Optimizing Multimodal Imaging for Plant Phenomics: From Data Acquisition to Predictive Insights

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the strategies and technologies driving the optimization of multimodal imaging in plant phenomics.

Optimizing Multimodal Imaging for Plant Phenomics: From Data Acquisition to Predictive Insights

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the strategies and technologies driving the optimization of multimodal imaging in plant phenomics. Aimed at researchers and scientists, it explores the foundational principles of integrating diverse imaging sensors—from 2D to 3D and beyond—to capture the multiscale structure of plants. The scope extends to methodological applications of deep learning and machine learning for trait extraction, tackles critical challenges like data redundancy and image registration, and validates these approaches through comparative analyses with conventional methods. By synthesizing recent advances, this review serves as a guide for developing robust, scalable, and intelligent phenotyping systems capable of operating in real-world agricultural and research environments.

The Multiscale Foundation: Uncovering Plant Structure from Cell to Canopy

FAQs: Core Concepts in Imaging for Plant Phenomics

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between 2D, 2.5D, and 3D imaging?

- 2D Imaging provides a flat, two-dimensional matrix of values (e.g., a standard RGB photograph) with no depth information [1].

- 2.5D Imaging (Depth Map) provides a single distance value for each x-y location in a 2D image. It represents a surface view from a single perspective and cannot detect objects behind the projected surface or resolve overlapping structures [1] [2].

- 3D Imaging results in a full point cloud or vertex mesh with x-y-z coordinates for each data point. This allows the plant to be viewed and analyzed from all angles, enabling the measurement of complex architectural traits and the detection of overlapping leaves [1] [2].

Q2: When should I use a 3D sensor instead of a 2D imaging system? A 3D sensor is essential when you need to measure:

- Plant Architecture: Traits like plant volume, leaf angle, or stem branching patterns [2].

- Growth vs. Movement: To differentiate between true plant growth and diurnal leaf movements in time-series experiments [2].

- Structural Traits for Breeding: Traits fundamental to light interception, such as canopy structure and compactness [3] [1].

- Correction for Spectral Data: When using spectral sensors (e.g., hyperspectral or thermal), 3D information is needed to correct signals for the inclination and distance of plant organs [1].

Q3: What does "multimodal imaging" mean in plant phenomics? Multimodal imaging involves combining two or more different imaging techniques during the same examination to gain a more holistic view of plant health [4]. A common approach in phenomics is to fuse 3D geometric data with spectral information. For example, the MADI platform combines visible, near-infrared, thermal, and chlorophyll fluorescence imaging to simultaneously assess leaf temperature, photosynthetic efficiency, and chlorophyll content [3]. This fusion helps researchers connect plant structure with function.

Q4: My 3D point clouds of plant edges appear blurry. What could be the cause? Blurry edges on plant organs are a known con of LIDAR technology. The laser dot projected on a leaf edge is partly reflected from the leaf and partly from the background. The returning signal averages these two distances, resulting in unsharpened edges in the point cloud [1]. For high-precision measurements of fine edges, consider a different technology like laser light sectioning [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Selecting the Right 3D Sensing Technology

Different 3D sensing technologies are suited for different scales and applications in plant research. The following workflow can help you select the appropriate one.

Sensor Selection Guide

Problem: Inaccurate or low-resolution 3D data due to mismatched sensor technology for the experimental scale or plant type.

Solution: Follow the decision workflow above and refer to the comparison table of technologies.

| Technology | Principle | Best For | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laser Triangulation (LT) [2] | Active; a laser line is projected, and its reflection is captured by a camera at a known angle. | Laboratory environments; single plants; high-accuracy organ-level traits. | Very high resolution and accuracy (microns to millimeters) [2]. | Trade-off between resolution and measurable volume; requires sensor or plant movement [2]. |

| Structure from Motion (SfM) [2] | Passive; 3D model is reconstructed from a set of 2D RGB images taken from different angles. | Field phenotyping (e.g., via UAVs); miniplot scale; low-cost applications [2]. | Low-cost hardware (RGB camera); lightweight, ideal for drones [2]. | High computational effort for reconstruction; results depend on number of images and viewing angles [2]. |

| Laser Light Section [1] | Active; a laser line is projected, and its shift due to object distance is measured. | High-precision measurements of seedlings, small organs, and fine structures [1]. | High precision in all dimensions (up to 0.2 mm); robust with no moving parts [1]. | Requires constant movement (sensor or plant); defined, limited working range [1]. |

| Structured Light (SL) [2] | Active; projects a sequence of light patterns (e.g., grids) and measures deformations. | Laboratory; reverse engineering; quality control of plant organs [2]. | High resolution and accuracy in a larger measuring volume than LT [2]. | Bulky setup; requires multiple images, so sensitive to plant or sensor movement [2]. |

| LIDAR [1] [2] | Active; measures the time-of-flight of a laser dot moved rapidly across the scene. | Field-scale phenotyping; airborne vehicles; large volumes [1]. | Fast acquisition; long-range (2m-100m); works day and night [1]. | Poor X-Y resolution; bad edge detection; requires warm-up time and calibration [1]. |

| Time-of-Flight (ToF) [2] | Active; measures the round-trip time for light to hit the object and return. | Indoor navigation; gaming; low-resolution plant canopy overview [2]. | Compact hardware; can capture depth in a single shot. | Low spatial resolution; slower than other methods [2]. |

Guide 2: Addressing Common Data Quality Issues

Problem: Low Contrast in Multimodal Images Background: This issue is critical not only for visual interpretation but also for automated segmentation and analysis algorithms. Sufficient contrast is a prerequisite for robust data processing [5]. Troubleshooting Steps:

- Calibrate Sensors: Ensure all cameras (RGB, thermal, etc.) are properly calibrated and aligned according to the manufacturer's and platform's protocols [3].

- Control Lighting: For active sensors, this may not apply. For passive sensors like RGB cameras, use controlled, uniform illumination within an imaging box to minimize shadows and specular reflections [3].

- Pre-process Images: Apply standard image processing techniques to enhance contrast. In one study, contrast quality control based on deep learning models was used to improve segmentation tasks for stroke lesions in CT, a concept transferable to plant imaging [5].

- Verify Fusion Algorithms: If the problem persists in fused images, check the underlying fusion algorithm. Advanced deep learning frameworks (e.g., PPMF-Net) are designed to mitigate issues like structural blurring and loss of fine details that can reduce perceived contrast [6].

Problem: Inaccurate Trait Extraction from 3D Point Clouds Background: Deriving biological insights requires accurate segmentation of point clouds into individual organs (leaves, stems) [2]. Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check Point Cloud Quality: Ensure the resolution and accuracy of your point cloud are sufficient for the trait you want to measure. For example, LIDAR may not resolve fine structures like thin stems or ears [1].

- Refine Segmentation Algorithm: Move beyond simple thresholding. Employ machine learning and deep learning methods trained on plant architectures. For example, prompt engineering on visual foundation models has been successfully used for the complex task of segmenting individual, intertwined apple trees in a row [5].

- Validate with Ground Truth: Always validate your automated trait extraction (e.g., leaf area, plant height) against manual measurements or a proven standard tool to quantify accuracy and correct for systematic errors [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key hardware and software solutions used in advanced plant phenotyping experiments.

| Item Name | Function / Role | Example Application in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Multimodal Platform (MADI) [3] | Robotized platform integrating thermal, visible, near-infrared, and chlorophyll fluorescence cameras. | Non-destructive monitoring of lettuce and Arabidopsis under drought, salt, and UV-B stress to uncover early-warning markers [3]. |

| Laser Scanner (PlantEye) [1] | A laser light section scanner using its own light source with special filters for operation in sunlight. | High-precision 3D measurement of plant architecture and growth over time, independent of ambient light conditions [1]. |

| Deep Learning Model (PPMF-Net) [6] | A progressive parallel deep learning framework for fusing images from different modalities (e.g., PET-MRI). | Enhances diagnostic accuracy by integrating complementary information, mitigating issues like unbalanced feature fusion and structural blurring [6]. |

| Visual Foundation Model (OneRosette) [5] | A pre-trained model adapted for plant science via "single plant prompting" to segment plant images. | Segmenting and analyzing symptomatic Arabidopsis thaliana in time-series experiments [5]. |

| Hyperspectral Raman Microscope [5] | A dual-modality instrument combining Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) and Raman spectroscopy. | Fast chemical imaging and analysis of material composition, applied to study bone tissue characteristics [5]. |

Plant phenomics research faces a fundamental challenge: biological processes operate across vastly different spatial and temporal scales, from molecular interactions within cells to canopy-level dynamics in field conditions. The "multiscale imperative" refers to the strategic matching of imaging techniques to the specific biological scales of interest, enabling researchers to connect genomic information to observable traits. This technical support guide provides troubleshooting and methodological frameworks for optimizing multimodal imaging to address this imperative, ensuring that data captured at different scales can be integrated to form a comprehensive understanding of plant function and development.

FAQ: Foundations of Multiscale Plant Imaging

What is the core principle behind multiscale imaging in plant phenomics? Multiscale imaging involves deploying complementary imaging technologies that capture plant characteristics at their appropriate biological scales—from subcellular structures to entire canopies. This approach recognizes that plants possess a complex, multiscale organization with components in both the shoot and root systems that require different imaging modalities for accurate phenotyping [7]. The ultimate goal is to bridge measurements across these scales to understand how processes at one level influence phenomena at another.

Why is multimodal imaging essential for modern plant research? Multimodal imaging combines different types of imaging to provide both anatomical and functional information. While one modality may offer high spatial resolution for anatomical reference, another can provide functional data about physiological processes [7]. For example, combining MRI with PET or depth imaging with thermal imaging allows researchers to correlate structure with function, locating regions of interest for detailed analysis and compartmentalizing different anatomical features that may not be clearly contrasted in a single modality [7].

What are the major data management challenges in multiscale phenotyping? The primary challenges include massive data storage requirements and computational processing demands. High-resolution imaging sensors coupled with motorized scanning systems can produce gigabytes of data from a single imaging run—potentially 10⁶ more than standard imaging resolution requires [7]. Even basic image processing operations become computationally intensive at these scales, necessitating specialized approaches for efficient data handling and analysis.

How does image registration enable multiscale analysis? Image registration is the process of aligning and overlaying multiple images of the same scene taken from different viewpoints, at different times, or by different sensors. This is a critical step in combining imaging modalities, involving the calculation of a transformation matrix that allows superimposition of different modalities with locally accurate matching throughout the images [7]. For large multiscale images, registration is often computed on regions of interest containing landmarks rather than entire images to manage computational costs.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Multiscale Imaging Challenges

Image Registration and Fusion Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solution Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Poor alignment between modalities | • Different spatial resolutions• Non-rigid deformations• Missing corresponding landmarks | • Use scale-invariant feature transforms (SIFT) [7]• Apply TurboReg plugin in ImageJ [7]• Manual landmark selection for critical regions |

| Inconsistent intensity values | • Different sensor responses• Varying illumination conditions• Protocol variations between sessions | • Sensor calibration before each use [8]• Standardized imaging protocols [8]• Reference standards in imaging field |

| Large dataset handling difficulties | • Memory limitations• Processing speed constraints• Storage capacity issues | • Region-of-interest focused analysis [7]• Multiresolution processing approaches [7]• High-performance computing resources |

Scale Transition Challenges

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solution Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Information loss between scales | • Resolution mismatches• Inappropriate sampling intervals• Missing contextual references | • Overlapping spatial sampling [7]• Scale-bridging imaging techniques (e.g., mesoscopy) [7]• Fiducial markers for spatial reference |

| Temporal misalignment | • Different acquisition times• Varying temporal resolution• Plant movement between sessions | • Synchronized imaging schedules [9]• Motion correction algorithms• Temporal interpolation methods |

| Physiological changes during imaging | • Phototoxicity effects [7]• Growth during extended sessions• Environmental response | • Optimize wavelength, energy, duration of light [7]• Minimize imaging session duration• Environmental control during imaging |

Experimental Protocols: Implementing Multiscale Imaging

Workflow for Correlative Multimodal Imaging

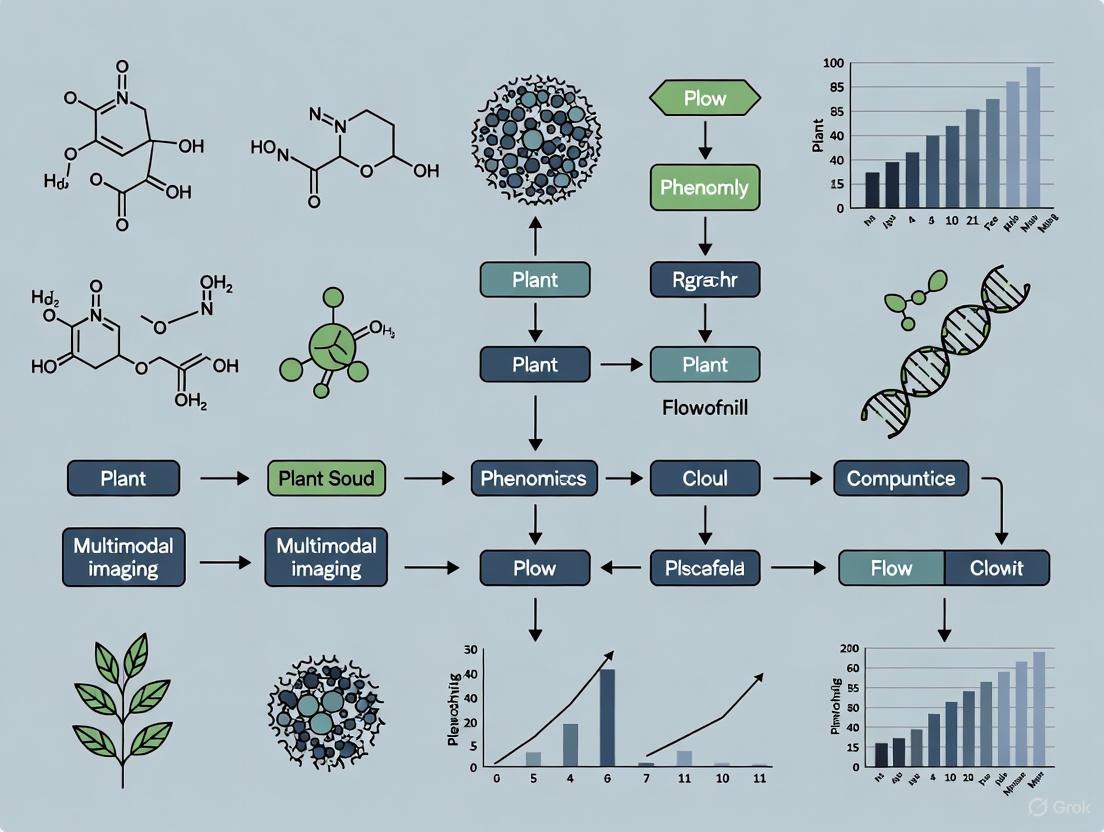

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for conducting multiscale, multimodal imaging experiments:

Scale-Matched Imaging Techniques

The following table summarizes appropriate imaging modalities for different biological scales in plant phenomics:

Table 1: Imaging Techniques Matched to Plant Biological Scales

| Biological Scale | Spatial Resolution | Imaging Techniques | Primary Applications | Example Phenotypes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subcellular | 1 nm - 1 μm | PALM, STORM, STED, TEM, SEM [7] [10] | Protein localization, organelle dynamics, membrane trafficking | ER-Golgi connections, organelle morphology [10] |

| Cellular | 1 - 100 μm | Confocal, LSFM, 3D-SIM, OCT, OPT [7] [10] | Cell division, expansion, differentiation, tissue organization | Cell wall mechanics, vacuole dynamics [10] |

| Organ | 100 μm - 1 cm | MRI, CT, PET, Visible imaging, Fluorescence imaging [7] [8] | Organ development, vascular transport, root architecture | Leaf area, root architecture, fruit morphology [8] |

| Whole Plant | 1 cm - 1 m | RGB imaging, Stereo vision, Thermal IR, Hyperspectral [9] [8] [11] | Growth dynamics, stress responses, architectural phenotyping | Plant height, biomass, canopy temperature [9] [8] |

| Canopy/Field | 1 m - 1 km | UAV, Satellite, Gantry systems [7] [12] [8] | Canopy structure, field performance, resource distribution | Vegetation indices, canopy cover, yield prediction [12] [11] |

Protocol: Multimodal Root System Imaging

Objective: To capture complementary structural and functional data from root systems using integrated imaging approaches.

