Nanosensors for Reactive Oxygen Species Detection in Plants: Advanced Tools for Redox Biology and Stress Signaling

This comprehensive review explores the rapidly evolving field of nanosensors for detecting reactive oxygen species (ROS) in plant systems.

Nanosensors for Reactive Oxygen Species Detection in Plants: Advanced Tools for Redox Biology and Stress Signaling

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the rapidly evolving field of nanosensors for detecting reactive oxygen species (ROS) in plant systems. It covers the fundamental roles of ROS as crucial signaling molecules and indicators of oxidative stress in plant physiology and pathology. The article details the working principles, designs, and applications of various nanosensor technologies, including FRET-based, electrochemical, and optical platforms. It provides a critical analysis of methodological challenges, optimization strategies, and validation techniques essential for researchers and scientists. By synthesizing recent advances and future directions, this resource aims to bridge plant science with broader biomedical applications, offering insights for developing next-generation diagnostic tools and stress monitoring platforms in agricultural and clinical research.

Understanding ROS in Plant Physiology: From Fundamental Biology to Detection Challenges

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) represent a fundamental paradox in plant biology, functioning as essential signaling molecules at controlled levels while acting as destructive agents of oxidative damage when unregulated. These highly reactive molecules, derived from molecular oxygen, include singlet oxygen (¹O₂), superoxide radicals (O₂•–), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and hydroxyl radicals (OH•) [1]. Their dual nature is encapsulated in the concepts of 'oxidative eustress'—where ROS mediate adaptive cellular responses through reversible, site-specific oxidation of proteins—and 'oxidative distress'—where ROS accumulation beyond physiological thresholds causes cellular damage and disease [2]. In plant systems, this balance is particularly crucial, as ROS participate in virtually all aspects of the plant life cycle, from growth and development to stress response networks [1] [3]. The emerging field of nanosensor technology for ROS detection offers unprecedented opportunities to unravel the spatiotemporal dynamics of these fleeting molecular species, potentially revolutionizing our understanding of plant stress resilience and productivity.

ROS Homeostasis: Production, Scavenging, and Cellular Compartments

Sites of ROS Production and Scavenging

ROS homeostasis in plant cells is maintained through a delicate balance between production and scavenging mechanisms across multiple cellular compartments. The primary sites of ROS production include mitochondria, chloroplasts, and peroxisomes, with each organelle contributing distinct ROS species through specific metabolic pathways [1]. Mitochondria generate superoxide primarily at Complexes I and III of the electron transport chain, where approximately 0.2%-2% of electrons leak and react with molecular oxygen to form superoxide [2]. Chloroplasts produce singlet oxygen through photosensitization of ground-state oxygen during photosynthesis, while peroxisomes generate hydrogen peroxide as a byproduct of metabolic oxidases [2].

The cellular ROS scavenging system employs both enzymatic and non-enzymatic components to maintain redox homeostasis. Key enzymatic antioxidants include superoxide dismutase (SOD), which catalyzes the conversion of superoxide to hydrogen peroxide; catalase (CAT), which decomposes hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen; and peroxiredoxins (Prx), a ubiquitous family of cysteine-dependent peroxidases that play a pivotal role in regulating hydrogen peroxide levels [2]. At higher H₂O₂ concentrations, Prxs undergo oxidation to sulfinic acid, leading to temporary inactivation—a crucial feedback mechanism in redox signaling [2].

Table 1: Major ROS Species in Plant Cells

| ROS Species | Primary Production Sites | Key Scavenging Mechanisms | Half-Life | Reactivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide (O₂•⁻) | Mitochondria (Complex I, III), Plasma Membrane | Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) | 1-4 μs | Moderate |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Peroxisomes, Chloroplasts, Cytosol | Catalase, Peroxiredoxins, Glutathione Peroxidase | ~1 ms | Selective |

| Singlet Oxygen (¹O₂) | Chloroplasts (Photosystem II) | Carotenoids, Tocopherols | ~1 μs | High |

| Hydroxyl Radical (•OH) | Mitochondria, Cytosol (Fenton reaction) | No enzymatic scavenging; Antioxidants | ~1 ns | Extreme |

ROS-Related Protein Categories and Functions

ROS-related proteins can be systematically categorized based on their functional roles in production, scavenging, and regulation. According to the ROSBASE1.0 database—a comprehensive resource consolidating ROS protein features—these proteins are classified into four distinct groups [2]. ROS-producing proteins include enzymes such as NADPH oxidases (RBOHs) and mitochondrial enzymes like α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, which generate ROS for signaling and defense purposes. ROS-scavenging proteins encompass antioxidant enzymes like SOD, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase that neutralize ROS to prevent cellular damage. A third category comprises proteins with dual ROS-producing-and-scavenging capabilities, such as α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase and pyruvate dehydrogenase complexes that can both generate and eliminate ROS depending on metabolic conditions. Finally, ROS-indirect involvement proteins include those that regulate ROS signaling without directly producing or scavenging ROS molecules, forming complex interactome networks that maintain cellular redox homeostasis [2].

Figure 1: ROS Homeostasis Network in Plant Cells - This diagram illustrates the balance between ROS production sites and scavenging systems that maintain cellular redox homeostasis, with dysregulation leading to oxidative stress.

ROS Signaling in Plant Physiology and Stress Responses

Signaling Mechanisms and Pathways

ROS function as central signaling molecules in plant growth, development, and stress adaptation through complex regulatory networks. Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) plays a particularly pivotal role in what has been termed the 'Redox Code'—a set of principles analogous to the genetic code that regulates biological operations through reversible electron transfers and redox switches [2]. This code organizes metabolism through redox-sensing mechanisms that link metabolic states to protein structures, interaction networks, and enzymatic activities via kinetically controlled redox switches, particularly involving cysteine post-translational modifications (Cys-PTMs) in the proteome [2].

ROS signaling operates through several key mechanisms, including the oxidation of specific cysteine residues in target proteins, which can alter their activity, stability, or interactions; the activation of calcium channels that propagate secondary signals; and cross-talk with hormone signaling pathways including strigolactones, salicylic acid, brassinosteroids, jasmonic acid, and karrikins [1]. Notably, respiratory burst oxidase homologs (RBOHs) function as key ROS-producing enzymes that generate apoplastic superoxide, which can be converted to H₂O₂ and traverse cellular membranes through aquaporin (AQP) channels to initiate intracellular signaling cascades [3]. Research has demonstrated that aquaporins facilitate hydrogen peroxide entry into guard cells to mediate ABA- and pathogen-triggered stomatal closure, highlighting their crucial role in ROS-mediated stress signaling [3].

Organelle-to-Organelle and Cell-to-Cell Signaling

Recent advances have revealed sophisticated organelle-to-organelle signaling pathways mediated by ROS, particularly under stress conditions. Chloroplast-to-nucleus retrograde signaling represents a well-characterized pathway where photo-oxidative stress in chloroplasts triggers the transfer of H₂O₂ to the nucleus, activating high-light-responsive gene expression [3]. Similarly, mitochondrial ROS signaling coordinates metabolic responses to energy deficits, while peroxisomal ROS contributes to the integration of environmental signals and activation of stress-response networks [3].

During reproduction, localized ROS synthesis controls multiple developmental stages including pollen grain formation, pollen-stigma interactions, pollen tube growth, ovule development, and fertilization [4]. Plants utilize RBOH enzymes and organelle metabolic pathways to generate spatially restricted ROS patterns that guide reproductive processes, while scavenging mechanisms including flavonol antioxidants prevent escalation to damaging levels [4]. Under elevated temperatures, this delicate balance is disrupted, with ROS impairment of reproductive processes highlighting the vulnerability of these signaling mechanisms to environmental stress and the protective role of flavonol antioxidants in maintaining ROS homeostasis [4].

Table 2: ROS-Mediated Signaling Pathways in Plant Stress Responses

| Signaling Pathway | Key ROS Species | Primary Sources | Molecular Components | Physiological Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abscisic Acid (ABA) Signaling | H₂O₂ | RBOHs, Peroxisomes | Aquaporins, CPK8, CAT3 | Stomatal Closure, Drought Tolerance |

| Pathogen Defense | O₂•⁻, H₂O₂ | RBOHD/RBOHF, Cell Wall Peroxidases | MAPK Cascades, Ca²⁺ Flux | Hypersensitive Response, Systemic Acquired Resistance |

| Heat Stress Response | H₂O₂, ¹O₂ | Chloroplasts, Mitochondria | BZR1, FERONIA, GRXS17 | Thermotolerance, Chaperone Activation |

| High Light Acclimation | ¹O₂, H₂O₂ | Chloroplasts (PSI/PSII) | β-Cyclocitral, SAFEGUARD1 | Photoinhibition Protection, Gene Expression |

| Reproductive Development | H₂O₂, O₂•⁻ | RBOHs, Pollen Tube Tip | Flavonols, Prxs, Ca²⁺ Gradients | Pollen Tube Guidance, Ovule Recognition |

Oxidative Damage: Molecular Targets and Physiological Consequences

Molecular Mechanisms of Oxidative Damage

When ROS accumulation surpasses cellular scavenging capacity, oxidative damage occurs through several molecular mechanisms with profound physiological consequences. The hydroxyl radical (•OH) represents the most reactive ROS species, capable of attacking all macromolecules with diffusion-limited kinetics [1]. DNA damage occurs primarily through base modifications (particularly guanine oxidation to 8-oxo-dG), strand breaks, and cross-links that can induce mutations if not properly repaired. Lipid peroxidation initiates chain reactions in cellular membranes, generating reactive aldehydes like malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxynonenal that propagate oxidative damage and disrupt membrane integrity [1]. Protein oxidation results in carbonylation of side chains, disulfide bridge formation, aggregation through cross-linking, and ultimately loss of enzymatic function or regulatory capacity [1].

The physiological manifestations of such damage are extensive, including membrane disintegration through lipid peroxidation, inactivation of critical enzymes, disruption of photosynthetic apparatus, and activation of programmed cell death pathways when damage exceeds repairable thresholds [1] [3]. In agricultural contexts, postharvest quality deterioration in fruits and vegetables is closely linked to uncontrolled ROS accumulation, making detection and management of oxidative stress crucial for reducing food losses [5].

Environmental Stress and ROS Dysregulation

Environmental challenges frequently disrupt ROS homeostasis, leading to oxidative distress that compromises plant growth and productivity. Abiotic stresses including drought, salinity, extreme temperatures, and heavy metals typically enhance ROS production while simultaneously compromising antioxidant systems [3]. Research has demonstrated that global warming and climate change create multifactorial stress combinations that particularly impact crop production through ROS-mediated damage pathways [3]. For instance, heat stress impairs tomato reproductive development through ROS disruption of pollen viability and pollen-stigma interactions, though flavonol antioxidants can mitigate these effects [4].

Biotic stressors similarly manipulate ROS dynamics, with plant pathogens employing effector proteins to suppress ROS bursts during infection. The wheat stripe rust fungus produces effector proteins that target chloroplasts and suppress ROS production to facilitate infection [3]. Similarly, Barley stripe mosaic virus γb protein interacts with glycolate oxidase and inhibits peroxisomal ROS production to weaken plant defenses [3]. These examples illustrate the evolutionary arms race between plant ROS defense mechanisms and pathogen countermeasures, highlighting the central importance of ROS management in plant-pathogen interactions.

Advanced Detection Methods for ROS Monitoring

Conventional and Emerging Detection Technologies

Accurate ROS detection is essential for unraveling their dual roles in plant biology, with methodologies spanning biochemical assays, electrochemical detection, and advanced imaging platforms. Conventional approaches include spectrophotometric methods that measure colorimetric changes in redox-sensitive dyes, chromatographic techniques for detecting ROS-modified biomolecules, and fluorescence assays using synthetic probes like DCFH-DA that emit fluorescence upon oxidation [5]. Electrochemical detection offers real-time monitoring capability with high temporal resolution, though specificity toward particular ROS species remains challenging [5].

Emerging technologies significantly enhance ROS detection capabilities, particularly confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) coupled with genetically encoded biosensors that provide subcellular resolution of ROS dynamics [5]. Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) detects micro-environmental changes around fluorophores, offering improved quantification of ROS levels, while in vivo imaging systems (IVIS) enable non-invasive, real-time monitoring of ROS in intact plants and postharvest produce [5]. Recent innovations also include redox-sensitive GFP variants that permit specific monitoring of compartmental redox states, and genetically encoded H₂O₂ sensors like HyPer that provide ratiometric measurements with high specificity [3] [5].

Figure 2: ROS Detection Technologies - This workflow illustrates conventional and emerging methods for detecting and monitoring ROS in plant systems, highlighting applications in stress response profiling.

Experimental Protocols for ROS Detection

Protocol 1: Fluorescence-Based ROS Detection Using DCFH-DA

- Sample Preparation: Collect plant tissue (100-200 mg) and homogenize in 1 mL of appropriate buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) under dim light conditions.

- Probe Loading: Incubate homogenate with 10 μM DCFH-DA for 30 minutes at 25°C in darkness. Include negative controls with antioxidant treatment (e.g., 1 mM ascorbate).

- Fluorescence Measurement: Transfer samples to quartz cuvettes and measure fluorescence intensity at excitation/emission wavelengths of 485/530 nm using a spectrofluorometer.

- Data Analysis: Calculate ROS levels relative to standard curve generated with known H₂O₂ concentrations. Normalize values to protein content or fresh weight.

- Limitations: DCFH-DA lacks specificity for particular ROS species and may undergo photoxidation, requiring careful control experiments [5].

Protocol 2: Nanosensor-Enhanced ROS Detection Using Quantum Dots

- Sensor Preparation: Synthesize or acquire CdTe quantum dots (QDs) functionalized with specific recognition elements (antibodies, enzymes).

- FRET Configuration: For FRET-based detection, conjugate QDs (donor) with appropriate acceptors (gold nanoparticles, organic dyes) that exhibit ROS-sensitive interaction.

- Sample Incubation: Incubate plant samples (tissue extracts or in vivo) with QD nanosensors for 30-60 minutes to allow ROS interaction.

- Signal Detection: Measure fluorescence emission spectra or lifetime changes using fluorometry or FLIM. For Citrus tristeza virus detection, monitor restoration of QD fluorescence upon virus-mediated displacement of CP-rhodamine acceptors [6].

- Quantification: Generate calibration curves with known ROS concentrations. This approach achieved detection limits of 3.55 × 10⁻⁹ M for Ganoderma boninense DNA sequences [6].

Nanosensors: A New Frontier in ROS Detection

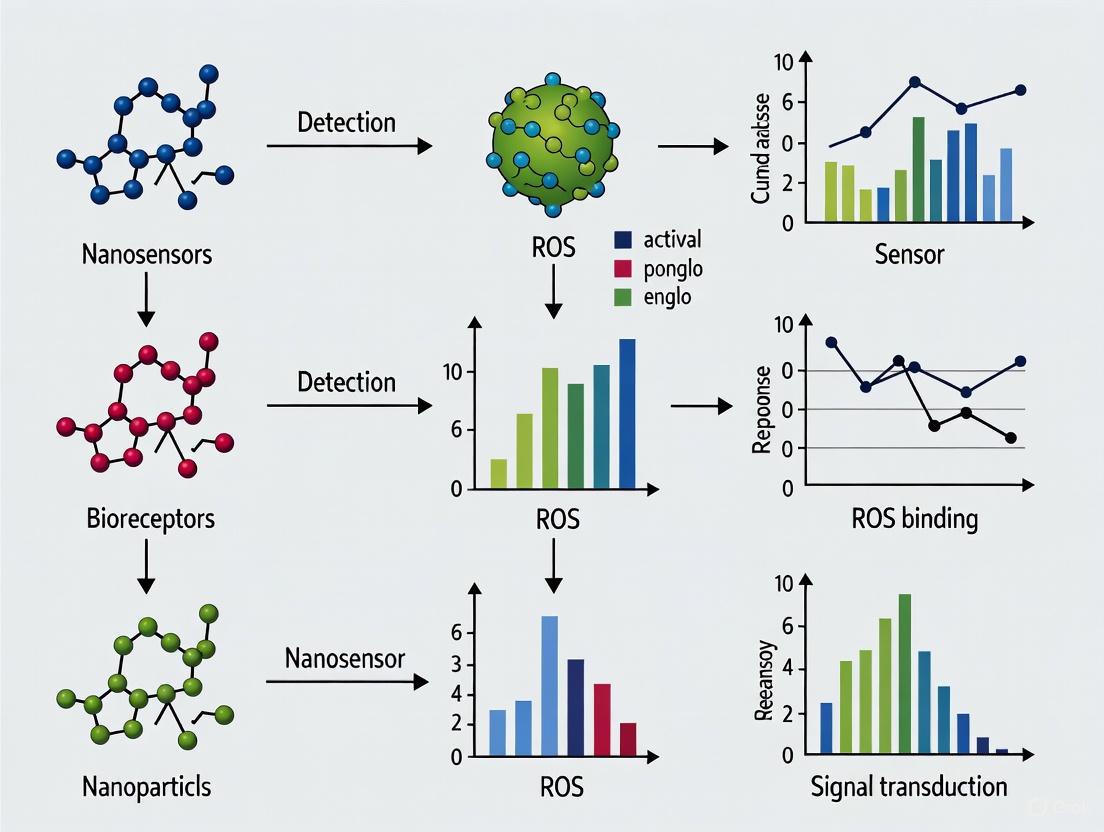

Nanomaterial-Enhanced Biosensing Platforms

Nanotechnology has revolutionized ROS detection through nano-inspired biosensors that offer significant advantages over traditional methods, including enhanced sensitivity, catalytic activity, and faster response times [6]. These nanobiosensors integrate biological recognition elements (enzymes, antibodies, DNA) with nanomaterial transducers (quantum dots, metallic nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes) to create highly specific detection platforms [6] [7]. The fundamental architecture comprises three key components: a biorecognition element that specifically interacts with ROS or ROS-modified biomarkers; a transducer that converts the biochemical interaction into a quantifiable signal; and an amplifier/processor that enhances and processes the output [6].

Several classes of nanomaterials have been particularly impactful in ROS sensing. Quantum dots (QDs), semiconductor nanocrystals with distinctive photophysical properties, enable highly sensitive detection through fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) mechanisms [6]. For instance, cadmium telluride (CdTe) QDs combined with viral coat proteins have successfully detected Citrus tristeza virus through displacement assays that restore QD fluorescence [6]. Gold and silver nanoparticles leverage surface plasmon resonance changes upon ROS interaction, while magnetic nanoparticles facilitate separation and concentration of ROS-modified biomarkers for enhanced detection sensitivity [7]. Carbon-based nanomaterials including graphene oxide and carbon nanotubes offer exceptional electrical conductivity for electrochemical ROS sensing and large surface areas for bioreceptor immobilization [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for ROS Detection

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ROS Detection Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Probes | DCFH-DA, H₂DCFDA, DHE | General ROS detection, Specific for superoxide | Oxidation-dependent fluorescence, Requires careful interpretation |

| Genetically Encoded Biosensors | HyPer, roGFP, GRX1-roGFP | Specific H₂O₂ detection, Redox potential measurement | Ratiometric measurement, Subcellular targeting |

| Nanoparticle Platforms | CdTe Quantum Dots, AuNPs, AgNPs | Signal amplification, FRET-based detection | Enhanced sensitivity, Tunable properties |

| Enzymatic Assay Kits | Amplex Red, L-012 | H₂O₂ quantification, Extracellular ROS detection | High specificity, Commercial availability |

| Antioxidant Reagents | Ascorbic acid, Trolox, NAC | Control experiments, Scavenging reference | Validates ROS specificity, Dose-dependent inhibition |

Implementation and Future Directions

The implementation of nanosensors for ROS detection encompasses various technological formats, including portable handheld analyzers, smartphone-integrated systems, and lab-on-a-chip platforms that enable real-time pathogen and stress monitoring directly in field conditions [6] [7]. Smartphone-integrated nanozyme biosensing represents a particularly promising approach for democratizing ROS detection, allowing non-specialists to conduct sophisticated analyses with minimal equipment [6]. Additionally, wearable plant sensors enable continuous monitoring of ROS dynamics in response to environmental fluctuations, providing unprecedented insights into stress response trajectories [7].

Future developments in ROS nanosensing will likely focus on multiplex detection capabilities that simultaneously monitor multiple ROS species and related signaling molecules; improved specificity through advanced recognition elements like molecularly imprinted polymers; and enhanced field-deployability through integration with wireless networks and AI-based analysis tools [6] [5] [7]. The convergence of nanotechnology with artificial intelligence is particularly promising, enabling predictive modeling of oxidative stress events before visible symptoms appear, potentially revolutionizing plant disease management and crop improvement strategies [7].

The dual nature of ROS as both essential signaling molecules and agents of oxidative damage represents a fundamental aspect of plant biology with profound implications for agricultural productivity and sustainability. Understanding the spatiotemporal dynamics of these versatile molecules is crucial for unraveling their complex roles in plant growth, development, and stress adaptation. The emerging field of nanosensor technology offers unprecedented opportunities to monitor ROS dynamics with the specificity, sensitivity, and spatiotemporal resolution required to advance our understanding of redox biology. By integrating these technological innovations with traditional plant physiological approaches, researchers can develop comprehensive models of ROS signaling networks that bridge molecular mechanisms with whole-plant responses. This integrative approach will ultimately enable the development of novel strategies for enhancing crop resilience to environmental challenges, potentially contributing to global food security in an era of climate change.

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) are unavoidable by-products of aerobic metabolism in plants, playing a dual role as both toxic compounds and crucial signaling molecules [8] [9]. The key ROS species—superoxide anion (O₂•⁻), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and hydroxyl radical (•OH)—exhibit distinct chemical properties and biological activities that define their functions in plant physiology and stress responses [10] [11]. In response to environmental stresses, plants enhance ROS production to initiate robust protective responses, while maintaining sophisticated antioxidative defense systems to manage excessive ROS levels [8]. Recent advancements in nanotechnology have opened new frontiers in ROS research, with nanosensors emerging as powerful tools for non-destructive, real-time monitoring of these dynamic signaling molecules in living plants [12] [13]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive analysis of the core ROS species in plants, framing their significance within the evolving context of nanosensor-enabled plant research.

Chemical Properties of Key ROS Species

The three primary ROS species vary significantly in their chemical reactivity, stability, and cellular mobility, which directly influences their biological functions and detection methodologies [10] [11].

Table 1: Comparative Chemical Properties of Key ROS Species in Plants

| Property | Superoxide Anion (O₂•⁻) | Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Hydroxyl Radical (•OH) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Formula | O₂•⁻ | H₂O₂ | •OH |

| Nature | Free radical | Non-radical | Free radical |

| Half-Life | 1-4 μs [10] | 1 ms [10] | <1 μs [10] [11] |

| Reactivity | Moderate | Low | Extremely high |

| Redox Potential (V) | -0.33 (O₂/O₂•⁻) / +0.93 (O₂•⁻/H₂O₂) [10] | +0.30 [10] | +2.32 [10] |

| Membrane Permeability | Limited | High | Limited |

| Primary Cellular Sources | Chloroplasts (PSI), mitochondria (Complex I & III), NADPH oxidases [8] [9] | Peroxisomes, chloroplasts, cell wall peroxidases [8] [9] | Fenton reaction, Haber-Weiss reaction [10] [11] |

The superoxide anion (O₂•⁻) is the initial product of the univalent reduction of molecular oxygen, serving as a precursor to most other ROS [10] [11]. Despite its "super" name, its reactivity with biomolecules is relatively moderate, though it can undergo dismutation to form hydrogen peroxide either spontaneously or catalyzed by superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzymes [14] [11].

Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) is a non-radical molecule characterized by comparatively low reactivity and high stability, allowing it to function as a mobile signaling molecule that can traverse biological membranes via aquaporins [8] [15]. Its stability and mobility make it an ideal candidate for nanosensor detection and an important secondary messenger in plant signaling networks [12].

The hydroxyl radical (•OH) is the most reactive and consequently most damaging of the primary ROS species [11]. It reacts indiscriminately with virtually all biological macromolecules at diffusion-limited rates, making it a primary mediator of oxidative damage [10] [11]. Its extreme reactivity and consequently short half-life present significant challenges for direct detection in biological systems.

Biological Significance in Plant Physiology

Superoxide Anion (O₂•⁻)

Superoxide serves as a crucial signaling molecule in various plant developmental processes and stress responses. It is generated primarily in photosynthetic and respiratory electron transport chains, as well as by NADPH oxidases (RBOHs) in the plasma membrane [8] [9]. In Arabidopsis, ten genes encoding respiratory burst oxidase homologs (RbohA-RbohJ) have been identified, with their activity regulated by phosphorylation, calcium binding, and other post-translational modifications [8] [9]. Superoxide has been demonstrated to play a key role in breaking seed dormancy and facilitating germination by modifying thiol groups that affect glutathione pools necessary for nitrogen and carbohydrate mobilization [15]. Despite its signaling functions, excessive superoxide accumulation can lead to oxidative damage, particularly to iron-sulfur cluster-containing proteins [8].

Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂)

Hydrogen peroxide functions as a central hub in plant redox signaling networks, integrating information from various environmental and developmental cues [8] [16]. At low concentrations (nanomolar to low micromolar range), H₂O₂ regulates numerous physiological processes including stomatal movement, photosynthesis, photorespiration, growth, development, and programmed cell death [9] [15]. It serves as a key signaling molecule in systemic acquired resistance (SAR) and other defense responses against pathogens [8] [15]. The dual nature of H₂O₂ is evident in its concentration-dependent effects: while essential for signaling at low levels, it becomes toxic at higher concentrations, triggering oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [8] [15].

Hydroxyl Radical (•OH)

The hydroxyl radical is primarily associated with oxidative damage in plant systems due to its extreme reactivity [10] [11]. It is generated through Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions involving hydrogen peroxide and transition metals such as iron or copper [10] [11]. The hydroxyl radical can oxidize cell wall polysaccharides, resulting in cell wall loosening, and cause DNA single-strand breaks [8]. Despite its predominantly destructive nature, there is emerging evidence that •OH may participate in signaling cascades related to programmed cell death and other physiological processes, though its role in signaling is less defined compared to O₂•⁻ and H₂O₂ [8].

ROS Signaling Pathways and Interactions

The signaling functions of ROS are mediated through complex networks involving interactions with other signaling pathways, including calcium ions (Ca²⁺), MAPK cascades, nitric oxide (NO), and various phytohormones [8] [16]. ROS-induced oxidative post-translational modifications (Oxi-PTMs) represent a primary mechanism for ROS signal transduction, with cysteine and methionine residues serving as the most sensitive targets due to their electron-rich sulfur atoms [16]. These modifications act as molecular switches that precisely regulate protein function by altering structure, charge distribution, stability, and interaction capabilities [16].

Diagram 1: ROS-mediated signaling pathways in plants. Abiotic and biotic stimuli trigger ROS production, which activates calcium signaling, MAPK cascades, and protein post-translational modifications, ultimately leading to changes in gene expression and physiological responses. [8] [16]

Nanosensor Applications in ROS Detection

Advanced Detection Methodologies

Recent technological innovations have revolutionized ROS detection in plants, with nanosensors offering unprecedented sensitivity and spatiotemporal resolution [12] [13]. The development of a machine learning-powered activatable NIR-II fluorescent nanosensor represents a significant breakthrough for in vivo monitoring of plant stress responses [12]. This sensor effectively avoids interference from plant autofluorescence and specifically responds to trace amounts of endogenous H₂O₂, providing reliable real-time stress reporting with a sensitivity of 0.43 μM and response time of approximately 1 minute [12].

The nanosensor comprises an aggregation-induced emission (AIE) fluorophore as the signal reporter co-assembled with polymetallic oxomolybdates (POMs) as fluorescence quenchers [12]. In the absence of H₂O₂, the POMs quench the NIR-II fluorescence of AIE nanoparticles. Upon interaction with H₂O₂, the NIR absorbance of POMs decreases dramatically, leading to recovery of the bright NIR-II signal [12]. This "turn-on" design provides visual representation of plant stress information while effectively suppressing non-target background signals [12].

Experimental Protocol for Nanosensor-Based ROS Detection

Materials:

- AIE1035 nanoparticles (NIR-II fluorophore)

- Mo/Cu-POM (polymetallic oxomolybdates)

- Plant specimens (Arabidopsis, lettuce, spinach, pepper, or tobacco)

- NIR-II microscopy system or macroscopic whole-plant imaging system

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4)

Procedure:

- Nanosensor Preparation: Co-assemble AIE1035 nanoparticles with Mo/Cu-POM at optimal mass ratio (determined empirically between 0-100) to create the hybrid nanosensor [12].

- Plant Treatment: Introduce nanosensors into plant tissues through infiltration or other appropriate delivery methods.

- Stress Application: Apply specific stress conditions (abiotic or biotic) to trigger ROS production.

- Imaging: Utilize NIR-II microscopy for cellular-level imaging or macroscopic whole-plant imaging system for larger scale observations.

- Data Acquisition: Monitor fluorescence signal activation at 1000-1700 nm wavelength range.

- Machine Learning Analysis: Process fluorescence data using trained machine learning models to classify stress types with demonstrated accuracy exceeding 96.67% [12].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for nanosensor-based ROS detection in plants. The process involves nanosensor synthesis, plant introduction, stress application, H₂O₂ production, fluorescence activation, NIR-II imaging, data analysis, and stress classification. [12]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ROS Detection in Plants

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| AIE1035 Nanoparticles | NIR-II fluorescence reporter in nanosensors | D-A-D molecular structure with BBTD acceptor and TPA donor units; emission in 1000-1700 nm range [12] |

| Polymetallic Oxomolybdates (POMs) | Fluorescence quencher in nanosensors | Mo/Cu-POM variant with oxygen vacancies for H₂O₂-responsive properties; absorption peak at ~750 nm [12] |

| N-acetyl cysteine | Radical scavenging compound | Reduces homologous recombination frequencies induced by oxidative stress-causing agents [8] |

| Rose Bengal, Paraquat, Amino-triazole | Oxidative stress-inducing agents | Experimental compounds for inducing ROS production and studying oxidative stress responses [8] |

| Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) | Antioxidant enzyme | Catalyzes dismutation of O₂•⁻ to H₂O₂; multiple isoforms (Mn-SOD, Fe-SOD, Cu/Zn-SOD) [8] [14] |

| Catalase (CAT) | Antioxidant enzyme | Decomposes H₂O₂ to H₂O and O₂; abundant in plant peroxisomes [8] [9] |

The distinct chemical properties of superoxide anion, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radical define their unique biological roles in plants, ranging from destructive oxidants to sophisticated signaling molecules. Understanding these properties is fundamental to advancing plant stress biology, crop improvement strategies, and ecosystem management. The emergence of advanced nanosensor technologies, particularly NIR-II fluorescent sensors combined with machine learning analytics, represents a transformative approach for real-time, non-destructive monitoring of ROS dynamics in living plants. These technological innovations promise to unlock new dimensions of understanding in plant redox biology, enabling researchers to decipher the complex language of ROS signaling with unprecedented precision and temporal resolution. As these tools continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly reveal new insights into the intricate balance between ROS production and scavenging that governs plant life, from cellular processes to ecosystem dynamics.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are fundamental to plant life, acting as damaging agents during oxidative stress and as crucial signaling molecules in growth, development, and stress acclimation [17] [18]. The precise spatiotemporal dynamics of ROS generation are critical for their functional duality, making the identification and understanding of their primary production sites a central focus in plant biology. Within the context of developing advanced nanosensors for ROS detection, this delineation becomes even more critical, as it informs sensor design, targeting, and data interpretation. This technical guide details the core cellular systems responsible for ROS generation in plants: mitochondria, chloroplasts, and the plasma membrane-associated NADPH oxidases. A comprehensive grasp of these sources is indispensable for leveraging nanosensor technology to unravel complex redox signaling networks and for progressing diagnostic applications in plant and life sciences research.

Major ROS Generation Sites in Plants

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the primary ROS generation sites in plant cells.

Table 1: Primary Sites of ROS Generation in Plant Cells

| Generation Site | Primary ROS Produced | Key Enzymes/Components | Major Triggers/Contexts | Topology/Subcellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chloroplast | Singlet Oxygen (¹O₂), Superoxide (O₂•⁻), Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Photosystem II (PSII), Photosystem I (PSI), Plastoquinone (PQ) pool, Chlorophyll biosynthesis intermediates [17] | Excess light energy, CO₂ limitation, drought, high/low temperature [17] [19] | Thylakoid membrane, reaction centers of PSI and PSII [17] |

| Mitochondria | Superoxide (O₂•⁻), Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Electron Transport Chain (ETC) Complexes I, II, and III [20] | Restricted ADP availability, inhibition of electron transport, reverse electron flow [20] | Mitochondrial matrix (via Complex I), intermembrane space (via Complex III) [20] |

| NADPH Oxidases (RBOHs) | Superoxide (O₂•⁻) | RBOHD, RBOHF (Respiratory Burst Oxidase Homologs) [21] [22] | Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), damage signals, hormone signaling, ER stress [19] [22] | Plasma membrane [21] |

Chloroplasts as Major ROS Production Hubs

Chloroplasts are a significant source of ROS, particularly under high-light conditions. The photosynthetic electron transport chain (PETC) is a major site for ROS generation, with the plastoquinone (PQ) pool acting as a central redox regulator [19].

- Singlet Oxygen (¹O₂) Production: The primary source of ¹O₂ is in the reaction center of Photosystem II (PSII). Under excess light, the primary electron acceptor QA becomes over-reduced, favoring the formation of the triplet state of chlorophyll P680 (³P680). This triplet chlorophyll can then transfer energy to ground-state triplet oxygen (³O₂), generating highly reactive ¹O₂ [17]. Chlorophyll biosynthesis intermediates, such as protochlorophyllide, can also produce ¹O₂ upon illumination [17].

- Superoxide and Hydrogen Peroxide Production: At Photosystem I (PSI), the reduced ferredoxin can transfer electrons to O₂, a process known as the Mehler reaction, leading to O₂•⁻ formation. This O₂•⁻ is then rapidly converted to H₂O₂ by superoxide dismutase (SOD) [17]. Furthermore, photorespiration, which is enhanced under conditions limiting CO₂ fixation, involves the glycolate oxidase reaction in peroxisomes and is a significant source of H₂O₂ [17].

The following diagram illustrates the key ROS generation pathways within the chloroplast.

Figure 1: Key ROS Generation Pathways in the Chloroplast. (PSII: Photosystem II; PSI: Photosystem I; PQ: Plastoquinone; QA: Primary quinone electron acceptor; ¹O₂: Singlet Oxygen; O₂•⁻: Superoxide; H₂O₂: Hydrogen Peroxide; SOD: Superoxide Dismutase).

Mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) Generation

Plant mitochondria contribute to cellular ROS production primarily through electron leakage from the mitochondrial electron transport chain (mtETC).

- Superoxide Production Sites: The primary sites for O₂•⁻ generation are Complex I (on the matrix side) and Complex III (on both the intermembrane and matrix sides) [20]. The rate of production is strongly increased when the respiratory rate is slowed, for instance by restricted ADP availability or inhibition of the electron transport chain, leading to a highly reduced state of mtETC components [20].

- Regulation and Signaling: Mitochondria possess several mechanisms to minimize ROS production, including alternative oxidase (AOX), which bypasses proton-pumping complexes III and IV, and uncoupling proteins (UCPs) that promote proton leak across the membrane [17] [20]. The H₂O₂ released from the matrix can function as a retrograde signal, potentially exiting mitochondria via aquaporins to influence nuclear gene expression [20]. Furthermore, specific protein thiols within the mitochondria, such as those on alternative oxidase and TCA-cycle enzymes, may be oxidized by H₂O₂, suggesting the existence of intramitochondrial ROS-dependent thiol redox signaling to adjust metabolic functions [20].

NADPH Oxidases (RBOHs) as Deliberate ROS Producers

The plasma membrane-localized NADPH oxidases, known as Respiratory Burst Oxidase Homologs (RBOHs), are enzyme complexes dedicated to deliberate, signaling-related ROS production.

- Function and Mechanism: RBOHs, such as RBOHD and RBOHF, generate O₂•⁻ in the apoplast by transferring electrons from cytoplasmic NADPH to extracellular oxygen [21] [22]. This O₂•⁻ can spontaneously or enzymatically dismutate to the more stable H₂O₂, which can then diffuse back into the cell via aquaporins [22].

- Role in Signaling and Stress: RBOHs are crucial for systemic signaling and plant immunity. They are key players in the "oxidative burst" during pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) [19]. Recent research also demonstrates a cytoprotective role for RBOH-generated ROS during endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, where they are necessary for the proper activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) and plant survival [22]. This highlights a sophisticated role for these enzymes beyond pathogen defense.

Isolating Mitochondrial ROS (mtROS) Production

Objective: To measure the rate and capacity of superoxide/H₂O₂ production in isolated plant mitochondria.

Principle: Isolated mitochondria are incubated with specific substrates and inhibitors to drive electron flow through specific segments of the ETC, and ROS production is quantified using fluorescent or colorimetric probes.

Detailed Protocol:

- Mitochondrial Isolation: Homogenize plant tissue (e.g., potato tubers, Arabidopsis cell cultures) in an ice-cold isolation buffer (e.g., containing mannitol, sucrose, EDTA, BSA, PVPP, and HEPES, pH 7.2). Differential centrifugation is used to pellet and wash mitochondria, with a final purification on a Percoll density gradient [20].

- Reagent Preparation:

- Reaction Buffer: 0.3 M Sucrose, 5 mM KH₂PO₄, 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl₂, 10 mM MOPS-KOH, pH 7.2.

- Substrates/Inhibitors:

- Complex I-specific substrate: 10 mM Malate + 10 mM Glutamate.

- Complex II-specific substrate: 10 mM Succinate (use with Complex I inhibitor rotenone).

- Inhibitors: 100 µM Antimycin A (inhibits Complex III), 1 mM KCN (inhibits cytochrome c oxidase).

- Detection Probe: 50 µM Amplex Red (for H₂O₂) + 1 U/mL Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP). Alternative: 100 µM NBT for superoxide (forms formazan precipitate).

- Procedure:

- Add 100 µg of mitochondrial protein to 1 mL of reaction buffer in a spectrophotometer cuvette or microplate well.

- Add the chosen substrate/inhibitor combination and pre-incubate for 2 minutes.

- Initiate the reaction by adding the detection probe.

- Monitor fluorescence (Amplex Red: Ex/Em ~560/590 nm) or absorbance (NBT: 530-550 nm) kinetically for 10-30 minutes.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the rate of ROS production (e.g., pmol H₂O₂/min/mg protein) from the linear portion of the curve using a standard curve of H₂O₂. Compare rates under different conditions to identify the primary production sites [20].

Confirming RBOHD/RBOHF-Dependent ROS In Planta

Objective: To visually localize and semi-quantify superoxide production in living plant tissues and genetically link it to RBOH activity.

Principle: Nitrotetrazolium Blue (NBT) is a histochemical stain that forms an insoluble blue formazan precipitate upon reduction by superoxide.

Detailed Protocol:

- Plant Material: Use wild-type (e.g., Arabidopsis Col-0) and rbohd rbohf double mutant seedlings.

- Treatment: Grow seedlings for 7 days, then transfer to media containing an ER stress inducer like 5 µg/mL tunicamycin (Tm) or a solution of the bacterial PAMP flg22 (e.g., 1 µM) for 24-48 hours [22].

- Staining Solution: Prepare 0.1% (w/v) NBT in an appropriate buffer (e.g., 10 mM Sodium Azide in 10 mM Potassium Phosphate buffer, pH 7.8). Sodium azide inhibits peroxidases to reduce background.

- Staining Procedure:

- Submerge the treated seedlings in NBT staining solution.

- Incubate in the dark for 30-60 minutes.

- Destain by transferring seedlings to 95% ethanol and incubating in a water bath at 70-80°C for 10-15 minutes to remove chlorophyll.

- Replace with fresh 95% ethanol for storage and visualization.

- Imaging and Analysis: Capture images of the destained seedlings under a stereomicroscope. The intensity and distribution of the dark blue formazan precipitate indicate sites of superoxide accumulation. A significant reduction in staining in the rbohd rbohf mutant compared to the wild-type under stress conditions confirms the contribution of these NADPH oxidases to the observed ROS burst [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and tools essential for experimental research into plant ROS sources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Plant ROS Sources

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Principle | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| Amplex Red | Fluorescent probe; Reacts with H₂O₂ in a 1:1 stoichiometry via HRP to yield resorufin. | Quantifying H₂O₂ production in isolated organelles (e.g., mitochondria) or enzymatic assays [20]. |

| Nitrotetrazolium Blue (NBT) | Colorimetric dye; Reduces to insoluble blue formazan by superoxide. | Histochemical localization of superoxide in intact tissues, roots, or leaves [22] [23]. |

| Tunicamycin (Tm) | Inhibitor of N-linked glycosylation; Induces protein misfolding and ER stress. | Eliciting ER stress and studying associated RBOH-dependent ROS production [22]. |

| rbohd rbohf Mutant | Arabidopsis double knockout mutant lacking key NADPH oxidase genes. | Genetic control for confirming the specific role of RBOHD/RBOHF in ROS production during stress responses [22]. |

| Alternative Oxidase (AOX) Inhibitors (e.g., SHAM) | Inhibits the alternative oxidase pathway in mitochondria. | Studying the role of AOX in mitigating mitochondrial ROS production under stress [17] [20]. |

| NIR-II Fluorescent Nanosensor (AIE1035NPs@Mo/Cu-POM) | "Turn-on" sensor; H₂O₂ oxidizes POM quencher, recovering NIR-II fluorescence from AIE fluorophore. | Non-invasive, real-time in vivo monitoring of H₂O2 signaling across plant species with high spatiotemporal resolution [12]. |

Integration with Nanosensor Research: Future Perspectives

Understanding these primary ROS sources directly informs the design and application of nanosensors. For instance, the development of a machine learning-powered, activatable NIR-II fluorescent nanosensor represents a significant advancement [12]. This sensor leverages the specific reactivity of H₂O₂ with polymetallic oxomolybdates (POMs) to activate a near-infrared fluorescence signal, effectively bypassing the autofluorescence of plant tissues.

- Compartment-Specific Targeting: Future nanosensor iterations can be functionalized with targeting moieties (e.g., specific signal peptides) to localize them to mitochondria, chloroplasts, or the apoplast, allowing for compartment-specific ROS monitoring.

- Decoding Complex Signaling: The ability of such sensors, combined with machine learning, to differentiate between abiotic stress types with over 96.67% accuracy demonstrates the power of precise ROS detection [12]. By correlating spatiotemporal ROS patterns from specific organelles with physiological outputs, researchers can decode the complex language of redox signaling.

- Bridging Technology and Biology: The integration of these sophisticated tools with a solid understanding of fundamental ROS biology, as outlined in this guide, is paramount for advancing our knowledge of plant stress responses and developing innovative solutions for crop improvement and disease diagnostics [12] [7].

The intricate network of ROS generation and signaling in plants, spanning multiple cellular compartments, is summarized in the following pathway diagram.

Figure 2: Integrated ROS Signaling Network in Plant Cells. Environmental stresses trigger ROS production at specific sites. The resulting ROS signals, depending on their type, concentration, and location, activate distinct downstream cellular responses, ranging from acclimation to cell death.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) represent a collective term for a wide range of chemical species derived from molecular oxygen with differing reactivities, lifetimes, and biological targets [24]. The term encompasses not only radical species like the superoxide radical anion (O₂•⁻) and hydroxyl radical (•OH) but also non-radical derivatives such as hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), hypochlorous acid (HOCl), and peroxynitrite (ONOO⁻) [24]. This chemical diversity presents a fundamental challenge for researchers: treating "ROS" as a single discrete molecular entity leads to misleading claims and impedes scientific progress [24] [25]. The limitations of conventional measurement approaches are particularly problematic in plant research, where understanding redox signaling and oxidative stress responses requires precise identification of specific ROS involved in signaling pathways and stress responses.

The inherent complexity of ROS chemistry means that different ROS exhibit dramatically different biological behaviors. For instance, H₂O₂ is relatively stable and functions as an important signaling molecule in vivo due to its poor reactivity with most biomolecules, while •OH reacts non-specifically and essentially instantaneously with any nearby biomolecule [24] [25]. Despite these well-established differences, many researchers continue to employ commercial kits and probes that claim to measure generic "ROS" without distinguishing between these chemically distinct species [24] [25]. This consensus statement illuminates the problems arising from these conventional approaches and provides guidelines for best practice in ROS detection, with special consideration for applications in plant nanosensor research.

The Complex Landscape of Reactive Oxygen Species

Diversity of ROS and Their Biological Roles

The reactivity of different ROS varies over an enormous scale, as do their lifespans, diffusion capabilities, and potential to generate downstream reactive species [24] [25]. Understanding these differences is essential for selecting appropriate detection methods and interpreting results accurately, especially in plant systems where spatial and temporal dynamics of ROS production are critical for signaling and stress responses.

Table 1: Physicochemical Properties of Common Biological ROS

| ROS Species | Chemical Formula | Reactivity & Lifespan | Primary Biological Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superoxide radical anion | O₂•⁻ | Selectively reactive; limited diffusion | Fe-S cluster proteins; reacts with •NO to form peroxynitrite |

| Hydrogen peroxide | H₂O₂ | Unreactive with most biomolecules; relatively long-lived | Specific protein cysteine residues; peroxidase substrates |

| Hydroxyl radical | •OH | Extremely reactive; lifetime ~2 nanoseconds; diffusion radius ~20Å | Attacks all adjacent biomolecules indiscriminately |

| Peroxynitrite | ONOO⁻/ONOOH | Reacts with thiols and metal centers | Thiols, tyrosine residues (forming nitrotyrosine) |

| Hypochlorous acid | HOCl | Strong oxidant | Thiols, methionine residues, amines |

| Singlet oxygen | ¹O₂ | Generated by photosensitization; responsible for photodamage | Selective reaction with deoxyguanosine; lipid peroxidation |

ROS Generation and Signaling in Plant Systems

In plants, ROS function as crucial signaling molecules regulating processes such as growth, development, and stress responses, while also contributing to oxidative damage during severe stress [5]. The primary sites of ROS production in plant cells include chloroplasts, mitochondria, and plasma membrane-associated NADPH oxidases (RBOHs). The specific ROS involved in these processes determines the physiological outcome, making accurate identification essential for understanding plant stress responses and developing effective detection strategies.

Limitations of Conventional ROS Measurement Approaches

Problematics of Commercial Kits and Fluorescent Probes

Many conventional approaches to ROS measurement suffer from significant limitations that compromise their utility in biological research [24] [25]. A primary issue is the lack of specificity of many commercially available probes and kits that claim to measure generic "ROS" without distinguishing between individual species [24]. For example, the fluorescent probe dihydroethidium (DHE), frequently used for superoxide detection, undergoes oxidation to ethidium that intercalates within DNA and produces fluorescent red emission [26]. However, DHE shows significant oxidation in resting cells and responds to multiple oxidizing species, complicating data interpretation [26].

The Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green reagent represents a rare example of a highly selective probe, showing minimal response to hydroxyl radical, superoxide, or nitric oxide [26]. Unfortunately, most conventional probes lack this level of specificity, leading to potential misinterpretation of experimental results. Furthermore, many probes capture only a small percentage of any ROS formed, and this percentage may vary with production rates, making quantitative comparisons problematic [25].

Misuse of Antioxidants and Inhibitors

The use of "antioxidants" as pharmacological tools to implicate ROS in biological processes presents another significant challenge in the field [25]. Many low-molecular-mass compounds commonly employed as "antioxidants" have modest reactivity with specific ROS and often exert effects through other mechanisms. For instance, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), widely used as an "antioxidant," has poor reactivity with H₂O₂ and may instead influence cellular processes by increasing cysteine pools, enhancing glutathione synthesis, generating H₂S, or directly cleaving protein disulfides [25].

Similarly, the use of compounds like apocynin and diphenyleneiodonium as "NADPH oxidase inhibitors" remains widespread despite their well-established lack of specificity [25]. Reliance on such non-specific pharmacological tools without supporting genetic evidence has led to numerous erroneous conclusions in the ROS literature.

Advanced Methodologies for Specific ROS Detection

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) Spectroscopy

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) represents the gold standard for direct detection of radical species, providing unambiguous identification and quantification of specific ROS [27]. Unlike indirect methods that measure oxidative damage "a posteriori," EPR provides direct evidence of the "instantaneous" presence of free radical species [27]. This technique can be applied to various biological samples, including capillary blood, plasma, and erythrocytes, showing strong correlations between different compartments (R² = 0.95 for capillary versus venous blood) [27].

Recent methodological advances have enabled EPR-based quantification of ROS production in human capillary blood, providing a microinvasive approach suitable for routine application in clinical and research settings [27]. Studies utilizing this approach have demonstrated significantly different ROS production rates between young versus old and healthy versus pathological subjects, with these changes correlating directly with established biomarkers of oxidative damage [27].

Table 2: Comparison of ROS Detection Methodologies

| Method | Detection Principle | Specificity | Sensitivity | Applications in Plant Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) | Direct detection of unpaired electrons | High for specific radical species | Excellent | Identification of specific radical species in plant tissues |

| Fluorescent probes (e.g., DHE, H₂DCFDA) | Oxidation to fluorescent products | Variable; often low | High but prone to artifacts | Spatial imaging of ROS in plant cells and tissues |

| Chemiluminescent probes | Light emission upon oxidation | High for specific probes (e.g., Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green) | Moderate to high | Detection of specific ROS in plant extracts |

| Electrochemical biosensors | Electron transfer at electrode surfaces | Can be high with specific biorecognition elements | Excellent | Real-time monitoring of ROS in plant stress responses |

| Spin trapping + EPR | Stabilization of radicals for detection | Depends on trap compound | High | Identification of short-lived radicals in plant systems |

Genetically Encoded ROS Generation Systems

For establishing causal relationships between specific ROS and biological outcomes, genetically encoded systems for controlled ROS production provide superior alternatives to chemical generators [25]. The regulated generation of H₂O₂ within cells can be achieved using genetically expressed D-amino acid oxidase, an enzyme that produces H₂O₂ while oxidizing D-amino acids [25]. This system can be targeted to different cellular compartments, with flux regulated by varying the concentration of its substrate, D-alanine [25].

For superoxide generation, redox-cycling compounds such as paraquat (PQ) or quinones provide more selective approaches, while MitoPQ specifically generates superoxide within mitochondria [25]. These tools enable researchers to investigate the consequences of specific ROS production in defined cellular locations, providing mechanistic insights not possible with non-specific approaches.

Diagram 1: Method Selection Workflow for Specific ROS Detection. This workflow emphasizes the importance of method selection based on experimental objectives and the necessity of multi-method validation.

Nano-Enabled Biosensing Platforms

The emergence of nano-enabled biosensors represents a significant advancement in ROS detection technology, particularly for plant science applications [5] [7]. These platforms integrate nanomaterials such as chitosan nanoparticles, silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), and graphene oxide with biological recognition elements to create sensors with exceptional sensitivity and specificity [7].

Nanobiosensors can be categorized based on their transduction mechanism, including electrochemical, piezoelectric, thermal, optical, and FRET-based biosensors [7]. The incorporation of nanoparticles enhances sensor performance through various mechanisms: AuNPs reduce electron transfer resistance and exhibit unique optical properties; AgNPs provide high reflectivity with enhanced thermal and electric conductivity; while carbon nanotubes offer higher conductivity with significant propensity for functionalization [7].

These advanced sensing platforms enable real-time monitoring of ROS in plant systems, providing opportunities for early detection of stress responses before visible symptoms appear [5] [7]. The integration of portable devices and artificial intelligence with these nanosensors further enhances their practical application in agricultural monitoring and precision farming [5] [7].

Best Practice Guidelines for ROS Measurement in Plant Research

Specificity and Validation Requirements

Based on current consensus guidelines, researchers should adhere to several key recommendations when measuring ROS in biological systems [24] [25]:

Identify Specific ROS: Wherever possible, the actual chemical species involved in a biological process should be stated, with consideration given to whether observed effects are compatible with its reactivity, lifespan, and reaction products [25].

Validate with Multiple Approaches: Correlative use of multiple detection methods provides stronger evidence than reliance on a single technique. For example, EPR measurements should be correlated with oxidative damage biomarkers [27].

Employ Controlled Generation Systems: Use genetically encoded systems like D-amino acid oxidase for H₂O₂ or targeted compounds like MitoPQ for mitochondrial superoxide to establish causal relationships [25].

Implement Proper Controls: Include appropriate controls for probe specificity, potential artifacts, and non-specific effects, particularly when using fluorescent probes [24] [26].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Specific ROS Detection

| Reagent/Method | Target ROS | Mechanism of Action | Applications in Plant Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| MitoSOX Red | Mitochondrial superoxide | Cationic derivative of dihydroethidium; oxidized to fluorescent product | Specific detection of mitochondrial superoxide in plant cells |

| Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green | Singlet oxygen (¹O₂) | Highly selective reaction with ¹O₂ producing green fluorescence | Detection of singlet oxygen generated during photosensitization |

| D-amino acid oxidase | Controlled H₂O₂ generation | Genetically encoded system producing H₂O₂ from D-amino acids | Regulated generation of H₂O₂ in specific cellular compartments |

| Electron Paramagnetic Resonance | Radical species | Direct detection of unpaired electrons in radical species | Quantitative measurement of specific radicals in plant tissues |

| Nanobiosensors | Multiple specific ROS | Nanomaterial-enhanced detection with biological recognition elements | Real-time monitoring of ROS in plant stress responses |

Diagram 2: Nano-Enabled Biosensor Architecture for ROS Detection. This diagram illustrates the components and signal transduction pathway in nanomaterial-enhanced biosensors for specific ROS detection.

The field of ROS detection is rapidly evolving, with emerging technologies offering unprecedented specificity and sensitivity. Nano-enabled biosensors represent particularly promising tools for plant research, combining the molecular recognition capabilities of biological elements with the enhanced physical properties of nanomaterials [7]. Future developments should focus on improving sensor stability, multiplex detection capability, and user-friendly field applications to facilitate widespread adoption in agricultural research and practice [7].

The integration of ROS detection with omics technologies and AI-based analysis tools will further enhance our understanding of redox signaling networks in plants [5]. Additionally, non-invasive imaging platforms such as IVIS (in vivo imaging system) offer potential for real-time monitoring of ROS in fruits and vegetables during postharvest storage, enabling improved quality management [5].

In conclusion, overcoming the limitations of conventional ROS measurement methods requires a fundamental shift in research approach—from treating ROS as a generic entity to specifically identifying individual chemical species using validated, fit-for-purpose methodologies. By adhering to established best practices and leveraging emerging technologies, researchers can generate more reliable data that advances our understanding of ROS roles in plant biology and facilitates the development of effective strategies for managing oxidative stress in agricultural systems.

The detection of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in plants is pivotal for understanding stress signaling, defense mechanisms, and overall plant physiology. Traditional methods such as spectrophotometry and chromatography have long been the cornerstone for ROS analysis. However, their invasive nature, limited spatiotemporal resolution, and inability to provide real-time, in vivo data have constrained their utility in dynamic plant studies. This whitepaper delineates the transformative potential of nanosensors—nanoscale devices that transduce biological interactions into measurable signals—over conventional approaches. By leveraging advanced nanomaterials and novel sensing mechanisms, nanosensors facilitate non-destructive, real-time monitoring of ROS with exquisite sensitivity and specificity. Framed within the context of a broader thesis on nanosensors for ROS detection in plant research, this technical guide elucidates the operational principles, showcases experimental protocols, and presents quantitative performance comparisons, underscoring how nanosensors are redefining the landscape of plant redox biology and precision agriculture.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), including hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), superoxide anion (O₂⁻), and hydroxyl radicals (•OH), are central signaling molecules in plants, mediating responses to abiotic and biotic stresses such as drought, salinity, pathogens, and extreme temperatures [12] [28]. However, an imbalance leading to oxidative stress can cause significant damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA, ultimately affecting crop yield and quality [29]. Accurate detection of ROS is therefore essential for unraveling plant stress response networks and developing strategies for improved crop management.

Traditional methods for ROS detection have primarily relied on spectrophotometric and chromatographic techniques:

- Spectrophotometric assays (e.g., using dithiothreitol (DTT) or detecting thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) for lipid peroxidation) measure bulk changes in absorbance to infer ROS levels or oxidative damage [30] [29].

- Chromatographic methods (e.g., Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry, LC-MS) provide high sensitivity for detecting specific oxidative damage biomarkers like malondialdehyde (MDA) or 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) [29].

While these methods are well-established, they share significant limitations in the context of living plant research:

- Destructive and End-Point: They typically require homogenization of plant tissue, preventing real-time monitoring and dynamic analysis of the same specimen [12] [31].

- Poor Spatiotemporal Resolution: They provide an average measurement from a bulk sample, obliterating critical information about the spatial heterogeneity and rapid flux of ROS signaling within different tissues, cells, or organelles [13] [28].

- Indirect Measurement: Many are "fingerprinting" methods that detect the downstream molecular damage caused by ROS (e.g., lipid peroxidation, protein carbonylation) rather than the ROS molecules themselves, making it difficult to capture initial signaling events [29].

- Lack of Real-Time Capability: The sample preparation and analysis time makes them unsuitable for tracking rapid physiological changes in real-time [12].

These constraints highlight the pressing need for advanced tools that can directly, sensitively, and non-invasively monitor ROS dynamics within living plants.

Nanosensor Fundamentals and Comparative Advantages

Nanosensors are defined as selective transducers with a characteristic dimension on the nanometre scale [13] [31]. They are engineered by combining a biological recognition element (e.g., an enzyme, antibody, or synthetic bioreceptor) with a nanomaterial-based transducer (e.g., carbon nanotubes, quantum dots, or metallic nanoparticles). This confluence endows them with unique physicochemical properties that directly address the shortcomings of traditional methods.

Table 1: Core Advantages of Nanosensors over Traditional Methods for ROS Detection in Plants

| Feature | Traditional Spectrophotometry/Chromatography | Nanosensors | Impact on Plant ROS Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Type | Destructive; requires tissue homogenization | Non-destructive and minimally invasive [12] [32] | Enables longitudinal studies on the same plant, tracking stress progression and recovery. |

| Temporal Resolution | Minutes to hours; end-point measurement | Real-time to seconds; continuous monitoring [12] [13] | Allows observation of rapid ROS bursts and signaling waves immediately following stress stimuli. |

| Spatial Resolution | Bulk tissue analysis (low resolution) | Cellular and sub-cellular level resolution [13] [28] | Maps ROS gradients and hotspots within tissues, revealing localized signaling events. |

| Sensitivity | Micromolar (µM) range | Nanomolar (nM) to picomolar (pM) range; e.g., 0.43 µM for H₂O₂ [12] | Enables detection of trace-level, physiologically relevant ROS signaling molecules. |

| Specificity | Can be interfered with by other reactive species | High specificity via engineered bioreceptors (e.g., POMs for H₂O₂) [12] | Reduces false positives and allows discrimination between different ROS. |

| In Vivo Applicability | Not possible for real-time in vivo monitoring | Designed for in vivo and in planta use [12] [32] | Provides data in the native physiological context, preserving cellular integrity and signaling networks. |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental conceptual shift from destructive, bulk analysis to non-destructive, high-resolution sensing.

Technical Mechanisms and Experimental Protocols

Nanosensors for ROS detection operate on diverse transduction principles. Below are detailed methodologies for key nanosensor types cited in recent literature.

The NIR-II Fluorescent "Turn-On" Nanosensor for H₂O₂

This sensor exemplifies a state-of-the-art optical nanosensor that overcomes plant autofluorescence.

Principle: The sensor employs an aggregation-induced emission (AIE) fluorophore as a near-infrared-II (NIR-II, 1000-1700 nm) reporter, co-assembled with polymetallic oxomolybdates (POMs) as a quencher. In its native state, the POMs quench the AIE fluorophore's signal ("turn-off"). Upon encountering H₂O₂, the POMs are oxidized, their NIR absorption decays, and the NIR-II fluorescence is recovered ("turn-on") [12]. The NIR-II window minimizes interference from plant autofluorescence, allowing for high-contrast imaging.

Experimental Protocol:

- Synthesis of AIE1035 Nanoparticles (AIENPs): The NIR-II AIE dye (e.g., AIE1035 with a D-A-D structure) is encapsulated into polystyrene (PS) nanospheres using an organic solvent swelling method [12].

- Synthesis of POM Quenchers: Mo/Cu-POMs are synthesized via acidification of sodium molybdate and copper salt solutions, creating oxygen vacancies that confer strong NIR absorption and H₂O₂ responsiveness [12].

- Co-assembly of Nanosensor: The AIENPs and Mo/Cu-POMs are co-assembled into a hybrid nanostructure. Characterization via Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) confirms uniform assembly and chemical composition [12].

- Plant Application and Imaging: The nanosensor is introduced to plants via infiltration or root uptake. A custom NIR-II microscopy or macroscopic whole-plant imaging system is used. Fluorescence intensity is monitored before and after application of stress (e.g., light, heat, pathogen). The "turn-on" signal directly correlates with endogenous H₂O₂ production [12].

FRET-Based Nanosensors

Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)-based nanosensors are powerful for monitoring molecular interactions and conformational changes.

Principle: A donor fluorophore (e.g., a Quantum Dot or CFP) transfers energy to an acceptor fluorophore (e.g., an organic dye or YFP) when in close proximity (<10 nm), quenching donor emission. A recognition element that changes conformation upon binding the target analyte (e.g., a ROS-sensitive protein) alters the distance between the fluorophores, modulating the FRET efficiency, which is measured as a ratio of acceptor-to-donor fluorescence [13] [31].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sensor Design: For genetically encoded sensors, a ROS-binding domain (e.g., from a redox-sensitive transcription factor) is sandwiched between a CFP donor and a YFP acceptor. For exogenous sensors, a ROS-specific antibody or peptide is conjugated between a Quantum Dot (donor) and a gold nanoparticle or dye (acceptor) [13] [6].

- Delivery: Genetically encoded sensors are transformed into plants via Agrobacterium. Exogenous sensors are applied to leaves or roots, potentially using a surfactant, and enter through stomata or lateral root junctions [13] [31].

- Imaging and Analysis: Plant tissues are imaged using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) or fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM). The FRET ratio (Ex₍d₎Em₍a₎/Ex₍d₎Em₍d₎) is calculated pixel-by-pixel to generate a ratiometric map of ROS distribution, which is less susceptible to artifacts than intensity-based measurements [13].

Electrochemical Nanosensors

These sensors measure the electrical current or potential change generated by the oxidation or reduction of ROS.

Principle: A working electrode, often functionalized with nanomaterials like carbon nanotubes or graphene oxide to enhance surface area and conductivity, is held at a specific potential. When H₂O₂ or other ROS are oxidized or reduced at the electrode surface, a measurable current (amperometry) or change in potential (potentiometry) is generated [7] [13].

Experimental Protocol:

- Electrode Fabrication: A carbon-based working electrode is modified with a dispersion of carbon nanotubes or graphene oxide. An enzyme like horseradish peroxidase (HRP) may be immobilized on the nanomaterial to enhance specificity for H₂O₂ [7].

- Measurement Setup: The functionalized working electrode, a reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl), and a counter electrode are inserted into the plant apoplast or a extracted apoplastic fluid.

- Signal Acquisition: A constant potential is applied, and the resulting Faradaic current is measured. The current is proportional to the concentration of ROS being oxidized at the electrode surface. Data is calibrated against standard solutions of H₂O₂ [7].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Representative Nanosensors for ROS Detection

| Nanosensor Type | Target Analyte | Mechanism | Sensitivity | Response Time | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIR-II Fluorescent [12] | H₂O₂ | POM Quenching / "Turn-On" | 0.43 µM | ~1 minute | Minimized plant autofluorescence; deep tissue penetration |

| FRET-Based (QD-Ab) [6] | H₂O₂ / Virus | Energy Transfer | ~nM range | Seconds to minutes | Ratiometric; self-referencing for accuracy |

| Electrochemical (CNT) [7] | H₂O₂ | Electron Transfer | ~nM range | Seconds | Highly suitable for portable, field-deployable devices |

| Carbon Nanotube-Based [32] | Auxin (IAA) | Polymer Corona Modulation | Not Specified | Real-Time | Species-independent; no genetic modification required |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and application of these sophisticated tools rely on a suite of specialized materials and reagents.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nanosensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function in Nanosensor Development | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Aggregation-Induced Emission (AIE) Fluorophores | Stable, bright NIR-II fluorescence reporters that emit strongly in the aggregated state. | Core component of the NIR-II "turn-on" H₂O₂ sensor [12]. |

| Polymetallic Oxomolybdates (POMs) | Act as H₂O₂-responsive quenchers; their oxidation by H₂O₂ disrupts their quenching ability. | Key to the activation mechanism in the NIR-II nanosensor [12]. |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) | Semiconductor nanoparticles serving as bright, photostable FRET donors. | Used in FRET-based sensors for pathogen and ROS detection [6]. |

| Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs) | Serve as the fluorescence transducer in the NIR-II window; their fluorescence is modulated by a surface coating. | Used in the universal nanosensor for plant hormone detection [32]. |

| Specific Antibodies & Enzymes | Biorecognition elements that provide high specificity to the target analyte (ROS, hormone, pathogen). | Immobilized on QDs or electrodes for targeted detection [7] [6]. |

Integrated Workflow and Data Analysis with Machine Learning

The power of nanosensors is fully realized when their output is integrated with advanced data analysis techniques. A prominent example involves coupling NIR-II imaging with machine learning (ML) for stress classification.

The workflow below synthesizes the sensing and data analysis pipeline for classifying plant stress responses using nanosensor data.

As demonstrated in a recent study, the NIR-II fluorescent nanosensor was used to monitor H₂O₂ in plants subjected to four different stress types. The spatiotemporal fluorescence data was used to extract features (e.g., signal onset time, maximum intensity, duration). This dataset was then used to train a machine learning model, which learned to accurately differentiate between the stress types with an accuracy exceeding 96.67% [12]. This integration moves beyond simple detection to intelligent diagnostics, offering a pathway for automated, precise stress identification in agriculture.

Nanosensors represent a paradigm shift in plant ROS research, offering an unparalleled toolkit for direct, non-invasive, and high-resolution analysis that is impossible with traditional spectrophotometric and chromatographic methods. Their ability to provide real-time, in vivo data on the dynamics of ROS signaling is fundamentally enhancing our understanding of plant stress physiology and redox biology.

The future of this field is bright and points toward several key directions:

- Multiplexing: Combining multiple nanosensors to simultaneously monitor ROS, hormones, ions, and other signaling molecules, providing a holistic view of plant signaling networks [28] [32].

- Field Deployment and Integration: The development of portable, smartphone-integrated readers and lab-on-a-chip platforms will translate these laboratory breakthroughs into practical tools for precision agriculture, enabling farmers to make data-driven decisions [7] [6].

- Advanced Material Design: The continuous discovery of new nanomaterials and biorecognition elements will yield sensors with even greater sensitivity, stability, and specificity.

In conclusion, the transition from traditional methods to nanosensor-based approaches is not merely an incremental improvement but a transformative leap. By unlocking the ability to observe the hidden language of ROS in living plants, nanosensors are poised to play a central role in addressing global challenges in food security and sustainable agriculture.

Nanosensor Technologies for ROS Monitoring: Designs, Mechanisms, and Practical Implementations

Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)-based nanosensors represent a powerful class of analytical tools that have revolutionized our ability to detect and quantify biological molecules in live cells and organisms. These sensors operate on the principle of non-radiative energy transfer between two fluorophores when they are in close proximity (typically 1-10 nm), resulting in a measurable change in fluorescence output that can be correlated with analyte concentration [33] [34]. The ratiometric nature of FRET measurements—calculating the ratio between acceptor and donor emission intensities—provides an internal calibration that minimizes artifacts from variations in sensor concentration, excitation intensity, and environmental effects [35] [36].

The integration of FRET nanosensors into plant stress response research, particularly for reactive oxygen species (ROS) detection, offers unprecedented opportunities to understand early signaling events in stress adaptation. As plants lack specialized immune cells, their ability to perceive and respond to environmental challenges relies heavily on sophisticated cell-to-cell communication networks where ROS such as hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) serve as critical signaling molecules [12]. This technical guide comprehensively examines both genetically encoded and exogenous FRET-based platforms, their operational principles, implementation methodologies, and applications within the specific context of plant ROS research.

Fundamental Principles of FRET Biosensing

Theoretical Framework

FRET efficiency depends critically on several physical parameters according to the Förster theory. The efficiency (E) of energy transfer is calculated using the equation:

[E = \frac{R0^6}{R0^6 + R^6}]

where R represents the distance between donor and acceptor fluorophores, and R₀ is the Förster radius—the distance at which energy transfer efficiency is 50% [33]. The Förster radius itself depends on multiple factors as described by:

[R0 = \frac{9000(ln10)QDJ(λ)K^2}{128π^5n^4N_A}]