Nanosensors vs. Conventional Sensors: A 2025 Benchmarking Guide for Agricultural Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive benchmarking analysis for researchers and scientists evaluating the transition from conventional agricultural sensors to emerging nanosensor technologies.

Nanosensors vs. Conventional Sensors: A 2025 Benchmarking Guide for Agricultural Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive benchmarking analysis for researchers and scientists evaluating the transition from conventional agricultural sensors to emerging nanosensor technologies. It explores the foundational principles of both sensor classes, detailing the unique physicochemical properties of nanomaterials that enable enhanced sensitivity and real-time analysis. The scope extends to methodological applications in soil, crop, and climate monitoring, troubleshooting of integration and data management challenges, and a direct performance comparison on key metrics like detection limits, cost, and scalability. Synthesizing current research and field data, this analysis aims to equip professionals with the evidence needed to make informed decisions for integrating advanced sensing into agricultural research and development.

Sensor Fundamentals: Unpacking the Core Technologies from Macro to Nano

In the evolving landscape of precision agriculture, conventional agricultural sensors form the technological backbone that enables data-driven decision-making. These sensors function as the critical interface between the physical conditions of the farm and the digital management systems that interpret this data. Conventional agricultural sensors are defined as devices that respond to physical, chemical, or biological parameters in the agricultural environment and convert these measurements into quantifiable electrical or optical signals [1]. Unlike their emerging nanosensor counterparts, these conventional technologies have established field-proven applications and form the current market dominance in precision farming solutions.

The operational framework for these sensors consistently follows a tripartite architecture: a sensitive element that directly interacts with the measured parameter (e.g., temperature, humidity, nutrient content), a conversion element that transforms the physical or chemical change into an electrical signal, and a measurement circuit that processes this signal for subsequent data interpretation and action [1]. This fundamental principle governs the functionality of diverse sensor types across agricultural applications, from soil monitoring to climate control and yield optimization. The global agricultural sensor market reflects the entrenched position of these technologies, with soil management applications alone representing 34% of the market share in 2024 [2].

Classification and Operational Principles of Conventional Sensors

Conventional agricultural sensors can be systematically categorized based on their target parameters and underlying detection mechanisms. The operational principles dictate their application specificity, performance characteristics, and integration requirements within precision farming systems.

Physical Sensors for Environmental Monitoring

Humidity sensors demonstrate two predominant working principles in agricultural applications: capacitive and resistive sensing. Capacitive humidity sensors operate on the principle of dielectric constant changes in a hygroscopic material sandwiched between two electrodes forming a capacitor. When water vapor molecules enter the sensing layer, the dielectric constant changes, directly altering the capacitance value which is then converted to a measurable electrical signal corresponding to relative humidity [1]. These sensors typically employ polymers like polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) or ceramic materials such as porous alumina as the humidity-sensitive dielectric layer, prized for their high responsiveness to water molecules and stability in harsh agricultural environments [1].

Resistive air humidity sensors utilize moisture-sensitive materials whose electrical resistance varies significantly with changes in ambient humidity. When humidity increases, the moisture-sensitive material adsorbs water molecules, creating closer contact between conductive particles and reducing resistance. Conversely, decreasing humidity causes water molecule release, increasing particle distance and raising resistance values [1]. The internal circuitry detects these resistance changes and converts them into corresponding humidity readings. While generally less expensive than capacitive sensors, resistive variants may exhibit slower response times and reduced long-term stability in fluctuating agricultural environments.

Temperature and humidity sensors collectively enable microclimate monitoring essential for greenhouse control, pest and disease prediction, and crop scheduling. These sensors provide critical data for managing environmental extremes that could impact crop development and resource allocation decisions [3].

Mechanical and Electrochemical Sensors for Soil Analysis

Soil moisture sensors dominate the conventional sensor landscape, accounting for 28% of the agricultural sensor market in 2024 [2]. These devices employ various technologies including time-domain reflectometry (TDR), frequency-domain reflectometry (FDR), and capacitance methods to measure soil water content. The operational principle common to these techniques involves measuring the dielectric constant of soil, which changes dramatically with water content due to water's high dielectric constant (~80) compared to soil minerals (~3-5) and air (~1) [3]. These sensors provide real-time data for precision irrigation, significantly conserving water resources while maintaining optimal root zone conditions.

Electrochemical sensors deliver critical information about soil chemistry through several detection principles. Potentiometric sensors measure voltage (electromotive force) between reference and indicator electrodes to determine specific ion activities, primarily used for soil pH monitoring. Voltammetric sensors apply a controlled potential and measure the resulting current, enabling detection of multiple ions simultaneously, particularly beneficial for measuring nutrient concentrations like nitrates and phosphates in soil solutions [3]. Conductimetric sensors measure the electrical conductivity of soils, correlating to salinity levels and dissolved ion content, which is vital for managing soil health in irrigated agriculture.

Nutrient sensors specifically target essential plant nutrients including nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) through both direct and indirect measurement approaches. Optical nutrient sensors frequently employ absorption spectroscopy principles where specific nutrients absorb characteristic wavelengths of light, while electrochemical approaches utilize ion-selective electrodes that generate potentials proportional to the logarithm of specific ion activities [3]. These technologies enable precision fertilization, reducing waste and environmental impact while maintaining optimal plant nutrition.

Optical Sensors for Crop Health Assessment

Optical sensors leverage light reflectance and remote sensing technologies to assess vegetation health, detect stress, and monitor growth stages. These sensors typically operate on the principle that plant pigments (chlorophyll, carotenoids) and cellular structures interact with specific wavelengths of light, creating spectral signatures that correlate with physiological status [3]. Multispectral sensors capture reflectance data at specific wavelength bands including visible and near-infrared regions, while hyperspectral sensors provide higher spectral resolution across contiguous bands.

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) represents one of the most established applications of optical sensing, calculating the ratio between reflected near-infrared and red light to assess plant health and density [3]. Healthier vegetation with more chlorophyll strongly absorbs red light for photosynthesis while reflecting more near-infrared light due to cellular structure, yielding higher NDVI values. These sensors enable early detection of stress, disease, or nutrient deficiencies before visible symptoms appear, allowing for targeted interventions across large agricultural areas.

Table 1: Conventional Agricultural Sensors: Operating Principles and Performance Characteristics

| Sensor Category | Specific Sensor Type | Operating Principle | Measured Parameters | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Sensors | Capacitive Humidity | Dielectric constant change in hygroscopic material | Relative Humidity | Sensitivity: 0.1% RH; Accuracy: ±1-2% RH [1] |

| Resistive Humidity | Electrical resistance change in moisture-sensitive material | Relative Humidity | Accuracy: ±3-5% RH; Slower response time [1] | |

| Soil Moisture (TDR/FDR) | Dielectric constant measurement of soil | Volumetric Water Content | Accuracy: ±2-3%; Market share: 28% (2024) [2] | |

| Electrochemical Sensors | Potentiometric | Voltage measurement between reference/indicator electrodes | pH, Specific Ions | pH Resolution: 0.01 pH; Ion-specific detection [3] |

| Voltammetric | Current measurement under controlled potential | Multiple ions simultaneously | Multi-ion detection; sub-ppm detection limits | |

| Conductimetric | Electrical conductivity measurement | Soil Salinity, Dissolved Ions | Correlation to salt content; Range: 0-20 dS/m | |

| Optical Sensors | NDVI (Multispectral) | Ratio of NIR to red light reflectance | Vegetation Health, Biomass | Early stress detection; Yield correlation: 10-12% improvement [3] |

| Nutrient Sensors | Light absorption at characteristic wavelengths | N, P, K concentrations | Non-destructive assessment; ~8% yield improvement [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Performance Benchmarking

Robust experimental methodologies are essential for evaluating conventional sensor performance under controlled laboratory conditions and authentic field environments. Standardized protocols enable meaningful comparison between conventional and emerging nanosenor technologies.

Laboratory Calibration and Characterization Protocol

Objective: To establish baseline accuracy, sensitivity, detection limits, and response characteristics of conventional agricultural sensors under controlled conditions.

Materials and Equipment:

- Sensor units under investigation (minimum n=5 for statistical significance)

- Certified reference materials or analytical standards specific to target analytes

- Environmental chamber for temperature and humidity control (operating range: -10°C to 60°C, 10-95% RH)

- Data acquisition system with minimum sampling frequency of 1 Hz

- Standard laboratory instruments for validation (e.g., precision balance, pH meter, spectrophotometer)

Procedure:

- Sensor Conditioning: Activate sensors according to manufacturer specifications and stabilize in controlled environment (25°C, 50% RH) for 24 hours before initial measurements.

