Hybrid Life Support Systems: Integrating Physicochemical and Biological Technologies for Sustainable Space Exploration

This article explores the integration of physicochemical (ECLSS) and biological (BLSS) life support systems, a critical advancement for long-duration human space missions.

Hybrid Life Support Systems: Integrating Physicochemical and Biological Technologies for Sustainable Space Exploration

Abstract

This article explores the integration of physicochemical (ECLSS) and biological (BLSS) life support systems, a critical advancement for long-duration human space missions. It covers the foundational principles driving this hybrid approach, current methodological applications in air, water, and waste recycling, and key challenges in system reliability and complexity. By comparing international programs and validation efforts, it provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and scientists on the state of the art, current bottlenecks, and future directions for creating self-sustaining life support systems for lunar, Martian, and terrestrial applications.

The Urgent Need for Hybrid ECLSS/BLSS: Foundations and Drivers for Long-Duration Missions

Environmental Control and Life Support Systems (ECLSS) are engineered systems that maintain a habitable environment for astronauts within the hostile environment of space [1]. Their core function is to provide and regulate all essential elements for human survival and health during space travel or habitation, including breathable air, potable water, and safe living conditions, often for extended periods [1]. As human spaceflight ambitions extend to long-duration missions on the Moon and Mars, two primary technological paradigms have emerged: Physicochemical Life Support Systems (PCLSS) and Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS) [1] [2].

The PCLSS approach, which is currently operational aboard the International Space Station (ISS), relies on physical and chemical processes to recycle air and water [1]. While efficient and reliable, these systems are not indefinitely sustainable as they depend on consumable supplies from Earth [1] [3]. In contrast, the BLSS approach utilizes living organisms—such as plants, algae, and microbes—to regenerate life-sustaining resources [1] [2]. This approach holds the promise of long-term sustainability for far-reaching space exploration by creating a more self-sufficient, closed-loop ecosystem [4] [5]. This document details the defining characteristics, quantitative performance, and experimental protocols for these systems, framed within the critical research objective of integrating physicochemical and biological technologies.

System Definitions and Quantitative Comparisons

Core Components of PCLSS and BLSS

The table below compares how PCLSS and BLSS address the core requirements of a life support system, highlighting the fundamental shift in approach [1].

Table 1: Component-Level Comparison of PCLSS and BLSS

| Life Support Component | PCLSS Approach (e.g., ISS) | BLSS Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Atmosphere Control & Supply | Controlled using gas storage tanks and pressure control systems. Composition is monitored and maintained mechanically [1]. | Controlled by managing the rate of photosynthesis in plants or algae. Living systems can adapt to changing conditions [1]. |

| Oxygen Generation | Electrolysis of water, splitting it into breathable oxygen (vented into the cabin) and hydrogen (often vented overboard) [1] [3]. | Oxygen is produced as a byproduct of photosynthesis in plants, algae, or cyanobacteria [1] [6]. |

| Carbon Dioxide Removal | CO₂ is removed from the cabin air using adsorbent materials like zeolite [1]. | CO₂ is absorbed by plants or algae during photosynthesis and converted into biomass [1]. |

| Water Recovery | Wastewater (urine, humidity) is purified using physical filtration and chemical treatments [1] [3]. | Liquid waste can be used as a fertilizer/diluent for plants or processed by microbial communities in bioreactors. Water is purified through biological and mechanical filtration [1] [3]. |

| Waste Management | Solid waste is collected, stored, and disposed of. Liquid waste is processed by the Water Recovery System [1]. | Solid and liquid wastes are composted or broken down by bacteria (e.g., in a digestor) and the resulting nutrients are recycled to support plant growth [1] [3]. |

| Food Production | Crew is supplied with pre-packaged, shelf-stable meals from Earth [1]. | Food is grown directly within the habitat in controlled agriculture environments (e.g., hydroponics) [1] [5]. |

Metabolic Mass Balance and System Requirements

The design of any life support system begins with understanding human metabolic requirements. The following table summarizes the daily input and output for a reference astronaut, which forms the basis for sizing both PCLSS and BLSS [6].

Table 2: Daily Metabolic Mass Balance for a Reference Astronaut [6]

| Consumable Inputs | Mass (kg/day) | Waste Outputs | Mass (kg/day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen | 0.89 | Carbon Dioxide | 1.08 |

| Food (Dry Mass) | 0.80 | Respiratory & Perspiration Water | 3.04 |

| Drinking Water | 2.79 | Urine | 1.40 |

| Food Preparation Water | 0.50 | Feces | 0.09 |

| Water in Food | 0.76 | ||

| Total Input | ~5.74 | Total Output | ~5.61 |

For a 4-person crew on a long-duration mission, these values scale to an oxygen requirement of approximately 3.56 kg/day and a food requirement of 3.20 kg/day (dry mass) [6]. The inability of current PCLSS to produce food and their reliance on consumables for other processes creates a significant resupply mass that becomes prohibitive for missions to Mars [3]. BLSS aims to close these loops, dramatically reducing the need for resupply.

Experimental Protocols for BLSS Research

Ground-based testing in integrated analog facilities is a critical step in maturing BLSS technology. The following protocol outlines a methodology for a closed-loop human trial.

Protocol: Integrated Closed-Loop Human Habitation Trial

Objective: To validate the performance of an integrated BLSS in sustaining a human crew by simultaneously closing the atmospheric, water, and nutritional loops for a predefined duration [4] [5] [6].

Materials and Reagents:

- Sealed habitat module (e.g., analogous to BIOS-3, Lunar Palace 1)

- Higher plant growth chambers (hydroponic or aeroponic systems)

- Photobioreactors for microalgae/cyanobacteria (e.g., Spirulina, Chlorella)

- Microbial waste processing bioreactors (nitrifying bacteria, digestors)

- Atmosphere monitoring and analysis system (O₂, CO₂, trace gases)

- Water quality monitoring system (pH, conductivity, microbial load, nutrients)

- Data logging system for all core parameters

Methodology:

- System Commissioning:

- Seal the habitat module from the external environment.

- Inoculate biological components (plants, microbes) and establish stable growth conditions.

- Calibrate all monitoring and analysis equipment.

Crew Inclusion and Baseline Data Collection:

- Introduce the crew to the sealed habitat.

- Monitor and record all initial system parameters: atmospheric composition, water reserves, and biomass levels.

Closed-Loop Operation:

- Atmosphere Regeneration: Crew respiration provides CO₂ for plant photosynthesis, which in returns O₂. Continuously monitor O₂ and CO₂ partial pressures [6].

- Water Recovery: Collect crew urine and humidity condensate. Process and purify water using biological systems (e.g., plant transpiration, microbial filters) with optional physicochemical post-processing. Monitor water quality to ensure it meets potable standards [1] [3].

- Food Production: Cultivate and harvest predetermined crop species (e.g., leafy greens, starch crops, protein-rich plants) to meet a target percentage of the crew's caloric and nutritional needs [5].

- Waste Recycling: Process inedible plant biomass and human solid waste using aerobic or anaerobic microbial digestors. Recover nutrients (e.g., nitrates, phosphates) and return them to the plant growth systems as fertilizer [3].

Data Collection and Analysis:

- Continuous Monitoring: Log atmospheric gas concentrations, temperature, and humidity.

- Periodic Sampling: Perform daily or weekly analysis of water nutrients and contaminants, as well as microbial status of bioreactors.

- Crew Health Monitoring: Track crew physiological and psychological health to assess the impact of the BLSS environment [5].

System Failure and Redundancy Testing (Optional):

- Intentionally stress subsystems (e.g., reduce light to plants, simulate pump failure) to test system resilience and the effectiveness of redundant components [7].

