Multimodal Sensors in High-Throughput Phenotyping: A New Paradigm for Biomedical and Clinical Research

This article explores the transformative role of multimodal sensor technologies in advancing high-throughput phenotyping for biomedical research and drug development.

Multimodal Sensors in High-Throughput Phenotyping: A New Paradigm for Biomedical and Clinical Research

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of multimodal sensor technologies in advancing high-throughput phenotyping for biomedical research and drug development. It covers the foundational principles of using simultaneous data streams—from wearables, smartphones, and digital platforms—to create comprehensive digital phenotypes. The scope extends to methodological applications in clinical trials, troubleshooting for complex data integration, and comparative validation against traditional measures. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this review synthesizes how these technologies enhance the precision, scalability, and personalization of health monitoring and therapeutic intervention assessment.

The Core Principles and Data Streams of Multimodal Digital Phenotyping

Digital phenotyping is an emerging field that represents a fundamental shift in how researchers and clinicians quantify human health and plant biology. It is formally defined as the moment-by-moment quantification of the individual-level human phenotype using data from personal digital devices such as smartphones and wearables [1] [2]. This approach leverages the ubiquitous nature of digital technology to collect intensive, longitudinal data in naturalistic environments, creating a comprehensive digital footprint of behavior and physiology [3].

The core premise of digital phenotyping lies in its ability to provide unprecedented insights into health-related behaviors and physiological states through continuous monitoring and real-time data analytics. In human applications, this involves collecting active data that requires user engagement (such as completing ecological momentary assessment surveys) and passive data gathered without user participation (such as GPS location, accelerometer readings, and voice analysis) [2]. Similarly, in plant science, high-throughput phenotyping utilizes multimodal sensors to quantitatively measure plant traits across large populations, addressing critical challenges in genetics and breeding programs [4] [5].

The integration of multimodal sensors significantly enhances digital phenotyping by providing complementary data streams that capture different aspects of the phenotype. This multimodal approach allows researchers to develop more comprehensive models of behavior and physiological states, ultimately improving the accuracy and predictive power of digital phenotyping across diverse applications from psychiatry to crop science [6].

Multimodal Sensing Architectures in Digital Phenotyping

Core Sensor Modalities and Data Types

Multimodal sensing architectures form the technological foundation of advanced digital phenotyping systems, integrating diverse sensors to capture complementary aspects of phenotypic expression. The synergy between different sensing modalities enables a more comprehensive understanding of complex traits and behaviors than any single data source could provide independently.

Table 1: Core Sensor Modalities in Digital Phenotyping

| Sensor Modality | Data Types Collected | Applications | Key Measured Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location Sensing | GPS, Bluetooth proximity, Wi-Fi positioning | Mobility patterns, social behavior, environmental context | Location variance, travel distance, social proximity [3] [7] |

| Movement Sensors | Accelerometer, gyroscope, magnetometer | Physical activity, sleep patterns, behavioral states | Step count, gait, activity intensity, sleep-wake cycles [7] [2] |

| Physiological Monitors | Heart rate sensors, photoplethysmography, electrodermal activity | Stress response, arousal states, cardiovascular health | Heart rate variability, pulse rate, galvanic skin response [1] [2] |

| Image Sensors | RGB, thermal, hyperspectral, depth imaging | Plant morphology, disease detection, human facial expression | Canopy structure, temperature variation, spectral signatures [8] [9] [5] |

| Audio Sensors | Microphone, speech analysis | Social engagement, mood states, cognitive function | Speech patterns, tone, frequency, conversation duration [2] |

| Environmental Sensors | Temperature, humidity, light, air quality | Contextual analysis, environmental triggers | Ambient conditions, environmental exposures [9] [10] |

Sensor Integration Architectures

Effective multimodal digital phenotyping requires sophisticated architectures for sensor integration and data fusion. Two predominant architectural paradigms have emerged: centralized mobile platforms that leverage smartphones and wearables for human phenotyping, and dedicated sensor arrays for plant phenotyping applications.

In human digital phenotyping, smartphones serve as the primary hub for data collection, coordinating inputs from built-in sensors (GPS, accelerometer, microphone) and external wearables (heart rate monitors, smartwatches) [7] [1]. The Beiwe platform exemplifies this approach, simultaneously collecting GPS data, accelerometer readings, and self-reported ecological momentary assessment (EMA) surveys through a smartphone application [7]. This architecture enables both active and passive data collection in natural environments, capturing moment-by-minute behavioral and physiological data.

For plant phenotyping, specialized ground vehicles and aerial platforms integrate multiple imaging sensors for high-throughput field assessment. The GPhenoVision system represents an advanced implementation, incorporating RGB-D, thermal, and hyperspectral cameras mounted on a high-clearance tractor [9]. This multi-sensor approach enables comprehensive canopy characterization, capturing morphological, physiological, and pathological traits simultaneously. Similarly, research by Bai et al. demonstrated the integration of ultrasonic sensors, thermal infrared radiometers, NDVI sensors, spectrometers, and RGB cameras on a single field platform for simultaneous phenotyping of soybean and wheat [10].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Digital Phenotyping Platforms

| Platform | Sensor Complement | Data Fusion Approach | Primary Application Domain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beiwe Platform | Smartphone sensors (GPS, accelerometer), EMA surveys | Temporal synchronization of active and passive data streams | Human epidemiological cohorts, mental health monitoring [7] |

| GPhenoVision | RGB-D camera, thermal imager, hyperspectral camera, RTK-GPS | Geo-referenced multimodal image registration | Field-based high-throughput plant phenotyping [9] |

| Multi-Sensor Field System | Ultrasonic sensors, thermal IR, NDVI, spectrometers, RGB cameras | Synchronized data collection with environmental monitoring | Soybean and wheat breeding programs [10] |

| M2F-Net | RGB imaging, agrometeorological sensors | Deep learning-based multimodal fusion | Identification of fertilizer overuse in crops [6] |

| Phenotyping Robot | RGB-D camera, multi-spectral sensors, environmental sensors | Real-time sensor data registration and fusion | Crop ground phenotyping in dry and paddy fields [8] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol Design for Human Digital Phenotyping

Implementing robust digital phenotyping studies requires meticulous protocol design to ensure data quality, participant compliance, and scientific validity. The Nurses' Health Study II provides a exemplary framework for smartphone-based digital phenotyping implementation [7]. This protocol employed an 8-day intensive measurement burst using the Beiwe smartphone application, incorporating:

- Baseline Assessment: Comprehensive initial survey covering demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, and dispositional traits using validated instruments such as the Life Orientation Test-Revised for optimism [7].

- Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA): Twice-daily surveys (early afternoon and evening) administered through smartphone notifications, assessing current psychological states using modified versions of standardized instruments like the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-Expanded Form (PANAS-X) [7].

- Passive Sensing: Continuous collection of minute-level accelerometer data (at 10 Hz every 30 seconds for 10 consecutive seconds) and GPS data (every 15 minutes for 90 consecutive seconds) to capture movement patterns and location variance [7].

- Technical Support Infrastructure: Dedicated research assistants providing telephone and email support throughout the study period to address technical issues and maintain participant engagement [7].

- Data Quality Monitoring: Real-time tracking of survey completion rates and passive data completeness to identify compliance issues promptly [7].

This protocol demonstrated modest but acceptable compliance rates in an older cohort (57-75 years), with average daily EMA response rates of 55.6% for early afternoon surveys and 54.7% for evening surveys, and passive data completeness of 62.0% for accelerometer data and 57.7% for GPS data [7]. The findings highlight the importance of balancing data collection intensity with participant burden, particularly in studies extending beyond brief assessment periods.

Field-Based High-Throughput Plant Phenotyping Protocols

Field-based high-throughput plant phenotyping requires specialized protocols to handle environmental variability, large sample sizes, and complex sensor integration. The GPhenoVision system protocol exemplifies a comprehensive approach to multimodal plant phenotyping [9]:

- Platform Configuration: A high-clearance tractor equipped with an adjustable sensor frame (height range: 1.2-2.4 meters) and environmental enclosure to minimize ambient interference from factors such as direct sunlight and wind [9].

- Multimodal Sensor Synchronization: Coordinated data collection from RGB-D (6 FPS), thermal (6 FPS), and hyperspectral (100 FPS) cameras, all triggered by GPS position to ensure precise geo-referencing of all measurements [9].

- Environmental Monitoring: Concurrent measurement of ambient conditions (air temperature, relative humidity, pressure) using auxiliary sensors to contextualize phenotypic measurements [9].

- Data Processing Pipeline: Automated extraction of canopy-level phenotypes including height, width, projected leaf area, volume from RGB-D data, and temperature metrics from thermal images [9].

- Validation Procedures: Correlation of sensor-derived measurements with manual ground truthing and handheld instrument readings to ensure measurement accuracy (r² > 0.90 between gimbal data and handheld instruments) [8].

This protocol enabled the quantification of growth rates for morphological traits and demonstrated strong correlations with fiber yield (r = 0.54-0.74) and good broad-sense heritability (H² = 0.27-0.72), validating its utility for genetic analysis and breeding programs [9].

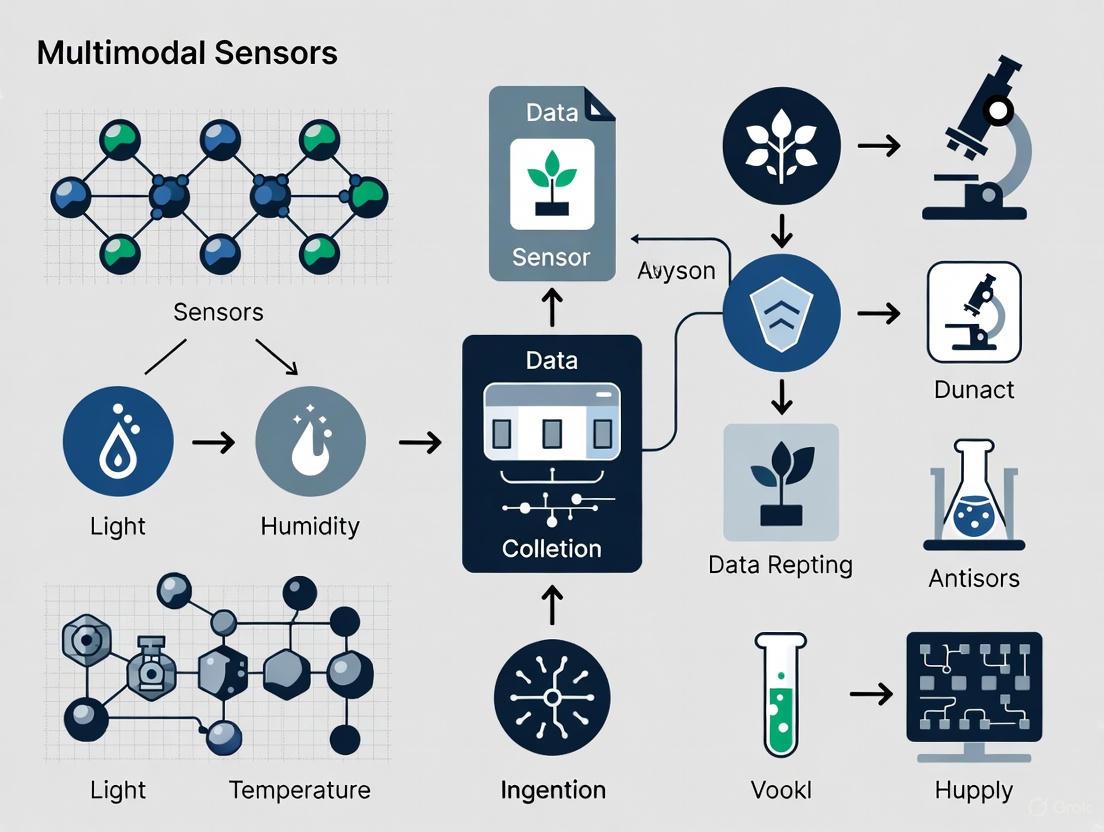

Diagram 1: Experimental workflows for human and plant digital phenotyping protocols

Data Analytics and Computational Approaches

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Frameworks

The volume, velocity, and variety of data generated by multimodal digital phenotyping necessitate advanced computational approaches for meaningful analysis. Machine learning and deep learning frameworks have emerged as essential tools for extracting patterns and predictive signals from these complex datasets [4].

In human digital phenotyping, machine learning algorithms process high-dimensional data from multiple sensors to identify behavioral markers associated with health outcomes. For example, in mental health applications, ML models can detect subtle patterns in mobility, sociability, and communication that precede clinical relapse events [3] [2]. One pilot study with individuals with schizophrenia demonstrated that relapse events could be predicted by anomalies in passive data streams, with a 71% higher rate of anomalies detected two weeks prior to relapse compared to baseline periods [3].

For plant phenotyping, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have revolutionized the analysis of multimodal imaging data. The M2F-Net framework exemplifies advanced deep learning applications, implementing three multimodal fusion strategies to combine agrometeorological data with plant images for identifying fertilizer overuse [6]. This approach achieved 91% classification accuracy, significantly outperforming unimodal models trained solely on image or sensor data [6]. The superior performance demonstrates the critical advantage of multimodal data fusion for complex phenotypic classification tasks.

Multimodal Data Fusion Strategies

Effective integration of heterogeneous data streams represents both a challenge and opportunity in digital phenotyping. Three primary fusion strategies have emerged across applications:

- Early Fusion: Combining raw data from multiple sensors before feature extraction, requiring precise temporal alignment but preserving potentially informative interactions between data modalities [6].

- Intermediate Fusion: Extracting features from each modality separately then combining them in shared hidden layers of neural networks, balancing modality-specific processing with integrated representation learning [6].

- Late Fusion: Processing each data stream through separate models and combining predictions at the decision level, allowing for heterogeneous processing pipelines while leveraging complementary information [6].

The choice of fusion strategy depends on data characteristics and research objectives. Intermediate fusion has shown particular promise in applications requiring complex pattern recognition across heterogeneous data types, as demonstrated by the M2F-Net framework for fertilizer overuse identification [6].

Technical Challenges and Standardization Strategies

Despite its considerable promise, digital phenotyping faces significant technical challenges that must be addressed to realize its full potential. Key limitations include:

- Battery Life Constraints: Continuous sensor data collection consumes substantial power, with smartphones experiencing rapid battery drainage (5.5-6 hours at 1Hz sampling) [1]. Location services alone can consume 13-38% of battery capacity, depending on signal strength [1].

- Data Heterogeneity: Inconsistencies across devices, operating systems, and sensor specifications create interoperability challenges and limit data standardization [1].

- Analytical Complexity: The "volume, variety, and velocity" of digital phenotyping data outpace traditional statistical methods, requiring specialized machine learning approaches [3].

- Participant Compliance: User fatigue, particularly with frequent EMA surveys, can reduce data completeness over time [7].

Standardization strategies are emerging to address these challenges:

- Adaptive Sampling: Dynamically adjusting sensor sampling frequencies based on activity levels to optimize power consumption [1].

- Cross-Platform Frameworks: Developing open-source APIs and software development kits (SDKs) to enhance interoperability across devices and operating systems [1].

- Advanced Analytical Methods: Applying anomaly detection algorithms and time-varying effect models specifically designed for intensive longitudinal data [3].

- Participant-Centered Design: Optimizing survey frequency and passive data collection protocols to balance data richness with participant burden [7].

Implementing robust digital phenotyping research requires access to specialized tools, platforms, and analytical resources. The following table summarizes key components of the digital phenotyping research toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Digital Phenotyping

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection Platforms | Beiwe, Apple ResearchKit, AWARE Framework | Smartphone-based active and passive data collection | Large-scale epidemiological cohorts, mental health monitoring [7] |

| Multimodal Sensing Systems | GPhenoVision, Phenotyping Robots, Custom Sensor Arrays | High-throughput field-based phenotyping | Crop genetic improvement, breeding programs [8] [9] [10] |

| Sensor Technologies | RGB-D Cameras (Microsoft Kinect), Thermal Imagers (FLIR), Hyperspectral Cameras | Capture morphological, thermal, and spectral plant traits | Canopy structure analysis, stress detection, yield prediction [9] [5] |

| Positioning Systems | Real-Time Kinematic GPS (Raven Cruizer II) | Precise geo-referencing of field measurements | Spatial phenotyping, plot-level trait mapping [9] |

| Data Analysis Frameworks | M2F-Net, CNN Architectures (DenseNet-121), Random Forests | Multimodal data fusion, feature extraction, classification | Fertilizer overuse identification, disease detection [4] [6] |

| Validation Instruments | Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R), PANAS-X, Handheld Spectrometers | Ground truth measurement for algorithm validation | Psychological assessment, sensor data calibration [7] [10] |

Digital phenotyping represents a paradigm shift in how researchers quantify complex phenotypes across human and plant domains. By leveraging multimodal sensor data, this approach enables the moment-by-moment assessment of behavior and physiological states in naturalistic environments, providing unprecedented resolution for understanding phenotype-environment interactions. The integration of diverse data streams—from smartphone sensors and wearable devices in human applications to multimodal imaging systems in plant science—creates rich phenotypic fingerprints that offer new insights for healthcare and agricultural innovation.

Despite significant challenges related to data heterogeneity, analytical complexity, and participant engagement, ongoing advancements in sensor technology, machine learning, and standardization protocols are rapidly addressing these limitations. As digital phenotyping methodologies mature, they hold tremendous promise for enabling personalized interventions in healthcare and accelerating genetic gain in crop improvement, ultimately contributing to enhanced human health and global food security.

High-throughput phenotyping research is undergoing a transformative shift with the integration of multimodal sensor data. The convergence of behavioral, physiological, psychological, and social data modalities creates a comprehensive digital fingerprint of human health and functioning, enabling unprecedented precision in research and clinical applications [11]. This multimodal approach leverages continuous, real-time data collection from personal digital devices such as smartphones and wearables to capture the moment-by-moment quantification of individual-level human phenotype [12]. By moving beyond single-domain assessments, researchers can now decode complex patterns and interactions across domains, offering particular promise for mental health care, chronic disease management, and pharmaceutical development where early intervention can dramatically improve outcomes [12] [11].

The technical foundation of this revolution rests on sophisticated sensor technologies embedded in consumer and specialized medical devices. These include accelerometers, GPS sensors, heart rate monitors, microphone and speech analysis capabilities, and sophisticated algorithms for analyzing social and phone usage patterns [12] [13]. When strategically combined within integrated systems often called "smart packages" - typically comprising a smartphone paired with wearable devices like Actiwatches, smart bands, or smartwatches - these sensors provide complementary data streams that capture the dynamic interplay between different aspects of human functioning [13]. This whitepaper provides a technical examination of the four core data modalities, their measurement methodologies, and their integrated application in advancing high-throughput phenotyping research.

Core Data Modalities and Their Technical Specifications

Behavioral Phenotyping

Behavioral phenotyping involves the passive monitoring and quantification of an individual's daily activities, movements, and device interactions [11]. This modality provides objective markers of functional capacity, daily routine structure, and behavioral activation levels that are particularly valuable in mental health and neurological disorders research.

Key Measurable Features:

- Physical Activity: Step count, movement intensity, exercise patterns

- Sleep Patterns: Sleep duration, sleep-wake cycles, rest-activity rhythms

- Device Usage: Screen time, app usage patterns, typing dynamics

- Mobility: Location tracking, travel patterns, circadian movement

Physiological Phenotyping

Physiological phenotyping captures data from an individual's autonomic and central nervous system functions, providing objective biomarkers of health status and disease progression [11]. This modality offers crucial insights into bodily responses to stressors, medications, and environmental factors.

Key Measurable Features:

- Cardiovascular Function: Heart rate, heart rate variability, blood pressure

- Electrodermal Activity: Skin conductance, galvanic skin response

- Metabolic Indicators: Blood glucose, skin temperature, respiratory rate

- Neurophysiological Signals: EEG, EMG (via specialized wearables)

Psychological Phenotyping

Psychological phenotyping focuses on capturing data related to emotional states, cognitive functions, and subjective experiences [11]. This modality bridges the gap between objective behavioral measures and internal psychological experiences, enabling research into mood disorders, cognitive decline, and treatment response.

Key Measurable Features:

- Emotional State: Voice sentiment analysis, facial expression recognition

- Cognitive Function: Reaction time, processing speed, working memory tasks

- Subjective Experience: Ecological momentary assessments, self-reported mood

- Clinical Symptoms: Depression and anxiety indicators from language patterns

Social Phenotyping

Social phenotyping quantifies an individual's social engagement patterns and communication behaviors [11]. This modality provides crucial context for understanding how social connectedness and interaction patterns influence health outcomes across psychiatric and neurological conditions.

Key Measurable Features:

- Social Engagement: Call logs, text message frequency, social media activity

- Communication Patterns: Conversation dynamics, vocal features during social interaction

- Social Rhythm: Regularity of social contact, size of social network

- Language Analysis: Vocabulary complexity, sentiment in written communication

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Core Digital Phenotyping Modalities

| Data Modality | Primary Sensors | Sample Metrics | Collection Methods | Data Output Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral | Accelerometer, GPS, Gyroscope, Light Sensor | Step count, sleep duration, travel distance, phone usage time | Passive sensing via smartphones and wearables | Time-series activity data, location coordinates, usage logs |

| Physiological | PPG sensor, EDA sensor, Thermometer, ECG | Heart rate, HRV, skin conductance, skin temperature, blood pressure | Smartwatches, chest straps, specialized patches | Waveform data, summary statistics, event markers |

| Psychological | Microphone, Touchscreen, Camera, EMA apps | Voice sentiment, self-reported mood, reaction time, facial expressivity | Active tasks, voice samples, ecological momentary assessment | Audio features, self-report scores, performance metrics |

| Social | Bluetooth, Microphone, Communication apps | Call frequency, social media use, conversation duration, message volume | Communication logs, speech analysis during calls | Interaction logs, language features, social network maps |

Quantitative Feature Importance Across Devices

The relative importance and measurement reliability of phenotyping features varies significantly across different wearable devices, reflecting their distinct hardware capabilities and design purposes. Systematic analysis reveals device-specific patterns in feature effectiveness for predicting mental health conditions like depression and anxiety.

Table 2: Feature Importance and Coverage Across Wearable Device Types

| Feature | Actiwatch | Smart Bands | Smartwatches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerometer | High importance, Wide coverage | Moderate importance, Wide coverage | Wide coverage, Lower importance |

| Heart Rate | Not available | High importance, Wide coverage | High importance, Wide coverage |

| Sleep Metrics | Lower coverage, Moderate importance | High importance, Wide coverage | High importance, Wide coverage |

| Step Count | Not available | High importance, Wide coverage | Wide coverage, Lower importance |

| Phone Usage | Not available | High importance, Moderate coverage | Moderate coverage, Variable importance |

| GPS | Not available | High importance when used | Variable importance, Technical limitations |

| Electrodermal Activity | Not available | High importance when used | Limited availability, Emerging use |

| Skin Temperature | Not available | High importance when used | Limited availability, Emerging use |

Research indicates that a core feature package comprising accelerometer, steps, heart rate, and sleep consistently contributes to mood disorder prediction across devices [13]. However, device-specific analyses reveal important nuances: Actiwatch studies primarily emphasize accelerometer and activity metrics but underutilize sleep features; smart bands effectively leverage HR, steps, sleep, and phone usage; while smartwatches most reliably utilize sleep and HR data [13]. Features like electrodermal activity, skin temperature, and GPS show high predictive importance when used but have lower adoption rates, suggesting opportunities for broader implementation in future devices [13].

Experimental Protocols for Multimodal Data Collection

Protocol 1: Multimodal Clinical Interaction Study

The MePheSTO study protocol exemplifies rigorous multimodal phenotyping in clinical psychiatric populations, specifically targeting major depressive episodes and schizophrenia [14].

Study Design:

- Participants: 450 participants (150 per site), ideally split between MDE (75) and schizophrenia (75) patients

- Duration: Main study phase with 12-month follow-up period

- Setting: Multicenter prospective observational study across clinical sites

- Data Collection Points: Minimum of four clinical interactions per participant recorded multimodally

Methodological Details:

- Recording Modalities: Video, audio, and physiological sensors during patient-clinician interactions

- Follow-up Phase: Videoconference-based recordings and ecological momentary assessments over 12 months

- Digital Phenotyping Targets:

- Alogia and thought poverty: Quantified via speech amount, average pause length, lack of articulation, average response length

- Anhedonia and affective flattening: Detected by facial and body movement reduction, vocal monotony

- Social withdrawal: Measured through reduced verbal engagement, increased physical distance

- Avolition: Identified via reduced gesture frequency, slower movement initiation

This protocol aims to acquire a multimodal dataset of patient-clinician interactions, annotated and clinically labelled for scientifically sound validation of digital phenotypes for psychiatric disorders [14]. The target sample size of 450 participants represents a significant increase beyond existing corpora, addressing the critical need for larger datasets in digital phenotyping research.

Protocol 2: Multimodal Opioid Use Disorder Monitoring

This protocol demonstrates implementation of multimodal digital phenotyping in substance use disorder populations, specifically patients receiving buprenorphine for opioid use disorder [15].

Study Parameters:

- Participants: 65 patients receiving buprenorphine for OUD

- Duration: 12-week monitoring period

- Data Sources: Ecological momentary assessment (EMA), sensor data, and social media data

- Collection Devices: Smartphone, smartwatch, and social media platforms

Engagement Metrics and Outcomes:

- Phone Carry Criteria: ≥8 hours per day (participants met criteria on 94% of study days)

- Watch Wear Criteria: ≥18 hours per day (participants met criteria on 74% of days)

- Sleep Monitoring: Watch worn during sleep (77% of days)

- EMA Response Rates: Mean rate of 70%, declining from 83% (week 1) to 56% (week 12)

- Social Media Consent: 88% consent rate among account holders

This study demonstrates generally high engagement with multiple digital phenotyping data sources in a clinical OUD population, though with more limited engagement for social media data [15]. The findings provide important feasibility data for implementing multimodal phenotyping in challenging clinical populations.

Technical Implementation and Workflow Integration

The integration of multimodal sensor data requires sophisticated technical infrastructure and standardized workflows to ensure data reliability, interoperability, and scalability. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for multimodal data acquisition, processing, and analysis in high-throughput phenotyping research:

Diagram 1: Multimodal Phenotyping Workflow

Technical Infrastructure Requirements

Implementing robust multimodal phenotyping requires addressing several technical challenges:

Battery Life and Power Management:

- Challenge: Continuous sensor operation causes significant battery drain, with smartphones lasting approximately 5.5-6 hours during continuous sensing at 1Hz refresh rate [12]

- Solutions: Adaptive sampling (dynamically adjusting sensor frequency based on activity), sensor duty cycling (alternating between low-power and high-power sensors), and low-power wearable devices with energy-efficient chipsets [12]

Device Compatibility and Data Integration:

- Challenge: Heterogeneity of devices and operating systems creates inconsistencies in data collection [12]

- Solutions: Native app development for optimized performance, cross-platform frameworks (React Native, Flutter), standardized APIs (Apple HealthKit, Google Fit), and open-source frameworks for data integration [12]

Data Processing and Storage:

- Challenge: Multimodal phenotyping generates massive datasets requiring specialized management

- Solutions: Cloud-based storage solutions, dedicated data management platforms, and automated data validation pipelines [16]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Technical Solutions for Digital Phenotyping

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Technical Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wearable Devices | Actiwatch, Fitbit Charge 5, Polar H10 chest strap, Empatica E4 | Capture physiological (HR, HRV, EDA) and behavioral (movement, sleep) data | Continuous monitoring in naturalistic settings; long-term longitudinal studies |

| Mobile Sensing Platforms | Beiwe, AWARE Framework, StudentLife | Passive smartphone data collection (GPS, usage, communication) | Real-world behavior tracking; ecological momentary assessment delivery |

| Data Integration APIs | Apple HealthKit, Google Fit, Open mHealth | Standardized data aggregation from multiple sources | Cross-platform data interoperability; centralized data storage |

| Multimodal Analysis Tools | BioSignalML, OpenFace, Praat | Specialized analysis of physiological signals, facial expression, vocal features | Feature extraction from raw sensor data; behavioral coding |

| Clinical Assessment Integration | PHQ-9, GAD-7, PANSS digitized versions | Digital administration of validated clinical scales | Ground truth establishment; model validation against clinical standards |

The strategic integration of behavioral, physiological, psychological, and social data modalities represents a paradigm shift in high-throughput phenotyping research. By leveraging complementary data streams from multimodal sensors, researchers can develop more comprehensive digital phenotypes that capture the complex, dynamic interplay between different aspects of human functioning. This approach shows particular promise for mental health research, where it enables detection of subtle changes that were previously difficult to detect, prediction of symptom exacerbation, and support for personalized interventions [12] [11].

Technical implementation requires careful attention to device selection, power management, data integration, and analytical methodologies. The core feature package of accelerometer, steps, heart rate, and sleep provides a foundation for mood disorder prediction, while device-specific optimization enhances data quality [13]. Future advancements will depend on improved standardization, battery efficiency, interoperability solutions, and ethical frameworks that balance technological innovation with privacy protection [12]. As these technical challenges are addressed, multimodal digital phenotyping is poised to become an increasingly powerful tool for transforming research and clinical practice across psychiatric, neurological, and chronic disease domains.

High-throughput phenotyping (HTP) research represents a transformative approach in biomedical and agricultural sciences, enabling the large-scale, precise measurement of physiological and behavioral traits. Central to this paradigm is the strategic integration of multimodal sensor data collected through both active and passive methodologies. The emergence of digital phenotyping—defined as the "moment-by-moment quantification of the individual-level human phenotype in situ using data from personal digital devices" [17]—has created new opportunities for understanding disease trajectories and health-related behaviors. However, this approach introduces a fundamental tension: the scientific need for comprehensive data collection must be carefully balanced against the practical burden placed on study participants [18]. This technical guide examines the core principles, methodologies, and practical implementations of active versus passive data collection frameworks within multimodal sensor-based research, providing researchers with evidence-based strategies for optimizing this critical balance.

Modern phenotyping research utilizes a diverse ecosystem of sensing technologies, including smartphones, wearables, ground-based robotic systems, and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) [4] [19] [20]. These platforms generate massive datasets that, when effectively integrated and analyzed, can reveal previously unattainable insights into complex biological phenomena. The transition from traditional, low-throughput phenotyping to automated HTP has been accelerated by concurrent advances in sensor technology, data analytics, and robotic platforms [19]. Within this technological landscape, understanding the relative strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications of active versus passive data collection is paramount for designing methodologically rigorous and practically feasible research studies.

Defining Active and Passive Data Collection

Core Concepts and Distinctions

In multimodal sensing research, data collection strategies fall into two primary categories based on the level of participant involvement required:

Active Data Collection: This approach requires deliberate participant engagement to generate data points. In clinical and research settings, this typically involves Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA), where participants complete subjective measures related to their symptoms, behaviors, or experiences in real-time within their natural environments [18]. Active data collection provides rich, contextualized information but introduces challenges related to participant compliance and burden.

Passive Data Collection: This methodology operates without requiring explicit participant involvement, continuously gathering objective data through embedded sensors in devices such as smartphones, wearables, or environmental monitors [18]. Examples include GPS tracking, accelerometer data, communication logs, and device usage patterns [21] [22]. While passive sensing generates substantial datasets with minimal participant effort, it may lack contextual depth and faces challenges regarding data consistency and privacy [18].

Comparative Analysis: Advantages and Limitations

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Active and Passive Data Collection Methods

| Characteristic | Active Data Collection | Passive Data Collection |

|---|---|---|

| Participant Burden | High (requires direct engagement) | Low (minimal participant awareness) |

| Data Volume | Lower (limited by compliance) | Higher (continuous sampling) |

| Contextual Depth | Rich subjective context | Limited without complementary active data |

| Compliance Issues | Significant challenge [18] | Minimal for data collection itself |

| Data Consistency | Variable (dependent on prompt response) | Platform-dependent variability [21] |

| Primary Strengths | Subjective experience, ground truth | Objective behavioral metrics, longitudinal patterns |

| Typical Technologies | EMA surveys, self-report instruments | Smartphone sensors, wearables, environmental sensors |

Multimodal Sensing in High-Throughput Phenotyping

The Multimodal Sensor Ecosystem

High-throughput phenotyping leverages diverse sensing technologies deployed across multiple platforms to capture comprehensive phenotypic profiles:

Ground-Based Imaging Systems: These include tractor-mounted, gantry, or robotic systems equipped with RGB cameras, multispectral/hyperspectral sensors, LiDAR, and time-of-flight cameras for detailed plant characterization [23] [19] [20]. For instance, the PlantScreen Robotic XYZ System has been successfully deployed for analyzing drought tolerance traits in rice [4].

Aerial Phenotyping Platforms: Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UASs) equipped with various sensors enable scalable field phenotyping, with SfM-MVS (Structure from Motion and Multi-View Stereo) and LiDAR technologies dramatically improving the efficiency of canopy height estimation and biomass assessment [19].

Personal Digital Devices: Smartphones and wearables contain multiple sensors (accelerometers, gyroscopes, GPS, microphones) that enable digital phenotyping of health behaviors in free-living environments [21] [17] [22]. These devices facilitate the collection of real-world data (RWD) that complements traditional clinical assessments.

Sensor Integration and Data Fusion

The effective utilization of cross-modal patterns depends on sophisticated image registration and data fusion techniques. A novel multimodal 3D image registration method that integrates depth information from a time-of-flight camera has demonstrated robust alignment across different plant types and camera compositions [23]. Similarly, research in mental health digital phenotyping has employed multimodal sensing of multiple situations of interest (e.g., sleep, physical activity, mobility) to develop comprehensive behavioral markers [17].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Multimodal Phenotyping

| Technology Category | Specific Solutions | Primary Functions | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging Sensors | RGB cameras, Multispectral/hyperspectral cameras, Thermal cameras | Capture spectral signatures, canopy temperature, morphological traits | Canopy coverage estimation, stress detection [19] |

| 3D Reconstruction Systems | LiDAR, Time-of-flight cameras, SfM-MVS | Create 3D models of plant architecture | Canopy height estimation, biomass prediction [19] |

| Inertial Measurement Units | Accelerometers, Gyroscopes | Quantify movement patterns, physical activity | Human activity recognition, gait analysis [21] |

| Location Tracking | GPS, Wi-Fi positioning systems | Monitor mobility patterns, location variance | Depression symptom association [22] |

| Environmental Sensors | Field Server, IoT environmental sensors | Monitor ambient conditions (temperature, humidity, light) | G×E (genotype and environment) interaction studies [19] |

| Software Platforms | EasyPCC, LemnaTec systems | Automated image analysis, data processing | High-throughput canopy coverage analysis [19] |

Quantitative Assessment of Data Collection Methodologies

Performance Metrics in Passive Sensing

Recent large-scale studies have revealed significant variations in passive data quality across different sensing platforms. A comprehensive analysis of smartphone sensor data from 3,000 participants found considerable variation in sensor data quality within and across Android and iOS devices [21]. Specifically, iOS devices showed significantly lower levels of anomalous point density (APD) compared to Android across all sensors (p < 1 × 10^−4), and iOS devices demonstrated a considerably lower missing data ratio (MDR) for the accelerometer compared to GPS data (p < 1 × 10^−4) [21]. Notably, the quality features derived from raw sensor data across devices alone could predict the device type (Android vs. iOS) with up to 0.98 accuracy (95% CI [0.977, 0.982]) [21], highlighting the substantial platform-specific biases that can confound phenotypic inferences.

Compliance Metrics in Active Data Collection

Research on active data collection methodologies has identified significant challenges in participant compliance. A scoping review of 77 mobile sensing studies found that participant compliance in active data collection remains a major barrier, with considerable variability in completion rates for ecological momentary assessments [18]. Similarly, a multimodal digital phenotyping study in patients with major depressive episodes found that high dropout rates for longer study periods remain a challenge, limiting the generalizability of findings despite the potential of these methodologies [22].

Experimental Protocols for Integrated Data Collection

Protocol 1: Multimodal Digital Phenotyping for Mental Health

The Mobile Monitoring of Mood (MoMo-Mood) study implemented a comprehensive protocol for assessing mood disorders using integrated active and passive data collection [22]:

Participant Cohorts: Recruitment of 188 participants across 3 subcohorts of patients with major depressive episodes (major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, or concurrent borderline personality disorder) and a healthy control group.

Phase 1 (Initial 2 weeks): Collection of multimodal data including:

- Active Data: Five sets of daily questions completed by participants

- Passive Data: Bed sensors, actigraphy, and smartphone sensors (GPS, communication logs, device usage)

Phase 2 (Extended phase, up to 1 year)

- Passive Monitoring: Continuous smartphone data collection

- Active Assessments: Biweekly Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) assessments

Analytical Framework

- Statistical Analysis: Survival analysis for adherence, statistical tests for group differences

- Feature Extraction: Location variance, normalized entropy of location, temporal communication patterns

- Model Development: Linear mixed models to associate behavioral features with depression severity

This protocol demonstrated that the duration of incoming calls (β = -0.08, 95% CI -0.12 to -0.04; P < 0.001) and the standard deviation of activity magnitude (β = -2.05, 95% CI -4.18 to -0.20; P = 0.02) were negatively associated with depression severity, while the duration of outgoing calls showed a positive association (β = 0.05, 95% CI 0.00-0.09; P = 0.02) [22].

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Field Phenotyping Using Robotic Systems

A recently developed phenotyping robot exemplifies the integration of multiple imaging sensors for agricultural field phenotyping [8]:

Platform Design: Gantry-style chassis with adjustable wheel track (1400-1600 mm) to adapt to different row spacing arrangements, functioning effectively in both dry field and paddy field environments.

Sensor Gimbal System: Six-degree-of-freedom sensor gimbal with high payload capacity enabling precise height (1016-2096 mm) and angle adjustments.

Data Acquisition and Fusion

- Sensor Registration: Implementation of Zhang's calibration and feature point extraction algorithm

- Homography Matrix Calculation: For high-throughput data collection at fixed positions and heights

- Performance Validation: Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of the registration algorithm not exceeding 3 pixels, with gimbal data strongly correlating with handheld instrument data (r² > 0.90)

This system enables the collection of multimodal image data (RGB, hyperspectral, thermal) that can be coregistered and fused for comprehensive plant trait analysis [8].

Workflow Visualization: Integrated Active-Passive Sensing

Integrated Active-Passive Data Collection Workflow

Optimization Strategies for Balancing User Burden and Data Quality

Mitigating Active Data Collection Burden

Intelligent Prompting Systems: Machine learning techniques can reduce participant burden in active data collection by optimizing prompt timing, auto-filling responses, and minimizing prompt frequency based on individual patterns and contextual factors [18].

Simplified Interfaces: User-friendly interfaces, particularly for smartwatch prompts and mobile applications, can significantly improve compliance rates by reducing interaction complexity and time requirements [18].

Adaptive Assessment Protocols: Implementing algorithms that dynamically adjust questioning frequency and complexity based on participant engagement levels and symptom severity can maintain data quality while minimizing burden [18].

Enhancing Passive Data Quality and Consistency

Platform-Specific Optimization: Given the significant differences in data quality between mobile platforms (Android vs. iOS), researchers should implement platform-specific sampling strategies and quality adjustment methods to ensure consistent data collection across heterogeneous devices [21].

Battery Life Management: Techniques such as optimization of recording times, strategic sensor scheduling, and adaptive sampling rates can preserve device battery life while maintaining data integrity [18].

Motivational Engagement: Implementing appropriate motivational techniques, including feedback mechanisms and engagement prompts, can encourage proper device use and maintenance, thereby increasing data consistency [18].

The integration of active and passive data collection methodologies within multimodal sensor frameworks represents a powerful approach for high-throughput phenotyping across diverse research domains. The strategic balance between these approaches—leveraging the contextual richness of active assessments and the continuous objective monitoring of passive sensing—enables researchers to develop comprehensive digital behavioral signatures that may be linked to health outcomes in real-world settings [21] [17]. As the field advances, key challenges remain in standardizing data quality across platforms, maintaining participant engagement in long-term studies, and developing analytical frameworks that can effectively integrate multimodal data streams while accounting for platform-specific variations and biases.

Future research directions should focus on the development of more adaptive hybrid frameworks that dynamically adjust the balance between active and passive data collection based on individual participant characteristics, research needs, and contextual factors. Additionally, advancing cross-platform standardization and addressing the technological and methodological rigor issues identified in current studies will be crucial for translating these promising methodologies into real clinical and agricultural applications [17] [18]. Through continued refinement of these approaches, researchers can maximize the potential of multimodal phenotyping while minimizing participant burden, ultimately driving innovation in both biomedical and agricultural sciences.

The paradigm of healthcare is undergoing a radical transformation, shifting from a primarily reactive, curative model to one that is Predictive, Preventive, Personalized, and Participatory—the core principles of P4 medicine [24] [25] [26]. This new approach conceptualizes a health care model based on multidimensional data and machine-learning algorithms to develop public health interventions and monitor population health status with a focus on wellbeing and healthy aging [24]. In this framework, the "patient" is redefined; they may be healthy at the time of assessment but potentially ill in the future, necessitating a dynamic conception of health states [25]. P4 medicine represents the application of systems biology to medical practice, aiming to treat not only symptoms but also underlying causes of disease with greater emphasis on prevention and promoting overall balance [25] [26].

High-throughput phenotyping serves as the critical technological enabler for P4 medicine, providing the comprehensive, dynamic data required to realize its core principles. Phenotyping is defined as the comprehensive assessment of complex traits, including development, growth, resistance, tolerance, physiology, architecture, yield, and ecology [4]. The emergence of multimodal sensor systems has revolutionized our ability to capture these traits at unprecedented scale and resolution. By leveraging advanced sensing technologies and artificial intelligence, modern phenotyping generates the extensive, multidimensional data clouds that form the foundation of P4 medicine [4] [9] [11]. These data clouds, comprising molecular, cellular, organ, phenotypic, imaging, and social network information, enable the characterization of an individual's "network of networks" in both normal and disease-perturbed states, providing deep insights into disease mechanisms and new approaches to diagnostics and therapeutics [26].

The P4 Framework Deconstructed: How Phenotyping Drives Each Component

Predictive Medicine: From Reaction to Anticipation

Predictive medicine focuses on the early identification of potential diseases through comprehensive analysis of large-scale individual data [24] [11]. Phenotyping enables prediction by facilitating continuous health monitoring and identification of subtle patterns that precede clinical manifestations. Digital phenotyping, which utilizes smart devices, sensors, and mobile apps to continuously collect data on behavior, psychology, and physiology, provides a powerful tool for identifying early signs and risks of diseases [11]. For example, research has demonstrated that smartphone-based digital phenotyping can detect changes in usage patterns, sleep quality, and social behavior that may signal the onset of mental health issues like depression or anxiety [11]. By dynamically monitoring these behavioral biomarkers, healthcare providers can transition from reactive treatment to proactive risk management.

The predictive capability of phenotyping extends across multiple domains, as illustrated in Table 1, which summarizes key applications, technologies, and experimental findings.

Table 1: Predictive Capabilities Enabled by Advanced Phenotyping Technologies

| Application Domain | Phenotyping Technology | Predictive Capability | Experimental Correlation/Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health | Smartphone-based digital phenotyping [11] | Early identification of schizophrenia onset through usage pattern analysis | Strong association with clinical outcome assessments [11] |

| Infectious Disease | AI-driven migration maps, contact tracing [24] | Forecasting regional transmission dynamics of COVID-19 | Enabled aggressive containment strategies in South Korea (mortality: 6/100k vs. USA: 231/100k) [24] |

| Crop Disease | Multimodal imaging (RGB, thermal, hyperspectral) [9] | Early detection of plant stress before visual symptoms | Strong correlations (r = 0.54-0.74) between traits and yield [9] |

| Chronic Disease | Wearable sensors, continuous physiological monitoring [11] | Prediction of cardiovascular events through activity and heart rate patterns | Enabled early intervention for high-risk individuals [11] |

Preventive Medicine: Intercepting Disease Progression

Preventive medicine emphasizes the core role of dietary changes, lifestyle modifications, and other factors in health management and disease prevention [24] [11]. The extensive and continuous data collection capabilities of digital phenotyping provide a solid foundation for disease prevention strategies. For instance, randomized controlled trials have explored the impact of exercise on diabetic patients using smartphone personal health record applications, demonstrating that digital phenotyping technologies can help improve diabetes-related indices such as HbA1c and fasting blood glucose [11]. Furthermore, dynamic monitoring of chronic conditions like obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases has shown that digital phenotyping can enhance disease-related indices through lifestyle interventions targeting exercise and diet [11].

The transition from prediction to prevention requires robust experimental protocols that can identify effective interventions. The following protocol exemplifies how phenotyping enables preventive medicine:

Protocol Title: Multimodal Sensor-Based Intervention for Metabolic Syndrome Prevention

- Participant Selection: Recruit adults with at least two risk factors for metabolic syndrome (elevated blood glucose, hypertension, dyslipidemia, or central obesity)

- Baseline Assessment:

- Collect multimodal phenotypic data: continuous glucose monitoring, physical activity tracking, sleep monitoring, dietary logging

- Perform laboratory assessments: HbA1c, lipid profile, inflammatory markers

- Conduct physical examination: BMI, waist circumference, blood pressure

- Intervention Phase (12-week randomized controlled trial):

- Experimental Group: Receive personalized feedback based on real-time phenotyping data with automated alerts for behavioral deviations

- Control Group: Receive standard lifestyle recommendations without continuous monitoring

- Data Integration:

- Fuse multimodal data streams using sensor fusion algorithms

- Apply machine learning to identify patterns associated with improvement

- Outcome Measures:

- Primary: Change in HbA1c and metabolic syndrome severity score

- Secondary: Adherence to intervention, quality of life measures

This systematic approach to prevention, enabled by comprehensive phenotyping, allows for early intervention before disease manifestations become irreversible.

Personalized Medicine: From Population Averages to Individual Specificity

Personalized medicine represents a fundamental shift from the one-size-fits-all approach to healthcare, instead focusing on individual characteristics such as genetic and epigenetic profiles, lifestyle factors, and environmental exposures [25] [11]. Phenotyping enables this personalization through deep phenotyping approaches that capture the unique biological and behavioral characteristics of each individual. Research has revealed significant heterogeneity in subphenotypic characteristics, medication adherence, and optimal drug dosages among patients with the same disease diagnosis [11]. For example, studies utilizing smartphones and specialized applications have demonstrated the potential of digital phenotyping in assessing phenotypic diversity and patient heterogeneity in conditions like dry eye disease, showing strong patient stratification capabilities [11].

The power of personalized approaches is particularly evident in oncology, where 70% of compounds developed are now precision medicines that target specific genetic and biochemical characteristics of individual tumors [25]. This personalization is made possible by sophisticated phenotyping technologies that can identify subtle variations between patients who might otherwise be grouped under the same diagnostic category. The integration of multimodal data sources creates a comprehensive health profile for each individual, enabling truly personalized treatment strategies.

Table 2: Multimodal Sensors for Personalized Health Profiling

| Sensor Modality | Measured Parameters | Personalization Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| RGB-D Camera [9] | Canopy height, width, projected leaf area, volume [9] | Plant-specific growth monitoring | Kinect v2, 6 FPS, global shutter [9] |

| Thermal Imaging [9] | Canopy temperature, stress response | Irrigation optimization based on plant water status | FLIR A655sc, 6 FPS [9] |

| Hyperspectral Imaging [9] | Spectral signatures, biochemical composition | Nutrient deficiency detection | Middleton MRC-923-001, 100 FPS [9] |

| Wearable ECG [11] | Heart rate variability, arrhythmias | Personalized stress management | Continuous monitoring, real-time alerts [11] |

| Smartphone Usage Tracking [11] | Keystroke dynamics, social engagement | Mental health assessment and intervention | Passive data collection, pattern analysis [11] |

Participatory Medicine: Engaging Patients as Active Partners

Participatory medicine completes the P4 framework by transforming patients from passive recipients of care into active participants in their health journey [24] [25] [26]. This element emphasizes that each individual is responsible for optimizing their health and engages patients, physicians, healthcare workers, and other stakeholders in a collaborative healthcare ecosystem [24] [26]. Phenotyping technologies enable participation by providing individuals with accessible data about their health status and behaviors. Patient-activated social networks, such as "quantified self" communities where individuals use digital devices to measure physical parameters like weight, pulse, respiration, sleep quality, and stress, represent powerful examples of participatory medicine in action [26].

The implementation of participatory medicine faces several societal challenges, including ethical, legal, privacy, and regulatory considerations [26]. Additionally, education and consumer feedback mechanisms must be developed to bring appropriate understanding of P4 medicine to all participants in the healthcare system [26]. A proposed solution involves creating a new healthcare professional role—the healthcare and wellness coach—who can interpret patient data clouds and present them in ways that encourage patients to use their data for health improvement [26]. Information technology infrastructure must also evolve to support participatory medicine, including trusted third-party sites with accurate information and platforms for managing personal data clouds [26].

Multimodal Sensor Technologies for High-Throughput Phenotyping

Sensor Modalities and Their Applications

The advancement of P4 medicine relies critically on sophisticated sensor technologies that enable comprehensive phenotyping across multiple dimensions. These technologies can be categorized based on their operating principles and the type of information they capture:

Imaging Sensors provide visual and spatial information about physiological structures and functions. Examples include:

- RGB Imaging: Conventional color imaging for morphological assessment [9] [5]

- Thermal Imaging: Infrared radiation detection for temperature mapping and stress response [9]

- Hyperspectral Imaging: High spectral resolution sensors for biochemical composition analysis [9]

- RGB-D Cameras: Combined color and depth sensing for three-dimensional characterization [9]

Physiological Sensors capture continuous data on bodily functions:

- Heart Rate Monitors: Track cardiovascular function and stress responses [11]

- Activity Sensors: Accelerometers and gyroscopes for movement quantification [11]

- Glucose Monitors: Continuous measurement of blood glucose levels [11]

Environmental Sensors contextualize health data by measuring external factors:

- Air Quality Sensors: Monitor pollutants and allergens [11]

- Temperature and Humidity Sensors: Track microclimate conditions [9]

- GPS: Location tracking for exposure assessment and activity patterns [11]

Behavioral Sensors capture patterns in daily activities and interactions:

- Smartphone Usage Trackers: Monitor screen time, application usage, and keystroke dynamics [11]

- Social Interaction Sensors: Analyze communication patterns and social engagement [11]

- Sleep Monitors: Track sleep duration, quality, and disturbances [11]

Sensor Fusion and Data Integration

The true power of multimodal phenotyping emerges through sensor fusion—the integration of data from multiple sources to create a comprehensive health profile. Research has demonstrated that fusion strategies significantly outperform unimodal approaches. For example, a study on fertilizer overabundance identification in Amaranthus crops achieved 91% accuracy by fusing agrometeorological data with images, substantially outperforming models using either data type alone [6].

Three primary fusion strategies have been identified for integrating multimodal phenotyping data:

Early Fusion: Raw data from multiple sensors are combined before feature extraction, requiring temporal and spatial alignment but preserving potentially informative correlations between modalities [6].

Intermediate Fusion: Features are extracted from each modality separately then combined before classification, allowing for modality-specific processing while enabling the model to learn cross-modal relationships [6].

Late Fusion: Decisions from unimodal classifiers are combined at the prediction level, offering flexibility in model architecture but potentially missing low-level interactions between modalities [6].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for multimodal data fusion in high-throughput phenotyping:

Diagram: Multimodal phenotyping data fusion workflow for P4 medicine applications

Experimental Protocols for High-Throughput Phenotyping in P4 Medicine

Protocol for Digital Phenotyping in Mental Health

Title: Smartphone-Based Digital Phenotyping for Early Detection of Mental Health Disorders

Participant Recruitment and Consent

- Recruit participants from high-risk populations or general community

- Obtain informed consent detailing data collection scope and privacy protections

- Install dedicated research application on participants' smartphones

Data Collection Parameters

- Passive Data: GPS location, accelerometer data, call and message logs (metadata only), screen on/off events, app usage patterns

- Active Data: Weekly ecological momentary assessments (EMAs) for mood and anxiety, cognitive tasks for executive function assessment

- Temporal Pattern: Continuous passive monitoring with daily active assessments for 12-week study period

Feature Extraction

- Social Behavior: Number of calls/texts, entropy of communication patterns, circadian rhythm of social activity

- Mobility: Location variance, number of significant locations, routine regularity

- Sleep: Sleep duration, sleep onset and wake times, sleep regularity

- Cognition: Reaction time, task accuracy, performance variability

Validation Methodology

- Compare digital phenotyping features with clinical assessments (PHQ-9, GAD-7) at baseline, 4, 8, and 12 weeks

- Use machine learning models (Random Forest, SVM) to classify mental health states

- Assess predictive validity for clinical outcomes using time-to-event analysis

This protocol exemplifies how comprehensive phenotyping can capture subtle behavioral changes that precede clinical diagnosis, enabling earlier intervention and personalized treatment approaches.

Protocol for Multimodal Crop Phenotyping with Agricultural Implications for Human Health

Title: High-Throughput Field Phenotyping for Nutrient Content and Stress Resilience

Experimental Design

- Randomized complete block design with multiple genotypes and treatment conditions

- Plot size and replication determined based on phenotyping platform specifications and expected effect sizes

Sensor System Configuration

- Platform: High-clearance tractor with adjustable sensor gimbal (height range: 1016-2096 mm) [9]

- RGB-D Camera: Microsoft Kinect v2, 6 FPS, global shutter [9]

- Thermal Camera: FLIR A655sc, 6 FPS [9]

- Hyperspectral Camera: Middleton MRC-923-001, 100 FPS [9]

- Environmental Sensors: Air temperature, relative humidity, pressure (BME280 sensor) [9]

- Positioning: Real-time kinematic GPS for geo-referencing [9]

Data Collection Protocol

- Regular intervals throughout growth cycle (weekly during vegetative stage, bi-weekly during reproductive stage)

- Consistent time of day (10:00-14:00) to minimize diurnal variation effects

- Multiple positions per plot to account for spatial heterogeneity

Phenotype Extraction Pipeline

Data Integration and Analysis

- Multi-sensor data fusion using registration algorithms (RMSE < 3 pixels) [9]

- Correlation analysis between sensor-derived traits and yield/quality measures

- Genome-wide association studies using phenotyping data for gene discovery

This agricultural phenotyping protocol demonstrates principles directly transferable to human health applications, particularly in nutritional science and environmental health.

Data Analysis: Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Approaches

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Frameworks

The massive datasets generated by high-throughput phenotyping platforms necessitate advanced AI approaches for meaningful analysis. Machine learning provides a multidisciplinary framework that relies on probability, decision theories, visualization, and optimization to handle large amounts of data effectively [4]. These approaches allow researchers to search massive datasets to discover patterns by concurrently examining combinations of traits rather than analyzing each feature separately [4].

Deep learning has emerged as a particularly powerful subset of machine learning that incorporates benefits of both advanced computing power and massive datasets, allowing for hierarchical data learning [4]. Importantly, deep learning bypasses the need for manual feature engineering, as features are learned automatically from the data [4]. Key deep learning architectures include:

- Multilayer Perceptron (MLP): Feedforward neural networks for structured data analysis [4] [6]

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN): Specialized for image processing and feature extraction [4]

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN): Designed for sequential data and temporal patterns [4]

- Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN): Useful for data augmentation and synthetic data generation [4]

M2F-Net: A Case Study in Multimodal Fusion

The M2F-Net framework exemplifies the power of multimodal deep learning for phenotyping applications [6]. This network was specifically designed to identify overabundance of fertilizers in Amaranthus crops by fusing agrometeorological data with images [6]. The framework developed and analyzed three fusion strategies, assessing integration at various stages:

Baseline Unimodal Networks: A Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) was trained on agrometeorological data, while a pre-trained Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model (DenseNet-121) was trained on image data [6].

Multimodal Fusion: The fusion network capable of learning from both image and non-image data significantly outperformed unimodal approaches, achieving 91% accuracy in identifying fertilizer overuse [6].

This case study demonstrates that incorporating multiple data modalities can substantially boost classification performance, a finding with direct relevance to human health applications where multiple data streams are increasingly available.

Table 3: AI Approaches for Phenotyping Data Analysis

| AI Method | Best Suited Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest [4] | Trait segmentation, feature importance | Handles high-dimensional data, provides feature rankings | Limited capacity for automatic feature learning |

| Support Vector Machines [4] | Classification tasks with clear margins | Effective in high-dimensional spaces, memory efficient | Doesn't directly provide probability estimates |

| Convolutional Neural Networks [4] [6] | Image-based phenotyping, pattern recognition | Automatic feature extraction, state-of-the-art performance | Computationally intensive, requires large datasets |

| Multilayer Perceptron [4] [6] | Structured data fusion, classification | Flexible architecture, handles mixed data types | Prone to overfitting without proper regularization |

| Recurrent Neural Networks [4] | Temporal data analysis, growth modeling | Captures time-dependent patterns | Computationally complex, challenging to train |

Implementation Challenges and Future Directions

Technical and Analytical Challenges

The implementation of high-throughput phenotyping in P4 medicine faces several significant technical challenges:

Data Management and Integration: The massive volumes of data generated by multimodal sensors present substantial storage and processing challenges [9]. A single phenotyping platform can generate terabytes of data in a single growing season, requiring sophisticated data management strategies [9]. Additionally, integrating heterogeneous data types (images, sensor readings, genomic data) requires advanced data fusion algorithms and standardization protocols [6].

Signal-to-Noise Issues: Big data in healthcare is characterized by significant signal-to-noise challenges [26]. Biological variability, measurement error, and environmental influences can obscure meaningful patterns, requiring advanced statistical approaches and validation frameworks to distinguish true signals from noise [26].

Algorithm Development: Creating robust, generalizable AI models requires addressing issues of overfitting, data bias, and model interpretability [4]. Many deep learning models function as "black boxes," making it difficult to understand the basis for their predictions, which poses challenges for clinical adoption [4].

Ethical and Societal Considerations

The widespread implementation of phenotyping for P4 medicine raises important ethical and societal questions:

Privacy and Data Security: Continuous monitoring generates sensitive health and behavioral data that requires robust privacy protections [11] [26]. Questions about data ownership, appropriate use, and protection from unauthorized access must be addressed through comprehensive security frameworks and clear policies [26].

Equity and Access: Digital phenotyping technologies may not be equally available and affordable to all population groups, potentially exacerbating healthcare disparities [24] [26]. Older adults, people living in isolated settings, and economically disadvantaged populations risk being excluded from the benefits of P4 medicine if technologies are not designed with inclusivity in mind [24].

Regulatory and Validation Standards: As phenotyping technologies move from research to clinical applications, establishing rigorous validation standards and regulatory pathways becomes essential [26]. Demonstrating clinical utility, analytical validity, and economic value will be necessary for widespread adoption in healthcare systems [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies for High-Throughput Phenotyping

| Item | Function | Example Applications | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multimodal Sensor Arrays [9] [10] | Simultaneous capture of diverse phenotypic traits | Canopy architecture, temperature, spectral signatures | Requires synchronization and calibration across modalities |

| RTK-GPS [9] | High-precision geo-referencing of sensor data | Spatial mapping of phenotypic variation | Centimeter-level accuracy for plot-level analysis |

| Environmental Sensors [9] [10] | Contextual data on growing conditions | Air temperature, humidity, solar radiation | Necessary for normalizing phenotypic measurements |

| Data Fusion Algorithms [6] | Integration of multimodal data streams | Feature-level and decision-level fusion | Critical for leveraging complementary data sources |

| Deep Learning Frameworks [4] [6] | Automated analysis of complex phenotypic data | Image classification, temporal pattern recognition | Require substantial computational resources and expertise |

| Cloud Computing Infrastructure [26] | Storage and processing of large datasets | Management of "data clouds" for individual patients | Essential for handling petabyte-scale phenotypic data |

High-throughput phenotyping, powered by multimodal sensor technologies and artificial intelligence, serves as the fundamental enabler of the P4 medicine paradigm. By generating comprehensive, dynamic data clouds at individual and population levels, advanced phenotyping provides the necessary infrastructure for predictive risk assessment, preventive intervention, personalized treatment, and participatory healthcare. The convergence of technological advancements in sensing, computing, and analytics has created unprecedented opportunities to transform healthcare from a reactive system focused on disease to a proactive system optimized for wellness.

The full realization of P4 medicine will require addressing significant technical challenges in data management and analysis, as well as navigating complex ethical considerations around privacy, equity, and regulation. Furthermore, successful implementation will depend on developing new healthcare models, including potentially new professional roles such as health and wellness coaches who can help individuals interpret and act upon their phenotypic data [26]. As these challenges are addressed, phenotyping-driven P4 medicine promises to revolutionize healthcare by enabling earlier interventions, more targeted treatments, and greater patient engagement, ultimately leading to improved health outcomes and enhanced quality of life across populations.

The transformation of precision medicine from concept to clinical reality hinges upon our ability to decipher the complex relationship between genetic blueprint and observable traits. Phenomics, the large-scale, systematic study of an organism's complete set of phenotypes, has emerged as the critical bridge across this genotype-phenotype divide. By leveraging high-throughput technologies, multimodal sensor data, and artificial intelligence, phenomics captures the dynamic expression of traits in response to genetic makeup, environmental influences, and their interactions. This technical examination explores the infrastructural frameworks, computational methodologies, and translational applications through which phenomics is accelerating the development of personalized therapeutic strategies, ultimately enabling a more precise, predictive, and preventive paradigm in patient care.

A fundamental challenge in modern biomedical research lies in the imperfect correlation between genomic information and clinical outcomes. While genomic sequencing has become highly accessible, our ability to predict disease susceptibility, drug response, and health trajectories from DNA sequences alone remains limited. This discrepancy arises because phenotypes manifest through complex, dynamic interactions between genotypes and environmental factors, many of which are not fully captured by traditional research approaches.

Phenomics addresses this gap through systematic, large-scale phenotyping that captures the multidimensional nature of human biology and disease. The "phenome" represents the complete set of phenotypes expressed by an organism throughout its lifetime, encompassing molecular, cellular, physiological, and behavioral traits. By applying high-throughput technologies, standardized methodologies, and computational analytics, phenomics provides the essential data layer needed to correlate genomic variation with its functional manifestations across diverse biological contexts [27].

In precision medicine, this approach enables a shift from static genetic profiling to dynamic functional assessment, offering unprecedented opportunities for understanding disease mechanisms, predicting therapeutic efficacy, and preventing adverse drug reactions. This whitepaper examines the technological infrastructure, analytical frameworks, and clinical implementations through which phenomics is bridging the genotype-phenotype gap to advance personalized healthcare.

Phenomics Foundations: Core Concepts and Definitions

Conceptual Framework

Phenomics operates on the principle that comprehensive phenotypic characterization is essential for understanding biological function and dysfunction. Unlike traditional phenotyping which often focuses on single traits or disease-specific markers, phenomics employs systematic, unbiased approaches to capture phenotypic complexity at multiple biological scales:

- Molecular phenotypes: Protein expression, metabolite concentrations, epigenetic modifications

- Cellular phenotypes: Morphology, proliferation, apoptosis, organelle function

- Tissue/organ phenotypes: Structure, function, integration

- Organism-level phenotypes: Clinical signs, symptoms, behaviors

- Dynamic phenotypes: Responses to perturbations, temporal patterns

This multidimensional perspective is particularly valuable for precision medicine, where individual variations in drug response often arise from complex interactions across these biological scales rather than single genetic determinants [28].