Optimizing Energy Efficiency for Remote Field Sensors: Power Management, Deployment Strategies, and Data Integrity for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on maximizing the performance and longevity of remote field sensors.

Optimizing Energy Efficiency for Remote Field Sensors: Power Management, Deployment Strategies, and Data Integrity for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on maximizing the performance and longevity of remote field sensors. It covers foundational principles of energy-efficient technologies, advanced deployment methodologies using AI and optimized protocols, practical troubleshooting for field operations, and rigorous validation techniques to ensure data reliability. By integrating strategies from power source selection to data transmission optimization, this resource supports the deployment of robust, long-lasting sensor networks crucial for reliable data collection in biomedical and clinical field research.

Core Principles and Energy Technologies for Sustainable Field Sensors

The Critical Role of Sensor Networks in Biomedical Field Research

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Common Sensor Network Issues and Solutions

| Problem Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Energy Efficiency Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid Power Drain | High data transmission frequency; Suboptimal network routing; Inefficient duty cycling. | Reduce non-essential data transmission; Implement adaptive sampling based on activity detection; Optimize sensor sleep/wake schedules [1]. | High impact: Can extend battery life by up to 60% with optimized duty cycles [2]. |

| Erratic or Missing Data | Weak or unreliable network connection; Signal interference; Sensor node failure. | Check node positioning and network topology; Verify firmware is up-to-date for bug fixes and performance improvements [1]. | Medium impact: Prevents wasted energy on failed transmissions and data re-transmission. |

| Inaccurate Physiological Readings | Sensor displacement or poor skin contact; Low battery; Improper calibration. | Verify sensor placement; Check battery levels; Recalibrate according to manufacturer protocol. | Low impact: Ensures data quality, preventing energy waste on collecting useless data. |

| Security and Privacy Alerts | Unauthorized access attempts; Lack of data encryption; Vulnerable communication protocols. | Ensure all devices use strong, unique passwords; Activate data encryption features; Regularly update device firmware to patch security flaws [3]. | Variable: Encryption consumes more energy but is essential for data integrity and privacy [3] [4]. |

Detailed Protocol: Optimizing Sensor Duty Cycling for Energy Efficiency

Objective: To extend the operational lifetime of remote field sensors by intelligently managing their active and sleep states.

Materials:

- Sensor nodes with programmable duty cycles.

- Network gateway or base station.

- Energy monitoring software.

- (Optional) External activity trigger (e.g., accelerometer).

Methodology:

- Baseline Measurement: Operate all sensors at a continuous (100%) duty cycle for 24 hours. Record total energy consumption and data quality.

- Define Sampling Strategy: Program sensors to adopt an adaptive schedule [1] [2]. For example:

- Active Period: 200ms of sensing and data transmission.

- Sleep Period: 800ms of low-power mode.

- This creates a 20% duty cycle.

- Implement Adaptive Sensing: Where possible, use a secondary sensor (e.g., motion) to trigger the primary sensor (e.g., ECG) only upon detecting relevant activity, further reducing idle power consumption [2].

- Validation: Run the system with the new duty cycle for 24 hours. Compare energy consumption and critical data capture against the baseline to ensure no vital information is lost.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I improve the battery life of my wearable sensors without compromising data integrity? A: Focus on three key areas:

- Data Transmission: Transmit only essential, processed data (e.g., heart rate anomalies) instead of raw data streams [2].

- Duty Cycling: Implement aggressive but intelligent sleep schedules where sensors wake only at predefined intervals [1].

- Network Efficiency: Ensure a strong network infrastructure to prevent nodes from wasting energy on repeated transmission attempts [1].

Q2: What are the critical security considerations for transmitting sensitive patient data from the field? A: Security is paramount in biomedical research [3] [4]. Key steps include:

- Encryption: All data, both at rest and in transit, must be encrypted.

- Authentication: Use secure authentication methods to prevent unauthorized access to the network.

- Firmware Updates: Regularly update device firmware to patch known security vulnerabilities [1].

- Data Minimization: Transmit the minimum necessary data to reduce the risk exposure [4].

Q3: We are experiencing network congestion and data packet loss in our dense sensor network. How can this be resolved? A: Network congestion often arises from incompatible devices or poor network design [1].

- Compatibility: Ensure all devices and protocols are compatible and can "talk" to each other efficiently [1].

- Network Structure: Invest in a robust network infrastructure with sufficient bandwidth and consider a mesh topology where nodes can relay data for one another, improving coverage and reliability [1].

Q4: What should I do if sensor data seems physiologically implausible? A: Follow this diagnostic workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Biomedical Sensor Network Experiments

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Energy-Efficient Sensor Nodes | The core units for data acquisition. Often include accelerometers, gyroscopes, and physiological sensors [4]. | Wearable ECG patches for long-term cardiac monitoring in free-living subjects [3] [4]. |

| Wireless Body Area Network (WBAN) Protocol | A communication standard for short-range, low-power communication in and around the human body [3]. | Creating a personal network of sensors (ECG, oximeter, temperature) that efficiently relays data to a hub (e.g., smartphone) [3]. |

| Network Gateway | Aggregates data from multiple sensor nodes and transmits it to a central server or cloud platform. | A smartphone or dedicated base station that collects data from a research participant's sensors and transmits it via cellular network to the research lab [3]. |

| Data Encryption Software | Protects the confidentiality and integrity of sensitive physiological data during transmission and storage [3] [4]. | Ensuring HIPAA/GDPR compliance in clinical trials using remote monitoring. |

| Power Management Circuitry | Hardware and software that manages battery usage, including voltage regulators and sleep mode controllers. | Extending the operational life of an implanted sensor by minimizing power draw during inactive periods [2]. |

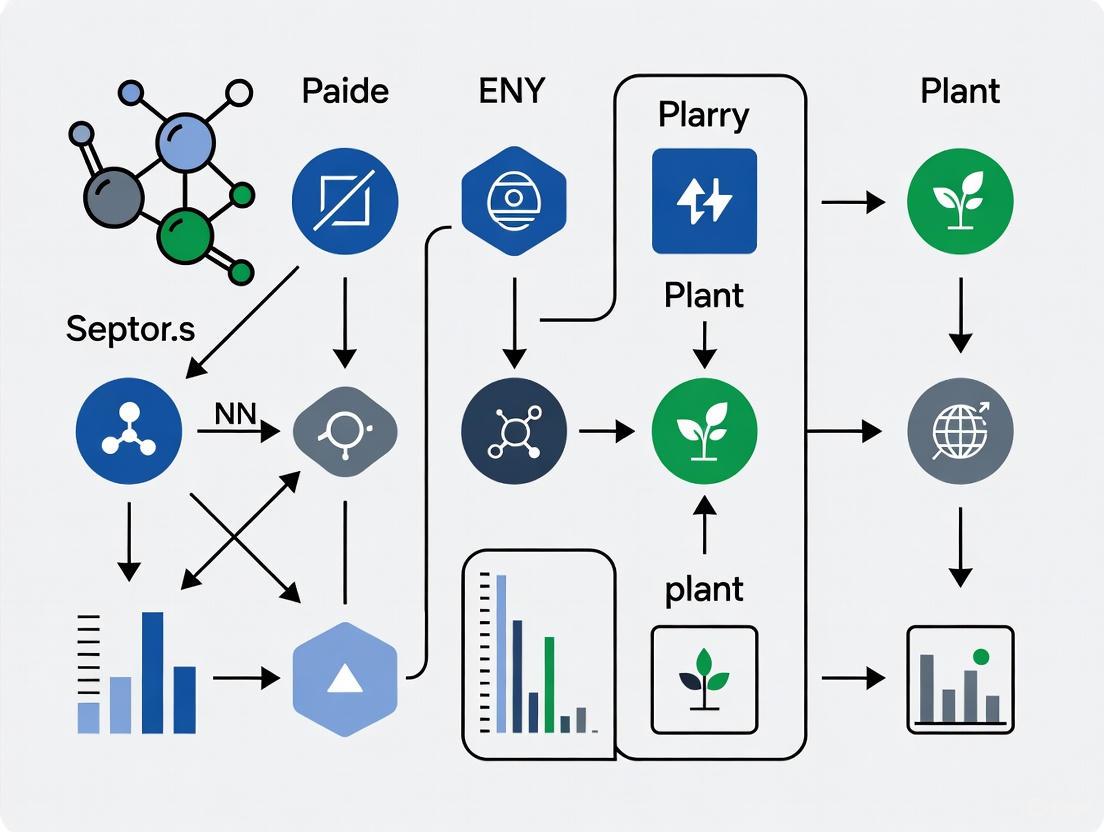

Experimental Workflow: Deploying a Remote Sensor Network

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of deploying and maintaining an energy-efficient sensor network for biomedical field research.

