Optimizing sgRNA Expression: Strategies for Maximizing CRISPR Mutation Efficiency

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing sgRNA expression to achieve higher CRISPR-Cas9 mutation rates.

Optimizing sgRNA Expression: Strategies for Maximizing CRISPR Mutation Efficiency

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing sgRNA expression to achieve higher CRISPR-Cas9 mutation rates. It covers foundational principles of sgRNA design and its impact on editing efficiency, explores advanced delivery methods like Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, and details practical strategies for troubleshooting common issues such as off-target effects. The content also outlines rigorous validation frameworks using tools like qPCR assays and computational predictions to compare sgRNA performance, integrating the latest research and methodologies to enable robust and efficient genome editing for both basic research and clinical applications.

The sgRNA Efficiency Blueprint: Core Principles for Maximizing On-Target Activity

Understanding the Link Between sgRNA Design and Mutation Efficiency

FAQs: sgRNA Design and Mutation Efficiency

Q1: What are the key factors in sgRNA design that directly impact mutation efficiency?

Several factors are crucial for designing an sgRNA that achieves high mutation efficiency. The most important is on-target efficiency, which predicts how effectively the guide RNA directs the Cas nuclease to edit the intended target site [1]. This is influenced by the specific 20-nucleotide targeting sequence and can be predicted using algorithms like Rule Set 3, CRISPRscan, or Lindel [1]. Furthermore, you must minimize off-target risks by ensuring your sgRNA sequence is unique within the genome, as sequences with significant homology to other genomic locations can lead to unintended mutations [1] [2]. The GC content of the sgRNA is also important, with an optimal range of 40-80% for stability [3]. Finally, the target must be immediately adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM); for the commonly used SpCas9, this is the sequence "NGG" [4] [1] [2].

Q2: Why might my sgRNA, which shows high INDEL rates in genotyping, fail to knock out the target protein?

This issue highlights the critical difference between mutation detection and functional knockout. High INDEL (Insertion/Deletion) rates detected by genotyping assays like PCR and sequencing do not guarantee that the resulting genetic changes create a premature stop codon or disrupt the protein's reading frame [5]. Some indels can be in-frame, leading to the production of a partially functional or altered protein. It is essential to validate knockout experiments at the protein level using techniques like Western blotting. Research has documented cases where edited cell pools exhibited 80% INDELs but retained target protein expression due to ineffective sgRNAs [5].

Q3: How can I improve my experiment when I observe low editing efficiency?

Low editing efficiency can be addressed by systematically optimizing several parameters:

- Verify Component Delivery: Use a transfection control (e.g., a fluorescent reporter) to confirm that your CRISPR components are successfully entering the cells [6].

- Use a Positive Control: Employ a validated, high-efficiency sgRNA (e.g., targeting human genes like TRAC or RELA) to determine if the problem is with your sgRNA design or your experimental workflow [6].

- Optimize sgRNA Format and Delivery: Chemically synthesized and modified (CSM) sgRNAs with enhanced stability can yield higher efficiency than in vitro transcribed (IVT) sgRNAs [5]. Also, optimize your delivery method (e.g., nucleofection) and parameters like cell-to-sgRNA ratio [5] [7].

- Check Cas9 Expression: Ensure your Cas9 is expressed at sufficient levels using a promoter that functions well in your specific cell type [7].

Q4: What is the most reliable way to predict the on-target efficiency of my sgRNA design?

Multiple algorithms exist, and their performance can vary. A study that systematically evaluated widely used gRNA scoring algorithms found that Benchling provided the most accurate predictions for their experimental setup [5]. However, the field commonly uses several tools that incorporate different models. For the most reliable design, it is advisable to consult multiple tools and prioritize sgRNAs that are consistently ranked highly across different platforms. Key algorithms and their bases are summarized in the table below.

Q5: Why do different sgRNAs targeting the same gene perform so differently?

Editing efficiency is highly influenced by the intrinsic properties of each unique sgRNA sequence, including its local genomic context and nucleotide composition [8]. This is why performance can vary substantially between sgRNAs for the same gene, with some showing little to no activity. To mitigate this variability and ensure robust results, it is recommended to design and test at least 3–4 sgRNAs per gene [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: High Off-Target Effects

Issue: Unintended mutations occur at genomic sites with sequence similarity to your sgRNA.

Solutions:

- Redesign Your sgRNA: Use design tools (e.g., CRISPick, CRISPOR) to perform a genome-wide analysis of potential off-target sites. Select an sgRNA with minimal homology to other genomic regions, especially those with fewer than three mismatches [1] [7].

- Employ High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Replace wild-type SpCas9 with engineered, high-fidelity versions such as eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, or HypaCas9, which are designed to reduce off-target cleavage [2].

- Use the Cas9 Nickase System: Utilize Cas9 nickase (Cas9n), which requires two adjacent sgRNAs to create a double-strand break, dramatically increasing specificity [4] [2].

- Validate with a Negative Control: Always include a negative control (e.g., cells treated with Cas9 only or a non-targeting "scramble" sgRNA) to establish a baseline for off-target effects in your specific experimental system [6].

Problem 2: Inconsistent or Low On-Target Mutation Efficiency

Issue: Desired mutations at the target site are not achieved or are inefficient.

Solutions:

- Verify sgRNA Design: Ensure your sgRNA has a high predicted on-target score using tools like CRISPick or GenScript's design tool, which use updated algorithms like Rule Set 3 [5] [1].

- Optimize sgRNA Stability and Format: Use chemically synthesized sgRNAs with specific chemical modifications (e.g., 2’-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate) on the ends to enhance stability within cells, which can boost efficiency [5].

- Optimize Transfection Protocol: Systematically refine delivery parameters. This includes determining cell tolerance to nucleofection stress, optimizing the cell-to-sgRNA ratio, and even considering repeated nucleofection to increase editing rates [5].

- Check Component Expression: Confirm that your Cas9 and sgRNA are being expressed effectively. Use a strong, cell-type-appropriate promoter and ensure your plasmid DNA or mRNA is of high quality and concentration [7].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key sgRNA On-Target Efficiency Scoring Algorithms

| Algorithm Name | Basis of Development | Key Application/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Rule Set 2 [1] | Knock-out efficiency data from 4,390 sgRNAs. | Used in CHOPCHOP, CRISPOR. Based on a gradient-boosted regression tree model. |

| Rule Set 3 [1] | Trained on 7 existing datasets of 47,000 gRNAs. | Used in GenScript, CRISPick. Considers the tracrRNA sequence for improved predictions. |

| CRISPRscan [1] | Activity data of 1,280 gRNAs validated in vivo in zebra fish. | Applied in CHOPCHOP, CRISPOR. |

| Lindel [1] | Profiled ~1.16 million mutation events from 6,872 synthetic targets. | Predicts frameshift ratio; generally more accurate for predicting indels. |

Table 2: Critical Parameters for Optimizing sgRNA Efficiency

| Parameter | Optimal Range or Condition | Impact on Mutation Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| GC Content [3] | 40% - 80% | Content outside this range can reduce sgRNA stability and binding efficiency. |

| sgRNA Length [3] | 17 - 23 nucleotides | Shorter lengths may reduce off-target effects but can compromise specificity if too short. |

| PAM Sequence [2] | NGG (for SpCas9) | The Cas9 nuclease will only bind and cleave if this short sequence is adjacent to the target site. |

| Nucleofection/Cell Ratio [5] | Optimized (e.g., 5μg sgRNA for 8x10^5 cells) | Systematically optimizing delivery parameters is critical for achieving >80% INDEL efficiency. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Rapid Workflow for Identifying Ineffective sgRNAs

This protocol integrates high-efficiency editing with rapid protein-level validation to quickly rule out sgRNAs that fail to produce a null phenotype [5].

- Cell Line Preparation: Use a human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC) line with a doxycycline-inducible spCas9 (iCas9) to allow controlled nuclease expression [5].

- sgRNA Delivery: Electroporate chemically synthesized and modified (CSM) sgRNAs into the iCas9 cell line using optimized nucleofection parameters (e.g., program CA137 on a Lonza 4D-Nucleofector) [5].

- Generate Edited Cell Pool: Culture transfected cells with doxycycline to induce Cas9 expression. Allow 5-7 days for editing and recovery, bypassing the need for single-cell cloning [5].

- Genomic DNA and Protein Extraction: Harvest a portion of the cell pool for genomic DNA extraction. Use the rest for protein lysate preparation.

- Dual Validation:

- Genotyping: Amplify the target region by PCR and analyze INDEL efficiency using Sanger sequencing and analysis tools like ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) or TIDE [5].

- Protein Analysis: Perform Western blotting on the cell pool lysates to detect the presence or absence of the target protein.

- Analysis: An sgRNA is deemed "ineffective" if the cell pool shows high INDEL percentages (e.g., >80%) but retains target protein expression in the Western blot [5].

Protocol 2: Systematic Optimization of Knockout Workflow

This detailed protocol outlines a comprehensive approach to achieve stable high-efficiency knockout in challenging cells like hPSCs [5].

- Cell Culture: Culture hPSCs (e.g., H9, H7 lines) in a suitable medium on Matrigel-coated plates. Passage cells at 80–90% confluency using 0.5 mM EDTA [5].

- sgRNA Design and Synthesis:

- Nucleofection Optimization:

- Cell Preparation: Dissociate cells with EDTA and pellet by centrifugation.

- Nucleofection: Combine the cell pellet with sgRNA (e.g., 5 μg for 8x10^5 cells) in a nucleofection buffer. Electroporate using the CA137 program on a Lonza 4D-Nucleofector [5].

- Repeated Nucleofection: To boost efficiency, perform a second nucleofection with the same sgRNA 3 days after the first [5].

- Cell Recovery and Expansion: After transfection, recover cells in optimized culture medium. Allow cells to expand for genotyping and analysis.

- Efficiency Analysis: Extract genomic DNA. Amplify the target locus by PCR and submit for Sanger sequencing. Quantify editing efficiency using the ICE or TIDE algorithm [5].

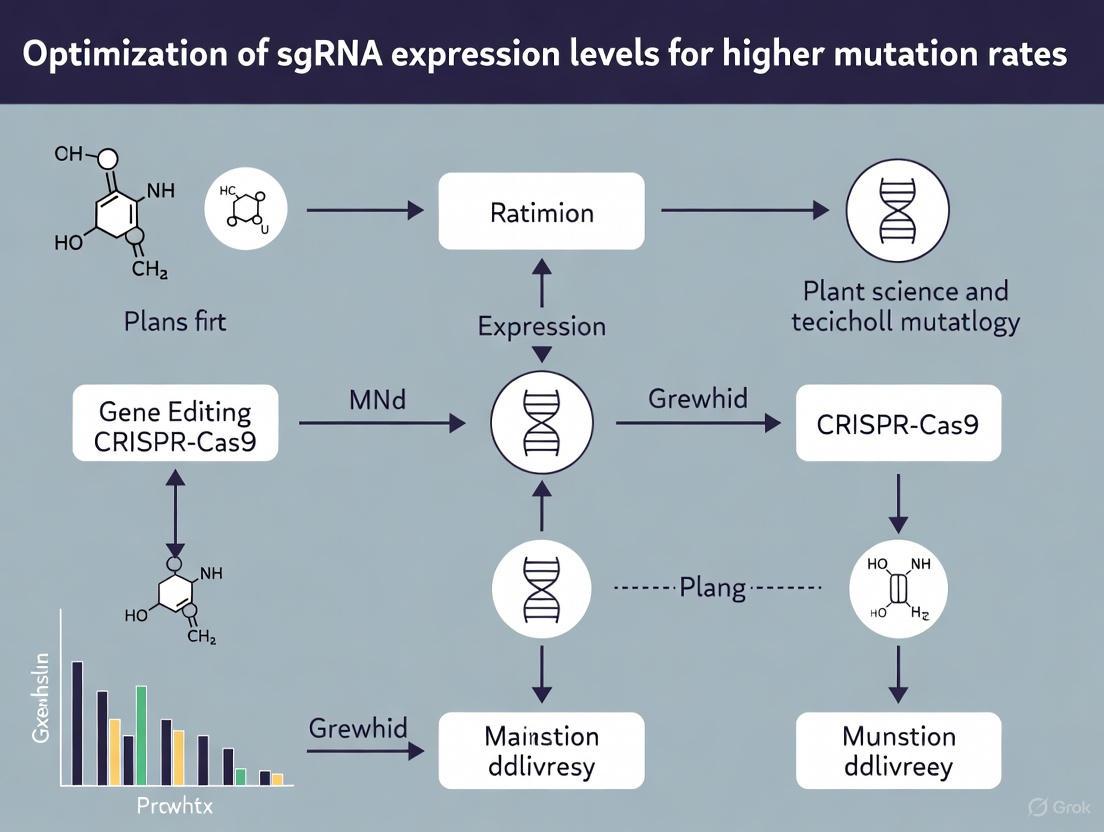

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

sgRNA Design Workflow

Optimization Parameters Relationship

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Optimized sgRNA Workflows

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Chemically Modified sgRNA [5] | Synthetic sgRNA with stability-enhancing modifications (e.g., 2’-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate). | Improves resistance to nucleases, leading to higher editing efficiency compared to standard IVT-sgRNA. |

| Inducible Cas9 Cell Line [5] | A cell line (e.g., hPSCs-iCas9) with a doxycycline-inducible Cas9 gene integrated into a safe-harbor locus (e.g., AAVS1). | Allows tunable nuclease expression, reducing cell toxicity and enabling controlled timing of editing. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants [2] | Engineered Cas9 proteins (e.g., eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, HypaCas9). | Designed to minimize off-target effects while maintaining robust on-target activity. |

| Validated Positive Control sgRNA [6] | A pre-verified sgRNA targeting a standard locus (e.g., human TRAC, RELA, or mouse ROSA26). | Essential for optimizing transfection/delivery conditions and confirming system functionality. |

| Nucleofection System & Kits [5] | Electroporation-based delivery systems (e.g., Lonza 4D-Nucleofector) with cell-type-specific kits. | Critical for efficient delivery of CRISPR components into hard-to-transfect cells like stem cells. |

| ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) Software [5] | A free, online bioinformatics tool from Synthego. | Analyzes Sanger sequencing data from edited cell pools to accurately quantify INDEL efficiency. |

FAQs: Core Principles of sgRNA Design

1. What are the most critical sequence-based factors that determine sgRNA on-target activity? The on-target activity of a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) is primarily governed by the sequence composition of its 20-nucleotide targeting region and the adjacent Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM). Key factors include the GC content, particularly in the PAM-proximal region, and the specific nucleotide positions. Research has demonstrated a strong positive correlation between mutagenesis efficiency and the GC content of the six nucleotides closest to the PAM (PAM-proximal nucleotides, or PAMPNs) [9]. Furthermore, the sequence context must enable optimal interaction with the Cas9 protein, and the chosen target should be unique within the genome to minimize off-target effects [2] [10].

2. How does GC content specifically influence sgRNA efficiency? GC content influences the binding stability between the sgRNA and the target DNA. While very low GC content may result in weak binding, very high GC content can promote off-target binding. The most crucial parameter is the local GC content in the "seed" region—the 8-12 bases closest to the PAM sequence. One systematic study in Drosophila melanogaster established that the GC content of the six PAMPNs is a key determinant of efficiency [9]. This region is critical for the initial recognition and binding of the Cas9 complex.

3. Beyond sequence composition, what other parameters should I optimize for high mutation rates? While sequence composition is fundamental, other parameters are crucial for achieving high mutation rates, especially in complex systems like human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs). These include [5]:

- sgRNA Format and Stability: Using chemically synthesized and modified sgRNAs (CSM-sgRNAs) with protective groups (e.g., 2'-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate) can significantly enhance stability and performance compared to in vitro transcribed (IVT) sgRNAs.

- Delivery and Dosage: Optimizing the cell-to-sgRNA ratio and the total amount of sgRNA delivered is critical. Furthermore, a repeated nucleofection protocol can dramatically increase INDEL (insertion/deletion) efficiency.

- Cas9 Variant: The choice of Cas9 variant (e.g., wild-type SpCas9, high-fidelity eSpCas9(1.1), or HypaCas9) impacts both efficiency and specificity [11]. Your experimental goal (maximizing on-target vs. minimizing off-target) will guide this choice.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common sgRNA Activity Problems

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution & Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low Editing Efficiency | Suboptimal GC content in seed region [9] | Redesign sgRNA to have a GC content of 40-80%, paying particular attention to the PAM-proximal region. |

| Use of unmodified IVT-sgRNA [5] | Switch to chemically synthesized and modified (CSM) sgRNAs to improve stability and half-life. | |

| Inefficient delivery or low dosage [5] | Optimize transfection protocol; increase sgRNA concentration or perform repeated nucleofection. | |

| High Off-Target Effects | sgRNA sequence has high homology to multiple genomic sites [2] | Use tools like Benchling or CCTop to screen for unique targets; avoid sequences with <3 mismatches to other genomic loci [9]. |

| Use of standard-fidelity Cas9 [2] | Use a high-fidelity Cas9 variant (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9, HypaCas9) to reduce off-target cleavage. | |

| Ineffective Knockout (Protein persists) | sgRNA targets an exon near the protein's terminus [12] | Redesign sgRNAs to target crucial exons near the 5' end or central domains of the protein to ensure complete disruption. |

| In-frame indels not disrupting the reading frame [5] | Use multiple sgRNAs targeting the same gene to increase the likelihood of a frameshift mutation and large deletions. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Validating sgRNA On-Target Activity in hPSCs

This optimized protocol for human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) can achieve INDEL efficiencies over 80% [5].

- sgRNA Design: Design sgRNAs targeting a common exon of your gene of interest using a design tool (e.g., Benchling, CCTop). Prioritize sgRNAs with high on-target prediction scores.

- sgRNA Synthesis: Opt for chemically synthesized and modified (CSM) sgRNAs with 2'-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications at both ends to enhance nuclease resistance.

- Cell Preparation: Culture hPSCs containing a doxycycline-inducible Cas9 (iCas9) system. Dissociate cells into single cells using EDTA.

- Nucleofection:

- Combine 5 µg of CSM-sgRNA with the cell pellet (8 x 10^5 cells) and nucleofection buffer.

- Electroporate using the CA137 program on a 4D-Nucleofector.

- Repeat Transfection: Three days after the first nucleofection, repeat the nucleofection process using the same parameters.

- Analysis: Harvest cells 3-5 days post-transfection. Extract genomic DNA and amplify the target region by PCR. Analyze INDEL efficiency using T7E1 assay or deep sequencing. For critical applications, validate protein knockout via Western blot.

Protocol 2: Systematically Testing GC Content Impact

This method is derived from foundational research linking GC content to efficiency [9].

- sgRNA Selection: For a single target gene, design a series of sgRNAs (e.g., 5-10) that span a wide range of total GC content (e.g., 20% to 80%).

- PAM-Proximal GC Calculation: For each sgRNA, calculate the GC content specifically for the 6 nucleotides adjacent to the PAM sequence.

- Experimental Testing: Test all sgRNAs in your model system (e.g., Drosophila embryo injection, cultured cells) using a standardized delivery method and constant Cas9 expression level.

- Efficiency Quantification: Measure the mutagenesis rate for each sgRNA (e.g., via flow cytometry, phenotypic screening, or deep sequencing).

- Correlation Analysis: Plot the calculated GC content (both total and PAM-proximal) against the measured mutagenesis efficiency to establish a correlation specific to your experimental system.

Quantitative Data on Sequence Features and Efficiency

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from sgRNA Optimization Studies

| Feature | Impact on On-Target Activity | Experimental Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAM-Proximal GC (6 nucleotides) | Strong positive correlation with mutagenesis efficiency | Drosophila melanogaster injection | [9] |

| Seed Region Mismatches | Mismatches in the 8-10 bases at the 3' end of the gRNA spacer most disruptive to cleavage | Specificity studies in mammalian cells | [2] |

| Number of Mismatches | Three or more mismatches anywhere in the sgRNA sequence prevented heritable mutations | Tested with 104 sgRNAs in Drosophila | [9] |

| Truncated sgRNA (17-18 nt) | Can reduce off-target effects while retaining similar on-target efficiency as 20-nt sgRNAs | Specificity optimization | [9] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Optimizing sgRNA On-Target Activity

| Reagent / Tool | Function & Utility in Optimization | Example Products / Software |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants | Engineered Cas9 proteins with reduced off-target effects while maintaining high on-target activity. Essential for therapeutic applications. | eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, HypaCas9 [11] [2] |

| Chemically Modified sgRNA | Synthetic sgRNAs with chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate) that increase stability and resistance to nucleases, boosting editing efficiency [5]. | Commercially synthesized from providers like GenScript. |

| gRNA Design Software | Online platforms that predict on-target efficiency and potential off-target sites by integrating scoring rules (e.g., Doench rules) and up-to-date genome annotations. | Benchling, CCTop, CHOP-CHOP, CRISPR Direct [5] [12] [10] |

| Inducible Cas9 System | A cell line (e.g., hPSCs-iCas9) where Cas9 expression is controlled by an inducer (e.g., doxycycline). Allows for temporal control, minimizing toxicity and improving editing efficiency [5]. | Commercially available or generated via stable integration at safe-harbor loci like AAVS1. |

Workflow: From sgRNA Design to Validation

The following diagram summarizes the key steps and decision points for designing and validating a high-activity sgRNA.

The Critical Role of the Seed Sequence and PAM Recognition

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the PAM and seed sequence, and why are they critical for CRISPR experiment success? The Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) is a short, specific DNA sequence (usually 2-6 base pairs) that follows the DNA region targeted for cleavage by the CRISPR-Cas system. It is absolutely required for the Cas nuclease to recognize and bind to the target site [13]. The seed sequence is the PAM-proximal region of the sgRNA spacer sequence, typically the 3' half, which is crucial for initial DNA binding and is highly sensitive to mismatches [14]. These elements are critical because the PAM allows the CRISPR system to distinguish between foreign viral DNA and the bacterium's own DNA, preventing autoimmunity [13]. In experiments, the absence of the correct PAM will prevent editing entirely, while imperfections in the seed sequence are a major cause of off-target effects [14].

My CRISPR experiment has low editing efficiency even though my sgRNA has a high predicted score. What could be wrong? Low editing efficiency can stem from several factors related to PAM and seed sequence context:

- Inefficient PAM Recognition: Even if an NGG PAM for SpCas9 is present, its sequence context can affect binding efficiency. Some PAMs are recognized less efficiently than others [13].

- Chromatin Inaccessibility: The target site, including the PAM and seed region, might be in a densely packed chromatin region that is inaccessible to the Cas complex [15].

- sgRNA Design: The sgRNA itself might be ineffective despite a high prediction score. One study found that an sgRNA targeting exon 2 of ACE2 induced 80% INDELs but failed to knock out protein expression, highlighting the need for experimental validation [5].

- Delivery and Stability: The sgRNA may have poor stability within the cells. Using chemically synthesized and modified sgRNAs (CSM-sgRNA) with 2’-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications on both ends can enhance stability and improve results [5].

I suspect off-target activity in my CRISPRi experiment. How is this related to the seed sequence? Off-target effects in CRISPRi are more common than previously known and are primarily driven by the seed sequence [14]. The Cas9-sgRNA complex can bind to genomic sites with significant complementarity to the seed sequence, even if the rest of the sgRNA spacer has mismatches. This off-target binding can cause both direct and extensive secondary changes in the transcriptome. The length of the effective seed sequence and its tolerance for mismatches can vary across different sgRNAs, making careful data interpretation essential for single-gene studies [14].

The genomic region I want to edit does not have a PAM sequence for SpCas9. What are my options? You are not limited to the commonly used SpCas9 (which requires a 5'-NGG-3' PAM). Your options include:

- Using Alternative Cas Nucleases: Numerous Cas proteins from different bacterial species recognize distinct PAM sequences [13]. For instance, Cas12a (Cpf1) recognizes a T-rich PAM (TTTV), and SaCas9 recognizes NNGRRT [13].

- Using Engineered Cas Variants: SpCas9 has been engineered to recognize novel PAM sequences other than NGG. For example, high-fidelity variants like hfCas12Max recognize short PAMs like TN and/or TNN [13].

- Considering TALENs: As an alternative technology, Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) do not require a PAM sequence and can be designed for a broader range of sites [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Consistently Low On-Target Mutation Rates

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Problem Area | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Supporting Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAM Availability | Target locus lacks a high-efficiency PAM for your chosen nuclease. | Switch to a Cas nuclease ortholog or engineered variant with a PAM that is present at your target site. | A study achieved 82-93% INDEL efficiency by systematically optimizing parameters, including nuclease choice [5]. |

| sgRNA Design | The sgRNA has low intrinsic cleavage activity, despite targeting a region with a PAM. | Use multiple algorithms (e.g., Benchling was found most accurate in one study) to design sgRNAs and select one with a high predicted score. Validate sgRNA activity with a cleavage detection assay (e.g., T7EI) before full-scale experiments [5]. | Benchling provided the most accurate predictions compared to other algorithms in a knockout efficiency study [5]. |

| sgRNA Integrity | Degradation of in vitro transcribed sgRNA (IVT-sgRNA) before or after delivery. | Use chemically synthesized and modified sgRNAs (CSM-sgRNA) with stability-enhancing modifications to resist cellular degradation [5]. | Chemically modified sgRNAs (CSM-sgRNA) harbor 2’-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications on both ends to enhance stability [5]. |

| Delivery & Dosage | Suboptimal ratio of Cas9 to sgRNA in target cells or low transfection efficiency. | Optimize the cell-to-sgRNA ratio and nucleofection conditions. Using a Dox-inducible Cas9 system (iCas9) can ensure nuclease expression is tuned for high efficiency [5]. | Using 5 μg of sgRNA for 8×10⁵ cells and repeated nucleofection 3 days after the first transfection significantly boosted editing rates [5]. |

Problem: High Off-Target Mutation Rates

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Problem Area | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Supporting Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seed Sequence Specificity | The sgRNA's seed sequence has high complementarity to multiple genomic sites. | Design sgRNAs with unique seed sequences. Use online tools to scan the genome for potential off-target sites with complementarity, especially in the PAM-proximal seed region [14]. | Off-target activity in CRISPRi is primarily accounted for by complementarity of the PAM-proximal genomic sequence with the 3' half of the sgRNA spacer (the seed sequence) [14]. |

| Nuclease Choice | The Cas9 protein has high catalytic activity but lower fidelity. | Switch to high-fidelity Cas variants (e.g., hfCas12Max, SpCas9-HF1) that are engineered to reduce off-target cleavage while maintaining on-target activity [13]. | Engineered high-fidelity variants like hfCas12Max are designed to minimize off-target cutting [13]. |

| Complex Stoichiometry | Prolonged expression of Cas9 and sgRNA from plasmids increases the window for off-target events. | Deliver the CRISPR machinery as a pre-assembled Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. The transient activity of RNPs drastically reduces off-target effects [16]. | Using CRISPR Cas9 ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) for arrayed perturbations resulted in high editing efficiency and specific network mapping [16]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating sgRNA On-Target Activity Using the T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) Assay

This protocol allows for rapid and inexpensive detection of CRISPR-induced mutations at a specific genomic locus.

1. Transfect Cells: Introduce your CRISPR components (e.g., RNP, plasmid) into your target cells using optimized nucleofection or transfection methods [5].

2. Harvest Genomic DNA: 48-72 hours post-transfection, harvest cells and extract genomic DNA using a standard purification kit.

3. PCR Amplification: Design primers that flank your target site and amplify a 400-800 bp PCR product encompassing the edited region.

4. Denature and Anneal: Purify the PCR product. In a thermal cycler, denature the DNA (95°C for 10 min) and then slowly reanneal it (ramp down to 25°C over 45 min). This allows the formation of heteroduplex DNA (mismatched duplexes from INDELs) alongside homoduplex DNA.

5. T7EI Digestion: Digest the reannealed DNA with the T7 Endonuclease I enzyme, which cleaves at heteroduplex structures.

6. Gel Electrophoresis: Run the digested products on an agarose gel. A successful edit will show cleaved bands in addition to the full-length PCR product.

7. Analysis: Use software like ImageJ to measure the gray values of the bands. The INDEL percentage can be calculated as follows:

INDEL % = 100 × (1 - sqrt(1 - (b + c)/(a + b + c)))

where a is the integrated intensity of the undigested PCR product band, and b and c are the intensities of the cleavage products [5].

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Evaluation of Novel Nuclease Activity and PAM Specificity

This method, adapted from Synthego's Halo Platform and Paragon Genomics' CleanPlex technology, allows for direct comparison of editing activity between different nucleases [13].

1. Design and Synthesis: Design a library of sgRNAs targeting various genomic sites with diverse PAM contexts. Synthesize the sgRNA library at high throughput. 2. Parallel Transfection: Electroporate the sgRNA library, along with the novel nuclease(s) of interest, into a stable Cas-expressing cell line (e.g., hPSCs-iCas9) using automated platforms for consistency. 3. Amplicon Sequencing: Harvest genomic DNA, then use a multiplexed PCR approach (e.g., CleanPlex) to amplify all targeted loci in a single reaction for next-generation sequencing. 4. Data Analysis: Sequence the amplicons and use a specialized algorithm (e.g., Synthego's ICE or TIDE) to analyze the sequencing chromatograms and calculate the INDEL efficiency at each target site for each nuclease [5]. This enables a side-by-side comparison of nuclease activity and PAM preference.

Visualizing PAM and Seed Sequence Mechanisms

The following diagram illustrates the key components of CRISPR-Cas9 target recognition, highlighting the spatial relationship between the PAM, seed sequence, and the Cas9-sgRNA complex.

CRISPR-Cas9 Target Recognition

This workflow outlines the key steps for setting up and analyzing a CRISPR knockout experiment, from initial design to validation.

CRISPR Knockout Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 (S. pyogenes) | The most common Cas nuclease; requires a 5'-NGG-3' PAM. | A versatile starting point; many engineered variants are derived from it [13]. |

| High-Fidelity Cas Variants (e.g., hfCas12Max) | Engineered nucleases with reduced off-target effects; often recognize different PAMs. | Crucial for therapeutic applications and sensitive functional genomics screens [13]. |

| Alternative Cas Orthologs (e.g., SaCas9, NmeCas9) | Cas proteins from other bacterial species with distinct PAM requirements. | Expands the range of targetable genomic sites [13] [17]. |

| Chemically Modified sgRNA (CSM-sgRNA) | sgRNAs with synthetic modifications (e.g., 2’-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate) to enhance cellular stability. | Improves editing efficiency and consistency by resisting degradation [5]. |

| Invitrogen GeneArt Genomic Cleavage Detection Kit | A commercial kit for detecting CRISPR-induced cleavage events. | Provides a standardized protocol and reagents for assays like the T7EI assay [15]. |

| dCas9 (Catalytically Dead Cas9) | A Cas9 that binds DNA but does not cut it; fused to fluorescent proteins for imaging. | Used in multicolor CRISPR labeling to visualize genomic loci in live cells [17]. |

Impact of Chromatin Accessibility and Epigenetic Landscape on sgRNA Efficiency

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Fundamental Mechanisms

1. How does chromatin accessibility directly influence sgRNA efficiency? Chromatin accessibility determines the physical accessibility of the DNA to the CRISPR-Cas complex. When DNA is tightly packed into closed chromatin (heterochromatin), characterized by specific histone marks and DNA methylation, the Cas9-sgRNA complex cannot easily bind to its target site, leading to significantly reduced editing efficiency. Conversely, open chromatin (euchromatin) regions are more accessible, allowing for efficient binding and higher mutation rates [18] [19].

2. Which specific epigenetic modifications are known to hinder sgRNA activity? Certain histone modifications create a repressive chromatin environment. These include:

- Histone methylation: Such as H3K9me3 and H3K27me3, which are associated with gene silencing and tightly packed DNA [19].

- DNA methylation: High levels of cytosine methylation (5mC) in CpG islands can directly block sgRNA binding and are a hallmark of transcriptionally inactive regions [19].

3. My sgRNA has high predicted on-target scores in silico, but editing efficiency is low in my cell line. Why? This common issue often arises from cell-type-specific epigenetic landscapes. The chromatin in your target region may be closed or repressed in your specific cell type, even if the sequence is perfectly targetable. In silico tools that do not incorporate epigenetic data from your specific experimental model cannot account for this critical variable [18].

Troubleshooting and Optimization

4. What strategies can I use to improve sgRNA efficiency in epigenetically repressed regions? You can employ several experimental strategies to overcome epigenetic barriers:

- Select targets using epigenetic data: Consult public databases (e.g., ENCODE, Roadmap Epigenomics) for histone modification ChIP-seq or ATAC-seq data from your cell type or a similar one to choose targets in open chromatin [19].

- Use chromatin-modulating agents: Treat cells with small-molecule inhibitors of epigenetic regulators prior to or during editing.

- DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (e.g., 5-Azacytidine) can reduce DNA methylation.

- Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors (e.g., Sodium Butyrate, Trichostatin A) can promote a more open chromatin state [19].

- Opt for advanced CRISPR systems: Consider using high-fidelity Cas9 variants or Cas9-minimized (miniCas9) systems, which may have different steric requirements for binding [18] [20].

5. Are there computational tools that incorporate epigenetic data for sgRNA design? Yes, next-generation bioinformatics tools are increasingly integrating epigenetic features to improve prediction accuracy. For example:

- GuideScan2 provides insights into genome accessibility and chromatin data to verify the biological significance of target sites [18].

- Deep learning models are being trained on large datasets that include chromatin features to infer more accurate on-target and off-target scores [18] [21].

6. How can I experimentally map the chromatin state of my target locus? To directly assess the chromatin environment in your specific cell model, you can use:

- ATAC-seq (Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with sequencing): Identifies genome-wide regions of open chromatin.

- ChIP-seq (Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing): Maps the binding sites of specific histone modifications (e.g., H3K27ac for active enhancers, H3K9me3 for heterochromatin) or chromatin-associated proteins [19].

Experimental Protocols for Epigenetic Analysis in CRISPR Workflows

Protocol 1: Mapping Chromatin Accessibility with ATAC-seq

Purpose: To identify open and closed chromatin regions in your cell sample, informing optimal sgRNA target selection.

Materials:

- Cells of interest (500,000 - 1,000,000 cells per replicate)

- ATAC-seq Kit (commercially available)

- Tagmentase enzyme (e.g., Tn5 transposase)

- DNA Cleanup Beads (e.g., SPRI beads)

- Qubit Fluorometer and dsDNA HS Assay Kit

- Bioanalyzer or TapeStation

- Reagents for PCR amplification and library quantification

- Sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina)

Method:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest cells and wash with cold PBS. Lyse cells to isolate nuclei (for nucleated cells). Keep samples on ice.

- Tagmentation: Resuspend nuclei in tagmentation reaction mix containing the Tn5 transposase. Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes to fragment accessible DNA.

- DNA Cleanup: Purify the tagmented DNA using DNA Cleanup Beads to remove enzymes and buffers.

- Library Amplification: Amplify the purified DNA with barcoded PCR primers for 10-12 cycles to create the sequencing library.

- Library Purification & QC: Clean up the PCR product with beads. Quantify the library using Qubit and check fragment size distribution on a Bioanalyzer.

- Sequencing: Pool libraries and sequence on an appropriate Illumina platform (e.g., Novaseq, 150bp paired-end recommended).

Data Analysis:

- Process raw sequencing reads (adapter trimming, quality control).

- Align reads to the reference genome.

- Call peaks to identify regions of significant chromatin accessibility.

- Visualize data in a genome browser alongside your sgRNA target sites.

Protocol 2: Modulating Chromatin State with Small Molecules

Purpose: To transiently open the chromatin landscape and improve sgRNA access to a refractory target site.

Materials:

- Cell culture for your experiment

- Epigenetic inhibitors (e.g., 5-Azacytidine for DNA methylation, Trichostatin A for histone acetylation)

- Appropriate cell culture media and reagents

- CRISPR editing components (RNP or plasmid)

Method:

- Dose Optimization: Perform a dose-response curve to determine a non-toxic but effective concentration of the inhibitor for your cell type.

- Pre-treatment: Treat cells with the selected inhibitor for 24-48 hours before delivering the CRISPR components.

- CRISPR Delivery: Perform your standard transfection or electroporation protocol to deliver Cas9 and sgRNA.

- Post-treatment: Maintain cells in medium with or without the inhibitor for an additional 24-48 hours post-editing.

- Analysis: Harvest cells and assess editing efficiency (e.g., via T7E1 assay, NGS) and compare to untreated controls.

Data Presentation Tables

Table 1: Epigenetic Modifications and Their Impact on sgRNA Efficiency

| Epigenetic Mark | Association with Chromatin State | Expected Impact on sgRNA Efficiency | Potential Remedial Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| H3K4me3 | Active Promoters | High (Favorable) | - |

| H3K27ac | Active Enhancers/Promoters | High (Favorable) | - |

| H3K9me3 | Facultative Heterochromatin | Low (Unfavorable) | HDAC inhibitor treatment |

| H3K27me3 | Constitutive Heterochromatin | Low (Unfavorable) | EZH2 (PRC2) inhibitor treatment |

| DNA Methylation (5mC) | Transcriptional Repression | Low (Unfavorable) | DNMT inhibitor (e.g., 5-Azacytidine) |

| High GC Content | Stable DNA-RNA Hybrids | Variable (Can be favorable but may cause misfolding) [18] | Optimize sgRNA length/sequence [18] |

Table 2: Comparison of Chromatin Profiling Methods

| Method | Profiles | Resolution | Required Input | Primary Application in CRISPR Optimization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATAC-seq | Open Chromatin | Single-nucleotide | 500 - 50,000 cells | Genome-wide identification of accessible regions for sgRNA targeting. |

| ChIP-seq | Specific histone modifications (e.g., H3K27me3) | ~200 bp | 1 - 10 million cells | Determining the repressive or active state of a specific genomic locus of interest. |

| DNase-seq | Open Chromatin | ~100 bp | 1 - 50 million cells | Similar to ATAC-seq; historical standard for mapping DHSs (DNase I Hypersensitive Sites). |

| MNase-seq | Nucleosome Positioning | Single-nucleotide | 1 - 10 million cells | Mapping precise nucleosome positions that can physically block sgRNA access. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Investigating Chromatin and sgRNA Interactions

| Research Reagent | Function/Description | Application in This Context |

|---|---|---|

| Tn5 Transposase | Enzyme that simultaneously fragments and tags accessible genomic DNA. | Essential for ATAC-seq library preparation to map open chromatin [19]. |

| HDAC Inhibitors (e.g., Trichostatin A) | Small molecules that inhibit histone deacetylases, leading to increased histone acetylation and open chromatin. | Used as a pre-treatment to experimentally open chromatin and test if it rescues low sgRNA efficiency [19]. |

| DNMT Inhibitors (e.g., 5-Azacytidine) | Small molecules that inhibit DNA methyltransferases, leading to global DNA hypomethylation. | Used to de-repress epigenetically silenced regions and improve CRISPR access [19]. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 (e.g., SpCas9-HF1) | Engineered Cas9 variants with reduced off-target effects and potentially altered binding dynamics. | Can provide more precise editing and may perform differently in challenging chromatin contexts compared to wild-type SpCas9 [18]. |

| dCas9-Epigenetic Modulators | Catalytically dead Cas9 fused to writer/eraser domains (e.g., dCas9-p300 for acetylation). | Can be targeted with a sgRNA to actively open the chromatin at a specific locus before introducing the cutting Cas9, a strategy known as "chromatin priming" [19]. |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Diagram 1: Chromatin Impact on CRISPR Workflow

Diagram 2: Chromatin Troubleshooting Pathways

Advanced Delivery and Expression Systems for Enhanced sgRNA Performance

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary advantages of using synthetic sgRNA in RNP complexes over plasmid-based delivery?

Synthetic sgRNA, produced via solid-phase chemical synthesis, offers several key benefits for RNP delivery [3]:

- Reduced Off-Target Effects: Unlike plasmid-based expression which can lead to prolonged Cas9 activity in cells, synthetic sgRNA in RNPs degrades quickly, shortening the editing window and minimizing off-target cleavage [3] [22].

- Higher Editing Efficiency: Synthetic sgRNA is of high purity and does not require the cell's transcription machinery, leading to more immediate and efficient editing [3].

- Lower Cytotoxicity: The RNP complex avoids the need for transcriptional machinery and prevents potential genomic integration of plasmid DNA, which can cause cell stress and death [7] [3].

- Rapid Workflow: Using synthetic sgRNA bypasses the time-consuming steps of cloning (1-2 weeks) or in vitro transcription (1-3 days), accelerating experimental timelines [3].

FAQ 2: Why is my RNP delivery resulting in low editing efficiency, and how can I improve it?

Low efficiency with RNP delivery can stem from several factors. The table below outlines common issues and evidence-based solutions.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Troubleshooting Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Low Editing Efficiency | Inefficient delivery of RNP into cells [7]. | Optimize transfection method (e.g., electroporation parameters for your cell type). Use Cas9 protein with a nuclear localization signal (NLS) to enhance nuclear import [7]. |

| Low Editing Efficiency | Poor stability or activity of the sgRNA [5]. | Use chemically synthesized and modified (CSM) sgRNA with stability-enhancing modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate on the 5' and 3' ends) [5]. |

| Cell Toxicity/Death | High concentrations of delivered RNP complexes [7]. | Titrate the concentration of RNP complexes. Start with lower doses and gradually increase to find a balance between editing efficiency and cell viability [7]. |

| Inability to Detect Edits | Inadequate genotyping methods [7]. | Employ robust, sensitive detection methods such as T7 endonuclease I assay, Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE), or Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) on Sanger sequencing data [5] [7]. |

FAQ 3: How can I minimize off-target effects when using the RNP delivery method?

Minimizing off-target effects requires a multi-faceted approach focused on sgRNA design and Cas9 protein engineering [22].

- Refine sgRNA Design: Carefully design your sgRNA using computational tools (e.g., CHOPCHOP, Synthego's tool) to predict and avoid off-target sites. Strategies include:

- Truncated sgRNAs: Using 5'-end truncated sgRNAs (17-19 nucleotides instead of 20) can increase binding stringency and reduce off-target mutations without compromising on-target efficiency [22].

- DNA-RNA Chimeras: Replacing segments of the crRNA with DNA nucleotides has been shown to reduce off-target effects while being more cost-effective [22].

- Use High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants: Employ engineered Cas9 variants like eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1, or HiFi Cas9, which are designed to reduce off-target cleavage by altering interactions with the DNA backbone [7] [22].

- Control Concentration: The transient nature of RNP complexes is advantageous. Using the lowest effective concentration of RNP further reduces the risk of off-target activity [7].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Persistent Low Editing Efficiency Across Multiple Cell Lines

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol for Optimization:

Validate sgRNA Activity:

- Design: Use multiple sgRNAs (2-3) per target gene designed with a reputable algorithm (e.g., Benchling, CHOPCHOP). Aim for a GC content between 40-80% [5] [3].

- Synthesis: Utilize chemically synthesized, modified (CSM) sgRNAs for enhanced stability and consistency [5].

- Verify Cleavage Efficiency: Perform an in vitro cleavage assay by incubating the RNP complex with a purified DNA fragment containing the target site. Analyze the cleavage products via gel electrophoresis to confirm sgRNA functionality before proceeding to cell experiments.

Optimize RNP Complex Assembly and Delivery:

- Assembly: Pre-complex the synthetic sgRNA and Cas9 protein in a molar ratio (e.g., 1:1.2 Cas9:sgRNA) in an appropriate buffer. Incubate at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to form active RNP complexes.

- Delivery: For hard-to-transfect cells, use electroporation. Systematically optimize program parameters and cell-specific buffers. A suggested workflow for this optimization is detailed in the diagram below.

- Enrich for Edited Cells:

- If working with a mixed population, consider strategies to enrich for edited cells. For example, when introducing a point mutation, design the edit to eliminate the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) site. This prevents the Cas9-sgRNA complex from re-cutting the successfully edited allele, thereby enriching the population for desired mutants [5].

Problem: High Cell Toxicity Following RNP Electroporation

Detailed Methodology to Mitigate Toxicity:

Titrate RNP Components:

- Prepare a dilution series of the RNP complex. A starting point is to test a range of final concentrations from 1 to 10 µM during electroporation.

- Keep the cell number constant (e.g., 8x10^5 cells per nucleofection) and vary the amount of RNP [5].

- Include a negative control (cells only) and a positive control (a well-characterized RNP) to benchmark performance and toxicity.

Optimize Post-Transfection Recovery:

- Immediately after electroporation, transfer cells into pre-warmed, antibiotic-free culture medium supplemented with small molecule inhibitors (e.g., ROCK inhibitor) to enhance cell survival.

- Allow cells to recover for at least 24-48 hours before assessing viability via trypan blue exclusion or a similar assay.

Validate Cell Health and Genotype:

- After recovery, extract genomic DNA from the cell pool.

- Use the ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) or TIDE algorithms to analyze Sanger sequencing data from PCR-amplified target sites. These tools quantitatively calculate insertion/deletion (INDEL) efficiency and are highly correlated with results from T7 endonuclease I assays and next-generation sequencing [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below lists key materials and their functions for successful RNP-based editing experiments.

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Nuclease | The core enzyme that creates double-strand breaks in DNA at the location specified by the sgRNA. Using high-fidelity variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1) can reduce off-target effects [22]. |

| Chemically Modified Synthetic sgRNA | Guides the Cas9 protein to the specific target DNA sequence. Chemical modifications at the 5' and 3' ends enhance intracellular stability and resistance to nucleases, leading to higher editing efficiency [5] [3]. |

| Electroporation System & Kits | Enables efficient physical delivery of the pre-assembled RNP complex into a wide range of cell types, including primary and stem cells [5]. |

| Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) | A peptide sequence fused to the Cas9 protein that facilitates its active transport into the nucleus, which is crucial for genome editing in mammalian cells [7]. |

| Cell Recovery Supplements | Compounds like ROCK inhibitors that improve cell viability and cloning efficiency after the stress of transfection [5]. |

| Genotyping & Analysis Tools | Kits for genomic DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and analysis software (e.g., ICE, TIDE) to accurately quantify editing efficiency and characterize mutation profiles [5]. |

Within the broader scope of thesis research aimed at optimizing sgRNA expression levels for higher mutation rates, the selection of the expression system is a critical determinant of success. This technical support resource details two advanced strategies: the use of inducible Cas9 systems for controlled nuclease expression and the application of chemical modifications to enhance sgRNA stability. These approaches directly address common experimental hurdles such as cell toxicity, variable editing efficiency, and low mutation rates, providing scientists with validated methods to improve the robustness and reproducibility of their CRISPR-Cas9 experiments.

FAQs: System Selection and Optimization

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using an inducible Cas9 system over a constitutive one?

An inducible Cas9 system, such as a doxycycline (Dox)-inducible spCas9, allows for temporal control over the nuclease's expression. This tunability is a key optimization parameter that helps mitigate the cytotoxicity often associated with constant Cas9 activity, thereby improving cell viability post-transfection. Furthermore, by enabling brief and controlled expression pulses, these systems have been demonstrated to achieve significantly higher INDEL (Insertions and Deletions) efficiencies, consistently reaching over 80% in single-gene knockouts in human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) [5] [23].

Q2: How do chemical modifications improve sgRNA performance, and what are the recommended modifications?

Chemically modified sgRNAs are engineered to resist degradation by cellular nucleases, thereby enhancing their stability and half-life inside the cell. This directly contributes to higher on-target editing efficiency. A specific and effective modification involves incorporating 2’-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate at both the 5’ and 3’ ends of the sgRNA molecule. Research has shown that this chemical synthesis enhances sgRNA stability within cells, leading to more reliable cleavage activity [5].

Q3: What is the impact of the "cell-to-sgRNA ratio" on editing efficiency?

Systematic optimization of the cell-to-sgRNA ratio is a critical factor for maximizing editing efficiency. Studies have shown that increasing the amount of sgRNA delivered to a higher number of cells can generate cell pools with progressively increasing INDEL levels [5]. This parameter must be optimized for specific cell types and delivery methods to ensure sufficient sgRNA is available for the Cas9 nuclease in each target cell.

Q4: Why might an sgRNA show high INDELs but fail to knockout the target protein (ineffective sgRNA), and how can this be detected?

An sgRNA can induce high INDEL rates at the DNA level but still be "ineffective" if the resulting frame shifts do not disrupt the protein's reading frame. This can occur if the indels are multiples of three base pairs, which may lead to in-frame deletions or mutations that do not abolish protein function. To rapidly identify such ineffective sgRNAs, it is recommended to integrate Western blot analysis with genotyping. In one documented case, an sgRNA targeting exon 2 of ACE2 showed 80% INDELs but the edited cell pool retained ACE2 protein expression, highlighting the necessity of protein-level validation [5] [23].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low editing efficiency | Poor sgRNA design/activity; Inefficient delivery; Low Cas9/sgRNA expression | Use algorithm (e.g., Benchling) for sgRNA design; Optimize nucleofection method & cell-to-sgRNA ratio [5]; Use chemically modified sgRNAs [5] |

| High cell toxicity | Constitutive Cas9 expression; High concentration of editing components | Switch to inducible Cas9 system (e.g., Dox-inducible); Titrate sgRNA and Cas9 concentrations to find balance [5] [7] |

| Ineffective knockout (high INDEL, protein present) | In-frame mutations not disrupting protein function | Design multiple sgRNAs targeting essential exons; Confirm knockout with Western blot, not just genotyping [5] |

| Variable efficiency across replicates | Inconsistent sgRNA stability; Transfection inefficiency | Use chemically synthesized, modified sgRNAs for uniform stability; Standardize nucleofection protocol and cell health [5] [7] |

| Off-target effects | sgRNA sequence homology with non-target genomic sites | Design sgRNAs with high specificity using prediction tools; Consider using high-fidelity Cas9 variants [7] |

Quantitative Data from Optimization Studies

Table 1: Optimized INDEL Efficiencies Achieved in hPSCs with an Inducible Cas9 System This table summarizes the high-efficiency outcomes from a systematically optimized protocol using a doxycycline-inducible spCas9 hPSC line [5].

| Editing Type | Target | Optimized INDEL Efficiency | Key Optimized Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Gene Knockout | Various Genes | 82% - 93% | Cell-to-sgRNA ratio, Nucleofection frequency |

| Double-Gene Knockout | Two Genes | > 80% | Co-delivery of two sgRNAs |

| Large Fragment Deletion | Two target sites on same gene | Up to 37.5% (homozygous) | Use of two sgRNAs flanking the fragment |

Table 2: Impact of sgRNA Modifications and Promoters on Editing Efficiency Data derived from studies in Chinese kale protoplasts and hPSCs demonstrate how vector design and sgRNA engineering influence outcomes [5] [24].

| Factor | Experimental Context | Result / Efficiency | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemically Modified sgRNA | hPSCs-iCas9 nucleofection | Enhanced stability and activity [5] | Critical for reproducible, high-efficiency editing |

| Promoter (35S vs. YAO) | Chinese kale protoplasts | 35S: 92.59%; YAO: 70.97% [24] | Promoter choice must be optimized for explant type |

| Single vs. Double sgRNAs | Chinese kale protoplasts (BoaZDS) | Single: 90%; Double: 100% [24] | Multiple sgRNAs can ensure complete gene disruption |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing a Doxycycline-Inducible Cas9 Cell Line

This protocol is adapted from the generation of a doxycycline-inducible spCas9-expressing hPSC (hPSCs-iCas9) line [5].

- Vector Design: Clone the spCas9 gene, along with a puromycin resistance marker, under the control of a tetracycline-responsive (Tet-On) promoter into a donor vector.

- Targeted Integration: Co-electroporate the donor vector and a second plasmid expressing Cas9 and an sgRNA targeting the AAVS1 (PPP1R12C) "safe harbor" locus into your target cells at a 1:1 weight ratio using a program like CA137 on a 4D-Nucleofector.

- Selection and Cloning: Forty-eight hours post-nucleofection, begin selection with 0.5 μg/ml puromycin for approximately one week. Subclone the surviving resistant cells.

- Validation: Genotype the resulting clonal lines using junction PCR to confirm correct integration at the AAVS1 locus. Validate Cas9 protein expression via Western blot upon the addition of doxycycline, and confirm that pluripotency is maintained.

Protocol 2: Nucleofection with Chemically Modified sgRNAs

This protocol outlines the optimized delivery of chemically synthesized sgRNAs into the established hPSCs-iCas9 line [5].

- Cell Preparation: Culture the hPSCs-iCas9 line and dissociate into single cells using a reagent like EDTA. Pellet the cells by centrifugation at 250 g for 5 minutes.

- Sample Preparation: Resuspend the cell pellet in the appropriate nucleofection buffer (e.g., P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector X Kit). Combine the buffer with 5 μg of chemically modified sgRNA (with 2’-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications). For multiple gene knockouts, mix two or three sgRNAs at the same weight ratio to a total of 5 μg.

- Nucleofection: Electroporate the cell-RNA mixture using the optimized nucleofector program (e.g., CA137).

- Induction and Recovery: After nucleofection, immediately add doxycycline to the culture medium to induce Cas9 expression. Allow the cells to recover.

- Re-nucleofection (Optional): To further boost editing efficiency, a second nucleofection with the same sgRNA can be performed three days after the first.

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Optimization Workflow for High-Efficiency Gene Knockout

Mechanism of Chemically Modified sgRNA Stability

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Optimized CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments

| Item | Function / Application in Optimization | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Doxycycline (Dox) | Small-molecule inducer for Tet-On Cas9 systems. | Used to precisely control the timing and duration of Cas9 nuclease expression [5]. |

| Chemically Modified sgRNA | Custom synthetic sgRNA with nuclease-resistant modifications. | 2’-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications at both ends enhance stability and editing efficacy [5]. |

| Nucleofection System | Device for high-efficiency delivery of CRISPR components into hard-to-transfect cells. | The 4D-Nucleofector system with cell-type specific programs (e.g., CA137 for hPSCs) is widely used [5]. |

| AAVS1 Targeting Vector | Donor plasmid for safe harbor integration of the inducible Cas9 cassette. | The AAVS1 locus (PPP1R12C) is a genomically safe location for stable transgene expression [5]. |

| ICE Analysis Tool | Web tool (Inference of CRISPR Edits) for quantifying INDEL efficiency from Sanger sequencing data. | Used for rapid and accurate assessment of editing outcomes from mixed cell pools [5]. |

| Benchling Platform | Bioinformatics platform for in silico sgRNA design and efficiency scoring. | Identified as providing the most accurate predictions for sgRNA cleavage activity among common algorithms [5]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Nucleofection Parameters

Q1: What is the optimal cell-to-sgRNA ratio for achieving high knockout efficiency in primary T cells and stem cells?

Achieving high knockout efficiency is highly dependent on using an optimal molar ratio of guide RNA (gRNA) to Cas9 protein during ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex formation. Studies across different sensitive cell types have consistently shown that a 3:1 molar ratio of gRNA to Cas9 is critical for maximizing efficiency.

- Primary Mouse and Human T Cells: Research demonstrates that transfecting with a 3:1 ratio (gRNA:Cas9) dramatically increases knockout efficiency compared to a 1:1 ratio, routinely resulting in >90% loss of target protein expression at the population level [25]. The total amount of Cas9 protein was kept constant at 5 µg (30 pmol) for these experiments [25].

- Human Pluripotent Stem Cells (hPSCs): Systematic optimization in an inducible-Cas9 hPSC system highlighted that the total amount of sgRNA and the number of cells transfected are both critical. Using 5 µg of sgRNA for 8×10⁵ cells was a key parameter that contributed to achieving stable INDEL (insertions and deletions) efficiencies of 82–93% for single-gene knockouts [5].

Q2: How does transfection frequency impact editing outcomes, and when should repeated nucleofection be considered?

A single nucleofection event can yield very high knockout efficiency. However, repeated nucleofection can be a strategic tool to further increase the proportion of edited cells, particularly for challenging applications like large-fragment deletions.

- Protocol for Double Nucleofection: In hPSCs, performing a second nucleofection 3 days after the first round, following the same procedure, has been shown to enhance editing efficiency [5].

- Application for Large Deletions: This double-nucleofection strategy was instrumental in achieving up to 37.5% homozygous knockout efficiency for large DNA fragment deletions [5]. For standard single-gene knockouts where the first transfection already achieves >80% efficiency, a second transfection may offer diminishing returns.

Q3: What are the primary causes of low editing efficiency after nucleofection, and how can they be troubleshooted?

Low editing efficiency can stem from several factors related to cell health, reagent quality, and nucleofection parameters. The table below outlines common issues and their solutions.

Table: Troubleshooting Guide for Low CRISPR Editing Efficiency in Nucleofection

| Potential Cause | Symptoms | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal RNP Complex Formation | Low INDEL rates despite high cell viability | Increase the molar ratio of gRNA to Cas9 protein to 3:1 during RNP complex assembly [25]. |

| Poor Cell Health Pre-Transfection | Low baseline viability, slow growth post-transfection | Use healthy, actively dividing cells. Avoid using over-confluent or stressed cultures [26]. |

| Ineffective sgRNA | High INDELs detected by sequencing, but target protein is still expressed | Use chemically modified, synthetic sgRNAs for enhanced stability. Validate sgRNA efficacy using algorithms like Benchling and confirm protein knockout with Western blotting [5]. |

| Incorrect Cell Density | Variable efficiency between experiments | For hPSCs, use a high cell density of 8×10⁵ cells per nucleofection with 5 µg sgRNA [5]. Optimize confluency for your specific cell type. |

| High Toxicity | Significant cell death within 12-24 hours | Reduce the amount of RNP complex or total nucleic acid delivered. Ensure the nucleofection buffer and program are optimized for the specific cell type [26]. |

Q4: Beyond ratio and frequency, what other strategic factors can enhance sgRNA expression and editing efficiency?

- sgRNA Modifications: Using chemically synthesized sgRNAs (CSM-sgRNA) with 2’-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications at both the 5’ and 3’ ends can significantly enhance sgRNA stability within cells, protecting them from degradation and leading to higher editing efficiency [5].

- Multiplexing sgRNAs: Expressing multiple sgRNAs simultaneously can have a synergistic effect on mutagenesis. This is particularly effective for targeting multiple genes or for ensuring complete knockout of a single gene by targeting several exons [27] [28]. In poplar, using a construct with triple sgRNA copies enhanced editing outcomes for allelic and homologous genes [28].

- sgRNA Length: While the standard is 20 nucleotides, systematic testing of sgRNA length can yield optimizations. One study in plants found that a 20-nucleotide (nt) sgRNA demonstrated the highest editing efficiency compared to lengths of 18-22 nt [28].

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimized RNP Nucleofection for Primary T Cells

This protocol is adapted from Seki and Rutz (2018) and is designed for high-efficiency knockout without requiring T cell receptor stimulation [25].

RNP Complex Formation:

- Resuspend a 3:1 molar ratio of chemically modified crRNA (target-specific) to fluorescently labeled tracrRNA in nuclease-free buffer.

- Heat the mixture at 95°C for 5 minutes and allow it to cool to room temperature to form the guide RNA (gRNA) duplex.

- Complex the gRNA duplex with recombinant Cas9 protein (e.g., 5 µg or 30 pmol per reaction) by incubating at room temperature for 10-20 minutes to form the RNP complex.

Cell Preparation:

- Isolate primary mouse or human T cells. No pre-stimulation is required.

- Count the cells and centrifuge the required amount (e.g., 2 million cells per condition).

- Aspirate the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet in the appropriate nucleofection buffer (e.g., Lonza P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector X Kit).

Nucleofection:

- Mix the cell suspension with the pre-formed RNP complex.

- Transfer the mixture to a nucleofection cuvette.

- Electroporate using the recommended program (e.g., for primary T cells, the Lonza 4D system with pulse DN-100 is cited [25]).

- Immediately after pulsing, add pre-warmed culture medium to the cuvette and transfer the cells to a culture plate.

Post-Transfection Analysis:

- Monitor transfection efficiency after 4-6 hours using the fluorescence from the labeled tracrRNA.

- Assess knockout efficiency by flow cytometry (for surface proteins) or functional assays 3 days post-transfection.

Protocol 2: Double Nucleofection in Inducible Cas9 hPSC Lines

This protocol is adapted from the work in Nature (2025) for achieving high-efficiency single and multiple gene knockouts in stem cells [5].

Cell Line and Culture:

- Use a doxycycline (Dox)-inducible spCas9-expressing hPSC line (hPSCs-iCas9) cultured in defined conditions.

First Nucleofection:

- Treat hPSCs-iCas9 with Dox to induce Cas9 expression.

- Dissociate cells with EDTA and pellet by centrifugation.

- For a high-efficiency condition, use 8×10⁵ cells and 5 µg of chemically modified sgRNA.

- Combine the cell pellet with the sgRNA resuspended in nucleofection buffer.

- Electroporate using an optimized program (e.g., CA137 on a Lonza 4D-Nucleofector [5]).

- Recover the cells in fresh medium.

Second Nucleofection:

- 3 days after the first nucleofection, repeat the exact same procedure: dissociate, pellet, and electroporate the cells again with the same sgRNA [5].

- This double-nucleofection strategy is particularly recommended for challenging edits like large fragment deletions.

Analysis:

- Harvest cells 3-5 days after the final nucleofection for genomic DNA extraction.

- Analyze INDEL efficiency using T7EI assay, Sanger sequencing with ICE analysis, or next-generation sequencing. Confirm protein loss via Western blot.

Optimization Workflow and Efficiency Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the strategic decision-making process for optimizing nucleofection parameters, from initial setup to analysis, based on the cited research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for Optimizing Nucleofection and sgRNA Expression

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Chemically Modified sgRNA | Enhances stability and reduces degradation within cells, leading to higher editing efficiency and more consistent results [5]. | Synthetic sgRNA with 2’-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications at 5' and 3' ends [5]. |

| Recombinant Cas9 Protein | Essential component for RNP-based transfection. Allows for precise control over concentration and rapid activity with minimal off-target effects compared to plasmid delivery [25]. | High-purity, endotoxin-free spCas9. |

| Cell-Type Specific Nucleofection Kits | Pre-optimized buffers and electroporation parameters that maximize cell viability and delivery efficiency for specific cell types (e.g., primary T cells, stem cells) [5] [25]. | e.g., Lonza P3 Primary Cell 4D-Nucleofector X Kit for T cells [25]; specific programs like CA137 for hPSCs [5]. |

| Inducible Cas9 Cell Line | Enables temporal control of Cas9 expression, minimizing toxicity and allowing for the study of essential genes. Tunable expression can be optimized for different applications [5]. | e.g., hPSCs with a Dox-inducible spCas9 stably integrated into a safe-harbor locus (e.g., AAVS1) [5]. |

| Multiplexed sgRNA Expression System | Allows simultaneous expression of multiple gRNAs from a single transcript, increasing mutation frequencies and enabling coordinated targeting of multiple genomic loci [27]. | Systems utilizing the bacterial endonuclease Csy4 for processing a single transcript into multiple functional gRNAs [27]. |

Leveraging Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) for Efficient In Vivo sgRNA Delivery

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using LNPs for sgRNA delivery compared to viral vectors? LNPs offer several key advantages for sgRNA delivery, including reduced immunogenicity, avoidance of viral genome integration risks, and a shorter intracellular half-life that minimizes off-target DNA damage [29]. Their composition is highly customizable, allowing researchers to tune lipid ratios and surface properties for specific tissue targeting [30]. Furthermore, LNP manufacturing is scalable and has a proven track record of clinical use [29].

Q2: Why is my LNP formulation inefficient for in vivo delivery to non-liver tissues like the lungs? Liver tropism is a common characteristic of many first-generation LNPs. Achieving efficient editing in non-liver tissues like the lungs requires tissue-selective LNP formulations [29]. This can involve optimizing the ionizable lipid component or incorporating targeting ligands (e.g., peptides, antibodies) onto the LNP surface to direct it to specific cells or organs [30]. The use of stable ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, rather than mRNA, can also enhance editing in hard-to-transfect tissues [29].

Q3: How can I improve the stability and genome-editing efficiency of the CRISPR machinery encapsulated in LNPs? A highly effective strategy is to encapsulate thermostable Cas9 RNP complexes instead of Cas9 mRNA and sgRNA separately. Research shows that engineered, thermostable Cas9 variants (e.g., iGeoCas9) maintain activity under LNP formulation conditions and can achieve high editing efficiency (e.g., 19% in lung tissue) [29]. Optimizing the mRNA sequence through nucleoside modification and UTR/poly(A) tail engineering also enhances stability and translation efficiency [30].

Q4: What are the critical safety concerns associated with in vivo CRISPR-LNP delivery, and how can I assess them? Beyond off-target mutations, a significant concern is the generation of large, on-target structural variations (SVs), including kilobase- to megabase-scale deletions and chromosomal translocations [31]. These risks can be exacerbated by strategies that inhibit the NHEJ DNA repair pathway to enhance HDR. For a comprehensive safety assessment, employ specialized genomic methods like CAST-Seq or LAM-HTGTS that can detect these large SVs, as they are often missed by standard short-read amplicon sequencing [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Mutation Rates Despite Successful Cellular Delivery

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Unstable sgRNA or RNP Complex. The sgRNA may degrade before reaching the target cell, or the RNP may disassemble.

- Solution: Encapsulate pre-assembled, thermostable Cas9 RNP complexes. Using an evolved, thermostable Cas9 (iGeoCas9) demonstrated over 100-fold higher genome editing in cells and animals compared to its wild-type version [29].

Solution: Optimize LNP composition with ionizable lipids that facilitate endosomal escape. The protonation state of ionizable lipids is critical for this process and can be modeled computationally for better design [32].

Cause: Inefficient DNA Repair Pathway Engagement. The desired mutation may rely on a specific DNA repair pathway (e.g., HDR) that is less active in your target tissue.

- Solution: Avoid the use of DNA-PKcs inhibitors (e.g., AZD7648) to promote HDR, as they have been shown to drastically increase the frequency of large, undesirable genomic deletions and chromosomal translocations [31].

- Solution: For knock-outs, rely on the more active NHEJ pathway. Ensure your experimental design accounts for the inherent indels this pathway produces.

Experimental Protocol: Assessing On-Target Editing and Genomic Integrity This protocol is adapted from studies highlighting the importance of detecting structural variations [31].

- Isolate Genomic DNA: Extract gDNA from treated cells or tissues 48-72 hours post-delivery.

- Amplify Target Locus: Perform long-range PCR (amplicon size >5 kb) spanning the CRISPR target site. Using multiple, widely spaced primers helps detect large deletions.

- Sequence: Subject amplicons to long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio) or specialized short-read sequencing that can detect structural variations (e.g., CAST-Seq, LAM-HTGTS).

- Analyze Data:

- Quantify the overall editing efficiency (indel %).

- Specifically screen for large deletions (>1 kb) and genomic rearrangements at the on-target site.

- Compare the results to those from standard short-read amplicon sequencing to check for overestimation of HDR due to undetected deletions.

Issue 2: High Cytotoxicity or Immune Response

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Immune Activation by Nucleic Acid Cargo.

- Solution: Use purified RNP complexes instead of mRNA. RNPs elicit lower levels of Toll-like receptor (TLR) activation compared to in vitro transcribed mRNA [29].

Solution: Incorporate nucleoside modifications (e.g., pseudouridine) in the sgRNA or mRNA coding for Cas9 to reduce innate immune recognition [30].

Cause: Toxicity from LNP Components.

- Solution: Utilize biodegradable ionizable lipids. Studies have shown that LNPs with biodegradable lipids can efficiently edit liver (37%) and lung (16%) tissue in mice with good tolerability [29].

- Solution: Explore alternatives to PEG-lipids, such as more biocompatible polymers (pSar, POx), to mitigate potential immune reactions against PEG [30].

Issue 3: Off-Target Editing in Non-Target Tissues

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Lack of Tissue Specificity in LNP Formulation.

- Solution: Employ organ-selective LNP formulations by adjusting the lipid composition and ratios. For example, specific formulations have been developed to target the lungs or liver selectively [29].

Solution: Functionalize the LNP surface with targeting ligands (small molecules, peptides, or antibodies) that bind to receptors highly expressed on your target cell type [30].

Cause: Inherent Off-Target Activity of the CRISPR System.

- Solution: Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., HiFi Cas9) to reduce off-target cleavage [31].

- Solution: Perform careful gRNA design using validated software to minimize sequence similarity to off-target sites in the genome.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key LNP Components and Their Functional Roles

| Component Class | Example Molecules | Primary Function | Optimization Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipid | DLin-MC3-DMA, ALC-0315 | Encapsulation, endosomal escape via protonation | pKa should be ~6.5 for optimal endosomal escape; biodegradable backbones improve safety [29] [32]. |

| Helper Lipid | Cholesterol, DSPC | Stabilizes LNP structure and membrane integrity | Modulates membrane fluidity and stability [32]. |

| PEG-lipid | DMG-PEG, ALC-0159 | Shields LNP surface, controls size, prevents aggregation | Higher molecular weight PEG reduces opsonization; consider alternatives (pSar) to anti-PEG immunity [30]. |

| Targeting Ligand | Peptides, Antibodies, Sugars | Directs LNP to specific cell types or organs | Conjugation to PEG-lipid anchor; balance between specificity and immune recognition [30]. |

Table 2: Optimization Parameters for Enhanced In Vivo sgRNA Delivery

| Parameter | Challenge | Optimization Strategy | Experimental Readout |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cargo Type | mRNA instability, TLR activation | Use of pre-assembled, thermostable RNP complexes (e.g., iGeoCas9) [29]. | Editing efficiency (% indels), cytokine levels. |

| LNP pKa | Inefficient endosomal escape | Design ionizable lipids with pKa ~6.5 using constant pH molecular dynamics (CpHMD) models [32]. | In vitro potency assay; in vivo editing levels. |

| PEG-lipid % | Rapid clearance, immune response | Systematic adjustment (0.5-3 mol%) to balance stability and pharmacokinetics [30]. | LNP size (DLS), plasma half-life, editing in target tissue. |

| Organ Targeting | Accumulation in liver/lungs | SPOT strategy, surface functionalization with targeting ligands [30]. | Biodistribution study (e.g., in live mice). |

Experimental Workflows and Pathways

Diagram: LNP Formulation and In Vivo Delivery Workflow

LNP Formulation and In Vivo Delivery Workflow

Diagram: sgRNA Optimization for Enhanced Mutation Rates

sgRNA Optimization for Enhanced Mutation Rates

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for LNP-mediated sgRNA Delivery

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example / Note |