Multiplex Genome Editing in Plants: A Comprehensive Guide to Engineering Polygenic Traits

This article provides a comprehensive examination of multiplex genome editing technologies and their transformative applications in plant biology.

Multiplex Genome Editing in Plants: A Comprehensive Guide to Engineering Polygenic Traits

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of multiplex genome editing technologies and their transformative applications in plant biology. Aimed at researchers and biotechnology professionals, it covers foundational CRISPR/Cas systems for simultaneous multi-gene modification, advanced methodological approaches for trait stacking, troubleshooting for unintended effects and technical challenges, and current validation frameworks. The content synthesizes recent breakthroughs—from USDA-funded tomato studies to genome-scale CRISPR libraries—offering both theoretical understanding and practical implementation guidance for engineering complex polygenic traits like climate resilience and nutritional improvement in diverse plant systems.

Understanding Multiplex Genome Editing: Principles and Potential

Multiplex genome editing (MGE) represents a transformative advancement in genetic engineering, enabling the simultaneous modification of multiple genomic loci within a single experiment [1]. This approach has become a foundational platform for addressing complex biological questions in plant research, where many agronomic traits are controlled by multiple genes rather than single entities [2] [3]. Unlike earlier genome editing methods that targeted individual sites, MGE allows researchers to dissect gene families, overcome genetic redundancy, engineer polygenic traits, and accelerate trait stacking for crop improvement [2]. The core principle involves using programmable nucleases, particularly CRISPR-Cas systems, to create targeted double-strand breaks at multiple predetermined sites in the genome, leveraging the cell's endogenous repair mechanisms to generate diverse genetic outcomes [4] [1]. This capability is revolutionizing plant biotechnology by facilitating sophisticated applications such as de novo domestication, combinatorial trait engineering, and complex metabolic pathway manipulation [2].

Key Applications in Plant Research

Multiplex editing has enabled breakthrough applications in plant functional genomics and crop improvement. Table 1 summarizes several demonstrated applications with their specific targets and outcomes.

Table 1: Applications of Multiplex Genome Editing in Plant Research

| Application Area | Plant Species | Target Genes/Loci | Number of Targets | Key Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Resistance | Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) | Csmlo1, Csmlo8, Csmlo11 | 3 | Achieved full resistance to powdery mildew | [2] |

| Disease Resistance | Rice | TFIIAγ5, xa23 (converted to Xa23SW11) | 2 | Broad-spectrum resistance against Xanthomonas oryzae | [5] |

| Herbicide Tolerance & Disease Resistance | Rice | OsEPSPS1, OsSWEET11a | 2 | Co-editing for herbicide tolerance and pathogen resistance | [5] |

| Herbicide Tolerance & Disease Resistance | Rice | OsEPSPS1, OsALS1, TFIIAγ5, OsSWEET11a | 4 | Quadruple editing for combined traits | [5] |

| Functional Genomics | Arabidopsis | Various gene families | Up to 12 | Accelerated characterization of redundant gene functions | [2] |

| Metabolic Engineering | Medicinal Plants | Alkaloid, flavonoid, terpenoid pathways | Varies | Enhanced production of valuable secondary metabolites | [6] |

A landmark demonstration in cucumber showed that triple mutants (Csmlo1 Csmlo8 Csmlo11) were necessary to achieve full powdery mildew resistance, highlighting how MGE can address genetic redundancy where single-gene knockouts are insufficient [2]. In rice, a modular prime editing system successfully edited up to four genes simultaneously, with the quadruple editing achieving a co-editing efficiency of 43.5% in the T0 generation, producing plants with combined herbicide tolerance and disease resistance [5].

Technical Approaches and Experimental Workflows

Multiplex editing relies on sophisticated molecular toolkits for simultaneous targeting. The most advanced systems utilize CRISPR-Cas platforms, though earlier technologies like TALENs also offer capabilities [6] [1].

CRISPR-based Multiplexing Strategies

The core innovation enabling CRISPR multiplexing involves the expression of multiple guide RNAs (gRNAs) from a single construct. Several architectural strategies have been developed for this purpose:

- Polycistronic tRNA-gRNA Arrays: Utilizes endogenous tRNA processing systems to liberate individual gRNAs from a single transcript [2].

- Ribozyme-Mediated Processing: Employs self-cleaving ribozymes (e.g., HH and HDV) flanking each gRNA to achieve precise processing [2].

- crRNA Arrays: Direct synthesis of CRISPR arrays mimicking native bacterial systems, though this can present challenges with genetic stability in plant systems [2] [1].

- Modular Assembly Systems: Golden Gate assembly or "PCR-on-ligation" methods enable modular construction of cassettes containing up to 10 gRNAs [4] [5].

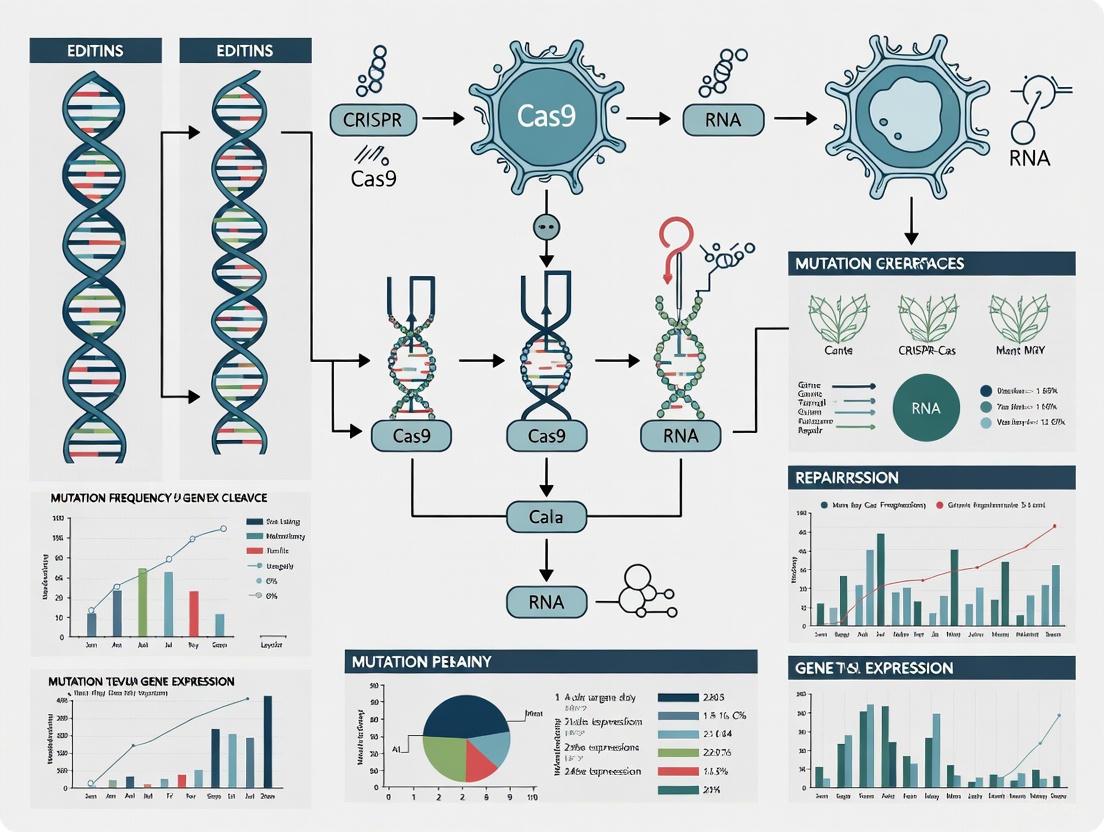

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for a typical multiplex genome editing experiment in plants using a CRISPR-based approach.

Beyond Knockouts: Advanced Editing Platforms

While early multiplexing focused on gene knockouts, recent advances have expanded the capabilities:

- Base Editors: Enable precise nucleotide conversions without double-strand breaks across multiple loci [1].

- Prime Editors: Offer enhanced precision for targeted insertions, deletions, and all base-to-base conversions simultaneously at multiple sites [5].

- Epigenetic Editors: Allow simultaneous modification of epigenetic marks at multiple genomic loci to modulate gene expression [2] [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Multiplex Prime Editing in Rice

This protocol details the methodology for modularly assembled multiplex prime editing in rice, based on published work achieving editing of up to four genes with high efficiency [5].

Reagents and Equipment

- Plant Material: Rice seeds (Oryza sativa L.) of desired cultivar

- Vector System: Modular assembly-compatible backbone with plant codon-optimized prime editor (PE)

- Enzymes: Type IIS restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI, BbsI) for Golden Gate assembly

- Culture Media: LB medium, rice callus induction medium (N6), regeneration medium

- Equipment: Thermal cycler, electroporator, plant growth chambers, sterile laminar flow hood

Procedure

Step 1: pegRNA and ngRNA Design and Synthesis

- Design prime editing guide RNAs (pegRNAs) and nicking gRNAs (ngRNAs) for each target locus following established guidelines [5].

- Ensure pegRNAs contain reverse transcriptase template (RTT) and primer binding site (PBS) sequences optimized for each target edit.

- Synthesize oligonucleotides for each pegRNA and ngRNA with appropriate overhangs for modular assembly.

Step 2: Multiplex Vector Construction

- Perform Golden Gate assembly to clone multiple pegRNA-ngRNA pairs into the modular PE vector.

- Use a stepwise assembly strategy for higher-order multiplexing (e.g., first assemble duplex modules, then combine).

- Verify assembly by diagnostic restriction digest and Sanger sequencing of the final construct.

Step 3: Rice Transformation

- Introduce the assembled multiplex PE vector into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 via electroporation.

- Infect embryogenic rice calli with the transformed Agrobacterium.

- Co-cultivate for 3 days at 25°C in the dark on filter papers placed on co-cultivation medium.

- Transfer calli to selection medium containing appropriate antibiotics (e.g., hygromycin) for 4-6 weeks with biweekly subculturing.

Step 4: Regeneration and Plant Recovery

- Transfer antibiotic-resistant calli to pre-regeneration medium for 1-2 weeks.

- Transfer developing shoots to regeneration medium for plantlet development.

- Transfer regenerated plantlets to rooting medium for 2-3 weeks.

- Acclimate established plantlets to soil and grow to maturity in controlled growth chambers.

Step 5: Molecular Analysis of Edited Plants

- Extract genomic DNA from leaf tissue of T0 plants.

- Perform PCR amplification of each target locus using gene-specific primers.

- Sequence amplicons using Sanger or next-generation sequencing to identify edits.

- Analyze sequencing data to determine editing efficiency and specificity for each target.

Timing and Efficiency

- Vector Construction: 2-3 weeks

- Rice Transformation and Regeneration: 12-16 weeks

- Molecular Analysis: 2-3 weeks

- Expected Efficiency: Co-editing rates of 43.5-57.14% for 2-4 targets in T0 generation based on published results [5]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of multiplex genome editing requires specialized reagents and tools. Table 2 catalogues essential research reagent solutions for designing and executing MGE experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Multiplex Genome Editing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Multiplex Editing | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Effectors | Cas9, Cas12a, Cas12f (CasMINI), Cas12j2, Cas12k [1] | Programmable nucleases that create DSBs at target sites | Smaller variants enable delivery constraints; varying PAM requirements expand target range |

| Editing Platforms | Base editors, Prime editors [5] [7] | Enable precise edits without DSBs at multiple loci | Reduce unintended mutations; prime editors offer greater versatility |

| gRNA Expression Systems | tRNA-gRNA arrays, Ribozyme-flanked gRNAs, Synthetic modular designs [2] [1] | Express multiple gRNAs from single transcriptional unit | Processing efficiency affects editing outcomes; genetic stability varies between systems |

| Delivery Platforms | Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Gold particle bombardment, Viral vectors, Lipid nanoparticles [1] | Introduce editing machinery into plant cells | Species-dependent efficiency; affects complexity of editing outcomes |

| Detection Methods | AmpSeq, PCR-CE/IDAA, ddPCR, Sanger sequencing [8] | Identify and quantify editing outcomes at multiple loci | Sensitivity varies; AmpSeq most comprehensive for complex outcomes |

Detection and Analysis of Editing Outcomes

Accurate detection and quantification of edits across multiple loci present significant technical challenges. For multiplex editing, targeted amplicon sequencing (AmpSeq) is considered the gold standard as it provides single-base resolution of all editing events, including complex outcomes that may be missed by other methods [2] [8]. When designing detection strategies, consider that standard techniques like T7E1 assay and PCR-RFLP have limited sensitivity for detecting low-frequency edits in heterogeneous plant tissues and cannot comprehensively detect the full spectrum of mutations [8]. Specialized computational pipelines are essential for analyzing sequencing data from multiplex editing experiments, particularly for identifying structural variations such as large deletions, inversions, or translocations that may occur when targeting tandemly arranged genes or repetitive elements [2].

Technical Challenges and Considerations

Despite its powerful capabilities, MGE presents several technical challenges that researchers must address:

- Construct Stability: Repeats in gRNA arrays can cause recombination in bacterial hosts during vector propagation [2].

- Editing Efficiency Variation: Different gRNAs exhibit varying efficiencies, leading to inconsistent editing across targets [5].

- Somaclonal Variation: Tissue culture during plant regeneration can introduce unintended mutations independent of editing.

- Structural Variations: Simultaneous cutting at multiple sites can cause chromosomal rearrangements, especially when targets are physically close [4] [3].

- Analytical Complexity: Comprehensive genotyping of plants with edits at multiple loci requires sophisticated methodologies [2] [8].

Ongoing research is addressing these limitations through improved vector designs, optimized gRNA selection algorithms, and enhanced detection methods. As these tools evolve, multiplex genome editing is poised to become an increasingly robust and accessible technology for plant research and crop improvement.

Multiplex genome editing represents a transformative advance in plant biotechnology, enabling the simultaneous modification of multiple genetic loci within a single experiment. This capability is particularly crucial for addressing two fundamental challenges in plant genomics and breeding: polygenic traits, which are controlled by multiple genes, and genetic redundancy, where duplicated genes or gene family members perform overlapping functions [2]. The pervasive nature of gene duplications and gene families in plant genomes means that traditional single-gene editing approaches often fail to produce meaningful phenotypic changes due to functional compensation among paralogs [2]. While early genome editing focused successfully on single-gene traits, many agriculturally important characteristics—including climate resilience, yield components, and complex disease resistance—are governed by complex genetic networks that require coordinated manipulation of multiple loci [9].

The emergence of CRISPR-Cas systems has made multiplex editing practically feasible in plants. Unlike earlier technologies such as ZFNs and TALENs, which required extensive protein engineering for each new target, CRISPR systems use programmable RNA molecules to guide Cas nucleases to specific DNA sequences, significantly simplifying the process of targeting multiple sites [1]. Native CRISPR-Cas systems in bacteria and archaea naturally encode arrays of spacers and are inherently capable of multiplexing, a capability that researchers have now repurposed for eukaryotic genome engineering [2]. This technical breakthrough has opened new possibilities for dissecting gene family functions, engineering polygenic agronomic traits, accelerating trait stacking, and pursuing de novo domestication of wild species [2].

Technical Approaches to Multiplex Genome Editing

CRISPR Systems and Vector Architectures

Several CRISPR systems have been successfully adapted for multiplex editing in plants, each with distinct advantages. The most widely used systems include CRISPR-Cas9, CRISPR-Cas12a, and newer, more compact variants such as Cas12j2 and CasMINI that facilitate delivery [1]. These systems can be deployed through various vector architectures designed to express multiple guide RNAs (gRNAs) simultaneously:

- Polycistronic tRNA-gRNA Arrays (PTA): This architecture exploits the endogenous tRNA processing system, where synthetic tRNA sequences are inserted between gRNA units and are recognized by cellular enzymes that cleave them into individual functional gRNAs [2].

- Ribozyme-Mediated Systems: Certain self-cleaving ribozymes (e.g., HH and HDV) can flank gRNA units, processing themselves out of the transcript to release individual gRNAs [1].

- CRISPR RNA (crRNA) Arrays: Native to type I and III systems, these can be engineered for use with Cas12a, which processes its own crRNAs from a single transcript [1].

The choice of promoter systems is equally critical for successful multiplex editing. Strong Pol III promoters (e.g., U6 and U3) typically drive individual gRNA expression, but recent advances have also demonstrated the utility of Pol II promoters for expressing processed gRNA arrays, especially when combined with ribozyme sequences [2]. Engineering efforts have focused on optimizing these promoters and developing scaffold modifications to enhance editing efficiency and stability in both bacterial intermediates (E. coli and Agrobacterium) and eventual plant hosts [2].

Advanced Editing Modalities

Beyond simple knockout mutations, multiplex editing now encompasses diverse editing modalities:

- Base Editing: Catalytically impaired Cas nucleases fused to deaminase enzymes enable precise nucleotide conversions without creating double-strand breaks, allowing simultaneous correction of multiple point mutations [1].

- Prime Editing: PE systems using Cas nickase-reverse transcriptase fusions can mediate all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, as well as small insertions and deletions, with minimal indel formation, enabling versatile multiplex editing [1].

- Transcriptional and Epigenetic Regulation: Deactivated Cas (dCas) proteins fused to transcriptional activators, repressors, or epigenetic modifiers enable multiplex regulation of gene expression without altering DNA sequence [2].

- Chromosomal Engineering: Simultaneous cuts at multiple target sites can generate large deletions, inversions, or translocations, facilitating chromosomal rearrangements and the study of structural variations [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Major CRISPR Systems for Multiplex Editing

| CRISPR System | PAM Requirement | crRNA Processing | Editing Products | Advantages for Multiplexing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 | 5'-NGG-3' | Requires separate gRNAs or processing systems | Predominantly short indels | High efficiency; extensive validation |

| Cas12a | 5'-TTTV-3' | Self-processes crRNA arrays | Often longer deletions | Simplified array construction |

| Cas12j | 5'-TTN-3' | Compact size; minimal PAM | Short indels | Small size aids delivery |

| Base Editors | Varies by Cas domain | Same as parent Cas | Point mutations | No double-strand breaks; higher precision |

| Prime Editors | Varies by Cas domain | Same as parent Cas | All possible base changes, small indels | Versatile; minimal off-target effects |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Design and Assembly of Multiplex Constructs

The successful implementation of multiplex editing requires careful design and assembly of genetic constructs. The following protocol outlines a standard workflow for creating a tRNA-gRNA array for simultaneous targeting of multiple loci:

Step 1: Target Selection and gRNA Design

- Identify target genes and specific sites for editing. For gene families, identify conserved regions to target multiple paralogs with fewer gRNAs [2].

- Design gRNA sequences (typically 20 nt) with high on-target efficiency and minimal off-target potential using computational tools like CRISPR-P or CHOPCHOP.

- Ensure each gRNA is flanked by appropriate restriction sites for cloning.

Step 2: Vector Selection and Preparation

- Select a binary vector containing a plant codon-optimized Cas9 nuclease driven by a constitutive promoter (e.g., CaMV 35S or Ubiquitin).

- Verify the presence of a multiple cloning site or specific gRNA expression cassette insertion site.

Step 3: Oligonucleotide Synthesis and Array Assembly

- Synthesize oligonucleotides corresponding to each gRNA sequence.

- For tRNA-gRNA array assembly, design overlapping PCR primers that incorporate tRNA sequences between gRNA units.

- Assemble the array through successive PCR reactions or Golden Gate cloning.

Step 4: Bacterial Transformation and Sequence Verification

- Transform the assembled construct into E. coli for amplification, then into Agrobacterium tumefaciens for plant transformation.

- Isolate plasmid DNA and verify the complete array sequence by Sanger sequencing or long-read sequencing technologies.

Plant Transformation and Regeneration

The following workflow describes a standard Agrobacterium-mediated transformation protocol for delivering multiplex editing constructs to plants:

Materials and Reagents:

- Plant explant material (e.g., leaf discs, embryogenic callus, shoot apices)

- Agrobacterium strain (e.g., LBA4404, GV3101) carrying the multiplex editing construct

- Plant culture media: co-cultivation, selection, and regeneration media appropriate for the target species

- Antibiotics for bacterial and plant selection (e.g., kanamycin, hygromycin)

- Plant growth regulators (e.g., auxins, cytokinins)

Procedure:

- Pre-culture: Culture explants on appropriate pre-culture medium for 1-2 days.

- Bacterial Preparation: Grow Agrobacterium overnight to OD600 = 0.5-1.0, then resuspend in infection medium.

- Inoculation: Immerse explants in the Agrobacterium suspension for 10-30 minutes with gentle agitation.

- Co-cultivation: Transfer explants to co-cultivation medium and incubate in the dark for 2-3 days.

- Selection: Transfer explants to selection medium containing antibiotics to eliminate Agrobacterium and select for transformed plant cells.

- Regeneration: Transfer developing shoots to regeneration medium to promote plantlet development.

- Rooting and Acclimatization: Induce root formation, then transfer plantlets to soil under controlled conditions.

The entire process typically requires 3-6 months, depending on the plant species and transformation efficiency.

Diagram Title: Multiplex Genome Editing Workflow

Mutation Detection and Analysis

Characterizing editing outcomes in multiplex experiments presents unique challenges due to the simultaneous modifications at multiple loci. The following protocol describes a comprehensive approach for mutation detection:

DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

- Extract genomic DNA from edited plant tissues using CTAB or commercial kits.

- Design PCR primers flanking each target site, ensuring amplicons of 400-800 bp.

- Perform multiplex PCR or individual PCR reactions for each target.

Mutation Detection Methods

- Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP): For targets where editing disrupts a restriction site, perform digestions and analyze fragments by gel electrophoresis.

- High-Resolution Melting (HRM) Analysis: Screen for sequence variations by detecting differences in DNA melting behavior.

- Sanger Sequencing with Deconvolution: Sequence PCR products and use tools like TIDE or ICE to quantify editing efficiency and characterize mutation spectra.

- Amplicon Sequencing: For comprehensive analysis, barcode and sequence target amplicons on Illumina platforms to detect all mutation types at each target.

Advanced Approaches for Complex Edits

- Long-read Sequencing: Use PacBio or Oxford Nanopore technologies to detect large structural rearrangements and chromosomal abnormalities [2].

- Target Capture Sequencing: Enrich and sequence large genomic regions to comprehensively assess on-target and off-target edits.

Table 2: Mutation Detection Methods for Multiplex Editing Analysis

| Method | Throughput | Sensitivity | Information Obtained | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger Sequencing + Deconvolution | Medium | Moderate | Mutation types, efficiency | Initial screening; small target numbers |

| Amplicon Sequencing | High | High | Comprehensive mutation spectrum | Detailed characterization; many targets |

| HRM Analysis | High | Moderate | Presence/absence of edits | Rapid screening of large populations |

| RFLP Analysis | Low | Low | Specific mutation types | Targets with restriction site disruption |

| Long-read Sequencing | Low | High for large edits | Structural variations, complex rearrangements | Chromosomal engineering; tandem arrays |

Applications in Addressing Polygenic Traits and Genetic Redundancy

Overcoming Genetic Redundancy in Gene Families

Genetic redundancy through gene duplication and the expansion of gene families presents a significant challenge in functional genomics, as knocking out single genes often fails to produce phenotypic consequences due to functional compensation by paralogs. Multiplex editing provides a powerful solution by enabling simultaneous targeting of multiple family members.

A compelling example comes from engineering powdery mildew resistance. In monocots like barley and wheat, single-gene knockouts of the Mildew Resistance Locus O (MLO) confer broad-spectrum resistance [2]. However, in dicot species, achieving durable resistance requires simultaneous knockout of multiple MLO homologs. In Arabidopsis thaliana, researchers initially generated triple mutants (Atmlo2 Atmlo6 Atmlo12) through successive crosses of single mutants [2]. More recently, multiplex CRISPR editing enabled direct generation of triple mutants in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) by simultaneously targeting three clade V genes (Csmlo1, Csmlo8, and Csmlo11), achieving full resistance to powdery mildew in a single transformation event [2]. These mutants also revealed unexpected roles for calcium signaling components in powdery mildew defense, demonstrating how multiplex approaches can yield novel biological insights beyond their primary target.

In another application, researchers used multiplex editing to characterize gene families involved in cell wall biosynthesis in Arabidopsis, simultaneously targeting three genes with 3-4 gRNAs and recovering transgene-free edited lines through selfing [2]. The ability to generate various combinations of single and multiple gene knockouts in a single transformation experiment has greatly accelerated the functional dissection of redundant gene families.

Engineering Polygenic Agronomic Traits

Many agriculturally important traits are polygenic, controlled by multiple genes that often interact through complex networks. Multiplex editing enables coordinated manipulation of these genetic networks to achieve meaningful phenotypic improvements.

In woody plants, where long generation times severely constrain traditional breeding, multiplex editing offers unprecedented opportunities for rapid improvement of complex traits. For example, researchers have used multiplex CRISPR-Cas9 to simultaneously edit seven closely linked Nucleoredoxin1 (NRX1) genes in poplar (Populus tremula × Populus alba) using a single gRNA targeted to a conserved region in the tandem gene array [9]. This approach induced diverse mutations including small insertions, deletions, and large genomic rearrangements such as translocations and inversions, demonstrating the versatility of multiplex editing for generating structural variations.

In another study focused on improving wood properties for sustainable fiber production, researchers designed 69,123 editing strategies targeting 21 lignin biosynthesis genes in poplar, ultimately selecting seven for experimental validation [9]. From 174 edited variants, they identified lines with up to a 228% increase in the wood carbohydrate-to-lignin ratio, significantly improving pulping efficiency without affecting tree growth. This remarkable achievement highlights the transformative potential of multiplex editing for optimizing complex metabolic pathways.

Similar approaches have been applied to apple trees, where multiplex editing targeting the Phytoene Desaturase (PDS) and Terminal Flower 1 (TFL1) genes achieved high editing efficiency (85-93% of lines showing expected phenotypes) with minimal off-target effects [9]. The generation of T-DNA-free edited lines through transient transformation further demonstrates the potential for developing non-transgenic improved varieties.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of multiplex genome editing requires specialized reagents and tools. The following table summarizes key solutions and their applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Multiplex Genome Editing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Effectors | Cas9, Cas12a, Cas12j, CasMINI | DNA binding and cleavage; newer variants offer smaller size, different PAM requirements |

| Guide RNA Scaffolds | gRNA, crRNA, sgRNA | Target recognition and Cas nuclease recruitment; various designs optimize stability and efficiency |

| Promoter Systems | U6, U3 (Pol III); 35S, Ubiquitin (Pol II) | Drive expression of Cas nuclease and gRNAs; tissue-specific or inducible promoters offer spatial/temporal control |

| Processing Systems | tRNA, ribozymes (HH, HDV) | Release individual gRNAs from polycistronic transcripts; enable multiplexing with single transcriptional unit |

| Delivery Vectors | Binary vectors for Agrobacterium, gold particles for biolistics | Transport editing components into plant cells; different systems suit different species |

| Detection Tools | T7E1 assay, RFLP, amplicon sequencing, long-read sequencing | Identify and characterize editing outcomes; vary in throughput, sensitivity, and information content |

| Plant Culture Media | Co-cultivation, selection, regeneration media | Support plant tissue growth, selection of transformed cells, and regeneration of whole plants |

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

Despite its powerful capabilities, multiplex genome editing presents several technical challenges that researchers must address:

Editing Efficiency Variation Editing efficiency often varies significantly among target sites within a multiplex experiment, with reported efficiencies ranging from 0% to 94% across different targets [2]. This variation can result from differences in gRNA efficiency, chromatin accessibility, or local sequence context. To mitigate this issue:

- Perform careful gRNA design using validated algorithms

- Include multiple gRNAs for critical targets

- Screen larger populations to recover lines with desired combination of edits

Somatic Chimerism In initial transformants (T0), editing events may occur in only a subset of cells, creating mosaic plants with complex genotypic patterns. To address this:

- Advance edited lines through generations (T1, T2) to segregate and stabilize edits

- Use meristem-specific promoters to reduce chimerism

- Apply additional rounds of selection or screening

Construct Assembly and Stability The repetitive elements in gRNA arrays can cause recombination and instability in bacterial hosts. Solutions include:

- Using low-copy number vectors

- Growing bacterial cultures at lower temperatures

- Applying direct synthesis or modular assembly strategies

- Verifying array integrity by long-read sequencing

Detection Complexity Characterizing mutations across multiple targets requires sophisticated genotyping approaches. Recommendations:

- Employ high-throughput amplicon sequencing for comprehensive mutation profiling

- Use bioinformatic tools specifically designed for multiplex editing analysis

- Apply long-read sequencing to detect structural variations often missed by short-read technologies

Off-target Effects While CRISPR systems are highly specific, off-target editing remains a concern, particularly in multiplex applications where multiple gRNAs are expressed simultaneously. Mitigation strategies include:

- Choosing gRNAs with minimal off-target potential using computational prediction tools

- Using high-fidelity Cas variants

- Employing ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes rather than plasmid-based delivery

- Performing whole-genome sequencing to assess off-target activity in final lines

As these technical challenges are addressed through continued innovation, multiplex genome editing is poised to become a foundational technology for plant research and improvement, particularly for addressing the complex genetic architectures underlying agriculturally important traits [2].

The field of genome engineering has been revolutionized by the development of programmable nucleases, enabling precise modifications to DNA sequences at specific genomic locations. This evolution began with Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), advanced with Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and reached a transformative stage with the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)/Cas systems [10] [11]. These technologies have fundamentally changed the landscape of biological research by providing tools for targeted genome modifications across diverse organisms. In plant sciences, this progression is particularly critical for addressing polygenic traits—characteristics controlled by multiple genes—through multiplex genome editing [2] [9]. The ability to simultaneously modify multiple genetic loci has opened new avenues for dissecting complex biological processes, engineering sophisticated agronomic traits, and accelerating crop improvement programs, thereby supporting sustainable agriculture and climate resilience.

Technological Comparison: Mechanism and Design

The core principle shared by ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR/Cas systems involves creating targeted double-strand breaks (DSBs) in the DNA, which are then repaired by the cell's endogenous repair mechanisms. The choice of system significantly impacts experimental design, efficiency, and application potential, especially for complex multiplexing tasks in plant research.

ZFNs are fusion proteins comprising a zinc finger DNA-binding domain and the FokI endonuclease cleavage domain. Each zinc finger module recognizes a 3-4 bp DNA sequence, and multiple modules are assembled to target a longer, specific site (typically 9-18 bp). A functional nuclease requires a pair of ZFNs binding to opposite DNA strands to facilitate FokI dimerization and subsequent DNA cleavage [10] [11]. A significant challenge with ZFNs is the context-dependent specificity of zinc finger arrays, where individual modules can influence the binding of their neighbors, making design and prediction of specificity complex [10].

TALENs are also fusion proteins, combining a Transcription Activator-Like Effector (TALE) DNA-binding domain with the FokI nuclease. The key advantage of TALENs lies in their simple code: each TALE repeat domain is specific for a single nucleotide, with binding specificity determined by two key amino acids (Repeat-Variable Diresidue, RVD). This one-to-one correspondence makes TALEN design more straightforward and reliable than ZFN design [10] [11]. Like ZFNs, TALENs function as pairs to enable FokI dimerization [12].

CRISPR/Cas Systems, most commonly employing the Cas9 nuclease, represent a paradigm shift. Target recognition is mediated by a short guide RNA (sgRNA) through Watson-Crick base pairing with the target DNA sequence, rather than by a protein-DNA interaction [10] [4]. The Cas9 nuclease is directed by the sgRNA to a target site adjacent to a short DNA sequence known as the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM). Upon binding, Cas9 induces a DSB. This RNA-guided mechanism drastically simplifies the redesign process, as only the ~20 nt sgRNA sequence needs to be modified to target a new genomic locus [10] [12].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Genome Editing Technologies

| Feature | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR/Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Recognition Mechanism | Protein-DNA interaction | Protein-DNA interaction | RNA-DNA hybridization [10] |

| Recognition Site Length | 9–18 bp [10] | 30–40 bp [10] | 22 bp + PAM sequence [10] |

| Nuclease Component | FokI | FokI | Cas9 |

| Design & Cloning | Challenging; context-dependent finger specificity [10] | Easy; modular TALE repeats with defined specificity [10] [12] | Very easy; simple sgRNA design and cloning [10] [4] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Low | Low | High; enabled by co-expressing multiple sgRNAs [10] [13] |

| Primary Advantage | First programmable nuclease; smaller size | Simple design code; high binding affinity | Unparalleled ease of design and multiplexing [12] |

| Primary Limitation | Complex design; high cost; off-target toxicity [11] | Large, repetitive vectors difficult to clone [2] | PAM sequence dependency; off-target effects [10] |

Technology Design Workflows

Application Notes: Multiplex Genome Editing in Plant Research

The transition to CRISPR-based systems has unlocked the potential of multiplex genome editing, which is the simultaneous modification of multiple genetic loci in a single transformation event. This capability is indispensable for plant research and biotechnology for several key applications.

Addressing Genetic Redundancy and Gene Families

Plant genomes are characterized by extensive genetic redundancy due to gene duplications and large gene families, which can obscure functional analysis when single genes are knocked out. Multiplex CRISPR enables the simultaneous knockout of multiple paralogous genes, allowing researchers to overcome this redundancy and reveal gene functions [2]. A prime example is engineering powdery mildew resistance. While single-gene knockouts of specific MLO family members confer resistance in barley and wheat (monocots), achieving durable resistance in dicot species like cucumber required the simultaneous knockout of three clade V CsMLO genes (Csmlo1, Csmlo8, Csmlo11) via multiplex editing [2].

Engineering Polygenic Agronomic Traits

Many critical agronomic traits, such as abiotic stress tolerance (drought, heat), disease resistance, and architectural features, are controlled by multiple genes (polygenic). Multiplex editing allows for the precise manipulation of these complex trait networks in a single generation, bypassing the need for lengthy traditional breeding cycles [2] [9]. For instance, in poplar trees, multiplex editing has been applied to simultaneously target multiple genes in the lignin biosynthesis pathway. In one study, editing seven selected genes resulted in variants with up to a 228% increase in the wood carbohydrate-to-lignin ratio, significantly improving pulping efficiency without affecting growth [9]. This demonstrates the power of multiplexing for engineering complex metabolic pathways.

De Novo Domestication and Trait Stacking

Multiplex CRISPR facilitates the rapid introduction of desirable traits into wild or semi-wild species, a process known as de novo domestication [2]. It also allows for the stacking of multiple beneficial traits—such as different disease resistance genes or quality and yield traits—into an elite genetic background simultaneously, drastically accelerating breeding programs.

Experimental Protocols

The practical implementation of multiplex genome editing, particularly with CRISPR/Cas, requires optimized protocols for vector construction, plant transformation, and molecular analysis.

Protocol: Multiplex CRISPR Vector Assembly for Plants

This protocol outlines the Hyper Cloning method, an efficient strategy for constructing CRISPR/Cas9 vectors with polycistronic tRNA-gRNA (PTG) arrays for multiplex editing in plants, as demonstrated in rice [14].

- Principle: The method leverages a polycistronic tRNA-gRNA system where individual gRNA units are separated by tRNA sequences, which are processed in vivo to release multiple functional gRNAs from a single transcript. The "Hyper Cloning" approach enhances efficiency by minimizing the number of DNA fragments required for Golden Gate or Gibson assembly [14].

- Materials:

- Destination vector (e.g., pRGEB32-based) containing a plant-adapted Cas9 gene.

- gRNA scaffold backbone.

- Entry vectors containing target-specific gRNA sequences.

- Type IIS restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI).

- T4 DNA Ligase.

- Gibson Assembly Master Mix.

- Competent E. coli cells.

- Procedure:

- gRNA Design: Design 20-nt target-specific sequences for each gene target, ensuring they are unique in the genome and located adjacent to a 5'-NGG PAM sequence.

- Oligonucleotide Annealing: Synthesize and anneal complementary oligonucleotides for each gRNA target to create double-stranded DNA inserts with BsaI-compatible overhangs.

- Golden Gate Assembly (for individual gRNA modules): Clone each annealed duplex into a separate entry vector containing the gRNA scaffold via a Golden Gate reaction using BsaI.

- Multiplex Array Assembly via Hyper Cloning:

- Use the entry vectors from step 3 as templates for PCR amplification of the tRNA-gRNA units.

- Perform a Gibson Assembly reaction to concatenate these PCR fragments into the final destination vector upstream of the Cas9 gene. The Hyper Cloning method optimizes this step by re-using gRNAs from a specific vector backbone (pRGEB32t), reducing the total number of fragments to be assembled and thereby increasing efficiency [14].

- Transformation and Verification: Transform the final assembly reaction into competent E. coli cells. Select positive clones, confirm the assembly by colony PCR, and validate the final vector by Sanger sequencing.

Protocol: Eliminating Selection Markers from Transgenic Plants

A key application of multiplex editing is the removal of selectable marker genes (SMGs) from transgenic plants to address regulatory and public concerns [15].

- Objective: To excise the SMG cassette from a stably transformed plant line using CRISPR/Cas9, producing marker-free, transgenic plants.

- Materials:

- Transgenic plant line (e.g., Tobacco) harboring the SMG (e.g., DsRED) and gene of interest (GOI).

- Multiplex CRISPR/Cas9 vector with 4 gRNAs targeting the flanking regions of the SMG cassette.

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404.

- Tissue culture media and reagents.

- Procedure:

- Vector Design: Design and clone a minimum of four gRNAs targeting sequences immediately upstream and downstream of the SMG cassette into a CRISPR/Cas9 expression vector [15].

- Plant Re-transformation: Introduce the multiplex CRISPR vector into the established transgenic plant line via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of leaf discs.

- Regeneration and Screening: Regenerate shoots on selection medium. Screen primary regenerants (T0) for the loss of the SMG phenotype (e.g., loss of red fluorescence for DsRED). Approximately 20% of shoots may show this loss [15].

- Molecular Confirmation:

- Perform PCR with primers flanking the SMG cassette. Successful excision results in a smaller amplicon.

- Sequence the PCR products to confirm precise deletion and identify any small indels at the gRNA target sites.

- Use quantitative PCR (qPCR) to confirm the absence of SMG (DsRED) transcript.

- Segregation to Obtain CRISPR-Free Plants: Grow T0 plants to maturity and collect T1 seeds. Screen the T1 progeny for the presence of the GOI and the absence of both the SMG and the Cas9 transgene, thereby recovering transgene-free, marker-free edited plants [15].

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Multiplex CRISPR Plant Genome Editing

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Creates double-strand breaks at target DNA sites. | Codon-optimized versions for plants (e.g., rice, tomato) enhance expression. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Directs Cas9 to specific genomic loci via base pairing. | Designed as 20-nt sequences; multiple gRNAs expressed from a single vector for multiplexing. |

| gRNA Expression Promoter | Drives transcription of gRNAs in plant cells. | Pol III promoters (e.g., U6, U3) are commonly used for high, constitutive expression. |

| Cas9 Expression Promoter | Drives transcription of the Cas9 nuclease. | Strong constitutive promoters (e.g., 35S, Ubiquitin) ensure sufficient nuclease levels. |

| Assembly System | Enables cloning of multiple gRNAs into a single vector. | Golden Gate Assembly with Type IIS enzymes (BsaI) or Gibson Assembly for PTG arrays. |

| Delivery Vector | Transfers CRISPR components into plant cells. | Binary T-DNA vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. |

| Delivery Method | Introduces CRISPR constructs into plant tissue. | Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, biolistics (gene gun). |

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite its transformative potential, the application of multiplex genome editing, particularly in plants, faces several technical and analytical challenges that guide future development.

A primary challenge is the efficient delivery of editing components and the analysis of complex editing outcomes. Somatic chimerism, where not all cells in a regenerated plant contain the same edits, is common in the T0 generation, often requiring segregation to T1 to obtain stable, homozygous edits [2]. Furthermore, simultaneously targeting multiple sites can result in a spectrum of mutations—including large deletions, inversions, and translocations—that are difficult to detect with standard PCR-based genotyping. The adoption of long-read sequencing technologies (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) is improving the detection of these complex structural variations [2].

The future of multiplex editing in plants will be shaped by several key advancements. There is a growing demand for user-friendly computational tools that integrate AI and machine learning to streamline gRNA design, predict off-target effects, and interpret complex editing outcomes [2] [16]. The development of inducible or tissue-specific CRISPR systems will allow for spatiotemporal control of editing, enabling the study of essential genes and complex developmental processes [2]. Finally, ongoing engineering of novel Cas variants (e.g., Cas12a, Cas13) with different PAM requirements, smaller sizes for easier delivery, and higher fidelity will continue to expand the toolbox and precision of plant genome engineers [10] [16].

Challenges and Future Directions

Plant genomes present unique challenges for functional genomics and crop improvement, primarily due to the prevalence of extensive gene families, whole-genome duplication (polyploidy), and functional buffering mechanisms. These characteristics provide plants with evolutionary flexibility and resilience but complicate efforts to link genotype to phenotype, as the effects of modifying a single gene can be masked by redundant paralogs or homoeologs. The emergence of multiplex genome-editing (MGE) technologies, particularly the CRISPR/Cas system, is revolutionizing this landscape by enabling simultaneous modification of multiple genomic loci. This Application Note provides detailed protocols and frameworks for leveraging MGE to overcome these plant-specific challenges, facilitating advanced research and crop improvement strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential reagents and tools for designing and executing multiplex genome-editing experiments in plants.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for Multiplex Genome Editing in Plants

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas Systems | Core nuclease for inducing double-strand breaks at DNA target sites. | Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 is most common; other orthologs (Cas12a) offer different PAM specificities. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) Expression Constructs | Directs Cas nuclease to specific genomic loci via base complementarity. | Multiple gRNAs can be expressed from a single construct using tRNA or ribozyme-based processing systems [17] [18]. |

| TALEN Pairs | Alternative engineered nuclease for targeting specific sequences; effective in polyploids. | A single TALEN pair can target conserved homoeologs, as demonstrated in hexaploid wheat [17] [18]. |

| Hidecan / VIEWpoly | R packages for visualizing GWAS results and differential expression data. | Integrates genomic data to help identify potential gene targets in complex polyploid genomes [19]. |

| Polyploid Genome Assemblies | High-quality, haplotype-resolved reference sequences. | Essential for designing specific gRNAs for all homoeologs/alleles. Platforms include Hi-C, PacBio SMRT, and Oxford Nanopore [20] [21]. |

Quantitative Data from Key Studies in Polyploid Crops

Recent successful applications of MGE in polyploid plants demonstrate its power to modify complex traits. The quantitative data below highlight the efficiency and outcomes of these interventions.

Table 2: Exemplary Multiplex Genome-Editing Outcomes in Polyploid Crops

| Crop Species | Target Gene(s) | Ploidy / Genetic Challenge | Editing Outcome / Efficiency | Phenotypic Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bread Wheat (Triticum aestivum) | Mildew Resistance Locus (MLO) | Hexaploid; three homoeologs (A, B, D) | One TALEN pair mutated all three homoeologs; 1 of 27 T0 plants had triple mutations [17] [18]. | Plants with triple mutations showed complete resistance to powdery mildew (Blumeria graminis) [17] [18]. |

| Sugarcane (Saccharum hybrids) | Caffeic acid O-methyltransferase (COMT) | Complex polyploid; >100 gene copies | A single TALEN pair edited 107 of 109 COMT gene copies [17] [18]. | Significant reduction in lignin content, improved saccharification efficiency by 43.8%, no impact on biomass [17] [18]. |

| Synthetic Hexaploid Wheat | Disease Resistance QTLs | Hexaploid; three sub-genomes | Model incorporating epistasis (ABDI) improved predictive accuracy for disease resistance versus additive-only model [19]. | Accounted for ~50% of genetic variance for Septoria Nodorum Blotch and Spot Blotch [19]. |

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Multiplex Editing of a Gene Family in a Polyploid Crop

This protocol outlines the steps for simultaneously targeting multiple members of a gene family across sub-genomes of a polyploid plant, such as wheat or sugarcane.

1. Target Identification and gRNA Design:

- Genome Assembly Verification: Obtain or generate a chromosome-scale, haplotype-phased genome assembly for the target polyploid crop [20]. Verify assembly quality using Hi-C data or genetic maps.

- Conserved Sequence Analysis: Perform multiple sequence alignment of all target gene homoeologs and paralogs. Identify conserved exon regions (typically 19-22 bp) suitable for a single gRNA or a minimal set of gRNAs to target all copies [17] [18].

- gRNA Selection and Specificity Check: Design gRNAs with the required PAM sequence adjacent to the conserved target site. Use bioinformatics tools (e.g., Cas-OFFinder) to perform a genome-wide search for off-target sites with high sequence similarity, particularly in other gene family members. Select gRNAs with minimal off-target potential.

2. Vector Construction for Multiplex Delivery:

- Assembly of gRNA Array: Clone selected gRNA sequences into a multiplex-ready CRISPR/Cas vector system. Use a strategy such as a tRNA-gRNA array, where individual gRNA units are separated by tRNA sequences, which are processed in vivo to release mature gRNAs [18].

- Selection of Promoters and Terminators: Drive the expression of the gRNA array with a strong, pol III promoter (e.g., U6 or U3). Express the Cas9 nuclease using a constitutive plant promoter (e.g., CaMV 35S or maize Ubiquitin).

- Plant Transformation: Deliver the final construct into the target polyploid crop using Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, biolistics, or other established methods for the species.

3. Molecular Analysis and Genotyping:

- PCR Screening: Isolate genomic DNA from transformed (T0) plants. Perform PCR amplification of the targeted genomic regions from all anticipated homoeologs.

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Amplicons must be deep-sequenced using next-generation sequencing (NGS) to capture the full spectrum of mutations across all gene copies in the polyploid background. This is critical, as Sanger sequencing produces overlapping traces from different homoeologs that are difficult to deconvolute.

- Variant Calling and Phasing: Use specialized bioinformatic pipelines designed for polyploids (e.g, HDmapper, PolyCat) to accurately call heterozygous and homozygous indels and assign them to specific sub-genomes [20] [21].

4. Phenotypic Validation:

- Select T0 plants with confirmed mutations in the maximum number of target gene copies for immediate phenotyping, if the trait is visible at this stage.

- Grow the T1 progeny of edited lines and conduct detailed phenotyping alongside wild-type controls under controlled environment or field conditions, depending on the trait (e.g., disease resistance, lignin content, yield components).

Protocol: Integrating Genomic Prediction with Multiplex Editing

This protocol leverages genomic selection models to prioritize targets for multiplex editing, increasing the efficiency of breeding for complex quantitative traits.

1. Population Phenotyping and Genotyping:

- Develop Training Population: Assemble a diverse population of several hundred lines of the target polyploid crop.

- High-Density Genotyping: Genotype the entire population using a high-density SNP array or through whole-genome re-sequencing.

- Multi-Environment Trials (MET): Phenotype the population for the target quantitative trait(s) (e.g., yield, drought tolerance) across multiple locations and seasons to capture GxE interactions [19].

2. Model Training and Validation:

- Genomic Prediction Model: Use the phenotypic and genotypic data from the training population to train a genomic prediction model. For polyploids, ensure the model accounts for allele dosage and, if possible, epistatic interactions [19].

- Model Validation: Validate the prediction accuracy of the model using cross-validation within the training population or an independent validation set.

3. Selection and Editing of Elite Haplotypes:

- In Silico Prediction: Apply the trained model to a panel of elite breeding lines to predict their breeding value for the target trait.

- Haplotype Mining: Identify and select favorable haplotypes (combinations of alleles) associated with high trait value from the top-performing predictions.

- Multiplex Editing Strategy: Design gRNAs to introduce the favorable haplotype sequence into recipient lines via HDR (if feasible) or to knockout negative regulators of the pathway. This may involve editing multiple QTLs/genes simultaneously.

4. Integration into Breeding Pipeline:

- Edited lines are advanced in the breeding program.

- The training population for genomic prediction is periodically updated with data from new cycles of selection and editing, creating a feedback loop for continuous model improvement.

Application Note: Engineering Climate-Resilient Crops via Multiplex Genome Editing

Multiplex genome editing represents a transformative platform for developing climate-resilient crops by enabling simultaneous modification of multiple genes governing complex polygenic traits. Climate change is severely impacting global agriculture through rising temperatures, shifting precipitation patterns, and increased extreme weather events, creating yield gaps that threaten food security [22]. Where conventional breeding struggles to keep pace with rapid climate shifts—particularly for long-generation perennial species—multiplex CRISPR editing allows direct, precise engineering of polygenic trait networks controlling drought tolerance, heat resistance, and climate adaptation [9]. This approach is particularly vital for woody plants and perennial crops with extended juvenile phases, where traditional breeding methods are exceptionally slow [9].

Key Applications and Targets

Drought and Heat Resilience: Engineering climate resilience requires targeting hierarchical gene networks coordinating stress responses. Research in poplar identified overlapping heat- and drought-responsive genes forming coordinated networks, with ERF1 and HSFA2 regulating heat-responsive subnetworks and RD26 and NST1 serving as hub genes for drought response [9]. Multiplex editing enables simultaneous targeting of these interconnected regulators.

Salinity Tolerance: Rewilding approaches reintroduce salt tolerance genes from wild ancestors into domesticated crops using precision breeding tools [22]. Multiplex editing facilitates this process by enabling coordinated changes to multiple salinity response pathways.

Pest and Disease Resistance: For complex disease resistance traits, such as powdery mildew resistance in cucumber, multiplex knockouts of three clade V genes (Csmlo1, Csmlo8, and Csmlo11) were necessary to achieve full resistance, demonstrating the necessity of multi-gene approaches for complete trait engineering [2].

Table 1: Key Gene Targets for Climate Resilience Engineering

| Trait Category | Target Genes/Pathways | Plant System | Engineering Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drought Resilience | ERF1, HSFA2, RD26, NST1 | Poplar [9] | Coordinated stress response network modulation |

| Salinity Tolerance | Wild relative alleles | Various crops [22] | Enhanced salt tolerance through rewilding |

| Disease Resistance | MLO gene family members | Cucumber, barley, wheat [2] | Broad-spectrum powdery mildew resistance |

| Wood Properties | Lignin biosynthesis genes (21 targets) | Poplar [9] | Increased carbohydrate-to-lignin ratio (up to 228%) |

| Forage Quality | COUMARATE 3-HYDROXYLASE (MsC3H) | Alfalfa [9] | Reduced lignin content, improved digestibility |

Experimental Protocol: Multiplex Editing for Drought Resilience

Workflow Overview: The experimental process for engineering drought-resilient crops involves target identification, construct design, plant transformation, and comprehensive phenotypic validation.

Step 1: Target Identification and Prioritization

- Transcriptomic Analysis: Conduct RNA-seq of drought-stressed versus control plants to identify differentially expressed genes. Poplar studies revealed heat- and drought-responsive networks with hierarchical organization [9].

- Network Analysis: Construct co-expression networks to identify hub genes (e.g., ERF1, HSFA2, RD26, NST1) regulating drought response subnets [9].

- Ortholog Identification: Compare candidate genes across species to identify conserved targets for broad applicability.

Step 2: gRNA Design and Validation

- Target Site Selection: Design 20-nt gRNA sequences with high on-target efficiency scores and minimal off-target potential using tools like CRISPR-P or CHOPCHOP.

- Specificity Validation: BLAST gRNA sequences against the host genome to ensure uniqueness, especially for gene family members.

- Promoter Selection: Employ Pol III promoters (U6, U3) for gRNA expression. For complex arrays, utilize tRNA or ribozyme-based processing systems [2].

Step 3: Multiplex Construct Assembly

- Vector System: Use Golden Gate assembly with type IIS restriction enzymes for modular, scalable gRNA integration [4].

- gRNA Array Architecture: Implement polycistronic tRNA-gRNA arrays (PTG) for processing multiple gRNAs from a single Pol II promoter [2].

- Component Configuration: Assemble construct with Cas9 nuclease (Cas12a for AT-rich targets), gRNA array, and plant selection marker.

Step 4: Plant Transformation and Regeneration

- Delivery Method: Use Agrobacterium-mediated transformation for stable integration or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for transgene-free editing.

- Regeneration Protocol: Apply appropriate tissue culture protocols for the target species—critical for perennial woody plants with recalcitrant regeneration systems [9].

- Generation Advancement: Grow T0 plants to maturity and self-pollinate to generate T1 populations for analysis of segregating mutations.

Step 5: Genotyping and Mutation Characterization

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Employ amplicon sequencing (amp-seq) or target capture sequencing to detect mutations across all target sites [2] [9].

- Structural Variant Detection: Use long-read sequencing (Oxford Nanopore, PacBio) to identify large deletions, inversions, or translocations missed by short-read platforms [2].

- Analysis Pipeline: Process sequencing data through customized bioinformatic pipelines to characterize mutation spectra, zygosity, and chimerism.

Step 6: Phenotypic Screening

- Controlled Environment Assays: Evaluate drought tolerance traits under controlled stress conditions: water withholding, osmotic stress assays, and physiological measurements (stomatal conductance, photosynthetic efficiency).

- Biochemical Analysis: Measure stress biomarkers—proline content, antioxidant enzymes, stress hormones—to quantify physiological responses.

- Growth Measurements: Monitor biomass accumulation, root architecture, and water use efficiency as integrative resilience metrics.

Step 7: Field Evaluation and Safety Assessment

- Multi-Location Trials: Assess edited lines across diverse environments to evaluate genotype × environment interactions and trait stability.

- Unintended Effect Screening: Conduct transcriptomic and epigenomic analyses to identify potential off-target effects or unintended consequences of multiplex editing [3].

- Yield Component Analysis: Measure agronomic performance under realistic field conditions to validate practical utility.

Application Note: Multiplex Metabolic Engineering of Plant Specialized Metabolism

Plant specialized metabolism generates a vast array of compounds with significant applications in medicine, agriculture, and industry, but these compounds are often present in trace amounts within complex metabolic cocktails [23]. Metabolic engineering enhances carbon flux toward valuable metabolites, with multiplex genome editing enabling simultaneous optimization of multiple pathway steps. The phenylpropanoid pathway serves as an exemplary case study, producing diverse compounds with roles in plant defense, structural support, and human health applications [23]. Where previous metabolic engineering approaches targeted single enzymes, multiplex editing allows comprehensive pathway rewiring, regulatory network manipulation, and transporter engineering to overcome inherent metabolic bottlenecks.

Key Applications and Targets

Phenylpropanoid Pathway Engineering: This pathway generates flavonoids, lignin, sinapate esters, and other compounds with industrial and nutritional value [23]. Key engineering targets include:

- Entry Point Enzymes: PAL (phenylalanine ammonia-lyase) bridges primary and specialized metabolism, catalyzing the committed step [23].

- Monolignol Pathway: Enzymes including C4H, 4CL, HCT, C3'H, CCoAOMT, F5H, CCR, and CAD constitute the core lignin biosynthesis machinery [23].

- Branch Pathway Regulation: Transcription factors and enzymes controlling flux distribution between competing branches (lignin vs. flavonoids).

Alkaloid and Terpenoid Engineering: Complex medicinal compounds often require extensive pathway manipulation, with multiplex editing enabling coordinated expression of multiple biosynthetic genes.

Table 2: Multiplex Editing Strategies for Metabolic Pathway Engineering

| Pathway Category | Engineering Strategy | Key Targets | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenylpropanoid Diversification | Redirect carbon flux from lignin to valuable co-products | F5H, COMT, CCR [23] | Enhanced production of sinapate esters, flavonoids |

| Lignin Modification | Multi-gene targeting of lignin biosynthesis | 21 lignin genes simultaneously [9] | Improved pulping efficiency, bioenergy processing |

| Alkaloid Production | Regulatory gene manipulation | Transcription factors, pathway genes | Increased medicinal compound yields |

| Membrane Transport | Transporter engineering to reduce feedback inhibition | Vacuolar transporters, ABC transporters | Enhanced metabolite sequestration and accumulation |

Experimental Protocol: Engineering Phenylpropanoid Pathways

Workflow Overview: This protocol details a comprehensive approach to engineering phenylpropanoid metabolism through multiplex editing, from pathway analysis to product validation.

Step 1: Pathway Mapping and Flux Analysis

- Comprehensive Annotation: Identify all genes in the target pathway through genomic and transcriptomic databases. For phenylpropanoids, this includes PAL, C4H, 4CL, and branch-specific enzymes [23].

- Metabolic Flux Analysis: Use isotope labeling (¹³C, ¹⁵N) to quantify carbon partitioning through different pathway branches and identify key regulatory nodes.

- Network Modeling: Construct kinetic models to predict system behavior following genetic perturbations and prioritize engineering targets.

Step 2: Rate-Limiting Step Identification

- Enzyme Activity Profiling: Measure in vitro enzyme activities and in vivo metabolic intermediate accumulation to identify natural bottlenecks.

- Correlation Analysis: Associate transcript levels of pathway genes with end product accumulation across tissues and developmental stages.

- Heterologous Reconstitution: Test pathway segments in microbial systems to identify flux constraints without plant regulatory complexity.

Step 3: Multiplex gRNA Design for Pathway Engineering

- Promoter/Enzyme Engineering: Design gRNAs to modify enzyme coding sequences for altered activity, specificity, or regulation.

- Regulatory Element Targeting: Create gRNAs for modifying transcription factor binding sites or epigenetic marks controlling pathway gene expression.

- Combinatorial Design: Develop gRNA sets targeting different pathway nodes to test synergistic effects and bypass natural regulation.

Step 4: Advanced Construct Assembly

- Modular Vector System: Use Golden Gate or MoClo assembly for combinatorial construction of editing cassettes [4].

- Regulatory Element Integration: Incorporate tissue-specific or inducible promoters for spatiotemporal control of editing.

- Screening Marker Inclusion: Integrate visible markers (GFP, YFP) or selection markers (antibiotic/herbicide resistance) for efficient identification of edited events.

Step 5: Plant Transformation and Selection

- High-Efficiency Transformation: Optimize delivery protocol for target species—critical for species with recalcitrant transformation systems.

- Early Editing Detection: Use PCR-based screening of callus or early regenerants to identify successfully edited lines before plant regeneration.

- Homozygous Line Selection: Advance generations through selfing or accelerated flowering systems to obtain homozygous, transgene-free edited lines.

Step 6: Comprehensive Metabolite Profiling

- Untargeted Metabolomics: Employ LC-MS/MS and GC-MS to profile global metabolic changes resulting from multiplex editing.

- Targeted Quantification: Develop MRM assays for precise quantification of pathway intermediates and end products.

- Spatial Localization: Use imaging mass spectrometry or fluorescent tags to determine subcellular and tissue-level metabolite distribution.

Step 7: Pathway Flux Validation

- Isotopic Tracer Studies: Apply ¹³C-labeled precursors (e.g., ¹³C-phenylalanine) to quantify redirected carbon flux through engineered pathways.

- Enzyme Activity Assays: Measure activities of edited enzymes in crude extracts or purified preparations to confirm functional consequences.

- Systems Analysis: Integrate transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data to build comprehensive models of pathway regulation in edited lines.

Application Note: De Novo Domestication Through Multiplex Genome Editing

De novo domestication uses multiplex genome editing to rapidly introduce domestication traits into wild or semi-wild species, creating new crops with inherent climate resilience and nutritional value [22]. This approach leverages the rich genetic diversity present in wild species that has been lost during historical domestication bottlenecks. With climate change threatening major crops like maize (projected 24% yield decline under high emission scenarios) [22], de novo domestication offers a strategy to develop crops pre-adapted to future conditions. Multiplex editing enables simultaneous installation of multiple domestication syndrome traits—such as reduced shattering, improved architecture, and enhanced yield—in a single transformation event, compressing what historically required millennia into years.

Key Applications and Targets

Domestication Syndrome Engineering: Core domestication traits targeted in wild species include:

- Loss of Seed Shattering: Editing shattering genes (qSH1, SHAT1-5) to prevent seed dispersal [22].

- Plant Architecture: Modifying growth habit, branching patterns, and height for improved harvest index.

- Photoperiod Insensitivity: Editing floral regulators for adaptation to different latitudes and growing seasons.

- Fruit/Seed Size: Targeting genes controlling cell division and expansion in harvested organs.

Resistance Trait Introgression: Wild species often possess climate resilience traits absent from domesticated crops. Multiplex editing facilitates:

- Abiotic Stress Tolerance: Introducing drought, salinity, and extreme temperature tolerance from wild relatives.

- Disease Resistance: Pyramiding multiple resistance genes to create durable, broad-spectrum protection.

- Nutritional Enhancement: Modifying pathways to increase essential nutrients, vitamins, and health-promoting compounds.

Table 3: Domestication Gene Targets for De Novo Domestication

| Domestication Trait | Wild Species Context | Target Genes | Engineering Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced Seed Shattering | Wild grasses, ancestral cereals | qSH1, SHAT1-5 [22] | Knockout of shattering genes |

| Compact Growth Habit | Weedy or sprawling species | Dwarfing genes [22] | Introduction of dwarfing alleles |

| Synchronized flowering | Wild species with irregular flowering | Photoperiod pathway genes | Editing floral regulators |

| Enhanced Yield Components | Low-yielding wild species | Grain number, size regulators | Promoter editing to enhance expression |

| Improved Harvest Index | Wild species with excessive vegetative growth | Sugar partitioning genes | Modifying source-sink relationships |

Experimental Protocol: Multiplex Editing for De Novo Domestication

Workflow Overview: This protocol outlines a systematic approach to de novo domestication, from wild species selection to field evaluation of domesticated lines.

Step 1: Wild Species Selection and Characterization

- Trait Evaluation: Screen wild germplasm for desirable resilience traits (drought, salinity, disease resistance) absent from domesticated crops [22].

- Crossing Compatibility: Assess reproductive compatibility with related domesticated species for potential trait introgression if needed.

- Transformability Assessment: Evaluate tissue culture response and transformation efficiency—critical for applying editing technologies.

Step 2: Genomic Resource Development

- Reference Genome Sequencing: Generate chromosome-level assemblies for target wild species to enable precise gRNA design and off-target prediction.

- Gene Annotation: Annotate domestication gene orthologs through comparative genomics with related domesticated species.

- Transcriptomic Atlas: Profile gene expression across tissues and developmental stages to inform temporal targeting strategies.

Step 3: Domestication Target Identification

- Comparative Genomics: Identify orthologs of known domestication genes from related crops in the wild species genome.

- Allelic Variation Analysis: Sequence target loci across diverse wild accessions to identify pre-existing favorable alleles.

- Gene Function Validation: Use transient expression systems (protoplasts, virus-induced gene silencing) to confirm gene function before stable editing.

Step 4: Multiplex Editing Construct Design

- Trait Pyramid Design: Select 5-10 key domestication targets for simultaneous editing, balancing trait enhancement with potential pleiotropic effects.

- Regulatory Element Engineering: Design edits to modify gene expression patterns rather than complete knockouts where appropriate (e.g., promoter editing).

- Construction Strategy: Use advanced assembly methods (Golden Gate, Gibson assembly) to build complex editing arrays targeting all selected domestication genes [4].

Step 5: Transformation and Regeneration Optimization

- Protocol Development: Establish efficient transformation and regeneration protocols for the wild species—often the major bottleneck.

- Early Detection: Implement PCR-based screening of embryogenic callus to identify editing events before plant regeneration.

- Generation Advancement: Use techniques like early flowering induction or embryo rescue to accelerate generation cycling.

Step 6: Comprehensive Domestication Phenotyping

- Domestication Syndrome Assessment: Systematically evaluate edited lines for key domestication traits: plant architecture, flowering time, seed retention, and yield components.

- Resistance Trait Validation: Confirm retention of desirable wild traits under appropriate stress conditions.

- Pleiotropic Effect Screening: Monitor for potential negative traits linked to domestication genes.

Step 7: Agronomic Evaluation and Safety Assessment

- Field Performance Trials: Evaluate domesticated lines under target production environments for yield, quality, and adaptability.

- Environmental Biosafety Assessment: Study potential ecological impacts, including weediness, cross-compatibility with wild relatives, and ecosystem interactions.

- Food Safety Analysis: For food crops, conduct compositional analysis and toxicity studies to ensure safety of novel products.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multiplex Genome Editing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | Cas9, Cas12a, Cas13, base editors | DNA/RNA targeting with varying PAM requirements | Cas12a preferred for AT-rich genomes; base editors for precise single-base changes |

| gRNA Expression Systems | U6/U3 Pol III promoters; tRNA-gRNA arrays; ribozyme-flanked gRNAs [2] | Multiplex gRNA expression with minimal recombination | tRNA and ribozyme systems enable processing from single transcript |

| Assembly Systems | Golden Gate (Type IIS enzymes); Gibson assembly; Gateway | Modular, scalable construct assembly | Golden Gate enables standardized, high-throughput vector construction |

| Delivery Vehicles | Agrobacterium strains; RNP complexes; viral vectors | DNA/RNA/protein delivery into plant cells | RNPs minimize off-target effects and avoid DNA integration |

| Detection Tools | Amplicon sequencing; T7E1 assay; RFLP analysis; digital PCR | Mutation detection and characterization | Amplicon sequencing provides comprehensive mutation spectra |

| Bioinformatics Tools | CRISPR-P, CHOPCHOP; Cas-OFFinder; CRISPResso2 | gRNA design and mutation analysis | Species-specific tools improve prediction accuracy |

Technical Considerations and Optimization Strategies

Addressing Technical Challenges in Multiplex Editing

Minimizing Unintended Effects: Recent studies indicate that simultaneous editing of multiple loci can induce chromosomal rearrangements, large deletions, translocations, or alterations in epigenetic regulation [3]. A USDA-funded project is systematically investigating these unintended consequences in tomatoes to establish safety thresholds for multiplex editing [3]. Strategies to mitigate these effects include:

- Controlled Editing: Using tissue-specific or inducible promoters to restrict editing to specific developmental stages or tissues.

- Sequential Editing: Implementing multiple rounds of editing with smaller numbers of targets to reduce cellular stress.

- Comprehensive Genotyping: Employing long-read sequencing and optical mapping to detect structural variations missed by standard genotyping.

Optimizing Editing Efficiency: Editing efficiency varies significantly across target sites and species. Improvement strategies include:

- Promoter Engineering: Using engineered promoters with enhanced activity for gRNA expression.

- Cas9 Variants: Employing high-fidelity Cas9 versions to reduce off-target effects while maintaining on-target activity.

- Temperature Optimization: Adjusting growth conditions to enhance editing efficiency in difficult-to-transform species.

Future Directions and Emerging Applications

The field of multiplex genome editing continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging applications poised to expand its utility:

- Chromosomal Engineering: Beyond gene editing, multiplex systems can program large-scale chromosomal rearrangements, including inversions, translocations, and duplications [4].

- Combinatorial Mutagenesis: Systematic knockout of gene family members to decipher functional redundancy and network interactions [2].

- Spatiotemporal Control: Development of inducible and tissue-specific systems for precise control over editing timing and location.

- AI-Enhanced Design: Integration of machine learning and large language models to predict optimal gRNA combinations and editing outcomes [2].

As these tools mature, multiplex genome editing is positioned to become a foundational technology for next-generation crop improvement, enabling researchers to address complex challenges in agriculture, sustainability, and climate resilience with unprecedented precision and efficiency.

CRISPR Toolkits and Implementation Strategies for Effective Multiplexing

Multiplex genome editing (MGE), which enables the simultaneous modification of multiple genomic loci within a single experiment, has dramatically expanded the scope of plant genetic engineering beyond single-gene manipulations [1]. This approach is particularly powerful for addressing polygenic traits, overcoming genetic redundancy in large gene families, and accelerating trait stacking in crop improvement programs [2] [4]. The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) system has emerged as the most versatile platform for MGE due to its simplicity, precision, and scalability [1]. Unlike earlier technologies such as zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), which require complex protein engineering for each new target, CRISPR systems achieve DNA targeting through easily programmable guide RNAs (gRNAs) [4] [1].