Nanosensors in Plant Phenotyping: A New Frontier for Non-Destructive, Real-Time Crop Analysis

This article explores the transformative role of nanosensors in advancing plant phenotyping, moving beyond traditional, destructive methods to enable real-time, non-invasive monitoring of plant physiology.

Nanosensors in Plant Phenotyping: A New Frontier for Non-Destructive, Real-Time Crop Analysis

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of nanosensors in advancing plant phenotyping, moving beyond traditional, destructive methods to enable real-time, non-invasive monitoring of plant physiology. Aimed at researchers and scientists, it details the foundational principles of diverse nanosensor platforms—including electrochemical, optical (FRET, NIR-II), and piezoelectric types—and their specific applications in detecting pathogens, phytohormones, and stress signaling molecules like H2O2. The content further addresses critical challenges in sensor stability and scalability, provides validation through case studies and performance comparisons with conventional techniques, and discusses the integration of machine learning for data analysis. The synthesis underscores how this technology provides unprecedented insights into plant health and stress responses, with significant implications for developing climate-resilient crops and optimizing agricultural productivity.

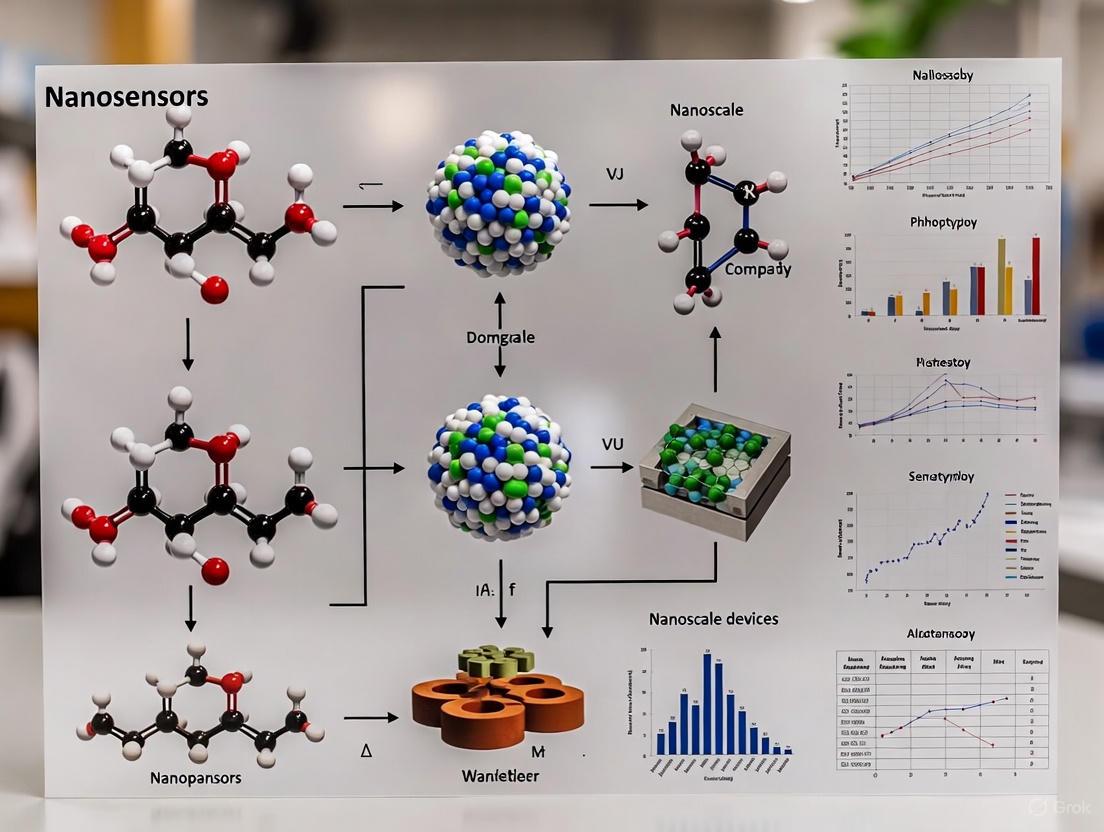

The Foundations of Plant Nanosensing: Principles, Types, and Mechanisms

Nanosensors are defined as selective transducers with a characteristic dimension that is nanometre in scale [1]. These devices measure physical quantities and convert them into signals that can be detected and analyzed, operating at the same scale as many biological processes [2]. In plant science, nanosensors have emerged as transformative tools for non-destructive, minimally invasive, and real-time analysis of biological processes, including plant signalling pathways and metabolism [1]. The integration of nanosensor technology with plant phenotyping—the comprehensive assessment of plant characteristics such as anatomical, ontogenetical, physiological, and biochemical properties—creates a powerful alliance that could support the successful delivery of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals by addressing global challenges in food security and sustainable agriculture [1].

Plant phenotyping has traditionally relied on labor-intensive, costly, and time-consuming methods that often provide only retrospective snapshots of plant status [1] [3]. The quantitative elucidation of plant properties is crucial for understanding the genotype-to-phenotype relationship, enabling data-driven decision-making for optimizing agricultural practices and advancing plant breeding programs [4] [5]. Nanosensors directly address the limitations of conventional phenotyping by enabling continuous monitoring of key plant biomarkers and environmental parameters without harming the plant or disrupting its natural growth processes [1] [6]. This capability is particularly valuable for tracking dynamic physiological responses to environmental stresses such as drought, heat, or pathogen attack, providing researchers with unprecedented insights into plant health and resilience mechanisms.

The global plant phenotyping market, valued at USD 217.19 million in 2024 and projected to reach USD 561.92 million by 2033, reflects the growing importance of these technologies in addressing agricultural challenges [5]. This remarkable expansion, driven by a CAGR of 11.14%, underscores the increasing adoption of advanced phenotyping technologies including nanosensors across both academic research and commercial agriculture [5]. European institutions currently lead this market, followed by North America and Asia-Pacific, with key players including LemnaTec, CropDesign (BASF SE), Heinz Walz, and Photon Systems Instruments driving innovation in the field [5].

Fundamental Principles and Classifications of Nanosensors

Operating Mechanisms and Transduction Principles

Nanosensors operate through various mechanisms that transduce recognition events into measurable signals. The specific transduction method defines the primary classification system for nanosensors, with each type leveraging unique nanomaterial properties to achieve detection [7] [2]. The general workflow involves selective binding of an analyte, signal generation from the interaction between the nanosensor and the bio-element, and processing of the signal into useful metrics [2].

Table 1: Fundamental Types of Nanosensors Used in Plant Science

| Sensor Type | Mechanism of Action | Example Analytes in Plants | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) | Energy transfer between two fluorophores when distance is within nanometer-scale range [1] | ATP, calcium ions, metabolites, transgenes, plant viruses [1] | Ratiometric detection, self-calibration, protein interaction studies |

| Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) | Enhances Raman scattering by molecules adsorbed on nanostructures [1] | Hormones (cytokinins, brassinosteroids), pesticides [1] | Extreme sensitivity (up to single-molecule detection), molecular fingerprinting |

| Electrochemical | Reports electrochemical response or electrical resistance change from reaction with analytes [1] | Hormones, enzymes, metabolites, ROS, ions (H+, K+, Na+) [1] | High sensitivity, portability, potential for field deployment |

| Piezoelectric | Converts mechanical stress into electric signal through reversible process [1] | Morphogenesis [1] | Label-free detection, mechanical property assessment |

| Near-Infrared Fluorescent | Fluorescence intensity changes in response to analyte binding [6] | Hormones (e.g., indole-3-acetic acid) [6] | Minimal interference from plant pigments, deep tissue penetration |

The exceptional performance of nanosensors stems from the unique properties of nanomaterials, including their high surface-to-volume ratio, which dramatically increases the sensing interface, and novel physical properties that emerge at the nanoscale [2]. These characteristics enable enhanced sensitivity and specificity compared to sensors made from traditional bulk materials [2]. Additionally, nanosensors offer significant advantages in cost and response times compared to traditional detection methods such as chromatography and spectroscopy, which may require days to weeks for results and substantial capital investment [2].

Nanosensor Design and Fabrication Approaches

The production of nanosensors follows two primary approaches: top-down and bottom-up methods. Top-down methods begin with a larger pattern that is reduced to nanoscale dimensions through techniques such as lithography, fiber pulling, or chemical etching [2]. Electron beam lithography, though costly, can effectively create nanoscale features on two-dimensional surfaces [2]. Bottom-up methods involve assembling sensors from smaller components, typically atoms or molecules, through self-assembly processes that automatically arrange components into finished structures [2]. This approach holds promise for mass production at lower costs but presents challenges in controlling the distribution, size, and shape of nanoparticles [2].

