Life Cycle Assessment for Controlled Environment Agriculture: A Decision Support Framework for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Design

This article provides a comprehensive framework for applying Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to support the design and operation of Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) systems, with a specific focus on applications...

Life Cycle Assessment for Controlled Environment Agriculture: A Decision Support Framework for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for applying Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to support the design and operation of Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) systems, with a specific focus on applications in pharmaceutical and biomedical research. It explores the foundational principles of LCA, details advanced methodological approaches including prospective LCA and digital integration, and addresses key challenges in data collection and system optimization. By synthesizing current research and presenting comparative case studies, this work aims to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the tools to make data-driven decisions that enhance the sustainability, resilience, and economic viability of CEA-based processes for producing plant-derived pharmaceuticals and research materials.

The Role of Life Cycle Assessment in Sustainable CEA for Pharmaceutical Research

Defining Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Its Core Principles for CEA Systems

FAQs: LCA Fundamentals for CEA Research

What is a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and why is it critical for CEA system design?

A Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a systematic, science-based method used to evaluate the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product's, process's, or service's life cycle, from raw material extraction ("cradle") to disposal ("grave") [1] [2]. For Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA), this means quantifying the footprint of every component, from the construction of the facility to the daily energy for lighting and climate control [3] [4]. It is a critical decision-support tool because it moves beyond assumptions, providing hard data to identify environmental hotspots, optimize resource efficiency, and improve the overall sustainability of CEA systems [1] [5].

What are the four standardized phases of an LCA according to ISO standards?

The ISO 14040 and 14044 standards define four interdependent phases for conducting an LCA [1] [2] [5]:

- Goal and Scope Definition: Defining the study's purpose, audience, and specifically, the functional unit and system boundaries.

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI): Compiling and quantifying all input and output data for the system throughout its life cycle.

- Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): Translating inventory data into potential environmental impact categories (e.g., climate change, water use, fossil resource depletion).

- Interpretation: Analyzing the results, drawing conclusions, identifying limitations, and providing recommendations.

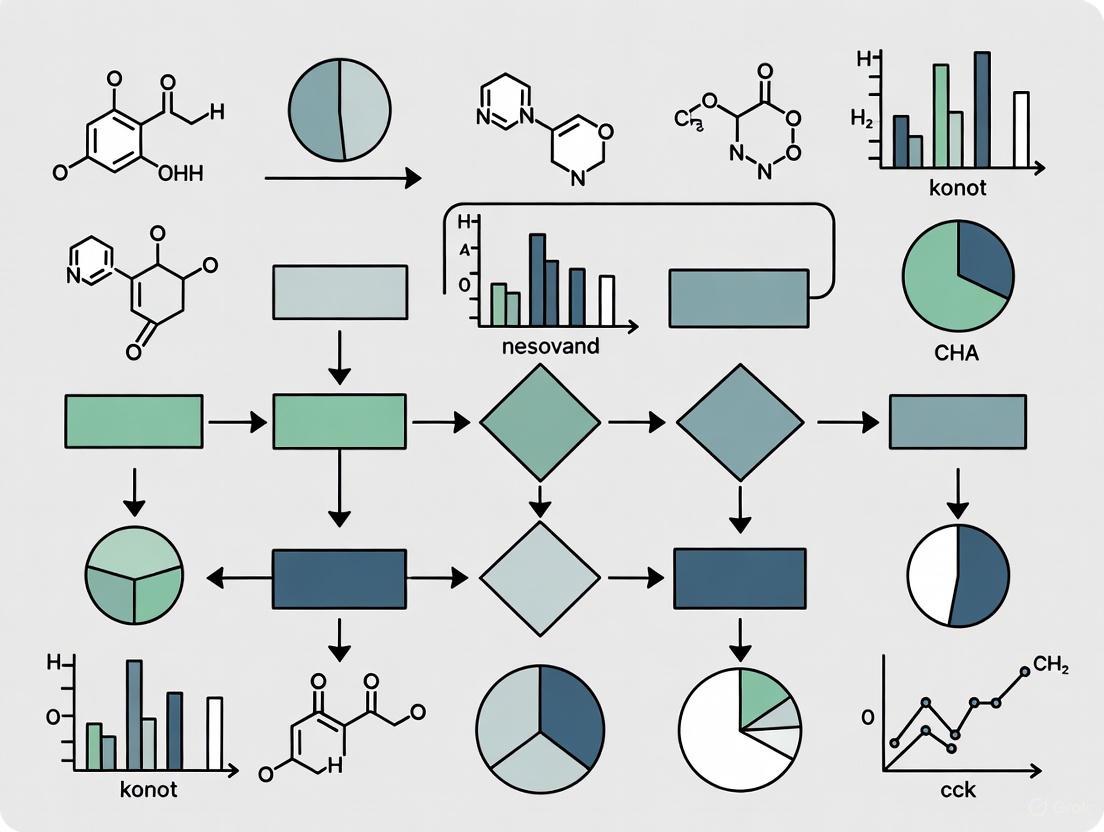

The diagram below illustrates how these phases interconnect in a typical LCA workflow:

What is the most significant environmental challenge for CEA identified through LCA?

Energy consumption and the associated carbon footprint are consistently identified as the most significant environmental challenges for CEA, particularly for indoor vertical farms that rely heavily on artificial lighting and climate control [3] [4] [6]. One study noted that the carbon footprints of indoor vertical farms can be 5.6–16.7 times greater than those of open-field agriculture [3]. Therefore, the use of low-carbon or renewable energy sources is paramount to realizing the potential sustainability benefits of CEA [4].

How do I choose the right life cycle model for my CEA study?

The choice of model depends on your goal and scope. The most common approaches are:

- Cradle-to-Grave: A full assessment from resource extraction to disposal of the CEA system and its products [2].

- Cradle-to-Gate: Assesses impacts only up to the point where the product (e.g., harvested lettuce) leaves the facility gate, excluding transport to consumer and end-of-life. This is often used for Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) [2] [5].

- Cradle-to-Cradle: A circular model where the "end-of-life" stage is a recycling process, making materials reusable for new products [2] [5].

The following diagram helps visualize the different system boundaries for these models:

Troubleshooting Common LCA Challenges in CEA Research

| Challenge | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Energy Impact | LCIA results show climate change impact is dominated by electricity consumption for lighting and HVAC [3] [6]. | Model integration of renewable energy (solar, wind) and energy-efficient technologies (advanced LEDs). Explore using waste heat from industrial co-location [3] [4]. |

| Data Collection Gaps | Incomplete or low-quality data for upstream materials (e.g., fertilizers, growing media, construction materials) weakens inventory. | Use industry-averaged data (Ecoinvent database) to fill gaps initially. Prioritize collecting primary data from suppliers for major impact contributors [2] [5]. |

| Defining Functional Unit | Study results are difficult to interpret or compare with other literature. | Clearly define a quantifiable functional unit relevant to the system's purpose, such as "1 kg of harvested lettuce" or "nutritional unit per square meter per year" [5] [6]. |

| Handling Multifunctionality | A single process (e.g., a co-located facility) provides multiple functions, making impact allocation complex. | Apply system expansion or allocation procedures based on physical (e.g., mass) or economic relationships, as guided by ISO 14044 [5]. |

Experimental Protocols: LCA of Lettuce Production

The following table summarizes a detailed LCA methodology for comparing the environmental performance of different lettuce cultivation methods, from open-field to fully controlled hydroponics [6].

Table: Experimental Protocol for CEA LCA Case Study

| Protocol Component | Description & Specification |

|---|---|

| 1. Goal Definition | To analyze and compare the environmental effects of growing romaine lettuce through open-field (OF), low-energy greenhouse (GH), and controlled environment hydroponics (CEH) farming [6]. |

| 2. Functional Unit | 1 kg of harvested lettuce. This allows for a standardized comparison of the environmental impact required to produce a defined quantity of market-ready product [6]. |

| 3. System Boundary | Cradle-to-Gate, including:• Included: Production and use of electricity, fertilizers, irrigation water, pesticides; energy for production and post-harvest transport to market [6].• Excluded: Retail, consumer preservation, preparation, consumption, and end-of-life disposal [6]. |

| 4. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) | Data Sources: • OF & GH: USDA statistics, university agricultural cost studies, scientific literature for yields, water, fertilizer, and pesticide use [6].• CEH: Primary data from commercial hydroponics companies and published literature for energy, water, and nutrient inputs [6].Key Flows Quantified: Energy, water, nutrients (N, P, K), pesticides, CO₂, N₂O, NH₃, and particulates [6]. |

| 5. Impact Assessment Method | ReCiPe 2016 (Hierarchist perspective), which provides both midpoint (e.g., climate change, freshwater eutrophication) and endpoint (damage to human health, ecosystems) impact categories [6]. |

| 6. Interpretation & Critical Review | Results are compared across the three systems. A sensitivity analysis is conducted on key parameters, such as fertilizer use rates in greenhouses and the source of electricity for CEH [6]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials for LCA

Table: Essential Components for a Comprehensive CEA LCA

| Item | Function in CEA LCA |

|---|---|

| Functional Unit | Defines the quantitative basis for comparison (e.g., 1 kg of produce). It is the cornerstone for ensuring all subsequent data collection and results are comparable and meaningful [5] [6]. |

| Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Database | Software and databases (e.g., Ecoinvent) that provide pre-compiled environmental data for common materials and processes (e.g., electricity grid mix, fertilizer production, transport), essential for filling data gaps [6] [7]. |

| Impact Assessment Method | A standardized set of characterized factors and models (e.g., ReCiPe, TRACI) that convert inventory data into specific environmental impact scores, such as Global Warming Potential (GWP) [6]. |

| Energy Flow Model | A detailed accounting of all energy inputs (kWh) into the CEA system, especially for artificial lighting and HVAC, which are typically the largest contributors to the carbon footprint [3] [6]. |

| Nutrient & Water Flow Model | Tracks the inputs and losses of water and fertilizers (N, P, K) to assess impacts related to resource depletion and eutrophication, highlighting opportunities for recirculation and efficiency [4] [6]. |

Why CEA? Addressing Pharmaceutical Industry Challenges with Controlled Cultivation

Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) represents a paradigm shift in modern farming, moving crop production into enclosed structures where every aspect of the environment is meticulously managed [8]. For the pharmaceutical industry, this method transcends agricultural innovation—it offers a robust solution to critical challenges in producing consistent, high-quality plant-based drugs and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). CEA's precise control over water supply, temperature, humidity, ventilation, light intensity/spectrum, CO2 concentration, and nutrient delivery enables unprecedented reliability in plant-based drug production [8]. Framed within a broader thesis on CEA system design decision support life cycle analysis research, this technical support center provides practical guidance for implementing CEA to overcome specific pharmaceutical industry challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How does CEA directly address impurity risk management in pharmaceutical crops?

CEA enables proactive impurity prevention through strict environmental control, significantly reducing the risk of genotoxic contaminants like nitrosamines that traditional outdoor cultivation cannot reliably prevent [9]. By controlling growing conditions and eliminating environmental contaminants, CEA minimizes the formation of harmful byproducts throughout the production lifecycle, ensuring cleaner raw materials for pharmaceutical applications.

2. What CEA system design offers optimal energy efficiency for pharmaceutical-grade production?

High-efficiency greenhouse designs balancing natural sunlight with supplemental LED lighting currently provide the most energy-conscious approach for pharmaceutical CEA [10] [11]. These systems significantly reduce energy consumption compared to fully indoor vertical farms while maintaining the environmental control necessary for consistent, high-quality pharmaceutical biomass production.

3. How does CEA ensure batch-to-batch consistency required for regulatory compliance?

CEA enables standardized production protocols through precise replication of environmental conditions, nutrient delivery, and growth cycles [8]. This controlled approach generates highly consistent plant material with uniform biochemical profiles, directly supporting the stringent batch consistency requirements of Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) regulations for pharmaceuticals [12].

4. What are the key considerations for integrating CEA into existing pharmaceutical quality systems?

Successful integration requires aligning CEA operational parameters with pharmaceutical quality systems, including equipment validation, environmental monitoring, documentation practices, and change control procedures [13] [9]. The controlled nature of CEA naturally supports quality risk management principles outlined in ICH Q9 when properly implemented and validated.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Biomass Composition Between Batches

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Inadequate Environmental Control: Verify and calibrate all sensors (light, CO2, temperature, humidity) monthly. Implement redundant monitoring systems for critical parameters.

- Nutrient Delivery Variance: Validate nutrient dosing equipment regularly. Conduct weekly nutrient solution analysis and adjust according to established protocols.

- Genetic Drift in Plant Stock: Implement strict plant stock management with regular genetic fidelity testing. Maintain backup stock from validated sources.

Experimental Validation Protocol:

- Establish baseline environmental parameters for optimal metabolite production

- Implement statistical process control (SPC) charts for all critical process parameters

- Conduct daily biochemical sampling during critical growth phases

- Correlate environmental data with biochemical profiles using multivariate analysis

- Adjust control parameters iteratively to minimize composition variance

Problem: Microbial Contamination in Closed-Loop Hydroponic Systems

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Biofilm Formation in Irrigation Lines: Implement regular system sanitization with pharmaceutical-grade sterilants. Use validated clean-in-place (CIP) procedures between batches.

- Inadequate Air Filtration: Upgrade to HEPA filtration systems with regular integrity testing. Maintain positive pressure in growth areas with proper air changes per hour.

- Contaminated Nutrient Stock: Implement strict raw material qualification procedures. Conduct microbial testing of all input materials prior to use.

Root Cause Investigation Workflow:

Problem: High Energy Consumption Impacting Production Costs

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Inefficient Climate Control: Implement thermal curtains, heat recovery ventilators, and high-efficiency HVAC systems designed specifically for CEA applications [11].

- Legacy Lighting Technology: Transition to spectrally-tuned LED systems with automated control strategies that respond to both plant needs and utility pricing signals.

- Poor Insulation and Envelope Design: Conduct thermal imaging assessment and upgrade building envelope to minimize energy losses.

Optimization Methodology:

- Conduct comprehensive energy audit identifying major consumption areas

- Implement energy monitoring with sub-metering on major systems

- Develop predictive control algorithms that optimize energy use against production outcomes

- Integrate renewable energy sources where feasible

- Establish key performance indicators (KPIs) for energy use per unit of pharmaceutical biomass

Quantitative Analysis of CEA Advantages

Table 1: Resource Efficiency Comparison - CEA vs. Traditional Cultivation

| Parameter | Traditional Agriculture | Controlled Environment Agriculture | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Usage | Baseline | 4.5-16% of traditional [3] | 6-22x more efficient |

| Land Requirement | Baseline | 10-100x higher yields per unit area [3] | 10-100x more efficient |

| Production Consistency | Weather-dependent variations | Year-round consistent production [14] [8] | Predictable output |

| Pesticide Requirement | Conventional usage | Significantly reduced [14] [8] | Minimized chemical residues |

Table 2: CEA System Comparative Analysis for Pharmaceutical Applications

| System Type | Initial Investment | Operational Costs | Control Level | Suitable Pharma Crops |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced Greenhouse | Medium | Medium-High | High | Cannabis, Vinca, Foxglove |

| Indoor Vertical Farm | High | High | Very High | High-value botanicals, Plant-cell cultures |

| Hydroponic Greenhouse | Medium | Medium | Medium-High | Leafy medicinal plants |

| Container Systems | Low-Medium | Medium | High | Research-scale production, Rare botanicals |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for CEA Pharmaceutical Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application in CEA Pharma Research |

|---|---|---|

| bioCHARGE with bioCORE | Activated beneficial microbiology | Enhances plant immune response and nutrient uptake in controlled environments [8] |

| Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) | Microbial growth medium | Sterility testing and contamination screening [12] |

| Selective Mycoplasma Media (PPLO) | Specialized contamination detection | Identification of filterable microorganisms like Acholeplasma laidlawii [12] |

| Nutrient Solution Formulations | Plant growth support | Precise control of mineral nutrition for consistent metabolite production |

| RNA Sequencing Kits | Gene expression analysis | Molecular profiling of plant responses to controlled environments |

| HPLC/MS Reference Standards | Metabolite quantification | Quality control and standardization of active compound levels |

CEA System Integration Framework for Pharmaceutical Quality

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Light Spectrum Optimization for Secondary Metabolite Production

Objective: Determine optimal light spectra for maximizing target compound production in medicinal plants.

Methodology:

- Establish plant groups under different spectral treatments (Blue: 450nm, Red: 660nm, Far-red: 730nm, White full spectrum)

- Maintain all other environmental parameters constant (temperature: 22±0.5°C, humidity: 65±2%, CO2: 1000±50 ppm)

- Harvest plant material at consistent developmental stages

- Extract and quantify target compounds using validated HPLC-UV/MS methods

- Analyze transcriptional regulation of biosynthetic pathway genes via RT-qPCR

Data Analysis: Employ response surface methodology to model interaction effects between light spectra and other environmental parameters on metabolite accumulation.

Protocol 2: Process Validation for GMP Compliance

Objective: Establish validated CEA processes meeting pharmaceutical GMP requirements.

Methodology:

- Define Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) and Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs)

- Conduct risk assessment using Failure Mode Effects Analysis (FMEA)

- Execute process qualification batches following ICH Q7 guidelines [12]

- Establish statistical process control limits for all CPPs

- Document all deviations and implement corrective actions within quality system

Regulatory Considerations: FDA does not mandate a specific number of validation batches [12]; focus instead on scientific rationale and statistical confidence in process capability.

Integrating CEA within pharmaceutical cultivation represents a transformative approach to addressing longstanding challenges in plant-based drug production. Through precise environmental control, robust monitoring systems, and continuous improvement informed by life cycle analysis, CEA enables unprecedented consistency, quality, and reliability in pharmaceutical biomass production. The troubleshooting guides, experimental protocols, and analytical frameworks provided in this technical support center offer researchers and pharmaceutical professionals practical tools to leverage CEA technologies effectively, ultimately supporting the development of more consistent, safe, and effective plant-derived medicines.

Troubleshooting Guides

High Energy Intensity in Climate Control

Problem: Your CEA facility is experiencing unexpectedly high energy consumption from HVAC (Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning) systems, threatening operational cost targets and environmental performance goals.

Solution: Implement a layered diagnostic approach focusing on system optimization and integration.

Step 1: Baseline Energy Performance

- Action: Conduct a one-week audit to measure the Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) of your facility. Compare against baseline nZEB (nearly Zero-Energy Building) standards, which aim for very low energy demand supplemented by high-efficiency systems [15].

- Data Required: Total facility energy draw (kWh) and dedicated HVAC energy draw (kWh).

Step 2: System Calibration Check

- Action: Verify the calibration of all environmental sensors (temperature, humidity, CO₂). Compare sensor readings against certified portable equipment.

- Acceptable Variance: ±0.5°C for temperature; ±5% for relative humidity.

Step 3: Operational Pattern Analysis

- Action: Analyze HVAC setpoints against external climatic data. Identify opportunities for using passive thermal buffering or economizer cycles during cooler hours to reduce mechanical load [15].

- Tool: Use AI-driven predictive models to simulate and optimize setpoints for energy minimization while maintaining plant health [15].

Step 4: Integrated System Diagnosis

- Action: If high energy load persists, the issue may be systemic. Refer to the systematic diagnostic workflow below to identify the root cause.

Inaccurate Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Results

Problem: Your LCA model for a new CEA system is producing inconsistent or outlier results for key metrics like Global Warming Potential (GWP) and Water Footprint (WF), making it difficult to validate the resource efficiency claims.

Solution: Methodically review the LCA's boundary conditions and inventory data quality.

Step 1: Scoping and Boundary Audit

- Action: Reconcile the goal and scope of your study with the ISO 14044 standard. Explicitly state whether you are using a "cradle-to-gate" or "cradle-to-grave" boundary. Inconsistent scoping is a primary source of result variability [16].

- Check: Ensure credits for avoided GHG emissions in upstream processes are clearly documented, as these greatly influence GWP results [16].

Step 2: Critical Inventory Data Verification

- Action: Cross-reference your primary data for high-impact components. Use the table below to guide your verification.

Step 3: Sensitivity and Uncertainty Analysis

- Action: Perform a sensitivity analysis on key parameters, such as the regional electricity mix used for manufacturing or facility operation. The carbon intensity of the grid electricity used is a major driver of GWP for electrically-intensive CEA systems [17] [16].

- Tool: Employ Monte Carlo simulation to quantify uncertainty in your final results.

Step 4: Peer Benchmarking

- Action: Compare your results against published values from studies with similar boundaries and technology focus. Note the expected ranges for different system types, as shown in the table below.

The following table summarizes key LCA metrics for various energy systems relevant to CEA, highlighting the trade-offs and benchmarks.

Table 1: Life Cycle Assessment Metrics for Energy and Production Systems

| System Technology | Global Warming Potential (GWP) | Energy Performance (EP) | Water Consumption (WF) | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green H2 (Solar PV) | Low | High | Variable | WF highly dependent on regional water scarcity and cooling technologies [16]. |

| Green H2 (Wind) | Low | High | Lower than PV | Generally offers superior EP and lower WF compared to solar-based routes [16]. |

| Grey H2 (Fossil SMR) | High | Moderate | High | Conventional method with significant GHG emissions [16]. |

| AI-Optimized EV Propulsion | -- | ~6% peak power increase | -- | Example of AI-driven efficiency gain in a related field [18]. |

| Electrolyzer Manufacturing | -- | -- | -- | Significant GWP from material use (e.g., steel, platinum, nickel) [17]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can we quantitatively allocate resources in a multi-stakeholder CEA project to ensure both equity and efficiency?

A1: Advanced economic models like the Stackelberg game can be applied. This hierarchical, multi-level game theory model is effective for formulating optimal pricing and energy strategies where multiple entities (e.g., utility company, community aggregators, end-users) strive to maximize their own utility [19]. Research on provincial carbon emission allowance allocation has successfully employed this method, generating Pareto-optimal solutions that achieve a trade-off between equity (Gini coefficient 0.29–0.33) and efficiency (Malmquist index 1.010–1.015) [20]. This provides a quantitative framework for fair and efficient resource distribution in complex CEA systems.

Q2: What is the most robust methodology for measuring the real-world energy efficiency of a new CEA subsystem rather than just its lab performance?

A2: You should adopt a two-tiered testing protocol that combines standardized laboratory cycles with real-world validation.

- Tier 1: Standardized Laboratory Testing: Use a recognized drive cycle or duty cycle test, such as the Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Procedure (WLTP), on a chassis dynamometer or equivalent test rig. WLTP incorporates more stringent and dynamic conditions than its predecessors, providing a more realistic baseline than simpler tests [21].

- Tier 2: Real-World Performance Validation: Complement lab tests with a Real Driving Emissions (RDE)-inspired protocol. Use Portable Emissions Measurement Systems (PEMS) or equivalent portable power monitors to collect performance data under actual operating conditions in your facility. This captures variations that lab tests cannot simulate, ensuring that reported efficiency aligns with real-world operation [21].

Q3: We are designing a new CEA facility and need to minimize its lifecycle carbon footprint. What is the single most impactful design decision?

A3: The most impactful decision is the choice of the energy source for both construction and operation. Life Cycle Assessment studies consistently show that systems powered by renewable energy sources (like wind and photovoltaic) provide a significantly lower Global Warming Potential (GWP) and higher Energy Performance (EP) compared to conventional fossil-based pathways [16]. Furthermore, integrating AI-powered digital twins from the design phase allows for dynamic energy optimization, predictive system management, and renewable energy integration tailored to your specific climatic context, which sustains low operational carbon emissions over the building's entire lifecycle [15].

Q4: How can Artificial Intelligence (AI) concretely help in managing the resource-efficiency vs. energy-intensity trade-off?

A4: AI provides several concrete, high-ROI applications:

- Predictive Thermal Control: As demonstrated by ZF's TempAI in electric vehicles, machine learning models can boost temperature management forecast accuracy by over 15%, unlocking approximately 6% more peak power from the same hardware. This directly translates to doing more work with less energy [18].

- AI-Powered Digital Twins: These virtual replicas of your physical CEA system enable real-time monitoring, predictive analytics, anomaly detection, and adaptive operational strategies. This allows for continuous, dynamic optimization of energy consumption against resource output, enhancing overall performance and resilience [15].

- Accelerated R&D: AI-enabled platforms can drastically shorten development cycles for critical components, such as optimizing battery thermal management or new material selection, from months to days, ensuring that more efficient technologies are deployed faster [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for CEA System Life Cycle Analysis Research

| Item Name | Function / Application | Critical Parameters & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Database | A comprehensive inventory of energy and material inputs/outputs for all processes in the product system. It is the foundational data for any LCA model [17]. | Must be region-specific and technology-specific. Critical for assessing GWP and Abiotic Resource Depletion (ARD). |

| Portable Emissions Measurement System (PEMS) | Portable equipment for measuring real-world energy consumption and emissions (e.g., CO₂) from CEA subsystems or entire facilities [21]. | Essential for validating lab results and conducting RDE-style testing. |

| Stackelberg Game Theory Model | A computational framework to model and optimize hierarchical decision-making in multi-entity resource allocation problems, such as energy sharing in smart grids [19]. | Used to find equilibria between equity and efficiency in allocation schemes. |

| Digital Twin Platform | A virtual, AI-powered model of a physical CEA system that is continuously updated with sensor data. Used for simulation, predictive control, and anomaly detection [15]. | Key performance indicators include model accuracy and predictive horizon. |

| Critical Raw Materials (CRMs) | A defined set of materials (e.g., platinum, nickel) deemed critical due to supply risk and economic importance. Their use in system manufacturing (e.g., in electrolyzers) must be tracked for environmental impact [17]. | High GWP is often associated with the use of CRMs in manufacturing phases. |

Experimental Protocol: Life Cycle Assessment for CEA System Components

This protocol outlines a standardized methodology for conducting a cradle-to-gate Life Cycle Assessment of a key CEA subsystem, such as an environmental control unit.

1. Goal and Scope Definition

- Objective: To quantify the environmental impacts of manufacturing and operating the subsystem.

- System Boundary: Cradle-to-Gate with optional operational extension. Includes raw material extraction, material processing, manufacturing, and assembly. Transport to the facility is included. Use-phase and end-of-life may be analyzed separately.

- Functional Unit: Define as "Providing 1 kWh of cooling capacity over the operational lifetime of the unit." This allows for comparison with alternative technologies.

2. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Analysis

- Data Collection: Collect primary data from manufacturing partners on material and energy inputs. For background data (e.g., electricity mix, material production), use secondary data from reputable commercial LCI databases (e.g., Ecoinvent, GREET).

- Critical Inventory: Pay special attention to:

- Mass of all metals and plastics used.

- Energy consumption during the manufacturing phase.

- Mass and type of any refrigerants.

- Use of any Critical Raw Materials (CRMs) like platinum or nickel [17].

3. Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

- Impact Categories: Calculate the environmental impacts for the following mandatory categories:

- Calculation Method: Use a established LCIA method, such as ReCiPe or CML, within an LCA software package (e.g., OpenLCA, SimaPro).

4. Interpretation and Sensitivity Analysis

- Hotspot Identification: Identify which components or processes contribute most significantly to each impact category (e.g., compressor manufacturing, PCB assembly).

- Sensitivity Check: Test the sensitivity of your results to key assumptions, most importantly the regional electricity grid mix used in manufacturing, as this heavily influences GWP results [17] [16].

- Peer Comparison: Benchmark your results against published LCAs of similar subsystems, ensuring boundaries and functional units are consistent.

The logical workflow for this LCA study is outlined below.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on LCA System Boundaries

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a cradle-to-gate and a cradle-to-grave assessment for a pharmaceutical product?

- A1: The difference lies in the stages of the product's life cycle that are included in the analysis.

- A cradle-to-gate assessment analyzes the environmental impacts from the extraction of raw materials ("cradle") up to the point where the finished Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) or drug product leaves the factory gate ("gate"). This boundary is often used for business-to-business environmental reporting and excludes impacts from product distribution, use, and disposal [22] [23].

- A cradle-to-grave assessment is a full life cycle assessment. It includes all stages from cradle-to-gate, plus the product's distribution, use by patients, and end-of-life disposal or fate in the environment. This comprehensive boundary is essential for understanding the complete environmental footprint of a drug, including impacts from hospital energy use or patient waste [24].

Q2: Why is defining the system boundary a critical and challenging step in a Pharmaceutical Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)?

- A2: Defining the system boundary is critical because it directly determines which processes and environmental impacts are included in the final result. This makes comparisons between different LCA studies extremely difficult if their boundaries are not aligned [22].

- Challenges include:

- Data Availability: A cradle-to-grave analysis requires data on complex stages like patient administration and drug metabolism, which is often scarce or confidential [24].

- Allocation of Impacts: It can be difficult to fairly allocate environmental impacts, especially in multi-product manufacturing facilities or when dealing with complex waste streams.

- Methodological Choices: Different practitioners may set boundaries differently, leading to contradictory conclusions for the same product. For instance, one study might show a material is better, while another concludes the opposite, purely due to boundary settings [22].

- Challenges include:

Q3: Our LCA results are being questioned because they differ from a similar study. Could the system boundary be the cause?

- A3: Yes, this is a common issue. Without standardized Product Category Rules (PCRs) for pharmaceuticals, individual LCA studies can define their boundaries differently, making direct comparisons invalid [22]. To troubleshoot:

- Audit the Boundary: Create a detailed map of every process included in your study and compare it directly with the other study.

- Identify Key Omissions/Inclusions: Look for major discrepancies, such as one study excluding the production of a key solvent or the energy for sterile filling, while the other includes it.

- Check Downstream Boundaries: A major difference often lies in whether the "use" phase is included. For example, the environmental impact of an injectable drug would be significantly higher if the study includes the energy used for refrigeration during distribution and in the hospital [24].

Q4: What are the most commonly overlooked processes when setting a cradle-to-gate boundary for an API?

- A4: Even within cradle-to-gate, processes with significant environmental footprints can be missed.

- Upstream Chemical Synthesis: The complex supply chain for chemical precursors and solvents. The environmental burden of these "raw materials" can constitute over three-quarters of a product's total carbon footprint [22].

- Catalyst and Reagent Production: The energy and resource-intensive production of specialized catalysts and reagents used in synthesis.

- Waste Treatment: The disposal and treatment of chemical waste generated during the manufacturing process, including solvents and by-products [25].

- Facility-Level Energy: Energy consumption from non-production activities like quality control (QC) labs, HVAC systems, and cleaning-in-place (CIP) processes [25].

Quantitative Data on Pharmaceutical LCA

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent LCA studies, illustrating the range of environmental impacts and the influence of system boundaries.

Table 1: Cradle-to-Gate Greenhouse Gas Emissions for Select Pharmaceuticals

| Drug Category | Example Drug | Cradle-to-Gate GHG Emissions (kg CO₂-eq) | Key Contributing Factors & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anesthetic (Injectable) | Succinylcholine | 11 [23] | Lower synthesis steps; represents the lower end of the impact spectrum. |

| Anesthetic (Injectable) | Dexmedetomidine | 3,000 [23] | High number of synthesis steps; represents the higher end of the impact spectrum. |

| Common API | Ibuprofen | Reported in multiple studies [24] | Well-studied; impact varies with manufacturing efficiency and energy source. |

| Common API | Acetaminophen | Reported in 3 studies [24] | Highlights variability between different LCA studies. |

| Inhalers | Pressurized MDI (pMDI) | High [24] | Propellant gases are potent greenhouse gases; significantly higher impact than DPIs. |

| Inhalers | Dry Powder Inhaler (DPI) | Lower [24] | Impact primarily from device materials and API; lower than pMDIs. |

| Monoclonal Antibodies | Various | Highly Energy Intensive [24] | Cell culture, purification, and sterile filtration are major energy consumers. |

Table 2: Correlation Between Drug Properties and Environmental Impact

| Factor | Observed Correlation | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Synthesis Steps | Positive correlation with GHG emissions; more steps typically lead to higher impacts [23]. | [23] |

| Drug Format | Injectable drugs generally have a higher carbon footprint than oral drugs due to sterilization, packaging, and cold chain requirements [24]. | [24] |

| Market Sales Volume | High-sales disease areas (e.g., Oncology, Cardiovascular) represent a significant portion of the pharmaceutical market's total environmental impact, though they are under-studied by LCA [24]. | [24] |

Experimental Protocols for LCA System Boundary Definition

Protocol A: Defining a Cradle-to-Gate Boundary for a Small Molecule API

Objective: To establish a consistent and comprehensive cradle-to-gate system boundary for the LCA of a small molecule Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API).

Methodology:

- Goal Definition: Clearly state the goal of the LCA (e.g., internal process improvement, supplier selection, or environmental product declaration).

- Process Mapping: Create a detailed process flow diagram of the entire API synthesis, from raw material inputs to the final purified API. This includes all reaction steps, separations, purifications, and waste streams.

- Boundary Delineation:

- Include: All raw material extraction and production (chemicals, solvents, catalysts). All energy and water inputs for chemical reactions, purification (e.g., distillation, crystallization), and drying. Transportation of materials between your suppliers. Direct emissions from the manufacturing process. Packaging for the final API.

- Exclude: Capital goods (e.g., reactor vessels, building infrastructure). Human labor and overhead activities (e.g., QC testing, administrative functions) unless their impact is significant. Transportation of the API to the formulation facility. The drug product formulation, packaging, distribution, use, and disposal.

- Data Collection: Collect primary data on material and energy consumption from your manufacturing records. For upstream processes (e.g., solvent production), use secondary data from commercial LCA databases (e.g., ecoinvent).

- Allocation: If the facility produces multiple products, define a clear allocation method (e.g., by mass, economic value, or energy content) to partition environmental impacts.

Protocol B: Extending to a Cradle-to-Grave Boundary for a Finished Drug Product

Objective: To expand a cradle-to-gate LCA to a full cradle-to-grave assessment, capturing the complete life cycle impact of a finished pharmaceutical product.

Methodology:

- Start with Cradle-to-Gate: Complete Protocol A for the API and perform a separate cradle-to-gate assessment for the drug product formulation (e.g., tableting, filling into vials).

- Add Downstream Processes:

- Distribution: Model transportation from the manufacturing plant to warehouses, pharmacies, and hospitals. Include energy for refrigeration if required (cold chain) [24].

- Use Phase:

- For injectable drugs, model the energy consumption of hospital refrigerators and the production of ancillary materials like syringes, infusion bags, and needles [24].

- For inhalers, model the release of propellant gases into the atmosphere during patient use [24].

- For any drug, consider patient travel to collect prescriptions if relevant to the study's goal.

- End-of-Life:

- Model the disposal of unused drugs and packaging (landfilling, incineration).

- Account for the fate of metabolized APIs excreted by patients into wastewater systems, which can have toxicity impacts on ecosystems [24].

- Manage Data Uncertainty: Acknowledge and document the higher uncertainty associated with data for the use and end-of-life phases. Use sensitivity analysis to test how these uncertainties affect the overall results.

System Boundary Decision Diagram

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical process for defining an LCA system boundary in the pharmaceutical context.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LCA

Table 3: Essential Tools and Data Sources for Pharmaceutical LCA

| Tool / Resource Name | Function in LCA Research | Key Features / Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PMI-LCA Tool (ACS GCI) | High-level estimator of Process Mass Intensity (PMI) and environmental impacts for API synthesis [26]. | Customizable for linear/convergent processes; uses ecoinvent LCIA data; supports greener route selection. |

| ecoinvent Database | Provides Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) data for background processes (e.g., electricity, chemical production, transport) [26]. | Critical for modeling upstream supply chains; widely recognized and used in LCA studies. |

| Pharmaceutical LCA Consortium | Industry group developing Product Category Rules (PCRs) to standardize LCA methodologies for pharmaceuticals [22]. | Aims to ensure comparability between studies by defining common system boundaries and rules. |

| Process Modeling Software (e.g., Aspen Plus) | Used for scale-up and process design based on lab-scale synthesis data from patents/literature [23]. | Generates cradle-to-gate LCI data when primary industrial data is unavailable or confidential. |

| Green Chemistry Principles | A framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate hazardous substances [25]. | Guides process optimization (e.g., solvent selection, catalyst use) to minimize environmental impacts at the source. |

Key Environmental Impact Categories for Assessing CEA in Biomedical Contexts

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1.1: What are the key environmental impact categories used in Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for biomedical CEA systems? The key environmental impact categories for assessing Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) in biomedical contexts are derived from standardized LCA methodologies such as the EN15804 standard. These categories provide a comprehensive framework for quantifying environmental impacts from cradle to grave. The most critical categories for biomedical CEA systems include Global Warming Potential (climate change), measured in kg CO₂-equivalents; Freshwater, Marine, and Terrestrial Eutrophication, measured in kg PO₄-equivalents, kg N-equivalents, and mol N-equivalents respectively; Acidification, measured in kg mol H+; Human Toxicity (both cancer and non-cancer effects), measured in Comparative Toxic Units for humans (CTUh); and Freshwater Ecotoxicity, measured in Comparative Toxic Units for ecosystems (CTUe) [27]. Additional crucial categories are Abiotic Resource Depletion (for both minerals/metals and fossil fuels), Water Use (in m³ world eq. deprived), and Land Use [27]. These impact categories are essential for performing a holistic environmental assessment of biomedical CEA systems, allowing researchers to identify environmental hotspots and prioritize mitigation strategies.

FAQ 1.2: How do I interpret the results from different environmental impact categories when they conflict? Conflicting results between impact categories are common in LCA, requiring a multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) approach. For instance, a CEA system design might reduce global warming potential but increase freshwater ecotoxicity due to different material choices or energy sources. To resolve this, you must define decision priorities aligned with your research or organizational goals. Use structured decision-making frameworks like the Comprehensive Environmental Assessment (CEA) process, which employs collective judgment procedures such as the Nominal Group Technique (NGT) to weigh the relative importance of various impacts transparently [28]. Furthermore, you can employ a single aggregated metric like the Environmental Cost Indicator (ECI) to compare trade-offs, though this should be done with caution and with clear communication of the underlying value choices [27].

FAQ 1.3: What are the most common sources of uncertainty in LCA for biomedical CEA, and how can they be addressed? The leading limitation reported in LCA studies, particularly in healthcare and biomedical applications, is the lack of primary data, often necessitating estimations or approximations of emissions [29]. Other significant sources of uncertainty include:

- Inventory Data Gaps: Missing or incomplete life cycle inventory data for specific medical devices, reagents, or biomaterials.

- Scenario and Model Uncertainty: Uncertainty arising from choices in system boundaries, allocation methods, and future projections.

- Technological Variability: Differences in equipment efficiency, facility operations, and clinical protocols.

To address these uncertainties, you should:

- Conduct Sensitivity and Uncertainty Analysis: Systematically test how sensitive your results are to changes in key parameters and model the range of possible outcomes [30].

- Use Predictive Modeling: Integrate machine learning techniques, such as Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), which can model impacts dynamically and quantify uncertainty through confidence intervals [31].

- Develop Healthcare-Specific LCI Databases: Advocate for and contribute to the development of life cycle inventory databases specific to healthcare and biomedical processes to improve data quality [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 2.1: High Global Warming Potential in CEA System LCA A high carbon footprint is often the most significant environmental disadvantage for CEA systems, primarily driven by energy-intensive artificial lighting and temperature control [4].

Recommended Action Plan:

- Diagnose the Source: Use the LCA results to isolate the stage in the life cycle contributing most to GHG emissions. This is typically the operational energy use phase [3].

- Model Energy Efficiency Interventions:

- Transition to Low-Carbon Energy: Model the impact of sourcing electricity from renewable energy (e.g., solar, geothermal) or utilizing waste heat from co-located industrial processes, such as data centers or combined heat and power plants [3] [4]. One study suggests that with sufficient green energy, CEA systems could largely negate most GHG emissions associated with conventional farming [4].

Issue 2.2: Managing Trade-offs Between Toxicity and Resource Depletion Selecting materials for CEA infrastructure (e.g., growth modules, sensors) or single-use biomaterials might reduce one environmental impact while increasing another.

Recommended Action Plan:

- Characterize Trade-offs Quantitatively: Use your LCA software to model different material choices. For example, compare the human toxicity and abiotic resource depletion of different plastics or metals used in bioreactors or hydroponic systems.

- Apply a Circular Economy Framework: Investigate opportunities for using recycled materials (which have lower abiotic resource depletion) and ensure that end-of-life disposal pathways for toxic materials are properly accounted for, such as recycling or safe treatment of hazardous waste [27] [4].

- Utilize Multi-Objective Optimization: Employ optimization algorithms like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to balance conflicting objectives, such as minimizing toxicity, resource depletion, and cost simultaneously. This approach can identify a "Pareto front" of optimal solutions [31].

Key Environmental Impact Categories and Data

Table 1: Core Environmental Impact Categories for CEA Assessment [27]

| Impact Category / Indicator | Unit | Description & Relevance to Biomedical CEA |

|---|---|---|

| Climate Change (Global Warming) | kg CO₂-eq | Potential for global warming from GHG emissions. Critical due to high energy demands of CEA climate control and lighting. |

| Human Toxicity (cancer/non-cancer) | CTUh | Impact of toxic substances on human health. Vital for assessing leaching from plastics, chemical disinfectants, or emissions from incineration of biomedical waste. |

| Freshwater Ecotoxicity | CTUe | Impact of toxic substances on freshwater organisms. Important for evaluating potential nutrient runoff or chemical discharges from CEA operations. |

| Eutrophication (Freshwater) | kg PO₄-eq | Enrichment of water with nutrients, leading to algal blooms. Relevant for managing fertilizer and nutrient solutions in hydroponic systems. |

| Eutrophication (Marine) | kg N-eq | Enrichment of marine ecosystems with nitrogen. |

| Acidification | kg mol H+ | Potential acidification of soils and water from gases like SOₓ and NOₓ. Linked to energy production for CEA facilities. |

| Abiotic Resource Depletion (fossil) | MJ, net calorific | Depletion of fossil fuel resources. Directly tied to the energy consumption of the CEA facility. |

| Water Use | m³ world eq. deprived | Relative water consumption, factoring in regional water scarcity. A key metric as CEA can reduce water use by 85-99% compared to conventional agriculture [4]. |

| Ozone Depletion | kg CFC-11-eq | Destruction of the stratospheric ozone layer. |

Table 2: Additional Parameters for Resource Use and Waste [27]

| Parameter / Indicator | Unit | Relevance to Biomedical CEA |

|---|---|---|

| Use of Secondary Material | kg | Promotes a circular economy by using recycled materials for CEA infrastructure. |

| Hazardous Waste Disposed | kg | Essential for quantifying waste from contaminated growth media, chemical reagents, or decommissioned equipment. |

| Non-Hazardous Waste Disposed | kg | General waste from plant biomass and packaging. |

| Materials for Recycling | kg | Tracks materials diverted from landfills, important for sustainability reporting. |

Experimental Protocol: Conducting an LCA for a Biomedical CEA Process

Title: Gate-to-Gate Life Cycle Assessment of a Pilot-Scale Biopharmaceutical Plant Growth Unit.

Objective: To quantify the environmental impacts of a single production cycle of a model plant-based biopharmaceutical in a controlled environment.

Methodology:

- Goal and Scope Definition:

- Functional Unit: Define as "1 gram of purified recombinant protein produced in Nicotiana benthamiana plants."

- System Boundary: A gate-to-gate approach, focusing on the CEA facility operations. This includes: (A) Plant growth (seeding to harvest), (B) Biomass processing and protein purification, and (C) Wastewater and solid waste treatment [30].

Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Data Collection: Collect foreground data for one production cycle.

- Inputs: Quantify electricity (kWh) for LEDs, HVAC, and lab equipment; natural gas (MJ) for heating; purified water (L); nutrient solution (kg) of N, P, K; CO₂ for enrichment (kg); growth substrate (kg); and single-use bioprocessing materials (e.g., filters, chromatography resins).

- Outputs: Measure fresh plant biomass (kg); product (g); wastewater (L) and its BOD/COD/N/P content; and solid waste, categorizing as hazardous (e.g., contaminated plastics) and non-hazardous (plant debris) [30] [27].

- Data Sources: Use primary measurements from the pilot facility. For background data (e.g., electricity grid mix, chemical production), use established databases like Ecoinvent.

Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA):

- Software: Use LCIA software such as SimaPro.

- Method: Select the CML-IA impact assessment method to calculate the impact categories listed in Table 1 [30].

Interpretation and Sensitivity Analysis:

- Identify the life cycle stages and inputs that are the primary contributors to each impact category (e.g., electricity for lighting contributing most to Global Warming).

- Perform a sensitivity analysis on key parameters, such as the source of electricity (grid vs. solar) or the efficiency of the protein purification step, to test the robustness of the conclusions [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Material Solutions

Table 3: Key Materials for CEA Life Cycle Inventory Analysis

| Item | Function in Experiment/Assessment |

|---|---|

| SimaPro Software (v9.1+) | Industry-standard LCA software used to model the product system, calculate impact categories using methods like CML-IA, and perform sensitivity analyses [30]. |

| Ecoinvent Database | Extensive background life cycle inventory database providing validated data for materials, energy, and processes, essential for modeling upstream and downstream impacts [30]. |

| Data Loggers & Smart Meters | Critical for collecting real-time, primary foreground data on electricity, water, and gas consumption within the CEA facility to build a robust inventory. |

| Nutrient Film Technique (NFT) Hydroponic System | A widely used hydroponic system suitable for shallow-rooted, short-term crops like many biomaterial-producing plants, with defined inputs for water and nutrients [3]. |

| LCIA Impact Method (CML-IA, ReCiPe) | A standardized set of characterization models that translate inventory data (e.g., 1 kg of CO₂ emitted) into impact category scores (e.g., contribution to climate change) [30] [27]. |

LCA Workflow and Decision Support Diagram

Implementing LCA in CEA: From Data Collection to Decision Support

A Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) is the data collection phase of a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), a systematic method for assessing the environmental impacts of a product or service across its entire life cycle [2] [33]. The LCI involves compiling and quantifying the inputs (e.g., energy, water, materials) and outputs (e.g., emissions, waste) for a product's system throughout its "life"—from raw material extraction to final disposal [2]. For researchers in Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA) system design, building a robust LCI is foundational for generating reliable data to support environmentally informed decisions.

The process is structured within a framework defined by international standards, primarily ISO 14040 and 14044, which outline four key phases [2] [33]:

- Goal and Scope Definition: Defining the purpose and system boundaries of the study.

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI): The focus of this guide—collecting data on energy, water, and material flows.

- Life Cycle Impact Assessment: Evaluating the potential environmental impacts based on the LCI data.

- Interpretation: Analyzing the results to make informed decisions.

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for compiling a Life Cycle Inventory.

Methodologies for Sourcing LCI Data

Sourcing accurate data is the most critical step in building a representative LCI. The methodologies below outline protocols for gathering data on core components.

Experimental Protocol for Data Collection

The general workflow involves defining the system, identifying unit processes, and systematically collecting data.

1. Goal and Scope Definition:

- Objective: Clearly state the intended application of the LCI, the reasons for conducting it, the intended audience, and whether the results will be used for comparative assertions [2].

- System Boundaries: Define the processes to be included. Common models include:

- Cradle-to-Grave: Includes all stages from raw material extraction to disposal [2].

- Cradle-to-Gate: Includes stages from raw material extraction up to the factory gate (before transport to the consumer) [2].

- Cradle-to-Cradle: A closed-loop model where the product's end-of-life is a recycling process into a new product [2].

- Functional Unit: Define a quantifiable performance characteristic of the product system that all data will be normalized to (e.g., "per 1 kg of produce" or "per square meter of growing area per year"). This ensures fair comparisons.

2. Data Collection Plan and Identification of Data Sources: Data can be sourced from a combination of the following, categorized by their origin and application.

Table: LCI Data Sources and Applications

| Data Category | Description | Common Sources in CEA Context | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Data [33] | Site-specific, measured data collected directly from processes within the defined system boundary. | - Electricity and natural gas bills from utilities.- Direct metering of water consumption.- Laboratory analysis of process emissions.- Supplier-specific data on nutrient solutions, growth media, and equipment. | - Can be time-consuming and costly to collect.- Requires access to operational facilities and suppliers. |

| Secondary Data [33] | Generic, non-site-specific data from literature, industry averages, or life cycle inventory databases. | - Ecoinvent database, U.S. LCI database.- Industry reports on material production (e.g., steel, plastics, glass).- Government publications on regional energy grid mixes. | - May not perfectly represent the specific technology or region of interest.- Can be outdated. |

| Modeled/Estimated Data [34] | Data derived through calculations, stoichiometry, or mass/energy balance when direct measurement is impossible. | - Calculating embodied energy of a component based on its mass and material composition.- Estimating transportation impacts based on distance and mode of transport. | - Introduces uncertainty and requires careful documentation of assumptions. |

3. Data Collection and Calculation:

- For each unit process within the system boundary, collect data on all relevant inputs and outputs.

- All data must be calculated and normalized concerning the defined functional unit.

Table: Quantitative Data Requirements for a CEA System LCI

| Life Cycle Stage | Energy Inputs | Water Inputs | Material Inputs | Emissions/Waste Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Material Extraction | Electricity for mining equipment | Water used in material processing | Mass of iron ore, bauxite, fossil fuels | CO2 from fuel combustion, mining tailings |

| Material & Component Manufacturing | Electricity for factory, heat for processes | Water for cooling and chemical processes | Mass of steel, aluminum, plastics, glass, fertilizers | VOCs, wastewater, industrial sludge |

| Construction & Installation | Diesel for construction vehicles | - | Mass of concrete for foundations, packaging materials | Construction waste, packaging waste |

| Use Phase | Electricity for LEDs, HVAC, pumps; Natural gas for heating | Source water (municipal, well); Treated water for irrigation | Nutrients (N, P, K), pesticides, CO2 fertilization, replacement parts | Nutrient runoff, plant waste, GHG emissions from energy use |

| End-of-Life | Diesel for transport to disposal | - | Mass of material sent to landfill, recycling, or incineration | Methane from landfills, heavy metals from incineration ash |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Building an LCI requires both conceptual tools and data resources. The following table details key "reagents" for a successful LCI study.

Table: Essential Resources for LCI Development

| Tool/Resource | Function/Description | Application in LCI Development |

|---|---|---|

| ISO 14040/14044 Standards [2] [33] | Provide the internationally recognized framework and principles for conducting an LCA/LCI. | Ensures the methodological rigor, consistency, and credibility of the study. It is the foundational protocol. |

| LCI Database (e.g., Ecoinvent) [34] | A structured collection of secondary life cycle inventory data for common materials, energy, and processes. | Provides background data for upstream (e.g., material production) and downstream (e.g., waste treatment) processes, filling critical data gaps. |

| Process Flow Diagram | A visual map of all unit processes within the product system, showing their interconnections and flows. | Serves as the experimental blueprint, ensuring no significant energy, water, or material flows are omitted during data collection. |

| Functional Unit [2] | A quantified description of the performance of the product system that serves as a reference unit. | Normalizes all input and output data, enabling fair comparison between different system designs or products. |

| Data Quality Assessment | A systematic procedure to evaluate the representativeness, precision, and uncertainty of collected data. | Critical for interpreting the reliability of the final LCI results and identifying areas for improvement in future studies. |

Troubleshooting Common LCI Data Challenges

Researchers often encounter specific issues when compiling an LCI. This section addresses these problems in a question-and-answer format.

Q1: What should I do when I encounter a critical data gap for a specific material or process? A: First, attempt to use secondary data from a reputable LCI database like Ecoinvent [34]. If no suitable dataset exists, you can employ engineering calculations or stoichiometry based on the chemical and physical properties of the process to model the data [34]. Always document this as an estimation and conduct a sensitivity analysis to understand how it influences your final results.

Q2: How can I handle processes that yield multiple products (multifunctionality or allocation)? A: Allocation is a common challenge. Follow the ISO 14044 hierarchy:

- Primary Strategy: Wherever possible, avoid allocation by subdividing the process or expanding the system boundary to include the additional functions.

- Secondary Strategy: If allocation cannot be avoided, partition the inputs and outputs of the process between the co-products based on a underlying physical relationship (e.g., mass, energy content).

- Tertiary Strategy: If no physical relationship exists, use another relationship, such as the economic value of the co-products [33]. The choice must be clearly documented.

Q3: My LCI results show high uncertainty. How can I improve data quality? A: Data quality can be improved by:

- Systematic Uncertainty Management: Classify data sources by their quality (e.g., measured, calculated, estimated) and use statistical methods to propagate uncertainty.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Test how sensitive your results are to changes in key parameters (e.g., electricity grid mix, transport distance). This identifies which data points are most critical to refine [33].

- Iterative Refinement: Use the initial LCI to pinpoint the most impactful data gaps and focus efforts on collecting higher-quality primary data for those specific areas [34].

Q4: The LCA software I'm using provides default data. When is it acceptable to use? A: Software default data (often from integrated databases) is a form of secondary data and is perfectly acceptable for background processes that are not the primary focus of your study or when primary data is unavailable [33]. However, for the core processes of your CEA system (e.g., electricity consumption of your specific lighting system), you should always strive to use primary, site-specific data for greater accuracy and representativeness.

FAQs on LCI for CEA Research

Q: What is the difference between an LCI and an LCA? A: The Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) is the second phase of a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). The LCI is the meticulous compilation and calculation of all input and output flows. The LCA is the overarching methodology that includes the LCI, plus the subsequent phases of assessing environmental impacts (LCIA) and interpreting the results [2] [33].

Q: Why is the "functional unit" so critical? A: The functional unit provides a standardized basis for comparison. For example, comparing two CEA systems based on "one facility" is meaningless if their outputs are different. Comparing them based on "1 kilogram of harvested lettuce" ensures a fair and meaningful assessment of their environmental efficiencies [2].

Q: How can LCI results directly support CEA system design decisions? A: The LCI pinpoints environmental "hotspots." For instance, an LCI might reveal that 80% of a system's energy impact comes from dehumidification [35]. This evidence-based insight allows designers to prioritize research and investment into more efficient dehumidification technologies or heat recovery systems, directly optimizing the system's environmental and economic performance.

Prospective Life Cycle Assessment (pLCA) is an advanced methodology for evaluating the future environmental impacts of emerging technologies, designed specifically to address the "design paradox" or Collingridge dilemma. This principle states that the ability to change a technology's design is greatest when knowledge about its future environmental consequences is least available. pLCA addresses this challenge by enabling environmental assessment during early technology development phases when design flexibility remains high and the cost of changes is low [36].

For Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA), an industry experiencing swift global growth, pLCA offers critical decision-support capabilities. CEA encompasses agricultural systems such as greenhouses, indoor vertical farms, shipping container farms, and hydroponic systems where crops grow under precisely controlled conditions [3]. While CEA enhances food resilience through diversified sources, high productivity (10-100 times higher than open-field agriculture), and significant water conservation (using just 4.5-16% of conventional farm water per unit produce), it faces sustainability challenges related to its energy-intensive nature and high carbon footprints [3]. pLCA provides a framework to guide these emerging CEA technologies toward more sustainable development pathways by projecting their environmental performance at future industrial scales.

Key Concepts and Methodological Framework

Defining Prospective LCA

Prospective LCA is defined as "modeling a product system at a future point in time relative to the study's execution" [37]. This future-oriented approach is particularly valuable for comparing emerging CEA technologies with established conventional agricultural systems on an equitable basis. Unlike traditional retrospective LCA that relies on existing supply chains and manufacturing processes, pLCA must account for potential evolution in technologies and their environmental impacts over time [36].

pLCA is characterized by three fundamental components [37]:

- Maturity Level Assessment: Defining the current development stage of an emerging CEA technology using Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) or Manufacturing Readiness Levels (MRL)

- Upscaling: Modeling improvements in efficiency, material use, or production scale as the technology matures

- Future Scenario Development: Projecting supply chains, energy grids, and policy landscapes into the target timeframe

Comparison of LCA Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of LCA Approaches for Technology Assessment

| Aspect | Retrospective LCA | Prospective LCA |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Focus | Existing or past systems | Future-oriented (5-20+ years) |

| Primary Application | Mature, commercialized technologies | Emerging technologies in development |

| Technology Representation | Current industrial scale | Scaled-up to future industrial maturity |

| Data Sources | Historical operational data | Process simulation, expert judgment, scenarios |

| Uncertainty Handling | Sensitivity analysis | Extensive scenario development and uncertainty quantification |

| Decision-Support Leverage | Marginal improvements to existing systems | Guidance for fundamental technology design |

Core Methodological Components

The pLCA methodology for CEA technologies incorporates four interconnected components that create a comprehensive assessment framework [36]:

- Social Context: Defines how the CEA technology interfaces with human systems, including system boundaries, market effects, functional units, and relevant impact categories with their relative weights

- Technology Model: Develops inventory data for emerging CEA technologies through lab or pilot-scale data benchmarking, followed by exploration of plausible development pathways through sensitivity analysis

- Impact Assessment: Adapts existing life cycle impact assessment methods to address novel environmental flows characteristic of emerging CEA technologies, potentially requiring new characterization factors

- Interpretation with Uncertainty: Employs decision-support methods like Stochastic Multi-Attribute Analysis (SMAA) to rank alternatives while explicitly considering uncertainties and stakeholder preferences

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Workflow for pLCA of CEA Technologies

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for conducting a prospective LCA of emerging CEA technologies:

pLCA Workflow for CEA Technologies

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Technology Maturity Assessment Begin by evaluating the current Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of the CEA system under study. For early-stage technologies (TRL 1-4), document key performance parameters including energy efficiency (kWh/kg produce), water consumption (L/kg), nutrient use efficiency, biomass productivity (kg/m²/year), and resource utilization rates. This establishes the baseline against which future upscaling will be projected [37].

Step 2: Future Scenario Development Develop integrated scenarios that contextualize the scaled-up CEA technology within future background systems. These should align with common socio-economic pathways and include [38] [37]:

- Energy System Transitions: Model different electricity grid mixes with varying renewable energy penetration rates (e.g., 30%, 60%, 90% renewables)

- Policy Frameworks: Incorporate potential carbon pricing mechanisms, renewable energy incentives, and water use regulations

- Market Evolution: Project changes in demand for CEA products, competition with conventional agriculture, and supply chain transformations

- Climate Projections: Account for changing climate conditions that may affect background agricultural systems and resource availability

Step 3: Technology Upscaling Apply systematic upscaling methods to project the CEA technology from its current TRL to industrial scale (TRL 9). Use a combination of:

- Process Simulation: Model industrial-scale CEA operations using engineering principles and mass-energy balances

- Expert Elicitation: Engage CEA technology developers to identify potential efficiency improvements and scale-up factors

- Learning Curves: Apply experience-based learning rates to estimate cost reductions and efficiency gains with cumulative production capacity [37]

Step 4: Prospective Inventory Modeling Compile life cycle inventory data for the scaled-up CEA technology, incorporating:

- Foreground System: Direct inputs and outputs of the scaled CEA operation

- Background Systems: Use prospective life cycle inventory (pLCI) databases to model future supply chains, accounting for technological improvements in sectors providing materials, energy, and services to the CEA system [38]

Step 5: Impact Assessment with Prospective Factors Calculate environmental impacts using characterization factors that account for future conditions. Pay particular attention to the interlinkage between climate change and other impact categories, which represents a key source of uncertainty in prospective assessments [38].

Step 6: Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis Perform comprehensive uncertainty analysis using Monte Carlo simulation or other probabilistic methods to quantify uncertainty in the pLCA results. Identify critical parameters with the greatest influence on the outcomes to guide future research priorities [36].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Data Availability and Quality Issues

Problem: Limited inventory data for novel CEA technologies

- Symptoms: Large data gaps for specialized equipment (e.g., custom LED lighting systems, proprietary nutrient delivery systems, aeroponic misting components)

- Solution: Implement a tiered data collection approach:

- Use primary data from laboratory or pilot-scale operations for core processes

- Apply engineering process simulation to model industrial-scale operations

- Utilize proxy data from analogous industrial processes for common components

- Conduct expert interviews to estimate plausible ranges for uncertain parameters

- Prevention: Establish a data collection protocol early in technology development, documenting mass and energy flows systematically [37]

Problem: Lack of temporal specificity in background data

- Symptoms: Reliance on outdated energy grid mixes or material production data that doesn't reflect future conditions

- Solution: Integrate prospective background databases such as:

- Integrated Assessment Model (IAM) scenarios aligned with IPCC pathways

- Database-specific future scenarios (e.g., ecoinvent future scenarios)

- Region-specific energy transition forecasts

- Verification: Cross-check projections with multiple independent sources to ensure consistency [38]

Scenario Selection and System Boundary Challenges

Problem: Unrealistic or inconsistent scenario definitions

- Symptoms: Misalignment between technology-specific assumptions and background system scenarios

- Solution: Develop harmonized scenario frameworks that ensure internal consistency between:

- Technology development rates

- Energy system transitions

- Material efficiency improvements

- Policy and market conditions

- Documentation: Clearly articulate scenario narratives and quantitative assumptions in supplementary materials [38]

Problem: Inappropriate functional unit selection

- Symptoms: Difficulties in comparing CEA systems with conventional agriculture due to differing product quality, seasonality, or nutritional content

- Solution: Consider multiple functional units including:

- Mass-based units (kg of produce)

- Nutrition-based units (per specific nutrient content)

- Area-time based units (kg/m²/year)

- Economic units (per dollar of revenue)

- Justification: Select functional units that reflect the primary purpose of the assessment and enable fair comparisons [3]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does pLCA differ from conventional LCA when assessing CEA technologies?

A1: pLCA specifically addresses the temporal mismatch between emerging CEA technologies and established conventional agricultural systems by projecting all systems to a common future point and maturity level. While conventional LCA provides a snapshot of current performance, pLCA models technological learning, scale-up efficiencies, and changes in background systems over time. This enables more meaningful comparisons and helps avoid penalizing promising CEA technologies that may currently underperform but have significant improvement potential [37] [36].

Q2: What is the appropriate time horizon for pLCA studies of CEA technologies?

A2: Time horizons should align with the expected commercialization and maturation timeline of the CEA technology, typically ranging from 10-30 years. Near-term assessments (10-15 years) are suitable for technologies already at intermediate TRLs (4-6), while longer time horizons (20-30 years) are appropriate for more radical innovations at lower TRLs (1-3). The timeframe should be explicitly justified based on the technology's development trajectory and the study's decision-context [37].

Q3: How should we handle technologies with multiple possible development pathways?

A3: pLCA should explore multiple plausible development pathways through scenario analysis. For each pathway, clearly document key assumptions about:

- Technological breakthroughs and efficiency improvements

- Market adoption rates and scale-up trajectories

- Policy support mechanisms and regulatory frameworks

- Changes in supply chain configurations and material availability Results should be presented as a range of potential outcomes rather than single point estimates, with transparent discussion of the conditions under which each pathway might emerge [36].

Q4: What are the most critical impact categories for CEA technologies?

A4: While impact category selection should be goal-dependent, key categories for CEA typically include [3]:

- Global warming potential (carbon footprint)

- Energy consumption (particularly electricity use)

- Water consumption and water scarcity

- Ecotoxicity (from nutrient discharges and material production)

- Land use and transformation

- Mineral resource depletion Emerging categories of interest include light emissions affecting circadian rhythms, electromagnetic fields from electrical systems, and consequences of biogenic emissions from plant metabolism.

Table 2: Key Methodological Resources for pLCA of CEA Technologies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Methods | Application in pLCA | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upscaling Methods | Process simulation; Expert elicitation; Learning curves | Projecting laboratory-scale CEA processes to industrial implementation | [37] |

| Scenario Frameworks | Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs); Socio-economic pathways | Developing consistent future backgrounds for energy, materials, and policy | [38] |