Optimizing Sensor Placement for Maximum Crop Coverage: Advanced Methods and Future Directions for Agricultural Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies for optimizing sensor placement in agricultural monitoring systems.

Optimizing Sensor Placement for Maximum Crop Coverage: Advanced Methods and Future Directions for Agricultural Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies for optimizing sensor placement in agricultural monitoring systems. It explores the foundational principles of precision agriculture, details advanced computational methodologies like the Multi-Strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm (MSPOA) and genetic programming, and addresses practical challenges such as sensor failure and environmental constraints. By comparing the performance of various optimization techniques and validating their real-world applications in settings from greenhouses to open fields, this review serves as a critical resource for researchers and professionals aiming to design cost-effective, efficient, and robust sensor networks for enhanced crop management and yield optimization.

The Fundamentals of Agricultural Sensor Networks and Coverage Goals

Precision farming with IoT (Internet of Things) integrates smart devices, sensors, and cloud-based platforms to collect, monitor, and analyze real-time data about crops, soil, and weather [1]. The goal is to maximize yields, minimize waste, and promote sustainable agricultural practices by making every farming action measurable and optimizable [1]. For researchers, this represents a shift from traditional methods to a data-driven paradigm where sensor placement and data integrity are foundational to experimental success.

Core IoT Technologies in Agricultural Research

The following table summarizes the key IoT innovations that enable data collection in modern agricultural research.

Table 1: Key IoT Technologies in Precision Agriculture

| Technology | Brief Description | Key Research Application | Estimated Impact on Yield | Estimated Reduction in Waste |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart Field Sensors [1] | Real-time measurement of soil, weather, and crop health variables. | Continuous, multi-variable data acquisition for field experiments. | +20% | -25% |

| AI-Powered Drones [1] | Aerial mapping and crop scanning with multispectral/thermal sensors. | High-frequency, high-coverage scouting and spatial data analysis. | +15% | -30% |

| Automated Irrigation Management [1] | Smart, adaptive water management using real-time soil moisture data. | Optimizing water use efficiency and studying plant hydration stress. | +18% | -50% |

| Precision Farming Robots [1] | Autonomous tasks (weeding, harvesting) guided by sensor data and AI. | Automating repetitive experimental procedures and input application. | +22% | -40% |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

A. Troubleshooting Common Sensor and Connectivity Issues

The diagram below outlines a systematic workflow for diagnosing and resolving common IoT sensor issues in an agricultural research setting.

FAQ: Addressing Specific Research Challenges

Q1: My sensor node is powered but not sending data to the research database. What should I check?

- A: Follow the diagnostic workflow above. First, use your network provider's tools (e.g., Network Logs) to verify the device has attached to a cellular network [2]. If it is attached but no data connection is established, check if the device's data limit has been reached or if the Access Point Name (APN) is configured correctly [2]. For non-cellular setups, inspect gateways and routers.

Q2: The data from my soil moisture sensors seems inaccurate or drifts over time. How can I verify its integrity?

- A: This is likely a calibration issue. Sensor calibration is critical for research-grade data [3]. To troubleshoot:

- Perform a two-point calibration: Immerse the sensor probe in a known reference, such as ice water (0°C) and boiling water (100°C) for temperature, and compare readings [4].

- Check for environmental factors: Humidity buildup or physical debris on the probe can cause drift. Clean the sensor with isopropyl alcohol and ensure proper housing [4].

- Establish a calibration schedule: Implement a routine calibration protocol based on sensor usage and environmental harshness, documenting every step for traceability [5] [3].

Q3: My wireless sensor network (WSN) has inconsistent coverage, leaving blind spots in my experimental field. How can this be optimized?

- A: Optimizing sensor coverage is a primary challenge in Agricultural Wireless Sensor Networks (AWSNs) [6].

- Algorithmic Optimization: Deploy advanced optimization algorithms like the Multi-Strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm (MSPOA) to compute optimal node placement. MSPOA has been shown to improve network coverage by over 20% compared to traditional methods like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [6].

- Physical Audit: Conduct a physical site survey to identify obstacles (e.g., terrain, foliage) that cause signal attenuation and adjust node placement accordingly.

Q4: I am concerned about the security and integrity of my collected sensor data. What are the risks?

- A: IoT devices can be vulnerable, making data integrity a key concern [7]. Key risks include:

- Insecure Design: Devices with default passwords or unencrypted data can be compromised [7].

- Data Quality: Poor data quality from faulty sensors leads to flawed research conclusions [8].

- Mitigation Strategies: Implement network segmentation, use devices with verifiable secure boot and over-the-air update capabilities, and employ data validation tools to ensure data trustworthiness [7] [8].

B. Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Sensor Placement for Maximum Crop Coverage

This protocol provides a methodology for deploying a wireless sensor network (WSN) to achieve optimal coverage in an agricultural research plot, a common focus in thesis research.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for AWSN Deployment

| Essential Material / Solution | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Wireless Sensor Nodes [6] | Low-power, ruggedized devices equipped with sensing, communication, and computation capabilities for data collection. |

| Multi-Strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm (MSPOA) [6] | An advanced algorithm to calculate the optimal coordinates for sensor deployment to maximize coverage and minimize blind spots. |

| NIST-Traceable Reference Standards [5] | Calibration equipment with a known, verifiable accuracy to ensure the validity of all sensor measurements. |

| Spectrum Analyzer [4] | A tool to identify electromagnetic interference (EMI) patterns in the field that could disrupt wireless communication between nodes. |

| Network Logging & Traffic Monitor Software [2] | Software tools to monitor network attachment, data connections, and packet traffic for diagnosing connectivity issues. |

Methodology:

Pre-Deployment Sensor Calibration:

Define the Target Area and Parameters:

- Clearly demarcate the agricultural field for monitoring.

- Define the sensing radius and communication range of your sensor nodes based on manufacturer specifications and preliminary field tests.

Run the Coverage Optimization Algorithm:

- Input the field parameters and sensor specifications into the MSPOA or a similar advanced optimization algorithm [6].

- The algorithm will output a set of proposed coordinates that maximize coverage area, typically aiming to cover the area of interest while minimizing the number of deployed sensors [6].

Deploy Sensors and Validate Coverage:

- Physically deploy the sensor nodes at the coordinates determined by the algorithm.

- Validate the network coverage by checking the status of each node and ensuring data is being reported from the entire target area. Use network logging tools to confirm stable connections [2].

Monitor and Iterate:

- Continuously monitor network performance and data quality. The MSPOA demonstrates strong adaptability and can be re-run to account for dynamic changes in the environment or network topology [6].

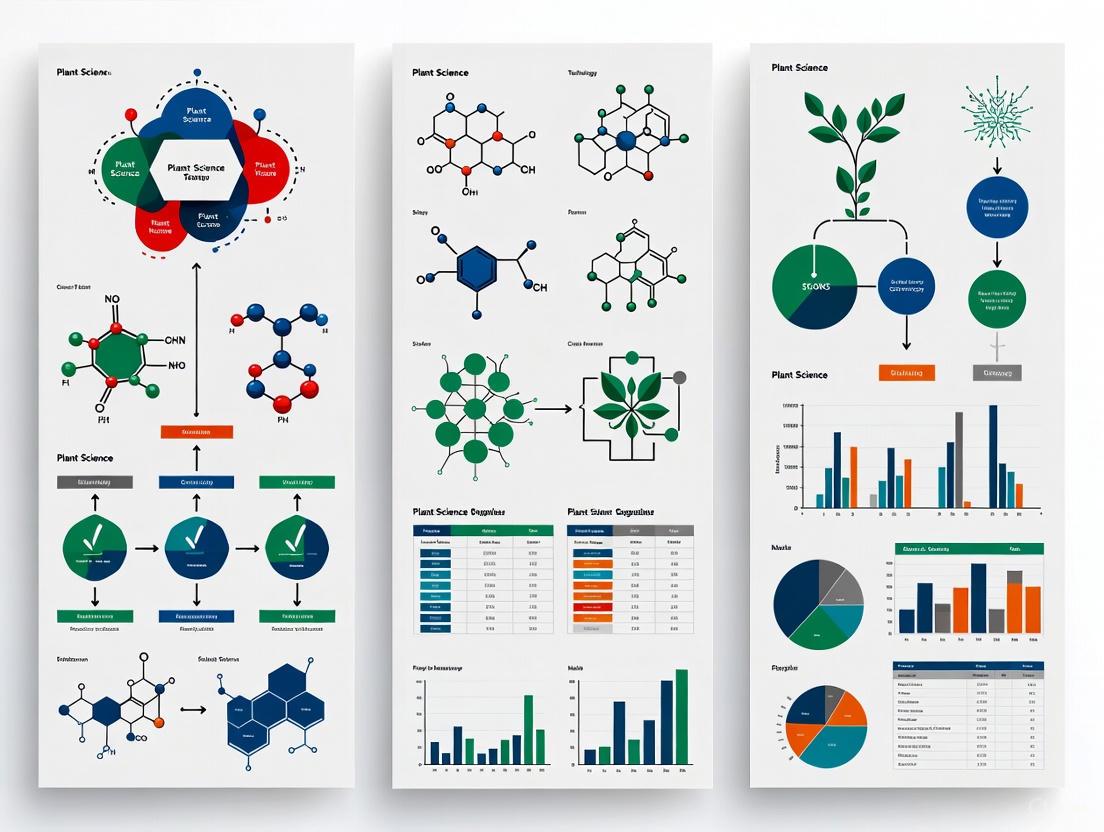

The following diagram visualizes the iterative workflow of this experimental protocol.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What does "network coverage" mean in the context of agricultural wireless sensor networks (AWSN)? In AWSNs, coverage refers to the strategic arrangement of sensor nodes to ensure complete or partial monitoring of a target agricultural field. The goal is to maximize the area of interest being effectively covered, which directly impacts the quality of data collected on parameters like temperature, humidity, and soil moisture [6].

2. Why is sensor coverage optimization considered a challenging problem? Sensor coverage optimization is an NP-hard problem. This means that as the size of the network and the area increases, the complexity of finding the optimal sensor placement grows exponentially. Traditional optimization algorithms often struggle with premature convergence to local optimal solutions and slow convergence speeds, especially in large-scale deployments [6].

3. What are the primary strategies for minimizing costs in a sensor network deployment? The key strategies focus on minimizing the number of deployed sensors while maximizing coverage, which directly reduces hardware costs. Furthermore, optimizing sensor placement leads to reduced energy consumption for communication and data transmission, thereby extending the network's operational lifetime and reducing long-term maintenance and resource costs [6].

4. How does the Multi-Strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm (MSPOA) improve upon traditional methods? MSPOA integrates several advanced strategies to overcome the limitations of traditional algorithms [6]:

- It uses a good point set strategy for population initialization to enhance the search range and prevent early convergence to local optima.

- A 3D spiral Lévy flight strategy helps the algorithm explore a broader search space, escape local optima, and improve global search accuracy and convergence speed.

- An adaptive T-distribution variation strategy further boosts the global search ability and helps balance local and global optimization.

5. My algorithm is converging prematurely. What could be the cause? Premature convergence is often caused by a lack of population diversity or insufficient global exploration capabilities in the algorithm. This can be mitigated by incorporating strategies that introduce controlled perturbations or randomness, such as the good point set strategy for initialization or the Lévy flight strategy used in MSPOA to help the algorithm jump out of local optima [6].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

The following table summarizes a key experiment comparing the performance of the Multi-Strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm (MSPOA) against other contemporary algorithms for WSN coverage optimization [6].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Coverage Optimization Algorithms

| Algorithm Name | Full Name | Key Mechanism | Reported Coverage Improvement vs. MSPOA |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSPOA | Multi-Strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm | Good point set, 3D spiral Lévy flight, adaptive T-distribution | Baseline (Superior Performance) |

| IABC | Improved Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm | Inspired by bee foraging behavior | 5.85% lower |

| CAFA | Chaotic Adaptive Firefly Optimization Algorithm | Based on firefly flashing patterns and attractiveness | 11.33% lower |

| APSO | Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization | Simulates social behavior of bird flocking | 21.05% lower |

| LCSO | Lévy Flight Strategy Chaotic Snake Optimization | Models snake mating and foraging behavior | 20.66% lower |

Detailed Methodology for MSPOA-based Coverage Optimization:

This protocol outlines the steps to implement and evaluate the MSPOA for sensor deployment.

Problem Formulation:

- Objective: Maximize the effective coverage rate of the target agricultural field.

- Constraints: The number of sensors is fixed, and each sensor node has a defined sensing radius based on its hardware capabilities.

- Fitness Function: The coverage rate is calculated as the ratio of the total covered area to the total target area. The algorithm aims to find the sensor coordinates (X, Y positions) that maximize this fitness function.

Algorithm Initialization:

- Population: Generate an initial population of candidate sensor deployment solutions. The MSPOA uses a good point set strategy to ensure this initial population is diverse and uniformly distributed across the search space, which enhances stability and convergence performance [6].

Iterative Optimization Process: The algorithm iteratively improves the population of solutions through the following phases:

- Pelican Inspired Movement & Collaboration: This core phase updates the positions of the candidate solutions based on a model of pelican foraging behavior, enhancing the algorithm's adaptability and robustness in diverse agricultural scenarios [6].

- 3D Spiral Lévy Flight Strategy: To prevent stagnation in local optima, this strategy is applied. It combines the long-range exploration capabilities of Lévy flights with local spiral search patterns, allowing the algorithm to explore a broader search space and improve global search accuracy [6].

- Adaptive T-distribution Variation Strategy: In the final stage, this strategy acts as a mutation operator. The "T-distribution" parameter, which adapts with the number of iterations, helps to balance global exploration in early stages and local fine-tuning in later stages, thereby improving the overall search accuracy [6].

Termination and Evaluation:

- The algorithm terminates after a predefined number of iterations or when the solution converges.

- The best-found sensor deployment configuration is selected.

- Performance is evaluated by calculating the final coverage rate and comparing it with other algorithms, as shown in Table 1.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

The following table details key computational and hardware components essential for conducting research in AWSN coverage optimization.

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Sensor Coverage Optimization

| Item / "Reagent" | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Pelican Optimization Algorithm (POA) | The base metaheuristic algorithm that mimics the foraging behavior of pelicans to solve optimization problems. |

| Multi-Strategy Enhancement Modules | Software modules implementing the Good Point Set, 3D Spiral Lévy Flight, and Adaptive T-distribution strategies to boost POA performance [6]. |

| Agricultural WSN Simulator | A simulation platform (e.g., MATLAB, NS-3, OMNeT++) to model the agricultural environment, sensor nodes, and wireless communication without physical deployment. |

| Cropland Data Layer (CDL) / Satellite Imagery | Geo-referenced, crop-specific land cover data (e.g., from USDA NASS) used to define the target monitoring area and its characteristics for realistic simulation scenarios [9] [10]. |

| Sensor Node Hardware Specifications | Physical or simulated specifications of sensor nodes, including sensing radius, communication range, and power consumption models, which are key parameters in the coverage model [6]. |

Experimental Workflow and Algorithm Strategy Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the core workflow of the Multi-Strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm for sensor deployment.

MSPOA Sensor Deployment Workflow

The following diagram provides a conceptual view of the key strategies enhancing the base Pelican Optimization Algorithm.

Multi-Strategy Enhancement of POA

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary difference between a standard RGB camera and a hyperspectral imaging camera? While a standard RGB camera captures images in three broad bands (red, green, and blue), a hyperspectral camera captures images in hundreds of narrow, contiguous spectral bands [11]. This allows a hyperspectral camera to identify and quantify materials based on their unique spectral signatures, going beyond visual color to assess chemical and physical properties [11].

Q2: Why is sensor calibration critical in agricultural research? Sensor calibration is the process of aligning a sensor's output with a known standard to ensure accuracy and reliability [3]. It is crucial because uncalibrated sensors can produce inaccurate data, leading to flawed conclusions, improper resource application (like water and fertilizers), and compromised research outcomes [3]. For soil moisture sensors, correct calibration for the specific soil type is essential for accurate volumetric water content readings [12].

Q3: My soil moisture sensor is providing erratic or unexpected readings. What are the most common causes? Unexpected readings typically stem from one of three issues [12]:

- Poor Soil Contact: Air gaps between the sensor probe and the soil can cause readings that are too low when dry and too high when saturated [12].

- Incorrect Calibration: Using a sensor calibrated for a soil type different from your own will result in inaccurate data and misinterpreted field capacity or plant stress points [12].

- Physical Damage or Water Intrusion: Sensors can be damaged by field equipment, and their electronics can be compromised by water accumulation if not properly sealed [13].

Q4: Can I process hyperspectral data with standard image software like Photoshop? No. Software like Photoshop is designed for 3-band RGB images and cannot process the hundreds of bands in a hyperspectral data cube [11]. Specialized software like IDCubePro, ENVI, or MATLAB is required for hyperspectral data analysis [11] [14].

Q5: How can I optimize the number and placement of sensors in a large field? Optimizing sensor placement is an NP-hard problem. Advanced methods like the Multi-strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm (MSPOA) can be used to maximize coverage and data accuracy while minimizing the number of sensors [6]. A general methodology involves analyzing spatial variability, using cost-minimization algorithms, and leveraging existing data maps to guide placement for comprehensive data representation [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Soil Moisture Sensor Anomalies

Table 1: Common Soil Moisture Sensor Issues and Solutions

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Readings are persistently low when soil is dry, high when saturated | Poor contact with the soil; air gaps around the probe [12] | Reinstall the sensor. For single-depth sensors, use a rubber mallet. For multi-depth sensors, create a pilot hole and use a soil slurry to ensure contact [12]. |

| Readings do not align with known soil conditions or lab analysis | Incorrect soil type calibration [12] | Verify soil texture via sampling and lab analysis. Select the correct calibration from the sensor's library or create a custom calibration [12]. |

| Sensor fails to power on or data transmission stops | Electrical issues: poor power connection, damaged cables, or circuit damage [13] | Check all power and cable connections. Inspect wires for damage and replace if necessary [13]. |

| Data is erratic or shows "water accumulation" errors | Water has intruded into the sensor housing [13] | Check waterproof seals and connectors. The sensor may require cleaning, drying, or replacement if damaged [13]. |

Hyperspectral Imaging Data Challenges

Table 2: Common Hyperspectral Data Issues and Solutions

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Software runs slowly or freezes when loading data | File size is too large for available computational resources [14] | Use binning or cropping functions to reduce the spatial and spectral resolution of the data before processing [14]. |

| Inability to open data files | File format incompatibility [14] | Use the software's import function to convert proprietary files to a compatible format (e.g., .m or .mat) before opening [14]. |

| Poor quality spectral signatures; inability to distinguish materials | Incorrect setup; low signal-to-noise ratio [11] | Ensure proper illumination and exposure settings. Remember, hyperspectral imaging has low penetration depth and cannot "see through" most samples [11]. |

| Batch processing is not available | Software limitation | IDCube software does not support batch processing. Process files individually or in simultaneous sessions (up to 10 files) [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Placement Optimization

Protocol 1: Methodology for Optimal Spatial Sensor Placement

This protocol outlines a systematic approach for determining the number and location of sensors to maximize coverage and data accuracy in an agricultural parcel [15].

1. Define Objectives and Constraints:

- Objective: Clearly state the primary goal (e.g., monitor soil moisture variability, assess canopy health).

- Constraints: Identify limitations, including budget (number of sensors), terrain (accessibility, topography), and required data resolution.

2. Data Collection and Base Mapping:

- Gather existing spatial data for the parcel, such as soil maps, historical yield maps, or elevation models.

- If no prior maps exist, conduct a preliminary coarse-grid soil sampling or use a UAV with a hyperspectral camera to generate a baseline variability map [15].

3. Data Analysis and Weighted Subsampling:

- Analyze the spatial dataset to identify zones of high variability (e.g., areas with high statistical variance). These are critical areas for sensor placement [15].

- Apply soft clustering algorithms to group areas with similar properties.

4. Optimization Algorithm Execution:

- Employ an optimization algorithm like the Multi-strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm (MSPOA) to determine the exact sensor positions [6].

- Inputs: Variability map, number of available sensors, cost constraints.

- Output: A set of geographic coordinates representing optimal sensor locations that maximize coverage of the parcel's variability.

5. Field Deployment and Validation:

- Install sensors at the specified coordinates.

- Validate the deployment by collecting data and ensuring it captures the expected spatial variability. Use kriging or other interpolation methods to create a coverage map from the sensor data and compare it to the original base map.

Protocol 2: Troubleshooting Soil Sensor Installation and Calibration

A step-by-step guide to resolve common soil moisture sensor data quality issues [12] [3].

1. Problem Identification:

- Compare sensor data to physical soil samples or another trusted sensor.

- Check for patterns indicating poor contact (e.g., readings that are consistently off or unresponsive to irrigation/rainfall).

2. Verify Physical Installation:

- Check for Good Contact: Gently try to wiggle the sensor. It should be firmly seated in the soil with no movement.

- Re-install if Necessary: Remove the sensor. For a new installation, use a rubber mallet for single probes or a pre-drilled pilot hole with a soil slurry for multi-depth probes to eliminate air gaps [12].

3. Verify and Re-calibrate the Sensor:

- Confirm Soil Type: Collect a soil sample from the installation area for laboratory texture analysis [12].

- Select Correct Calibration: Choose the appropriate calibration curve from the manufacturer's library that matches your soil's sand, silt, and clay composition [12].

- Perform Calibration: Follow the manufacturer's protocol. This often involves a two-point (zero and span) or multi-point calibration against known standards [3].

4. Document the Process:

- Record the date of re-installation, new calibration settings, and soil lab results. This documentation is essential for data traceability and future troubleshooting [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Tools for Sensor-Based Agricultural Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Volumetric Soil Moisture Sensors | Measure the water content in soil as a percentage, providing critical data for irrigation scheduling and soil health studies [12]. |

| Hyperspectral Imaging Cameras | Capture detailed spectral signatures for identifying plant stress, nutrient deficiencies, and material composition beyond the visible spectrum [11]. |

| Calibration Reference Standards | Known physical standards (e.g., for temperature, reflectance) used to calibrate sensors, ensuring data accuracy and traceability to international systems [3]. |

| Soil Sampling Kits | Used for collecting soil cores for laboratory analysis of texture, nutrient content, and organic matter, which is vital for validating and calibrating in-situ sensors [12]. |

| Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs/Drones) | Platforms for mounting sensors (especially cameras) to collect high-resolution, geo-referenced data over large areas efficiently [16]. |

| Data Fusion & Analysis Platforms (e.g., AEther, EOSDA) | Software that integrates data from multiple sources (satellites, drones, ground sensors) to provide comprehensive analytics and insights [16] [17]. |

| Multi-Strategy Optimization Algorithms (e.g., MSPOA) | Advanced computational methods used to solve complex sensor placement problems, maximizing coverage and efficiency while minimizing costs [6]. |

Integrated Data Framework for Crop Coverage Research

Understanding the Agricultural Wireless Sensor Network (AWSN) Environment

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: What are the most common causes of incomplete coverage in a large-scale AWSN deployment?

Incomplete coverage is frequently not a hardware failure but an optimization problem. In large fields, traditional deployment methods often lead to coverage blind spots or sensor redundancy, which wastes energy and cost. Optimizing the placement of a limited number of sensors to achieve maximum coverage is an NP-hard problem, meaning it is computationally complex. Advanced bio-inspired algorithms, like the Multi-Strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm (MSPOA), have been developed specifically to address this by enhancing global search capabilities and preventing convergence on sub-optimal sensor layouts, thereby significantly improving coverage rates [6].

Q2: Our sensor data is inconsistent across the field. How can we ensure it is representative of the entire microclimate?

Data inconsistency often stems from non-optimal sensor placement that fails to capture the spatial variability of microclimatic conditions. A proven methodology involves:

- Initial Dense Sampling: Temporarily deploying a large number of sensors across the area [18].

- Data Aggregation: Creating a high-quality reference data set by aggregating (e.g., averaging) measurements from all these sensors [18].

- Optimal Location Identification: Using computational methods to find the minimal number of sensor locations whose data can best predict the full aggregated reference data. Techniques like Genetic Programming (GP) [18] or machine learning clustering [19] can identify these key positions, ensuring the final, smaller sensor network still provides data representative of the entire environment.

Q3: How can we reduce the cost and energy consumption of our AWSN without compromising data quality?

The key is to deploy fewer sensors strategically. Research demonstrates that optimal placement can reduce the number of sensors needed by over 90% while maintaining monitoring efficacy [18]. This directly reduces procurement and energy costs. Furthermore, coverage optimization algorithms are designed to minimize sensor redundancy, which extends the network's operational lifespan by reducing the energy required for data transmission and processing [6].

Performance Data of Sensor Placement Optimization Algorithms

The following table summarizes the performance of various optimization algorithms in improving Wireless Sensor Network (WSN) coverage, a core metric for effective monitoring. The Multi-Strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm (MSPOA) shows significant improvements over other common algorithms [6].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of WSN Coverage Optimization Algorithms

| Algorithm Name | Full Algorithm Name | Reported Coverage Improvement over Baseline | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSPOA | Multi-Strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm | 5.85% - 21.05% higher than benchmarks | Balances global search and convergence speed [6]. |

| IABC | Improved Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm | Benchmark for MSPOA | A standard benchmark algorithm [6]. |

| CAFA | Chaotic Adaptive Firefly Optimization Algorithm | Benchmark for MSPOA | A standard benchmark algorithm [6]. |

| APSO | Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization | Benchmark for MSPOA | A standard benchmark algorithm [6]. |

| LCSO | Lévy Flight Strategy Chaotic Snake Optimization | Benchmark for MSPOA | A standard benchmark algorithm [6]. |

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Placement Optimization

Protocol 1: Genetic Programming for Optimal Sensor Placement

This protocol details a method to find the minimal number of sensors required for effective greenhouse monitoring and control [18].

- Reference Data Collection: Distribute a large number of sensors (e.g., 56 dual temperature/humidity sensors) evenly throughout the greenhouse to collect initial microclimate data [18].

- Data Aggregation: Create a reference microclimate value for each time stamp by calculating the weighted average of all sensor measurements. This value serves as the "ground truth" for the entire facility [18].

- Genetic Programming (GP) Model Training: Use Genetic Programming to evolve mathematical models. The inputs are data from a subset of the sensor locations, and the output is the aggregated reference value. GP will automatically select which sensor locations to use in the model [18].

- Model Validation: Evaluate the best-evolved GP model using statistical metrics like Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). A successful model will achieve a correlation very close to 1.0 (e.g., r = 0.999) with a low RMSE, indicating that the selected small subset of sensors (e.g., 8) can accurately represent the whole environment [18].

Protocol 2: AI and Clustering for Microclimate Monitoring

This protocol uses machine learning to identify zones with similar climatic behavior for optimized sensor placement [19].

- Preliminary Data Gathering: Collect initial temperature data from across the field or use existing high-resolution microclimate models [19].

- Cluster Analysis: Apply the K-means clustering algorithm to the spatial data to group locations into distinct clusters based on similar temperature profiles [19].

- Sensor Deployment: Place one sensor within each identified cluster to represent that specific microclimate zone [19].

- Validation via Prediction: Use a neural network (e.g., Nhits) to make temperature predictions based on data from the deployed sensors. Validate the placement by confirming that predictions are consistent and accurate within each cluster, proving the sensor network captures the area's variability [19].

Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates a generalized workflow for optimizing sensor placement in an AWSN, integrating concepts from the experimental protocols.

Diagram 1: AWSN Placement Optimization Workflow

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for AWSN Experiments

| Item / Solution | Function in AWSN Research |

|---|---|

| Multi-Strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm (MSPOA) | An advanced bio-inspired algorithm used to solve the sensor deployment problem, maximizing coverage and avoiding local optimal solutions [6]. |

| Genetic Programming (GP) | An evolutionary algorithm that can automatically select optimal sensor locations and derive a model to aggregate their data into a representative whole-field value [18]. |

| K-means Clustering | A machine learning algorithm used to partition a field into distinct zones with similar microclimatic behavior, guiding strategic sensor placement [19]. |

| Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) | A multi-objective optimization algorithm ideal for balancing competing goals, such as maximizing detection accuracy while minimizing the number of sensors deployed [20]. |

| Convex Optimization & Cost-Minimization Algorithms | A set of mathematical techniques used in spatial planning methodologies to determine sensor numbers and positions under budget and terrain constraints [15]. |

Core Concepts in Sensor Coverage Optimization

Optimizing sensor network coverage is a foundational challenge in precision agriculture research. The goal is to deploy sensors in a manner that ensures complete or partial coverage of a target area, fulfilling specific monitoring requirements while minimizing the number of deployed sensors to manage costs and energy consumption [6]. This involves strategic placement to overcome issues like coverage holes—areas lacking sensor coverage—which can arise from sensor failures or environmental interference [21]. Effective optimization directly impacts the cost, energy consumption, and overall performance of the agricultural monitoring network [6].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: My sensor network has persistent "coverage holes." What are the advanced methods to identify and rectify them?

- Answer: Coverage holes, or areas without monitoring, can significantly reduce data quality. Beyond checking individual sensor functionality, you can employ mathematical frameworks from algebraic topology.

- Methodology: Model your sensor network as a Rips complex, a concept from graph theory. Using principles from simplicial homology, you can algorithmically verify the presence of holes. Furthermore, linear programming techniques can be used to precisely identify the locations of these coverage holes [21].

- Solution: Once identified, a hole removal heuristic can determine the minimal number of sensors and their optimal locations needed to achieve complete coverage. This approach is also adaptable to hybrid networks where mobile sensors or autonomous agents can be deployed to fill the gaps [21].

FAQ 2: How can I determine the optimal number and placement of sensors for a new experimental field?

- Answer: An effective sensor spatial planning methodology combines statistical analysis with optimization techniques.

- Procedure: Begin by analyzing the statistical properties of any existing spatial data for the field (e.g., historical yield maps, soil electrical conductivity). The goal is to maximize captured variance and maintain the mean value to ensure comprehensive data representation. For areas without pre-existing maps, apply a cost-minimization algorithm that incorporates terrain, accessibility, and installation costs [15].

- Technique: Use weighted subsampling and soft clustering to identify key locations that adequately describe distributed values. This approach reduces sensor density while maintaining data integrity and ensures critical areas receive sufficient coverage [15].

FAQ 3: My low-cost capacitive soil moisture sensors show high variability in field readings. How can I improve their reliability?

- Answer: Variability in capacitive sensor readings is often due to soil-specific factors and sensor placement rather than the sensor itself.

- Root Cause: These sensors are sensitive to their local environment, including factors like gravel content, soil salinity, bulk density, and their precise position relative to irrigation drippers. Laboratory calibration is often insufficient for field conditions [22].

- Solution: Implement in-situ field calibration. Develop a dense network of sensors and calibrate them against the gravimetric method (direct soil sampling and drying) within your specific field. Studies show that after soil-specific calibration, low-cost capacitive sensors can perform on par with commercial units, with Spearman rank correlation coefficients exceeding 0.98 [22].

FAQ 4: Which optimization algorithm should I select for large-scale sensor deployment to avoid local optima?

- Answer: Traditional algorithms often suffer from premature convergence. For large-scale deployments (an NP-hard problem), newer metaheuristic algorithms show superior performance.

- Recommendation: Consider the Multi-strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm (MSPOA). It integrates several strategies to enhance global search capability:

- Good Point Set Strategy: For population initialization, expanding the search range.

- 3D Spiral Lévy Flight Strategy: Improves convergence speed and helps escape local optima.

- Adaptive T-distribution Variation Strategy: Enhances global search ability and balance [6].

- Performance: Comparative experiments have shown MSPOA can improve network coverage by 5.85% to 21.05% over algorithms like Improved Artificial Bee Colony (IABC) and Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization (APSO) [6].

- Recommendation: Consider the Multi-strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm (MSPOA). It integrates several strategies to enhance global search capability:

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Placement Optimization

Protocol 1: Simplicial Homology for Coverage Hole Detection and Removal

This protocol provides a mathematical framework for identifying and rectifying areas without sensor coverage [21].

- Network Modeling: Model the sensor network as a Rips complex based on the communication ranges of the sensors.

- Hole Verification: Apply algorithms from simplicial homology to the Rips complex to verify the presence of coverage holes.

- Hole Localization: Use a linear programming model to identify the precise geographic locations and boundaries of the detected coverage holes.

- Rectification Planning: Run a hole removal heuristic to calculate the minimal set of new sensor positions required to achieve complete coverage. This can include coordinates for static sensor placement or waypoints for mobile sensors.

The following workflow outlines the computational process for detecting and removing coverage holes.

Protocol 2: Spatial Planning for Optimal Sensor Placement

This methodology focuses on determining the number and location of sensors to maximize data quality and coverage while considering constraints [15].

- Data Acquisition: Gather existing spatial maps of the area (e.g., soil type, elevation, historical productivity). If no data exists, proceed to step 3.

- Statistical Analysis & Clustering: For areas with existing data, analyze the dataset to maximize variance and maintain the mean. Use soft clustering algorithms to identify locations that best represent the statistical distribution of the data.

- Cost-Minimization Placement: For areas without data, use an in-house cost-minimization algorithm. Input constraints such as terrain, accessibility, and budget to generate potential sensor locations.

- Validation: Deploy sensors at the identified optimal locations. Use the collected data to train a neural network (e.g., Nhits) to predict environmental variables. Validate that predictions are consistent within each clustered zone to confirm placement effectiveness.

Quantitative Performance Data

The table below summarizes the performance of a novel optimization algorithm compared to existing methods, demonstrating significant improvements in network coverage.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Optimization Algorithms for Sensor Network Coverage [6]

| Optimization Algorithm | Abbreviation | Reported Coverage Improvement | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm | MSPOA | Baseline | Integrates good point set, 3D spiral Lévy flight, and adaptive T-distribution strategies for balanced global and local search. |

| Improved Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm | IABC | 5.85% lower than MSPOA | A bio-inspired algorithm; may struggle with local convergence in complex deployments. |

| Chaotic Adaptive Firefly Optimization Algorithm | CAFA | 11.33% lower than MSPOA | Global search capability; can be sensitive to initial parameters and may have slow convergence. |

| Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization | APSO | 21.05% lower than MSPOA | A popular swarm intelligence algorithm; can suffer from premature convergence. |

| Lévy Flight Strategy Chaotic Snake Algorithm | LCSO | 20.66% lower than MSPOA | A newer bio-inspired algorithm incorporating chaotic maps and Lévy flights. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Technologies for Sensor Coverage Research

| Item / Technology | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Capacitive Soil Moisture Sensor (e.g., SEN0193) | A low-cost sensor for measuring volumetric water content. Requires field-specific calibration for reliable data [22]. |

| Rips Complex / Simplicial Homology | A mathematical framework from algebraic topology used to model sensor networks and rigorously detect coverage holes [21]. |

| Multi-strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm (MSPOA) | A advanced metaheuristic algorithm used to solve the NP-hard problem of sensor deployment by maximizing coverage and avoiding local optima [6]. |

| Clustering Algorithms (e.g., K-means, Soft Clustering) | Machine learning techniques used to identify spatial locations with similar environmental characteristics, guiding optimal sensor placement [19] [15]. |

| IoT (Internet of Things) Platform | A network platform that enables remote monitoring, data collection from sensors, and often integrates with control systems for automated interventions [23]. |

Advanced Algorithms and Computational Strategies for Optimal Placement

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between traditional and heuristic sensor placement methods? Traditional methods for optimal sensor placement (OSP) are often based on rigorous mathematical optimization frameworks. These can be formulated as combinatorial problems where the goal is to select a subset of sensor locations from a larger set of candidates to minimize or maximize an objective function, such as the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) or the Modal Assurance Criterion (MAC) [24]. In contrast, heuristic methods leverage simpler, often computationally efficient rules or features to find good, though not necessarily perfect, solutions. For instance, in human activity recognition, simple heuristic features extracted from accelerometer data can make the system more robust to variations in sensor orientation and placement [25].

Q2: Why are sensor placement problems considered computationally challenging? Sensor placement is often classified as an NP-hard problem. This means that as the number of potential sensor locations increases, the computational time required to find the guaranteed best solution grows exponentially. It has been proven that finding the smallest number of sensors to make a system observable is NP-hard [26]. This intrinsic complexity necessitates the use of approximate or heuristic methods, especially for large-scale systems like those found in agricultural monitoring.

Q3: What are the key limitations of Boolean (or binary) models in sensor placement? Boolean models, which might consider a sensor as either placed or not placed at a location, often form the basis of the combinatorial optimization problem. The primary limitation is the computational complexity (NP-hardness) of searching through all possible combinations of sensor locations to find the optimal one [26]. Furthermore, these models can struggle to incorporate real-world uncertainties, such as sensor failure or fluctuating environmental conditions, which are critical in outdoor agricultural settings.

Q4: How do probabilistic models address the limitations of simpler models? Probabilistic models explicitly account for uncertainty in sensor performance and system parameters. They can be formulated as stochastic or robust optimization problems to ensure the sensor network remains effective even when parameters drift or sensors fail [27]. For example, a probabilistic framework can help design a network that is resilient to the failure of a wireless communication node or a false negative from a flame detector [27].

Q5: What specific challenges arise when applying these methods to precision agriculture? In precision agriculture, challenges include the large scale of fields, the dynamic nature of crops, and environmental variability. Sensor placement must account for soil heterogeneity, crop health, and microclimates [28] [29]. Traditional methods may be too rigid or computationally expensive for these vast, variable environments, making heuristic and data-driven approaches more practical. Integrating data from various sensors like soil moisture probes and weather stations adds another layer of complexity to the placement strategy [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor System Observability Despite Numerous Sensors

- Symptoms: Inability to accurately reconstruct the full state of the system (e.g., complete soil moisture map, overall crop health) from sensor measurements.

- Possible Causes:

- Solutions:

- Re-evaluate Placement Strategy: Employ a graph-theoretic approach to ensure structural observability. This involves analyzing the system's network structure to place sensors so that all critical states can be inferred [26].

- Use Advanced Metrics: Formulate the objective function using the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) to maximize the information content of your measurements [24].

- Implement a Greedy Algorithm: For large-scale problems, use a greedy algorithm that sequentially selects the next best sensor location. This provides a computationally feasible

(1-1/e)-approximate solution to the NP-hard problem [26].

Problem 2: System Performance Degrades Under Real-World Uncertainties

- Symptoms: Sensor network performance is satisfactory in simulations but deteriorates in the field due to sensor failure, communication dropouts, or environmental noise.

- Possible Causes:

- Deterministic Modeling: The placement model does not account for probabilistic failures or parameter uncertainties [27].

- Solutions:

- Adopt a Robust Framework: Reformulate the OSP as a robust optimization problem or a stochastic program. This tailors the model to handle uncertainties in sensor performance and system parameters, a key advancement over classical facility location problems [27].

- Incorporate Redundancy: The probabilistic model will naturally suggest placements with built-in redundancy to mitigate the risk of single-point failures [27].

Problem 3: Sensor Data is Inconsistent Due to Orientation and Calibration Issues

- Symptoms: High variance in data for the same activity or condition (e.g., the same walking activity produces different signals).

- Possible Causes:

- Sensor Orientation Variance: The signal from an accelerometer or other sensor is highly dependent on its orientation [25].

- Solutions:

- Extract Heuristic Features: Instead of using raw sensor data, employ simple heuristic features that are inherently less sensitive to sensor orientation and placement. These features can then be used with a machine learning model (e.g., a 1D-CNN-LSTM) for consistent activity recognition [25].

Problem 4: Computational Intractability for Large-Scale Agricultural Fields

- Symptoms: The optimization algorithm takes too long to find a solution or fails to converge for a large number of candidate sensor locations.

- Possible Causes:

- NP-Hard Nature: The problem is fundamentally complex and becomes prohibitively difficult for exact solvers as the field size increases [26].

- Solutions:

- Leverage Mode Decomposition: Use methods like Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) to create a lower-dimensional representation of the system (e.g., a flow field or soil property map). The OSP can then be solved more efficiently in this reduced space using techniques like QR-pivoting [30].

- Utilize Deep Learning: Employ concrete autoencoders (CAEs) or other neural network-based embedded feature selection methods for an end-to-end differentiable framework that can handle problems with many degrees of freedom [30].

Experimental Protocols and Data

Table 1: Common Objective Functions for Sensor Placement Optimization

| Objective Function | Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) | Maximizes the information content from measurements; often by maximizing the determinant of FIM [24]. | Dynamic identification in structural health monitoring [24]. |

| Modal Assurance Criterion (MAC) | Places sensors to ensure that mode shapes are linearly independent; minimizes off-diagonal values [24]. | Vibration testing and modal analysis in structures [24]. |

| Structural Observability Index | Ensures the system's states can be recovered from outputs; focuses on the system's graph structure [26]. | Large-scale networked systems, including agriculture [26]. |

| Shapley Value | A game-theoretic approach to rank the contribution of each candidate sensor location to the overall reconstruction accuracy [30]. | Sparse reconstruction of turbulent flows in urban environments [30]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Sensor Placement Methodologies

| Methodology | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boolean/Combinatorial (Traditional) | Formulates placement as a discrete optimization problem (e.g., a Knapsack problem) [24]. | Mathematically rigorous; provides an optimal solution for small problems. | NP-hard; computationally intractable for large-scale systems [24] [26]. |

| Probabilistic (Traditional) | Models uncertainties in sensor performance and system parameters using stochastic programs [27]. | More resilient to real-world failures and noise. | Increased model complexity; can be computationally demanding. |

| Heuristic Features (Heuristic) | Uses simple, orientation-invariant features from raw sensor data [25]. | Computationally efficient; robust to sensor orientation problems. | May not be globally optimal; requires domain knowledge to design effective features. |

| Greedy Algorithm (Heuristic) | Sequentially selects the next best sensor location based on a defined metric [26]. | Computationally efficient with a proven performance bound. | The solution is an approximation and can be myopic. |

| Diffusion-based Models (Modern Heuristic) | Uses a generative diffusion model as a probabilistic prior for the system state, enabling sparse reconstruction and sensor placement [30]. | High-fidelity reconstruction; handles stochastic systems well. | Requires a large, high-fidelity dataset for training the generative model. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Sensor Placement Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Pyomo | A Python-based optimization modeling language used to formulate and solve mixed-integer linear and nonlinear sensor placement programs [27]. |

| Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) | A modal analysis technique that reduces the dimensionality of a system, facilitating the solution of OSP problems in a lower-dimensional space [30]. |

| Concrete Autoencoders (CAEs) | A deep learning framework that provides an end-to-end differentiable method for selecting the most informative features/sensor locations from high-dimensional data [30]. |

| Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) | A game-theoretic framework adapted to attribute value and rank candidate sensor locations based on their contribution to reconstruction accuracy [30]. |

| Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) | A mathematical object used to quantify the amount of information that measurements carry about the parameters being estimated; its maximization is a common OSP goal [24]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers conducting experiments in bio-inspired optimization algorithms, specifically within the context of optimizing sensor placement for maximum crop coverage in agricultural wireless sensor networks (AWSNs).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My optimization algorithm converges to a suboptimal sensor layout with persistent coverage gaps. What strategies can help escape these local optima? Local optima convergence is a common challenge where the algorithm settles on a solution that is good but not the best, leaving areas of the field unmonitored.

- Solution: Implement mechanisms that enhance global exploration. The Multi-Strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm (MSPOA) tackles this by integrating a 3D spiral Lévy flight strategy. This strategy combines long-distance jumps (Lévy flight) with local spiral search, helping the algorithm escape local optima and explore a broader search space [31] [6]. Alternatively, you can incorporate adaptive T-distribution variation into your algorithm, which perturbs candidate solutions based on the iteration count, boosting global search ability in earlier stages [31].

Q2: How can I improve the slow convergence speed of my bio-inspired algorithm, especially for large-scale agricultural fields? Slow convergence increases computational time and cost, which is critical for large-scale deployments.

- Solution: Focus on improving population initialization and local search. Using a good point set strategy for initializing the population of candidate solutions can provide a more uniform distribution across the search space from the start, enhancing stability and accelerating convergence performance [31] [6]. Furthermore, the velocity-scaled adaptive search factor in a modified PSO algorithm can dynamically guide the search process, leading to faster convergence [32].

Q3: What is the best way to handle dynamic changes in the agricultural environment, such as sensor failures or changing weather patterns? Static deployment strategies may become inefficient when network conditions change.

- Solution: Employ algorithms designed for adaptability and robustness. The pelican-inspired movement and collaboration strategies in MSPOA are noted for enhancing adaptability and robustness in diverse and dynamic agricultural scenarios [31]. For networks with mobile nodes, a Multi-Objective Optimization-based Data Gathering Protocol (MOO-DGP) can be used. It balances factors like velocity, link quality, and energy consumption to maintain optimal coverage despite node movement [33].

Q4: For a heterogeneous WSN with different sensor types and sensing ranges, how can I optimize cluster head selection to save energy? Selecting the wrong cluster heads can lead to rapid energy depletion and reduced network lifetime.

- Solution: Use hybrid metaheuristics to solve this NP-hard problem. A Hybrid Biologically-Inspired Optimization Algorithm (HBIP) combines the strong global exploration of the Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) algorithm with the powerful local exploitation of the Bacterial Foraging Optimization (BFO) algorithm. This hybrid approach optimizes cluster head selection to minimize overall network energy consumption [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Premature Convergence in Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

Symptoms: The algorithm's fitness score stops improving early in the process, leading to a low coverage rate and an uneven distribution of sensor nodes [32].

Diagnosis and Steps for Resolution:

- Verify Population Diversity Metrics: Check the diversity of your particle swarm in the search space after the first 50 iterations. Low diversity indicates premature convergence.

- Implement a Dynamic Mechanism: Switch from a standard PSO to an advanced variant like Velocity-Scaled Adaptive Search Factor PSO (VASF-PSO). This algorithm integrates dynamic mechanisms to enhance population diversity and guide the search process more effectively [32].

- Adjust Parameters: Within VASF-PSO, ensure the velocity scaling factor is adaptive. This helps particles escape local optima by balancing exploration and exploitation based on the search progress [32].

Problem: Coverage Gaps After Initial Sensor Deployment

Symptoms: The evaluation of the sensor network shows uncovered areas ("holes") where no sensor can monitor crop conditions, even though the theoretical model predicted full coverage [34] [32].

Diagnosis and Steps for Resolution:

- Recalculate Covered Area Precisely: Use an exact integral calculation or a fine grid-based method for the fitness function to compute the covered area accurately, rather than relying on approximations [34].

- Apply a Hybrid GA Approach: If using a Genetic Algorithm (GA), integrate it with a local search technique. A Modified IGA (MIGA) combines a new individual representation with a local search (like Virtual Force Algorithm, VFA) to fine-tune sensor positions and eliminate small coverage gaps [34].

- Validate with a Different Coverage Model: Test the final deployment using a probabilistic perception model, which considers signal attenuation and may more accurately reflect coverage in real-world agricultural environments with obstacles [31] [6].

Problem: Unbalanced Energy Consumption in Clustered WSNs

Symptoms: Cluster Head (CH) nodes deplete their energy much faster than member nodes, causing early network partition and data loss [33].

Diagnosis and Steps for Resolution:

- Profile Energy Drain: Monitor the energy consumption of all nodes to confirm that CHs are the bottleneck.

- Optimize CH Selection with a Hybrid Algorithm: Implement the HBIP algorithm for cluster head election. Its improved balance between exploration and exploitation helps select CHs that minimize the network's total energy consumption, thereby prolonging network lifetime [33].

- Incorporate a Realistic Energy Model: In your simulation or calculation, use a realistic low-power radio transceiver model (e.g., based on the IEEE 802.15.4 standard, like the CC2538) to accurately calculate energy dissipation during transmission and reception [33].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Evaluating MSPOA for AWSN Coverage Optimization

This protocol outlines the methodology for comparing the Multi-Strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm against other algorithms [31] [6].

1. Objective: To maximize the coverage rate of a wireless sensor network in a large-scale agricultural field using MSPOA. 2. Simulation Setup: * Monitoring Area: A two-dimensional rectangular region. * Sensor Nodes: Deploy a set number of homogeneous nodes with a defined sensing radius (Rs) and communication radius (Rc). * Coverage Model: Use a probabilistic perception model where the coverage probability of a point by a sensor decreases with increasing distance. 3. Algorithm Configuration (MSPOA): * Population Initialization: Use the good point set strategy to generate the initial candidate solutions. * Position Update: Apply the 3D spiral Lévy flight strategy during the global search phase. * Solution Refinement: Use the adaptive T-distribution variation strategy to update pelican positions and enhance search accuracy. 4. Comparative Analysis: Run simulations comparing MSPOA against benchmark algorithms (IABC, CAFA, APSO, LCSO) under identical conditions. 5. Metrics: Record the final coverage rate, convergence speed, and algorithm stability over multiple runs.

Protocol 2: Deploying VASF-PSO for Continuous Coverage

This protocol describes the use of a modified PSO for sensor deployment to minimize uncovered areas [32].

1. Objective: To achieve continuous coverage in a WSN by optimizing sensor node placement using VASF-PSO. 2. Simulation Setup: * Area & Nodes: Define the size of the monitoring area and the number of sensor nodes with a fixed sensing range. * Coverage Model: A Boolean disk model, where a point is covered if it is within the sensing radius of at least one sensor. 3. Algorithm Configuration (VASF-PSO): * Velocity Update: Implement a dynamic velocity-scaling factor to adaptively control the search behavior of particles. * Fitness Function: The fitness of a particle (sensor deployment layout) is the total area covered, calculated to minimize overlap and gaps. 4. Execution: Run the VASF-PSO algorithm for a set number of iterations or until convergence. 5. Validation: Compare the coverage rate and convergence speed with baseline PSO and other metaheuristics.

Performance Comparison of Bio-Inspired Algorithms

The following table summarizes quantitative data from recent studies on the performance of various algorithms in WSN coverage optimization.

| Algorithm | Full Name | Average Coverage Improvement vs. Benchmarks | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSPOA | Multi-Strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm [31] [6] | 5.85% - 21.05% | Superior global search, fast convergence, high stability in dynamic environments. |

| VASF-PSO | Velocity-scaled Adaptive Search Factor PSO [32] | Up to 14.71% | Enhanced population diversity, reduced premature convergence. |

| HBIP | Hybrid Biologically-Inspired Protocol [33] | Data collection increased by 7.26% over ABC | Optimizes energy consumption, extends network lifetime. |

| GA-based | Genetic Algorithm [34] | Effective coverage with limited nodes | Good for finding optimal placement with exact area calculation. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of the Multi-Strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm (MSPOA) for sensor deployment.

MSPOA Sensor Deployment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key computational "reagents" – algorithms, models, and strategies – essential for experiments in bio-inspired optimization for sensor networks.

| Research Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Multi-Strategy POA (MSPOA) | A core optimization algorithm that balances global and local search for superior sensor placement and coverage [31] [6]. |

| Probabilistic Perception Model | A coverage model that provides a more realistic evaluation of sensor performance by accounting for signal attenuation with distance [31] [6]. |

| Boolean Disk Model | A simplified coverage model where a point is covered if it is within a sensor's fixed-radius disk. Useful for initial algorithm testing [34]. |

| Lévy Flight Strategy | A movement pattern used in algorithms to incorporate long jumps, helping to escape local optima during the global search phase [31] [6]. |

| Velocity-Scaled Adaptive Search Factor (VASF) | A dynamic parameter in PSO that adjusts how particles explore the search space, improving convergence and final coverage [32]. |

| Good Point Set Strategy | An initialization method for generating a uniform initial population of candidate solutions, improving algorithm stability and performance [31] [6]. |

| Hybrid Biologically-Inspired Algorithm (HBIP) | An algorithm combining ABC and BFO, used for optimizing cluster head selection to minimize energy consumption in data gathering [33]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

This guide addresses specific challenges you might encounter when implementing genetic programming (GP) for greenhouse sensor placement and control.

Problem 1: GP Model Exhibits Non-Gradual Evolution and Poor Convergence

- Symptoms: The fitness of your population shows wild fluctuations between generations instead of improving steadily. The evolved programs are large and complex but perform poorly on test data.

- Causes: This is a known issue in standard GP due to the non-locality of its representation and operators. A small syntactic change in a program tree (like changing a single function node) can cause a massive, non-gradual shift in its semantic behavior (the output) [35].

- Solutions:

- Implement Semantic Operators: Adopt algorithms like Semantic Schema-based Genetic Programming (SBGP), which partitions the semantic search space and uses local search operators to guide evolution more gradually toward better solutions [35].

- Verify Primitive Set: Ensure your function and terminal sets are appropriate for the problem. Using domain-specific functions can constrain the search space to more meaningful areas.

Problem 2: Optimized Sensor Placement Does Not Lead to Effective Control

- Symptoms: Despite a high correlation with reference data, the control system using the reduced sensor set fails to maintain a stable greenhouse environment.

- Causes: Many optimal sensor placement methods are designed from a monitoring perspective, not a control perspective. The selected sensor locations might not capture the critical control inputs for the greenhouse actuators [36].

- Solutions:

- Define Reference from a Control Perspective: Follow the methodology in the foundational research. Create a reference micro-climate signal by aggregating data from a dense sensor network (e.g., 56 sensors). Use this aggregated signal as the target for your GP to model [36] [37].

- Validate for Control: Test your evolved model not just on correlation metrics, but in a simulated control loop to ensure it provides the necessary feedback for stable control.

Problem 3: Evolved Models are Overly Complex and Do Not Generalize

- Symptoms: The program tree performs well on training data but fails on unseen validation data, a sign of overfitting.

- Causes: This is often a result of code bloat, where introns (non-functional code) proliferate in the population without improving actual performance [35].

- Solutions:

- Use Parsimony Pressure: Introduce a penalty for program size (number of nodes) into your fitness function to favor simpler, more generalizable models.

- Employ Semantic Approximation: Techniques that simplify the program tree without significantly altering its output can help reduce bloat [35].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is Genetic Programming, and why is it suitable for greenhouse control? Genetic Programming is an evolutionary computation technique that evolves computer programs to solve problems. It is inspired by biological evolution, using mechanisms like selection, crossover (recombination), and mutation on a population of program trees [38] [39]. It is highly suitable for greenhouse control because it can perform symbolic regression. This means it can discover a mathematically interpretable formula that optimally aggregates data from a minimal set of sensors to accurately represent the overall greenhouse climate, which is vital for efficient control [36] [37].

Q2: How many sensors can I expect to eliminate using this GP method? Research demonstrates that a GP approach can achieve a massive reduction in required hardware. One study using data from 56 sensors showed that a model using only 8 strategically placed sensors could estimate the overall greenhouse condition with an average correlation of 0.999 and very low error (e.g., RMSE of 0.0822°C for temperature) [36] [37]. The exact number will depend on your specific greenhouse layout and environmental dynamics.

Q3: My background is in agriculture, not computer science. What are the key components I need to set up a GP experiment? You will need to define the following core components for your GP system:

- Terminal Set: The variables and constants used by the programs. In greenhouse control, these are your sensor readings (e.g., Temp1, Humidity5) and random constants [36].

- Function Set: The mathematical operators used to build programs, such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, and protected division.

- Fitness Function: A metric that evaluates how good a program is. For symbolic regression, this is often the error (e.g., Root Mean Square Error) between the program's output and the reference greenhouse climate value [36] [35].

- GP Parameters: Settings like population size, number of generations, and probabilities for crossover and mutation.

Q4: Are there any open-source tools to help me get started? Yes. Frameworks like OakGP, an open-source type-safe GP system written in Java, can significantly lower the barrier to entry. It provides the core infrastructure, allowing you to focus on defining your specific problem [39].

Q5: The optimal sensor locations change with the season. How does GP handle this? This is a key insight. Research confirms that the importance of specific sensor locations for accurately estimating the greenhouse climate varies from month to month [36]. A robust GP methodology involves training and validating your models on data that encompasses different planting seasons and weather conditions. You may end up with a unique sensor configuration or aggregation formula for each major seasonal period [36].

Experimental Protocol: GP for Optimal Sensor Placement

This protocol outlines the methodology based on published research [36] [37].

1. Data Collection and Pre-processing

- Sensor Deployment: Deploy a high-density network of sensors (e.g., 56 dual temperature and humidity sensors) throughout the greenhouse to capture spatial climate variation.

- Data Logging: Collect data at a high frequency (e.g., per minute) over a period that covers different seasons and weather conditions.

- Data Cleaning: Handle missing values and remove obvious outliers from the dataset.

2. Definition of Reference Micro-climate

- Aggregation: Calculate a reference temperature and humidity value for each time stamp by aggregating data from all sensors. A weighted averaging method is typically used. This aggregated value is considered the "ground truth" for the overall greenhouse condition and serves as the target for the GP to learn [36].

3. Configuration of the Genetic Programming System

- Terminal Set:

{S1, S2, ..., Sn, R}, whereS_iis the reading from the i-th sensor andRis a set of random constants. - Function Set:

{+, -, *, %}, where%is protected division (returns 1 if divided by zero). - Fitness Function: Minimize the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between the program's output and the reference aggregated value.

- Parameters: Typical settings include a population size of 500-1000, 50-100 generations, crossover probability of 80-90%, and mutation probability of 1-5%.

4. Execution and Model Evolution

- Initialization: Generate an initial population of random program trees.

- Evaluation: Calculate the fitness of every individual in the population.

- Selection: Use a selection strategy (e.g., tournament selection) to choose fitter individuals as parents.

- Genetic Operations: Create a new generation by applying crossover and mutation to the parents.

- Crossover: Swaps randomly selected subtrees between two parent programs.

- Mutation: Randomly changes a node in a program tree to another valid function or terminal.

- Termination: Repeat steps 2-4 until a termination criterion is met (e.g., a maximum number of generations or a fitness threshold is reached).

5. Validation and Deployment

- Validation: Test the best-evolved model from the training phase on a completely unseen test dataset.

- Interpretation: Analyze the final model to identify which sensors are used. The set of sensors present in the model constitutes the optimal placement for monitoring and control.

- Deployment: Physically install sensors at the identified optimal locations and use the evolved formula to aggregate their readings for the greenhouse control system.

The workflow for this experimental protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Performance Metrics from Foundational Research

The following table quantifies the performance you can expect from a properly configured GP system for greenhouse monitoring, as demonstrated in the key study [36] [37].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of the Evolved GP Model for Greenhouse Monitoring

| Micro-climate Variable | Average Pearson's Correlation (r) | Average RMSE | Number of Sensors Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 0.999 | 0.0822 | 8 (from an initial 56) |

| Relative Humidity | 0.999 | 0.2534 | 8 (from an initial 56) |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Components for Your Experiment

This table details the key "research reagents," or essential materials and tools, required to conduct experiments in GP for greenhouse control.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Item | Function / Purpose | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Density Sensor Network | To collect the initial spatial micro-climate data required for defining the reference signal and training the GP model. | 56+ dual temperature and humidity sensors distributed in a grid [36]. |

| Data Acquisition System | To log and store sensor measurements at a high frequency for extended periods. | Systems capable of handling data from all sensors per minute over multiple months [36]. |

| Genetic Programming Framework | Provides the core algorithms for evolving the sensor aggregation formulas. | Open-source frameworks like OakGP [39] or custom implementations in languages like Python, Java, or Lisp. |

| Computational Resources | To run the evolution process, which can be computationally intensive for large populations and many generations. | A standard desktop computer is often sufficient for problems of this scale. |

| Function & Terminal Primitives | The building blocks from which GP constructs candidate solutions (programs). | Terminals: Sensor readings (e.g., S1, S2). Functions: Arithmetic operators (+, -, *, %). |

| Fitness Function | The objective that guides the evolutionary search toward optimal solutions. | Typically based on error minimization (e.g., RMSE) between the program's output and the aggregated reference value [36] [35]. |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Hub

This section addresses frequently asked questions and common experimental challenges encountered when implementing the Multi-Strategy Pelican Optimization Algorithm (MSPOA) for sensor network coverage optimization.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary innovation of the MSPOA compared to the original Pelican Optimization Algorithm (POA)?

- A: The MSPOA enhances the original POA by integrating three key strategies to overcome its limitations, such as premature convergence and slow processing speed. These are a Good Point Set strategy for superior population initialization, a 3D spiral Lévy flight strategy to enhance global search capabilities and escape local optima, and an adaptive T-distribution variation strategy to improve search accuracy and balance exploration with exploitation [40] [6]. This multi-strategy approach is specifically designed for complex, large-scale optimization problems like sensor deployment in agricultural fields [40].

Q2: My MSPOA implementation is converging to a local optimum instead of the global one. What strategies can I adjust?

- A: Premature convergence often indicates insufficient exploration. Focus on the parameters and mechanisms within the enhanced strategies:

- 3D Spiral Lévy Flight: Verify the implementation of the Lévy flight step size calculations. The inherent long jumps of Lévy flight should help the algorithm escape local optima [40] [6].

- Adaptive T-distribution: This strategy is designed to improve global search ability. Ensure that the variation is applied correctly during the position update phase and that its adaptive parameter (often related to iteration count) is functioning as intended [40].

- Parameter Tuning: Review the parameters controlling the balance between the standard POA attack phases and the newly introduced strategies. Slightly increasing the weight of the Lévy flight or T-distribution steps can encourage more exploratory behavior [6].

- A: Premature convergence often indicates insufficient exploration. Focus on the parameters and mechanisms within the enhanced strategies:

Q3: How does MSPOA's performance compare to other common optimization algorithms in WSN coverage?

- A: Comparative experiments demonstrate that MSPOA provides significant performance improvements. The following table summarizes the recorded coverage rate improvements of MSPOA over other algorithms [40]:

| Comparison Algorithm | Full Name | Coverage Improvement by MSPOA |

|---|---|---|

| IABC | Improved Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm | 5.85% |

| CAFA | Chaotic Adaptive Firefly Optimization Algorithm | 11.33% |

| APSO | Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization | 21.05% |

| LCSO | Lévy Flight Strategy Chaotic Snake Optimization Algorithm | 20.66% |

- Q4: The algorithm's convergence speed seems slow for my large-scale agricultural plot. Any recommendations?

- A: The Good Point Set initialization strategy is designed to create a more uniform and diverse initial population, which should lead to faster convergence. Confirm that this strategy is correctly implemented, as a better initial spread of candidate solutions can reduce the number of iterations needed to find a high-quality solution [40] [6]. Additionally, the 3D spiral Lévy flight also contributes to improving convergence speed alongside global search accuracy [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Oscillation in Coverage Results Between Consecutive Runs

- Potential Cause: The stochastic nature of the Lévy flight and other random operators can lead to varying results, especially if the population diversity is too high in later stages.

- Solution:

- Increase the Number of Iterations: Allow the algorithm more time to stabilize and exploit the best-found regions.