How Wearable Plant Sensors Work: A Guide to Precision Agriculture for Researchers and Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of wearable plant sensor technology, a cutting-edge tool for precision agriculture.

How Wearable Plant Sensors Work: A Guide to Precision Agriculture for Researchers and Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of wearable plant sensor technology, a cutting-edge tool for precision agriculture. Aimed at researchers and scientists, it explores the foundational principles of these sensors, which are categorized into physical, chemical, and electrophysiological types for monitoring parameters like growth, sap flow, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and microclimate. The content details their operational mechanisms, integration with IoT and AI, and real-world applications in disease detection and resource optimization. It also critically examines current technical challenges, comparative advantages over traditional monitoring methods, and validates their performance through case studies and market trends. The conclusion synthesizes the transformative potential of this technology for data-driven plant science and suggests future directions for research and development.

The Science Behind Wearable Plant Sensors: Principles and Classifications

The concept of wearable technology, once predominantly associated with human healthcare, has successfully transitioned into the agricultural domain, giving rise to wearable plant sensors. These are flexible, stretchable, and miniaturized analytical devices that can be directly and conformally attached to various plant parts—including stems, leaves, and fruits—for continuous, in-situ monitoring of physiological and environmental parameters [1] [2]. This innovation is driven by the urgent need for precision agriculture to address global challenges such as population growth, climate change, and cultivated land reduction, with the goal of enhancing crop productivity and sustainability [3] [4] [2].

Fundamentally, wearable plant sensors represent a paradigm shift from traditional monitoring methods, which often provide discontinuous measurements with low spatial and temporal resolution [2]. By providing non-invasive, real-time data on plant health status, these sensors empower farmers and researchers to make precise and timely decisions regarding irrigation, fertilizer application, and pest control, thereby optimizing resource use and reducing environmental impact [1] [5]. Recognized by the World Economic Forum as a Top 10 Emerging Technology in 2023, wearable plant sensors are poised to revolutionize crop production and management [1] [5].

Technical Fundamentals: How Wearable Plant Sensors Work

Core Components and Design Principles

A typical wearable plant sensor is composed of three main elements arranged in a sandwich-like structure [6]:

- Flexible/Stretchable Substrate: This is the base layer that provides mechanical support and ensures conformal contact with the irregular and curvilinear surfaces of plants. Traditional substrates include petrochemical-based polymers like polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and polyimide (PI). However, research is increasingly focused on sustainable and biodegradable materials such as polylactic acid (PLA), starch, and cellulose derivatives to minimize environmental impact after use [1].

- Sensing Element/Electrode: This is the active layer responsible for detecting specific physical, chemical, or electrophysiological signals. It utilizes materials like conductive inks, graphene, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and metallic nanostructures (e.g., gold, silver) to transduce a biological response into an electrical signal (e.g., changes in resistance, capacitance, or voltage) [1] [6].

- Encapsulation Material: This top layer protects the sensitive sensing element from environmental factors such as moisture, dust, and mechanical abrasion, thereby ensuring the stability and longevity of the device. Ecoflex and PDMS are commonly used for this purpose [6].

The design and fabrication of these sensors employ techniques such as 3D printing, inkjet printing, and direct writing, which allow for programmable compositions and patterning while reducing energy consumption and waste [1].

Sensing Mechanisms and Data Acquisition

Wearable plant sensors are classified based on the type of signal they detect, which directly corresponds to their sensing mechanism and the health information they provide. The primary categories are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Classification of Wearable Plant Sensors by Detection Signal and Mechanism

| Sensor Category | Detected Signals/Parameters | Common Sensing Materials & Mechanisms | Application in Plant Health Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Sensors | Strain (growth deformation), Temperature, Humidity, Light Intensity [3] [4] | Graphite/CNT-based inks [6]; measures resistance change due to mechanical strain or environmental variation. | Monitors stem/ fruit growth, leaf water status, and microclimate [3] [6]. |

| Chemical Sensors | Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), pH, ions, pesticide residues, reactive oxygen species (ROS) [3] [7] [1] | Functionalized graphene oxide (rGO) [6]; ligand-binding alters electrical conductivity. | Detects early signs of disease, pest infestation, nutrient deficiency, and abiotic stress [1] [6]. |

| Electrophysiological Sensors | Action Potentials, Variation Potentials [3] [7] | Polyaniline-based hydrogels [6]; measures electrical potential differences on plant surfaces. | Investigates plant's internal electrical communication and response to stimuli [7] [2]. |

The data acquired by these sensors can be transmitted via wired or wireless connections to external devices like phones or laptops for further analysis. The integration of flexible circuits and wireless communication modules (e.g., Bluetooth, LoRaWAN) is crucial for creating standalone sensing systems suitable for large-scale field deployment [6] [8].

System Architecture and Data Integration for Precision Agriculture

The operational workflow of a wearable plant sensor system involves a seamless integration of sensing, data transmission, and analysis, forming a closed-loop for intelligent farm management.

Diagram 1: System architecture for wearable plant sensor networks, showing the flow from data sensing to user decision-making.

The Role of IoT and Energy Harvesting

As shown in Diagram 1, data from multiple sensors are processed by a microcontroller and transmitted wirelessly to cloud platforms. This integration with the Internet of Things (IoT) enables real-time monitoring and control across vast agricultural areas [8]. A critical component for scalability is energy autonomy. Promising solutions include integrating solar panels, as seen in the Gaia Communication System [9], or exploring bioenergy and triboelectric energy harvesting from plant motion or rainfall [8].

Advanced Data Analytics with Machine Learning and AI

The continuous, multimodal data streams from wearable sensors are a prime candidate for analysis with Machine Learning (ML) and Artificial Intelligence (AI). These technologies can identify complex patterns that are imperceptible to the human eye, such as correlating specific VOC profiles with early-stage fungal infections or predicting yield based on growth rate data [8]. This analytical power transforms raw data into predictive insights and decision-support tools, forming the core of a feedback loop for autonomous irrigation systems or nutrient delivery in smart greenhouses [8].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

To ensure that developed sensors provide accurate and biologically relevant data, rigorous experimental validation is required. The following workflow outlines a standard protocol for testing and validating a new wearable plant sensor.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for validating a wearable plant sensor.

Detailed Experimental Methodology:

Sensor Fabrication and Characterization: Fabricate the sensor using methods like inkjet printing or laser scribing. Characterize its physical and electrical properties using techniques such as Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for morphology, Raman spectroscopy for material identity, and mechanical testers for flexibility and stretchability [6]. Key performance metrics to establish include sensitivity, detection limit, and operational range.

Controlled Environment Testing: Initial tests should be performed in growth chambers or greenhouses where environmental variables (light, temperature, humidity) can be precisely controlled. This allows for the establishment of a baseline sensor response and the study of plant-sensor interactions without confounding field variables [10].

Plant Attachment and Biocompatibility Check: The sensor must be attached to the plant organ of interest (e.g., leaf, stem) ensuring intimate contact without hindering natural growth or causing damage. The plant should be monitored for signs of stress, such as discoloration or necrosis at the attachment site, to confirm the sensor's biocompatibility and non-invasiveness [2] [10].

In-situ Data Logging and Gold Standard Comparison: Record the sensor's output continuously over a defined period. Simultaneously, validate the readings against established "gold standard" laboratory methods. For example, a wearable moisture sensor's data should be correlated with gravimetric measurements of soil water content or a pressure bomb's measurement of leaf water potential [10].

Field Trial and Durability Assessment: Deploy the sensor in a real agricultural setting. This phase assesses the sensor's robustness against varying weather conditions (rain, wind, UV exposure), its long-term stability (often over weeks or months), and the reliability of its power and data transmission systems [6] [10].