Key Applications in Plant Phenotyping Research

Hormone Sensing and Signaling Pathway Analysis

Plant hormones serve as crucial chemical messengers that regulate growth, development, and stress responses. Recent advances in nanosensor technology have enabled real-time monitoring of these signaling molecules in living plants. A groundbreaking development from the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART) demonstrates this capability through the creation of the world's first near-infrared fluorescent nanosensor capable of species-agnostic detection of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), the primary bioactive auxin hormone [6]. This sensor uses single-walled carbon nanotubes wrapped in a specially designed polymer that detects IAA through changes in near-infrared fluorescence intensity, successfully mapping IAA responses under various environmental conditions such as shade, low light, and heat stress [6].

Similarly, FRET-based nanosensors have been genetically encoded in plants like Arabidopsis thaliana to study gibberellin hormones, with research by Rizza et al. demonstrating the application of these sensors for understanding hormone-mediated development processes [1]. These sensors typically consist of a cyan fluorescent protein and a yellow fluorescent protein that undergo conformational changes upon hormone binding, altering the energy transfer efficiency between them [1].

Abiotic Stress Monitoring and Chemical Tomography

Nanosensors enable researchers to monitor plant responses to environmental stresses with high spatial and temporal resolution. Innovative work with chromatic covalent organic frameworks (COFs) integrated within silk fibroin microneedles demonstrates how chemical tomography can map chemical gradients within living plants [8]. These COF-silk fibroin interfaces can probe vascular fluid and surrounding tissues of tobacco and tomato plants, detecting the alkalization of vascular fluid as a biomarker for drought stress [8].

Table 2: Nanosensor Applications for Plant Stress Monitoring

| Stress Type | Nanosensor Technology | Biomarker/Parameter Measured | Plant Species Studied |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drought Stress | COF-silk fibroin microneedles [8] | pH changes in xylem [8] | Tobacco, tomato [8] |

| Heat Stress | Near-infrared fluorescent nanosensors [6] | Auxin (IAA) fluctuations [6] | Arabidopsis, Nicotiana benthamiana, choy sum, spinach [6] |

| Light Stress | Genetically encoded FRET sensors [1] | Calcium ions, ATP [1] | Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa [1] |

| Oxidative Stress | Electrochemical nanosensors [1] | Reactive oxygen species (ROS) [1] | Various plant species [1] |

| Pathogen Attack | Antibody nanosensors [1] | Viral and fungal pathogens [1] | Citrus sp., Vitis sp. [1] |

The design of these COF-based sensors exemplifies the precision possible in nanosensor engineering. Researchers developed a series of Schiff base COFs with tunable pKa values ranging from 5.6 to 7.6 by employing different amine and aldehyde monomers, enabling precise targeting of specific pH ranges relevant to plant physiology [8]. The sensors demonstrate acidichromism, transitioning colors from yellow to red or orange to dark red as pH decreases, with the differential energy (ΔE) of TAPP-TFPA COF fluctuating significantly (14-fold) within the pH range of 5.5–8.0 [8].

Pathogen Detection and Plant Immunity Studies

Nanosensors offer innovative approaches for early detection of plant pathogens, enabling timely interventions to protect crops. Research has demonstrated the application of various nanosensor platforms for detecting viral and fungal pathogens [1]. For instance, carbon nanoparticles acting as quenchers combined with antibodies labeled with CdTe quantum dots have been used to detect Citrus tristeza virus, while films of zinc oxide deposited by atomic layer deposition showed effectiveness against Grapevine virus A-type [1]. DNA hybridization with probe-modified nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots and silver nanoparticles has been employed for detecting transgenes and viruses such as the Cauliflower mosaic virus 35s in Glycine max [1].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Methodology for FRET-Based Nanosensor Implementation

The implementation of FRET-based nanosensors follows well-established protocols that can be adapted for various plant species and experimental conditions. The general workflow involves sensor design, plant integration, imaging, and data analysis:

Sensor Design and Selection: Choose appropriate fluorophore pairs with overlapping emission spectra. Genetically encoded FRET sensors typically use fluorescent proteins such as cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) and yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) separated by a recognition element that undergoes conformational change upon analyte binding [1]. The distance between fluorophores must be within the Förster radius (typically <10 nm) for efficient energy transfer [1].

Plant Integration: For genetically encoded sensors, introduce the sensor construct into plants using Agrobacterium-mediated transformation or other gene delivery methods [1]. For exogenous sensors, determine appropriate delivery methods such as infiltration, spraying, or microneedle application based on plant tissue and sensor properties [8].

Calibration and Validation: Perform ex vivo calibration using standard solutions with known analyte concentrations to establish a standard curve relating FRET ratio to analyte concentration [1]. Validate sensor specificity through control experiments with competing analytes or specific inhibitors.

Live-Plant Imaging: Use confocal microscopy or specialized plant imaging systems equipped with appropriate filter sets for donor and acceptor fluorescence detection [1]. Maintain plants under controlled environmental conditions during imaging to minimize external variability.

Ratiometric Analysis: Calculate the FRET ratio as the emission intensity of the acceptor divided by the emission intensity of the donor after background subtraction [1]. This self-referencing approach minimizes artifacts from variations in sensor concentration, excitation intensity, or detection efficiency.

Protocol for Wearable Electrophysiology Sensors

Recent advances in wearable electrophysiology sensors enable non-invasive monitoring of plant electrical signals, which reflect health status and environmental interactions [9]. The implementation protocol includes:

Sensor Fabrication: Develop conformal, adhesive sensors using plant-interfacing materials that can adhere to complex plant surfaces (hairy, rough, superhydrophobic) while inducing minimal impact on plant growth [9]. Material design must address the sensing fidelity challenge on plants.

Sensor Placement: Attach sensors to plant surfaces ensuring good contact while avoiding damage to tissues. The conformal adhesive attachment makes sensors resistant to motion artifacts, enabling reliable measurements in natural environments [9].

Signal Acquisition: Connect sensors to appropriate data acquisition systems capable of recording low-amplitude electrical signals with high temporal resolution. Implement filtering algorithms to remove noise while preserving biologically relevant signal components.

Data Interpretation: Correlate electrical signal patterns with specific environmental stimuli, stress conditions, or developmental events. Machine learning approaches can be employed to classify signal patterns associated with different physiological states.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of nanosensor technology in plant phenotyping research requires specific materials and reagents tailored to both the sensor platform and plant system under investigation. The following table summarizes key components for establishing nanosensor-based plant phenotyping capabilities:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Nanosensor-Based Plant Phenotyping

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanomaterial Platforms | Single-walled carbon nanotubes [6], Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) [8], Quantum dots [1] | Transducer elements for signal generation | Biocompatibility, photostability, functionalization capacity |

| Fluorophores | Cyan/Yellow fluorescent proteins (CFP/YFP) [1], Near-infrared fluorophores [6] | Donor-acceptor pairs for FRET sensors | Spectral overlap, photobleaching resistance, brightness |

| Polymer Matrices | Silk fibroin [8], Specialty polymers for wrapping nanotubes [6] | Biocompatible encapsulation, functionalization | Transparency, stability, analyte permeability |

| Plant Model Systems | Arabidopsis thaliana [1], Nicotiana benthamiana [1], Oryza sativa [1] | Model organisms for sensor validation | Genetic tractability, physiological relevance |

| Imaging Systems | Confocal microscopy, Near-infrared imaging systems [6] | Signal detection and spatial mapping | Resolution, sensitivity, compatibility with fluorophores |

| Signal Processing Tools | Ratiometric analysis algorithms [1], Machine learning classifiers [4] | Data interpretation and quantification | Accuracy, processing speed, biological relevance |

Integration with Advanced Phenotyping Platforms

The full potential of nanosensors in plant phenotyping is realized through integration with complementary technologies such as automated imaging systems, drone-based phenotyping platforms, and artificial intelligence for data analysis [4] [5]. This integration enables multi-dimensional assessment of plant traits across spatial and temporal scales, bridging the gap between laboratory research and field applications.

Deep learning approaches are increasingly being applied to process complex datasets generated by nanosensor deployments [4]. Recent research has demonstrated the effectiveness of hybrid generative models that combine deep learning with domain-specific knowledge to capture complex spatial and temporal phenotypic patterns [4]. These models incorporate biologically-constrained optimization strategies to improve prediction accuracy and interpretability while ensuring biological realism [4]. The integration of environment-aware modules further enhances robustness across diverse agricultural settings [4].

The global trend toward high-throughput phenotyping is further driving nanosensor innovation, with equipment segmented by site (laboratory, greenhouse, field), platform (conveyor-based systems, bench-based systems, handheld/portable systems, drones), and level of automation (manual, semi-automated, fully automated) [5]. Drone-based platforms currently dominate certain market segments due to their efficiency and reduced labor requirements [5].

Future Perspectives and Challenges

Despite significant advances, several challenges remain for widespread adoption of nanosensors in plant phenotyping research. Key limitations include a lack of comprehensive knowledge regarding the health effects of nanomaterials on plants and ecosystems, high costs of some raw materials required for sensor fabrication, and technical challenges related to sensor calibration, drift, and fouling [1] [2]. Additionally, the lower adoption in emerging economies due to funding constraints and technical knowledge gaps presents a barrier to global implementation [5].

Future development trajectories point toward several promising directions:

Multiplexed Sensing Platforms: Combining multiple sensors to simultaneously detect IAA and its related metabolites, creating comprehensive hormone signaling profiles that offer deeper insights into plant stress responses [6].

Enhanced Spatial Resolution: Development of microneedle-based approaches for highly localized, tissue-specific sensing that can map chemical gradients with unprecedented spatial resolution [8] [6].

Field-Deployable Systems: Translation of laboratory prototypes into robust, field-ready solutions through collaborations with industrial farming partners, making precision agriculture tools more accessible [6].

Advanced Material Platforms: Continued innovation in nanomaterial design, including the development of increasingly sophisticated covalent organic frameworks with tailored properties for specific plant sensing applications [8].

As these technologies mature, nanosensors are poised to fundamentally transform plant phenotyping research, enabling unprecedented insights into plant physiology and accelerating the development of more resilient and productive crop varieties to address global food security challenges.

A biosensor is an analytical device that converts a biological response into a quantifiable and processable signal [10]. These devices integrate biological recognition elements with physical transduction mechanisms to detect specific analytes with high specificity and sensitivity. In the context of plant phenotyping research, biosensors have emerged as transformative tools that enable real-time, non-invasive monitoring of physiological processes and stress signaling molecules within living plants [11] [12]. The evolution from conventional biosensors to advanced nanosensors represents a paradigm shift in how researchers can decode complex plant signaling pathways, offering unprecedented temporal and spatial resolution for phenotyping applications.

The fundamental architecture of all biosensors consists of three core components: a bioreceptor that recognizes the target analyte, a transducer that converts the biological interaction into a measurable signal, and signal processors that condition and display the output [10] [13] [14]. This integrated system enables researchers to monitor plant health and stress responses by detecting key signaling molecules such as hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and salicylic acid (SA) directly in living plants, providing valuable insights into stress adaptation mechanisms before visible symptoms appear [12]. The integration of nanotechnology with biosensing has been particularly revolutionary for plant phenotyping, allowing for the development of species-independent sensing platforms that do not require genetic engineering of the plant subjects [11].

Core Components of a Biosensor

Bioreceptors: The Recognition Elements

Bioreceptors are biological or biomimetic elements that provide the specific binding or recognition capability for the target analyte [10] [13]. These molecules interact specifically with the analyte of interest, and this interaction forms the basis for the sensing event. The selectivity of a biosensor is predominantly determined by the bioreceptor's ability to discriminate between the target analyte and other similar substances in the sample matrix [14].

Table 1: Major Bioreceptor Types and Their Applications in Plant Sensing

| Bioreceptor Type | Recognition Principle | Example Applications in Plant Research |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymes [13] | Catalytic activity converting substrate to detectable product | Glucose oxidase in glucose biosensors; Cholesterol oxidase for cholesterol measurement |

| Antibodies [15] [13] | Specific antigen-antibody binding | Immunosensors for pathogen detection in crops; Stress biomarker detection |

| Nucleic Acids [13] | Complementary base pairing (DNA/RNA hybridization) | Genosensors for plant pathogen identification; Aptamer-based sensors for plant hormones |

| Whole Cells [13] | Cellular metabolic responses | Microbial biosensors for herbicide detection in soil; Toxicity screening |

| Artificial Binding Proteins [13] | Engineered protein scaffolds with specific binding | Synthetic receptors for plant hormone sensing; Custom-designed recognition elements |

In plant phenotyping applications, the choice of bioreceptor is critical for achieving the desired specificity. For instance, in the detection of salicylic acid (SA), a key plant stress hormone, researchers have developed single-walled carbon nanotube (SWNT) based nanosensors using cationic fluorene-based co-polymers (S3) as recognition elements through corona phase molecular recognition (CoPhMoRe) [12]. This approach demonstrates how synthetic polymers can serve as effective bioreceptors for plant-specific analytes, enabling real-time monitoring of stress responses in living plants.

Transducers: Signal Conversion Mechanisms

The transducer is the component that converts the biological interaction between the bioreceptor and analyte into a measurable signal [10]. The transducer element works in a physicochemical way—optical, piezoelectric, electrochemical, electrochemiluminescence, etc.—to transform the biological response into an output that can be quantified [13]. The efficiency of this conversion process directly impacts the sensitivity and detection limits of the biosensor.

Table 2: Transducer Types and Their Operating Principles in Plant Phenotyping

| Transducer Type | Operating Principle | Measurable Parameter | Applications in Plant Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical [15] [14] | Measures electrical changes from bio-recognition events | Current (amperometric), potential (potentiometric), or impedance (impedimetric) | Glucose monitoring; Ion flux measurements in plant tissues |

| Optical [15] [14] | Detects changes in light properties | Fluorescence intensity, absorbance, reflectance, SPR angle | NIR-II fluorescence imaging of H₂O₂ [11]; SA detection using SWNT [12] |

| Piezoelectric [15] [14] | Measures mass changes on sensor surface | Resonance frequency shift | Detection of volatile organic compounds from stressed plants |

| Thermal [15] [14] | Measures heat from biochemical reactions | Temperature change | Enzyme thermistors for metabolic activity monitoring |

The transducer selection is particularly important for plant phenotyping applications where non-destructive monitoring is essential. For example, optical transducers operating in the near-infrared-II (NIR-II) region (1000-1700 nm) have proven invaluable for plant sensing because they significantly reduce interference from background signals originating from chlorophyll autofluorescence [11]. This principle was effectively demonstrated in a machine learning-powered activatable NIR-II fluorescent nanosensor for real-time detection of stress-related H₂O₂ signaling in living plants [11]. The NIR-II imaging provided high-contrast and long-term in vivo plant imaging and sensing by increasing the depth of penetration while avoiding the plant's natural autofluorescence.

Signal Processors: Data Interpretation Systems

The signal processing system comprises the electronics and software responsible for converting the transduced signal into a user-interpretable output [10] [16]. This component typically includes signal conditioning circuits (amplifiers, filters), analog-to-digital converters, microprocessors, and display units [17]. For modern plant phenotyping applications, signal processors have evolved to incorporate advanced data analysis algorithms, including machine learning classification systems that can interpret complex biosensor data to identify specific stress types in plants [11].

In sophisticated plant nanosensing platforms, the signal processing system performs critical functions including signal amplification to enhance weak responses from trace analytes, noise filtration to improve signal-to-noise ratio in complex plant matrices, data conversion from analog sensor outputs to digital formats, and statistical analysis to extract meaningful patterns from temporal signaling data [14]. Recent advances have demonstrated the integration of machine learning models with biosensor systems for plant stress classification. For instance, one study showed that a machine learning model trained on fluorescence signals obtained from an NIR-II imaging system could accurately differentiate between four types of plant stress with an accuracy exceeding 96.67% [11].

Biosensor Working Mechanism

The operational principle of a biosensor follows a sequential process that begins with analyte recognition and concludes with a readable output. This process can be visualized as a coordinated workflow between the core components:

Diagram 1: Biosensor Component Workflow

The biological recognition element (bioreceptor) first interacts specifically with the target analyte, forming a stable complex [10]. This interaction produces a physicochemical change that may include alterations in mass, fluorescence, electric charge, refractive index, or heat generation [15]. The transducer then detects this change and converts it into an electrical, optical, or thermal signal that can be measured. Finally, the signal processing system amplifies, conditions, and transforms this signal into a user-interpretable format displayed on a readout device [16] [17].

