Multimodal Sensor Fusion for Early Drought Stress Detection: Performance Evaluation and Advanced Monitoring Frameworks

Early detection of drought stress is critical for mitigating its impact on plant health and agricultural productivity.

Multimodal Sensor Fusion for Early Drought Stress Detection: Performance Evaluation and Advanced Monitoring Frameworks

Abstract

Early detection of drought stress is critical for mitigating its impact on plant health and agricultural productivity. This article provides a comprehensive performance evaluation of multiple sensing technologies for identifying water deficit conditions before visible symptoms occur. It explores foundational principles of plant stress responses, details methodological applications of sensor fusion and machine learning, addresses key challenges in sensor optimization and data integrity, and presents rigorous validation protocols for comparative analysis. Designed for researchers and scientists, this review synthesizes current advancements and practical frameworks to guide the development of robust, early-warning drought monitoring systems.

Understanding Plant Stress and Sensor Fundamentals for Early Drought Detection

Plant stress responses unfold across a spectrum of scales, initiating with non-visible cellular alarms and progressing to visible morphological changes. As climate change increases the frequency and intensity of both abiotic and biotic stresses, the ability to detect these responses early and accurately has become critical for safeguarding global food security [1] [2]. Stressful environments trigger a cascade of plant reactions, beginning at the cellular and subcellular levels—often invisible to the naked eye—and eventually manifesting as discoloration, morphological changes, and disease symptoms at the whole-plant level [1]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of current methodologies for detecting both visible and non-visible stress responses, with particular emphasis on their applications in early drought stress detection research.

The Anatomy of Plant Stress: From Alarm to Resistance

Plants respond to stress exposure through three fundamental, sequential phases [1] [2]. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each phase.

Table: Phases of Plant Stress Response

| Phase | Timeline | Key Events | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alarm Phase | Immediate to hours | Activation of cellular processes (Ca²⁺ signaling, ROS production), initial gene expression changes [1] | Molecular bioassays, transcriptomics [1] |

| Acclimation Phase | Hours to days | Production of stress-responsive proteins and metabolites, physiological adjustments [1] | Metabolomics, proteomics, chlorophyll fluorescence [1] [3] |

| Resistance Phase | Days to weeks | Full establishment of stress phenotype, morphological changes [1] | Remote sensing, imaging, visual assessment [1] [4] |

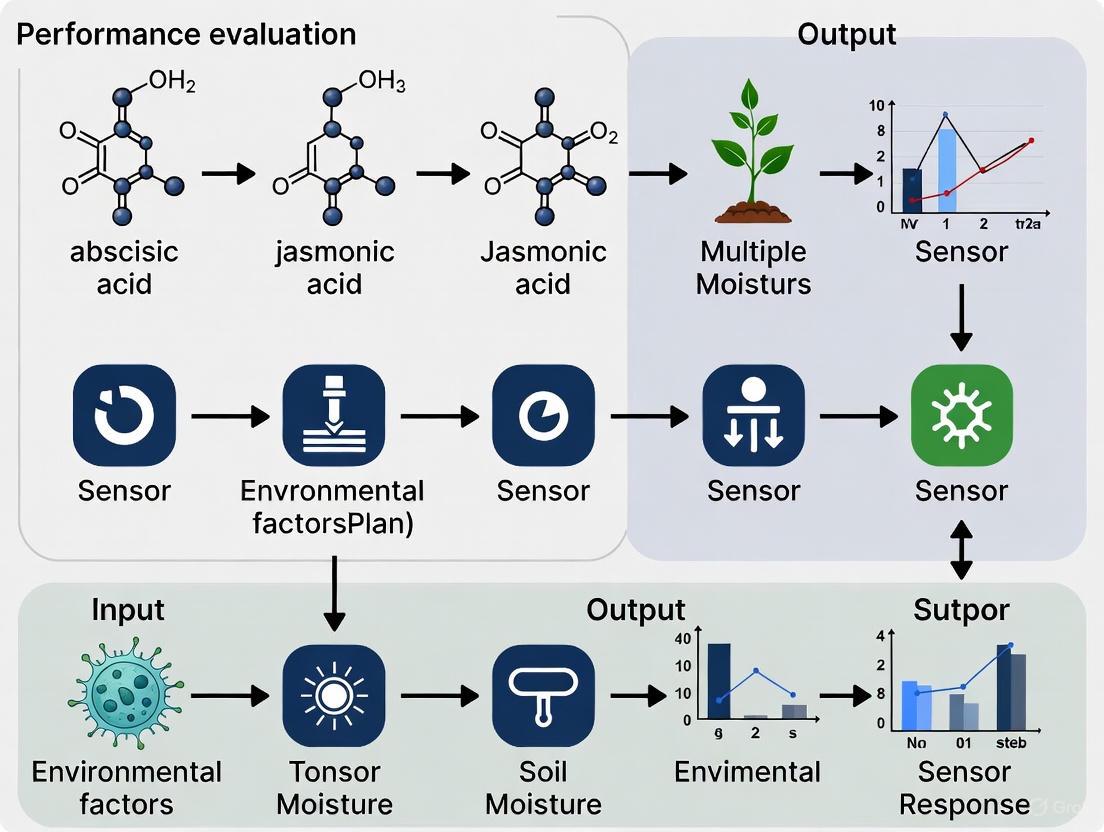

The following diagram illustrates the logical progression through these stress response phases and the corresponding detection technologies at each stage.

Detection of Non-Visible Stress Responses

Non-visible plant stress responses encompass cellular and subcellular changes that can serve as early indicators of stress before visible symptoms appear [1].

Molecular and Biochemical Assays

Biological assays provide precise detection of specific stress-related molecules and compounds. Following stress exposure, plants exhibit molecular changes including fluctuations in intracellular Ca²⁺ concentrations and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, which initiate the alarm phase of the stress response [1] [2].

Chemiluminescence-based bioassays provide a simple approach for quantifying Ca²⁺ and ROS levels by measuring light emission from targeted chemical reactions. These assays have been used to monitor intracellular Ca²⁺ changes in response to stressors such as nitrate and heat [1]. However, these assays typically require destructive sampling, limiting their application for time-series studies unless multiple samples are collected [1].

Fluorescence-based bioassays utilize high-energy photon absorption and subsequent low-energy emission to track plant responses non-destructively. Chlorophyll fluorescence imaging has been widely applied to assess abiotic stress impacts, including nutrient deficiency, heat stress, and drought [1]. Under stress, alterations in photosystem II (PSII) efficiency can be quantified using the Fv/Fm ratio, which reflects the maximum quantum yield of PSII photochemistry. Declines in Fv/Fm indicate stress-induced photoinhibition and often correlate with oxidative stress, nutrient imbalances, or water deficiency [1].

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) use antigen-antibody interactions to detect and quantify pathogens and stress-related hormones. ELISA has become a common method for studying plant viral infections and has been used to measure heat shock proteins, which play a crucial role in activating multimodal stress-response gene expression [1] [2].

Omics Technologies for Comprehensive Stress Profiling

Large-scale omic approaches enable comprehensive characterization of molecular and biochemical stress profiles in plants, providing valuable insights into plant responses to abiotic and biotic stressors [1].

Ionomics involves the study of an organism's elemental composition and nutrient dynamics. Nutrient imbalances—whether deficiencies or toxicities—can serve as abiotic stressors, disrupting plant growth and physiological function [1]. Mass spectrometry (MS) techniques have been applied to analyze elemental distributions in plants under stress, such as measuring nutrient levels in cotton seedlings exposed to salt stress [2].

Metabolomics focuses on small-molecule metabolites that function as intermediates and end products of cellular processes. Metabolomic profiling can reveal plant-produced metabolites that mediate stress responses, as well as toxic metabolites synthesized by pathogens and pests [1]. Liquid chromatography-MS (LC-MS) is preferred for studying organic compounds as this method maintains molecular integrity by dissolving compounds in an organic solvent and water mixture before ionization [2].

Proteomics involves the large-scale study of proteins, encompassing their abundance, modifications, and interactions. Protein compositions dynamically shift in response to stress, making proteomic profiling a crucial tool for understanding functional responses at different stress stages [1].

Genomic and Transcriptomic Biomarkers

Transcriptome analysis enables detailed investigation of the complex molecular mechanisms underlying drought-stress responses, which are often challenging to fully comprehend solely through morphological phenotyping [5].

Recent research has identified drought-stress biomarker (DSBM) genes in rice that consistently respond to drought stress. A study using time-series RNA-seq of the drought-susceptible rice cultivar IR64 revealed drastic changes in the transcriptome after 4-6 days of drought treatment, particularly for genes related to photosynthesis [5]. Among differentially expressed genes, researchers selected 23 DSBM genes that consistently responded to drought stress. Rehydration immediately reset the changes in expression of these DSBM genes, indicating that their expression changes reflect current drought-stress perception levels rather than stress memories [5].

A machine learning model developed using the expression levels of DSBM genes successfully predicted the drought-stress perception levels of various rice accessions, representing the probability of exposure to drought treatment, with an accuracy of 75% [5].

Table: Comparison of Non-Visible Stress Detection Methods

| Method | Target | Sensitivity | Time Requirement | Cost | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Assays | Specific molecules (Ca²⁺, ROS, pathogens) | High (detects low concentrations) | Hours | Low to moderate | Pathogen detection, signaling studies [1] |

| Chlorophyll Fluorescence | PSII efficiency | Moderate | Minutes to hours | Moderate | Photosynthetic performance, abiotic stress [1] [6] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Elements, metabolites, proteins | Very high | Days | High | Ionomics, metabolomics, proteomics [1] [2] |

| Transcriptomics | Gene expression | High | Days | High | Biomarker identification, pathway analysis [5] |

Detection of Visible Stress Responses

Visible stress responses manifest at the organ, plant, and canopy levels as discoloration, morphological changes, and disease symptoms. These can be monitored efficiently through atmospheric, aerial, and terrestrial remote sensing platforms [1].

Spectral Sensing Technologies

Spectral sensing technologies detect changes in plant physiology and biochemistry by measuring how plant tissues absorb, reflect, or transmit light across various wavelength bands [6].

Visible and Infrared Spectroscopy can detect stress-induced changes in leaf pigments, anatomy, and biochemistry. Water absorbs light in the infrared region, and this interaction is used in water stress indices to determine leaf water content [6]. Cell wall elasticity changes and, in some cases, cuticle thickness increases due to drought stress also alter leaf reflectance. The precise wavelengths for drought detection differ among species—500-850 nm for maize, 430-890 nm for barley, and 400-980 nm for tomato [6].

Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) captures reflectance across hundreds of narrow bands in the visible, near-infrared (NIR), and short-wave infrared (SWIR) regions, enabling detection of early stress-induced changes in plant physiology [7]. Stress-related alterations such as reductions in leaf water content, pigment degradation, and changes in canopy structure correlate with spectral variations, particularly in the SWIR region [7].

Thermal Imaging detects changes in canopy temperature that may indicate stress. When pathogens like bacteria or viruses enter the stomata, leaves recognize microbe-associated molecular patterns and reduce stomatal conductance. As transpiration regulates leaf temperature, closing stomata increases leaf temperature, which infrared wavelengths can detect [6].

Vegetation Indices and Machine Learning Approaches

Vegetation indices derived from spectral data provide quantitative measures of plant health and stress status.

Traditional vegetation indices such as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) have been widely used for vegetation monitoring but have limited effectiveness in detecting early stress conditions due to their reliance on broad spectral bands [7]. Recent advancements have focused on developing more stress-specific indices:

Machine Learning-Based Vegetation Index (MLVI) and Hyperspectral Vegetation Stress Index (H_VSI) are novel hyperspectral indices that leverage critical spectral bands in the Near-Infrared (NIR), Shortwave Infrared 1 (SWIR1), and Shortwave Infrared 2 (SWIR2) regions. These indices are optimized using Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and have demonstrated the ability to detect stress 10-15 days earlier than conventional indices while exhibiting a strong correlation with ground-truth stress markers (r = 0.98) [7].

When these indices serve as inputs to a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model for stress classification, they can achieve a classification accuracy of 83.40% in distinguishing six levels of crop stress severity [7].

Experimental Protocol: Early Stress Detection Using Spectroscopy and Machine Learning

The following workflow details a representative experimental approach for early stress detection using in vivo spectroscopy and machine learning, based on a study investigating different stress types in apple trees [3].

1. Plant Material and Stress Application

- Select uniform healthy plants (e.g., apple trees, Malus x domestica Borkh.)

- Apply controlled stress treatments: biotic stress (e.g., apple scab), abiotic stresses (e.g., waterlogging, herbicides)

- Maintain control plants under optimal conditions

- Ensure appropriate replication (e.g., 15 trees per treatment)

2. Spectral Data Collection

- Use a high-resolution spectroradiometer

- Measure leaves still attached to the tree to maintain physiological conditions

- Collect spectral signatures across the Visible-NIR range (e.g., 350-2500 nm)

- Perform measurements at regular intervals (e.g., 1-5 days after stress exposure)

- Standardize measurement conditions (leaf position, illumination, sensor distance)

3. Data Preprocessing

- Apply spectral transformations (e.g., first derivative) to enhance subtle differences

- Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify patterns and reduce dimensionality

4. Model Development and Validation

- Test multiple machine learning approaches: Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest, Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA)

- Train models for both specific stress classification and general stress detection

- Validate models using cross-validation techniques (e.g., tenfold cross-validation with 3 repeats)

- Assess performance using accuracy and Kappa metrics

- Identify key wavelengths for classification through feature importance analysis

This approach has demonstrated high accuracy (0.94-1.0) in detecting the general presence of stress at early stages and differentiating between stress types before visible symptoms appear [3].

Comparative Performance of Detection Methods

Understanding the relative strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications of different detection methods is essential for selecting the right approach for specific research needs.

Table: Comprehensive Comparison of Plant Stress Detection Technologies

| Technology | Detection Stage | Key Measurable Parameters | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Biomarkers [5] | Early alarm phase | DSBM gene expression | High specificity to stress type, detects stress before physiological changes | Destructive sampling, requires laboratory processing |

| Chlorophyll Fluorescence [1] [6] | Early to mid-phase | Fv/Fm ratio (PSII efficiency) | Non-destructive, rapid measurement, portable equipment available | Limited to photosynthetic stress, influenced by multiple factors |

| Hyperspectral Imaging [3] [7] | Early to mid-phase | Reflectance at specific wavelengths (e.g., 684 nm, 1800-1900 nm) | Non-destructive, can detect multiple stress types, applicable from leaf to canopy scale | High cost, computational complexity, requires specialized expertise |

| Thermal Imaging [4] [6] | Early to mid-phase | Canopy temperature | Non-destructive, rapid, sensitive to stomatal closure | Influenced by environmental conditions, indirect stress measurement |

| Traditional Vegetation Indices [7] | Mid to late phase | NDVI, NDWI | Simple to calculate, widely validated, compatible with many platforms | Limited sensitivity for early detection, broad spectral bands |

| Machine Learning-Optimized Indices [7] | Early phase | MLVI, H_VSI | High sensitivity for early detection, tailored to specific stresses | Requires extensive training data, complex development process |

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for early stress detection using spectroscopy and machine learning, integrating the key steps from data acquisition to model application.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Solutions

This section details key research reagents, tools, and technologies essential for conducting comprehensive studies on plant stress responses.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Stress Detection

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field Spectroscopy | CI-710s SpectraVue Leaf Spectrometer [6] | Non-destructive leaf stress measurement | Portable, rapid field deployment, multiple wavelength bands |

| Molecular Assays | ELISA kits for stress hormones [1] | Quantification of abscisic acid, jasmonic acid | High specificity, sensitive detection of low concentrations |

| Luminescence-based ROS/Ca²⁺ assay kits [1] | Detection of early signaling molecules | Simple protocol, quantitative results | |

| Omics Technologies | RNA-seq kits for transcriptomics [5] | DSBM gene expression analysis | Comprehensive, high-throughput, identifies novel biomarkers |

| LC-MS/MS systems [2] | Metabolite and protein profiling | High sensitivity, broad dynamic range | |

| Remote Sensing Platforms | UAV-mounted hyperspectral sensors [7] | Canopy-level stress monitoring | High spatial and spectral resolution, customizable flight plans |

| Thermal infrared cameras [4] [6] | Stomatal conductance assessment | Non-contact temperature measurement, wide area coverage | |

| Data Analysis | Machine learning frameworks (SVM, Random Forest, CNN) [3] [7] | Spectral data classification | Handles high-dimensional data, pattern recognition capabilities |

| Radiative transfer models (PROSPECT, SAIL) [4] | Trait estimation from spectral data | Physically-based, transferable across scales |

The complexity of plant stress responses, spanning microscopic to macroscopic scales and diverse biological processes, makes it challenging for any single technology to comprehensively capture the full spectrum of reactions [1]. Furthermore, the rising prevalence of multifactorial stress conditions highlights the need for research on synergistic and antagonistic interactions between stress factors [1].

Future research must prioritize integrative multi-omic approaches that connect cellular and subcellular processes with morphological and phenological stress responses [1]. Combining multiple remote sensing data streams into crop model assimilation schemes shows particular promise for building Digital Twins of agroecosystems, which may provide the most efficient way to detect the diversity of environmental and biotic stresses and enable respective management decisions [4]. Such integrated approaches will be essential for developing more resilient agricultural systems capable of withstanding the challenges posed by climate change while meeting global food security needs.

The escalating impact of abiotic stressors, particularly drought, on global agriculture necessitates a shift towards precision farming methods. Central to this transformation is the deployment of diverse sensor technologies capable of detecting early signs of plant stress before visible symptoms occur. These sensors form a critical component of the Internet of Things (IoT) ecosystem in agriculture, enabling continuous monitoring of plant physiological status and environmental conditions. This guide provides a systematic comparison of IoT, optical, and environmental sensors, detailing their operational principles and performance in capturing drought stress indicators. By examining experimental data and methodologies from current research, this analysis aims to support researchers, scientists, and agricultural professionals in selecting appropriate sensor technologies for early stress detection systems.

Fundamental Principles of Sensor Operation

IoT-Enabled Plant Sensors

IoT-enabled sensors for plant stress monitoring constitute a network of interconnected devices that collect and transmit data on plant physiological parameters. These sensors typically operate by measuring subtle changes in plant morphology and physiology that occur in response to water deficit. Sap flow sensors monitor the movement of water through plant stems using thermal dissipation or heat pulse methods, providing direct measurement of transpiration rates [8]. Stem diameter sensors, often implemented as linear variable differential transformers (LVDTs), detect micrometer-scale shrinkage in stems that occurs as water tension increases during drought conditions [8]. Acoustic emission sensors capture high-frequency sounds (100-1000 kHz) generated by the formation and collapse of air bubbles within the xylem during cavitation, offering a direct indicator of hydraulic failure [8]. These sensors are typically connected to data loggers with wireless communication capabilities (e.g., LoRaWAN, cellular) that enable real-time data transmission to cloud platforms for continuous monitoring.

Optical and Hyperspectral Sensors

Optical sensors operate on the principle that plant stress alters physiological and biochemical properties that affect light absorption and reflectance. Hyperspectral imaging captures reflectance across hundreds of narrow, contiguous spectral bands from the visible to shortwave infrared regions (350-2500 nm) [9]. These sensors detect stress-induced changes in pigment content, water concentration, and canopy structure that manifest as subtle shifts in spectral signatures. Multispectral sensors measure reflectance in broader, discrete bands but are limited in detecting early stress compared to hyperspectral systems [9]. Advanced systems utilize machine learning-optimized vegetation indices such as the Machine Learning-Based Vegetation Index (MLVI) and Hyperspectral Vegetation Stress Index (H_VSI) which leverage critical spectral bands in the Near-Infrared (NIR), Shortwave Infrared 1 (SWIR1), and Shortwave Infrared 2 (SWIR2) regions [9]. These indices are specifically designed to detect pre-visual stress symptoms by targeting wavelengths sensitive to changes in leaf water content and cellular structure.

Environmental Monitoring Sensors

Environmental sensors measure extrinsic factors in the plant's immediate surroundings that contribute to water stress. Climate sensors monitor atmospheric parameters including air temperature, relative humidity, photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), and vapor pressure deficit (VPD) [8]. Soil moisture sensors employ various technologies such as time-domain reflectometry (TDR), frequency-domain reflectometry (FDR), or capacitance to measure water content in the root zone [8]. These sensors provide context for interpreting plant physiological data by quantifying environmental drivers of water stress. Advanced systems integrate multiple environmental parameters to calculate evapotranspiration rates and water balance models, enabling prediction of developing stress conditions before they significantly impact plant physiology.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Sensor Technologies in Early Drought Stress Detection

| Sensor Category | Specific Sensor Type | Measured Parameters | Key Stress Indicators | Detection Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IoT Plant Sensors | Sap Flow | Sap flow rate, transpiration | Reduced hydraulic conductivity | Early (1-2 days after water withholding) [8] |

| Stem Diameter | Stem micronovement | Stem shrinkage | Early (1-2 days after water withholding) [8] | |

| Acoustic Emission | Ultrasonic signals | Xylem cavitation | Early (1-2 days after water withholding) [8] | |

| Stomatal Dynamics | Stomatal pore area, conductance | Stomatal closure | Early (significant changes observed) [8] | |

| Optical Sensors | Hyperspectral Imaging | Reflectance across 350-2500 nm | Biochemical and structural changes | Very Early (10-15 days earlier than traditional indices) [9] |

| Multispectral Imaging | Reflectance in discrete bands | Chlorophyll degradation | Moderate (when damage already visible) | |

| Environmental Sensors | Climate Sensors | Air temperature, humidity, PAR, VPD | Atmospheric drought conditions | Predictive (before plant stress occurs) |

| Soil Moisture | Volumetric water content | Root zone water availability | Predictive (before plant stress occurs) |

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Sensor Response to Induced Drought Stress

Recent experimental studies provide quantitative data on sensor performance under controlled drought conditions. A comprehensive greenhouse study simultaneously testing ten different sensors on mature tomato plants subjected to water withholding revealed distinct response patterns across sensor types [8]. Sap flow sensors and stem diameter sensors showed significant changes within the first two days of water deprivation, coinciding with depletion of available water in the growth medium [8]. Acoustic emission sensors detected increased cavitation events during this same critical period, providing direct evidence of hydraulic system impairment [8]. Stomatal conductance sensors recorded pronounced decreases in stomatal pore area and conductance rates, indicating the plant's active response to conserve water [8].

Hyperspectral imaging systems demonstrated superior early detection capabilities in field studies, identifying stress symptoms 10-15 days earlier than conventional vegetation indices like NDVI and NDWI [9]. The proposed MLVI-CNN framework, which integrates machine learning-optimized vegetation indices with convolutional neural networks, achieved an impressive classification accuracy of 83.40% in distinguishing six levels of crop stress severity [9]. Furthermore, the optimized indices (MLVI and H_VSI) showed a strong correlation with ground-truth stress markers (r = 0.98), significantly outperforming traditional broadband indices [9].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Sensor Technologies

| Sensor Technology | Detection Accuracy | Early Warning Advantage | Correlation with Ground Truth | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sap Flow Sensors | High for transpiration changes | 1-2 days before visible symptoms | Not specified | Requires physical plant contact |

| Stem Diameter Sensors | High for water tension | 1-2 days before visible symptoms | Not specified | Requires physical plant contact |

| Acoustic Emission Sensors | High for cavitation events | 1-2 days before visible symptoms | Not specified | Background noise interference |

| Hyperspectral Imaging (MLVI-CNN) | 83.40% classification accuracy | 10-15 days earlier than NDVI | r = 0.98 [9] | High computational requirements |

| Traditional Vegetation Indices (NDVI) | Limited for early stress | None - detects already occurred damage | Weak for early stress [9] | Limited spectral sensitivity |

Integration Approaches for Enhanced Detection

Multimodal sensor integration significantly improves detection reliability and reduces false positives. The simultaneous application of multiple sensor types captures complementary aspects of plant stress responses, creating a more comprehensive stress profile [8]. IoT platforms enable the fusion of plant-based sensor data with environmental measurements, allowing researchers to distinguish between drought stress and other abiotic stressors [10]. Machine learning algorithms play a crucial role in analyzing these complex multivariate datasets, identifying patterns that may not be apparent from individual sensor streams [10] [9]. The integration of sensor data with satellite-based monitoring systems, such as the Vegetation Health Index (VHI), further enhances large-scale drought forecasting capabilities [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Controlled Drought Stress Induction

Standardized protocols for inducing drought stress are essential for sensor validation studies. The greenhouse-based experiment conducted by Dutta et al. provides a representative methodology [8]:

Plant Material: Mature, high-wire tomato plants grown in rockwool substrate under controlled greenhouse conditions.

Water Withholding: Complete irrigation cessation for a period of two days, resulting in rapid depletion of available water in the rockwool slabs.

Environmental Control: Maintenance of consistent climatic conditions (temperature, humidity, light) throughout the experiment to isolate water stress effects.

Sensor Deployment: Simultaneous operation of ten different sensor types, including microclimate sensors, acoustic emissions sensors, sap flow sensors, and stem diameter sensors.

Data Collection: Continuous monitoring at high temporal resolution throughout the stress induction period and subsequent recovery phase after rewatering.

This protocol resulted in significant physiological changes, including strongly affected whole-plant transpiration, providing robust data for comparing sensor responsiveness [8].

Hyperspectral Imaging and Analysis Workflow

The methodology for hyperspectral stress detection involves specialized equipment and computational analysis [9]:

Data Acquisition: Collection of hyperspectral imagery using UAV-mounted or ground-based systems capturing hundreds of narrow spectral bands from visible to SWIR regions.

Preprocessing: Application of radiometric calibration, atmospheric correction, and geometric registration to ensure data quality.

Feature Selection: Implementation of Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) to identify optimal spectral bands most sensitive to drought stress.

Index Formulation: Development of machine learning-optimized vegetation indices (MLVI and H_VSI) using the selected critical bands.

Classification: Processing of optimized indices through a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model for multi-class stress severity classification.

Validation: Comparison of classification results with ground-truth stress markers and conventional vegetation indices to quantify performance improvements.

This workflow enabled the detection of stress 10-15 days earlier than traditional methods, with the CNN model effectively distinguishing six levels of crop stress severity [9].

Diagram 1: Hyperspectral Stress Detection Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential process from data acquisition to early stress detection, highlighting the critical role of machine learning optimization in achieving superior detection capabilities.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Sensor-Based Drought Stress Studies

| Category | Item | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Materials | Mature Tomato Plants | High-wire cultivation, rockwool substrate | Controlled greenhouse experiments [8] |

| Ornamental Species | Drought-sensitive cultivars | Physiological stress response studies [12] | |

| Growth Substrates | Rockwool Slabs | Precise moisture control, inert properties | Hydroponic stress induction [8] |

| Sensor Systems | Sap Flow Sensors | Thermal dissipation method | Transpiration monitoring [8] |

| Stem Diameter Sensors | LVDT-based, micrometer resolution | Stem shrinkage measurement [8] | |

| Acoustic Emission Sensors | 100-1000 kHz detection range | Xylem cavitation monitoring [8] | |

| Hyperspectral Imagers | 350-2500 nm spectral range | Biochemical change detection [9] | |

| Data Acquisition | IoT Gateways | Wireless communication (LoRaWAN, cellular) | Real-time data transmission [10] |

| Environmental Controllers | Precision control of temperature, humidity, irrigation | Stress induction protocols [8] | |

| Analysis Tools | Machine Learning Frameworks | Python, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Development of optimized indices [9] |

| Bibliometric Analysis Software | VOSviewer, CitNetExplorer | Research trend analysis [12] |

This comparison of sensor technologies for drought stress detection reveals a complementary relationship between IoT-enabled plant sensors, optical systems, and environmental monitors. Each category offers distinct advantages: IoT sensors provide direct, high-temporal-resolution measurements of plant physiological responses; hyperspectral imaging enables very early detection through subtle spectral signatures; and environmental sensors offer predictive capabilities by monitoring stress drivers. The experimental data demonstrates that a multimodal approach, leveraging the strengths of each technology, provides the most comprehensive assessment of plant stress status. Future advancements will likely focus on enhanced sensor fusion algorithms, increased deployment of UAV-based systems for scalable monitoring, and development of more sophisticated machine learning models for predictive analytics. These technological innovations, validated through rigorous experimental protocols, hold significant promise for transforming agricultural water management and mitigating the impacts of drought stress on crop production.

Drought stress significantly threatens global ecosystem stability and agricultural productivity. Early and accurate detection of drought stress is crucial for developing mitigation strategies, informing irrigation schedules, and guiding breeding programs for more resilient crops. This guide objectively compares three key physiological indicators used in drought stress detection research: soil moisture, canopy temperature, and chlorophyll fluorescence.

Each indicator operates on distinct physiological principles, varies in its measurement technology, and offers unique advantages and limitations. Soil moisture directly measures water availability in the root zone. Canopy temperature serves as a proxy for plant water status by measuring the cooling effect of transpiration. Chlorophyll fluorescence provides a window into the fundamental efficiency of the photosynthetic apparatus under stress. Understanding their comparative performance is essential for selecting the appropriate tool for specific research applications, from high-throughput phenotyping to mechanistic studies on plant-environment interactions.

Comparative Analysis of Key Drought Indicators

The table below provides a structured comparison of the three drought indicators, summarizing their fundamental principles, measurement approaches, key parameters, and performance characteristics based on current research.

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of key drought indicators for early stress detection.

| Indicator | Soil Moisture | Canopy Temperature (CT)/CTD | Chlorophyll Fluorescence (ChlF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological Basis | Direct measure of water availability in the soil root zone. | Proxy for plant water status; cooler canopies indicate higher transpirational cooling. [13] | Probe of Photosystem II (PSII) efficiency; reflects photochemical and non-photochemical quenching. [14] |

| Primary Measurement | Volumetric water content (m³/m³) or soil water potential. | Canopy Temperature Depression (CTD) = Air Temperature - Canopy Temperature. [13] | Kinetic Parameters (e.g., Fv/Fm); Spectral Ratio (e.g., LD685/LD740); Solar-Induced Fluorescence (SIF). [14] |

| Key Measurable Parameters | Relative soil moisture, Soil Moisture Drought Indices (e.g., ESMDI, SSMA). [15] [16] | Canopy temperature, CTD. [13] | Fv/Fm (maximal PSII efficiency), LD685/LD740 (chlorophyll content indicator), SIF yield. [14] |

| Temporal Response to Drought | Slow to medium-term response; reflects water reservoir. | Near real-time indicator of plant water status. | Dual-phase response; rapid initial change in SIF followed by slower decline. [17] |

| Correlation with Photosynthesis & Yield | Indirect; affects water availability for photosynthesis. | Significant correlation with yield under drought and heat stress. [13] [18] | Strengthened correlation with photosynthetic traits (An, Vcmax, Jmax) under drought stress. [14] |

| Measurement Technology | In-situ sensors, Remote Sensing (SMAP, SMOS), Land Surface Models. [15] | Handheld infrared thermometers, thermal cameras. [13] [18] | Pulse-Amplitude-Modulation (PAM) fluorometers, hyperspectral sensors for SIF. [14] |

| Key Advantages | Direct measure of driver; supports hydrological modeling. | High-throughput, integrativemeasure, relatively simple and cost-effective. [13] | Highly sensitive, non-destructive, direct probe of photosynthetic function. [14] |

| Key Limitations/Challenges | Spatial heterogeneity; point measurements may not represent root zone; remote sensing has shallow depth. [15] | Influenced by microclimate, wind, plant density, and spike presence. [13] | Sensitive to various environmental factors; complex interpretation; specialized equipment needed. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Soil Moisture Alternative Stable States Experiment

- Objective: To investigate the long-term impact of repeated moderate and intense natural drought on soil moisture dynamics and resilience in an upland heath ecosystem. [19]

- Site & Soil: The experiment was conducted in Wales (UK) on a podzolic organo-mineral soil with an organic horizon (~10 cm) overlying a mineral layer. [19]

- Experimental Design: A long-term (15-year) drought manipulation experiment was established with two main treatments:

- Control: Natural rainfall conditions.

- Drought Treatment: A sustained modest reduction of summer rainfall (20-26%) using automated rain shelters. [19]

- Measurements:

- Soil Moisture: Continuously monitored in the upper organic soil horizon (~10 cm) within plots for 15 years. [19]

- Supporting Data: Soil water retention curves, saturated hydraulic conductivity, soil bulk density, and soil respiration rates were measured. [19]

- Vegetation Control: Soil moisture was also measured in adjacent Calluna vulgaris-free areas to isolate the effect of vegetation. [19]

- Modeling: A 1-D hydrological model was parameterized and run with different lower boundary conditions (seepage face vs. free drainage) to interpret observed shifts. [19]

- Key Findings: The experiment provided evidence for drought-induced alternative stable states in soil moisture. Repeated moderate drought gradually reduced soil moisture retention, while an intense natural drought (2003-2006) caused an irreversible shift in soil hydraulic properties, preventing winter rewetting in both control and drought plots, but not in vegetation-free areas. [19]

Canopy Temperature Depression (CTD) in Wheat Breeding

- Objective: To evaluate CTD as a selection criterion for drought and heat tolerance in wheat breeding programs. [13]

- Plant Material & Growth: Diverse wheat genotypes are cultivated in field trials under well-watered, terminal drought, and terminal heat stress conditions. [18]

- CTD Measurement Protocol:

- Timing: Measurements are taken around solar noon (e.g., 11:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m.) on clear, windless days, typically during the grain-filling stage. [13] [18]

- Instrumentation: A handheld infrared thermometer is held approximately 50 cm above the canopy. [13]

- Technique: The instrument is pointed at an angle to the rows to minimize the influence of soil background, especially with low ground cover. [13]

- Data Recording: Multiple measurements per plot are taken for reliability. The corresponding air temperature is recorded from a nearby weather station. [18]

- Calculation: CTD is calculated as CTD = Air Temperature - Canopy Temperature. Positive values indicate a cooler canopy due to transpiration. [13]

- Key Findings: CTD shows a significant correlation with grain yield under drought and heat stress. Genotypes with higher CTD (cooler canopies) maintain better yield, and this trait has been successfully integrated into high-throughput phenotyping and selection pipelines, such as those at CIMMYT. [13]

Chlorophyll Fluorescence Response to Drought Stress

- Objective: To assess the link between ChlF parameters and photosynthetic traits under progressive drought stress at the leaf level. [14]

- Plant Material & Drought Treatment: The experiment used cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) plants grown in a controlled environment. A drought treatment was imposed by withholding irrigation, while a control group was well-watered. [14]

- Simultaneous Measurements Protocol:

- Gas Exchange: Leaf net CO2 assimilation rate (An), stomatal conductance (gs), and other parameters were measured with a portable gas exchange system. [14]

- ChlF Kinetics: A fluorometer was used to measure dark-adapted maximum quantum efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm). [14]

- ChlF Spectrum: Laser-induced fluorescence was used to obtain the spectral intensity ratio (LD685/LD740), an inverse indicator of chlorophyll content. [14]

- Leaf Sampling: Total chlorophyll content (Chlt) was determined analytically. [14]

- Key Findings: Drought stress strengthened the correlation between ChlF ratios (Fv/Fm and LD685/LD740) and photosynthetic traits (An, Vcmax, Jmax). The study demonstrated that ChlF can track the complex cascade of plant responses to drought, from initial stomatal closure to biochemical limitations and pigment decomposition. [14]

Conceptual Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the conceptual frameworks and experimental workflows for the three drought indicators.

Soil Moisture State Transition

Canopy Temperature Data Acquisition

Chlorophyll Fluorescence Response

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key equipment and reagents for drought stress detection research.

| Item | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Handheld Infrared Thermometer | Measures canopy surface temperature remotely to calculate Canopy Temperature Depression (CTD). | High-throughput field phenotyping for drought and heat tolerance in breeding programs. [13] [18] |

| Pulse-Amplitude-Modulation (PAM) Fluorometer | Measures chlorophyll fluorescence kinetics (e.g., Fv/Fm) to assess PSII photochemical efficiency. | Leaf-level mechanistic studies of photosynthetic performance under controlled and field drought conditions. [14] |

| Hyperspectral Sensors / Solar-Induced Fluorescence (SIF) Sensors | Detects solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence emission, often from airborne or satellite platforms. | Regional-scale monitoring of photosynthetic activity and drought impacts on ecosystem gross primary production (GPP). [17] |

| Soil Moisture Sensors (e.g., TDR, FDR) | Provides in-situ point measurements of volumetric soil water content. | Ground-truthing for remote sensing products and fine-scale studies of soil-plant-water relations. [15] |

| Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) Satellite Data | Provides global-scale, satellite-derived soil moisture data at a spatial resolution of ~25-36 km. | Large-scale agricultural and hydrological drought monitoring, input for drought indices. [15] [20] |

| Deep Learning Models (e.g., U-Net) | Integrates meteorological and satellite data to downscale soil moisture and improve flash drought detection. | High-resolution (e.g., 1 km) spatiotemporal drought monitoring and early warning systems. [15] [20] |

Drought stress poses a significant threat to global crop productivity and food security. Early and accurate detection is paramount for implementing timely mitigation strategies, such as precision irrigation. The emerging field of high-throughput plant phenomics leverages a suite of sensor technologies to non-invasively capture the physiological alterations crops undergo during water deficit. This guide objectively compares the performance of multiple sensing modalities—from satellite remote sensing to ground-based sensors—in detecting the early, often invisible, signs of drought stress. By linking sensor data to specific physiological phases, this pipeline provides researchers and agricultural professionals with a powerful toolkit for breeding resilient varieties and enabling climate-smart agriculture.

Comparative Analysis of Sensor Technologies for Drought Phenotyping

A diverse array of platforms and sensors is employed to capture crop responses to drought stress across different scales, from the field to the individual plant. The following table summarizes the key characteristics and performance metrics of these technologies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Sensor Technologies for Drought Stress Detection

| Sensor Technology | Primary Measured Parameters | Key Drought Indicators | Reported Accuracy/Performance | Notable Advantages & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperspectral Imaging [9] | Reflectance across hundreds of narrow, contiguous bands (NIR, SWIR). | Machine Learning-based Vegetation Index (MLVI), Hyperspectral Vegetation Stress Index (H_VSI). | 83.40% classification accuracy for 6 stress severity levels; detects stress 10-15 days earlier than conventional indices. | High spectral sensitivity for early detection; computationally intensive. |

| Multispectral & RGB Cameras [21] [22] | Reflectance in broad bands (e.g., Red, Green, Red-Edge, NIR) and visible spectrum color. | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI), canopy morphology, leaf wilting/curling. | Up to 97% precision for stressed class in potatoes; 96.71% accuracy and F1-score in winter wheat when fused with VIs. | Cost-effective; readily deployed on UAVs; RGB lacks spectral sensitivity of dedicated imagers. |

| Thermal Imaging [23] [24] | Canopy temperature (radiometric). | Canopy Temperature Depression (CTD), Water Stress Index (WSI). | Accurately extracted average temperature (R² = 0.8056) in strawberry phenotyping robot [23]. | Directly measures plant water status (stomatal conductance); sensitive to ambient weather conditions. |

| Multi-Source Sensor Fusion [23] [22] | Combines data from RGB, multispectral, thermal, and LiDAR sensors. | Fused phenotypic parameters (canopy structure, temperature, vegetation indices). | Achieved errors below 5% for canopy width and temperature extraction [23]. | Provides comprehensive 3D representation of plant status; complex data synchronization and analysis. |

| Novel Plant-Specific Sensors [8] | Sap flow, stem diameter, stomatal dynamics, acoustic emissions. | Whole-plant transpiration, stomatal conductance, stem diameter variation, xylem cavitation. | Significant indicators of early drought stress with clear onset timing after water withholding [8]. | Provide direct, mechanistic physiological data; often require physical attachment to plants. |

Experimental Protocols for Sensor-Based Drought Detection

Protocol 1: Hyperspectral Imaging with Machine Learning

This protocol details the methodology for developing machine learning-optimized hyperspectral indices and a classification model for early stress detection [9].

- Data Acquisition: Hyperspectral imagery is captured using UAV or ground-based platforms, collecting reflectance data across hundreds of narrow bands in the Visible, Near-Infrared (NIR), and Short-Wave Infrared (SWIR) regions.

- Preprocessing & Feature Selection: Raw data undergo calibration and noise reduction. Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) is applied to identify the most informative spectral bands critical for detecting water stress, typically located in the NIR and SWIR regions.

- Index Formulation: Novel hyperspectral indices, such as the Machine Learning-based Vegetation Index (MLVI) and Hyperspectral Vegetation Stress Index (H_VSI), are computed from the selected bands.

- Model Training & Classification: The optimized indices serve as input features for a 1D Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model, which is trained to classify crops into multiple levels of drought stress severity.

Protocol 2: Multimodal Fusion of RGB and Vegetation Indices

This protocol outlines the creation of a lightweight deep learning network that fuses RGB images and numerical vegetation index data for monitoring drought stress in winter wheat [22].

- Experimental Design & Data Collection: A controlled field experiment is established with multiple levels of water treatment (e.g., from suitable moisture to extreme drought). RGB images and multispectral data (for calculating NDVI and EVI) are collected from the plots throughout the growth cycle.

- Data Preprocessing: Images are annotated and prepared. Vegetation indices are calculated from the multispectral data.

- Model Architecture (MF-FusionNet): A lightweight network is built featuring a Lightweight Multimodal Fusion Block (LMFB) to deeply fuse image and index data. A Dual-Coordinate Attention Feature Extraction module (DCAFE) enhances feature representation, and a Cross-Stage Feature Fusion Strategy (CFFS) integrates multi-level features.

- Training & Validation: The model is trained on the dataset, and its performance is validated against ground-truth drought levels through ablation studies and comparison with single-modal methods.

Protocol 3: Multi-Source Sensor Data Fusion on a Robotic Platform

This protocol describes the use of an integrated robotic phenotyping platform for unified data acquisition and analysis [23].

- Platform Configuration: A robotic ground vehicle is equipped with a synchronized suite of sensors, including an RGB-D camera, a multispectral camera, a thermal camera, and a LiDAR sensor.

- Synchronized Data Acquisition: The platform navigates through crop rows (e.g., strawberries in a greenhouse), simultaneously collecting data from all sensors. This ensures spatial and temporal alignment of the multi-modal data.

- Data Fusion and Parameter Extraction: The data from different sensors are fused. For instance, LiDAR data provides precise 3D canopy structure, which is integrated with thermal data for temperature analysis and multispectral data for index calculation. Key phenotypic parameters like canopy width and average temperature are extracted with high accuracy.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core molecular pathways activated during drought stress and a generalized workflow for a sensor-based phenotyping pipeline.

Drought Stress Signaling Pathways

This diagram summarizes the key molecular signaling pathways plants activate in response to drought and heat stress, which lead to the physiological changes detected by sensors [24].

Sensor Data Phenotyping Pipeline

This flowchart outlines the generalized workflow for processing multi-source sensor data to identify and map drought stress in crops, integrating elements from several studies [9] [21] [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This section catalogs key hardware, software, and analytical tools that constitute the modern phenotyping pipeline for drought stress research.

Table 2: Essential Research Toolkit for Drought Stress Phenotyping

| Tool Category | Specific Tool / Technique | Primary Function in the Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Sensing Platforms | Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs/Drones) [9] [21] | Deploy sensors for high-throughput, field-scale aerial imagery. |

| Ground Robotic Phenotyping Rigs [23] | Enable precise, multi-sensor data collection at plant-level resolution. | |

| Satellite Platforms (e.g., Sentinel-2) [24] | Provide broad-area monitoring for regional drought assessment. | |

| Core Sensors | Hyperspectral Imaging Sensors [9] | Capture high-resolution spectral data for early physiological change detection. |

| Multispectral & RGB Cameras [21] [22] | Acquire data for calculating vegetation indices and visual assessment. | |

| Thermal Infrared Cameras [23] [24] | Measure canopy temperature as a proxy for stomatal conductance and plant water status. | |

| LiDAR Sensors [23] | Generate 3D point clouds for precise canopy structure and biomass estimation. | |

| Plant-Specific Sensors (Sap Flow, Stem Diameter) [8] | Provide direct, continuous measurements of plant physiological activity. | |

| Computational & Analytical Tools | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [9] [21] [22] | Automate feature extraction and classification from complex image data. |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) [9] | Identify the most informative spectral bands from hyperspectral data. | |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Techniques (e.g., Grad-CAM) [21] | Visualize model decision-making, enhancing interpretability and trust. | |

| Data Fusion Frameworks [23] [22] | Integrate multi-source, multi-modal data into a unified analysis model. |

The integration of diverse sensor technologies into a cohesive phenotyping pipeline has fundamentally advanced our ability to detect and quantify crop drought stress. As evidenced by the comparative data, no single sensor is a panacea; rather, the synergy of multimodal data—from hyperspectral indices that signal stress days before visible symptoms appear, to thermal data revealing stomatal behavior, and 3D LiDAR capturing structural degradation—provides the most robust picture of plant health. The future of this field lies in the refinement of integrated, lightweight models like MF-FusionNet [22] and the wider adoption of explainable AI [21] to build trust and mechanistic understanding. By effectively linking sensor data to physiological phases through standardized protocols and powerful computational analysis, researchers are equipped to accelerate the development of drought-resilient crops and optimize management practices for a warming world.

Methodologies and Real-World Applications of Multi-Sensor Systems

The increasing frequency and severity of drought events due to climate change have intensified the need for precise and early detection of plant stress. Sensor fusion has emerged as a powerful methodology that integrates data from multiple sources—including Internet of Things (IoT) networks, proximal sensors, and remote sensing platforms—to provide a more comprehensive, accurate, and timely assessment of drought conditions than any single data source can achieve. This approach mitigates the limitations inherent in individual sensing modalities, such as sparse spatial coverage, low temporal resolution, or insufficient physiological depth. In the context of drought research, fusing data from these complementary sources enables scientists to monitor the complex, multi-scale processes of water stress manifestation, from regional climate patterns to plant-level physiological responses.

The fundamental architectures for combining these diverse data streams can be categorized by the stage at which integration occurs: data-level, feature-level, and decision-level fusion. Data-level fusion (or early fusion) combines raw data from multiple sources before feature extraction, requiring precise spatial and temporal registration. Feature-level fusion involves extracting features from each data source independently and then merging them into a unified feature vector for model input. Decision-level fusion (or late fusion) processes each data stream separately to produce independent inferences or decisions, which are subsequently combined through methods like voting or averaging. Recent advances in machine learning and edge computing have further enhanced these architectures, enabling more sophisticated and real-time analysis capabilities for drought stress detection [25] [26].

Comparative Analysis of Sensor Fusion Architectures

The performance of different sensor fusion architectures varies significantly based on their design, implementation, and application context. The following experimental data, drawn from recent studies, provides a quantitative basis for comparing their effectiveness in drought stress detection and related agricultural applications.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Sensor Fusion Architectures

| Fusion Architecture | Application Context | Data Sources Fused | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kriging with External Drift (KED) [27] | Irrigation Management Zoning | Proximal (EM38-MK2), Satellite (Landsat-8, Aster, Sentinel-2), Terrain Covariates | R²: 0.78, MAE: 1.26, RMSE: 1.62, RPD: 1.76 | Outperformed GWR; closely resembled exhaustive reference map |

| Feature-Level Fusion with ML [25] | Poplar Drought Monitoring | Visible & Thermal Infrared Images | Average Accuracy: 0.85, Precision: 0.86, Recall: 0.85, F1 Score: 0.85 | Superior to data-level fusion and decision-level fusion approaches |

| Stacking (ST) Ensemble Model [28] | Meteorological Drought Forecasting (SPEI-12) | Multi-source (Climate, Vegetation, Terrain, Anthropogenic) | Average R²: 0.845 | Outperformed XGBoost, RF, and LightGBM base learners |

| Energy-Aware Adaptive Fusion [29] | Autonomous Robot Navigation in Channels | RGB Camera, LiDAR, IMU | Energy Reduction: 35%, Navigation Accuracy: 98% | Maintained performance while significantly reducing power consumption |

| CNN with MLVI & H_VSI Indices [7] | Hyperspectral Crop Stress Detection | UAV-based Hyperspectral Imagery | Classification Accuracy: 83.40% | Detected stress 10-15 days earlier than NDVI/NDWI |

Table 2: Qualitative Comparison of Fusion Architectures

| Fusion Architecture | Scalability | Computational Demand | Implementation Complexity | Real-Time Processing Potential | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kriging with External Drift (KED) | Moderate | Moderate | High | Low | Effective for spatial data; integrates point measurements with raster covariates |

| Feature-Level Fusion with ML | High | High | Moderate | Moderate | Balances accuracy and computational cost; preserves feature integrity [30] |

| Stacking (ST) Ensemble Model | High | High | High | Low | High predictive accuracy; captures complex non-linear relationships |

| Energy-Aware Adaptive Fusion | Moderate | Low to Moderate | High | High | Enables long-duration operation; ideal for resource-constrained devices |

| CNN with Novel Indices | High | High | Moderate | Moderate with optimized hardware | Enables very early stress detection; high spectral sensitivity |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Geospatial Fusion for Irrigation Management Zoning

A study on precision irrigation management demonstrated a protocol for fusing proximal and remote sensing data to create accurate soil property maps. The experiment was conducted in a 72-hectare grain-producing area in Brazil. Researchers first collected an exhaustive dataset of apparent electrical conductivity (aEC) using an EM38-MK2 proximal soil sensor, with 3906 points distributed along 26 transects. A sparse dataset simulating practical sampling constraints was then created, containing only 162 aEC points from four transects. The exhaustive dataset was mapped using Ordinary Kriging (OK) to create a reference map. The sparse dataset was then enhanced using Kriging with External Drift (KED) and Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR), which incorporated auxiliary variables from Landsat-8, Aster, and Sentinel-2 satellites, along with ten terrain covariates from the Alos Palsar digital elevation model. The resulting maps were validated against clay content samples from 72 points. The KED method demonstrated a strong fit (R² = 0.78) and was most effective at defining irrigation management zones that matched the reference, showcasing the value of fusing sparse proximal data with dense remote sensing covariates [27].

Multi-Modal Plant Phenotyping for Drought Stress

A controlled experiment established a rigorous protocol for monitoring poplar drought stress using feature-level fusion. Researchers subjected poplar trees to gradient drought stress and collected multimodal image data, including visible and thermal infrared images. The study systematically compared four data processing methodologies: data decomposition, data layer fusion, feature layer fusion, and decision layer fusion. For feature-level fusion, features were first extracted from each image modality independently. These feature sets were then concatenated into a unified feature vector, which served as input to train five different machine learning models: Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, GBDT, DT, and CatBoost. The hyperparameters of these models were optimized using Bayesian optimization. The model performance was evaluated via five-fold cross-validation, with metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. The results confirmed that the feature-layer fusion approach provided the best balance of performance metrics, achieving an average accuracy of 0.85, significantly outperforming other fusion strategies [25].

Ensemble Learning for Meteorological Drought Forecasting

A novel fusion-based framework for forecasting the Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) employed a stacking (ST) ensemble model. The study integrated multi-source data encompassing meteorological variables, vegetation indices, anthropogenic factors, landcover, climate teleconnection patterns, and topological characteristics. The first-level base learners consisted of three distinct algorithms: Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Random Forest (RF), and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM), which were trained on the multi-source data to make initial predictions. A meta-learner was then trained to combine these predictions into a final forecast, learning the optimal weighting for each base model. The model was designed to forecast the one-month lead SPEI at a 12-month scale (SPEI-12). It was trained on data from 2001-2017 and tested on data from 2018 for the Berlin-Brandenburg region in Germany. The ST model's performance was benchmarked against a persistence model and its individual base learners, with the ST model achieving an average R² of 0.845, demonstrating the superiority of the ensemble approach [28].

Architectural Diagrams and Workflows

Generalized Sensor Fusion Workflow for Drought Stress Detection

The following diagram illustrates a unified logical workflow for integrating IoT, proximal, and remote sensing data for early drought stress detection, synthesizing common elements from the reviewed architectures.

Feature-Level Fusion Architecture with Machine Learning

This diagram details the specific workflow for feature-level fusion, which demonstrated superior performance in the poplar drought monitoring study [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Sensor Fusion in Drought Studies

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Technology | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal Sensors | EM38-MK2 (Electromagnetic Induction Sensor) | Measures soil apparent electrical conductivity (aEC) as a proxy for texture and moisture [27] | Irrigation management zoning; mapping soil heterogeneity |

| IoT Sensor Networks | Soil Moisture Sensors, Micro-climate Stations | Provide continuous, high-temporal resolution data on soil and atmospheric conditions | Ground-truthing remote sensing data; micro-climate monitoring |

| Remote Sensing Platforms | Sentinel-2, Landsat-8, UAV-mounted Hyperspectral Sensors | Capture spatial and spectral information at various resolutions (e.g., VNIR, SWIR) [7] [31] | Calculating vegetation indices; monitoring crop health at scale |

| Data Fusion Algorithms | Kriging with External Drift (KED), Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) | Spatially interpolate point data using auxiliary remote sensing covariates [27] | Creating continuous surfaces from sparse proximal sensor measurements |

| Machine Learning Models | Random Forest, XGBoost, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) | Classify stress levels, forecast drought indices, and perform feature selection [25] [28] | Multi-class drought severity classification; SPEI forecasting |

| Vegetation Indices | Machine Learning-Based Vegetation Index (MLVI), Hyperspectral Vegetation Stress Index (H_VSI) | Sensitive indicators of plant water status and early stress [7] | Early stress detection 10-15 days before conventional indices |

| Edge Computing Hardware | In-Sensor and Near-Sensor Computing Architectures | Process data at source to reduce latency and energy consumption [26] | Real-time processing on UAVs or autonomous robots for immediate action |

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models for Predictive Drought Analytics

Drought is a major natural disaster with significant economic and social implications, affecting ecosystems, agriculture, and water security globally [32]. The frequency and severity of drought events have increased in recent years due to climate change, making accurate drought prediction crucial for effective disaster management and mitigation strategies [11] [33]. Predictive drought analytics has evolved substantially with the adoption of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models, which offer powerful capabilities for capturing complex, non-linear relationships in hydroclimatic data that traditional statistical methods often miss [11] [34].

This comparison guide provides a comprehensive performance evaluation of ML and DL models used in predictive drought analytics. We examine experimental data from recent studies (2024-2025) to objectively compare model effectiveness across different drought types, temporal scales, and geographical contexts. The analysis is framed within the broader research theme of performance evaluation for early drought stress detection, with particular attention to multi-sensor data integration and model interpretability.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Model Architectures and Training Frameworks

Gradient Boosting Methods: Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) and Categorical Boosting (CatBoost) have been widely applied for drought prediction. These ensemble methods combine multiple decision trees to improve predictive accuracy. In recent implementations, models were trained using 26 features for monthly predictions and 18 features for seasonal predictions, with hyperparameter tuning conducted through grid search or Bayesian optimization [33]. The training typically involves minimizing a specified loss function (e.g., mean squared error) using gradient descent, with early stopping to prevent overfitting.

Deep Learning Architectures: Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and hybrid convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have demonstrated strong performance for temporal drought forecasting. LSTM models effectively capture temporal dependencies in sequential climate data through their gating mechanisms that regulate information flow [34]. Recent implementations often incorporate wavelet transformations (WT) as a preprocessing step to decompose time series data into different frequency components, enhancing the model's ability to capture multi-scale patterns [34]. Hybrid architectures like CNN-LSTM combine spatial feature extraction with temporal sequence modeling.

Hybrid DL-Dynamic Models: Innovative approaches have emerged that combine deep learning with physical dynamic models. For instance, the RISE-UNet architecture incorporates residual inception squeeze-and-excitation modules with U-Net style skip connections. This model takes inputs from both reanalysis data at weekly lags and reforecast data at forecast leads, learning complex mapping functions between input variables and root zone soil moisture targets [35]. These hybrid models are trained to predict drought indicators by leveraging both historical observations and dynamic model forecasts.

Input Features and Data Preprocessing

The performance of drought prediction models heavily depends on feature selection and data quality. Common input features include:

- Climate Indices: Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI), Standardized Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI), Palmer Drought Severity Index (PDSI) [33] [32]

- Soil Moisture Measurements: Root zone soil moisture, surface soil moisture, and deep soil moisture [35] [32]

- Remote Sensing Data: Vegetation Health Index (VHI), Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI), land surface temperature [11] [7] [36]

- Climate Variables: Precipitation, temperature, evapotranspiration, runoff [33] [32]

Data preprocessing typically involves handling missing values through interpolation, normalizing or standardizing features, and addressing temporal alignment issues across different data sources [32]. For hyperspectral data applications, recursive feature elimination (RFE) is often employed to identify optimal spectral bands and reduce computational complexity [7].

Evaluation Metrics and Validation Approaches

Model performance is typically assessed using multiple statistical metrics:

- Accuracy and Precision: For classification tasks, particularly in drought category prediction [33]

- Correlation Coefficients: Pearson's r to measure linear relationships between predicted and observed values [11] [34]

- Root Mean Square Error (RMSE): To quantify prediction error magnitude [34]

- Anomaly Correlation Coefficient (ACC): For evaluating spatial pattern matching [35]

- Continuous Ranked Probability Score (CRPS): For probabilistic forecast evaluation [35]

Validation approaches include temporal hold-out validation, k-fold cross-validation, and spatial cross-validation to assess model generalizability across different regions and climate conditions [11].

Performance Comparison of ML/DL Models

Table 1: Comparative performance of machine learning and deep learning models for drought prediction

| Model | Application Context | Performance Metrics | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost [33] [32] | Hydrological drought classification | 79.9% accuracy for drought category prediction | Handles structured tabular data well; minor hyperparameter tuning required | Limited inherent interpretability without SHAP |

| LSTM with Wavelet Transform [34] | Effective Drought Index (EDI) forecasting in Norway | r = 0.9765, NSE = 0.9510, RMSE = 0.2207 | Captures temporal dependencies effectively; enhanced with frequency analysis | Computationally intensive; requires large datasets |

| Gradient Boosting [11] | Large-scale VHI forecasting in Brazil | Better performance during La Niña events; effective VHI threshold forecasting | Easily captures non-linear relationships; no assumption of response function shape | Lower performance in South Brazil regions |

| Hybrid DL-Dynamic (RISE-UNet) [35] | Subseasonal soil moisture drought forecasts | ACC ~0.60 at week 3 (66% improvement over dynamic models) | Combines historical patterns with physical model forecasts; skillful up to 4 weeks | Complex architecture; computationally demanding |

| CNN with Hyperspectral Indices [7] | Crop stress severity classification | 83.40% accuracy for six stress levels; detects stress 10-15 days earlier than NDVI | Early detection capability; processes hyperspectral data effectively | Requires specialized hyperspectral data |

| Random Forest & SVM [37] [32] | Short-term drought forecasting | Effective for short-term predictions; >90% accuracy in some stress detection applications | Performs well with limited data; less prone to overfitting | Lower performance for long-term predictions |

Table 2: Performance across drought types and temporal scales

| Drought Type | Best Performing Models | Key Predictive Features | Typical Forecast Horizon | Accuracy Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Drought [11] [7] | CNN with hyperspectral indices; Gradient Boosting | VHI, soil moisture, hyperspectral indices (MLVI, H_VSI) | Days to weeks (early stress detection) | 83-94% classification accuracy |

| Hydrological Drought [33] | XGBoost with SHAP interpretation | SPI, soil moisture content, evapotranspiration | Monthly to seasonal | ~80% classification accuracy |

| Meteorological Drought [32] [34] | LSTM-Wavelet; AI-based drought indices | Precipitation, temperature, evapotranspiration | Monthly to seasonal | r = 0.78-0.98 with observations |

| Soil Moisture Drought [35] | Hybrid DL-Dynamic Models | Antecedent soil moisture, precipitation forecasts | Subseasonal (up to 4 weeks) | ACC ~0.60 at week 3 |

Key Performance Insights

The comparative analysis reveals several important patterns in model performance:

Spatial and Temporal Considerations: Gradient boosting methods have shown better performance for forecasting vegetation health in north and northeast Brazil compared to south Brazil, highlighting the importance of regional calibration [11]. For temporal scales, random forest and SVM models remain effective for short-term drought forecasting, while LSTM and hybrid DL models demonstrate superior performance for long-term predictions [37].

Model Interpretability: Approaches combining XGBoost with SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) values provide both predictive accuracy and interpretability, identifying that SPI is the most influential feature for hydrological drought prediction with SHAP values of 0.360, 0.261, 0.169, and 0.247 across spring, summer, autumn, and winter respectively [33].

Hybrid Model Advantages: The combination of deep learning with dynamic models (DL-DM) has demonstrated significant improvements in forecasting skill for root zone soil moisture, particularly at subseasonal timescales (weeks 3-4) where traditional dynamic models show limited skill [35]. These hybrid approaches leverage both data-driven pattern recognition and physical understanding encapsulated in dynamic models.

Visualization of Methodologies and Workflows

Experimental Workflow for Drought Prediction

Experimental Workflow for Drought Prediction

Hybrid DL-Dynamic Model Architecture

Hybrid DL-Dynamic Model Architecture

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational resources for drought prediction studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Datasets | Application in Drought Research | Data Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drought Indices [33] [32] [34] | SPI, SPEI, EDI, PDSI, VHI | Quantify drought severity and characteristics; target variables for ML models | Various temporal scales (1-12 months); regional specificity |

| Remote Sensing Data [11] [7] [36] | MODIS, AVHRR, Sentinel-2, Hyperspectral imaging | Vegetation health monitoring; early stress detection; soil moisture estimation | Spatial resolutions: 0.05° to 1km; daily to monthly temporal resolution |

| Climate Reanalysis [35] [32] | ERA5, GLEAM, CHIRPS, GPM | Model training; feature engineering; historical context | Global coverage; multi-decadal records; multiple variables |

| Soil Moisture Data [35] [32] [36] | GLEAM RZSM, in-situ sensors, SMAP | Agricultural drought assessment; model initialization and validation | Various depths (surface, root zone); point measurements to gridded products |

| ML/DL Frameworks [33] [37] [34] | XGBoost, TensorFlow, PyTorch, Scikit-learn | Model development and training; hyperparameter optimization | Varying computational requirements; different specialization |

| Interpretability Tools [33] | SHAP, LIME, permutation feature importance | Model diagnostics; feature importance analysis; result interpretation | Model-agnostic and specific approaches; quantitative importance scores |

The comparative analysis of machine learning and deep learning models for predictive drought analytics reveals a rapidly evolving field with several promising directions. Model selection should be guided by specific application requirements: gradient boosting methods like XGBoost provide strong performance for classification tasks with structured data, while LSTM and hybrid models excel at capturing temporal dependencies for forecasting. The integration of explainable AI techniques like SHAP addresses the interpretability challenges of complex models, enhancing their utility for decision-making.

The most significant performance improvements have emerged from hybrid approaches that combine the pattern recognition capabilities of deep learning with physical understanding from dynamic models [35]. These approaches demonstrate particular value for subseasonal forecasting of soil moisture drought, extending skillful predictions beyond the two-week barrier that limits many traditional dynamic models.

Future developments will likely focus on integrating multi-scale data from diverse sources, enhancing model interpretability for operational applications, and improving cross-regional generalizability through transfer learning and meta-learning approaches. As drought events increase in frequency and severity under climate change, these advanced ML and DL models will play an increasingly critical role in early warning systems and mitigation strategies.

The accurate and early detection of drought stress is critical for safeguarding wheat production and ensuring global food security. This evaluation explores the performance of various technological sensors and models for drought stress monitoring, with a specific focus on the multimodal deep learning S-DNet model. By integrating multiple data sources, including visual imagery and meteorological information, S-DNet achieves a high average drought recognition accuracy of 96.4% [38]. This guide objectively compares the S-DNet framework against other contemporary sensor-based and model-driven approaches, providing researchers with a detailed analysis of experimental protocols, performance data, and the essential toolkit required for advanced drought stress detection research.

Experimental Comparison of Drought Monitoring Models

The table below summarizes the performance and key characteristics of various models discussed in recent literature for monitoring drought stress in wheat.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Drought Monitoring Models and Approaches

| Model/Approach Name | Primary Data Modality | Reported Performance Metrics | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-DNet [38] | Multimodal (RGB Images + Meteorological Sensor Data) | Average Accuracy: 96.4% [38] | Drought stress classification |

| MF-FusionNet [22] | Multimodal (RGB Images + Vegetation Indices) | Accuracy: 96.71%, Recall: 96.71%, F1-Score: 96.64% [22] | Drought stress identification |

| Stages-based MDFM [39] | Multimodal (UAV Multispectral, RGB & Thermal) | Best R²: 0.8065, rRMSE: 18.53% (Grain filling stage) [39] | Yield prediction & variety screening |

| VI+TP-RF [40] | Multimodal (Hyperspectral + Thermal Infrared) | Overall Accuracy: 89.47%, Kappa: 0.85 [40] | Drought-resistant variety classification |

| AI-based GLM Index [32] | Climate and Soil Moisture Data | Correlation with Upper Soil Moisture: 0.78 [32] | Meteorological drought forecasting |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Model Architectures

S-DNet Model Methodology

The S-DNet model was designed to overcome the lag and limitations of traditional drought monitoring methods. The core experimental workflow is as follows [38]: