Optimized VIGS Construct Design and cDNA Library Preparation: A Comprehensive Guide for Functional Genomics

This article provides a comprehensive framework for Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) construct design and cDNA library preparation, addressing critical needs in functional genomics for researchers and drug development professionals.

Optimized VIGS Construct Design and cDNA Library Preparation: A Comprehensive Guide for Functional Genomics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) construct design and cDNA library preparation, addressing critical needs in functional genomics for researchers and drug development professionals. We explore foundational principles of VIGS technology and its application across diverse plant species, detail optimized methodologies for constructing high-efficiency silencing vectors and cDNA libraries, address common troubleshooting challenges with evidence-based solutions, and present rigorous validation approaches. By integrating current research and practical optimization strategies, this resource enables researchers to implement robust VIGS systems for rapid gene function characterization, accelerating discovery in plant biology and agricultural biotechnology.

Understanding VIGS Technology and cDNA Library Fundamentals

Principles of Virus-Induced Gene Silencing and RNA Interference Mechanisms

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) is a powerful reverse genetics technology that leverages the plant's innate RNA interference (RNAi) machinery to transiently silence target genes. This method utilizes engineered viral vectors to deliver host-derived gene fragments, triggering a sequence-specific post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) response. The core principle involves the production of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) that guide the cleavage and degradation of complementary mRNA transcripts, thereby knocking down gene expression without permanent genetic modification [1] [2].

The application of VIGS has been transformed by recent advancements, particularly the development of virus-delivered short RNA inserts (vsRNAi). While conventional VIGS relies on delivering 200-400 nucleotide (nt) cDNA inserts, novel approaches now use synthetic oligonucleotides as short as 24-32 nt to achieve highly specific silencing. This nearly 10-fold reduction in insert size significantly simplifies vector engineering, reduces cloning steps, and enhances the scalability of functional genomics in both model and non-model plant species [3] [4].

Molecular Mechanisms of RNAi and VIGS

The molecular pathway of VIGS mirrors the endogenous RNAi mechanism, which serves as an antiviral defense system in plants. The process begins when a recombinant Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV) vector, carrying a fragment of a host target gene, is introduced into the plant cell via Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated delivery (agroinoculation). Following viral replication and transcription, the plant's Dicer-like (DCL) RNases, primarily DCL2 and DCL4, recognize and process the viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) into 21-22 nt siRNAs [3] [4].

These siRNAs are then loaded into an RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), where the guide strand directs the complex to complementary mRNA transcripts for cleavage and degradation. This sequence-specific silencing is not confined to the initial site of infection; the signal is systemically spread throughout the plant via the vascular system, leading to a observable loss-of-function phenotype in tissues distant from the inoculation site [1] [5].

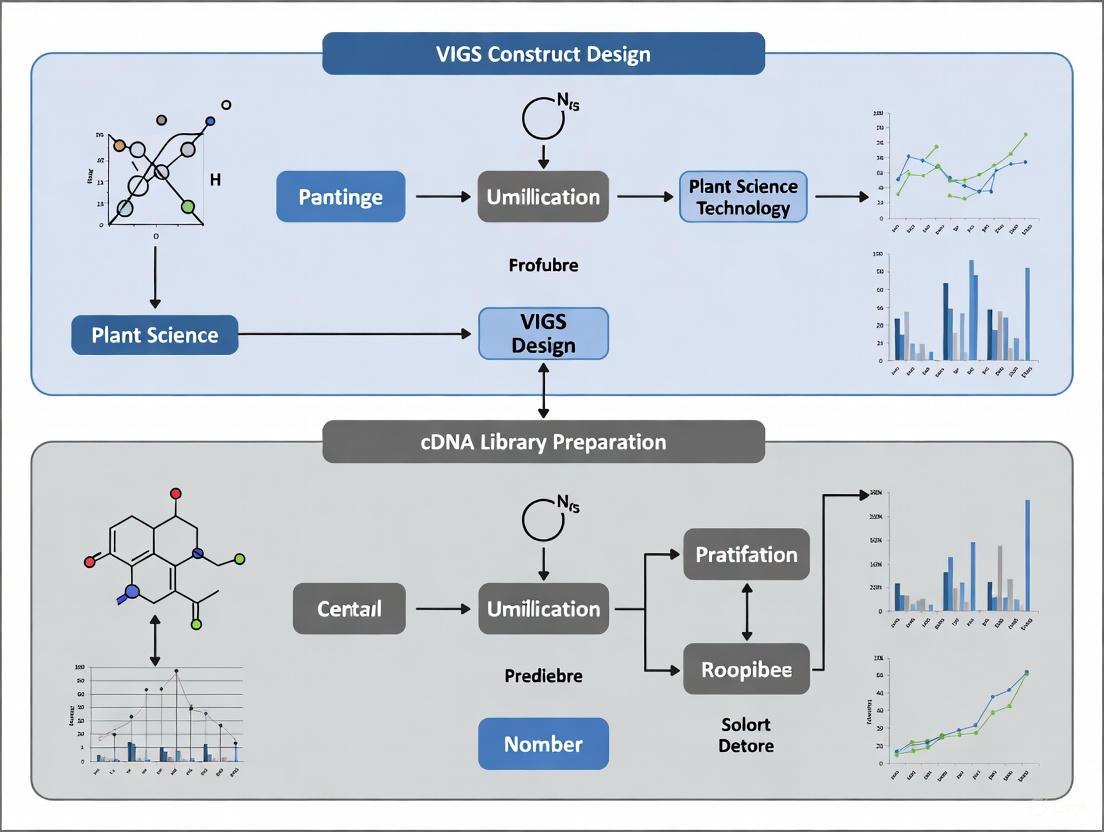

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism and experimental workflow of VIGS:

Key Experimental Parameters and Quantitative Data

The efficiency of VIGS is influenced by multiple experimental factors. The table below summarizes critical parameters and quantitative findings from recent studies:

Table 1: Key Experimental Parameters in VIGS Studies

| Experimental Factor | Target Gene/Organism | Key Findings/Quantitative Results | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insert Size | CHLI (Chlorophyll biosynthesis) in N. benthamiana | 32-nt vsRNAi: Robust silencing (x̄=0.11 chlorophyll ratio); 24-nt vsRNAi: Effective silencing (x̄=0.39); 20-nt vsRNAi: No silencing | [3] |

| Silencing Efficiency | GmPDS in Soybean | 65% to 95% silencing efficiency across experiments, validated by qPCR and photobleaching phenotypes | [1] |

| Infection Method | HaPDS in Sunflower | Seed vacuum infiltration: Up to 91% infection rate depending on genotype; Cotyledon node immersion in soybean: >80% cell infiltration efficiency | [5] [1] |

| Genotype Dependency | Six sunflower genotypes | Infection percentage varied from 62% to 91%; silencing phenotype spread differed significantly between genotypes | [5] |

| Tissue and Development Stage | CdCRY1 and CdLAC15 in Camellia drupifera capsules | Optimal silencing: ~69.80% at early stage for CdCRY1; ~90.91% at mid stage for CdLAC15 | [6] |

The selection of appropriate reference genes for reverse-transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) is crucial for accurate validation of silencing efficiency. A 2025 study in cotton-herbivore interactions using VIGS found that traditional reference genes like GhUBQ7 and GhUBQ14 were the least stable, whereas GhACT7 and GhPP2A1 provided superior stability under biotic stress conditions [7].

Detailed VIGS Protocols

TRV-Based VIGS for Soybean via Cotyledon Node Immersion

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 study, establishes a highly efficient VIGS system for soybean [1].

- Vector Construction: Clone a 200-300 bp fragment of the target gene (e.g., GmPDS, GmRpp6907) into the pTRV2-GFP vector using EcoRI and XhoI restriction sites. Transform the recombinant plasmid into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101.

- Plant Material Preparation: Surface-sterilize soybean seeds and imbibe in sterile water until swollen. Prepare longitudinally bisected half-seed explants to expose the cotyledonary node.

- Agroinfiltration: Harvest Agrobacterium cultures (harboring both pTRV1 and the recombinant pTRV2) at OD600 = 0.8-1.2 by centrifugation. Resuspend the pellet in induction buffer (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl2, 200 µM acetosyringone) to a final OD600 of 1.5. Incubate the suspension at room temperature for 3-4 hours. Immerse the fresh half-seed explants in the Agrobacterium suspension for 20-30 minutes with gentle agitation.

- Post-Inoculation Culture and Analysis: Co-cultivate the infected explants on tissue culture medium for 2-3 days in the dark. Transfer plants to soil and maintain under standard growth conditions. Silencing phenotypes (e.g., photobleaching for GmPDS) typically appear in systemic leaves within 14-21 days post-inoculation (dpi). Validate silencing efficiency through qPCR and fluorescence microscopy for GFP-tagged vectors.

vsRNAi Cloning into JoinTRV for High-Throughput Silencing

This novel protocol from 2025 enables the use of ultra-short RNA inserts for highly specific gene silencing [3] [4].

- vsRNAi Design: Leverage curated genomic annotations and transcriptomic data to identify 32-nt conserved regions within the target gene's coding sequence. For plants with homeologous gene pairs (e.g., allotetraploid N. benthamiana), design a single vsRNAi to target both copies simultaneously.

- One-Step Digestion-Ligation: Chemically synthesize complementary DNA oligonucleotide pairs spanning the vsRNAi sequence. Digest the pLX-TRV2 plasmid with appropriate restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI-HFv2) and ligate the annealed vsRNAi duplex directly into the vector in a single reaction using T4 DNA ligase.

- Agrobacterium Preparation and Inoculation: Transform the constructed pLX-TRV2-vsRNAi and the helper plasmid pLX-TRV1 into A. tumefaciens (e.g., strain AGL1 or GV3101). Grow Agrobacterium cultures to OD600 ~0.8-1.0 in LB medium with appropriate antibiotics, 10 mM MES, and 20 µM acetosyringone. Harvest cells by centrifugation and resuspend in induction buffer (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl2, 200 µM acetosyringone) to OD600 1.0. Incubate for 3 hours at room temperature.

- Plant Infiltration and Phenotyping: Mix the pLX-TRV1 and pLX-TRV2-vsRNAi suspensions in a 1:1 ratio. Inoculate the mixture into the abaxial air spaces of leaves of 2-3 week-old plants using a needleless syringe. Maintain inoculated plants under standard conditions. Analyze silencing in upper, uninoculated leaves starting at 10-14 dpi (e.g., leaf yellowing for CHLI silencing, reduced chlorophyll levels measured by fluorometry).

The experimental workflow for these protocols is visualized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for VIGS Experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Details |

|---|---|---|

| Viral Vectors | Engineered backbones for delivering target gene inserts | pTRV1/pTRV2 (Classical system); pLX-TRV1/pLX-TRV2 (JoinTRV system for vsRNAi); BSMV vectors (for cereals) [1] [3] [2] |

| Agrobacterium Strains | Delivery vehicle for viral T-DNA vectors | GV3101, AGL1; Prepared with antibiotics (kanamycin, rifampicin, gentamicin) [1] [4] [7] |

| Enzymes for Cloning | Vector construction and insert preparation | Restriction enzymes (EcoRI, XhoI, BsaI-HFv2); T4 DNA Ligase; High-fidelity DNA Polymerase for fragment amplification [1] [4] |

| Induction Buffers | Activate Agrobacterium for efficient T-DNA transfer | Acetosyringone (200 µM) in MES/MgCl₂ buffer; Critical for virulence induction [4] [7] [5] |

| Reference Genes | qPCR normalization for accurate silencing validation | GhACT7/GhPP2A1 (stable in cotton VIGS); Avoid less stable genes like GhUBQ7 [7] |

| Visual Markers | Positive controls for silencing efficiency | PDS (Phytoene desaturase): Causes photobleaching; CHLI (Mg-chelatase): Causes leaf yellowing [1] [3] [5] |

Application Notes and Technical Considerations

Critical Factors for Success

- Plant Growth Conditions: The age and health of plants are paramount. 2-3 week-old plants are generally ideal for agroinfiltration. Inoculating plants older than 4 weeks can significantly delay or compromise silencing efficiency. Maintain consistent light, temperature, and humidity throughout the experiment [4].

- Genotype Dependency: VIGS efficiency varies considerably among genotypes and species. In sunflower, infection rates ranged from 62% to 91% across different cultivars. Preliminary tests to identify susceptible genotypes are recommended for non-model species [5].

- Viral Vector Mobility and Silencing Spread: The presence of TRV (detectable by RT-PCR) is not always confined to tissues showing visible silencing phenotypes. Silencing spreads more actively in young, developing tissues compared to mature ones. The extent of phenotypic spread can be genotype-dependent [5].

- Specificity and Off-Target Effects: Bioinformatic tools like the SGN VIGS Tool and pssRNAit should be used to design inserts with high specificity to the target gene and minimal similarity (<40-50%) to other genes in the genome. The use of vsRNAi can further reduce off-target effects compared to long inserts [3] [6].

Troubleshooting Common Challenges

- Low Infection Efficiency: Optimize the Agrobacterium strain, optical density (OD600 0.8-1.2), and infiltration method. For recalcitrant species or tissues, vacuum infiltration or prolonged co-cultivation (e.g., 6 hours) can dramatically improve results [6] [5].

- Weak or Transient Silencing: Ensure the insert is derived from a conserved region of the target gene and is of appropriate length. For high-throughput applications, the vsRNAi (24-32 nt) approach provides robust and quantitative silencing phenotypes equivalent to longer fragments [3].

- Artifacts and Contamination: Always include empty vector controls (pTRV1+pTRV2-empty) and positive controls (pTRV1+pTRV2-PDS). Maintain separate areas for pre- and post-PCR work to prevent nucleic acid contamination. Use strand-split artifact reads (SSARs) detection and chimera filtration programs to minimize artifacts during library preparation [4] [8].

Key Applications in Functional Genomics and Drug Target Discovery

Functional genomics provides the critical link between genetic information and biological function, enabling the systematic identification and validation of novel therapeutic targets. By elucidating the roles and interactions of genes and genetic elements, these approaches offer insights into their involvement in disease processes and treatment responses. In the context of drug discovery, functional genomics has evolved from studying individual genes to employing high-throughput technologies that can interrogate entire genomes. These advances are particularly valuable given that a substantial proportion of human genes remain poorly characterized despite decades since the completion of the Human Genome Project [9] [10].

The pharmaceutical industry faces a significant productivity challenge, with failure rates for drug candidates in clinical trials soaring to 95%, driving the average cost of bringing a new medicine to market beyond $2.3 billion [11]. This crisis has accelerated the adoption of functional genomics approaches, as targets with human genetic support are 2.6 times more likely to succeed in clinical trials [11]. This review examines key applications in functional genomics and their transformative impact on drug target discovery, with particular emphasis on technical advances that enable more physiologically relevant, high-throughput analyses.

Advanced Functional Genomics Technologies

Perturbomics: CRISPR-Cas Screening for Systematic Gene Function Annotation

Perturbomics represents a powerful functional genomics approach that annotates genes based on phenotypic changes induced by targeted gene perturbation [9] [10]. The core principle is that gene function can be most directly inferred by altering gene activity and systematically measuring resulting phenotypic consequences. CRISPR-Cas-based genome and epigenome editing have become the method of choice for perturbomics studies, enabling identification of target genes whose modulation holds therapeutic potential for diseases including cancer, cardiovascular disorders, and neurodegeneration [10].

The basic framework for a perturbomics study involves designing guide RNA (gRNA) libraries targeting either genome-wide gene sets or specific pathways, synthesizing these libraries as chemically modified oligonucleotides cloned into viral vectors, and transducing them into Cas9-expressing cells [10]. The transduced cells are then subjected to selective pressures such as drug treatments, nutrient deprivation, or fluorescence-activated cell sorting based on phenotypic markers. Following selection, genomic DNA is sequenced to identify enriched or depleted gRNAs, with computational tools correlating specific genes with observed phenotypes [10].

Table 1: CRISPR Screening Modalities and Their Applications in Drug Discovery

| Screening Type | Molecular Tool | Key Features | Primary Applications in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loss-of-function | CRISPR-Cas9 | Indels cause frameshift mutations | Identification of essential genes, drug resistance mechanisms |

| CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) | dCas9-KRAB fusion | Gene silencing without DNA cleavage | Targeting lncRNAs, enhancer elements, DSB-sensitive cells |

| CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) | dCas9-activator fusion | Gene overexpression | Gain-of-function studies, target validation |

| Base editing | Cas9-deaminase fusions | Single nucleotide changes | Functional analysis of SNPs, variant characterization |

| Prime editing | Cas9-reverse transcriptase | Small insertions, deletions, substitutions | Saturation mutagenesis, resistance variant identification |

Recent technical advances have expanded CRISPR screening beyond conventional loss-of-function approaches. Nuclease-inactive Cas9 (dCas9) fused to functional domains enables both gene repression (CRISPRi) and activation (CRISPRa) screens [10]. CRISPRi screens complement knockout studies by enabling targeting of non-coding RNAs and transcriptional enhancers, while CRISPRa screens enhance confidence in identifying target genes through gain-of-function approaches. Base editors and prime editors further expand capabilities by enabling functional analysis of genetic variants, including single-nucleotide polymorphisms of unknown significance [10].

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) and cDNA Library Approaches

Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) has emerged as a powerful functional genomics tool in plants, exploiting the natural antiviral RNA silencing mechanism [12]. When plants are infected with recombinant viruses containing host gene inserts, the plant's RNA silencing machinery generates small interfering RNAs targeted against corresponding host mRNAs, effectively degrading them and producing knockout or knockdown phenotypes [12].

Critical to VIGS effectiveness is the optimal design of cDNA inserts. Research has established clear guidelines for constructing efficient VIGS constructs in tobacco rattle virus (TRV) vectors [12]:

- Insert length: Fragments between 200 bp and 1300 bp lead to efficient silencing

- Insert position: Middle regions of cDNAs perform better than 5' or 3' located inserts

- Sequence composition: Homopolymeric regions (e.g., poly(A/T) tails) should be excluded as they reduce silencing efficiency

Table 2: Optimized VIGS Construct Parameters for Functional Genomics

| Parameter | Optimal Range/Guideline | Impact on Silencing Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Insert Length | 200-1300 bp | Fragments <200 bp or >1300 bp show reduced efficiency |

| Insert Position | Middle cDNA regions | 5' and 3' located inserts perform poorly |

| Homopolymeric Regions | Exclusion recommended | poly(A) or poly(G) regions of 24 bp reduce efficiency |

| Insert Orientation | Antisense relative to viral coat protein | Essential for proper siRNA generation |

| Library Construction | RsaI digestion to remove poly(A) tails | 99.5% of constructs lack poly(A) tails |

These principles have been successfully applied in functional genomics screens where cDNA libraries in VIGS vectors are used to infect plant populations, with each individual potentially silencing a different gene [12]. This "fast-forward genetics" approach enables direct identification of genes responsible for phenotypes without genetic mapping, as the cDNA fragment causing a phenotype can be identified simply by sequencing the VIGS construct from affected plants [12].

Applications in Therapeutic Target Discovery

Oncology Target Identification

CRISPR-based perturbomics has revolutionized oncology drug target discovery by enabling systematic identification of genes essential for cancer cell survival, drug resistance, and metastatic potential. Early proof-of-concept studies demonstrated the power of this approach by identifying genes that confer resistance to BRAF inhibitors in melanoma [10]. More recent advances have integrated single-cell RNA sequencing with CRISPR screens, enabling comprehensive characterization of transcriptomic changes following gene perturbation in heterogeneous tumor populations [10].

The integration of CRISPR screening with organoid models has been particularly transformative for cancer research. Organoid systems preserve the cellular heterogeneity and tissue architecture of original tumors, providing more physiologically relevant models for identifying therapeutic targets [13]. These human-relevant systems improve the predictive validity of target identification efforts, potentially bridging the gap between traditional cell line models and clinical response.

Central Nervous System Disorders

Functional genomics approaches have accelerated target discovery for neurodegenerative disorders, which have proven particularly challenging for drug development. CRISPR screens in neuronal models have identified genes involved in tau phosphorylation, α-synuclein aggregation, and oxidative stress response, revealing potential therapeutic targets for Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases [10]. The development of CRISPR tools compatible with post-mitotic neurons, including CRISPRi and CRISPRa systems, has been especially valuable given the sensitivity of neuronal cells to DNA double-strand breaks [10].

Infectious Disease Mechanisms and Host-Directed Therapies

Functional genomics has identified novel host factors essential for pathogen entry and replication, revealing opportunities for host-directed therapies that are less susceptible to pathogen resistance. Genome-wide CRISPR screens have uncovered previously unknown host dependency factors for viral pathogens including SARS-CoV-2, HIV, and influenza [13]. These approaches have also identified mechanisms of antibacterial resistance and potential adjuvants to enhance conventional antibiotic efficacy.

Agricultural and Plant Biology Applications

Beyond human therapeutics, functional genomics has transformed crop improvement through rapid identification of disease resistance genes. An optimized workflow combining EMS mutagenesis, speed breeding, and genomics-assisted gene cloning enabled identification of the wheat stem rust resistance gene Sr6 in just 179 days, dramatically accelerating what was previously a multi-year process [14]. This approach required only three square meters of plant growth space, demonstrating the efficiency gains possible with modern functional genomics methodologies [14].

Similar approaches have elucidated the molecular basis of historical traits first described by Mendel, including the identification of a ~100-kb genomic deletion upstream of the Chlorophyll synthase (ChlG) gene that confers the yellow pod phenotype in peas [15]. These discoveries not only advance fundamental biological understanding but also enable precision breeding for improved agricultural productivity.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: High-Throughput CRISPR Screening for Drug Target Identification

Principle: This protocol describes a pooled CRISPR knockout screen to identify genes mediating response to therapeutic compounds, enabling discovery of novel drug targets and resistance mechanisms [10].

Materials:

- Cas9-expressing cell line of interest

- Lentiviral sgRNA library (e.g., Brunello or GeCKO libraries)

- Selection antibiotics (puromycin, blasticidin)

- Therapeutic compound for screening

- DNA extraction kit

- PCR purification kit

- Next-generation sequencing platform

Procedure:

- Library Design and Preparation: Select or design sgRNA library targeting genes of interest, including non-targeting control guides. Amplify library and clone into lentiviral transfer plasmid.

- Lentivirus Production: Package sgRNA library into lentiviral particles using HEK293T cells and standard packaging plasmids.

- Cell Infection and Selection: Infect Cas9-expressing cells at low MOI (0.3-0.5) to ensure single integration events. Select transduced cells with appropriate antibiotics for 5-7 days.

- Compound Treatment: Split cells into treatment and control groups. Treat with therapeutic compound at predetermined IC50 concentration or vehicle control.

- Population Maintenance: Culture cells for 14-21 days, maintaining representation of at least 500 cells per sgRNA to prevent stochastic dropout.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Harvest cells at endpoint and extract genomic DNA using large-scale preparation methods.

- sgRNA Amplification and Sequencing: Amplify integrated sgRNA sequences from genomic DNA using two-step PCR to add sequencing adapters and barcodes.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Sequence amplified fragments on Illumina platform. Align sequences to reference sgRNA library and calculate enrichment/depletion using specialized algorithms (MAGeCK, CERES).

Validation: Confirm screening hits through individual sgRNA validation, orthogonal assays (rescue experiments, pharmacologic inhibition), and mechanistic studies to elucidate pathway involvement.

Protocol: VIGS-Based Forward Genetics Screening in Plants

Principle: This protocol uses virus-induced gene silencing with cDNA libraries to perform forward genetic screens in plants, enabling functional characterization of genes involved in developmental, metabolic, or defense processes [12].

Materials:

- TRV-based VIGS vectors (pYL156, pYL279)

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101

- cDNA library with optimized insert properties (200-500 bp, RsaI-digested, no poly(A) tails)

- Plant growth facilities

- Sequencing capabilities for insert identification

Procedure:

- Library Construction: Synthesize cDNA on solid phase support. Digest with RsaI to generate short fragments (200-500 bp) without poly(A) tails. Optionally perform suppression subtractive hybridization to enrich for differentially expressed transcripts. Clone into TRV-RNA2 vector.

- Agrobacterium Transformation: Transform library vectors into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 through electroporation.

- Plant Infiltration: Grow Nicotiana benthamiana plants to 4-week stage. Infiltrate with Agrobacterium cultures containing both TRV-RNA1 and TRV-RNA2 (with library inserts) using syringe infiltration.

- Phenotypic Screening: Monitor plants for development of phenotypes of interest (e.g., altered development, enhanced susceptibility, metabolic changes).

- Insert Recovery and Identification: Isolate viral RNA from plants showing phenotypes. Amplify and sequence inserted cDNA fragments to identify genes responsible for observed phenotypes.

- Validation: Confirm gene-phenotype relationship through targeted VIGS with specific inserts and orthogonal approaches (overexpression, stable transformation).

Technical Notes: For optimal results, use inserts positioned in the middle of cDNAs, exclude homopolymeric regions, and ensure insert lengths between 200-1300 bp [12]. Library complexity should be sufficient to cover the transcriptome of interest with multiple-fold coverage.

Technical Guidelines and Optimization Strategies

cDNA Library Preparation Method Comparisons

The choice of cDNA synthesis and library preparation method significantly impacts the quality and interpretation of functional genomics data [16]. Different methods vary in their requirements for input RNA, efficiency of ribosomal RNA removal, strand specificity, and technical reproducibility.

Table 3: Comparison of cDNA Library Preparation Methods for Functional Genomics

| Method | Input RNA Requirement | rRNA Removal Efficiency | Strand Specificity | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TruSeq Stranded Total RNA | 100-1000 ng | <1% rRNA reads | Yes (antisense) | Standard RNA-Seq with sufficient input |

| SMARTer Stranded RNA-Seq | 1-100 ng | <3% rRNA reads | Yes (sense) | Low input applications |

| Ovation RNA-Seq V2 | 1-100 ng | <1% rRNA reads | No | Very low input, non-quantitative |

| Encore Complete Prokaryotic | 1-100 ng | ~38% rRNA reads | Yes (sense) | Prokaryotic RNA-Seq with limited input |

Evaluation of these methods has revealed significant variations in organism representation and gene expression patterns [16]. The TruSeq method generally performs best but requires substantial input RNA (hundreds of nanograms). The SMARTer method represents the best compromise for lower input amounts, while the Ovation system, though efficient for low inputs, introduces biases that limit its utility for quantitative analyses [16].

AI and Data Integration Platforms

Advanced computational platforms are increasingly essential for processing and interpreting functional genomics data. Platforms like Mystra provide AI-enabled analysis of human genetics data, unifying genomic information, analysis tools, and collaboration capabilities to accelerate target identification and validation [11]. These systems can turn complex genetic analyses that historically took months into results generated in minutes, dramatically increasing research and development productivity [11].

Key capabilities of these platforms include:

- Harmonization of diverse datasets including GWAS, transcriptomics, and proteomics

- Application of machine learning to identify biologically significant patterns

- Integration of cross-functional team inputs through shared sources of truth

- Generation of actionable insights for target prioritization and clinical strategy

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1: Integrated Functional Genomics Workflow for Drug Target Discovery. This diagram illustrates parallel pathways for CRISPR-based and VIGS-based approaches, converging on target identification and validation.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Functional Genomics Applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Systems | SpCas9, dCas9-KRAB, dCas9-VPR | Gene editing, repression, activation | Specificity, efficiency, modularity |

| sgRNA Libraries | Genome-wide (Brunello), Targeted (Kinase) | High-throughput gene perturbation | Coverage, minimal off-target effects |

| Viral Delivery Systems | Lentivirus, AAV | Efficient gene delivery | Tropism, payload capacity, safety |

| VIGS Vectors | TRV-based (pYL279), PVX-based | Plant gene silencing | Host range, silencing efficiency |

| cDNA Synthesis Kits | TruSeq, SMARTer, Ovation | Library preparation for sequencing | Input requirements, strand specificity |

| Cell/Plant Models | Organoids, Near-isogenic lines | Physiologically relevant screening | Biological relevance, genetic stability |

| Screening Platforms | Mystra, Labguru | Data analysis and integration | AI-capabilities, collaboration features |

Functional genomics approaches have fundamentally transformed the landscape of drug target discovery, providing systematic frameworks for elucidating gene function and establishing causal relationships between genes and disease processes. CRISPR-based perturbomics and VIGS-based screening represent complementary technologies that enable comprehensive functional annotation of genes across human and plant systems. The integration of these approaches with advanced computational platforms, human-relevant model systems, and automated workflows has accelerated the identification and validation of therapeutic targets while de-risking the drug development process. As these technologies continue to evolve through improvements in editing precision, screening scalability, and data integration capabilities, functional genomics will play an increasingly central role in bridging the gap between genetic information and novel therapeutic interventions.

cDNA Library Types and Their Roles in High-Throughput Genetic Screens

Complementary DNA (cDNA) libraries represent a snapshot of the transcriptome at a specific moment, containing DNA copies synthesized from fully transcribed messenger RNA (mRNA). Unlike genomic libraries, cDNA clones contain only expressed genes without introns or non-coding regions, making them invaluable for studying gene function, protein coding sequences, and regulatory mechanisms [17]. In high-throughput genetic screens, cDNA libraries serve as powerful resources for both forward and reverse genetics approaches, enabling researchers to systematically identify genes involved in specific biological processes, disease pathways, or drug responses.

The construction of cDNA libraries begins with mRNA isolation, typically through chromatographic purification using oligo-dT columns that target the poly-A tails of eukaryotic mRNA. Through reverse transcription, mRNA is converted to single-stranded cDNA, which is then transformed into double-stranded DNA suitable for cloning into appropriate vectors [17]. The resulting libraries can be screened to identify genes based on their functional effects, expression patterns, or protein interactions, providing critical insights into gene function on a genomic scale.

Major cDNA Library Types and Their Characteristics

Conventional cDNA Libraries

Standard cDNA libraries are constructed from total mRNA populations of cells or tissues at specific developmental stages or under particular physiological conditions. These libraries typically employ oligo(dT) primers for reverse transcription and result in a mixture of cDNA fragments of varying lengths. A significant limitation of conventional libraries is the presence of abundant housekeeping transcripts, which can overshadow rare mRNAs, potentially missing low-abundance transcripts that may have crucial biological functions [17] [18]. Additionally, the inclusion of poly(A) tails and heterogeneous fragment sizes in these libraries can reduce their efficiency in certain applications, particularly virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) where homopolymeric regions impair silencing efficiency [12].

Normalized and Subtracted cDNA Libraries

To address the issue of transcript abundance variation, normalized libraries are engineered to reduce the representation of highly expressed genes while maintaining the representation of rare transcripts. This is achieved through reassociation kinetics-based methods or duplex-specific nuclease treatments, which degrade abundant cDNAs while preserving rare sequences. Similarly, subtracted libraries enrich for differentially expressed genes between two samples by removing common sequences through hybridization and removal of cDNA-cDNA hybrids [12]. These specialized libraries significantly enhance the discovery of rare transcripts and are particularly valuable for identifying differentially expressed genes in biological processes such as stress responses, development, or disease progression.

VIGS-Optimized cDNA Libraries

VIGS-optimized libraries represent a specialized category designed specifically for virus-induced gene silencing screens. These libraries incorporate specific design principles to maximize silencing efficiency: cDNA fragments typically range from 200-500 bp, are positioned in the middle of the coding sequence, and exclude homopolymeric regions like poly(A) tails that can reduce silencing effectiveness [12] [6]. The construction method involves solid-phase cDNA synthesis followed by restriction digestion with enzymes such as RsaI to generate short cDNA fragments lacking poly(A) tails. These libraries are particularly powerful for fast-forward genetic screens where the cDNA fragment responsible for a phenotype can be directly identified by sequencing without genetic mapping [12].

Table 1: Comparison of Major cDNA Library Types for Genetic Screens

| Library Type | Key Features | Optimal Insert Size | Primary Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional cDNA | Oligo(dT) primed, includes poly(A) tails, full-length or partial transcripts | Varies (often 0.5-8 kb) | Expression cloning, transcript identification | Comprehensive transcript representation | Dominated by abundant transcripts, includes non-coding regions |

| Normalized/Subtracted | Reduced abundance variation, enriched for differentially expressed genes | Varies | Discovery of rare transcripts, differential expression studies | Enhanced discovery of low-abundance genes | Complex construction process, may lose some transcript classes |

| VIGS-Optimized | Defined insert size, middle-gene positioning, no homopolymeric regions | 200-1300 bp (optimal: 200-500 bp) | High-throughput loss-of-function screens, functional genomics | High silencing efficiency, direct phenotype-gene linkage | Requires specialized vector systems, host-dependent |

cDNA Libraries in Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) Screens

VIGS Mechanism and Workflow

Virus-induced gene silencing harnesses the plant's innate RNA interference (RNAi) machinery as a powerful tool for functional genomics. When plants are infected with recombinant viruses containing host gene fragments inserted into the viral genome, the replication process generates double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) intermediates. These dsRNA molecules are recognized by the plant's defense system and processed into small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) by Dicer-like enzymes. The siRNAs are then incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which guides sequence-specific degradation of complementary host mRNAs, effectively knocking down target gene expression [12] [19]. This process deceives the plant into targeting its own transcripts as if they were viral RNA, resulting in a loss-of-function phenotype that reveals gene function.

The typical VIGS workflow begins with the selection of a target gene region, usually 200-500 bp from the middle of the coding sequence to maximize silencing efficiency and minimize off-target effects. This fragment is cloned into a VIGS vector such as Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV), which is widely used due to its broad host range, mild symptoms, and efficient systemic movement [12] [19] [6]. The recombinant vector is then introduced into plant cells via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, spray inoculation, or vacuum infiltration. For challenging tissues like lignified capsules, specialized methods such as pericarp cutting immersion have been developed, achieving up to 93.94% infiltration efficiency [6]. Following viral replication and spread, silencing phenotypes typically emerge within 2-3 weeks, after which molecular and phenotypic analyses can be conducted.

Diagram 1: VIGS screening workflow for functional genomics.

VIGS Vector Systems and Delivery Methods

Various viral vectors have been developed for VIGS, with Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV) emerging as one of the most widely used systems due to its ability to infect a broad range of host plants, induce mild symptoms, and spread efficiently throughout the plant. TRV-based vectors typically consist of two modules: TRV1, encoding replication and movement proteins, and TRV2, containing the coat protein and the insertion site for target gene fragments [12] [19]. The target sequence is cloned in antisense orientation relative to the viral coat protein promoter, ensuring proper processing into silencing triggers.

Delivery methods have evolved to accommodate different plant species and tissues. Traditional leaf infiltration using needleless syringes remains common for dicotyledonous plants with accessible leaf structures. For more challenging applications, such as seed germination stages or recalcitrant tissues, innovative methods like seed imbibition-mediated VIGS (Si-VIGS) have been developed. This approach exploits the natural wounding that occurs as radicles emerge during germination, providing entry points for Agrobacterium carrying TRV vectors [19]. In woody plants with lignified tissues, pericarp cutting immersion has proven highly effective, achieving infiltration efficiencies over 90% in Camellia drupifera capsules [6]. Other methods include vacuum infiltration, agrodrench (pouring Agrobacterium cultures onto soil), and fruit-bearing shoot infusion, each with specific advantages for particular tissue types or developmental stages.

Design Principles for Effective VIGS Constructs

Strategic design of VIGS constructs is critical for successful gene silencing. Research has established clear guidelines for optimizing silencing efficiency: insert lengths should range from approximately 200 bp to 1300 bp, with 200-500 bp being most common in practical applications [12] [6]. Positioning within the target gene significantly affects efficiency, with fragments from the middle of the cDNA performing better than those from the 5' or 3' ends. Homopolymeric regions, particularly poly(A) tails, substantially reduce silencing efficiency and should be excluded from constructs [12].

Specificity is another crucial consideration, as off-target silencing can confound phenotypic interpretation. Bioinformatics tools such as the SGN VIGS Tool enable researchers to screen candidate sequences for potential off-target effects by assessing similarity to other genes in the genome [6]. Optimal constructs should share less than 40% similarity with non-target genes to minimize cross-silencing. For comprehensive functional analysis, some researchers design multiple non-overlapping constructs targeting different regions of the same gene, providing confirmation that observed phenotypes result from silencing the intended target rather than off-target effects.

Table 2: Quantitative Guidelines for VIGS Construct Design Based on Experimental Evidence

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Effect on Silencing Efficiency | Experimental Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insert Length | 192-1304 bp (efficient); 200-500 bp (commonly used) | Shorter fragments (<192 bp) show reduced efficiency; longer fragments within range work well | NbPDS silencing in N. benthamiana; 103 bp fragment showed reduced efficiency vs. 192 bp [12] |

| Insert Position | Middle of cDNA | 5' and 3' located inserts perform poorly compared to middle fragments | Positional analysis of NbPDS cDNA; middle fragments showed strongest silencing [12] |

| Homopolymeric Regions | Exclusion of poly(A/T) and poly(G) tails | Inclusion of 24 bp poly(A) or poly(G) reduces silencing efficiency | Direct testing of homopolymeric regions in NbPDS; poly(A) and poly(G) both impaired function [12] |

| Sequence Specificity | <40% similarity to non-target genes | Higher similarity increases off-target silencing risk | Specificity screening using SGN VIGS Tool in Camellia drupifera [6] |

| Delivery Method Efficiency | Varies by tissue type | Pericarp cutting immersion: ~94%; Leaf injection: ~95% in tomato | Tissue-specific optimization in woody vs. herbaceous plants [19] [6] |

High-Throughput Applications and Protocol

Fast-Forward Genetic Screens

The integration of cDNA libraries with VIGS technology enables powerful fast-forward genetic screens where complex cDNA populations are cloned directly into viral vectors and used to infect plant populations. In such screens, each plant receives a different cDNA fragment, generating a mosaic of silenced tissues with distinct loss-of-function phenotypes [12]. When a plant exhibits an interesting phenotype, the causative cDNA fragment can be rapidly identified by sequencing the VIGS construct, eliminating the need for laborious genetic mapping. This approach was successfully demonstrated in a screen of 4992 plant cDNAs in potato virus X (PVX) to identify suppressors of the hypersensitive response associated with Pto-mediated resistance against Pseudomonas syringae [12].

High-throughput VIGS screens require specialized cDNA libraries optimized for silencing efficiency. The construction protocol involves several key steps: first, cDNA is synthesized on a solid-phase support, ensuring uniform quality and minimizing handling losses. The cDNA is then digested with restriction enzymes such as RsaI, which generates short fragments while eliminating poly(A) tails that impair silencing [12]. To enrich for biologically relevant transcripts, suppression subtractive hybridization can be employed to select for differentially expressed genes under specific conditions. Finally, fragments are cloned directly into TRV vectors in the antisense orientation, creating a ready-to-use resource for large-scale functional genomics. This approach yielded VIGS libraries with 99.5% of inserts lacking poly(A) tails, of which approximately 30% were in the optimal 401-500 bp size range [12].

Detailed Protocol: VIGS-Optimized cDNA Library Construction

Materials and Reagents

- Tissue sample of interest (100 mg fresh weight)

- mRNA extraction kit (e.g., Dynabeads mRNA DIRECT Kit)

- Reverse transcriptase (e.g., Maxima H Minus Reverse Transcriptase)

- Restriction enzyme RsaI and appropriate buffer

- TRV-based vector system (pTRV1 and pTRV2 or equivalents)

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101

- Luria-Bertani (LB) medium with appropriate antibiotics

- Infiltration buffer (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl₂, 200 μM acetosyringone, pH 5.6)

Procedure

- mRNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

- Grind 100 mg of fresh tissue in liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle

- Extract total RNA using a commercial kit, following manufacturer's instructions

- Isolate mRNA using oligo(dT)25 magnetic beads

- Synthesize first-strand cDNA using reverse transcriptase with oligo(dT) primer

- Generate double-stranded cDNA using DNA polymerase

Library Construction and Vector Cloning

- Digest dsDNA with RsaI restriction enzyme for 2 hours at 37°C

- Purify fragments between 200-500 bp using gel extraction or size selection columns

- Ligate purified fragments into pre-digested TRV2 vector using T4 DNA ligase

- Transform ligation mixture into E. coli DH5α competent cells

- Plate on selective media and incubate overnight at 37°C

Library Validation and Agroinfiltration

- Pick individual colonies and validate insert size by colony PCR

- Sequence validate a subset of clones to assess library quality

- Transform validated TRV2 constructs into Agrobacterium strain GV3101

- Grow Agrobacterium cultures overnight in LB medium with antibiotics

- Harvest cells by centrifugation and resuspend in infiltration buffer to OD₆₀₀ = 1.0

- Mix Agrobacterium containing TRV1 and TRV2 constructs in 1:1 ratio

- Infiltrate into plant tissues using appropriate method (leaf infiltration, seed imbibition, etc.)

Phenotypic Screening and Analysis

- Monitor plants for silencing phenotypes for 3-4 weeks post-infiltration

- Document visual phenotypes with photography

- Validate silencing efficiency for target genes by qRT-PCR

- For plants showing interesting phenotypes, recover inserted fragment by PCR

- Sequence recovered fragments to identify silenced genes

Diagram 2: VIGS-optimized cDNA library construction workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for VIGS cDNA Library Construction and Screening

| Reagent/Kit | Manufacturer/Example | Function in Workflow | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA Isolation Kit | Dynabeads mRNA DIRECT Kit [20] | Purification of poly(A)+ RNA from total RNA extracts | Critical for woody tissues with high RNase content; uses magnetic oligo(dT)25 beads |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Maxima H Minus Reverse Transcriptase [21] [20] | Synthesis of first-strand cDNA from mRNA template | High-temperature reverse transcription improves efficiency for GC-rich templates |

| Restriction Enzyme | RsaI [12] | Generation of short cDNA fragments without poly(A) tails | Creates blunt-ended fragments optimal for VIGS library construction |

| VIGS Vector System | TRV-based vectors (pTRV1/pTRV2) [12] [19] [6] | Delivery of target gene fragments for silencing | TRV provides broad host range and efficient systemic movement |

| DNA Ligase | T4 DNA Ligase [22] | Ligation of cDNA fragments into VIGS vectors | Essential for high-efficiency library construction; requires optimized vector:insert ratios |

| Agrobacterium Strain | GV3101 [6] | Delivery of VIGS constructs into plant cells | Preferred for efficient transformation and minimal phytotoxicity |

| Infiltration Buffer Components | MES, MgCl₂, Acetosyringone [6] | Enhancement of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation | Acetosyringone induces vir genes essential for T-DNA transfer |

| Library Quantification Kits | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit [21] [20] | Accurate measurement of library concentration | Fluorometric methods provide more accurate quantification than spectrophotometry for NGS |

Technical Challenges and Optimization Strategies

Despite its power, the VIGS screening approach faces several technical challenges that require careful optimization. Incomplete silencing resulting in mosaic patterns of silenced and non-silenced tissue remains a significant limitation across all VIGS systems [12]. This mosaicism can complicate phenotypic interpretation, particularly for quantitative traits. Host inserts may also interfere with viral spread, further reducing silencing efficiency. To address these issues, researchers should employ the construct design principles outlined in Table 2, particularly focusing on middle-gene fragments of optimal length without homopolymeric regions.

Library complexity and representation present additional challenges. Conventional oligo(dT)-primed cDNA libraries often contain predominantly short fragments and overrepresent 3' ends of transcripts, while underrepresenting 5' ends and low-abundance transcripts [12] [18]. Screening artifacts, such as false positives from spontaneous mutations or truncated cDNAs, further complicate interpretation. Yeast screens with human cDNA libraries have revealed significant proportions of non-functional clones, including mitochondrial hits, non-coding RNAs, and truncated cDNAs resulting from internal priming of genomic regions [18].

Optimization strategies include employing normalization techniques to equalize transcript representation, using high-fidelity reverse transcriptases to generate full-length cDNAs, and implementing rigorous bioinformatic screening to eliminate clones with potential off-target effects. For quantitative traits, statistical power can be improved by increasing replicate numbers and using quantitative PCR to verify silencing efficiency rather than relying solely on visual phenotypes. Recent advances in automation have also improved reproducibility and throughput, with automated workflows reducing hands-on time from 2 days to 9 hours while maintaining library quality [23].

Molecular Basis of TRV Vector Systems and Viral Suppressor Proteins

Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) has emerged as a powerful reverse genetics tool for rapid functional analysis of plant genes. Among various viral vectors developed for VIGS, the Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV) has gained prominence due to its ability to infect meristematic tissues and induce effective silencing with mild symptoms [24]. The molecular efficacy of TRV-based systems is significantly influenced by viral suppressor of RNA silencing (VSR) proteins, which naturally counteract host RNAi machinery. Recent research has focused on engineering these VSRs to enhance VIGS efficiency, particularly in recalcitrant species such as pepper and walnut [25] [24]. This application note examines the molecular basis of TRV vector systems and the strategic manipulation of VSR proteins, providing detailed protocols for optimizing VIGS construct design within the broader context of cDNA library preparation research.

The fundamental TRV system consists of two primary components: TRV1, containing genes for replication and movement, and TRV2, which serves as the vehicle for inserting target gene fragments [24]. When engineered to carry host gene sequences, TRV triggers sequence-specific mRNA degradation through the plant's endogenous RNA interference pathway. This system bypasses the need for stable transformation, enabling direct functional genomics studies even in non-model organisms. However, the effectiveness of standard TRV vectors varies significantly across plant species, tissues, and developmental stages, necessitating optimization through VSR protein engineering.

Molecular Mechanisms of Viral Suppressor Proteins

Structure-Function Relationships in VSR Proteins

Viral suppressor proteins employ diverse strategies to inhibit host RNA silencing pathways, with many VSRs exhibiting multiple, separable functional domains. The Cucumber Mosaic Virus 2b (C2b) protein represents a well-characterized VSR that demonstrates dual suppression activity—binding both long and short dsRNAs to inhibit RNA silencing while simultaneously disrupting secondary siRNA amplification through direct interaction with Argonaute (AGO) proteins [25]. Recent structure-function analyses have revealed that these activities can be spatially segregated within the protein architecture.

Critical research has demonstrated that the N-terminal region (1-61 aa) of C2b contains a dsRNA-binding domain, while a separate AGO-binding domain (37-94 aa) facilitates direct inhibition of AGO1 and AGO4 cleavage activities [26]. This modular organization enables targeted protein engineering to decouple local from systemic silencing suppression functions. Similar functional separations have been observed in other VSRs, including P19 protein, whose siRNA-binding capacity is distinct from its regulation of miR168-mediated AGO1 expression [25]. These structural insights provide the molecular foundation for rational design of enhanced VIGS vectors.

Cross-Viral Suppressor Interactions

Research across multiple virus families has revealed unexpected protein-protein interactions that fine-tune VSR activity. Studies demonstrate that viral coat proteins (CPs) can negatively regulate the RNA silencing suppression (RSS) activity of their cognate VSRs [26]. In Cucumoviruses (CMV, PSV) and Potyviruses (PPV), co-expression of CP with VSRs resulted in decreased RSS activity regardless of the origin of the two proteins, suggesting a universal role in modulating viral suppression potency [26].

Quantitative analysis revealed that PSV CP elicited the strongest negative effect on the RSS activity of all three tested VSRs (CMV 2b, PSV 2b, and PPV HC-Pro) [26]. This cross-regulation highlights the complex interplay between viral components and suggests that endogenous viral proteins may naturally temper VSR activity to maintain optimal infection dynamics without triggering extreme host defense responses.

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of Viral Coat Protein Effects on VSR Activity

| VSR Protein | Cognate CP Effect | Heterologous CP Effects | Experimental System |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMV 2b | Reduced RSS activity [26] | PSV CP: Strong reductionPPV CP: Moderate reduction | N. benthamiana transient assay |

| PSV 2b | Substantially impaired RSS [26] | CMV CP: Moderate reductionPPV CP: Moderate reduction | N. benthamiana transient assay |

| PPV HC-Pro | Reduced RSS activity [26] | CMV CP: Moderate reductionPSV CP: Strong reduction | N. benthamiana transient assay |

Engineering Enhanced TRV Systems Through VSR Modification

Structure-Guided Truncation of CMV 2b Protein

Recent research has demonstrated that strategic truncation of the C2b protein can enhance TRV-VIGS efficiency. A structure-guided approach generated C2bN43 and C2bC79 truncation variants that displayed compromised local RNA silencing suppression activity while maintaining systemic suppression capability [25]. This functional decoupling proved advantageous for VIGS applications, as the preserved systemic activity facilitated long-distance movement of recombinant TRV vectors while reduced local suppression potentiated silencing efficacy in systemically infected tissues.

When incorporated into TRV vectors (TRV-C2bN43), these modified suppressors significantly enhanced VIGS efficacy in pepper plants, particularly in reproductive tissues that are traditionally challenging targets for silencing approaches [25]. The engineered system successfully silenced an anther-specific MYB transcription factor (CaAN2), leading to coordinated downregulation of structural genes in the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway and abolished pigment accumulation—confirming both the technical efficacy and biological utility of this optimized system.

Quantitative Assessment of Enhanced TRV-VIGS Systems

The performance of TRV-C2bN43 was quantitatively compared to standard TRV systems across multiple parameters. Silencing efficiency was evaluated using the CaPDS (phytoene desaturase) marker gene, whose disruption causes photobleaching—a visible phenotype that enables rapid efficiency assessment [25]. The TRV-C2bN43 system demonstrated significantly improved silencing penetration in meristematic tissues and reproductive organs compared to conventional TRV vectors.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of TRV-VIGS Systems

| VIGS System | Silencing Efficiency | Tissue Penetration | Applications Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard TRV | Variable (5-40% across species) [24] | Limited in meristems and reproductive tissues [25] | N. benthamiana, tomato, some woody species [24] |

| TRV-C2bN43 | Significantly enhanced in pepper [25] | Strong in meristems and reproductive tissues [25] | Pepper anther pigmentation studies [25] |

| Walnut-Optimized TRV | Up to 48% in leaves [24] | Effective in leaf tissues, limited fruit application [24] | Walnut functional genomics [24] |

Application Protocols

Protocol: TRV-VIGS Implementation in Recalcitrant Species

The following protocol details TRV-VIGS implementation optimized for challenging plant species such as pepper and walnut, incorporating recent advancements in VSR engineering [25] [24].

Phase 1: Vector Construction

- TRV2 Vector Preparation: Amplify target gene fragment (250-368 bp) from cDNA using gene-specific primers with appropriate restriction sites [25].

- VSR Incorporation: For enhanced systems, clone truncated C2b variants (C2bN43) under PEBV subgenomic promoter into pTRV2 vector [25].

- Ligation and Transformation: Perform ligation using T4 DNA Ligase and transform into E. coli competent cells. Select positive clones using appropriate antibiotics [24].

Phase 2: Agrobacterium Preparation

- Strain Transformation: Introduce pTRV1, pTRV2-target, and pTRV2-VSR vectors into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 through electroporation or freeze-thaw method [24].

- Culture Conditions: Grow transformed Agrobacterium in YEP medium with appropriate antibiotics (kanamycin, rifampicin) at 28°C for 24-48 hours [24].

- Induction Medium Preparation: Harvest bacteria by centrifugation and resuspend in induction buffer (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl₂, 200 μM acetosyringone) to OD₆₀₀ = 1.0-1.5 [24]. Incubate for 3-4 hours at room temperature.

Phase 3: Plant Infiltration

- Plant Material Selection: Utilize 2-4 leaf stage seedlings for optimal susceptibility [24].

- Infiltration Methods:

- Post-Infiltration Conditions: Maintain plants at 20-22°C for 48-72 hours in low light conditions, then transfer to standard growth conditions (22-25°C, 16/8h light/dark) [25].

Phase 4: Silencing Validation

- Phenotypic Assessment: For visible markers like PDS, monitor photobleaching 2-4 weeks post-infiltration [25].

- Molecular Confirmation:

Protocol: VSR Activity Assay

This protocol enables quantitative assessment of VSR activity and its modulation by other viral proteins, such as coat proteins [26].

Step 1: Experimental Setup

- Construct Preparation: Clone VSR genes (CMV 2b, PSV 2b, PPV HC-Pro) and corresponding CP genes into binary expression vectors under 35S promoter [26].

- Agrobacterium Strains: Transform individual constructs into separate GV3101 strains with appropriate selection markers [26].

Step 2: Transient Expression in N. benthamiana

- Leaf Infiltration: Co-infiltrate GFP-expressing strain with test VSR strains at OD₆₀₀ = 0.5 each [26].

- Experimental Combinations: Include VSR alone, VSR + cognate CP, and VSR + heterologous CP combinations [26].

- Controls: Include GFP-only and empty vector controls on each leaf [26].

Step 3: Monitoring and Analysis

- Fluorescence Monitoring: Visualize GFP fluorescence under UV light at 2, 5, and 7 days post-agroinfiltration (dpa) [26].

- Protein Extraction: Harvest leaf discs at 5 dpa, extract proteins in sample buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 100 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl₂, 0.1% NP-40) [26].

- Western Blotting: Separate proteins on 10% SDS-PAGE, transfer to PVDF membrane, probe with anti-GFP primary antibody (1:5000 dilution) and appropriate secondary antibody [26].

- RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR: Extract total RNA, synthesize cDNA, and perform RT-qPCR for GFP mRNA levels using appropriate reference genes [26].

Step 4: Data Interpretation

- RSS Activity Calculation: Compare GFP fluorescence intensity and mRNA levels between VSR-expressing and control patches [26].

- CP Modulation Effect: Calculate percentage change in RSS activity when CP is co-expressed with VSR [26].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for TRV-VIGS and VSR Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| VIGS Vectors | pTRV1, pTRV2 | Basic TRV system components | [24] |

| Enhanced VIGS Vectors | pTRV2-C2bN43 | TRV with optimized viral suppressor | [25] |

| Agrobacterium Strains | GV3101 | Delivery of VIGS constructs to plants | [24] [25] |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Hifair IV Reverse Transcriptase | cDNA synthesis for library construction | [27] |

| DNA Ligase | T4 DNA Ligase | Adapter ligation in library prep | [27] |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | Hieff NGS PCR Master Mix | Library amplification with minimal bias | [27] |

| cDNA Library Prep Kits | Hieff NGS DNA Library Prep Kit | Construction of sequencing libraries | [27] |

| RNA Extraction Reagents | Trizol | Total RNA isolation from plant tissues | [25] |

| qPCR Master Mix | ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix | Quantitative assessment of silencing | [25] |

The strategic engineering of TRV vector systems through rational modification of viral suppressor proteins represents a significant advancement in plant functional genomics. The decoupling of local and systemic RNA silencing suppression activities in proteins like C2bN43 demonstrates how fundamental understanding of molecular mechanisms can drive practical improvements in research tools [25]. These optimized systems now enable efficient gene silencing in previously recalcitrant species and tissues, particularly reproductive organs that are essential for studying agronomically important traits.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on expanding the host range of optimized VIGS systems, particularly for economically important woody species where stable transformation remains challenging [24]. Additionally, the integration of VIGS with emerging technologies like CRISPR-based genome editing presents exciting opportunities for multiplexed gene function analysis [28]. The continued elucidation of molecular interactions between viral proteins, including the fine-tuning of VSR activity by coat proteins [26], will further refine these indispensable tools for plant biology research.

Critical Design Considerations for Effective Gene Silencing Constructs

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) has emerged as a powerful functional genomics tool for rapid gene function analysis in plants. This RNA interference (RNAi)-based mechanism exploits the plant's innate antiviral defense system, where recombinant viruses carrying host gene fragments trigger sequence-specific degradation of complementary mRNA targets [12]. VIGS offers significant advantages over stable transformation, including rapid implementation, applicability to species recalcitrant to genetic transformation, and the ability to silence genes in specific tissues without generating stable transgenic lines [1] [6]. The effectiveness of VIGS experiments, however, heavily depends on strategic construct design and optimized protocol implementation. This application note synthesizes critical design considerations and detailed methodologies for developing effective VIGS constructs, providing researchers with a framework for reliable gene silencing in plant systems.

Key Design Parameters for VIGS Constructs

Insert Sequence Considerations

Strategic selection of the insert sequence is paramount for successful gene silencing. Research indicates that not all cDNA fragments perform equally in triggering efficient silencing, with several parameters significantly influencing the outcome.

Table 1: Optimal Design Parameters for VIGS Inserts

| Design Parameter | Recommendation | Impact on Silencing Efficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Insert Length | 200–1300 base pairs (bp); ideal range: 400–500 bp [12] | Fragments below 200 bp show reduced efficiency; longer fragments within range perform well [12]. |

| Insert Position | Middle region of the cDNA coding sequence [12] | 5' and 3' end inserts perform more poorly compared to central regions [12]. |

| Sequence Composition | Avoid homopolymeric regions (e.g., poly(A) or poly(G) tails) [12] | Inclusion of a 24 bp poly(A) or poly(G) region reduces silencing efficiency [12]. |

| Sequence Specificity | Use tools like SGN VIGS Tool for specificity analysis [6] | Ensures the selected fragment has high similarity to the target gene and <40% similarity to other genes to minimize off-target effects [6]. |

The rationale for targeting the middle region of the cDNA and avoiding UTRs includes potentially higher sequence uniqueness and reduced regulatory element interference. Furthermore, using a solid-phase support cDNA synthesis method that yields fragments lacking poly(A) tails can enhance the quality of the resulting VIGS library, with one study reporting that 99.5% of cDNA inserts prepared this way lacked poly(A) tails [12].

Vector Systems and Delivery Methods

The choice of viral vector and delivery method significantly impacts silencing efficiency and tissue coverage. The Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV)-based system is widely adopted due to its broad host range and ability to spread efficiently throughout the plant, including meristematic tissues [1]. TRV typically consists of two modular vectors: pTRV1 (encoding replication and movement proteins) and pTRV2 (encoding the coat protein and the host gene insert) [1] [29].

For difficult-to-transform plants or recalcitrant tissues, Agrobacterium-mediated delivery is the most common method. Optimization of Agrobacterium strain, culture density (OD600), and the use of acetosyringone are critical steps. For instance, in Styrax japonicus, optimal silencing was achieved using an Agrobacterium OD600 of 0.5-1.0 with an acetosyringone concentration of 200 μmol·L⁻¹ [30]. In soybean, conventional infiltration methods (e.g., misting, leaf injection) often prove inefficient due to thick cuticles and dense trichomes. An optimized protocol using cotyledon node immersion in Agrobacterium suspensions for 20-30 minutes achieved a remarkable infection efficiency of over 80%, reaching up to 95% in some cultivars [1].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol I: Construct Assembly and Agrobacterium Preparation

This protocol details the steps for cloning a target gene fragment into a TRV vector and preparing Agrobacterium for inoculation.

Step 1: Vector Construction

- Amplify Target Fragment: Using high-fidelity DNA polymerase, amplify a 200-500 bp fragment from the middle region of the target gene's cDNA using gene-specific primers incorporating appropriate restriction enzyme sites (e.g., EcoRI, XhoI) [1] [6].

- Digest and Ligate: Digest both the purified PCR product and the pTRV2 vector (e.g., pYL279, pNC-TRV2) with the selected restriction enzymes. Purify the digested products and ligate them using standard molecular biology techniques [12] [1].

- Transform and Sequence: Transform the ligation product into E. coli (e.g., DH5α), select positive colonies on kanamycin (50 μg/mL) plates, and confirm the insert sequence by Sanger sequencing [29] [6].

Step 2: Agrobacterium Transformation and Culture

- Transform Agrobacterium: Introduce the confirmed recombinant pTRV2 plasmid and the pTRV1 plasmid into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 (containing the helper plasmid pJIC Sa_Rep) via electroporation or freeze-thaw transformation. Select on plates containing kanamycin (50 μg/mL) and rifampicin (50 μg/mL) [29] [6].

- Prepare Agrobacterium Culture: Inoculate a single positive colony into YEB liquid medium containing antibiotics (kanamycin and rifampicin) and 200 μmol·L⁻¹ acetosyringone. Incubate at 28°C with shaking (200-240 rpm) for 24-48 hours until the OD600 reaches 0.9-1.0 [6].

- Harvest and Resuspend: Pellet the bacteria by centrifugation (5000 rpm for 15 min). Resuspend the pellet in an induction buffer (10 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM MES, pH 5.6, 200 μmol·L⁻¹ acetosyringone) to a final OD600 of 0.5-2.0, depending on the plant species and inoculation method. Incubate the resuspended culture at room temperature for 3-6 hours before use [30] [6].

- Prepare Inoculum: Mix the induced pTRV1 and pTRV2 (with insert) Agrobacterium cultures in a 1:1 ratio [1].

Protocol II: Plant Inoculation for Recalcitrant Tissues

This optimized protocol for challenging plant materials like soybean and woody capsules uses a cotyledon node immersion method.

Step 1: Plant Material Preparation

- Surface-sterilize soybean seeds or other explants.

- Soak sterilized seeds in sterile water until swollen.

- Prepare half-seed explants by longitudinally bisecting the swollen seeds [1].

Step 2: Inoculation and Plant Care

- Immerse the fresh half-seed explants or other target tissues (e.g., pericarp cuttings) in the prepared Agrobacterium inoculum for 20-30 minutes with gentle agitation [1] [6].

- Blot-dry the explants and co-cultivate them on sterile filter paper or tissue culture medium in the dark at 22-25°C for 2-3 days.

- Transfer plants to a growth chamber or greenhouse with controlled conditions (e.g., 22-25°C, 16-hour light/8-hour dark cycle).

- Monitor for silencing phenotypes, such as photobleaching for the PDS gene, which typically appears 2-4 weeks post-inoculation (dpi) [1].

Workflow Visualization and Reagent Solutions

VIGS Experimental Workflow

The diagram below outlines the key stages of a VIGS experiment, from design to analysis.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for TRV-based VIGS Experiments

| Reagent/Component | Function/Purpose | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TRV Vectors | Binary viral vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated delivery. | pTRV1 (RNA1 component), pTRV2 (RNA2 with MCS for insert) [1] [29]. pNC-TRV2 is a modified version [6]. |

| Agrobacterium Strain | Delivers T-DNA containing the VIGS construct into plant cells. | GV3101 is widely recommended for its high transformation efficiency and faster growth [29] [6]. |

| Helper Plasmid | Enables replication of pGreen-based vectors (e.g., pgR106/107) in Agrobacterium. | pJIC Sa_Rep (TetR) [29]. |

| Antibiotics | Selection for bacteria containing the plasmids. | Kanamycin (for pTRV2/pGreen), Rifampicin (for GV3101), Tetracycline (for pJIC Sa_Rep) [29] [6]. |

| Induction Agents | Activates Agrobacterium vir genes for efficient T-DNA transfer. | Acetosyringone (200 μmol·L⁻¹), MES buffer (pH 5.6) [30] [6]. |

| Plant Material | Target species for gene silencing. | Nicotiana benthamiana (model), Soybean, Camellia drupifera. Optimal developmental stage is critical [1] [6]. |

Effective VIGS construct design hinges on a combination of strategic sequence selection and optimized experimental protocols. Adherence to the outlined parameters—specifically, using inserts of 200-500 bp derived from the middle of the coding sequence, avoiding homopolymeric regions, and employing species-appropriate delivery methods—provides a robust foundation for successful gene silencing. The detailed protocols and reagent solutions presented here offer researchers a practical guide to implement and troubleshoot VIGS in both model and recalcitrant plant species, thereby accelerating functional gene validation in plant genomics and biotechnology research.

Step-by-Step Protocols for VIGS Construct Assembly and Library Preparation

Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) has emerged as a powerful reverse genetics tool for rapid functional analysis of plant genes. The efficiency of VIGS is critically dependent on the strategic design of the cDNA inserts incorporated into viral vectors. This application note synthesizes evidence-based guidelines for optimizing cDNA insert length, positional selection within the target transcript, and sequence composition to maximize silencing efficacy. We present a detailed protocol for the tobacco rattle virus (TRV)-based system, alongside supporting data from multiple plant species, providing researchers with a framework for designing effective VIGS constructs for functional genomics studies.

Virus-induced gene silencing exploits the plant's innate RNA-based antiviral defense mechanism for post-transcriptional gene silencing [12] [31]. When a recombinant virus containing host-derived sequences infects a plant, the resulting double-stranded RNA intermediates trigger sequence-specific degradation of homologous endogenous mRNAs [32]. The effectiveness of this technology hinges on the molecular properties of the inserted cDNA fragments, which significantly impact silencing efficiency through their influence on viral replication, movement, and siRNA generation.

Key Design Parameters for VIGS Inserts

Insert Length Optimization

Systematic investigation of cDNA fragment length using the phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene in Nicotiana benthamiana with TRV vectors has established clear guidelines for optimal insert sizes.

Table 1: Effect of Insert Length on VIGS Efficiency in TRV Vectors

| Insert Length Range | Silencing Efficiency | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| 54-103 bp | Inefficient silencing | Minimal photobleaching observed in N. benthamiana |

| 192-1304 bp | High efficiency silencing | Significant photobleaching; reduced chlorophyll a levels |

| ~100 nt | Optimal for BMV vectors in wheat | Extended silencing duration and higher efficiency |

Data from Plant Methods (2008) demonstrates that NbPDS inserts between 192 bp and 1304 bp led to efficient silencing as determined by analysis of leaf chlorophyll a levels [12] [33]. Notably, different viral vectors may have distinct optimal size ranges, with the Brome mosaic virus (BMV)-based system showing superior performance with approximately 100 nucleotide inserts in hexaploid wheat [34].

Positional Effects Within cDNA

The region of the target cDNA from which fragments are derived significantly impacts silencing efficiency. Research on NbPDS silencing revealed that fragments originating from the middle regions of the coding sequence consistently outperform those from the 5' or 3' ends [12]. This positional effect may relate to mRNA secondary structure, accessibility of target sites for RISC complex binding, or the distribution of effective siRNA generation regions along the transcript.

Sequence Composition Considerations

Homopolymeric regions, particularly poly(A) and poly(G) tracts of 24 base pairs, substantially reduce silencing efficiency in TRV vectors [12] [33]. These sequences potentially interfere with viral replication or movement, thereby diminishing the systemic spread of silencing signals. Additional sequence considerations include:

- Avoidance of extensive secondary structure: Highly stable secondary structures may impede viral replication

- Off-target potential: Bioinformatics analysis (e.g., siRNA scan) should be performed to minimize unintended silencing of non-target genes [35]

- Gene family specificity: For targeting specific members of gene families, incorporation of 5' or 3' untranslated regions (UTRs) can enhance specificity [35]

Experimental Protocol: TRV-Mediated VIGS in Nicotiana benthamiana

Vector Selection and Preparation

The TRV-based VIGS system employs two separate T-DNA vectors:

- TRV-RNA1 (pYL192): Encodes replicase and movement proteins

- TRV-RNA2 (pYL279): Contains the coat protein and serves as the insertion site for target gene fragments [12]

Advanced vector modifications include:

- Gateway-compatible vectors (e.g., pTRV2-GW) for high-throughput cloning [31]

- Ligation-independent cloning (LIC) vectors to simplify insert incorporation [31]

- Fluorescent protein fusions (e.g., TRV-GFP) for visual tracking of viral spread [31]

Insert Selection and Clone Construction

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Target Fragment Amplification

- Design primers to amplify 200-500 bp fragments from the middle region of the target coding sequence

- Incorporate appropriate recombination sites (e.g., attB1/attB2 for Gateway cloning)

- Verify fragment size and sequence fidelity by agarose gel electrophoresis and sequencing

Gateway Cloning into TRV Vector

- Perform BP recombination between attB-flanked PCR product and attP-containing donor vector

- Conduct LR recombination between entry clone and pTRV2-Destination vector

- Transform resulting expression clone into E. coli and select on appropriate antibiotics

Agrobacterium Preparation

- Transform confirmed TRV constructs into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101

- Initiate 3 mL starter cultures in LB with appropriate antibiotics (e.g., 50 μg/mL kanamycin, 25 μg/mL gentamycin) [35]

- Use starter culture to inoculate 50-100 mL of induction media (LB with antibiotics, 10 mM MES, 20 μM acetosyringone)

- Harvest bacteria at OD550 = 0.8-1.2 by centrifugation (3000 × g, 15 min)

- Resuspend pellet in infiltration buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES, 200 μM acetosyringone) to final OD550 = 0.5-2.0

- Incubate suspension at room temperature for 3-6 hours before infiltration

Plant Infiltration and Monitoring

Infiltration Methodology:

- Plant Material: Use 4-week-old N. benthamiana plants with 4-6 true leaves [12]

- Inoculation: Combine TRV1 and TRV2 Agrobacterium cultures in 1:1 ratio

- Infiltration Technique:

- Use needleless syringe to infiltrate bacterial suspension through abaxial leaf surface

- Apply gentle pressure against the leaf while supporting the opposite side

- Target multiple leaves per plant to ensure successful infection

- Post-Inoculation Conditions:

- Maintain plants under high humidity for 24-48 hours

- Grow at 20-25°C with 16-hour light/8-hour dark photoperiod

- Phenotype Monitoring:

- Initial silencing symptoms typically appear 1-2 weeks post-infiltration

- Maximum silencing efficiency observed at 3-4 weeks

- Document phenotypes with photography and collect tissue for molecular analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for TRV-Mediated VIGS Experiments