Data Analysis and Model Validation: Analyze the collected data to establish correlations between sensor signals and plant health status. If ML models are developed for prediction, their accuracy must be validated against ground-truthed observations of plant health, such as visual disease scoring or yield measurements at harvest [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Reagents for Wearable Plant Sensor Development

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function in Sensor Development |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate Materials | Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), Polyimide (PI), Polylactic Acid (PLA), Cellulose derivatives [1] [6] | Provides flexible, stretchable, and sometimes biodegradable support for the sensing element. |

| Conductive/Sensing Materials | Graphene & Graphene Oxide (GO/rGO), Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), Gold/Titanium/Platinum metal films, Conductive inks (graphite, carbon) [1] [6] | Forms the active sensing layer; transduces physical, chemical, or electrical changes into a measurable electrical signal. |

| Fabrication Techniques | 3D Printing, Inkjet Printing, Direct Writing/Laser Scanning, Photolithography [1] [6] | Used for patterning and manufacturing sensors with controlled morphologies and designs. |

| Characterization Tools | Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), Mechanical Testers, LCR Meters [6] | Used to analyze sensor morphology, chemical composition, mechanical properties, and electrical performance. |

Despite their significant potential, the widespread adoption of wearable plant sensors faces several challenges. Key issues include ensuring long-term durability under harsh field conditions, achieving scalability of manufacturing for large farms, and developing truly biodegradable and sustainable sensor systems to avoid electronic waste [1] [8] [10]. Furthermore, the cost-effectiveness of these technologies must be demonstrated for adoption by farmers worldwide [10].

Future research is directed towards creating fully autonomous, self-powered systems that integrate energy harvesting, robust wireless communication, and sophisticated data analytics in a single, compact package [8]. There is also a growing emphasis on biomimicry and learning from indigenous knowledge; for instance, the Gaia Communication System was inspired by the sensory abilities of ants and bees and the deep listening practices of indigenous cultures [9].

In conclusion, wearable plant sensors represent a transformative innovation at the intersection of materials science, electronics, and plant biology. By providing a direct, continuous, and intuitive window into plant physiology, they empower a new era of data-driven precision agriculture. As the technology matures through cross-disciplinary collaboration, it holds the profound promise of enhancing global food security, optimizing resource use, and fostering a deeper, more empathetic connection with the ecosystems that sustain us.

In modern agriculture, the rising demand for food security has intensified the need for intelligent plant monitoring systems to ensure healthy crop growth [3]. Wearable plant sensors represent a technological breakthrough for precision agriculture, enabling real-time, in-situ monitoring of physiological and environmental biomarkers [6]. Unlike conventional rigid sensors or destructive sampling methods, these flexible, biocompatible devices attach directly to plant surfaces—including stems, leaves, and fruits—to provide continuous data streams on plant health status [11]. By converting biological signals into analyzable electrical data, wearable sensors offer unprecedented insights into plant physiology, allowing for timely interventions and optimized resource management [6]. This technical guide examines the three core sensing modalities—physical, chemical, and electrophysiological—that form the foundation of plant wearable technology, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for their application in precision agriculture research.

Core Sensing Modalities in Plant Wearables

Physical Signal Monitoring

Physical sensors track mechanical and environmental parameters related to plant growth and microclimate conditions. These sensors are designed to detect dimensional changes, mechanical stress, and ambient environmental factors that directly influence plant development and health.

Table 1: Physical Signal Sensor Types and Applications

| Sensor Type | Measured Parameters | Sensing Mechanism | Typical Materials | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain Sensors | Plant growth, elongation, deformation | Piezoresistive, Capacitive, Piezoelectric | CNT/graphite inks, graphene, hydrogels [6] | Monitoring stem diameter changes, leaf expansion [11] |

| Microclimate Sensors | Temperature, humidity, light | Resistive, Capacitive | ZnIn2S4 nanosheets, graphene oxide (GO) [6] | Leaf surface temperature, humidity monitoring [3] |

| Pressure Sensors | Turgor pressure, mechanical stress | Piezoresistive, Capacitive | Conductive polymer composites, ecoflex [12] | Fruit growth monitoring, drought stress detection [6] |

The working principle of piezoresistive flexible strain sensors involves converting mechanical deformation into resistance changes. These sensors typically comprise a flexible electrode, conductive material, and flexible substrate [12]. The fundamental relationship is defined by R = ρL/S, where resistance (R) changes with variations in length (L) or cross-sectional area (S) of the conductive material [12]. When incorporated into a less-conductive matrix material, conductive fillers form networks whose connectivity changes under deformation, significantly altering resistance [12].

For microclimate monitoring, flexible humidity sensors operate based on changes in the dielectric constant of moisture-sensitive materials, while temperature sensors typically leverage the thermoresistive effect in conductive materials [12]. These sensors provide crucial data on environmental conditions at the plant-air interface, enabling precise correlation between microclimate and plant physiological status [11].

Chemical Signal Monitoring

Chemical sensors detect and quantify molecular biomarkers indicative of plant health, stress responses, and metabolic activities. These sensors provide critical information about plant-pathogen interactions, nutrient status, and defense mechanisms through monitoring of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), ions, pH, and pesticide residues [3] [13].

Table 2: Chemical Sensor Types and Characteristics

| Sensor Type | Target Analytes | Sensing Mechanism | Detection Range | Selectivity Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas/VOC Sensors | Ethylene, terpenoids, aldehydes | Chemiresistive, Semiconductor | ppm to ppb levels [6] | Functionalized ligands, molecular imprinting [6] |

| Ion Sensors | Ca²⁺, K⁺, NO₃⁻, pH | Potentiometric, Amperometric | Varies by ion | Ion-selective membranes [13] |

| Pesticide Detectors | Organophosphorus, carbamates | Electrochemical | nM to μM [6] | Enzyme inhibition (e.g., acetylcholinesterase) [6] |

Semiconductor-type gas sensors operate primarily through two well-established theoretical models: surface oxygen ion adsorption for metal oxide semiconductors and charge transfer for two-dimensional materials like graphene [12]. For n-type metal oxides in air, oxygen molecules adsorb onto the material surface, reacting with electrons to form oxygen anions and creating an electron depletion layer that increases resistance [12]. When exposed to reducing gases like CO, the gas molecules react with oxygen anions, releasing electrons back into the material and decreasing resistance [12].

Electrochemical sensors for pesticide detection typically rely on enzyme inhibition principles. For example, organophosphorus pesticides can be detected by monitoring their inhibitory effect on acetylcholinesterase activity, which is measured electrochemically [6]. These sensors enable rapid, real-time on-site detection of pesticide residues without extensive sample pretreatment, providing valuable tools for sustainable agricultural management [6].

Electrophysiological Signal Monitoring

Electrophysiological sensors measure electrical potentials and ion fluxes across plant membranes and tissues, providing insights into plant neural activity, stress responses, and systemic signaling. These signals represent a direct communication pathway within plants that can indicate various physiological states and environmental adaptations.

Plants generate and transmit electrical signals as part of their response to environmental stimuli, including biotic and abiotic stresses [3]. These electrophysiological signals can propagate through the plant's vascular system and provide early warnings of stress conditions before visible symptoms appear. Wearable sensors for electrophysiological monitoring employ electrodes placed in direct contact with plant surfaces to detect these subtle electrical potentials non-invasively [3].

The measurement principles are similar to those used in biomedical applications, including potentiometric measurements of membrane potentials and amperometric detection of ion fluxes. However, plant electrophysiology presents unique challenges due to the complex structure of plant tissues, waxy cuticles that impede electrical contact, and the relatively low amplitude of plant action potentials compared to animal systems [3]. Advanced electrode designs using conductive hydrogels and nanostructured materials have been developed to improve signal acquisition while maintaining biocompatibility with plant surfaces [3].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sensor Fabrication and Characterization

The development of wearable plant sensors requires specialized fabrication approaches that prioritize flexibility, biocompatibility, and environmental stability. Most wearable sensors employ a sandwich structure with three main components: a flexible/stretchable substrate, a sensing element, and an encapsulation material [6].

Representative Protocol: Flexible Strain Sensor Fabrication

- Substrate Preparation: Select and clean a flexible substrate (e.g., polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), polyimide, or biodegradable polymers) [6].

- Electrode Patterning: Create conductive patterns using techniques such as laser-induced graphene, screen printing, or deposition of metal thin films [6].

- Sensitive Material Integration: Apply the active sensing material (e.g., CNT/graphite composites, conductive polymers) via drop-casting, spin-coating, or direct writing [12] [6].

- Encapsulation: Apply a protective layer (e.g., PDMS, ecoflex) to ensure mechanical stability and environmental protection while allowing measurement functionality [6].

- Characterization: Perform structural (SEM, Raman spectroscopy), mechanical (tensile testing), and electrochemical (impedance spectroscopy) characterization to validate sensor performance [6].

Key Performance Metrics:

- Sensitivity: Gauge factor for strain sensors (e.g., 3.9-2.9 kΩ/mm for fruit growth sensors) [6].

- Stability: Operational lifetime under field conditions (e.g., 14-45 days for various reported sensors) [6].

- Detection Range: Minimum and measurable signals (e.g., strain from 1% to 8% for growth monitoring) [6].

Plant Integration and Validation

Successful deployment of wearable plant sensors requires careful consideration of plant-sensor interfaces to minimize interference with natural physiological processes.

Integration Protocol:

- Surface Preparation: Gently clean the plant surface without damaging the cuticle or epidermal layers.

- Sensor Attachment: Apply sensors using biocompatible adhesives or mechanical fixation that allows for natural growth and movement [11].

- Signal Validation: Correlate sensor readings with established measurement techniques (e.g., validate growth measurements with calipers, VOC detection with GC-MS) [6].

- Interference Assessment: Monitor potential effects of sensor attachment on gas exchange, photosynthesis, and growth patterns [3].

Experimental Controls:

- Include plants without sensors to account for any potential growth effects from the attachment process.

- Use multiple sensor placements on the same plant to account for positional variability.

- Implement environmental controls to distinguish between treatment effects and natural variations.

Signaling Pathways and System Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from signal detection to data interpretation in wearable plant sensor systems:

Wearable Plant Sensor System Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Wearable Plant Sensor Research

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Flexible Substrates | PDMS, Ecoflex, Polyimide, Hydrogels [6] | Provides mechanical support and flexibility for conformal contact with plant surfaces |

| Conductive Materials | CNT/graphite inks, graphene, conductive polymers (PANI, PEDOT:PSS) [6] | Forms sensing elements and electrodes for signal transduction |

| Sensing Nanomaterials | ZnIn2S4 nanosheets, reduced graphene oxide (rGO), MXenes [6] | Enhances sensitivity and selectivity for specific analytes |

| Encapsulation Materials | PDMS, SU-8, Ecoflex, biodegradable polymers [6] | Protects sensing elements from environmental factors while maintaining functionality |

| Functionalization Agents | Specific ligands, enzymes, molecularly imprinted polymers [6] | Provides selectivity for target chemical and biological analytes |

Wearable plant sensors for monitoring physical, chemical, and electrophysiological signals represent a transformative technology for precision agriculture research. These sensors provide unprecedented capabilities for real-time, in-situ monitoring of plant health and environmental conditions, enabling data-driven agricultural management decisions. While significant progress has been made in sensor development, challenges remain in scalability, long-term stability under field conditions, and integration of multiple sensing modalities into comprehensive plant health monitoring systems [11]. Future research directions should focus on developing biodegradable sensor materials, enhancing wireless communication capabilities, and integrating artificial intelligence for advanced data analysis and predictive modeling [11]. As these technologies mature, wearable plant sensors are poised to become vital tools in building smarter, more sustainable agricultural systems capable of addressing global food security challenges.

The rising demand for food, driven by global population growth, presents a critical challenge to agricultural systems worldwide. In this context, precision agriculture has emerged as a vital approach to enhancing crop productivity through data-driven management practices. Plant wearable sensors represent a revolutionary technological advancement in this field, enabling researchers to monitor plant physiological processes in real-time with minimal invasiveness. Unlike traditional monitoring methods that often rely on destructive sampling or complex instrumentation, these flexible electronic devices can be directly attached to plant surfaces, converting biological signals into readable electrical data while allowing normal plant functions to continue [11]. This capability provides unprecedented access to continuous physiological information, offering researchers a powerful tool for understanding plant responses to environmental stresses, resource availability, and genetic manipulations.

The fundamental advantage of wearable sensors lies in their biocompatible design and contact measurement mode. Their flexibility, lightweight construction, and air/water/light-permeable properties enable them to cohabitate harmlessly with plants over extended periods without interfering with essential physiological processes [14]. This direct attachment facilitates the monitoring of internal plant parameters that were previously difficult to measure continuously, such as sap flow dynamics and volatile organic compound emissions in response to stress events. As the field of plant phenomics continues to evolve—shifting from primarily morphology-based assessments to more reliable physiological trait monitoring—wearable sensors are poised to become an indispensable component of the researcher's toolkit for precise, high-throughput plant analysis [15] [14].

Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs): The Chemical Language of Plants

VOC Biosynthesis and Function

Plants emit an exceptional variety of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which together serve as a complex chemical language facilitating intra-plant, inter-plant, plant-animal, and plant-microbe interactions [16]. These secondary metabolites include over 1,700 identified compounds from 90 different plant species, primarily consisting of terpenoids, alkaloids, polyketides, carbohydrates, and flavonoids [11]. VOCs are released into the environment in response to both biotic and abiotic stresses, making them valuable indicators of plant health status [11] [17]. The emission, composition, distribution, and effective range of these infochemicals depend on temperature and atmospheric chemistry in addition to their physicochemical properties, creating a dynamic communication system that is directly affected by ongoing climate change [16].

From an ecological perspective, VOCs serve multiple functions that are critical to plant survival and reproduction. They act as direct and indirect defense mechanisms against herbivores and pathogens, attract pollinators for successful reproduction, mediate various interactions between plants and their environment, and even facilitate plant-plant communication [16] [17] [18]. In horticultural crops specifically, aroma compounds play a dual role in attracting both pollinators and humans who consume the fruit, making VOC profiles an important quality trait for consumer preferences [18]. The intricate roles of VOCs as mediators of plant communication and adaptation are particularly relevant in the context of climate change, as changing environmental conditions may disrupt these finely tuned chemical signaling systems [17].

Wearable Sensors for VOC Detection

Recent advancements in flexible sensing platforms have enabled the development of wearable sensors capable of continuous, real-time monitoring of VOC emissions from plant surfaces. These sensors typically utilize chemiresistive profiling mechanisms, where the presence of specific VOCs causes measurable changes in the electrical resistance of specialized sensing materials [11]. One pioneering study demonstrated a graphene-based sensor array that could be directly attached to tomato leaves to monitor stress-induced VOC emissions, providing early detection of pathogen attacks before visible symptoms appeared [15].

The development of effective VOC sensors requires careful consideration of several technical challenges. Selectivity remains a significant hurdle, as plant VOC profiles consist of complex mixtures of compounds that may have contrasting biological meanings. Researchers are addressing this challenge through the development of sensor arrays with multiple sensing elements, each tuned to detect different classes of VOCs [11] [7]. Additionally, environmental interference from humidity, temperature fluctuations, and air movement must be compensated for through sophisticated sensor designs and data analysis algorithms. Recent innovations include the incorporation of nanoporous sensing materials with large surface areas for enhanced sensitivity and the integration of reference sensors to account for background environmental variations [11].

Table: Key Volatile Organic Compound Classes and Their Significance in Plant Physiology

| VOC Class | Example Compounds | Biosynthetic Pathways | Physiological Significance | Detection Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terpenoids | Limonene, Linalool | Mevalonate (MVA) and Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) pathways | Defense against herbivores, pollinator attraction, thermal tolerance | High volatility, structural diversity, low concentrations |

| Green Leaf Volatiles (GLVs) | (Z)-3-Hexenol, (Z)-3-Hexenyl acetate | Lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway | Direct defense, inter-plant signaling, wound response | Rapid emission kinetics, environmental degradation |

| Benzenoids/Phenylpropanoids | Methyl benzoate, Eugenol | Shikimate pathway | Floral scent, pollinator specificity, antimicrobial defense | Similar structures with different functions, complex regulation |

| Nitrogen-containing compounds | 2-Acetyl-1-pyrroline (2-AP) | Proline metabolism | Aroma in fragrant rice, defense compounds | Low abundance, analytical interference |

Experimental Protocol for VOC Monitoring Using Wearable Sensors

Materials and Equipment:

- Flexible chemiresistive sensor array (graphene-based or polymer composite)

- Wireless data acquisition system with signal conditioning circuitry

- Reference sensors for temperature, humidity, and light intensity

- Calibration sources with known VOC concentrations

- Data processing unit with machine learning algorithms for pattern recognition

Procedure:

- Sensor Calibration: Prior to deployment, calibrate the VOC sensor array using standard gas mixtures containing known concentrations of target compounds (e.g., terpenes, green leaf volatiles) at varying humidity and temperature levels to establish baseline responses and cross-sensitivity profiles.

