Genome-Wide Comparative Analysis of NBS Disease Resistance Genes Across 34 Plant Species: Evolution, Diversity, and Function

This article provides a comprehensive genomic analysis of Nucleotide-Binding Site (NBS) disease resistance genes across a broad phylogenetic spectrum of 34 plant species, from mosses to monocots and dicots.

Genome-Wide Comparative Analysis of NBS Disease Resistance Genes Across 34 Plant Species: Evolution, Diversity, and Function

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive genomic analysis of Nucleotide-Binding Site (NBS) disease resistance genes across a broad phylogenetic spectrum of 34 plant species, from mosses to monocots and dicots. We explore the extensive diversification of 12,820 identified NBS genes into 168 distinct structural classes, revealing both conserved and species-specific domain architectures. The study details the evolutionary mechanisms—including tandem and whole-genome duplications—driving NBS gene family expansion and contraction. It further integrates transcriptomic and functional validation data, demonstrating the critical role of specific NBS orthogroups in conferring resistance to biotic stresses like the cotton leaf curl disease. This synthesis offers invaluable insights for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to harness plant R-genes for crop improvement and biomedical applications.

Unveiling the Landscape: Diversity and Evolutionary History of NBS Resistance Genes in Land Plants

Nucleotide-binding site leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR) genes, also known as NLRs (NOD-like receptors), constitute the largest and most prominent class of plant disease resistance (R) genes. These genes encode intracellular immune receptors that enable plants to detect pathogen effectors and activate robust defense responses [1]. The proteins they encode are characterized by a conserved tripartite domain architecture: a variable amino-terminal domain, a central nucleotide-binding site (NBS) domain, and a carboxy-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain [2] [1]. To date, over 300 R genes have been cloned from various plant species, with approximately 60% belonging to the NBS-LRR family [3] [4]. These proteins function as essential components of the plant's effector-triggered immunity (ETI) system, recognizing specific pathogen effectors either directly or indirectly and initiating signaling cascades that often culminate in a hypersensitive response (HR) to restrict pathogen spread [5] [4]. The NBS-LRR gene family exhibits remarkable diversity and rapid evolution, making it a central focus of research in plant-pathogen interactions and disease resistance breeding.

Classification and Domain Architecture of NBS-LRR Genes

Major Subfamilies and Structural Features

NBS-LRR genes are primarily classified into distinct subfamilies based on their N-terminal domain configurations, which also correlate with specific signaling pathways [1]. The two major subfamilies are TIR-NBS-LRR (TNL) and CC-NBS-LRR (CNL), with an additional smaller subfamily known as RPW8-NBS-LRR (RNL) [6] [7].

- TNL Genes: Characterized by an N-terminal Toll/Interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain. These genes are prevalent in dicotyledonous plants but are completely absent from monocots, including cereals [7] [1] [5].

- CNL Genes: Feature a coiled-coil (CC) domain at the N-terminus. This subfamily is found in both monocots and dicots and represents the dominant type in many plant species [1].

- RNL Genes: Contain a Resistance to Powdery Mildew 8 (RPW8) domain and often function as helper proteins in signaling networks [6] [7].

In addition to these full-length genes, plant genomes contain numerous NBS-encoding genes that represent truncated forms, lacking one or more of the canonical domains (e.g., TIR-NBS, CC-NBS, or NBS-only proteins), which may function as adaptors or regulators [8] [1].

Table 1: Classification and Distribution of NBS-LRR Genes in Various Plant Species

| Plant Species | Total NBS Genes | TNL Genes | CNL Genes | Other/Truncated | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana (Dicot) | 189 [4] | Present [1] | Present [1] | 58 related proteins [1] | Model dicot with both TNL and CNL subfamilies. |

| Vernicia montana (Tung tree, Dicot) | 149 [8] | 3 TNL; 12 with TIR domain total [8] | 9 CNL; 98 with CC domain total [8] | Includes CC-NBS, TIR-NBS, NBS-LRR, NBS [8] | Resistant to Fusarium wilt; possesses TIR domains. |

| Vernicia fordii (Tung tree, Dicot) | 90 [8] | 0 [8] | 12 CNL; 49 with CC domain total [8] | Includes CC-NBS, NBS-LRR, NBS [8] | Susceptible to Fusarium wilt; lost TIR domains. |

| Nicotiana tabacum (Tobacco, Dicot) | 603 [9] | 64 TNL; 9 TIR-NBS [9] | 74 CNL; 150 CC-NBS [9] | 306 NBS-only [9] | Allotetraploid model for disease resistance studies. |

| Dendrobium officinale (Orchid, Monocot) | 74 [5] | 0 [5] | 10 CNL [5] | Various non-NBS-LRR types [5] | Represents monocots where TNL genes are absent. |

| Fragaria spp. (Strawberry, Dicot) | Varies by species [7] | Present, but proportion varies [7] | Present, >50% of NLRs [7] | RNL subfamily identified [7] | Non-TNLs show dominant expression and positive selection. |

Functional Domains and Their Roles

The modular structure of NBS-LRR proteins allows for specialized functions within the plant immune response:

- N-terminal Domain (TIR/CC/RPW8): Primarily involved in protein-protein interactions and initiating downstream signaling cascades. The TIR and CC domains define distinct signaling pathways [3] [1].

- Central NBS (NB-ARC) Domain: This domain contains conserved motifs (e.g., P-loop, Kinase-2, GLPL) that bind and hydrolyze ATP/GTP. It acts as a molecular switch, with nucleotide-dependent conformational changes regulating the protein's activation state [3] [1] [4].

- C-terminal LRR Domain: This domain is crucial for pathogen recognition specificity, facilitating both protein-ligand and protein-protein interactions. The LRR region is highly variable and often under diversifying selection, which generates diversity in pathogen effector recognition [8] [3] [1].

Genomic Distribution and Evolutionary Analysis Across Species

Variation in Gene Family Size and Evolutionary Patterns

Comparative genomics across a wide range of plant species has revealed that NBS-LRR genes constitute one of the largest and most variable gene families in plants [6] [1]. A comprehensive analysis of 34 plant species identified 12,820 NBS-domain-containing genes, which were classified into 168 distinct domain architecture classes, revealing significant diversity among species [6]. The size of the NBS-LRR repertoire varies dramatically, from as few as 2 genes in the lycophyte Selaginella moellendorffii to over 2,000 in hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum) [6] [9]. This expansion results primarily from duplication events, including whole-genome duplication (WGD) and small-scale duplications (SSD) such as tandem and segmental duplications [6] [9].

Table 2: Evolutionary Patterns and Selection Pressures on NBS-LRR Genes

| Evolutionary Aspect | Findings | Example Species/Study |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Family Size | Varies widely; one of the largest plant gene families. | 73 in Akebia trifoliata to 2151 in Triticum aestivum [9]. |

| Major Expansion Mechanism | Whole-genome duplication (WGD) and small-scale duplications (SSD). | WGD significantly contributed to expansion in Nicotiana tabacum [9]. |

| Genomic Organization | Frequently clustered in the genome. | 50.7% of cabbage NBS-LRR genes exist in 27 clusters [3]. |

| Selection Pressure | Generally under negative/purifying selection with positive selection on LRR. | Cabbage NBS-LRRs evolved under negative selection [3]. |

| Subfamily Evolution | Differential selection pressures on TNLs and non-TNLs (CNLs/RNLs). | In wild strawberries, non-TNLs show more positive selection [7]. |

| Domain Loss | Common evolutionary event, leading to truncated forms and new functions. | Genus Dendrobium shows NBS gene degeneration and type changing [5]. |

Chromosomal Distribution and Gene Clustering

NBS-LRR genes are frequently non-randomly distributed across plant genomes, often forming clusters on chromosomes. These clusters arise from both segmental and tandem duplication events [1]. For instance, in cabbage (Brassica oleracea), 50.7% of the 138 identified NBS-LRR genes are organized into 27 clusters, where a cluster is defined as two or more NBS-LRR genes located within 200 kilobases of each other and separated by no more than eight non-NBS genes [3]. Similar clustering patterns have been observed in diverse species, including strawberries and tobacco [7] [9]. This clustering facilitates the generation of new resistance specificities through unequal crossing-over and gene conversion, contributing to the evolutionary "arms race" between plants and their pathogens [1].

Experimental Protocols for Identification and Functional Characterization

Genome-Wide Identification Pipeline

The standard workflow for identifying NBS-LRR genes at a genome-wide scale relies on bioinformatic tools using conserved domain models.

Functional Validation Using Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS)

To confirm the function of identified NBS-LRR genes in disease resistance, functional assays are essential. Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS) has emerged as a powerful tool for this purpose.

- Objective: To rapidly validate the role of a candidate NBS-LRR gene in conferring resistance to a specific pathogen [8] [6].

- Procedure:

- A fragment (typically 200-500 bp) of the target NBS-LRR gene is cloned into a VIGS vector (e.g., TRV-based vector).

- The recombinant vector is introduced into plants of a resistant genotype via Agrobium tumefaciens-mediated infiltration.

- Control plants are infiltrated with an empty vector.

- After allowing 2-3 weeks for gene silencing to establish, plants are challenged with the target pathogen.

- Disease symptoms, pathogen biomass, and expression levels of the target gene are monitored in silenced versus control plants.

- Key Findings:

Signaling Pathways and Regulatory Mechanisms in Plant Immunity

NBS-LRR proteins are central components of Effector-Triggered Immunity (ETI). Their activation initiates complex signaling cascades that orchestrate the plant's defense.

Key Regulatory Mechanisms

- Transcriptional Regulation: The expression of NBS-LRR genes is modulated by transcription factors and hormonal signals. For example, Vm019719 in Vernicia montana is activated by the transcription factor VmWRKY64 [8]. Promoter analyses often reveal cis-elements responsive to salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid, and other stress signals [3] [4].

- Post-translational Regulation: Nitric Oxide (NO) has been identified as a key regulator of NBS-LRR activity. NO can mediate post-translational modification of these proteins through S-nitrosylation, influencing their function and the ensuing immune response [4]. Furthermore, certain NBS-LRR proteins are held in an auto-inhibited state in the absence of pathogens, with the NBS domain acting as a molecular switch that cycles between ADP-bound (inactive) and ATP-bound (active) states [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Resources for NBS-LRR Gene Research

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HMMER Suite | Bioinformatics identification of NBS domains using Hidden Markov Models. | Use Pfam model PF00931 (NB-ARC) with E-value cutoff < 1e-10 [8] [3]. |

| VIGS Vectors | Functional validation through transient gene silencing. | TRV-based vectors; effective in tung tree, cotton, tobacco [8] [6]. |

| RNA-seq Data | Expression profiling under biotic/abiotic stress and across tissues. | Key resources: IPF database, CottonFGD, NCBI SRA (e.g., SRP310543) [6] [9]. |

| Pathogen Strains | Biological assays for phenotyping resistance. | Fusarium oxysporum for wilt diseases, Botrytis cinerea for gray mold [8] [7]. |

| S-Nitrosocysteine (CysNO) | Chemical treatment to study Nitric Oxide (NO) signaling in immunity. | Used to infiltrate leaves (e.g., 1mM for 6h) to identify NO-responsive NBS-LRR genes [4]. |

Genome-Wide Identification of 12,820 NBS Genes Across 34 Species from Mosses to Higher Plants

This comparative guide presents a comprehensive analysis of nucleotide-binding site (NBS) domain genes across 34 plant species, from bryophytes to higher plants. The study identifies 12,820 NBS-domain-containing genes classified into 168 distinct architectural classes, revealing significant diversification in domain architecture patterns across evolutionary lineages. Evolutionary analysis identified 603 orthogroups with both core conserved and species-specific lineages, while expression profiling demonstrated the responsiveness of key orthogroups to biotic and abiotic stresses. Functional validation through virus-induced gene silencing established the role of specific NBS genes in viral disease resistance. This work provides an extensive framework for understanding the molecular evolution of plant immune system components and offers valuable data for crop improvement strategies.

Plant immunity relies on a sophisticated network of resistance (R) genes that recognize pathogen effectors and initiate defense responses. Among these, genes containing nucleotide-binding site (NBS) domains constitute one of the largest and most critical superfamilies involved in plant-pathogen interactions [6]. The NBS domain forms the core signaling module of nucleotide-binding site-leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR) proteins, which function as intracellular immune receptors in effector-triggered immunity (ETI) [9]. These proteins typically exhibit a modular architecture consisting of an N-terminal domain, a central NBS region, and C-terminal LRR domains, with classification into subfamilies (TNL, CNL, RNL) based on N-terminal domain variations [10].

Recent advances in sequencing technologies have enabled genome-wide identification of NBS-encoding genes across diverse plant taxa, revealing remarkable variation in family size and composition. While vertebrate genomes typically contain approximately 20 NLR genes, plant genomes can harbor hundreds to thousands of these genes [6]. This expansion is particularly pronounced in angiosperms, with bryophytes like Physcomitrella patens containing only around 25 NLRs compared to thousands in some flowering plants [6].

This study provides a systematic comparison of NBS genes across 34 species spanning the evolutionary spectrum from mosses to monocots and dicots. By integrating identification, classification, evolutionary analysis, and functional validation, we offer a comprehensive resource for understanding the diversification of plant immune receptors and their potential applications in crop protection.

Results

Genomic Distribution and Architectural Diversity of NBS Genes

Our genome-wide analysis identified 12,820 NBS-domain-containing genes across 34 plant species, representing a remarkable expansion compared to ancestral lineages [6]. The number of NBS genes varied substantially between species, reflecting differential evolutionary trajectories:

Table 1: NBS Gene Distribution Across Selected Plant Families

| Plant Family | Species | NBS Gene Count | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malvaceae | Gossypium hirsutum (cotton) | Part of 12,820 total | Multiple architectures |

| Solanaceae | Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco) | 603 | Allotetraploid expansion |

| Solanaceae | N. sylvestris | 344 | Diploid progenitor |

| Solanaceae | N. tomentosiformis | 279 | Diploid progenitor |

| Rosaceae | 12 species surveyed | 2,188 | Diverse evolutionary patterns |

| Passifloraceae | Passiflora edulis (purple) | 25 CNL genes | Stress-responsive members |

| Passifloraceae | P. edulis f. flavicarpa (yellow) | 21 CNL genes | Fewer CNLs than purple type |

| Lamiaceae | Salvia miltiorrhiza | 196 | Medicinal plant with reduced TNL/RNL |

| Asteraceae | Hirschfeldia incana | 98 NLR genes | Wild relative with R-gene potential |

Classification based on domain architecture revealed 168 distinct structural classes, encompassing both classical and novel configurations [6]. Beyond the well-characterized NBS, NBS-LRR, TIR-NBS, and TIR-NBS-LRR architectures, we identified several species-specific structural patterns including TIR-NBS-TIR-Cupin1-Cupin1, TIR-NBS-Prenyltransf, and Sugar_tr-NBS [6]. This architectural diversity suggests functional specialization and adaptive evolution in different plant lineages.

Evolutionary Analysis and Orthogroup Distribution

Phylogenetic analysis of NBS genes across the 34 species identified 603 orthogroups (OGs) with distinct evolutionary patterns [6]. These included:

- Core orthogroups: Widely distributed across multiple species (e.g., OG0, OG1, OG2)

- Unique orthogroups: Species-specific or limited to few species (e.g., OG80, OG82)

The expansion of NBS gene families primarily occurred through duplication events, with both whole-genome duplication (WGD) and small-scale duplications (SSD) contributing to family size variation [6]. In Nicotiana tabacum, approximately 76.62% of NBS genes could be traced to their parental genomes (N. sylvestris and N. tomentosiformis), with WGD significantly contributing to gene family expansion [9].

Evolutionary patterns varied substantially across plant families. In Rosaceae species, distinct evolutionary trajectories were observed: Rosa chinensis exhibited "continuous expansion," while Fragaria vesca showed "expansion followed by contraction, then further expansion," and three Prunus species shared "early sharp expansion to abrupt shrinking" patterns [11].

Expression Profiling Under Biotic and Abiotic Stresses

Expression analysis across multiple species and stress conditions revealed that specific NBS orthogroups display characteristic expression patterns:

Table 2: Expression Patterns of Key NBS Orthogroups Under Stress Conditions

| Orthogroup | Expression Pattern | Stress Conditions | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| OG2 | Upregulated in tolerant genotypes | Cotton leaf curl disease (CLCuD) | Putative role in virus resistance [6] |

| OG6 | Differential expression | Various biotic and abiotic stresses | Stress-responsive functions |

| OG15 | Tissue-specific regulation | Multiple stress conditions | Potential specialized roles |

| PeCNL3 | Differentially expressed | Cucumber mosaic virus, cold stress | Multi-stress responsiveness [12] |

| PeCNL13 | Responsive to pathogens | Cucumber mosaic virus infection | Disease resistance candidate |

| PeCNL14 | Cold and virus induction | Multiple stress conditions | Broad stress adaptation |

In passion fruit, transcriptome data identified PeCNL3, PeCNL13, and PeCNL14 as differentially expressed under both Cucumber mosaic virus infection and cold stress, suggesting their role in multiple stress response pathways [12]. Machine learning approaches further validated PeCNL3 as a multi-stress responsive gene [12].

Genetic Variation and Functional Validation

Genetic variation analysis between susceptible (Coker 312) and tolerant (Mac7) Gossypium hirsutum accessions identified substantial differences in NBS genes [6]. The tolerant Mac7 accession contained 6,583 unique variants in NBS genes, compared to 5,173 variants in the susceptible Coker312, suggesting potential functional significance in disease resistance.

Protein interaction studies demonstrated strong binding of specific NBS proteins with ADP/ATP and various core proteins of the cotton leaf curl disease virus [6]. Functional validation through virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) of GaNBS (OG2) in resistant cotton confirmed its essential role in limiting viral accumulation, providing direct evidence for its function in disease resistance [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Genome-Wide Identification of NBS Genes

The standard pipeline for genome-wide identification of NBS genes involves multiple bioinformatic approaches:

Protocol 1: Identification and Classification Pipeline

Data Collection: Genome assemblies and annotated protein sequences are obtained from public databases (NCBI, Phytozome, Plaza) [6]. The study analyzed 39 land plants ranging from green algae to higher plant families, selected based on phylogenetic diversity and ploidy level.

HMMER Search: The PfamScan.pl script with default e-value (1.1e-50) using the Pfam-A_hmm model is employed to identify genes containing NB-ARC domains [6] [9]. The hidden Markov model PF00931 (NB-ARC domain) serves as the primary search query.

Domain Validation: Candidate genes are verified using multiple domain databases (Pfam, SMART, CDD) to confirm the presence of characteristic NBS domains and associated decoy domains [12] [10]. The NCBI Conserved Domain Database is particularly valuable for this validation step.

Architecture Classification: Genes are classified based on domain composition using established classification systems [6]. Categories include:

- Classical architectures: NBS, NBS-LRR, TIR-NBS, TIR-NBS-LRR, CC-NBS, CC-NBS-LRR

- Species-specific patterns: TIR-NBS-TIR-Cupin1-Cupin1, TIR-NBS-Prenyltransf, Sugar_tr-NBS

Evolutionary and Phylogenetic Analysis

Protocol 2: Evolutionary Analysis Workflow

Orthogroup Delineation: OrthoFinder v2.5.1 with DIAMOND for sequence similarity searches and MCL clustering algorithm is used to identify orthogroups [6]. This approach facilitates the comparison of NBS genes across multiple species.

Multiple Sequence Alignment: MAFFT 7.0 or MUSCLE v3.8.31 performs alignment of NBS protein sequences under default parameters [6] [9]. For large datasets, ClustalW implemented in MEGA software provides an efficient alternative.

Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Maximum likelihood trees are constructed using FastTreeMP or MEGA11 with 1000 bootstrap replicates to assess node support [6] [9]. The Jones-Taylor-Thornton model is commonly employed for protein evolution.

Duplication Analysis: MCScanX detects segmental and tandem duplications across genomes, while Ka/Ks calculations identify selection pressures using KaKs_Calculator 2.0 [9].

Expression Analysis and Functional Validation

Protocol 3: Expression Profiling and Validation

Transcriptomic Data Collection: RNA-seq data are retrieved from specialized databases (IPF database, CottonFGD, Cottongen, NCBI SRA) and categorized into tissue-specific, abiotic stress-specific, and biotic stress-specific expression profiles [6].

Differential Expression Analysis: Processed RNA-seq data (FPKM or TPM values) are analyzed using appropriate pipelines. For novel data, tools like Hisat2 (alignment), Cufflinks (transcript quantification), and Cuffdiff (differential expression) are employed [9].

Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS):

- Target gene fragments (e.g., GaNBS from OG2) are cloned into VIGS vectors

- Recombinant vectors are introduced into plants through Agrobacterium-mediated infiltration

- Silenced plants are challenged with pathogens to assess functional roles

- Viral titers and disease symptoms are quantified to measure resistance [6]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Resources for NBS Gene Research

| Category | Specific Resource | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain Databases | Pfam (PF00931) | NBS domain identification | [6] |

| NCBI CDD | Domain verification | [9] | |

| InterPro | Integrated domain analysis | [12] | |

| Software Tools | OrthoFinder v2.5.1 | Orthogroup analysis | [6] |

| MCScanX | Duplication detection | [9] | |

| MEME Suite | Motif discovery | [11] | |

| MEGA11 | Phylogenetic analysis | [9] | |

| Biological Materials | Coker 312 (cotton) | Susceptible accession | [6] |

| Mac7 (cotton) | Tolerant accession | [6] | |

| N. bentoniana | VIGS validation | [6] | |

| Experimental Methods | VIGS system | Functional validation | [6] |

| RNA-seq libraries | Expression profiling | [6] | |

| Yeast two-hybrid | Protein interactions | [6] |

Discussion

Evolutionary Dynamics of NBS Genes

Our comparative analysis across 34 species reveals that NBS genes have undergone complex evolutionary patterns characterized by frequent gene duplication and loss events. The "birth-and-death" evolution model predominates, with gene duplication creating new resistance specificities and selective pressures driving diversification [13]. The significant variation in NBS gene number - from just 25 in the bryophyte Physcomitrella patens to thousands in some angiosperms - highlights the differential evolutionary trajectories across plant lineages [6].

Whole-genome duplication (WGD) plays a particularly important role in NBS gene family expansion, as evidenced by the allotetraploid Nicotiana tabacum, which contains approximately the combined NBS gene count of its diploid progenitors [9]. However, post-duplication processes, including fractionation and pseudogenization, subsequently shape the functional repertoire, leading to distinct evolutionary patterns even among closely related species.

Functional Implications for Crop Improvement

The identification of core orthogroups (OG0, OG1, OG2) conserved across multiple species suggests fundamental immune functions, while species-specific orthogroups may represent adaptations to particular pathogen pressures [6]. The genetic variation between susceptible and tolerant cotton accessions, with 6,583 unique NBS variants in the tolerant Mac7 compared to 5,173 in susceptible Coker312, provides valuable candidates for marker-assisted breeding [6].

Expression profiling under stress conditions further identifies promising candidates for crop improvement. The responsiveness of OG2, OG6, and OG15 to various biotic and abiotic stresses suggests their potential in developing climate-resilient crops with broad-spectrum resistance [6]. Similarly, in passion fruit, PeCNL3, PeCNL13, and PeCNL14 respond to both viral infection and cold stress, indicating their utility in multiple stress tolerance breeding programs [12].

Comparative Genomics Insights

The reduction or complete loss of specific NBS subfamilies in certain lineages provides insights into evolutionary constraints and functional redundancy. In monocots such as rice, wheat, and maize, complete absence of TNL genes contrasts with their prevalence in dicots, suggesting divergent evolutionary paths [10]. Similarly, Salvia miltiorrhiza shows marked reduction in TNL and RNL subfamily members compared to other eudicots [10].

Wild relatives of cultivated species often harbor greater NBS gene diversity, as demonstrated by Hirschfeldia incana, a wild Brassica relative containing 914 resistance gene analogs [14]. These wild germplasm resources represent valuable genetic reservoirs for improving disease resistance in related crops through breeding or biotechnological approaches.

This comprehensive analysis of 12,820 NBS genes across 34 plant species provides unprecedented insights into the evolution and diversification of plant immune receptors. The identification of 168 architectural classes reveals substantial structural diversity, while evolutionary analysis uncovers both conserved and lineage-specific patterns of gene family expansion and contraction.

Functional characterization demonstrates the importance of specific orthogroups in disease resistance, with practical applications for crop improvement. The integration of comparative genomics, expression profiling, and functional validation establishes a robust framework for future investigations of plant immunity mechanisms.

The resources and methodologies presented here will facilitate targeted breeding efforts and biotechnological approaches to enhance crop resilience in the face of evolving pathogen threats and changing environmental conditions. Future research should focus on functional characterization of specific NBS genes and their incorporation into breeding programs for sustainable agricultural production.

The nucleotide-binding site (NBS) domain genes represent a critical superfamily of resistance (R) genes that mediate plant defense mechanisms against pathogens [15]. This comprehensive analysis delves into the extensive diversification of these genes across the plant kingdom, identifying a remarkable 12,820 NBS-domain-containing genes across 34 plant species, spanning from primitive mosses to advanced monocots and dicots [15]. The central finding of this research is the classification of these genes into 168 distinct structural classes, revealing a vast architectural landscape that extends far beyond the classical TIR-NBS-LRR (TNL) and Coiled-Coil-NBS-LRR (CNL) models [15]. This classification provides an unprecedented resource for understanding plant immunity evolution and offers new genetic targets for crop improvement and drug discovery initiatives.

Comparative Genomic Analysis of NBS Domain Architectures

Methodology for Genome-Wide Identification and Classification

The identification and systematic classification of NBS genes followed a robust bioinformatics pipeline [15].

- Data Collection: Researchers selected 39 land plants representing diverse families (Amborellaceae, Brassicaceae, Poaceae, etc.) and ploidy levels (haploid, diploid, tetraploid). The latest genome assemblies were acquired from public databases like NCBI, Phytozome, and Plaza [15].

- Gene Identification: The PfamScan.pl HMM search script was employed to screen for genes containing the NBS (NB-ARC) domain, using a strict e-value cutoff of 1.1e-50. All genes possessing the NB-ARC domain were classified as NBS genes [15].

- Classification System: A domain architecture-based classification method was utilized, whereby genes sharing similar domain organization were grouped into the same class. This approach allowed for the discovery of both classical and species-specific novel structural patterns [15].

Spectrum of Classical and Novel Structural Classes

The study uncovered significant diversity in NBS gene architecture, which was categorized into 168 different classes. The table below summarizes the key types of domain architectures discovered.

Table 1: Classification of NBS Domain Architectures Across Plant Species

| Architecture Type | Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Classical | NBS, NBS-LRR, TIR-NBS, TIR-NBS-LRR | Well-characterized domain combinations forming the core of plant immune receptors. |

| Species-Specific Novel | TIR-NBS-TIR-Cupin1-Cupin1, TIR-NBS-Prenyltransf, Sugar_tr-NBS | Unusual domain fusions suggesting specialized functional adaptations in specific plant lineages. |

This diversification is driven by gene duplication events, including whole-genome duplication (WGD) and small-scale duplications (SSD) such as tandem, segmental, and transposon-mediated duplications [15]. The expansion of this gene family is particularly pronounced in flowering plants, contrasting with the small NLR repertoires found in ancestral lineages like bryophytes [15].

Orthogroup Analysis and Evolutionary Divergence

Orthogroup Clustering and Functional Conservation

To elucidate the evolution of NBS genes, researchers performed orthogroup (OG) analysis using OrthoFinder. This identified 603 orthogroups, which were categorized as [15]:

- Core Orthogroups: Widely conserved across multiple species (e.g., OG0, OG1, OG2).

- Unique Orthogroups: Highly specific to particular species (e.g., OG80, OG82).

Tandem duplications were a significant feature of these orthogroups, contributing to the rapid evolution and species-specific adaptation of the NBS gene repertoire [15].

Expression Profiling Under Biotic and Abiotic Stress

Transcriptomic analyses were conducted to link evolutionary conservation with functional relevance. Data from various RNA-seq databases revealed that specific orthogroups, including OG2, OG6, and OG15, were putatively upregulated across different plant tissues under diverse biotic and abiotic stresses [15]. This suggests that these core orthogroups play a fundamental role in plant stress responses. The analysis included studies on cotton leaf curl disease (CLCuD), comparing susceptible (Coker 312) and tolerant (Mac7) Gossypium hirsutum accessions [15].

Experimental Validation of NBS Gene Function

Genetic Variation and Protein Interaction Studies

A critical step in validating the functional importance of NBS genes involved analyzing genetic variation and molecular interactions.

- Variant Analysis: Comparison between susceptible (Coker 312) and tolerant (Mac7) cotton accessions identified a higher number of unique genetic variants in the NBS genes of the tolerant Mac7 line (6,583 variants) compared to the susceptible Coker 312 (5,173 variants) [15].

- Interaction Studies: Protein-ligand and protein-protein interaction experiments demonstrated strong binding between putative NBS proteins and ADP/ATP, as well as with core proteins of the cotton leaf curl disease virus. This indicates a direct mechanistic role for these NBS proteins in pathogen recognition and defense signaling [15].

Functional Characterization via Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS)

The role of a specific NBS gene, GaNBS (OG2), was functionally validated in resistant cotton using Virus-Induced Gene Silencing (VIGS). Silencing this gene compromised the plant's resistance, demonstrating its putative role in controlling viral titers [15]. This experiment provides direct evidence for the role of a specific NBS orthogroup in disease resistance.

Table 2: Experimental Findings from Functional Validation Studies

| Experimental Approach | Key Finding | Research Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Variant Analysis | 6,583 unique variants in tolerant Mac7 vs. 5,173 in susceptible Coker 312. | Suggests a genetic basis for disease tolerance linked to NBS gene diversity. |

| Protein Interaction | Strong NBS protein binding with ADP/ATP and viral proteins. | Indicates a direct role in pathogen sensing and energy-dependent defense signaling. |

| VIGS (GaNBS/OG2) | Increased viral titer after silencing confirmed gene's role in resistance. | Provides causal evidence for the function of a specific NBS orthogroup. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research in this field relies on a suite of specialized reagents and computational tools. The following table details key resources used in the featured genome-wide comparative study.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for NBS Gene Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application in NBS Gene Research |

|---|---|

| PfamScan.pl HMM Script | Identifies NBS (NB-ARC) domains in protein sequences with high specificity using hidden Markov models. |

| OrthoFinder Package | Clusters genes into orthogroups across species to infer evolutionary relationships. |

| MAFFT 7.0 | Performs multiple sequence alignments for phylogenetic analysis and domain comparison. |

| FastTreeMP | Constructs maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees to visualize gene family evolution. |

| RNA-seq Datasets (e.g., IPF Database) | Enables expression profiling of NBS genes across different tissues and stress conditions. |

| VIGS (Virus-Induced Gene Silencing) | A key functional genomics tool for validating the role of candidate NBS genes in plant immunity. |

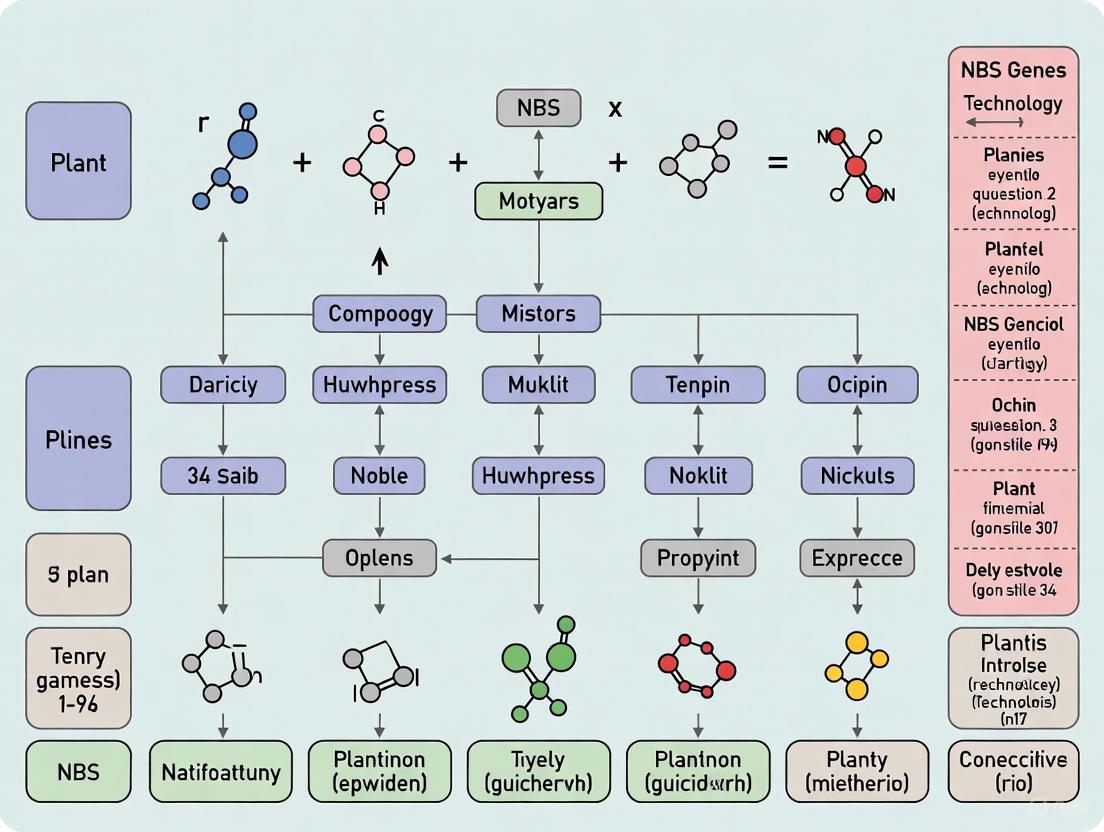

Visualizing the Research Workflow

The diagram below outlines the comprehensive experimental and computational workflow used to identify, classify, and validate NBS genes across plant species, from initial data collection to functional characterization.

This systematic comparison underscores the immense structural and functional diversity of NBS genes, encapsulated in the 168 distinct classes identified. The journey from classical TNL/CNL architectures to novel, species-specific domain combinations highlights a dynamic evolutionary landscape shaped by duplication events and natural selection. The integration of genomic, transcriptomic, and functional data—notably the validation of GaNBS (OG2) via VIGS—provides a robust framework for understanding the molecular basis of plant disease resistance. This research lays a solid foundation for future applications in developing disease-resistant crops and exploring novel protein architectures for therapeutic design.

Phylogenetic Distribution and Patterns of Gene Family Expansion in Diploid and Polyploid Species

Gene duplication serves as a fundamental evolutionary process that provides raw genetic material for the emergence of novel functions and adaptive complexity. The expansion and contraction of gene families across diploid and polyploid species represent dynamic genomic phenomena that reflect selective pressures and evolutionary trajectories [16]. Among the diverse gene families in plants, the nucleotide-binding site (NBS)-encoding gene family constitutes one of the largest and most critical classes of disease resistance (R) genes, playing pivotal roles in plant immunity through effector-triggered immunity (ETI) systems [17] [6]. The NBS gene family exhibits remarkable variation in size, composition, and evolutionary patterns across the plant kingdom, with recent research identifying 12,820 NBS-domain-containing genes across 34 species spanning from mosses to monocots and dicots [6].

The comparative analysis of gene family expansion in diploid and polyploid species provides crucial insights into evolutionary genomics, particularly regarding how genome duplication events influence genetic repertoire and functional diversification. This review synthesizes current understanding of phylogenetic distribution patterns, evolutionary dynamics, and experimental approaches for investigating gene family expansion, with specific emphasis on the NBS gene family across diverse plant lineages. Through systematic comparison of diploid and polyploid species, we aim to elucidate the complex interplay between genome duplication, selective pressures, and functional specialization that shapes gene family evolution.

Comparative Genomic Analysis of NBS Gene Family Across Species

Genomic Distribution and Architectural Diversity

The NBS gene family demonstrates extensive diversity in genomic organization and architectural composition across plant species. A comprehensive investigation across 34 land plant species identified 12,820 NBS-domain-containing genes classified into 168 distinct classes with numerous novel domain architecture patterns [6]. These encompass both classical structural patterns (NBS, NBS-LRR, TIR-NBS, TIR-NBS-LRR) and species-specific configurations (TIR-NBS-TIR-Cupin1-Cupin1, TIR-NBS-Prenyltransf, Sugar_tr-NBS), revealing significant diversity among plant species.

The chromosomal distribution of NBS genes frequently exhibits clustering patterns, as demonstrated in cassava (Manihot esculenta), where 63% of 327 identified R genes occurred in 39 clusters distributed across chromosomes [18]. These clusters are predominantly homogeneous, containing NBS-LRRs derived from recent common ancestors, which facilitates rapid evolution through recombination and birth-death dynamics. Similar clustering patterns have been observed across Rosaceae species, Asparagus species, and other plant lineages, suggesting conserved genomic organizational principles despite extensive sequence divergence [11] [19].

Table 1: NBS-LRR Gene Distribution Across Selected Plant Species

| Species | Genome Type | Total NBS Genes | CNL | TNL | RNL | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Diploid | 210 | 40 | 48 | 18 | [17] |

| Dendrobium officinale | Diploid | 74 | 10 | 0 | 9 | [17] |

| Akebia trifoliata | Diploid | 73 | 50 | 19 | 4 | [20] |

| Vernicia fordii | Diploid | 90 | 49* | 0 | - | [8] |

| Vernicia montana | Diploid | 149 | 98* | 12 | - | [8] |

| Asparagus officinalis | Diploid | 27 | - | - | - | [19] |

| Gossypium hirsutum | Allotetraploid | 2188 | - | - | - | [6] |

Note: Values for Vernicia species represent NBS with CC domains rather than full CNL; CNL=CC-NBS-LRR, TNL=TIR-NBS-LRR, RNL=RPW8-NBS-LRR

Evolutionary Dynamics in Diploid and Polyploid Species

Comparative analyses between diploid and polyploid species reveal complex evolutionary patterns in NBS gene family expansion. Research on Oryza, Glycine, and Gossypium genera demonstrated that NBS gene family sizes vary by several-fold, both among species and surprisingly within species [21]. This variation correlates with natural selection, artificial selection, and genome size variation, but interestingly, not primarily with polyploidization itself. The numbers of NBS genes in polyploid species often resemble those of one of their diploid donors, suggesting limited roles for polyploidization in driving NBS family expansion and indicating that organisms tend not to maintain surplus genes over evolutionary timescales [21].

The evolutionary patterns of NBS genes exhibit remarkable lineage-specific dynamics. In Rosaceae species, independent gene duplication and loss events have resulted in distinct evolutionary patterns: "first expansion and then contraction" in Rubus occidentalis, Potentilla micrantha, Fragaria iinumae and Gillenia trifoliata; "continuous expansion" in Rosa chinensis; and "expansion followed by contraction, then further expansion" in F. vesca [11]. Similarly, analysis of asparagus species (Asparagus officinalis, A. kiusianus, and A. setaceus) revealed significant contraction of NLR genes from wild species (63 in A. setaceus, 47 in A. kiusianus) to domesticated A. officinalis (27 genes), suggesting that artificial selection during domestication may reduce resistance gene diversity [19].

Phylogenetic Distribution and Gene Family Evolution

Phylogenetic Conservation and Divergence

The NBS gene family displays deep evolutionary conservation with recurring patterns of lineage-specific diversification. Reconciled phylogeny of Rosaceae species identified 102 ancestral NBS-LRR genes (7 RNLs, 26 TNLs, and 69 CNLs) that underwent independent duplication and loss events during species divergence [11]. Similarly, comparative analysis across orchid species (Dendrobium officinale, D. nobile, D. chrysotoxum) and related taxa revealed 655 NBS genes with notable absence of TNL-type genes in monocot lineages, indicating parallel degeneration patterns [17].

The phylogenetic distribution of NBS gene subfamilies reveals profound evolutionary constraints and innovations. Angiosperm genomes typically contain three NBS-LRR subfamilies: TNL (TIR-NBS-LRR), CNL (CC-NBS-LRR), and RNL (RPW8-NBS-LRR) [6] [11]. However, monocot species, including orchids and grasses, generally lack TNL genes, potentially due to NRG1/SAG101 pathway deficiency [17]. This phylogenetic distribution suggests subfunctionalization and distinct evolutionary trajectories between monocot and eudicot lineages.

Table 2: Evolutionary Patterns of NBS-LRR Genes Across Plant Families

| Plant Family | Representative Species | Evolutionary Pattern | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rosaceae | Rubus occidentalis, Potentilla micrantha | First expansion then contraction | Independent gene duplication/loss events |

| Rosaceae | Rosa chinensis | Continuous expansion | High duplication rate, positive selection |

| Rosaceae | Fragaria vesca | Expansion-contraction-further expansion | Fluctuating selection pressures |

| Fabaceae | Medicago truncatula, soybean | Consistent expansion | High tandem duplication rates |

| Poaceae | Rice, maize, Brachypodium | Contracting pattern | Predominant gene loss |

| Orchidaceae | Dendrobium species | Degeneration and diversity | NB-ARC domain degeneration, type changing |

| Asparagaceae | Asparagus officinalis | Domesticated contraction | Artificial selection, reduced diversity |

Mechanisms of Gene Family Expansion

Gene family expansion occurs through multiple mechanistic pathways, primarily classified as whole-genome duplication (WGD) and small-scale duplications (SSD), including tandem, segmental, and transposon-mediated events [16]. These mechanisms represent distinct modes of expansion, with gene families evolving through WGDs seldom undergoing SSD events, contributing to the maintenance of gene family expansion [6]. In Akebia trifoliata, tandem and dispersed duplications serve as the main forces responsible for NBS expansion, producing 33 and 29 genes respectively [20].

Following duplication, genes may be retained through several evolutionary models:

- Dosage balance model: Retention of duplicates maintaining stoichiometric balance in molecular interactions

- Subfunctionalization: Partitioning of ancestral functions between duplicates

- Neofunctionalization: Acquisition of novel beneficial functions by one duplicate

- Escape from adaptive conflict: Resolution of functional constraints through duplication

The probability of duplicate gene retention depends on gene duplicability, influenced by factors including protein structure, interaction networks, expression patterns, and functional constraints [16]. Genes with modular domain architectures and expression patterns are more amenable to subfunctionalization, while those with tight regulatory constraints or essential functions may be duplication-resistant.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Genome-Wide Identification of NBS Genes

Standardized pipelines have been established for comprehensive identification and classification of NBS genes across plant genomes. The typical workflow integrates multiple complementary approaches:

HMMER-based Domain Screening: Initial identification employs Hidden Markov Model searches using the conserved NB-ARC domain (Pfam: PF00931) as query with default e-value thresholds (1.0) [18] [20]. This is complemented by custom-built, lineage-specific HMM profiles refined from high-confidence domain alignments to enhance sensitivity.

BLAST-based Homology Searches: Parallel BLASTp analyses against reference NBS protein datasets from model organisms (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa) using stringent E-value cutoffs (1e-10) [19] [20]. This approach identifies divergent homologs that may escape domain-based detection.

Domain Architecture Validation: Candidate sequences undergo rigorous domain validation using InterProScan, NCBI's Conserved Domain Database, and Pfam scans to confirm NB-ARC domain presence (E-value ≤ 1e-5) and identify associated domains (TIR, CC, LRR, RPW8) [18] [19]. Coiled-coil domains require specialized prediction tools (e.g., Paircoil2) with position-specific scoring (P-score cut-off 0.03) due to limitations in conventional domain searches [18].

Classification and Subfamily Assignment: Validated NBS genes are classified into subfamilies (TNL, CNL, RNL) based on N-terminal domain composition and full-length architecture, with additional categorization of truncated variants (NL, CN, TN, RN, N) [8] [19].

Diagram 1: Workflow for NBS Gene Identification

Evolutionary and Phylogenetic Analysis

Orthogroup Analysis: OrthoFinder or similar tools cluster NBS sequences into orthogroups using sequence similarity searches (DIAMOND tool) and MCL clustering algorithm, enabling comparative analysis across species [6] [19]. This identifies core orthogroups conserved across taxa and lineage-specific expansions.

Phylogenetic Reconstruction: Multiple sequence alignment of NB-ARC domains or full-length proteins using MAFFT or Clustal Omega, followed by maximum-likelihood tree construction with tools like FastTreeMP or MEGA with 1000 bootstrap replicates [6] [18]. Reference sequences from model species provide phylogenetic framework.

Evolutionary Pattern Assessment: Reconciliation of gene trees with species trees identifies duplication and loss events, while synteny analysis (MCScanX) discerns WGD versus SSD origins [11]. Tests for selection pressures (dN/dS ratios) reveal signatures of positive or purifying selection.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for NBS Gene Family Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Databases | Phytozome, NCBI Genome, Plaza, Rosaceae Genome Database | Source of genome assemblies and annotations | Ensure consistent annotation versions for comparative analysis |

| Domain Databases | Pfam, InterPro, SMART, CDD | Identification and validation of protein domains | Use custom HMM profiles for lineage-specific domains |

| Sequence Analysis | HMMER v3, BLAST+, MAFFT, Clustal Omega | Sequence search, alignment, and analysis | Adjust e-value thresholds based on genome size and divergence |

| Phylogenetic Tools | OrthoFinder, MEGA, FastTreeMP, IQ-TREE | Orthogroup inference and tree building | Apply appropriate substitution models for NBS genes |

| Expression Databases | IPF Database, CottonFGD, NCBI SRA | Transcriptomic data for expression profiling | Normalize across experiments using standardized pipelines |

| Functional Validation | VIGS vectors, CRISPR-Cas9 systems, transgenic constructs | Functional characterization of candidate genes | Optimize delivery methods for specific plant species |

Signaling Pathways and Functional Mechanisms

NBS-LRR proteins function as central components of plant immune systems, recognizing pathogen effectors and initiating defense signaling cascades. The molecular architecture of canonical NBS-LRR proteins includes an N-terminal domain (TIR, CC, or RPW8), a central NB-ARC domain that functions as a molecular switch by binding and hydrolyzing nucleotides, and a C-terminal LRR domain involved in pathogen recognition and protein-protein interactions [17] [18].

Upon pathogen recognition, NBS-LRR proteins undergo conformational changes that activate downstream signaling pathways. TNL proteins typically activate signaling through EDS1-PAD4-ADR1 modules, while CNL proteins often utilize NDR1-helper complexes [11]. RNL proteins (NRG1 and ADR1 lineages) function as signal transducers downstream of both TNL and CNL activation, amplifying immune responses [20]. This coordinated signaling network culminates in the hypersensitive response, programmed cell death, and systemic acquired resistance.

Diagram 2: NBS-Mediated Immune Signaling Pathway

The phylogenetic distribution and expansion patterns of gene families in diploid and polyploid species reveal complex evolutionary dynamics shaped by both natural and artificial selection. The NBS gene family exemplifies these principles, demonstrating remarkable diversity in size, architecture, and evolutionary trajectory across plant lineages. Comparative genomic analyses consistently show that polyploidization alone does not determine gene family size; rather, lineage-specific duplication and loss events, selective pressures, and functional constraints interact to shape gene family evolution.

The integration of genomic, phylogenetic, and experimental approaches provides powerful frameworks for elucidating these evolutionary patterns. Standardized methodologies for gene family identification, classification, and functional characterization enable robust cross-species comparisons, while emerging technologies in genome editing and functional genomics facilitate direct testing of evolutionary hypotheses. Future research integrating population genomics, structural biology, and comparative phylogenomics will further illuminate the complex interplay between genome duplication, gene family expansion, and adaptive evolution across the diversity of plant lineages.

The Role of Whole-Genome and Tandem Duplications in NBS Gene Family Evolution

The nucleotide-binding site-leucine-rich repeat (NBS-LRR) gene family represents the largest class of plant disease resistance (R) genes, encoding proteins crucial for recognizing pathogens and initiating immune responses [6] [9]. The evolution of this gene family is characterized by remarkable dynamism, with gene numbers varying dramatically across plant species—from as few as 5 in some orchids to over 2,000 in wheat [6] [11]. This variation stems primarily from two evolutionary processes: whole-genome duplication (WGD) and tandem duplication [6] [9] [22]. Within the context of broader research comparing NBS genes across 34 plant species, this review examines how these duplication mechanisms have shaped the NBS gene family, driving both conservation and diversification in plant immune systems. Understanding these evolutionary patterns provides crucial insights for developing disease-resistant crops through targeted breeding strategies.

Quantitative Landscape of NBS Genes Across Plant Species

Comparative genomic analyses reveal striking disparities in NBS gene abundance across plant lineages. The following table summarizes the NBS gene counts and duplication patterns in various plant species:

Table 1: NBS Gene Distribution and Duplication Patterns in Plant Genomes

| Plant Species | Family | NBS Gene Count | Percentage of Genome | Main Duplication Type | Key Evolutionary Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apple (Malus domestica) | Rosaceae | 1,303 | 2.05% | Tandem & WGD | Extreme expansion [23] |

| Peach (Prunus persica) | Rosaceae | 437 | 1.52% | Tandem & WGD | Independent expansion [23] [11] |

| Pear (Pyrus bretschneideri) | Rosaceae | 617 | 1.44% | Tandem & WGD | "Early sharp expansion to abrupt shrinking" [11] |

| Tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) | Solanaceae | 603 | ~76.62% from parental genomes | WGD | Allotetraploid formation [9] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Brassicaceae | 149-166 | ~0.5% | Tandem & Segmental | Birth-and-death evolution [24] |

| Pepper (Capsicum annuum) | Solanaceae | 252 | Information missing | Tandem | 54% in clusters [25] |

| Grass Pea (Lathyrus sativus) | Fabaceae | 274 | Information missing | Information missing | 124 TNL, 150 CNL [26] |

| Cucumber (Cucumis sativus) | Cucurbitaceae | 59-71 | 0.19%-0.27% | Limited duplications | Gene loss dominance [23] |

| Akebia trifoliata | Lardizabalaceae | 73 | Information missing | Tandem & Dispersed | 50 CNL, 19 TNL, 4 RNL [20] |

The data reveal that Rosaceae species, particularly apple, have experienced extreme NBS gene expansion, while Cucurbitaceae species maintain remarkably low numbers. These differences reflect varying evolutionary pressures and duplication histories among plant families [23].

Table 2: NBS Gene Subfamily Distribution in Selected Species

| Species | TNL Count | CNL Count | RNL Count | Notable Subfamily Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akebia trifoliata | 19 | 50 | 4 | RNL present [20] |

| Grass Pea | 124 | 150 | Information missing | TNL dominance [26] |

| Pepper | 4 | 248 (total nTNL) | Information missing | Extreme nTNL bias [25] |

| Brassica napus | 461 | 180 | 0 | TNL dominance, no RNL [20] |

| Dioscorea rotundata | 0 | 166 | 1 | TNL absence [20] |

The distribution of NBS subfamilies (TNL, CNL, RNL) varies significantly across species, reflecting lineage-specific evolutionary paths. Notably, TNL genes are absent in monocots but present in many dicots, indicating potential specialization in pathogen recognition strategies [22] [25].

Experimental Methodologies for NBS Gene Identification and Evolutionary Analysis

Genomic Identification Protocols

Standardized protocols have emerged for genome-wide identification and evolutionary analysis of NBS genes. The following workflow illustrates the core experimental methodology:

Detailed Methodological Framework

Genome Assembly and Data Collection: Research begins with acquiring complete genome assemblies and annotated protein sequences from databases such as NCBI, Phytozome, Plaza, or specialized databases (BRAD for Brassica, Rosaceae.org for Rosaceae species) [6] [22]. Selection of species representing diverse evolutionary positions (from mosses to higher plants) and ploidy levels (haploid, diploid, tetraploid) enables comprehensive comparative analyses [6].

HMMER-Based Identification: The core identification step employs Hidden Markov Model (HMM) searches using the PF00931 (NB-ARC) profile from the Pfam database with trusted cutoff E-values (typically 1.1e-50) [6] [9]. This initial screen is followed by validation using NCBI's Conserved Domain Database (CDD) and additional domain predictors (Coiled-coil with threshold 0.5, PAIRCOIL2) to confirm domain architecture [9] [20].

Classification and Phylogenetics: Validated NBS genes are classified based on domain architecture into subfamilies (TNL, CNL, RNL, and variants). Multiple sequence alignment using MUSCLE or MAFFT precedes phylogenetic reconstruction with maximum likelihood methods (RAxML, FastTree) with bootstrap validation (typically 1000 replicates) [6] [26]. Orthogroup analysis using OrthoFinder with the MCL clustering algorithm identifies evolutionarily conserved groups across species [6].

Evolutionary History Reconstruction: Gene duplication events are detected using MCScanX with self-BLASTP parameters, identifying tandem, segmental, and WGD-derived genes [9]. Selection pressures are quantified by calculating non-synonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution rates using KaKs_Calculator with models such as Nei-Gojobori [9]. Gene clusters are defined as physical groupings of ≥2 NBS genes within 200kb [25].

Evolutionary Patterns and Duplication Mechanisms

Duplication Mechanisms Driving NBS Gene Expansion

The evolution of NBS genes is governed by three primary duplication mechanisms that create new genetic material for evolutionary innovation:

Whole-Genome Duplication (WGD): WGD events create complete sets of duplicated NBS genes, significantly expanding the gene family. In tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), an allotetraploid formed from hybridizing N. sylvestris and N. tomentosiformis, approximately 76.62% of its 603 NBS genes trace back to these parental genomes [9]. Similarly, the Brassica lineage, which experienced a whole-genome triplication event after diverging from Arabidopsis, shows complex patterns of NBS gene retention and loss [22].

Tandem Duplication: Tandem duplications occur when adjacent genes duplicate, creating gene clusters. In pepper, 54% of NBS genes (136 genes) form 47 physical clusters, with chromosome 3 containing the largest cluster of 8 genes [25]. These clusters often consist of phylogenetically related genes, suggesting recent expansions from common ancestors [24]. Tandem arrays facilitate the generation of sequence diversity through unequal crossing over and gene conversion [24].

Segmental and Ectopic Duplication: Segmental duplications copy entire chromosomal blocks, potentially distributing NBS genes to new genomic locations. Ectopic recombination between unlinked loci can create heterogeneous clusters containing genes from different phylogenetic clades, contributing to functional diversification [24].

Lineage-Specific Evolutionary Patterns

Different plant families exhibit distinct evolutionary patterns shaped by their duplication histories:

Rosaceae - Extreme Expansion: Rosaceae species display the most dramatic NBS gene expansions among documented plants. Apple contains 1,303 NBS genes (2.05% of its genome), the highest reported for any diploid plant [23]. Phylogenetic analyses reconstruct 102 ancestral NBS genes in Rosaceae (7 RNLs, 26 TNLs, and 69 CNLs), which underwent independent duplication and loss events in different lineages [11]. Maleae species (apple, pear) exhibit an "early sharp expanding to abrupt shrinking" pattern, while Rosa chinensis shows "continuous expansion" [11].

Cucurbitaceae - Gene Loss Dominance: In stark contrast to Rosaceae, Cucurbitaceae species maintain remarkably small NBS gene repertoires (cucumber: 59-71 genes; watermelon: 45 genes), representing only 0.19%-0.27% of their genomes [23]. This pattern reflects frequent gene losses and deficient duplications, suggesting alternative defense strategies may operate in these species [23] [11].

Solanaceae - Mixed Evolutionary Paths: Solanaceae species exhibit varied patterns. Pepper contains 252 NBS genes with strong nTNL dominance (248 nTNLs vs. 4 TNLs) [25], while tobacco has experienced significant expansion through WGD [9]. These differences reflect the family's diverse evolutionary history.

Research Reagent Solutions for NBS Gene Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for NBS Gene Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Primary Function | Application Examples | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| HMMER Suite | Hidden Markov Model searches | Domain identification (PF00931) | Statistical rigor for domain detection [6] [9] |

| Pfam Database | Protein family models | NB-ARC domain (PF00931), TIR, LRR domains | Curated multiple sequence alignments [9] [22] |

| OrthoFinder | Orthogroup inference | Evolutionary relationships across species | Algorithmic accuracy for orthogrouping [6] |

| MCScanX | Duplication pattern analysis | Tandem, segmental, WGD identification | Collinearity detection [9] |

| KaKs_Calculator | Selection pressure analysis | Ka/Ks ratio calculation | Evolutionary model flexibility [9] |

| MEME Suite | Motif discovery | Conserved NBS motif identification | Pattern recognition in sequences [11] [20] |

| RNA-Seq Data | Expression profiling | Differential expression under stress | Tissue-specific expression patterns [6] [26] |

| VIGS (Virus-Induced Gene Silencing) | Functional validation | Gene silencing in resistant plants | Rapid functional assessment [6] |

Functional and Evolutionary Implications of Duplication Patterns

Functional Diversification and Adaptive Evolution

The duplication mechanisms driving NBS gene expansion have profound functional implications for plant immunity:

Specificity Determinants: The LRR domains, which determine recognition specificity, exhibit the highest variability and experience positive selection, particularly in solvent-exposed residues [6] [25]. This diversification enables recognition of rapidly evolving pathogen effectors. In grass pea, 85% of identified NBS genes show expression under stress conditions, with specific genes upregulated under salt stress, suggesting roles beyond pathogen immunity [26].

Conserved Signaling Components: The NBS domain contains conserved motifs (P-loop, RNBS-A, kinase-2, RNBS-B, RNBS-C, and GLPL) essential for nucleotide binding and hydrolysis [25] [20]. These motifs maintain signaling function while recognition domains diversify. The TIR/CC domains mediate downstream signaling, with TIR domains generally activating EDS1-dependent pathways and CC domains often functioning through NRC helpers [6].

Expression Neofunctionalization: Duplicated NBS genes may undergo expression pattern divergence, partitioning ancestral functions or developing new regulatory responses. In Akebia trifoliata, most NBS genes show low expression, but a subset exhibits relatively high expression in rind tissues during later fruit development, suggesting specialized roles in fruit protection [20].

Evolutionary Dynamics and Selection Pressures

NBS genes evolve through a "birth-and-death" process where new genes are created by duplication, and existing genes are lost or pseudogenized [24]. This dynamic process generates considerable interspecies variation in NBS gene number and composition. Several factors influence this evolutionary trajectory:

Pathogen Pressure: Plants facing diverse pathogen communities maintain expanded NBS repertoires for broad-spectrum recognition. The extreme expansion in apple may reflect its long perennial lifecycle and exposure to numerous pathogens [23].

Genetic Trade-offs: Maintaining large NBS repertoires carries fitness costs, potentially explaining patterns of contraction in some lineages. MicroRNA-mediated regulation may help mitigate these costs, enabling plant species to maintain extensive NLR repertoires [6].

Genomic Context: NBS genes are frequently located in dynamic chromosomal regions with high recombination rates, facilitating their rapid evolution. In Akebia trifoliata, 64% of mapped NBS genes reside in clusters, predominantly at chromosome ends [20].

Whole-genome and tandem duplications have played complementary yet distinct roles in shaping the evolution of the NBS gene family across plant species. WGD events provide the raw genetic material for expansion, while tandem duplications and rearrangements drive functional diversification through novel combinations of protein domains. The extraordinary variation in NBS gene number and architecture among plants—from the massively expanded Rosaceae to the minimal Cucurbitaceae repertoires—demonstrates the dynamic nature of plant-pathogen coevolution. These evolutionary patterns reflect adaptive responses to diverse pathogen pressures, genomic constraints, and physiological trade-offs. Understanding these duplication mechanisms and their functional consequences provides crucial insights for developing disease-resistant crops through marker-assisted breeding or biotechnological approaches that harness the natural diversity of plant immune systems.

From Sequence to Function: Methodologies for Identifying, Classifying, and Profiling NBS Genes

Nucleotide-binding site (NBS) domain genes represent one of the largest and most critical gene families in plant innate immunity, encoding proteins that function as major immune receptors for effector-triggered immunity (ETI) [6]. The identification and comparative analysis of these genes across multiple species provide invaluable insights into plant adaptation mechanisms and resistance gene evolution [6]. The bioinformatic pipeline for NBS gene identification typically integrates three core tools: HMMER for domain detection, Pfam for domain annotation, and OrthoFinder for evolutionary classification. This guide provides an objective comparison of these tools' performance in large-scale comparative genomic studies, particularly within the context of a broader thesis analyzing NBS genes across 34 plant species [6].

Core Tool Functions in NBS Analysis Pipeline

- HMMER: Identifies protein domains within sequence data using Hidden Markov Models (HMMs). It is utilized for initial screening of sequences containing the NBS (NB-ARC) domain through hmmscan searches against the Pfam database [6] [27].

- Pfam: Provides the curated, multiple sequence alignments and HMMs for protein families and domains. The Pfam NBS (NB-ARC) domain (PF00931) serves as the reference model for identifying the core NBS domain in candidate resistance genes [27].

- OrthoFinder: Determines orthologous relationships among genes from multiple species. It clusters identified NBS-domain-containing genes into orthogroups (OGs) to infer evolutionary relationships and gene family expansion mechanisms [6].

Performance Metrics and Benchmarking

Benchmarking studies provide critical data on the accuracy and performance of orthology inference methods like those integrated in OrthoFinder. The following table summarizes OrthoFinder's performance on standard benchmark tests compared to other methods:

Table 1: Orthology Inference Accuracy Assessment on Quest for Orthologs Benchmark Tests

| Benchmark Test | Assessment Metric | OrthoFinder Performance | Performance vs. Competitors |

|---|---|---|---|

| SwissTree [28] | Precision, Recall, F-score | 3-24% higher F-score | More accurate than any other method tested |

| TreeFam-A [28] | Precision, Recall, F-score | 2-30% higher F-score | Most accurate method on this test |

| Orthobench [29] | Orthogroup Inference Accuracy | Successfully identified 603 NBS orthogroups across 34 species [6] | Extended and revised 44% of reference orthogroups (31 of 70) in benchmark |

Independent assessment using the Orthobench benchmark revealed that OrthoFinder provides high accuracy for orthogroup inference. A study leveraging OrthoFinder successfully identified 12,820 NBS-domain-containing genes across 34 plant species and classified them into 603 orthogroups, demonstrating its scalability and accuracy in handling large, complex gene families [6]. The same study highlighted OrthoFinder's utility in identifying core orthogroups (e.g., OG0, OG1, OG2) and species-specific orthogroups, facilitating the understanding of NBS gene diversification [6].

Experimental Protocols for NBS Gene Identification and Analysis

Standardized Workflow for Cross-Species NBS Gene Analysis

The following workflow is adapted from a published large-scale analysis of NBS genes across 34 plant species [6]. This protocol ensures comprehensive identification, classification, and evolutionary analysis of NBS-encoding genes.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NBS Gene Identification

| Reagent/Resource | Function in the Pipeline | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Pfam NBS HMM (PF00931) | Reference model for identifying the NB-ARC domain in protein sequences. | Used with HMMER's hmmscan for initial domain detection [27]. |

| Protein Sequence Files | Input data containing the predicted proteomes for the species under study. | Latest genome assemblies from Phytozome, NCBI, or Plaza [6]. |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment Tool | Aligns sequences for phylogenetic analysis within orthogroups. | MAFFT 7.0 with L-INS-i algorithm [29] [6]. |

| Phylogenetic Tree Tool | Infers evolutionary relationships within gene families. | IQ-TREE or FastTreeMP with best-fit model and bootstrap support [29] [6]. |

Phase 1: Data Collection and Preparation

- Genome Source: Obtain the latest genome assemblies and annotated protein sequences for all target species from public databases such as NCBI, Phytozome, or Plaza [6]. For the 34-species analysis, this included species from mosses to monocots and dicots, covering families like Brassicaceae, Poaceae, and Malvaceae [6].

- Data Formatting: Ensure all protein sequence files are in FASTA format and consistently annotated.

Phase 2: Identification of NBS Domain-Containing Genes

- HMMER Scan: Use the

hmmscanutility from the HMMER suite (e.g.,PfamScan.pl) to scan all predicted proteins against the Pfam NBS (NB-ARC) domain model (PF00931). A typical command uses a strict E-value cutoff (e.g., 1.1e-50) to minimize false positives [6]. - Initial Filtering: Extract all genes that contain the NBS domain based on the HMMER results. These genes form the initial candidate set for further analysis.

Phase 3: Domain Architecture Classification

- Additional Domain Detection: Use HMMER/Pfam to scan the candidate NBS genes for other associated domains such as TIR (PF01582), LRR (PF00560, PF07723, PF07725, PF12799), RPW8 (PF05659), and CC (using tools like Paircoil2) [27].

- Gene Classification: Classify the NBS genes into architectural classes (e.g., TIR-NBS-LRR, CC-NBS-LRR, NBS-LRR, NBS) based on their domain combinations [6].

Phase 4: Orthologous Group Inference with OrthoFinder

- Input Preparation: Provide the FASTA files of the identified NBS proteins from all studied species as input to OrthoFinder.

- Run OrthoFinder: Execute OrthoFinder (v2.5.1 or higher) with default parameters. The tool will perform an all-vs-all sequence similarity search (using DIAMOND by default), apply the MCL clustering algorithm, and infer orthogroups and gene trees [6].

- Output Analysis: The primary output of interest is the file containing the orthogroups. These groups represent sets of genes descended from a single ancestral gene in the last common ancestor of all species being analyzed.

Phase 5: Evolutionary and Functional Analysis

- Gene Tree Construction: For orthogroups of interest, infer more robust multiple sequence alignments (e.g., with MAFFT) and phylogenetic trees (e.g., with IQ-TREE) to understand within-group evolution [29].

- Expression and Selection Analysis: Integrate additional data like transcriptomic data to profile expression (e.g., FPKM values under stress conditions) and perform tests for positive selection to identify genes under evolutionary pressure [6].

Diagram 1: NBS Gene Analysis Workflow. The pipeline progresses from domain identification (green) through evolutionary clustering to functional validation (blue).

Comparative Analysis of Tool Performance and Integration

Interoperability and Data Flow

The strength of this bioinformatic pipeline lies in the seamless interoperability between HMMER, Pfam, and OrthoFinder. HMMER uses the Pfam NBS HMM to generate a high-confidence set of candidate genes. The output of this stage—a curated list of NBS proteins with their domain architectures—serves as the direct input for OrthoFinder. OrthoFinder then places these genes into an evolutionary context by clustering them into orthogroups, enabling cross-species comparisons [6]. This integrated approach was successfully used to discover core orthogroups (OG0, OG1, OG2) common across many species and unique orthogroups specific to certain lineages, providing insights into the evolution of plant immunity [6].

Addressing Technical Challenges in NBS Analysis

The combination of these tools effectively addresses several challenges specific to NBS gene analysis:

- Gene Duplication and Loss: NBS genes often undergo rapid evolution through duplication and loss. OrthoFinder's phylogenetic methodology is robust to these processes, helping to distinguish recent paralogs from true orthologs, which is critical for accurate comparative analysis [28] [30].

- Large Gene Families: NBS gene families can be very large (e.g., thousands of genes). The default version of OrthoFinder using DIAMOND for sequence search provides the speed and scalability needed to analyze these extensive datasets within a practical timeframe [28].

- Domain Diversity: NBS genes exhibit significant architectural diversity. The initial step using HMMER and Pfam to classify genes into TNL, CNL, and other subclasses provides a necessary structural framework for interpreting the subsequent orthogroup analysis [27].

The integrated use of HMMER, Pfam, and OrthoFinder establishes a robust and accurate bioinformatic pipeline for the identification and comparative analysis of NBS genes across multiple plant species. Benchmarking data confirms that OrthoFinder provides superior orthology inference accuracy, while the standardized protocol using HMMER with Pfam models ensures comprehensive domain detection. This pipeline has been successfully applied in large-scale studies, enabling researchers to identify evolutionarily conserved and lineage-specific NBS genes, understand the impact of gene duplication, and select candidates for functional validation, thereby advancing our understanding of plant immunity mechanisms.

Orthogroup analysis represents a foundational methodology in modern genomics, enabling researchers to trace evolutionary relationships across multiple species by identifying groups of genes descended from a single ancestral gene in a last common ancestor. This approach is particularly powerful for studying gene family evolution, as it delineates homologous genes into orthologs and paralogs, providing a framework for understanding functional diversification and conservation. Within the broader context of a thesis on the comparative analysis of Nucleotide-Binding Site (NBS) genes across 34 plant species, orthogroup definition serves as the critical first step for classifying the vast diversity of disease-resistance genes. The identification of 603 distinct orthogroups, encompassing both deeply conserved core genes and rapidly evolving species-specific clusters, offers an unprecedented opportunity to decipher the evolutionary mechanisms shaping plant immunity. This analysis provides a systematic comparison of orthogroup inference methodologies, delivering the quantitative data and experimental validation necessary for researchers investigating plant-pathogen interactions and their applications in drug development and crop engineering.

Quantitative Analysis of NBS Orthogroups Across Plant Species

Orthogroup Distribution and Classification

The comprehensive analysis of 12,820 NBS-domain-containing genes across 34 plant species revealed their organization into 603 orthogroups (OGs) with significant variation in conservation patterns and species distribution [6]. These orthogroups were classified into two primary categories based on their phylogenetic distribution and conservation patterns:

- Core Orthogroups: These represent evolutionarily conserved gene clusters present across multiple species with high sequence conservation. Notable examples include OG0, OG1, and OG2, which constitute the fundamental NBS gene repertoire across diverse plant lineages [6].

- Unique Orthogroups: These are species-specific gene clusters that exhibit restricted phylogenetic distribution, such as OG80 and OG82, which represent recent evolutionary innovations potentially contributing to species-specific adaptation to pathogens [6].

Table 1: Classification and Distribution of Select NBS Orthogroups

| Orthogroup ID | Classification | Species Distribution | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| OG0 | Core | Broad, multi-species | Most common NBS architecture; foundational disease resistance |

| OG1 | Core | Broad, multi-species | Conserved domain structure; present in ancestral lineages |

| OG2 | Core | Broad, multi-species | Upregulated in tolerant plants under biotic stress [6] |

| OG6 | Core | Broad, multi-species | Responsive to multiple stress conditions |

| OG15 | Core | Broad, multi-species | Differential expression across tissues and stresses |

| OG80 | Unique | Species-specific | Specialized function in specific plant lineages |

| OG82 | Unique | Species-specific | Recent evolutionary origin; potential novel resistance |

Structural Diversity and Domain Architecture

The 603 orthogroups encompassed remarkable structural diversity, with genes classified into 168 distinct classes based on domain architecture patterns [6]. This diversity includes: