for plant-specific proteins. These tools are typically trained on datasets enriched with mammalian and yeast proteins [22] [24]. For plant research, use multiple prediction tools and look for consensus. Tools like AtSubP are specifically designed for Arabidopsis thaliana and may perform better for plant-specific proteins [26].

Q3: Can I predict changes in localization due to mutations or post-translational modifications? Yes, tools like PUPS are particularly capable in this regard as they can capture changes in localization driven by unique protein mutations that aren't included in standard training databases [23]. The method learns localization-determining properties from the amino acid sequence itself rather than relying solely on sequence similarity.

Q4: What's the difference between single-label and multi-label prediction, and why does it matter? Single-label prediction assigns one subcellular location per protein, while multi-label recognition (available in DeepLoc 2.0, LocPro, and ProteinFormer) can assign multiple locations, reflecting the biological reality that 20-30% of proteins localize to multiple compartments [22] [25]. For dynamic processes or proteins with multiple functions, multi-label prediction provides more biologically accurate results.

Q5: How can I interpret the attention plots in DeepLoc 2.0? The attention plots (logo-like visualizations) show which regions of the protein sequence were most important for the localization prediction. Positions with high attention values often correlate with known sorting signals, providing biological interpretability to the predictions [22]. This can help identify potential targeting sequences in novel proteins.

Common Error Messages and Solutions

Table: Troubleshooting Common Computational Prediction Issues

| Error/Issue | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| "Sequence contains invalid characters" | Non-IUPAC amino acid symbols; formatting issues | Use only standard amino acid codes (A-Z); Remove numbers, spaces, special characters; Ensure FASTA format [28] |

| "Sequence too short/long" | Outside tool-specific length limits | DeepLoc: 10-6000 aa; LocPro: Handles long sequences via segmentation; Truncate or split very long sequences if necessary [22] [24] |

| "Low confidence scores" | Novel proteins with limited homology; Ambiguous localization signals | Run multiple tools and compare results; Check for consensus localization; Consider protein family characteristics |

| "Memory error" with large batches | Insufficient computational resources | Reduce batch size; Use Fast mode in DeepLoc instead of Slow mode; For image-based tools, reduce image resolution [22] |

| Discrepant results between tools | Different training datasets; Algorithmic variations | Compare probability scores, not just binary calls; Use tools with complementary approaches (sequence vs image-based) |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Standard Workflow for Computational Protein Localization

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive workflow integrating computational prediction with experimental validation, specifically adapted for plant biology research:

Detailed Methodology: Sequence-Based Prediction Pipeline

Protocol: Multi-Tool Computational Localization Prediction

This protocol describes a robust approach for predicting protein subcellular localization using multiple complementary tools to increase confidence in predictions.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Protein Sequence in FASTA Format: Essential input for all sequence-based tools. Ensure proper formatting with a single definition line starting with ">" followed by sequence data using standard IUPAC amino acid codes [28].

- DeepLoc 2.0/2.1 Web Server: For standard eukaryotic protein localization prediction with 10 subcellular compartments and sorting signal information [22].

- LocPro Web Server: For multi-granularity analysis (10 major or 91 sub-localizations) using combined ESM2 and expert-driven features [24].

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Optional but recommended for analyzing conservation of predicted targeting signals.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Input Preparation

- Obtain protein sequence in FASTA format. The definition line should contain a unique identifier (e.g., >ProteinXYZ [organism=Arabidopsis thaliana]).

- Verify sequence contains only valid amino acid codes (A-Z, without numbers or special characters).

- For sequences longer than 4000 amino acids, note that DeepLoc will truncate from the middle, while LocPro uses a segmentation approach [22] [24].

Tool Execution

- Run DeepLoc 2.0/2.1 (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/DeepLoc-2.0/)

- Select appropriate model: "High-quality (Slow)" for single proteins or "High-throughput (Fast)" for multiple proteins

- Choose "Long output" to obtain attention plots for interpretability

- Run LocPro (https://idrblab.org/LocPro/)

- Select prediction granularity based on research needs (10 major localizations or finer sub-localizations)

- For plant-specific proteins, consider running additional plant-focused tools like AtSubP if available [26]

- Run DeepLoc 2.0/2.1 (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/DeepLoc-2.0/)

Result Analysis

- Compile results from all tools in a comparative table

- Note consensus localizations across multiple tools

- Examine attention plots in DeepLoc or importance scores in LocPro to identify potential targeting sequences

- For discordant results, consider the strength of probability scores and tool specializations

Hypothesis Generation

- Formulate testable hypotheses about protein localization

- Design experimental validation based on computational predictions

- For proteins with multiple predicted localizations, consider dynamic translocation experiments

Technical Notes:

- Computational predictions should be considered as preliminary data to guide experimental design

- Always verify critical findings with experimental methods

- Keep records of all tool versions and parameters for reproducibility

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Resources for Protein Localization Prediction

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Web Servers | DeepLoc 2.0/2.1 [22] | Eukaryotic protein localization prediction | https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/DeepLoc-2.0/ |

| LocPro [24] | Multi-granularity localization prediction | https://idrblab.org/LocPro/ | |

| BUSCA [26] | Unified subcellular component annotator | https://busca.biocomp.unibo.it/ | |

| Standalone Software | Light Attention [27] | Deep learning with attention mechanism | GitHub: HannesStark/protein-localization |

| Databases | Human Protein Atlas [23] [25] | Reference dataset with protein localization images | https://www.proteinatlas.org/ |

| UniProt [24] | Comprehensive protein sequence and functional information | https://www.uniprot.org/ | |

| Specialized Plant Tools | AtSubP [26] | Arabidopsis thaliana subcellular localization prediction | http://bioinfo3.noble.org/AtSubP/ |

| cropPAL [26] | Crop protein subcellular localization portal | http://crop-pal.org/ |

Advanced Applications in Plant Research

Integrating Computational Predictions with Experimental Design

Computational prediction tools become particularly powerful when integrated into a holistic research pipeline. For plant biology, this integration enables efficient prioritization of candidate proteins for functional characterization. The protein language models underlying tools like DeepLoc 2.0 and LocPro have demonstrated remarkable ability to capture structural and functional information directly from amino acid sequences, often identifying localization signals that escape simple homology-based approaches [22] [24].

When working with plant-specific proteins or proteins with unknown function, computational predictions can guide experimental design in several ways:

- Target Selection: Prioritize proteins with clear localization signals for initial experimental validation

- Method Selection: Choose appropriate microscopic techniques based on predicted compartments

- Control Design: Select appropriate positive and negative controls based on predicted localizations

- Dynamic Studies: For proteins with multiple predicted localizations, design time-course or condition-dependent experiments

The ongoing development of models that can generalize to unseen proteins and cell types, such as PUPS, promises even greater utility for plant research where characterized homologs may be limited [23]. As these tools continue to evolve, they will become increasingly integrated into standard practice for systematic protein localization determination in plants.

Evolutionary Conservation and Plant-Specific Targeting Mechanisms

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary methods for determining protein subcellular localization in plants? Researchers typically use a combination of computational prediction tools and experimental validation. Computational models, such as ProteinFormer and ProtGPS, can predict localization from protein sequences or biological images with high accuracy [19] [29]. Experimentally, the most common method involves fusing the protein of interest to an Autofluorescent Protein (AFP), like GFP, and observing its localization in plant cells via fluorescence or confocal microscopy. This often requires co-expression with known subcellular markers to confirm the specific compartment [1].

FAQ 2: Why is the evolutionary conservation of protein localization signals important? Evolutionary conservation can reveal critical functional domains within a protein. For plant proteins, understanding their recent evolutionary history, including factors like metapopulation functioning and dispersal ability, is crucial for conservation biology and can inform on the constraints and flexibility of localization signals [30]. Disruption of these evolved traits can make species particularly vulnerable to disturbances, analogous to how a mutation in a localization signal could lead to protein mislocalization and dysfunction [29] [30].

FAQ 3: My protein localization results are unclear or seem artifactual. What are common pitfalls? Common issues include:

- Lack of Proper Controls: Always include known subcellular markers co-expressed in the same cells to serve as a reference point [1].

- Cross-Talk: When performing co-localization studies, test each fluorescent protein fusion individually first to ensure their emission signals do not bleed into each other's detection channels [1].

- Biological Relevance: The observed localization pattern must make biological sense. Overexpression can lead to artifactual accumulation in non-native compartments. Consider the plant's physiological state, developmental stage, and whether it is infected by pathogens, as these can influence localization [1].

- Validation: Use supporting data, such as immunoblotting, to confirm the expression and size of the fusion protein [1].

FAQ 4: How can I study protein-protein interactions in relation to localization? Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) is a common and powerful technique. It involves fusing two interacting protein partners to split halves of a fluorescent protein. If the proteins interact, the fluorophore is reconstituted, fluorescing and revealing both the interaction and the subcellular location where it occurs [1].

FAQ 5: What does "colocalization" truly mean in a quantitative sense? Colocalization is not simply two proteins appearing in the same general area under a microscope. True colocalization requires a statistical, pixel-for-pixel correlation between the two fluorescence signals across the image. It is inappropriate to claim colocalization of a protein in punctate foci against another protein that occupies the entire micrograph [1].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Fluorescence Detected | Fusion protein not expressed or folded correctly. | Validate expression by immunoblotting. Check sequence for PCR errors and ensure fusion does not disrupt a critical protein domain [1]. |

| Diffuse, Non-Specific Localization | Protein overexpression; mislocalization due to artifactual saturation. | Use a weaker promoter or inducible expression system. Conduct a time-course experiment to observe early expression patterns [1]. |

| Localization Pattern Does Not Match Prediction | Discrepancy between computational prediction and biological reality. | Use multiple prediction algorithms. Remember that algorithms predict based on sequence motifs, which may be masked or context-dependent [1]. |

| High Background Noise | Non-specific antibody binding or autofluorescence. | Include controls without primary antibody. Use spectral imaging to distinguish autofluorescence from specific signal [1]. |

Quantitative Performance of Protein Localization Prediction Tools

The following table summarizes the performance of several AI-based prediction models as reported in recent literature. These tools offer a powerful starting point for generating localization hypotheses.

| Model Name | Input Data | Key Performance Metrics | Key Application / Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| ProteinFormer [19] | Protein biological images | 91% F-score (single-label), 81% F-score (multi-label) on Cyto_2017 dataset [19]. | Integrates ResNet for local features and Transformer for global context. Effective on sufficient data. |

| GL-ProteinFormer [19] | Protein biological images | 81% F-score on limited-sample IHC_2021 dataset; 4% Accuracy improvement with ConvFFN [19]. | Enhanced for small-sample scenarios; uses residual learning and inductive bias. |

| ProtGPS [29] | Protein amino acid sequence | High accuracy in predicting localization to 12 compartment types; validated with experimental tests on designed proteins [29]. | Can predict effect of disease-associated mutations on localization; can generate novel protein sequences that localize to a specific compartment. |

Core Experimental Protocol: Protein Localization via Agrobacterium-Mediated Transient Expression

This is a standard method for rapidly expressing and visualizing protein localization in plant leaves [1].

- Vector Construction: Clone the coding sequence (CDS) of your protein of interest (POI) into an appropriate plant expression vector, creating an in-frame fusion with a selected Autofluorescent Protein (AFP) like GFP or RFP.

- Agrobacterium Transformation: Introduce the constructed plasmid into a tractable Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain (e.g., LBA4404, C58C1).

- Culture Preparation:

- Streak transformed Agrobacterium onto LB agar plates with the appropriate antibiotics. Incubate at 28°C for 1-3 days.

- Use a sterile loop to harvest cells and resuspend them in agroinfiltration buffer (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl₂, 150 μM acetosyringone, pH 5.9).

- Adjust the suspension to an optical density at 600 nm (OD₆₀₀) of 0.1 to 0.5.

- Infiltration: Using a needleless syringe, gently press the tip against the underside of a leaf from a suitable plant (e.g., Nicotiana benthamiana) and infiltrate the bacterial suspension. The infiltrated area will appear water-soaked.

- Incubation: Allow the infiltrated plants to grow under normal conditions for 2-4 days to permit gene expression and protein accumulation.

- Microscopy: Harvest the infiltrated leaf tissue and image it using a confocal or epifluorescence microscope, using the appropriate excitation/emission settings for your AFP. Always include a co-infiltrated subcellular marker as a control.

Experimental Workflow for Systematic Protein Localization

The diagram below outlines a comprehensive workflow for a protein localization study, integrating both computational and experimental biology phases.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key reagents and tools essential for conducting protein localization experiments in plants.

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Autofluorescent Proteins (AFPs) | Tag for protein visualization in live or fixed cells. | GFP, RFP, CFP, YFP; used as C-terminal or N-terminal fusions [1]. |

| SNAP-tag / CLIP-tag | Protein tag for specific covalent labeling with fluorescent substrates. | Allows labeling with a wide selection of fluorescent dyes; useful for pulse-chase and dual-labeling experiments [31]. |

| Subcellular Marker Lines | Transgenic plants expressing compartment-specific AFP fusions. | Essential controls for definitively identifying organelles (e.g., nucleus, ER, Golgi) [1]. |

| Binary Vectors | Plasmids for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. | Vectors like pGD or pSITE for transient or stable expression [1]. |

| Agroinfiltration Buffer | Solution for delivering Agrobacterium into plant leaf tissue. | Contains MES, MgCl₂, and acetosyringone to induce virulence [1]. |

| AI Prediction Tools | Computational prediction of localization from sequence or image. | ProtGPS (sequence-based) [29], ProteinFormer (image-based) [19]. |

Experimental Techniques: From Computational Tools to Laboratory Protocols

In plant cellular biology, the subcellular localization of a protein is a fundamental determinant of its function. Computational prediction tools have become indispensable for generating rapid, testable hypotheses about protein localization, guiding subsequent experimental work. This technical support center focuses on three prominent tools—LOCALIZER, Plant-mPLoc, and TargetP—providing troubleshooting guides and FAQs framed within the context of systematic protein localization determination for plant research. These resources are designed to assist researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in effectively deploying these tools and interpreting their results.

Tool Comparison and Selection Guide

The table below provides a quantitative comparison of the three tools to aid in selection based on research objectives.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of LOCALIZER, Plant-mPLoc, and TargetP

| Feature | LOCALIZER | Plant-mPLoc | TargetP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Specialty | Predicting effector protein localization; identifying non-N-terminal transit peptides [32] | Predicting multi-localization proteins; broad subcellular coverage [33] | Identifying N-terminal sorting signals (SP, mTP, cTP, luTP) [34] [35] |

| Number of Locations Covered | 3 (Chloroplast, Mitochondria, Nucleus) [32] | 12 (e.g., Cell membrane, Cell wall, Chloroplast, Cytoplasm, etc.) [33] | 4 in Plants (cTP, mTP, SP, luTP) [34] |

| Unique Capability | Sliding window approach to find transit peptides after signal peptides/pro-domains [32] | Can predict proteins simultaneously existing in two or more locations [33] | Predicts cleavage site positions; uses deep learning (BiLSTM) [34] [35] |

| Reported Accuracy (Chloroplast) | Sensitivity: 72.5%, PPV: 79.1% [32] | Information Not Provided | Performance is superior to TargetP 1.1 and other older methods [35] |

| Reported Accuracy (Mitochondria) | Sensitivity: 60%, PPV: 58.2% [32] | Information Not Provided | Performance is superior to TargetP 1.1 and other older methods [35] |

| Ideal Use Case | Prioritizing fungal/oomycete effector candidates for functional studies [32] | Identifying dual-targeted native plant proteins [33] | Determining the presence and cleavage site of N-terminal targeting peptides [34] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Tool Selection

Q1: I have a new plant protein sequence. Which tool should I start with? A1: For a comprehensive initial screen, especially for native plant proteins, Plant-mPLoc is recommended due to its coverage of 12 location sites. If your hypothesis involves secretion, mitochondria, or chloroplasts, TargetP 2.0 provides high-confidence prediction of N-terminal targeting peptides and their cleavage sites. If you are working with pathogen effector proteins, LOCALIZER is the specialized choice as it is uniquely designed to handle their complex sequence architecture [32] [33].

Q2: How can I predict if a protein localizes to multiple compartments? A2: Plant-mPLoc is the only tool among the three specifically designed to "deal with multiplex plant proteins that can simultaneously exist at two, or move between, two or more different location sites" [33]. Other tools like WoLF PSORT or YLoc+ also offer this capability, but it is a key strength of Plant-mPLoc [32].

Tool-Specific Issues

Q3: LOCALIZER predicts no localization for my effector protein, but I have experimental evidence suggesting chloroplast localization. What could be wrong? A3: This is a common scenario. Re-check the sequence you input into LOCALIZER.

- Ensure the sequence is mature: LOCALIZER's "Effector mode" uses a sliding window specifically to find transit peptides that may not be at the very N-terminus, often because they are downstream of a signal peptide and a pro-domain. If you input only the mature sequence (after the pro-domain), the critical targeting peptide may have been truncated [32].

- Verify the input format: Confirm the sequence is in correct FASTA format and uses the standard 20 amino acid codes.

Q4: Plant-mPLoc requires a protein's accession number. What should I do if my protein is novel or synthetic and has no accession number? A4: This is a known limitation of Plant-mPLoc and other GO-based predictors. For novel/synthetic proteins without an accession number, you cannot use the GO-information-based prediction mode. However, Plant-mPLoc integrates a pseudo amino acid composition (PseAAC) approach that can be used as a complementary method for sequences without database annotations [33].

Q5: TargetP 2.0 and other tools show conflicting predictions for my protein. How should I proceed? A5: Conflicting predictions are common. We recommend the following troubleshooting protocol:

- Verify the organism group: Ensure you have selected the "Plant" option in TargetP, as the underlying models are trained specifically on plant targeting peptides [34].

- Run a consensus check: Use multiple tools (e.g., LOCALIZER, TargetP, WoLF PSORT) and look for agreement between at least two independent methods. This increases confidence in the prediction.

- Inspect the N-terminus: Manually examine the first 50-100 amino acids for hallmarks of targeting peptides, such as enrichment of serine/threonine (cTPs) or arginine (mTPs), and the absence of acidic residues [32] [35].

- Proceed to experimentation: Computational tools are designed to guide experiments, not replace them. A conflicting result should be resolved by experimental validation, for example, using GFP fusion constructs and confocal microscopy.

Experimental Validation Workflow

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for using these computational tools and validating predictions experimentally.

Workflow for Predicting and Validating Protein Localization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The table below lists essential materials for experimental validation of computational predictions.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Experimental Validation of Protein Localization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein) | A reporter protein fused to the protein of interest to visualize its location within living cells using fluorescence microscopy [32]. |

| Confocal Microscope | Essential for obtaining high-resolution, clear images of GFP fluorescence within specific subcellular compartments, avoiding out-of-focus light [32]. |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | A common vector for transient transformation in many plant species (e.g., tobacco) to deliver and express the GFP-fusion construct [32]. |

| Plasmid Vectors | Used for cloning the gene of interest fused to GFP. Requires appropriate promoters and restriction sites for the plant system. |

| Organelle-Specific Markers | Fluorescent tags (e.g., RFP, mCherry) targeting known organelles (chloroplast, mitochondria, etc.) for co-localization studies. |

| Protocol for Transient Expression | A standardized method for infiltrating Agrobacterium into plant leaves to ensure consistent and reliable expression of the construct [32]. |

Fluorescent protein fusions, particularly those involving Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP), are foundational tools in modern plant research for determining protein localization, dynamics, and interactions in living cells. By fusing the gene encoding GFP to a gene of interest, researchers can visualize the subcellular compartment, movement, and complex formation of the resultant fusion protein in real time, providing insights into its function. This methodology, framed within the systematic determination of protein localization in plants, allows for the direct observation of biological processes without the artifacts associated with fixed-cell techniques [36] [37]. Common applications in plant research include studying receptor-like kinase (RLK) complexes, RNA-protein interactions, and the production of recombinant biopharmaceuticals in plant bioreactors [38] [39] [37].

The techniques rely on advanced imaging technologies, such as Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) and confocal microscopy. FRET enables the study of protein-protein interactions by measuring energy transfer between a donor and acceptor fluorophore, which occurs only when they are in very close proximity (typically <10 nm) [39] [40]. This makes it an powerful method for validating direct molecular interactions, such as those between cell surface receptors and their co-receptors in plants [39].

Troubleshooting Guides

Live-Cell Imaging and Microscopy

| Problem | Possible Cause | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unexpected background fluorescence | Endogenous tissue autofluorescence (common in paraffin sections) [41]. | Test unstained tissue under all filter sets; reduce autofluorescence by washing with 1 mg/mL sodium borohydride prior to blocking and labeling [41]. |

| Low signal-to-noise ratio | Non-specific antibody binding due to dye charge; low-affinity primary or secondary antibodies [41]. | Use a signal enhancer (e.g., Image-iT FX Signal Enhancer) to block charge-based interactions; post-fix with formaldehyde after secondary antibody application and use a hardening mounting medium [41]. |

| Rapid photobleaching | Generation of free radicals; dye sensitivity; intense illumination [41]. | Use an antifade reagent (e.g., ProLong Live for live cells, ProLong Diamond for fixed samples); choose more photostable dyes (e.g., Alexa Fluor dyes); reduce laser power or exposure time [41]. |

| Objective lens hits sample/vessel | Incorrect objective type; improper calibration or focusing [41]. | Use Long-Working Distance (LWD) objectives for imaging through slides/plates; calibrate objectives with a calibration slide; manually focus objectives downward when not in use [41]. |

| Poor resolution or blurry images | Sample opacity; misaligned objective turret; incorrect condenser setting [41]. | Use a thinner sample; ensure objectives are fully threaded and the turret is aligned; check that brightfield condenser sliders are fully inserted [41]. |

Molecular and Biochemical Assays

| Problem | Possible Cause | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No fluorescence in transfected tissue | Poor protein expression or folding; incorrect filter sets [37]. | Confirm construct design and protein folding; verify using transient expression assays (e.g., agroinfiltration) before stable transformation; check microscope filter compatibility with your fluorescent protein [37]. |

| High background in co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) | Non-specific binding to the beads or GFP tag itself [38]. | Include a rigorous control (e.g., GFP-only expressing line); ensure the GFP-Trap agarose is not saturated [38]. |

| Inconsistent FRET efficiency | Variable expression levels of donor and acceptor fluorophores; improper spectral unmixing [39]. | Use intramolecular FRET probes where donor/acceptor ratio is fixed; employ advanced unmixing algorithms (e.g., Richardson-Lucy) for low signal-to-noise ratio data [42] [39]. |

| Mislocalization of fusion protein | Fluorescent protein tag interfering with native protein function or targeting signals [39]. | Try tagging the protein at the opposite terminus (N- vs. C-terminal); use shorter, more flexible linkers between the protein and the fluorophore [39]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my GFP fusion protein not fluorescing after successful plant transformation? A1: First, confirm the expression of the fusion protein at the RNA and protein level via RT-PCR and Western blotting [37]. If the protein is expressed but not fluorescent, the fluorescent protein may not have folded correctly. Use transient expression assays like agroinfiltration for rapid construct validation (results within 3 days) before proceeding to stable transformation [37].

Q2: How can I be sure that my observed protein-protein interaction via FRET is specific? A2: Employ a comprehensive set of controls. These include expressing the donor and acceptor fluorophores separately, using pairs of proteins known not to interact, and mutating the interaction domains of your proteins of interest. For membrane proteins, an inactive fusion protein that fails to interact will often be retained in the endoplasmic reticulum, providing a clear visual control [39].

Q3: What is the best negative control for a GFP-Trap co-immunoprecipitation experiment? A3: The most critical control is a plant line expressing free GFP (e.g., a 35S::GFP construct) ideally in the same vector background as your fusion protein. This control identifies RNAs that bind non-specifically to the GFP tag or the agarose matrix. An alternative is using a line expressing a different, unrelated GFP-tagged protein [38].

Q4: My fluorescent signal is fading too quickly during live imaging. What can I do? A4: Photobleaching is a common issue. To mitigate it, you can: 1) Add an antifade reagent like ProLong Live Antifade Reagent to the imaging medium; 2) Reduce light exposure by lowering laser power, using neutral density filters, and minimizing viewing time; and 3) Choose more photostable fluorescent proteins or dyes [41].

Q5: How do I choose the right FRET pair for my experiment in plant cells? A5: An ideal FRET pair should have significant spectral overlap, be bright enough for detection, and not perturb the function or localization of your fused proteins. While eGFP-mCherry is widely used, other pairs like mTurquoise2-sYFP2 have also been successfully applied in plant systems to study RLK interactions [39]. Test several pairs for optimal performance.

Essential Experimental Protocols

GFP-Trap Co-immunoprecipitation for RNA-Protein Interaction

This protocol is used to confirm direct interactions between a known RNA-binding protein and its candidate RNA targets in plants [38].

- Workflow Diagram Title: GFP-Trap Co-IP for RNA-Protein Interaction

- Graphviz Diagram:

- Key Materials & Reagents:

- Detailed Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Use leaves from 20-day-old Arabidopsis plants overexpressing the GFP-tagged RNA-binding protein. Always include a control line expressing GFP alone [38].

- Protein Extraction: Grind frozen plant tissue to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen. Homogenize the powder in RIP A buffer (10 mM Tris/Cl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 1% deoxycholate, 0.09% Na-Azide, 2.5 mM MgCl₂, 1 mM PMSF) to extract the proteins [38].

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate the protein extract with GFP-Trap agarose beads. Do not exceed the binding capacity of the beads (12 µg GFP per 10 µL beads). Gently mix the suspension for several hours at 4°C to allow the GFP-tagged protein and its bound RNA to bind to the matrix [38].

- Washing: Pellet the beads and wash them thoroughly with washing buffer (10 mM Tris/Cl pH 7.5) to remove non-specifically bound material [38].

- RNA Analysis: Elute the co-precipitated RNA-protein complexes from the beads. Extract the RNA using a method like TRIzol. Finally, analyze the presence of specific candidate RNA transcripts by Reverse-Transcription PCR (RT-PCR) [38].

Agrobacterium-Mediated Transient Expression for Rapid Validation

This protocol allows for quick confirmation of protein expression and subcellular localization in plant leaves before undertaking stable transformation [37].

- Workflow Diagram Title: Transient Expression via Agroinfiltration

- Graphviz Diagram:

- Key Materials & Reagents:

- Detailed Methodology:

- Vector Construction: Clone the gene of interest, fused to GFP, into a plant binary vector [37].

- Agrobacterium Preparation: Introduce the binary vector into A. tumefaciens. Grow a culture of the transformed bacteria in YEP medium with appropriate antibiotics until it reaches the log phase [37].

- Induction: Pellet the bacteria and resuspend them in infiltration medium containing acetosyringone, which induces the virulence genes necessary for T-DNA transfer [37].

- Infiltration: Using a syringe without a needle, press the tip against the abaxial (lower) side of a tobacco leaf and gently inject the bacterial suspension, allowing it to infiltrate the intercellular spaces [37].

- Analysis: Incubate the plants for 2-3 days. The expressed GFP fusion protein can then be visualized directly in the leaf epidermis using fluorescence or confocal laser scanning microscopy to determine its subcellular localization [37].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents essential for experiments involving fluorescent protein fusions and live-cell imaging in plants.

| Reagent | Function/Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GFP-Trap Agarose | High-affinity immunoprecipitation of GFP-fused proteins and their direct interaction partners (e.g., RNAs or other proteins) from plant extracts [38]. | ChromoTek, cat. no. gta-20. Based on a GFP-binding nanobody; offers high specificity and low background [38]. |

| Subcellular Localization Markers | Reference standards for identifying specific organelles (e.g., nucleus, mitochondria, plasma membrane) by co-localization studies [43]. | Available from plasmid repositories (e.g., Addgene). Examples: 3xnls-mTurquoise2 (nucleus), 4xmts-mScarlet-I (mitochondria), Lck-mTurquoise2 (plasma membrane) [43]. |

| Acridine Orange (AO) | A metachromatic fluorescent dye for live-cell imaging and high-content phenotypic profiling. It stains nucleic acids and acidic compartments, highlighting nuclei and cytoplasmic vesicles [44]. | Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. A1301. Used in "Live Cell Painting" protocols for cost-effective, multiparametric live-cell analysis [44]. |

| FRET-FLIM Pairs | Fluorophore pairs used to study protein-protein interactions in live plant cells via Förster Resonance Energy Transfer measured by Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) [39]. | Validated pairs for plants include mTurquoise2-sYFP2 and eGFP-mCherry. The choice depends on brightness, photostability, and minimal spectral cross-talk [39]. |

| ProLong Antifade Mountants | Reagents to reduce photobleaching in fluorescence imaging. Different formulations are available for live-cell and fixed-cell applications [41]. | e.g., ProLong Live (for live cells), ProLong Diamond (for fixed samples). They contain antioxidants that scavenge free radicals responsible for dye fading [41]. |

Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) for Protein Interactions

Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) is a powerful technique used to visualize protein-protein interactions directly within the living cell. The assay is based on the reconstitution of a fluorescent signal when two non-fluorescent fragments of a fluorescent protein are brought together by an interaction between proteins they are fused to [45] [46]. This not only confirms an interaction but also provides valuable information about the subcellular localization of the protein complex.

For researchers focused on systematic protein localization in plants, BiFC offers a critical advantage: the ability to map the precise cellular compartment where interactions occur under near-physiological conditions. This technique has become indispensable for validating interactions discovered in large-scale yeast two-hybrid screens and for studying the dynamics of complex formation in planta.

Troubleshooting Common BiFC Issues

FAQ: My BiFC experiment shows fluorescence. Does this automatically mean my proteins interact?

Not necessarily. A fluorescent signal can sometimes result from non-specific, artifactual interactions, especially when proteins are overexpressed [45] [47]. The self-assembly propensity of the fluorescent protein fragments themselves is a major source of false positives. To confidently conclude a specific interaction, you must include rigorous negative controls.

FAQ: What are the best negative controls for a BiFC assay?

The quality of your controls is the most critical factor for a reliable BiFC experiment. The table below summarizes the most effective negative controls, ranked by their reliability.

Table: Recommended Negative Controls for BiFC Experiments

| Control Type | Description | Rationale & Suitability |

|---|---|---|

| Mutated Protein [48] [47] | Use a version of your protein with a mutated or deleted interaction domain. | This is the gold standard. If the mutation specifically disrupts the interaction, fluorescence should be abolished. |

| Unrelated Protein [47] | Fuse one FP fragment to a protein from a different family or pathway that is not expected to interact. | A good control, but ensure the unrelated protein has similar expression and localization. |

| Alternative Fusion Orientation | Test all possible combinations of N- and C-terminal fusions for both proteins. | An interaction should be observed regardless of fusion orientation if it is robust. |

| Avoid: Cytosolic Fragment [48] [47] | Expressing a free, unfused FP fragment in the cytosol. | Not recommended. This control does not test for self-assembly in the compartment where your protein is located. |

FAQ: I am not seeing any fluorescence, but my proteins are suspected to interact. What could be wrong?

This false-negative result can have several causes:

- Problem: Insufficient Fluorophore Maturation Time. The reconstituted fluorophore requires time (from minutes to hours) to form its mature, fluorescent structure [49] [50].

- Solution: Ensure you are allowing enough time after transfection or induction (often 16-24 hours) for the signal to develop.

- Problem: Suboptimal Fusion Protein Design. The fusion of the FP fragment might be blocking the interaction interface or impairing the protein's folding or localization [46].

- Solution: Try different fusion orientations (N-terminal or C-terminal for each protein and FP fragment). Use structural information if available to guide the design.

- Problem: Mismatched Subcellular Localization. The two proteins might not be co-localized in the same cellular compartment.

- Solution: Verify the localization of each fusion protein independently using full-length fluorescent tags.

FAQ: The fluorescence signal is very weak. How can I enhance it?

A weak signal can be challenging to distinguish from background. Consider these approaches:

- Optimize the Split Site: Different split sites in the fluorescent protein (e.g., after amino acid 154, 172, or 210) offer varying trade-offs between signal intensity and background [45] [47]. The 174/175 split used in MoBiFC is a modern option that reduces self-assembly [48].

- Use a Brightness-Optimized FP: Newer fluorescent proteins like mVenus, mNeonGreen, or mScarlet are brighter and more photostable than the original eYFP [51].

- Ratiometric Quantification: Co-express a reference fluorescent protein (e.g., CFP) from the same plasmid as your BiFC constructs. This allows you to normalize the BiFC signal to the transformation efficiency, providing a more robust, quantitative measure of interaction strength [48].

- Check Expression Levels: Use immunoblotting to confirm that your fusion proteins are being expressed at the expected molecular weights and are not degraded.

FAQ: Can I use BiFC to study weak or transient interactions?

Yes, this is a key strength of the technique. The reconstituted fluorescent complex is typically very stable and often irreversible, which allows it to "trap" and visualize even weak or transient interactions that are difficult to detect with other methods [45] [49].

FAQ: Why is my BiFC signal localized differently than my individual proteins?

This is a critical observation. The location of the BiFC signal indicates the compartment where the interaction takes place. If a protein is shuttled between compartments, its interaction with a partner might only occur in one specific location. Always confirm the localization of the individual proteins, as the BiFC signal reveals the location of the complex, not the free proteins.

Experimental Protocols & Best Practices

Standard Workflow for a Plant BiFC Experiment

The following diagram outlines the key steps for a robust BiFC experiment in plants, incorporating essential controls and validation.

Detailed Methodology: Transient BiFC in Nicotiana benthamiana

This protocol is adapted from modern modular BiFC (MoBiFC) systems for high-quality, quantifiable results [48].

Vector Construction:

- Use a modular cloning system (e.g., MoClo) to assemble constructs. Fuse your protein of interest (POI) to the N-terminal (e.g., nYFP [1-174]) or C-terminal (e.g., cYFP [175-]) fragment of YFP.

- Crucially, include a reference FP (e.g., nucleo-cytoplasmic CFP) on the same T-DNA plasmid for ratiometric quantification.

- For chloroplast proteins, ensure the chloroplast transit peptide (CTP) is correctly positioned. You may need to use the mature protein CDS fused to a well-characterized CTP (e.g., from Rubisco small subunit).

Plant Material and Transformation:

- Grow Nicotiana benthamiana plants for 4-5 weeks under standard conditions.

- Use Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains (e.g., GV3101) to transiently express your BiFC constructs. Infiltrate young leaves with a bacterial suspension (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.3-0.5 for each construct).

Incubation and Sample Preparation:

- After infiltration, keep plants in normal growth conditions for 48-72 hours to allow for protein expression, interaction, and fluorophore maturation.

- For imaging, prepare leaf sections by mounting them in water under a coverslip.

Microscopy and Image Analysis:

- Image using a confocal laser scanning microscope. Set acquisition parameters to avoid signal saturation.

- For YFP reconstitution, use excitation/emission settings of 514 nm/525-550 nm. For the CFP reference, use 458 nm/470-500 nm.

- Quantitative Analysis: Use image analysis software (e.g., Fiji/ImageJ) to measure the mean fluorescence intensity of the BiFC signal (YFP channel) and the reference signal (CFP channel) in the same region of interest (ROI). Calculate a BiFC/CFP ratio for each sample and control. Statistically compare the ratio of your test pair to the negative controls.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for BiFC

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Protein Fragments | The non-fluorescent halves that reconstitute upon protein interaction. | YFP variants (mVenus, Venus): Most common. Splits at aa 154/155, 172/173, or 174/175 [45] [51]. Green/Red FPs: mNeonGreen2, sfGFP, mScarlet, sfCherry for multiplexing [51]. |

| Modular Cloning System | Simplifies the creation of multiple fusion protein combinations. | MoBiFC Toolkit: A Goldengate-based system for assembling fusions with reference FPs on a single plasmid, ideal for organellar studies [48]. |

| Expression Vectors | Plasmids for expressing fusion proteins in plant cells. | Vectors with weak promoters to avoid overexpression artifacts; Gateway-compatible vectors for high-throughput cloning [52] [47]. |

| Reference Fluorescent Protein | An internal control for normalization and quantification. | Co-expressed CFP or similar FP with distinct spectral properties enables ratiometric analysis, correcting for variation in transformation efficiency [48]. |

| Positive Control Pairs | Proteins with a known, validated interaction. | e.g., HSP21/HSP21 (homodimer) or HSP21/PTAC5 for chloroplast interactions [48]. Essential for validating your experimental setup. |

| Validated Negative Control | A non-interacting protein pair for benchmarking background signal. | e.g., HSP21/ΔPTAC5 (a truncated version of PTAC5) or chloroplastic mCHERRY [48]. |

Advanced Applications & Diagram

BiFC is a versatile technique that can be extended beyond simple binary interactions. The following diagram illustrates the core principle of BiFC and two of its advanced applications: multicolor BiFC and its use in visualizing genomic loci.

Advanced Applications Explained:

- Multicolor BiFC: This application allows for the simultaneous visualization of two different protein complexes in the same cell. This is achieved by using fragments from spectrally distinct fluorescent proteins (e.g., CFP and YFP). This is powerful for studying competition between interaction partners or the formation of alternative complexes within a network [49] [47].