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Hub

This support center provides targeted guidance for researchers employing Lithium Thionyl Chloride (Li-SOCl₂) batteries in long-duration remote field sensor deployments. The following FAQs and troubleshooting guides address common technical challenges to ensure data integrity and optimize energy efficiency in your experiments.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What makes Li-SOCl₂ batteries particularly suitable for remote, long-term field sensors?

Li-SOCl₂ batteries are ideal for these applications due to a combination of unique properties that align with the demands of remote, maintenance-free research equipment [5] [6].

- Ultra-Low Self-Discharge Rate: These batteries exhibit an exceptionally low self-discharge rate of less than 1% per year, one of the lowest of all battery chemistries [5] [7]. This ensures that the vast majority of the battery's stored energy is available to power your sensor over many years, rather than being lost through internal chemical reactions [8].

- High Energy Density: They offer one of the highest energy densities available, up to 700 Wh/kg at the cell level, providing a large amount of power in a compact and lightweight form factor [6].

- Extended Operational Lifespan: Due to their low self-discharge and stable chemistry, bobbin-type Li-SOCl₂ batteries can provide continuous power for 10 to 25 years, making them perfect for remote or maintenance-restricted systems [5]. Superior-quality cells can retain over 70% of their original capacity after 40 years [7].

- Wide Operating Temperature Range: They function reliably across a broad temperature spectrum, typically from -55 °C to +85 °C, and can be engineered for even wider ranges. This makes them suitable for harsh environmental conditions, from arctic cold to desert heat [9] [8].

Q2: What is the "passivation" phenomenon, and how will it affect my field sensor's operation?

Passivation is a fundamental characteristic of Li-SOCl₂ chemistry that researchers must account for in their experimental design [10].

- What it is: During storage or periods of inactivity, a thin protective film of Lithium Chloride (LiCl) forms on the lithium anode. This layer is beneficial as it drastically reduces the self-discharge rate, contributing to the long shelf life [5] [10].

- The Operational Impact: Voltage Delay. The downside of this layer is that when a load is applied after a long storage period, it causes initial high resistance, leading to a temporary voltage drop or "delay" until the discharge reaction breaks down the LiCl layer [5] [7]. This can cause a sensor to fail to start up or transmit data correctly upon initial deployment or after a long dormant period.

- Mitigation Strategy: The voltage delay is usually temporary. The voltage typically recovers to its normal level after a few seconds as the passivation layer is dissipated [10]. For critical applications, design your sensor's power management to include a brief "wake-up" period or specify low-passivation cells from your battery manufacturer.

Q3: Can Li-SOCl₂ batteries handle the high pulse currents required for wireless data transmission?

This depends on the internal construction of the battery cell [5].

- Bobbin-Type Cells: Standard bobbin-type constructions, which are designed for maximum energy density and longevity, are intended for low-current applications and cannot support high pulse currents on their own [5] [7].

- Solutions for High Pulses: For devices requiring periodic high-current bursts for wireless communication (e.g., 2-way data transmission), you have two options:

- Spiral-Wound Cells: These have a larger electrode surface area and are designed to deliver moderate to high pulse currents [5].

- Hyolid Layer Capacitor (HLC) Solutions: A more advanced solution involves coupling a standard bobbin-type Li-SOCl₂ cell with a patented hybrid layer capacitor (HLC). The main cell provides the long-term, low-power background current, while the HLC delivers the high pulses needed for transmission. This approach avoids the high self-discharge associated with consumer-grade supercapacitors [7].

Q4: Are Li-SOCl₂ batteries safe to use in environmental field studies?

With proper handling, they are considered safe and are widely used in professional and industrial applications [8].

- Normal Operation: Under normal conditions, the batteries are safe and feature a non-flammable electrolyte [9].

- Safety Considerations: The electrolyte, thionyl chloride, is a toxic and corrosive compound. Cells must be handled carefully to avoid puncturing or crushing [5]. They must never be recharged, as this can cause overheating or explosion [5]. Always follow manufacturer guidelines for handling, circuit protection, and disposal [5].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor fails to start/transmit after deployment or long inactivity | Voltage Delay from anode passivation [10]. | Allow the battery to power the load for 30-60 seconds. The voltage should recover as the LiCl layer dissipates [10]. |

| Unexpectedly short battery life | High self-discharge due to inferior quality cell; continuous load exceeding design limits; extreme temperature exposure [7]. | Verify average and pulse current draw matches battery specifications. For pulsed applications, use spiral-wound or HLC-equipped cells [5]. Source batteries from reputable suppliers with documented low self-discharge rates [7]. |

| Inability to power 2-way wireless communication modules | Use of a standard bobbin-type cell incapable of delivering required pulse current [7]. | Redesign power solution using a spiral-wound Li-SOCl₂ cell or a bobbin-type cell with an integrated Hybrid Layer Capacitor (HLC) [5] [7]. |

| Reduced performance at low temperatures | Slowed electrochemical reactions, a common trait in all batteries. | Select Li-SOCl₂ chemistry rated for your required low-temperature operation (as low as -60°C). For very cold deployments, consider a built-in heater system if feasible [5] [11]. |

Technical Data Reference

Battery Chemistry Comparison

The following table summarizes key performance metrics of Li-SOCl₂ batteries against other common primary lithium chemistries, highlighting its suitability for long-term deployments [7].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Lithium Battery Chemistries (AA-size typical values)

| Parameter | Li-SOCl₂ (Bobbin) | Li-SOCl₂ (with HLC) | Li Metal Oxide (High Power) | LiFeS₂ | LiMnO₂ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Density (Wh/kg) | 730 | 700 | 185 | 335 | 330 |

| Nominal Voltage (V) | 3.6 | 3.6 to 3.9 | 4.1 | 1.5 | 3.0 |

| Pulse Capability | Low | Excellent | Very High | Moderate | Moderate |

| Passivation | High | None | None | Fair | Moderate |

| Operating Temp. Range | -55°C to 85°C | -55°C to 85°C | -45°C to 85°C | -20°C to 60°C | 0°C to 60°C |

| Self-Discharge Rate | Very Low (<1%/yr) | Very Low | Very Low | Moderate | High |

Research Reagent & Materials Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Materials for Li-SOCl₂ Battery Experimental Research

| Item | Function in Research Context |

|---|---|

| Bobbin-Type Li-SOCl₂ Cell | The core energy source for ultra-long-term, low-power sensor applications; characterized by its high energy density and low self-discharge [5] [7]. |

| Spiral-Wound Li-SOCl₂ Cell | Used for experiments requiring moderate to high pulse currents; trades some energy density for higher power output [5]. |

| Hybrid Layer Capacitor (HLC) | A critical component when paired with a bobbin cell to deliver high pulses for wireless communication without significantly impacting operational lifespan [7]. |

| Programmable Load Tester | Essential for emulating the complex current profiles (standby, average, pulse) of remote sensors to accurately project battery lifetime [12]. |

| Environmental Chamber | For testing battery performance and longevity under controlled extreme temperatures (e.g., -60°C to +85°C) to simulate field conditions [5] [8]. |

| Data Logging Multimeter | To monitor and record voltage and current during discharge, crucial for identifying characteristics like voltage delay and quantifying capacity [12]. |

| Electrocatalyst (e.g., CoPC) | Advanced reagent used in R&D to modify the carbon cathode, improving the reduction rate of SOCl₂ and enhancing high-rate performance [6] [11]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Diagram: Protocol for Testing Voltage Delay

Voltage Delay Characterization Protocol

Objective: To quantify the passivation effect in a Li-SOCl₂ battery after a defined storage period.

Materials:

- Li-SOCl₂ battery cell (subjected to predetermined storage conditions)

- Programmable electronic load

- Data logging multimeter/oscilloscope

- Thermal chamber (if testing temperature dependence)

Methodology:

- Conditioning: Store the test battery at a specific temperature (e.g., 23°C) and relative humidity for a set duration (e.g., 30-90 days) [10].

- Setup: Connect the battery to the programmable load. Attach voltage sense probes directly across the battery terminals to the data logger.

- Load Application: Program the load to apply a continuous discharge current relevant to the target application (e.g., 1C rate).