System Integration and Signaling Pathways

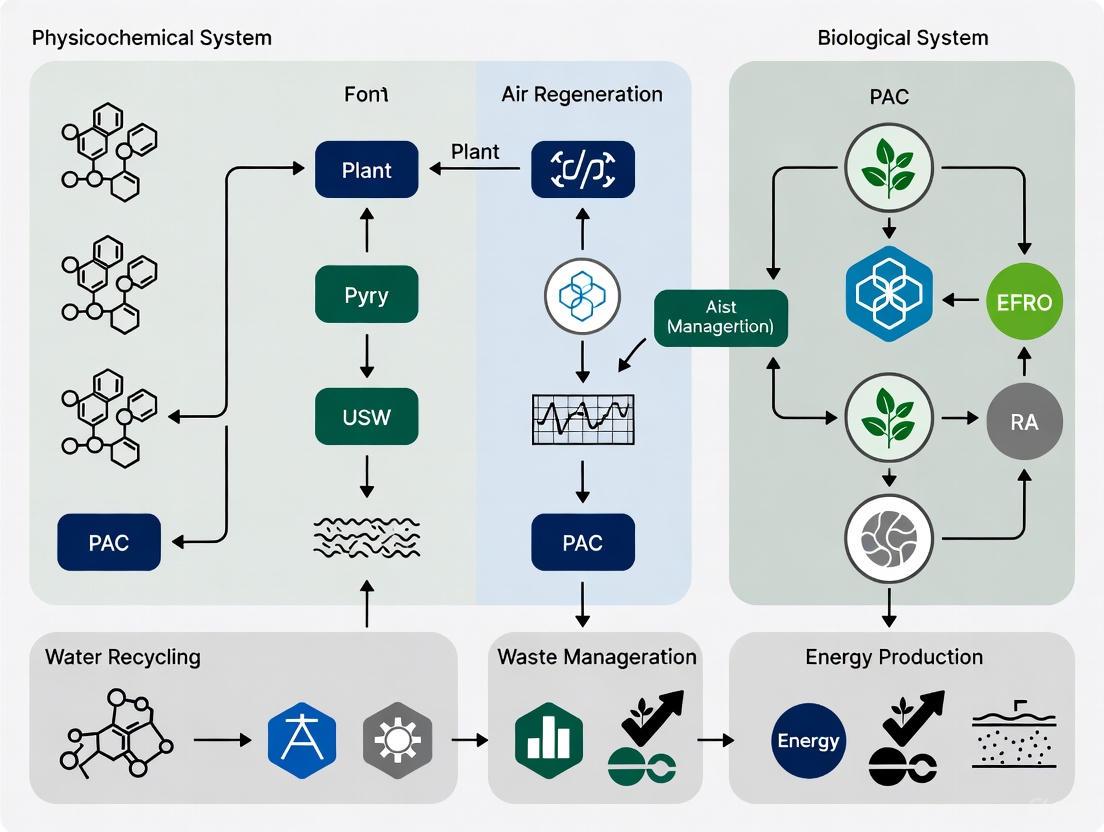

The integration of PCLSS and BLSS can be visualized as a logical workflow where biological and physicochemical components complement each other to create a more robust and resilient overall system. The diagram below outlines this integrative architecture.

Diagram 1: Integrated ECLSS Architecture. This diagram shows the flow of mass and resources between the human crew, BLSS components, and PCLSS components. Red arrows indicate contingency support, highlighting the redundancy achieved through integration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Research and development of BLSS components require specific biological agents and growth materials. The following table lists essential items for a BLSS research laboratory.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for BLSS Experimentation

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cyanobacteria & Microalgae | Oxygen production, CO₂ sequestration, biomass for food/fuel, and nutrient recovery from waste streams [6] [3]. | Spirulina platensis (high-protein food source), Chlorella vulgaris, Anabaena sp. (for nitrogen fixation) [6]. |

| Higher Plant Seeds | Primary food production, oxygen generation, water transpiration, and psychological support for crew [5]. | Dwarf cultivars of Tomato, Wheat, Potato (staple crops); Lettuce, Kale (leafy greens) [5]. |

| Nitrifying Bacteria | Critical for nitrogen recovery from urine and waste; convert ammonia to nitrates usable by plants as fertilizer [3]. | Nitrosomonas spp. (ammonia oxidizers), Nitrobacter spp. (nitrite oxidizers) [3]. |

| Hydroponic/Aeroponic Nutrient Solution | Provides essential mineral nutrients for plant growth in soilless cultivation systems within controlled environments [5]. | Hoagland's solution, or similar, with modified formulations for specific crops and closed-loop nutrient recycling [5]. |

| Synthetic Urine & Solid Waste Analog | Standardized, safe medium for testing and developing waste processing and nutrient recovery technologies without using human waste in early R&D [3]. | Solutions containing urea, creatinine, salts, and other major urine constituents; artificial fecal simulants [3]. |

| Gas Analysis System | Continuous, real-time monitoring of O₂, CO₂, and trace volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the closed atmosphere [4]. | Gas chromatographs, mass spectrometers, or laser-based gas analyzers. |

The shift from purely physicochemical to bioregenerative life support systems represents a fundamental and necessary evolution for the future of long-duration human space exploration. While PCLSS offers high reliability and immediate control, BLSS promises the long-term sustainability required for missions to Mars and beyond. The current research focus is not on a complete replacement of PCLSS, but on the strategic integration of both technologies. This hybrid approach leverages the robustness of physicochemical engineering with the regenerative potential of biology, creating resilient systems capable of supporting humanity's permanent presence in the solar system. The experimental protocols and tools outlined herein provide a foundation for the research required to achieve this critical integration.

The viability of long-duration human space exploration beyond Low Earth Orbit (LEO) is critically constrained by the immense logistical and economic challenges of resupply. Missions to the Moon or Mars cannot rely on frequent cargo deliveries from Earth, necessitating a paradigm shift from physical-chemical (p/c) Life Support Systems (LSS) to advanced hybrid and bioregenerative life support systems (BLSS) [6] [8]. These systems aim to dramatically reduce the Initial Mass in Low Earth Orbit (IMLEO) by closing the loops on air, water, and waste, and by enabling in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) [6]. The core logistical driver is the reduction of mass, which directly translates into lower launch costs and enhanced mission feasibility. This document outlines the application notes and experimental protocols for researching and developing integrated p/c and biological systems that address these drivers, providing a framework for researchers and scientists in the field of bioastronautics.

Quantitative Analysis of Mass and Cost Drivers

A fundamental understanding of crew consumable requirements is the baseline for all life support system design. The following tables summarize key metabolic metrics and the potential mass savings from advanced systems.

Table 1: Daily Metabolic Requirements and Outputs for a 4-Person Crew [6]

| Consumable / Product | Mass (kg/day) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen (O₂) | 3.56 | For respiration, including exercise regimes. |

| Food (Dry Mass) | 3.20 | ~0.80 kg/crewmember, excluding preparatory water. |

| Drinking Water | 11.16 | 2.79 kg/crewmember. |

| Food Preparation Water | 2.00 | 0.50 kg/crewmember. |

| Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) | 4.32 | Primary metabolic waste gas. |

| Respiratory & Perspiration Water | 12.16 | 3.04 kg/crewmember. |

| Urine | 5.60 | 1.40 kg/crewmember. |

Table 2: Mass and Cost Projections for Life Support Paradigms

| Metric | Physical-Chemical (State-of-the-Art) | Hybrid / Bioregenerative (Future) | Notes & Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resupply Mass for Long-Duration Missions | High (All consumables from Earth) | Low (In-situ production of O₂, food, H₂O) | The core logistical driver [6] |

| ISS Cargo Resupply Cost | ~$71,800 - $86,794 / kg | Target: Significant reduction | Cost to deliver cargo to ISS via commercial services [9] |

| System Mass Saving (Theoretical) | Baseline | Up to 39% vs. conventional LSS | From synergistic integration of fuel cells and photobioreactors [10] |

| Resupply Mass Saving (Theoretical) | Baseline | Up to 18% vs. conventional LSS | From synergistic integration of fuel cells and photobioreactors [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Hybrid LSS Research

Protocol: Three-Stage Bioregenerative System for Planetary ISRU

This protocol outlines a methodology for utilizing in-situ resources, such as Martian regolith and atmosphere, to support a human crew, based on a proposed three-stage reactor system [6].

- Objective: To establish a continuous, closed-loop system for regolith processing, atmospheric revitalization, food production, and biofuel synthesis using cyanobacteria.

- Principle: Cyanobacteria are employed due to their extreme environment tolerance, high photosynthetic efficiency, and value as a nutritional supplement and oxygen source [6].

Materials:

- Simulated Martian Regolith

- Cyanobacterial Strains (e.g., nitrogen-fixing, halo-tolerant species)

- Photobioreactors (PBRs) with controlled lighting and gas exchange

- Bioreactors for anaerobic digestion and methanogenesis

- Gas Chromatography System

- Nutrient and Biomass Analysis Equipment (e.g., HPLC, spectrophotometer)

Procedure:

- Stage 1: Regolith Bioweathering

- Inoculate simulated Martian regolith with a siderophilic (iron-oxidizing) cyanobacteria strain in a sealed reactor.

- Maintain a CO₂-rich atmosphere (95% CO₂) and provide appropriate illumination.

- Monitor the release of bio-available nutrients (e.g., phosphates, nitrates, iron) into the substrate over a 30-day period.

- Stage 2: Photobioreactor for Air and Biomass Production

- Use the leachate from Stage 1 as a growth medium for a secondary cyanobacteria culture in a high-efficiency PBR.

- Feed a mixture of crew-produced CO₂ and simulated Martian atmosphere into the PBR.

- Continuously monitor O₂ production and biomass density.

- Harvest biomass periodically for nutritional analysis (protein, vitamin, and mineral content) and as a feedstock for Stage 3.

- Stage 3: Biofuel Production Reactor

- Transfer harvested cyanobacterial biomass to an anaerobic bioreactor.

- Inoculate with methanogenic archaea.

- Monitor the production of methane (CH₄) and other volatile gases via gas chromatography as a function of time and biomass input.

- Stage 1: Regolith Bioweathering

Data Analysis:

- Calculate the mass conversion efficiency from regolith to bio-available nutrients.

- Determine the oxygen production rate (kg O₂/day) per unit volume of PBR.

- Quantify the methane yield per unit of dry biomass and assess its potential as a propellant for a Mars Ascent Vehicle.

Protocol: Synergistic Integration of Fuel Cells and Photobioreactors

This protocol details experiments to validate the mass savings from hybridizing p/c and biological components, specifically by integrating a Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cell (PEFC) with a microalgae Photobioreactor (PBR) [10].

- Objective: To demonstrate the flexible operation of a PEFC using O₂ from a PBR and to characterize the quality of water produced by the PEFC for reuse in biological systems.

- Principle: A PEFC consumes H₂ and O₂ to produce electricity, heat, and high-purity water. In a hybrid LSS, O₂ can be sourced from a PBR, and the product water can be used by the crew or to support the biological system [10].

Materials:

- 1 kWel Class Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cell (PEFC) System

- Photobioreactor (PBR) culturing Chlorella vulgaris or similar microalgae

- Gas mixing and delivery system

- Electrical load bank

- Water quality analysis kit (conductivity, pH, organic contaminants)

Procedure:

- PBR Outlet Gas Characterization: Measure the O₂ concentration and humidity level in the gas stream exiting the operational PBR.

- PEFC Operation with Variable O₂ Concentration:

- Connect the PBR outlet gas (after dehumidification if necessary) to the cathode inlet of the PEFC.

- Operate the PEFC at a constant power load while using the PBR-sourced O₂ gas mixture.

- As a control, repeat the operation using a pure O₂ source and compressed air.

- Record cell voltage, efficiency, and thermal signature under each condition.

- Product Water Quality Analysis:

- Collect the product water from the PEFC cathode exhaust during operation with both PBR gas and control gases.

- Analyze the water for conductivity, pH, and the presence of any ionic or organic contaminants that could be detrimental to biological systems or human consumption.

Data Analysis:

- Compare PEFC performance (efficiency, voltage stability) across the different cathode gas inputs.

- Confirm the suitability of PEFC product water for supporting microalgal growth or as a potable water source.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Advanced LSS Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cyanobacterial Strains | Primary biological agents for O₂ production, CO₂ sequestration, and biomass generation. | Anabaena sp. for nitrogen fixation; Spirulina sp. for nutritional biomass [6]. |

| Simulated Planetary Regolith | Geochemically accurate analog for testing in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) protocols. | Testing bio-mining of nutrients and elements from Lunar or Martian soil simulants [6]. |

| Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cell (PEFC) | A physicochemical system for converting H₂ and O₂ into electricity, heat, and pure H₂O. | Investigating synergistic mass flow integration with biological O₂ sources [10]. |

| Controlled Environment Photobioreactor (PBR) | Provides optimized growth conditions (light, temperature, pH, gas exchange) for photosynthetic microorganisms. | Cultivating microalgae for continuous atmospheric revitalization and biomass production [10]. |

| Chlorella vulgaris | A fast-growing, unicellular green alga with high photosynthetic efficiency. | Used as a model organism for studying gas exchange and biomass production in closed systems [10]. |

System Integration and Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the synergistic mass flow integration between biological and physicochemical subsystems in a hybrid LSS architecture, as investigated in the protocols above.

The advancement of human space exploration from short-term missions in Low-Earth Orbit to long-duration expeditions on the lunar surface and beyond necessitates a paradigm shift in life support technology. Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS) represent the most advanced class of life support, using biological processes to regenerate air, water, and food from crew waste, thereby drastically reducing the need for resupply from Earth [11]. This document frames the historical progression from NASA's early Controlled Ecological Life Support System (CELSS) program to contemporary international efforts within the context of integrating physicochemical and biological systems research. The synthesis of these technologies is critical for developing closed-loop habitats that are logistically feasible, psychologically sustainable, and operationally resilient for endurance-class deep space missions.

Historical Programs and Their Core Methodologies

The development of BLSS has been driven by several key international programs, each contributing unique architectures and experimental protocols.

NASA's CELSS Program

Research Objectives: Initiated to address the requirements of long-duration missions, the CELSS program pursued a two-pronged objective: first, to assess the ability of plants and animals to grow, mature, and reproduce efficiently in altered gravity; and second, to develop the engineering capability to cleanse and recycle air and water [12].

Key Experimental Protocols:

- Plant Cultivation: Investigation of optimum environmental requirements for higher plants in recycling systems, including refinement of hydroponic and aeroponic techniques and plant lighting requirements [12].

- System Sizing: Early studies determined that a system supporting 4-6 humans would require a volume of 150 to over 200 cubic feet, encompassing water recycling, atmosphere regeneration, waste recycling, and plant growth facilities [12].

- Food Source Development: Research into the use of algae as a human food source and inquiry into efficient biological waste processing methods [12].

The European MELiSSA Consortium

System Architecture: The Micro-Ecological Life Support System Alternative (MELiSSA) is a circular life support system project by the European Space Agency, designed to achieve the highest degree of crew autonomy by producing food, water, and oxygen from mission wastes [13]. Its design is inspired by aquatic ecosystems and is structured into several compartments, each performing a specific recycling function.

Key Evaluation Criteria: The project's development is driven by the ALISSE criteria: Mass, Energy, Efficiency, Safety, and Crew Time [13]. Without such recycling, a manned Mars mission would require an estimated 30 tonnes of supplies [14].

China's Lunar Palace Program

Experimental Platform: Lunar Palace 1 is a ground-based integrative BLSS facility with a volume of 500 m³, comprising nine core units: Temperature and Humidity Control Unit (THCU), Water Treatment Unit (WTU), LED Light Source Unit (LLSU), Solid Waste Treatment and Yellow Mealworm Feeding Unit (SWT-YMFU), two plant cabins, a Plant Cultivation Substrate Unit (PCSU), Mineral Element Supply Unit (MESU), and an Atmosphere Management Unit (AMU) [15].

Protocols for Long-Duration Missions: The "Lunar Palace 365" mission was a 370-day closed human experiment with four crew members. The core methodologies included:

- Gas Balance Management: Maintaining O₂ and CO₂ concentrations via strategic intervention during plant dark phases and crew shift changes. CO₂ was held between 246 and 4131 ppm, with an average of 1126 ppm [16].

- Water Recycling: A multi-loop system recovered potable water from condensate and hygienic water (e.g., from showers and laundry) to a standard suitable for irrigation and drinking [16].

- Food Production: Cultivation of 35 plant types (including food crops, vegetables, and fruit) and production of animal protein via yellow mealworms fed on inedible plant biomass [15] [16].

- Waste Processing: Human feces and inedible plant biomass were fermented and processed into soil-like substrate (SLS) for plant growth [16].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics from Major BLSS Experiments

| System / Parameter | Lunar Palace 1 (370-day exp.) | NASA CELSS (Targets) | MELiSSA (Objectives) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Closure Degree | 98.2% [16] | N/A | Highest autonomy [13] |

| O₂ & Water Recycling | 100% achieved [16] | Full regeneration [12] | Full regeneration [14] |

| Food Regeneration | "Most" food regenerated [16] | Food production [12] | Food from waste [13] |

| Crew Size & Duration | 4 crew, 370 days [15] | 4-6 humans [12] | N/A |

| Key Crops/Organisms | Wheat, potato, soybean, lettuce, yellow mealworms [16] | Potatoes, wheat, algae, soybeans [12] [17] | Multi-compartment bioreactors [13] |

Integrated System Architecture and Workflows

A functional BLSS requires the tight integration of biological and physicochemical components. The following diagram illustrates the core material flows and subsystem interactions within an advanced BLSS, synthesizing concepts from the Lunar Palace and MELiSSA architectures.

Diagram: Material flow in a bioregenerative life support system.

Protocol: Integrated System Operation and Monitoring

Objective: To maintain stable atmospheric gas concentrations and material flow within a closed-loop BLSS during long-term operation with crew rotations.

Workflow:

- Atmospheric Monitoring: Continuously monitor concentrations of O₂, CO₂, and trace contaminants using in-situ sensors. Data is logged in real-time for trend analysis [16].

- Gas Balance Intervention:

- During Plant Dark Cycle: Implement physicochemical backup systems (e.g., CO₂ scrubbers, O₂ tanks) to compensate for the cessation of photosynthetic O₂ production and CO₂ consumption in plant cabins during their dark period [16].

- During Crew Shift Change: Anticipate and manage metabolic load changes as crew members enter or exit the closed environment. This may involve pre-emptive adjustment of plant growth chamber lighting schedules or deployment of physicochemical systems to buffer the transition [16].

- Water Loop Management: Treat and separate water streams based on source and contamination level (condensate, urine, hygienic water). Purified water is recursively allocated for human consumption, plant irrigation, and other processes [16].

- Failure Mode Monitoring: Record the number and time of failures for each technical unit (e.g., THCU, WTU). Use this data, in conjunction with methods like Monte Carlo simulation, to estimate system reliability and lifetime [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental research and technological development of BLSS rely on a suite of critical reagents, biological agents, and growth substrates.

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for BLSS Experimentation

| Item | Function / Rationale | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Hydroponic/Aeroponic Systems | Soilless plant cultivation; allows for precise control of nutrient delivery and root zone environment [12]. | Core plant growth methodology in CELSS and Lunar Palace [12] [16]. |

| LED Light Source Systems | Provides photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) for plant growth; enables control over photoperiod, light intensity, and spectrum to optimize yield and energy efficiency [15] [16]. | Used in the LED Light Source Unit (LLSU) of Lunar Palace 1 [15]. |

| Soil-Like Substrate (SLS) | A growth medium produced from bioconversion of solid organic wastes (inedible biomass, human feces); mimics the complex physical and nutrient-holding properties of soil [16]. | Created via fermentation in Lunar Palace to support plant growth in the Plant Cultivation Substrate Unit [16]. |

| Selected Cyanobacteria & Algae | Potential candidates for air revitalization (O₂ production, CO₂ consumption) and as a supplemental food source due to high protein content and rapid growth [12]. | Investigated in the NASA CELSS program and the European MELiSSA project [12] [13]. |

| Yellow Mealworms (Tenebrio molitor) | A micro-livestock agent for animal protein production; efficiently converts inedible plant biomass (e.g., straw) into high-quality protein for crew consumption [16]. | Integrated into the Solid Waste Treatment unit of Lunar Palace 1 [15] [16]. |

| Lunar Regolith Simulant | A terrestrial geological material engineered to mimic the chemical and physical properties of lunar soil. Essential for testing in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) strategies for plant cultivation and construction [18]. | Used in research for lunar agriculture and excavation technologies [18]. |

Quantitative Reliability Analysis Protocol

Objective: To quantitatively estimate the reliability and lifetime of a BLSS based on empirical unit failure data from long-duration missions.

Methodology (Based on Lunar Palace 370-day Experiment):

- Data Collection: Accurately record the number and precise time of failure for each operational unit within the BLSS (e.g., THCU, WTU, LLSU) over the entire experimental duration [15].

- Parameter Estimation: For each unit, model the failure as a stochastic process. Use maximum likelihood estimates to identify the failure rate (λ, in days⁻¹) and its 95% confidence interval based on the experimental data [15].

- Monte Carlo Simulation: Generate a large number of synthetic BLSS lifetime simulations (e.g., 50,000 runs). In each simulation, the time-to-failure for each unit is randomly generated based on its specific failure rate probability distribution [15].

- Lifetime Calculation: The overall system failure time in each simulation is defined as the moment the first critical unit fails. The average lifespan and confidence intervals for the entire BLSS are then calculated from the aggregated results of all simulation runs [15].

Results from Application: Application of this protocol to Lunar Palace 1 data yielded an estimated average BLSS lifespan of 19,112 days (approximately 52.4 years), with a 95% confidence interval of [17,367, 20,673] days. The analysis identified that the Temperature and Humidity Control Unit (THCU) and Water Treatment Unit (WTU) had the highest probability of failure and the greatest impact on overall system reliability [15].

The historical trajectory from NASA's CELSS to the international MELiSSA consortium and China's Lunar Palace demonstrates a convergent understanding that bioregenerative technologies are indispensable for sustained human presence beyond Earth. The experimental protocols and quantitative data generated, particularly from the long-duration Lunar Palace 365 mission, provide an invaluable empirical foundation for future system design. Key research gaps remain, including the full integration of biological and physicochemical subsystems into a seamless, fault-tolerant architecture, and a deeper understanding of the long-term effects of deep space radiation on all biological components of the BLSS [11]. Addressing these challenges through continued international research and development is a strategic imperative for the future of human space exploration.

The development of robust Life Support Systems (LSS) for long-duration space missions necessitates the precise quantification of core human metabolic requirements. Successful integration of physicochemical and biological subsystems depends on accurate data for oxygen consumption, water utilization, and nutritional needs. This document provides consolidated quantitative data, experimental protocols, and research tools essential for advancing closed-loop life support systems, drawing from current research in human performance and bioregenerative technologies.

Quantitative Data on Core Metabolic Requirements

The following tables summarize the fundamental quantitative requirements for human metabolism, essential for the design and sizing of life support systems.

Table 1: Daily Human Metabolic Input and Output Mass Balance [19]

| Parameter | Average Value per Person | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Consumption | 0.869 kg | For baseline human metabolism; increases with activity. |

| Water Consumption | 2.0 - 5.0 kg | Includes drinking and sanitary-hygiene purposes. |

| Caloric Intake | Varies | Based on a sustained energy expenditure of ~2.4 x BMR [20]. |

| Carbon Dioxide Production | 1.0 kg | Requires active removal from the atmosphere. |

| Solid & Liquid Wastes | Variable | Source of minerals for recycling; requires processing. |

Table 2: Performance of Biological Life Support System (BLSS) Components [19]

| Component | Function | Key Performance Metric | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microalgal Compartment | O₂ Production, CO₂ Assimilation | 0.60 kg dry weight/day | Produces ~0.869 kg O₂ by utilizing 1.0 kg of CO₂. |

| Higher Plant Compartment | O₂ Production, Food Production, Water Transpiration | 20-30 m² cultivation area/person | Provides food and a portion of O₂; transpiration moisture is a water source. |

| Soil-Like Substrate (SLS) | Inedible Biomass & Waste Processing | N/A | Processes plant residues and human wastes, releasing CO₂ and minerals. |

Table 3: Human Brain Metabolic Water Production from Glucose Catabolism [21]

| Metabolic State | Predicted Net Metabolic Water Production | Key Metabolic Shifts |

|---|---|---|

| Rest | Highest | Dominated by glucose oxidation in neuronal mitochondria. |

| Increased Activity | Reduced by 30-40% | Shift to glycolysis and ATP hydrolysis (consumes water). |

| Deep Sleep | Reduced by 30-40% | Associated with lower metabolic activity. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Determining Sustained Metabolic Ceiling

Title: Quantification of Long-Term Human Energy Expenditure Capacity

Background: The human body exhibits a maximum sustained energy expenditure, or "metabolic ceiling," critical for designing food provision systems in isolated environments [20].

Methodology:

- Subject Population: Recruit elite endurance athletes undergoing prolonged training regimens (e.g., 30 weeks or more).

- Energy Expenditure Measurement: Utilize the doubly labeled water method to track total energy expenditure over extended periods.

- Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) Calculation: Measure or calculate the BMR for each subject.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the ratio of total energy expenditure to BMR. The sustained ceiling is identified as the maximum observed ratio across the subject population over the study duration.

Expected Outcome: The study will confirm a sustained metabolic ceiling of approximately 2.4 times the Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR), beyond which the body unconsciously reduces energy expenditure in other physiological areas [20].

Protocol for Measuring Metabolic Water Flux in the Brain

Title: Stoichiometric Budgeting of Metabolic Water in the Rodent Brain

Background: Metabolic water is a significant contributor to brain fluid homeostasis, with production rates varying by functional state [21].

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Obtain published data on brain oxygen and glucose consumption rates in awake rodents (or humans) at rest, during elevated activity, and during sleep.

- Stoichiometric Modeling: Apply mechanistic stoichiometry to known biochemical pathways (glucose oxidation, glycolysis, glycogenolysis, ATP hydrolysis) to calculate the net production or consumption of water molecules for each pathway.

- Glucose Oxidation: Modeled as the primary source at rest.

- Glycolysis & ATP Hydrolysis: Account for water consumption during increased activity.

- Glycogenolysis: Model as a potential contributor during astrocyte activation.

- State-Dependent Budgeting: Integrate pathway fluxes to generate a comprehensive water budget for each brain state (rest, activity, sleep).

Expected Outcome: The protocol will yield quantitative predictions showing metabolic water production is highest at rest, dominated by neuronal mitochondria, and decreases by 30-40% during periods of increased activity or deep sleep [21].

Protocol for Algal and Higher Plant Integration in BLSS

Title: Phased Transfer of Regenerative Functions from Algae to Higher Plants

Background: A BLSS can be initiated with microalgae for rapid air and water revitalization, with a gradual transition to higher plants for more sustainable food and oxygen production [19].

Methodology:

- System Startup:

- Inoculate and activate the microalgal compartment to achieve target biomass density.

- The algal compartment is sized to fully satisfy one human's oxygen demand (utilizing 1.0 kg CO₂ and producing 0.869 kg O₂ per day).

- Higher Plant Compartment Establishment:

- Simultaneously, initiate a crop conveyor system (e.g., in a Soil-Like Substrate) with species selected for the mission diet.

- Note: The plant compartment requires 3-4 months to reach full food production efficiency and ~2 months for full oxygen/water regeneration.

- System Transition & Balancing:

- As the higher plant compartment matures, systematically reduce the operational load on the algal compartment.

- Continuously monitor and balance O₂/CO₂ levels, water vapor, and nutrient flows (N, P, K, S) between all subsystems.

- Waste Stream Integration:

- Implement physicochemical (e.g., "wet incineration" with H₂O₂) or biological units to process human wastes and inedible plant biomass.

- Reintegrate recovered minerals and CO₂ into the algal and plant compartments.

Expected Outcome: This protocol enables the establishment of a partially closed-loop system, defining the mass flows and time parameters required for a stable transition from a microalgae-dependent system to one dominated by higher plants [19].

System Workflow and Metabolic Pathways

BLSS Mass Flow Diagram

Brain Metabolic Water Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for BLSS and Metabolic Research

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Soil-Like Substrate (SLS) | A growth medium for higher plants that also processes inedible plant biomass and solid wastes, facilitating nutrient recycling within the BLSS [19]. |

| Microalgal Cultures (e.g., Chlorella) | The core biological component for initial air (O₂ production, CO₂ removal) and water revitalization; can be cultured in processed liquid waste streams [19]. |

| Liquid-Phase Oxidation Reactor (H₂O₂) | A physicochemical unit for the "wet incineration" of human wastes and inedible biomass, breaking them down into mineral nutrients that can be recycled to algal and plant compartments [19]. |

| Doubly Labeled Water (²H₂¹⁸O) | The gold-standard non-invasive method for measuring total energy expenditure in free-living humans over extended periods, crucial for validating metabolic models [20]. |

| Stoichiometric Metabolic Models | Computational frameworks for predicting inputs, outputs, and yields of biological processes (e.g., metabolic water production, O₂/CO₂ exchange) based on biochemical first principles [21]. |

Strategic Gaps and Geopolitical Landscape in Bioregenerative Technology Development

The pursuit of long-duration human space exploration is fundamentally constrained by the trinity of logistics costs, technological limits, and human health risks associated with current physical/chemical (physicochemical) life support systems [8]. Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS) represent a paradigm shift, utilizing biological organisms to recycle waste, regenerate atmosphere, and produce food, thereby enabling greater self-sufficiency for missions beyond low-Earth orbit (LEO) [5]. The geopolitical landscape of this technology is marked by a significant strategic divergence. Following the 2004 Exploration Systems Architecture Study (ESAS), NASA discontinued and physically demolished programs like BIO-PLEX, leading to critical gaps in US capabilities [8] [22]. Conversely, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) has "embraced and advanced" these same technologies over the past two decades, successfully demonstrating a closed-system life support in the Beijing Lunar Palace (Lunar Palace 1) that sustained a crew of four for a full year [8] [22]. This paper analyzes these strategic gaps and provides detailed application notes and protocols to guide the integration of bioregenerative and physicochemical systems.

Current Landscape and Geopolitical Dynamics

Comparative Analysis of International BLSS Programs

The global development of BLSS has followed distinct paths, resulting in varied levels of technological maturity and integration.

Table 1: Comparison of Major International BLSS Initiatives and Capabilities

| Program / Agency | Key Focus & Technologies | Integration Level & Human Testing | Notable Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|

| NASA (Historical: CELSS, BIO-PLEX) | Controlled Environment Agriculture (CEA), higher plant cultivation [8] | Formerly integrated habitat testing; program discontinued in 2004 [8] | Pioneering research; foundational work adopted by other nations [8] |

| CNSA (Lunar Palace 1) | Integrated "human-plant-animal-microbe" system [22] | High; ground-based, fully integrated testing with human crews [8] [22] | 370-day continuous operation with a crew of four; high system stability [22] |

| ESA (MELiSSA) | Compartmentalized, engineered ecosystem mimicking a lake [3] | Moderate; advanced component testing, but no closed-system human testing [8] [3] | Long-running, systematic engineering program; pilot plant (MPP) operation [5] [3] |

| Roscosmos (BIOS-3) | Closed ecological systems with algae and plants [5] | High; historical human-in-the-loop testing in the 20th century [5] | Early demonstrations of closed gas and water exchange [5] |

The data reveals that CNSA currently leads in demonstrating fully integrated, crew-tested BLSS operations. The Lunar Palace 1 facility achieved a world record for continuous operation, with its four-component biological chain maintaining stable interactions and plant production efficiency fully meeting crew demand [22]. This capability is a cornerstone of China's plans for long-term lunar habitation. Meanwhile, NASA's current approach remains reliant on resupply missions for food, water, and consumables for its physicochemical Environmental Control and Life Support Systems (ECLSS), a model that is logistically and economically prohibitive for sustained lunar or Martian presence [8] [6]. The European MELiSSA program offers a robust, engineering-focused pathway but has not yet reached the integrated human-testing stage [8] [3].

Quantitative Analysis of Life Support Requirements

A systems-level understanding of human metabolic needs is fundamental to BLSS design. These requirements dictate the scale and performance of all downstream biological and physicochemical components.

Table 2: Daily Metabolic Mass Balance for a Reference Astronaut (82 kg) [6]

| Consumable Input | Mass (kg) | Waste Output | Mass (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen (O₂) | 0.89 | Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) | 1.08 |

| Food (Dry Mass) | 0.80 | Respired & Perspired Water | 3.04 |

| Drinking Water | 2.79 | Urine | 1.40 |

| Food Preparation Water | 0.50 | Feces | 0.09 |

| Water in Food | 0.76 | ||

| TOTAL INPUT | 5.74 | TOTAL OUTPUT | 5.61 |

For a crew of four on a 3-year mission, these daily requirements translate into a prohibitive payload mass of over 25,000 kg for food and water alone, underscoring the non-viability of a pure resupply strategy [3]. A BLSS aims to close these mass loops, with a particular focus on nitrogen recovery, as 85% of the recoverable nitrogen in a habitat is found in urine, primarily as urea [3].

Critical Gaps and Integrated System Requirements

The transition from current ECLSS to a hybrid BLSS-ECLSS architecture is hindered by several strategic gaps identified in recent analyses:

- Nitrogen Recovery and Urine Processing: Current ISS systems, like the Urine Processor Assembly (UPA), acidify and chemically stabilize urine to prevent scaling and urea hydrolysis, subsequently removing water via distillation. The resulting brine, rich in nitrogen and other nutrients, is considered waste [3]. A BLSS requires technologies to recover this nitrogen in a bioavailable form (e.g., nitrate) for plant and algal production [3].

- Crop System Integration and Optimization: Not all plants are equally suitable for space. Mission scenarios dictate crop selection: short-duration missions benefit from fast-growing, high-nutrition leafy greens and microgreens, while long-duration outposts require staple crops (wheat, potato) for carbohydrates and proteins [5]. Gaps exist in understanding the Edible Biomass Yield and resource requirements (light, water, nutrients) of these crops in closed, space-relevant environments [4].

- Radiation Effects on Biological Systems: A critical knowledge gap exists regarding the impact of deep-space radiation on the efficiency and stability of biological components, including plants and microorganisms essential for BLSS function [8].

- Integrated Pest Management (IPM): As BLSS modules scale, the risk of phytopathogen outbreaks increases, as demonstrated by a Fusarium oxysporum outbreak on Zinnia plants in an ISS Veggie module [23]. A comprehensive, preventive IPM protocol for space-based agriculture is underdeveloped [23].

Application Notes & Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for bridging the identified gaps through integrated research.

Protocol: Nitrogen Recovery from Urine for Fertilizer Production

This protocol outlines the integration of a biological nitrogen recovery process with the existing physicochemical UPA, targeting the conversion of urea and ammonium into nitrate for plant nutrition.

1.0 Principle: Utilize a two-stage microbial process to convert urea and ammonia in urine to nitrate. Ureolytic bacteria first hydrolyze urea to ammonia and carbon dioxide. Subsequently, nitrifying bacteria (Nitrosomonas and Nitrobacter spp.) sequentially oxidize ammonia to nitrite and then to nitrate [3].

2.0 Workflow Diagram: Nitrogen Recovery Process

3.0 Reagents and Equipment:

- Stabilized Urine Brine: Simulant or real effluent from a UPA-like system.

- Microbial Inocula: Pure or enriched cultures of Bacillus spp. (ureolytic), Nitrosomonas europaea, and Nitrobacter winogradskyi.

- Bioreactor System: Two continuously stirred tank reactors (CSTRs) with pH, temperature, and dissolved oxygen control.

- Analytical Equipment: Ion Chromatography system for NH₄⁺, NO₂⁻, NO₃⁻ quantification; HPLC for urea analysis.

4.0 Procedure:

- Feedstock Preparation: Adjust the pH of the stabilized urine brine to 7.5 using a sterile NaOH solution.

- Stage 1 - Ureolysis: Feed the pH-adjusted brine into the first CSTR inoculated with ureolytic bacteria. Maintain temperature at 30°C and monitor urea concentration until hydrolysis is >95% complete.

- Stage 2 - Nitrification: Transfer the effluent from Stage 1 to the second CSTR, inoculated with nitrifying bacteria. Maintain dissolved oxygen >4 mg/L and temperature at 28-30°C. Monitor the conversion of NH₄⁺ to NO₃⁻ until [NH₄⁺] is below a target threshold (e.g., <5 mg/L).

- Harvesting: Pass the nitrified effluent through a centrifuge to remove microbial biomass. Sterilize the supernatant via 0.2 µm filtration. The resulting solution is a liquid fertilizer ready for integration into hydroponic systems.

Protocol for BLSS Crop Selection and Cultivation

1.0 Principle: Select plant species based on mission duration and objectives to optimize resource use and meet nutritional needs. Use controlled environment agriculture (CEA) techniques with 100% nutrient recycling from BLSS loops [5].

2.0 Workflow Diagram: BLSS Crop Cultivation Logic

3.0 The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for BLSS Crop and Microbiology Research

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application in BLSS Research |

|---|---|

| Cyanobacteria (e.g., Anabaena sp.) | Versatile organisms for Stage 1 regolith bioweathering, O₂ production, CO₂ fixation, and nutritional biomass production [6]. |

| Nitrifying Bacteria Consortia | Essential for converting ammonia from waste streams into nitrate, the primary nitrogen fertilizer for plants [3]. |

| Hydroponic Nutrient Solution | A precisely formulated aqueous solution of all essential mineral nutrients for plant growth, to be derived from recycled waste streams [5]. |

| Select Plant Cultivars | Short-Term: Lettuce, kale, microgreens (fast, high-nutrition). Long-Term: Wheat, potato, soybean, tomato (carbohydrates, protein) [5]. |

| LED Lighting Systems | Provides specific, energy-efficient light spectra (e.g., red, blue, white) to optimize plant photosynthesis and morphology [4]. |

4.0 Procedure:

- Species Selection: Based on the mission class defined in the logic diagram, select appropriate species from the toolkit.

- Growth System Setup: Establish a hydroponic or aeroponic system. Circulate the nitrate-rich fertilizer from Protocol 4.1.

- Environmental Control: Maintain optimal conditions: LED photoperiod of 16-18 hours, light intensity of 300-600 µmol/m²/s photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD), relative humidity of 60-70%, and CO₂ concentration of 1000-1200 ppm.

- Monitoring and Harvest: Monitor plant health, growth rates, and gas exchange (O₂ production/CO₂ consumption). At maturity, harvest edible biomass and return inedible plant waste to the BLSS recycling loop (e.g., for composting or microbial processing).

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) Protocol for BLSS

1.0 Principle: Implement a dynamic, multi-layered strategy to prevent, monitor, and control pest and pathogen outbreaks in space-based plant growth systems [23].

2.0 Procedure:

- Prevention (Primary):

- Quarantine & Sanitation: Strictly quarantine and surface-sterilize all seeds and plant materials before introduction into the BLSS.

- System Design: Utilize semi-closed plant growth modules with independent environmental controls (e.g., Advanced Plant Habitat) to isolate crops from the crew habitat microbiome [23].

- Environmental Control: Avoid conditions of high humidity and free water on plant surfaces, which are conducive to pathogen growth [23].

- Monitoring:

- Conduct daily visual inspections of plants for disease symptoms or insect pests.

- Utilize molecular tools (e.g., PCR) and culture-based methods to regularly assay for the presence of key phytopathogens in the air, water, and on plant surfaces.

- Control:

- Physical: Remove and isolate infected plant material immediately. Use HEPA filtration for intake air in open systems like Veggie.

- Biological: Apply approved microbial antifungals or biopesticides. The use of beneficial microbes as biocontrol agents requires further research for spaceflight approval.

- Chemical: The use of conventional pesticides is a last resort due to risks of contaminating closed-loop systems and affecting crew health.

The strategic gap in bioregenerative life support technology between the US and its competitors, notably China, poses a significant risk to the sustainability and leadership of future lunar and Martian exploration programs [8] [22]. Closing this gap requires a committed, long-term strategy that moves beyond pure physicochemical systems. The application notes and protocols detailed herein provide a roadmap for the necessary integration of biological systems—focusing on critical path technologies like nitrogen recovery, optimized crop production, and proactive pest management. The success of future "endurance-class" deep space missions will depend on achieving the high degree of self-sufficiency that only a fully developed and flight-proven hybrid BLSS-ECLSS can provide.

Implementing Hybrid Systems: Methodologies for Air, Water, and Food Production

The advancement of human space exploration beyond low-Earth orbit is contingent upon the development of robust, self-sustaining life support systems. This application note details the integration of physicochemical (PC) and biological technologies to create a hybrid air revitalization system. The outlined architecture synergistically combines carbon dioxide (CO₂) capture, its chemical reduction via the Sabatier process, and biological oxygen (O₂) production using cyanobacteria for long-duration missions. We provide a comprehensive technical overview, quantitative performance data, detailed experimental protocols for key processes, and a catalog of essential research reagents to support ground-based testing and development of these integrated systems.

Future long-duration missions to the Moon and Mars cannot rely on the current paradigm of resupply from Earth due to the excessive mass of essential consumables, estimated at 15–20 kg per person per day [24]. Air revitalization—the process of maintaining a breathable atmosphere by removing CO₂ and replenishing O₂—is a cornerstone of any life support system. While the International Space Station (ISS) employs primarily physicochemical (PC) systems, Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS) offer the potential for greater closure of air, water, and food loops [4] [8].

This document frames a hybrid approach within the broader thesis that the synergistic integration of PC and biological systems is the most viable path toward sustainable, long-duration space habitation. The proposed system leverages the reliability of PC components for initial CO₂ processing and the regenerative capacity of biological components, specifically cyanobacteria, for O₂ production and biomass generation. This architecture is exemplified by the three-stage reactor system proposed for planetary habitats, which integrates regolith processing, atmospheric revitalization, and biofuel production [6].

Table 1: Daily Metabolic Requirements and Outputs for a Reference Astronaut [6]

| Consumable | Input (kg/day) | Waste Product | Output (kg/day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen (O₂) | 0.89 | Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) | 1.08 |

| Food (Dry Mass) | 0.80 | Urine & Feces | (See Water) |

| Drinking Water | 2.79 | Resp. & Perspiration Water | 3.04 |

| Food Prep Water | 0.50 | Urine | 1.40 |

| Water in Food | 0.76 | Feces | 0.09 |

| Total (Approx.) | ~5.84 | Total (Approx.) | ~4.53 |

Core System Components and Technologies

Physicochemical (PC) Subsystem: CO₂ Capture and Sabatier Reaction

The PC subsystem handles the initial concentration and processing of CO₂ from the cabin atmosphere.

- CO₂ Capture: Current systems on the ISS use molecular sieves and adsorption beds to concentrate CO₂ from the cabin air [6].

- Sabatier Reactor: The concentrated CO₂ is then reacted with hydrogen (H₂) in a catalytic (typically ruthenium or nickel-based) reactor. The primary reaction is: CO₂ + 4H₂ → CH₄ + 2H₂O + Energy This process effectively removes CO₂, produces water (a valuable resource), and methane (CH₄) [6]. The methane can be vented, used as a propellant, or, in advanced concepts, serve as a feedstock for other biological processes [6].

Biological Subsystem: Cyanobacteria-Based Oxygen Production

The biological component completes the air loop by regenerating O₂ from CO₂. Cyanobacteria, particularly Limnospira indica (formerly Arthrospira or Spirulina), are ideal candidates due to their high photosynthetic efficiency, edibility, and resilience.

- Organism: Limnospira indica, as used in the European Space Agency's MELiSSA (Micro-Ecological Life Support System Alternative) project [24].

- Function: In a photobioreactor (PBR), cyanobacteria consume CO₂ and, using light energy, perform photosynthesis: CO₂ + H₂O + Light → Biomass + O₂ This process directly revitalizes the cabin atmosphere by producing breathable O₂ while simultaneously generating nutritious biomass [6] [24].

System Integration Logic

The synergy between the PC and biological subsystems creates a more resilient and regenerative whole. The Sabatier process efficiently removes the bulk of CO₂ and produces water, while the cyanobacteria fine-tune the O₂ level and produce food. An integrated system can also explore using biological components to further process waste streams, such as using non-nitrified urine as a nitrogen source for cyanobacteria [24].

Diagram 1: Integrated air revitalization system logic flow.

Experimental Protocols for System Validation

This protocol is adapted from ground demonstration studies for the MELiSSA loop [24] and investigates the viability of using simplified waste streams.

1. Objective: To cultivate Limnospira indica using different nitrogen sources (nitrate, urea, ammonium) representative of non-nitrified human urine and to monitor its effect on biomass growth and oxygen production capacity in a closed-loop system.

2. Materials:

- Limnospira indica (e.g., PCC 8005 strain) inoculum.

- Modified Zarrouk’s medium (lacking nitrate, for experimental setups).

- Nitrogen sources: Sodium Nitrate (NaNO₃), Urea ((NH₂)₂CO), Ammonium Chloride (NH₄Cl).

- Photobioreactor (PBR) system with lighting control, temperature control, pH and dissolved O₂ probes.

- Gas mixing system to supply a defined CO₂-in-air mixture.

- Oxygen sensor for monitoring headspace O₂ concentration.

- Mouse compartment or equivalent CO₂ source (e.g., calibrated gas flow).

3. Methodology:

- Preparation: Set up three independent PBR systems. Prepare growth media for each condition: 1) Nitrate-based (control), 2) Urea-based, 3) Ammonium-based. Ensure equivalent molar nitrogen concentration across all media.

- Inoculation: Aseptically inoculate each PBR with a standardized volume of a healthy Limnospira culture to an initial optical density (OD₅₆₀) of ~0.1.

- System Closure & Control: Connect the PBRs to the CO₂ source. Implement a deterministic control law that modulates the incident light intensity on the PBR based on the real-time O₂ concentration in the loop. The setpoint should be 20.3% O₂ [24].

- Monitoring: Conduct the experiment for 35 days. Monitor and record daily:

- O₂ and CO₂ concentrations in the gas loop.

- Incident light intensity (as controlled by the algorithm).

- Culture OD₅₆₀ and pH.

- Harvesting & Analysis: At the end of the experiment, harvest biomass for biochemical analysis (e.g., protein, pigment content).

4. Anticipated Results: The system with nitrate and urea is expected to maintain the O₂ setpoint of 20.3%, while the ammonium-based system may struggle, potentially reaching a maximum of only 19.5% O₂, indicating inhibition or reduced photosynthetic efficiency [24].

Diagram 2: Cyanobacteria O2 production experimental workflow.

Protocol: Integrated Sabatier-BLSS Performance Testing

This protocol outlines a test for evaluating the interface and mass balance between a Sabatier reactor and a cyanobacteria PBR.

1. Objective: To characterize the gas exchange and resource recovery when diverting a variable fraction of the crew's CO₂ output from the Sabatier reactor to a cyanobacteria PBR.

2. Materials:

- Sabatier reactor engineering model.

- Limnospira indica PBR system.

- Mass Flow Controllers (MFCs) for CO₂, H₂, and air.

- Gas analyzers for O₂, CO₂, and CH₄.

- Water collection and measurement apparatus.

3. Methodology:

- Baseline PC Operation: Operate the Sabatier reactor with a simulated crew CO₂ input (e.g., 3.24 kg/day for a 3-person crew [6]) and stoichiometric H₂. Measure CO₂ conversion efficiency, CH₄ production, and water recovery.

- Integrated Operation: Divert a fraction (e.g., 10%, 25%, 50%) of the incoming CO₂ stream to the PBR. Ensure the Sabatier reactor's H₂ input is adjusted accordingly.

- Monitoring: Monitor both systems for 14 days. Record:

- Input and output gas compositions for both units.

- Water produced by the Sabatier reactor.

- O₂ production rate from the PBR.

- Biomass accumulation rate in the PBR.

4. Data Analysis: Calculate the overall system closure for carbon and oxygen. Determine the optimal CO₂ split ratio that maximizes O₂ production and water recovery while maintaining safe CO₂ levels in the simulated cabin atmosphere.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for BLSS and PC Life Support Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Limnospira indica | Model cyanobacterium for O₂ production, CO₂ sequestration, and biomass. | PCC 8005 strain; used in ESA's MELiSSA project [24]. |

| Zarrouk's Medium | Standardized growth medium for Limnospira cultivation. | Can be modified to use different nitrogen sources (NO₃⁻, Urea, NH₄⁺) [24]. |

| Photobioreactor (PBR) | Controlled environment for cultivating photosynthetic organisms. | Requires integrated lighting, pH/DO/temperature sensors, and gas exchange capabilities [6] [24]. |

| Sabatier Reactor | Converts CO₂ and H₂ into methane and water. | Uses a ruthenium or nickel-based catalyst [6]. |

| Mass Spectrometer | Speciated, real-time monitoring of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and gases. | e.g., SIFT-MS or PTR-ToF-MS; for trace gas analysis [25]. |

| Automated Gas Chromatograph (Auto-GC) | Periodic, high-precision analysis of gas composition. | Used for community air monitoring; can be adapted for cabin air [25]. |

| Nitrogen Sources | Simulating waste streams for cyanobacterial cultivation. | Sodium Nitrate (control), Urea, Ammonium Chloride [24]. |

The integration of CO₂ capture, Sabatier reactors, and cyanobacteria-based oxygen production represents a promising hybrid architecture for future life support systems. The quantitative data and experimental protocols provided herein offer a foundation for researchers to validate and advance this technology. Ground demonstration projects, such as those conducted for the MELiSSA loop, are critical de-risking steps on the path to deploying these systems for sustained human exploration of the Moon and Mars. Future work must focus on closing the water and nutrient loops further by integrating higher plants and refining the control systems for these complex, synergetic ecosystems [4] [8].

The integration of physiochemical and biological systems is paramount for advancing closed-loop life support for long-duration space missions. Current physiochemical systems, like the urine processor assembly (UPA) on the International Space Station (ISS), recover over 90% of water but leave concentrated brines containing valuable nutrients [26]. This application note details protocols for coupling the UPA with downstream biological processes to recover these nutrients, transforming waste into a resource for bioregenerative life support systems (BLSS). This hybrid approach is a critical step toward the logistical biosustainability required for future lunar bases and Mars missions [11] [27].

Performance Data and System Comparison

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Urine Processing Technologies

| Technology / System | Primary Function | Water Recovery Rate | Nutrient Output/Handling | Technology Readiness Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISS Urine Processor Assembly (UPA) [26] | Water recovery from urine via distillation | ~75% from urine | Produces a nutrient-rich brine effluent | Operational on ISS |

| ISS Brine Processor Assembly (BPA) [26] | Further water extraction from UPA brine | Increases overall system recovery to 98% | Produces a dry, solid nutrient concentrate | Operational on ISS |

| Brine Integrator | Manages BPA output for nutrient recycling | N/A | Conditions solid brine for biological processing | Conceptual / Prototype |

| Microbial Electrochemical Systems [28] | Nutrient recovery and fertilizer production from source-separated urine | N/A | Can generate nitrogen-rich liquid fertilizers | Lab-scale research |

| Struvite Precipitation [28] | Phosphorus recovery from urine | N/A | Produces Struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate) fertilizer | Pilot-scale demonstrations |

| Pine Bark (PB) Ash Filtration [29] | Nutrient recovery and solid fertilizer production via dehydration | N/A | Produces a solid fertiliser with 9.7% N, 1.5% P, 8.4% K | Lab-scale research |

Table 2: Analysis of Recovered Urine-Derived Fertilizers

| Fertilizer Product | Key Nutrients | Reported Efficacy vs. Commercial Fertilizer | Production Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Struvite [28] | Phosphorus (P), Nitrogen (N) | N/A | Physiochemical Precipitation |

| Calcium Phosphate [28] | Phosphorus (P) | N/A | Physiochemical Precipitation |

| Ammonium Sulphate [28] | Nitrogen (N) | N/A | Membrane Processes, Physiochemical |

| Nutrient-Rich Liquid [28] | N, P, K | N/A | Microbial Electrochemical, Hybrid Systems |

| Pine Bark Ash Product [29] | N, P, K | Superior N and P uptake by ryegrass and maize; better growth in weight and size of basil plants. | Dehydration with pine bark ash media |

| Solid Fertiliser (N, P, K, NaCl, KCl) [28] | N, P, K, Sodium (Na), Chlorine (Cl) | N/A | Integrated/Treatment Trains |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Conditioning Brine Processor Assembly (BPA) Effluent for Biological Processing

This protocol describes the preparation of the solid nutrient concentrate produced by a system analogous to the ISS BPA for use as a substrate in biological nutrient recovery.

I. Materials and Reagents

- Solid brine effluent from BPA

- Sterile, deionized water

- Reagent 1: Pine Bark Ash. Function: A high-pH (alkaline) filtration and conditioning media that enhances nitrogen retention and promotes the formation of stable fertilizer products during dehydration [29].

- Reagent 2: Calcium Hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂). Function: A chemical additive used to modify urine pH, inactivate the urease enzyme to prevent ammonia volatilization, and precipitate phosphorus into a recoverable solid form [28] [29].

- Analytical equipment: pH meter, analytical balance, magnetic stirrer

II. Methodology

- Solubilization: Precisely weigh 10 g of solid BPA effluent. Gradually add 100 mL of sterile, deionized water under constant stirring to create a concentrated nutrient solution.

- pH Adjustment and Conditioning: Adjust the pH of the solution. For subsequent dehydration, raise the pH to >10 using a calcium hydroxide solution or pine bark ash to suppress ammonia volatilization. For microbial processing, adjust the pH to a neutral range (6.5-7.5) as required.

- Filtration: Filter the conditioned solution using a vacuum filtration system with pine bark ash as a filter media to capture particulates and initiate nutrient adsorption [29].

- Product Formation: The filtered solution is ready for biological processing. The filter media itself, now enriched with nutrients, can be dehydrated to form a solid fertilizer product.

Protocol B: Biological Production of Urine-Derived Fertilizer Using Pine Bark Media

This protocol is adapted from recent research for creating a solid, urine-derived fertilizer using pine bark (PB) and its derivatives, simulating the use of BPA concentrate [29].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Source-separated human urine or synthetic BPA effluent solution (from Protocol A)

- Pine bark media: Feedstock (raw, ground), Biochar (pyrolyzed at 350°C and 650°C), and Ash (produced by heating feedstock at 750°C) [29]

- Dehydration ovens (45°C and 60°C)

- Glass containers with lids

II. Methodology

- Media Preparation: Weigh 50 g of the selected pine bark media (feedstock, biochar, or ash) into individual glass containers.

- Urine/Effluent Addition: Add the urine or BPA effluent solution to the media. Stir the mixture vigorously for 5 seconds to ensure full integration [29].

- Dehydration: Place the open containers in an oven pre-heated to either 45°C or 60°C. The dehydration process is complete when a solid, friable product is achieved.

- Curing and Storage: Periodically stir the mixture during dehydration to ensure even drying. Once dehydrated, the solid product is milled into a powder and stored in a sealed container for later agronomic testing.

III. Agronomic Efficacy Testing

- Soil Incubation: Apply the dehydrated product to a loam soil at a rate equivalent to 100 kg N per hectare. Incubate the soil at field capacity and 25°C [29].

- Nutrient Release Analysis: Conduct destructive sampling at days 0, 7, 14, 21, 28, 42, and 56. Analyze the soil for pH, ammonium-N, nitrate-N, and extractable P.

- Data Interpretation: Monitor the conversion of ammonium-N to nitrate-N. Products like pine bark ash dehydrated at 45°C have been shown to maintain high nitrate-N levels (~38 mg kg⁻¹), indicating efficient N recovery and release [29].

Process Visualization and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for managing urine and recovering water and nutrients, connecting the physiochemical hardware of the ISS with downstream biological processing methods.

Integrated Urine Processing Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Hybrid Life Support Research

| Material / Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Pine Bark (PB) Feedstock [29] | An acidic (pH ~3.0) organic waste material used as a substrate to recover nutrients from urine via dehydration; its low pH helps suppress urease activity, reducing nitrogen loss. |

| PB Biochar [29] | A porous carbon-rich material produced by pyrolyzing pine bark. Used to absorb and retain nutrients from liquid waste, creating a carbon-rich solid fertilizer that improves soil fertility and carbon sequestration. |

| PB Ash [29] | A high-pH alkaline material used to modify urine pH, inactivate urease, and produce a nutrient-rich solid fertilizer product through dehydration. Demonstrated to be highly effective in increasing nitrogen availability. |

| Calcium Hydroxide (Ca(OH)₂) [28] [29] | A chemical reagent used for pH modification and phosphorus precipitation in urine, leading to the production of calcium phosphate fertilizers. |

| Artificial Human Urine (AHU) [29] | A standardized synthetic solution containing urea, uric acid, creatinine, and salts, used for controlled and reproducible experiments without the variability of real urine. |

| Struvite [28] | A crystalline fertilizer product (magnesium ammonium phosphate) recovered from urine, providing a slow-release source of phosphorus and nitrogen. |

The integration of robust food production systems is a critical component for the advancement of long-duration human space exploration and the development of closed-loop life support. These systems must optimize plant characterization and cultivation to achieve logistical biosustainability, reducing reliance on resupply missions from Earth [11]. Current approaches for human space habitation predominantly depend on physical/chemical-based Environmental Control and Life Support Systems (ECLSS), which face significant constraints from logistics costs, technological limits, and human health risks [11]. Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS), which utilize biological components like plants and microalgae, present a viable path toward creating self-sustaining habitats by regenerating air and water and producing food [11]. This document provides detailed application notes and protocols for the implementation and study of such systems, framed within the broader context of integrating physicochemical and biological research for advanced life support.

Effective planning for closed-environment food production requires a clear understanding of performance metrics and comparative technologies. The following tables summarize key quantitative data relevant to system design.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Cultivation Technologies for Closed Environments

| Technology / Organism | Key Metric | Reported Value | Significance for Closed Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microalgae (General) | CO₂ Fixation Efficiency | 10-50x higher than terrestrial plants [30] | Superior air revitalization potential. |

| Microalgae (Specific) | CO₂ Fixed per Biomass | 1.83 tons of CO₂ per ton of algal powder [30] | Enables precise mass balancing for atmosphere management. |

| Microalgae in Aquaculture | Carbon Emission Reduction | Potential to reduce emissions from 1.8 kg to 3.3 kg CO₂e/kg salmon [30] | Model for integrated, multi-trophic closed systems. |

| Precision Agriculture (UAV-based) | Phenotyping Data Acquisition | High-throughput, efficient, low-cost [31] | Platform for non-destructive, continuous plant characterization. |

Table 2: 2025 Sustainable Agriculture Trends with Relevance to Closed Systems [32]

| Trend | Estimated Adoption in 2025 | Potential Environmental Impact Reduction | Application to Closed Environments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Responsible Sourcing & Traceability | 62% | 35% | Model for supply chain integrity and input verification in BLSS. |

| Precision Agriculture Technologies | 55% | 28% | Directly applicable to resource optimization (water, nutrients, light) in controlled agriculture. |

| Biological Inputs / Green Chemistry | 39% | 22% | Reduces reliance on synthetic chemicals, aligning with closed-loop recycling. |

| Circular Economy & Waste Valorization | 33% | 16% | Core principle for BLSS; converting waste streams into resources. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: High-Throughput Plant Phenotyping Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs)

This protocol outlines a methodology for non-destructive, high-frequency monitoring of plant growth and health in controlled environments, adapted from field-based precision agriculture [31].

1. Objective: To acquire quantitative phenotypic data (e.g., plant height, Leaf Area Index (LAI), disease presence) rapidly and non-destructively for a large population of plants under controlled conditions.

2. Materials:

- Multirotor UAV platform.

- Multispectral or hyperspectral sensor.

- Ground control points (for spatial referencing).

- Data processing workstation with appropriate software (e.g., Python with computer vision libraries, specialized photogrammetry software).

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Mission Planning. Define the flight path over the cultivation area to ensure complete coverage. Set flight altitude and image overlap (e.g., 80% front and side overlap) based on the required spatial resolution.

- Step 2: Sensor Calibration. Perform radiometric calibration of the multispectral sensor using a calibration panel to ensure data consistency across flights.

- Step 3: Data Acquisition. Conduct autonomous flights at regular intervals (e.g., daily or weekly). Ensure consistent lighting conditions, preferably using controlled growth chamber lighting to eliminate shadows.

- Step 4: Data Pre-processing. Use structure-from-motion (SfM) photogrammetry to generate orthomosaic images and digital surface models (DSM) from the captured imagery.

- Step 5: Phenotypic Trait Extraction.

- Plant Height: Calculate by subtracting a digital terrain model (DTM) of the growing medium surface from the DSM of the plant canopy [31].

- Leaf Area Index (LAI): Derive using vegetation indices (e.g., NDVI) from multispectral data, established through regression models with ground-truthed LAI measurements [31].

- Disease Detection: Utilize machine learning algorithms trained on annotated image datasets to identify and classify disease symptoms or nutrient stress patterns [31].

4. Data Analysis: Time-series analysis of extracted traits allows for the assessment of growth rates, response to environmental changes, and early detection of stressors.

Protocol: Integration of Microalgae for Carbon Capture and Recycling

This protocol details the use of microalgae photobioreactors (PBRs) within a closed system for atmospheric regeneration and biomass production, drawing from successful terrestrial analogs [33] [30].

1. Objective: To utilize microalgae for the capture of carbon dioxide from the habitation atmosphere and the production of valuable biomass for food, feed, or other applications.

2. Materials:

- Tubular or flat-panel photobioreactor (PBR) system.

- CO₂-rich gas stream (e.g., from crew respiration or ECLSS).

- Microalgae strain (e.g., Chlorella sp., Scenedesmus sp.).

- Nutrient medium (containing N, P, and micronutrients).

- Harvesting system (e.g., centrifuge, membrane filtration).

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: System Sterilization. Sterilize the PBR and all connecting tubing to prevent microbial contamination.

- Step 2: Inoculation. Inoculate the sterile PBR with a log-phase microalgae culture in a suitable nutrient medium.

- Step 3: Cultivation Operation.

- Continuously bubble the CO₂-rich gas stream (at a controlled concentration, e.g., 1-5%) through the culture.

- Maintain optimal temperature using a heating/cooling system integrated with the PBR [33].