Materials:

- X-ray Computed Tomography (X-ray CT) system [7] [13]

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) system [7] [8]

- Rhizotron or specialized growth containers [7]

- Image registration software (e.g., ImageJ with TurboReg, TrakEM2) [7]

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Grow plants in specialized containers compatible with both X-ray CT and MRI systems. For molecular imaging, consider transgenic lines expressing fluorescent reporters [13].

Structural Imaging:

Functional Imaging:

Image Registration:

- Identify corresponding landmarks in both modalities.

- Calculate transformation matrix using SIFT features or manual landmark selection [7].

- Apply registration to align functional data with structural reference.

Data Integration:

- Use registered images to compartmentalize anatomical regions (e.g., cotyledon vs. radicle) [7].

- Extract quantitative phenotypes from defined regions of interest.

- Correlate structural features with chemical composition data.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If sample transfer between systems causes displacement, use external fiducial markers.

- For poor contrast in MRI, optimize pulse sequences for plant tissue characteristics.

- If registration fails, employ sequential imaging systems that minimize sample movement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Multiscale Imaging

| Category | Specific Items | Function & Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Probes | GFP, RFP, YFP transgenic lines [10] | Protein localization and trafficking studies | Phototoxicity concerns in live imaging [7] |

| Fixation Reagents | Glutaraldehyde, formaldehyde, FAA | Tissue preservation for electron microscopy | May alter native structure; cryofixation alternatives |

| Embedding Media | LR White, Spurr's resin, OCT compound | Sample support for sectioning and microscopy | Compatibility with imaging modalities (e.g., transparency for optics) |

| Histological Stains | Toluidine blue, Safranin-O, Fast Green | Tissue contrast enhancement for light microscopy | May interfere with fluorescence; test compatibility |

| Immersion Media | Water, glycerol, specialized oils | Refractive index matching for microscopy | Match RI to sample to reduce scattering artifacts |

| Fiducial Markers | Gold nanoparticles, fluorescent beads | Reference points for image registration | Size and contrast appropriate for resolution scale |

| Calibration Standards | Resolution targets, color charts | Instrument calibration and validation | Essential for quantitative cross-comparisons [8] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Workflow for Multiscale Phenotyping Data Integration

The integration of data across scales requires sophisticated computational approaches as shown below:

Emerging Technologies in Multiscale Plant Phenomics

Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced Imaging: Deep learning algorithms such as Super-Resolution Generative Adversarial Networks (SRGAN) and Super-Resolution Residual Networks (SRResNet) are being applied to improve image resolution and extract more quantitative data from standard confocal images [10]. These approaches can identify subtle features like endocytic vesicle boundaries more clearly and enable deeper mining of information contained in images [10].

Chemical Imaging Techniques: Spatially resolved analytical techniques like matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MSI) provide insight into metabolite composition within plant tissues, enabling researchers to correlate structural information with chemical signatures [10]. This approach has been used to spatially resolve metabolites like mescaline in cactus organs and flowers [10].

Advanced Microscopy Modalities: Techniques such as Superresolution Confocal Live Imaging Microscopy (SCLIM) combine high-speed imaging (up to 30 frames per second) with superresolution capabilities, allowing observation of dynamic cellular processes at resolutions unachievable with traditional confocal laser scanning microscopes [10]. This has revealed previously unobserved cellular structures like ER-Golgi connecting tubules [10].

FAQ: Implementation and Practical Considerations

What computational resources are typically required for multiscale image analysis? Multiscale imaging generates massive datasets that require substantial computational resources. Image-based modeling can easily exceed 100GB of RAM for processing, with storage requirements reaching terabytes for extended time-series experiments [7] [13]. High-performance computing clusters, efficient data compression algorithms, and specialized image processing workflows are essential for managing this data deluge.

How can researchers validate findings across different scales? Validation requires a systematic approach including:

- Internal consistency checks between modalities

- Physical sectioning and traditional histology correlated with non-destructive imaging

- Transgenic reporters to confirm functional inferences

- Iterative modeling and experimental refinement [13]

- Cross-scale predictive testing where models parameters from one scale predict phenomena at another [14]

What are the best practices for managing multimodal imaging experiments?

- Establish standardized protocols for each modality before beginning integrated experiments [8]

- Implement careful sample tracking and metadata management

- Use reference standards and controls in each imaging session

- Perform pilot studies to optimize imaging parameters and sequence

- Plan registration strategy before data collection, including fiducial markers if needed

- Allocate sufficient computational resources for data integration and analysis

By strategically matching imaging techniques to biological scales and addressing the technical challenges through systematic troubleshooting, plant phenomics researchers can effectively bridge the gap between genotype and phenotype across multiple levels of biological organization.

In modern plant phenomics, the ability to non-destructively quantify plant traits across different scales—from cellular processes to whole-plant morphology—is revolutionizing how we understand plant biology. This technical guide is framed within a broader thesis on optimizing multimodal imaging approaches, which integrate data from various sensors and technologies to provide a comprehensive view of plant physiology and development. For researchers navigating the practical challenges of these advanced methodologies, this document provides essential troubleshooting guidance and foundational protocols for three core phenotyping tasks: stress detection, growth monitoring, and organ analysis.

Troubleshooting Guide: Stress Detection

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why are my chlorophyll fluorescence measurements (Fv/Fm) inconsistent when detecting abiotic stress? Inconsistent Fv/Fm readings can stem from improper dark adaptation or fluctuating measurement conditions. Chlorophyll fluorescence relies on measuring the maximum quantum yield of PSII photochemistry, which requires a standardized protocol [15].

- Solution: Ensure plants are dark-adapted for at least 30 minutes prior to measurement to allow full relaxation of reaction centers. Perform measurements at a consistent time of day to minimize diurnal physiological variations. Validate your findings with biochemical assays, such as antioxidant enzyme activity tests, to confirm oxidative stress levels [15].

Q2: My molecular bioassays (e.g., for Ca²⁺ or ROS) are destructive and prevent time-series analysis. What are my alternatives? Destructive sampling is a common limitation of assays like chemiluminescence-based bioassays for Ca²⁺ and ROS [15].

- Solution: Adopt non-destructive fluorescence-based bioassays. For instance, use genetically engineered pathogens expressing fluorescent proteins (e.g., red fluorescence protein) to track host-pathogen interactions in real time. Alternatively, employ plant wearable sensors with functionalized coatings that can detect stress-related biomarkers in situ [15] [16].

Q3: How can I distinguish between co-occurring abiotic and biotic stresses in my phenotyping data? The complexity of plant stress responses makes this a common challenge, as different stressors can trigger overlapping visible symptoms [15].

- Solution: Implement an integrative multi-omics approach. Combine hyperspectral imaging for early symptom detection with molecular analysis. For example, use mass spectrometry-based metabolomics to identify unique pathogen metabolites and ionomics to reveal nutrient deficiencies that may predispose plants to biotic stress [15].

Experimental Protocol: Non-Visible Stress Response Profiling

This protocol outlines a methodology for characterizing early non-visible plant stress responses using molecular assays and omics technologies, suitable for laboratory settings [15] [17].

Objective: To detect and quantify early molecular and biochemical changes in plants exposed to abiotic or biotic stress.

Materials and Reagents:

- Plant material (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana, tomato, or wheat)

- Liquid Nitrogen for snap-freezing

- Luminescence or ELISA kits for Ca²⁺ or ROS detection (e.g., for heat shock proteins) [15]

- Luminometer or plate reader

- Equipment for Mass Spectrometry (e.g., GC-MS, LC-MS) [15]

- RNA extraction kits

- High-throughput sequencing platform

Procedure:

- Treatment and Sampling: Apply the stressor of interest (e.g., pathogen inoculation, drought, heat) to experimental plants. Collect leaf or root samples at multiple time points post-treatment (e.g., 0, 15 min, 1 h, 24 h). Immediately snap-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen to preserve molecular integrity.

- Molecular Bioassays: Homogenize a sub-set of frozen tissue. Use chemiluminescence-based assays to quantify bursts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) or intracellular Ca²⁺ flux. Alternatively, use Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISA) to detect and quantify specific stress-related hormones or heat shock proteins [15].

- Omics Profiling: Grind another sub-set of frozen tissue to a fine powder.

- For metabolomics, extract metabolites using a methanol/MTBE (methyl tertiary-butyl ether) protocol and analyze via GC-MS or LC-MS to identify stress-responsive metabolites [17].

- For proteomics, perform protein extraction, tryptic digestion, and analysis by LC-MS/MS to identify differentially abundant proteins and post-translational modifications [15] [17].

- Data Integration: Correlate the data from molecular bioassays with the proteomic and metabolomic profiles to build a comprehensive model of the early alarm and acclimation phases of the stress response [15].

Quantitative Data on Stress Detection Technologies

Table 1: Comparison of Key Plant Stress Detection Methods

| Technology | Measured Parameters | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorophyll Fluorescence Imaging [15] | Fv/Fm (PSII efficiency) | Leaf/Canopy level | Minutes to Hours | Detection of nutrient deficiency, heat, and drought stress. |

| Mass Spectrometry (Ionomics, Metabolomics) [15] | Elemental composition, metabolites | Destructive (tissue sample) | Single time point | Nutrient toxicity/deficiency, pathogen metabolite detection. |

| Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) Wearables [18] | Microclimate (T, RH), stem strain | Single plant/Stem level | Continuous (Real-time) | Monitoring of microclimate and growth changes induced by stress. |

| Hyperspectral Imaging [19] | Spectral reflectance across hundreds of bands | Canopy/Leaf level (UAV); Sub-mm (proximal) | Minutes to Days | Early disease detection, nutrient status, water stress. |

| Nanomaterials-based Sensors [16] | H₂O₂, specific ions | Cellular/Tissue level | Continuous (Real-time) | Real-time detection of wound-induced H₂O₂, in-field health monitoring. |

Visual Workflow: Multi-Scale Stress Detection

Multi-Scale Plant Stress Detection Workflow

Troubleshooting Guide: Growth Monitoring

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My automated image analysis for shoot phenotyping is struggling with accurate segmentation, especially under fluctuating light. What can I do? This is a common issue in high-throughput phenotyping. Traditional segmentation algorithms often fail with complex backgrounds and changing light conditions [20].

- Solution: Implement deep learning-based segmentation models. Use pre-trained convolutional neural networks (CNNs) like U-Net or fully automated approaches such as DeepShoot, which are more robust to environmental variations. For semi-automated generation of high-quality ground truth data, consider using k-means clustering of eigen-colors (kmSeg) or even Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to create synthetic training data [20].

Q2: How can I measure subtle plant growth (e.g., stem diameter) continuously without an imaging system? Imaging systems may lack the temporal resolution or sensitivity for continuous, fine-scale growth measurements [18].

- Solution: Deploy plant wearable sensors. For instance, Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) sensors encapsulated in a flexible, dumbbell-shaped matrix can be attached directly to the plant stem. These sensors measure strain (ε) induced by stem elongation or swelling with high sensitivity, providing real-time, continuous growth data [18].

Q3: My drone-based biomass estimates are inaccurate. How can I improve them? Biomass estimation from UAVs can be affected by sensor type, flight altitude, and model selection [19].

- Solution: Fuse data from multiple sensors. Combine multispectral and thermal infrared images captured by UAVs and process them with machine learning models (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) rather than simple vegetation indices. This multimodal approach significantly improves the accuracy of aerial biomass (AGB) and Leaf Area Index (LAI) estimations [19].

Experimental Protocol: FBG-Based Wearable Sensor for Growth Monitoring

This protocol details the use of Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) wearable sensors for continuous, simultaneous monitoring of plant growth and microclimate [18].

Objective: To fabricate and deploy FBG-based sensors for real-time, in-field monitoring of stem growth, temperature, and relative humidity.

Materials and Reagents:

- Commercial FBG sensors (acrylate recoating, e.g., λB ~1530-1550 nm)

- Dragon Skin 20 silicone (Smooth-On) or similar flexible matrix

- Chitosan (CH) powder (low molecular weight)

- Acetic acid (2% v/v aqueous solution)

- 3D printer and modeling software (e.g., Solidworks)

- FC/APC optical fiber connector

- FBG interrogator

Procedure:

- Sensor Fabrication:

- Growth Sensor: Design a dumbbell-shaped mold and 3D print it. Mix Dragon Skin 20 parts A and B, degas, and pour into the mold with an FBG sensor placed in the center. Cure for 4 hours at room temperature [18].

- RH Sensor: Functionalize a separate FBG by coating it with a chitosan gel (5% wt. in 2% acetic acid). Let it dry at room temperature for 12 hours. This coating swells/shrinks with changes in ambient humidity [18].

- T Sensor: Use a bare FBG, which is intrinsically sensitive to temperature [18].

- Sensor Multiplexing: Connect the three sensors in an array configuration on a single optical fiber and terminate with an FC/APC connector to enable interrogation [18].

- Field Deployment: Attach the flexible dumbbell-shaped sensor to the plant stem by wrapping its top and bottom parts around it. Secure the environmental sensors (RH and T) near the plant's canopy. Ensure the optical fiber is fixed to avoid noise from movement [18].

- Data Acquisition and Analysis: Connect the sensor array to an FBG interrogator. Continuously monitor the Bragg wavelength (λB) shifts for each sensor. Correlate ΔλB from the growth sensor with stem elongation, from the RH sensor with ambient humidity, and from the T sensor with temperature changes [18].

Research Reagent Solutions for Growth Monitoring

Table 2: Essential Materials for Advanced Growth Phenotyping Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Dragon Skin 20 Silicone [18] | Flexible encapsulation matrix for FBG wearable sensors. | High-stretchability, improves sensor robustness and adherence to irregular plant surfaces. |

| Chitosan (CH) Coating [18] | Functionalization layer for FBG-based humidity sensing. | Swells/shrinks in response to water vapor content, transducing RH changes into measurable strain. |

| Plasma Membrane Marker Lines(e.g., pUBQ10::myr-YFP) [21] | Fluorescent labeling for live confocal imaging of cellular structures. | Enables high-resolution tracking of cell boundaries and growth dynamics over time. |

| Murashige and Skoog (MS) Medium [21] | In vitro culture medium for maintaining dissected plant organs during live imaging. | Provides essential nutrients and vitamins for short-term sample viability. |

| Propidium Iodide (PI) [21] | Counterstain for plant cell walls in confocal microscopy. | Binds to cellulose and pectin, emitting red fluorescence when bound to DNA; outlines cell walls. |

Visual Workflow: Multimodal Growth Phenotyping

Multimodal Growth Phenotyping Data Pipeline

Troubleshooting Guide: Organ Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My confocal images of internal floral organs are blurry and lack resolution. How can I improve image quality? Image quality in plant tissues is often compromised by light scattering and the presence of pigments and fibers, which reduce resolution and contrast [21] [22].

- Solution: For internal organs like stamens and gynoecium, meticulous dissection is crucial. Use fine tools (tungsten probes, precision tweezers) to carefully remove enclosing sepals. Additionally, employ chemical clearing protocols (e.g., using ClearSee-based solutions) to reduce light scattering by making the tissue more transparent. Using a water-dipping lens with a good numerical aperture and long working distance can also dramatically improve image quality [21] [22].

Q2: How can I perform long-term live imaging of developing plant organs without causing damage? Live imaging is challenging due to sample dehydration, phototoxicity, and microbial contamination over time [21].

- Solution: Culture dissected organs on solid 1/2 MS medium supplemented with a Plant Preservative Mixture (PPM) to inhibit contamination. During imaging, maintain sample hydration and minimize laser intensity and exposure time to reduce photobleaching and stress. Acquire images at specific intervals over several days to capture developmental dynamics [21].

Q3: What is the best way to analyze 3D organ structure at a cellular level? Reconstructing 3D structures from 2D images is computationally intensive and requires high-quality input data [21] [22].

- Solution: Acquire z-stack image series using confocal microscopy. Then, use software capable of efficient 3D segmentation and rendering. For cleared tissues, combine specialized clearing protocols with light-sheet microscopy to rapidly capture high-resolution 3D images of entire organs, which can then be segmented and quantified [21] [22].

Experimental Protocol: Confocal Live Imaging of Internal Floral Organs

This protocol enables the visualization and quantitative analysis of the development of internal reproductive organs, such as stamens and gynoecium, in Arabidopsis thaliana at cellular resolution [21].

Objective: To prepare, dissect, and image the development of internal floral organs over consecutive days.

Materials and Reagents:

- Biological material: 4-week-old Arabidopsis thaliana expressing a plasma membrane marker (e.g., pUBQ10::myr-YFP).

- Murashige and Skoog (MS) basal salt mixture, Sucrose, Agar.

- Plant Preservative Mixture (PPM).

- Propidium Iodide (PI) staining solution (0.1%).

- Precision tools: Tungsten probe tips, Dumont No. 5 tweezers, scalpel blades.

- Equipment: Dissecting stereomicroscope, upright confocal microscope with water-dipping lenses (e.g., 40x/1.0), growth chamber.

Procedure:

- Plant Growth and Selection: Grow plants under long-day conditions (16h light/8h dark) for approximately 4 weeks. Select an inflorescence that has produced around 10 mature siliques, as it will have flower buds at the ideal developmental stage [21].

- Sample Dissection:

- Cut the inflorescence, leaving a 2-3 cm stem for handling.

- Under a stereomicroscope placed on a Kimwipe moistened with deionized water, use fine tweezers and a tungsten needle to carefully remove the larger siliques and older flowers.

- Identify a young, unopened flower bud. Using the needle, gently tear away the sepals and petals to expose the internal stamen and gynoecium. Avoid squeezing or damaging the organs [21].

- Sample Mounting and Staining:

- Transfer the dissected flower to a Petri dish containing solid 1/2 MS medium with 0.1% PPM.

- For better visualization of cell walls, the sample can be stained by applying a drop of 0.1% Propidium Iodide (PI) solution for a few minutes, then washing with medium or water [21].

- Confocal Imaging:

- Place the Petri dish under the confocal microscope. Use a water-dipping objective.

- Set up the laser lines to excite YFP (e.g., 514 nm) and PI (e.g., 561 nm) and configure appropriate emission filters.

- Acquire z-stack images of the exposed organs with a resolution sufficient to distinguish individual cells. The same sample can be returned to the growth chamber and re-imaged on subsequent days to track development [21].

- Image Analysis: Use image analysis software (e.g., Zeiss ZEN, ImageJ/Fiji) to perform 2D and 3D segmentation of the acquired z-stacks. This allows for the quantification of cellular parameters such as cell area, volume, and division patterns over time [21].

From Pixels to Predictions: Methodologies for Multimodal Data Fusion and Analysis

In the field of plant phenomics, the ability to non-destructively measure plant traits is revolutionizing our understanding of plant growth, development, and responses to environmental stresses [23]. High-throughput phenotyping platforms now employ a diverse array of imaging sensors—including visible light (RGB), thermal, hyperspectral, and fluorescence cameras—to capture complementary information about plant structure and function [9] [8]. However, effectively utilizing the cross-modal patterns identified by these different camera technologies presents a significant technical challenge: precise image registration [24].

Image registration is the process of aligning two or more images of the same scene taken from different viewpoints, at different times, or by different sensors [24]. In plant phenomics, this alignment is crucial for correlating data from multiple modalities, such as linking thermal patterns indicating water stress with specific leaf regions in RGB images, or associating chlorophyll fluorescence signals with corresponding plant organs [9]. While traditional 2D registration methods based on homography estimation have been used, they frequently fail to address the fundamental challenges of parallax effects and occlusions inherent in imaging complex plant canopies [24]. This technical support article addresses these challenges within the context of optimizing multimodal imaging for plant phenomics research, providing troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols for researchers working with diverse camera setups.

Technical FAQs: Addressing Common Research Challenges

Q1: Why do traditional 2D image registration methods (e.g., based on homography) often fail for close-range plant phenotyping applications?

Traditional 2D methods assume that a simple transformation (affine or perspective) can align entire images [24]. However, in close-range plant imaging, parallax effects—where the relative position of objects appears to shift when viewed from different angles—are significant due to the complex three-dimensional structure of plant canopies [24]. Additionally, these methods cannot adequately handle occlusions, where plant organs hide each other from different camera viewpoints [24]. Consequently, 2D transformations result in registration errors that prevent pixel-accurate correlation of features across different imaging modalities.

Q2: What are the advantages of using 3D information for multimodal image registration in plant phenotyping?

Integrating 3D information, particularly from depth cameras, enables a fundamentally more robust approach to registration [24]. By reconstructing the 3D geometry of the plant canopy, the system can precisely calculate how each pixel from any camera maps onto the 3D surface, effectively mitigating parallax errors [24]. This method is also independent of the camera technology used (RGB, thermal, hyperspectral) and does not rely on finding matching visual features between fundamentally different image modalities, which is often difficult or impossible [24].

Q3: How can researchers identify and manage occlusion-related errors in multimodal registration?

A proactive approach involves classifying and automatically detecting different types of occlusions. The registration process can be designed to identify regions where:

- Background Occlusion: The ray from a camera hits the background instead of the plant.

- Self-Occlusion: A plant part blocks the view of another part from a specific camera angle.

- Inter-Camera Occlusion: An element in the setup (not the plant) blocks the view [24]. The algorithm can then generate occlusion masks that clearly label these regions in the output, preventing the introduction of erroneous data correlations where reliable matching is impossible [24].

Q4: What are the primary imaging modalities used in plant phenomics, and what phenotypic traits do they measure?

Table: Common Imaging Modalities in Plant Phenomics and Their Applications

| Imaging Technique | Measured Parameters | Example Phenotypic Traits | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible Light (RGB) | Color, texture, shape, size | Projected shoot area, biomass, architecture, germination rate, yield components | [8] [25] |

| Thermal Imaging | Canopy/leaf surface temperature | Stomatal conductance, plant water status, transpiration rate | [8] [25] |

| Fluorescence Imaging | Chlorophyll fluorescence emission | Photosynthetic efficiency, quantum yield, abiotic/biotic stress responses | [8] |

| Hyperspectral Imaging | Reflectance across numerous narrow bands | Pigment composition, water content, tissue structure, nutrient status | [8] [9] |

| 3D Imaging (e.g., ToF, LiDAR) | Depth, point clouds, surface models | Plant height, leaf angle distribution, root architecture, biomass | [8] [24] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Alignment Accuracy in Complex Canopies

Problem: Registration algorithms produce misaligned images, particularly in dense, complex plant canopies, leading to incorrect correlation of data from different sensors.

Solutions:

- Implement a 3D Registration Pipeline: Move beyond 2D homography. Utilize a depth camera to generate a 3D mesh of the plant canopy. Employ ray casting techniques from each camera's perspective onto this shared 3D model to achieve pixel-accurate mapping between modalities [24].

- Systematic Camera Calibration: Calibrate all cameras in the setup extensively using a checkerboard pattern captured from multiple distances and orientations. This ensures accurate internal (focal length, lens distortion) and external (position, rotation) camera parameters, which are foundational for 3D registration [24].

- Occlusion Masking: Implement an automated mechanism to identify and classify occluded regions in the images. Filter out or clearly label these pixels to prevent them from introducing errors in downstream analysis [24].

Handling Diverse Camera Resolutions and Spectral Characteristics

Problem: The multimodal setup uses cameras with different native resolutions and captures fundamentally different physical properties (e.g., color vs. temperature), making feature-based matching unreliable.

Solutions:

- Leverage a Universal Registration Cue: Use 3D geometry as the common denominator for registration. Since the method relies on the 3D mesh and ray casting, it is inherently independent of the camera's resolution and the specific wavelength it captures [24].

- Resampling and Projection: The registration algorithm can be designed to project and resample data from all cameras onto the same 3D coordinate system, creating a unified dataset despite the initial differences in resolution [24].

- Validation with Fiducial Markers: In initial setup validation, use neutral fiducial markers that are detectable across multiple modalities (e.g., a material with distinct visual and thermal properties) to visually confirm registration accuracy before plant experiments [24].

Experimental Protocol: 3D Multimodal Image Registration

This protocol details a method for achieving precise registration of images from arbitrary camera setups, leveraging 3D information to overcome parallax and occlusion [24].

The diagram below illustrates the sequential steps from image acquisition to the final registered multimodal outputs.

Materials and Equipment

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Multimodal Imaging

| Item | Specification / Function | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Multimodal Camera Setup | Must include at least one depth camera (e.g., Time-of-Flight). Can be supplemented with RGB, thermal, hyperspectral cameras. | The depth camera provides the essential 3D geometry for the registration pipeline [24]. |

| Calibration Target | Checkerboard pattern with known dimensions. | Ensure the pattern has high contrast and is physically rigid. Used for calculating camera parameters [24]. |

| Computing Workstation | High-performance CPU/GPU, sufficient RAM. | Necessary for processing 3D point clouds, mesh generation, and ray casting computations [24]. |

| Software Libraries | OpenCV, PlantCV, or custom 3D registration algorithms. | Libraries provide functions for camera calibration, 3D reconstruction, and image processing [26] [20]. |

| Occlusion Masking Algorithm | Custom logic to classify and filter occlusion types. | Critical for identifying and handling regions where pixel matching is invalid [24]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

System Calibration:

- Capture multiple images of the checkerboard pattern with every camera in the setup. Ensure images cover the entire field of view and are taken from various distances and angles [24].

- Use a calibration algorithm (e.g., in OpenCV) to compute the intrinsic parameters (focal length, optical center, lens distortion) for each camera and the extrinsic parameters (rotation and translation) defining the position of every camera relative to a common world coordinate system [24].

3D Scene Reconstruction:

- With the calibrated system, capture a scene containing the plant of interest. The depth camera will provide a depth map or point cloud.

- Process this depth data to generate a 3D mesh representation of the plant canopy. This mesh serves as the common geometric model for registration [24].

Ray Casting and Pixel Mapping:

- For each pixel in every other camera (e.g., the thermal camera), cast a ray from that camera's center of projection through the pixel's location into the 3D scene.

- Calculate where this ray intersects the 3D mesh. The 3D coordinate of this intersection point defines the physical location that the pixel is observing.

- Project this 3D point back into the depth camera's view and all other camera views to find the corresponding pixels. This process establishes a precise, geometry-based mapping between all image modalities [24].

Occlusion Handling and Output Generation:

- During the ray-casting step, automatically detect and classify occlusion cases. If a ray from a camera does not hit the mesh, or hits a part of the mesh that is not the primary subject, label it as an occlusion [24].

- Generate the final outputs: pixel-aligned images for each modality, a unified 3D point cloud where each point contains data from all sensors, and corresponding occlusion masks that indicate untrustworthy regions [24].

Advanced image registration is no longer a peripheral technical concern but a core requirement for unlocking the full potential of multimodal plant phenomics. By adopting 3D registration methodologies that directly address the challenges of parallax and occlusion, researchers can achieve the pixel-accurate alignment necessary for robust, high-throughput phenotypic analysis. The protocols and troubleshooting guides provided here establish a foundation for implementing these advanced techniques, enabling more precise correlation of phenotypic traits and accelerating the journey from genomic data to meaningful biological insight.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My deep learning model for plant disease classification performs well on the training dataset (like PlantVillage) but fails in real-world field conditions. What are the primary causes and solutions?

A1: This is a common challenge often stemming from the dataset domain gap. Models trained on controlled, clean images (e.g., isolated leaves on a uniform background) struggle with the complex backgrounds, varying lighting, and multiple plant organs found in field images [27].

- Cause: The model has learned features specific to the training dataset's environment rather than generalizable features for the disease itself [27].

- Solutions:

- Data Augmentation: Apply random transformations (rotation, scaling, color jitter, noise addition) to your training images to simulate field conditions [28].

- Use More Diverse Datasets: Incorporate training data that includes complex backgrounds, multiple leaves, and various growth stages. Seek out challenge-oriented datasets designed for real-world performance [27].

- Transfer Learning: Fine-tune a pre-trained model (e.g., on ImageNet) using your specific plant dataset. This leverages general feature detectors and can improve generalization with less data [28].

Q2: Annotating pixel-level data for plant disease segmentation is extremely time-consuming. Are there effective alternatives?

A2: Yes, Weakly Supervised Learning (WSL) is a promising approach to reduce annotation workload.

- Solution: Utilize image-level annotations (simply labeling an image as "healthy" or "diseased") to train models that can perform pixel-level segmentation.

- Experimental Protocol: A referenced study explored this using Grad-CAM combined with a ResNet-50 classifier (ResNet-CAM) and a Few-shot pretrained U-Net classifier for Weakly Supervised Leaf Spot Segmentation (WSLSS) [29].

- Procedure:

- Train a classification model using only image-level labels.

- Use techniques like Grad-CAM to generate heatmaps highlighting the regions the model used for its classification decision.

- These heatmaps serve as proxy segmentation masks. The WSLSS model in the study achieved an Intersection over Union (IoU) of 0.434 on an apple leaf dataset and demonstrated stronger generalization (IoU of 0.511) on unseen disease types compared to fully supervised models [29].

- Procedure:

Q3: For multimodal plant phenomics (e.g., combining RGB, thermal, and hyperspectral images), what is the best way to fuse these different data types in a model?

A3: Effectively fusing multimodal data is an active research area. The optimal architecture depends on your specific objective [27].

- Considerations:

- Early Fusion: Combine raw data from different sensors (e.g., stacking RGB and hyperspectral channels) before feeding them into a single model. This requires data alignment and normalization.

- Late Fusion: Train separate feature extraction models for each modality (e.g., a CNN for RGB, another for thermal) and fuse the extracted high-level features before the final classification or regression layer.

- Intermediate Fusion: Fuse features at intermediate layers within the network, allowing the model to learn correlations between modalities at different levels of abstraction. This is often the most flexible and powerful approach.

- Recommendation: Start with a late fusion approach for its simplicity and modularity. If performance is insufficient, explore more complex intermediate fusion architectures like cross-attention transformers, which are well-suited for modeling relationships between different data streams.

Q4: Training large transformer models on high-resolution plant images is computationally prohibitive. How can I reduce memory usage and training time?

A4: Optimizing memory and compute for large models is critical.

- Techniques:

- Mixed Precision Training: Use 16-bit floating-point numbers (FP16) for most operations while keeping a 32-bit (FP32) master copy of weights. This reduces memory usage and can speed up training on supported GPUs.

- Gradient Accumulation: Simulate a larger batch size by accumulating gradients over several forward/backward passes before updating model weights. This reduces memory pressure.

- Model Parallelism: For extremely large models, split the model across multiple GPUs. Sequence Parallelism and Selective Activation Recomputation are advanced techniques that can almost eliminate the need for costly activation recomputation, reducing activation memory by up to 5x and execution time overhead by over 90% [30].

- Practical First Step: Implement mixed precision training and gradient accumulation, as these are often supported out-of-the-box in deep learning frameworks.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Generalization to Field Environments

Symptoms: High accuracy on validation split of lab dataset, but poor performance on images from greenhouses or fields.

Diagnosis and Resolution Workflow:

Issue: High Cost of Data Annotation for Segmentation

Symptoms: Need precise lesion localization but lack resources for extensive pixel-wise annotation.

Diagnosis and Resolution Workflow:

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Weakly Supervised Segmentation for Leaf Disease

Objective: To train a model for segmenting disease spots on leaves using only image-level "diseased" or "healthy" labels [29].

Dataset Preparation:

- Collect images of plant leaves.

- Annotate each image at the image level (e.g., 0 for healthy, 1 for diseased). Pixel-level masks are not needed.

Model Training - Classification Phase:

- Select a backbone CNN (e.g., ResNet-50) for image classification.

- Train the classifier on your image-level labeled dataset until convergence.

Localization Map Generation:

- Use the trained classifier and a technique like Grad-CAM.

- For a given input image, Grad-CAM produces a heatmap highlighting the regions most important for the prediction of the "diseased" class.

Segmentation Model Training (WSLSS):

- Use the generated Grad-CAM heatmaps as proxy ground-truth masks for a segmentation model like U-Net.

- Train the segmentation model to learn the mapping from the original image to the proxy mask. This model can then be used to segment new images.

Protocol 2: Optimizing Large Model Training with Activation Management

Objective: To reduce GPU memory consumption during the training of large transformer models, enabling the use of larger models or batch sizes [30].

Baseline Setup:

- Establish your baseline model (e.g., a Vision Transformer) and note the maximum batch size that fits in GPU memory.

Enable Mixed Precision:

- In your training framework (e.g., PyTorch), enable AMP (Automatic Mixed Precision). This often requires only a few lines of code.

Implement Gradient Accumulation:

- Set the

accumulation_stepsparameter. The effective batch size becomesphysical_batch_size * accumulation_steps. - Adjust your training loop to only step the optimizer and zero gradients after every

accumulation_stepsiterations.

- Set the

Advanced: Selective Activation Recomputation:

- For models at the scale of hundreds of billions of parameters, implement selective activation recomputation.

- This involves identifying specific layers (e.g., attention projections) whose outputs are cheap to recompute but save significant memory when not stored.

- This technique, combined with sequence and tensor parallelism, can reduce activation memory by 5x and cut the execution time overhead of recomputation by over 90% [30].

Performance Comparison of Plant Disease Detection Models

Table 1: A comparison of different deep learning approaches for plant disease analysis, showcasing their performance on various tasks.

| Model Type | Task | Key Metric | Reported Performance | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised DeepLab | Semantic Segmentation (Apple Leaves) | IoU | 0.829 | Requires pixel-level annotations | [29] |

| Weakly Supervised (WSLSS) | Semantic Segmentation (Apple Leaves) | IoU | 0.434 | Trained with image-level labels only | [29] |

| Weakly Supervised (WSLSS) | Semantic Segmentation (Grape/Strawberry) | IoU | 0.511 | Demonstrated better generalization | [29] |

| State-of-the-Art DL Models | Disease Classification | Accuracy | Often > 95% | On controlled datasets like PlantVillage | [31] |

| State-of-the-Art DL Models | Disease Detection & Segmentation | Precision | > 90% | For identifying and localizing diseases | [31] |

Imaging Techniques for Plant Phenotyping

Table 2: Overview of various imaging modalities used in high-throughput plant phenomics and their primary applications.

| Imaging Technique | Sensor Type | Phenotype Parameters Measured | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visible Light (RGB) Imaging | RGB Cameras | Projected area, growth dynamics, shoot biomass, color, morphology, root architecture | Measuring leaf area and detecting disease lesions [8] |

| Fluorescence Imaging | Fluorescence Cameras | Photosynthetic status, quantum yield, leaf health status | Detecting biotic stress and photosynthetic efficiency [8] |

| Thermal Infrared Imaging | Thermal Cameras | Canopy or leaf temperature, stomatal conductance | Monitoring plant water status and drought stress [8] [32] |

| Hyperspectral Imaging | Spectrometers, Hyperspectral Cameras | Leaf & canopy water status, pigment composition, health status | Quantifying vegetation indices and early stress detection [8] |

| 3D Imaging | Stereo Cameras, ToF Cameras | Shoot structure, leaf angle, canopy structure, root architecture | Analyzing plant architecture and biomass estimation [8] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential components for building a deep learning-based plant phenotyping system.

| Item / Solution | Function / Description | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Phenotyping Platform | Hardware system for consistent data acquisition. Ranges from stationary setups to UAVs. | "LemnaTec Scanalyzer" for automated imaging in controlled environments; UAVs for field phenotyping [32]. |

| Multispectral/Hyperspectral Sensors | Capture data beyond visible light, providing insights into plant physiology. | Used to calculate vegetation indices like NDVI for assessing plant health and water content [8]. |

| Public Datasets | Pre-collected, annotated images for training and benchmarking models. | PlantVillage: A large, public dataset of preprocessed leaf images for disease classification [28]. |

| Pre-trained Models (Foundation Models) | Models trained on large-scale datasets (e.g., ImageNet), serving as a starting point. | Using a pre-trained ResNet-50 or Vision Transformer for transfer learning on a specific plant disease task [33] [28]. |

| Weak Supervision Frameworks | Software tools that enable learning from weaker, cheaper forms of annotation. | Using Grad-CAM libraries in PyTorch/TensorFlow to generate localization maps from image-level labels [29]. |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Workflow Design

Q1: What are "latent traits," and why are they important for plant stress phenotyping? Latent traits are complex, non-intuitive patterns in plant image data that are not defined by human researchers but are discovered directly by machine learning (ML) algorithms. Unlike traditional traits like root length, latent traits capture intricate spatial arrangements and relationships [34]. They are crucial because they can reveal subtle physiological responses to stresses like drought, which are often missed by conventional geometric measurements. For instance, an algorithm discovered that the specific density and 3D positioning of root clusters are a key latent trait for drought tolerance in wheat, leading to classification models with over 96% accuracy [34].

Q2: My model performs well on lab data but fails in field conditions. What could be wrong? This is a common problem known as the domain shift. It often stems from differences in lighting, background complexity, and plant occlusion between controlled lab and field environments [35] [36].

- Solution: Employ data augmentation techniques that simulate field conditions, such as adding random shadows, background noise, and motion blur to your lab images. Furthermore, consider using domain adaptation techniques or fine-tuning your model on a small, annotated dataset from the target field environment to bridge this gap [32].

Q3: How do I choose between traditional computer vision and deep learning for trait extraction? The choice depends on your data volume, computational resources, and the complexity of the traits.

- Traditional ML (e.g., Random Forest, SVM) requires you to manually define and extract features (e.g., color histograms, texture). It is effective with smaller datasets and when the relevant features are well-understood and easily quantifiable [32].

- Deep Learning (e.g., CNN, YOLO) automatically learns hierarchical features directly from raw images. It is superior for discovering latent traits and complex patterns but requires large amounts of labeled data and greater computational power [35] [37]. For novel traits beyond human perception, deep learning is often the necessary choice.

Q4: What are the best practices for fusing data from multiple imaging sensors (e.g., RGB, NIR, thermal)? Multimodal fusion is key to a comprehensive phenotypic profile. The best practice involves:

- Temporal and Spatial Registration: Ensure images from different sensors are precisely aligned in time and space.

- Feature-Level Fusion: Extract features from each modality separately (e.g., architectural traits from RGB, physiological traits from NIR) and then concatenate them into a unified feature vector for model training [38].

- Model-Based Fusion: Use machine learning models capable of handling multiple inputs. For example, you can train separate branches of a neural network for each sensor type and merge them in a later layer [39]. Studies have shown that combining traits from RGB and NIR sensors can predict biomass with about 90% accuracy, outperforming single-modality models [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Accuracy in Object Detection and Segmentation

Symptoms: Poor performance in identifying plant parts (leaves, stems, roots) from images; low recall and precision metrics.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Training Data | Check the size and variety of your annotated dataset. | Use data augmentation (rotation, flipping, color jittering). Employ transfer learning by using a pre-trained model (e.g., VGG16, YOLO) on a large dataset like ImageNet and fine-tune it on your plant images [35] [37]. |

| Class Imbalance | Analyze the distribution of labels. Some plant parts may be underrepresented. | Use the focal loss function during training, which focuses learning on hard-to-classify examples. Oversample the rare classes or generate synthetic data [35]. |

| Suboptimal Model Architecture | Evaluate if the model is suitable for the task (e.g., using an outdated model). | Adopt a modern architecture. For example, an improved YOLOv11 model, which integrated an adaptive kernel convolution (AKConv), increased recall by 4.1% and mAP by 2.7% for detecting tomato plant structures [35]. |

Problem: Model Fails to Generalize Across Plant Genotypes or Growth Stages

Symptoms: High accuracy on the genotypes/stages used in training but significant drop on new ones.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Bias in Training Data | Audit your training set to ensure it encompasses the genetic and morphological diversity of your target population. | Intentionally curate a training dataset that includes a wide range of genotypes and growth stages. Techniques like unsupervised clustering can help verify the diversity of your data before training [34]. |

| Overfitting to Spurious Features | The model may be learning background features or genotype-specific patterns not related to the target trait. | Use visualization techniques like Grad-CAM to see what image regions the model is using for predictions. Incorporate domain randomization during training and apply strong regularization techniques [36]. |

Problem: Inconsistent Trait Extraction from 3D Plant Models

Symptoms: High variance in measurements like biomass or leaf angle from 3D reconstructions.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Quality 3D Point Clouds | Inspect the 3D reconstructions for noise, holes, or misalignment. | Optimize the image acquisition setup. For stereo vision, ensure proper calibration and lighting. Consider using more robust 3D imaging like LiDAR or structured light if the environment permits [26] [36]. |

| Ineffective Feature Descriptors | The algorithms used to quantify 3D shapes may be too simplistic. | Move beyond basic geometric traits. Use algorithmic approaches that leverage unsupervised ML to discover latent 3D shape descriptors that are more robust to noise and capture biologically relevant spatial patterns [34] [36]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Cited Studies

Protocol 1: Extracting Algorithmic Root Traits (ART) for Drought Tolerance

This protocol is based on the study that achieved 96.3% accuracy in classifying drought-tolerant wheat [34].

1. Image Acquisition:

- Equipment: Use high-resolution digital cameras for root system imaging. Systems like RhizoTube or other root phenotyping platforms are suitable [32].

- Standardization: Ensure consistent lighting and background across all images.

2. Physiological Drought Tolerance Assessment:

- Rank plant genotypes using multiple drought-response metrics (e.g., stomatal conductance, relative water content, tiller number) under controlled stress conditions.

- Perform statistical tests (e.g., ANOVA) to confirm significant differences between groups.

- Use unsupervised clustering (e.g., k-means) on the physiological data to objectively group genotypes into "tolerant" and "susceptible" classes.

3. Algorithmic Trait Extraction with ART Framework:

- Software: Implement the multi-stage ART pipeline.

- Process: Apply an ensemble of eight unsupervised machine learning algorithms plus one custom algorithm to each root image.

- Output: The framework will identify the densest root clusters and quantify their size and spatial position, generating 27 distinct Algorithmic Root Traits (ARTs).

4. Model Training and Validation:

- Use the physiological classes from Step 2 as your ground truth labels.

- Train supervised classification models (e.g., Random Forest, CatBoost) using the 27 ARTs as features.

- Validate model performance on a held-out independent dataset to ensure robustness.

Protocol 2: Deep Learning-Based Phenotypic Trait Extraction in Tomato

This protocol outlines the methodology for using an improved YOLO model to extract traits from tomato plants under water stress [35].

1. Experimental and Image Setup:

- Plant Growth: Grow tomato plants (e.g., Solanum lycopersicum L. cv. 'Honghongdou') under a range of controlled water stress conditions in a greenhouse.

- Imaging Platform: Set up a fixed imaging station with consistent artificial lighting to avoid shadows and glare. Capture RGB images of plants at regular intervals.

2. Model Improvement and Training:

- Base Model: Start with the YOLOv11n architecture.

- Enhancements: Integrate Adaptive Kernel Convolution (AKConv) into the backbone's C3 module and design a recalibrated feature pyramid detection head to improve detection of small plant parts.

- Training: Train the model on annotated tomato images. Bounding boxes should label key structures like leaves, petioles, and the main stem.

3. Phenotypic Parameter Computation:

- Plant Height & Counts: Use the bounding box information generated by the trained model. Plant height can be calculated as the height of the main stem's bounding box. Petiole and leaf counts are derived from the number of corresponding detected objects.

- Validation: Manually measure a subset of plants to calculate the relative error of the automated system (e.g., target ~6.9% for plant height, ~10% for petiole count).

4. Stress Classification:

- Construct input features from the extracted traits (e.g., plant height, petiole count, leaf area).

- Train multiple classification algorithms (e.g., Logistic Regression, SVM, Random Forest) to differentiate water stress levels.

- Select the best-performing model (e.g., Random Forest, which achieved 98% accuracy in the cited study).

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: Multimodal Phenotyping ML Workflow

This diagram illustrates the complete pipeline from image acquisition to biological insight, integrating multiple sensors and machine learning approaches.

Diagram 2: Algorithmic Root Trait (ART) Analysis

This workflow details the specific process for discovering hidden root traits associated with drought resilience.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Components for a Multimodal Plant Phenotyping Pipeline

| Item Category | Specific Examples & Specifications | Primary Function in Trait Extraction |

|---|---|---|

| Imaging Sensors | RGB Camera (CCD/CMOS sensor), Near-Infrared (NIR) Camera, Thermal Imaging Camera, Hyperspectral Imager [26] [40]. | Captures different aspects of plant physiology and morphology. RGB for structural data, NIR for biomass/water content, thermal for stomatal activity, and hyperspectral for biochemical composition. |

| Phenotyping Platforms | LemnaTec Scanalyzer systems, Conveyor-based platforms, Stationary imaging cabins, UAVs (drones) equipped with multispectral sensors [32] [40]. | Provides high-throughput, automated, and consistent image acquisition of plants under controlled or field conditions. |

| ML Software & Libraries | Python with OpenCV, Scikit-image, PlantCV; Deep Learning frameworks (TensorFlow, PyTorch); Pre-trained models (VGG16, YOLO variants) [35] [26] [37]. | Provides the algorithmic backbone for image preprocessing, segmentation, feature extraction, and model training for latent trait discovery. |

| Unsupervised ML Algorithms | Ensemble methods (as used in the ART framework), clustering algorithms (k-means), dimensionality reduction (PCA) [34]. | Used to discover latent traits directly from image data without human bias, identifying complex spatial patterns linked to stress tolerance. |

| Data Augmentation Tools | Built-in functions in TensorFlow/PyTorch (e.g., RandomFlip, RandomRotation, ColorJitter). | Artificially expands the size and diversity of training datasets by creating modified versions of images, improving model robustness and generalizability. |

| 3D Reconstruction Software | Structure-from-Motion (SfM) software, LiDAR point cloud processing tools [26] [36]. | Generates 3D models of plants from 2D images or laser scans, enabling the extraction of volumetric and architectural traits like canopy structure and root system architecture. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Issues in Multimodal Data Fusion

Problem: Low Contrast in Certain Image Modalities Hinders Automated Segmentation

- Issue: Visible light (VIS) or near-infrared (NIR) images often exhibit low contrast between plant and background regions, complicating automated segmentation, a major bottleneck in phenotyping pipelines [41].

- Solution: Register low-contrast images with a high-contrast modality (e.g., fluorescence - FLU). The binary mask from the segmented FLU image can then be applied to extract plant regions from the VIS image [41].

- Protocol: Use an iterative algorithmic scheme for rigid or slightly nonrigid registration. Preprocessing steps should include resampling images to the same spatial resolution and may involve downscaling to suppress modality-specific high-frequency noise, which enhances overall image similarity [41].

Problem: Failure of Image Registration Algorithms Due to Structural Dissimilarities

- Issue: Conventional registration methods (feature-point, frequency domain, intensity-based) can fail when aligning images from different modalities due to significant structural differences, nonuniform motion, or blurring [41].

- Solution: Employ an extended registration approach that includes structural enhancement and characteristic scale selection. Evaluate the success rate (SR) of alignment by comparing the number of successful registrations to the total number of image pairs processed [41].

- Protocol:

- Preprocessing: Convert RGB images to grayscale or calculate edge-magnitude images. Resample all images to a uniform spatial resolution.

- Method Selection: Test multiple registration routines. Feature-point matching can be enhanced by using an integrative multi-feature generator that merges results from different detectors (e.g., edges, corners, blobs).

- Validation: For frequency-domain methods like phase correlation (PC), a reliability threshold (e.g., maximum PC peak height H > 0.03) should be used; results below this threshold indicate failure [41].

Problem: Scarce Data for Training Models in Specific Scenarios

- Issue: Accurate identification of crop diseases is often hampered by a lack of sufficient training image data, especially for rare diseases or complex field conditions [42].

- Solution: Implement a Multimodal Few-Shot Learning (MMFSL) model that incorporates both image and textual information. This approach leverages a pre-trained language model to guide the image-based few-shot learning branch, bridging the gap caused by image scarcity [42].

- Protocol:

- Image Branch: Use a Vision Transformer (ViT) to segment input samples into small patches, establishing semantic correspondences between local image regions.

- Text Branch: Use a pre-trained language model. Create a hand-crafted cue template that incorporates class labels as input text.

- Fusion: Employ a bilinear metric function in an image-text comparison module to align semantic images and text, updating network parameters with a model-agnostic meta-learning (MAML) framework [42].

Performance of Multimodal Image Registration Techniques

The following table summarizes the performance of three common registration techniques when applied to multimodal plant images, such as aligning visible light (VIS) and fluorescence (FLU) data.

| Method Category | Core Principle | Key Challenges in Plant Imaging | Recommended Extension |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature-Point Matching [41] | Detects and matches corresponding local features (edges, corners, blobs) between images. | Difficulty finding a sufficient number of corresponding points in similar but nonidentical images of different modalities [41]. | Use an integrative multi-feature generator that merges results from different feature-point detectors [41]. |

| Frequency Domain (e.g., Phase Correlation) [41] | Uses Fourier-shift theorem to find image correspondence via phase-shift of Fourier transforms. | Less accurate with multiple structurally similar patterns or considerable structural dissimilarities [41]. | Apply image downscaling to a proper characteristic size to suppress high-frequency noise and enhance similarity [41]. |

| Intensity-Based (e.g., Mutual Information) [41] | Maximizes a global similarity measure (e.g., Mutual Information) between image intensity functions. | Performance can be degraded by nonuniform image motion and blurring common in plant imaging [41]. | The method is inherently suitable for images with different intensity levels, but requires robust optimization for complex transformations [41]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary advantages of a multimodal fusion approach over single-mode analysis in plant phenomics?