Navigating Junctional Diversity in NBS Gene Analysis: Methods, Challenges, and Clinical Translation

The analysis of Nucleotide-Binding Site (NBS) genes is fundamental to understanding disease resistance mechanisms in biomedical research.

Navigating Junctional Diversity in NBS Gene Analysis: Methods, Challenges, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

The analysis of Nucleotide-Binding Site (NBS) genes is fundamental to understanding disease resistance mechanisms in biomedical research. However, the extensive junctional diversity—encompassing sequence variability, domain architecture, and evolutionary divergence—presents significant challenges in accurate gene annotation, functional prediction, and diagnostic application. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to address these complexities. We explore the foundational principles of NBS gene diversity, detail advanced methodological approaches for robust analysis, present strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls, and establish validation protocols to ensure biological relevance. By integrating cutting-edge genomic technologies, statistical genetics, and functional assays, this guide aims to enhance the precision of NBS gene studies and accelerate their translation into therapeutic and diagnostic innovations.

Decoding NBS Gene Complexity: Origins and Impact of Junctional Diversity

Junctional diversity refers to the extensive variation created at the junctions of gene segments during recombination and mutational processes in biological systems. This phenomenon is crucial for generating the vast repertoires of antigen receptors in vertebrates and disease resistance genes in plants. In immunological contexts, junctional diversity results from processing of coding ends before ligation, including both base additions and nucleotide loss during V(D)J recombination [1]. This processing accounts for most immunoglobulin and T cell receptor repertoire diversity, allowing recognition of countless pathogens [1].

In plant systems, junctional diversity manifests through domain architecture variations in nucleotide-binding site (NBS) genes, which constitute the largest family of plant resistance (R) genes. These NBS-containing genes exhibit remarkable structural diversity through combinations of various protein domains, creating different binding specificities against pathogens [2] [3]. The NBS domain itself can bind ATP/GTP, facilitating phosphorylation that transmits disease resistance signals downstream in plant immune pathways [3].

Key Concepts and Terminology

Core Definitions

- Junctional Diversity: The molecular variation generated at the junctions of recombining gene segments through nucleotide addition and deletion processes, significantly expanding receptor diversity [1].

- N-Region Diversity: Addition of non-templated nucleotides at coding joints by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) [1] [4].

- Coding Joint: Formed by joining gene coding segments after recombination signal sequence cleavage [1].

- Signal Joint: Created by joining recombination signal sequences during V(D)J recombination [1].

- NBS-LRR Genes: Nucleotide-binding site leucine-rich repeat genes, the largest family of plant resistance genes providing pathogen recognition capabilities [3] [5].

Molecular Mechanisms Creating Junctional Diversity

Research Reagent Solutions for Junctional Diversity Studies

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Junctional Diversity Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Experimental Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer Sets | Degenerate primers for P-loop, Kinase-2, GLPL motifs [6] | Amplification of NBS domains from genomic DNA | Design degeneracy to match sequence diversity; 16 primers can cover most R genes [6] |

| HMM Profiles | NB-ARC domain (PF00931) [3] [7] [5] | Identification of NBS-containing genes in genomes | Use E-value < 1.0 for initial screening; verify with additional domain analysis [3] |

| Cloning Systems | Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) vectors [2] [5] | Functional validation of NBS-LRR gene function | Enables rapid testing of gene function without stable transformation [5] |

| Sequence Analysis Tools | MEME Suite, HMMER, OrthoFinder [3] | Identification of conserved motifs and evolutionary relationships | Motif width 6-50 amino acids; bootstrap value 1000 for phylogenetic trees [3] |

| Structural Analysis | Coiled-coil prediction tools (e.g., Coils) [3] | Identification of CC domains in NBS-LRR proteins | Threshold value of 0.5; CC domains not always identified by Pfam searches [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Junctional Diversity Analysis

Genome-Wide Identification of NBS-LRR Genes

Purpose: To systematically identify and classify NBS-containing resistance genes across plant genomes [3] [5].

Methodology:

- Sequence Retrieval: Download genome sequence and annotation files from public databases (NCBI, Phytozome, Plaza) [2].

- HMMER Search: Perform HMMsearch using NB-ARC domain (PF00931) with E-value < 1.0 [3] [5]:

- Domain Verification: Confirm NBS domain presence using Pfam database with E-value threshold of 10^-4 [3].

- Classification: Identify additional domains (TIR, CC, RPW8, LRR) using NCBI CDD and coiled-coil prediction tools [3].

- Manual Curation: Remove redundant genes and verify domain architecture through multiple databases.

Troubleshooting Tip: CC domains may not be detected by standard Pfam searches; use specialized coiled-coil prediction tools with threshold 0.5 [3].

NBS Profiling for Resistance Gene Allele Discovery

Purpose: To capture sequence diversity in NBS domains across multiple cultivars or accessions [6].

Methodology:

- Primer Design: Design degenerate primers complementary to conserved P-loop, Kinase-2, and GLPL motifs within NBS domains [6].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify NBS tags (200-480 bp fragments) from genomic DNA using multiple primer combinations.

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Sequence amplicons using Illumina platforms.

- Read Mapping: Map NBS tags to reference genome, allowing for detection of polymorphisms.

- Variant Analysis: Identify single nucleotide polymorphisms and haplotypes across samples.

Technical Note: 16 carefully designed primers can cover virtually all R genes carrying at least one of the three NBS domain-specific motifs [6].

Functional Validation Using Virus-Induced Gene Silencing

Purpose: To confirm the role of specific NBS-LRR genes in disease resistance [2] [5].

Methodology:

- Candidate Gene Selection: Identify NBS-LRR genes with differential expression in resistant vs. susceptible varieties.

- VIGS Construct Design: Clone 200-300 bp fragment of target gene into TRV-based silencing vector.

- Plant Infiltration: Agro-infiltrate silencing construct into cotyledons or true leaves.

- Pathogen Challenge: Inoculate silenced plants with target pathogen after silencing establishment (typically 2-3 weeks).

- Phenotypic Assessment: Monitor disease symptoms, measure pathogen biomass, and document hypersensitive responses.

- Molecular Confirmation: Verify gene silencing efficiency through qRT-PCR.

Application Example: Silencing of GaNBS (OG2) in resistant cotton demonstrated its role in virus resistance against cotton leaf curl disease [2].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Technical Troubleshooting

Q: Why do my degenerate primers fail to amplify expected NBS domains? A: Optimize primer degeneracy based on target species. For potato, 16 primers covering P-loop, Kinase-2 and GLPL motifs successfully amplified nearly all NBS domains [6]. Validate primer functionality through initial PCR on genomic DNA before high-throughput application.

Q: How can I distinguish between functional and non-functional NBS-LRR genes? A: Analyze for intact open reading frames and conserved motif structure. Functional NBS domains typically contain eight conserved motifs with specific order and amino acid conservation [3]. Combine sequence analysis with expression studies - functional genes often show induction upon pathogen challenge [5].

Q: What is the typical number of NBS-LRR genes expected in a plant genome? A: This varies significantly by species. Akebia trifoliata has 73 NBS genes [3], Vernicia fordii has 90 [5], while tobacco has 156 NBS-LRR homologs [7]. The number correlates with genome size and evolutionary history rather than taxonomic classification.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Q: How do I handle the mapping of NBS tags when working with non-reference genotypes? A: Be aware that mapping inaccuracies can occur due to differences between cultivars and the reference genome, coupled with high NBS domain sequence similarity. This may yield more than the possible 4 alleles per domain in tetraploid species, indicating potential locus intermixing [6]. Use stringent mapping parameters and validate with manual inspection.

Q: What criteria should I use to classify NBS-LRR genes into subfamilies? A: Use a hierarchical approach:

- Identify N-terminal domain (TIR, CC, RPW8, or none)

- Confirm NBS domain integrity

- Detect C-terminal LRR presence

- Classify as TNL, CNL, RNL, TN, CN, or N-type based on combination [7]

Q: How can I identify candidate NBS-LRR genes for specific disease resistance? A: Look for orthologous gene pairs between resistant and susceptible varieties that show distinct expression patterns. For example, Vf11G0978-Vm019719 pair where the resistant ortholog shows upregulated expression during infection while susceptible counterpart does not [5].

Advanced Analysis Techniques

Evolutionary Analysis of NBS Gene Family

Methodology:

- Orthogroup Identification: Use OrthoFinder v2.5.1 with DIAMOND for sequence similarity searches and MCL clustering [2].

- Phylogenetic Construction: Employ maximum likelihood algorithm in FastTreeMP with 1000 bootstrap replicates [2].

- Duplication Analysis: Identify tandem and dispersed duplications as primary forces for NBS expansion [3].

Table 2: NBS-LRR Gene Distribution Across Plant Species

| Plant Species | Total NBS Genes | TNL | CNL | RNL | Other | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akebia trifoliata | 73 | 19 | 50 | 4 | - | [3] |

| Vernicia fordii | 90 | 0 | 12 (CNL) | - | 78 (Other NBS) | [5] |

| Vernicia montana | 149 | 3 (TNL) | 9 (CNL) | - | 137 (Other NBS) | [5] |

| Nicotiana benthamiana | 156 | 5 | 25 | 4 (RPW8) | 122 (Other) | [7] |

| Common Potato | 587-755 | Varies | Varies | Varies | Varies | [6] |

Expression Analysis and Regulatory Elements

Methodology:

- RNA-seq Data Collection: Retrieve FPKM values from specialized databases (CottonFGD, IPF database) [2].

- Expression Categorization: Group expression data into tissue-specific, abiotic stress, and biotic stress responses.

- Cis-Element Analysis: Identify regulatory elements in promoter regions (1500 bp upstream) using PlantCARE database [7].

- Co-expression Networks: Construct networks to identify regulatory relationships (e.g., VmWRKY64 activating Vm019719) [5].

Nucleotide-binding site (NBS) genes constitute one of the most critical and dynamically evolving gene families in plants, encoding key receptors for pathogen detection and disease resistance. These genes, particularly those belonging to the NBS-LRR (leucine-rich repeat) class, are central to the plant immune system, enabling recognition of diverse pathogens through effector-triggered immunity. The remarkable diversity of NBS genes presents both a scientific opportunity and a technical challenge for researchers. This technical support center addresses the experimental complexities arising from the junctional diversity of NBS genes, focusing specifically on how whole-genome duplication (WGD) and tandem duplication events have driven their expansion and diversification across plant lineages.

The evolutionary mechanisms underlying NBS gene expansion are not merely academic concerns—they directly impact experimental design, data interpretation, and technical troubleshooting in molecular biology research. Studies across multiple plant species have revealed that NBS genes evolve at least 1.5-fold faster at synonymous sites and approximately 2.3-fold faster at nonsynonymous sites compared to flanking non-NBS genes, with gene loss occurring approximately twice as rapidly [8]. This rapid evolutionary dynamic, driven by the combined effects of diversifying selection and frequent sequence exchanges, creates substantial technical challenges for researchers working with these genes [8].

Table 1: Evolutionary Dynamics of NBS Genes Across Plant Species

| Evolutionary Parameter | Comparative Rate | Experimental Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Synonymous substitution rate | ~1.5x higher than non-NBS genes | Complicates primer design and cross-species PCR amplification |

| Nonsynonymous substitution rate | ~2.3x higher than non-NBS genes | Affects protein structure-function analyses and antibody development |

| Gene loss rate | ~2x faster than non-NBS genes | Leads to presence-absence polymorphisms that complicate genotyping |

| Tandem duplication prevalence | Major expansion mechanism in soybean and Arabidopsis [8] [9] | Creates complex clusters requiring specialized assembly approaches |

| Segmental duplication contribution | Significant in asparagus and soybean [10] [8] | Necessitates whole-genome context for proper annotation |

FAQs: Troubleshooting NBS Gene Analysis

How can I accurately identify and annotate NBS genes in a newly sequenced plant genome?

Challenge: Researchers frequently report incomplete identification of NBS genes, particularly from tandemly duplicated clusters, leading to fragmented assemblies and inaccurate gene models.

Solution: Implement a reiterative BLAST and domain-based identification protocol:

Initial Homology Search: Use BLASTP with known NBS proteins from closely related species (e.g., Allium sativum for monocots) with cutoff values of 30% identity, 30% query coverage, and E-value < 1×10⁻³⁰ [10].

Domain Validation: Confirm NBS domains using NCBI's Conserved Domain Database (CDD) with E-value < 0.01 [10].

Motif Identification: Identify TIR, CC, or LRR motifs using Pfam database, SMART protein motif analysis, and COILS program (threshold 0.9) [10].

Iterative Searching: Use newly identified sequences as subsequent queries until no additional members are detected [10].

Troubleshooting Tip: If encountering high false-negative rates in complex genomes, supplement with HMMER searches using PfamScan and the Pfam-A.hmm model with default e-value (1.1e-50) [2]. This approach identified 12,820 NBS-domain-containing genes across 34 species in a recent study, capturing both classical and species-specific structural patterns [2].

What strategies effectively resolve complex NBS gene clusters arising from tandem duplications?

Challenge: Tandemly duplicated NBS genes exhibit high sequence similarity, causing assembly fragmentation and misassembly that obscures true gene copy number and organization.

Solution: Employ a multi-platform sequencing approach:

Long-Read Sequencing: Utilize PacBio or Nanopore sequencing to span repetitive regions and resolve complex clusters where ~50% of NBS genes reside in clusters [10].

Cluster Definition Parameters: Define clusters using established criteria: minimum 2 genes, intergene distance <200 kb, and no more than 8 non-NBS genes between neighboring NBS-LRR genes [10].

Gene Family Classification: Apply the coverage/identity threshold method: aligned region >70% of longer gene with >70% identity [10].

Expression Validation: Use transcriptome sequencing to confirm transcribed genes and correct annotation boundaries.

Troubleshooting Tip: For persistent gaps in cluster regions, employ chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) to scaffold clusters and validate physical organization. In asparagus, chromosome 6 was found to be significantly NBS-enriched, with one cluster hosting 10% of all NBS genes [10].

How do I distinguish between functional NBS genes and pseudogenes?

Challenge: NBS gene families contain numerous pseudogenes that complicate functional analyses and lead to false positives in resistance gene discovery.

Solution: Implement a multi-tiered filtering strategy:

Transcriptional Evidence: Analyze RNA-seq data from multiple tissues and stress conditions to confirm expression [2] [10].

Open Reading Frame Analysis: Verify complete ORFs without premature stop codons or frameshift mutations.

Domain Integrity: Confirm presence and order of essential domains (NBS, LRR, TIR/CC) using Pfam and SMART.

Evolutionary Conservation: Assess selection pressures—functional genes typically show signatures of positive selection rather than neutral evolution.

Troubleshooting Tip: Be aware that some pseudogenes may be transcribed and even regulated by miRNAs. In Gossypium hirsutum, genetic variation analysis identified 6,583 unique variants in tolerant accessions versus 5,173 in susceptible ones, highlighting the importance of functional validation [2].

What methods reliably detect recent versus ancient duplication events in NBS genes?

Challenge: Determining the timing and mechanism of duplication events is essential for understanding NBS gene evolution but requires specialized analytical approaches.

Solution: Apply phylogenetic and synteny-based methods:

Sequence Similarity Thresholds: Estimate temporal differences using proportion of multigene families across 80-90% similarity/coverage thresholds [10].

Synonymous Substitution Rates: Calculate Ks values for paralogous pairs—lower Ks values indicate more recent duplications.

Synteny Analysis: Identify segmental duplications by comparing genomic regions flanking NBS genes (15 genes on each side) and detecting >5 syntenic gene pairs with E-value < 1×10⁻¹⁰ [10].

Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Construct gene trees using maximum likelihood methods based on NBS domain sequences (from P-loop to MHDV) [10].

Troubleshooting Tip: For recent tandem duplications, expect to find significant sequence exchanges coupled with positive selection, as observed in most tandem-duplicated NBS gene families in soybean [8].

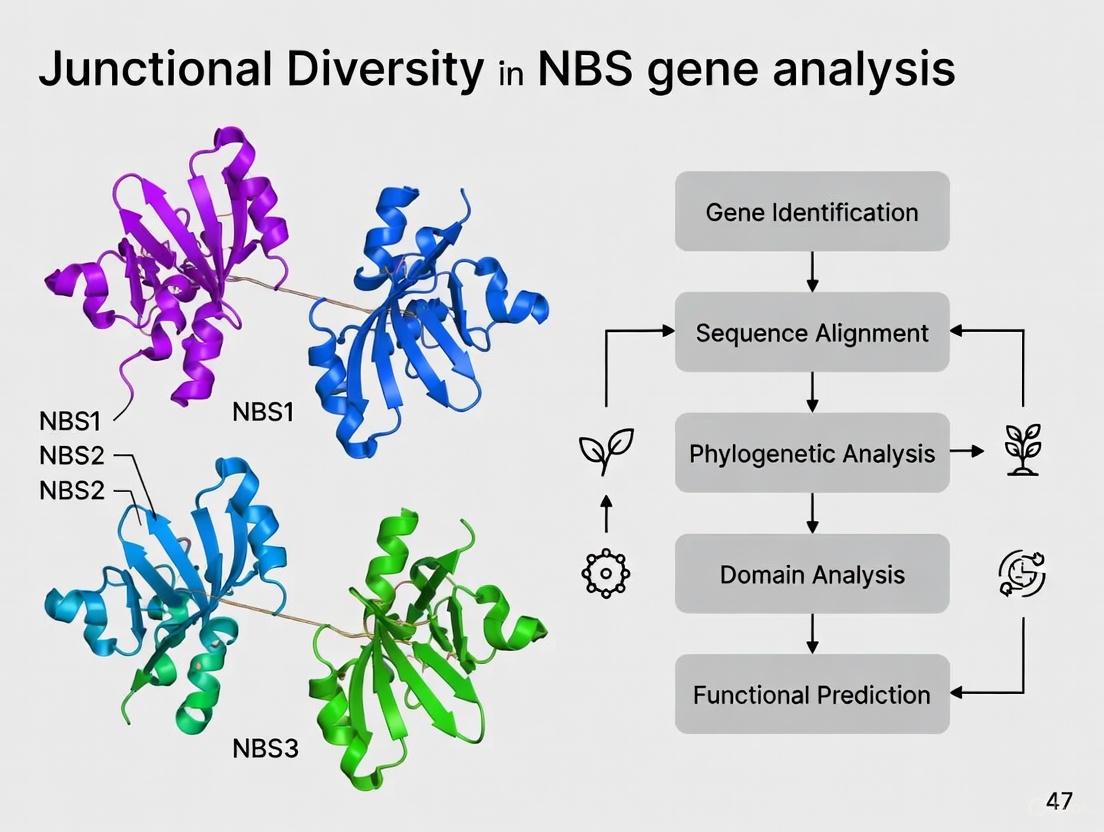

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for comprehensive NBS gene analysis, highlighting key stages where specific troubleshooting approaches are essential.