- Accuracy Assessment: Expose sensors to minimum five concentration levels of target analytes using certified reference standards. For humidity sensors, utilize saturated salt solutions generating specific RH levels (11%-97% RH) in sealed chambers [1].

- Response Time Determination: Subject sensors to step changes in analyte concentration while recording output at 1-second intervals. Calculate response time as duration to reach 90% of final stable reading.

- Sensitivity Calculation: Determine slope of calibration curve (sensor output versus analyte concentration) across linear working range.

- Repeatability Evaluation: Perform minimum seven replicate measurements at mid-range concentration, calculating coefficient of variation.

- Temperature Compensation: Characterize sensor output across operational temperature range (0-50°C) at constant analyte concentration to establish temperature compensation algorithms.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate root mean square error (RMSE) between sensor readings and reference values

- Determine limit of detection (LOD) as three times standard deviation of blank measurements

- Establish measurement uncertainty through propagation of error analysis

Field Validation Protocol for Agricultural Applications

Objective: To evaluate sensor performance, durability, and reliability under actual agricultural operating conditions.

Experimental Design:

- Site Selection: Identify multiple representative field locations with varying soil types, topography, and microclimate conditions

- Sensor Deployment: Install sensors according to agricultural guidelines (e.g., soil sensors at multiple depths within root zone)

- Reference Sampling: Collect and laboratory-analyze physical samples (soil, water, plant tissue) coincident with sensor measurements using standardized protocols [3]

- Temporal Framework: Conduct continuous monitoring for minimum one complete growing season with periodic performance verification

Parameters Quantified:

- Field Accuracy: Correlation between sensor readings and laboratory analysis of co-located samples

- Operational Reliability: Percentage of operational time without failure or drift requiring recalibration

- Environmental Resilience: Performance maintenance under extreme conditions (precipitation, temperature spikes, mechanical disturbance)

- Data Consistency: Long-term stability of measurements without recalibration

Statistical Analysis:

- Compute concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) between sensor data and reference methods

- Perform analysis of variance (ANOVA) to identify significant performance differences across environmental conditions

- Calculate mean time between failures (MTBF) for reliability assessment

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

The benchmarking of conventional agricultural sensors reveals distinct performance patterns across sensor categories, with trade-offs between accuracy, reliability, cost, and operational requirements.

Table 2: Comparative Performance Benchmarking of Conventional Agricultural Sensors

| Sensor Type | Accuracy | Response Time | Field Reliability | Cost Index | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacitive Humidity | ±1-2% RH | 10-30 seconds | High (>90% uptime) | Medium | Calibration drift in dusty conditions [1] |

| Resistive Humidity | ±3-5% RH | 30-60 seconds | Medium (75-85% uptime) | Low | Contamination sensitivity, slower response [1] |

| Soil Moisture (TDR) | ±2-3% VWC | Near-instantaneous | High | High | Soil-specific calibration required [2] |

| Electrochemical pH | ±0.1 pH | 30-90 seconds | Low-Medium (frequent recalibration) | Low-Medium | Reference electrode drift, soil contact dependency |

| Optical NDVI | ±0.05 NDVI units | Immediate (satellite) | Very High | Varies widely | Atmospheric interference, limited depth information |

| Nutrient Sensors (Ion-Selective) | ±10-15% concentration | 60-120 seconds | Low (fouling issues) | Medium | Ion interference, regular membrane replacement |

The data reveals several key trends in conventional sensor performance. Physical sensors (humidity, soil moisture) generally demonstrate superior field reliability and faster response times compared to electrochemical alternatives, making them well-suited for automated control systems in precision agriculture. However, electrochemical sensors provide unique capabilities for specific chemical parameter measurement despite requiring more intensive maintenance and demonstrating lower field reliability. Optical sensors offer exceptional spatial coverage and immediate response but face limitations regarding depth penetration and atmospheric dependencies.

The implementation challenges for conventional sensors significantly impact their operational effectiveness in agricultural settings. Environmental factors including soil compaction, temperature extremes, and chemical exposure contribute to calibration drift and measurement inaccuracies. Technical limitations such as power requirements, connectivity issues in rural areas, and specialized installation needs create barriers to widespread adoption, particularly for smallholder farmers [2]. The financial considerations extend beyond initial acquisition costs to include ongoing maintenance, calibration, and data management expenses that collectively impact the total cost of ownership.

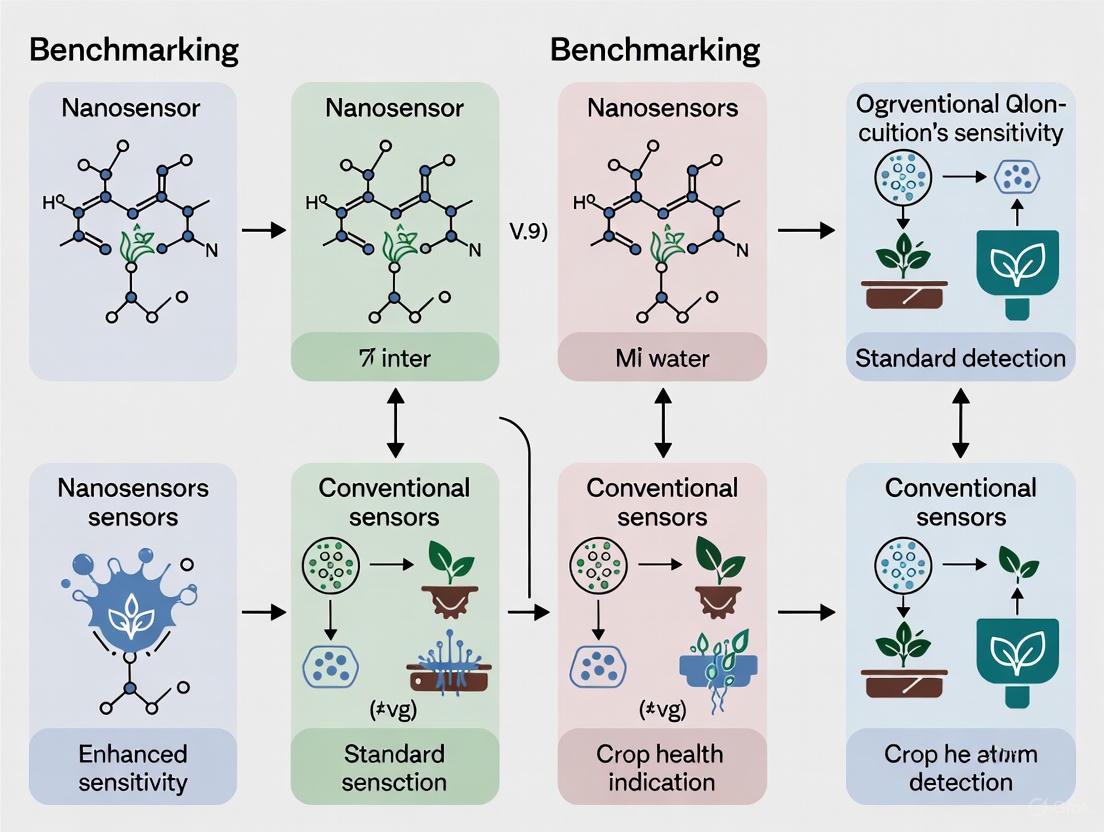

Visualization of Sensor Operational Frameworks

The functional relationships and operational workflows of conventional agricultural sensors can be visualized through structured diagrams that highlight their core operating principles and data pathways.

Operational Architecture of Conventional Agricultural Sensors

Comparative Performance Evaluation Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Sensor Evaluation

The experimental evaluation of conventional agricultural sensors requires specific reagents, reference materials, and calibration standards to ensure accurate performance assessment and valid comparative analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Sensor Performance Evaluation

| Reagent/Material | Technical Specification | Primary Application | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated Salt Solutions | Lithium chloride, Magnesium chloride, Sodium chloride, Potassium sulfate, Potassium nitrate | Humidity sensor calibration | Generate specific relative humidity levels (11%-97% RH) in sealed environments for sensor calibration [1] |

| Certified Reference Materials | NIST-traceable soil/water standards with certified analyte concentrations | Sensor accuracy validation | Provide verified analyte concentrations for establishing measurement accuracy and detection limits |

| Buffer Solutions | pH 4.01, 7.00, 10.01 ±0.02 at 25°C | pH sensor calibration | Establish calibration curve and verify sensor response across pH range |

| Ion Standard Solutions | 1000 ppm stock solutions of NO₃⁻, NH₄⁺, K⁺, PO₄³⁻ | Nutrient sensor evaluation | Prepare concentration gradients for sensitivity determination and interference testing |

| Dielectric Reference Materials | Certified materials with known dielectric constants | Soil moisture sensor validation | Verify sensor response to known dielectric properties independent of soil-specific factors |

| Conductivity Standards | KCl solutions at specified conductivities (e.g., 1413 μS/cm) | Salinity sensor calibration | Establish correlation between sensor output and solution conductivity |

The selection and proper application of these research reagents directly impacts the validity and reproducibility of sensor performance data. Certified reference materials with established traceability to national standards provide the foundation for accuracy claims, while specialized solutions like saturated salt salts enable controlled environmental conditioning. Proper handling, storage, and documentation of these materials according to manufacturer specifications is essential for maintaining experimental integrity throughout the benchmarking process.

Conventional agricultural sensors employ well-established operational principles that have been refined through decades of field application and technological iteration. Their operational frameworks—based on measurable changes in electrical, optical, or chemical properties in response to environmental parameters—provide reliable performance for precision agriculture applications. The comparative performance data reveals a consistent pattern of trade-offs, with physical sensors generally demonstrating superior field reliability while electrochemical alternatives offer specific chemical sensing capabilities despite greater maintenance requirements.

The established infrastructure, comparative affordability, and proven reliability of conventional sensors in controlled agricultural environments maintain their position as the foundational technology for precision agriculture. Their operational principles and performance characteristics provide the essential baseline against which emerging nanosensor technologies must demonstrate not only superior theoretical performance but also practical advantages in complex, real-world agricultural environments. This comparative framework establishes the critical reference point for meaningful advancement in agricultural sensing technologies.

Modern agriculture faces the dual challenge of enhancing productivity to ensure food security while minimizing its environmental footprint. Central to this challenge is the precise monitoring of key agricultural parameters, from soil conditions to pesticide residues. Conventional sensors and analytical methods, while effective, are often constrained by their limited sensitivity, selectivity, portability, and the need for skilled personnel and sophisticated laboratory infrastructure. The emergence of nanosensors, which exploit the unique physicochemical properties of nanoscale materials, presents a paradigm shift. These devices offer the potential for rapid, sensitive, and on-site analysis, enabling real-time decision-making. This guide provides an objective comparison between nanosensors and conventional agricultural sensors, underpinned by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to serve as a benchmark for researchers and development professionals in the field.

Performance Comparison: Nanosensors vs. Conventional Analytical Methods

The superiority of nanosensors is evident from direct comparisons of key analytical metrics. The table below summarizes experimental data for the detection of pesticides, a major area of agricultural concern, contrasting traditional chromatography with advanced nanosensing platforms.

Table 1: Performance comparison of conventional and nanosensor-based pesticide detection methods.

| Detection Method | Target Pesticide | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Analysis Time | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas Chromatography (GC) | Various Organochlorines | Low (ppt-ppb) [4] | Hours (incl. sample prep) [4] | High sensitivity, established standard | Costly equipment, requires skilled personnel, not portable [4] |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | Various Carbamates | Low (ppt-ppb) [4] | Hours (incl. sample prep) [4] | High sensitivity, broad applicability | Time-consuming, complex sample prep, not for on-site use [4] |

| Electrochemical Nanosensor (AChE Inhibition) | Organophosphorus (OP) | 0.38 pM [4] | Minutes [4] | Ultra-sensitive, rapid, potential for portability | Measures total OP, not specific compounds [4] |

| Colorimetric Nanozyme Sensor (Paper-based) | Malathion (OP) | 0.08 mg/L [4] | ~10 minutes [4] | Low-cost, visual/ smartphone readout, user-friendly | Less sensitive than some other nanosensors [4] |

Quantitative data reveals that nanosensors can achieve exceptional sensitivity, rivaling or even surpassing gold-standard laboratory techniques, as demonstrated by the 0.38 pM LOD for OPs [4]. The most significant advantage, however, lies in analysis speed and portability. Nanosensors reduce detection times from hours to minutes, enabling real-time monitoring and on-site decision-making, which is not feasible with conventional chromatography [4]. Furthermore, the development of platforms like paper-based sensors and microfluidic chips significantly lowers costs and simplifies operation, making advanced analytical capabilities accessible without sophisticated laboratory infrastructure [4].

Experimental Protocols for Nanosensor Benchmarking

To ensure consistent and comparable performance evaluation, researchers must adhere to detailed experimental protocols. The following section outlines standard methodologies for key nanosensor types used in agricultural applications.

Protocol for Fluorescence-Based Nanosensor Characterization

This protocol is applicable to nanosensors like Carbon Dots (CDs) or Quantum Dots (QDs) used for detecting ions or pH.

- Nanosensor Synthesis: Synthesize pH-sensitive Carbon Dots (CDs) via a one-step reaction from a single precursor (e.g., Rhodamine B) to ensure biocompatibility and stability across a broad pH range (1-11) [5].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a series of standard buffer solutions covering the pH range of interest (e.g., 1 to 11). Introduce the CD nanosensors into each buffer solution.

- Data Acquisition & Imaging:

- Use Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) for quantitative measurement [5] [6].

- Record the fluorescence lifetime (τ) of the CDs at each pH level. The lifetime should exhibit a pseudo-linear response to pH changes due to protonation/deprotonation of the CD surface [5].

- For intracellular studies (e.g., monitoring lysosomal pH), incubate living cells (e.g., human skin fibroblasts) with the CD nanosensors. Apply FLIM to quantify fluorescence lifetime and map pH distribution within cellular organelles [5].

- Data Analysis: Plot the fluorescence lifetime (τ) against pH to generate a calibration curve. This self-referencing relationship allows for the precise quantification of pH in unknown samples [5].

Protocol for Electrochemical Nanosensor for Pesticide Detection

This protocol details the standard methodology for enzyme inhibition-based nanosensors.

- Sensor Fabrication: Functionalize a transducer surface (e.g., a screen-printed electrode) with nanomaterials (e.g., CdTe Quantum Dots) and the enzyme Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) [4].

- Baseline Measurement:

- Introduce the substrate acetylthiocholine (ATCh) to the sensor.

- AChE catalyzes ATCh hydrolysis, producing thiocholine, which quenches the fluorescence of QDs (or generates an electrochemical signal) [4].

- Record the signal (e.g., fluorescence intensity or current) as the baseline.

- Inhibition Phase: Expose the sensor to a sample containing Organophosphorus (OP) pesticides. OPs inhibit AChE activity.

- Signal Measurement Post-Inhibition: Re-introduce ATCh. The inhibited AChE results in reduced production of thiocholine, leading to a recovery of the QD fluorescence (or a diminished electrochemical signal) [4].

- Quantification: The degree of signal recovery is inversely proportional to the OP concentration. Compare the signal to a calibration curve obtained with OP standards to determine the concentration in the unknown sample [4].

Benchmarking In Vivo Nanosensor Performance

For a standardized comparison of delivery and targeting efficiency across nanosensor platforms, a pre-clinical benchmarking protocol is recommended.

- Animal Model: Use athymic Nu/Nu mice with subcutaneously implanted LS174T cells [7].

- Tumor Growth: Allow tumors to grow to a standardized size of 8–10 mm in diameter [7].

- Nanosensor Administration: Inject a fixed dose of nanosensors, e.g., 10^13 particles per mouse, via a relevant route [7].

- Pharmacokinetics & Biodistribution: At fixed time points post-injection (e.g., 6, 24, and 48 hours), collect blood and tissues (e.g., tumor, liver, spleen). Quantify nanosensor concentration in each sample and report as % Injected Dose (%ID) and %ID per gram of tissue (%ID/g) [7].

- Physicochemical Reporting: Fully characterize the nanosensors' size, shape, composition, surface chemistry, and zeta potential, as these properties critically influence performance [7].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The enhanced functionality of nanosensors arises from their unique transduction mechanisms at the nanoscale. The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental workflows and signaling principles.

Fluorescence Lifetime Sensing Mechanism

Diagram Title: Carbon Dot pH Sensing via FLIM

This diagram visualizes the mechanism of Carbon Dot (CD)-based pH sensing. In an acidic environment, the CD surface becomes protonated. This protonation event alters the electronic structure of the CD, leading to a measurable change in its fluorescence lifetime (τ). Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) detects this lifetime shift, which is independent of sensor concentration, allowing for the creation of a quantitative pH map without the need for internal calibration [5] [6].

Enzyme Inhibition Pesticide Detection

Diagram Title: Enzyme Inhibition Pesticide Detection

This workflow outlines the principle of enzymatic nanosensors for pesticide detection. The active AChE enzyme hydrolyzes the substrate ATCh, producing thiocholine which quenches a quantum dot's fluorescence, generating a signal. When an Organophosphorus pesticide is introduced, it inhibits the AChE enzyme. Upon re-adding the substrate, the inhibited enzyme cannot produce thiocholine, leading to a recovery of the fluorescence signal. The degree of signal recovery is proportional to the pesticide concentration [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The development and deployment of high-performance nanosensors rely on a specific set of materials and reagents. The following table details essential components and their functions in agricultural nanosensor research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Agricultural Nanosensor Development.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Biorecognition Element: Key enzyme for detecting organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides via inhibition mechanism [4]. | Must be stabilized when immobilized on nanosurfaces; critical for sensor selectivity and stability [4]. |

| Carbon Dots (CDs) | Fluorescent Transducer: Nanoscale carbon material used for optical sensing of pH and ions; offers biocompatibility and photostability [5]. | Can be synthesized from various precursors (e.g., Rhodamine B); fluorescence lifetime is pH-dependent [5]. |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Signal Reporter: Semiconductor nanoparticles used in fluorescence-based assays; offer high photostability and tunable emission [6]. | Used in FRET-based sensors and as fluorescent labels in inhibition assays (e.g., CdTe QDs) [4] [6]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Biomimetic Receptor: Synthetic polymers with tailor-made cavities for specific molecular recognition, offering an alternative to biological receptors [4]. | Provide high stability and lower cost than antibodies; used as recognition elements in sensor design [4]. |

| Aptamers | Synthetic Bioreceptor: Single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that bind specific targets with high affinity; selected via SELEX [8]. | Offer high stability and design flexibility; can be selected for pesticides, toxins, or other analytes [8]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Transducer Platform: Low-cost, disposable, and portable electrochemical cells ideal for field-deployable sensor design [4]. | Enable miniaturization and mass production of electrochemical nanosensors for on-site testing [4]. |

The quantitative data and standardized protocols presented in this guide objectively demonstrate that nanosensors leverage their unique nanoscale properties to overcome critical limitations of conventional agricultural sensors. The benchmarked performance—marked by superior sensitivity, rapid analysis, and potential for on-site, user-friendly operation—solidifies their role in the future of precision agriculture. For researchers, the path forward involves not only refining sensor design but also addressing challenges such as environmental impact and cost-effective mass production [9] [4]. By adhering to rigorous benchmarking standards, the scientific community can accelerate the translation of these revolutionary tools from the laboratory to the field, ultimately contributing to more sustainable and productive agricultural practices.

The advancement of precision agriculture is fundamentally linked to our ability to monitor agricultural environments with unprecedented accuracy and specificity. At the heart of this monitoring capability are sensors, devices that transform chemical or biological stimuli into quantifiable signals [10]. The performance, reliability, and applicability of these sensors are dictated by their core components: the sensing elements (or recognition elements) that provide selectivity by interacting with specific target analytes, and the transduction materials that convert this recognition event into a measurable electrical or optical signal [11] [12].

This guide provides a structured comparison of these critical components, benchmarking emerging nanosensors against conventional agricultural sensors. It is designed to equip researchers and scientists with the empirical data and methodological frameworks needed to select appropriate materials for specific agricultural sensing applications, from detecting pesticide residues in food products to monitoring soil health in real-time [11] [13].

Sensing Elements: A Comparison of Recognition Mechanisms

Sensing elements define the selectivity of a sensor. These components are engineered to bind specifically to a target analyte, initiating the sensing process. The choice of recognition element is crucial, as it determines the sensor's specificity, stability in complex matrices (like soil or food products), and overall practicality for field use [11].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Sensing Elements in Agricultural Sensors

| Sensing Element | Mechanism of Action | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations | Exemplary Agricultural Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymes (e.g., AChE) | Catalytic inhibition or substrate conversion [11]. | High catalytic activity and specificity; well-understood mechanisms [11]. | Limited stability and shelf-life; sensitive to environmental conditions (pH, temperature) [11]. | Detection of organophosphorus pesticides via AChE inhibition [11]. |

| Antibodies | High-affinity antigen-antibody binding [11]. | Exceptional specificity and affinity for target molecules. | Complex and costly production; susceptible to denaturation; large size can limit diffusion [11]. | Immunoassays for mycotoxins or specific pesticide classes. |

| Aptamers (ssDNA/RNA) | Folding into 3D structures that bind targets with high affinity [11]. | Chemical stability; in vitro selection; small size; reusability [11]. | Susceptibility to nuclease degradation; potential for nonspecific binding in complex matrices. | Detection of small molecules like antibiotics or pesticides in food [11]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic polymers with tailor-made cavities complementary to the target analyte [11]. | High physical/chemical robustness; stability in harsh conditions; lower cost [11]. | Challenges with homogeneity and reproducibility of binding sites; slower binding kinetics. | Solid-phase extraction and sensing of pesticides in complex food samples [11]. |

| Ion-Selective Membranes (e.g., VEN-TPB ion-pair) | Selective partitioning of ions at the membrane-sample interface, generating a potential difference [14]. | Excellent selectivity for specific ions; proven long-term stability; suitable for miniaturization [14]. | Requires careful membrane formulation; can be sensitive to lipophilic interferents. | Potentiometric detection of soil macronutrients (e.g., K+, NO3-) or drug residues [14]. |

Transduction Materials: Converting Recognition into Readable Signals

Once a recognition event occurs, transduction materials transform it into a quantifiable output. The nature of this material directly impacts the sensor's sensitivity, detection limit, and suitability for integration into portable or wireless devices [12] [14].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Transduction Materials and Mechanisms

| Transduction Mechanism | Transduction Material Examples | Signal Output | Detection Limit/Sensitivity | Advantages & Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Multi-Walled Carbon Nan nanotubes (MWCNTs), Polyaniline (PANI), Ferrocene [14]. | Change in potential, current, or impedance [11] [14]. | MWCNT-based SC-ISEs demonstrated LOD of 3.8 × 10⁻⁶ mol/L for VEN [14]. | + High sensitivity, portability, low cost [11]. – Can be susceptible to signal drift (mitigated by good SC materials) [14]. |

| Optical | Quantum Dots (CdTe), Gold Nanoparticles, Upconverting Nanoparticles [11] [12]. | Change in fluorescence, color, or absorbance [11] [12]. | CdTe QD-based sensor for OPs: LOD of 0.38 pM [11]. CuONP-based colorimetric sensor: LOD of 0.08 mg/L [11]. | + Suited for multiplexing and visual readout [11] [12]. – Instrumentation can be bulky; signal can be interfered with by ambient light or sample turbidity. |

| Magnetic | Iron Oxide Nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄) [12]. | Change in transverse relaxation time (T₂) of water protons [12]. | Used for detection of pathogens and organic pollutants [12]. | + Minimal interference from complex sample matrices [12]. – Lower sensitivity compared to optical/electrochemical methods; requires NMR relaxometry [12]. |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow and material involvement in a nanosensor's operation, from analyte binding to signal output.

Benchmarking Nanosensors Against Conventional Counterparts

The integration of nanotechnology into sensor design has led to significant performance enhancements. The tables below provide a quantitative and qualitative comparison between nanosensors and conventional sensors for key agricultural applications.

Table 3: Quantitative Performance Benchmarking: Pesticide Residue Detection

| Sensor Type | Specific Technology | Target Analyte | Detection Limit | Analysis Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) | Multi-class pesticides | ~ppb level | >30 minutes (incl. sample prep) | [11] |

| Nanosensor | CdTe Quantum Dot Fluorescent Microfluidic Sensor | Organophosphorus Pesticides | 0.38 pM (sub-ppb) | Rapid | [11] |

| Nanosensor | CuO Nanozyme Paper-based Device | Malathion | 0.08 mg/L (ppb) | ~10 minutes | [11] |

Table 4: Qualitative Functional Benchmarking for Agricultural Applications

| Characteristic | Conventional Sensors / Methods | Nanosensors | Implication for Agricultural Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Moderate to High | Very High (single-molecule potential) [12] | Enables detection of trace contaminants (e.g., pesticides) at biologically relevant levels [11]. |

| Selectivity | Relies on separation (e.g., HPLC) or biological specificity. | Engineered specificity via aptamers, MIPs, and functionalized NPs [11] [12]. | Reduces false positives/negatives in complex matrices like soil extracts or food homogenates. |

| Multiplexing | Limited; typically requires multiple instruments. | High potential for simultaneous multi-analyte detection on a single platform [12]. | Comprehensive profiling of soil health or food safety from a single sample, saving time and cost [12]. |

| Portability & On-site Use | Mostly lab-bound, benchtop instruments. | High (e.g., paper-based strips, handheld meters) [11] [13]. | Enables real-time decision-making in the field for precision farming and rapid food safety screening. |

| Cost & Accessibility | High capital and maintenance cost. | Potential for low-cost, disposable sensors [11]. | Makes advanced sensing accessible to a wider range of users, including in developing regions. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Nanosensor Assays

To facilitate replication and further innovation, this section outlines detailed methodologies for two representative nanosensor assays cited in the comparison tables.

Protocol 1: Fluorescent Microfluidic Sensor for Organophosphorus Pesticides

This protocol is based on the work of Hu et al., who developed a sensor using a 3D CdTe Quantum Dot (QD) aerogel [11].

- Primary Materials: CdTe QDs, Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme, Acetylthiocholine (ATCh) substrate, Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) for microfluidic chip fabrication.

- Apparatus: Fluorescence spectrometer, Microfluidic chip fabrication equipment, Syringe pump.

Procedure:

- QD Aerogel Synthesis: Synthesize CdTe QDs and assemble them into a 3D porous aerogel structure within the microfluidic channel. This aerogel serves as the high-surface-area fluorescence transduction material.

- Sensor Operation:

- Step 1: Introduce a solution containing AChE and its substrate, ATCh, into the microfluidic chip.

- Step 2: AChE catalyzes the hydrolysis of ATCh to produce thiocholine.

- Step 3: Thiocholine causes quenching of the red fluorescence emitted by the CdTe QD aerogel via a photoinduced electron transfer mechanism.

- Step 4: In the presence of Organophosphorus Pesticides, AChE is inhibited. This prevents the formation of thiocholine, and the QD fluorescence remains unquenched.

- Detection & Quantification: Measure the recovery of fluorescence intensity, which is directly proportional to the concentration of the inhibiting pesticide. The system achieved a detection limit of 0.38 pM [11].

Protocol 2: Potentiometric Solid-Contact Ion-Selective Electrode (SC-ISE)

This protocol is adapted from the comparative study of transduction materials by the authors of Scientific Reports, using Venlafaxine detection as a model system [14].

- Primary Materials: Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs), Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC), Plasticizer (o-NPOE), Ionophore (VEN-TPB ion-pair), Tetrahydrofuran (THF) solvent.

- Apparatus: Potentiometer (pH/mV meter), Screen-printed electrodes, Electrochemical Impedance Spectrometer.

Procedure:

- Transducer Layer Preparation: Drop-cast a dispersion of MWCNTs onto the screen-printed electrode surface and allow to dry. This forms the solid-contact layer responsible for ion-to-electron transduction.

- Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM) Formulation: Prepare a membrane cocktail containing the polymer (PVC), plasticizer (o-NPOE), and the selective ionophore (VEN-TPB). Dissolve these components in THF.

- Sensor Fabrication: Drop-cast the ISM cocktail directly onto the MWCNT-modified electrode and allow the THF to evaporate, forming a thin, uniform polymeric membrane.

- Conditioning & Measurement: Condition the fabricated sensor in a solution of the target analyte. Perform potentiometric measurements against a standard reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl).

- Performance Characterization:

- Use Chronopotentiometry (CP) to evaluate potential drift and calculate the electrode's capacitance. MWCNTs exhibited a low potential drift of 34.6 µV/s, indicating high stability [14].

- Use Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) to analyze charge transfer resistance and double-layer capacitance.

The diagram below summarizes the architecture and working principle of this SC-ISE.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful development and fabrication of high-performance nanosensors require a suite of specialized materials and reagents. The following table catalogs key components for the research laboratory.

Table 5: Essential Research Materials for Nanosensor Development

| Category | Specific Item / Material | Critical Function in R&D | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanomaterials | Quantum Dots (CdTe, CdSe) | Fluorescent transduction labels with tunable emission [11]. | Optical detection of pesticides via fluorescence quenching [11]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | High-surface-area transducers for electrochemical sensors; enhance capacitance and stability [14]. | Solid-Contact in Ion-Selective Electrodes [14]. | |

| Metal Nanoparticles (Au, Ag, CuO) | Colorimetric reporters, enzyme mimics (nanozymes), SERS substrates [11]. | Peroxidase-like nanozyme in paper-based pesticide sensors [11]. | |

| Recognition Elements | Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) | Enzyme inhibitor for organophosphorus/carbamate pesticide detection [11]. | Core recognition element in enzymatic inhibition-based biosensors [11]. |

| Aptamers | Synthetic recognition elements for small molecules, selected via SELEX [11]. | Target-specific detection of antibiotics, toxins, or pesticides [11]. | |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic, robust antibody mimics with tailored binding cavities [11]. | Solid-phase extraction and sensing of analytes in complex food samples [11]. | |

| Polymer & Chemistries | Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | Matrix polymer for ion-selective membranes [14]. | Forming the bulk of the sensing membrane in potentiometric sensors [14]. |

| Plasticizers (o-NPOE) | Imparts mobility to ionophores within the PVC membrane [14]. | Critical for proper function and Nernstian response of ISEs [14]. | |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Solvent for dissolving PVC and membrane components [14]. | Casting homogeneous ion-selective membranes on electrode surfaces [14]. |

The strategic selection of sensing and transduction materials is paramount to pushing the boundaries of agricultural sensing. As this guide has demonstrated, nanomaterials offer a compelling suite of advantages—including dramatic gains in sensitivity, the potential for miniaturization and multiplexing, and the development of robust, field-deployable platforms—when benchmarked against conventional sensor technologies [11] [12] [14].

Future research trajectories are clearly focused on overcoming remaining challenges, such as ensuring the long-term environmental fate of nanomaterials and reducing costs for widespread adoption [9] [15]. The integration of these nanosensors with Internet of Things (IoT) platforms and data analytics is set to revolutionize precision agriculture, enabling fully autonomous, data-driven farming systems that optimize resource use and ensure food safety and security [10] [16] [13]. For researchers, the continued exploration of novel materials like single-atom nanozymes [11] and the refinement of biocompatible and biodegradable nanostructures will be critical to the next generation of sustainable and highly sensitive agricultural sensors.

The transition toward data-driven farming relies on accurate measurement of key agricultural parameters, including soil moisture, nutrient levels, pathogen presence, and climate conditions. This guide provides a systematic comparison between emerging nanosensors and conventional agricultural sensors, offering a benchmarking framework for researchers and development professionals. The evaluation is structured around performance metrics critical for scientific and commercial applications: sensitivity, detection speed, operational complexity, and cost-effectiveness.

Nanotechnology introduces novel sensing mechanisms that operate at molecular and atomic scales, leveraging unique properties of nanomaterials such as quantum dots, carbon nanotubes, and metal oxides [17]. These platforms demonstrate distinct advantages for real-time, high-resolution monitoring in complex agricultural matrices. Concurrently, conventional sensors continue to evolve through integration with IoT networks and advanced analytics, maintaining relevance in many practical applications [18]. This analysis synthesizes experimental data and performance characteristics to objectively quantify technological capabilities across both sensing paradigms.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Sensor Technologies

Quantitative Benchmarking of Sensor Performance

Table 1: Comparative analysis of sensor technologies for agricultural monitoring

| Measurand | Sensor Technology | Detection Principle | Sensitivity/LOD | Response Time | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil Moisture | Gravimetric (Conventional) | Oven-drying & weighing | N/A (Direct measure) | 24+ hours | High accuracy; Standard reference method | Destructive; Labor-intensive; No real-time capability [19] |

| Soil Moisture Probes (e.g., TDR, FDR) | Dielectric constant measurement | ±2-3% VWC | 1-60 seconds | Continuous monitoring; Reliable | Limited spatial coverage; Calibration dependent [19] [20] | |

| Nanosensors (Graphene, CNTs) | Chemiresistive/Dielectric changes | ±0.5-1% VWC | <10 seconds | High sensitivity; Miniaturization potential; Stable under humidity changes [17] [21] | Scalability challenges; Higher unit cost [22] | |

| Soil Nutrients | Laboratory Analysis (Conventional) | Spectroscopy/Chromatography | ppm-ppb range | Days to weeks | High accuracy; Multi-nutrient analysis | Laboratory-bound; Time-consuming; Expensive [20] |

| Ion-Selective Electrodes (Conventional) | Potentiometric | ~1-10 ppm | 1-2 minutes | Field-deployable; Direct measurement | Interference issues; Regular calibration needed [20] | |

| Nanosensors (Electrochemical) | Functionalized nanoparticles | ppt-ppb range | <30 seconds | Extreme sensitivity; Multi-analyte detection; Portable [23] [22] | Biofouling susceptibility; Complex fabrication [24] | |

| Pathogens | ELISA/PCR (Conventional) | Immunoassay/Nucleic acid amplification | ~1-10 ng/mL | 4-48 hours | High specificity; Established protocols | Laboratory-bound; Skilled personnel; Complex sample prep [25] |

| Nanobiosensors (Quantum dots, Au NPs) | FRET/Electrochemical | ~0.1-1 ng/mL | 15-60 minutes | Rapid detection; Point-of-care capability; High specificity [23] [25] | Limited multiplexing; Sample matrix effects [25] | |

| Climate Parameters | Standard Weather Stations | Various (e.g., thermistors, anemometers) | Varies by parameter | Seconds to minutes | Long-term reliability; Well-established | Large footprint; Expensive for dense networks [18] |

| Nano-Enhanced Sensors (e.g., CO₂) | Optical/Chemiresistive | ~1-5 ppm for CO₂ | <1 minute | Miniaturized; Low power; High density deployment | Emerging technology; Long-term stability data limited [20] |

Technology Adoption Trends and Market Analysis

The global nanosensors market, valued at approximately USD 832 million in 2024, is projected to reach USD 1,838 million by 2034, growing at a CAGR of 8.25% [22]. The broader agricultural nanotechnology market demonstrates even more rapid expansion, expected to grow from USD 8,437 million in 2024 to USD 27,027 million by 2032, at a CAGR of 15.66% [24]. This robust growth reflects increasing research investment and commercial adoption of nano-enabled solutions.

Regional adoption patterns show North America currently leading with 33% market share in nanosensors, while the Asia-Pacific region is projected to grow most rapidly (CAGR 9.32%) between 2025-2034, driven by increasing demand for efficient disease detection tools and adoption across diverse industries [22]. By 2025, over 80% of large farms are expected to adopt advanced data analytics for crop management, creating infrastructure for integration of sophisticated sensing technologies [18].

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Benchmarking

Standardized Methodologies for Performance Validation

Protocol for Soil Nutrient Sensor Evaluation

Objective: Quantify sensitivity, selectivity, and detection limits of nutrient sensors in agricultural soil matrices.

Materials:

- Test sensors (conventional ion-selective electrodes and nanomaterial-based electrochemical sensors)

- Standard reference solutions (NO₃⁻, NH₄⁺, PO₄³⁻ at 0.1-1000 ppm)

- Soil samples with varying texture (sandy, loam, clay) and organic matter content

- Buffer solutions (pH 4.0, 6.0, 8.0)

- Potentiostat for electrochemical measurements

- Reference analytical equipment (HPLC, ICP-MS)

Procedure:

- Prepare soil extracts by mixing 10g soil with 50ml deionized water, shaking for 30 minutes, and filtering through 0.45μm membrane.

- Spike samples with known concentrations of target nutrients across expected physiological range (0.1-500 ppm).

- Immerse both conventional and nanosensors in identical samples with continuous measurement.

- Record response time to reach 90% signal stabilization.

- Calculate sensitivity from calibration curves of signal versus concentration.

- Determine selectivity by measuring response to potential interferents (K⁺, Ca²⁺, Cl⁻) at 10-fold higher concentrations.

- Validate measurements against reference analytical methods (HPLC for nitrate/phosphate, ICP-MS for cations).

Data Analysis: Calculate limit of detection (LOD = 3.3 × σ/S, where σ is standard deviation of blank and S is slope of calibration curve), accuracy (% deviation from reference method), and precision (% RSD of replicate measurements) [23] [20].

Protocol for Pathogen Detection Sensor Evaluation

Objective: Compare detection capabilities for plant pathogens between traditional molecular methods and nanobiosensors.

Materials:

- Pathogen cultures (Xanthomonas campestris, Fusarium oxysporum)

- Plant tissue samples (healthy and infected)

- Traditional PCR/ELISA kits

- Nanobiosensors (quantum dot-based FRET sensors, gold nanoparticle immunoassays)

- Fluorescence spectrometer

- Microplate reader

Procedure:

- Prepare serial dilutions of pathogen cultures (10¹-10⁸ CFU/mL) or pathogen DNA (0.1-1000 pg/μL).

- Spike healthy plant extracts with known pathogen concentrations.

- Process samples in parallel with traditional methods (DNA extraction followed by PCR for molecular detection, antibody-based ELISA for protein detection) and nanobiosensors.

- For quantum dot FRET sensors, measure fluorescence emission before and after sample application.

- Record time-to-result for each method.

- Determine detection limits for each technology.

- Assess specificity using closely related non-target pathogens.

Data Analysis: Compare LOD, total assay time, hands-on time, and accuracy (false positive/negative rates) across technologies [25].

Conceptual Framework for Sensor Technology Benchmarking

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Agricultural Sensor Development

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for agricultural sensor development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Key Characteristics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene & Carbon Nanotubes | Transducer element | Chemiresistive gas sensors (NH₃), soil moisture sensors | High surface area, excellent electron transfer, tunable functionality [17] [21] | |

| Quantum Dots (CdSe, CdTe) | Fluorescent tags | FRET-based pathogen detection, nutrient imaging | Size-tunable emission, high quantum yield, photostability [25] | |

| Metal Nanoparticles (Au, Ag) | Signal amplification | Colorimetric pathogen detection, electrochemical biosensors | Surface plasmon resonance, catalytic activity, biocompatibility [25] | |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers | Recognition element | Biomimetic sensors for toxins, pesticides | Synthetic antibody mimics, thermal/chemical stability [23] | |

| Ion-Selective Membranes | Selective detection | Conventional nutrient ion sensors (NO₃⁻, K⁺) | Moderate selectivity, established manufacturing [20] | |

| Enzymes (Glucose Oxidase, Urease) | Biorecognition element | Conventional biosensors | High specificity, natural recognition | Limited stability, narrow operating conditions [20] |

| Microfluidic Chips | Sample processing | Lab-on-a-chip systems, point-of-care devices | Minimal reagent consumption, automation potential | Complex fabrication, clogging risks [23] |

The benchmarking analysis reveals a complementary relationship between nanosensors and conventional agricultural sensors, with optimal technology selection dependent on specific application requirements. Nanosensors demonstrate superior performance in sensitivity (ppt-ppb detection limits), response time (seconds to minutes), and miniaturization potential, making them ideal for research applications requiring high-resolution data and early pathogen detection [17] [23] [25]. Conventional sensors maintain advantages in cost-effectiveness, field robustness, and technological maturity for large-scale monitoring applications [18] [20].

Future research priorities should address critical nanosensor limitations, including scalability challenges, long-term environmental impact assessment, and standardization of fabrication protocols [22] [21]. Emerging opportunities exist in multimodal sensor systems that integrate nanotechnology's sensitivity with conventional platforms' practicality, potentially bridged by hybrid approaches [23] [24]. The ongoing integration of sensor technologies with IoT platforms and machine learning analytics will further enhance the value proposition of both conventional and nano-enabled sensing approaches, ultimately supporting more sustainable and productive agricultural systems [18] [21].

From Lab to Field: Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Modern Farming

The pursuit of sustainable agricultural productivity necessitates a paradigm shift from generalized farming practices to precision soil management. This approach relies on accurate, real-time monitoring of critical soil parameters like pH and nutrient levels to optimize resource usage and enhance crop yield [26]. The core of this transition lies in the evolution of sensing technologies, moving from conventional electrochemical sensors toward emerging nanobiosensors [27] [28]. This guide provides a objective performance comparison between these two classes of sensors, framing the analysis within a broader research context of benchmarking nanosensors against conventional alternatives. We summarize quantitative data from experimental observations, detail standardized methodologies for performance evaluation, and provide essential resources for researchers and scientists engaged in agricultural technology and sensor development.

The fundamental difference between conventional and nano-enabled sensors lies in the materials used and their resulting performance characteristics.

Conventional Soil Sensors typically use glass-bodied or epoxy-bodied electrodes with macroscopic sensing components. They operate on established electrochemical principles, such as potentiometry for pH measurement, and are valued for their maturity and reliability in field conditions [29] [30].

Nanosensors, particularly nanobiosensors, incorporate nanomaterials such as nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes, or quantum dots as integral components [26] [31]. Their operation leverages the unique properties of these nanomaterials, including an exceptionally high surface area-to-volume ratio, quantum effects, and enhanced electrochemical or optical activity. This often results in superior sensitivity and the ability to detect specific biological analytes, such as pathogens or nutrients, at remarkably low concentrations [26] [27].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Sensor Types

| Feature | Conventional Sensors | Nanosensors (Nanobiosensors) |

|---|---|---|

| Key Materials | Glass, epoxy, liquid electrolytes | Nanoparticles (Au, Ag), Carbon Nanotubes, Graphene, Quantum Dots [26] [31] |

| Sensing Mechanism | Potentiometric, Voltammetric | Electrochemical, Optical (FRET, SERS), Mass-sensitive [26] [31] |

| Primary Advantage | Proven field durability, Lower unit cost | Ultra-high sensitivity, Specificity, Miniaturization potential [26] [27] |

| Typical Targets | pH, macronutrients (N, P, K), moisture | pH, specific ions, pesticides, pathogens, plant hormones [26] [28] |

Performance Benchmarking: Experimental Data and Comparison

To quantitatively assess the capabilities of both sensor types, we have compiled data from published experimental results and product specifications. The following tables summarize key performance metrics for pH monitoring and the detection of other agriculturally relevant analytes.

Table 2: Benchmarking pH Monitoring Capabilities

| Sensor Type / Product | Technology | Accuracy | Response Time | Key Features & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atlas Scientific Lab Grade | Conventional (Polycarbonate) | ±0.002 pH | ~1 second (to 95%) | Double junction, yearly calibration, 2.5+ year lifespan [29] |

| Atlas Scientific Spear Tip | Conventional (Spear Tip) | ±0.002 pH | ~1 second (to 95%) | For semi-solid materials like soil; lab-grade precision [30] |

| Apera PH60S | Conventional (Handheld) | ±0.01 pH | Not specified | All-in-one handheld meter; good for field use [30] |

| Au NP-based Sensor | Nanosensor (Optical) | ~5 µM (Urea) [26] | Not specified | Colorimetric detection; high specificity but requires complex readout [26] |

Table 3: Benchmarking Performance for Other Agricultural Analytes

| Target Analyte | Sensor Technology | Detection Mechanism | Reported Sensitivity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organophosphate Pesticides | Carbon Nanotubes | Electrochemical | 0.145 parts per billion (ppb) | [26] |

| Methyl parathion & chlorpyrifos | Carbon Nanotubes wrapped by ssDNA | Enzymatic Reaction | 1 × 10⁻¹² M | [26] |

| R. solanacearum bacteria | Gold Nanoparticles (functionalized) | Colorimetry | 15 nanograms | [26] |

| Urea | Gold Nanoparticles | Colorimetry | 5 µM | [26] |

| Soil Moisture | Conventional (e.g., Probeync) | Electrical Impedance | Not specified (±0.2 pH accuracy) | [32] |

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Benchmarking

For research aimed at reproducing or validating these benchmarks, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following methodologies outline key procedures for assessing sensor performance.

Protocol for Quantifying pH Sensor Accuracy and Response Time

This protocol is adapted from industry-standard calibration and testing methods for pH electrodes [29] [30].

Sensor Calibration:

- Reagents: Use at least two standard pH buffer solutions (e.g., pH 4.01, 7.00, and 10.01).

- Procedure: Immerse the sensor probe in the first buffer solution under gentle agitation. Record the stabilized reading and adjust the sensor's calibration to match the known buffer value. Rinse the probe with deionized water and repeat the process with the second and third buffers. A double-junction reference design is recommended for enhanced reliability in complex matrices like soil solutions [29].

Accuracy Measurement:

- Reagents: Prepare a series of test solutions with known pH values using standard buffers.

- Procedure: Immerse the calibrated sensor into each test solution. Record the stabilized pH reading. The accuracy is calculated as the absolute difference between the measured value and the known value of the test solution.

Response Time Measurement:

- Procedure: Transfer the sensor from one buffer solution (e.g., pH 7.00) to a second one with a significantly different pH (e.g., pH 4.01). Record the pH reading at a high frequency (e.g., 10 times per second). The response time is typically reported as the time taken for the reading to reach 95% of the final stable value [29].

Protocol for Evaluating Nanosensor Sensitivity and Selectivity

This protocol is derived from published methodologies for electrochemical and optical nanobiosensors [26] [31].

Dose-Response Calibration:

- Reagents: Prepare a dilution series of the target analyte (e.g., a pesticide or urea) in a relevant matrix (e.g., purified water or soil extract).

- Procedure: Expose the nanosensor to each concentration of the analyte and record the output signal (e.g., electrical current, fluorescence intensity). Plot the signal against the analyte concentration to generate a calibration curve.

Limit of Detection (LOD) Calculation:

- The LOD is frequently calculated as the analyte concentration that yields a signal three times the standard deviation of the signal from blank (analyte-free) samples.

Selectivity Testing:

- Reagents: Prepare solutions of potential interfering substances that are chemically similar or commonly found in the same environment as the target analyte.

- Procedure: Expose the nanosensor to solutions containing these interferents at concentrations typical of the application environment. A highly selective sensor will show minimal signal change in the presence of these interferents compared to its response to the target analyte.

Workflow Visualization: Sensor Benchmarking Methodology

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a comprehensive sensor benchmarking study, integrating the protocols described above.

Diagram 1: Sensor Benchmarking Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The development and testing of advanced soil sensors require a suite of specialized materials and reagents. The following table details essential items for researchers in this field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (Au NPs) | Transducer element in nanobiosensors; can be functionalized with antibodies or DNA for specific detection [26]. | Provide excellent optical and electronic properties; used in colorimetric and electrochemical sensors [26] [31]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Enhance electrochemical reactivity and surface area in electrodes for pesticide and heavy metal detection [26] [31]. | Can be single or multi-walled; often wrapped with single-stranded DNA to improve selectivity [26]. |

| Standard pH Buffer Solutions | Calibrating and verifying the accuracy of conventional and nano-based pH sensors [29] [30]. | Essential for maintaining measurement traceability; typically available at pH 4.01, 7.00, and 10.01. |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Fluorescent labels in optical nanosensors; their size-tunable emission allows for multiplexed detection [26]. | Often used in Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) assays for detecting pathogens or metabolites [26]. |

| Specific Bioreceptors | Provide molecular recognition for high specificity in nanobiosensors. | Includes enzymes, antibodies, or nucleic acids immobilized on the nanomaterial surface to capture the target analyte [26]. |

| Spear Tip pH Probe | Enables direct pH measurement in semi-solid materials like soil and compost with minimal sample preparation [30]. | Features a rugged, sharp tip for penetration; ideal for field research and in-situ profiling. |

This comparison guide delineates a clear performance landscape between conventional and nano-enabled soil sensors. Conventional pH probes, such as the lab-grade and spear-tip models highlighted, offer robust, high-accuracy performance for general soil health monitoring with the advantage of commercial readiness and operational simplicity [29] [30]. In contrast, nanosensors demonstrate a paradigm shift in sensing capability, achieving unparalleled sensitivity and specificity for targeted analytes like pesticides and pathogens, often detecting them at trace levels (parts per billion or lower) [26] [27]. The choice between these technologies is therefore application-dependent. For routine monitoring of primary soil parameters like pH, conventional sensors are highly effective. For research-driven applications requiring the detection of specific, low-concentration biochemicals or early-stage pathogens, nanosensors present a powerful, albeit often more complex, alternative. The future of precision soil management lies in the continued refinement and, potentially, the strategic integration of both these technological paths to achieve comprehensive soil ecosystem understanding.

The escalating challenges of global food security necessitate advanced monitoring solutions to mitigate the risks posed by pathogens and contaminants in the agricultural sector. Traditional detection methods, while reliable, often fall short in providing the rapid, sensitive, and field-deployable analytics required for modern precision agriculture. This guide objectively benchmarks the performance of emerging nanosensors against conventional agricultural sensors, focusing on the critical parameters of sensitivity, speed, and field applicability. The comparison is framed within a broader research initiative aimed at establishing rigorous performance benchmarks for sensing technologies, providing researchers and scientists with validated experimental data and methodologies to guide tool selection and development.

Performance Benchmarking: Nanosensors vs. Conventional Sensors

The transition from conventional sensing to nanotechnology-based platforms represents a paradigm shift in analytical capability. The table below provides a structured comparison of their key performance metrics, highlighting the transformative potential of nanosensors for in-field diagnostics.

Table 1: Performance comparison between conventional sensors and nanosensors for pathogen and contaminant detection.

| Feature | Conventional Sensors (e.g., Chromatography) | Nanosensors |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Parts per million (ppm) to parts per billion (ppb) range [11] | Parts per billion (ppb) to parts per trillion (ppt) range; single-molecule detection possible [11] [27] |

| Analysis Speed | Several hours to days, including sample preparation [11] [27] | Minutes to hours; real-time and continuous monitoring capabilities [11] [33] [27] |

| Selectivity | High, achieved through physical separation | High, achieved through bio-recognition elements (enzymes, aptamers, MIPs) and unique nanomaterial properties [11] |

| Portability & Field Use | Limited; primarily laboratory-bound, requiring skilled personnel [11] [27] | High; designed for portability with user-friendly operation (e.g., test strips, portable electrodes) [11] [27] |

| Key Strengths | High accuracy, standardized protocols, high throughput in lab settings | Superior sensitivity, rapid response, portability for on-site analysis, cost-effectiveness [11] [27] |

| Major Limitations | Time-consuming, costly instrumentation, not suited for real-time field analysis [11] [27] | Potential ecotoxicological risks, complex standardization, relative technological novelty requiring further validation [9] [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Nanosensor Evaluation

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of nanosensor performance data, researchers employ standardized experimental protocols. The following sections detail common methodologies used for quantifying sensitivity and speed, which are critical for benchmarking.

Protocol for Electrochemical Biosensor Detection of Pesticides

This protocol is widely used for detecting organophosphorus pesticides using acetylcholinesterase (AChE)-inhibition based electrochemical sensors [11].

- Primary Reagent: Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme and acetylthiocholine (ATCh) as the substrate.

- Nanomaterial Component: Often integrates with a 3D quantum dot aerogel or other electron-conductive nanomaterials to amplify the signal [11].

- Procedure:

- The sensor platform, functionalized with AChE, is incubated with a sample solution.

- If pesticides are absent, AChE hydrolyzes ATCh to produce thiocholine.

- Thiocholine induces a measurable electrochemical signal change (e.g., current change).

- In the presence of pesticides, AChE is inhibited, reducing thiocholine production and yielding a diminished signal.

- The signal reduction is quantitatively correlated to pesticide concentration using a pre-established calibration curve.

- Data Analysis: The limit of detection (LOD) is calculated, with advanced nanosensors achieving LODs as low as 0.38 pM for specific organophosphorus pesticides [11].

Protocol for Colorimetric Nanozyme-based Detection

This protocol leverages the peroxidase-mimicking activity of nanozymes for visible pesticide detection, suitable for simple field tests [11].

- Primary Reagent: Copper oxide nanoparticles (CuONPs) as a nanozyme, hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and a colorimetric substrate like o-dianisidine or TMB (3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine).

- Procedure:

- AChE hydrolyzes ATCh, producing choline which generates H₂O₂.

- In a functioning system, CuONPs use H₂O₂ to oxidize the substrate, causing a visible color change.

- Pesticides inhibit AChE, reducing H₂O₂ production and subsequent color development.

- The intensity of the color is quantified using a smartphone camera or a portable spectrophotometer.

- Data Analysis: The LOD is determined from the color intensity vs. concentration plot. Reported systems can detect malathion at levels as low as 0.08 mg/L in under 10 minutes [11].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The enhanced performance of nanosensors is governed by distinct signaling mechanisms and workflows. The following diagrams, generated using DOT language, illustrate the core principles of optical and electrochemical nanosensing.

Optical Nanosensing via Fluorescence Quenching

This diagram illustrates the signaling pathway for a fluorescence-based nanosensor detecting pesticides through an enzyme inhibition mechanism.

Diagram Title: Optical nanosensor signaling pathway.

Workflow for a Typical Nanosensor-based Field Assay

This diagram outlines the generalized experimental workflow for conducting a field assay using a nanosensor, from sample preparation to result interpretation.

Diagram Title: Field assay workflow for nanosensors.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

The development and deployment of high-performance nanosensors rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The table below catalogs key components essential for researchers in this field.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for nanosensor development and application.

| Reagent/Material | Function and Role in Detection | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Recognition Elements | Provides high selectivity by binding specifically to the target analyte [11]. | Enzymes (e.g., AChE), antibodies, aptamers (synthetic DNA/RNA), and Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [11]. |

| Nanomaterials | Enhances signal transduction and sensor stability due to unique physico-chemical properties [11] [27]. | Quantum Dots (QDs), carbon nanotubes, graphene, metal nanoparticles (e.g., Au, Ag), and nanozymes (e.g., CuO NPs) [11] [34]. |

| Signal Transducers | Converts the biological/chemical recognition event into a quantifiable signal [11]. | Electrochemical electrodes (e.g., screen-printed), optical fibers, and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) chips [11] [35]. |

| Substrates & Buffers | Provides the optimal chemical environment for the biorecognition reaction to occur. | Specific substrates for enzymes (e.g., ATCh for AChE) and pH-stable buffer solutions are critical for assay reproducibility. |

| Reference Materials | Used for sensor calibration and validation of accuracy. | Certified reference materials (CRMs) of target analytes (e.g., pesticide standards) are essential for quantifying results. |

The escalating challenges of global food security, intensified by population growth and climate change, are driving a transformative shift in agricultural technology. Modern agriculture must transcend traditional, experience-based cultivation models to embrace data-driven approaches that offer real-time, precise insights into plant health [1]. At the forefront of this revolution are two distinct but increasingly convergent technological pathways: spectral imaging and nanosensor integration. Spectral imaging, including hyperspectral and multispectral systems, provides macroscopic, non-invasive health assessment by analyzing light interaction with plant tissues. In parallel, nanosensors offer microscopic, in-situ monitoring of physiological and biochemical processes at the molecular level [36] [37]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these technologies, benchmarking their performance characteristics, applications, and implementation requirements to inform researcher selection and development priorities.

The core distinction lies in their operational scale and sensing philosophy. Hyperspectral imaging captures reflectance across hundreds of contiguous spectral bands (typically 400-1000 nm or 400-2500 nm ranges), generating detailed spectral signatures that serve as fingerprints for biochemical composition [38] [37]. This enables pre-symptomatic disease detection by identifying subtle changes in chlorophyll, water content, and cellular structure before visible symptoms manifest. Conversely, nanosensors employ nanotechnology to detect specific biomarkers—such as hormones, ions, or volatile organic compounds—through direct interaction at the plant interface [36] [33]. These platforms leverage unique physical and chemical properties of nanomaterials like carbon nanotubes, graphene, and quantum dots to achieve exceptional sensitivity and specificity [39].

Technology Performance Benchmarking

Core Performance Metrics Comparison

Table 1: Comprehensive performance comparison between spectral imaging and nanosensor technologies for plant health monitoring.

| Performance Parameter | Hyperspectral Imaging | Multispectral Imaging | Nanosensors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Pixel-level (cm to m) | Patch-level (m) | Molecular to cellular level (nm to μm) |

| Temporal Resolution | Minutes to days | Hours to days | Real-time (seconds to minutes) |

| Sensitivity | High (pre-symptomatic detection) | Moderate (symptomatic detection) | Very High (molecular detection) |

| Specificity | Spectral signature-based | Limited to broad bands | Biomarker-specific |

| Detection Accuracy | 60-98% (depends on model) [40] [37] | 70-90% | Not fully quantified (early stage) |

| Field Deployment | Mature (drones, satellites) | Mature (drones, satellites) | Prototype stage (urban farms) [36] |

| Scalability | Excellent (field to regional) | Excellent (field to regional) | Limited (single plants to small plots) |

| Cost Profile | High initial investment | Moderate | Potentially low (nanomaterial advances) |

Application-Specific Performance Metrics

Table 2: Application-focused performance comparison across key plant health monitoring domains.

| Application Domain | Technology | Key Performance Metrics | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Disease Detection | Hyperspectral Imaging | 98.11% accuracy for mango diseases using SSTAS software [40] | Requires complex data processing |