Harnessing Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria for Enhanced Hydroponic Root Zone Health and Crop Productivity

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) applications in hydroponic systems, targeting researchers and scientists in agricultural biotechnology and drug development.

Harnessing Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria for Enhanced Hydroponic Root Zone Health and Crop Productivity

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) applications in hydroponic systems, targeting researchers and scientists in agricultural biotechnology and drug development. It explores the foundational science of PGPR-plant interactions in soilless environments, details practical methodologies for successful hydroponic inoculation, addresses critical troubleshooting parameters for system optimization, and presents validation data comparing PGPR efficacy against conventional fertilization. The synthesis of recent research demonstrates PGPR's significant potential to reduce mineral fertilizer dependence by up to 80% while improving crop yield, nutritional quality, and stress resilience, offering sustainable solutions for controlled-environment agriculture with implications for pharmaceutical compound production through enhanced secondary metabolite accumulation.

The Science of PGPR in Hydroponic Root Zones: Mechanisms and Ecological Adaptations

Defining PGPR and Their Transition from Soil to Soilless Agriculture

Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) are beneficial soil bacteria that colonize plant roots and enhance plant growth through multiple direct and indirect mechanisms. While traditionally studied and applied in soil-based agriculture, their use is rapidly expanding into soilless cultivation systems. This transition represents a significant paradigm shift in managed plant growth environments, offering opportunities to enhance sustainable food production. This technical guide examines the core definitions of PGPR, their mechanisms of action, and the experimental approaches facilitating their successful integration into hydroponic, aeroponic, and aggregate-based soilless agriculture, providing researchers with comprehensive methodological frameworks for advancing this promising field.

Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) are defined as free-living, root-colonizing bacteria that exert beneficial effects on plant growth and development through diverse direct and indirect mechanisms [1] [2]. The term was first coined by Kloepper and Schroth (1981) to describe soil bacteria that colonize plant roots and enhance plant growth [2]. These bacteria form a component of the complex rhizosphere microbiome, the soil zone immediately surrounding plant roots that is influenced by root exudates [3] [2]. This environment exhibits bacterial populations 100–1000 times higher than bulk soil due to the abundance of organic compounds released by roots [2].

PGPR associations with plants range in proximity and intimacy. They are broadly categorized as iPGPR (symbiotic bacteria living inside plant cells, such as Rhizobia and Frankia within specialized nodules) and ePGPR (free-living rhizobacteria that inhabit the rhizosphere without forming intimate cellular structures) [2]. Functionally, PGPR are classified as biofertilizers (enhancing nutrient availability), phytostimulators (producing phytohormones), rhizoremediators (degrading pollutants), and biopesticides (controlling diseases through antibiotics) [2]. Common PGPR genera include Azospirillum, Azotobacter, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Enterobacter, and Paenibacillus, among others [4] [5] [6].

Core Mechanisms of PGPR Action

PGPR promote plant growth through multifaceted mechanisms operating simultaneously, categorized into direct and indirect modes of action.

Direct Mechanisms

Direct mechanisms involve providing plants with essential resources or directly stimulating physiological processes.

- Biofertilization: PGPR enhance nutrient availability through biological nitrogen fixation, converting atmospheric N₂ into plant-usable ammonia [1] [2]. They also solubilize otherwise inaccessible minerals through production of phosphate-solubilizing enzymes, organic acids, and siderophores, increasing phosphorus, potassium, zinc, and iron uptake [1] [4] [6].

- Phytohormone Production: PGPR synthesize and modulate plant hormones including auxins (e.g., indole-3-acetic acid, IAA), cytokinins, and gibberellins [7] [3] [2]. These hormones stimulate root and shoot development; IAA specifically promotes lateral root and root hair formation, expanding the root surface area for nutrient absorption [7] [3].

- Modification of Root System Architecture: Through phytohormone production and other signals, PGPR extensively modify root morphology. Typical responses include inhibited primary root growth, enhanced lateral root branching, and increased root hair development, collectively improving nutrient and water uptake efficiency [7] [3].

Indirect Mechanisms

Indirect mechanisms primarily involve plant protection against phytopathogens.

- Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR): PGPR prime plant immune defenses without causing direct harm. Upon root colonization, they trigger jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene (ET) dependent signaling pathways, enabling faster and stronger defense activation against subsequent pathogen attacks such as Botrytis cinerea [5]. Some strains also activate salicylic acid (SA)-dependent pathways [5].

- Antibiosis and Pathogen Antagonism: PGPR produce antimicrobial compounds including antibiotics, fungal cell wall-lysing enzymes (e.g., chitinase), and siderophores [1] [4] [5]. Siderophores are iron-chelating compounds that sequester environmental iron, creating competitive advantages over pathogenic microorganisms [1] [2].

- Stress Tolerance Enhancement: PGPR help plants withstand abiotic stresses including salinity, drought, and heavy metal contamination [1] [8]. They induce metabolic reprogramming that mitigates oxidative stress damage [8].

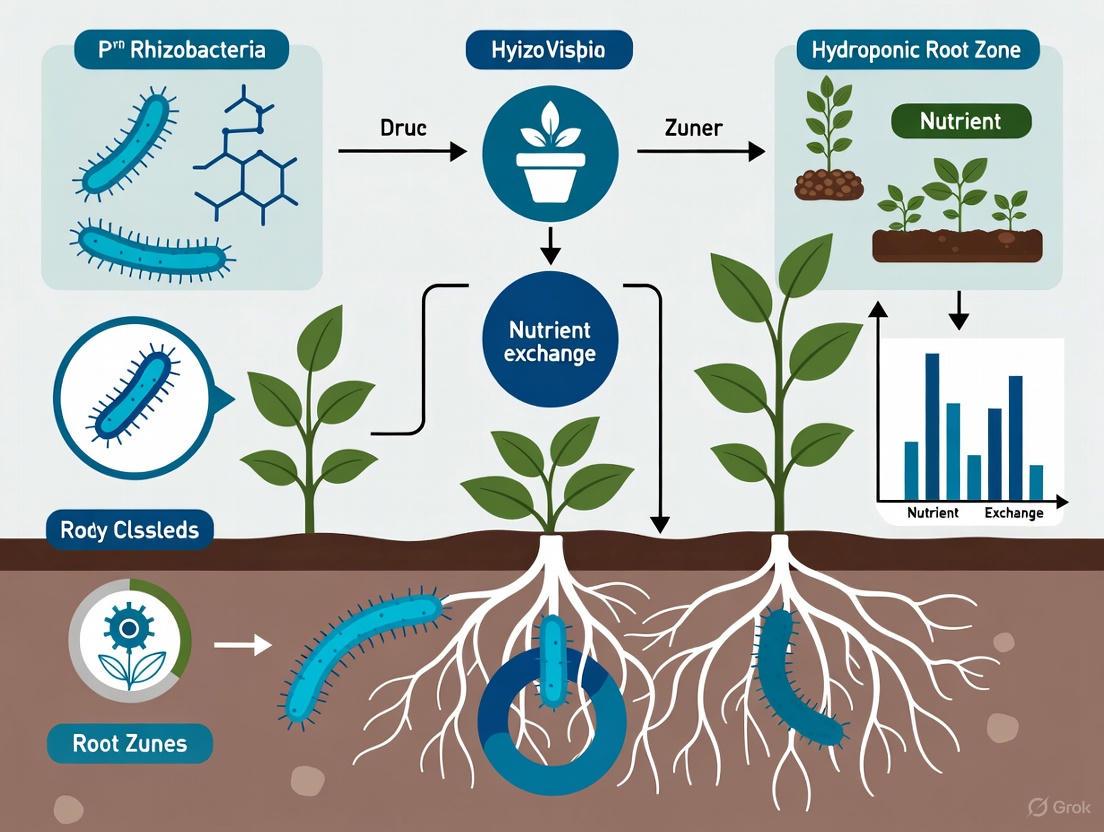

The diagram below summarizes the primary signaling pathways and mechanisms through which PGPR influence plant growth and defense.

Figure 1: PGPR Signaling Pathways and Mechanisms. PGPR enhance plant growth directly via nutrient provision, phytohormone production, and root architecture modification, and indirectly via induced systemic resistance (ISR), antibiosis, and competition. JA/ET: Jasmonic acid/Ethylene; SA: Salicylic acid.

The Paradigm Shift: Transitioning PGPR to Soilless Agriculture

Soilless agriculture encompasses systems where plants grow without soil, using nutrient-enriched water (hydroponics, aeroponics) or solid media (coco coir, perlite, rockwool) [4]. These systems eliminate soil-borne diseases and improve resource control but are inherently devoid of beneficial rhizosphere microorganisms [4] [7]. Introducing PGPR represents a fundamental advancement to overcome this limitation.

Rationale for PGPR in Soilless Systems

- Overcoming Natural Microbiome Absence: Soilless systems lack natural microbial communities, depriving plants of beneficial plant-microbe interactions [7]. PGPR inoculation introduces selected, functional microbiota.

- Enhancing Sustainability: PGPR can reduce dependence on mineral fertilizers. Research demonstrates that PGPR inoculation enables reducing mineral fertilizers by up to 80% in hydroponic lettuce without significant yield loss [6].

- Improving Plant Health and Quality: Beyond growth promotion, PGPR enhance nutritional quality by increasing bioactive compounds (phenols, flavonoids, vitamin C) in lettuce and other crops [6].

- System Efficiency: In controlled environments like hydroponics, PGPR effects are more consistent and reproducible compared to soil systems with complex, established microbiomes [7].

Key Experimental Evidence Supporting the Transition

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of PGPR in Soilless Cultivation Systems

| Crop | Soilless System | PGPR Strains Used | Key Growth Effects | Quality & Other Effects | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lettuce | Aeroponic | Consortium of 8 strains | ↑25% plant biomass; ↑leaf number & mass; ↑root lateral development | Altered leaf anatomy; Metabolic reprogramming | [7] |

| Lettuce | Floating Hydroponic | B. subtilis, B. megaterium, P. fluorescens | No yield loss with 80% MF; ↑leaf area, chlorophyll, DM | ↑Phenols, flavonoids, vitamin C; ↑mineral content | [6] |

| Tomato | Perlite-based | Enterobacter sp., Paenibacillus sp., Lelliottia sp. | ↑Vegetative biomass under combined water/nutrient stress | Alleviated oxidative stress; Metabolic changes | [8] |

| Melon | Coconut Fiber-Vermicompost | PGPR, Trichoderma, AMF | Enhanced microbial community function | ↑Nitrogen fixers, phosphate solubilizers | [9] |

| Marigold/Zinnia | Coco coir-based Plug | Enterobacter MN-17, Trichoderma spp. | ↑Seed germination; ↑root/shoot length; ↑seedling biomass | Improved substrate physico-chemical properties | [10] |

MF = Mineral Fertilizers; DM = Dry Matter; AMF = Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi.

Experimental Protocols for Soilless PGPR Research

Protocol: PGPR Inoculation in Aeroponic Systems

This methodology is adapted from the research on lettuce growth under suboptimal nutrient regimes [7].

1. Bacterial Consortium Preparation:

- Select and culture PGPR strains with complementary PGP traits (e.g., IAA production, P solubilization, N fixation).

- Grow strains individually in appropriate liquid media to late log phase.

- Centrifuge, wash, and resuspend in sterile buffer to a standardized density (e.g., 10⁸ CFU/mL).

- Mix strains in equal proportions to form the synthetic consortium.

2. Plant Material and Growth Conditions:

- Surface-sterilize seeds (e.g., 10 min in 50% NaClO with 0.025% Tween 20).

- Rinse thoroughly with sterile deionized water and imbibe for 4 hours.

- Sow seeds in sterile rockwool cubes pre-moistened with sterile water.

- Grow plantlets in a controlled environment (e.g., 26°C, 14/10h light/dark, ~500 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ PPFD).

3. System Inoculation and Cultivation:

- Transplant uniform plantlets into sterilized aeroponic systems.

- Inoculate by adding the PGPR consortium directly to the nutrient solution reservoir.

- Maintain a low-nutrient regime (e.g., 0.2% v/v Hydro A and B solutions) to stress plants and highlight PGPR effects.

- Aerate nutrient solution continuously and maintain pH (5.5–6.0) and EC.

4. Data Collection and Analysis:

- Biomass: Harvest and measure fresh/dry weight of shoots and roots.

- Root Architecture: Scan root systems and analyze architecture (total length, lateral root density).

- Leaf Anatomy: Process leaf samples for microscopy; measure palisade parenchyma thickness, airspace area.

- Physiology: Measure chlorophyll fluorescence, stomatal conductance, photosynthetic rate.

- Metabolomics: Conduct LC-MS/MS on leaf tissue to identify metabolic changes induced by PGPR.

The experimental workflow for this protocol is visualized below.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Aeroponic PGPR Inoculation. This protocol outlines steps from PGPR preparation to multi-faceted data analysis in a controlled soilless environment.

Protocol: Fertilizer Reduction with PGPR in Hydroponics

This protocol evaluates PGPR as partial substitutes for mineral fertilizers in floating lettuce cultures [6].

1. Bacterial Inoculum and Nutrient Solutions:

- Use a commercial PGPR product (e.g., Bacillus subtilis, B. megaterium, Pseudomonas fluorescens) or a defined laboratory mixture.

- Prepare a standard (100%) nutrient solution for the crop (e.g., N: 220 mg/L, P: 40 mg/L, K: 312 mg/L for lettuce).

- Prepare reduced concentration solutions (80%, 60%, 40%, 20% of standard).

2. Experimental Design and Treatment Setup:

- Arrange a randomized complete block design with treatments:

- 100% MF (Mineral Fertilizer) - Control

- 100% MF + PGPR

- 80% MF

- 80% MF + PGPR ... (repeat for 60%, 40%, 20% reductions)

- Use 50-L cultivation tanks as replicates (e.g., n=4, 10 plants/tank).

3. Inoculation and System Management:

- Inoculate treatment tanks with PGPR (e.g., 1 mL/L of 10⁹ CFU/mL solution) at the time of transplanting.

- Re-inoculate at 10-day intervals to maintain population.

- Maintain pH (5.5–6.0) and EC within target ranges.

- Monitor and adjust solutions as needed.

4. End-Point Evaluations:

- Yield: Measure individual plant weight per tank.

- Growth Parameters: Count leaves, measure leaf area, plant height, SPAD chlorophyll.

- Nutritional Quality: Analyze leaf tissue for minerals, phenols, flavonoids, vitamin C, total soluble solids.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform ANOVA and mean separation tests to identify significant differences between treatments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Soilless PGPR Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| PGPR Strains | Defined strains with known PGP traits (e.g., IAA production, N fixation, P solubilization). | Synthetic consortium construction [7]. |

| Growth Media | TSA, Ashby-mannitol agar, nutrient broth for specific strain culture and maintenance. | Culturing P. canadensis, A. chroococcum [5]. |

| Soilless Substrate | Inert or biologically active supports: rockwool, perlite, coco coir, vermicompost mixes. | Plant support and microbial habitat [7] [9] [10]. |

| Nutrient Solutions | Standardized formulations (e.g., Hoagland's, Hydro A & B); allow for precise dilution. | Creating optimal and suboptimal nutrient regimes [7] [6]. |

| Sterilization Agents | Sodium hypochlorite (NaClO), ethanol, autoclaving for surface and system sterilization. | Seed surface sterilization, system decontamination [7]. |

| Molecular Biology Kits | DNA/RNA extraction kits, reverse transcription kits, qPCR reagents for gene expression. | Quantifying defense gene expression (e.g., PR1, LOX) [5]. |

| Metabolomics Tools | LC-MS/MS, GC-MS systems and associated columns, solvents, and standards. | Profiling leaf metabolites (e.g., trehalose, myo-inositol) [7] [8]. |

| Root Scanning Software | WinRHIZO, ImageJ with specialized plugins for root architecture analysis. | Quantifying lateral root development and total root length [7]. |

The integration of PGPR into soilless agriculture marks a significant advancement toward more sustainable and efficient crop production. Evidence confirms that PGPR can successfully colonize plant roots in hydroponic, aeroponic, and aggregate systems, delivering growth promotion, stress protection, and quality enhancement benefits comparable to or even exceeding those observed in soil. The ability of PGPR to maintain yields with significantly reduced mineral fertilizer inputs is particularly promising for reducing environmental impacts and production costs.

Future research should focus on several critical areas: (1) Developing tailored PGPR consortia specifically designed for different soilless systems and major crop species; (2) Optimizing inoculation protocols (timing, frequency, delivery methods) for maximum persistence and efficacy; (3) Elucidating the complex molecular dialogues between PGPR and plants in controlled environments using multi-omics approaches; and (4) Conducting large-scale economic analyses to validate the commercial viability of PGPR applications in commercial soilless agriculture. As these developments progress, PGPR are poised to become indispensable components of precision soilless cultivation, contributing to the next generation of sustainable food production systems.

Direct and Indirect Plant Growth Promotion Mechanisms in Hydroponic Systems

Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) are beneficial bacteria that colonize plant roots and enhance plant growth through a diverse array of direct and indirect mechanisms [1]. In soilless cultivation systems, such as hydroponics, plants are typically grown with mineral nutrient solutions alone, lacking the beneficial microbial communities present in soil environments [6]. Introducing PGPR into hydroponic systems represents an innovative strategy to simulate these beneficial rhizospheric interactions, thereby promoting plant growth, reducing reliance on synthetic mineral fertilizers, and improving crop quality [6] [11].

The integration of PGPR is particularly relevant within the broader context of sustainable agriculture, aiming to minimize environmental footprints while maintaining high productivity [1] [12]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of the direct and indirect mechanisms by which PGPR function in hydroponic root zones, supported by experimental data, detailed methodologies, and visualizations tailored for research scientists and drug development professionals.

Direct Plant Growth-Promoting Mechanisms

Direct plant growth promotion occurs when PGPR facilitate resource acquisition or modulate plant hormonal levels.

Biofertilization

PGPR act as biofertilizers by enhancing the availability of essential nutrients, directly supporting plant nutrition.

- Nitrogen Fixation: Certain diazotrophic PGPR can convert atmospheric nitrogen (N₂) into ammonia, a plant-usable form [1] [12]. This is particularly valuable in nitrogen-limited conditions. For instance, studies have identified strains of Herbaspirillum huttiense and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus as potential nitrogen-fixing diazotrophs for crops like rice in hydroponic systems [11].

- Phosphate Solubilization: Phosphorus (P) in soils and nutrient solutions is often present in insoluble forms. PGPR, including strains of Bacillus megaterium and Pseudomonas fluorescens, secrete organic acids and enzymes that solubilize mineral phosphates, making them available for plant uptake [1] [6].

- Iron and Micronutrient Acquisition: Under iron-limiting conditions, PGPR produce siderophores—low-molecular-weight iron-chelating compounds [1]. These complexes are taken up by the plant, thereby improving iron nutrition. Strains of Lysinibacillus fusiformis and Microbacterium phyllosphaerae have demonstrated high siderophore production capabilities [11].

Phytostimulation

Phytostimulation involves the production or regulation of plant hormones (phytohormones) by PGPR.

- Auxin Production: Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) is the most common auxin and plays a fundamental role in root initiation and cell division [1]. A strain of Bacillus altitudinis isolated from a forest rhizosphere was reported to produce exceptionally high levels of IAA (739.9 ± 251.5 µg/mL), significantly stimulating root development in rice [11].

- Cytokinin and Gibberellin Production: PGPR can also synthesize other growth-promoting hormones like cytokinins and gibberellins, which influence cell division, shoot development, and seed germination [1].

Table 1: Quantitative Data on Direct Growth Promotion by Selected PGPR Strains

| PGPR Strain | Isolation Source | Primary Mechanism | Quantitative Effect | Experimental System | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus altitudinis R4(1)2 | Acer pseudoplatanus rhizosphere | IAA Production | 739.9 ± 251.5 µg/mL IAA | In vitro assay | [11] |

| B. subtilis, B. megaterium, P. fluorescens mix | Commercial product (Rhizofill) | Multiple (Biofertilizer) | 80% mineral fertilizer + PGPR yielded equivalent to 100% fertilizer | Hydroponic Batavia lettuce | [6] |

| Bacillus sp., Citrobacter sp. | Rice seeds | Phosphate Solubilization | High P-solubilization efficiency | In vitro assay | [1] |

| Lysinibacillus fusiformis | Uzungöl forest | Siderophore Production | Positive siderophore formation | In vitro assay | [11] |

Figure 1: Diagram of Direct PGPR Promotion Mechanisms. This figure illustrates the primary direct pathways through which PGPR enhance plant growth, including biofertilization and phytostimulation.

Indirect Plant Growth-Promoting Mechanisms

Indirect promotion occurs when PGPR reduce the inhibitory effects of plant pathogens or environmental stresses by acting as biocontrol agents.

Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR)

PGPR can prime the plant's immune system, leading to a heightened state of defense against a broad spectrum of pathogens [1] [5]. This phenomenon, known as Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR), is typically triggered by beneficial microorganisms and is regulated by jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene (ET) signaling pathways [1]. In some cases, ISR can also involve the salicylic acid (SA) pathway [5].

- Pathogen Suppression: Research on tomato plants demonstrated that inoculation with Peribacillus frigoritolerans and Pseudomonas canadensis strains reduced the incidence of the fungal pathogen Botrytis cinerea (gray mold) [5]. These strains preferentially activated different ISR pathways; P. frigoritolerans primed the SA pathway, while P. canadensis enhanced the JA/ET pathways, showcasing the mechanistic diversity of PGPR-mediated biocontrol [5].

- Antibiosis and Lytic Enzyme Production: PGPR suppress pathogens by producing antibiotics, hydrogen cyanide (HCN), and fungal cell wall-lysing enzymes (e.g., chitinases) [1] [12]. Bacillus and Pseudomonas are key genera known for such antagonistic activities [5].

Competition and Rhizosphere Colonization

A key trait for effective PGPR is rhizosphere competence—the ability to colonize and survive in the root zone [12]. Successful colonizers outcompete pathogens for limited resources like space and nutrients, particularly iron, through siderophore production [1] [12].

Table 2: PGPR-Mediated Biocontrol and Induced Resistance Examples

| PGPR Strain / Consortium | Target Pathogen | Host Plant | Proposed Mechanism | Key Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peribacillus frigoritolerans CDFICOS02 | Botrytis cinerea | Tomato | Induced Systemic Resistance (SA pathway) | Reduced disease incidence and oxidative stress | [5] |

| Pseudomonas canadensis CDFICOS03 | Botrytis cinerea | Tomato | Induced Systemic Resistance (JA/ET pathway) | Reduced disease incidence, increased plant biomass | [5] |

| Bacillus subtilis & other isolates | Fusarium sp., Rhizoctonia solani | Maize | Antagonism / Antibiosis | Antifungal activity against phytopathogens | [1] |

| B. subtilis, B. megaterium, P. fluorescens | Not specified | Batavia lettuce | Competitive exclusion / Rhizosphere competence | Improved overall plant health and nutrient uptake | [6] |

Figure 2: Diagram of Indirect PGPR Promotion via Biocontrol. This figure outlines how PGPR indirectly promote plant growth by inducing systemic resistance, producing antibiotics, and competing with pathogens.

Experimental Protocols for PGPR Research in Hydroponics

Robust experimental methodology is crucial for investigating PGPR mechanisms. Below are detailed protocols for key assays.

Protocol: Inoculation and Growth Promotion Assay in Floating Hydroponics

This protocol, adapted from [6], evaluates the effect of PGPR on lettuce in a floating raft system.

- 1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions: Utilize Batavia type lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. var. crispa). Establish a floating hydroponic system using aerated cultivation tanks (e.g., 50-L volume). Maintain greenhouse conditions at 18-23°C day/12-16°C night, with 60-70% relative humidity.

- 2. Nutrient Solution and Experimental Design: The control treatment should be a 100% mineral fertilizer solution. Prepare treatments with reduced mineral fertilizer (e.g., 80%, 60%, 40%, 20%) with and without PGPR supplementation. Maintain solution pH at 5.5-6.0 and EC at 1.3-2.2 dS m⁻¹.

- 3. Bacterial Inoculum Preparation: Use a commercial or specific PGPR consortium (e.g., Bacillus subtilis, B. megaterium, Pseudomonas fluorescens) with a concentration of 1 × 10⁹ CFU mL⁻¹.

- 4. Inoculation Procedure: Begin bacterial inoculation at the time of transplanting 14-day-old seedlings. Add the inoculum to the nutrient solution tank at a rate of 1 mL per liter. Re-inoculate at 10-day intervals throughout the cultivation period (e.g., 42 days).

- 5. Data Collection: At harvest, measure plant growth parameters: fresh and dry weight, plant height, leaf number, leaf area (using a leaf area meter like Li-3100), and SPAD chlorophyll content. Analyze nutrient uptake, phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and vitamin C.

Protocol: In Vitro Characterization of PGPR Traits

This protocol, based on [11] [5], details the isolation and functional characterization of PGPR strains.

- 1. PGPR Isolation and Storage: Isolate bacteria from rhizosphere soil samples (e.g., from forest ecosystems). Serially dilute soil suspensions and plate on appropriate media (e.g., Tryptic Soy Agar). Purify colonies and store pure cultures at -80°C in glycerol stock.

- 2. Indole-3-Acetic Acid (IAA) Production Assay:

- Procedure: Grow isolates in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth supplemented with L-tryptophan (100 µg mL⁻¹) for 72-96 hours. Centrifuge the culture, mix the supernatant with Salkowski's reagent, and incubate in darkness for 30 minutes.

- Analysis: Development of a pink color indicates IAA production. Quantify concentration using a spectrophotometer and a standard curve of pure IAA.

- 3. Phosphate Solubilization Assay:

- Procedure: Spot-inoculate isolates on Pikovskaya's (PKV) agar plates, which contain insoluble tricalcium phosphate.

- Analysis: Incubate plates at 28±2°C for 7-10 days. Observe for the formation of a clear halo zone around the bacterial growth, indicating phosphate solubilization. Measure the solubilization index.

- 4. Siderophore Production Assay:

- Procedure: Inoculate isolates on Chrome Azurol S (CAS) agar plates.

- Analysis: Incubate for up to 7 days. A color change of the blue agar to orange or yellow around the colony indicates siderophore production.

- 5. Nitrogen Fixation Potential (Acetylene Reduction Assay):

- Procedure: Grow cultures in nitrogen-free medium in sealed vials. Replace 10% of the headspace with pure acetylene gas.

- Analysis: Incubate with shaking. Measure ethylene production in the headspace using gas chromatography at intervals (e.g., 3, 7, 13, 20 days). Ethylene production indicates nitrogenase activity.

Figure 3: PGPR Isolation and Screening Workflow. This chart outlines the key steps involved in isolating PGPR from environmental samples, screening them for beneficial traits in vitro, and evaluating their efficacy in planta.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for PGPR Hydroponics Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Usage / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| PGPR Strains | Core bioinoculant for experiments | Commercial consortia (e.g., B. subtilis, B. megaterium, P. fluorescens) or newly isolated strains (e.g., Bacillus altitudinis, Herbaspirillum huttiense). |

| Nitrogen-Free Medium | To screen for diazotrophic (N-fixing) bacteria | JNFb, Burk's, or Ashby's medium for selective growth of nitrogen-fixing bacteria [11] [5]. |

| Pikovskaya's (PKV) Agar | To screen for phosphate-solubilizing bacteria | Contains insoluble tricalcium phosphate; formation of a halo indicates solubilization [11]. |

| Chrome Azurol S (CAS) Agar | To detect siderophore production | Universal assay for siderophores; color change from blue to orange/yellow is positive [11]. |

| Salkowski's Reagent | To detect and quantify Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) | Mixed with culture supernatant; pink color development indicates IAA production [11]. |

| Hydroponic Nutrient Solution | Base plant growth medium | Standard Hoagland's solution or custom formulations (e.g., control: 220 mg L⁻¹ N, 40 mg L⁻¹ P, 312 mg L⁻¹ K) [6]. |

| Floating Culture Tanks | Hydroponic growth system | Aerated tanks (e.g., 50-L volume) for growing plants like lettuce with roots immersed in nutrient solution [6]. |

| Leaf Area Meter | To measure plant growth and health | Instrument (e.g., Li-3100) for precise quantification of leaf area, a key growth parameter [6]. |

| SPAD Chlorophyll Meter | Non-destructive assessment of leaf chlorophyll | Device (e.g., SPAD-502) to estimate chlorophyll content, related to plant nitrogen status and health [6]. |

PGPR offer a multifaceted toolkit for enhancing plant performance in hydroponic systems through direct mechanisms like biofertilization and phytostimulation, as well as indirect mechanisms involving pathogen suppression via ISR and competition. The experimental data and protocols outlined provide a rigorous foundation for advancing research in this field. Future work should focus on elucidating the molecular dialogues in the hydroponic rhizosphere, optimizing PGPR consortia for specific crop-pathogen combinations, and scaling these sustainable solutions for commercial agriculture to reduce dependency on synthetic inputs.

The integration of Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) into hydroponic systems represents a paradigm shift in soilless agriculture, moving beyond traditional mineral fertilization towards a more biologically driven approach. Soilless cultivation systems, while offering advantages in resource efficiency and control, inherently lack the complex microbial consortia found in natural soils that support plant health and development [4]. Introducing specific, beneficial bacteria directly into the root zone is a strategy to reintroduce these functions, creating a more robust and resilient cultivation ecosystem [13] [14].

Among the vast diversity of PGPR, three bacterial genera—Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Azospirillum—have emerged as the most extensively studied and promising for hydroponic applications [15]. These genera form the core of current research and commercial bioinoculants due to their proven efficacy in enhancing plant growth, facilitating nutrient uptake, and providing biotic and abiotic stress protection in controlled environments [15] [6]. This technical guide synthesizes the current scientific knowledge on these key genera, providing researchers with a detailed overview of their mechanisms, experimental applications, and practical protocols for integration into hydroponic root zone research.

Mode of Action: A Comparative Analysis

The plant-beneficial effects of Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Azospirillum are mediated through a diverse array of direct and indirect mechanisms. These modes of action can be broadly categorized into biofertilization, phytostimulation, and biocontrol.

Table 1: Core Mechanisms of Action of Key PGPR Genera in Hydroponics

| Mechanism | Bacillus | Pseudomonas | Azospirillum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen Fixation | Limited | Limited (some strains) | Primary Mechanism (Non-symbiotic) [16] |

| Phosphate Solubilization | Strong [6] | Strong [17] | Moderate [16] |

| Siderophore Production | Yes | Strong [15] [18] | Yes |

| Phytohormone Production (e.g., IAA) | Yes [6] | Yes (Key trait) [17] | Strong (Primary mechanism) [19] [16] |

| 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-Carboxylate (ACC) Deaminase | Yes [13] | Yes [13] | Yes [13] |

| Biocontrol / Antibiosis | Strong (e.g., lipopeptides) [15] [18] | Strong (e.g., antibiotics, cyanide) [19] [15] | Limited |

| Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR) | Yes [4] [18] | Yes [4] [18] | Yes [18] |

| Root Architecture Modification | Moderate | Moderate | Very Strong (Lateral root & hair promotion) [19] [3] |

Table 2: Documented Hydroponic Crop Responses to PGPR Inoculation

| PGPR Genus | Crop | Observed Effect | Experimental Context & Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus | Batavia Lettuce | ↑ Yield, ↑ nutrient uptake, ↑ phenols, flavonoids, vitamin C with 20-80% reduced mineral fertilizer [6] | Floating culture; Consortium (B. subtilis, B. megaterium, P. fluorescens) |

| Pseudomonas | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | ↑ Fruit yield (up to 73%), ↑ lycopene content, ↑ fruit firmness with 50% reduced NPK fertilization [17] | Greenhouse hydroponics; Individual strains (P. putida, P. fluorescens) |

| Azospirillum | Arabidopsis thaliana | Induction of lateral root branching via auxin-dependent signaling & plasmodesmata regulation [19] | In vitro bacterial-plant interaction system |

| Azospirillum | Lettuce, Tomatoes, Cereals | Improved root development, yield, and stress tolerance across various crops [16] | Commercial application data and field trials |

Experimental Protocols for Hydroponic PGPR Research

Protocol: Evaluating PGPR as a Partial Substitute for Mineral Fertilizers

This protocol is adapted from a 2024 study on Batavia lettuce in a floating hydroponic system [6].

Objective: To determine the efficacy of a PGPR consortium in maintaining yield and quality of lettuce under reduced mineral fertilization.

Materials:

- Plant Material: Batavia lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) cv. 'Caipira' seeds.

- PGPR Inoculant: Commercial product (e.g., Rhizofill) containing Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus megaterium, and Pseudomonas fluorescens at a concentration of 1 × 10^9 CFU/mL.

- Growth System: 50-L cultivation tanks configured as a floating raft system.

- Nutrient Solution: Standard Hoagland's solution or equivalent.

Method:

- Seedling Preparation: Germinate seeds and grow seedlings for 14 days before transplanting into the hydroponic system.

- Experimental Design: Establish a completely randomized design with the following treatments:

- Control: 100% mineral fertilizer (MF).

- Treated Groups: 100% MF + PGPR, 80% MF, 80% MF + PGPR, 60% MF, 60% MF + PGPR, 40% MF, 40% MF + PGPR, 20% MF, 20% MF + PGPR.

- PGPR Inoculation: At the time of transplanting, add the PGPR inoculant to the nutrient solution tanks at a rate of 1 mL per liter (e.g., 50 mL per 50-L tank). Repeat this inoculation every 10 days throughout the 42-day cultivation period.

- System Management: Maintain pH between 5.5–6.0 and Electrical Conductivity (EC) between 1.3–2.2 dS/m.

- Data Collection: At harvest, measure:

- Growth Parameters: Plant fresh and dry weight, leaf number, leaf area, root biomass.

- Physiological Traits: SPAD chlorophyll content.

- Yield: Total marketable weight per plant.

- Quality Metrics: Concentrations of minerals, phenols, flavonoids, vitamin C, and total soluble solids.

Protocol: Investigating PGPR-Induced Root Architectural Changes

This protocol is based on a 2025 study using Arabidopsis thaliana and Azospirillum baldaniorum Sp245 [19].

Objective: To analyze the molecular and morphological changes in root system architecture induced by PGPR inoculation.

Materials:

- Biological Material:

- Azospirillum baldaniorum Sp245 strain.

- Arabidopsis thaliana seeds: Wild-type (Col-0), transgenic DR5:GUS (auxin-responsive reporter), and mutant lines (e.g., pdlp5-1 DR5:GUS).

- Growth Medium: Solid half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium.

- Equipment: Laminar flow hood, plant growth chambers, microscope.

Method:

- Bacterial Preparation: Grow A. baldaniorum in appropriate liquid medium to mid-log phase.

- Plant Inoculation:

- Surface-sterilize A. thaliana seeds and stratify at 4°C for 48 hours.

- Sow seeds on sterile plates containing half-strength MS medium.

- After germination, carefully spot-inoculate 10 µL of bacterial suspension (~10^8 CFU/mL) near the root tip of 6-day-old seedlings. Use sterile medium as a control.

- Co-Cultivation: Grow plants vertically in a controlled environment chamber (e.g., 16/8 h light/dark, 22°C).

- Phenotypic Analysis: After 6 days of co-cultivation:

- Root Morphometry: Using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ), measure primary root length, lateral root density, and lateral root length.

- Molecular Analysis:

- GUS Staining: For DR5:GUS lines, perform histochemical GUS staining to visualize and quantify auxin response maxima.

- Gene Expression: Analyze expression of genes involved in auxin transport (e.g., PIN, AUX/LAX) and symplastic trafficking (e.g., PDLP5) via qRT-PCR.

Figure 1: Workflow for analyzing PGPR-induced root architectural changes.

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Dialog

The beneficial interactions between PGPR and plants are governed by a complex molecular dialogue, often initiated by root exudates. These exudates act as signals that attract specific bacteria and support their growth in the rhizosphere [18]. The subsequent plant responses, particularly root morphological changes, are frequently mediated by bacterial interference with plant hormone signaling, most notably auxin.

The Azospirillum-Root Auxin Signaling Pathway

A. baldaniorum Sp245 is a model for understanding how PGPR, through auxin production, systemically alters root system architecture. The bacteria-derived IAA integrates into the plant's endogenous auxin signaling network, leading to transcriptional reprogramming and stimulated lateral root development [19].

Figure 2: Azospirillum-induced root branching pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Hydroponic PGPR Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application in PGPR Research |

|---|---|

| Half-Strength MS Medium | Standardized in vitro plant growth medium for sterile co-cultivation assays and phenotypic analysis of root architecture [19]. |

| DR5:GUS Arabidopsis Line | Reporter plant line where the expression of β-glucuronidase (GUS) is driven by a synthetic auxin-responsive promoter. Essential for visualizing and quantifying spatial auxin response in root tissues upon PGPR inoculation [19]. |

| PGPR Consortia (e.g., Rhizofill) | Commercial or custom-formulated mixtures of defined PGPR strains (e.g., B. subtilis, B. megaterium, P. fluorescens). Used for applied research on biofertilization and plant growth promotion in hydroponic systems [6]. |

| SPAD Chlorophyll Meter | Portable, non-destructive device for rapid assessment of leaf chlorophyll content, serving as an indicator of plant nitrogen status and overall photosynthetic health in PGPR trials [6]. |

| GUS Staining Kit | Histochemical kit containing X-Gluc substrate for visualizing auxin response zones in root and shoot tissues of DR5:GUS reporter lines after PGPR treatment [19]. |

The body of research unequivocally demonstrates that Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Azospirillum are cornerstone genera for advancing hydroponic productivity and sustainability. Their distinct yet complementary mechanisms of action—ranging from biofertilization and phytostimulation to biocontrol—provide a multi-faceted toolkit for enhancing crop performance. The experimental evidence confirms that these PGPR can not only maintain but often improve yield and nutritional quality under reduced mineral fertilization, a critical step towards reducing the environmental footprint of soilless agriculture [17] [6].

Future research should focus on elucidating the fine-scale molecular dialogues, including the specific root exudate signals that foster optimal colonization [18], and the development of customized, crop-specific PGPR consortia. The successful integration of these powerful microbial allies into hydroponic root zones heralds a new era of efficient, resilient, and sustainable crop production for a growing global population.

Rhizosphere Colonization Dynamics in Soilless Versus Traditional Environments

The rhizosphere, the dynamic zone of soil directly influenced by plant roots, serves as a critical interface for plant-microbe interactions. The colonization dynamics of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) within this niche vary significantly between soilless and traditional soil-based environments. This technical review synthesizes current research to elucidate how factors such as microbial diversity, root architecture, water dynamics, and agricultural management practices create distinct selective pressures that shape PGPR colonization. In soilless systems, the absence of a complex soil matrix and indigenous microbial communities presents a unique environment for colonization, while traditional soils offer a more complex, but competitive, ecological niche. Understanding these dynamics is paramount for optimizing PGPR application to enhance plant growth, nutrient uptake, and stress resilience across different cultivation paradigms, contributing to more sustainable agricultural systems.

The rhizosphere is a hotspot of microbial activity, driven by the release of root exudates including organic acids, phytosiderophores, sugars, and amino acids [3]. This chemical cocktail attracts and supports a rich microbial community, the rhizo-microbiome, which is distinct in composition from the microbial community of the surrounding bulk soil [3]. Within this community, Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) are beneficial bacteria that colonize plant roots and enhance plant growth through direct and indirect mechanisms [3]. Direct mechanisms include the production of phytohormones (e.g., auxins, cytokinins), biological nitrogen fixation, and solubilization of minerals like phosphorus [3] [20]. Indirectly, PGPR can suppress phytopathogens through competition, antagonism, and by inducing systemic resistance in the host plant [3] [20].

The successful establishment of PGPR, a process termed root colonization, is a sine qua non for these plant-beneficial effects [3]. This process involves the competitive migration of bacteria to plant roots, their survival in the rhizosphere, and their stable growth and formation of microcolonies on the root surface [21]. The efficacy of PGPR is therefore not solely an intrinsic property of the bacterial strain but is heavily influenced by the environmental context of the root zone, which differs profoundly between traditional soil ecosystems and engineered soilless systems.

Comparative Analysis of Rhizosphere Environments

The environmental conditions and microbial habitats in the rhizosphere of traditional soil-based systems and soilless cultures create contrasting scenarios for PGPR colonization and function.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Traditional Soil vs. Soilless Rhizosphere Environments

| Characteristic | Traditional Soil Environment | Soilless Environment |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Matrix | Complex soil structure with solid, liquid, and gaseous phases [22] | Simplified matrix (e.g., water, air, inert substrate like rockwool) [23] |

| Native Microbiome | High diversity and abundance of indigenous microbial communities [24] [25] | Typically low microbial diversity unless introduced [20] [6] |

| Water & Porosity | Meso-porosity crucial for microbial habitats; water holding capacity varies with management [22] | Roots often suspended in nutrient solution; high water availability [26] [23] |

| Management Influence | Tillage decreases bulk density and penetration resistance but can harm microbial habitats [22] | Precise control over nutrient composition, pH, and EC [23] [6] |

| Microbial Diversity | Higher alpha diversity in organic systems; community structure influenced by farming practice [24] [25] | Community structure is more uniform and directly shaped by the nutrient solution [24] |

Traditional Soil Environments

In traditional agriculture, soil structure is a key determinant of the rhizosphere habitat. Conservation practices like no-till or reduced tillage maintain higher soil penetration resistance and bulk density but support a more complex and diverse microbial habitat, positively associated with microbial biomass and diversity [22]. A long-term study found that meso-porosity was positively linked to microbial diversity, likely by providing additional niche space, and fungal diversity was strongly correlated with soil water content in macropores [22]. Furthermore, organic management increases soil water holding capacity compared to conventional management, creating a more stable environment for microbial activity [22].

The microbial community in soil is also shaped by agricultural practices. Research on peanut crops demonstrated that organic cultivation led to a more uniform bacterial community structure and generally higher microbial alpha diversity (including Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson indices) compared to conventional inorganic practices [24]. Specific bacterial phyla like Proteobacteria were significantly more abundant in organic soils, while TM6 and Firmicutes were more associated with inorganic soils [24]. Similarly, a study on maize found that the rhizosphere microbiota diversity was higher under organic farming than under conventional systems, with the presence of beneficial groups like arbuscular mycorrhizae (Glomeromycota) being almost exclusively detected in the organic system [25].

Soilless Environments

Soilless cultivation systems, such as hydroponics, lack a traditional soil matrix. Instead, plant roots are exposed to a nutrient solution, either directly (as in Deep Water Culture) or via an inert substrate [26] [23]. A primary distinction is the general absence of a native soil microbiome, meaning PGPR do not have to compete with established indigenous bacterial communities [20]. This can be an advantage for introducing specific PGPR strains, as their colonization success may be higher in the absence of competition [20].

In these controlled systems, environmental parameters are precisely managed. The nutrient solution's pH and electrical conductivity (EC) are carefully maintained within optimal ranges (e.g., pH 5.5–6.0, EC 1.3–2.2 dS/m for lettuce) to ensure nutrient availability [6]. This level of control extends to the introduction of beneficial microbes. Since soilless systems naturally lack these organisms, they must be deliberately introduced, offering a unique opportunity to tailor the rhizosphere microbiome for improved plant nutrition and health [20] [6].

Quantitative Data on PGPR Performance

Empirical studies demonstrate the tangible effects of PGPR inoculation and the contrasting outcomes in different cultivation systems. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research.

Table 2: Quantitative Effects of PGPR and Farming Practices on Plant and Microbial Parameters

| Study System | Treatment | Key Quantitative Results | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peanut (Field) | Organic vs. Conventional Cultivation | Yields in organic system decreased by 10–93% compared to conventional. Microbial alpha diversity indices generally higher in organic plots. | [24] |

| Lettuce (Hydroponic) | 80% Mineral Fertilizer (MF) + PGPR vs. 100% MF | Yield with 80% MF + PGPR was not significantly different from 100% MF control. PGPR application improved mineral content, phenols, flavonoids, and vitamin C. | [6] |

| Pepper (Pot Experiment) | Rhizosphere-Domesticated PGPR vs. Ancestral Strain | Inoculation with evolved strain 9P41 increased plant height by 11.4%, root length by 28.7%, aboveground biomass by 21.0%, and underground biomass by 29.1%. | [21] |

| Tomato (Controlled) | Soil vs. Deep Water Culture (DWC) | Plants in hydroponic systems (DWC, Drip) transpired less water and had lower product water use. Lycopene and β-carotene levels were similar or higher in DWC. | [23] |

| Maize (Field) | Organic vs. Conventional Farming | Rhizosphere microbiota diversity was significantly higher in the organic farming system for both maize populations studied. | [25] |

PGPR Efficacy in Hydroponic Systems

The potential of PGPR to reduce reliance on mineral fertilizers in soilless systems is particularly promising. In a floating culture of Batavia lettuce, researchers progressively reduced synthetic mineral fertilizers from 20% to 80%, using a commercial PGPR consortia (Bacillus subtilis, B. megaterium, Pseudomonas fluorescens) as a substitute [6]. Remarkably, the combination of 80% mineral fertilizer with PGPR produced a lettuce yield that was statistically equivalent to the 100% mineral fertilizer control [6]. Beyond yield maintenance, PGPR application significantly enhanced the nutritional quality of the lettuce, leading to higher levels of essential minerals, phenols, flavonoids, and vitamin C [6]. This demonstrates that PGPR can act as a sustainable tool for nutrient management in hydroponics, reducing fertilizer input while maintaining or even improving yield and quality.

Root Colonization and Plant Growth Promotion

The direct link between enhanced root colonization and plant growth promotion was elegantly demonstrated in a recent rhizosphere domestication study. By serially passaging the PGPR strain Bacillus velezensis SQR9 through the pepper rhizosphere for 20 cycles, researchers evolved strains with 1.5 to 2.9-fold greater root colonization capability compared to the ancestral strain [21]. Through a multi-step phenotypic screening, an evolved strain (9P41) was identified that, when inoculated into pepper plants, led to significant increases in root length (28.7%) and overall plant biomass [21]. This study highlights that directed evolution for improved root colonization is a viable strategy for developing more effective microbial inoculants.

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Quantifying Localized Rhizosphere pH Dynamics

The following protocol, adapted from a 2025 methodology paper, allows for high-resolution, quantitative mapping of pH changes along the root axis [27].

Principle: A pH indicator dye (bromocresol purple) provides a visual assessment of pH changes, which is then quantified using a precision pH electrode in specific regions of interest.

Materials:

- pH indicator plates: 0.006% (w/v) bromocresol purple, 0.2 mM CaSO₄, 0.8% plant agar, pH adjusted to 6.4.

- Equipment: pH Electrode InLab Surface Pro-ISM, growth chamber, ImageJ software.

Procedure:

- Plant Growth: Grow seedlings (e.g., Arabidopsis) vertically on appropriate agar medium for 10 days under controlled conditions.

- Transfer to Indicator Plates: Gently transfer seedlings onto the surface of the prepared bromocresol purple plates. Include a control plate without seedlings.

- Incubation: Incubate plates vertically in a growth chamber for 24 hours.

- Image Analysis: Capture photographs of the plates. Generate lookup table (LUT) images using ImageJ to visualize pH variations.

- Localized pH Measurement:

- Measure the pH of the control plate (Start pH).

- Carefully remove seedlings from the assay plate.

- Use the surface pH electrode to measure the pH in the specific rhizosphere region of interest (End pH).

- Calculation: Calculate the change in rhizosphere pH (ΔpH) for the localized region using the formula: ΔpH = End pH - Start pH. A negative value indicates acidification [27].

Rhizosphere Domestication for Enhanced PGPR Colonization

This protocol describes an experimental evolution approach to breed PGPR strains with superior root colonization and plant growth-promoting abilities [21].

Principle: Repeatedly cycling a bacterial population through the host plant's rhizosphere applies selective pressure for traits beneficial for survival and colonization in that specific environment.

Materials:

- PGPR strain (e.g., Bacillus velezensis SQR9).

- Host plant seeds (e.g., pepper, Capsicum annuum).

- Sterile growth containers and vermiculite.

Procedure:

- Initial Inoculation: Transplant sterile seedlings into containers with sterile vermiculite. Inoculate the rhizosphere with the ancestral PGPR strain (e.g., 10⁵ CFU/ml).

- Growth Cycle: Cultivate plants for 1 week under controlled conditions.

- Harvest and Transfer:

- Harvest plant roots and transfer them to a centrifuge tube with a saline solution (e.g., 6 g/L NaCl) and glass beads.

- Vortex the tube to dislodge root-associated bacteria.

- Use 1 ml of this bacterial suspension to inoculate a new batch of sterile seedlings, initiating the next cycle.

- Plate serial dilutions of the remaining suspension to monitor population density.

- Repetition: Repeat the transfer process for multiple cycles (e.g., 20 cycles). Maintain several independent evolutionary lineages.

- Screening: At the end of the domestication process, randomly select evolved colonies and screen them for enhanced plant growth-promoting traits (e.g., IAA production, siderophore production, biofilm formation) and superior root colonization capacity in pot experiments compared to the ancestral strain [21].

Figure 1: Rhizosphere Domestication Workflow for PGPR Improvement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Rhizosphere Colonization Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Bromocresol Purple | pH indicator dye for visualizing rhizosphere acidification/alkalization [27]. | Mapping spatial pH variations along the root axis in response to nutrient availability [27]. |

| InLab Surface Pro-ISM Electrode | Precision pH electrode for measuring pH in thin films and surfaces [27]. | Quantifying localized pH changes in the rhizosphere on agar plates after indicator dye visualization [27]. |

| Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) | Beneficial bacteria used as biofertilizers and biostimulants [3] [6]. | Inoculating plants to enhance growth, nutrient uptake, and stress tolerance in soil and soilless systems [21] [6]. |

| Hoagland Agar Medium | Standardized plant growth medium providing essential macro and micronutrients [27]. | Growing seedlings under controlled nutritional conditions for standardized experimental assays [27]. |

| Bacillus velezensis SQR9 | A well-characterized PGPR strain [21]. | Used as a model organism for studying root colonization mechanisms and for domestication experiments to improve fitness [21]. |

| GFP-chloramphenicol Plasmid | Genetic construct for labeling bacterial strains with fluorescent and antibiotic resistance markers [21]. | Chromosomal integration into PGPR for reliable strain tracking and quantification during colonization studies [21]. |

The colonization dynamics of PGPR are fundamentally shaped by their environmental context. Traditional soil systems present a complex, competitive landscape where management practices like organic farming and conservation tillage can foster a more diverse and robust microbial community conducive to PGPR function. In contrast, soilless systems offer a controlled, simplified environment where the absence of a native microbiome facilitates the targeted introduction of specific PGPR strains, allowing for precise manipulation of the rhizosphere to enhance plant performance and reduce fertilizer inputs.

The emerging toolkit for researchers—including sophisticated pH mapping, directed evolution of PGPR via rhizosphere domestication, and the integration of PGPR into hydroponic nutrient management—provides powerful means to unravel and optimize these dynamics. Future research should focus on elucidating the molecular signaling pathways underpinning plant-PGPR communication in different media, and on developing consortia of strains that work synergistically to support plant health and productivity in both traditional and soilless agriculture.

Nutrient Solubilization and Phytohormone Production in Liquid Media

Within the context of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) research for hydroponic root zones, understanding the specific mechanisms of action in liquid media is paramount. Unlike soil-based systems, hydroponic environments are inherently devoid of beneficial microorganisms, depriving plants of their growth-promoting advantages [7]. The introduction of PGPR into these soilless culture systems presents an opportunity to exploit their potential benefits while avoiding the inconsistencies often observed in field applications [7] [4]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the core processes of nutrient solubilization and phytohormone production by PGPR in liquid environments, with a focus on methodological protocols, quantitative outcomes, and practical applications for hydroponic cultivation systems. The precise monitoring and control offered by hydroponic systems make them ideal platforms for elucidating the intricate metabolic dialog between plants and beneficial microbes, accelerating the design of new PGPR consortia for use as microbial biostimulants [7].

Quantitative Profiling of Bacterial Performance in Liquid Media

The efficacy of PGPR in liquid media is quantified through standardized assays that measure their capacity to solubilize essential nutrients and produce growth-regulating phytohormones. The data below summarizes performance metrics across diverse bacterial species.

Table 1: Quantitative Profiling of Phosphate Solubilization by PGPR in Liquid Media

| Bacterial Strain | Source/Context | Substrate Solubilized | Quantitative Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrobacter sp. SB04-3 | Wild sorghum rhizosphere | Various insoluble phosphates | >100 mg/L P released | [28] |

| Bacillus siamensis R27 | Cd-contaminated rhizosphere | Insoluble phosphate | 385.11 mg/L P solubilized | [29] |

| Consortium of 8 PGPR strains | Synthetic consortium for lettuce | N/A | 25% increase in plant biomass | [7] |

| Selected PGPR Strains | Reclaimed smelter waste deposit | Tricalcium phosphate | All 15 isolates showed medium to high solubilization | [30] |

| Mineral Solubilizing Strains (MS2) | Rhodes grass rhizosphere | Tricalcium phosphate in PVK broth | High available P concentration; significant pH reduction | [31] |

Table 2: Quantitative Profiling of Phytohormone Production by PGPR in Liquid Media

| Bacterial Strain | Phytohormone/Compound | Production Level | Significance/Context | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus siamensis R27 | Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) | 35.92 mg/L | Cd-resistant strain promoting lettuce growth | [29] |

| PGPR from smelter waste | IAA-like compounds | Up to 60 µg/mL | 14 of 15 isolates were positive for IAA production | [30] |

| PGPR from argan rhizosphere | Indole acetic acid | 25 of 52 isolates tested positive | Selected for enhancing argan seed germination | [32] |

| PGPR Consortium | IAA, Cytokinins, Gibberellins | N/A | Stimulated cell division, root development, and leaf growth | [7] |

Table 3: Comprehensive Mineral Solubilization Profiles of PGPR in Liquid Media

| Bacterial Strain | Phosphorus | Potassium | Zinc | Manganese | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSB Strains (Various) | Positive (8 strains) | Positive (37.5% of strains) | Positive (75% of strains) | Positive (75% of strains) | [31] |

| Citrobacter sp. SB04-3 | High | N/D | N/D | N/D | [28] |

| Bacillus siamensis R27 | High | N/D | N/D | N/D | [29] |

Experimental Protocols for Core PGPR Mechanisms

Protocol for Phosphate Solubilization Quantification

Principle: This method quantifies a bacterium's ability to solubilize insoluble phosphorus in liquid culture by converting it to soluble orthophosphates, which are then measured colorimetrically [28] [31].

Materials:

- Pikovskaya (PVK) Broth: Contains insoluble tricalcium phosphate as the sole P source [30] [31].

- Spectrophotometer: Agilent Technologies or equivalent for colorimetric analysis.

Procedure:

- Inoculate purified bacterial strains into sterile PVK broth.

- Incubate cultures at 30 ± 1°C for 7 days in an orbital shaker [31].

- After incubation, harvest bacterial cells by centrifugation or filtration through Whatman filter paper No. 42 [31].

- Determine the concentration of solubilized phosphorus in the filtrate using the colorimetric method (ascorbic acid method) via a spectrophotometer set to 882 nm [28] [31].

- Simultaneously, measure the pH of the spent medium to correlate P solubilization with acid production [31].

Calculation: The Phosphate Solubilization Efficiency (PSE%) can be calculated if initial screening was done on solid media, using the formula: PSE% = (Solubilization zone diameter / Colony diameter) × 100 [31].

Protocol for Indole-3-Acetic Acid (IAA) Production Quantification

Principle: This protocol quantifies IAA production by PGPR in liquid media, with or without the precursor L-tryptophan, using colorimetric detection with Salkowski's reagent [29] [32].

Materials:

- L-Tryptophan-Amended Medium: Nutrient broth supplemented with 0.1% L-tryptophan [29].

- Salkowski's Reagent: 2% 0.5M FeCl₃ in 35% perchloric acid [29].

- Spectrophotometer.

Procedure:

- Inoculate bacterial strains into liquid medium with and without L-tryptophan.

- Incubate in the dark at 30°C for 24-48 hours to prevent photo-degradation of IAA [29].

- Centrifuge the cultures at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes to obtain a cell-free supernatant.

- Mix 1 mL of supernatant with 2 mL of Salkowski's reagent and vortex thoroughly.

- Incubate the mixture in the dark at room temperature for 30 minutes for color development (pink hue).

- Measure the absorbance of the solution at 530 nm [29].

- Determine the IAA concentration by comparing absorbance values to a standard curve of pure IAA (0-100 µg/mL).

Signaling Pathways and Metabolic Workflows in PGPR-Plant Interactions

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected signaling pathways and mechanisms through which PGPR in hydroponic root zones influence plant growth, encompassing both nutrient solubilization and phytohormone production.

PGPR Mechanisms and Plant Growth Responses - This diagram visualizes the core mechanisms of Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) in liquid media and their subsequent effects on plant physiology. The pathways show how nutrient solubilization and phytohormone production directly influence root architecture, nutrient uptake, biomass accumulation, and stress tolerance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for PGPR Mechanism Studies

| Reagent/Medium | Composition/Type | Function in PGPR Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pikovskaya (PVK) Medium | Agar or broth with insoluble tricalcium phosphate | Qualitatively and quantitatively screens for phosphate-solubilizing bacteria by formation of halo zones [30] [31]. | Quantifying P solubilized in broth by Citrobacter sp. [28]. |

| Salkowski's Reagent | 2% 0.5M FeCl₃ in 35% HClO₄ | Colorimetric detection and quantification of bacterial IAA production; reacts with IAA to form pink complex [29]. | Measuring IAA production of 35.92 mg/L by Bacillus siamensis R27 [29]. |

| L-Tryptophan | Amino acid precursor | Added to growth medium as a precursor to stimulate and enhance IAA biosynthesis by bacterial strains [29]. | Standard component in IAA production assays to ensure maximum yield [29]. |

| Aleksandrov Medium | Agar or broth with insoluble potassium minerals | Screens for potassium-solubilizing bacteria; positive result indicated by halo zone [31]. | Testing K solubilization by Rhodes grass isolates [31]. |

| Bunt & Rovira Medium | Agar or broth amended with ZnO | Screens for zinc-solubilizing bacteria; positive result indicated by halo zone [31]. | Testing Zn solubilization by Rhodes grass isolates [31]. |

| N-Free Medium (JNFb) | Liquid medium without nitrogen | Used to assess and quantify biological nitrogen fixation capability of bacterial isolates [30]. | Total N analysis in cultures of isolates from smelter waste [30]. |

The precise quantification of nutrient solubilization and phytohormone production in liquid media provides the scientific foundation for advancing PGPR applications in hydroponic root zones. The structured data and standardized protocols presented in this guide offer researchers a reproducible framework for screening and characterizing potent bacterial strains. The integration of these high-performing PGPR into soilless cultivation systems represents a promising, sustainable strategy to enhance crop productivity, reduce reliance on synthetic fertilizers, and improve plant resilience within controlled-environment agriculture. Future research should focus on optimizing consortium compositions and delivery methods to maximize synergistic effects in diverse hydroponic configurations.

Microbial Community Interactions in Hydroponic Root Zones

The rhizosphere, the dynamic zone of soil directly influenced by plant roots, serves as a critical interface for complex biochemical and ecological interactions that sustain plant growth [33]. In soilless cultivation systems, this environment is fundamentally altered, necessitating the intentional introduction of beneficial microbes to recapture these essential interactions. This whitepaper synthesizes current research on the composition, molecular mechanisms, and ecological relevance of microbial communities, specifically plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), in hydroponic root zones. Framed within a broader thesis on advancing sustainable agriculture, this review provides a technical guide for researchers, detailing the modes of action of PGPR, summarizing experimental data into comparable tables, and providing standardized protocols for their application in controlled environments.

In traditional soil-based agriculture, the rhizosphere is a hotspot of microbial activity, regulated by chemical exchanges among plants, soil, and microorganisms [33]. Soilless culture systems (SCS), including hydroponics, eliminate soil-borne problems but inherently lack this native beneficial microbiome [6] [4]. The primary strategy in soilless agriculture has been to maintain a clean, sterile system; however, a paradigm shift is occurring with the intentional introduction of beneficial microorganisms to enhance plant resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses [4]. In hydroponics, the root zone is not a traditional soil rhizosphere but remains a bioactive environment where roots secrete chemicals, creating a specialized interface for microbial colonization and interaction [20] [34]. Understanding and managing the interactions in this engineered rhizosphere is key to unlocking the full potential of soilless agriculture for sustainable crop production.

Signaling and Molecular Mechanisms of Interaction

The interactions between plant roots and microbes in the rhizosphere are mediated by a complex array of chemical signals.

The Chemical Trio: Root Exudates, mVOCs, and rVOCs

Communication within the hydroponic root zone is governed by a trio of chemical classes:

- Root Exudates: These are mostly non-volatile organic molecules secreted by plant roots, such as flavonoids and strigolactones. They serve as selective filters, attracting compatible microbial species and initiating symbiotic relationships [33]. For instance, flavonoids secreted by legume roots are detected by rhizobia, triggering the formation of nitrogen-fixing nodules [33].

- Microbial Volatile Organic Compounds (mVOCs): These are chemically diverse volatile molecules released by soil bacteria and fungi, including alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, and terpenoids [33]. Functions of mVOCs are diverse, including the stimulation of root development, enhancement of systemic resistance, and suppression of pathogen activity [33]. A seminal study identified that 2,3-butanediol, released by Bacillus subtilis GB03 and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens IN937a, significantly enhances plant growth [33].

- Root Volatile Organic Compounds (rVOCs): Plants also emit volatiles from their roots, which support soil microorganisms in establishing ecological niches [33].

These three chemical classes create intricate feedback loops that drive ecological processes and enable plants to adapt to environmental challenges [33].

Direct and Indirect PGPR Mechanisms

PGPR influence plant growth through direct and indirect mechanisms, which are particularly valuable in the nutrient-limited context of hydroponics.

- Direct Mechanisms: These include biofertilization activities such as nitrogen fixation, solubilization of minerals like phosphorus, and production of plant hormones like auxins (e.g., IAA), cytokinins, and ACC-deaminase [4]. These processes directly provide essential nutrients and stimulate root and shoot development.

- Indirect Mechanisms: PGPR can reduce the detrimental effects of phytopathogens through induced systemic resistance (ISR) and the production of antimicrobial compounds, such as bacteriocins, chitinases, and other cell wall-degrading enzymes [4].

The diagram below illustrates the core signaling pathways and mechanisms through which PGPR interact with plants in the root zone.

Quantitative Effects of PGPR in Hydroponic Systems

The introduction of PGPR into hydroponic systems has demonstrated significant, measurable benefits across growth, yield, and quality parameters.

Impact on Growth, Yield, and Nutrient Uptake

A 2024 study on Batavia lettuce in a floating hydroponic culture demonstrated that PGPR can replace a significant portion of mineral fertilizers without compromising yield [6]. The study used a commercial PGPR product (Rhizofill) containing Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus megaterium, and Pseudomonas fluorescens [6].

Table 1: Impact of PGPR and Reduced Mineral Fertilizer on Lettuce Growth and Yield [6]

| Treatment | Plant Weight (g) | Leaf Area (cm²/plant) | Chlorophyll (SPAD) | Yield (kg/m²) | Nitrogen Uptake |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% MF (Control) | Data not specified | Data not specified | Data not specified | Data not specified | Data not specified |

| 80% MF + PGPR | No significant difference from control | Significant improvement | Significant improvement | No significant difference from control | Significant improvement |

| 60% MF + PGPR | Remarkable improvement | Remarkable improvement | Remarkable improvement | Remarkable improvement | Remarkable improvement |

| 40% MF + PGPR | Remarkable improvement | Remarkable improvement | Remarkable improvement | Remarkable improvement | Remarkable improvement |

| 20% MF + PGPR | Remarkable improvement | Remarkable improvement | Remarkable improvement | Remarkable improvement | Remarkable improvement |

Note: The original study [6] reported remarkable improvements in these parameters with PGPR application across reduced fertilizer treatments (20%, 40%, 60%, 80%) compared to non-inoculated controls at the same fertilizer levels. The combination of 80% MF + PGPR resulted in a yield statistically equivalent to the 100% MF control.

Impact on Nutritional and Phytochemical Quality

Beyond growth metrics, PGPR application enhances the nutritional quality of produce, a key consideration for food and pharmaceutical development.

Table 2: Effect of PGPR on Nutritional Quality Parameters in Hydroponic Lettuce [6]

| Parameter | Effect of PGPR Application |

|---|---|

| Essential Minerals | Improved concentrations in plant tissue |

| Phenols | Higher levels |

| Flavonoids | Higher levels |

| Vitamin C | Higher levels |

| Total Soluble Solids | Higher levels |

Experimental Protocols for Hydroponic PGPR Research

For researchers aiming to validate or build upon these findings, standardized protocols are essential. The following section details a methodology for establishing a hydroponic co-cultivation system.

Hydroponic Co-cultivation System for Plant-Microbe Interaction Studies

This protocol, adapted from a proven method, allows for the simultaneous and systematic investigation of signaling and responses in both plant hosts and interacting microbes without artificial induction [34].

System Overview: This inexpensive and flexible system supports intact plants with roots immersed in a hydroponic medium, which is then inoculated with bacteria. It maintains natural root structure and secretion, which is crucial for activating microbial chemotaxis and virulence [34].

Materials and Setup:

- Hydroponic Tank: A sterile container (e.g., a glass jar or specialized hydroponic tank) of appropriate size for the plant species.

- Metal Mesh Support: A metal mesh screen cut to fit the top of the tank. The mesh size should be chosen to support the plant's stem while allowing roots to penetrate freely.

- Growth Medium: A standard nutrient solution appropriate for the plant species (e.g., for Arabidopsis thaliana, a half-strength Murashige and Skoog basal salt mixture can be used).

- Aeration: Provided by gentle shaking on an orbital shaker platform or via a sterile air pump system.

Procedure:

- Plant Preparation: Surface-sterilize seeds and germinate on agar plates. Transplant seedlings onto the metal mesh support placed over the hydroponic tank containing the nutrient solution. Allow plants to acclimate and grow under controlled environmental conditions (light, temperature, humidity) suitable for the plant species.

- Bacterial Inoculum Preparation: Grow the PGPR strain of interest in a suitable liquid broth to the desired growth phase (e.g., mid-log phase). Centrifuge the bacterial culture and resuspend the pellet in a fresh, sterile nutrient solution to achieve the desired inoculum concentration (e.g., OD600 = 0.5).

- Co-cultivation: Inoculate the hydroponic medium in the tank with the prepared bacterial suspension. Ensure the root system is fully immersed.

- Monitoring and Control: Maintain the system without the addition of synthetic phytohormones or virulence-inducing chemicals. Monitor and adjust the pH and electrical conductivity (EC) of the nutrient solution regularly to maintain stable conditions.

- Sampling: At designated time points, separately harvest plant tissues (roots, shoots) and the bacterial cells from the medium for downstream "omics" analyses (e.g., transcriptomics, metabolomics).

The workflow for this experimental setup is visualized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of PGPR research in hydroponics requires specific, high-quality reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for PGPR Hydroponic Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| PGPR Strains | Core biofertilizer/biocontrol agents. | Commercial products (e.g., Rhizofill [6]) or defined strains from culture collections (e.g., Bacillus subtilis, Pseudomonas fluorescens [6] [20]). |

| Hydroponic Nutrient Solution | Provides essential macro/micronutrients. | Formulations must be precisely controlled (e.g., N, P, K, Ca, Mg, and micronutrients [6]). |

| Sterilizable Growth Tanks | Containment for hydroponic culture. | Material should be inert and easy to sterilize (e.g., glass, certain plastics). |

| Metal Mesh Supports | Physically supports plant, allows root access. | Mesh size must be appropriate for plant stem and root development [34]. |

| pH & EC Meters | Critical for monitoring and maintaining root zone chemistry. | Target pH 5.5-6.0 and EC 1.3-2.2 dS/m for many crops [6]. |

| Selective Media | For monitoring PGPR colonization and persistence. | Allows for the re-isolation and quantification of the inoculated PGPR strain from the root environment. |

The intentional introduction of PGPR into hydroponic root zones represents a frontier in sustainable soilless agriculture. By harnessing the power of microbial community interactions—mediated by root exudates, mVOCs, and rVOCs—researchers can develop systems that significantly reduce reliance on mineral fertilizers, enhance crop yield, and improve nutritional quality. The experimental data and protocols provided herein offer a foundation for further research. Future work should focus on elucidating the specific mVOCs responsible for observed growth promotions, optimizing PGPR consortia for specific crop-pathogen systems, and integrating these biological tools with smart sensor technologies for real-time management of the hydroponic rhizosphere. This approach is vital for addressing global challenges of food security and environmental sustainability.

Practical Implementation: PGPR Inoculation Strategies for Hydroponic Systems

Strain Selection Criteria for Hydroponic Compatibility and Efficacy

The integration of Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) into hydroponic systems represents a paradigm shift in soilless agriculture, offering a sustainable tool to enhance crop productivity while reducing chemical inputs [4]. Hydroponics, a method of growing plants without soil using mineral nutrient solutions, is gaining popularity among commercial farmers because it eliminates soil-borne problems [4]. The global hydroponic market is predicted to reach $16.6 billion by 2025, growing at a compound annual growth rate of 11.9% [4]. Despite the traditional approach of keeping these systems as clean as possible, a new trend is emerging: the intentional inclusion of beneficial microorganisms to enhance plant growth and stress resistance [4].

PGPR are rhizobacteria that colonize plant roots and enhance plant growth through direct and indirect mechanisms [4] [35]. In soilless environments, however, their application faces unique challenges compared to traditional soil systems. A critical knowledge gap exists regarding whether PGPR will adapt to a different environment from their natural habitat when used in this manner [4]. The successful implementation of PGPR in hydroponics therefore depends critically on selecting strains with specific traits that ensure compatibility and efficacy within these controlled environments. This guide establishes a scientific framework for strain selection, providing researchers with validated criteria and methodologies to advance this promising field.

Core Selection Criteria for Hydroponic Compatibility

Selecting PGPR strains for hydroponic systems requires evaluating specific traits that determine survival, colonization, and functionality in soilless environments. The following core criteria are essential for ensuring strain compatibility and efficacy.

Root Colonization Capacity