Navigating Data Ownership and Sharing in AI-Driven Drug Development: Challenges and Strategic Solutions

This article addresses the critical challenges of data sharing and ownership that researchers and drug development professionals face when integrating artificial intelligence into pharmaceutical R&D.

Navigating Data Ownership and Sharing in AI-Driven Drug Development: Challenges and Strategic Solutions

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenges of data sharing and ownership that researchers and drug development professionals face when integrating artificial intelligence into pharmaceutical R&D. It explores the foundational need for high-quality, diverse datasets to train robust AI models, examines methodologies for secure data application, provides strategies for troubleshooting legal and infrastructural barriers, and outlines frameworks for validating AI tools within the current regulatory landscape. Aimed at fostering innovation, the content synthesizes evolving regulatory guidance, practical compliance strategies, and collaborative models to advance AI-driven drug discovery while safeguarding data rights.

The Indispensable Role of Data in AI-Driven Drug Discovery

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Common Data Quality Issues in Agricultural AI Models

Problem: Model predictions are inaccurate or unreliable.

- Step 1: Check data completeness using the Ag Image Repository's cut-out analysis for missing plant growth stages [1].

- Step 2: Verify data consistency by ensuring all images follow standardized formats and annotations from the FAIR/CARE standards required by USDA DSFAS grants [2].

- Step 3: Validate data accuracy against ground-truth field measurements for at least 5% of your dataset.

- Step 4: Implement continuous monitoring using data quality metrics from established frameworks [3].

Problem: AI model performs well in testing but fails in real-field conditions.

- Step 1: Test model against the PSA's Benchbot validation protocol using semi-field environment images [1].

- Step 2: Verify temporal relevance - ensure training data includes seasonal variations from multiple growing cycles.

- Step 3: Check for synthetic data feedback loops by balancing AI-generated data with real-world field samples [3].

Guide 2: Addressing Data Access and Sharing Challenges

Problem: Cannot access sufficient agricultural data for model training.

- Step 1: Access the public Ag Image Repository containing 1.5 million plant images via USDA SCINet [1].

- Step 2: Form Coordinated Innovation Networks (CIN) as outlined in DSFAS guidelines to pool resources with other institutions [2].

- Step 3: Implement synthetic data generation following Sony AI's FHIBE responsible augmentation protocols [4].

Problem: Data sharing conflicts due to ownership concerns.

- Step 1: Develop data governance policies using frameworks that address intellectual property rights [5].

- Step 2: Implement consent mechanisms similar to FHIBE's approach where subjects retain control and can withdraw consent [4].

- Step 3: Establish clear data usage agreements using NIFA's Data Management Plan templates [2].

Frequently Asked Questions

Data Quality FAQs

Q: What are the minimum data quality standards for agricultural AI research? A: Your data must meet these quantitative standards, derived from established AI data quality frameworks and agricultural research requirements [3] [2]:

Table: Minimum Data Quality Standards for Agricultural AI

| Component | Minimum Standard | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | >95% label correctness | Cross-verification by domain experts |

| Completeness | <5% missing growth stages | Gap analysis across temporal sequences |

| Consistency | 100% standardized annotations | Adherence to AgIR metadata protocols [1] |

| Timeliness | <2 years since collection | Date stamps and seasonal relevance checks |

| Relevance | Direct alignment with research objectives | Logic model alignment as per DSFAS requirements [2] |

Q: How can we quickly identify biased data in agricultural datasets? A: Follow this experimental protocol adapted from bias detection methodologies [6]:

- Segment your data by key variables: plant species, growth environment, geographic location

- Benchmark against FHIBE's fairness evaluation framework for demographic attributes [4]

- Test model performance across all segments using consistent metrics

- Analyze performance disparities greater than 10% as potential bias indicators

Data Access FAQs

Q: What are the approved methods for collaborative data sharing in agricultural research? A: Utilize these NIFA-supported approaches [2]:

- Coordinated Innovation Networks (CIN): Multi-institution networks with demonstrable synergy and continuity plans

- FASE Grants: Enhanced funding opportunities for partnerships with minority-serving institutions

- AgIR Public Repository: Open-source access with proper attribution to original collectors [1]

Q: How can we ensure ethical data collection while maintaining research utility? A: Implement this workflow based on successful ethical AI implementations [4]:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for Agricultural AI

Table: Essential Tools for Agricultural AI Research

| Tool/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ag Image Repository (AgIR) | Provides 1.5M high-quality plant images with standardized annotations [1] | Computer vision model training for species identification |

| PSA Benchbots | Automated imaging robots for consistent plant data collection [1] | High-throughput phenotyping and growth monitoring |

| FHIBE Fairness Benchmark | Consent-based, globally diverse dataset for bias evaluation [4] | Testing agricultural AI models for equitable performance |

| USDA SCINet | High-performance computing cluster for agricultural data analysis [2] | Large-scale model training and simulation |

| FAIR/CARE Data Standards | Framework for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable data management [2] | Data governance and sharing protocol implementation |

Experimental Protocol: Data Quality Validation for Plant Phenotyping

Objective: Ensure training data quality for AI-driven plant health assessment.

Materials:

- AgIR-standardized image sets [1]

- PSA Benchbot calibration tools [1]

- Data quality metrics from established AI frameworks [3]

Methodology:

- Image Acquisition: Collect images using calibrated Benchbots across multiple growth stages

- Annotation Quality Control: Implement triple-blind verification for all data labels

- Temporal Consistency Check: Verify complete growth sequences without temporal gaps

- Environmental Variable Documentation: Record all relevant growing conditions

- Bias Assessment: Apply FHIBE fairness evaluation to demographic attributes [4]

Validation Criteria:

- ≥98% annotation accuracy from expert verification

- <2% missing data across all growth stages

- Consistent performance across all plant varieties and conditions

Data Governance Framework Implementation

Q: What essential components must our data governance framework include? A: Your framework must address these critical elements derived from successful implementations [3] [5]:

Implementation Steps:

- Establish Data Governance Team with cross-functional expertise [3]

- Develop Quality Metrics aligned with DSFAS sustainability requirements [2]

- Implement Regular Audits following agricultural research best practices

- Create Incident Response Protocols for data quality issues or bias detection

- Document All Processes using NIFA's Data Management Plan guidelines [2]

Frequently Asked Questions

What is data scarcity in AI research? Data scarcity refers to the growing shortage of high-quality, diverse data needed to train sophisticated AI models. As models become larger and more powerful, the limitations of current data sources create a significant bottleneck. This is especially acute for large language models that require vast amounts of text data, and in fields like agriculture and healthcare where obtaining specialized, labeled data is particularly challenging [7] [8].

Why is data ownership ambiguous in agricultural AI? Data ownership becomes ambiguous because agricultural data often involves multiple stakeholders—farmers, researchers, technology providers, and AI developers—each with potential claims. The legal landscape is complex, with variations in intellectual property laws, trade secret statutes, and jurisdictional differences in data protection regulations. This creates uncertainty about who owns data, especially when it undergoes AI processing to create new "derived data" [9] [10].

How does biased data affect agricultural AI models? Biased data leads to AI models that perform poorly when faced with real-world agricultural variability. For example, a model trained only on images of plants from one region may not recognize the same species grown under different conditions. This lack of generalizability can result in inaccurate recommendations for pest control, yield prediction, or resource allocation, ultimately reducing farmer trust and adoption [7] [1].

What are the main data types in agricultural AI research?

| Data Type | Description | Examples | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field Imagery | High-quality photographs of plants at different growth stages | Ag Image Repository's 1.5M plant photos [1] | Annotation labor, background removal, variable conditions |

| Environmental Data | Satellite and sensor data on growing conditions | NASA GLAM soil moisture, precipitation data [11] | Integration across sources, temporal alignment |

| Derived Data | New data created through AI processing | Augmented data, inferred data, modeled data [9] | Ownership ambiguity, value attribution |

| Operational Data | Farming practice and input records | Treatment details, application rates, yield results [10] | Privacy concerns, commercial sensitivity |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Insufficient Training Data for Crop Disease Detection

Problem: Your AI model for identifying northern corn leaf blight performs poorly on field data despite good validation scores, likely due to insufficient and non-diverse training examples.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Assess Data Diversity: Check if your training set includes images of the disease across different corn varieties, growth stages, weather conditions, and geographical regions [1].