In plant nanosensing applications, this mechanism enables remarkable capabilities. For example, in the detection of H₂O₂ signaling molecules in living plants, the bioreceptor (e.g., single-stranded (GT)₁₅ DNA oligomer wrapped around SWNT) specifically binds to H₂O₂, causing a change in the NIR fluorescence intensity [12]. This optical signal is transduced and processed to provide real-time information about plant stress levels long before visible symptoms appear.

Nanosensors in Plant Phenotyping Research

Revolutionizing Plant Stress Monitoring

Nanotechnology has dramatically advanced plant phenotyping capabilities by enabling the development of sophisticated nanosensors that can detect subtle biochemical changes in living plants with high spatiotemporal resolution [11] [12]. These nanosensors offer significant advantages over conventional methods, including species-independent operation without requiring genetic engineering, minimal invasiveness that preserves normal plant function, and the capacity for continuous real-time monitoring of stress signaling dynamics [11].

The application of nanosensors in plant phenotyping has revealed novel insights into plant stress signaling pathways. For instance, multiplexed nanosensors for simultaneous monitoring of H₂O₂ and salicylic acid (SA) have demonstrated that different stress types (light, heat, pathogen, mechanical wounding) generate distinct temporal patterns of these signaling molecules within hours of stress treatment [12]. This discovery provides a scientific foundation for pre-symptomatic stress diagnosis in crops, potentially enabling timely interventions to preserve yield in agricultural systems facing climate change challenges.

Experimental Protocol: Multiplexed Nanosensor Imaging of Plant Stress Signals

Objective: To simultaneously monitor H₂O₂ and SA dynamics in living plants subjected to different stress conditions using multiplexed nanosensors [12].

Materials and Reagents:

- Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs)

- (GT)₁₅ DNA oligomer for H₂O₂ sensor formation

- Cationic fluorene-based co-polymers (S3) for SA sensor formation

- Brassica rapa subsp. Chinensis (Pak choi) plants

- Pathogen: Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000

- NIR-II microscopy imaging system

Methodology:

- Nanosensor Preparation:

- For H₂O₂ sensors: Suspend SWNTs in (GT)₁₅ DNA solution (1 mg/mL in deionized water) and sonicate using a tip sonicator (5 W, 30 min) to form stable suspensions [12].

- For SA sensors: Suspend SWNTs in S3 polymer solution (2 mg/mL in deionized water) and sonicate similarly [12].

- Centrifuge suspensions (100,000 × g, 30 min) to remove large aggregates and collect the supernatant containing well-dispersed nanosensors.

Plant Infiltration:

- Infiltrate the abaxial side of plant leaves with nanosensor solutions using a needleless syringe (1 mL).

- For multiplexed detection, infiltrate both H₂O₂ and SA nanosensors in the same leaf area.

- Allow plants to recover under normal growth conditions for 24 hours before stress application.

Stress Application:

- Light Stress: Expose plants to high light intensity (1000 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹) for 2 hours.

- Heat Stress: Subject plants to 38°C for 2 hours in a growth chamber.

- Pathogen Stress: Infiltrate leaves with P. syringae suspension (10⁸ CFU/mL in 10 mM MgCl₂).

- Mechanical Wounding: Create uniform wounds on leaf surfaces using a sterile needle.

NIR-II Fluorescence Imaging:

- Image nanosensor fluorescence using an NIR-II microscopy system with 785 nm laser excitation.

- Collect fluorescence signals in the 1000-1300 nm range using an InGaAs detector.

- Acquire time-lapse images every 5-10 minutes for 4-6 hours post-stress application.

- Process fluorescence intensity data by normalizing to pre-stress baseline values.

Data Analysis:

- Generate temporal profiles of H₂O₂ and SA fluctuations for each stress type.

- Apply machine learning algorithms (e.g., random forest classifier) to differentiate stress types based on signaling dynamics.

- Construct biochemical kinetic models to elucidate stress signaling pathways.

This protocol enables non-destructive, real-time monitoring of early stress signaling events in living plants, providing valuable insights for developing climate-resilient crops and precision agriculture technologies.

Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Nanosensing

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Advanced Plant Phenotyping Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Plant Nanosensing | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs) [12] | Fluorescent sensing platform with photostable NIR emission | Base material for H₂O₂ and SA nanosensors; enables deep tissue penetration |

| DNA oligonucleotides (e.g., (GT)₁₅) [12] | Corona phase formation for specific analyte recognition | H₂O₂ recognition element in CoPhMoRe nanosensors |

| Cationic fluorene-based co-polymers (S3) [12] | Synthetic wrapper for electrostatic analyte interactions | Salicylic acid recognition element in plant hormone sensing |

| Aggregation-induced emission (AIE) fluorophores [11] | NIR-II fluorescence reporters with enhanced stability | AIE1035 nanoparticles for H₂O₂-activated "turn-on" sensing |

| Polymetallic oxomolybdates (POMs) [11] | Fluorescence quenchers with H₂O₂-responsive properties | Mo/Cu-POM as oxidizable quencher in activatable nanosensors |

| Near-infrared-II (NIR-II) imaging system [11] | Detection platform with reduced plant autofluorescence | Macroscopic whole-plant imaging of stress signaling dynamics |

The integration of advanced biosensing technologies with plant phenotyping research has created powerful tools for deciphering complex plant stress signaling networks. The core components of biosensors—bioreceptors, transducers, and signal processors—have evolved significantly with nanotechnology, enabling unprecedented capabilities for real-time, non-destructive monitoring of plant physiological status. The multiplexed nanosensor approach, combining H₂O₂ and SA detection with machine learning classification, represents a transformative strategy for early stress diagnosis and intervention in crops. As these technologies continue to advance, they hold tremendous promise for enhancing our understanding of plant stress biology and developing resilient crop varieties needed to address global food security challenges in a changing climate.

Modern plant phenotyping requires technologies capable of non-destructive, real-time monitoring of physiological processes to advance crop breeding and management. Nanosensors—miniaturized sensing devices with at least one nanoscale dimension—have emerged as powerful tools that provide exquisite sensitivity for detecting signaling molecules, metabolites, and pathogens within living plants [1]. By enabling the precise, in-situ measurement of plant health and stress responses, these devices are transforming our fundamental understanding of plant biology and creating new paradigms for agricultural innovation [18] [19]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of four principal nanosensor types—electrochemical, optical, piezoelectric, and thermal—detailing their operating principles, applications in plant science, and implementation methodologies.

Nanosensor Typology: Principles and Plant Science Applications

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and specific applications of the four nanosensor types within plant phenotyping research.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Nanosensor Types in Plant Phenotyping Research

| Sensor Type | Operating Principle | Key Advantages | Representative Plant Science Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Measures electrical signals (current, potential, impedance) from redox reactions of target analytes [20]. | High sensitivity, portability, low cost, suitability for miniaturization and real-time monitoring [1] [20]. | Detection of hormones, enzymes, reactive oxygen species (ROS), and ions (H+, K+, Na+) [1]. |

| Optical | Transduces biorecognition events into measurable optical signals (e.g., fluorescence, absorbance, SPR) [21] [20]. | High sensitivity and selectivity, capability for multiplexing and remote sensing [1] [20]. | FRET-based monitoring of ATP, Ca²⁺, glucose, and gibberellin; SERS detection of pesticides and hormones [1]. |

| Piezoelectric | Detects mass changes or mechanical stress via oscillating crystals, converting them to electrical signals [1]. | High sensitivity to mass changes, label-free detection. | Study of plant morphogenesis and biomechanical properties [1]. |

| Thermal | Measures heat changes (enthalpy) generated by biochemical reactions [21]. | Label-free detection, insensitive to optical sample properties. | Monitoring of enzymatic reactions and metabolic activity in plant tissues. |

Experimental Protocols for Nanosensor Deployment

Genetically Encoded FRET-Based Optical Nanosensors

FRET-based nanosensors are powerful for ratiometrically monitoring metabolites and signaling molecules in planta.

- Primary Function: Real-time, non-destructive monitoring of analytes like glucose, ATP, and calcium ions in living plant cells and tissues [1].

- Sensor Design: The sensor is a chimeric protein comprising a ligand-binding domain flanked by two fluorescent proteins (e.g., CFP and YFP) that form a FRET pair. Ligand binding induces a conformational change, altering the distance/orientation between the fluorophores and thus the FRET efficiency [1].

- Expression in Plants:

- Genetic Transformation: The DNA sequence encoding the FRET sensor is cloned into an appropriate plant expression vector and stably transformed into plants via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation or transiently expressed via infiltration.

- Confocal Microscopy: Expressing plant tissues are imaged using a confocal laser scanning microscope. CFP is excited at ~433 nm.

- Ratiometric Measurement: Emission intensities are simultaneously recorded at ~475 nm (CFP channel) and ~525 nm (YFP channel). The FRET ratio is calculated as IYFP/ICFP.

- Calibration: The FRET ratio is correlated with analyte concentration by exposing tissues to a range of known analyte concentrations or using calibration buffers post-imaging [1].

Electrochemical Nanosensor for In-Situ Ion Detection

Electrochemical sensors are ideal for detecting ions and small molecules critical to plant health.

- Primary Function: Detection and quantification of specific ions (e.g., H+, K+, Na+) or metabolites in the apoplast or within plant tissues [1] [20].

- Sensor Fabrication:

- Working Electrode Functionalization: Nanoscale working electrodes (e.g., carbon nanotubes, metal nanowires) are fabricated. The electrode surface is functionalized with ion-selective membranes or specific biorecognition elements (e.g., enzymes, aptamers) to ensure selectivity for the target ion (e.g., H+ for pH) [20].

- Sensor Assembly: The functionalized working electrode is integrated with a reference electrode and a counter electrode into a miniaturized probe.

- Measurement in Planta:

- Sensor Implantation: The miniaturized electrochemical probe is carefully inserted into the plant tissue (e.g., stem, leaf) targeting the region of interest.

- Potentiometric/Amperometric Measurement:

- For ions (Potentiometry), the potential difference between the working and reference electrodes is measured under zero-current conditions. The potential is logarithmically related to the ion activity (concentration) via the Nernst equation [20].

- For metabolites (Amperometry), a constant potential is applied, and the current generated from the oxidation/reduction of the target molecule is measured, which is proportional to its concentration [20].

- Data Acquisition: The electrical signal (potential or current) is recorded in real-time using a potentiostat/data acquisition system [20].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental working principles of the four nanosensor types in a plant cell context.

Figure 1: Working Principles of Core Nanosensor Types for Plant Phenotyping.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of nanosensor technology requires specific functional materials and reagents, as detailed below.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nanosensor Development and Deployment

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Proteins (CFP, YFP) | Genetically encoded fluorophores that form a FRET pair. | Serve as the donor and acceptor in genetically encoded FRET nanosensors for metabolites [1]. |

| Ion-Selective Membranes | Polymer membranes containing ionophores that confer selectivity for specific ions (e.g., H+, K+). | Coating working electrodes in electrochemical potentiometric sensors for in-situ ion detection [20]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Spherical gold nanoparticles with unique optical and electrical properties. | Used as transducing elements in optical (e.g., SERS, colorimetric) and electrochemical biosensors; enhance electron transfer and provide a platform for bioreceptor immobilization [21] [19]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Cylindrical nanostructures of carbon with high electrical conductivity and surface area. | Used as the working electrode material in electrochemical nanosensors to enhance sensitivity and facilitate electron transfer [1] [19]. |

| Specific Bioreceptors | Molecules that bind the target analyte with high specificity (e.g., antibodies, aptamers, enzymes). | Immobilized on the transducer surface (e.g., electrode, nanoparticle) to provide the nanosensor's selectivity for a specific plant hormone, protein, or pathogen [22] [19]. |

Electrochemical, optical, piezoelectric, and thermal nanosensors constitute a powerful technological toolkit poised to revolutionize plant phenotyping research. By enabling the non-destructive, real-time, and highly sensitive quantification of a vast array of plant metabolites, ions, hormones, and pathogens, these devices provide unprecedented insights into plant function. The continued refinement of these technologies, particularly through the development of multiplexed sensing platforms and robust field-deployable devices, will be instrumental in addressing grand challenges in global food security, environmental sustainability, and climate-resilient agriculture.

The pursuit of sustainable agriculture and advanced plant research increasingly relies on precise, non-destructive phenotyping methods. Nanosensors, engineered from key nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes (SWNTs), gold and silver nanoparticles (AuNPs, AgNPs), and quantum dots (QDs), are revolutionizing this field by enabling real-time monitoring of cellular processes, metabolites, and stress markers within living plants. These tools provide unprecedented insights into plant physiology, moving beyond destructive endpoint measurements to dynamic, high-resolution spatial and temporal data. This technical guide details the properties, mechanisms, and experimental applications of these core nanomaterials, providing a framework for their integration into plant phenotyping research.

Material Properties and Plant Phenotyping Applications

The unique physicochemical properties of SWNTs, AuNPs, AgNPs, and QDs make them particularly suited for specific roles in plant nanosensors. The table below summarizes their key characteristics and representative applications in plant science.

Table 1: Key Nanomaterials in Plant Phenotyping: Properties and Applications

| Nanomaterial | Key Properties | Primary Roles in Plant Phenotyping | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanotubes (SWNTs) | Small size (diameter ~1 nm), high surface area, superior mechanical/thermal strength, unique near-infrared photoluminescence, ability to cross plant cell walls [23] [24]. | Plant growth regulation, nanotransporters, biosensors, gene delivery, stress tolerance enhancers [24] [19]. | - Monitoring stress response genes in tomato [23].- Enhancing water and nutrient uptake via aquaporin transduction [24].- Acting as a platform for electrochemical biosensors [19]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR), large surface area, tunable optic properties, high biocompatibility, peroxidase-like activity [25] [26]. | Colorimetric sensing, optical and electrochemical biosensors, pathogen and DNA detection [19] [26]. | - Colorimetric sensor arrays for detecting pesticides and toxins [25] [19].- Detection of DNA from pathogens and specific proteins [26]. |

| Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) | Broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, high reflectivity, excellent thermal/electrical conductivity, ability to generate Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) [27] [19]. | Antimicrobial agents, electrochemical biosensing, therapeutic agent and carrier in one [27] [19]. | - Engineered with phages for targeted antibacterial therapies [28].- Enhancing conductivity in electrochemical nanosensors [19]. |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Semiconducting nature, size-tunable photoluminescence, high quantum efficiency, resistance to photobleaching, narrow emission bands [29] [30]. | Fluorescent probes for bioimaging and biosensing, pathogen tracking, detection of ions and biomolecules [29] [30]. | - Early detection of plant diseases via luminescent sensors [29].- Studying plant-pathogen interactions and tracking viruses [29]. |

Experimental Protocols for Nanomaterial Application in Plant Studies

Protocol: Investigating CNT-Induced Growth and Physiological Responses in Tomato

This protocol is adapted from studies on the effects of carbon nanotubes on tomato plants, which demonstrated that CNTs can cause early growth delays but may lead to acclimation and improved performance later in the life cycle without affecting ultimate fruit yield [23].

1. Materials:

- Tomato Seeds (Solanum lycopersicum L. cv. Ailsa Craig) [23].

- Carbon Nanotubes: Both single-walled (SWNTs) and multi-walled (MWNTs), characterized for functionalization, catalyst percentage, aggregation state, and elemental content [23].

- Growth Medium: Commercial potting soil.

- Characterization Equipment: Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) for CNT size verification [23].

- Analysis Equipment: LC-MS system for phytohormone and amino acid analysis [23].

2. Methodology:

- Step 1: CNT Preparation and Characterization

- Characterize CNTs via SEM to confirm size, aggregation, and structure [23].

- Disperse CNTs in appropriate solvent (e.g., deionized water) using sonication to create a stable suspension.

Step 2: Plant Growth and CNT Exposure

- Sow tomato seeds in pots containing potting soil.

- Experimental Groups: Include a control group (soil only) and treatment groups where CNTs are incorporated into the soil at specific concentrations (e.g., 50–200 μg/mL as used in prior studies [23]).

- Grow plants under controlled glasshouse conditions (e.g., 70-90 days to maturity) [23].

- Apply CNT treatments at the time of sowing or at specific growth stages as required.

Step 3: Phenotypic and Physiological Data Collection

- Early Growth Metrics: Monitor and record seed germination rate and early seedling growth.

- Vegetative Growth: Measure plant height, leaf number, and biomass at regular intervals.

- Reproductive Timing: Record the timing of flowering and fruit set.

- Physiological Analysis: At harvest (e.g., 7 weeks), analyze tissues for:

Step 4: Data Analysis

- Compare phenotypic data (growth, flowering time, yield) between control and CNT-treated groups using statistical analysis (e.g., ANOVA).

- Correlate physiological changes (hormone and amino acid levels) with observed phenotypic effects.

Figure 1: Workflow for investigating CNT-plant interactions, from material preparation to data analysis.

Protocol: Detecting Mustard Gas Analogues Using a Gold Nanoparticle Colorimetric Sensor Array

This protocol outlines the development of a colorimetric sensor array based on AuNPs for detecting specific analytes, a method adaptable for detecting plant volatiles or stress markers [25].

1. Materials:

- Chloroauric Acid (HAuCl₄): Precursor for AuNP synthesis [25].

- Reducing/Capping Agents: Sodium citrate, ascorbic acid [25].

- Buffer Solutions: HCl and NaOH aqueous solutions (e.g., 0.01 mol·L⁻¹) for pH adjustment [25].

- Analytes: Target substances for detection (e.g., mustard gas analogues, plant-specific volatile organic compounds (VOCs)) [25].

- Imaging/Software: Flatbed scanner for image acquisition and software (e.g., Photoshop) for RGB value extraction [25].

2. Methodology:

- Step 1: Synthesis of AuNPs of Varied Sizes

- Synthesize AuNPs of different diameters (e.g., 5 nm, 10 nm, 20 nm, 40 nm) using chemical reduction methods, controlling size by varying the concentration of reducing agents and reaction time [25].

Step 2: Construction of the Sensor Array

- Prepare the sensor array by depositing each of the four different-sized AuNP solutions into 16 wells of a microtiter plate.

- Adjust the pH in each row of the array using HCl or NaOH to create four distinct microenvironments (e.g., pH 4, 6, 8, 10) [25].

Step 3: Exposure to Analytes and Data Acquisition

- Expose the array to the target analyte and incubate to allow interaction. The analyte induces varying degrees of AuNP aggregation, causing visible color changes [25].

- Scan the array using a flatbed scanner to obtain high-resolution images before and after exposure [25].

- Use image analysis software to extract the Red, Green, Blue (RGB) values from each well of the array [25].

Step 4: Data Analysis and Pattern Recognition

- Calculate ΔRGB values (difference in RGB values before and after reaction) for each sensing unit to form a unique "fingerprint" for the analyte [25].

- Subject the data matrix to multivariate analysis:

Signaling Pathways and Mechanistic Insights

The application of nanomaterials in plants often triggers or monitors specific biochemical pathways. Understanding these interactions is crucial for interpreting phenotyping data.

CNT-Induced Oxidative Stress and Phytohormonal Crosstalk

Carbon nanotubes can induce a complex signaling cascade in plants, primarily initiated by oxidative stress, which intersects with major phytohormone pathways. The diagram below illustrates this mechanistic pathway.

Figure 2: CNT-induced signaling cascade, from oxidative stress to phenotypic outcomes.

The mechanism begins with the uptake of CNTs, which can localize within cells and induce cellular oxidative stress through the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [23] [24]. This increase in ROS is often accompanied by a rise in nitric oxide (NO), a key signaling molecule in plants. NO is thought to be produced via a nitric oxide synthase (NOS)-like activity that catalyzes the conversion of L-arginine to L-citrulline [23]. The increase in NO can account for subsequent physiological changes, such as an increase in chlorophyll content [23]. Simultaneously, ROS and NO influence the levels of critical phytohormones, including the stress hormones abscisic acid (ABA), salicylic acid (SA), and jasmonic acid (JA) [23]. These hormones engage in complex crosstalk, activating downstream defense pathways and the shikimic acid pathway, which is responsible for producing secondary plant compounds [23]. The culmination of these signaling events results in phenotypic outcomes, where plants may experience delayed early growth followed by acclimation, without significant impact on the final reproductive yield or fruiting time [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation with nanomaterials in plant phenotyping requires a specific set of reagents and tools. The following table details the essential components of the research toolkit.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Nanomaterial-Based Plant Phenotyping

| Item Category | Specific Examples & Specifications | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Nanomaterial Precursors | Chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄), Silver nitrate (AgNO₃) or Acac-based Ag precursors, Purified SWNTs and MWNTs [25] [28]. | Starting materials for the synthesis and preparation of the various nanomaterials. |

| Surface Modifiers & Ligands | Sodium citrate, Ascorbic acid, Engineered M13 bacteriophages, Phenethylamine (PEA), Fluorophenethyl ammonium bromide (FPEABr) [25] [27] [28]. | Control nanomaterial growth during synthesis, improve stability, and provide functional groups for bioconjugation and targeted delivery. |

| Plant Biologicals | Tomato seeds (Solanum lycopersicum L. cv. Ailsa Craig), Target plant pathogens (e.g., E. coli O157:H7), Specific antibodies or DNA probes [23] [28]. | Model organisms and biological recognition elements for pathogen detection and sensor functionalization. |

| Analytical Standards | Phytohormone standards (ABA, SA, JA), Amino acid standards (Arginine, Citrulline), Purified pathogen antigens or DNA [23]. | Calibration and quantification in analytical techniques like LC-MS to ensure accurate measurement. |

| Cell Culture & Buffers | Luria-Bertani (LB) broth for bacterial culture, Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), HCl and NaOH solutions for pH adjustment [25] [28]. | Provide a controlled environment for microbial work and maintain stable pH for nanomaterial stability and reactivity. |

| Characterization Equipment | UV-Vis Spectrophotometer, Scanning/Transmission Electron Microscope (S/TEM), LC-MS System, Flatbed Scanner [23] [25] [28]. | Characterize nanomaterial size, structure, and optical properties; analyze biochemical samples; and digitize colorimetric results. |

Carbon nanotubes, metallic nanoparticles, and quantum dots provide a versatile toolkit for advancing plant phenotyping from macroscopic observation to the resolution of molecular-scale events. Their distinct properties enable the creation of sensors that can probe plant health, physiology, and stress responses in real-time, non-destructively, and with high specificity. As synthesis methods improve and our understanding of nanomaterial-plant interactions deepens, these tools are poised to become integral to fundamental plant research and the development of precision agriculture, ultimately contributing to global food security. Future work will likely focus on enhancing the specificity and biocompatibility of these sensors, reducing potential toxicity, and integrating them with portable devices and AI for automated phenotyping in field conditions.

Plant phenotyping research stands at the precipice of a technological revolution driven by the integration of nanotechnology. Conventional methods for analyzing plant physiology and health are predominantly destructive, requiring physical sampling that prevents continuous monitoring and introduces analytical delays. This whitepaper examines how nanosensors—selective transducers with characteristic dimensions at the nanometre scale—are overcoming these limitations through non-destructive, real-time, and species-independent monitoring capabilities. By enabling direct measurement of metabolites, hormones, and signaling molecules within living plants without genetic modification or tissue damage, these platforms provide unprecedented insights into plant development, stress responses, and metabolic pathways. The fusion of nanosensor technology with plant sciences represents a paradigm shift in phenotyping methodology, offering researchers powerful new tools to address fundamental questions in plant biology while supporting global food security challenges.

Plant phenotyping encompasses the comprehensive assessment of anatomical, ontogenetical, physiological, and biochemical properties to understand plant growth, development, and response to environmental stimuli [1]. Traditional phenotyping methods rely heavily on destructive sampling techniques such as chromatography, which require laboratory-based extraction and processing of plant samples [31]. These approaches are inherently limited because they provide only single time-point measurements, prevent longitudinal studies in the same specimen, and cannot capture the dynamic spatiotemporal nature of biological processes within living plants.

Nanotechnology has ushered in a new era for plant science research through the development of sophisticated sensing platforms that operate at molecular and cellular scales. Nanosensors have emerged as critical tools for monitoring biological processes such as plant signaling pathways and metabolism in ways that are non-destructive, minimally invasive, and capable of real-time analysis [1]. The exquisite sensitivity and versatility of these nanoscale sensors allow researchers to study cellular functions, metabolic flux, and spatiotemporal dynamics of analytes directly in living plants, plant cells, tissues, and organelles [1].

The "critical advantage" of nanosensor platforms lies in their unique combination of attributes that overcome fundamental limitations of conventional plant phenotyping methods. These platforms enable researchers to maintain experimental specimens intact throughout investigation, obtain data continuously as biological processes unfold, and apply consistent methodologies across diverse plant species without genetic modification. This trifecta of capabilities—non-destructiveness, real-time monitoring, and species independence—represents a transformative advancement for plant science research with profound implications for both basic science and agricultural applications.

Nanosensor Architectures and Mechanisms of Action

Various nanosensor architectures have been developed for plant science applications, each employing distinct mechanisms to detect and report on specific analytes. Understanding these fundamental operating principles is essential for researchers selecting appropriate sensing platforms for particular phenotyping applications.

Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) Nanosensors

FRET-based nanosensors utilize light-sensitive fluorescent molecules and measure energy transfer between them [1]. FRET operates through non-radiative transfer of excited state energy by dipole coupling between fluorophores when their separation is within a nanometre-scale range (typically up to ~10 nm) [1]. Energy transferred from an excited donor to an acceptor molecule reduces the donor's fluorescence emission while increasing the acceptor's fluorescence emission intensities. The efficiency of this energy transfer is exquisitely distance-dependent, making FRET an ideal mechanism for studying molecular interactions, protein conformational changes, and enzyme activity [1].

Table 1: FRET-Based Nanosensors for Plant Phenotyping

| Plant Analyte | Sensor Type | Plant Species | Detection Mechanism | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic acid | GFP-tagged proteins | Nicotiana benthamiana | Genetically encoded | Study of protein interactions |

| Glucose | FLIP (FRET between CFP and YFP) | A. thaliana and Oryza sativa | Genetically encoded | Metabolic flux analysis |

| ATP | Nano-lantern (Renilla luciferase + Venus) | A. thaliana | Genetically encoded | Energy metabolism studies |

| Ca²⁺ ions | Yellow cameleons (CFP/YFP) | Lotus japonicus | Genetically encoded | Signaling pathway analysis |

| Gibberellin | CFP/YFP FRET pair | A. thaliana | Genetically encoded | Hormone signaling |

| Citrus tristeza virus | Carbon nanoparticles + CdTe quantum dots | Citrus sp. | Exogenously applied | Pathogen detection |

| Cauliflower mosaic virus | Nitrogen-doped graphene quantum dots + silver nanoparticles | Glycine max | Exogenously applied | Transgene detection |

FRET-based nanosensors can be implemented as either genetically encoded constructs within the plant itself or added exogenously as externally synthesized compounds [1]. Genetically encoded FRET sensors typically comprise two fluorescent proteins with spectral variations that overlap, forming a FRET pair that enables ratiometric readout of analyte concentrations [1]. This self-referencing capability eliminates ambiguities in detection by calibrating two emission bands against each other, providing more reliable quantitative data for phenotyping studies.

Electrochemical Nanosensors

Electrochemical nanosensors constitute another major platform for plant phenotyping applications. These sensors typically comprise a working electrode, counter electrode, and reference electrode, reporting electrochemical responses or electrical resistance changes resulting from reactions with target analytes [1]. Recent advances in nanomaterials have significantly enhanced the performance of electrochemical biosensors through the incorporation of carbon-based nanomaterials and metallic nanoparticles that exhibit unique electrocatalytic properties, facilitating increased electron transfer of redox-active species [31].

Electrochemical sensing technology offers several advantages for plant phenotyping, including good repeatability and accuracy, high sensitivity, portability due to ease of miniaturization, low cost, and relatively rapid response times [31]. These characteristics make electrochemical platforms particularly suitable for field-deployable plant monitoring systems. Recent innovations have focused on minimizing invasiveness through strategies such as microneedle arrays that can be inserted into plant tissues with minimal damage, enabling in situ monitoring of hormones like abscisic acid (ABA) and salicylic acid (SA) [31].

Near-Infrared Fluorescent Nanosensors

A recent breakthrough in nanosensor technology has been the development of near-infrared fluorescent nanosensors for direct, real-time measurement of plant hormones. Researchers from SMART DiSTAP have created the world's first near-infrared fluorescent nanosensor capable of non-destructive, species-agnostic detection of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA)—the primary bioactive auxin hormone controlling plant development, growth, and stress responses [6].

This innovative sensor comprises single-walled carbon nanotubes wrapped in a specially designed polymer, enabling detection of IAA through changes in near-infrared fluorescence intensity [6]. The near-infrared imaging capability allows the sensor to bypass chlorophyll interference, ensuring highly reliable readings even in densely pigmented tissues [6]. Unlike conventional methods that require harmful plant sampling or genetic modification, this nanosensor platform can be applied universally across different plant types without altering the plant's genome, representing a significant advancement for species-independent phenotyping research.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implementing nanosensor technology in plant phenotyping research requires careful consideration of experimental protocols to ensure valid, reproducible results while maintaining plant viability. Below are detailed methodologies for key nanosensor applications in plant research.

Protocol: Near-Infrared IAA Nanosensor Implementation

Objective: Real-time, non-destructive monitoring of auxin dynamics in living plants.

Materials:

- Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNT)

- Designed copolymer (e.g., phospholipid-polyethylene glycol-polyethyleneimine)

- Near-infrared fluorescence imaging system (e.g., InGaAs array detector)

- Target plant specimens (validated in Arabidopsis, Nicotiana benthamiana, choy sum, spinach)

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) for sensor delivery

Methodology:

- Sensor Preparation: Suspend SWCNT in aqueous solution with designed copolymer at concentration of 0.1-1.0 mg/mL. Sonicate using tip sonicator (30-60% amplitude, 10-30 min) followed by centrifugation (10,000-100,000 × g, 30-60 min) to remove aggregates [6].

- Sensor Infiltration: Infiltrate nanosensor solution into plant tissues (leaves, roots, or cotyledons) using needle-free syringe (for leaves) or immersion (for roots). Apply gentle pressure to ensure uniform distribution without tissue damage [6].

- Imaging Setup: Mount plants in growth chamber with controlled environmental conditions. Set up near-infrared imaging system with appropriate excitation (typically 730-850 nm) and emission (900-1600 nm) filters to detect sensor fluorescence while minimizing chlorophyll autofluorescence [6].

- Data Acquisition: Capture time-series fluorescence images before and after experimental treatments (e.g., shade, low light, heat stress). Maintain consistent imaging parameters (exposure time, gain, magnification) throughout experiment [6].

- Calibration: Perform ex vivo calibration using plant tissues infused with known IAA concentrations to establish quantitative relationship between fluorescence intensity and IAA concentration [6].

- Data Analysis: Process images to quantify spatiotemporal fluorescence patterns. Normalize data to baseline measurements and convert to IAA concentrations using established calibration curve [6].

Protocol: FRET-Based Metabolite Sensing

Objective: Ratiometric monitoring of metabolite dynamics in living plant cells.

Materials:

- Genetically encoded FRET biosensor constructs (e.g., FLIP glucose sensors)

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101

- Plant growth media and transformation supplies

- Confocal or fluorescence microscope with appropriate filter sets

- Image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ with FRET plugin)

Methodology:

- Plant Transformation: Introduce FRET biosensor construct into plant cells via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation or protoplast transfection [1].

- Selection and Validation: Select stable transformants using appropriate antibiotics. Confirm sensor expression and functionality through molecular and imaging techniques [1].

- Microscopy Setup: Configure microscope with dual-emission capabilities for donor and acceptor channels. Use 458 nm excitation for CFP, with emission collection at 475-495 nm (CFP) and 525-550 nm (YFP) [1].

- Image Acquisition: Capture time-series images of sensor-expressing tissues before and after experimental treatments. Maintain minimal laser power to prevent photobleaching [1].

- Ratiometric Analysis: Calculate FRET ratio (YFP/CFP emission) for each time point. Normalize to baseline ratio to account for sensor expression variations [1].

- Quantification: Convert FRET ratios to metabolite concentrations using established calibration curves generated with known analyte concentrations [1].

Protocol: Electrochemical Sensor Integration

Objective: In planta monitoring of hormones and signaling molecules using electrochemical detection.

Materials:

- Carbon-based working electrode (glass carbon electrode or miniaturized graphite rod electrode)

- Reference electrode (Ag/AgCl)

- Counter electrode (platinum wire)

- Potentiostat for electrochemical measurements

- Microneedle array platform (for minimally invasive insertion)

Methodology:

- Electrode Modification: Modify working electrode with selective recognition elements (enzymes, antibodies, or molecularly imprinted polymers) and electrocatalytic nanomaterials (carbon nanotubes, graphene, or metallic nanoparticles) to enhance sensitivity and selectivity [31].

- Sensor Calibration: Calibrate sensor performance in standard solutions containing known concentrations of target analyte before plant measurements [31].

- Plant Integration: For minimally invasive monitoring, integrate electrodes into microneedle arrays or inter-digitated microelectrode (IDME) arrays designed for plant tissue insertion with minimal damage [31].

- In Situ Measurement: Insert sensor into plant tissue (fruits, leaves, or stems). Apply appropriate electrochemical technique (amperometry, chronocoulometry, or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy) to detect target molecules [31].

- Signal Processing: Record and process electrochemical signals (current, potential, or impedance) and correlate with analyte concentrations using established calibration curves [31].

- Validation: Confirm sensor performance through comparison with standard analytical methods (e.g., LC-MS) on parallel samples when feasible [31].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Nanosensor-Based Plant Phenotyping

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Proteins | CFP, YFP, GFP, Venus | FRET donor-acceptor pairs for genetically encoded sensors | Spectral overlap, photostability, pH sensitivity |

| Carbon Nanomaterials | Single-walled carbon nanotubes, graphene, carbon quantum dots | Fluorescent transducers, electrode modifiers | Chirality-dependent optical properties, functionalization requirements |

| Metallic Nanoparticles | Gold nanoparticles, silver nanoparticles, quantum dots | Plasmonic enhancement, electrochemical catalysis, fluorescent labels | Size-tunable optical properties, potential cytotoxicity |

| Polymeric Coatings | Phospholipid-PEG, polyethyleneimine, molecularly imprinted polymers | Solubilization, biocompatibility, analyte recognition | Selectivity, binding affinity, stability in planta |

| Electrochemical Platforms | Glassy carbon electrodes, screen-printed electrodes, microneedle arrays | Transducer for electrochemical detection | Miniaturization potential, fouling resistance, sensitivity |

| Recognition Elements | Antibodies, aptamers, enzymes, synthetic receptors | Molecular recognition for target specificity | Stability, selectivity, regeneration capability |

| Delivery Vehicles | Needle-free syringes, biolistic particles, agroinfiltration solutions | Introduction of nanosensors into plant tissues | Delivery efficiency, tissue damage minimization |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams visualize key nanosensor mechanisms and experimental workflows described in this whitepaper, created using DOT language with the specified color palette.

Nanosensor technology represents a fundamental shift in plant phenotyping methodology, providing researchers with unprecedented capabilities for non-destructive, real-time, and species-independent monitoring of plant physiology. The platforms discussed in this whitepaper—including FRET-based sensors, electrochemical devices, and the groundbreaking near-infrared fluorescent nanosensors—each offer unique advantages for specific research applications while collectively advancing the field beyond destructive sampling methods.

The critical advantage of these technologies lies in their ability to preserve experimental specimens while generating continuous, high-resolution data on dynamic biological processes. This capability is transforming how researchers study plant development, stress responses, and metabolic pathways, enabling experimental designs that were previously impossible. The species-independent nature of many nanosensor platforms further enhances their utility by allowing consistent methodologies across diverse plant systems without genetic modification.

Looking ahead, the field is moving toward multiplexed sensing platforms that can simultaneously monitor multiple analytes to create comprehensive hormonal and metabolic profiles [6]. Additional innovations such as microneedles for highly localized, tissue-specific sensing and integration with wireless data transmission systems will further enhance the spatial resolution and practical implementation of these technologies [6]. As nanosensor platforms continue to evolve and become more accessible, they will undoubtedly play an increasingly central role in both fundamental plant science research and applied agricultural optimization, ultimately contributing to enhanced food security in the face of global climate challenges.

Nanosensors in Action: Methodologies and Cutting-Edge Applications in Phenotyping

The real-time monitoring of biochemical signals within living plants represents a significant advancement in plant phenomics. This technical guide details the implementation of optical nanosensors for the simultaneous, non-destructive tracking of hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and salicylic acid (SA), two critical molecules in early plant stress signaling. By leveraging near-infrared fluorescent single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs), this nanosensor platform enables the decoding of distinct stress-specific signaling waves triggered by biotic and abiotic stimuli. The methodology, data, and reagents outlined herein provide researchers with a powerful toolkit to elucidate plant stress adaptation mechanisms, thereby accelerating the development of climate-resilient crops.

Traditional plant phenotyping often relies on destructive sampling and laboratory-based analyses, which provide single time-point data and miss the dynamic interplay of rapid signaling events [12]. The integration of nanotechnology with plant science has created the field of plant nanobionics, equipping plants with novel functions to report on their internal physiological state [12] [32].

Optical nanosensors, specifically those based on SWNTs, are ideal for in vivo monitoring due to their exceptional photostability and fluorescence in the near-infrared (nIR) range. This nIR emission falls outside the chlorophyll auto-fluorescence spectrum, allowing for clear signal detection within plant tissues [12]. This technical guide focuses on the multiplexed use of H₂O₂ and SA nanosensors, a methodology that reveals the temporal ordering and composition of the earliest stress signaling cascades—a capability beyond the reach of conventional phenotyping tools [12] [32]. By providing a window into these living, biochemical processes, this technology directly addresses the growing need for precision in understanding crop responses to environmental stresses exacerbated by climate change.

Nanosensor Design and Operating Principles

Core Sensor Platform and Mechanism

The foundation of this sensing platform is the unique optical properties of single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWNTs). Their near-infrared (nIR) fluorescence is highly sensitive to changes in the immediate chemical environment. The operating principle is Corona Phase Molecular Recognition (CoPhMoRe), where a polymer "corona" non-covalently wraps around the SWNT, creating a specific binding pocket for target analytes [12]. Upon binding, a change in the SWNT's nIR fluorescence intensity occurs, which serves as the quantitative readout.

- Transducer: Single-walled carbon nanotube (SWNT).

- Signal Modality: Near-infrared (nIR) photoluminescence.

- Recognition Mechanism: Corona Phase Molecular Recognition (CoPhMoRe).

- Readout: Fluorescence quenching (turn-off) upon analyte binding.

Sensor-Specific Functionalization

The selectivity for H₂O₂ and SA is achieved by screening and identifying distinct polymer wrappings that confer specific molecular recognition.

- H₂O₂ Nanosensor: SWNTs are wrapped with a single-stranded DNA oligomer with a guanine-thymine sequence repeat, (GT)₁₅. This specific corona phase confers a selective binding affinity for H₂O₂ molecules [12] [32].

- SA Nanosensor: SWNTs are wrapped with a cationic fluorene-based co-polymer (designated S3 in the foundational study). This polymer was identified through a CoPhMoRe screen of 12 key plant hormones and signaling molecules, and it exhibits a selective ~35% quenching response upon binding to 100 µM SA [12].

The following diagram illustrates the structure and mechanism of these two specific nanosensors.

Quantitative Performance and Stress Response Data

The performance of nanosensors is characterized by their sensitivity and selectivity. The following table summarizes key quantitative data for the H₂O₂ and SA nanosensors.

Table 1: Nanosensor Performance Characteristics

| Parameter | H₂O₂ Nanosensor | SA Nanosensor |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor Platform | (GT)₁₅ DNA-wrapped SWNT | Cationic polymer (S3)-wrapped SWNT |

| Signal Response | Fluorescence quenching | Fluorescence quenching (35% for 100 µM) |

| Selectivity Screen | Against 12 plant hormones [12] | Against 12 plant hormones [12] |

| Key Interferants | Not specified in results | Mild cross-reactivity with JA, ABA, GA, NAA, 2,4-D [12] |

| Cellular Localization | Cytoplasm, chloroplast, apoplast [32] | Cytoplasm, chloroplast, apoplast [32] |

When deployed in living plants (Brassica rapa subsp. Chinensis, Pak choi) subjected to various stresses, the multiplexed sensors captured distinct, stress-specific temporal waves of H₂O₂ and SA.

Table 2: Characteristic Stress Signaling Dynamics in Pak Choi

| Stress Treatment | H₂O₂ Wave Dynamics | SA Wave Dynamics | Pathway Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Stress | Rapid initial peak [32] | Delayed, slower accumulation [32] | Negative feedback loop [32] |

| Heat Stress | Rapid initial peak [32] | Delayed, slower accumulation [32] | Positive feedback loop [32] |

| Pathogen Stress | Rapid initial peak [32] | Delayed, slower accumulation [32] | Data not specified |

| Mechanical Wounding | Rapid initial peak [32] | Delayed, slower accumulation [32] | Data not specified |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Sensor Preparation and Plant Infiltration

This protocol outlines the key steps for preparing nanosensor solutions and introducing them into plant leaves.

Nanosensor Suspension Preparation:

- Disperse pristine SWNTs in aqueous solutions containing the specific polymer wrappings ((GT)₁₅ DNA for H₂O₂ sensor; S3 polymer for SA sensor) via tip sonication.

- Centrifuge the suspensions at high speed (e.g., 16,000 × g) to remove large aggregates and obtain stable, monodisperse solutions of polymer-wrapped SWNTs. The concentration is typically in the range of 50-75 mg/L [12].

Plant Infiltration:

- Using a needleless syringe, gently infiltrate the nanosensor suspension into the abaxial (lower) side of a mature leaf.