Smart Sensing 2025: Next-Generation Sensor Technologies Revolutionizing Crop Planting and Precision Agriculture

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of advanced sensor technologies that are transforming crop planting in modern precision agriculture.

Smart Sensing 2025: Next-Generation Sensor Technologies Revolutionizing Crop Planting and Precision Agriculture

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of advanced sensor technologies that are transforming crop planting in modern precision agriculture. It explores the foundational principles of smart sensors, details the specific functions and real-world applications of key sensor types—including soil moisture, nutrient, aerial, and climate monitoring systems—and addresses critical implementation challenges such as data security, integration, and cost. Aimed at agricultural researchers and scientists, the content synthesizes validation data and comparative performance metrics to guide technology selection and discusses future trajectories integrating AI, robotics, and biotechnology for enhanced crop management and yield optimization.

The Foundation of Smart Farming: Understanding Advanced Agricultural Sensor Technologies

Precision agriculture represents a fundamental transformation in farming methodology, moving away from traditional uniform field management to a site-specific approach that acknowledges and manages inherent variability within fields [1] [2]. This paradigm shift transforms farming from a practice based largely on experience and intuition into a data-driven science that enhances traditional knowledge with objective measurements and analysis [2]. Where traditional mechanized farming applied uniform treatments for "average" conditions—necessarily leading to over- and under-application of inputs—precision agriculture enables farmers to manage different parts of a field separately based on precise, location-specific data [1]. This evolution marks a return to the principles of traditional small-scale farming, where intimate knowledge of each field section informed specific management practices, now enabled by advanced technologies that allow this approach to be scaled to modern agricultural operations [1] [2].

Core Principles of Precision Agriculture

Site-Specific Management

The foundational principle of precision agriculture involves dividing fields into management zones with unique characteristics and requirements, rather than treating fields as homogeneous units [2]. This approach recognizes that natural variability in soil types, nutrient levels, moisture content, and terrain significantly impacts crop performance [1] [2]. Through site-specific management, each zone receives customized treatment optimized for its particular conditions, from seeding rates to fertilizer blends [2].

Variable Rate Application (VRA)

Variable rate application technology enables farmers to apply seeds, fertilizers, water, and crop protection products at different rates across a field based on the specific needs of each area [2] [3]. This technology uses sensors or preprogrammed maps to determine optimal application rates, supported by technologies such as GPS, yield monitors, and crop and soil sensors [3]. Unlike conventional uniform application, VRA applies resources precisely where and when they're needed, significantly reducing waste while improving crop performance [2].

Data-Driven Decision Making

Precision agriculture relies on data-driven procedures to enhance agricultural efficiency by minimizing inputs and waste while maximizing yield quantity and quality [4]. This approach collects vast amounts of data through various technologies: soil sensors measure moisture and nutrient levels; GPS-guided machinery tracks yields during harvest; satellite and drone imagery reveal crop health patterns invisible to the naked eye [2]. This wealth of information allows farmers to make informed decisions based on concrete evidence rather than assumptions or generalizations [2].

Resource Efficiency

At its heart, precision agriculture aims to achieve maximum productivity with minimum waste [2]. By applying inputs with precision rather than excess, farmers significantly reduce their environmental footprint while often improving their bottom line [2] [3]. This efficiency reduces costs while minimizing environmental impacts like nutrient runoff and groundwater contamination [2]. Research quantifies that precision agriculture technologies can lead to a 9% reduction in herbicide and pesticide use, 6% reduction in fossil fuel use, and 4% reduction in water use while increasing crop production by 4% [3].

Technological Foundations Enabling Precision Management

Sensing and Monitoring Technologies

Advanced sensor technologies form the critical backbone of data collection in precision agriculture. Soil and plant sensors monitor crucial variables including moisture content, temperature, electrical conductivity, and pH levels [2]. These can be stationary for continuous data from fixed locations or mobile for generating comprehensive soil maps when attached to farm equipment [2]. Emerging sensor technologies like the WolfSens system developed at North Carolina State University can detect plant diseases before visible signs appear by 'sniffing' volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that plants emit—detecting viral infections in tomatoes more than a week before symptoms become visible [5].

Hyperspectral imaging and polarized light sensors further enhance monitoring capabilities. Researchers at Mississippi State University are developing spectral signature analysis that can estimate different soil properties like organic matter or identify plant stresses and diseases beforehand [6]. Similarly, polarization technology helps sensors accurately capture leaf color regardless of glare, overcoming a significant challenge in traditional imaging systems [5].

GPS and Guidance Systems

Global Positioning System (GPS) technology serves as the fundamental geospatial framework for precision agriculture [1] [2]. High-accuracy GPS receivers mounted on farm equipment enable positioning with centimeter-level precision, allowing for extremely accurate field mapping, soil sampling, and equipment guidance [2]. Auto-guidance systems, also known as auto-steer, use GPS to automatically steer machinery and avoid overlap during tilling, planting, spraying, and harvesting [3]. This more efficient operation reduces time, labor, fuel, and materials used while ensuring precise application [3].

Remote Sensing and Aerial Imaging

Remote sensing technologies including satellites and drones provide multi-scale monitoring capabilities for agricultural management [1] [7]. Satellite imagery offers regular, high-resolution data for objective field-wide crop health assessments and resource tracking [7]. Drone technology equipped with high-resolution cameras and sensors provides timely, high-detail field images for planning, scouting, and analysis [7] [2]. Multispectral and thermal imaging cameras capture light wavelengths beyond human vision, revealing plant stress, disease outbreaks, irrigation issues, and nutrient deficiencies before they become visible [2].

Data Integration and Analytics Platforms

Farm management software integrates data from multiple sources to provide actionable insights and enable coordinated decision-making [8] [2]. These platforms incorporate predictive analytics and artificial intelligence to help farmers forecast yields, anticipate pest and disease pressure, and optimize resource allocation [2]. Modern systems employ sophisticated machine learning models to process vast amounts of data from various sources, identifying trends, predicting crop yields, detecting diseases early, and optimizing planting schedules [7]. Data visualization tools transform complex agricultural data into graphical formats like charts, graphs, and maps, providing clear insights that help in managing crop health, optimizing resources, and predicting yields [8].

Quantitative Benefits of Precision Agriculture

Research conducted by the Association of Equipment Manufacturers (AEM) in partnership with major agricultural organizations has quantified the significant environmental benefits of precision agriculture technologies [3]. The data demonstrates substantial improvements in efficiency and productivity while reducing environmental impact.

Table 1: Quantified Environmental Benefits of Precision Agriculture Technologies

| Benefit Category | Improvement with Current Adoption | Potential with Full Adoption |

|---|---|---|

| Crop Production | 4% increase [3] | Additional 6% gain [3] |

| Fertilizer Efficiency | 7% increase in placement efficiency [3] | Additional 14% efficiency gain [3] |

| Herbicide & Pesticide Use | 9% reduction [3] | Additional 15% reduction (48M fewer lbs) [3] |

| Fossil Fuel Use | 6% reduction [3] | Additional 16% reduction [3] |

| Water Use | 4% reduction [3] | Additional 21% reduction [3] |

| Land Use Efficiency | 2M acres of cropland avoided [3] | Additional gains possible |

The aggregate environmental impact of these improvements is substantial: current adoption levels have resulted in 30 million fewer pounds of herbicide applied, 100 million fewer gallons of fossil fuel consumed, and enough water saved to fill 750,000 Olympic-size swimming pools [3]. From a climate perspective, precision agriculture technologies currently contribute to avoiding approximately 10.1 million metric tons of CO2 emissions, with potential to avoid an additional 17.3 million metric tons through broader adoption [3].

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Technology Validation

VOC Sensor Deployment for Early Disease Detection

Objective: To validate the efficacy of volatile organic compound (VOC) sensors for early detection of plant diseases before visible symptoms appear.

Materials: WolfSens wearable electronic patches or portable colorimetric sensors [5], tomato plants (healthy and inoculated with Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus), controlled environment chambers, data logging system.

Methodology:

- Establish test and control groups with minimum 50 plants each

- Attach wearable sensors to underside of leaves in test group

- Inoculate test group with TSWV while maintaining control group under identical conditions

- Collect continuous VOC data from sensors at 6-hour intervals

- Record visual observations daily for symptom development

- Compare sensor data with visual symptom emergence timeline

- Validate detection accuracy through laboratory testing of plant tissue samples

Validation Metrics: Time between sensor detection and visual symptom appearance, detection accuracy rate, false positive rate [5]. In proof-of-concept testing, the portable WolfSens sensor detected pathogen Phytophthora infestans in tomato leaves with greater than 95% accuracy [5].

Spectral Soil Analysis Protocol

Objective: To develop and validate in-situ soil property measurement using spectral signature analysis.

Materials: Portable spectrometers, traditional soil sampling equipment, laboratory analysis resources, GPS units for geotagging.

Methodology:

- Collect geotagged soil samples from multiple field locations (minimum 20 sample points per 100 acres)

- Perform simultaneous spectral measurements at each sample point

- Conduct traditional laboratory analysis for soil properties (organic matter, pH, nutrient levels)

- Correlate spectral signatures with laboratory results using machine learning algorithms

- Develop predictive models for soil properties based on spectral data

- Validate model accuracy with separate test dataset

- Compare costs and time requirements between traditional and spectral methods

Validation Metrics: Correlation coefficient between predicted and measured properties, root mean square error of predictions, cost per sample analysis, time from sampling to results [6]. Traditional laboratory analysis can cost up to $60 per sample and take weeks for results, while spectral methods aim to provide real-time measurements at significantly lower cost [6].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Precision Agriculture Sensor Development

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| WolfSens Wearable Patches | Continuous, real-time detection of plant VOCs for early disease detection [5] | Electronic patches with VOC sensors; wireless data transmission; >95% detection accuracy [5] |

| Portable Colorimetric Sensors | Field-deployable plant disease detection using smartphone compatibility [5] | Handheld device with colorimetric paper strips; smartphone connectivity; rapid results |

| Multispectral Imaging Sensors | Crop health monitoring through non-visible wavelength detection [7] [2] | Capability to capture infrared, red-edge spectra; NDVI calculation; sub-10cm spatial resolution |

| Soil Electrical Conductivity Sensors | Mapping soil variability and moisture content [2] [6] | Direct contact measurement; real-time data logging; GPS synchronization |

| Hyperspectral Drone Systems | High-resolution field mapping for stress detection [7] [4] | 400-1000nm spectral range; <5cm spatial resolution; automated flight planning |

| Polarized Light Sensors | Accurate color capture overcoming sun glare [5] | Polarization filtering; algorithm-based color correction; field-deployable |

| Nanosensors | Targeted monitoring of soil moisture and nutrients [9] | Nano-scale components; real-time monitoring capability; minimal power requirements |

Implementation Workflow for Precision Agriculture Systems

The transition from uniformity to site-specific management follows a structured implementation process that integrates technologies across the agricultural production cycle.

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The future of precision agriculture points toward increasingly sophisticated sensor technologies and data integration platforms. Emerging research includes the development of handheld sensor technology for direct field measurement or integration with farm equipment for real-time analysis [6]. Nanotechnology is playing an increasingly important role, with nanocapsules facilitating targeted delivery of agrochemicals and nanosensors enabling real-time monitoring of soil moisture and nutrient levels [9]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning continues to advance, with systems becoming capable of predictive analytics for yield forecasting, disease outbreak prediction, and optimized resource allocation [7] [2]. The market for precision agriculture is projected to grow substantially, expected to reach USD 8,018.5 million by 2029, expanding at a compound annual growth rate of 15.4% [9]. This growth will be driven by continued technological innovation and increasing demand for sustainable agricultural practices that optimize resource utilization while maintaining productivity.

Variable Rate Application (VRA) is a core component of precision agriculture, enabling the targeted application of agricultural inputs—such as fertilizer, seed, and water—at variable rates across a field, rather than applying a uniform rate everywhere [10]. This approach moves beyond traditional blanket application methods by accounting for in-field variability in soil characteristics, nutrient levels, and crop needs [11]. The technology is a critical response to pressing global challenges, including the need to increase agricultural output to meet rising food demand, reduce production costs, and minimize the environmental impact of farming practices [10]. The global VRA technology market, valued at $2.02 billion in 2021, is projected to grow significantly, reflecting its increasing adoption and importance in modern agriculture [10].

VRA operates as the "responding" category within the precision agriculture framework, which also includes "guidance" and "recording" technologies [10]. Its implementation relies on a sophisticated integration of hardware and software, typically including an in-cab computer and software with a field zone application map, application equipment capable of changing rates during operation, and the Global Positioning System (GPS) for precise location tracking [11]. The fundamental aim is to apply the right amount of input, at the right place, and at the right time, thereby optimizing resource use, enhancing crop productivity, and improving sustainability [10].

Core Technological Principles of VRA

The implementation of Variable Rate Application is primarily achieved through two distinct technological approaches: map-based and sensor-based systems. Both methods enable precise input management but differ in their data sources and operational workflows.

Map-based VRA (also known as prescription map-based) relies on pre-defined application maps generated from historical data, soil sampling, yield maps, or aerial imagery [10] [12]. These maps, which delineate management zones within a field, are loaded into a controller on the application equipment. During operation, the GPS-guided system adjusts the application rate in real-time as the machinery moves from one zone to another, matching the prescribed rate for each specific area [10]. This system is characterized by high accuracy, with research showing that map-based systems for solid fertilizers operate with an overall accuracy ranging between 94% and 98%, depending on the actuation method employed [12].

Sensor-based VRA utilizes real-time sensors mounted on application equipment to analyze crop or soil conditions on the go [10]. These sensors measure properties such as plant chlorophyll levels (as an indicator of nitrogen status) or soil reflectance. The sensor data is instantly processed by an onboard algorithm, which then triggers a change in the application rate without human intervention [10]. This approach offers the significant benefit of responding to current conditions without any time lag between measurement and application, achieving an overall accuracy of roughly 96% [12].

Table 1: Comparison of Map-Based and Sensor-Based VRA Approaches

| Feature | Map-Based VRA | Sensor-Based VRA |

|---|---|---|

| Data Source | Pre-existing prescription maps from historical data, soil tests, yield maps [10] | Real-time sensor readings of plant or soil conditions [10] |

| Key Requirement | Accurate GPS and pre-planning to create management zones [11] | Robust, accurate sensors and real-time decision-making algorithms [12] |

| Primary Advantage | Ability to use multiple information sources for highly accurate planning; high overall accuracy (94-98%) [12] | Responds to current conditions with no time lag; avoids need for extensive pre-map creation [10] [12] |

| Key Limitation | Does not respond to real-time, in-season changes in crop status | Limited by the availability of simple and accurate sensors for all parameters [12] |

The effectiveness of both systems hinges on a complex control system. For solid fertilizers, this typically includes components such as a DC motor (hydraulic or electric), a controller (e.g., a programmable logic controller or PLC), a power source, and monitoring sensors (e.g., radar or optical sensors) to measure the actual output and provide feedback for system calibration and accuracy [12].

The Role of Advanced Sensors and Data Acquisition

Advanced sensor technologies form the bridge between the physical state of the field and the data-driven decisions executed by VRA systems. The proliferation of new sensing modalities provides researchers and farm managers with unprecedented insights into crop physiology and environmental conditions.

Sensor Types and Deployed Technologies

Modern agricultural sensing spans a wide technological spectrum:

- Optical Sensors: Devices like the SPAD-502 Plus chlorophyll meter and the Trimble GreenSeeker handheld crop sensor are foundational for non-destructive plant monitoring [13]. The SPAD meter provides a relative chlorophyll content index by measuring light absorption at red (650 nm) and near-infrared (940 nm) wavelengths, serving as a proxy for leaf nitrogen status [13]. The GreenSeeker calculates the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) based on reflectance in the red (656 nm) and near-infrared (774 nm) bands to assess plant biomass, photosynthetic capacity, and stress [13].

- Thermal Imaging Sensors: Cameras such as the FLIR T540 measure canopy temperature, which is closely associated with plant water status, stomatal conductance, and transpiration rates. A reduction in canopy temperature of 1.8–2.5 °C, as observed in optimized fertilization treatments, indicates enhanced stomatal regulation and water-use efficiency [13].

- Plant Flexible Sensors: This emerging class of sensors represents a significant advancement for real-time, non-invasive monitoring. Fabricated from conductive polymers (e.g., polypyrrole, PEDOT:PSS), carbon-based materials (e.g., graphene, carbon nanotubes), and biocompatible substrates (e.g., nanocellulose, silk fibroin), these sensors conform to plant surfaces [14]. Their mechanical compliance allows them to monitor physiological parameters like humidity, temperature, mechanical strain (growth), and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) without damaging plant tissues, enabling continuous, in-situ data collection [14].

Data Integration and Platform Architecture

The raw data from these diverse sensors is integrated and given context through agricultural data platforms. Initiatives like India's AgriStack, VISTAAR, and Agricultural Data Exchange (ADeX) exemplify this trend, creating centralized or federated repositories for soil tests, weather patterns, crop trends, and market data [15]. These platforms aim to break down data silos and facilitate the development of data-driven services for farmers and researchers.

For these platforms to be effective, a supportive ecosystem must be developed across four key dimensions [15]:

- Business Value: Emphasizing tangible benefits and building platforms around well-defined use cases.

- Technology: Establishing robust Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) with open APIs and interoperability standards (e.g., AgriJSON) to enable plug-and-play architecture.

- Legal: Implementing clear data protection frameworks based on informed consent and individual rights, aligned with standards like India's DPDP Act.

- Project Implementation: Ensuring strategic roll-out, continuous improvement, and dedicated maintenance of the platforms.

Commercial platforms, such as Syngenta's Cropwise Operations, demonstrate this integration in practice. They unify data from satellites, machinery, weather stations, and in-field sensors to provide tools for variable rate application support, yield prediction, and precision irrigation management [16].

Experimental Protocols for Sensor-Based Assessment

To illustrate the practical application of these technologies in a research context, the following is a detailed methodology from a recent study investigating fertilizer strategies in soybean using a multi-sensor approach [13].

Objective: To investigate the temporal effects of different fertilization strategies on the physiological, morphological, and biomass-related traits of soybean under controlled greenhouse conditions [13].

Experimental Design:

- Plant Material: Soybean cultivar 'Gapsoy-16' [13].

- Pot Experiment Design: The experiment used a randomized complete block design (RCBD) with 7 treatment levels and 4 replications each (total of 28 pots). Treatments included Control, Urea only, Zinc (Zn) only, Microbial inoculant only, Urea + Zn, Urea + Microbial, and Zn + Microbial [13].

- Timeline: The experiment was initiated on May 1, 2025, with sowing and completed on July 9, 2025. Measurements were taken at weekly intervals [13].

Sensor-Based Measurements and Protocol: All measurements were conducted consecutively between 13:00 and 15:00 to minimize diurnal variation [13].

SPAD (Chlorophyll Content):

- Instrument: SPAD-502 Plus (Konica Minolta).

- Procedure: Middle canopy leaves were placed into the device clamp. Four readings per replication were taken and averaged. The device provides a relative Chlorophyll Content Index (CCI) derived from light absorption at 650 nm and 940 nm [13].

NDVI (Canopy Vigor):

- Instrument: Trimble GreenSeeker Handheld Crop Sensor.

- Procedure: The sensor was positioned at a fixed distance of approximately 70 cm above the canopy of each pot. Four replicate measurements per treatment were taken and averaged. NDVI is calculated from reflectance at 656 nm (red) and 774 nm (near-infrared) [13].

Thermal Imaging (Canopy Temperature):

- Instrument: FLIR T540 thermal infrared camera.

- Procedure: Images were acquired with the camera positioned 3–4 m from the plants, with emissivity set to 0.95. A black curtain was used as a background to eliminate reflections. Canopy temperature was extracted and analyzed from the images [13].

Plant Height (Morphological Trait):

- Instrument: Standard ruler.

- Procedure: The distance from the soil surface to the highest point of the main stem was recorded [13].

Post-Harvest Biomass Analysis: After the sensor-based monitoring period, plants were harvested, and fresh biomass was measured. Strong positive correlations (r = 0.71–0.84) were found between the sensor parameters (SPAD/NDVI) and post-harvest biomass, validating the reliability of the non-destructive sensor measurements for predicting yield-related traits [13].

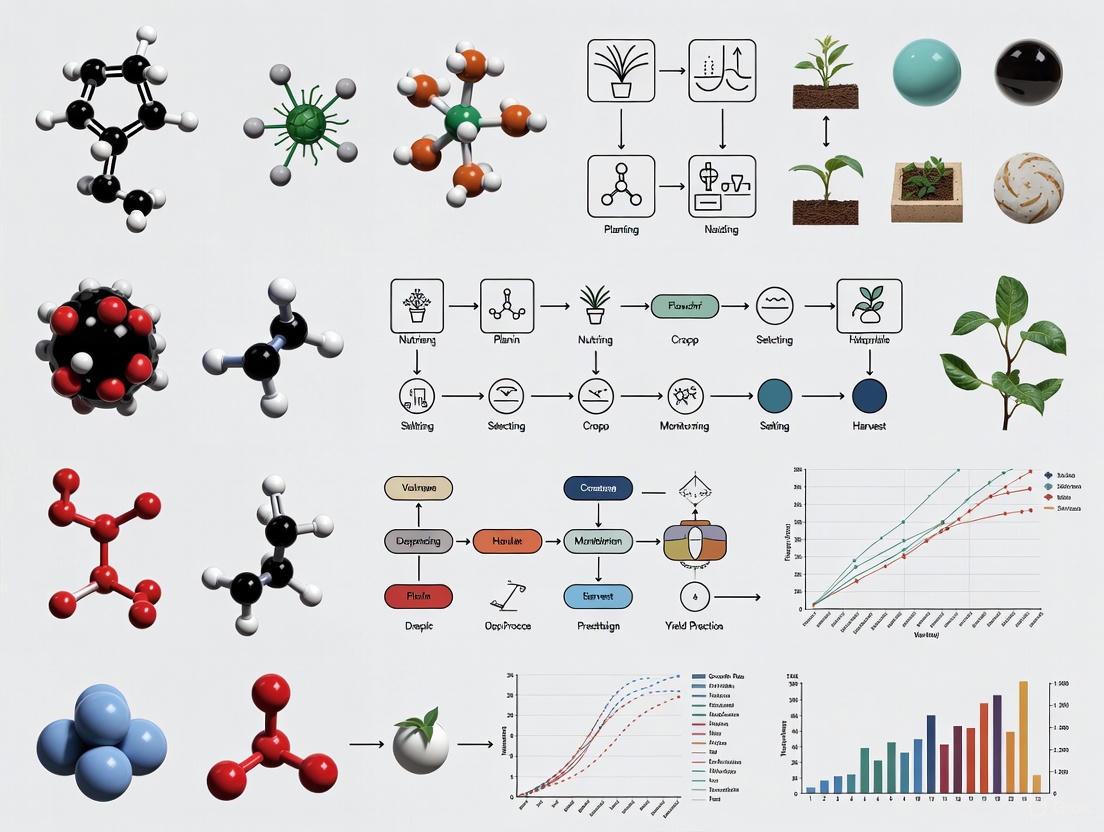

The following workflow diagram summarizes this experimental protocol:

Data-Driven Decision-Making: From Data to Action

The ultimate value of sensor data and VRA is realized in the decision-making feedback loop that translates information into optimized agricultural actions. This process creates a cycle of continuous improvement, as illustrated below:

The process begins with Data Acquisition from multiple sources, including soil sensors, optical plant sensors, drones, and satellite imagery [13] [16] [17]. This data is then fed into a central platform for Integration and Analysis [15] [16]. Here, powerful analytics and AI models interpret the data to identify patterns and problems, such as nutrient deficiencies or water stress. These insights inform the Generation of a Decision, which takes the form of a prescription map for map-based VRA or a real-time algorithm for sensor-based VRA [10] [12]. This decision is executed by Variable Rate Application machinery, which applies inputs precisely where needed [11] [10]. Finally, the Outcome is Assessed through yield monitoring, sustainability metrics, and return on investment calculations, completing the loop and providing data to refine the next cycle of decisions [13] [16].

The quantitative impact of this data-driven approach is significant. Studies show that AI-enabled models can improve yield prediction by 20%, while UAVs can reduce water and fertilizer use by up to 96% and 40%, respectively [17]. Furthermore, sensor-based thresholds, such as a SPAD value of ~35 and an NDVI of ~0.60 identified in soybean studies, provide concrete, actionable benchmarks for fertilization decisions and automation [13].

Table 2: Quantitative Impacts of Data-Driven Smart Farming Technologies

| Technology | Measured Impact | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| AI-Enabled Models | Improved yield prediction by 20% [17] | Crop yield forecasting |

| Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) | Reduced water use by up to 96% and fertilizer use by up to 40% [17] | Precision application of inputs |

| IoT-based Smart Irrigation | Enhanced crop productivity by 25% [17] | Water resource management |

| Sensor-based Biomass Prediction | Strong positive correlation with post-harvest biomass (r = 0.71-0.84) [13] | Non-destructive yield estimation |

| Combined Fertilizer Treatments | Increased fresh biomass by 28% compared to control [13] | Soybean nutrient management |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers designing experiments in sensor-driven agriculture and VRA, a standard toolkit comprises several key components.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Reagents for VRA and Sensor Experiments

| Item | Function / Relevance | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Chlorophyll Meter (SPAD) | Provides a rapid, non-destructive proxy for leaf nitrogen status and photosynthetic capacity [13] | SPAD-502 Plus (Konica Minolta) [13] |

| Multispectral Sensor (NDVI) | Assesses canopy vigor, biomass, and photosynthetic activity by measuring red and near-infrared reflectance [13] | Trimble GreenSeeker Handheld Sensor [13] |

| Thermal Imaging Camera | Monitors canopy temperature as an indicator of plant water status and stomatal conductance [13] | FLIR T540 [13] |

| Plant Flexible Sensors | Enable non-invasive, real-time monitoring of plant physiological signals (e.g., strain, humidity, VOCs) [14] | Sensors based on PEDOT:PSS, graphene, or nanocellulose [14] |

| Conductive Polymers | Used as sensing materials in flexible sensors for their electrical conductivity and flexibility [14] | Polypyrrole (PPy), Polyaniline (PANI), PEDOT:PSS [14] |

| Carbon-Based Nanomaterials | Provide high conductivity and sensitivity in flexible sensor fabrication [14] | Graphene, Carbon Nanotubes [14] |

| Biocompatible Substrates | Serve as flexible, often biodegradable, support structures for sensors to ensure plant compatibility [14] | Nanocellulose, Silk Fibroin [14] |

| Microbial Inoculants | Used in treatment experiments to enhance nutrient availability and plant growth [13] | Clonostachys rosea st1140 strain [13] |

Variable Rate Application, powered by an ever-evolving suite of advanced sensors and robust data platforms, represents a foundational shift in agricultural management. The core principles outlined—the integration of map-based and sensor-based systems, the utilization of non-invasive sensing technologies, and the closure of the data-driven decision loop—provide a framework for achieving unprecedented levels of efficiency and sustainability in crop production. For researchers, the path forward involves continued refinement of sensor technologies, particularly in durability, cost-effectiveness, and seamless integration into broader agricultural data ecosystems. By embracing these principles and tools, the scientific community can accelerate the development of intelligent, responsive agricultural systems capable of meeting the food security challenges of the future.

The foundation of modern precision agriculture is a sophisticated sensor ecosystem that transforms physical farming parameters into actionable digital insights. This ecosystem represents a fundamental retooling of traditional agricultural methods through the application of Internet of Things (IoT) technologies, creating a network of interconnected devices that monitor and manage crop environments with unprecedented precision [18]. At its core, this technological revolution addresses critical global challenges including growing food demand, environmental sustainability, and resource scarcity by making agricultural operations data-driven and measurable [18] [19].

The agricultural IoT ecosystem functions through a tightly integrated stack of technologies. Low-power sensors deployed throughout farming operations collect granular data on soil, crops, and environmental conditions [18]. This data is transmitted via specialized connectivity protocols to platforms where edge and cloud computing systems process and analyze the information [18]. The resulting intelligence enables automated control systems and provides farmers with actionable insights through intuitive dashboards, completing the cycle from physical monitoring to digital management [19]. This technological framework has transformed farms from uniform production zones into differentiated micro-environments where each plant's specific needs can be identified and addressed [18].

Core Sensor Technologies for Crop Research

Soil and Root Zone Monitoring Systems

Soil sensors form the foundational layer of the agricultural IoT ecosystem, providing critical data on the rhizosphere environment that directly influences crop health and productivity. Soil moisture sensors are among the most widely deployed technologies, measuring volumetric water content to guide irrigation scheduling with reported water use reductions of 30-50% [18] [19]. These sensors are complemented by soil nutrient and pH sensors that measure key soil properties including nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium levels, as well as soil acidity/alkalinity [18] [20]. This nutrient data enables precise fertilization strategies that reduce input costs and minimize environmental impact from runoff [20].

Advanced research applications now incorporate root architecture phenotyping technologies that employ functional-structural modeling to evaluate quantitative metrics of root systems [21]. These systems measure critical phenes (elemental phenotypic units) including root number, diameter, and lateral root branching density—parameters that provide more reliable indicators of plant status than aggregate metrics alone [21]. The stability and reliability of these phenes make them particularly valuable for breeding programs and management strategy optimization, as they are not affected by imaging method or plane and offer direct insight into plant physiological status [21].

Plant Health and Stress Detection Technologies

Plant-focused sensors represent the most technologically advanced layer of the agricultural IoT ecosystem, enabling early detection of stress long before visible symptoms appear. Research at the North Carolina Plant Sciences Initiative has developed innovative WolfSens technology that includes both wearable electronic patches and portable sensors for detecting plant volatiles [5]. These "wearable olfactory sensing" devices detect volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that plants emit in response to viral and fungal infections, abiotic stresses, and other health challenges [5].

The WolfSens wearable patch attaches to the underside of plant leaves and provides continuous, real-time detection of health status [5]. In experimental trials, this patch detected viral infection in tomatoes more than a week before visual symptoms of Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus appeared [5]. The complementary portable WolfSens sensor uses colorimetric paper strips that change color based on VOC profiles and connects to smartphones for field deployment [5]. This system demonstrated greater than 95% accuracy in detecting Phytophthora infestans in tomato leaves, distinguishing it from other pathogens with similar symptoms [5].

Advanced optical and light sensors further enhance plant monitoring capabilities. Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR) sensors measure the light spectrum available for photosynthesis, enabling optimization of light conditions for maximum photosynthetic efficiency [18] [20]. To address challenges with color distortion in bright sunlight, researchers have developed polarized light sensors that use software algorithms to accurately capture leaf color regardless of glare [5]. This technology adapts principles from biomedical imaging, where polarized light reveals tissue structure, applying them to agricultural contexts to improve stress detection accuracy [5].

Table 1: Advanced Soil and Plant Sensor Technologies

| Sensor Category | Specific Metrics Measured | Research Applications | Detection Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil Moisture Sensors | Volumetric water content, soil water potential | Irrigation optimization, drought stress studies | Continuous moisture levels at various depths |

| Soil Nutrient Sensors | NPK levels, pH, organic matter components | Precision fertilization, soil health mapping | Macronutrient deficiencies, soil acidity/alkalinity |

| Root Architecture Sensors | Root number, diameter, branching density, growth angle | Phenotyping, breeding programs, stress response | Structural adaptations to soil conditions |

| Plant VOC Sensors | Volatile organic compound profiles | Early disease detection, abiotic stress response | Viral/fungal infections >1 week before visual symptoms |

| Optical Sensors | PAR, leaf color, multispectral signatures | Photosynthetic efficiency, nutrient status | Chlorophyll content, nutrient deficiencies |

Environmental and Climatic Monitoring

Microenvironment monitoring completes the sensor ecosystem by quantifying the atmospheric conditions that influence crop growth and disease pressure. Weather and climate sensors track temperature, humidity, wind speed, precipitation, and atmospheric pressure at field level, enabling highly localized forecasting and management decisions [18] [20]. These sensors allow farmers to anticipate changing conditions and respond proactively—for instance, withholding irrigation when rainfall is predicted or activating frost protection systems before temperatures reach critical thresholds [18].

Advanced research operations deploy CO₂ and air quality sensors that monitor gas concentrations and pollutants in the crop canopy [20]. In controlled environments, these sensors enable precise CO₂ enrichment strategies to maximize photosynthetic rates [20]. Water quality sensors monitor irrigation water for pH, salinity, and contaminants, preventing soil degradation from poor quality water applications [20]. Together, these environmental sensors provide the contextual data needed to interpret plant and soil sensor readings accurately and implement appropriate management responses.

Connectivity Architectures and Data Transmission

Low-Power Wide-Area Networks (LP-WAN)

The agricultural IoT ecosystem relies on specialized connectivity solutions designed to overcome the challenges of rural deployments, including limited power infrastructure and expansive coverage areas. Low-Power Wide-Area Network (LP-WAN) technologies have emerged as the cornerstone of agricultural connectivity, with LoRaWAN and Narrowband-IoT (NB-IoT) being the most widely adopted protocols [18]. These networks are specifically engineered for IoT devices that need to transmit small packets of data over long distances while consuming minimal power [18]. A typical LP-WAN device can operate for years on battery power while transmitting data from distances up to 20km from the network gateway, eliminating the need for frequent maintenance in remote field locations [18].

The economic viability of large-scale sensor deployment hinges on these connectivity solutions. LP-WAN technologies have dramatically reduced both sensor hardware costs and connectivity expenses, making precision agriculture accessible to small- and medium-sized farms [18]. This democratization of technology is essential for widespread adoption, as smaller operations constitute significant proportions of global food production [18]. The combination of low cost and low maintenance makes it economically feasible to deploy hundreds or even thousands of sensors across farming operations, creating dense meshes of real-time data collection [18].

Edge and Cloud Computing Infrastructure

The agricultural IoT ecosystem employs a distributed computing architecture that balances processing between edge devices and cloud platforms to optimize responsiveness and analytical depth [18]. Edge computing processes data as close to the source as possible—on gateways installed in farm structures, tractor onboard computers, or even the sensors themselves [18]. This approach enables low-latency, real-time responses essential for automated applications such as driverless tractors, crop-dusting drones, and smart irrigation systems [18]. Edge computing also serves as an intelligent filter, analyzing data streams locally and transmitting only significant events or summaries to the cloud, dramatically reducing network traffic and connectivity costs [18].

Cloud computing complements edge processing by providing massive data storage capacity and sophisticated analytical capabilities [18]. Cloud platforms host powerful AI and machine learning algorithms that compare real-time data with historical records and cross-referenced information from other farms or government resources [18]. This large-scale analysis identifies patterns, predicts crop yields with increasing accuracy, models disease outbreaks, and develops long-term optimization strategies [18]. Farmers access these insights through unified dashboards on tablets or smartphones, providing comprehensive operational overviews from anywhere in the world [18].

The combination of edge and cloud computing creates a self-improving feedback loop that enhances system intelligence over time [18]. Edge devices collect and pre-process field data, which is curated and sent to the cloud for aggregation with diverse other sources [18]. The cloud's AI platforms analyze these massive datasets to refine predictive models, with improvements benefiting every participant in the network [18]. This collective intelligence represents the digital evolution of traditional farming knowledge sharing, accelerating improvement through democratized data access [18].

Diagram 1: Agricultural IoT data architecture showing the flow from field sensors to actionable insights through edge and cloud computing layers.

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Methodology for Plant VOC Sensing

The detection of plant volatiles for early disease diagnosis represents one of the most promising applications of advanced sensor technology in crop research. The WolfSens experimental protocol developed at NC State provides a validated methodology for VOC-based pathogen detection [5]. The research team employed two complementary sensor approaches: a wearable electronic patch for continuous monitoring and a portable colorimetric sensor for spot measurements [5].

For the wearable patch deployment, researchers attached the sensors to the underside of tomato plant leaves in greenhouse conditions [5]. The patches remained in place for continuous monitoring, with data transmitted wirelessly to a base station [5]. Experimental plants were inoculated with Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus, while control groups remained uncontaminated [5]. The sensors successfully detected distinctive VOC profiles associated with viral infection more than one week before visual symptoms appeared [5].

The portable sensor protocol involved collecting leaf samples from multiple locations within the greenhouse [5]. Researchers placed leaves in sealed containers with the colorimetric paper strips for a standardized exposure period [5]. The strips were then photographed using a smartphone-connected handheld device, with specialized software analyzing color changes to identify specific pathogens [5]. In validation testing, this method detected and distinguished tomato late blight from other fungal pathogens with similar symptoms, achieving greater than 95% accuracy for Phytophthora infestans detection [5].

Sensor Validation and Data Integrity Framework

Ensuring data accuracy and reliability is paramount in agricultural sensor deployment. Research institutions have established rigorous validation protocols that combine sensor readings with traditional measurement techniques. The North Carolina Plant Sciences Initiative emphasizes interdisciplinary verification, bringing together expertise from chemical engineering, electrical engineering, data science, and plant pathology to validate sensor performance [5].

For soil sensor validation, researchers typically employ destructive sampling at sensor locations to provide laboratory-based verification of sensor readings [22]. This involves collecting soil cores adjacent to moisture and nutrient sensors for standard laboratory analysis using established methods like gravimetric water content measurement and chemical extraction for nutrient quantification [22]. The root architecture phenotyping community has established standards for minimizing measurement error, particularly for critical phenes like root growth angle that are susceptible to distortion in 2D projection methods [21].

Advanced optical sensor validation incorporates reference standards and control environments to ensure accurate color perception regardless of lighting conditions [5]. The polarization software developed by NC State researchers underwent rigorous testing using color standards under varying light intensities and angles to verify measurement accuracy [5]. This validation confirmed that the algorithm could accurately estimate true leaf color based on both perceived color and the polarization of the darkest wavelength in the image [5].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Agricultural IoT Systems

| Technology Category | Performance Metrics | Research-Grade Specifications | Impact on Agricultural Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LP-WAN Connectivity | Range: Up to 20km\r\nBattery Life: 2-10 years\r\nData Rate: 0.3-50 kbps | LoRaWAN, NB-IoT, Sigfox protocols\r\nBi-directional communication\r\nEnd-to-end encryption | Enables monitoring of remote fields\r\nReduces maintenance requirements | |

| Soil Moisture Sensing | Accuracy: ±3% VWC\r\nResolution: 0.1% VWC\r\nResponse Time: <2 seconds | Calibrated for soil types\r\nTemperature compensated\r | 30-50% water use reduction\r\nPrevents over-/under-watering stress | |

| Disease Detection Sensors | Early Detection: 7-10 days before symptoms\r\nAccuracy: >95% for specific pathogens\r\nSpecificity: Distinguishes between pathogens | VOC profiling\r | Enables targeted interventions\r | Reduces pesticide use through precision application |

| Plant Health Monitoring | PAR Measurement: 400-700nm spectrum\r | Polarization compensation for glare reduction\r | 15-20% yield improvement through optimized growing conditions\r | Reduces resource waste |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Sensor-Based Crop Research

Implementing a comprehensive agricultural sensor research program requires specialized materials and reagents tailored to the unique challenges of field deployment and data validation. The following toolkit represents essential components for establishing a robust sensor research infrastructure:

Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) Collection Systems: Specialized adsorbent tubes and chambers for capturing plant volatiles, with thermal desorption equipment for laboratory analysis. These systems provide the ground truth data required for calibrating and validating electronic nose sensors like the WolfSens platform [5].

Reference Soil Analysis Kits: Laboratory-grade equipment for soil nutrient extraction and quantification, including colorimetric assays for nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. These kits enable validation of in-situ soil sensor readings and establish calibration curves for specific soil types [22].

Standardized Color Reference Cards: Calibrated color targets with known reflectance values across the visible and near-infrared spectrum. These references are essential for validating optical sensors and ensuring consistent color perception across varying light conditions [5].

Root Architecture Imaging Setup: Rhizotron containers, high-resolution scanning equipment, and specialized software (such as RootSnap! or DIRT) for quantifying root system architecture parameters. These tools provide validation data for comparing sensor-based root monitoring approaches [21].

Wireless Network Testing Equipment: Spectrum analyzers, packet sniffers, and signal strength measurement tools for characterizing LP-WAN performance in agricultural environments. This equipment helps optimize gateway placement and network configuration for reliable data transmission [18].

Environmental Chamber Systems: Controlled growth environments with precise regulation of temperature, humidity, and light conditions. These chambers enable controlled stress induction experiments for developing sensor response models under known environmental conditions [5].

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The agricultural sensor ecosystem continues to evolve toward greater integration, intelligence, and accessibility. Nanobiotechnology represents the next frontier, with sensors implementing optical, wireless, or electrical signals to monitor plant signaling molecules at unprecedented resolution [22]. These technologies include genetically encoded sensors that can be transported through nanomaterial facilitators, potentially enabling real-time monitoring of physiological processes within plant tissues [22].

Plant wearables are emerging as a distinct category of monitoring technology, moving beyond temporary attachments to integrated systems that continuously track plant physiology [22]. These devices face unique engineering challenges including biocompatibility, energy autonomy, and mechanical stability during plant growth [22]. Simultaneously, multimodal sensor fusion approaches are combining data from soil sensors, plant wearables, drone imagery, and satellite observations to create comprehensive digital twins of farming operations [19].

The research community is increasingly focused on data standardization and interoperability to maximize the value of sensor networks. Initiatives like the CROPGRIDS dataset provide global geo-referenced information on crop distribution, creating frameworks for contextualizing sensor data within broader agricultural patterns [23]. As these technologies mature, the agricultural sensor ecosystem will continue to transform farming from a resource-intensive practice to a knowledge-intensive industry capable of meeting global food demands while minimizing environmental impact [18] [19].

Advanced sensor technologies are fundamentally transforming crop planting research, enabling a shift from traditional observation to data-driven, precise experimentation. This evolution is critical for addressing global challenges in food security and sustainable agricultural development [24]. Modern sensor systems provide researchers with the tools to capture high-resolution, real-time data on plant physiology, soil dynamics, and environmental interactions, generating unprecedented datasets for analysis [25] [26]. This technical guide details the key sensor categories—from in-ground analyzers to aerial surveillance platforms—that form the technological backbone of contemporary crop research, framing them within the context of experimental application for scientists and research professionals.

The transition to Agriculture 4.0 and the emerging paradigm of Agriculture 5.0 underscore a broader industrial shift towards cyber-physical systems and a human-centric, sustainable approach to innovation [26]. In this framework, sensors act as the primary data acquisition layer, or the "senses," of smart agricultural systems [24]. Their integration with Internet of Things (IoT) platforms, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning (ML) enables not only real-time monitoring but also predictive analytics and automated control systems, thereby creating a closed-loop environment for precise experimental intervention and observation [26].

Core Sensor Categories and Their Technologies

The sensor ecosystem in precision agriculture can be categorized by its deployment domain and technological approach. The following sections and accompanying table provide a comparative overview of these core categories.

Table 1: Key Sensor Categories for Crop Research

| Sensor Category | Monitoring Targets | Key Technologies | Spatial & Temporal Resolution | Primary Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-Ground & Wearable Plant Sensors [24] [25] [22] | Soil nitrate, moisture, temperature [27]; Plant biochemicals (H₂O₂, hormones), microclimate, physiological status (water content, stem diameter) [24] [25] | Printed electrochemistry [27]; Flexible electronics; Micro-nano technology (e.g., Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes) [24]; Nanobiotechnology [22] | Very High (Point-based, continuous) | Real-time plant-soil interaction studies; Mechanistic study of biotic/abiotic stress responses; Nutrient uptake dynamics [24] [27] [25] |

| Aerial Surveillance Platforms [28] [29] | Canopy temperature, chlorophyll levels, plant health/vigor, stand count, biomass, 3D canopy structure [28] [29] | UAVs (drones & tethered systems) with RGB, multispectral, hyperspectral, thermal, and LiDAR sensors [30] [28] [29] | High to Medium (Coverage of large plots, flyover frequency) | High-throughput phenotyping [28]; Early stress detection (before visual symptoms) [29]; Yield prediction; Large-scale treatment efficacy trials [28] |

| Proximal & Remote Sensing [25] [31] | Spectral reflectance, canopy structure, soil properties | Ground-based/vehicle-mounted spectral imaging; Satellite remote sensing [25] | Variable (Point-based to landscape-scale) | Soil mapping; Plant health assessment; Historical trend analysis [25] [31] |

In-Ground and Wearable Plant Sensors

This category encompasses sensors that are either deployed directly in the soil or attached to plant surfaces, providing high-resolution data on the immediate plant and rhizosphere environment.

In-Ground Soil Sensors

In-ground sensors provide direct, continuous measurement of critical soil parameters. A significant advancement is the development of printed electrochemical sensors for soil nitrate monitoring, overcoming traditional challenges of cost, labor, and lack of real-time data [27]. These sensors are fabricated via an inkjet printing process, creating a low-cost, potentiometric thin-film sensor. A key innovation is the application of a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) layer, which acts as a protective membrane. This hydrophilic material with 400-nanometer pores allows nitrate-laden water to be absorbed into the sensor while blocking coarse soil particles that cause interference and physical damage [27]. Researchers are integrating these nitrate sensors with moisture and temperature sensors into a multifunctional "sensing sticker" mounted on a flexible plastic substrate. Multiple stickers attached to a rod at different depths enable profiling of nitrate leaching and movement through the soil profile [27].

Wearable and Flexible Plant Sensors

Moving from the soil to the plant itself, flexible wearable sensors represent a frontier in plant phenotyping. Unlike rigid sensors that can damage plant tissues and induce biological rejection, flexible sensors are made from compliant materials with excellent flexibility, ductility, and biocompatibility [25]. These devices conform to irregular plant surfaces, enabling in-situ, real-time, and continuous monitoring of physiological information with minimal invasiveness [24]. The technology is driven by advances in flexible electronics and micro-nano sensing technology [24] [25]. For example, researchers have developed a nanosensor using single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) for the real-time detection of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), a signaling molecule released during plant wounding. This sensor demonstrates high sensitivity (approximately 8 nm ppm⁻¹) and can be integrated with portable electronic devices for field deployment [24]. These sensors provide a direct window into plant signaling and metabolic processes.

Aerial and Proximal Surveillance Platforms

Aerial surveillance platforms provide a macro-scale perspective, essential for high-throughput phenotyping and the management of large experimental plots.

Drone-Based Surveillance

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), or drones, equipped with advanced imaging sensors, are powerful tools for capturing high-resolution, real-time crop data [29]. Standard payloads include:

- Multispectral/Hyperspectral Sensors: Capture data beyond the visible spectrum, enabling the calculation of vegetation indices like the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) for health assessment and the Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) for water stress [28] [29].

- Thermal Sensors: Map canopy temperature, which is a proxy for plant water stress and stomatal conductance [29].

- High-Resolution RGB Sensors: Used for detailed canopy analysis, including measuring 2D canopy cover and using structure-from-motion techniques to generate 3D plant height and biomass models [28].

A key operational challenge for conventional drones is limited flight time due to battery constraints. An emerging solution is the use of tethered unmanned aerial vehicles, which draw continuous power from a ground station, allowing them to hover indefinitely and provide truly persistent, real-time surveillance and data streaming, even in challenging wind conditions [30].

Proximal Sensing and Data Integration

Proximal sensing, involving ground-based or vehicle-mounted systems, bridges the gap between in-ground and aerial data. Technologies such as optical imaging, chlorophyll fluorescence imaging, and 3D imaging are used for detailed phenotypic characterization [25]. The integration of data from in-ground, wearable, and aerial sensors through IoT platforms creates a holistic view of the crop environment. This sensor network allows for remote monitoring, data analysis via AI/ML, and automated control systems, enabling predictive analytics for challenges like disease outbreaks and yield forecasting [26].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Deployment and Data Collection with Multifunctional Soil Sensing Stickers

This protocol is adapted from research on printed nitrate sensors [27].

1. Sensor Fabrication and Preparation:

- Materials: Inkjet printer with conductive and reference electrode inks; flexible plastic substrate (e.g., polyimide); PVDF membrane; adhesives; moisture and temperature sensors.

- Fabrication: Fabricate the potentiometric nitrate sensor via inkjet printing on the substrate. Deposit the PVDF layer over the sensor electrode to form a protective, hydrophilic membrane. Integrate the nitrate sensor with commercial moisture and temperature sensors onto the same substrate to create a multifunctional "sensing sticker."

2. Field Calibration and Deployment:

- Calibration: Calibrate sensors in standard nitrate solutions before deployment to establish a calibration curve.

- Experimental Setup: Attach multiple sensing stickers to a rigid rod at predetermined depths (e.g., 10cm, 25cm, 40cm). Bury the rod vertically in the experimental plot, ensuring good soil-sensor contact.

- Replication: Deploy multiple sensor rods across different treatment blocks and control plots to ensure statistical robustness.

3. Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Data Logging: Connect sensors to a wireless data logger to record nitrate, moisture, and temperature measurements continuously at set intervals (e.g., every 15 minutes).

- Data Processing: Convert sensor electrical signals to nitrate concentrations using the pre-established calibration curve. Synchronize data with irrigation and fertilization events.

- Analysis: Analyze the multi-depth data to quantify nitrate leaching dynamics and temporal trends in nutrient availability.

Protocol: Crop Health and Stress Assessment Using UAV-Based Multispectral Imaging

This protocol is based on applications of drone-based analytics for crop research [28] [29].

1. Mission Planning and Pre-flight:

- Materials: UAV platform; multispectral sensor (e.g., Sentera Double 4K NDVI); GPS; mission planning software (e.g., for autonomous flight).

- Site Selection & Planning: Define the experimental plot boundaries. Program a autonomous flight path with sufficient forward and side overlap (e.g., 80%/70%) to ensure complete coverage and enable 3D model generation. Schedule flights for consistent solar noon conditions to minimize shadow effects.

2. In-Situ Data Collection and Flight Operation:

- Ground Truthing: Concurrent with the flight, collect in-situ validation data. This includes SPAD meter readings for leaf chlorophyll, leaf samples for nitrogen analysis, and visual assessments of plant health and stress symptoms.

- Flight Execution: Execute the autonomous flight. The multispectral sensor should capture data in relevant bands (e.g., red, green, red-edge, near-infrared).

3. Data Processing and Analysis:

- Image Processing: Use specialized software to stitch images into an orthomosaic and calculate vegetation indices (e.g., NDVI for health, NDWI for water stress).

- Statistical Analysis: Correlate the derived vegetation indices with the ground-truthed data using regression models. Use machine learning algorithms to classify areas of stress or predict yield based on the spectral data.

- Visualization: Generate spatial maps of crop health and stress to visually identify patterns and treatment effects across the experimental plots.

Visualization Diagrams

Sensor Technology Ecosystem

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected ecosystem of advanced sensor technologies in crop research, from data acquisition to application.

Integrated Monitoring Workflow

This diagram outlines the specific workflow for an integrated sensing experiment, from sensor deployment to data-driven decision-making.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Advanced Crop Sensing

| Item | Function/Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (SWNTs) [24] | Used as a core nanomaterial in nanosensors for detecting specific plant signaling molecules (e.g., hydrogen peroxide) due to their high sensitivity and ability to interface with portable electronics. |

| Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) Membrane [27] | A key material for protecting printed electrochemical soil sensors. Its nanoporous structure filters out soil particles while allowing nitrate-laden water to reach the sensor, enabling accurate operation in harsh soil environments. |

| Flexible Substrate Materials (e.g., Polyimide) [25] | Serve as the base for flexible and wearable plant sensors. Their mechanical properties, such as flexibility and ductility, allow for conformal attachment to plant organs without causing damage, enabling long-term monitoring. |

| Multispectral/Hyperspectral Sensors [28] [29] | Drone-mounted sensors that capture data at specific wavelengths. Used to calculate vegetation indices (e.g., NDVI, NDWI) for non-destructive assessment of plant health, water stress, and nutrient status at scale. |

| Potentiometric Sensor Inks [27] | Specialized conductive inks used in inkjet printing to fabricate the working and reference electrodes of electrochemical sensors, such as those for soil nitrate detection. |

| Calibration Standard Solutions [27] | Solutions with known analyte concentrations (e.g., nitrate) used to calibrate sensors before deployment, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the quantitative data collected. |

The integration of in-ground, wearable, and aerial sensor categories provides a multi-scale observational framework that is revolutionizing crop planting research. The synergy between these technologies allows scientists to correlate macro-scale canopy phenomena with micro-scale physiological and soil processes, enabling a systems-level understanding of crop performance [24] [28]. This comprehensive data is foundational for developing predictive models and intelligent management systems.

Future directions in this field are poised to leverage further advancements in nanotechnology, AI, and IoT [24] [26] [22]. Key trends include the development of multimodal sensors that capture multiple parameters simultaneously, the creation of self-powered sensors using energy harvesting, and the deepening of a collaborative human-machine intelligence framework as part of the Agriculture 5.0 paradigm [25] [26]. For researchers, mastering these sensor technologies and their integrated application is no longer a niche specialty but a core competency for driving innovation in plant science and sustainable agronomy.

The foundation of contemporary agricultural research is being redefined by the integration of advanced smart sensor technologies, which provide unprecedented capabilities for monitoring crop physiological status and environmental conditions in real time. These technologies represent a fundamental shift from traditional farming practices to data-driven agriculture, where precise measurements inform resource management decisions. For researchers and scientists focused on crop development, smart sensors offer a powerful toolkit for quantifying plant responses to environmental stressors, nutrient availability, and pathological challenges at temporal and spatial scales previously unattainable [32]. This technological transformation is critical for addressing the intersecting challenges of global food security, climate change, and resource scarcity.

The core value proposition of these technologies lies in their ability to generate high-resolution datasets that illuminate the complex interactions between crop genotypes and their growing environments. Where traditional methods relied on visual assessment and destructive sampling, modern sensor platforms enable continuous, non-invasive monitoring of plant systems. This capability is particularly valuable for tracking dynamic physiological processes and detecting stress responses during critical growth stages, providing researchers with insights necessary for developing more resilient and efficient crop varieties [5]. The integration of these sensors into structured research protocols represents a significant advancement in experimental methodology for crop science.

Sensor Technology Categories and Technical Specifications

Smart sensor systems for agricultural research encompass a diverse array of technologies, each designed to capture specific phenotypic, environmental, or pathological data points. These systems can be broadly categorized based on their sensing modalities, target analytes, and implementation frameworks. Understanding the technical specifications and operating principles of each category is essential for proper experimental design and data interpretation in crop research applications.

Table: Research-Grade Smart Sensor Categories and Specifications

| Sensor Category | Measured Parameters | Detection Mechanism | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil Sensor Arrays | Moisture content, NPK levels, pH, temperature, electrical conductivity | Electrochemical sensing, capacitance, resistivity | Nutrient uptake studies, irrigation optimization, root zone dynamics |

| Plant Wearable Sensors | Volatile organic compounds (VOCs), sap flow, stem diameter, leaf wetness | Electrochemical detection, strain gauges, microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) | Early disease detection, water stress monitoring, growth kinetics |

| Optical & Spectroscopic Sensors | Reflectance spectra (VIS, NIR, MIR), chlorophyll content, canopy temperature | Multispectral/hyperspectral imaging, thermography, fluorometry | Photosynthetic efficiency, biomass accumulation, nutrient status assessment |

| Environmental Monitors | Air temperature, relative humidity, solar radiation, atmospheric pressure, rainfall | Solid-state MEMS, piezoelectric, capacitive sensing | Microclimate characterization, growth chamber monitoring, field environmental controls |

| Yield Monitoring Systems | Grain mass flow, moisture content, harvest quantity, spatial coordinates | Impact force measurement, capacitive moisture sensing, GPS mapping | Yield component analysis, phenotypic screening, treatment effect quantification |

The technological sophistication of these research tools enables unprecedented resolution in measuring plant responses. For instance, WolfSens wearable patches developed at NC State represent a significant advancement in plant pathology research, detecting volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted during early infection stages—more than a week before visible symptoms of Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus manifest [5]. Similarly, advanced yield monitoring systems provide quantitative harvest data with precise geolocation, enabling researchers to correlate seasonal management practices and environmental conditions with final productivity at fine spatial scales [33].

Table: Performance Metrics of Advanced Research Sensors

| Sensor Technology | Accuracy/Resolution | Response Time | Research Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Piezoelectric Event Detection Sensors | >97.5% recognition accuracy for vibration events | <6 seconds for event detection | Peer-reviewed validation for knock, shake, and heat event discrimination [34] |

| Soil Nutrient Sensors | NPK detection at ppm concentrations, pH ±0.1 units | Continuous monitoring with minute-scale temporal resolution | Field correlation with laboratory soil analysis (R² > 0.85) [32] |

| VOC Detection Patches | >95% accuracy for Phytophthora infestans detection | Real-time continuous monitoring | Pre-symptomatic detection 7-10 days before visual symptoms [5] |

| Multispectral Imaging Sensors | Sub-centimeter spatial resolution, narrow bandwidth (10nm) | Daily monitoring capabilities via satellite platforms | Strong correlation with vegetation indices (NDVI, NDRE) and yield (R² > 0.75) [33] |

| Yield Monitor Systems | Mass flow measurement ±1-2%, moisture content ±0.5% | Real-time harvesting data with GPS synchronization | Industry standard for precision agriculture research with multi-year datasets [35] |

Experimental Protocols for Sensor-Based Crop Research

Protocol: VOC-Based Early Pathogen Detection Using Wearable Sensors

Objective: To detect plant pathogens before visible symptoms appear through continuous monitoring of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) using wearable olfactory sensors.

Materials and Equipment:

- WolfSens wearable electronic patches or equivalent VOC sensors [5]

- Target plant specimens (e.g., tomato plants at 4-6 leaf stage)

- Pathogen inoculum (e.g., Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus, Phytophthora infestans)

- Negative control plants

- Data logging system with wireless connectivity

- Statistical analysis software (R, Python, or equivalent)

Methodology:

- Sensor Calibration: Calibrate sensors against known VOC standards following manufacturer specifications. Establish baseline readings for healthy plants.

- Experimental Setup: Affix sensors to the abaxial surface of leaves using non-invasive adhesion. Ensure proper sensor-seal contact without damaging leaf tissues.

- Pathogen Inoculation: Inoculate treatment plants with pathogen suspensions using standardized inoculation techniques (e.g., spray inoculation, vector transmission). Maintain negative controls under identical conditions without pathogen exposure.

- Data Collection: Monitor VOC emissions continuously at 15-minute intervals for the experiment duration (typically 14-21 days). Record environmental parameters (temperature, humidity, light intensity) concurrently.

- Symptom Assessment: Daily visual assessment for disease symptoms using standardized rating scales. Document first symptom appearance for each plant.

- Data Analysis: Employ machine learning algorithms (e.g., 1D-CNN) to distinguish disease-specific VOC patterns from healthy emissions. Calculate detection accuracy metrics (sensitivity, specificity) and compare timing of sensor-based detection versus visual symptom appearance.

Validation Metrics: Successful implementation yields pathogen detection 7-10 days before visual symptoms with >95% accuracy for specific pathogens [5].

Protocol: Yield Monitoring for Treatment Effect Quantification

Objective: To precisely quantify spatial and temporal variability in crop productivity and correlate yield patterns with experimental treatments or environmental factors.

Materials and Equipment:

- Combine harvester equipped with yield monitoring system (e.g., Ag Leader Yield Monitor with InCommand display) [35]

- GPS receiver with sub-meter accuracy

- Calibration weights for mass flow sensor verification

- Data management software (e.g., EOSDA Crop Monitoring, AgFiniti)

- Soil sampling equipment for correlation analysis

Methodology:

- System Calibration: Perform pre-harvest calibration following manufacturer protocols. Conduct mass flow sensor calibration using known weights (2-3 calibration loads typically required). Verify moisture sensor accuracy with standard samples.

- Experimental Design: Establish harvesting patterns that minimize confounding factors. Ensure complete GPS coverage of experimental plots.

- Data Acquisition During Harvest: Monitor real-time yield data during harvesting operations. Document any operational anomalies that may affect data quality (e.g., stopping, partial passes, moisture variations).

- Data Processing: Filter erroneous data points resulting from harvest transitions, delays, or equipment issues. Synchronize yield data with spatial coordinates.

- Geospatial Analysis: Create yield maps with appropriate interpolation methods. Overlay treatment maps, soil sampling results, and remote sensing data to identify correlation patterns.

- Statistical Analysis: Conduct spatial statistics to quantify treatment effects while accounting for field variability. Calculate coefficient of variation (CV) to quantify yield variability (typically 28-33% in wheat systems) [33].

Validation Metrics: System should achieve yield measurement accuracy of ±1-2% after proper calibration, with spatial registration accuracy appropriate for plot-scale analysis [35].

Visualization of Sensor System Architectures

Smart Sensor System Architecture for Crop Research

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The implementation of sensor-based crop research requires specific reagents, materials, and analytical tools to ensure data quality and experimental rigor. The following table details essential components for establishing a comprehensive sensor research program.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Sensor-Based Crop Studies

| Category | Specific Products/Models | Research Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor Hardware | WolfSens wearable patches, Piezoelectric energy harvesters, Soil nutrient arrays | Continuous plant monitoring, Event-driven sensing, Soil chemistry quantification | VOC detection, Vibration sensing (>97.5% accuracy), NPK measurement [34] [5] |

| Data Acquisition Systems | Ag Leader InCommand display, STM32F103ZEH6 MCU, ADS1015IRUGR ADC | Real-time data logging, System control, Signal conversion | 16-bit resolution, <1µW power consumption, GPS synchronization [35] [34] |

| Communication Protocols | IEEE 802.15.4, IEEE 802.15.6, RF digital baseband transmitters | Wireless data transmission, Sensor network connectivity | Long-range communication (100m outdoor), High data rate, Low power operation [34] |

| Analytical Software | EOSDA Crop Monitoring, 1D-CNN algorithms, Vegetation index calculators | Yield mapping, Pattern recognition, Growth trend analysis | Multi-spectral analysis, 99.27% ML accuracy, Historical data comparison [33] [36] |

| Calibration Standards | VOC reference materials, NPK soil standards, Moisture calibration cells | Sensor calibration, Measurement validation, Quality assurance | Certified reference materials, Traceable to national standards |

Integration with Data Analytics and Machine Learning

The value proposition of smart sensors is substantially enhanced through integration with advanced data analytics and machine learning algorithms that transform raw sensor data into actionable research insights. Modern crop research leverages computational frameworks capable of processing multi-dimensional datasets from diverse sensor platforms. The implementation of one-dimensional convolutional neural networks (1D-CNN) has demonstrated particular efficacy for analyzing temporal sensor data streams, achieving recognition accuracy exceeding 97.5% for classifying vibration events relevant to plant health and environmental conditions [34]. These algorithms enable sophisticated pattern recognition that surpasses traditional analytical approaches.

For yield optimization research, supervised machine learning models have shown remarkable performance in correlating sensor data with crop outcomes. Recent research employing Gradient Boosting algorithms for crop recommendation based on soil and environmental parameters achieved impressive metrics: 99.27% accuracy, 99.32% precision, 99.36% recall, and 99.32% F1-score [36]. These models effectively integrate data from multiple sensor systems—including soil nutrient arrays, environmental monitors, and optical sensors—to generate precise recommendations for crop selection and management practices. The addition of Explainable AI (XAI) methodologies further enhances the research utility of these systems by providing transparent insights into the decision-making process, enabling researchers to understand the relative contribution of different sensor inputs to the final predictions.

Smart sensor technologies represent a transformative development in crop research methodology, enabling unprecedented quantification of plant-environment interactions across spatial and temporal scales. The integration of sophisticated sensing platforms—from wearable VOC detectors to yield monitoring systems—with advanced machine learning analytics creates a powerful paradigm for agricultural research. These technologies facilitate a deeper understanding of crop physiology, pathogen dynamics, and productivity factors while optimizing resource utilization through precise, data-driven interventions.