- Evaluate Data Quantity: Determine if you have at least 1,000+ annotated examples per significant disease severity level [7].

- Check Data Balance: Verify that positive and negative examples are balanced across all conditions.

Resolution Methods:

- Leverage Public Repositories: Access the Ag Image Repository (AgIR) which contains 1.5 million high-quality plant images through USDA SCINet [1].

- Implement Data Augmentation: Use synthetic data generation techniques to create variations of existing images by modifying lighting, orientation, and background conditions [7].

- Apply Transfer Learning: Start with models pre-trained on general image datasets like ImageNet, then fine-tune on your specific agricultural task [8].

Prevention Tips:

- Establish continuous data collection partnerships with multiple farms across different regions [11].

- Implement automated data annotation pipelines to reduce labeling bottlenecks [1].

- Develop a data diversity checklist for all new training datasets.

Issue: Data Sharing Resistance from Farming Partners

Problem: Farmers are hesitant to share operational data needed to improve your AI models due to ownership concerns and unclear benefits.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Identify Specific Concerns: Determine whether resistance stems from privacy fears, commercial sensitivity, or lack of perceived value [11].

- Review Data Governance: Assess if your current data use agreements clearly address ownership, control, and benefit-sharing [10].

- Evaluate Transparency: Check how clearly you communicate data usage, retention policies, and potential risks [12].

Resolution Methods:

- Implement the CHDO Framework: Adopt the Collaborative Healthcare Data Ownership framework principles, emphasizing shared ownership, defined access controls, and transparent governance [10].

- Develop Clear Benefit Sharing: Create concrete value propositions showing how data sharing directly benefits farmers through improved recommendations [11].

- Establish Data Trusts: Consider data trust models where neutral third parties manage data access and usage rights [10].

Prevention Tips:

- Co-design data sharing agreements with farmer representatives [11].

- Provide multiple participation tiers with varying levels of data contribution and access.

- Implement federated learning approaches that analyze data locally without centralizing sensitive information [8].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Robust Plant Image Dataset for AI Training

Purpose: Create a diverse, well-annotated image dataset capable of training generalizable computer vision models for agricultural applications.

Materials:

- Benchbot Imaging System: Robotic hardware for standardized plant image capture [1]

- High-Resolution Camera: Capable of capturing detailed images suitable for scientific research [1]

- Annotation Software: Tools for labeling images with plant species, growth stage, and health status [1]

- Data Repository Platform: Secure storage with version control and access management

Methodology:

- Site Selection: Establish imaging locations across multiple geographical regions to capture environmental variability [1].

- Temporal Sampling: Conduct weekly imaging passes throughout the complete plant growth cycle [1].

- Condition Variation: Ensure representation across different soil types, weather conditions, and management practices.

- Quality Control: Implement automated checks for image focus, lighting consistency, and proper labeling.

- Background Removal: Use developed software tools to create "cut-outs" - plants separated from their background [1].

Validation:

- Cross-verify annotations with multiple domain experts

- Test model performance on held-out data from completely new locations

- Measure accuracy degradation across different growing conditions

Protocol 2: Establishing Data Ownership and Sharing Frameworks

Purpose: Develop legally sound and ethically defensible data sharing agreements that respect stakeholder rights while enabling AI research.

Materials:

- Stakeholder Identification Matrix: Template for mapping all parties with data interests

- Data Classification Schema: System for categorizing data by sensitivity and value

- Legal Framework Analysis: Review of relevant GDPR, CCPA, and intellectual property regulations [9]

- Blockchain Technology: For implementing transparent data access logging (optional) [10]

Methodology:

- Stakeholder Analysis: Identify all entities with claims to data ownership (farmers, researchers, technology providers) [10].

- Rights Mapping: Document the specific rights each stakeholder has regarding data access, control, and commercialization [9].

- Framework Selection: Choose appropriate governance model (privatization, communization, data trusts) based on project needs [10].

- Agreement Drafting: Create clear contracts defining derived data ownership, usage rights, and benefit distribution [9].

- Implementation: Deploy technical controls enforcing the agreed data access and usage policies.

Validation:

- Conduct stakeholder satisfaction surveys

- Audit compliance with agreed data usage terms

- Monitor for data disputes and resolution effectiveness

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Tools for Agricultural AI Research

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ag Image Repository (AgIR) | Open-source plant image collection | 1.5M high-quality images; accessible via USDA SCINet [1] |

| Benchbot Imaging Systems | Automated plant photography | Standardizes image capture across locations and conditions [1] |

| Computer Vision Cut-out Tools | Background removal from plant images | Creates clean training data by isolating plants from complex backgrounds [1] |

| Synthetic Data Generators | Creates artificial training data | Mimics real-world scenarios; helps address data scarcity [7] |

| Federated Learning Platforms | Enables collaborative model training | Allows analysis without centralizing sensitive farm data [8] |

| Data Annotation Software | Streamlines image labeling | Reduces labor-intensive manual annotation [1] |

| NASA GLAM System | Global cropland monitoring | Provides satellite-based agricultural data [11] |

Data Scarcity Impact and Solutions

Quantitative Analysis of Data Challenges

| Aspect | Current Challenge | Potential Impact | Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Data Volume | LLMs exhausting publicly available text data [7] | Reduced AI accuracy and performance [7] | Immediate concern [8] |

| Agricultural Image Data | Lack of public, well-labeled image sets [1] | Limited model generalizability across farms [1] | Being addressed via repositories like AgIR [1] |

| Data Labeling Bottleneck | Manual annotation is time-consuming and expensive [7] | Slows AI development and increases costs [7] | Ongoing challenge |

| Privacy Restrictions | GDPR, CCPA limit data sharing [9] [8] | Hampers AI development in healthcare and finance [8] | Increasing concern |

AI Data Solutions Overview

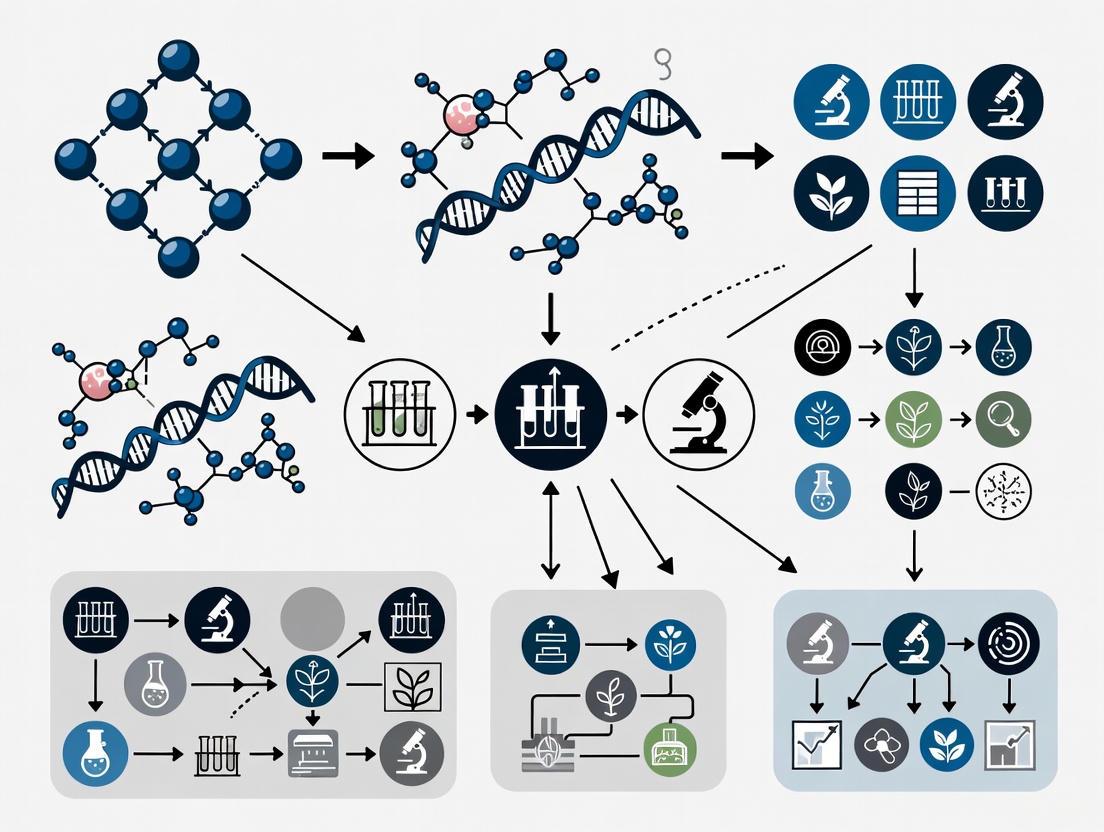

Agricultural AI Data Pipeline

Technical Support Center

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers and scientists navigate the regulatory expectations for data quality in AI models, with a specific focus on challenges related to farm data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core regulatory principle linking data to AI model credibility? Both the FDA and EMA emphasize that the credibility of an AI model's output is fundamentally determined by the quality and relevance of the data used to train and validate it. Regulators assess the model's performance within its specific Context of Use (COU), and this assessment is grounded in the characteristics of the underlying data [13] [14]. A model is considered credible for a regulatory decision only when there is justified trust in its output for a given COU, which is built upon rigorous data management practices [14].

Q2: Our model uses sensitive farm production data. What are the key data documentation requirements? Regulators require transparent documentation of your data's lifecycle to assess potential biases and limitations. Your documentation should cover:

- Provenance: The origin and collection methods of the data, including the specific agricultural environments and conditions [15] [16].

- Processing: A detailed description of all data cleaning, annotation, and pre-processing steps [17] [18].

- Characteristics: A summary of the datasets used, including sources, data points, and the time period of collection [19]. You must also document the representativeness of the data across different farm types, animal breeds, or crop varieties to address algorithmic bias [17] [18].

- Ownership and Rights: Information on data ownership, licensing agreements, and whether data includes copyrighted or patented information, which is crucial for shared agricultural data [20] [19].

Q3: How can we manage data ownership and sharing challenges in multi-farm research projects? Complex data ownership in agricultural consortia can inhibit AI development if not managed properly. Recommended strategies include:

- Structured Governance Frameworks: Implement clear data governance agreements that define control, access, and usage rights among all partners [20].

- Federated Learning: Consider technical solutions like federated learning, which allows model training across decentralized datasets (e.g., on multiple farms) without transferring or centrally storing the raw data. This preserves data privacy and ownership while enabling collaborative model refinement [16].

- Data Marketplaces: Explore regulated data marketplaces where farms can license their data under clear governance agreements, providing AI developers with access to diverse datasets while respecting ownership rights [20].

Q4: We face limited and heterogeneous farm data. What validation strategies are acceptable to regulators? For AI models in agriculture, where large, uniform datasets can be rare, a robust validation strategy is critical. The FDA's risk-based framework suggests that the required level of validation evidence depends on the model's risk and context of use [13] [14]. You can strengthen your validation with:

- Multi-Farm Validation: Validate model performance across data from independent farms not involved in training to demonstrate generalizability [15].

- Transfer Learning and Simulation: Use techniques like transfer learning, or validate models against simulated or synthetic data that accurately represents real-world agricultural conditions [16].

- Continuous Performance Monitoring: Implement plans for ongoing monitoring post-deployment to detect performance drift caused by changes in farming practices, animal genetics, or environmental conditions [17] [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Regulatory feedback indicates potential algorithmic bias in our model. Algorithmic bias often stems from unrepresentative training data.

- Step 1: Conduct a Data Gap Analysis. Audit your training datasets for representation across critical variables in your COU (e.g., different farm sizes, geographic regions, animal demographics, or soil types) [15] [18].

- Step 2: Perform Subgroup Analysis. Re-validate your model's performance specifically on under-represented subgroups to quantify performance disparities [18].

- Step 3: Mitigate and Document. Actively source additional data to fill gaps or apply algorithmic techniques to mitigate identified bias. Document all actions taken, the analysis results, and any remaining model limitations in your submission [17] [18].

Problem: Our AI model's performance has declined since deployment (Model Drift). Performance drift in agriculture can be caused by evolving practices, environmental changes, or new animal diseases.

- Step 1: Establish a Performance Baseline. Define key performance indicators (KPIs) and their acceptable ranges during initial validation [17].

- Step 2: Implement a Monitoring System. Create automated dashboards to track KPIs against the baseline using real-world data streams [16] [18].

- Step 3: Create a Pre-Approved Update Plan. Develop a Predetermined Change Control Plan (PCCP). For the FDA, a PCCP allows you to pre-specify the protocol for retraining the model with new data and the validation steps needed, enabling smoother regulatory approval for updates [18].

Experimental Protocols for Data and Model Credibility

Protocol 1: Data Quality and Representativeness Assessment

- Objective: To ensure training and testing datasets are representative of the target agricultural population and context of use.

- Methodology:

- Define Population Covariates: Identify key variables (e.g., breed, age, farm management system, soil composition, climate zone).

- Stratified Sampling: Collect data using a stratified sampling strategy to ensure all relevant subgroups are represented.

- Data Auditing: Statistically compare the distribution of covariates in your dataset against the known distribution in the target population.

- Gap Documentation: Document any under-represented groups and the potential impact on model performance.

Protocol 2: Model Validation for Generalizability

- Objective: To demonstrate that the AI model performs robustly on data from novel farms or environments not seen during training.

- Methodology:

- Data Partitioning: Split the available data from multiple sources (farms) into three sets: Training, Tuning (validation), and a hold-out Test Set.

- External Validation: The hold-out Test Set should comprise data from entire farms or geographic locations that are completely excluded from the Training and Tuning sets.

- Performance Comparison: Calculate performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, precision, recall) on the Training/Tuning sets and the external Test Set. A minimal drop in performance on the external set indicates good generalizability.

Data Presentation: Regulatory Submission Metrics

Table 1: Quantitative Data Requirements for AI Model Submissions. This table summarizes key data metrics to include in regulatory submissions to the FDA and EMA.

| Data Category | Specific Metric | FDA Guidance Reference | EMA Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset Composition | Number of data points, sources (e.g., # of farms), time period of collection | [13] [14] | Transparency in data sourcing and ownership [17] |

| Data Provenance | Description of data cleaning, processing, and annotation methods | [13] | Documentation of data lineage and processing steps [17] |

| Representativeness | Coverage of key subgroups (e.g., by breed, crop, region, season); analysis of demographic or clinical covariates | Expectation for bias mitigation [18] | Analysis of data across relevant population strata [17] |

| Performance Metrics | Model performance stratified by key subgroups (e.g., sensitivity/specificity by farm type) | Risk-based credibility assessment [14] | Evidence of consistent performance across populations [17] |

Visualization of Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between data governance, model development, and regulatory credibility, as outlined by FDA and EMA guidelines.

Regulatory Credibility Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for AI Research with Agricultural Data. This table details key materials and their functions for developing credible AI models.

| Tool / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Data Governance Platform | Provides the framework for managing data ownership, access controls, and usage policies across multiple farm stakeholders, ensuring compliance and ethical data handling [20]. |

| Federated Learning Framework | Enables model training on decentralized farm datasets without moving raw data, addressing privacy and ownership concerns while allowing for collaborative AI development [16]. |

| Automated Data Labeling Tools | Uses AI (e.g., NLP, computer vision) to accelerate the annotation of unstructured agricultural data, such as clinical notes or images, while maintaining human oversight for accuracy [17]. |

| Bias Detection & Mitigation Software | Provides statistical tools and algorithms to identify potential biases in training datasets and to evaluate model performance fairness across different subgroups [18]. |

| Predetermined Change Control Plan (PCCP) | A regulatory "playbook" that outlines planned future model modifications and the associated validation protocols, facilitating agile and compliant model updates post-deployment [18]. |

The Economic Stakes - The Multi-Billion Dollar Cost of Inefficient Data Use

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: No Assay Window in TR-FRET-based Experiments Problem: The instrument shows no difference in signal between experimental and control groups. Solution:

- Primary Cause: Incorrect instrument setup [21].

- Actionable Steps:

- Consult the instrument setup guides for your specific microplate reader to verify configuration [21].

- Confirm that the correct emission filters are installed. Using the wrong filters is a common reason for assay failure [21].

- Test your reader's TR-FRET setup using control reagents before running your actual experiment [21].

Issue: Inconsistent EC50/IC50 Values Between Labs Problem: Replicating a compound's potency measurement yields different results across laboratories. Solution:

- Primary Cause: Variability in prepared stock solutions, typically at 1 mM concentration [21].

- Actionable Steps:

- Meticulously document the preparation process of all stock solutions, including the solvent used and storage conditions.

- For cell-based assays, consider if the compound's cellular permeability or the activation state of the target kinase could be influencing the results [21].

Issue: Complete Lack of Assay Window in Z'-LYTE Assays Problem: The development reaction shows no difference in the emission ratio between phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated controls. Solution:

- Diagnostic Test:

- For the 100% Phosphopeptide Control: Do not add any development reagent. This should yield the lowest possible ratio [21].

- For the Substrate (0% Phosphopeptide): Use a 10-fold higher concentration of development reagent than standard to ensure complete cleavage. This should yield the highest possible ratio [21].

- Interpretation: A successful test should show a significant (e.g., 10-fold) difference in ratios. If not, the issue likely lies with the development reagent dilution or the instrument setup [21].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I use ratiometric data analysis for my TR-FRET assay? A1: Using the acceptor/donor emission ratio is a best practice. The donor signal acts as an internal reference, accounting for small pipetting variances and lot-to-lot reagent variability, which leads to more robust and reliable data [21].

Q2: My emission ratios look very small. Is this normal? A2: Yes. Because the donor signal is typically much higher than the acceptor signal, the calculated ratio is often less than 1.0. The statistical significance of your data is not affected by the small numerical value [21].

Q3: How do I assess the quality of my assay beyond the size of the assay window? A3: The Z'-factor is a key metric. It considers both the assay window (the difference between the maximum and minimum signals) and the variability (standard deviation) of your data. An assay with a Z'-factor > 0.5 is considered excellent for screening purposes [21].

Q4: Our agricultural AI research involves sharing plant image data. What are the key considerations for our Data Management and Sharing (DMS) Plan? A4: A robust DMS Plan is crucial. For data derived from human research, the plan must specify how external access will be controlled and describe any limitations imposed by informed consent or privacy regulations [22]. Even for plant data, establishing clear plans for data annotation, repository selection (e.g., controlled vs. open access), and metadata standards is essential for enabling collaboration and ensuring your data can be used to train reliable AI models [23] [22].

Q5: What is the difference between "Controlled Access" and "Open Access" for data sharing? A5: Controlled Access involves requirements for accessing data, such as approval by a research review committee or use of secure research environments. Open Access means the data is available to the public without such restrictions. Controlled access is often the standard for sharing sensitive or human-derived research data [22].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Detailed Protocol: Agricultural Image Data Acquisition and Curation for AI

Objective: To collect high-quality, annotated plant images for training robust computer vision models in agricultural AI research [23].

Methodology:

- Hardware Setup:

- Image Acquisition:

- Program the system to conduct multiple passes over the plants each week, creating a longitudinal time series that captures growth and development stages [23].

- The system should capture a wide genetic variety of each plant species under different environmental conditions (e.g., water stress, varying temperatures) to ensure dataset diversity [23].

- Data Annotation and Processing:

- Use specialized software to automate the creation of "cut-outs" (plants removed from their background) and to apply color corrections [23].

- Annotate images with detailed descriptions, including species, growth stage, genetic variety, and environmental conditions. This labeled data is critical for supervised machine learning [23].

- Data Sharing:

- Deposit the curated images and associated metadata into a dedicated repository, such as the Agricultural Research Service's Ag Image Repository (AgIR) on a high-performance computing cluster like SCINet, to make them freely available to the research community [23].

Detailed Protocol: TR-FRET Assay for Compound Screening

Objective: To determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of a compound using Time-Resolved Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (TR-FRET).

Methodology:

- Plate Reader Setup: Verify the instrument is configured for TR-FRET with the correct excitation and emission filters as specified by the assay and instrument manufacturer [21].

- Reagent Preparation: Prepare all reagents according to the kit protocol. For compound testing, create a serial dilution in DMSO, ensuring final DMSO concentrations are consistent across all wells (typically ≤1%) [21].

- Assay Assembly:

- Dispense the kinase, test compound, and substrate/ATP mixture into the assay plate.

- Include controls for 100% phosphorylation (no inhibitor) and 0% phosphorylation (no ATP or substrate only) [21].

- Incubate the plate to allow the kinase reaction to proceed.

- TR-FRET Detection:

- Add the detection reagents (e.g., Terbium-labeled antibody and a FRET-compatible acceptor).

- Read the plate on a compatible microplate reader that measures the time-delayed fluorescence at both the donor and acceptor emission wavelengths.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the emission ratio (Acceptor Emission / Donor Emission) for each well.

- Plot the emission ratio against the logarithm of the compound concentration.

- Fit a sigmoidal dose-response curve to the data to calculate the IC50 value.

- Calculate the Z'-factor using control data to validate assay robustness [21].

The following tables consolidate key quantitative information on economic impact and experimental metrics.

Table 1: Economic Impact of Generative AI and Data Utilization

| Sector / Area | Potential Economic Value | Key Driver / Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Generative AI (Overall Global Impact) | $2.6 - $4.4 trillion annually [24] | Enhanced productivity across customer operations, marketing & sales, software engineering, and R&D [24]. |

| Generative AI (Banking Industry) | $200 - $340 billion annually [24] | Automation of routine tasks and improved customer service operations [24]. |

| Generative AI (Retail & CPG) | $400 - $660 billion annually [24] | Personalized marketing, supply chain optimization, and content creation [24]. |

| Data Factor (China's Provincial Economy) | Positive, nonlinear impact with increasing returns [25] | Digital transformation of traditional production factors (capital, labor), boosting total factor productivity [25]. |

Table 2: Key Experimental Metrics for Assay Validation

| Metric | Definition & Calculation | Interpretation / Benchmark for Success | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z'-Factor | ( Z' = 1 - \frac{(3\sigma{max} + 3\sigma{min})}{ | \mu{max} - \mu{min} | } ) Where ( \sigma ) is standard deviation and ( \mu ) is mean signal. | Z' > 0.5: Excellent assay suitable for screening [21]. |

| Assay Window | (Signal at top of curve) / (Signal at bottom of curve) Alternatively: (Response Ratio at top) - (Response Ratio at bottom). | A larger window is better, but must be evaluated alongside variability (see Z'-Factor) [21]. | ||

| Emission Ratio | Acceptor Signal (e.g., 520 nm or 665 nm) / Donor Signal (e.g., 495 nm or 615 nm). | Normalizes for pipetting and reagent variability; values are typically < 1.0 [21]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item / Solution | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| TR-FRET Detection Kit | Provides labeled antibodies or tracers for Time-Resolved FRET assays, enabling the detection of biomolecular interactions [21]. |

| LanthaScreen Eu/Tb Assay Reagents | Utilize lanthanide chelates (e.g., Europium or Terbium) as donors in TR-FRET assays for studying kinase activity and inhibition [21]. |

| Z'-LYTE Assay Kit | A fluorescence-based, coupled-enzyme assay for measuring kinase activity and inhibitor IC50 values using a ratio-metric readout [21]. |

| Agricultural Image Repository (AgIR) | An open-source repository of over 1.5 million high-quality, annotated plant images for training AI models in agriculture [23]. |

| Benchbot Imaging System | An automated, robotic system for capturing high-resolution, standardized images of plants throughout their growth cycle [23]. |

| Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) | A secure, HIPAA-compliant web application for building and managing online surveys and research databases, supporting data capture for clinical studies [26]. |

Building and Applying Secure AI Data Ecosystems in Pharma R&D

Troubleshooting Guides

Pipeline Failure: Data Ingestion Issues

Q: My pipeline is failing during the data ingestion phase. What are the first steps I should take?

A: Begin by isolating the problem area. Check the connectivity and status of your data sources [27]. For API failures, use tools like Postman or cURL to verify endpoint accessibility and expected responses [28]. Examine logs for error messages, stack traces, and exceptions that can provide immediate clues about the failure [28] [27]. Also, investigate common culprits such as expired API keys, recent code or schema changes, network connectivity issues, or permission changes [28].

Q: How can I troubleshoot inconsistent data quality after ingestion, such as missing plant images or incorrect labels?

A: Implement rigorous data quality verification. Check for missing or incomplete data by ensuring all expected data points are present [27]. Validate that any initial transformations are functioning as expected and not introducing errors [27]. For agricultural image data, this is crucial as subtle differences in a plant's appearance due to genetics or environment can profoundly impact model performance [23]. Cross-check processed data with raw inputs to ensure accuracy and consistency [27].

Pipeline Failure: Data Processing & Transformation

Q: My data processing stage is slow or failing due to resource constraints. How can I diagnose this?

A: Monitor system metrics for CPU, memory, disk I/O, and network utilization, as high resource usage may indicate bottlenecks [27]. If using custom code, use unit tests to isolate and identify logic errors [28] [27]. For large-scale agricultural image processing, ensure your infrastructure, such as GPU clusters, is properly configured to handle the computational load and that cluster management is efficient [29].

Q: How do I handle failures that occur in a multi-layer data architecture (e.g., Medallion Architecture)?

A: A critical best practice is to save data at each stage (e.g., Bronze, Silver, Gold). This allows you to easily isolate the failure point, determine if the issue originated in raw ingestion, cleaning, or final aggregation, and enables targeted debugging and reprocessing of only the affected layer [28]. This is especially valuable when dealing with large agricultural image datasets where re-ingesting from source can be time-consuming [23].

General Pipeline Management

Q: What is a systematic process for troubleshooting a broken pipeline?

A: Follow a logical journey [27]:

- Isolate the Problem: Determine where the failure occurs (ingestion, processing, storage, output) and when it started [27].

- Inspect Logs and Metrics: Check error logs and system metrics for clues [28] [27].

- Verify Data Quality: Ensure data integrity and correct transformations at each stage [27].

- Test Incrementally: Break the pipeline into smaller sections and test each one independently [27].

- Conduct Root Cause Analysis: Once fixed, document the findings to improve future resilience [27].

Q: How can I proactively prevent pipeline failures?

A: Leverage monitoring and alerting tools to get notified of job failures or resource issues early [28] [27]. Maintain comprehensive documentation of past issues and their resolutions, as this can be a lifesaver when rare problems resurface [28]. For agricultural data, this includes documenting data collection conditions (e.g., growth stage, weather) that are critical for model training [23].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the core components of an AI data pipeline? A: A typical AI data pipeline consists of several key stages [29] [27]:

- Ingestion Streams: Collecting data from multiple internal and external sources.

- Database Environment: A system where ingested data is filtered, cleaned, processed, and compressed.

- GPU Cluster: Computational resources for accelerated model training.

- Distribution Catalog: A centralized repository for trained models.

- Content Archive & Model Logs: Storage for the full history of data, models, and decisions for transparency and continuous improvement.

Q: Our agricultural research data is fragmented across many systems. How can an AI pipeline help? A: AI pipelines are specifically designed to tackle fragmented and siloed data [29]. They do this by filtering, formatting, cleaning, and organizing all data as soon as it's ingested, creating a uniform data stream ready for AI training. This is essential for creating reliable models that can account for the variability found in farm fields [23].

Q: What are the common challenges when implementing an AI data pipeline? A: Organizations often face several obstacles [29]:

- Fragmented, Siloed Data: Disorganized data spread across multiple formats and systems.

- System Migration: Reluctance to replace existing systems that cause performance bottlenecks.

- Ensuring Data Integrity & Compliance: Maintaining data security, governance, and transparency.

- Implementation Costs: The upfront investment required for new infrastructure.

Q: Why is saving data at every stage of the pipeline so important? A: Saving intermediate data outputs (e.g., in Bronze, Silver, and Gold layers) provides several critical benefits [28]: easier isolation of failure points, targeted debugging, full data lineage and auditability, and the ability to reprocess only the affected layer, saving significant time and resources.

Q: How can we ensure our AI pipeline remains scalable? A: Building a scalable pipeline requires careful infrastructure consideration [29]. Key elements include implementing scalable AI storage (like flash-based storage) to handle large volumes of data, ensuring sufficient and efficient compute power (like GPU clusters with good management), and automating processes to enable continuous operation and iterative model refinement with minimal human input.

Data Presentation

Table: AI Data Pipeline Development Stages & Specifications

| Pipeline Stage | Core Function | Key Technologies & Actions | Common Failure Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Ingestion | Collect raw data from diverse sources [29]. | APIs, databases, file shares, online datasets [29]. Connect to data sources, validate format/schema [27]. | Expired API keys, schema changes, network issues, source unavailability [28] [27]. |

| Data Processing | Transform raw data into AI-ready format [30] [29]. | Data cleaning, reduction, embedding, transformation [30] [29]. Review transformation logic [27]. | Resource constraints (CPU/memory), logic errors in code, data quality issues [28] [27]. |

| Model Training | Use processed data to train AI/ML models [29]. | GPU clusters for computational acceleration, distributed training [29]. | Insufficient computational power, inadequate data quality/volume for training. |

| Inferencing & Deployment | Serve trained models for predictions [29]. | Distribution catalog for model deployment, inferencing [29]. | Model versioning issues, deployment configuration errors, performance latency. |

| Monitoring & Feedback | Maintain and improve model performance [29]. | Logging prompts/responses, continuous fine-tuning and re-training [29]. | Lack of monitoring/alerting, failure to log data, feedback loops not closed [28]. |

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Agricultural AI Pipelines

| Reagent / Tool | Core Function | Application in Agricultural AI Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ag Image Repository (AgIR) | Open-source repository of high-quality, labeled plant images for training AI models [23]. | Provides the foundational dataset for developing computer vision models for plant identification, weed detection, and growth stage monitoring [23]. |

| Benchbots | Robotic hardware systems for automated, standardized collection of plant images in semi-field conditions [23]. | Automates the tedious and labor-intensive process of field data collection, ensuring consistent, high-quality image data for reliable model training [23]. |

| Annotation Software | Tools to label images with detailed metadata (e.g., species, growth stage, health status) [23]. | Creates the structured, annotated datasets required to supervise the training of machine learning algorithms for precision agriculture tasks [23]. |

| Centralized Logging System | Platform to aggregate logs from various pipeline services for easier analysis [27]. | Crucial for troubleshooting complex pipelines distributed across multiple systems, allowing for quick isolation of failures in data ingestion or processing [27]. |

| Unit & Integration Test Suites | Automated tests for custom data transformation code and pipeline component interactions [28] [27]. | Catches logic errors and integration issues early, preventing data quality problems from propagating downstream and corrupting the AI model's knowledge base [28] [27]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Methodology: Building an Agricultural Image Repository

The following workflow is derived from the process used to create the AgIR repository, which aims to accelerate AI solutions in agriculture by providing a large, public, high-quality image dataset [23].

- Hardware Setup (Benchbots): Deploy wheel-mounted robotic camera systems in a semi-field environment. These bots are programmed to move along an overhead track, capturing highly detailed photos of hundreds of plants in pots arranged in rows. Imaging runs are performed multiple times per week to create a time series as plants grow and develop [23].

- Image Acquisition & Standardization: Program the Benchbots' cameras to capture images meeting exacting scientific standards. This includes consistent lighting, resolution, and angle to ensure all collected images are usable for research and model training [23].

- Data Annotation & "Cut-out" Creation: Use developed software to automate the process of cutting plants out from their image backgrounds and attaching detailed descriptions (metadata) to each image. This includes species, variety, growth stage, and environmental conditions. This step transforms raw images into annotated data suitable for supervised learning [23].

- Data Curation & Repository Population: Compile the annotated images and their associated metadata into a structured, searchable repository (the AgIR). The repository is first made available on high-performance computing clusters (like SCINet) before being released worldwide to agricultural researchers [23].

- Baseline Model Training: Use the curated repository to train and establish baseline machine learning models for tasks like species identification and phenotyping. These proven baselines provide an on-ramp for other researchers to build, test, and improve tools without starting from scratch [23].

Workflow Visualization: Agricultural AI Data Pipeline

Workflow Visualization: Troubleshooting a Data Pipeline

Implementing Federated Learning for Privacy-Preserving Model Training

Federated Learning (FL) represents a fundamental shift in machine learning, enabling multiple entities to collaboratively train AI models without centralizing their data [31] [32]. For agricultural AI research, this approach directly addresses critical challenges of farm data sharing and ownership [33]. Instead of moving sensitive farm data to a central server, FL brings the model to the data—allowing research institutions to develop improved crop models, yield predictors, and diagnostic tools while respecting data sovereignty and complying with evolving data rights regulations in agriculture [33] [34].

Core Federated Learning Workflow

The Federated Averaging (FedAvg) algorithm forms the foundation of most FL systems [31] [35]. The following diagram illustrates this iterative process:

Federated Learning Process Flow

The process consists of four key phases [31] [34]:

- Initialization & Distribution: A central server initializes a global model and distributes it to participating clients (e.g., different farms or research institutions)

- Local Training: Each client trains the received model on their local agricultural data (e.g., sensor readings, yield records, soil samples)

- Update Transmission: Clients send only model updates (gradients or weights), not raw data, back to the server

- Secure Aggregation: The server aggregates these updates to create an improved global model

This cycle repeats for multiple rounds until the model converges [31].

Troubleshooting Common Implementation Issues

System Configuration & Communication Problems

| Issue | Symptoms | Solution | Agricultural Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Client-Server Connection Failures | Clients cannot connect; training hangs at initialization [36] | Ensure FL server port (default 8002) is open for TCP traffic; clients should initiate connections [36] | Rural agricultural settings may have intermittent connectivity; implement retry logic with exponential backoff |

| Client Dropout During Training | Server shows "waiting for minimum clients" for extended periods [36] | Configure heart_beat_timeout on server; use asynchronous aggregation to proceed with available clients [36] |

Farm nodes may disconnect due to poor internet; use flexible client minimums and checkpointing |

| Long Admin Command Delays | Admin commands to clients timeout or respond slowly [36] | Increase default 10-second timeout using set_timeout command; avoid issuing commands during heavy model transfer [36] |

Bandwidth limitations in remote research stations; schedule maintenance during low-activity periods |

| GPU Memory Exhaustion | Client crashes during local training; out-of-memory errors [36] | Reduce batch sizes for memory-constrained devices; use CUDA_VISIBLE_DEVICES to control GPU usage [36] |

Agricultural models with high-resolution imagery may require memory optimization for edge devices |

Model Performance & Convergence Issues

| Issue | Root Cause | Solution | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slow or No Convergence | Non-IID agricultural data; client drift [31] [35] | Implement FedProx with proximal term (μ=0.5); increase local epochs; use adaptive learning rates [31] [37] | local_loss = standard_loss + (0.5/2) * ||w - w_global||^2 |

| Unstable Global Model | Heterogeneous data quality; malicious updates [37] [35] | Deploy anomaly detection; use statistical outlier rejection; implement reputation systems [37] [38] | Validate updates against baseline distribution before aggregation |

| Communication Bottlenecks | Large model updates; limited rural bandwidth [31] [35] | Apply gradient quantization (float32→int8); use sparsification (top 1% gradients) [31] [35] | 4x reduction in payload size; prioritize most significant updates |

| Overfitting to Specific Farms | Data heterogeneity; geographic bias [35] [34] | Implement personalized FL; cluster clients by region or crop type; use transfer learning [35] [34] | Create region-specific model variants with shared base layers |

Advanced Agricultural Data Protection

While FL inherently protects raw data, additional privacy techniques are essential for sensitive farm information. The following diagram shows a comprehensive privacy-preserving architecture:

Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning Architecture

Threat Modeling for Agricultural AI

Different threat models require different protection strategies [38]:

- Honest-but-Curious Adversaries: Eavesdrop on communications but don't actively disrupt (defended via encryption) [38]

- Active/Malicious Adversaries: May modify updates or inject backdoors (requires robust aggregation and anomaly detection) [38]

- Data Reconstruction Attacks: Attempt to infer farm data from model updates (mitigated through differential privacy and secure aggregation) [35] [32]

Experimental Protocols for Agricultural Research

Implementing Federated Averaging with TensorFlow Federated

Data Heterogeneity Management Protocol

Agricultural data is naturally non-IID across different farms [35]. Implement this protocol to ensure robust convergence:

Client Selection Strategy:

- Select farms with diverse geographic representation each round

- Weight updates by dataset size and quality metrics

- Implement stratified sampling by crop type or growing conditions

Personalized FL for Regional Adaptation:

Research Reagent Solutions: FL Frameworks Comparison

| Framework | Primary Use Case | Agricultural Research Suitability | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| TensorFlow Federated (TFF) [31] [34] | Research prototyping | Excellent for algorithm development | Tight TensorFlow integration; strong research community |

| Flower [34] [39] | Production deployment | Ideal for multi-institution trials | Framework agnostic; scales to 10,000+ clients [39] |

| NVIDIA Clara [36] | Medical/imaging applications | Suitable for agricultural image analysis | Multi-GPU support; robust client management |

| PySyft [38] [34] | Privacy-focused research | Excellent for sensitive farm data | Differential privacy; secure multi-party computation |

| FATE [38] [34] | Enterprise cross-silo FL | Suitable for large agribusiness collaborations | Homomorphic encryption; industrial-grade security |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: How can we ensure model fairness when farms have very different data quantities? A: Implement weighted aggregation based on dataset size and quality metrics. Use FedAvg with careful weighting to prevent large farms from dominating the global model [31] [35]. Consider fairness-aware aggregation algorithms that actively monitor and correct for bias.

Q: What happens when a farm loses internet connectivity during training? A: FL systems are designed for resilience. Clients that disconnect will be removed after a configurable timeout (default ~10 minutes) [36]. The server proceeds with available clients, and reconnecting clients receive the current global model to continue participation [36].

Q: Can participants verify that their data isn't being reconstructed from updates? A: Yes, through secure aggregation protocols that mathematically guarantee the server only sees aggregated updates, not individual contributions [31] [35]. Additionally, farms can apply local differential privacy to add noise before sending updates [35] [32].

Q: How do we handle different crop varieties or growing conditions across farms? A: Implement personalized FL approaches where a base global model is adapted locally to specific conditions [35]. Alternatively, cluster farms by similar characteristics and train separate models for each cluster while still benefiting from federated learning privacy.

Q: What metrics should we monitor to ensure FL system health? A: Key metrics include: round completion time, client participation rate, model convergence across client types, privacy budget consumption (if using differential privacy), and detection of anomalous updates [37] [36].

Federated learning provides a technically robust framework for collaborative agricultural AI research while fully respecting farm data ownership [33] [32]. By implementing the troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and privacy architectures detailed in this technical support center, research institutions can advance agricultural AI without compromising the privacy and sovereignty of individual farm data. The frameworks and methodologies continue to mature rapidly, making federated learning an increasingly viable approach for privacy-preserving agricultural innovation [38] [34].

Data Augmentation Techniques to Overcome Scarcity in Biomedical Datasets

FAQs on Data Augmentation Fundamentals

1. What is data augmentation and why is it critical for biomedical AI research?

Data augmentation is a set of strategies that artificially expand training datasets by creating modified versions of existing data [40]. In biomedical research, where collecting new data is often prohibitively expensive, time-consuming, and constrained by privacy regulations, it is a crucial technique for combating overfitting and improving model generalizability [41] [42] [43]. It directly addresses the common "data scarcity" problem, enabling the development of more reliable and robust AI models even with limited initial datasets [44].

2. What is the difference between data augmentation and synthetic data generation?

While the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, a key distinction exists:

- Data Augmentation typically involves applying minor alterations to original data, such as geometric transformations or adding noise [40].

- Synthetic Data Generation often uses advanced models like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to create entirely new, artificial data points from scratch [43] [40]. For most applications, augmented data derived from original images is preferred due to its closer resemblance to real-world data, whereas synthetic data can be used when the resemblance to original data is less critical or to generate entirely new data distributions [40].

3. When should I consider using data augmentation in my project?

You should almost always consider data augmentation. It is particularly beneficial when [45] [44]:

- Your dataset is small or medium-sized.

- You are working with imbalanced classes; you can augment the underrepresented classes to create a more balanced dataset.

- Your model shows signs of overfitting—performing well on training data but poorly on validation or test data. The only scenario where you might skip it is if your dataset is already exceptionally large and diverse, covering all expected variations [45].

4. How do data ownership concerns impact data augmentation in biomedical research?

Data ownership dictates who has the rights to control, access, and use data [20]. Overly restrictive data policies or fragmented data silos can inhibit AI development by limiting the datasets available for training and augmentation [20]. Adhering to governance frameworks like the FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) can enhance data sharing while maintaining privacy and ownership rights [46]. Furthermore, techniques like federated learning allow AI models to be trained on decentralized data across multiple institutions without directly sharing the raw data, thus respecting data ownership [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: My Model is Overfitting to the Training Data

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The training dataset is too small or lacks diversity, causing the model to memorize noise and specific examples rather than learning generalizable patterns.

- Solution: Implement a robust online data augmentation pipeline.

- Action: Apply a combination of transformations on-the-fly during training (online augmentation) so the model never sees the exact same example twice [45]. A good starting point includes affine transformations (e.g., random rotation, flipping, scaling, shearing) and pixel-level transformations (e.g., adjusting brightness/contrast, adding blur or noise) [45] [43].

- Advanced Strategy: For image data, also include random erasing methods (e.g., Cutout, Random Erasing). These force the model to learn to identify objects from multiple parts rather than relying on a single most distinct feature [45].

Problem 2: Choosing the Wrong Augmentation Techniques for My Data Type

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Applying transformations that generate unrealistic or clinically implausible data, which can confuse the model and degrade performance.

- Solution: Select augmentations based on domain knowledge of your data and task.

- Action: Consult the table below for technique recommendations based on biomedical data type. For instance, vertically flipping a fundus image of a retina might be acceptable, but vertically flipping a CT scan where organ positioning matters is not [45] [42].

- Action: Use automated tools like RandAugment or Albumentations to experiment with different combinations of transformations and select the one that maximizes performance on your validation set [45].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Augmentation Techniques Across Medical Image Types [42]

| Imaging Modality | Top-Performing Augmentation Techniques | Reported Impact on Performance (e.g., Accuracy) |

|---|---|---|

| Brain MRI | Rotation, Noise Addition, Sharpening, Translation | Accuracy up to 94.06% for tumor classification [42] |

| Lung CT | Affine Transformations (Scaling, Rotation), Elastic Deformation | Significant increase in segmentation accuracy [42] [43] |

| Breast Mammography | Affine and Pixel-level Transformations, Generative Models (GANs) | Highest performance gains for classification and detection tasks [43] |

| Eye Fundus | Geometric Transformations, Color Space Adjustments | Improved performance in disease classification and segmentation [42] |

Problem 3: Handling Severe Class Imbalance

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: One or more classes have significantly fewer examples than others, biasing the model toward the majority class.

- Solution: Use targeted augmentation to rebalance the dataset.

- Action: Focus your augmentation efforts only on the underrepresented classes. Instead of applying transformations uniformly to all images, apply them more heavily to the smaller classes until all classes have a similar number of examples [45].

- Advanced Strategy: For complex cases, use Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to synthesize high-quality, artificial examples of the rare class, which can be more diverse and realistic than simple transformations [42] [43].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Augmentation Techniques for Image Classification

This protocol provides a standardized way to evaluate which augmentation strategy works best for a specific image-based task.

1. Objective: To quantitatively compare the effectiveness of different data augmentation techniques in improving the performance of a deep learning model for biomedical image classification.

2. Materials (The Scientist's Toolkit):

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Tool | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Curated Biomedical Dataset | A labeled dataset (e.g., brain MRIs, lung CTs) split into training, validation, and test sets. |

| Deep Learning Framework | Software like PyTorch or TensorFlow for building and training models. |

| Data Augmentation Library | Libraries such as Albumentations, TorchIO (for medical images), or TensorFlow's ImageDataGenerator to apply transformations [45] [44]. |

| Base CNN Model | A standard convolutional neural network architecture (e.g., ResNet, DenseNet) used as the baseline classifier. |

| Computational Resources | GPUs with sufficient memory for training deep learning models. |

3. Methodology:

- Baseline Establishment: Train your chosen CNN model on the original, non-augmented training set. Evaluate its performance on the fixed validation set to establish a baseline accuracy.

- Augmentation Strategy Definition: Define several augmentation pipelines to test. For example:

- Pipeline A (Geometric): Random rotation (±15°), horizontal flip, random zoom.

- Pipeline B (Photometric): Random adjustments to brightness, contrast, and saturation.

- Pipeline C (Advanced): A combination of geometric transformations and a noise-adding operation.

- Pipeline D (Synthetic): Use a pre-trained GAN to generate synthetic images for the training set.

- Model Training & Evaluation: For each augmentation pipeline, train a new instance of the CNN model from scratch on the augmented data. Use online augmentation, meaning images are transformed randomly each epoch [45]. Record the final performance of each model on the same validation set.

- Analysis: Compare the validation performance of all models (baseline and augmented). The augmentation strategy that yields the highest performance gain is the most effective for your specific dataset and task.

4. Workflow Visualization:

Protocol 2: Data Augmentation for Biomedical Text (Factoid Question Answering)

This protocol is based on a study that systematically evaluated seven augmentation methods for biomedical question-answering tasks [47].

1. Objective: To improve the performance of a transformer-based model on a biomedical factoid question-answering task using text data augmentation.

2. Methodology Summary:

The experiment involved using data from the BIOASQ challenge. The following augmentation methods were tested [47]:

- Back-translation: Translating text to another language and then back to the original.

- Information Retrieval: Using retrieved passages from a large corpus as additional context.

- WORD2VEC-based Substitution: Replacing words with their semantic synonyms using WORD2VEC embeddings.

- Masked Language Modeling: Using a model like BERT to predict and replace masked words in a sentence.

- Question Generation: Automatically generating new question-answer pairs.

- Context Extension: Extending the given passage with additional relevant context.

- Using an Artificial MRC Dataset: Incorporating a separately created machine reading comprehension dataset.

3. Key Finding:

The study concluded that one of the simplest methods, WORD2VEC-based word substitution, performed the best and is highly recommended for such NLP tasks in the biomedical domain [47]. This shows that complex methods are not always the most effective.

Advanced Techniques and Governance

Logical Framework for Selecting an Augmentation Strategy

The following diagram outlines a decision-making process for choosing the most appropriate data augmentation technique based on your project's constraints and data characteristics.

Connecting to Data Governance: The CHDO Framework

In the context of a thesis addressing data sharing and ownership (like farm data), it is crucial to recognize that technical solutions like augmentation exist within a governance framework. The Collaborative Healthcare Data Ownership (CHDO) framework proposed for integrative healthcare offers a valuable model [10]. It emphasizes:

- Shared Ownership: Recognizing the rights of multiple stakeholders (data subjects, providers, researchers).

- Defined Access and Control: Clear policies on who can access data and for what purposes, including augmentation for AI research.

- Transparent Governance: Ensuring all data usage, including the creation of augmented or synthetic datasets, is conducted ethically and transparently [10]. Applying a similar framework to farm data can help overcome barriers to data sharing, enabling the use of augmentation techniques to build better AI models for agricultural science while respecting data ownership.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: Our AI model for target identification is underperforming. What could be the issue?

- A: This is often a data quality issue. Ensure your training data is comprehensive, accurate, and relevant to the biological context [48]. Incomplete or outdated datasets can significantly hamper model performance. Verify the data's lineage and implement rigorous bias detection techniques to prevent skewed results [20] [5].

FAQ: How can we accelerate patient recruitment for our AI-optimized clinical trial?

- A: Leverage AI-powered tools to analyze Electronic Health Records (EHRs) and genetic databases to identify eligible patients based on specific molecular and clinical characteristics [49] [50]. Ensure your data governance framework includes protocols for handling this sensitive personal data in compliance with regulations like HIPAA and GDPR [20] [5].

FAQ: We are concerned about data drift affecting our predictive toxicology model. How can we monitor this?

- A: Implement automated statistical monitoring for data drift. Key methods include:

- KL Divergence Test: Measures how one probability distribution diverges from a second reference distribution.

- Population Stability Index (PSI): Monitors changes in the distribution of a variable over time. Regular computation of these metrics will alert you to model degradation, allowing for timely retraining [48].

FAQ: What are the key data governance challenges when repurposing an existing drug for a new indication with AI?

- A: The primary challenges involve data integration and ownership. You must merge diverse datasets (clinical, molecular) which may reside in silos with different ownership rights [20]. A robust governance framework is needed to ensure you have the legal rights to use this data for a new purpose, that it is ethically sourced, and that the resulting intellectual property is clearly defined [5] [51].

Quantitative Data on AI in Drug Development

Table 1: Comparative Performance of AI-Discovered vs. Traditionally Discovered Drugs

| Metric | AI-Discovered Drugs | Traditionally Discovered Drugs |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 Clinical Trial Success Rate | 80% - 90% | 40% - 65% [50] |

| Average Time for Candidate Identification | Can be as low as 18 months for specific cases (e.g., idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis) [49] | Often exceeds 4-5 years [50] |

| Cost of Development | Significant reduction by accelerating steps and reducing late-stage failures [49] [50] | Averages over $2 billion [50] |

Table 2: Key AI Applications and Their Data Requirements Across the Drug Development Pipeline

| Development Phase | AI Application | Essential Data Types | Common Data Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery | Target Identification, Virtual Screening, Molecular Modeling [49] [52] | Genomic, proteomic, protein structures (e.g., AlphaFold database), chemical libraries [49] [50] | Data quality, fragmentation across silos, high cost of access [20] [49] |

| Preclinical | Predictive Toxicology, Drug Repurposing [49] [50] | Preclinical study data, drug-target interaction databases, high-throughput screening data [49] | Data bias, small dataset sizes for rare events, "black box" interpretability [49] [50] |

| Clinical Trials | Patient Stratification, Trial Design Optimization, Outcome Prediction [49] [50] | Electronic Health Records (EHRs), medical imaging, omics data, real-world evidence [49] | Privacy concerns (GDPR, CCPA), data anonymization, interoperability between systems [5] [48] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: AI-Driven Target Identification and Validation

Objective: To identify and validate novel disease-associated protein targets using AI.

Methodology:

- Data Curation: Assemble a diverse and high-quality dataset from public and proprietary sources. This includes genomic data (e.g., from RNA-seq samples), proteomic data, and known protein-protein interactions [49] [50].

- Model Training: Employ machine learning models, such as Deep Learning (DL) and reinforcement learning, to analyze the curated data. The model is trained to recognize patterns and relationships between genetic variations, protein functions, and disease phenotypes [49] [52].

- Target Prediction: The trained model processes the data to uncover and prioritize potential drug targets (proteins or genes) based on their predicted causal role in the disease and "druggability" [50].

- Validation via Molecular Modeling: Validate predicted targets by analyzing their 3D structure, often using AI systems like AlphaFold to predict protein folding. This helps confirm that the target has a suitable binding site for a potential drug molecule [49] [50].

Protocol 2: AI for Clinical Trial Patient Stratification

Objective: To use AI to identify a subpopulation of patients most likely to respond to a treatment.

Methodology:

- Data Aggregation: Integrate multimodal data from Electronic Health Records (EHRs), genetic databases (genomics), and medical imaging [49] [50].

- Feature Engineering: Use Natural Language Processing (NLP) to extract structured information from unstructured clinical notes. Identify key biomarkers and clinical features from the aggregated data.

- Predictive Modeling: Apply clustering algorithms and supervised machine learning models to the processed data. These models identify complex patterns that link patient characteristics to historical treatment outcomes.

- Cohort Definition: The model defines a specific patient cohort based on the identified predictive features (e.g., specific genetic mutations combined with a clinical history). This cohort is then recruited for the clinical trial [49].

Workflow Diagrams

AI-Driven Target Identification Workflow

AI-Powered Patient Stratification Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential AI Platforms and Data Tools for Drug Discovery

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Experiment |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Database [49] [50] | Data Resource / AI Model | Provides highly accurate predicted protein structures. | Validates drug targets by understanding 3D structure and binding sites. |

| AI-Powered Virtual Screening Platforms (e.g., Atomwise) [49] | AI Software Platform | Uses convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to predict molecular interactions for millions of compounds. | Accelerates hit identification in target-based screens. |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [49] | AI Algorithm | Generates novel molecular structures with desired properties. | Designs new chemical entities for synthesis and testing in lead optimization. |

| Electronic Health Record (EHR) Systems [49] | Data Resource | Contains real-world patient clinical data. | Sources data for patient stratification models in clinical trial design. |

| Bias Detection Frameworks (e.g., Fairlearn) [48] | AI Governance Tool | Uses statistical metrics to identify bias in training datasets. | Ensures fairness and representativeness in models used for patient selection. |

Solving Data Sharing, Ownership, and Compliance Hurdles

Navigating Intellectual Property for AI-Generated Drug Candidates

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Inventorship Determination Errors

Problem: Uncertainty in identifying the correct human inventor for AI-generated drug candidates, leading to patent rejection risks.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Step | Action | Documentation Required | Regulatory Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Map the AI-human interaction points in the drug discovery workflow. | Process flowchart showing decision points | USPTO 2024 Inventorship Guidance [53] |

| 2 | Identify where human researchers provided "significant contribution" to conception. | Research logs, model training records, meeting notes | USPTO "Significant Contribution" Standard [54] [53] |

| 3 | Verify all listed inventors are natural persons. | Inventor declaration forms | Thaler v. Vidal Precedent [55] [53] |

| 4 | Conduct pre-filing inventorship audit. | Audit checklist, contribution assessment matrix | FDA AI Documentation Standards [56] [57] |

Prevention: Implement continuous documentation practices throughout AI drug discovery process. Maintain laboratory notebooks specifically recording human decisions in model training, output interpretation, and candidate selection [53].

Guide 2: Addressing Patent Eligibility Challenges

Problem: AI-generated drug candidates facing novelty, non-obviousness, or enablement rejections.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Challenge | Diagnostic Indicators | Solution Approach | Success Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novelty Issues | AI replicates prior art from training data | Use proprietary datasets; conduct comprehensive prior art search | Novel compound structure with no similar published compounds [53] |

| Non-obviousness | AI output appears obvious in hindsight | Document unpredictable results; use SHAP explanations | Demonstration of unexpected therapeutic properties [53] |

| Enablement Failures | Insufficient synthesis detail | Provide detailed manufacturing protocols; file CIP applications | Patent enables skilled artisan to reproduce invention [53] |

| Written Description | Poor understanding of AI decision pathway | Implement explainable AI (XAI); document structural features | Clear correlation between structure and function [53] [58] |

Experimental Protocol for Non-obviousness Demonstration: