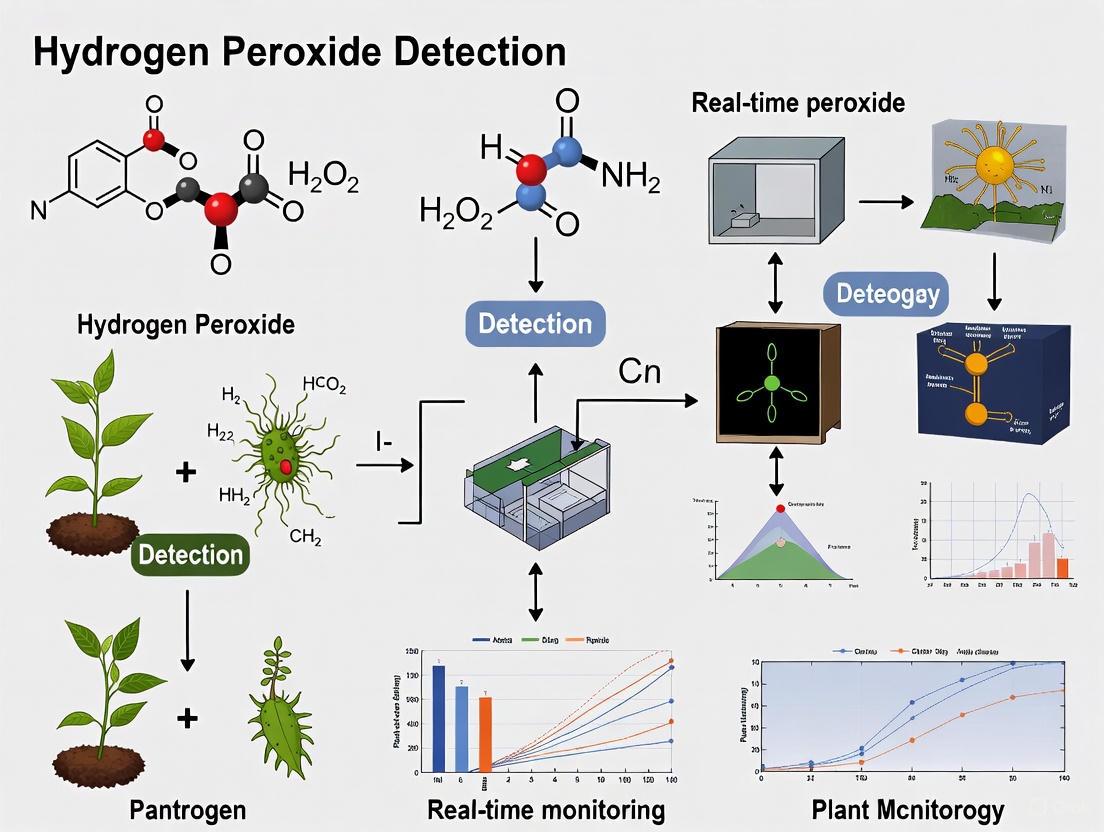

Real-Time Hydrogen Peroxide Detection in Plant-Pathogen Interactions: From Molecular Mechanisms to Field Applications

This article comprehensively examines the critical role of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) as a key signaling molecule in plant immune responses and the advanced technologies enabling its real-time detection.

Real-Time Hydrogen Peroxide Detection in Plant-Pathogen Interactions: From Molecular Mechanisms to Field Applications

Abstract

This article comprehensively examines the critical role of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) as a key signaling molecule in plant immune responses and the advanced technologies enabling its real-time detection. It explores the foundational biology of H₂O₂ production and perception in plants, details cutting-edge methodological advances from biosensors to in-field devices, and provides a critical analysis of current platforms for validation and optimization. Aimed at researchers and scientists in plant pathology and biomedical development, the content synthesizes recent breakthroughs in portable diagnostics, isothermal amplification, and CRISPR/Cas systems, offering a roadmap for translating detection technologies from laboratory research into practical field tools for early disease intervention and improved crop health management.

The Signaling Language of Plant Immunity: Understanding H₂O₂ in Defense Pathways

H₂O₂ as a Central Hub in Plant Immune Signaling Networks

Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) serves as a central signaling molecule in plant immune networks, orchestrating defense responses against pathogenic attacks. Recent advances in genetically encoded sensors and real-time monitoring technologies have revolutionized our understanding of H₂O₂ dynamics, revealing compartment-specific signaling patterns and stress-specific waveforms that enable early pathogen diagnosis. This technical guide synthesizes current knowledge on H₂O₂ production mechanisms, signaling pathways, and state-of-the-art detection methodologies, providing researchers with comprehensive protocols and tools for investigating redox signaling in plant-pathogen interactions.

In plant immune systems, hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) performs dual functions, acting as a direct antimicrobial agent while simultaneously serving as a key secondary messenger in defense signaling networks [1]. This paradoxical nature necessitates precise spatiotemporal regulation—at low concentrations, H₂O₂ activates defense genes and systemic resistance, while at high concentrations, it triggers programmed cell death and causes oxidative damage [2] [3]. The generation of H₂O₂ during pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) occurs within minutes of pathogen recognition, creating a wave-like propagation that activates downstream defense cascades [4]. Real-time monitoring of these H₂O₂ dynamics has revealed that different stress types produce distinctive temporal signatures, enabling early discrimination between pathogen attacks and abiotic stresses before visible symptoms appear [4]. The development of implantable sensors and genetically encoded probes now allows unprecedented resolution of subcellular H₂O₂ fluctuations, providing insights into its role as a central hub integrating multiple immune signaling pathways [5] [6].

H₂O₂ Production Mechanisms in Plant Immune Responses

Plants employ specialized enzyme systems for regulated H₂O₂ production in the apoplast, creating the oxidative burst that forms the frontline defense against pathogens:

Plasma Membrane NADPH Oxidases (RBOHs): The respiratory burst oxidase homolog (RBOH) enzyme family represents the best-characterized source of immune-activated H₂O₂ [3]. These plasma membrane-localized enzymes transfer electrons from cytoplasmic NADPH to extracellular oxygen, generating superoxide (O₂˙⁻), which rapidly dismutates to H₂O₂ either spontaneously or via superoxide dismutase (SOD) [2] [1]. RBOHD and RBOHF serve as key signaling nodes in Arabidopsis, activated through calcium-dependent phosphorylation and CDPK-mediated signaling [3].

Cell Wall Peroxidases: Apoplastic peroxidases catalyze H₂O₂ production through the oxidation of NADH, utilizing phenolic compounds as intermediates [3] [1]. These enzymes demonstrate pH-dependent activity and contribute significantly to the oxidative burst in French beans and other species following pathogen recognition [1].

Oxalate Oxidases and Amine Oxidases: Additional H₂O₂-generating systems in the apoplast include oxalate oxidases (germin-like proteins) and polyamine oxidases, which produce H₂O₂ during substrate conversion [2].

Multiple intracellular compartments contribute to H₂O₂ generation during immune signaling:

Chloroplasts: As major sites of ROS production, chloroplasts generate H₂O₂ through photosynthetic electron transport, particularly during photorespiratory reactions [2]. The Mehler reaction in photosystem I produces O₂˙⁻, which is subsequently converted to H₂O₂ by superoxide dismutase [2].

Mitochondria: The mitochondrial electron transport chain leaks electrons to oxygen, forming O₂˙⁻ that is dismutated to H₂O₂ by Mn-SOD [2]. The alternative oxidase (AOX) pathway regulates this production, with AOX overexpression reducing H₂O₂ accumulation [2].

Peroxisomes: H₂O₂ is generated as a byproduct of photorespiratory glycolate oxidation catalyzed by glycolate oxidase and during fatty acid β-oxidation [2].

Table 1: Primary Enzymatic Sources of H₂O₂ in Plant Immunity

| Enzyme System | Subcellular Location | Substrate | Activation Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| NADPH Oxidase (RBOH) | Plasma Membrane | NADPH + O₂ | Calcium signaling, CDPK phosphorylation, RAC/ROP GTPases |

| Cell Wall Peroxidase | Apoplast | NADH, Phenolic compounds | pH changes, substrate availability |

| Oxalate Oxidase | Apoplast | Oxalate | Pathogen elicitors, damage signals |

| Glycolate Oxidase | Peroxisomes | Glycolate | Photorespiration under stress |

| Electron Transport Chain | Chloroplasts/Mitochondria | O₂ | Electron leakage under stress conditions |

H₂O₂ Signaling Pathways in Plant Defense

Redox Relay Signaling and Thiol Modifications

H₂O₂ functions as a signaling molecule primarily through the oxidation of specific cysteine residues in target proteins, leading to structural and functional changes [3]. This redox signaling occurs through several mechanisms:

Sulfenylation Formation: H₂O₂ oxidizes reactive cysteine thiolate anions (-S⁻) to sulfenic acid (-SOH), a reversible modification that can alter protein activity, stability, or interactions [3]. Proteome-wide analyses in Arabidopsis have identified numerous sulfenylated proteins during immune responses [3].

Disulfide Bond Formation: Sulfenic acid intermediates can form intra- or intermolecular disulfide bonds with other cysteine residues, creating stable conformational changes that propagate signals [3].

Redox Relay Systems: Specific peroxiredoxins, such as PRXIIB, function as natural H₂O₂ sensors that transfer oxidative equivalents to downstream target proteins through thiol-disulfide exchanges [5]. This mechanism ensures signal specificity and prevents nonspecific oxidation.

Integration with Calcium and Kinase Signaling

H₂O₂ signaling integrates with other major defense pathways through cross-talk mechanisms:

Calcium Signaling: H₂O₂ activates calcium-permeable channels in the plasma membrane, increasing cytosolic Ca²⁺ levels that activate calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs) [1]. These kinases subsequently phosphorylate NADPH oxidases in a positive feedback loop that amplifies the ROS burst [3].

MAPK Cascades: H₂O₂ activates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades that phosphorylate transcription factors, leading to defense gene expression [1]. The MAPK pathway creates an amplification system that propagates the initial H₂O₂ signal.

Hormonal Cross-talk: H₂O₂ influences salicylic acid (SA) biosynthesis and signaling, creating distinct temporal waves that characterize different stress responses [4]. Pathogen infection typically triggers SA production within two hours of H₂O₂ accumulation, while mechanical wounding does not induce SA within four hours [4].

Table 2: H₂O₂-Mediated Signaling Components in Plant Immunity

| Signaling Component | Function in H₂O₂ Signaling | Downstream Targets |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory Burst Oxidase Homolog (RBOH) | Primary H₂O₂ generator | Amplification loop via CDPK phosphorylation |

| Type II Peroxiredoxin (PRXIIB) | Redox sensor and transducer | Multiple signaling proteins via disulfide transfer |

| Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinases (CDPKs) | Links Ca²⁺ and H₂O₂ signaling | NADPH oxidases, transcription factors |

| Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases (MAPKs) | Signal amplification | WRKY transcription factors, defense genes |

| Salicylic Acid (SA) | Parallel signaling pathway | NPR1, PR genes, systemic acquired resistance |

Real-Time H₂O₂ Monitoring Technologies

Genetically Encoded Biosensors

Recent advances in genetically encoded sensors have transformed our ability to monitor H₂O₂ dynamics with subcellular resolution:

roGFP2-PRXIIB Probe: This recently developed biosensor fuses redox-sensitive green fluorescent protein (roGFP2) to an endogenous H₂O₂ sensor, type II peroxiredoxin (PRXIIB) [5]. The probe demonstrates enhanced responsiveness and conversion kinetics compared to previous versions, enabling robust visualization of H₂O₂ production during abiotic and biotic stresses, and in growing pollen tubes [5].

Subcellular Targeting: roGFP2-PRXIIB can be targeted to specific compartments including cytosol, nuclei, mitochondria, and chloroplasts, revealing distinct temporal patterns of H₂O₂ accumulation during immune responses in different organelles [5]. Studies using this technology have revealed that pattern-triggered and effector-triggered immunity produce different H₂O₂ signatures across compartments [5].

HyPer Family Sensors: The HyPer sensor consists of circularly permuted yellow fluorescent protein (cpYFP) inserted into the regulatory domain of the bacterial H₂O₂-sensing protein OxyR [7] [8]. Upon H₂O₂-induced disulfide bond formation, the excitation spectrum shifts, with maximum excitation changing from 405 nm (reduced) to 488 nm (oxidized) [7]. HyPer has been codon-optimized for use in various systems, including plant-pathogenic fungi like Magnaporthe oryzae (MoHyPer) [8].

Nanosensor Multiplexing Platforms

Carbon nanotube-based sensors enable real-time decoding of different plant stresses through simultaneous monitoring of multiple signaling molecules:

Corona Phase Molecular Recognition (CoPhMoRe): This approach uses carbon nanotubes wrapped in specific polymers that recognize and bind to target molecules, quenching near-infrared fluorescence upon binding [4]. Researchers have developed highly selective sensors for salicylic acid (SA) that show minimal response to other plant hormones [4].

Multiplexed Stress Decoding: By pairing SA sensors with H₂O₂ sensors, researchers can observe unique patterns of these molecules produced by plants under different stress conditions [4]. This multiplexing reveals that heat, light, and bacterial infection trigger SA production at distinct time points after the initial H₂O₂ wave [4].

Implantable Self-Powered Systems: Recent innovations include implantable microsensors integrated with photovoltaic modules that collect environmental light for continuous power [6]. These systems have resolved the time and concentration specificity of H₂O₂ signals for abiotic stress, enabling continuous monitoring of signal molecule transmission in vivo [6].

Experimental Protocols for H₂O₂ Detection

Real-Time Monitoring Using Genetically Encoded Sensors

Protocol 1: roGFP2-PRXIIB Imaging for Subcellular H₂O₂ Dynamics

Materials:

- Arabidopsis lines expressing roGFP2-PRXIIB targeted to specific compartments

- Pathogen preparations (e.g., Pseudomonas syringae, flg22 peptide)

- Confocal microscope with 405 nm and 488 nm laser lines

- Image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, Fiji)

Procedure:

- Grow Arabidopsis seedlings expressing compartment-targeted roGFP2-PRXIIB under standard conditions.

- Mount seedlings for microscopy in appropriate physiological buffer.

- Establish baseline fluorescence: Acquire images using 405 nm and 488 nm excitation with emission at 516 nm.

- Apply immune elicitor (e.g., 1 μM flg22) while maintaining temperature and humidity.

- Acquire time-series images at both excitation wavelengths at 30-second to 2-minute intervals.

- Calculate ratiometric values (488/405 nm) for each time point after background subtraction.

- Generate kinetic curves of H₂O₂ dynamics for each subcellular compartment.

- Compare temporal patterns between different immune triggers (PTI vs ETI).

Data Interpretation:

- The ratiometric measurement minimizes artifacts from probe concentration variations.

- Compartment-specific targeting reveals organellar contributions to redox signaling.

- Different immune activators produce distinct spatiotemporal H₂O₂ signatures [5].

Multiplexed Stress Profiling Using Nanosensors

Protocol 2: Carbon Nanotube Sensor Integration for Stress Discrimination

Materials:

- Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs)

- Specific polymer wrappings for H₂O₂ and SA recognition

- Pak choi (Brassica rapa) or Arabidopsis plants

- Near-infrared fluorescence spectrometer or imaging system

- Stress application equipment (light, heat, mechanical wounding, pathogens)

Procedure:

- Prepare H₂O₂ and SA sensors by suspending SWCNTs with appropriate polymer wrappings.

- Introduce nanosensors into plant leaves via infiltration or microinjection.

- Validate sensor integration and function using control treatments.

- Apply distinct stresses to different plant groups:

- Mechanical wounding (leaf crush)

- Bacterial infection (Pseudomonas syringe)

- Light stress (high intensity)

- Heat stress (elevated temperature)

- Monitor near-infrared fluorescence simultaneously for H₂O₂ and SA sensors.

- Record fluorescence intensity changes over 4-6 hour time courses.

- Normalize data against reference sensors and calculate concentration changes.

- Analyze temporal patterns to identify stress-specific signatures.

Data Interpretation:

- H₂O₂ production typically occurs within minutes post-stress.

- SA production timing varies: 2 hours for heat/light stress, absent for mechanical wounding.

- The unique combination of H₂O₂ and SA dynamics creates identifiable stress fingerprints [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for H₂O₂ Signaling Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Primary Function | Key Features & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| roGFP2-PRXIIB | Genetically encoded biosensor | Real-time H₂O₂ detection | Enhanced sensitivity, subcellular targeting, ratiometric measurement [5] |

| HyPer Sensor | Genetically encoded biosensor | H₂O₂ quantification | Ratiometric, codon-optimized versions available (MoHyPer) [7] [8] |

| Carbon Nanotube Sensors | Nanosensors | Multiplexed stress signaling | CoPhMoRe technology, near-infrared fluorescence, SA and H₂O₂ detection [4] |

| flg22 Peptide | Pathogen-associated molecular pattern | Immune elicitor | Activates FLS2 receptor, triggers RBOH-dependent H₂O₂ production [9] [10] |

| DPI (Diphenyleneiodonium) | Chemical inhibitor | NADPH oxidase inhibition | Suppresses RBOH activity, validates enzyme source in H₂O₂ production |

| Amplex Red | Chemical probe | H₂O₂ detection | Fluorometric assay for extracellular H₂O₂, useful for apoplastic measurements |

The central role of H₂O₂ as an integrative hub in plant immune signaling networks continues to be elucidated through advancing detection technologies. Real-time monitoring with genetically encoded probes and nanosensors has revealed previously unappreciated complexity in H₂O₂ dynamics, including subcellular compartmentalization and stress-specific temporal patterns. Future research directions will likely focus on expanding the multiplexing capacity to simultaneously monitor larger sets of signaling molecules, developing non-invasive field-deployable sensors for agricultural applications, and elucidating the specific protein targets of H₂O₂-mediated oxidation that transmit immune signals. The integration of real-time H₂O₂ monitoring with other omics technologies will further uncover the complex networks positioned downstream of this central redox hub, potentially enabling novel strategies for enhancing crop resistance through redox engineering.

In plant-pathogen interactions, the spatiotemporal dynamics of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) are critical in determining the outcome of these biological encounters. Reactive oxygen species (ROS), particularly H₂O₂, serve a dual role in plant cells, acting as essential signaling molecules at low concentrations while becoming toxic oxidants that can damage cellular structures at high levels [11]. The precise modulation of H₂O₂ levels is therefore crucial for an effective immune response. This technical guide focuses on three major enzymatic sources responsible for generating and fine-tuning H₂O₂ signals: Respiratory Burst Oxidase Homologs (RBOHs), Class III Peroxidases (PRXs), and photorespiratory metabolism. Within the context of real-time H₂O₂ detection research, understanding these enzymatic sources provides the foundational knowledge necessary to interpret dynamic redox changes occurring during pathogen challenge. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical resource for researchers investigating these complex enzymatic systems, with particular emphasis on methodologies enabling real-time visualization of H₂O₂ fluxes.

RBOHs: Specialized ROS-Generating Enzymes at the Plasma Membrane

Biochemical Mechanisms and Regulatory Networks

RBOHs, also known as NADPH oxidases, are transmembrane enzymes that catalyze the production of superoxide (O₂⁻) by transferring electrons from cytoplasmic NADPH to extracellular oxygen. This superoxide is rapidly converted to H₂O₂, either spontaneously or through enzymatic activity [11]. The RBOHD enzyme in Arabidopsis has been identified as a key player in initiating ROS-mediated systemic signaling during both biotic and abiotic stress [12]. These enzymes function as critical signaling nodes that integrate multiple upstream signals into a coordinated oxidative burst.

Table 1: Key RBOH Isoforms and Their Characteristics in Plant Immunity

| Isoform | Cellular Localization | Primary Function in Immunity | Regulatory Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBOHD | Plasma Membrane | Pattern-triggered immunity (PTI), systemic signaling | Calcium binding, phosphorylation, CDPK activation |

| RBOHF | Plasma Membrane | Hypersensitive response (HR), stomatal closure | Similar to RBOHD, synergistic with RBOHD |

| RBOHB | Various membranes | Salt stress response, potentially in immunity | Transcriptional upregulation, post-translational modification |

Experimental Approaches for RBOH Activity Monitoring

Investigating RBOH-generated H₂O₂ requires methodologies capable of capturing the rapid, localized bursts characteristic of their activity. The HyPer sensor system has been optimized for real-time detection in fungal pathogens and can be adapted for plant systems [7] [8]. This genetically encoded probe consists of a circularly permuted yellow fluorescent protein (cpYFP) inserted into the regulatory domain of the prokaryotic H₂O₂-sensing protein OxyR, providing high specificity for H₂O₂ due to a hydrophobic pocket that prevents attack by charged oxidants [7].

Protocol: HyPer Sensor Implementation for RBOH-Derived H₂O₂ Detection

- Sensor Selection: Choose HyPer-2 variant for improved dynamic range and expression characteristics

- Transformation: Employ protoplast transformation or stable transgenic generation

- Imaging Setup: Utilize confocal laser scanning microscopy with appropriate filter sets (excitation at 405 nm and 488 nm, emission at 516 nm)

- Ratiometric Analysis: Calculate ratio of fluorescence (488/405 nm) to quantify H₂O₂ levels independent of sensor concentration

- Control Experiments: Include pH controls using SypHer (pH-sensitive, H₂O₂-insensitive variant) to account for potential pH artifacts [7]

- Pathogen Challenge: Apply pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or live pathogens while continuously monitoring H₂O₂ dynamics

For researchers studying appressorium-forming pathogens like Magnaporthe oryzae, codon optimization of HyPer for the target organism is essential for robust expression [8]. In plate reader assays, the addition of specific NADPH oxidase inhibitors such as diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) can help distinguish RBOH-derived H₂O₂ from other sources.

Class III Peroxidases: Multifunctional Enzymes with Dual Roles

Structural Features and Subcellular Localization

Class III peroxidases (PRXs) are heme-containing enzymes of the secretory pathway characterized by their high redundance and versatile functions [13]. These enzymes typically have a molecular weight of 30-45 kDa and contain conserved structural elements including N-terminal signal peptides, binding sites for heme and calcium, and four conserved disulfide bridges that contribute to their stability [14]. Approximately half of the class III peroxidases encoded in plant genomes contain transmembrane domains, leading to their localization in various cellular compartments including tonoplast, plasma membrane, and detergent-resistant membrane fractions [13].

Table 2: Membrane-Associated Class III Peroxidases and Their Functions

| Peroxidase | Species | Localization | Documented Role in Stress Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| AtPrx64 | Arabidopsis thaliana | Plasma Membrane | Lignification of sclerenchyma, Casparian strip formation |

| ZmPrx01 | Zea mays | Plasma Membrane | Development and oxidative stress response |

| CroPrx01 | Catharanthus roseus | Tonoplast (inner surface) | Vacuolar oxidative processes |

| MtPrx02 | Medicago truncatula | Detergent-resistant membranes | Response to nitrogen starvation, wounding, pathogen attack |

Dual Function in ROS Generation and Scavenging

Class III peroxidases exhibit a unique duality in ROS metabolism—they can both generate and scavenge H₂O₂ depending on environmental conditions and substrate availability [14]. In the presence of calcium and specific substrates, these enzymes can produce H₂O₂ through various mechanisms, including the oxidation of NADH or the hydroxylic cycle. Conversely, they can also decompose H₂O₂ when acting on classical peroxidase substrates. This functional plasticity allows peroxidases to fine-tune apoplastic H₂O₂ levels with remarkable precision.

The peroxidase cycle involves these key reactions:

- Native state restoration: Fe³⁺-PRX + H₂O₂ → Compound I (Fe⁴⁺=O P⁺•) + H₂O

- One-electron reduction: Compound I + AH₂ → Compound II (Fe⁴⁺=O P) + AH•

- Second one-electron reduction: Compound II + AH₂ → Fe³⁺-PRX + AH• + H₂O

Simultaneously, the hydroxylic cycle can generate H₂O₂ through the oxidation of NADH: NADH + H⁺ + O₂ → NAD⁺ + H₂O₂

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Peroxidase Activity in Apoplastic Fractions

- Apoplastic Fluid Extraction: Infiltrate leaves with 20 mM ascorbic acid in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), centrifuge (900 × g, 10 min, 4°C) to collect apoplastic washing fluid

- Enzyme Activity Assay: Monitor guaiacol oxidation at 470 nm (ε = 26.6 mM⁻¹cm⁻¹) in reaction mixture containing 10 mM guaiacol, 1 mM H₂O₂, and apoplastic extract in phosphate buffer

- H₂O₂ Production Assay: Measure NADH oxidation at 340 nm in reaction mixture containing 0.2 mM NADH, 0.2 mM MnCl₂, and 50 µM 2,4-dichlorophenol

- In-Gel Detection: Use native PAGE followed by staining with 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB) to visualize peroxidase isoforms

- Inhibition Studies: Apply specific peroxidase inhibitors such as potassium cyanide (1 mM) or sodium azide (1 mM) to confirm enzyme specificity

Advanced techniques for studying peroxidase functions include tissue-specific silencing approaches, as demonstrated in pepper where suppression of CaDIR7 (interacting with peroxidases) reduced plant defense against Phytophthora capsici [11]. Similarly, in cotton, silencing GhUMC1 increased susceptibility to Verticillium dahliae and downregulated JA and SA signaling pathways [11].

Photorespiration: The Metabolic Interface of Photosynthesis and Defense

The Photorespiratory Pathway and H₂O₂ Production

Photorespiration is a high-flux metabolic pathway that spans across chloroplasts, peroxisomes, and mitochondria, intimately linking photosynthetic carbon assimilation with defense responses [15] [16]. This pathway is initiated when ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) oxygenates RuBP instead of carboxylating it, producing 2-phosphoglycolate (2-PG) that must be metabolized through the photorespiratory cycle. A crucial step for H₂O₂ production occurs in peroxisomes where glycolate oxidase (GOX) converts glycolate to glyoxylate, simultaneously generating H₂O₂ as a byproduct [16].

The photorespiratory pathway contributes significantly to cellular H₂O₂ pools, particularly under conditions that promote stomatal closure—a common defense response to pathogen attack. When stomata close, CO₂ limitation inside the leaf increases, favoring Rubisco oxygenation over carboxylation and consequently enhancing photorespiratory flux and associated H₂O₂ production [15].

Methodologies for Investigating Photorespiratory H₂O₂

Protocol: Assessing Photorespiratory H₂O₂ Contribution to Immune Responses

- Environmental Control: Establish conditions that modulate photorespiratory rate (low CO₂: 100 ppm vs high CO₂: 1000 ppm; different O₂ concentrations: 2% vs 21%)

- Genetic Manipulation: Utilize photorespiratory mutants (e.g., gox, hpr, shm) or transgenic lines with altered expression of photorespiratory enzymes

- H₂O₂ Quantification: Employ HyPer sensors targeted to peroxisomes or cytosol to monitor compartment-specific H₂O₂ changes

- Metabolite Profiling: Measure photorespiratory intermediates (glycolate, glycine, serine) using GC-MS or LC-MS to correlate with H₂O₂ dynamics

- Pathogen Assay: Compare disease progression and H₂O₂ patterns in photorespiratory mutants versus wild-type plants

Research using GOX-silenced tobacco and Arabidopsis mutants has demonstrated compromised non-host resistance to bacterial pathogens and reduced effector-triggered immunity responses, directly linking photorespiratory H₂O₂ to effective plant immunity [16]. Importantly, null mutants of HAOX (hydroxy-acid oxidase), which belongs to the same enzyme family as GOX, show similar compromised immunity phenotypes, reinforcing the significance of peroxisomal H₂O₂ in defense [16].

Integrated Visualization of H₂O₂ Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected network of H₂O₂ production from RBOHs, peroxidases, and photorespiration during plant-pathogen interactions:

Integrated H₂O₂ Production and Detection in Plant Immunity

Advanced Research Toolkit for Real-Time H₂O₂ Detection

Research Reagent Solutions for H₂O₂ Visualization

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Studying Enzymatic H₂O₂ Sources

| Research Tool | Specific Function | Application Context | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| HyPer Sensor | Genetically encoded H₂O₂ detection | Real-time ratiometric imaging in living cells | Requires codon optimization for different species [8] |

| SypHer Control | pH-sensitive control for HyPer | Distinguishing pH artifacts from true H₂O₂ signals | Contains point mutation in OxyR domain [7] |

| Amplex Red | Chemical detection of H₂O₂ | Extracellular H₂O₂ measurement in apoplastic washes | Less specific than genetic sensors |

| DAB Staining | Histochemical detection of H₂O₂ | Spatial localization in tissues | Long incubation (8-12 hours), semi-quantitative [8] |

| Diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) | RBOH inhibitor | Distinguishing NADPH oxidase-derived H₂O₂ | Not completely specific to RBOHs |

| Codon-Optimized HyPer | Enhanced expression in heterologous systems | Pathogen H₂O₂ dynamics (e.g., Fusarium, Magnaporthe) | Based on target organism codon bias [8] |

Integrating Single-Cell and Spatial Technologies

Emerging spatial and single-cell technologies now enable unprecedented resolution in studying plant-pathogen interactions. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics can reveal how different cell types contribute to and respond to H₂O₂-mediated defense signaling [17]. These approaches are particularly valuable for understanding the heterogeneity of immune responses within tissues, moving beyond bulk tissue analyses that may mask important cell-type-specific behaviors.

For proteomic and metabolic profiling adjacent to H₂O₂ dynamics, techniques such as laser capture microdissection coupled with nanodroplet-based sampling enable profiling of small cell populations, while mass spectrometry imaging can resolve spatial distribution of metabolites at near single-cell resolution [17]. These methodologies provide complementary data to real-time H₂O₂ imaging, facilitating a systems-level understanding of redox signaling in plant immunity.

The enzymatic systems governing H₂O₂ production in plant-pathogen interactions—RBOHs, Class III peroxidases, and photorespiration—represent interconnected networks that enable precise spatiotemporal control of redox signaling. RBOHs generate rapid, signal-initiated oxidative bursts; peroxidases provide fine-tuning capability through their dual generating/scavenging functions; and photorespiration links metabolic status to defense signaling, particularly under conditions that limit carbon assimilation. The advancement of real-time detection methodologies, particularly genetically encoded sensors like HyPer with improved codon optimization for diverse plant and pathogen systems, continues to transform our understanding of these dynamic processes. Future research integrating single-cell omics with real-time H₂O₂ imaging will further elucidate how plants achieve specificity in redox signaling across diverse cell types and in response to different pathogenic challenges.

Distinctive H₂O₂ Signatures for Different Stress Types

In plant biology, reactive oxygen species (ROS), particularly hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), have transcended their historical reputation as mere cytotoxic agents. It is now established that H₂O₂ functions as a central secondary messenger in plant signaling networks, integrating responses to a wide array of environmental stresses [18] [19]. Its relative stability compared to other ROS, capacity to traverse cell membranes via aquaporins, and specific oxidation of target proteins make it an ideal signaling molecule [18] [11].

A paradigm-shifting concept emerging from recent research is that the H₂O2 produced in response to different stressors is not a uniform, generic signal. Instead, the dynamics, amplitude, and spatial distribution of H₂O₂ accumulation encode information specific to the stress type encountered [20]. This "H₂O₂ signature" is a critical component of the plant's strategy to tailor its defense and acclimation responses for maximal efficacy and efficiency. Decoding these signatures is paramount for understanding plant immunity and developing strategies for real-time, pre-symptomatic stress diagnosis in plant-pathogen interactions [20].

The Biochemical Foundation of Stress-Specific H₂O₂ Signatures

The production and scavenging of H₂O₂ are highly compartmentalized and regulated processes. Multiple enzymatic sources contribute to the spatiotemporal specificity of the H₂O₂ signature.

- NADPH Oxidases (RBOHs): Plasma membrane-localized enzymes that are major producers of apoplastic superoxide, which is rapidly converted to H₂O₂. RBOHs, particularly RBOHD, are crucial for amplifying signals and are activated by various stimuli, including calcium influx and phosphorylation [18] [19].

- Cell Wall Peroxidases: These enzymes can generate H₂O₂ in the apoplast and are also involved in cross-linking cell wall components to reinforce it as a physical barrier against pathogens [11].

- Chloroplasts and Peroxisomes: Under stress, photosynthetic electron transport chains and photorespiratory pathways in these organelles become significant sources of H₂O₂ [19].

The specific blend of these sources activated upon stress perception, combined with the concurrent mobilization of the antioxidant scavenging system, shapes the unique H₂O₂ waveform for each stress [21].

Interaction with Hormonal Signaling

H₂O₂ signatures do not operate in isolation; they are part of a complex signaling web with key phytohormones. The interplay between H₂O₂ and salicylic acid (SA) is particularly critical in defense against biotrophic pathogens, where they can act both upstream and downstream of each other to establish systemic acquired resistance (SAR) [20] [22]. Similarly, H₂O₂ interacts with jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene (ET) signaling pathways, enabling the plant to fine-tune its response based on the nature of the threat [11] [22].

Experimental Evidence: Profiling Distinct H₂O₂ Signatures

Multiplexed Nanosensor Revelation

Groundbreaking work using multiplexed nanosensors has provided direct, real-time evidence for stress-specific H₂O₂ signatures. Researchers simultaneously monitored H₂O₂ and SA levels in living plants subjected to different stresses.

The data below summarizes the distinct temporal wave characteristics observed for each stress type, demonstrating unique H₂O₂ signatures.

Table 1: Distinct Temporal Wave Characteristics of H₂O₂ and SA under Different Stresses

| Stress Type | H₂O₂ Signature | SA Signature | Proposed Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogen Stress | Sharp, high-amplitude peak; rapid onset [20] | Strong, sustained increase [20] | Triggers Hypersensitive Response (HR) and Systemic Acquired Resistance (SAR) [11] |

| Mechanical Wounding | Rapid, transient spike [20] | Moderate, slower increase [20] | Immediate alert signal; activation of local and jasmonate-dependent defenses [19] |

| Heat Stress | Slow, moderate, sustained increase [20] | Weak, delayed response [20] | Acclimation and protection of photosynthetic machinery |

| Light Stress | Defined waveform with specific kinetic properties [20] | Defined waveform with specific kinetic properties [20] | Modulation of redox homeostasis and antioxidant capacity |

These distinct signatures suggest that the early H₂O₂ waveform contains encrypted information that the plant deciphers to initiate a stress-appropriate genetic and metabolic reprogramming [20].

Red Light-Induced H₂O₂ in Powdery Mildew Resistance

A specific example of a tailored H₂O₂ signature comes from research on oriental melon and powdery mildew. Pre-treatment with red light was shown to enhance resistance by specifically activating a defense-related H₂O₂ signature. This involved:

- Increased NADPH oxidase activity and H₂O₂ accumulation: Red light pre-treatment significantly boosted the activity of the H₂O₂-producing enzyme NADPH oxidase and subsequent H₂O₂ levels, which were further amplified upon pathogen challenge [23].

- WRKY50-RBOHD Module: Red light-induced H₂O₂ production was mediated by the transcriptional upregulation of RBOHD by the transcription factor WRKY50. Silencing either WRKY50 or RBOHD abolished the red light-induced H₂O₂ signature and the consequent resistance [23].

This demonstrates how a defined environmental cue (red light) primes a specific H₂O₂ production module to create a signature that confers enhanced immunity.

Methodologies for Detecting H₂O₂ Signatures

Accurately capturing the nuanced dynamics of H₂O₂ signatures requires sophisticated tools. The field has moved beyond destructive, endpoint assays to real-time, in vivo monitoring.

Real-Time Monitoring Technologies

- Genetically Encoded H₂O₂ Indicators (GEHIs): Sensors like HyPer and roGFP2-Orp1 allow real-time monitoring of H₂O₂ dynamics in specific cellular compartments [24]. Recent advances include far-red sensors like oROS-HT635, which offer advantages such as minimal autofluorescence, lack of photochromic artifacts, and compatibility with multiplexing alongside green fluorescent sensors for other analytes (e.g., Ca²⁺) [24].

- Plant Nanobionic Sensors: Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) wrapped with specific DNA oligomers can be embedded in the plant apoplast. These nanosensors fluoresce in the near-infrared range and are quenched upon binding H₂O₂, enabling non-destructive, real-time monitoring of apoplastic H₂O₂ fluxes [20]. This technology was pivotal in discriminating the stress-specific waves shown in Table 1.

Supporting and Traditional Assays

- Enzymatic Activity Fingerprinting: Semi-high throughput 96-well assays can profile the activities of nine key antioxidant enzymes (e.g., CAT, APX, SOD, POX) from a single extraction. This provides a functional readout of the plant's scavenging capacity, which directly shapes the H₂O₂ signature [21].

- Colorimetric Methods: Titanium(IV) oxysulfate forms a yellow complex with H₂O₂, which can be quantified spectrophotometrically in solutions or using commercial test strips for liquid and vapor-phase detection [25].

- Electrochemical Sensors: Microelectrodes, such as integrated Pt microelectrodes, allow for highly sensitive, real-time amperometric detection of H₂O₂, useful in defined systems [26].

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit for H₂O₂ Signature Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| oROS-HT635 GEHI [24] | Genetically encoded far-red fluorescent sensor for H₂O₂ | Enables multiparametric imaging with low background; targetable to subcellular locales |

| SWNT-based Nanosensors [20] | Near-infrared fluorescent probes for apoplastic H₂O₂ | Real-time, in planta monitoring; high photostability |

| Antioxidant Enzyme Assay Panel [21] | Profiles 9 key enzyme activities (SOD, CAT, APX, etc.) | Semi-high throughput; functional phenotyping of scavenging capacity |

| Titanium(IV) Oxysulfate Test Strips [25] | Colorimetric detection of H₂O₂ in liquid and gas phases | Low-cost, simple use; suitable for time-integrated measurements |

| Pt Microelectrode [26] | Electrochemical (amperometric) detection of H₂O₂ | Highly sensitive, real-time monitoring in solutions |

Experimental Workflow for Signature Analysis

The following diagram illustrates a generalized integrated workflow for capturing and validating a distinctive H₂O₂ signature in a plant-pathogen interaction context, incorporating the tools described above.

The concept of distinctive H₂O₂ signatures represents a significant leap in understanding plant stress signaling. The ability to detect these signatures in real-time using advanced nanosensors and GEHIs opens up transformative applications. In research, it allows for the precise dissection of signaling pathways and their interplay. For agriculture, this technology holds the promise of pre-symptomatic stress diagnosis in the field, enabling timely and targeted interventions [20].

Future work will focus on further decoding the "H₂O₂ wave language"—understanding how specific kinetic parameters are transduced into defined genetic and metabolic outcomes. Integrating H₂O₂ signature data with other signaling waves (e.g., Ca²⁺, electrical) into a comprehensive model will be crucial for developing climate-resilient crops and smarter agricultural practices, moving us toward a future where we can not only observe but also interpret and respond to the silent language of plant stress.

Crosstalk with Phytohormones and Other Signaling Molecules

Plant survival in nature depends on the ability to perceive attack and orchestrate robust yet specific defense responses. This process is governed by a sophisticated signaling network in which phytohormones act as central regulators. The interactions between different hormone pathways—a phenomenon known as hormone crosstalk—enable the plant to fine-tune its immune response according to the specific biotic interactor and the environmental context [27]. A key early event in both plant immunity and pathogen virulence is the rapid production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), particularly hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), which acts as a critical signaling molecule [7] [8] [28]. Therefore, real-time detection of H₂O₂ dynamics offers a powerful window into the initial stages of plant-pathogen interactions and the subsequent hormonal signaling cascades. This technical guide examines the complex crosstalk between major phytohormones and other signaling molecules, with a focus on how real-time H₂O₂ monitoring can elucidate the underlying mechanisms and integrated network topology of plant immunity.

Phytohormone Pathways and Crosstalk Hubs in Defense

The plant immune system consists of multiple hormone-regulated sectors that interact through synergistic, antagonistic, and additive interactions. The jasmonic acid (JA) and salicylic acid (SA) pathways form the backbone of the hormone-regulated immune system [27].

Major Defense Hormone Pathways

- Jasmonic Acid (JA): The JA pathway can be subdivided into two branches. The ERF branch is co-regulated by ethylene (ET) and is generally activated against necrotrophic pathogens. The MYC branch is co-regulated by abscisic acid (ABA) and typically provides protection against chewing insects [27].

- Salicylic Acid (SA): The SA pathway is primarily directed against biotrophic pathogens and is often antagonistic to the JA pathway, a classic example of defensive crosstalk that prioritizes responses based on the nature of the threat [27].

- Ethylene (ET): Works synergistically with the ERF branch of the JA pathway to mount defenses against necrotrophic pathogens [27].

- Abscisic Acid (ABA): Traditionally associated with abiotic stress, ABA co-regulates the MYC branch of the JA pathway and interacts with other hormones in complex ways during immune responses [27] [29].

Key Transcription Factors as Crosstalk Integration Nodes

Crosstalk is modulated at multiple regulatory levels, with specific transcription factors acting as major integration hubs:

- MYC2: A master transcription factor of the JA pathway, which is a major target for modulation by other hormones [27].

- ORA59: A key integrator for the JA/ET synergistic pathway, also regulated by other hormonal signals [27].

The following diagram illustrates the core JA signaling pathway and its major crosstalk nodes with other hormones:

Figure 1: Jasmonic Acid Signaling Pathway and Major Crosstalk Nodes. The core JA pathway centers on the COI1-JAZ-MYC2/ORA59 module. MYC2 and ORA59 transcription factors serve as key integration points for signals from other hormones, including the antagonistic effect of SA and synergistic regulation by ET and ABA [27].

Real-Time H₂O₂ Detection: A Window into Early Signaling Events

The production of reactive oxygen species, particularly H₂O₂, is one of the earliest cellular responses in plant-pathogen interactions. Real-time monitoring of H₂O₂ provides crucial insights into the initial signaling events that subsequently activate complex hormone crosstalk.

Advanced Methodologies for H₂O₂ Detection

Multiple sophisticated approaches have been developed to monitor H₂O₂ dynamics in real-time:

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of H₂O₂ Detection Methods

| Method | Detection Principle | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Key Advantage | Reported Sensitivity/Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HyPer Sensor | Genetically encoded; ratiometric fluorescence (Ex:405/488nm, Em:516nm) | Seconds to minutes | Subcellular | High specificity for H₂O₂; reversible | Ratio [485/380 nm] increased from 3.2 to 6.4 with 50 mM H₂O₂ [7] |

| Electrochemical Microsensor | Direct H₂O₂ electrochemistry at Pt microelectrode | Real-time (seconds) | Microscopic (tissue level) | In-situ measurement in leaves; minimal perturbation | Detection possible 3 hours post-inoculation vs. 72 hours for DAB staining [30] |

| H₂DCFDA Fluorescence | Oxidation-sensitive fluorescent dye | Minutes | Cellular | Simplicity; cost-effectiveness | Higher sensitivity than commercial luminescence spectrophotometers [28] |

| MoHyPer (Codon-Optimized) | Fungal-codon-optimized HyPer | Seconds to minutes | Subcellular | Robust expression in fungi | Enabled H₂O₂ monitoring in Magnaporthe oryzae appressoria [8] |

Experimental Workflow for Real-Time H₂O₂ Monitoring

A generalized protocol for investigating H₂O₂ dynamics during plant-pathogen interactions using genetically encoded sensors is outlined below:

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Real-Time H₂O₂ Monitoring. The process begins with appropriate sensor selection, followed by system preparation which may require codon optimization for fungal pathogens [8], pathogen inoculation, and real-time imaging using suitable platforms, culminating in data analysis that correlates H₂O₂ dynamics with hormonal signaling events.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for H₂O₂ and Hormone Crosstalk Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Technical Specifications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| HyPer Sensor | Genetically encoded H₂O₂ sensor | Excitation maxima: 405 nm (reduced), 488 nm (oxidized); Emission: 516 nm | Ratiometric measurement; reversible with DTT; requires codon optimization for fungi [7] [8] |

| H₂DCFDA | Chemical fluorescent probe for ROS | Oxidation-sensitive dye; becomes fluorescent upon oxidation | Less specific than HyPer; subject to esterase concentration artifacts; suitable for optical devices [28] |

| SypHer Control | H₂O₂-insensitive control for HyPer | Point mutation in OxyR-RD domain; pH-sensitive only | Essential control for pH-related artifacts in HyPer experiments [7] |

| Electrochemical Microsensor | In-situ H₂O₂ detection in leaves | Platinum microelectrode; measures H₂O₂ electrochemically | Enables real-time monitoring in intact plants with minimal damage [30] |

| Diaminobenzidine (DAB) | Histochemical stain for H₂O₂ | H₂O₂-dependent polymerization produces brown precipitate | Low temporal resolution (8-12 hour incubation); difficult to quantify [8] |

Hormone Crosstalk Mechanisms and H₂O₂ Interconnections

The molecular mechanisms of hormone crosstalk occur at multiple regulatory levels, with H₂O₂ often serving as a key intermediary in these interactions.

Levels of Crosstalk Regulation

- Transcriptional Regulation: Hormonal signals converge on key transcription factors like MYC2 and ORA59, which integrate inputs from multiple pathways to determine transcriptional outputs [27].

- Protein Stability Modulation: Components of hormone signaling pathways are regulated through protein degradation, such as the COI1-mediated degradation of JAZ repressors in JA signaling [27].

- Hormone Homeostasis: Hormone pathways mutually regulate each other's biosynthesis and metabolism, creating complex feedback and feedforward loops [27] [31].

- Network-Level Robustness: Antagonistic interactions between sectors (e.g., SA-JA antagonism) can provide robustness to the immune system, ensuring that if one sector is compromised, another can be derepressed to maintain defense [27].

H₂O₂ as a Central Signaling Integrator

Hydrogen peroxide functions as a nexus in stress signaling networks, interacting with multiple hormone pathways:

- ABA-H₂O₂ Crosstalk: ABA-induced H₂O₂ production in guard cells mediates stomatal closure, creating a positive feedback loop that limits pathogen entry [29].

- SA-H₂O₂ Integration: SA activates peroxidase-mediated ROS signals that integrate into Ca²⁺/calcium-dependent protein kinases-mediated ABA signaling branches [29].

- JA Signaling Interconnection: The core JA signaling components (COI1, JAZ, MYC2) represent intersections with signal transduction pathways of other hormones, including auxin, ethylene, ABA, and SA [29].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: HyPer-based H₂O₂ Monitoring in Plant-Fungal Interactions

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to study H₂O₂ dynamics in Fusarium graminearum and Magnaporthe oryzae [7] [8]:

Materials:

- HyPer sensor (codon-optimized for target organism)

- Confocal microscope or microtiter plate fluorometer

- Oxidizing agent: H₂O₂ (1-100 mM stocks)

- Reducing agent: Dithiothreitol (DTT, 10-50 mM stocks)

- Appropriate growth media for organism

Procedure:

- Sensor Expression: Transform target organism with HyPer construct. For fungal systems, use codon-optimized versions (e.g., MoHyPer for Magnaporthe oryzae) to ensure robust expression [8].

- Sample Preparation: Grow transformed hyphae or plant tissues on solid minimal medium in appropriate imaging chambers.

- Baseline Measurement: Acquire initial fluorescence readings with excitation at 405 nm and 488 nm, emission at 516 nm. Calculate baseline ratio (488/405 nm).

- Treatment Application: Apply pathogen-derived elicitors or live pathogens to the system.

- Time-Series Imaging: Continuously monitor fluorescence ratios at 30-second to 5-minute intervals depending on response dynamics.

- Control Experiments:

- Validate specificity with H₂O₂ scavengers (e.g., catalase).

- Test reversibility with DTT treatment (10-50 mM).

- Include SypHer transformants as pH controls [7].

- Data Analysis: Calculate ratio (488/405 nm) over time. Normalize to baseline. Compare treatment effects statistically.

Technical Notes: For microtiter plate assays, automated injectors can be used to add H₂O₂ or DTT during measurement. HyPer response is linear up to approximately 10 mM H₂O₂ before reaching saturation [7].

Protocol: Electrochemical H₂O₂ Detection in Leaves

This protocol is adapted from in-situ electrochemical monitoring in Agave tequilana leaves [30]:

Materials:

- Dual-function platinum microelectrode

- Potentiostat

- Reference electrode (Ag/AgCl)

- Sterile inoculation tools

- Bacterial culture (e.g., Enterobacter cloacae)

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Fabricate platinum microelectrodes with tip diameters of 1-10 μm.

- Electrode Calibration: Validate sensor performance in H₂O₂ standards using cyclic voltammetry.

- Plant Preparation: Grow plants under controlled conditions. For inoculation studies, use standardized plant developmental stages.

- Pathogen Inoculation: Inoculate roots or leaves with bacterial suspension at defined densities (e.g., 10⁸ CFU/mL).

- In-situ Measurement: Insert microelectrode into leaf tissue at defined time points post-inoculation.

- Electrochemical Recording: Perform cyclic voltammetry scans and measure H₂O₂ oxidation current.

- Data Correlation: Compare electrochemical signals with parallel DAB staining and pathogen growth assays.

Technical Notes: This method detected H₂O₂ in leaves just 3 hours after bacterial inoculation, compared to 72 hours required for DAB staining visualization [30].

The real-time detection of H₂O₂ provides a critical methodological advance for unraveling the complex crosstalk between phytohormones during plant-pathogen interactions. The signaling networks that govern plant immunity exhibit emergent properties that cannot be fully understood by studying individual components in isolation [32]. The integration of quantitative H₂O₂ monitoring with genetic, molecular, and biochemical approaches enables researchers to move from descriptive models of hormone crosstalk to predictive, mechanistic understanding of how plants integrate multiple signals to achieve appropriate defense outcomes. Future research directions will likely focus on combining these real-time detection methods with systems biology approaches to construct multiscale models that can predict the outcomes of plant-pathogen interactions under varying environmental conditions, ultimately contributing to the development of crops with enhanced disease resistance [32] [33].

From Oxidative Burst to Systemic Acquired Resistance

The oxidative burst, characterized by the rapid production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), is a cornerstone of early plant defense signaling. This whitepaper delineates the pathway from the initial ROS generation at the site of pathogen challenge to the establishment of broad-spectrum systemic acquired resistance (SAR). Framed within the context of a broader thesis on real-time hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) detection, this document provides a technical guide detailing the core mechanisms, signaling pathways, and experimental methodologies essential for researchers investigating plant-pathogen interactions. The integration of advanced detection technologies is emphasized as a critical component for elucidating the spatiotemporal dynamics of H2O2, a key ROS orchestrating the plant immune response.

In plant-pathogen interactions, the oxidative burst is one of the earliest observable defense responses, involving the rapid and transient production of massive amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [34]. As plants are sessile, they have evolved a broad range of such inducible defense responses to cope with pathogenic infections [34]. The ROS family involved includes the superoxide anion (O2⁻), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radical (OH•), and singlet oxygen (¹O2) [22]. Among these, H2O2 has garnered significant research interest due to its relative stability, ability to cross membranes via aquaporins, and dual role as a toxic antimicrobial agent and a crucial secondary messenger in signal transduction [22]. The precise spatial and temporal regulation of H2O2 production is a critical determinant in the transition from local defense to systemic immunity.

Core Mechanisms of ROS Production and Scavenging

The oxidative burst is primarily driven by several enzymatic systems. A key source is the plasma membrane NADPH oxidase complex, also known as Respiratory Burst Oxidase Homolog (RBOH) in plants, which is analogous to the system in animal phagocytes [34]. This enzyme catalyzes the production of superoxide (O2⁻) in the apoplast, which is rapidly dismutated to H2O2 [34]. Another significant source is the pH-dependent generation of H2O2 by cell wall peroxidases [34]. Additionally, other enzymes like oxalate oxidases, amine oxidases, and lipoxygenases contribute to ROS accumulation [22].

ROS Scavenging Systems

To prevent oxidative damage and maintain redox homeostasis, plants employ a sophisticated array of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants. Table: Plant Antioxidant Systems for ROS Scavenging

| Antioxidant Type | Example | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic | Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) | Catalyzes dismutation of O2⁻ to H2O2 and O2 [22] |

| Catalase (CAT) | Primarily detoxifies H2O2 into water and oxygen [22] | |

| Ascorbate Peroxidase (APX) | Reduces H2O2 to water using ascorbate [22] | |

| Glutathione Peroxidase (GPX) | Reduces H2O2 and organic hydroperoxides using glutathione [22] | |

| Non-Enzymatic | Glutathione | Tripeptide that acts as a redox buffer and directly scavenges ROS [22] |

| Carotenoids | Protects the photosynthetic apparatus from singlet oxygen damage [22] | |

| Tocopherols | Lipid-soluble antioxidants that protect cell membranes [22] | |

| Phenolic Compounds | Flavonoids and tannins with antioxidant and ROS-scavenging properties [22] |

The balance between these ROS-producing and ROS-scavenging systems allows for the transient, specific ROS signals necessary for effective defense communication [22].

Hypersensitive Response (HR) and Programmed Cell Death

The recognition of specific pathogen avirulence (Avr) effectors by plant resistance (R) proteins triggers a gene-for-gene interaction that often leads to the hypersensitive response (HR) [35]. A localized oxidative burst is a hallmark of HR, leading to programmed cell death (PCD) in the immediate vicinity of the infection site. This sacrifice of a few cells effectively walls off the pathogen and prevents its spread [36]. Studies in the Brassica napus-Leptosphaeria maculans (blackleg) pathosystem have demonstrated that resistant canola genotypes exhibit earlier accumulation of H2O2 and the emergence of cell death around inoculation sites compared to susceptible ones [36]. The resistant cotyledons form a protective region of intensive oxidative bursts that blocks further fungal advancement [36].

The diagram below illustrates the key signaling pathway leading from pathogen recognition to the hypersensitive response.

Systemic Acquired Resistance (SAR)

Following the localized HR, the entire plant can develop a long-lasting, broad-spectrum resistance known as Systemic Acquired Resistance (SAR) [22]. H2O2 from the oxidative burst is a pivotal orchestrator of this systemic defense [37]. It acts as a mobile signal or activates downstream secondary messengers that travel through the vasculature, priming distant tissues for enhanced defense readiness [22]. This priming results in the accumulation of salicylic acid (SA) and the coordinated expression of Pathogenesis-Related (PR) genes throughout the plant [34] [22].

Interplay with Phytohormones

The defense signaling network involves a complex interplay between ROS and phytohormones. Salicylic acid (SA) is predominantly associated with resistance against biotrophic pathogens and is intricately linked with the oxidative burst and SAR [22]. In contrast, jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene (ET) are typically involved in defense against necrotrophs and herbivorous insects [22]. These signaling pathways can be antagonistic, and ROS are key modulators within this complex cross-talk. For instance, the activation of the MAPK cascade factors MPK3 and MPK6 by H2O2 can induce ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR 6 (ERF6), which enhances plant defense in Arabidopsis [35].

Experimental Protocols for Studying ROS in Plant Immunity

Histochemical Staining for H2O2 and Cell Death

DAB (3,3'-Diaminobenzidine) Staining for H2O2:

- Principle: DAB polymerizes in the presence of H2O2, producing a brown precipitate that is visible under a microscope [8].

- Protocol: Excised plant tissues (e.g., inoculated cotyledons or leaves) are immersed in a 1 mg/mL DAB solution (pH 3.8). Infiltration may be applied to ensure thorough penetration. Samples are incubated in the dark for 8-12 hours. Subsequently, chlorophyll is cleared from the tissues by boiling in 95% ethanol, and the stained H2O2 deposits are visualized and quantified [36] [35].

- Considerations: DAB is highly specific for H2O2, but the required incubation time is long (8-12 hours), making it less suitable for real-time dynamics [8].

Trypan Blue Staining for Cell Death:

- Principle: Trypan Blue selectively stains dead cells with compromised membrane integrity.

- Protocol: Plant tissues are stained with a lactophenol-trypan blue solution, then destained in chloral hydrate solution or water. The blue-stained, dead cells surrounding the infection site can be observed and documented, providing a correlate for HR-PCD [36] [35].

Electrolyte Leakage Measurement

Electrolyte leakage is an early physiological response connected with PCD and ROS signaling, serving as an indicator of membrane damage.

- Protocol: Excised plant tissues (e.g., cotyledons) are placed in vials containing deionized water. The conductivity of the bathing solution is measured over time using a conductivity meter. An increase in electrolyte leakage from inoculated samples compared to mock-inoculated controls indicates membrane permeability changes, a hallmark of the defense response. Resistant genotypes often exhibit earlier induction of electrolyte leakage [35].

Real-Time H2O2 Detection with Genetically Encoded Sensors

The HyPer sensor is a genetically encoded, ratiometric fluorescent probe for the dynamic, real-time detection of intracellular H2O2.

- Principle: HyPer consists of a circularly permuted yellow fluorescent protein (cpYFP) inserted into the H2O2-sensing transcription factor OxyR from E. coli. Upon exposure to H2O2, OxyR undergoes a conformational change, altering the excitation spectrum of cpYFP. The ratio of fluorescence upon excitation at 500 nm versus 420 nm provides a quantitative measure of H2O2 levels, independent of sensor concentration [8].

- Protocol for Fungal Pathogens: The HyPer codon sequence was optimized for fungi like Neurospora crassa and Magnaporthe oryzae (creating MoHyPer) to ensure stable and robust expression. Transformed fungal conidia can be examined using confocal microscopy to visualize fluctuating H2O2 levels during key developmental stages like appressorium formation on artificial surfaces or during actual plant infection. Furthermore, H2O2 levels in conidia can be quantified in real-time using a fluorescent plate reader [8].

Gene Expression Analysis via qPCR

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) is used to analyze the expression patterns of key genes in ROS signaling pathways.

- Protocol: Total RNA is extracted from plant tissues at various time points after pathogen inoculation. After cDNA synthesis, qPCR is performed using primers for genes such as RBOHD (ROS production), MPK3 (MAPK signaling), and defense markers like PR-1. The differential onset patterns and expression levels of these genes are correlated with distinct levels of disease resistance (susceptible, intermediate, resistant) in the plant-pathogen system [36] [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents and Tools for ROS and Plant Defense Research

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| DAB (3,3'-Diaminobenzidine) | Histochemical detection of H2O2 in plant tissues [8] | High specificity for H2O2; produces a stable, insoluble brown polymer. |

| HyPer Sensor | Genetically encoded, ratiometric probe for real-time H2O2 detection [8] | Allows quantitative, dynamic imaging in live cells; codon-optimized versions available for different organisms. |

| H2DCFDA | Fluorescent dye for general ROS detection [8] | Cell-permeable; sensitive but less specific, can be photooxidized, and results can be influenced by esterase concentration. |

| Apoplastic Peroxidase Inhibitors (e.g., SHAM) | To dissect the relative contributions of different ROS sources [34] | Chemical inhibitors used to block specific enzymatic pathways. |

| NADPH Oxidase Inhibitors (e.g., DPI) | To inhibit the RBOH-dependent ROS generation pathway [34] | Helps in functionally characterizing the source of the oxidative burst. |

| Implantable H2O2 Microsensor | Continuous, in vivo monitoring of H2O2 levels in plants [6] | Emerging technology; can be integrated with self-powered systems for real-time, in-field analysis. |

Visualization of Experimental Workflow

The following diagram outlines a generalized experimental workflow for investigating the oxidative burst and its role in systemic immunity, integrating the protocols and tools described.

The journey from oxidative burst to systemic acquired resistance represents a sophisticated and highly regulated signaling cascade in plant immunity. The initial, localized production of ROS, particularly H2O2, serves as a critical trigger that orchestrates a multitude of downstream events, including the hypersensitive response, hormonal cross-talk, and the establishment of systemic resistance. Advancements in real-time detection technologies, such as genetically encoded sensors and implantable microsensors, are revolutionizing our ability to capture the precise spatiotemporal dynamics of H2O2 in planta. These tools are indispensable for researchers aiming to decode the complex language of plant defense signals, with the ultimate goals of enhancing crop resilience and developing novel plant protection strategies.

Advanced Tools for Real-Time H₂O₂ Monitoring: From Lab Benches to Field Deployment

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) have emerged as a transformative material in the field of nanotechnology, offering unparalleled advantages for chemical sensing and biological monitoring. Their unique physicochemical properties—including nanoscale dimensions, high surface-to-volume ratios, remarkable mechanical strength, and superior electrical and thermal conductivity—make them exceptionally suitable for developing highly sensitive and selective biosensors [38] [39]. In the context of plant sciences, CNT-based sensors represent a groundbreaking tool for decoding complex biological processes, particularly the real-time detection of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) signaling during plant-pathogen interactions [4].

The study of plant defense mechanisms is critical for addressing global challenges in food security and agricultural sustainability [38]. When plants encounter biotic stressors, such as pathogenic infections, they initiate a rapid signaling response. This often involves the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), with H₂O₂ acting as a key signaling molecule [40] [4]. Traditional methods for detecting H₂O₂ and other stress signals often require destructive sampling and lack temporal resolution, limiting our understanding of the dynamics of plant immune responses [4] [41]. CNT-based nanosensors overcome these limitations by enabling non-destructive, real-time, and in situ monitoring of H₂O₂ and other signaling molecules directly in living plants, providing unprecedented insights into the spatial and temporal dynamics of plant-pathogen interactions [4] [42].

This technical guide explores the fundamental principles, functionalization strategies, and experimental applications of CNT-based nanosensors, with a specific focus on their role in elucidating H₂O₂ signaling in plant defense systems. By integrating recent advancements and detailed methodologies, this document serves as a comprehensive resource for researchers and scientists engaged in plant pathology, sensor development, and agricultural biotechnology.

Fundamental Sensing Mechanisms of Carbon Nanotubes

The exceptional sensing capabilities of carbon nanotubes stem from their intrinsic electronic and optical properties, which are highly sensitive to surface interactions and environmental changes. The primary mechanisms exploited for chemical sensing can be categorized into electrical and optical transduction.

Electrical Sensing Mechanisms

CNTs exhibit excellent conductivity and high carrier mobility, making them ideal for electrical sensing applications. When target molecules, such as H₂O₂, adsorb onto the CNT surface, they induce measurable changes in electrical properties through several mechanisms [39]:

- Charge Transfer: Analyte molecules can act as electron donors or acceptors, transferring charge to or from the CNT. This shifts the Fermi level, modulating the conductivity of the CNT. A single molecule adsorption event can produce a significant and detectable change in resistance [39].

- Electrostatic Gating: Charged molecules near the CNT surface can create an electrostatic gating effect, analogous to the gate voltage in a field-effect transistor (FET). This alters the carrier density within the CNT channel, thereby modulating its conductance [39].

- Schottky Barrier Modulation: At the interface between a CNT and a metal electrode, a Schottky barrier exists. The adsorption of molecules at this interface can change the barrier height, affecting the overall current flow through the device [39].

Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs), with their well-defined semiconductor behavior and single conduction channel, are particularly advantageous for field-effect transistor (FET) configurations, which offer high sensitivity and rapid response for detecting various chemical species [39].

Optical Sensing Mechanisms

SWCNTs possess unique near-infrared (nIR) fluorescence properties that are highly sensitive to the local chemical environment. This forms the basis for optical nanosensors:

- Fluorescence Quenching: The nIR fluorescence of SWCNTs can be quenched (i.e., the intensity is reduced) upon interaction with specific analytes or through energy transfer mechanisms. This quenching effect can be used to detect the presence and concentration of target molecules [4].

- Corona Phase Molecular Recognition (CoPhMoRe): This pioneering approach involves wrapping SWCNTs with specific polymers or single-stranded DNA (ssDNA). The corona phase formed around the nanotube creates a selective binding pocket for target molecules. When a molecule like salicylic acid (SA) binds to this pocket, it causes a measurable change in the nIR fluorescence intensity of the SWCNT, enabling highly selective detection [4].

Table 1: Core Sensing Mechanisms of Carbon Nanotubes in Plant Science

| Sensing Type | Transduction Mechanism | Key Measurable Change | Primary CNT Form |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical | Charge Transfer | Change in electrical resistance/conductance | SWCNT, MWCNT |

| Field-Effect Transistor (FET) | Electrostatic Gating | Shift in threshold voltage/conductance | Primarily SWCNT |

| Electrochemical | Redox Reaction at Electrode | Change in current or potential | MWCNT, SWCNT mats |

| Optical | Fluorescence Quenching | Change in near-infrared fluorescence intensity | Primarily SWCNT |

| Optical | Corona Phase Molecular Recognition | Fluorescence modulation upon target binding | SWCNT with polymer/ssDNA wrapper |

Functionalization Strategies for Targeted H₂O₂ Sensing

Pristine CNTs often lack the selectivity required for specific detection of H₂O₂ in the complex milieu of plant tissues. Therefore, functionalization is a critical step to impart selectivity and enhance sensing performance. These strategies can be broadly classified as covalent or non-covalent.

Covalent Functionalization

Covalent functionalization involves forming chemical bonds between functional groups and the CNT sidewalls. While this can improve dispersibility, it may also disrupt the CNT's π-conjugated network, potentially altering its desirable electronic and optical properties [39]. For H₂O₂ sensing, enzymes like horseradish peroxidase (HRP) can be covalently immobilized on CNTs. HRP catalyzes the reduction of H₂O₂, and the subsequent electron transfer can be detected electrochemically via the CNT [42].

Non-Covalent Functionalization

Non-covalent functionalization preserves the intrinsic properties of CNTs and is widely used for optical sensors. It relies on π-π stacking, van der Waals forces, or electrostatic interactions to adsorb functional molecules onto the CNT surface.

- Polymer Wrapping: As utilized in the CoPhMoRe technique, wrapping SWCNTs with specific polymers creates a selective corona phase. While this was used to detect salicylic acid, the same principle can be applied to design sheaths that are sensitive to H₂O₂ or its reaction products [4].

- Nanocomposite Integration: CNTs can be integrated into hydrogels with other nanomaterials to create electrochemical sensors. For example, a reported wearable microneedle sensor uses a chitosan and reduced graphene oxide biohydrogel functionalized with HRP. The CNTs within this matrix facilitate electron transfer, enabling the detection of H₂O₂ through the enzymatic reaction [42].

Experimental Protocols for H₂O₂ Detection in Plants

This section details specific methodologies for deploying CNT-based sensors to monitor H₂O₂ in plant-pathogen interactions.

Protocol: Multiplexed Optical Nanosensor Detection

This protocol is adapted from studies that successfully decoded early stress signaling waves in plants using multiplexed nanosensors [4].

1. Sensor Synthesis and Functionalization:

- Materials: Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs), selective polymers for CoPhMoRe (e.g., for salicylic acid), DNA aptamers or other recognition elements for H₂O₂ sensing.

- Procedure:

- Disperse raw SWCNTs in an aqueous solution containing the specific polymer or DNA wrapper (e.g., 1 mg/mL SWCNT, 1 mg/mL polymer).

- Sonicate the mixture using a probe sonicator (e.g., 5 W, 30 min, on ice).

- Centrifuge the suspension (e.g., 16,000 × g, 30 min) to remove large aggregates and collect the stable supernatant containing wrapped SWCNTs.

2. Sensor Introduction into Plant Tissue:

- Method: Infiltration via syringe without needle. Gently press a 1 mL syringe containing the sensor solution against the abaxial (lower) side of a plant leaf. Apply gentle pressure to infiltrate a small section of the leaf mesophyll. The sensors are confined to the apoplastic space [4].

3. Real-Time Standoff Fluorescence Measurement:

- Setup: Excite the nanosensors with a near-infrared laser (e.g., 785 nm). Collect the fluorescence emission using an InGaAs (Indium Gallium Arsenide) array spectrometer.

- Data Acquisition: Monitor the fluorescence intensity of the sensors over time. Relate the intensity changes to the concentration of the target analyte (H₂O₂ or SA) by building a calibration curve with known standard solutions [4].

4. Data and Kinetic Modeling:

- The temporal data on H₂O₂ and SA concentrations can be fitted to a biochemical kinetic model to quantify signaling wave parameters, such as speed and amplitude, which are unique to different stress types [4].

Protocol: Wearable Microneedle Electrochemical Sensor

This protocol is based on a recently developed biohydrogel-enabled microneedle sensor for in situ monitoring of reactive oxygen species [42].

1. Fabrication of Microneedle Sensor Array:

- Materials: Chitosan, reduced graphene oxide, horseradish peroxidase (HRP), carbon nanotubes.

- Procedure:

- Prepare a biohydrogel by mixing chitosan, reduced graphene oxide, and HRP in an aqueous solution.

- Incorporate CNTs into the hydrogel matrix to enhance conductivity.

- Cast the nanocomposite hydrogel into a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) mold to form an array of microneedles.

- Cross-link the structure and integrate it with a portable potentiostat for electrochemical readings.

2. Sensor Deployment and Measurement:

- Attachment: Directly apply the microneedle patch to the surface of a plant leaf, allowing the microneedles to penetrate the cuticle and access the apoplast.

- Detection: Use amperometry (i.e., apply a constant potential and measure current) to detect H₂O₂. The HRP catalyzes the reduction of H₂O₂, generating an electrical current that is proportional to the H₂O₂ concentration. Results can be obtained in under a minute [42].

Table 2: Comparison of CNT-Based Sensor Deployment Methods for H₂O₂ Detection

| Parameter | Optical Nanosensor (Infiltration) | Wearable Microneedle Sensor |

|---|---|---|

| Sensing Principle | Near-infrared fluorescence modulation | Electrochemical (amperometric) |

| Spatial Resolution | High (can target specific tissue regions) | Localized to microneedle penetration sites |

| Temporal Resolution | Real-time (seconds to minutes) | Very fast (~1 minute) |

| Key Functional Material | Polymer/DNA-wrapped SWCNTs | HRP/CNT/Graphene Oxide Hydrogel |

| Plant Invasion Level | Minimally invasive (infiltration) | Minimally invasive (microneedles) |

| Primary Advantage | Multiplexing capability for multiple analytes | Portability, potential for field use |

| Key Challenge | Signal interpretation in complex tissue | Long-term stability and biofouling |

Signaling Pathways in Plant-Pathogen Interactions

The plant immune system involves a complex network of signaling pathways that are activated upon pathogen recognition. Hydrogen peroxide serves as a central node in this network. The following diagram illustrates the key signaling pathway decoded using CNT-based nanosensors.

H₂O₂ Signaling Pathway in Plant Defense

This pathway highlights the critical role of RbohD (Respiratory burst oxidase homolog D) and glutamate-receptor-like channels (GLR3.3 and GLR3.6) in propagating the wound-induced H₂O₂ wave, as revealed by real-time nanosensor measurements [40] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of CNT-based sensing for plant H₂O₂ detection relies on a suite of specialized materials and instruments.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for CNT-Based H₂O₂ Sensing

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs) | Core transducer material; provides fluorescence or conductivity changes. | Base material for all optical and electronic nanosensors. |

| Corona Phase Polymers / DNA Aptamers | Provides molecular recognition for specific analytes via CoPhMoRe. | Creating selective sensors for H₂O₂, salicylic acid, or other hormones. |

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) | Enzyme that catalytically reduces H₂O₂; enables electrochemical detection. | Functional element in wearable microneedle sensors. |

| Chitosan | Natural biopolymer; forms a biocompatible hydrogel matrix for sensors. | Base material for wearable microneedle sensor arrays. |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide | Enhances electron transfer and provides high surface area in composites. | Used in hydrogel nanocomposites to improve electrochemical sensitivity. |

| Near-Infrared (nIR) Spectrometer | Detects fluorescence emission from SWCNTs in the 900-1600 nm range. | Essential readout equipment for optical nanosensor experiments. |

| Portable Potentiostat | Measures electrochemical current or potential in miniaturized systems. | Readout device for wearable or field-deployable electrochemical sensors. |