Experimental Protocols for NBS Gene Characterization

Orthogroup Analysis and Evolutionary Diversification

Purpose: To classify NBS genes into evolutionarily meaningful groups and trace their diversification across species.

Methodology:

- Sequence Collection: Compile NBS protein sequences from species of interest.

- Orthogroup Delineation: Use OrthoFinder v2.5.1 with DIAMOND for sequence similarity searches and MCL clustering algorithm [2].

- Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Perform multiple sequence alignment with MAFFT 7.0 and construct gene trees using maximum likelihood algorithm in FastTreeMP with 1000 bootstrap replicates [2].

- Orthogroup Classification: Identify core (conserved across species) and unique (species-specific) orthogroups.

Technical Notes: This approach identified 603 orthogroups with both core (OG0, OG1, OG2) and unique (OG80, OG82) orthogroups showing tandem duplications in a recent pan-species analysis [2]. Expression profiling revealed putative upregulation of OG2, OG6, and OG15 under various biotic and abiotic stresses [2].

Expression Profiling Under Stress Conditions

Purpose: To link specific NBS genes to stress responses and identify candidates for functional validation.

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Retrieve RNA-seq data from public databases (IPF, CottonFGD, CottonGen) or generate new data [2].

- Data Categorization: Organize expression data into three types: (1) tissue-specific, (2) abiotic stress-specific, and (3) biotic stress-specific.

- FPKM Extraction: Obtain FPKM values using gene accessions as query IDs.

- Differential Analysis: Compare expression between susceptible and tolerant genotypes under stress conditions.

Technical Notes: In cotton, this approach identified differential NBS expression between Coker 312 (susceptible) and Mac7 (tolerant) accessions in response to cotton leaf curl disease [2].

Functional Validation via Virus-Induced Gene Silencing

Purpose: To confirm the functional role of candidate NBS genes in disease resistance.

Methodology:

- Candidate Selection: Choose NBS genes with stress-responsive expression patterns.

- VIGS Construct Design: Design TRV-based silencing constructs targeting candidate genes.

- Plant Inoculation: Infiltrate plants with Agrobacterium containing VIGS constructs.

- Phenotypic Assessment: Challenge silenced plants with pathogens and quantify disease symptoms.

- Molecular Verification: Confirm gene silencing and measure pathogen titers.

Technical Notes: Silencing of GaNBS (OG2) in resistant cotton demonstrated its putative role in virus tittering, validating its function in disease resistance [2].

Table 2: NBS Gene Duplication Patterns Across Plant Species

| Plant Species | Total NBS Genes | Tandem Duplication | Segmental Duplication | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Not specified | Major driver for gene family expansion [9] | Contributes to gene family evolution [9] | [9] |

| Soybean (Glycine max) | Not specified | More abundant than segmental duplicates [8] | Revealed by syntenic homoeologs [8] | [8] |

| Garden asparagus | 68 proteins (49 loci) | Present (specific clusters) | Present (across multiple chromosomes) | [10] |

| Multiple species (34 plants) | 12,820 genes | Tandem duplications in orthogroups | Inferred from phylogenetic patterns | [2] |

Research Reagent Solutions for NBS Gene Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for NBS Gene Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Specific Application | Function in NBS Research | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| OrthoFinder | Evolutionary analysis | Discerns orthogroups and evolutionary relationships | [2] |

| MEME Suite | Motif discovery | Identifies conserved protein motifs in NBS genes | [10] |

| Pfam/ SMART databases | Domain architecture analysis | Classifies NBS genes based on domain composition | [2] [10] |

| NCBI CDD | Domain verification | Validates NBS domain presence with statistical support | [10] |

| MEGA software | Phylogenetic reconstruction | Builds evolutionary trees of NBS gene families | [10] |

| VIGS vectors | Functional validation | Tests disease resistance function of candidate NBS genes | [2] |

Diagram 2: Characteristics and outcomes of tandem versus segmental duplication mechanisms in NBS gene evolution, highlighting their distinct experimental implications.

Advanced Technical Considerations

miRNA Regulation of NBS Genes

The expansion and evolution of NBS genes is intricately linked to their regulation by miRNAs. At least eight families of miRNAs are known to target NBS-LRRs, typically binding to conserved regions like the P-loop motif [11]. This regulatory relationship represents an important co-evolutionary system that balances the benefits and costs of maintaining large NBS-LRR repertoires [11]. When designing functional studies, researchers should consider that:

- miRNAs typically target highly duplicated NBS-LRRs, while heterogeneous NBS-LRRs are rarely targeted [11].

- Duplicated NBS-LRRs periodically give birth to new miRNAs, with most targeting the same conserved protein motifs [11].

- Nucleotide diversity in the wobble position of codons in the target site drives miRNA diversification [11].

Evolutionary Rate Variation Among NBS Subclasses

Not all NBS genes evolve at the same rate, creating additional experimental considerations. TIR-NBS-LRR genes (TNLs) exhibit higher nucleotide substitution rates than non-TNLs, indicating distinct evolutionary patterns [8]. This differential evolution affects primer design, phylogenetic analysis, and functional inference. Researchers should:

- Subclassify NBS genes before evolutionary analysis

- Use subclass-specific evolutionary rate models

- Consider distinct conservation patterns when designing cross-species experiments

The junctional diversity of NBS genes, driven by the complementary forces of whole-genome and tandem duplication events, represents both a challenge and opportunity for plant disease resistance research. The troubleshooting guides and experimental protocols provided here address the most common technical hurdles researchers face when working with these dynamically evolving gene families. By implementing these standardized approaches—from accurate gene identification and cluster resolution to functional validation and evolutionary analysis—researchers can more effectively navigate the complexity of NBS gene families and advance our understanding of plant immunity mechanisms.

The continued refinement of these methodologies, particularly through the integration of long-read sequencing, multi-omics approaches, and advanced bioinformatics, will further enhance our ability to decipher the evolutionary drivers of NBS expansion and harness these genes for crop improvement. As evidenced by recent studies in asparagus, soybean, cotton, and multiple other species, the strategic application of these technical solutions enables meaningful progress despite the inherent challenges of working with these rapidly evolving, duplication-rich genes.

Nucleotide-binding site (NBS) genes constitute the largest and most crucial family of plant disease resistance (R) genes, playing a vital role in pathogen recognition and defense activation. Your research on their structural classification must account for significant junctional diversity—variations in domain architecture, gene structure, and sequence motifs that arise from evolutionary processes like tandem duplications, domain shuffling, and selective pressures. This diversity presents both challenges in consistent classification and opportunities for understanding plant-pathogen co-evolution.

The following sections provide a comprehensive technical framework to support your experiments, from basic classification to advanced functional characterization, with special attention to troubleshooting common issues encountered when handling this gene family's inherent diversity.

Core Concepts: Classical and Species-Specific NBS Architectures

What are the primary structural classes of NBS genes?

NBS genes are primarily classified based on their protein domain architecture. The classical classification system has been established through comparative genomic studies across multiple plant species [12] [13] [14].

Table 1: Classical Structural Classification of NBS Genes

| Category | Subfamily | Domain Architecture | Key Features | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical NBS-LRR | TNL | TIR-NBS-LRR | Contains TIR domain at N-terminus | Pathogen recognition, signal transduction |

| CNL | CC-NBS-LRR | Contains coiled-coil domain at N-terminus | Pathogen recognition, signal transduction | |

| RNL | RPW8-NBS-LRR | Contains RPW8 domain at N-terminus | Defense signal transduction | |

| Irregular NBS | TN | TIR-NBS | Lacks LRR domain | Regulatory or adapter functions |

| CN | CC-NBS | Lacks LRR domain | Regulatory or adapter functions | |

| N | NBS | Contains only NBS domain | Regulatory or adapter functions |

What species-specific architectural variations should I expect?

Beyond classical architectures, your research will encounter species-specific structural patterns that reflect lineage-specific adaptations. Recent pan-genomic studies reveal that NBS genes exhibit significant presence-absence variation (PAV), distinguishing conserved "core" subgroups from highly variable "adaptive" subgroups [15].

In pepper (Capsicum annuum), researchers identified 252 NBS-LRR genes with unusual distribution: 248 nTNLs (non-TIR NBS-LRR) and only 4 TNLs, with 200 genes lacking both CC and TIR domains [13]. This represents a dramatic shift from the typical distribution observed in model plants like Arabidopsis.

In Akebia trifoliata, the NBS gene family is remarkably small with only 73 members, containing 50 CNL, 19 TNL, and 4 RNL genes [16]. This compact repertoire suggests species-specific evolutionary constraints.

Orchids demonstrate another pattern, with complete absence of TNL-type genes across multiple species (Dendrobium officinale, D. nobile, D. chrysotoxum, P. equestris, V. planifolia, and A. shenzhenica) [17], indicating TIR domain degeneration is common in monocots.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

How can I resolve inconsistent domain annotation in my NBS gene predictions?

Problem: Different bioinformatics tools (Pfam, SMART, CDD) yield conflicting domain annotations for the same NBS gene sequences.

Solution: Implement a consensus approach with multiple verification steps:

- Primary identification: Use HMMER with NB-ARC domain (PF00931) at E-value < 1×10⁻²⁰ [14] [7]

- Domain verification: Cross-validate with Pfam, SMART, and conserved domain database (CDD)

- Coiled-coil prediction: Use Coiledcoil with threshold 0.5 (CC domains often missed by Pfam) [16]

- Manual curation: Verify boundary positions and domain integrity

Preventive measures: Establish consistent parameter settings across all analyses and use curated reference sequences from closely related species for comparison.

Why do my phylogenetic trees show unstable topologies with NBS sequences?

Problem: Inconsistent tree topologies and low bootstrap values when reconstructing NBS gene evolutionary relationships.

Root causes and solutions:

- Rapid evolution: NBS genes, especially LRR domains, evolve rapidly. Use only the conserved NBS domain for phylogenetic analysis [13]

- Recombination hotspots: NBS genes are prone to recombination. Implement recombination detection (e.g., RDP4) and analyze recombinant regions separately

- Incomplete sequences: Use only full-length domains (TIR-NBS-LRR, CC-NBS-LRR, etc.) for reliable phylogeny [7]

- Appropriate models: Use Whelan and Goldman model with frequency correction for NBS domains [14]

How should I handle non-canonical NBS architectures in my annotation pipeline?

Problem: Your pipeline misses or misclassifies genes with unusual domain combinations like TIR-NBS-TIR-Cupin_1 or NLNLN architectures.

Solution: Expand your classification system to accommodate both classical and species-specific patterns:

- Custom HMM profiles: Develop lineage-specific HMMs based on manually curated examples

- Motif-based classification: Use MEME with 6-50 amino acid width to identify conserved motifs beyond core domains [16] [14]

- Structural validation: Correlate gene structures with exon-intron patterns—CNLs typically have fewer exons than TNLs [16]

Experimental Protocols for Comprehensive NBS Gene Analysis

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide Identification and Classification of NBS Genes

Materials and Reagents:

- Genomic sequence and annotation files (GFF3)

- HMMER software (v3.3.2)

- Pfam database (current version)

- MEME Suite (v5.4.1)

- TBtools or custom scripting environment

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Initial identification: Perform HMMsearch against target genome using NB-ARC domain (PF00931) with E-value < 1×10⁻²⁰ [14]

- Domain verification: Submit candidate sequences to Pfam, SMART, and CDD for domain validation

- Classification: Categorize genes based on presence/absence of TIR, CC, RPW8, and LRR domains

- Motif discovery: Identify conserved motifs using MEME with parameters: motif count=10, width=6-50 amino acids [16]

- Gene structure analysis: Extract exon-intron information from GFF3 files and visualize with TBtools

Protocol 2: Evolutionary and Expression Analysis of NBS Genes

Materials and Reagents:

- Multiple genome sequences for comparative analysis

- RNA-seq data under stress conditions

- MEGA software (v7.0+)

- Expression analysis tools (DESeq2, edgeR)

Methodology:

- Phylogenetic reconstruction: Align protein sequences using ClustalW, construct tree with Maximum Likelihood method (Whelan and Goldman model, 1000 bootstrap replicates) [14]

- Selection pressure analysis: Calculate Ka/Ks ratios using codeml in PAML package

- Expression profiling: Analyze RNA-seq data to identify NBS genes responsive to pathogens or hormone treatments

- cis-element analysis: Extract 1.5kb promoter regions and identify regulatory elements using PlantCARE database [14]

Visualization of NBS Gene Classification Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for structural classification of NBS genes, integrating both classical and species-specific architectures:

Research Reagent Solutions for NBS Gene Analysis

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for NBS Gene Studies

| Category | Item/Software | Specific Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Tools | HMMER v3.3 | Hidden Markov Model searches | Core tool for initial NBS gene identification [14] |

| MEME Suite v5.4.1 | Motif discovery and analysis | Identifies conserved motifs beyond core domains [16] | |

| MEGA v7.0+ | Phylogenetic analysis | Maximum Likelihood trees with bootstrap testing [14] | |

| TBtools | Genomic data visualization | Integrates multiple analysis functions [16] | |

| Databases | Pfam Database | Protein domain families | NB-ARC domain (PF00931) as primary reference [14] |

| PlantCARE | cis-element prediction | Identifies regulatory elements in promoter regions [14] | |

| CDD (NCBI) | Conserved domain identification | Validates domain predictions from multiple sources [16] | |

| Experimental Materials | RNA-seq libraries | Expression profiling | Essential for stress-responsive NBS gene identification [17] |

| VIGS vectors | Functional validation | Virus-induced gene silencing for gene function studies [12] |

Advanced Technical Considerations

How does junctional diversity impact functional studies of NBS genes?

Junctional diversity in NBS genes—created by domain shuffling, exon/intron structure variation, and presence-absence polymorphisms—directly affects your functional characterization outcomes. When designing functional studies:

- Consider architectural context: A CNL gene in a cluster may have different functions than a singleton CNL with identical domains [13]

- Account for expression variation: Structural variants (SVs) significantly impact gene expression patterns independent of domain composition [15]

- Validate subcellular localization: Predict localization using CELLO v.2.5 and Plant-mPLoc, as NBS proteins localize to cytoplasm (77.6%), plasma membrane (21.2%), or nucleus (7.7%) [14]

What analytical strategies best handle the "core-adaptive" model of NBS gene evolution?

Recent pan-genomic analyses support a "core-adaptive" model where some NBS subgroups are conserved across accessions while others show extensive presence-absence variation [15]. To address this:

- Implement pan-genome analysis: Analyze multiple genomes/accessions of your target species to distinguish core and adaptive NBS genes

- Correlate duplication mechanisms with selection pressures: Whole-genome duplication derived genes typically show strong purifying selection (low Ka/Ks), while tandem/segmental duplicates often show relaxed or positive selection [15]

- Map gene clusters: 54% of pepper NBS-LRR genes are physically clustered (47 clusters across chromosomes) [13]—these clusters are hotspots for functional innovation

By integrating these specialized approaches with the fundamental protocols above, your research on NBS gene structural classification will effectively address both classical architectures and the dynamic, species-specific variations that define this crucial gene family.

The Functional Spectrum of NBS Domains in Disease Resistance Pathways

NBS-LRR Gene Identification & Classification Troubleshooting

FAQ: What are the common types of NBS-LRR genes I might identify, and how are they classified? NBS-LRR genes are primarily classified based on their variable N-terminal domains. The two major subfamilies are TIR-NBS-LRR (TNL) and CC-NBS-LRR (CNL), defined by the presence of Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) or coiled-coil (CC) motifs, respectively [18]. A third, smaller subclass is the RPW8-NBS-LRR (RNL) [19]. Additionally, "irregular" types exist that lack the LRR domain entirely, such as TN (TIR-NBS), CN (CC-NBS), and N (NBS-only) proteins, which may function as adaptors or regulators for the typical types [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: My HMM search is returning too many false positives. How can I improve accuracy?

- Problem: Initial HMMER search results include non-NBS-LRR proteins.

- Solution: A multi-step validation protocol is required.

- Initial Search: Use HMMER with the NB-ARC domain (PF00931) as a query, setting a strict expectation value (e.g., E-value < 1*10⁻²⁰) [7].

- Remove Redundancy: Manually remove duplicate genes from the candidate list.

- Domain Validation: Submit the remaining candidate sequences to Pfam and the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (CDD) to confirm the presence of both the NBS domain and the N-terminal domain (CC, TIR, or RPW8). Use an E-value cutoff of 10⁻⁴ for confirmation [19].

- Structure Verification: Use tools like SMART to analyze domain architecture and ensure the complete presence of the NBS domain [7].

FAQ: Why does the number of NBS-LRR genes vary so dramatically between species? The NBS-LRR family evolves rapidly through frequent gene duplication and loss events [19]. For example, a study in Rosaceae species revealed distinct evolutionary patterns, such as "continuous expansion" in rose and "expansion followed by contraction" in strawberry, leading to significant differences in gene number even among closely related species [19]. In tung trees, Vernicia montana has 149 NBS-LRR genes, while its susceptible counterpart, Vernicia fordii, has only 90, partly due to the loss of specific LRR domains in V. fordii [5].

Experimental Protocols for Functional Analysis

Protocol 1: Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) for Functional Validation This protocol is used to knock down a candidate NBS-LRR gene to test its role in disease resistance [5].

- Candidate Gene Selection: Identify target NBS-LRR genes through transcriptome data or orthologous analysis. For example, the orthologous pair Vf11G0978/Vm019719 was selected due to its differential expression during Fusarium wilt infection [5].

- Vector Construction: Clone a 200-300 bp specific fragment of the target gene into a VIGS vector (e.g., TRV-based vector).

- Plant Infiltration: Transform the construct into Agrobacterium tumefaciens and infiltrate the bacteria into the leaves of young plants (e.g., 2-week-old seedlings of Nicotiana benthamiana or your species of interest).

- Pathogen Challenge: After granting 2-3 weeks for gene silencing to establish, challenge the plants with the target pathogen.

- Phenotypic Assessment: Monitor and record disease symptoms over time. Compare the disease progression in silenced plants against control plants (e.g., transformed with an empty vector).

- Molecular Verification: Use qRT-PCR to confirm the reduction of target gene expression in silenced plants, linking the observed phenotype to the specific gene knockdown [5].

Protocol 2: Analyzing Intramolecular Interactions in NBS-LRR Proteins This protocol, based on the study of the potato Rx protein, tests functional complementation between separate protein domains [20].

- Construct Design: Create expression clones for separate domains of the NBS-LRR protein (e.g., CC-NBS, LRR, CC, NBS-LRR). Ensure these are epitope-tagged (e.g., HA-tag) for detection.

- Transient Co-expression: Express different combinations of these domain constructs in a model system like Nicotiana benthamiana leaves via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation.

- Elicitor Trigger: Co-express the constructs with the known pathogen elicitor (e.g., Potato Virus X Coat Protein for Rx).

- Hypersensitive Response (HR) Assay: Observe for a rapid, localized cell death response (HR), which indicates successful complementation and functional reconstitution of the resistance protein.

- Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP): Physically validate the interaction between domains. Immunoprecipitate one tagged domain and probe for the presence of the other interacting domain via western blot.

- Key Control: Test the requirement of a functional P-loop motif in the NBS domain, as the interaction between CC and NBS-LRR is P-loop dependent, whereas the interaction between CC-NBS and LRR is not [20].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Summaries

Table 1: NBS-LRR Gene Family Size and Composition Across Plant Species

| Species | Total NBS-LRR Genes | TNL | CNL | RNL | NL | TN | CN | N | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotiana benthamiana (Tobacco) | 156 | 5 | 25 | Not Specified | 23 | 2 | 41 | 60 | [7] |

| Vernicia montana (Tung Tree) | 149 | 3 | 9 | Not Specified | 12 | 7 | 87 | 29 | [5] |

| Vernicia fordii (Tung Tree) | 90 | 0 | 12 | Not Specified | 12 | 0 | 37 | 29 | [5] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | ~150 | ~62 | ~69 | ~7 | - | ~21 | ~5 | - | [18] |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NBS-LRR Studies

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function / Application in NBS-LRR Research |

|---|---|

| HMMER/Pfam (PF00931) | Identifies candidate NBS-LRR homologs in a genome via hidden Markov model searches for the NB-ARC domain [7] [19]. |

| TRV-based VIGS Vector | A virus-induced gene silencing system used to knock down the expression of candidate NBS-LRR genes to test their function in disease resistance [5]. |

| Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) | Validates physical interactions between different domains of an NBS-LRR protein or with downstream signaling partners [20]. |

| MEME Suite | Discovers conserved protein motifs within the NBS and other domains of NBS-LRR proteins, aiding in phylogenetic and functional analysis [7]. |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Strain GV3101) | Used for transient gene expression in plants, essential for protocols like VIGS, HR assays, and subcellular localization [20]. |

Signaling Pathway & Experimental Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: NBS-LRR protein acts as a molecular switch. Effector perturbation of a guarded host protein triggers a conformational change in the NBS domain from ADP-bound (inactive) to ATP-bound (active), initiating immune signaling [20] [18].

Diagram 2: A standard experimental workflow for the genome-wide identification and functional characterization of NBS-LRR genes, from bioinformatics to experimental validation [7] [5].

Addressing Junctional Diversity in Analysis

FAQ: How does "junctional diversity" — the variation in domain composition — impact my functional analysis? Junctional diversity, resulting from the presence or absence of domains like TIR, CC, or LRR, creates functionally distinct NBS-LRR proteins. This diversity is not noise but a functional feature [7] [5].

- Typical NBS-LRRs (TNL, CNL): Usually serve as primary sensors that trigger resistance pathways by recognizing pathogen effectors [7] [19].

- Irregular Types (TN, CN, N): Often lack the LRR domain and may function as adaptors or regulators, working in concert with typical NBS-LRRs to modulate immune signaling [7].

- RNL Proteins: Typically do not function as primary R genes but act downstream to transduce defense signals from TNLs and CNLs [19].

Troubleshooting Guide: My candidate NBS-LRR gene lacks an LRR domain. Is it still a valid R gene candidate?

- Problem: An identified NBS-containing gene is classified as an "N," "CN," or "TN" type, lacking the canonical LRR domain responsible for specific recognition.

- Solution: Yes, it is still a valid candidate, but its hypothesized function shifts. Instead of direct pathogen recognition, it may be a key signaling component.

- Experimental Adjustment: Design interaction studies (e.g., Yeast-Two-Hybrid, Co-IP) to test if your candidate protein physically associates with full-length NBS-LRR proteins.

- Genetic Analysis: Use VIGS to knock down your candidate and test whether it disrupts the function of known R genes in your pathosystem. An irregular-type NBS-LRR may be essential for the resistance mediated by a typical NBS-LRR partner.

For researchers and drug development professionals working in genomics, population-specific genetic databases are indispensable tools. These repositories are crucial for understanding the genetic basis of diseases, developing targeted therapies, and advancing precision medicine. However, significant gaps and limitations in the current landscape of these databases directly impact the reliability and applicability of research findings, particularly in specialized areas like the analysis of junctional diversity in Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) data.

Junctional diversity refers to the DNA sequence variations introduced by the improper joining of gene segments during processes like V(D)J recombination, which is fundamental for generating diversity in the vertebrate immune system [21]. Accurate analysis of this diversity depends on high-quality, population-specific reference data. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guidance to help scientists identify and work around database limitations in their genetic analysis workflows.

Quantitative Analysis of Database Gaps

A systematic evaluation of 42 National and Ethnic Mutation Frequency Databases (NEMDBs) reveals critical shortcomings that researchers must account for in their experimental design. The table below summarizes the core quantitative findings from a 2025 systematic review [22].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Gaps Identified in National and Ethnic Mutation Frequency Databases (NEMDBs)

| Deficiency Category | Percentage of Databases Affected | Raw Number (out of 42) | Primary Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-standardized Data Formats | 70% | 29/42 | Hinders automated data integration, cross-database queries, and comparative analysis. |

| Incomplete or Outdated Data | 50% | 21/42 | Risks basing conclusions on incomplete variant spectra or obsolete information. |

| Gaps in Cross-Ethnic Comparison Data | 60% | 25/42 | Limits understanding of allele frequency differences across populations, reducing translational relevance. |

FAQs: Addressing Common Researcher Challenges

Q1: My analysis of immune receptor junctional diversity shows inconsistent results across different populations. Could underlying database gaps be a factor?

Yes, this is a common issue. Junctional diversity is highly dependent on the genetic background of the population from which the sample is drawn [23]. If the reference database used for annotation or frequency filtering lacks comprehensive data from your population of interest, it can lead to several problems:

- Misclassification of Common Variants: A variant that is common in one population but absent or rare in another may be incorrectly flagged as a novel or significant finding if the database is biased toward the latter population.

- Inaccurate Frequency Filtering: Pipeline filters that remove common polymorphisms rely on accurate population frequency data. Gaps can cause genuine, population-specific signals to be filtered out or, conversely, allow technical artifacts to persist.

Q2: What are the specific implications of these database gaps for researching disorders related to V(D)J recombination?

V(D)J recombination is a primary mechanism for generating antibody and T-cell receptor diversity [21]. Research into its disorders relies on establishing normal baseline junctional diversity, which is population-dependent. Database gaps can directly impact:

- Disease Association Studies: The ability to correlate specific junctional sequences with disease susceptibility or resistance is compromised if the natural variation within the studied cohort is not properly represented in reference data.

- Diagnostic Assay Development: Assays designed to detect aberrant recombination events may have reduced sensitivity or specificity if they are calibrated against a non-representative genetic background [24].

Q3: What practical steps can I take to mitigate the risk of outdated data in my workflow?

Proactive verification is key. Before beginning an analysis, researchers should:

- Check Database Timestamps: Note the last update date for any public database used.

- Consult Multiple Sources: Cross-reference findings against multiple databases (e.g., ClinVar, dbSNP, and population-specific NEMDBs) to triangulate data reliability [22].

- Prioritize Active Databases: Give preference to databases developed on open-source platforms like LOVD, which have been shown to have a 40% increase in usability and are often more regularly maintained [22].

Troubleshooting Guides for Database-Related Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent Variant Calls in Population Cohorts

Potential Cause and Solution:

- Cause: The reference database or allele frequency filter is biased and does not represent the genetic diversity of your cohort.

- Solution: Implement a tiered analysis approach.

- Initial Calling: Perform variant calling using standard public databases.

- Cohort-Specific Filtering: Establish a "internal frequency" within your own cohort dataset. A variant that appears at a high frequency within your cohort but is absent from reference databases may still be a real, population-specific variant.

- Validation: Confirm these population-specific variants using an orthogonal method, such as Sanger sequencing.

Problem: Failed Validation of Apparent Novel Variants from NGS Data

Potential Cause and Solution:

- Cause: The "novel" variant is, in fact, a common polymorphism in a specific population that is missing from the database used for annotation.

- Solution:

- Check Broader Databases: Query the variant in larger, more diverse aggregate databases like gnomAD to see if it has been reported in any population.

- Literature Search: Conduct a thorough search of scientific literature for studies focusing on the gene or region in your population of interest.

- Collaborate: Reach out to research consortia or institutions that specialize in the genetic study of the relevant population.

Experimental Protocol: Validating Population-Specific Junctional Diversity

This protocol outlines a method to confirm and characterize suspected population-specific junctional diversity variants identified through NGS, accounting for potential database gaps.

Method: Sanger Sequencing Validation and Cloning

Background: Junctional diversity in immunoglobin and T-cell receptor genes arises from the imprecise joining of V (variable), D (diversity), and J (joining) gene segments, coupled with the random addition (P and N nucleotides) and subtraction of nucleotides [21] [25]. This process can generate sequences not found in germline databases.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- Primers: Specifically designed to flank the V-D-J region of interest.

- PCR Reagents: High-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., Q5 from NEB #M0491) to minimize PCR-induced errors [26].

- Cloning Vector: T/A-cloning ready vector (e.g., pCR2.1 from Invitrogen).

- Competent E. coli: recA- strain such as NEB 5-alpha (NEB #C2987) to prevent plasmid recombination [27].

- Sanger Sequencing Reagents.

Procedure:

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the target junctional region from genomic or cDNA using high-fidelity polymerase. Optimize conditions to avoid smear patterns or non-specific bands [28].

- Gel Purification: Excise and purify the correct PCR amplicon from an agarose gel.

- Cloning: Ligate the purified PCR product into a T/A-cloning vector and transform into competent E. coli. This step is critical to separate individual molecular sequences for analysis.

- Colony Screening: Pick multiple bacterial colonies (minimum of 20-50) and culture them. Isolate plasmid DNA.

- Sanger Sequencing: Sequence the inserted DNA from multiple clones using the vector-specific primers.

- Data Analysis: Align the sequenced clones to the germline V, D, and J gene sequences. Identify the exact boundaries and any non-templated nucleotide additions (N-nucleotides) or deletions, confirming the unique junctional sequence [25].

Workflow for Validating Junctional Diversity

Proposed Solutions and Future Directions

To address the identified gaps, the research community is moving toward engineering-driven solutions. The following table outlines key proposed strategies based on the latest research [22].

Table 2: Proposed Engineering Solutions for Database Interoperability and Usability

| Solution Framework | Key Features | Potential Benefit for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Cloud-Based Platforms | Centralized data storage, scalable computing, standardized access protocols. | Enables large-scale, cross-database meta-analyses without local download and formatting hurdles. |

| Linked Open Data (LOD) Frameworks | Uses semantic web technologies to create a unified network of connected databases. | Allows for sophisticated queries across multiple databases simultaneously, automatically resolving identifier conflicts. |

| AI-Driven Mutation Prediction Models | Machine learning models trained on existing data to predict pathogenicity and fill data gaps. | Provides preliminary insights for variants of unknown significance (VUS), helping to prioritize targets for functional validation. |

Solution Framework for Database Gaps

Advanced Analytical Frameworks for High-Fidelity NBS Gene Profiling

引言

在基因组学研究中,选择适当的测序平台对研究成功至关重要。特别是在处理具有高度连接多样性(junctional diversity)的基因分析时,如NBS基因研究,研究人员需要在靶向panel、全外显子组测序和全基因组测序之间做出明智选择。本文将深入探讨这三种方法的优劣比较,并提供针对NBS基因分析中连接多样性研究的具体技术指导。

测序方法比较

三种主要测序方法在覆盖范围、成本和应用场景上各有特点。下表详细比较了它们的关键特性:

表1:靶向Panel、全外显子组测序和全基因组测序的比较

| 参数 | 靶向Panel测序 | 全外显子组测序 | 全基因组测序 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 测序区域 | 2-1000+个基因 [29] | 约20,000个基因(占基因组的1-2%) [30] [29] | 几乎整个基因组:所有编码和非编码区域 [29] |

| 区域大小 | 取决于panel设计 | > 30 Mb [30] | 3 Gb [30] |

| 测序深度 | > 500X [30] | 50-150X [30] | > 30X [30] |

| 数据量 | 因panel而异 | 5-10 Gb [30] | > 90 Gb [30] |

| 成本 | £200-£700 [29] | £750 [29] | £1,000 [29] |

| 可检测变异类型 | SNPs、InDels、CNV、Fusion [30] | SNPs、InDels、CNV、Fusion [30] | SNPs、InDels、CNV、Fusion、SV [30] |

| 优势 | 可定制、成本最低、覆盖深度高(可检测嵌合体) [29] | 可识别疾病的新的遗传原因、无需随着新基因发现而更新(与靶向panel相比)、相比WGS分析的意义未明变异较少 [29] | 可识别调控内含子/增强子区域的致病变异、由于覆盖均匀,检测拷贝数变异和结构重排最佳 [29] |

| 劣势 | 无法识别尚未已知导致特定疾病或表型的基因变异、难以随新基因发现而更新、无法检测CNV/结构重排 [29] | 鉴定出的意义未明变异更多(与靶向panel相比)、测序深度不足,可能无法检测嵌合体(与靶向panel相比)、可能遗漏内含子和调控/增强子突变、检测CNV/结构重排能力有限 [29] | 成本最高、数据量大需要安全存储、鉴定意义未明变异的几率最高、临床解读变异的工作量显著、 incidental findings风险增加 [29] |

实验方案

全外显子组测序工作流程

全外显子组测序工作流程可分为三个主要阶段 [30]:

1. 文库制备

- 样本处理:初步处理样本以提取DNA

- DNA提取:从处理的样本中分离DNA

- 定量:测量DNA浓度以确保足够的起始量

- 文库构建:制备用于测序的DNA文库

- 杂交捕获:通过杂交富集目标外显子区域

- 扩增:复制DNA片段以提高测序灵敏度

- 质量控制:评估文库质量以确保最佳测序条件

2. 测序 利用测序平台,包括进口平台如Illumina和国产平台。

3. 生物信息学分析

- 质量控制:评估测序数据的可靠性

- 拼接和匹配:将读段与参考基因组比对

- 去重复和重排:去除重复读段和数据重排

- 突变检测:识别遗传变异和突变

- 噪声减少和过滤:应用过滤器以最小化背景噪声

- 注释:为识别的变异添加功能信息

- 常用软件:FastQC、BWA、GATK、ANNOVAR等 [30]

连接多样性分析实验方案

在NBS基因研究中,分析连接多样性需要特定的实验方法。以下是一个针对性的实验方案:

样本准备

- 从健康供者和患者收集外周血样本

- 通过EB病毒转化建立淋巴母细胞样细胞系

- 使用标准方案培养细胞系

V(D)J重组分析

- 设计包含连接多样性区域的特异性引物

- 进行PCR扩增目标区域

- 纯化PCR产物并准备用于测序

- 使用Sanger测序或高通量测序验证连接序列

连接位点测序

- 使用高深度测序(>500X)以检测稀有连接变体

- 设计覆盖所有可能连接变体的探针

- 进行多重PCR扩增以提高检测效率

- 使用生物信息学工具分析连接多样性

数据分析与解释

- 比对测序读段到参考基因组

- 识别连接位点和序列变异

- 量化不同连接变体的频率

- 评估连接多样性与NBS表型的相关性

NBS基因连接多样性分析工作流程

连接多样性分析指南

连接多样性在NBS研究中的重要性

连接多样性是指在V(D)J重组过程中,通过编码末端的处理产生的序列变异。这一过程包括 [1]:

- N核苷酸添加:通过末端脱氧核苷酸转移酶添加

- P核苷酸形成:发夹状编码末端中间体的偏中心切割结果

- 编码末端序列的外切核酸酶"咀嚼"

在NBS基因研究中,正常的V(D)J重组过程对免疫多样性至关重要。研究表明,NBS1基因突变不会显著影响信号连接或编码连接的形成 [31],这意味着在NBS患者中,连接多样性可能通过其他机制受到影响。

连接位点测序的最佳实践

测序平台选择

- 对于靶向连接分析,使用高深度的靶向panel测序(>500X)

- 对于全外显子组分析,确保覆盖关键的连接区域

- 考虑使用长读长测序技术解决高度可变的区域

探针设计考量

生物信息学分析

- 实施专门为连接多样性分析设计的定制流程

- 使用敏感算法检测N和P核苷酸添加 [1]

- 量化不同连接变体的频率

- 将连接序列与临床表型关联

常见问题解答

问:在NBS基因研究中,何时应选择靶向panel测序而非全外显子组或全基因组测序?

答:当研究目标明确且仅限于已知与NBS相关的基因时,靶向panel测序是最佳选择。它提供更高的覆盖深度(>500X),能检测嵌合现象,且成本较低 [29]。然而,如果目标是发现新的疾病相关基因或分析非编码区域,则全外显子组或全基因组测序更合适。

问:如何处理连接多样性分析中遇到的高错误率?

答:连接多样性分析中的错误率可以通过以下方式降低:

- 增加测序深度(>500X)以提高检测准确性

- 使用重复读段去除技术减少PCR错误

- 实施多重重叠验证关键变异

- 使用专门为连接区域设计的生物信息学工具

问:在NBS研究中,全外显子组测序能否充分捕获连接多样性区域?

答:全外显子组测序可以捕获编码区的连接多样性,但可能错过调控元件和内含子区域的重要信号。对于全面的连接多样性分析,建议使用包含相关非编码区域定制设计的靶向panel,或使用全基因组测序 [29]。

问:如何评估杂交捕获探针在连接多样性研究中的性能?

答:评估杂交捕获探针时考虑以下指标 [30]:

- 靶标率:越高越好,减少脱靶浪费

- 覆盖度:确保目标区域有足够深度覆盖

- 均一性:覆盖在不同位点的均匀程度

- 重复率:越低越好,减少数据浪费

问:在资源有限的情况下,如何进行有效的连接多样性研究?

答:在资源有限的情况下:

- 从靶向panel测序开始,专注于关键连接区域

- 使用多重PCR方法提高效率

- 优先分析已知与表型相关的高影响区域

- 考虑使用成本较低的Sanger测序验证关键发现

研究试剂解决方案

表2:连接多样性分析关键研究试剂

| 试剂/工具 | 功能 | 应用示例 |

|---|---|---|

| RAG-1/RAG-2蛋白 | 识别RSS并在信号和编码区域边界切割DNA [31] | V(D)J重组机制研究 |

| DNA连接酶IV/XRCC4复合物 | 形成编码和信号连接 [31] | 连接形成分析 |

| 末端脱氧核苷酸转移酶 | 通过添加N核苷酸增加连接多样性 [1] | N区域多样性分析 |

| Nbs1/Mre11/Rad50复合物 | DNA双链断裂修复 [31] | NBS基因功能研究 |

| 杂交捕获探针 | 目标区域富集 [30] | 靶向连接区域测序 |

| 特异引物 | 扩增特定连接区域 | PCR-based连接分析 |

技术故障排除

问题:靶向测序中覆盖度不均

解决方案:

- 优化探针设计以提高均一性

- 调整杂交条件减少GC偏差

- 使用多次捕获提高低覆盖区域的表现

- 添加额外探针针对覆盖不足的区域

问题:连接位点扩增效率低

解决方案:

- 重新设计引物以避免二级结构

- 优化退火温度提高特异性

- 使用 touchdown PCR 提高特异性

- 添加DMSO或甜菜碱改善高GC区域的扩增

问题:测序数据中高重复率

解决方案:

- 优化文库制备减少PCR重复

- 增加起始DNA量减少扩增偏倚

- 使用唯一分子标识符区分真实变异与PCR错误

- 调整聚类条件减少过度扩增

连接多样性测序常见问题解决方案

结论

在NBS基因分析研究中,选择合适的测序平台对成功解析连接多样性至关重要。靶向panel测序为已知基因区域提供深度覆盖,全外显子组测序平衡覆盖范围与成本,而全基因组测序提供最全面的基因组视图。研究人员应根据具体研究目标、预算限制和分析需求选择最合适的方法。随着测序技术的不断发展,这些平台的能力将继续提升,为NBS和其他遗传疾病的连接多样性研究开辟新的可能性。

Bioinformatic Pipelines for NBS Gene Identification and Orthogroup Analysis

The integration of genomic technologies into newborn screening (NBS) represents a significant advancement in identifying treatable genetic disorders before symptom onset. The process begins with sample collection and progresses through a structured bioinformatic pipeline to deliver actionable clinical insights.

Workflow Description: The bioinformatic pipeline for genomic newborn screening initiates with DNA extraction from dried blood spots (DBS), followed by library preparation and next-generation sequencing (NGS) [32]. Raw sequencing data undergoes quality control, alignment to a reference genome, and variant calling to identify single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions (indels) [32] [33]. Detected variants are filtered against population databases and classified according to American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines before clinical reporting [34].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of NBS gene identification requires specific laboratory reagents and bioinformatic tools validated for clinical-grade performance.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Genomic NBS Workflows

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | LaCAR MDx filter paper cards [32] | Standardized dried blood spot collection for DNA stability |

| DNA Extraction | QIAamp DNA Investigator Kit (manual) [32]QIAsymphony DNA Investigator Kit (automated) [32] | High-quality DNA extraction from DBS with scalability options |

| Library Preparation | Twist Bioscience target enrichment [32] | Capture of genomic regions of interest (e.g., 405 genes for 165 diseases) |

| Sequencing | Illumina NovaSeq 6000, NextSeq 500/550 [32] | High-throughput sequencing with 2×75 bp to 2×150 bp read lengths |

| Reference Materials | HG002/NA24385 (GIAB reference DNA) [32] | Analytical validation and pipeline performance benchmarking |

Table 2: Bioinformatics Tools for NBS Gene Identification

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Application in NBS Context |

|---|---|---|

| Read Alignment | BWA-MEM [32] | Mapping sequencing reads to reference genome (GRCh37/hg19) |

| Variant Calling | GATK HaplotypeCaller [32] [35] | Identification of SNVs and small indels |

| Variant Annotation | ANNOVAR [35], Ensembl VEP [35] | Functional consequence prediction of genetic variants |

| Variant Interpretation | Franklin [34], VarSome [34] | ACMG-based classification of pathogenicity |

| Quality Control | Custom QC thresholds [32] | Monitoring coverage, contamination, and performance metrics |

Orthogroup Analysis for Evolutionary Insights

Orthogroup analysis enables researchers to identify groups of genes descended from a single ancestral gene in a common ancestor, providing evolutionary context for NBS gene candidates.

Analysis Pipeline: Orthogroup analysis begins with properly formatted input files, typically protein or transcript sequences in FASTA format [36]. The OrthoFinder algorithm performs all-versus-all sequence comparisons to infer orthologous relationships [36]. Successful execution produces orthogroups (groups of orthologous genes) and gene trees depicting evolutionary relationships [36].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Genomic NBS Pipeline Challenges

Issue: High False-Positive Rates in Variant Calling

- Root Cause: Inadequate filtering of population-specific polymorphisms or technical artifacts [35].

- Solution: Implement strict quality control thresholds for sequencing metrics, including coverage depth and mapping quality [32]. Use multiple annotation databases (ClinVar, Franklin, VarSome) for variant classification [34]. Establish allele frequency thresholds based on relevant population databases [35].

- Validation Protocol: Supplement standard truth sets (Genome in a Bottle) with recall testing of previous real human clinical cases validated by orthogonal methods [33].

Issue: Incomplete Target Region Coverage

- Root Cause: Poor probe design or capture efficiency in targeted sequencing panels [32].

- Solution: Redesign panels to focus on coding regions and intron-exon boundaries, excluding problematic regions like homopolymeric stretches and deep intronic areas [32]. Implement automated extraction methods (QIAsymphony) to improve DNA quality and coverage consistency [32].

- Quality Metrics: Require >95% of target bases to achieve minimum 20x coverage, with strict monitoring of batch-to-batch performance [32].

Issue: Variants of Uncertain Significance (VUS)

- Root Cause: Limited population frequency data or conflicting functional evidence [35].

- Solution: Implement a structured classification tree using platforms like Alissa Interpret to systematically triage variants [34]. Discard VUS and focus reporting on pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants with established disease associations [34]. Conduct extended literature reviews and correlation with biochemical results when available [34].

Orthogroup Analysis Technical Problems

Issue: OrthoFinder Fails with "Zero Datasets" Error

- Root Cause: Incorrect file formats or improper file organization [36].

- Solution: Ensure all input files are in proper FASTA format with simplified headers (use NormalizeFasta tool if needed). Verify that GFF3 annotation files contain the mandatory header

##gff-version 3at the very top [36]. For multi-species analyses, organize files into collection folders with consistent ordering across fasta and annotation collections [36].

Issue: Missing Gene Trees in OrthoFinder Output

- Root Cause: Identifier mismatches between FASTA and GFF3 files, or incomplete annotations [36].

- Solution: Validate that all identifiers in the FASTA files exactly match those in the GFF3 annotation files. Check that GFF3 files contain proper feature annotations (genes, transcripts, exons) for all sequences in the FASTA files [36]. Consider running OrthoFinder without annotation files as a diagnostic step to isolate the issue [36].

Issue: Proteinortho Produces No Output

- Root Cause: Typically related to file format incompatibilities or insufficient computational resources [36].

- Solution: Verify all input files are properly formatted protein FASTA files with consistent sequencing naming. Check system resources and ensure adequate memory allocation for larger datasets. Test with smaller subsets of data to validate the workflow before scaling to full analyses [36].

Advanced Integration: Multi-Omics Approaches in NBS

Emerging research demonstrates that combining genomic data with other molecular profiling technologies significantly enhances NBS accuracy and clinical utility.

Genomic-Metabolomic Integration: Research shows that integrating genome sequencing with targeted metabolomics and artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML) classifiers can improve NBS accuracy [35]. In one study, metabolomics with AI/ML detected all true positives (100% sensitivity), while genome sequencing reduced false positives by 98.8% [35]. This approach is particularly valuable for conditions like VLCADD, where heterozygote carriers frequently trigger false-positive results in conventional MS/MS screening [35].

Structural Variant Detection: Current targeted NGS panels primarily focus on SNVs and small indels, with structural variant (SV) analysis remaining challenging due to insufficient positive controls for validation [32]. Advanced approaches now leverage long-read sequencing technologies (Oxford Nanopore) and graph-based reference genomes (HPRC) to comprehensively characterize SVs, including deletions, duplications, insertions, and inversions [37]. The SAGA (SV Analysis by Graph Augmentation) framework enables non-redundant SV callset integration across multiple callers, enhancing SV discovery in diverse populations [37].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is RaMeDiES and what specific problem does it solve in rare disease research? RaMeDiES (Rare Mendelian Disease Enrichment Statistics) is a specialized software suite designed for the joint genomic analysis of rare disease cohorts. It addresses the critical challenge of identifying diagnostic variants in patients with ultra-rare, genetically elusive presentations. Traditional case-by-case analysis often fails for these patients. RaMeDiES employs well-calibrated statistical methods to prioritize candidate genes by detecting patterns, such as de novo recurrence and compound heterozygosity, across an entire cohort of sequenced individuals, significantly improving diagnostic yield [38].

Q2: How does RaMeDiES differ from single-case prioritization tools like Exomiser? While tools like Exomiser are essential for analyzing individual patients by integrating genotype and phenotype (HPO terms), RaMeDiES adopts a complementary, "genotype-first" approach. It performs a joint analysis across a large cohort without initial phenotypic input to find genes enriched with deleterious variants. This method is particularly powerful for discovering novel disease genes and diagnosing patients with atypical presentations that might be missed by single-case analysis. It is recommended to use both approaches in tandem for comprehensive analysis [39] [38].

Q3: Our research involves NBS for SCID, which analyzes junctional diversity through TREC/KREC quantification. Can RaMeDiES aid in discovering novel genetic causes of low TREC/KREC? Yes. While the initial NBS for Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) relies on quantifying T cell and B cell excision circles (TRECs/KRECs), identifying the specific genetic etiology in non-SCID T cell lymphopenia cases remains a challenge [40]. RaMeDiES is ideally suited for this. You can apply it to perform a cohort-wide analysis of whole genome sequencing data from individuals with low TREC/KREC levels. Its ability to detect genes enriched with deleterious variants can help pinpoint novel genetic causes of primary immunodeficiencies that disrupt lymphocyte development, thereby expanding the diagnostic potential of genetic NBS [38] [40].

Q4: What are the key inheritance models RaMeDiES investigates? RaMeDiES is specifically calibrated to prioritize candidates under two primary monogenic inheritance models [38]:

- De novo mutations: Identifies genes with a significant burden of new, non-inherited deleterious mutations in affected individuals.

- Compound heterozygosity: Detects genes where individuals have two different deleterious variants in trans (on opposite chromosomal alleles).

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Issues and Solutions in Variant Prioritization and NBS Gene Analysis

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Problems in Statistical Genetics Analysis

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Quality & Input | RaMeDiES analysis yields no significant gene findings. | ➤ Cohort size is too small for statistical power.➤ Poor quality of variant calling (e.g., high false positive rate).➤ Inaccurate or incomplete pedigree information. | Ensure a sufficiently large cohort of sequenced trios or families. For de novo analysis, complete trios (proband + both parents) are essential [38]. Re-process sequencing data through a harmonized pipeline for joint variant calling to minimize artifacts [39] [38]. Verify and validate familial relationships and variant segregation. |

| Junctional Diversity Analysis (NBS) | Inconsistent or failed amplification of TREC/KREC targets in qPCR. | ➤ Degraded DNA template from Dried Blood Spots (DBS).➤ PCR inhibition from sample impurities.➤ Suboptimal primer/probe design for the multicopy target. | Use standardized protocols for DNA extraction from DBS to ensure integrity [40]. Include pre-amplification cleanup steps and use of PCR inhibitors in the reaction mix. Validate primer/probe sets against the latest reference genomes and use multiplex qPCR protocols established for this purpose [40]. |

| Variant Prioritization | Known diagnostic variant is not prioritized in the top ranks by tools like Exomiser. | ➤ Suboptimal tool parameters (e.g., default phenotype similarity algorithm).➤ Incomplete or low-quality HPO term list for the proband.➤ The variant is in a non-coding region, which is not the primary focus of Exomiser. | Optimize parameters; for example, adjusting the gene-phenotype association algorithm can increase top-10 ranking of diagnostic variants from ~50% to over 85% [39]. Manually curate a comprehensive and specific list of HPO terms. Avoid over-reliance on automated term extraction, which can introduce bias [39]. For non-coding or regulatory variants, use a complementary tool like Genomiser, which is designed for this purpose [39]. |

| Functional Validation | A candidate gene from RaMeDiES has no known disease association. | ➤ This is a potential novel disease gene discovery. | Perform a systematic clinical review for phenotypic similarity across patients with variants in the same candidate gene [38]. Utilize matchmaking services like MatchMaker Exchange to find other patients with similar genotypes and phenotypes [38]. Partner with functional genomics cores (e.g., the UDN Model Organisms Screening Core) for in vivo validation [38]. |

Experimental Protocol: Joint Cohort Analysis with RaMeDiES

This protocol outlines the steps for performing a cross-cohort analysis to identify novel disease genes using RaMeDiES, as described in the UDN study [38].

1. Sample and Data Preparation: * Cohort Selection: Assemble a cohort of unrelated probands with whole genome sequencing (WGS) data. The inclusion of complete parent-proband trios is mandatory for de novo mutation analysis. * Data Harmonization: Re-process all WGS data through a unified bioinformatic pipeline (e.g., a pipeline based on Sentieon) aligned to GRCh38. Jointly call single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels across all samples to ensure consistency and reduce batch effects [38]. * De Novo Calling: Perform high-quality de novo mutation calling from the aligned reads of complete trios using a specialized tool. The average expected yield is ~78 de novo SNVs and ~10 de novo indels per proband, which serves as a quality check [38].

2. Running RaMeDiES Analysis: * Inputs: The main input for RaMeDiES is the harmonized, jointly-called VCF file for the entire cohort. * Statistical Framework: RaMeDiES uses an analytical goodness-of-fit test to identify genes enriched for deleterious de novo mutations. It incorporates: * Variant Deleteriousness Scores: Leverages state-of-the-art deep learning models (e.g., PrimateAI-3D, AlphaMissense) to assign pathogenicity probabilities [38]. * Mutation Rate Models: Utilizes basepair-resolution de novo mutation rate models to calculate a "mutational target" for each gene. * Execution: Run RaMeDiES for different variant classes (e.g., missense-only, or all exonic variants). The tool combines evidence from SNVs and indels and can apply a weighted False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction using GeneBayes scores to prioritize genes under strong evolutionary constraint [38].

3. Clinical Evaluation and Validation: * Genotype-First Triage: The output is a list of candidate gene-patient matches, prioritized by statistical significance, without prior phenotypic filtering. * Phenotypic Assessment: For each candidate, a clinical team evaluates the match between the patient's detailed phenotype (using HPO terms) and the gene's known or putative function. * Standardized Protocol: Use a semi-quantitative, hierarchical decision model (e.g., based on the ClinGen framework) to consistently score the gene-patient diagnostic fit across different evaluators. This protocol should be blind-validated against non-causative control genes [38].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the RaMeDiES-based diagnostic discovery process.

Joint Genomic Analysis Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for Statistical Genetics and NBS Research

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| GRCh38 Reference Genome | The current standard reference for human genome alignment and variant calling, essential for data harmonization [39] [38]. |

| Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) | A standardized vocabulary of clinical phenotypes used to describe patient symptoms computationally, crucial for phenotypic matching after a genotype-first discovery [39] [38]. |

| Dried Blood Spots (DBS) | The standard sample source for Newborn Screening (NBS) programs, used for assays like TREC/KREC qPCR and genetic screening for SMA [40]. |

| Multiplex Real-Time PCR | A modular and high-throughput technology used in genetic NBS to simultaneously screen for multiple conditions (e.g., SCID, SMA, Sickle Cell Disease) by quantifying targets like TRECs, KRECs, and SMN1 [40]. |

| Exomiser/Genomiser | Open-source software for phenotype-based prioritization of coding and non-coding variants in single cases. Used as a complementary tool to cohort-based methods like RaMeDiES [39]. |

| RaMeDiES Software | The core tool for performing well-calibrated statistical tests for de novo recurrence and compound heterozygosity across a sequenced cohort [38]. |

| MatchMaker Exchange | A federated platform for matching cases with similar genotypic and phenotypic profiles globally, used to validate novel candidate genes [38]. |

Performance Data

Table 3: Impact of Optimized Variant Prioritization on Diagnostic Yield

| Tool / Method | Key Performance Metric | Improvement / Outcome | Key Enabler |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exomiser (Optimized) | Top-10 ranking of coding diagnostic variants in GS data | Increased from 49.7% (default) to 85.5% (optimized) [39] | Parameter tuning (gene-phenotype algorithm, pathogenicity predictors) [39] |

| Genomiser (Optimized) | Top-10 ranking of non-coding diagnostic variants | Improved from 15.0% to 40.0% [39] | Use of regulatory annotation scores (e.g., ReMM) [39] |

| RaMeDiES (De Novo) | Gene discovery and diagnosis in a complex UDN cohort | Identification of KIF21A, BAP1, RHOA, and LRRC7 as significant hits, leading to new diagnoses and inclusion in a clinical case series [38] | Cohort-wide analysis integrating per-variant deleteriousness scores and mutation rates [38] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is there often a poor correlation between my transcriptomics and proteomics data? The assumption of a direct, proportional relationship between mRNA and protein expression is often incorrect. The correlation can be low due to several biological and technical factors [41]:

- Biological Factors: Key biological processes create a disconnect, including:

- Different Half-Lives: Proteins and mRNAs have distinct turnover rates.

- Post-Transcriptional Regulation: Processes like microRNA activity and mRNA stability control translation.

- Translational Efficiency: This is influenced by factors like codon bias, ribosome density, and the physical structure of the mRNA itself [41].

- Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs): Proteins are extensively modified after synthesis, affecting their function and stability without changing mRNA levels [42].

- Technical Factors: Limitations in measurement technologies contribute, such as: