Optimizing CRISPR-Cas9 Editing Efficiency in Plants: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and scientists aiming to enhance the efficiency and precision of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in plants.

Optimizing CRISPR-Cas9 Editing Efficiency in Plants: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic guide for researchers and scientists aiming to enhance the efficiency and precision of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in plants. It explores the foundational principles governing editing success, delves into advanced methodological optimizations—from Cas protein engineering to reagent delivery—and offers practical troubleshooting strategies for common experimental hurdles. A dedicated section on validation and comparative analysis equips readers to critically assess editing outcomes and select the most suitable tools for their specific plant systems. By synthesizing the latest research and techniques, this resource aims to empower the development of improved crop varieties and advance plant biotechnology.

Understanding the Core Principles and Key Factors Governing CRISPR Efficiency in Plants

Troubleshooting Guide: Common CRISPR-Cas9 Issues in Plant Research

FAQ 1: Why is my CRISPR editing efficiency low in plant cells?

Problem: Low frequency of indels or successful edits in regenerated plant lines.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Inefficient Guide RNA Design: The sgRNA sequence is critical for effective binding and cleavage.

- Solution: Utilize design tools (e.g., CHOPCHOP, Synthego design tool) to select gRNAs with high predicted on-target efficiency. Ensure the target sequence is unique to avoid off-target effects and has a GC content between 40-80% for stability [1].

- Solution: For plant genomes, verify the absence of similar sequences, especially in polyploid species where multiple gene copies exist [2].

Suboptimal Delivery Method: The method used to deliver CRISPR reagents into plant cells greatly impacts efficiency.

- Solution: Consider using RNP (Ribonucleoprotein) complexes pre-assembled from Cas9 protein and synthetic sgRNA. This allows for rapid delivery and nuclease activity, reducing the chances of off-target effects and DNA vector integration. In tomato protoplasts, RNP delivery led to detectable DSBs within 6 hours [3].

- Solution: For stable transformation, Agrobacterium-mediated delivery is common, but it can lead to variable results. Explore transient transformation methods or the use of plant developmental regulators to induce de novo meristems for recovering non-transgenic edited plants [2].

High Fidelity of Endogenous Repair: Plant cells often preferentially repair DSBs precisely, limiting the accumulation of desired indels.

- Solution: A recent study in tomato protoplasts found that precise repair can account for up to 70% of all repair events, explaining the gap between high cleavage rates and lower observed indel rates [3]. Kinetic modeling suggests that the timing of reagent delivery and the window for error-prone repair (NHEJ) are critical. Optimizing the transformation and regeneration protocol to capitalize on the peak periods of error-prone repair is essential.

FAQ 2: How can I reduce off-target effects in my plant experiments?

Problem: Unintended edits at genomic sites with sequences similar to the target.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

gRNA Specificity: The designed gRNA may have near-complementary matches to other genomic regions.

Choice of Cas Nuclease: The standard SpCas9 (Streptococcus pyogenes) can tolerate some mismatches between the gRNA and DNA.

- Solution: Use high-fidelity Cas9 variants such as eSpCas9(1.1), SpCas9-HF1, or HypaCas9, which are engineered to reduce off-target cleavage while maintaining on-target activity [4].

- Solution: Use Cas9 nickase (Cas9n). Employing two gRNAs that target opposite strands to create a double-strand break from two adjacent single-strand nicks significantly improves specificity, as it is unlikely that two off-target nicks will occur in close proximity [4].

FAQ 3: What is the best way to deliver CRISPR reagents for DNA-free editing in plants?

Problem: Integration of foreign DNA (e.g., plasmid backbone) into the plant genome, which can lead to regulatory concerns.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Reliance on DNA Vector Delivery: Standard methods using plasmids delivered via Agrobacterium or bombardment can result in random integration.

- Solution: Protoplast Transformation with RNPs. Isolate plant protoplasts and transfert them directly with pre-assembled Cas9 protein and sgRNA complexes. This is a DNA-free method and allows for high editing efficiency, as demonstrated in larch and tomato [3] [5]. The challenge remains the efficient regeneration of whole plants from protoplasts for many species.

- Solution: Particle Bombardment of RNPs or IVT RNA. Coat gold or tungsten microparticles with CRISPR reagents (RNPs or in vitro transcribed RNA) and bombard them into plant cells. This method avoids the use of Agrobacterium and can be used for a wider range of plant species [2].

Quantitative Data on CRISPR-Cas9 Repair Dynamics in Plants

The following table summarizes key findings from a 2024 study that used single-molecule sequencing (UMI-DSBseq) to quantify DSB induction and repair dynamics at three endogenous loci in tomato protoplasts. This data provides a benchmark for expected efficiencies in plant systems [3].

Table 1: Kinetics of CRISPR/Cas9-Induced DSB Repair in Tomato Protoplasts (RNP Delivery)

| Target Gene | Maximum Cleavage Efficiency | Final Indel Frequency (at 72h) | Peak DSB Detection | Key Finding on Repair |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PhyB2 | 88% | 41% | 36-48 hours | Highest cleavage and indel efficiency among targets. |

| CRTISO | 64% | 15% | 24 hours | Demonstrates that high cleavage does not guarantee high indels. |

| Psy1 | ~80% | ~20% | 24-36 hours | ~12% of molecules remained unrepaired DSBs at 72h. |

| General Observation | Up to 88% of molecules can be cleaved | Indels ranged from 15-41% | DSBs detected as early as 6h | Precise repair accounted for up to 70% of all repair events, limiting indel accumulation. |

Experimental Protocol: DNA-Free Genome Editing in Plant Protoplasts using RNP Complexes

This protocol is adapted from recent studies in tomato and larch for evaluating CRISPR efficiency in a DNA-free context [3] [5].

Objective: To achieve targeted mutagenesis in plant cells without using DNA vectors.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- Cas9 Protein: Purified Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 nuclease.

- Synthetic sgRNA: Chemically synthesized single-guide RNA, designed for your target gene. Synthetic sgRNA offers advantages including high purity, consistency, and no need for cloning [1].

- Plant Material: Leaves from sterile seedlings of your target species (e.g., tomato, larch).

- Protoplast Isolation Solution: Enzyme solution containing cellulase and macerozyme to digest cell walls.

- PEG Solution: Polyethylene glycol solution to facilitate transfection.

- W5 and MMg Solutions: Washing and resuspension buffers for protoplasts.

Methodology:

Protoplast Isolation:

- Harvest young leaves and slice them into thin strips.

- Incubate the leaf strips in the enzyme solution in the dark for several hours (e.g., 6-16h) with gentle shaking.

- Purify the released protoplasts by filtering through a mesh and centrifuging through a sucrose or mannitol gradient. Resuspend the protoplast pellet in W5 solution and let rest on ice.

- Critical Parameter: Optimization of enzyme concentration and incubation time is crucial for obtaining a high yield of viable protoplasts (>90% viability) [5].

RNP Complex Assembly:

- In a tube, pre-complex the Cas9 protein and synthetic sgRNA at a molar ratio of 1:2 to 1:4 (e.g., 10 µg Cas9 with 3-5 µg sgRNA).

- Incubate at 25°C for 15-30 minutes to form the active RNP complex.

Protoplast Transfection:

- Count the protoplasts and resuspend them in MMg solution.

- Aliquot protoplasts (e.g., 2 x 10^5 per sample) into a tube.

- Add the assembled RNP complex directly to the protoplasts.

- Add an equal volume of PEG solution to the mixture and mix gently. Incubate at room temperature for 10-30 minutes to allow transfection.

- Critical Parameter: The concentration and incubation time of PEG must be optimized to balance high transformation efficiency with low cytotoxicity [5].

Incubation and DNA Extraction:

- Slowly stop the transfection reaction by adding W5 solution.

- Wash the protoplasts and resuspend in a culture medium.

- Incubate the transfected protoplasts in the dark for 48-72 hours to allow for DNA repair and mutation fixation.

- Harvest the protoplasts by centrifugation and extract genomic DNA using a standard CTAB or commercial kit.

Analysis of Editing Efficiency:

- Amplify the target genomic region by PCR and subject the amplicons to next-generation sequencing (e.g., Illumina). Tools like UMI-DSBseq can be applied to simultaneously quantify intact molecules, DSB intermediates, and indel products [3].

- Calculate the indel frequency using bioinformatics tools designed for CRISPR analysis (e.g., CRISPResso2).

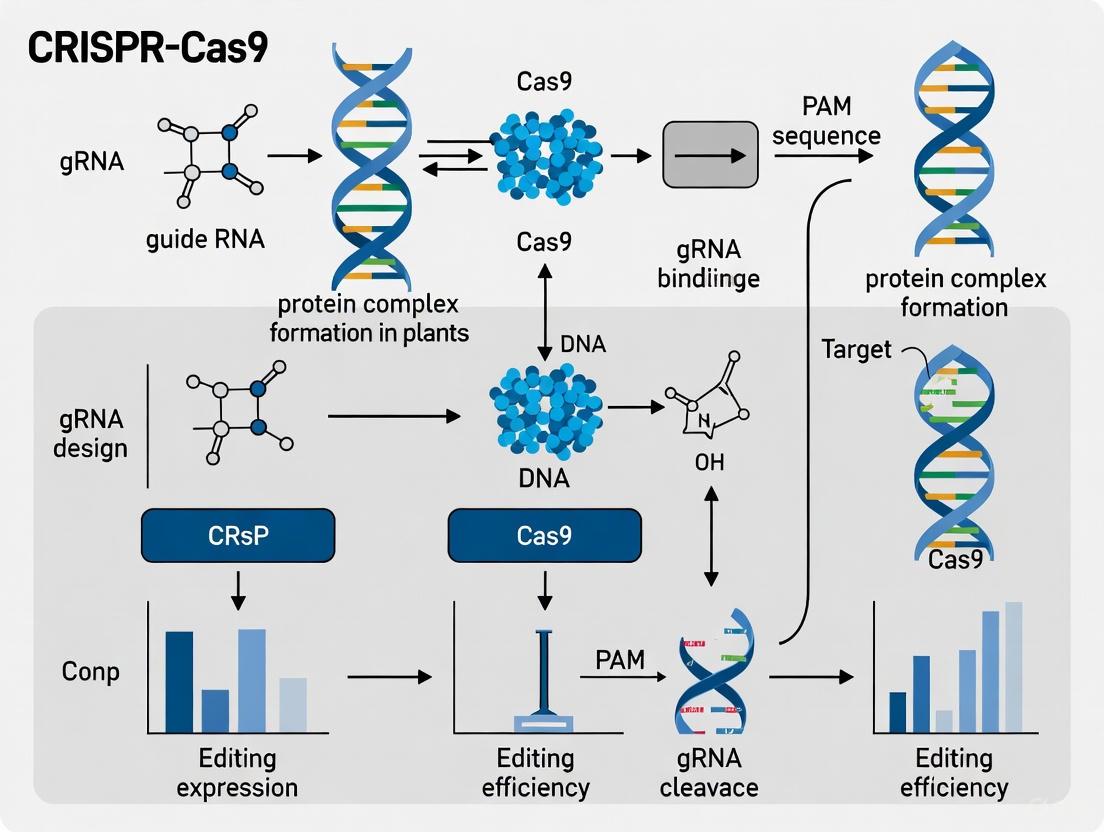

CRISPR-Cas9 Mechanism and Repair Pathway Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete mechanism from sgRNA binding through double-strand break induction and the subsequent cellular repair pathways that determine the editing outcome.

CRISPR-Cas9 Mechanism and Repair Pathways

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments in Plants

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Application Notes for Plant Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | RNA-guided endonuclease that creates DSBs. | SpCas9 is most common. High-fidelity variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1) reduce off-targets. PAM-flexible variants (e.g., SpRY) expand targetable sites [4]. |

| Guide RNA (sgRNA) | Synthetic RNA that directs Cas9 to the target DNA sequence. | Chemically synthesized sgRNA is highly pure and enables DNA-free editing. Design is critical for efficiency and specificity [1]. |

| Endogenous Promoters | Drives expression of Cas9/sgRNA within plant cells. | Using strong, species-specific promoters (e.g., LarPE004 in larch) can significantly boost editing efficiency over constitutive viral promoters like 35S [5]. |

| RNP Complexes | Pre-assembled complexes of Cas9 protein and sgRNA. | Ideal for DNA-free editing via protoplast transformation. Leads to rapid activity and degradation, reducing off-target effects [3] [2]. |

| Protoplast System | Plant cells with cell walls removed. | A versatile platform for rapid testing of CRISPR efficiency and regenerating edited plants in some species [2] [5]. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: My CRISPR-Cas9 experiment in Arabidopsis thaliana shows very low mutation efficiency. I suspect the PAM requirement is a limiting factor. What are my options?

A: Low efficiency due to restrictive PAM requirements is a common issue. The canonical SpCas9 PAM (5'-NGG-3') may not be available at your desired target site. Consider these solutions:

- Alternative Cas Proteins: Use Cas variants with relaxed PAM requirements.

- PAM Engineering: Utilize engineered SpCas9 variants (e.g., SpCas9-NG, xCas9) that recognize broader PAM sequences.

Table: Comparison of Common Cas Proteins and Their PAM Requirements

| Cas Protein | Canonical PAM Sequence | Key Characteristics | Typical Editing Efficiency in Plants* |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | 5'-NGG-3' | Most widely used, high activity | 5-40% (varies by species and tissue) |

| SpCas9-NG | 5'-NG-3' | Relaxed PAM, broader targeting | 1-20% (can be lower than SpCas9) |

| xCas9 | 5'-NG, GAA, GAT-3' | Broad PAM recognition | 2-15% (context-dependent) |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | 5'-TTTV-3' | T-rich PAM, creates sticky ends | 3-30% (often highly efficient in some dicots) |

*Efficiencies are highly variable and depend on gRNA design, delivery method, and plant species. Data is a summary from multiple sources.

Experimental Protocol: Testing Alternative Cas Proteins for Broader PAM Compatibility

- Target Selection: Identify your target genomic region. Use in silico tools to scan for potential PAM sites for SpCas9 and your chosen alternative (e.g., SpCas9-NG).

- gRNA Design: Design 2-3 gRNAs for each Cas protein, ensuring high on-target scores and checking for potential off-targets.

- Vector Construction: Clone each gRNA expression cassette into plant transformation vectors harboring the respective Cas gene (e.g., pCambia-based vectors with a plant-specific promoter like AtU6 for gRNA and 35S for Cas).

- Plant Transformation: Transform your plant material (e.g., Arabidopsis via floral dip, rice via Agrobacterium). Generate at least 20 independent T0 lines per construct.

- Genotyping & Analysis: Extract genomic DNA from T0 seedlings or T1 lines. Amplify the target region by PCR and subject the amplicons to next-generation sequencing (NGS) or a T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) assay to quantify indel mutation frequencies.

Q2: I am observing unexpected phenotypic effects in my edited plants. How can I determine if this is due to gRNA off-target activity?

A: Unintended phenotypic effects are a major concern. To troubleshoot gRNA specificity:

- In Silico Prediction: Use tools like Cas-OFFinder to identify potential off-target sites in the genome that have up to 3-5 mismatches to your gRNA sequence.

- High-Fidelity Cas Variants: Switch to high-fidelity Cas9 proteins like SpCas9-HF1 or eSpCas9(1.1), which are engineered to reduce off-target binding.

- Empirical Validation: Use methods like CIRCLE-seq or Digenome-seq on your plant's genomic DNA to experimentally identify off-target cleavage sites.

Table: Strategies to Enhance gRNA Specificity and Reduce Off-Target Effects

| Strategy | Mechanism | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Truncated gRNAs (tru-gRNAs) | Uses a shorter guide sequence (17-18 nt) to reduce tolerance for mismatches. | Simple to implement, can significantly reduce off-targets. | May also reduce on-target efficiency. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 (e.g., SpCas9-HF1) | Engineered with point mutations to weaken non-specific binding to the DNA backbone. | Highly effective reduction in off-targets with minimal impact on on-target activity. | Requires cloning of a new Cas variant. |

| Ribo ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Delivery | Direct delivery of pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA complexes. Complex degrades quickly, reducing time for off-target cleavage. | Low off-target rates, no vector integration. | Delivery can be challenging in some plant systems. |

| Dual gRNA Nicking | Uses two gRNAs targeting adjacent sites on opposite strands with a Cas9 nickase (Cas9n). A DSB is only formed when two nicks occur in close proximity. | Dramatically increases specificity. | Requires two highly efficient gRNAs in close proximity. |

Experimental Protocol: Off-Target Assessment Using Digenome-seq In Vitro

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Isolate high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from your target plant tissue.

- In Vitro Cleavage: Incubate 1 µg of genomic DNA with the Cas9-gRNA RNP complex (pre-assembled from purified Cas9 protein and synthetically produced gRNA) in a suitable reaction buffer for 4-6 hours.

- DNA Purification: Purify the DNA to remove proteins.

- Whole-Genome Sequencing: Subject the cleaved (test) and untreated (control) DNA to whole-genome sequencing at high coverage (e.g., 30x).

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Map the sequencing reads to the reference genome. Identify sites with a significant increase in read breaks in the test sample compared to the control. These sites represent potential off-target cleavages. Validate top candidate sites by amplicon sequencing in your edited plant lines.

Q3: I am trying to knock in a gene donor template via HDR, but I only get error-prone NHEJ indels. How can I bias the repair toward HDR in plant cells?

A: Favoring the low-efficiency HDR pathway over the dominant NHEJ pathway is a significant challenge in plants. A multi-pronged approach is necessary:

- Synchronize DSB with Cell Cycle: HDR is active in the S/G2 phases. Use cell cycle inhibitors or synchronize your transformation protocol to enrich for cells in these phases.

- Inhibit NHEJ Key Proteins: Use small molecule inhibitors (e.g., KU-0060648 against DNA-PKcs) to transiently suppress the NHEJ pathway during the critical repair window.

- Optimize Donor Template: Use single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) as donors instead of double-stranded DNA. Ensure sufficient homology arms (e.g., 35-50 nt for ssODNs).

Table: Manipulating Cellular Repair Pathways to Enhance HDR

| Approach | Method | Rationale | Example in Plants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Cycle Synchronization | Treatment with aphidicolin (DNA synthesis inhibitor) before transformation. | Enriches cells in S-phase, where HDR is preferred. | Shown to improve HDR efficiency in rice protoplasts. |

| NHEJ Inhibition | Transient expression of dominant-negative mutants of NHEJ factors (e.g., Ku70) or use of small-molecule inhibitors. | Reduces competition from the error-prone NHEJ pathway. | Co-expression of a dominant-negative Ku70 variant increased HDR frequency in Arabidopsis. |

| HDR Enhancement | Overexpression of key HDR proteins (e.g., CtIP, RAD54). | Boosts the capacity of the HDR repair machinery. | Overexpression of AtRAD54 in Arabidopsis was shown to enhance gene targeting. |

Experimental Protocol: Enhancing HDR for Gene Knock-In in Rice Protoplasts

- Protoplast Isolation: Isolate protoplasts from rice callus or etiolated seedlings.

- Synchronization (Optional): Treat protoplasts with 20 µg/mL aphidicolin for 24 hours to arrest cells at the G1/S boundary. Wash out the inhibitor before transfection.

- RNP & Donor Assembly: Pre-assemble RNP complexes with your chosen Cas protein and gRNA. Prepare your ssODN donor template with homologous arms.

- Co-Delivery: Co-transfect the RNP complexes and the ssODN donor into the synchronized protoplasts using PEG-mediated transformation.

- NHEJ Inhibition (Optional): Add a NHEJ inhibitor (e.g., 10 µM NU7026) to the culture medium immediately after transfection and incubate for 24-48 hours.

- Analysis: After 48-72 hours, extract genomic DNA and use a combination of PCR and NGS to detect and quantify precise HDR events versus NHEJ indels.

Visualizations

CRISPR Workflow with Critical Factors

Cellular Repair Pathways After a DSB

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Optimizing CRISPR-Cas9 in Plants

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| SpCas9 & Variant Plasmids | Source of the Cas9 nuclease. High-fidelity variants (e.g., SpCas9-HF1) reduce off-targets, while PAM-relaxed variants (e.g., SpCas9-NG) expand targetable sites. |

| gRNA Cloning Vectors | Vectors (e.g., pU6-gRNA) for easy insertion and expression of the guide RNA sequence under a U6 or U3 pol III promoter. |

| Plant Transformation Vectors | Binary T-DNA vectors (e.g., pCAMBIA series) for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, containing plant selection markers (e.g., Hygromycin resistance). |

| Purified Cas9 Protein | For Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex assembly and direct delivery, reducing off-target effects and avoiding vector integration. |

| Single-Stranded Oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) | Synthetic donor DNA templates for HDR-mediated precise editing, typically with 35-50 nt homology arms. |

| NHEJ Inhibitors (e.g., NU7026) | Small molecule inhibitors of key NHEJ proteins (e.g., DNA-PKcs). Used transiently to favor the HDR repair pathway. |

| T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) | Enzyme for detecting indel mutations via a mismatch cleavage assay. A quick and cost-effective genotyping method. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Kits | For deep amplicon sequencing to accurately quantify editing efficiency and profile the spectrum of mutations at the target site. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Plant CRISPR Challenges

Q1: My CRISPR editing efficiency in plants is low. What are the main plant-specific bottlenecks?

The primary plant-specific bottlenecks for CRISPR editing efficiency are related to transformation, editing efficiency, and the complexity of plant genomes [6]. Key challenges include:

- Transformation Efficiency: The process of delivering CRISPR components into plant cells, often via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, can be inefficient and is highly genotype-dependent [6].

- Plant Cell Walls: The rigid plant cell wall presents a significant physical barrier to the delivery of CRISPR reagents [7].

- Editing Efficiency in Somatic Cells: Even after successful transformation, achieving high editing efficiency in somatic plant cells can be variable, and the resulting tissues are often chimeric [8].

- Polygenic/Polypoid Genomes: Many important crops have complex polyploid genomes (with multiple copies of each chromosome), meaning you need to edit multiple, often redundant, gene copies simultaneously to observe a phenotypic effect [9] [10].

Q2: How can I quickly test gRNA efficiency before stable transformation?

A rapid and simple method is to use a hairy root transformation system mediated by Agrobacterium rhizogenes [8]. This system allows for the visual identification of transgenic roots within two weeks and does not require sterile conditions for some plant species [8]. The protocol involves:

- Making a slant cut on the hypocotyl of young seedlings.

- Infecting the wound with Agrobacterium rhizogenes harboring your CRISPR construct and a visual marker like the Ruby reporter gene [8].

- Cultivating the plants in moist vermiculite for approximately two weeks before sampling the transgenic roots for molecular analysis to assess editing efficiency [8].

Q3: Why do different sgRNAs targeting the same gene show variable performance?

In the CRISPR/Cas9 system, gene editing efficiency is highly influenced by the intrinsic properties of each sgRNA sequence [11]. As a result, different sgRNAs targeting the same gene can exhibit substantial variability in editing efficiency, with some showing little to no activity. To ensure reliable results, it is recommended to design and test at least 3–4 sgRNAs per gene [11].

Q4: How can I efficiently edit multiple genes or gene copies simultaneously?

Multiplex CRISPR editing is the recommended approach for this challenge. It allows for the simultaneous targeting of multiple genes, regulatory elements, or chromosomal regions, making it highly effective for addressing genetic redundancy in polyploid crops or engineering polygenic traits [10]. This can be achieved by expressing multiple gRNAs from a single construct [12] [10].

Troubleshooting Guides & Experimental Protocols

Guide 1: Rapid Evaluation of Somatic Editing Efficiency via Hairy Root Transformation

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 study, provides a fast alternative to stable transformation for testing CRISPR systems and target sites [8].

- Key Applications: Rapid validation of gRNA efficiency; Initial testing of novel CRISPR nucleases (e.g., TnpB); Optimization of protein-engineered editors [8].

Essential Materials:

- Young seedlings (e.g., soybean germinated for 5-7 days).

- Agrobacterium rhizogenes strain (e.g., K599).

- CRISPR binary vector with a visual selection marker (e.g., 35S:Ruby).

- Moist vermiculite.

Methodology:

- Prepare Plant Material: Grow seedlings for 5-7 days.

- Infect: Make a slant cut on the hypocotyl and inoculate with A. rhizogenes.

- Cultivate: Plant the infected seedlings in moist vermiculite. No sterile conditions are needed.

- Identify Transformants: After ~2 weeks, visually identify transgenic roots using the Ruby reporter (appearing red) [8].

- Analyze Editing: Isolate genomic DNA from the hairy roots and use next-generation sequencing (NGS) or other molecular assays to quantify editing efficiency at the target loci [8].

Expected Outcomes:

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps of the hairy root transformation protocol:

Guide 2: Multiplex Editing for Polygenic Traits

This guide outlines strategies for engineering complex traits controlled by multiple genes or in polyploid genomes.

- Key Applications: Gene family functional dissection; Addressing genetic redundancy; De novo domestication; Stacking multiple traits [10].

Experimental Workflow:

- Target Identification: Identify all homologous genes or family members controlling the trait.

- gRNA Design: Design specific gRNAs for each target or conserved gRNAs that can target multiple homologous sequences.

- Vector Assembly: Use modular cloning systems (e.g., Golden Gate assembly) to construct a single binary vector expressing Cas9 and multiple gRNAs [12] [10].

- Plant Transformation & Regeneration: Perform stable transformation and regenerate whole plants.

- Genotyping: Use long-read sequencing technologies to fully characterize complex editing outcomes, including structural rearrangements that standard genotyping might miss [10].

Considerations:

- Analysis: Standard genotyping may miss complex edits. Leverage long-read sequencing for accurate analysis of multiplex edited lines [10].

- Delivery: The delivery of multiplex constructs can be challenging. "All-in-one" CRISPR toolboxes that pre-assemble systems for multiplexing are available to streamline the process [7].

The logical flow for a multiplex editing experiment is outlined below:

The table below summarizes key quantitative data from recent studies on plant genome editing, providing benchmarks for experimental planning.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Data from Plant CRISPR Studies

| Plant Species | Target Gene | Editing System | Efficiency / Outcome | Key Finding / Method | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soybean | GmPDS1, GmPDS2 | CRISPR/Cas9 | Up to 45.1% somatic editing in hairy roots | Hairy root system with Ruby visual marker | [8] |

| East African Highland Banana | Phytoene desaturase (PDS) | CRISPR/Cas9 | 100% & 94.6% albinism in two cultivars | First report in EAHBs; high efficiency in triploid | [12] |

| Various (Rice, Arabidopsis) | OsALS1, AtFT | All-in-one CRISPR Toolbox (Base editing, Activation) | Up to ~11% base editing efficiency; >50-fold gene activation | Validated platform for large-scale screens | [7] |

| ISAam1 TnpB in Soybean | Endogenous loci | ISAam1 TnpB nuclease | 5.1-fold & 4.4-fold increase with engineered variants (N3Y, T296R) | Protein engineering enhanced editing efficiency | [8] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential reagents and tools for conducting plant CRISPR experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Plant CRISPR Experiments

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Visual Reporter Markers | Rapid, non-destructive identification of transgenic tissues without antibiotics. | Ruby reporter [8]; GFP, YFP. |

| Hairy Root Transformation System | Rapid somatic testing of CRISPR efficiency; avoids lengthy stable transformation. | Uses Agrobacterium rhizogenes (e.g., strain K599) [8]. |

| All-in-One CRISPR Toolkits | Pre-assembled, modular vectors for diverse editing applications across plant species. | Vectors for Cas9/Cas12a, base editing, gene activation in monocots/dicots [7]. |

| Modular Cloning Systems | Efficient assembly of complex constructs, especially for multiplexing several gRNAs. | Golden Gate assembly [12]. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes | Direct delivery of pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA complexes; can reduce off-target effects and generate transgene-free plants. | Promising for species with low transformation efficiency [6]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: General Nuclease Selection

Q: For a beginner starting with plant genome editing, which nuclease is recommended: SpCas9 or Cas12a? A: For beginners, SpCas9 is often recommended due to the vast amount of existing protocols, validated guide RNA designs, and commercial reagents. However, if your target site is rich in thymine (T) and you require multiplexed editing, Cas12a is the superior choice.

Q: What are the primary advantages of Cas12a over Cas9 for plant research? A: Cas12a offers several key advantages:

- Simpler crRNA: It requires a shorter, single crRNA without a tracrRNA, simplifying synthesis.

- T-Rich PAM: Its TTTV PAM allows targeting of AT-rich genomic regions inaccessible to SpCas9.

- Staggered Cuts: It creates staggered ends, which can be beneficial for certain DNA repair outcomes.

- Multiplexing: Its native RNase activity allows processing of a single transcript for multiple crRNAs.

Q: My plant transformation efficiency is low. Could my choice of nuclease be a factor? A: Yes. The large size of SpCas9 (~4.2 kb) can be a limiting factor for delivery via certain vectors (e.g., some viral vectors). Smaller nucleases like SaCas9 (~3.3 kb) or Cas12f (~0.4-0.7 kb) are better suited for size-constrained delivery systems, potentially improving transformation rates.

Troubleshooting Guide: Low Editing Efficiency

Issue: No mutations detected in transformed plant lines.

- Cause 1: Inefficient gRNA/crRNA design.

- Solution: Verify that your gRNA has high on-target activity scores using multiple prediction tools (e.g., Chop-Chop, CRISPR-P). Avoid sequences with high homology to off-target sites. For Cas12a, ensure the direct repeat sequence is correct.

- Cause 2: Low nuclease expression.

- Solution: Use a plant-specific promoter with strong expression in your target tissue (e.g., Ubiquitin for monocots, 35S for dicots). Confirm expression via RT-PCR or a fluorescent marker.

- Cause 3: Inaccessible chromatin state at the target locus.

- Solution: Consult epigenomic data (e.g., DNAse I hypersensitivity sites, histone modification marks) for your plant species to select an open chromatin region. Re-design gRNAs to target these regions.

Issue: High off-target activity observed.

- Cause 1: gRNA/crRNA has high sequence similarity to other genomic loci.

- Solution: Perform a thorough genome-wide off-target prediction. Re-design the gRNA to have at least 3 mismatches to any other site in the genome. Consider using high-fidelity variants like SpCas9-HF1 or eSpCas9(1.1).

- Cause 2: Nuclease is expressed at very high levels for a prolonged period.

- Solution: Use a self-limiting system such as a riboswitch or a transient expression system (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex delivery via biolistics or protoplast transfection).

Issue: Successful editing but poor regeneration of edited plants.

- Cause: Somatic cell toxicity from persistent nuclease activity.

- Solution: Employ a transient expression system. Delivery of pre-assembled RNP complexes is highly effective as the nuclease degrades naturally, minimizing prolonged activity. Alternatively, use regeneration-promoting growth hormones in your tissue culture media.

Quantitative Nuclease Comparison

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of major CRISPR nucleases relevant to plant genome editing.

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR Nucleases for Plant Research

| Feature | Cas9 (SpCas9) | Cas12a (LbCas12a, AsCas12a) | Cas12f (Cas14, Un1Cas12f1) | Cas9-NG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (aa) | ~1,368 | ~1,300 | ~400-700 | ~1,368 |

| PAM Sequence | 5'-NGG-3' | 5'-TTTV-3' | 5'-TTN-3' (varies) | 5'-NG-3' |

| Cleavage Type | Blunt ends | Staggered ends (5' overhang) | Blunt ends | Blunt ends |

| Guide RNA | crRNA + tracrRNA (or sgRNA) | Single crRNA | Single crRNA | crRNA + tracrRNA (or sgRNA) |

| Multiplexing | Requires multiple sgRNAs | Native processing of array | Limited data | Requires multiple sgRNAs |

| Key Advantage | Extensive validation, high efficiency | T-rich PAM, simpler RNA | Ultra-small for delivery | Relaxed PAM (NG) |

| Key Disadvantage | Large size, G-rich PAM | Lower efficiency in some plants | Lower cleavage efficiency | Can reduce on-target efficiency |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Agrobacterium-mediated Transformation of Arabidopsis with CRISPR-SpCas9

Objective: To stably integrate a CRISPR-SpCas9 T-DNA construct into the Arabidopsis genome for heritable gene editing.

Materials:

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101

- Arabidopsis thaliana (ecotype Col-0) plants

- CRISPR-SpCas9 binary vector (e.g., pHEE401E)

- Infiltration Media (IM): 1/2x Murashige and Skoog (MS) salts, 5% (w/v) sucrose, 0.044 μM benzylaminopurine, 200 μl/L Silwet L-77

Method:

- Plant Growth: Grow Arabidopsis plants under long-day conditions (16-h light/8-h dark) until the primary inflorescence is ~5-10 cm tall. Clip the primary bolt to encourage secondary bolt growth.

- Agrobacterium Preparation: Transform the CRISPR binary vector into Agrobacterium. Grow a 50-ml culture in YEP medium with appropriate antibiotics to an OD600 of ~1.5. Pellet cells and resuspend in IM to a final OD600 of 0.8.

- Floral Dip: Subvert the above-ground parts of the Arabidopsis plants into the Agrobacterium suspension for 30 seconds, ensuring all floral tissues are submerged. Gently agitate.

- Post-Dip Care: Lay the dipped plants on their side and cover with a transparent dome or plastic wrap to maintain high humidity for 16-24 hours.

- Seed Harvest: Grow plants until seeds are mature and dry. Harvest seeds (T1 generation).

Protocol 2: Delivery of CRISPR-Cas12a as Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes into Plant Protoplasts

Objective: To achieve transient, high-efficiency gene editing with minimal off-target effects using pre-assembled Cas12a RNP complexes.

Materials:

- Plant protoplasts isolated from desired species (e.g., Nicotiana benthamiana)

- Purified LbCas12a protein

- Chemically synthesized crRNA

- PEG-Calcium solution (40% PEG 4000, 0.2 M mannitol, 0.1 M CaCl2)

- W5 solution (154 mM NaCl, 125 mM CaCl2, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MES, pH 5.7)

Method:

- RNP Complex Assembly: For a 20μl reaction, mix 5 μg (~3 pmol) of LbCas12a protein with a 5x molar excess of crRNA (15 pmol) in nuclease-free buffer. Incubate at 25°C for 15 minutes to form the RNP complex.

- Protoplast Preparation: Isolate protoplasts and resuspend in W5 solution at a density of 1-2 x 10^6 protoplasts/ml. Keep on ice for 30 minutes.

- Transfection: Aliquot 100μl of protoplast suspension (10^5 cells) into a round-bottom tube. Add the pre-assembled 20μl RNP complex. Gently add 120μl of PEG-Calcium solution and mix carefully by inverting the tube.

- Incubation: Incubate the transfection mixture at room temperature for 15-20 minutes.

- Washing and Culture: Dilute the mixture with 1 ml of protoplast culture medium. Centrifuge gently (100 x g, 2 min) to pellet the protoplasts. Remove the supernatant and resuspend the protoplasts in fresh culture medium. Culture in the dark at 25°C for 48-72 hours before harvesting DNA for analysis.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

CRISPR RNP Delivery Workflow

Title: RNP Delivery into Protoplasts

CRISPR Experiment Lifecycle

Title: CRISPR Plant Experiment Steps

DNA Repair Pathway Decision

Title: DNA Repair After CRISPR Cut

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Plant Research

| Reagent | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nuclease | The enzyme that cuts the DNA. | SpCas9, LbCas12a. Choose based on PAM requirement and size. |

| Binary Vector | A T-DNA plasmid for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. | pBIN19, pCAMBIA series. Contains plant selection marker (e.g., Kanamycin resistance). |

| Plant Codon-Optimized Cas | A version of the Cas gene optimized for expression in plants. | Critical for high translation efficiency. |

| gRNA Expression Scaffold | The part of the sgRNA that binds to the Cas protein. | Often driven by a U6 or U3 pol III promoter. |

| Plant Selection Agent | A chemical to select for transformed tissue. | Kanamycin, Hygromycin B, Glufosinate ammonium (Basta). |

| Protoplast Isolation Enzymes | A mix of cellulases and pectinases to digest plant cell walls. | e.g., Cellulase R10, Macerozyme R10. |

| PEG Solution | A polymer used to induce membrane fusion for transfection. | Used for protoplast transfection of DNA or RNP complexes. |

| Donor DNA Template | A repair template for HDR-mediated knock-in. | Can be single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) or double-stranded DNA. |

Advanced Strategies for Optimizing Reagents and Delivery Methods

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: What are the key trade-offs when using PAM-flexible Cas9 variants, and how do I select the right one for my plant experiment?

A: PAM flexibility often comes at the cost of reduced on-target activity. When selecting a variant, consider your specific need for precise positioning versus the required editing efficiency [13].

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of several engineered Cas9 variants based on comparative studies:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of PAM-Flexible Cas9 Variants

| Cas9 Variant | PAM Preference | Relative On-Target Efficiency (vs. WT Cas9) | Key Characteristics | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT SpCas9 | NGG [13] | Baseline (100%) | Standard editing efficiency, broad use [14] | Standard editing where NGG PAMs are available |

| Cas9-NG | NG [13] | ~64% of WT at NGG sites [13] | Outperforms xCas9 at NG PAMs regardless of modality [13] | Applications requiring relaxed NG PAM recognition |

| xCas9 | NG [13] | ~43% of WT at NGG sites [13] | Lower activity than Cas9-NG and WT Cas9 [13] | Less recommended compared to newer variants |

| SpRY | NRN > NYN (near-PAMless) [15] | Broad editing but with slower cleavage rates than WT [15] | Unprecedented genomic accessibility, can be less accurate [15] | Projects requiring maximal target site flexibility |

| SpRYc (Chimeric) | NRN and NYN (highly flexible) [15] | Robust editing at diverse PAMs, including NYN [15] | Combines SpRY's PID with Sc++'s N-terminus; lower off-targets than SpRY [15] | Therapeutic applications and editing requiring precise positioning |

Q2: I am experiencing low mutation efficiency in my wheat transformation. What experimental parameters can I optimize?

A: Low mutation efficiency, especially in complex polyploid plants like wheat, is a common challenge. You can optimize several aspects of your protocol:

- Gene Delivery Parameters (for Biolistics): A study in hexaploid wheat found that using 0.6 μm gold particles for bombardment increased stable transformation frequencies across all delivery pressures compared to other sizes [16].

- Post-Transformation Temperature Treatment: Subjecting transformed wheat embryos to a heat treatment of 34°C for 24 hours resulted in the highest mutation efficiency with minimal reduction in transformation frequency. This is likely because the Cas9 enzyme from S. pyogenes is more active at higher temperatures [16].

- Component Optimization: Ensure you are using promoters that drive high expression of Cas9 and sgRNAs in your plant species. Furthermore, always test sgRNA efficiency in vivo before stable transformation to maximize success [16].

Q3: How can I reduce off-target effects in my CRISPR experiments?

A: Several strategies can help minimize off-target activity:

- Choose High-Fidelity Variants: Consider using enzymes that are intrinsically more accurate. For example, the chimeric SpRYc variant was shown to have nearly a four-fold lower off-target activity than SpRY in human cells [15].

- Use a Nickase System: The double nickase ("double nick") system uses a pair of guide RNAs with a Cas9 nickase (Cas9n, D10A mutant) to create two single-strand breaks on opposite strands. This strategy significantly reduces off-target effects because off-target sites are unlikely to be cut by both guides simultaneously [17].

- Optimize Delivery Conditions: Avoid using excessively high concentrations of Cas9 and sgRNA, as this can increase the likelihood of off-target cleavage [17]. Delivering pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes can also shorten the exposure time of the genome to the editing machinery, potentially reducing off-target effects [16].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Bacterial Screen for Assessing PAM Specificity

This protocol adapts the PAM-SCANR method to characterize the PAM preference of a novel Cas9 variant [15].

- Clone your Cas9 variant: Subclone your gene of interest for the nuclease-deficient (dCas9) version into an appropriate bacterial expression vector.

- Prepare the PAM library: Transform the PAM-SCANR plasmid, which contains a randomized PAM library, into your bacterial strain.

- Co-transform with targeting components: Co-transform the bacteria with a plasmid containing a single guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting a fixed protospacer on the PAM-SCANR plasmid and the dCas9 plasmid.

- Select and sequence: Isolate successful cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) based on GFP expression, which is conditional on PAM binding and successful complex formation. Amplify and sequence the PAM region from the sorted population to determine the enriched PAM sequences [15].

Diagram: Workflow for PAM Characterization

Protocol 2: Assessing Mutation Efficiency via a Phenotypic Assay in Wheat Using the PDS Gene

This protocol uses the knockout of the Phytoene Desaturase (PDS) gene, which results in a visible albino phenotype, to quickly assess mutation efficiency [16].

- Construct Design: Clone your sgRNA expression cassette targeting the wheat PDS gene into a CRISPR-Cas9 vector. A strong, constitutive promoter like the rice Actin1 promoter is often effective [16].

- Plant Transformation: Transform the construct into wheat immature embryos (IEs) using your preferred method, such as particle bombardment.

- Temperature Treatment: After bombardment, subject the transformed embryos to a heat treatment of 34°C for 24 hours to enhance Cas9 activity [16].

- Regeneration and Selection: Regard the embryos on selective medium and regenerate whole plants under standard growth conditions.

- Efficiency Scoring: Score the mutation efficiency by tracking the number of independent transformation events that show an albino phenotype. In hexaploid wheat, this requires biallelic mutations in all three homoeologs (A, B, and D genomes), providing a stringent test of your system's efficiency [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Cas Protein Engineering and Testing

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Vectors | Provides the platform for expressing wild-type or engineered Cas9 variants. | lentiCRISPRv2 backbone [13]; plasmids for nickase (PX335) and WT nuclease (PX330) [17]. |

| sgRNA Cloning Backbones | Allows for the insertion of custom guide RNA sequences. | Vectors with human U6 promoter (e.g., PX330); add 'CACC' overhang to forward oligo, no PAM sequence needed [17]. |

| PAM Library Plasmids | For high-throughput characterization of a Cas protein's PAM preference. | PAM-SCANR [15] or HT-PAMDA [15] systems. |

| Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Donor Templates | For introducing precise point mutations or inserting DNA fragments. | ssODN: For small changes (<50 bp), use 50-80 bp homology arms. Plasmid Donor: For large insertions, use ~800 bp homology arms [17]. |

| Model Plant Genes for Efficiency Testing | Provides a rapid, phenotypically visible readout for editing efficiency. | Phytoene Desaturase (PDS): Knockout causes albino phenotype [16]. |

Diagram: Logical Relationship of CRISPR Component Engineering

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: What are the most critical factors to consider when designing a gRNA for plant research?

The primary factors are on-target efficiency and off-target risk [18]. Key design parameters include:

- PAM Sequence: The Cas nuclease you use defines the PAM sequence requirement. For the commonly used SpCas9, this is 5'-NGG-3' located directly after the target sequence in the genome [19] [1].

- GC Content: Aim for a GC content between 40% and 60% for optimal stability and efficiency [20] [18] [1].

- gRNA Length: A typical gRNA for SpCas9 is 17-23 nucleotides. Truncated gRNAs can sometimes improve specificity [20] [1].

- Off-Target Potential: Select a gRNA sequence that is unique within the genome to minimize binding to similar, incorrect sites [20] [18].

Q2: How can I quickly and reliably predict the efficiency of my designed gRNAs?

Leverage established computational tools that use algorithms trained on large experimental datasets. The table below summarizes the most prominent tools and their scoring methods.

Table 1: Computational Tools for gRNA On-Target Efficiency Prediction

| Tool Name | Key Scoring Method(s) | Application & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPick [18] | Rule Set 2, Rule Set 3, CFD | Uses updated models (Rule Set 3) that consider the tracrRNA sequence for improved predictions. |

| CHOPCHOP [18] | Rule Set, CRISPRscan | A versatile tool that supports various CRISPR-Cas systems beyond Cas9. |

| CRISPOR [18] | Rule Set 2, CRISPRscan, Lindel | Provides detailed off-target analysis and predicts frameshift likelihood using the Lindel algorithm. |

| GenScript sgRNA Design Tool [18] | Rule Set 3, CFD | Offers an overall score balancing on-target and off-target metrics, with support for SpCas9 and Cas12a. |

Q3: My CRISPR edits are inefficient. What are the main experimental reasons, and how can I troubleshoot this?

Low editing efficiency can stem from several factors. The following workflow diagram outlines a logical troubleshooting path, from gRNA design verification to delivery optimization.

- gRNA Design: Verify that your gRNA has a high predicted on-target score using the tools in Table 1. Avoid very low or very high GC content [18] [1].

- gRNA Quality and Delivery: The method of gRNA production impacts efficiency. Synthetic sgRNA is often preferred over in vitro transcribed (IVT) or plasmid-expressed gRNA due to higher purity, lower immunogenicity, and reduced off-target effects [21] [1]. Ensure your delivery method (e.g., protoplast transformation, Agrobacterium-mediated) is optimized for your plant species [12] [22].

- Target Site Accessibility: Chromatin structure can make some genomic regions inaccessible [19]. It is highly advisable to design and test multiple gRNAs targeting different exons of your gene of interest [23] [1].

- Cas9 Activity: Always include a positive control gRNA (e.g., targeting a well-characterized gene like Phytoene Desaturase (PDS), which produces an easily observable albino phenotype in plants) to confirm your overall system is functional [12].

Q4: What specific strategies can I use to minimize off-target effects in my plant experiments?

Reducing off-target activity is crucial for precise editing. The table below summarizes effective strategies, ranging from gRNA selection to the use of advanced systems.

Table 2: Strategies for Minimizing Off-Target Effects

| Strategy | Method | Key Principle |

|---|---|---|

| gRNA Engineering | Careful sequence selection; Truncated gRNAs; Chemical modifications (e.g., 2'-O-methyl-3'-phosphonoacetate) [20] [21]. | Select unique target sequences with minimal genomic homology. Chemical modifications can enhance stability and specificity. |

| High-Fidelity Cas Variants | Use eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1 [20] [21]. | Engineered proteins with reduced non-specific DNA binding, requiring more perfect matches for cleavage. |

| Cas9 Nickase | Use Cas9n (D10A mutant) with a pair of offset gRNAs [20]. | Cuts only a single DNA strand. Two nearby nicks are required for a double-strand break, dramatically increasing specificity. |

| Alternative Cas Enzymes | Use SaCas9 or Cas12a (Cpf1) [20] [24]. | These nucleases have longer, rarer PAM sequences (e.g., SaCas9: 5'-NNGRRT-3'), reducing the number of potential off-target sites in the genome. |

| Prime Editing | Use a Cas9 nickase fused to a reverse transcriptase and a prime editing guide RNA (PegRNA) [20]. | Enables precise edits without creating double-strand breaks, thereby eliminating a major cause of off-target indels. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Delivery | Deliver pre-assembled complexes of Cas9 protein and gRNA [25]. | The transient activity of RNPs reduces the time window for off-target cleavage to occur, compared to persistent plasmid-based expression. |

Experimental Protocol: Rapid gRNA Validation in Plants Using Protoplast Transformation

This protocol, adapted from Higa et al. (2024), allows for rapid in vivo testing of gRNA activity in days, bypassing the lengthy process of stable plant transformation [22].

1. Principle: Isolate protoplasts (plant cells without cell walls) from target species and transfert them with CRISPR-Cas9 constructs or Ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) to assess editing efficiency at the target locus before embarking on a full stable transformation experiment.

2. Reagents and Materials: Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Protoplast Assays

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Plant Material | Source of protoplasts. | Etiolated seedlings of species like maize, Arabidopsis, or tobacco [22]. |

| Enzyme Solution | Digests cell wall to release protoplasts. | Contains cellulases and pectinases. Osmolarity must be adjusted with mannitol. |

| PEG Solution | Facilitates DNA/RNP uptake into protoplasts. | Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) is a common transfection agent [22]. |

| CRISPR Components | Active editing machinery. | Plasmid DNA encoding Cas9 and gRNA, or pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA RNP complexes. |

| WI Solution | Washing and incubation solution to maintain protoplast viability. |

3. Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Protoplast Isolation: Harvest tender leaf tissue from etiolated seedlings. Slice leaves thinly and incubate in an enzyme solution for several hours in the dark with gentle shaking.

- Purification: Filter the digested mixture through a mesh to remove debris. Pellet the protoplasts by gentle centrifugation and wash with WI solution.

- Transfection: Incubate protoplasts with your CRISPR-Cas9 construct (typically 10 µg plasmid DNA) or RNP complexes in the presence of PEG to induce uptake [22].

- Incubation and Analysis: Incubate transfected protoplasts for up to 7 days, allowing time for genome editing to occur. Harvest cells and extract genomic DNA.

- Efficiency Assessment: Use targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) or a restriction enzyme-based assay (e.g., GeneArt Genomic Cleavage Detection Kit) to quantify indel mutation frequencies at the target site [22] [23].

4. Troubleshooting:

- Low Protoplast Yield/Viability: Optimize enzyme concentration and digestion time. Use etiolated tissue and ensure solutions have correct osmolarity [22].

- Low Transfection Efficiency: Titrate the amount of DNA/RNP and optimize PEG concentration and incubation time.

- Low Detected Editing: Ensure protoplasts are viable for a sufficient period post-transfection (e.g., 3-7 days) for the editing to be completed and detectable [22]. Test multiple gRNAs as their efficiency can vary significantly.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation (T-DNA Delivery)

Q1: My Agrobacterium transformation efficiency is very low in my plant species. What could be the cause? A: Low efficiency can stem from several factors. The primary issue is often plant genotype and tissue vitality. Ensure you are using an optimal explant (e.g., young, healthy leaf discs or embryogenic callus) and that your virulence (vir) gene induction conditions are correct (e.g., correct pH, temperature, and presence of acetosyringone). Bacterial overgrowth can also be detrimental; control co-cultivation time (typically 2-3 days) and use appropriate antibiotics.

Q2: I suspect T-DNA is not being transferred efficiently. How can I troubleshoot this? A: First, confirm the functionality of your binary vector and Agrobacterium strain using a transient GUS or GFP assay. If expression is weak, optimize the co-cultivation medium (sucrose level, pH, and acetosyringone concentration). Genomic DNA extraction and PCR on the transformed tissue can confirm T-DNA integration, but the absence of editing may be due to poor Cas9/gRNA expression post-integration.

Q3: How can I reduce somaclonal variation and chimerism in my regenerated plants? A: Somaclonal variation increases with prolonged time in culture. To minimize this, use the shortest possible selection and regeneration protocol. To reduce chimerism, include a stringent selection regime and perform multiple rounds of regeneration (sub-culturing) to ensure all cells carry the edit. Always analyze subsequent generations (T1, T2) to identify stable, non-chimeric lines.

Biolistic (Gene Gun) Transformation

Q4: I am experiencing high cell death after particle bombardment. What should I adjust? A: High cell death is often due to physical damage from the bombardment parameters.

- Pressure/Helium: Reduce the rupture disk pressure.

- Distance: Increase the distance between the stopping screen and the target tissue.

- Particle Preparation: Ensure gold particles are clean and not aggregated. Avoid over-coating with DNA, as the excess spermidine and calcium can be toxic.

- Tissue State: Use physiologically robust target tissues like compact embryogenic calli.

Q5: My transformation yields many escapes (non-transformed plants that survive selection). How do I fix this? A: Escapes are common in biolistics due to transient expression and non-integrated DNA.

- Selection: Optimize the concentration and timing of the selection agent (e.g., hygromycin, kanamycin). A delayed application of selection (e.g., 5-7 days post-bombardment) can allow transformed cells to recover and proliferate before being challenged.

- Vector Design: Use a vector with a strong, constitutive promoter driving the selectable marker gene.

Q6: I get complex transgene integration patterns. How can I achieve simpler integration? A: Biolistics is prone to generating multi-copy and complex rearrangements. While difficult to prevent entirely, using linear DNA fragments instead of whole plasmids and minimizing the amount of DNA used per shot can reduce complexity.

DNA-Free RNP Transfection

Q7: The delivery of RNPs into plant cells is inefficient. What are my options? A: RNP delivery is the major challenge. The two primary methods are:

- PEG-Mediated Transfection: Effective for protoplasts. The key is using fresh, highly viable protoplasts and optimizing PEG concentration and incubation time.

- Biolistics with RNPs: Coat gold particles with pre-assembled RNPs instead of DNA. This requires optimizing the coating protocol (e.g., avoiding high salts that cause aggregation) and bombardment parameters to deliver the particles directly into the cell nucleus while maintaining protein function.

Q8: I get successful mutagenesis but no stable regenerated plants from protoplasts. A: Regeneration from protoplasts is highly genotype-dependent and challenging. Focus on plant species with established protoplast regeneration protocols (e.g., lettuce, tobacco, some rice varieties). Ensure your culture media and environmental conditions (light, temperature) are optimal for cell wall reformation and subsequent callus formation and organogenesis.

Q9: How do I confirm that my edits are DNA-free and not due to plasmid integration? A: Sequence the edit site in the regenerated plant. The absence of the plasmid sequence can be confirmed by PCR using primers specific to the plasmid backbone (e.g., the bacterial origin of replication or antibiotic resistance gene). Molecular analysis of the T1 progeny is the ultimate test; the segregation of the edited allele in a Mendelian ratio without the presence of the transgene confirms a DNA-free edit.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery Methods

| Feature | Agrobacterium | Biolistics | DNA-Free RNP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Editing Efficiency | 1-10% (stable) | 0.1-5% (stable) | 0.1-40% (transient, protoplast-dependent) |

| Transgene Integration | Yes, defined T-DNA borders | Yes, often complex & multi-copy | No |

| Off-Target Effects | Moderate (prolonged expression) | Moderate (prolonged expression) | Low (short-lived activity) |

| Regulated as GMO? | Yes | Yes | Often No (in many countries) |

| Technical Complexity | Medium | High | High (Protoplast: Very High) |

| Throughput | High | Medium | Low (Protoplast: Low) |

| Best for | Stable transformation, large DNA inserts | Species recalcitrant to Agrobacterium | Non-GMO products, rapid mutagenesis |

Table 2: Common Reagents and Their Functions in Delivery Protocols

| Reagent / Material | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Acetosyringone | A phenolic compound that induces the Agrobacterium Vir genes, enabling T-DNA transfer. |

| Gold / Tungsten Microparticles | Micro-projectiles used in biolistics to physically carry DNA or RNPs into cells. |

| Spermidine (in Biolistics) | A polyamine used in the precipitation of DNA onto gold particles, preventing aggregation. |

| Calcium Chloride (in Biolistics) | Works with spermidine to co-precipitate DNA onto the surface of gold particles. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A chemical that facilitates the fusion of cell membranes, used for transfection of RNPs into protoplasts. |

| Cellulase & Pectolyase Enzymes | Used to digest plant cell walls to create protoplasts for RNP or DNA transfection. |

| Antibiotics (e.g., Timentin) | Used in plant culture media to eliminate residual Agrobacterium after co-cultivation. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation of Leaf Discs

- Vector Design: Clone your gRNA(s) into a binary vector containing Cas9 and a plant selectable marker.

- Agrobacterium Preparation: Transform the binary vector into a disarmed Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain (e.g., EHA105, GV3101). Grow a fresh culture in liquid medium with appropriate antibiotics to an OD₆₀₀ of ~0.5-0.8.

- Induction: Pellet bacteria and resuspend in liquid plant co-cultivation medium supplemented with 100-200 µM acetosyringone. Induce for 1-2 hours.

- Plant Material: Surface sterilize leaves and cut into small discs (5x5 mm).

- Co-cultivation: Immerse leaf discs in the induced Agrobacterium suspension for 5-30 minutes. Blot dry and place on solid co-cultivation medium in the dark for 2-3 days.

- Selection & Regeneration: Transfer explants to selection medium containing antibiotics to kill Agrobacterium (e.g., Timentin) and to select for transformed plant cells (e.g., Kanamycin). Sub-culture every 2 weeks until shoots regenerate.

- Rooting & Acclimatization: Excise shoots and transfer to rooting medium. Once rooted, transfer plants to soil.

Protocol 2: RNP Transfection into Protoplasts using PEG

- Protoplast Isolation: Digest 1g of young leaf tissue in an enzyme solution (e.g., 1.5% Cellulase, 0.4% Macerozyme) for 4-16 hours in the dark with gentle shaking.

- Purification: Filter the digest through a nylon mesh (40-100 µm) to remove debris. Pellet protoplasts by centrifugation in a W5 solution. Purify by flotation on a sucrose or Percoll gradient.

- RNP Complex Formation: Assemble the RNP complex by incubating purified Cas9 protein (e.g., 10 µg) with synthesized gRNA (e.g., 5 µg) at room temperature for 10-15 minutes.

- PEG Transfection: Mix ~100,000 protoplasts with the RNP complex. Add an equal volume of 40% PEG solution (PEG 4000, 0.2M mannitol, 0.1M CaCl₂). Incubate for 10-30 minutes.

- Washing & Culture: Dilute the PEG mixture stepwise with W5 solution. Pellet the protoplasts and resuspend in culture medium.

- Analysis: Culture protoplasts for 48-72 hours, then extract DNA to assay editing efficiency (e.g., by T7E1 assay or sequencing).

Methodology and Workflow Diagrams

CRISPR Delivery Method Selection

Intracellular CRISPR Delivery Paths

Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) and Codon Optimization as Determinants of Enhanced Efficiency

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is a Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) and why is it critical for CRISPR-Cas9 efficiency? A Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) is a short amino acid sequence that 'tags' a protein for import into the cell nucleus by nuclear transport. It is typically composed of one or more short sequences of positively charged lysines or arginines exposed on the protein surface [26]. For CRISPR-Cas9, attaching an NLS to the Cas9 protein is essential because it ensures efficient delivery of the genome-editing machinery into the nucleus, where its DNA target is located. Inadequate nuclear import due to a suboptimal NLS is a common cause of low editing efficiency [27] [28].

2. How does codon optimization enhance protein expression in heterologous systems? Codon optimization is a gene design strategy that uses synonymous codon changes to improve the production of a recombinant protein without altering the amino acid sequence [29]. Specific species have a biased preference for certain codons, and this "codon usage bias" is positively correlated with the abundance of corresponding tRNAs in the cell [30]. By optimizing the codon sequence of a gene (e.g., Cas9) to match the preferred codon usage of the host organism (e.g., a plant species), the rate and accuracy of translation are significantly improved, leading to higher levels of functional protein and, consequently, higher genome-editing efficiency [30] [29].

3. What are the common types of NLS used in CRISPR-Cas9 systems? The two primary classes of NLSs are Classical (cNLS) and Non-classical (ncNLS) [26] [31].

- Classical NLS (cNLS): These are further divided into:

- Non-classical NLS (ncNLS): This category includes diverse signals, such as the proline-tyrosine (PY)-NLS, which is recognized by specific import receptors like importin-β2 (transportin) [26].

Table 1: Common Nuclear Localization Signals (NLSs)

| NLS Type | Key Characteristics | Example Sequence | Primary Import Receptor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monopartite (Classical) | Single cluster of 4-8 basic residues; Consensus K(K/R)X(K/R) [31] |

SV40 Large T-antigen: PKKKRKV [26] |

Importin α/β [26] |

| Bipartite (Classical) | Two basic clusters separated by a 10-12 aa linker; Consensus R/K(X)₁₀₋₁₂KRXK [31] |

Nucleoplasmin: KRPAATKKAGQAKKKK [26] |

Importin α/β [26] |

| PY-NLS (Non-classical) | N-terminal hydrophobic/basic motif and C-terminal R/K/H(X)₂₋₅PY motif [26] |

hnRNP A1: FGNYNNQSSNFGPMKGGNFGGRSSGPY [31] |

Importin-β2 (Transportin) [26] |

4. My CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency is low. What are the primary troubleshooting steps? Low editing efficiency can stem from multiple factors. A systematic troubleshooting approach should focus on:

- sgRNA Design: Ensure your single-guide RNA (sgRNA) is highly specific and has high on-target activity. Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., CRISPR Design Tool, Benchling) to minimize off-target effects [27] [32].

- Delivery Efficiency: Optimize your method for delivering CRISPR components (Cas9 and sgRNA) into plant cells. Test different transfection or transformation protocols [27].

- Cas9 and NLS Performance: Verify that the Cas9 protein is being robustly expressed and efficiently imported into the nucleus. Using a stably expressing, codon-optimized Cas9 with a strong NLS can dramatically improve results [27] [28].

- Component Validation: Always include positive and negative controls in your experiments to benchmark system performance and identify background activity [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Knockout Efficiency

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Suboptimal sgRNA Design

- Cause: Inefficient Nuclear Import of Cas9

- Solution: Fuse a validated, strong NLS to your Cas9 protein. The SV40 NLS is widely used, but testing alternative NLSs (e.g., bipartite or c-Myc NLS) may yield better results, as some studies show significantly higher efficiency with c-Myc NLS compared to SV40 [26] [27]. Ensure the NLS is positioned at an accessible location on the protein (often at the N- or C-terminus).

- Cause: Low Expression of Cas9 Protein

Issue 2: High Off-Target Effects

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: sgRNA with High Sequence Similarity to Multiple Genomic Loci

- Solution: Perform a comprehensive BLAST search against the host genome to ensure the sgRNA sequence is unique, especially critical in polyploid crops like wheat with high sequence redundancy [32].

- Cause: High and Prolonged Cas9 Nuclease Activity

- Solution: Consider using high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) engineered to reduce off-target cleavage while maintaining on-target activity [28].

Issue 3: Cell Toxicity or Low Survival Rates

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Overexpression of CRISPR-Cas9 Components

- Solution: Titrate the concentration of delivered Cas9 and sgRNA. Start with lower doses and gradually increase to find a balance between editing efficiency and cell viability [28]. Using a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex (pre-assembled Cas9 protein and sgRNA) instead of plasmid DNA can reduce toxicity and off-target effects.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating NLS Functionality

Objective: To confirm that a chosen NLS is capable of directing a protein of interest to the nucleus.

Materials:

- Plasmid encoding a fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP)

- DNA fragment encoding your NLS of interest

- Molecular cloning reagents

- Plant protoplast transformation system or microscope

Method:

- Construct Fusion: Clone the DNA sequence encoding the NLS in-frame with the gene for Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP). A common approach is to fuse the NLS to either the N- or C-terminus of GFP.

- Deliver Construct: Introduce the constructed plasmid into your target plant cells, for example, using polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated transformation of protoplasts.

- Visualize Localization: After an appropriate incubation period (e.g., 24-48 hours), observe the cells under a confocal microscope.

- Interpret Results:

- Positive Result: Fluorescence is predominantly observed within the nucleus.

- Negative Result: Fluorescence is diffused throughout the entire cell (cytoplasm and nucleus), indicating the NLS is non-functional or inaccessible.

Protocol 2: Implementing Codon Optimization for Cas9

Objective: To increase the expression level of the Cas9 protein in a target plant host.

Materials:

- Amino acid sequence of the source Cas9 protein (e.g., from S. pyogenes)

- Codon optimization software or service (e.g., using deep learning models [30] or commercial services from Genewiz/ThermoFisher [30])

- Gene synthesis service

Method:

- Select Host Reference Set: Identify a set of highly expressed genes from your target plant species to define the host's codon usage bias [29].

- Optimize the Sequence: Input the Cas9 amino acid sequence into a codon optimization algorithm. These tools generate a DNA sequence that encodes the same protein but uses codons that are most frequently used by the host [30]. Advanced methods using deep learning (e.g., BiLSTM-CRF models) can capture complex distribution characteristics of DNA for even more effective optimization [30].

- Synthesize Gene: Commission the synthesis of the full-length, optimized Cas9 gene from a commercial provider.

- Clone and Test: Clone the synthesized gene into your plant expression vector alongside the appropriate NLS and test its performance against the non-optimized version by measuring editing efficiency and protein levels (e.g., via Western blot).

Table 2: Key Parameters for Codon Optimization

| Parameter | Description | Impact on Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Codon Adaptation Index (CAI) | Measures the similarity of codon usage between a gene and the host's highly expressed genes. A CAI >0.8 is ideal [30]. | High CAI correlates with high translational efficiency [29]. |

| GC Content | The percentage of Guanine and Cytosine nucleotides in the sequence. | Extreme GC content (high or low) can affect mRNA stability and should be adjusted to the host's genomic average [30]. |

| Codon Frequency | The usage frequency of each synonymous codon for an amino acid. | Replacing rare codons with host-preferred codons prevents ribosomal stalling and errors [29]. |

| mRNA Secondary Structure | The folding of the mRNA molecule, particularly around the ribosome binding site. | Optimization should avoid stable secondary structures that can inhibit translation initiation [30]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Enhancing CRISPR-Cas9 Efficiency

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NLS Peptide Tags | Directs fusion proteins to the nucleus. | Use classical (monopartite/bipartite) or non-classical PY-NLS tags. Testing multiple types is recommended [26] [31]. |

| Codon-Optimized Cas9 | Maximizes Cas9 protein expression in the host. | Ensure optimization is specific to your plant species (e.g., maize, rice, wheat) for best results [30] [29]. |

| Stably Expressing Cas9 Cell Lines | Provides consistent, reproducible Cas9 expression. | Reduces variability from transient transfection and improves knockout efficiency [27]. |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants | Reduces off-target editing effects. | Crucial for applications requiring high specificity, such as potential therapeutic development [28]. |

| Bioinformatics Tools (e.g., WheatCRISPR, Benchling) | Designs specific sgRNAs and predicts potential off-target sites. | Essential for complex genomes to select unique target sites [32]. |

| Lipid-Based Transfection Reagents / Electroporation Systems | Efficiently delivers CRISPR components into cells. | Optimization of delivery method is key for hard-to-transfect cell types [27]. |

Core Concepts: Understanding Editing Efficiency

Q1: What is "editing efficiency" in the context of CRISPR/Cas9 experiments? Editing efficiency typically refers to the percentage of cells or transgenic events in which the CRISPR/Cas9 system has successfully induced mutations at the intended target site(s) in the genome. It is a crucial parameter determining the success of genome editing experiments, especially in recalcitrant species like legumes where transformation and editing efficiencies are naturally low [33].

Q2: Why is achieving high editing efficiency particularly challenging in recalcitrant plants like legumes? Recalcitrant plants, including many legumes, pose several challenges for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing:

- Low Transformation Efficiency: Difficulties in delivering CRISPR components into plant cells due to inefficient Agrobacterium-mediated transformation or other delivery methods [33].

- Tissue Culture Limitations: Poor regeneration capacity of transformed cells into whole plants [33].

- Complex Genomes: Presence of polyploidy, high repetitive DNA content, or inefficient DNA repair mechanisms can reduce editing efficiency [34].

Strategy and Optimization FAQs

Q3: What are the primary strategies for improving CRISPR/Cas9 editing efficiency in plants? Multiple strategies can be employed to enhance editing efficiency, focusing on optimizing the CRISPR system itself and the delivery methods:

- gRNA Optimization: Designing gRNAs with appropriate GC content (e.g., ~65% has shown high efficiency in grape [35]) and minimizing potential off-target effects.

- Cas9 Variants: Using high-fidelity Cas9 versions or engineered Cas9 variants with expanded PAM recognition to target more genomic sites [34].

- Expression Cassette Optimization: Employing strong, appropriate promoters (e.g., ubiquitin promoters for constitutive expression, tissue-specific promoters) to drive Cas9 and gRNA expression [36] [34].

- Delivery Method Improvement: Optimizing transformation protocols specific to the plant species, including Agrobacterium strains, culture media, and temperature conditions [33] [35].

Q4: Can you provide a specific example of a synergistically optimized system that dramatically improved efficiency? The development of the hyPopCBE-V4 system for poplar demonstrates how synergistic optimization can significantly boost efficiency. This cytosine base editing system incorporated three key modifications:

- MS2-UGI system to enhance uracil glycosylase inhibition.

- Rad51 DNA-binding domain fusion to increase single-stranded DNA binding.

- Modified nuclear localization signal (BPSV40NLS) for improved nuclear import. The result was a dramatic increase in the proportion of plants with clean C-to-T edits from 20.93% (V1) to 40.48% (V4), and the efficiency of clean homozygous editing rose from 4.65% to 21.43% [36].

Table 1: Key Parameters for Optimizing CRISPR/Cas9 Editing Efficiency

| Parameter | Optimization Strategy | Observed Impact | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| gRNA GC Content | Aim for ~65% GC content | Proportional increase in editing efficiency up to this point [35] | |

| Cas9 Expression | Use of strong, appropriate promoters | Higher expression levels correlated with increased efficiency [35] | |

| Multiplexing | Simultaneous targeting of multiple genes/loci | Enables knockout of redundant genes and complex trait engineering [34] | |

| Cas9 Variants | Engineered Cas9 with expanded PAM recognition | Increases the number of targetable sites in the genome [34] | |

| Delivery Method | Optimized Agrobacterium strains and culture conditions | Improved transformation efficiency, crucial for recalcitrant species [33] [35] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q5: What should I do if my initial editing efficiency is very low or zero?

- Verify gRNA Design: Check that your gRNA sequence is unique to the target and does not have potential off-target sites. Ensure the target site is adjacent to a valid PAM sequence (NGG for SpCas9) [17].

- Check Component Expression: Confirm that both Cas9 and gRNA are being expressed in your plant tissues. Use RT-PCR or other methods to verify.

- Optimize Delivery: For recalcitrant species, test different Agrobacterium strains, cell culture densities, and co-cultivation conditions. The choice of explant material (e.g., suspension cells vs. callus) can significantly impact results [35].

- Consider Vector System: Explore different CRISPR vector backbones with various promoter combinations (e.g., Ubi promoter for Cas9, U3/U6 promoters for gRNA) tailored for your plant species [36] [37].

Q6: How can I accurately measure editing efficiency in my experiment?

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): The most accurate method for quantifying Indel frequencies and characterizing mutation types.

- Restriction Enzyme (RE) Assay: If the edit disrupts a restriction site, PCR amplification followed by RE digestion can provide an efficiency estimate [35].

- T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) Assay: Detects mismatches in heteroduplex DNA formed by wild-type and mutant sequences, allowing for efficiency quantification [35].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Low Editing Efficiency

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No mutations detected | gRNA does not function, Cas9 not expressed, delivery failed. | Redesign gRNA; verify Cas9/gRNA expression with PCR; optimize delivery protocol [17] [35]. |

| Low mutation rate | Suboptimal gRNA, low Cas9 expression, inefficient delivery. | Optimize gRNA GC content; use stronger promoters; improve transformation conditions [34] [35]. |

| Only heterozygous mutations | Low editing activity or somatic editing not fixed. | Regenerate more lines; use promoters active in germline/meristem cells [38]. |

| High off-target effects | gRNA sequence is not specific. | Use computational tools to design specific gRNAs; employ high-fidelity Cas9 variants [25] [34]. |

Experimental Protocols for Efficiency Optimization

Protocol 1: A Stepwise Workflow for Optimizing CRISPR/Cas9 in Recalcitrant Crops

Protocol 2: gRNA GC Content Optimization (Based on Grape Study [35])

Objective: To determine the optimal GC content for gRNAs in your target species. Materials:

- Plant transformation system (e.g., embryogenic calli, suspension cells)

- CRISPR/Cas9 vectors

- DNA extraction kit

- PCR reagents

- T7 Endonuclease I or restriction enzymes for efficiency analysis

Procedure:

- Design 3-4 gRNAs targeting the same exon of a marker gene (e.g., PDS) with varying GC contents (e.g., 40%, 50%, 60%, 65%).

- Clone each gRNA into your CRISPR/Cas9 vector system.

- Transform your plant material with each construct using your standard protocol.

- After 2-3 weeks of selection, harvest transgenic cell masses and extract genomic DNA.

- PCR-amplify the target region from each sample.

- Analyze the PCR products using T7EI assay or restriction enzyme digestion to quantify editing efficiency.

- Calculate efficiency as the percentage of cleaved products relative to total PCR product.

- Correlate efficiency values with GC content to determine the optimal range for your system.