Plant Attachment: Gently attach the flexible sensor to the abaxial surface of mature leaves using biocompatible adhesive, ensuring good contact without restricting natural leaf movements or damaging epidermal structures. For stem attachments, use flexible mounting straps that accommodate growth.

Signal Acquisition: Initiate continuous monitoring with sampling frequencies appropriate for the expected VOC emission dynamics (typically 0.1-1 Hz). Simultaneously record microclimate data from reference sensors to enable environmental compensation during data analysis.

Data Processing: Apply machine learning algorithms (e.g., principal component analysis, support vector machines) to the multivariate sensor data to identify distinctive VOC fingerprints associated with specific stress conditions or physiological states.

Validation: Correlate sensor readings with established analytical techniques such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) through periodic sampling to verify detection accuracy and identify potential interference issues.

Sap Flow Dynamics: Tracing the Plant's Circulatory System

Physiological Significance of Sap Flow

Sap flow represents the movement of water and dissolved nutrients through the xylem tissue of plants, serving as the fundamental circulatory system that connects roots to leaves. This physiological process is critically important for understanding plant water relations, as it directly reflects transpiration rates and water usage efficiency [11] [14]. In agricultural research, monitoring sap flow provides valuable insights into plant health, growth status, water consumption patterns, and nutrient distribution throughout the plant vascular system [14]. The ability to track these dynamics in real-time offers researchers a powerful window into how plants respond to environmental conditions, manage water resources, and allocate nutrients to different organs.

The significance of sap flow monitoring extends beyond basic physiological research to practical agricultural applications. With water scarcity becoming an increasingly pressing issue in many agricultural regions, understanding crop water use patterns through sap flow measurements can inform precision irrigation strategies that optimize water application while maintaining crop productivity [19]. Additionally, sap flow signatures can serve as early indicators of stress responses to drought, salinity, or root pathogens, often manifesting in altered diurnal patterns before visible symptoms appear [14] [19]. The development of wearable sap flow sensors has revolutionized this field by enabling continuous, non-destructive monitoring on individual plants, moving beyond the limitations of traditional destructive sampling methods that provided only snapshot measurements [14].

Thermal-Based Sap Flow Sensing Technologies

Most wearable sap flow sensors operate on thermal principle methods, which detect the movement of sap by measuring heat transport through the stem. The underlying physical principle involves creating a localized heat pulse and monitoring how flowing sap redistributes this heat, creating measurable temperature asymmetries that correlate with flow velocity [14]. One innovative implementation of this principle involves a flexible sensor design with a positive temperature coefficient (PTC) thermistor positioned between two temperature sensors aligned with the flow direction [14]. When activated, the thermistor creates a localized temperature increase, and the flowing sap creates an asymmetric temperature profile that is detected by the upstream and downstream sensors.

The technological advancement in this field has been the development of flexible, biocompatible form factors that can conform to plant stems without restricting growth or causing tissue damage. These sensors feature ultrathin, soft, stretchable, and lightweight designs that comfortably attach to various plant surfaces while maintaining excellent physical stability and environmental resistance [14]. Recent innovations include special designs that are air/water/light-permeable, addressing the critical need to minimize interference with normal plant functions at the biointerface [14]. Furthermore, the integration of wireless communication units enables remote control and real-time data acquisition, facilitating deployment across multiple plants in field conditions [14] [19].

Table: Comparison of Wearable Sap Flow Sensing Technologies

| Technology Type | Measurement Principle | Accuracy Range | Plant Compatibility | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Dissipation | Continuous heating and temperature measurement | ±10% for medium to high flows | Woody stems >10mm diameter | Moderate (requires thermal shielding) |

| Heat Pulse Velocity | Periodic heat pulses and time-of-flight measurement | ±5% with proper calibration | Herbaceous and woody plants | High (precise timing control needed) |

| Heat Balance | Comprehensive energy balance around stem | ±3% with full compensation | Small stems <12mm diameter | High (multiple compensation sensors) |

| Thermal Anisotropy | Spatial temperature asymmetry from constant heating | ±7-10% depending on flow rate | Various stem types and sizes | Low to Moderate (simpler design) |

Experimental Protocol for Sap Flow Monitoring

Materials and Equipment:

- Flexible sap flow sensor with PTC thermistor and temperature sensors

- Wireless data acquisition system with power management

- Calibration setup with controlled flow rates through stem segments

- Microclimate sensors (air temperature, humidity, photosynthetically active radiation)

- Data processing software with sap flow calculation algorithms

Procedure:

- Sensor Selection and Calibration: Select an appropriately sized sensor for the target plant stem diameter. Calibrate the sensor using a controlled flow system with excised stem segments of similar diameter to establish the relationship between temperature differential (ΔT) and sap flow rate.

Field Installation: Mount the sensor on a representative stem section with smooth bark, ensuring good thermal contact while avoiding damage to the phloem. Use the provided flexible mounting system that accommodates stem growth without constriction. For the EXO-Skin sensor, follow manufacturer guidelines regarding installation temperature (15-35°C) to prevent damage to the flexible components [20].

Power Management: Configure the heating element power according to stem diameter and expected flow rates. Refer to manufacturer specifications for appropriate voltage settings (typically 4.0-4.5 V DC) and power levels (0.15-0.48 W depending on sensor size) [20].

Data Collection: Initiate continuous monitoring with the thermistor operating in pulsed mode to minimize power consumption while maintaining measurement accuracy. Record temperature differentials between upstream and downstream sensors at 1-5 minute intervals depending on the temporal resolution required.

Data Processing: Calculate sap flow velocity using the appropriate model for the sensor type (e.g., thermal anisotropy, heat balance). Apply necessary corrections for environmental conditions and stem growth where applicable.

Validation: Periodically validate sensor readings against independent measurements such as potometer readings, stem heat balance methods, or lysimeter data when available.

Microclimate Monitoring: The Plant's Immediate Environment

Significance of Microclimate Parameters

The microclimate surrounding a plant encompasses the unique environmental conditions—including temperature, humidity, radiation, and wind—to which vegetation is directly exposed [11]. These factors fundamentally influence essential plant processes such as photosynthesis, transpiration, respiration, and translocation, ultimately determining plant productivity and health [11]. Additionally, microclimate conditions play a crucial role in regulating external threats to plant growth, including pest infestations and disease development [11]. The ability to monitor these parameters directly at the plant-air interface provides valuable context for interpreting physiological measurements such as sap flow and VOC emissions, enabling researchers to distinguish between endogenous rhythms and environmentally driven responses.

The importance of microclimate monitoring stems from the substantial differences that can exist between conditions measured at standard weather stations and the actual environment experienced by individual plants. Canopy microclimates differ significantly from open-field conditions due to the modifying effects of plant structure on air movement, light penetration, and humidity retention [11]. These fine-scale environmental variations can dramatically affect plant physiology and pathogen dynamics, making field-level weather data insufficient for precise physiological studies. Wearable microclimate sensors address this limitation by providing direct measurements of the conditions immediately surrounding the plant organs being studied, enabling more accurate correlations between environmental cues and plant responses [11] [15].

Wearable Microclimate Sensing Technologies

Wearable sensors for microclimate monitoring leverage advances in flexible electronics and miniaturized sensing elements to create multifunctional platforms that can be directly attached to plant surfaces. These sensors typically incorporate capabilities for measuring temperature, humidity, light intensity, and sometimes additional parameters such as wind speed or precipitation [7] [15]. The technological challenges in this domain include creating sensors that are sufficiently small and lightweight to avoid interfering with normal plant functions, while maintaining protection from environmental damage from rain, UV radiation, and mechanical abrasion.

Recent innovations in materials science have enabled the development of permeable sensor designs that allow the necessary exchange of gases and water vapor while protecting the active electronic components [14]. For example, researchers have created graphene-based humidity sensors that can be directly laminated onto leaf surfaces to monitor transpiration rates and ambient humidity simultaneously [15]. Similarly, flexible temperature sensors based on platinum or graphene inks provide precise measurements of leaf surface temperature, which is a valuable indicator of plant water status and stomatal conductance [15]. The integration of these diverse sensing capabilities into unified platforms allows researchers to obtain comprehensive microclimate profiles alongside physiological measurements, creating multidimensional datasets for advanced analysis.

Integrated Sensing Platforms and Data Analysis

The Multisensor Approach

While individual sensors provide valuable data on specific physiological parameters, the full potential of wearable plant sensors emerges when they are integrated into multisensory platforms that enable comprehensive monitoring of plant status and environmental conditions [11]. These integrated systems combine physical, chemical, and electrophysiological sensors on a single flexible substrate, allowing researchers to capture complementary datasets that reveal interactions between different physiological processes [7]. For instance, combining sap flow sensors with microclimate monitors enables the distinction between environmentally driven transpiration patterns and those resulting from internal plant factors such as hydraulic limitations or root signals.

The technological foundation for these integrated platforms rests on advances in flexible hybrid electronics, which combine conventional silicon-based chips with solution-processable electronic components on stretchable substrates [15] [14]. Serpentine metal traces, embedded in thin polymer matrices such as polyimide or polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), provide electrical connectivity while accommodating mechanical deformation from plant growth [14]. These manufacturing approaches enable the creation of complex, multifunctional sensing systems that maintain flexibility, durability, and biocompatibility—essential characteristics for long-term plant monitoring applications. Recent demonstrations include systems that simultaneously monitor stem diameter variations, sap flow, surface temperature, and ambient humidity, providing multidimensional insights into plant water relations [15].

Artificial Intelligence and Data Analysis

The continuous, high-resolution data streams generated by wearable plant sensors create both opportunities and challenges for data analysis. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) techniques are increasingly being applied to extract meaningful patterns from these complex datasets, identifying subtle correlations that might escape conventional statistical methods [11]. For example, neural network algorithms can learn to recognize characteristic VOC signatures associated with specific pathogen infections or nutrient deficiencies, enabling early diagnosis before visible symptoms appear [11]. Similarly, anomaly detection algorithms can identify unusual sap flow patterns that indicate the onset of water stress or vascular dysfunction.

The application of AI in plant wearable sensor technology remains underutilized, representing a significant opportunity for future research [11]. Potential applications include the development of predictive models that forecast plant responses to environmental changes based on real-time sensor data, enabling proactive management interventions. Additionally, data fusion techniques can integrate information from multiple sensor types to create more robust indicators of plant health than any single parameter could provide. As these analytical capabilities mature, they will enhance the value of wearable sensor networks as decision-support tools for precision agriculture and basic plant research.

Data Analysis Workflow for Plant Wearable Sensors

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Plant Wearable Sensor Applications

| Category | Specific Items | Technical Specifications | Primary Applications | Supplier Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible Substrates | Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), Polyimide (PI) | Thickness: 1-20 µm, Elastic modulus: <1 MPa, Permeability: Air/water/light permeable | Sensor foundation, plant interface, environmental protection | Specialty polymer suppliers |

| Conductive Materials | Graphene inks, Carbon nanotube composites, Gallium-based liquid alloys | Sheet resistance: 10-1000 Ω/sq, Stretchability: up to 200% | Sensing elements, electrical interconnects | Nanomaterial specialists |

| Sensing Elements | PTC thermistors, Platinum temperature sensors, Metal oxide semiconductors | Temperature coefficient: +0.5-4%/°C, Response time: <10s | Sap flow sensing, microclimate monitoring, VOC detection | Electronic components suppliers |

| Data Acquisition | Wireless modules (LoRa, NB-IoT), Flexible printed circuit boards (FPCB) | Transmission range: 100m-10km, Power consumption: <1W, Sample rate: 0.1-10 Hz | Remote data collection, sensor control, power management | IoT and electronics suppliers |

| Calibration Standards | VOC mixtures, Flow rate controllers, Certified reference materials | Concentration accuracy: ±5%, Flow accuracy: ±1% full scale | Sensor calibration, measurement validation | Scientific calibration suppliers |

| Mounting Solutions | Biocompatible adhesives, Flexible straps, Encapsulation materials | Adhesion strength: 0.1-1 N/cm, Water resistance: IP67 | Sensor attachment, environmental protection | Specialized adhesives manufacturers |

Plant wearable sensor technology represents a cutting-edge field that is still in its initial stages of development but holds tremendous promise for advancing plant research and precision agriculture. The ability to monitor physiological parameters such as VOC emissions, sap flow dynamics, and microclimate conditions in real-time provides researchers with unprecedented insights into plant function and stress responses [11]. These continuous, high-resolution data streams enable the development of more sophisticated plant models and the identification of early warning signatures for stress conditions, potentially revolutionizing how we monitor and manage crops in both controlled and field environments.

Looking forward, several research directions appear particularly promising for advancing plant wearable sensor technology. There is a clear need to improve the applicability of these sensors across plants with diverse morphologies, as most current implementations have been demonstrated on a limited range of species, primarily woody plants with sturdy stems [11]. Additionally, the integration of multisensory platforms for more comprehensive monitoring represents an important frontier, as does the fuller utilization of artificial intelligence in data analysis [11]. As these technological advancements mature, plant wearable sensors are poised to become an indispensable tool in the researcher's arsenal, contributing to more sustainable agricultural practices and enhanced food security in the face of global environmental challenges.

In precision agriculture research, the direct, in vivo monitoring of plant physiology is paramount for understanding crop stress responses and optimizing productivity. Wearable plant sensors represent a transformative technological approach, enabling continuous, real-time measurement of key biophysical and biochemical parameters without causing significant harm to the plant [1]. These sensors provide a dynamic window into plant health, moving beyond traditional destructive sampling and discrete data points. This guide details the core measurable parameters—strain, temperature, ions, and action potentials—that are critical for decoding plant signaling and stress responses, with a focus on the operational principles of the sensors that detect them.

Measurable Parameters and Quantitative Ranges

The following tables summarize the key ions and physical parameters that can be monitored using wearable sensor technology, providing reference ranges for interpreting the collected data.

Table 1: Key Ionic Macronutrients Monitorable with Wearable Sensors

| Ion | Importance | Key Plant Organs | Role in the Plant | Typical Concentration Ranges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K+ | High | Stem, Leaves, Root | Osmotic regulation, enzyme activation, photosynthesis, maintains cell turgor | 1 - 150 mM [21] |

| N (NO₃⁻, NH₄⁺) | High | Leaves, Root | Major component of chlorophyll, essential for photosynthesis, enhances root growth | 5 - 50 mM [21] |

| P (H₂PO₄⁻, HPO₄²⁻) | High | Stem, Root | Energy transfer (ATP), signaling pathways, affects root elongation | 1 - 15 mM [21] |

| Ca²⁺ | High | Leaves, Root | Structural component of cell walls, signaling, supports root tip growth | 2 - 10 mM [21] |

| Mg²⁺ | Medium | Leaves, Root | Central atom in chlorophyll; enzyme cofactor, enhances root nutrient uptake | 0.5 - 3 mM [21] |

Table 2: Key Ionic Micronutrients Monitorable with Wearable Sensors

| Ion | Importance | Key Plant Organs | Role in the Plant | Typical Concentration Ranges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ | High | Leaves, Root | Essential for chlorophyll synthesis and electron transport, critical for root respiration | 10 - 100 µM [21] |

| Zn²⁺ | Medium | Leaves, Root | Activates enzymes, regulates photosynthesis, promotes root elongation | 5 - 50 µM [21] |

| Mn²⁺ | Medium | Leaves, Root | Involved in water splitting during photosynthesis, essential for root structure | 10 - 200 µM [21] |

| Cu²⁺ | Low | Leaves, Root | Cofactor in electron transport and oxidative stress enzymes | 2 - 20 µM [21] |

| Cl⁻ | Medium | Leaves, Roots | Essential for photosynthesis (water-splitting reaction), aids in charge balance | 0.05 - 0.5 mM [21] |

Table 3: Other Key Measurable Parameters

| Parameter | Sensor Type | Significance in Plant Physiology | Typical Measurement Range / Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Action Potential | Electrophysiological Sensor [22] | Rapid long-distance signaling in response to touch, wounding, or other stimuli; mediates rapid movements (e.g., Venus flytrap closure) | Amplitude: 10 - 150 mV; Duration: 1 - 3 s; Propagation Speed: ~10 - 80 cm/s [22] |

| Strain / Mechanical Stress | Distributed Strain Sensing (DTSS) [23] | Monitors mechanical deformation; indicates growth, physical stress, or structural integrity of stems and leaves. | Measured as deformation along a fiber optic cable; provides a continuous profile for asset monitoring [23] |

| Temperature | Distributed Temperature Sensing (DTS) [24] [23] | Regulates growth, development, and serves as a seasonal cue (e.g., vernalization). High temperatures can induce thermotolerance responses. | Varies with environment; critical for processes like hypocotyl elongation and leaf shape modification [24] |

Sensor Technologies and Operating Principles

Microneedle Sensors for In-Planta Ion Monitoring

Microneedle (MN) sensors are a minimally invasive technology designed to penetrate the plant epidermis and access the apoplastic fluid or sap directly, overcoming the limitations of surface-mounted sensors [21]. These sensors are typically configured as potentiometric Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs).

Experimental Protocol for In-Vivo Potassium (K+) Monitoring [25]:

- Fabrication: A microneedle is coated with a conductive polymer or a solid-contact layer like electrodeposited Manganese Dioxide (MnO₂). This is then coated with a ion-selective membrane (ISM) containing a K+ ionophore (e.g., Valinomycin), a plasticizer (e.g., o-Nitrophenyl octyl ether, o-NPOE), and a polymer matrix (e.g., Polyvinyl chloride, PVC).

- Reference Electrode: A separate microneedle is prepared with an Ag/AgCl layer and coated with a reference membrane containing a fixed concentration of NaCl in a polymer like Polyvinyl butyral (PVB) to maintain a stable reference potential [25].

- Calibration: The sensor pair is calibrated in standard K+ solutions to establish a Nernstian response, typically -59.5 mV per decade change in K+ concentration [25].

- In-Vivo Measurement: The two microneedles are carefully inserted into the plant tissue (e.g., stem or leaf). The open-circuit potential between the K+-ISE and the reference electrode is measured continuously.

- Data Analysis: The recorded potential is converted to K+ concentration using the established calibration curve. Time-series prediction models, such as a Nonlinear Autoregressive Neural Network (NARNN), can be applied to the data stream to analyze dynamic patterns and predict trends from transient ion signals [25].

Multielectrode Arrays for Action Potential Propagation

Action Potentials (APs) in plants are rapid, transient changes in the membrane potential of excitable cells. In species like the Venus flytrap, they are responsible for rapid movements and are correlated with responses to stress [22] [26]. Conformable Multielectrode Arrays (MEAs) based on organic electronics enable high-resolution spatiotemporal mapping of these signals.

Experimental Protocol for AP Mapping in Venus Flytrap [22]:

- Electrode Preparation: A flexible, conformable MEA with numerous (e.g., 120) microelectrodes made of a conducting polymer (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) is fabricated. The conformability ensures intimate contact with the plant's curved surface without slipping.

- Interface: The MEA is laminated onto the outer surface of a Venus flytrap lobe. A small amount of electrolyte gel is used to ensure a good electrical connection between the plant tissue and each electrode.

- Stimulation & Recording: A trigger hair is mechanically stimulated with a calibrated touch. The MEA simultaneously records the electrical potential from all electrode sites at a high sampling rate.

- Data Analysis: The precise time of arrival of the AP waveform at each electrode is determined. A propagation map is generated by plotting these time delays against the spatial coordinates of the electrodes, allowing for the calculation of propagation speed and directionality. Phase shift analysis can confirm active propagation versus passive volume conduction [22].

Distributed Fiber Optic Sensing for Strain and Temperature

Distributed Temperature and Strain Sensing (DTSS) systems use standard optical fibers as continuous, linear sensors to monitor the thermal and mechanical state of plants or their supporting structures over long distances [23].

Experimental Protocol for Strain and Temperature Monitoring [23]:

- Cable Installation: An optical fiber cable is attached directly to a plant structure (e.g., a main stem or branch) to measure strain, or installed in the plant's microclimate to monitor temperature.

- Laser Pulse Emission: The DTSS interrogator unit launches short, coherent laser pulses into the optical fiber.

- Brillouin Scattering: As the pulse travels, it interacts with the fiber material, generating a weak backscattered light signal. The properties of this Brillouin backscatter (its frequency shift and amplitude) are influenced by both the temperature and the mechanical strain applied to the fiber at every point.

- Signal Analysis: The backscattered light is analyzed. The time delay of the returning signal pinpoints the location of the event (Optical Time-Domain Reflectometry). The frequency shift and amplitude are decoded to separately quantify the temperature and strain. This separation can be achieved by using a dedicated, strain-free reference fiber for temperature or through processing techniques that decouple the two effects from the combined signal [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Fabricating Wearable Plant Sensors

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ionophores | Sensing element in ion-selective membranes; confers selectivity to target ions. | Valinomycin (for K+), Chloride ionophore I (for Cl⁻) [27] [25] |

| Polymer Matrices | Forms the bulk of the sensing and reference membranes; holds ionophore and other components. | Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC), Poly(vinyl butyral) (PVB) [27] [25] |

| Plasticizers | Imparts flexibility and mobility to the ion-selective membrane; influences sensor performance and lifespan. | o-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE) [27] [25] |

| Solid Contact Materials | Provides a stable ion-to-electron transduction layer in all-solid-state ISEs; improves potential stability. | Manganese Dioxide (MnO₂), Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) [25] |

| Conductive Inks/Polymers | Forms electrodes and conductive traces for flexible and printed sensors. | PEDOT:PSS, Carbon ink, Silver/AgCl ink [27] [22] |

| Biodegradable Substrates | Eco-friendly support material for sustainable sensor fabrication; reduces environmental impact. | Polylactic acid (PLA), Cellulose derivatives, Starch-based polymers [1] |

| Electrolyte Gel | Ensures stable electrical interface between plant tissue and recording electrode for electrophysiology. | Standard Ag/AgCl electrode gel [28] [22] |

The integration of wearable sensor technologies for monitoring ions, action potentials, strain, and temperature provides an unprecedented, multidimensional view of plant physiology. From the minimally invasive probing of sap chemistry with microneedles to the large-scale mapping of electrical signals with conformable electronics, these tools are decoding the complex language of plant stress and signaling. The data generated are pivotal for building predictive models and developing actionable insights in precision agriculture. As these sensors evolve, particularly toward the use of sustainable and biodegradable materials [1], they will become integral to a future of highly efficient, data-driven, and environmentally conscious crop management.

The Critical Role in Addressing Global Food Security and Sustainable Practices

The global agricultural sector faces unprecedented challenges; the population is estimated to reach 9.8 billion by 2050, requiring a 70% increase in food production [29]. Concurrently, crop vulnerability is exacerbated by climate change, with approximately 40% of global crop productivity lost annually to plant diseases and environmental stressors [1]. In this context, precision agriculture has emerged as a critical discipline, leveraging data-driven insights to optimize resource use, enhance yields, and promote sustainability. Wearable plant sensors represent a revolutionary tool within this paradigm, enabling real-time, non-invasive monitoring of plant physiological status. Recognized by the World Economic Forum as a Top 10 Emerging Technology in 2023 [1], these sensors provide a continuous stream of high-resolution data, shifting agricultural management from reactive to proactive interventions. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of wearable plant sensor technologies, their operational mechanisms, and their transformative potential in securing a sustainable food future.

Technical Foundations of Wearable Plant Sensors

Wearable plant sensors are miniaturized, flexible analytical devices directly attached to plant organs—such as stems, leaves, and fruits—for continuous, in-situ monitoring of health indicators [6] [1]. Their fundamental design overcomes the limitations of traditional rigid sensors, which can cause biological rejection and damage to plant tissues during long-term contact [30].

Core Components and Architecture

The architecture of a typical wearable plant sensor consists of a multi-layer sandwich structure [6]:

- Flexible Substrate: This base layer provides mechanical support and conformability. Advanced devices use sustainable, biodegradable materials like polylactic acid (PLA), starch, and cellulose derivatives to reduce environmental impact [1].

- Sensing Element/Electrode: This active layer interacts with the plant and transduces biological or physical signals into measurable electrical signals. Materials range from conductive textiles [31] to nanomaterials like carbonized silk georgette [32] and functionalized graphene [6].

- Encapsulation Material: A top protective layer that shields the sensing element from harsh environmental conditions (e.g., moisture, UV radiation) while maintaining flexibility, often using polymers like PDMS or Ecoflex [6] [31].

Sensing Mechanisms and Signal Transduction

These sensors operate on various transduction principles, converting plant signals into quantifiable electrical data. Table 1 summarizes the primary sensor types, their targets, and their underlying working principles.

Table 1: Classification of Wearable Plant Sensors by Sensing Mechanism

| Sensor Category | Measured Parameters | Sensing Mechanism | Example Sensing Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Sensors [7] [3] | Strain (growth), temperature, humidity, light | Measures changes in electrical resistance [31], capacitance [31], or triboelectrification [6] in response to physical stimuli. | Conductive textiles [31], graphite ink [6], ZnIn2S4 nanosheets [6] |

| Chemical Sensors [7] [3] | Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), ions, pesticide residues, pH | Detects chemical interactions that alter the electrical properties (e.g., resistance) of a functionalized sensing layer [6]. | Functionalized reduced graphene oxide (rGO) [6], MXenes [6] |

| Electrophysiological Sensors [7] [3] | Action potentials, variation potentials | Measures minute electrical potentials generated by plants using electrophysiological electrodes. | Gold metal film [6], conductive polymers |

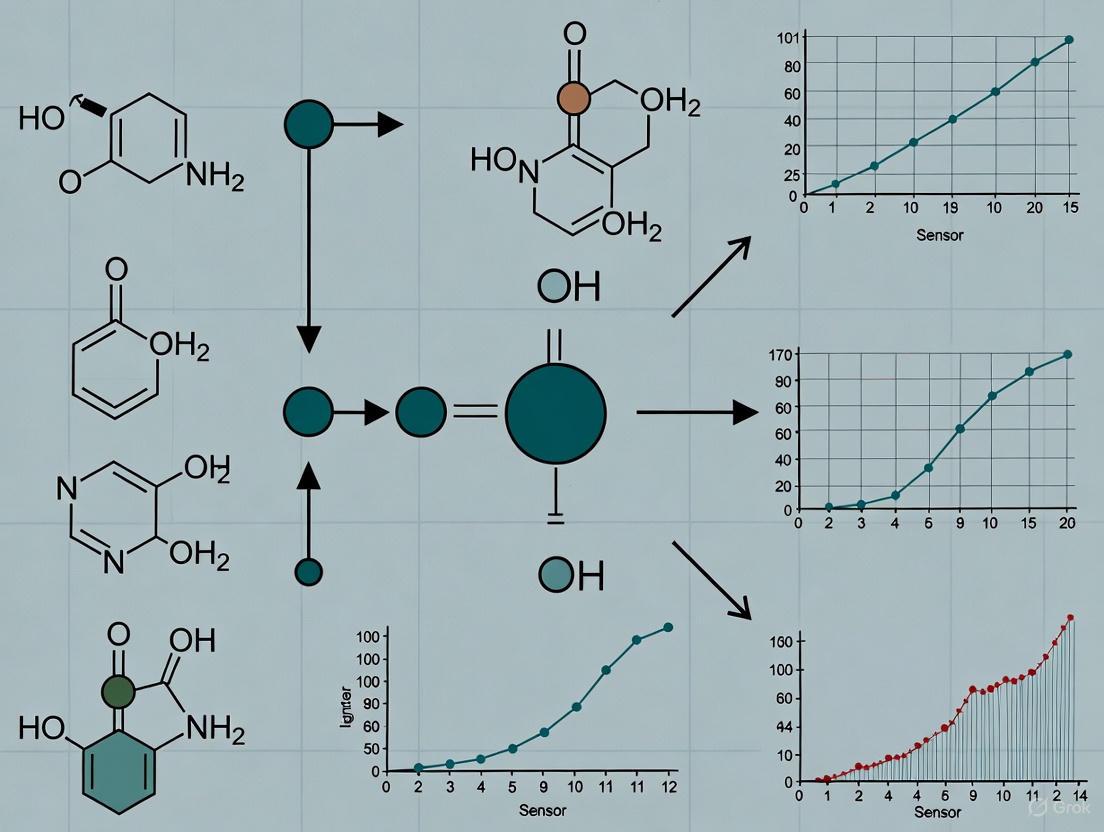

Figure 1: A taxonomy of wearable plant sensor categories and their primary measurement targets, based on synthesis from multiple research reviews [7] [3] [33].

Advanced Sensor Systems and Performance Metrics

Recent technological advances have moved beyond single-parameter sensing to integrated, multi-functional platforms. These systems provide a holistic view of plant health by simultaneously monitoring various physiological and environmental parameters.

Representative High-Throughput System: PlantRing

The PlantRing system exemplifies innovation in high-throughput phenotyping. It employs bio-sourced carbonized silk georgette as its strain-sensing material, offering an exceptional detection limit of 0.03%–0.17% strain, high stretchability (up to 100% tensile strain), and remarkable durability for season-long use [32]. This system deciphers plant growth and water relations by measuring organ circumference dynamics with high precision. Its application has enabled:

- Large-scale quantification of stomatal sensitivity to soil drought, facilitating the selection of drought-tolerant germplasm [32].

- Discovery of a novel function for the circadian clock gene GmLNK2 in stomatal regulation [32].

- Feedback irrigation systems that achieve simultaneous water conservation and quality improvement [32].

Multi-Sensor Platform: Plant-Wear

Another approach, the Plant-Wear platform, uses custom flexible strain sensors fabricated from a conductive textile for monitoring stem and fruit growth, alongside a commercial environmental sensor (BME280) for tracking ambient temperature and relative humidity [31]. This system addresses key engineering challenges:

- Organ-Specific Design: A dumbbell-shaped sensor for stems and a ring-shaped sensor for fruits [31].

- Environmental Compensation: A reference sensor is placed on a rigid bar to compensate for temperature and humidity effects on the active sensor's output [31].

- Robust Encapsulation: A three-layer silicone (Ecoflex 00-30) structure protects the fruit sensor from environmental exposure in field conditions [31].

Table 2 quantifies the performance characteristics of various sensor types as reported in recent literature.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Selected Wearable Plant Sensors

| Sensor Focus / Name | Sensing Material | Key Performance Metrics | Stability / Durability | Application Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PlantRing (Growth) [32] | Carbonized silk georgette | Detection limit: 0.03%-0.17% strain; Stretchability: up to 100% | Season-long use | Tomato & watermelon fruit cracking; stomatal sensitivity |

| Stem Growth Sensor [31] | Conductive textile (Eeontex) | Measured stem elongation via resistance change | Test duration: Laboratory setting | Tobacco stem growth |

| Fruit Growth Sensor [31] | Conductive textile + Ecoflex encapsulation | Measured fruit expansion via resistance change | Test duration: Open field setting | Melon fruit growth |

| VOC Monitoring [6] | Functionalized rGO | Real-time profiling of volatile organic compounds | - | Early stress and disease detection |

| Microclimate [6] | GO on PI substrate | Sensitivity: 7945 Ω/% RH | 21 days | Plant water status |

Figure 2: System architecture of a multi-sensor wearable platform for plants, illustrating the integration of different sensor types, signal conditioning, and data communication pathways, as demonstrated in systems like Plant-Wear [31].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

For researchers aiming to implement or validate wearable plant sensor technologies, detailed methodologies are crucial. The following protocols are synthesized from high-impact studies.

Protocol 1: Deployment of a Multi-Sensor Growth Monitoring Platform

This protocol outlines the setup for simultaneous monitoring of stem/fruit growth and microclimate, adapted from established platforms [31].

1. Sensor Fabrication and Preparation:

- Stem/Fruit Sensor Fabrication: Cut the sensing element from a conductive textile sheet (e.g., Eeontex LG-SLPA) into a dumbbell shape (e.g., 60mm x 10mm for stems) or a ring shape for fruits. Sew conductive silver-plated threads at the ends for electrical connection [31].

- Fruit Sensor Encapsulation: For field durability, encapsulate the fruit sensor in a three-layer structure using multiple castings of a silicone polymer (e.g., Ecoflex 00-30) within a 3D-printed PLA mold [31].

- Reference Sensor Preparation: Prepare a nominally identical sensor mounted on a rigid, non-expanding substrate (e.g., plastic bar) to compensate for ambient temperature and humidity variations [31].

2. Data Acquisition System Setup:

- Signal Transduction: Connect the active and reference sensors to separate Wheatstone bridges in a 1/4 bridge configuration.

- Signal Amplification and Digitization: Route the output of each bridge to an instrumentation amplifier (e.g., AD8426) and then to a digitizer (e.g., M5 Stick-C Plus commercial board) [31].

- Microclimate Sensing: Connect a commercial environmental sensor (e.g., BME280) to the same digitizer via an I²C bus to log ambient temperature and relative humidity [31].

3. Data Collection and Wireless Transmission:

- Configure the main controller (e.g., M5 Stick-C Plus) to wirelessly transmit digitized data from all channels (active sensor, reference sensor, environment) via Wi-Fi to a local data logger (e.g., Raspberry Pi 4) [31].

4. Data Processing and Analysis:

- Data Synchronization: Align all data streams (active strain, reference, T, RH) using timestamps.

- Strain Calculation: Convert the calibrated resistance change of the active sensor (compensated using the reference sensor signal) into a physical strain value.

- Growth Analysis: Correlate the temporal strain data with microclimate data to interpret plant growth dynamics and water relations.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Phenotyping for Stomatal Sensitivity

This protocol leverages a high-precision system like PlantRing for large-scale physiological genetics studies [32].

1. Sensor Calibration and Deployment:

- Calibrate PlantRing sensors or equivalent against known standards to define the strain-resistance relationship.

- Mount the sensors securely on the stems or fruits of a large population of plants (e.g., different genotypes or treatments).

2. Induction of Soil Drought:

- Withhold irrigation gradually to impose controlled soil water deficit across the plant population.

3. Continuous Data Acquisition:

- Log organ circumference dynamics continuously at high temporal resolution (e.g., minute-scale) throughout the drought period and subsequent recovery after re-watering.

4. Data Analysis and Trait Extraction:

- Stomatal Sensitivity Quantification: Analyze the data to extract key physiological traits, such as the threshold of soil water potential at which stomatal closure initiates, and the rate of circumference contraction.

- Genotype-Phenotype Association: Use the large-scale, high-throughput phenotypic data (e.g., stomatal sensitivity scores) for genome-wide association studies (GWAS) or screening of mutant libraries to identify genes involved in drought tolerance [32].

The Research Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Successful development and deployment of wearable plant sensors require a suite of specialized materials and electronic components. The following table details key items and their functions based on cited research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Wearable Plant Sensor Development

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function / Application | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible Substrates & Encapsulants | Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), Ecoflex 00-30 | Provides flexible, stretchable, and often waterproof encapsulation for sensors; ensures biocompatibility and protection. | [6] [31] |

| Conductive Sensing Materials | Conductive textile (Eeontex), Carbonized silk georgette, Graphite ink, Functionalized rGO | Forms the core sensing element; changes electrical properties (resistance/capacitance) in response to strain, VOCs, or other stimuli. | [32] [6] [31] |

| Fabrication Tools | 3D Printer (for molds), Screen printer, Inkjet printer | Enables rapid prototyping and custom patterning of sensors and support structures. | [31] [1] |

| Signal Conditioning Electronics | Wheatstone bridge board, Instrumentation amplifier (e.g., AD8426) | Converts small changes in sensor resistance into a measurable voltage signal; amplifies weak signals. | [31] |

| Data Acquisition & Control | M5 Stick-C Plus, Raspberry Pi 4, Microcontroller with ADC | Digitizes analog signals, provides processing power, and manages wireless data transmission. | [31] |

| Environmental Sensing | BME280 Integrated Circuit | Simultaneously measures ambient temperature, relative humidity, and pressure for microclimate monitoring and data compensation. | [31] |

Challenges and Future Research Directions

Despite significant progress, several technical and practical hurdles must be overcome to realize the full potential of wearable plant sensors.

Persistent Challenges

- Long-Term Stability and Robustness: Sensors must endure harsh and unpredictable agricultural environments, including extreme temperatures, UV radiation, rain, and physical abrasion. Issues such as signal drift, material degradation, and loosening adhesion remain significant concerns [30] [29].

- Biocompatibility and Plant Health Impact: Long-term effects of sensor attachment on plant physiology, such as impeded gas exchange, restricted growth, or causing micro-lesions, require thorough investigation [3] [30].

- Power Supply and Energy Harvesting: Continuous operation demands sustainable power solutions. The development of integrated energy harvesting systems (e.g., solar, biomechanical) is critical for large-scale, long-term deployments [30].

- Data Management and Standardization: The vast amount of data generated by sensor networks necessitates robust, scalable data management architectures, standardized data formats, and advanced analytics powered by AI and machine learning [1] [29].

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

- Sustainable and Biodegradable Sensors: A major research focus is on developing eco-friendly sensors using substrates and materials that are biodegradable (e.g., PLA, cellulose-based polymers) to minimize electronic waste and environmental impact [1].

- Advanced Manufacturing and Nanomaterials: Techniques like 3D printing and roll-to-roll processing, combined with novel nanomaterials, promise low-cost, scalable production of high-performance, multifunctional sensors [1] [29].

- Integration with IoT and AI: The fusion of wearable sensor networks with the Internet of Things (IoT) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) is paving the way for fully autonomous, closed-loop agricultural systems that can self-diagnose and self-optimize in real-time [1] [29].

- Market Growth and Adoption: The wearable plant sensor market is projected to experience robust growth, driven by the pressing need for food security and sustainable practices. This economic momentum will likely accelerate technological innovation and adoption [34] [29].

Wearable plant sensors are poised to fundamentally transform precision agriculture research and practice. By providing non-invasive, continuous, and real-time insights into plant physiology, these devices empower a shift from traditional, calendar-based farming to a data-driven, responsive paradigm. They are instrumental in addressing grand challenges such as optimizing water and nutrient use, developing climate-resilient crops, and reducing environmental footprints. While challenges in durability, scalability, and biocompatibility persist, ongoing research in sustainable materials, nanotechnology, and data analytics is rapidly advancing the field. The widespread integration of this technology holds the key to building a more productive, efficient, and sustainable global agricultural system, ensuring food security for future generations.

Implementation and Advanced Applications in Real-World Agriculture

Precision agriculture is a data-driven paradigm that relies on timely and accurate information to address the escalating challenges of population growth, cultivated land reduction, and environmental degradation [3]. Around 700 million people worldwide still face food shortages, creating an urgent need for intelligent plant monitoring systems to ensure healthy crop growth [3]. Wearable plant sensors represent a technological frontier in this effort, enabling direct, in-situ monitoring of physiological processes by attaching directly to plant surfaces [3]. Unlike traditional monitoring methods that provide sporadic data, these flexible devices offer continuous, real-time assessment of plant health status under various stress conditions [3].

The core challenge in wearable plant sensor design lies in creating devices that can conform to complex plant morphologies while withstanding environmental exposures and accurately detecting subtle biological signals. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles of material selection and sensor design, focusing on three critical attributes: flexibility for conformal contact, biocompatibility to avoid plant tissue damage, and durability for reliable long-term monitoring. These interconnected properties form the foundation for effective sensor-plant interfaces that can transform agricultural practices through unprecedented access to plant physiological data.

Material Selection for Flexible Plant Sensors

Polymer Substrates and Matrix Materials

Polymer substrates form the structural backbone of flexible plant sensors, providing mechanical support while enabling conformal contact with irregular plant surfaces. These materials are selected based on their flexibility, optical properties, and environmental stability:

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS): This silicone-based polymer is favored for its exceptional flexibility, optical transparency, and biocompatibility [35]. Its low surface energy helps maintain sensor cleanliness in agricultural environments, though its inherent low electrical conductivity necessitates composite formation with conductive materials for sensing applications [35]. A notable application includes ZnO-PDMS nanocomposites for dental protectors that detect volatile sulfur compounds, demonstrating viability for plant volatile organic compound monitoring with cell viability rates exceeding 95% in biocompatibility tests [35].

Polyimide (PI): Valued for excellent thermal stability, insulation properties, and film-forming ability, PI maintains performance across varying environmental conditions [35]. This makes it suitable for sensors deployed in field conditions with fluctuating temperatures and humidity levels.