- Data Acquisition: Initiate the load and simultaneously begin high-speed voltage logging (e.g., 100 ms intervals).

- Analysis:

- Voltage Delay Time (Δt): Measure the time taken for the terminal voltage to recover to within 5% of its stable operating voltage after the load is applied.

- Recovery Profile: Analyze the shape of the voltage recovery curve. A steeper recovery indicates less severe passivation.

Diagram: Power System Design for a Remote Sensor

Power System Design for a Pulsed Remote Sensor

Objective: To architect a robust power supply for a remote sensor that requires periodic high-current pulses for wireless data transmission.

Design Rationale:

- Li-SOCl₂ Bobbin Cell: Serves as the primary energy source, selected for its ultra-low self-discharge and high energy density, ensuring multi-year operational life [7].

- Hybrid Layer Capacitor (HLC): Acts as a complementary power buffer. It is slowly charged by the low-current bobbin cell and rapidly discharged to provide the high current pulses required by the radio transmitter, protecting the primary cell from damaging high-rate loads [7].

- Power Management IC: A critical component that orchestrates the energy flow. It efficiently regulates voltage for the Microcontroller Unit (MCU) and sensors, and manages the charge/discharge cycle of the HLC, activating the radio only when the HLC has sufficient energy.

Implementation Notes: This decoupled architecture is key to optimizing energy efficiency. The main battery never experiences high stress, maximizing its longevity, while the HLC ensures communication reliability.

Understanding Self-Discharge Rates and Passivation Effects on Sensor Lifespan

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is self-discharge in batteries and why is it critical for remote field sensors? Self-discharge is the gradual loss of stored energy in a battery while it is not in use. For remote field sensors, this is critical because a high self-discharge rate can lead to premature power depletion, causing device failure before the expected battery lifespan is reached. This necessitates frequent, costly, and often difficult site visits for battery replacement, especially in inaccessible locations. High-quality primary lithium batteries can achieve self-discharge rates as low as 0.5% to 1% per year, which is essential for supporting maintenance-free operation for decades [13] [14].

Q2: What is the passivation effect in lithium thionyl chloride (LiSOCl₂) batteries? Passivation is a phenomenon in LiSOCl₂ batteries where a thin film of lithium chloride (LiCl) forms on the surface of the lithium anode. This film develops when the lithium metal comes into contact with the thionyl chloride electrolyte [14]. While this layer helps achieve an exceptionally low self-discharge rate (as low as 0.7% per year) by limiting further chemical reactions, it can also cause a temporary voltage delay when a high-power pulse is first demanded, as the film must be broken down [14].

Q3: How does battery construction, like bobbin-type vs. spiral-wound, affect passivation and self-discharge? The cell construction plays a significant role:

- Bobbin-type construction maximizes the passivation effect, leading to the lowest self-discharge rates (as low as 0.7% per year). This makes it ideal for long-term, low-power applications where devices need to operate for 10-40 years [14].

- Spiral-wound construction provides a larger surface area for higher energy flow, supporting applications requiring high current pulses. However, this comes at the cost of a higher self-discharge rate compared to bobbin-type cells [14].

Q4: What is the practical impact of a 3% vs. 0.5% annual self-discharge rate over 10 years? The choice of battery quality has a dramatic long-term impact on remaining capacity. A battery with a 3% annual self-discharge rate can lose up to 30% of its total capacity over 10 years. In contrast, a high-quality cell with a 0.5% annual rate would retain over 95% of its capacity in the same period, making the advertised multi-decade operational lifespans achievable [13] [14].

Q5: How can I test my sensor's battery lifespan without waiting for decades? Researchers and manufacturers use accelerated aging tests. One common method is "accelerating storage," where batteries are stored at elevated temperatures for a predetermined period (e.g., six months) to simulate years of field life. The remaining capacity is then measured to validate the projected lifespan [13]. Microcalorimeters are also used to measure the heat emitted from a cell, which directly correlates to the rate of self-discharge [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unexpectedly Short Sensor Lifespan

Symptoms:

- Sensor ceases operation years before the expected battery lifespan.

- Data transmissions become infrequent or stop entirely.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Verify Load Profile: Confirm that the sensor's actual current draw (including pulse amplitude, duration, and frequency) matches the assumptions used for the initial battery selection. An unaccounted-for high-current pulse can rapidly deplete capacity [13].

- Check Battery Quality: Source batteries from reputable manufacturers. Lower-grade LiSOCl₂ cells can have self-discharge rates up to 3% per year, drastically reducing service life [14].

- Review Environmental Conditions: Extreme temperatures, especially high heat, can accelerate self-discharge and strengthen the passivation layer, leading to more severe voltage delay [13] [14].

Solutions:

- Select a bobbin-type LiSOCl₂ battery from a high-quality manufacturer for applications with low average current draw.

- For applications requiring high pulses, consider batteries with built-in Hybrid Layer Capacitors (HLCs). The capacitor delivers the high power pulses, while the primary cell provides the energy, maintaining a low self-discharge rate [13].

Problem: Sensor Reset or Failure During High-Power Transmission

Symptoms:

- Sensor reboots or fails only during activities like wireless data transmission.

- Voltage sags are observed when a high-current pulse is initiated.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Identify Voltage Delay: This is a classic symptom of passivation. The protective LiCl layer on the anode causes a temporary voltage drop when a high current is suddenly drawn [14].

- Measure Pulse Characteristics: Use an oscilloscope to check the voltage response at the onset of a transmission pulse.

Solutions:

- Design Pulse Profile: If possible, implement a "wake-up" pulse—a brief, smaller current draw before the main high-power pulse—to gently break down the passivation layer.

- Utilize HLC Batteries: Specify batteries with integrated capacitors, which are specifically designed to mitigate this issue by supplying the pulse current directly [13].

Table 1: Impact of Annual Self-Discharge Rate on Long-Term Capacity Retention

| Annual Self-Discharge Rate | Capacity Retention After 10 Years | Suitability for Long-Term Deployment |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5% | ~95% | Excellent: Ideal for multi-decade projects |

| 1% | ~90% | Good: Reliable for long-term use |

| 3% | ~70% | Poor: Risk of premature failure |

Source: Based on data from [13] and [14]

Table 2: Empirical Performance of Commercial LiSOCl₂ Batteries Under Constant Discharge

| Battery Brand | Rated Capacity (Ah) | Performance at 10 mA Discharge | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| EVE | 1.2 | High capacity, stable voltage | Cost-effective, widely available |

| SAFT | 1.2 | High capacity, stable voltage | Established manufacturer |

| TEKCELL | 1.2 | High capacity, stable voltage | |

| TADIRAN | 1.1 | Slightly lower capacity | Known for superior bobbin-type cells with low self-discharge |

Source: Adapted from comparative study data in [14]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Accelerated Storage Test for Lifespan Estimation

Objective: To predict long-term capacity loss and validate a battery's self-discharge rate within a practical timeframe.

Materials:

- New batteries from the manufacturer to be tested.

- Environmental chamber capable of maintaining elevated temperatures (e.g., +55°C to +85°C).

- Precision battery analyzer or tester.

Methodology:

- Initial Capacity Measurement: Begin by fully charging (if rechargeable) or measuring the open-circuit voltage and initial capacity of the primary battery using a standardized discharge test.

- Accelerated Aging: Place the batteries in the environmental chamber at a specified elevated temperature. The temperature and storage duration are calculated based on established models (e.g., Arrhenius equation) to simulate a target number of years. For example, some protocols use storage at 71°C for 6-8 weeks to simulate one year of room temperature storage [14].

- Recovery and Final Measurement: Remove the batteries and allow them to return to room temperature. Measure the remaining capacity using the same standardized discharge test.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the capacity loss and extrapolate the annual self-discharge rate. Compare the results against the manufacturer's specifications.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Self-Discharge via Microcalorimetry

Objective: To precisely measure the heat flow from a battery, which is a direct indicator of its self-discharge rate.

Materials:

- High-sensitivity microcalorimeter.

- Battery samples.

- Temperature-controlled environment.

Methodology:

- Stabilization: Place the battery sample inside the microcalorimeter and allow it to thermally equilibrate.

- Heat Measurement: The microcalorimeter measures the infinitesimal amount of heat emitted by the battery. This heat is a direct result of the internal chemical reactions causing self-discharge [13].

- Calculation: The heat flow data is used to calculate the exact rate of self-discharge. This method is highly accurate for quantifying very low self-discharge rates in quality primary cells [13].

Conceptual Diagrams

Passivation Mechanism and Effects

Battery Lifespan Test Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Sensor Energy and Passivation Research

| Item | Function / Relevance in Research |

|---|---|

| Bobbin-Type LiSOCl₂ Batteries | The primary power source under study; chosen for their superior passivation and ultra-low self-discharge characteristics [14]. |

| Environmental Chamber | Provides controlled temperature and humidity for accelerated aging tests and studying environmental effects on battery performance [13]. |

| Battery Analyzer / Cycler | Precisely controls discharge profiles (constant current, pulsed) and measures capacity, voltage, and efficiency [14]. |

| Microcalorimeter | A highly sensitive instrument that measures heat flow from a battery, allowing for direct calculation of self-discharge rates [13]. |

| Oscilloscope | Captures transient voltage responses during current pulses, crucial for identifying and quantifying voltage delay caused by passivation. |

| Data Logging Multimeter | Tracks long-term voltage trends of batteries under test in various storage conditions. |

| Hafnium Dioxide (HfO₂) | A high-k dielectric material studied for use in advanced passivation layers for electronic sensor components, improving stability and reducing leakage currents [15]. |

| SU-8 Photoresist | A common polymer used for passivating and insulating electrodes and contacts on sensor chips, protecting them from ionic solutions and environmental damage [15]. |

For researchers deploying remote field sensors, operating effectively in extreme temperatures is a dual challenge. It is critical not only for data integrity but also for energy efficiency, as excessive heating or cooling of electronics is a significant drain on limited power resources. This technical support center provides practical guidance to help scientists troubleshoot common temperature-related issues, validate sensor performance, and implement strategies that extend the operational lifetime of their research deployments in harsh environments. Adhering to international standards and understanding the underlying engineering principles are foundational to success in these demanding applications.

Troubleshooting Guides

Sensor Malfunction in Low-Temperature Environments

Observed Problem: Sensor readings become erratic, show significant drift, or the sensor fails to output data entirely when deployed in cold environments.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action & Question | Rationale & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify Stored Specifications: Check the sensor's datasheet for its official operating temperature range. | Commercial, industrial, and military-grade components have different tolerances. A sensor rated for 0°C to +70°C will fail in a -20°C environment [16]. |

| 2 | Inspect for Condensation: Was the sensor exposed to a warm, humid environment prior to deployment? | Condensation forming on internal circuitry can cause short circuits or corrosion when it freezes. Always acclimate and use conformal coatings where appropriate [16]. |

| 3 | Check Power Supply: Use a multimeter to verify voltage at the sensor terminals in situ. | Battery output voltage can drop significantly in cold weather. Regulators may fail to maintain required voltage, and wiring can become brittle and crack [16]. |

| 4 | Analyze Signal Output: If the sensor is powered, monitor its raw analog or digital output. | The core sensing element itself may be operating outside its physical limits. For example, silicon piezoresistive materials can suffer irreversible damage if used below -55°C [16]. |

Unexplained Data Drift in High-Temperature Environments

Observed Problem: Sensor readings show a gradual, consistent offset that correlates with ambient temperature increases, even when the measured parameter is stable.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action & Question | Rationale & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify Local Heat Sources: Is the sensor installed near equipment that generates heat (e.g., radios, power regulators, or in direct sunlight)? | Localized radiant heat can cause a microclimate around the sensor that is significantly hotter than the ambient environment you intend to measure [16]. |

| 2 | Verify Packaging Material: Check the datasheet for the sensor packaging's "glass transition temperature" (Tg). | Thermosetting epoxy resins used in standard packages can soften and deform above 120°C, inducing mechanical stress on the sensitive element and causing drift [16]. |

| 3 | Perform In-Situ Calibration: Can the drift be characterized and compensated for? | If the drift is consistent, a two-point calibration at two different known field temperatures can create a correction model. For highest accuracy, use a sensor whose calibration is traceable to national standards [17]. |

| 4 | Review Installation: Is the sensor in a proper radiation shield? | A high-quality radiation shield is essential for accurate air temperature measurement. It protects the sensor from solar radiation and other radiative heat sources while allowing free air flow [17]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the definitive standards for sensor operating temperature ranges?

International standards provide the framework for setting and testing sensor temperature ranges. Key standards include [16]:

- IEC 60068 Series: A core set of environmental testing standards from the International Electrotechnical Commission. IEC 60068-2-1 (low temperature) and IEC 60068-2-2 (high temperature) specify standard test procedures.

- MIL-STD-810: A rigorous military standard. Its Method 501.7 (high temperature) and 502.7 (low temperature) define tests for operation from -55°C to +125°C and storage from -65°C to +150°C.

- AEC-Q100/Q103: Automotive industry standards that define specific temperature grades, with Grade 0 requiring operation from -40°C to +150°C.

How do I select a sensor for a mission-critical, remote deployment?

Prioritize sensors that meet or exceed globally recognized performance guidelines, such as those from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). For temperature sensors, the key specifications are [17]:

- Measurement Uncertainty: ±0.1°C or better.

- Measurement Range: -80° to +60°C.

- Time Constant: ≤20 seconds (in 5 m/s wind).

- Calibration: Traceable to national or international standards. Sensors meeting these criteria, like the Campbell Scientific TempVue series, ensure data is accurate, defensible, and comparable across global research sites [17].

Our wireless sensor network (WSN) is experiencing premature node failure. How can we improve longevity?

Premature failure is often an energy imbalance issue, not just a total energy deficit. To optimize efficiency:

- Implement Advanced Clustering: Use a Multi-objective Butterfly Clustering Optimization (MBCO) algorithm. It dynamically selects cluster heads based on residual energy and node density, preventing nodes near the base station from being overloaded and dying first [18].

- Adopt Hybrid Data Fusion: Dynamically adjust data transmission rates and aggregation methods based on event urgency. Transmit raw data for critical events but only compressed or summary data during normal monitoring to save energy [18].

- Enable Cross-Cluster Coordination: Allow clusters to share loads and migrate tasks, balancing energy consumption across the entire network and extending its useful life by over 80 rounds in simulations [18].

What is the relationship between a sensor's time constant and data quality?

The time constant measures how quickly a sensor responds to temperature changes. A shorter time constant is vital for capturing rapid environmental fluctuations. The WMO recommends a time constant of 20 seconds or less. A sensor with a slow time constant will lag behind actual ambient temperatures, introducing error and uncertainty. This is especially critical in low-wind conditions where air mixing is minimal, making data from different sites incomparable [17].

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Validation

Protocol 1: Verifying Sensor Accuracy Against a Reference Standard

This protocol is designed to validate a sensor's measurement uncertainty against a traceable reference, ensuring data defensibility.

Workflow Diagram: Sensor Accuracy Validation

Methodology:

- Equipment: Unit Under Test (UUT) sensor, NIST-traceable reference thermometer, precision climate chamber, data logger.

- Procedure:

- Place the UUT and reference sensor in the climate chamber, ensuring they are in close thermal contact but electrically isolated.

- Set the chamber to a stable target temperature (e.g., -20°C, +23°C, +60°C) within the UUT's specified range.

- Allow the system to reach complete thermal equilibrium. This may take significantly longer than the sensor's time constant.

- Simultaneously record at least 100 readings from both the UUT and the reference standard.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the mean difference (Δ) between the UUT and reference readings. The sensor meets the ±0.1°C accuracy standard if |Δ| ≤ 0.1°C across the tested range [17].

Protocol 2: Characterizing Sensor Time Constant

This protocol measures the sensor's response speed to a step change in temperature, a critical factor for capturing rapid environmental transitions.

Workflow Diagram: Time Constant Characterization

Methodology:

- Equipment: UUT sensor, fast-response reference thermometer, two temperature-controlled environments (e.g., a warm water bath and a cool water bath), high-speed data acquisition system.

- Procedure:

- Stabilize the UUT in the first environment (T1).

- Rapidly transfer the sensor to the second environment (T2). The transfer must be as swift as possible to approximate an ideal step change.

- Immediately begin logging data from the UUT at a high frequency (e.g., 10-100 Hz).

- Data Analysis: Plot the sensor's output over time. The time constant (τ) is the time it takes for the sensor's output to change by 63.2% of the total step change (from T1 to T2). Compare the calculated τ to the WMO recommendation of ≤20 seconds [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function & Relevance to Energy-Efficient Research |

|---|---|

| NIST-Traceable Reference Thermometer | Provides the "ground truth" for in-situ calibration of field sensors, ensuring data accuracy and defensibility. Crucial for validating the performance of your primary sensors without frequent, energy-intensive lab returns [17]. |

| Meteorological-Grade Radiation Shield | Protects sensors from solar radiation and other radiative heat sources. Essential for obtaining accurate air temperature measurements and preventing heat-induced drift that could trigger unnecessary, energy-draining system responses [17]. |

| High-Performance Data Logger | The central hub for data collection and system control. Advanced loggers can execute energy-saving protocols, such as putting sensors into low-power sleep modes and triggering data transmission only during optimal conditions [19]. |

| Multi-Objective Clustering Optimization Software | Implements algorithms like MBCO for Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs). Dynamically manages network topology to balance energy consumption, significantly extending network lifetime by preventing hotspot formation and node failure [18]. |

| Conformal Coating | A protective polymeric layer applied to circuit boards. Guards against condensation, corrosion, and short circuits caused by humidity and frost in extreme environments, enhancing sensor reliability and reducing maintenance energy costs [16]. |

Fundamentals of Energy Harvesting for Maintenance-Free Operation

Energy Harvesting Technologies: A Quantitative Comparison

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of prevalent energy harvesting technologies, enabling informed selection for maintaining remote field sensors.

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Energy Harvesting Technologies

| Technology | Principle | Typical Power Output | Advantages | Limitations | Ideal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Photovoltaic [20] [21] | Converts light into electricity using photovoltaic cells. | µW to mW/cm² (highly dependent on light intensity) [20] | High power density in well-lit conditions; mature technology. | Intermittent (no output in darkness); efficiency drops in low light. [22] | Remote sensors with adequate ambient or solar light. |

| Piezoelectric [23] [21] | Generates electric charge from mechanical stress or vibrations. | µW to mW/cm³ (dependent on vibration frequency and amplitude) [23] | Simple structure; no external voltage source needed; high power density for mechanical sources. [23] | May degrade with excessive stress; AC output requires rectification. [23] | Industrial machinery monitoring, smart floors, and wearable devices. [22] |

| Electromagnetic (Kinetic) [20] [23] | Generates electricity via electromagnetic induction from relative motion between a magnet and a coil. | µJ to mJ per activation (e.g., 30x greater than older kinetic tech) [20] | Robust design; can generate significant energy from consistent motion. [20] | Can be bulky; requires consistent, high-amplitude motion for best output. [20] | Industrial environments with constant vibration or motion. [20] |

| Thermoelectric [23] [21] | Converts heat flow (temperature differences) into electricity via the Seebeck effect. | µW to mW (proportional to ΔT²) [23] | Continuous operation if ΔT is maintained; minimal moving parts. | Low conversion efficiency; requires significant, stable temperature gradient. [22] [23] | Sensors on motors, engines, HVAC systems, or wearable devices using body heat. [22] [23] |

| RF Energy Harvesting [22] [23] | Captures ambient radio frequency waves and converts them to DC power. | µW/cm² (varies with distance from source) [23] | Power available in urban areas with RF signals; works in darkness. | Very low power density; highly dependent on proximity to RF source. [23] | Low-power devices in urban environments with consistent RF signals (e.g., Wi-Fi, cellular). [22] |

Troubleshooting Common Energy Harvesting Systems

FAQ 1: My energy harvesting sensor node frequently resets or experiences power gaps. What could be the cause?

Intermittent power is a common challenge in energy harvesting systems, often caused by the unpredictable nature of ambient energy sources like light, heat, or vibration [20]. To diagnose and resolve this:

- Check Energy Source Stability: Use an oscilloscope to monitor the raw output from your energy harvester (e.g., piezoelectric element or solar cell). Look for significant dips or a complete lack of output that correlate with the resets [23].

- Analyze Power Management Circuit (PMIC): Ensure your PMIC is properly configured. Many modern PMICs, like the e-peas AEM series or the BQ25570, feature a "cold-start" circuit that initiates operation from a very low voltage, but they also require proper configuration of storage elements [23].

- Verify and Size Energy Storage: This is critical. Measure the charge/discharge cycles of your storage device (battery or supercapacitor). The storage must be large enough to supply the load during periods without harvesting. A supercapacitor can be ideal for frequent charge/discharge cycles, while a battery provides higher energy density for longer gaps [23].

FAQ 2: The power output from my piezoelectric harvester is much lower than expected. How can I improve it?

Low output from kinetic harvesters typically stems from mechanical or electrical impedance mismatch.

- Mechanical Tuning: The resonant frequency of your piezoelectric harvester must match the dominant frequency of the environmental vibrations. If mismatched, most of the vibrational energy will not be captured. You may need to physically adjust the harvester's mass or stiffness [23].

- Electrical Load Matching: The electrical load presented by your circuit (sensor and PMIC) must match the optimal load for the piezoelectric element to achieve maximum power transfer. This can be verified and optimized by testing the harvester's output across a range of resistive loads to find the peak power point [23].

- Use a Specialized PMIC: Standard voltage regulators are not efficient for high-impedance sources like piezoelectrics. Use a PMIC specifically designed for such harvesters, like the LTC3588-1, which integrates a low-loss full-wave rectifier and a high-efficiency buck converter [23].

FAQ 3: My electromagnetic harvester in a high-vibration environment has failed prematurely. What are the likely failure modes?

Mechanical failure is a key design consideration for kinetic harvesters in harsh environments [24].

- Fatigue of Moving Parts: The components experiencing repetitive stress, such as the spring or cantilever holding the magnet, can suffer from metal fatigue and fracture. Finite element analysis (FEA) during the design phase can help identify stress concentration points [24].

- Physical Wear and Deterioration: Continuous movement can lead to wear in bearings or guides, increasing mechanical resistance and reducing efficiency. The coil or its connections can also fracture from constant vibration. Potting the assembly can protect the coil and PCB, but the moving mechanical system itself must be designed for the required number of cycles [24].

- Acceleration Analysis: Calculate the maximum acceleration (in g-forces) your harvester will experience. For a vibration of 12 Hz with a 10 mm peak-to-peak amplitude, the maximum acceleration is approximately 2.9 g. While this may not seem high, it is applied millions of times, and the design must withstand these cyclic loads [24].

Experimental Protocols for System Validation

Protocol 1: Characterizing an Ambient Energy Source

Objective: To quantitatively measure the available ambient energy for designing or selecting an appropriate energy harvester.

Materials: Oscilloscope or data acquisition (DAQ) system, appropriate transducer (e.g., accelerometer for vibration, thermocouple for temperature, photodiode for light), and a computer for data analysis.

Methodology:

- Sensor Placement: Securely install the measurement sensor at the intended location of your field sensor.

- Data Logging: Record data continuously for a minimum of one full operational cycle (e.g., 24 hours, one week). Ensure the logging period captures all potential variations (day/night, weekdays/weekends, different machine operating states).

- Parameter Measurement:

- For Vibration: Measure and log frequency (Hz) and amplitude (peak-to-peak in mm or acceleration in g).

- For Thermal: Measure and log the temperature difference (ΔT in °C) over time.

- For Light: Measure and log illuminance (lux) over time.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the average, minimum, maximum, and total duration of available energy. This profile will define the "energy budget" and duty cycle possible for your sensor node.

Protocol 2: Validating a Complete Energy Harvesting Power System

Objective: To verify that the energy harvesting subsystem can reliably power a sensor node through charge/discharge cycles.

Materials: Complete energy harvesting board (transducer, PMIC, storage element), target sensor node, programmable electronic load, oscilloscope, environmental chamber (optional).

Methodology:

- System Integration: Connect the energy harvester to the PMIC and energy storage (supercapacitor or thin-film battery). Connect the sensor node as the load.

- Simulate Operational Cycle: Place the harvester in its target environment (or a chamber that simulates it). Use the sensor's software to define a realistic operational duty cycle (e.g., measure temperature every 5 minutes and transmit data every hour).

- Monitor System Voltages: Use the oscilloscope to probe the voltage across the storage element and the load. Trigger the scope to capture the startup and shutdown sequences.

- Measure Key Metrics:

- Cold Start Voltage: The minimum storage voltage at which the PMIC can restart and power the load.

- Energy Balance: Confirm that the energy harvested over a cycle is greater than the energy consumed by the sensor node over the same period.

- Cycle Lifetime: For designs using batteries, long-term testing is needed to monitor degradation over thousands of charge/discharge cycles.

The diagram below illustrates the core workflow and components of a typical energy harvesting system for a sensor node.

Diagram 1: Energy Harvesting System Architecture.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Energy Harvesting Systems

| Component | Function | Example Parts / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Transducer | Converts a specific form of ambient energy (light, vibration, heat) into raw electrical energy. | Photovoltaic cell; Piezoelectric element (PZT); Thermoelectric Generator (TEG); Electromagnetic harvester (e.g., WePower Gemns [20]). |

| Power Management IC (PMIC) | The "brain" of the system. Manages the harvested energy, performs DC-DC conversion, provides regulated output, and protects the storage element. | e-peas AEM13920 (dual-source) [20]; BQ25570 (optimized for TEGs) [23]; LTC3588-1 (for piezoelectric & solar) [23]. |

| Energy Storage | Stores harvested energy to bridge gaps in energy availability and supply bursts of power for sensing/communication. | Supercapacitor (for high cycle count, quick charge/discharge); Thin-film battery (e.g., THINERGY MEC for higher energy density) [23]. |

| Ultra-Low-Power Microcontroller (MCU) | Executes sensor control, data processing, and communication protocols while minimizing energy consumption. | Select MCUs with specialized deep sleep modes and energy-efficient active states (e.g., sub-µA sleep current). |

| Development/Kits | Accelerates prototyping by providing a pre-assembled platform for testing and validation. | DC2042A demo board (versatile for multiple sources) [23]; Manufacturer-specific evaluation boards (e.g., for e-peas, Analog Devices ICs) [23]. |

Deployment Strategies and Advanced Protocols for Maximum Efficiency

Implementing Optimized Clustering Protocols (e.g., IZOACP) for Load Balancing

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common questions and issues you may encounter while implementing and experimenting with optimized clustering protocols like IZOACP for load balancing in Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs), within the context of energy efficiency research for remote field sensors.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary energy-saving advantage of using IZOACP over traditional protocols like LEACH? IZOACP significantly improves network lifespan and balances energy consumption more effectively. Traditional protocols like LEACH can create "energy holes" where some nodes deplete their energy prematurely due to non-optimal cluster head selection. IZOACP uses an improved zebra optimization algorithm to make a more balanced selection based on multiple factors like residual energy, network density, and communication delay, leading to a 97.56% improvement in network lifespan and a 93.88% increase in throughput compared to LEACH [25].

Q2: My network simulation shows unstable cluster formation. What key parameters should I verify? Unstable clustering often stems from improper configuration of the multi-objective cost function. Ensure your simulation correctly weights these four critical metrics used in advanced protocols [25] [26]:

- Node Residual Energy: Prioritizes nodes with higher energy for cluster head role.

- Intra-cluster Distance: Minimizes the distance between cluster members and their head.

- Network Density: Prevents overloading a single cluster head in dense node regions.

- Communication Delay: Ensures timely data delivery.

Q3: How do protocols handle "free nodes" that are far from any cluster head? Some nodes may consume excessive energy if forced to communicate directly with a distant cluster head. Protocols like EMSA-CRP address this by allowing these "free nodes" to forward their data through the nearest ordinary node, which then relays it to the cluster head, preventing localized energy imbalance and premature node failure [26].

Q4: What is a common sign that my sensor network is experiencing high packet loss, and how can I investigate it?

A key metric is the CaptureLoss notice in Zeek (Bro) network monitoring software, which indicates the sensor is observing gaps in traffic streams. You can query these logs directly. High capture loss can be caused by hardware interface errors, insufficient resources, or the sensor being unable to keep up with the traffic rate. Use tools like capstats to monitor network interface card (NIC) throughput and drop rates in real-time [27].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Rapid Energy Depletion in Specific Nodes

- Symptoms: A few nodes die significantly earlier than others, potentially creating network partitions.

- Possible Causes:

- Imbalanced Cluster Head Selection: The protocol is not adequately considering residual energy or node degree (density).

- Static Clustering Ratio: The ratio of cluster heads to member nodes is fixed and not adapting to decreasing network density over time [26].

- Solutions:

Problem: Low Packet Delivery Rate and High Latency

- Symptoms: The base station receives only a fraction of the data sent, and end-to-end delay is high.

- Possible Causes:

- Poor Inter-cluster Routing: The multi-hop paths between cluster heads and the base station are suboptimal.

- Network Congestion: Cluster heads are overloaded with data from too many members.

- Solutions:

- Optimize Inter-cluster Routing: Implement a dynamic adaptive routing mechanism, like the one in IZOACP, that selects paths based on node distance, residual energy, and real-time load status [25].

- Check for Interface Errors: In real-world testbeds, use commands like

ip -s linkandethtool -Sto monitor your sensor node's network interfaces for errors, drops, or overruns that cause packet loss [27].

Problem: Meta-heuristic Algorithm Converges to Local Optima

- Symptoms: The clustering optimization algorithm gets stuck with a suboptimal network configuration and does not find a better solution.

- Possible Causes:

- Lack of Population Diversity: The algorithm's search agents (e.g., zebras, fire hawks) become too similar.

- Solutions:

- Integrate Hybrid Strategies: Use methods from recent research, such as incorporating a Gaussian mutation strategy or an opposition-based learning mechanism (as in IZOACP) to help the algorithm escape local optima [25].

- Adjust Algorithm Parameters: Fine-tune parameters specific to the optimizer, such as population size and convergence criteria.

Performance Data and Experimental Protocols

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Clustering Protocols

The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies, providing a benchmark for your experimental results. The data is based on simulation experiments comparing protocols like IZOACP, EMSA-CRP, and others against benchmarks like LEACH [25] [26] [29].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Advanced Clustering Protocols

| Protocol | Key Optimization Technique | Network Lifespan Improvement | Throughput Improvement | Energy Consumption Reduction | Key Experimental Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IZOACP [25] | Improved Zebra Optimization Algorithm | 97.56% (vs. LEACH, DMaOWOA) | 93.88% (vs. LEACH, DMaOWOA) | Significantly outperforms benchmarks | Network size: 100m x 100m; Node count: 100-500; Initial energy: 2J |

| MBCO [29] | Multi-objective Butterfly Optimization | Improves network lifetime by 83.05 rounds (vs. FDAM, EOMR-X) | Packet delivery rate increased by 5.1% | Reduces energy consumption by 6.69 J | — |

| EMSA-CRP [26] | Enhanced Mantis Search Algorithm | Effectively extends network lifetime | — | Optimizes energy utilization efficiency | Tested in 2D & 3D environments with identical and varying initial energy levels |

| CTRF [28] | Fire Hawk Optimizer & Trust Management | — | Improves throughput, reduces packet loss | Balances energy consumption with security | Includes malicious node attack scenarios |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Validating Cluster Head Selection

This protocol outlines the methodology for evaluating the energy efficiency of a cluster head selection mechanism, as used in studies like IZOACP and EMSA-CRP [25] [26].

Objective: To measure the impact of a multi-objective cluster head selection algorithm on network lifetime and energy consumption balance.

Materials & Reagents: Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Network Simulator (NS2/NS3) | Provides a controlled environment to model sensor nodes, radio propagation, and protocol behavior. | NS2, NS3, OMNeT++ [28] |

| WSN Simulation Framework | Defines the network topology, initial node energy, and data traffic patterns. | Area: 100m x 100m to 500m x 500m; Nodes: 100-500 [25] |

| Protocol Implementation Code | The script of the clustering protocol to be tested (e.g., IZOACP, LEACH for comparison). | Implemented in C++, Python, or using simulator-specific modules. |

| Data Analysis Scripts | Custom scripts (e.g., in Python/MATLAB) to parse log files and calculate performance metrics. | Metrics: Network lifespan, throughput, energy consumption variance. |

Methodology:

- Setup:

- Configure the simulation environment with a defined number of sensor nodes randomly deployed in a target area.

- Set uniform initial energy for all nodes to establish a baseline.

- Experimental Group:

- Implement the proposed clustering protocol (e.g., IZOACP) that uses a multi-objective cost function for cluster head selection. The cost function should integrate:

- Control Group:

- Implement a baseline protocol like LEACH for performance comparison.

- Execution:

- Run the simulation for multiple rounds until all node energy is depleted or the network is partitioned.

- Log data for each round, including: which nodes are cluster heads, energy levels of all nodes, number of packets received at the base station, and end-to-end delay.

- Data Analysis:

- Network Lifespan: Calculate the number of rounds until the first node dies (stability period) and until x% of nodes die.

- Throughput: Measure the total number of data packets successfully delivered to the base station over the simulation time.

- Energy Consumption Balance: Calculate the standard deviation of remaining energy across all nodes at the end of the stability period. A lower value indicates better load balancing.

Workflow and System Diagrams

IZOACP Clustering and Routing Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated process of cluster formation and inter-cluster routing as implemented in protocols like IZOACP [25].

Meta-heuristic Optimization Process for Clustering

This diagram outlines the general structure of bio-inspired optimizers (e.g., ZOA, FHO) used to solve the NP-hard problem of optimal cluster head selection [25] [28].

Dynamic Adaptive Inter-Cluster Routing to Minimize Transmission Energy

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is dynamic adaptive inter-cluster routing, and why is it critical for energy efficiency in WSNs? In a clustered Wireless Sensor Network (WSN), sensor nodes are grouped into clusters, each led by a Cluster Head (CH) responsible for data aggregation and transmission to the Base Station (BS). Dynamic adaptive inter-cluster routing intelligently selects the multi-hop path that CHs use to relay data to the BS, as a long-distance, single-hop transmission is a major source of energy drain [30] [31]. This routing process is "dynamic" and "adaptive" because it continuously considers real-time network conditions—such as the remaining energy of potential relay nodes, the distance to be covered, and network load—to select the most energy-efficient path at any given moment. This prevents the premature energy depletion of CHs, especially those farther from the BS, thereby significantly extending the operational lifetime of the entire network [25] [32].

Q2: My network's nodes are dying too quickly, creating "energy holes." How can adaptive routing help? The premature death of nodes, often leading to "energy holes," is frequently caused by an unbalanced energy load, where CHs closer to the BS are overburdened with relay traffic [33]. A dynamic adaptive routing protocol directly addresses this by distributing the energy-intensive relay workload across multiple nodes. Instead of a fixed path that consistently drains the same set of nodes, the protocol selects paths based on the current residual energy of nodes [25] [31]. Furthermore, some advanced protocols incorporate mobile sinks or Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) to collect data, dynamically changing the effective distance for transmission and preventing static hotspots around the BS [33].

Q3: What are the common key parameters used to select the optimal inter-cluster path? Advanced protocols use a combination of metrics to make a holistic routing decision. The most common parameters are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Optimal Inter-Cluster Path Selection

| Parameter | Role in Path Selection | Protocol Example |

|---|---|---|

| Residual Energy | Prevents overusing low-energy nodes; paths are chosen via nodes with higher energy. [25] [31] | IZOACP [25], CEECR-based [31] |

| Distance | Minimizes total transmission energy by favoring shorter hops. [30] [31] | MSSO & Minimum Spanning Tree [30] |

| Node Load/Density | Balances traffic to avoid congestion and buffer overflow on a single node. [25] [31] | IZOACP [25] |

| Node Direction | Ensures data progresses towards the base station, avoiding backward or inefficient paths. [30] | MSSO-based Protocol [30] |

| Link Quality | Selects reliable links with low error rates to avoid energy-wasting retransmissions. [34] | EECRP-HQSND-ICRM [34] |

Q4: I'm concerned about data security. Does energy-efficient routing compromise security? While traditional protocols often separate energy efficiency from security, newer frameworks are designed to integrate both. It is a valid concern because encryption can be computationally expensive, consuming extra energy. However, modern solutions like the SEI2 scheme employ collaborative data encryption at both the CH and BS levels. This approach distributes the security overhead, protecting data from eavesdropping without placing an unsustainable computational burden on a single node, thereby maintaining energy efficiency [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Rapid Energy Depletion in Specific Cluster Heads

- Symptoms: Consistent early death of CHs that are one or two hops away from the BS; a sharp drop in network throughput after a certain number of operational rounds.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Static Routing Paths. The routing protocol is not adaptive and is using the same CHs for relay in every round.

- Solution: Implement a dynamic protocol that re-calculates routes each round based on residual energy. Consider protocols like the Improved Zebra Optimization Algorithm Clustering Protocol (IZOACP), which uses residual energy as a direct input for path selection [25].

- Cause 2: Ignored Load Balancing. The protocol selects paths based only on distance or energy, without considering the number of data packets a node is already handling.

- Solution: Modify the routing cost function (the formula that evaluates paths) to include a "node load" or "node degree" parameter. This ensures that traffic is distributed away from already congested nodes [31].

- Cause 1: Static Routing Paths. The routing protocol is not adaptive and is using the same CHs for relay in every round.

Problem: High End-to-End Data Transmission Delay

- Symptoms: Long lag between data sensing at a node and its receipt at the BS; applications requiring real-time data become ineffective.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Excessively Long Multi-Hop Chains. While multi-hop saves energy, an unnecessarily long chain of hops can accumulate delay.

- Solution: Optimize the trade-off between energy and delay. Protocols like HMEA (Hybrid Memetic Evolutionary Algorithm) are designed to find this balance, ensuring paths are energy-efficient without being prohibitively slow [32].

- Cause 2: Congestion at Relay Nodes. A popular relay node becomes a bottleneck, causing packets to wait in its queue.

- Solution: Introduce a dynamic adaptive routing mechanism that considers real-time load status. If a node's buffer is nearing capacity, the routing algorithm can dynamically find an alternative path [25].

- Cause 1: Excessively Long Multi-Hop Chains. While multi-hop saves energy, an unnecessarily long chain of hops can accumulate delay.

Problem: Protocol Overhead is Consuming Too Much Energy

- Symptoms: High energy consumption even during periods of low data sensing; a significant portion of network traffic is control packets (for route discovery, cluster formation, etc.).

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Frequent Re-clustering and Re-routing. The network is performing global reconfiguration too often.

- Solution: Adjust the protocol's update cycle. Implement a fuzzy logic system, as seen in some protocols, to intelligently decide when to re-cluster based on network stability metrics, rather than doing it on a fixed timer [35]. Additionally, use optimized algorithms like the modified Dijkstra's algorithm that neglect non-essential paths to reduce computational complexity during route calculation [34].

- Cause: Frequent Re-clustering and Re-routing. The network is performing global reconfiguration too often.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Multi-Strategy Fusion Snake Optimizer (MSSO) with Minimum Spanning Tree This protocol uses an enhanced snake optimizer (MSSO) for selecting Cluster Heads and relay nodes, and a minimum spanning tree for planning inter-cluster routes [30].

- Experimental Setup: Simulations are typically run in a MATLAB/NS2 environment with 100-200 nodes randomly deployed. The performance is measured against protocols like LEACH, ESO, and GWO [30] [32].

- Key Workflow: The diagram below illustrates the core process of this protocol.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of MSSO Protocol [30]

| Performance Metric | Improvement Over LEACH, ESO, etc. |

|---|---|

| Energy Consumption | Reduced by at least 26.64% |

| Network Lifetime | Increased by at least 25.84% |

| Network Stable Period | Extended by at least 52.43% |

| Network Throughput | Boosted by at least 40.99% |

Protocol 2: Improved Zebra Optimization Algorithm Clustering Protocol (IZOACP) IZOACP solves the NP-hard problem of CH selection by integrating a Zebra Optimization Algorithm with a Gaussian mutation strategy and opposition-based learning [25].

- Experimental Setup: The protocol is evaluated against LEACH, DMaOWOA, and ARSH-FATI-CHS in a defined area with a specific BS location. Key energy parameters are defined (e.g., ETX = ERX = 30 nJ/bit) [25] [31].

- Key Workflow: The logical flow of the IZOACP protocol is shown below.

Table 3: Performance Gains of IZOACP Protocol [25]

| Performance Metric | Improvement Over LEACH, DMaOWOA, etc. |

|---|---|

| Network Lifespan | Improved by 97.56% |

| Throughput | Improved by 93.88% |

| Transmission Delay | Reduced by 10.12% |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools for WSN Routing

| Tool/Solution | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| MATLAB Simulator | A primary platform for algorithm development, testing, and performance evaluation (e.g., measuring energy consumption, lifetime) [31] [32]. |

| Network Simulator 2 (NS2) | A discrete-event simulator used for modeling network protocols, including node communication, packet transmission, and energy usage [32]. |

| Multi-Strategy Fusion Snake Optimizer (MSSO) | An optimization algorithm used to select optimal Cluster Heads and relay nodes, avoiding local optima and improving convergence [30]. |

| Improved Zebra Optimization Algorithm (IZOA) | A metaheuristic algorithm used to solve the NP-hard problem of cluster head selection, enhanced to avoid premature convergence [25]. |

| Minimum Spanning Tree Algorithm | A graph theory algorithm used to build the most energy-efficient inter-cluster routing tree, minimizing the total communication cost [30]. |

| Fuzzy C-Means (FCM) Algorithm | A clustering algorithm integrated into optimization processes to improve intra-cluster compactness and the quality of cluster formation [30]. |

| Gaussian Mutation Strategy | A technique used in optimization algorithms to increase population diversity and explore a wider search space, preventing stagnation [25]. |

Leveraging Metaheuristic Algorithms (PSO, ACO, GA) for System Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common metaheuristic algorithms used for optimizing energy efficiency in Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs)? The most commonly employed metaheuristic algorithms for enhancing energy efficiency in WSNs are Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), and Genetic Algorithms (GA). Each has distinct operational principles and application strengths [36]. PSO is inspired by the social behavior of bird flocking, ACO mimics the foraging behavior of ants using pheromone trails, and GA is based on the process of natural selection, utilizing operators like selection, crossover, and mutation [37] [38] [39].

Q2: My WSN simulation is suffering from premature convergence, where the algorithm gets stuck in a local optimum. How can I address this? Premature convergence is a frequent challenge, often caused by an imbalance between exploration (searching new areas) and exploitation (refining known good areas) [36]. You can mitigate this by:

- Dynamic Parameter Adjustment: Implement mechanisms that adapt algorithm parameters during execution. For example, in ACO, use an adaptive pheromone decay rate that increases exploration early on and exploitation later [40].

- Hybrid Approaches: Combine a global search algorithm (e.g., GA) with a local search method (e.g., hill climbing) to refine solutions and escape local optima [41].

- Ensure Population Diversity: In population-based algorithms like GA and PSO, carefully tune parameters like mutation rate and inertia weight to maintain a diverse set of candidate solutions throughout the optimization process [36].

Q3: How can I design a fitness function that simultaneously optimizes for energy consumption, coverage, and network lifetime? The key is to create a multi-objective fitness function. For instance, the Pareto-optimized Genetic Algorithm (PGAECR) combines clustering and routing decisions into a single chromosome evaluated by a fitness function that directly considers total energy consumption, residual energy balance, and load distribution [42]. Another approach is the Modified ACO (MACOA), which uses a heuristic function incorporating energy consumption, reliability, bandwidth, and path distance into a unified framework [40].

Q4: What are the primary energy-consuming activities in a sensor node that my optimization model should target? The main sources of energy drain in a sensor node are [39]:

- Data Transmission: The radio transmission is the most energy-intensive operation. The energy required to transfer 1 bit of data is significantly higher than that for processing 1 bit.

- Data Reception: The energy cost of listening to the radio channel and receiving data is also substantial.

- Data Processing: While less costly than communication, the energy used for computation, especially in data aggregation at cluster heads, is non-trivial.

- Sensing: The energy required to power the physical sensor and acquire data from the environment.

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Network Coverage After Deployment

Problem: The sensor node deployment results in inadequate coverage of the Region of Interest (ROI), leaving monitoring gaps or "coverage holes." Solution:

- Step 1: Apply a Probabilistic Coverage Model. Use a model based on Euclidean distance to detect coverage holes in the initial deployment. This model calculates the probability that a target is covered by at least one sensor node [37] [41].

- Step 2: Integrate an Enhanced PSO (EPSO) Algorithm. Implement an EPSO that avoids deploying nodes in close proximity. The algorithm's fitness function should be designed to maximize the coverage rate [41].

- Step 3: Utilize Delaunay Triangulation (DT). Combine EPSO with DT to identify and cover the holes by optimizing the position of the remaining sensor nodes [41].

Rapid Energy Depletion and Short Network Lifespan

Problem: Certain nodes in the network deplete their energy much faster than others, leading to network partitioning and a short overall system lifetime. Solution:

- Step 1: Implement Load-Balancing Clustering. Use a Genetic Algorithm for Energy-efficient Clustering and Routing (GECR). Ensure its fitness function accounts not only for the data from cluster members but also for the relay load from previous hop nodes to accurately model Cluster Head (CH) energy consumption [39].

- Step 2: Use an Improved ACO for Routing. Apply a Modified ACO (MACOA) that incorporates a load-balancing factor in its path selection. This prevents overloading specific paths and nodes, distributing energy consumption more evenly across the network [40].

- Step 3: Adopt a Pareto-based GA (PGAECR). This algorithm integrates optimal solutions from previous network rounds into the initial population of the current round, promoting energy consumption balance and directly extending network longevity [42].

Algorithm Exhibits Slow Convergence or High Computational Overhead

Problem: The metaheuristic algorithm takes too long to find a high-quality solution, making it impractical for large-scale networks or time-sensitive redeployment. Solution:

- Step 1: Optimize Algorithm Parameters. For PSO, carefully define the inertia weight and acceleration factors [41]. For GA, tune the population size, crossover, and mutation rates. Parameter tuning is critical for convergence speed and solution quality [36].

- Step 2: Leverage Historical Solutions. In network rounds, do not initialize the population randomly. Instead, add the optimal solution from the previous network round to the initial population to improve search efficiency and convergence speed [39] [42].

- Step 3: Simplify the Solution Encoding. For PSO, consider an Enhanced PSO (EPSO) that generates 'N' one-dimensional swarms instead of one N-dimensional swarm, which can reduce computational complexity [41].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Node Deployment for Maximum Coverage using SCPSO

Aim: To achieve optimal sensor node placement that maximizes area coverage while minimizing the number of nodes and mitigating energy consumption. Methodology:

- Data Collection & Preprocessing: Use a sensor deployment dataset (e.g., from Kaggle). Preprocess the data using Z-score normalization (to standardize features) and Independent Component Analysis (ICA) for feature extraction and dimensionality reduction [37].

- Algorithm Initialization: Configure the Scalable coverage-based PSO (SCPSO) parameters: swarm size, iteration count, and probabilistic coverage model based on Euclidean distance [37].

- Fitness Evaluation: The fitness function is designed to maximize the coverage rate (CR) within the Region of Interest (ROI).

- Position Update: Particle positions (sensor node locations) are updated iteratively based on individual and swarm best positions, guided by the coverage model to detect and fill gaps.

- Validation: Measure the final coverage rate, the number of nodes required, and the computation time.

Quantitative Results from Literature: Table 1: Performance Metrics of SCPSO for Node Deployment [37]

| Metric | Performance under Optimized Deployment |

|---|---|

| Coverage Rate (with 50 nodes) | 0.9971 (99.71%) |

| Best Achievable Coverage | 99.95% |

| Computation Time | 0.008 seconds |

Protocol: Energy-Efficient Clustering and Routing using GECR

Aim: To extend network lifetime by forming optimal clusters and routing paths that minimize and balance total energy consumption. Methodology:

- Network Model Setup: Define a network of sensor nodes with permanent Cluster Heads (CHs) that have higher energy capacity. The energy model should account for data transmission, reception, and aggregation [39].

- Chromosome Encoding: Design a chromosome that combines the clustering scheme (which node belongs to which CH) and the routing scheme (how CHs communicate to the sink) into a single representation [39].

- Fitness Calculation: The fitness function should be computed directly from the total energy consumed by all sensor nodes for a given clustering and routing scheme, rather than relying solely on distance proxies [39].

- Load-Balanced Selection: Incorporate the load on CHs, including data from their cluster members and relay traffic from previous hop nodes, into the fitness evaluation [39].

- GA Operations: Run the Genetic Algorithm with selection, crossover, and mutation operators over multiple generations to evolve the best solution.

Quantitative Results from Literature: Table 2: Performance Comparison of Clustering and Routing Algorithms [39]

| Algorithm | Key Performance Findings |

|---|---|

| GECR (Proposed) | Consumed the smallest amount of energy in all network rounds. Had the most living nodes at most times, indicating the longest network lifetime. Achieved the lowest variances in the loads on the CHs. |

| GACR | Performance was inferior to GECR in terms of load balancing, network life cycle, and energy consumption. |

| GAR | Performance was inferior to GECR in terms of load balancing, network life cycle, and energy consumption. |

| ASLPR | Performance was inferior to GECR in terms of load balancing, network life cycle, and energy consumption. |

Protocol: Reliable Routing using Modified ACO (MACOA)

Aim: To find optimal data routing paths that improve energy efficiency and routing reliability while balancing network load. Methodology:

- Heuristic Function Design: Create a multi-objective heuristic function that simultaneously considers energy consumption, reliability (e.g., link quality), bandwidth, and path distance [40].