Genome Editing in Plants: A Comprehensive Comparison of CRISPR-Cas9, TALEN, and ZFN Efficiency, Specificity, and Applications

This article provides a systematic analysis of the three major genome-editing platforms—ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas9—in plant systems.

Genome Editing in Plants: A Comprehensive Comparison of CRISPR-Cas9, TALEN, and ZFN Efficiency, Specificity, and Applications

Abstract

This article provides a systematic analysis of the three major genome-editing platforms—ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas9—in plant systems. Tailored for researchers and biotechnology professionals, it examines the foundational mechanisms, methodological applications, and optimization strategies for each tool. By synthesizing recent advancements and comparative data on editing efficiency, specificity, and versatility, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting the appropriate technology for specific plant genetic engineering projects, from crop improvement to metabolic pathway manipulation.

The Genome Editing Toolkit: Understanding ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR-Cas9 Core Mechanisms

Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) represent a foundational milestone in the history of programmable genome editing. As the first generation of artificial restriction enzymes, ZFNs demonstrated the profound feasibility of targeting specific DNA sequences within complex genomes to induce controlled modifications [1] [2]. These chimeric nucleases are engineered by fusing a custom-designed, sequence-specific zinc finger protein (ZFP) DNA-binding domain to the non-specific DNA-cleavage domain of the FokI restriction endonuclease [1] [3]. The core innovation of ZFN technology lies in its DNA recognition code: each individual zinc finger domain within a larger array recognizes and binds to a specific 3-base pair (bp) DNA triplet [1] [2]. By assembling an array of multiple fingers, researchers can create a highly specific DNA-binding domain capable of recognizing extended sequences, typically ranging from 9 to 18 bp per ZFN monomer [1]. Since a functional FokI cleavage domain must dimerize to become active, a pair of ZFNs is designed to bind opposite DNA strands at precisely spaced intervals, typically 5-7 bp apart, forcing the nuclease domains to dimerize and create a double-strand break (DSB) at the targeted genomic location [1] [3]. This break then stimulates the cell's innate DNA repair machinery—either error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) leading to gene knockouts, or homology-directed repair (HDR) for precise gene editing or insertion [3] [4]. This elegant mechanism established the fundamental paradigm of targeted nuclease-based genome editing that subsequent technologies would build upon.

The Triplet Recognition Code: Design, Assembly, and Specificity

The DNA-binding specificity of ZFNs is governed by the architecture of Cys2-His2 zinc finger proteins, one of the most common DNA-binding motifs in eukaryotes [2]. Each finger consists of approximately 30 amino acids folded into a conserved ββα configuration, with specific amino acids on the surface of the α-helix making sequence-specific contacts with three adjacent base pairs in the major groove of DNA [2]. The true power of this system emerges from the modular assembly of multiple fingers into a continuous array; a three-finger array recognizes a 9-bp sequence, a four-finger array a 12-bp sequence, and so forth [1]. This modularity theoretically allows for the targeting of any genomic sequence. However, a significant design challenge exists due to "context-dependent" effects, where the DNA-binding specificity of an individual finger can be influenced by its neighboring fingers, making simple modular assembly unreliable in some cases [1].

To overcome this limitation, several sophisticated protein engineering strategies have been developed for constructing high-affinity ZF arrays. Modular Assembly involves linking together pre-characterized zinc finger modules, each selected to bind a specific 3-bp triplet, from large combinatorial libraries [1] [2]. The OPEN (Oligomerized Pool Engineering) system, developed by the Zinc-Finger Consortium, employs a bacterial two-hybrid selection to identify optimal 3-finger arrays from randomized libraries, taking into account the context-dependence between fingers [1]. More advanced methods combine these approaches, using context-dependent pre-selected modules for assembly [2]. The ultimate specificity is achieved when two ZFN monomers bind adjacent sites, creating a combined recognition sequence of 18-36 bp, which is statistically unique even within large plant or mammalian genomes [2] [5]. This high specificity is a defining characteristic of ZFNs and a key factor in their continued use for therapeutic applications where off-target effects are a critical concern.

Table 1: Key Methods for Engineering Zinc Finger DNA-Binding Domains

| Method | Description | Key Advantage | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modular Assembly [1] [2] | Linking pre-selected fingers, each binding a 3-bp triplet, into a contiguous array. | Simplicity and straightforward design. | Can fail due to context-dependence between adjacent fingers. |

| OPEN (Oligomerized Pool Engineering) [1] | Selection of 3-finger arrays from randomized libraries using a bacterial two-hybrid system. | Accounts for context-dependence, leading to highly specific arrays. | More laborious and time-consuming than modular assembly. |

| Context-Dependent Modular Assembly [2] | Using libraries of two-finger modules pre-selected for optimized junction interactions. | Balances design simplicity with improved success rate. | Requires access to specialized, pre-validated two-finger modules. |

ZFNs in Plant Research: Applications and Methodologies

ZFN technology has been successfully applied to modify the genomes of a diverse range of plant species, including Arabidopsis, tobacco, soybean, and the complex hexaploid genome of bread wheat [1] [6] [3]. Its applications in plant biotechnology are extensive, enabling targeted mutagenesis for gene knockouts, precision gene editing through HDR to introduce agronomically valuable traits (e.g., herbicide tolerance), and even the deletion of large genomic segments [3] [4]. A critical supporting technology for plant genome editing is the ability to deliver ZFN constructs and, where applicable, donor DNA templates into plant cells, followed by the in vitro selection and regeneration of whole plants from successfully modified cells [3].

A standard experimental protocol for ZFN-mediated gene knockout in plants involves several key stages. First, Target Selection and ZFN Design is performed, identifying a 9-18 bp target site for each ZFN monomer within the gene of interest, ensuring they are spaced 5-7 bp apart on opposite strands. ZFNs are then designed using one of the engineering methods described in Table 1 [1] [3]. Next, Vector Construction is undertaken, where genes encoding the designed ZFN pair are cloned into plant transformation vectors, typically under the control of a constitutive or inducible plant promoter [3]. Plant Transformation follows, using established methods like Agrobacterium-mediated transformation or biolistics to introduce the ZFN-encoding vectors into plant cells [3]. After transformation, Regeneration and Selection occurs, where transformed tissues are cultured under selective conditions to regenerate whole plants. Finally, Molecular Analysis is conducted to confirm mutagenesis. This typically involves PCR amplification of the target locus from regenerated plants, followed by a surveyor nuclease assay to detect mismatches in heteroduplex DNA caused by NHEJ-induced indels, and ultimately, DNA sequencing to characterize the specific mutations [3].

Comparative Analysis of Genome Editing Technologies in Plants

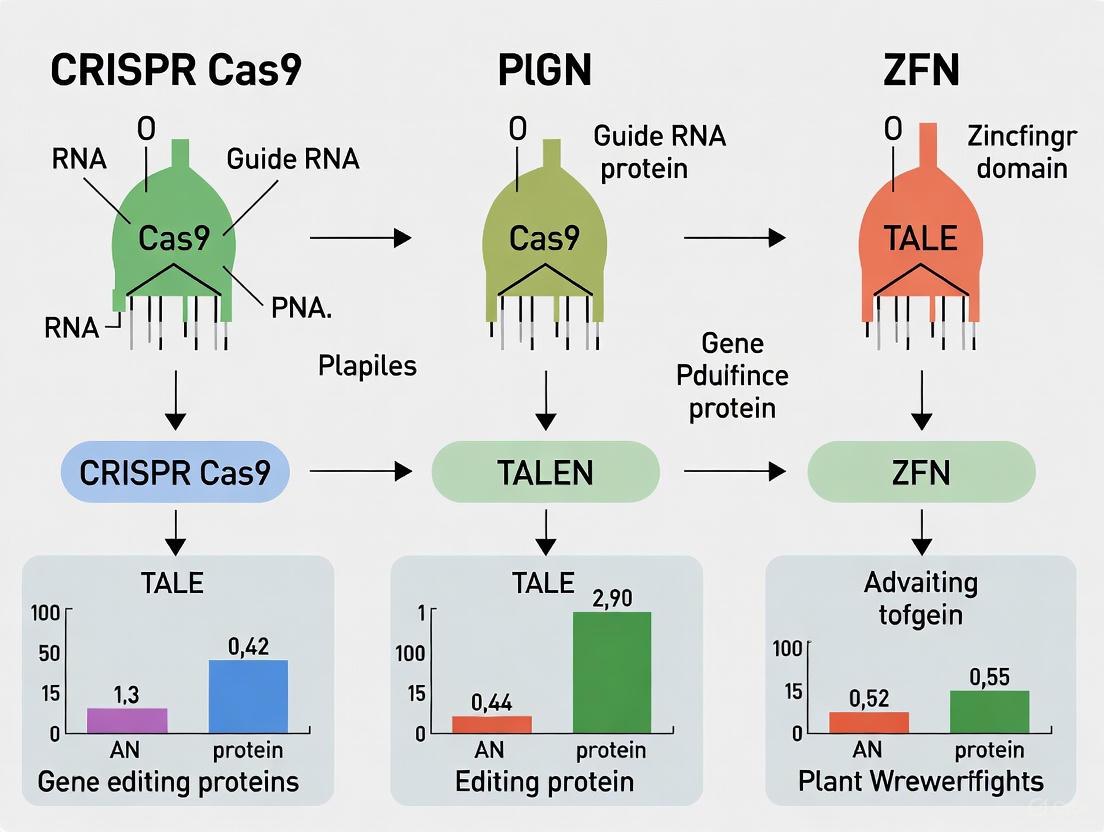

When evaluating the major genome editing platforms for plant research, ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR/Cas9 each present a distinct profile of advantages and limitations. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental structural and mechanistic differences between these three systems.

Diagram 1: A comparison of the core components and targeting mechanisms of ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR/Cas9. ZFNs and TALENs use programmable protein domains fused to FokI, while CRISPR/Cas9 uses a guide RNA to direct the Cas9 nuclease.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR/Cas9 for Plant Genome Editing

| Feature | Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) | TALENs | CRISPR/Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Recognition Molecule | Protein-based (Zinc Finger array) [1] | Protein-based (TALE repeats) [6] | RNA-based (Single guide RNA, sgRNA) [6] |

| Recognition Code | Triplet-based (Each finger ~3 bp) [1] [2] | Singlet-based (Each repeat 1 bp) [6] [2] | Linear RNA-DNA complementarity (sgRNA ~20 bp) [6] |

| Nuclease | FokI (requires dimerization) [1] [3] | FokI (requires dimerization) [6] [2] | Cas9 (functions as a monomer) [6] |

| Targeting Specificity | High (dimer target 18-36 bp) [2] [5] | High (dimer target 24-40 bp) [6] [2] | High (20 bp + PAM), but potential for more off-targets [6] |

| Ease of Design & Cloning | Complex and time-consuming due to context-dependence [1] [6] | Modular but repetitive, can be challenging to clone [6] [2] | Very simple; only the sgRNA needs to be redesigned [6] |

| Typical Development Time | Several months [6] | Several days to weeks [6] | A few days [6] |

| Key Limitation in Plants | High design complexity and cost; context-dependence [1] [6] | Large gene size complicates delivery; repetitive sequences [6] | Requires PAM sequence (e.g., NGG for SpCas9); most prominent off-target concerns [6] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for ZFN-Based Plant Genome Editing

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ZFN Experiments in Plants

| Reagent / Solution | Function and Role in ZFN Workflow |

|---|---|

| Custom ZFN Expression Vectors | Plasmids designed for plant expression, containing genes for the left and right ZFNs under the control of constitutive (e.g., 35S) or inducible promoters [3]. |

| Plant Transformation Vectors | Vectors such as pZFN1 and pZFN2 [5] for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation or biolistic delivery into plant cells. |

| Donor DNA Template | For HDR-mediated editing, a designed DNA fragment homologous to the target region, containing the desired modification (e.g., single nucleotide change or gene insertion) [3] [4]. |

| Cell Culture & Regeneration Media | Aseptic media formulations for the selection (e.g., using antibiotics), maintenance, and regeneration of transformed plant cells into whole plants [3]. |

| Surveyor Nuclease Assay Kit | A key validation tool used post-regeneration to detect NHEJ-induced mutations at the target locus by cleaving heteroduplex DNA [3]. |

| Pre-Engineered ZFN Libraries | Commercially available libraries of zinc finger modules or arrays (e.g., CompoZr from Sigma-Aldrich/Sangamo Biosciences) to bypass the need for de novo design [2]. |

ZFNs, with their foundational triplet recognition code, undeniably paved the way for the modern era of precision genome editing. While the advent of simpler, more user-friendly technologies like CRISPR/Cas9 has shifted the mainstream of plant biotechnology research, ZFNs retain significant relevance in specific applications [6] [5]. Their compact, all-protein structure is advantageous for viral delivery methods like AAV, and their long recognition site contributes to exceptionally high specificity, a critical factor for therapeutic development [5]. Furthermore, continuous innovation in ZFN architecture, such as the development of N-terminal FokI fusions and base-skipping linkers, has enhanced their targeting precision and versatility [5]. Therefore, while TALENs and CRISPR/Cas9 may offer greater ease of use and scalability for high-throughput plant functional genomics, ZFNs remain a powerful and sophisticated tool for researchers requiring the utmost precision in complex genomic engineering tasks, solidifying their enduring legacy as the pioneer technology that first demonstrated the feasibility of programmable genome editing.

Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) represent a groundbreaking advancement in the field of genome editing, distinguished by their unique modular architecture that enables precise single-base pair recognition [2] [7]. This technology has emerged as a powerful tool in plant research, offering distinct advantages for applications requiring high specificity and effectiveness in challenging genomic contexts [8]. As part of the broader genome editing toolkit that includes Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) and CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs occupy a specialized niche based on their protein-DNA binding mechanism and exceptional targeting precision [9].

The fundamental innovation of TALEN technology lies in its departure from triplet-based recognition systems like ZFNs toward a truly modular one-repeat-to-one-base pair recognition code [2] [10]. This simple yet powerful mechanism, combined with the nuclease capability of the FokI domain, enables researchers to induce targeted double-strand breaks at specific genomic locations across diverse plant species [8] [11]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of TALEN technology with other major genome editing platforms, focusing on its modular recognition system, experimental performance data in plant systems, and practical implementation protocols to guide researchers in selecting the appropriate technology for their specific applications.

Technology Comparison: Molecular Mechanisms and Recognition Codes

The TALEN Architecture: Modular DNA Recognition

TALENs are chimeric proteins composed of two primary functional domains: a customizable DNA-binding domain derived from transcription activator-like effectors (TALEs) and a catalytic domain from the FokI restriction endonuclease [7] [8]. The DNA-binding domain consists of tandem repeats of 33-35 amino acids, each recognizing a single DNA base pair through two hypervariable amino acid residues at positions 12 and 13, known as repeat-variable diresidues (RVDs) [2] [7]. This one-to-one recognition code provides the foundation for TALEN's precision and programmability, with specific RVD-base pair correspondences: NI for adenine (A), HD for cytosine (C), NG for thymine (T), and NN or NH for guanine (G) [7] [11].

The FokI nuclease domain functions as a molecular scissor that cleaves DNA, but it requires dimerization to become active [8]. This requirement means that a pair of TALEN proteins must bind to opposite DNA strands with a specific spacer sequence between their binding sites (typically 13-18 base pairs) to facilitate FokI dimerization and subsequent DNA cleavage [7]. This dimerization constraint enhances targeting specificity by reducing the likelihood of off-target activity, as two independent binding events must occur in precise orientation and proximity to generate a double-strand break [8].

Table 1: Repeat-Variable Diresidue (RVD) Codes for DNA Recognition

| RVD | Recognized Base Pair | Specificity Strength |

|---|---|---|

| NI | Adenine (A) | High specificity |

| HD | Cytosine (C) | High specificity |

| NG | Thymine (T) | High specificity |

| NN | Guanine (G) | Medium specificity |

| NH | Guanine (G) | High specificity |

Comparative Analysis of Genome Editing Platforms

When evaluated against other major genome editing technologies, TALENs demonstrate distinctive strengths and limitations. Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), the first generation of programmable nucleases, utilize zinc finger proteins that typically recognize 3-base pair triplets, making their design more complex due to context-dependent effects between neighboring fingers [2] [10]. CRISPR-Cas9 systems employ a RNA-guided DNA recognition mechanism where a single guide RNA (sgRNA) directs the Cas9 nuclease to complementary DNA sequences adjacent to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) [12] [9]. While CRISPR-Cas9 offers simpler design and higher throughput capabilities, its RNA-DNA hybridization mechanism can be more permissive than protein-DNA interactions, potentially resulting in higher off-target effects in certain genomic contexts [8] [13].

Table 2: Comprehensive Comparison of Major Genome Editing Technologies

| Feature | ZFN | TALEN | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Recognition | Protein-based (3 bp/finger) | Protein-based (1 bp/repeat) | RNA-guided (sgRNA) |

| Nuclease Domain | FokI | FokI | Cas9 |

| Target Specificity | High (with optimal design) | Very high | Moderate to high |

| Targeting Density | ~1 site every 200 bp [14] | Virtually any sequence | Requires PAM sequence |

| Design Complexity | High (context effects) [10] | Medium (modular assembly) | Low (guide RNA design) |

| Construction Time | Several weeks [14] | ~1 week [9] | Days |

| Typical Efficiency | Variable (10-50%) [10] | High (often >50%) [10] | Very high (often >70%) |

| Off-Target Effects | Lower than CRISPR [9] | Lowest among platforms [8] | Highest concern [12] |

| Heterochromatin Editing | Moderate | Excellent [13] | Limited [13] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Difficult | Challenging | Straightforward |

| Protein Size | Compact | Large | Large |

A critical differentiator for TALENs is their exceptional performance in heterochromatin regions. Single-molecule imaging studies have revealed that TALENs exhibit more efficient search behavior in constrained chromatin environments compared to CRISPR-Cas9 [13]. While Cas9 becomes encumbered by local searches on non-specific sites in heterochromatin, TALENs demonstrate superior navigation capabilities, resulting in up to fivefold higher editing efficiency in these challenging genomic regions [13].

Experimental Data and Performance Metrics in Plant Systems

Efficiency and Specificity Benchmarks

Comparative studies across various plant species have generated quantitative data demonstrating TALEN performance characteristics. In direct side-by-side comparisons with ZFNs, TALENs have shown substantially higher success rates in achieving targeted mutagenesis [10]. While early ZFN platforms often faced challenges with context-dependent failures, TALENs consistently achieved mutagenesis rates comparable to the most effective ZFNs but with significantly greater reliability [10]. This reliability stems from the more predictable and modular nature of the TALE DNA-binding code, which minimizes context effects that frequently hampered ZFN efficacy [2] [10].

When compared to CRISPR-Cas9 systems, TALENs generally exhibit lower off-target activity due to their longer recognition sequences and protein-DNA interaction mechanism [8] [9]. The requirement for dimerization of two TALEN subunits further enhances specificity by necessitating simultaneous binding at adjacent sites for DNA cleavage to occur [8]. This contrasts with CRISPR-Cas9 systems, where a single sgRNA guides the nuclease, and off-target effects can occur at sites with partial complementarity to the guide RNA, particularly in regions with high sequence similarity [12].

Applications in Plant Genome Engineering

TALEN technology has been successfully implemented in diverse plant species for both basic research and crop improvement applications. A prominent application involves the modification of metabolic pathways to enhance the production of valuable secondary metabolites in medicinal plants [8]. By targeting key genes in biosynthetic pathways for alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, and phenolic compounds, researchers have demonstrated the ability to significantly increase yields of these bioactive compounds through TALEN-mediated genome editing [8].

In crop species, TALENs have been effectively employed to improve agronomic traits such as disease resistance, stress tolerance, and nutritional quality [8]. The technology has proven particularly valuable for introducing precise genetic variations without the extensive crossbreeding required in traditional approaches, significantly accelerating the development of improved plant varieties [8]. The high specificity of TALENs minimizes unintended effects on non-target traits, making them especially suitable for precision breeding applications where maintaining elite genetic backgrounds is crucial.

Experimental Protocols: Implementation and Validation

TALEN Assembly and Delivery Methods

The construction of functional TALEN arrays has been streamlined through various modular assembly systems that facilitate the rapid generation of custom nucleases. Among these, the Golden Gate cloning system has emerged as a particularly efficient method, enabling the ordered assembly of multiple TALE repeat modules into backbone vectors in a single reaction [2]. More recently, high-throughput solid-phase assembly and ligation-independent cloning techniques have further simplified the process, making TALEN construction more accessible to non-specialist laboratories [2].

For plant applications, the Emerald-Gateway TALEN system represents an optimized platform that combines the efficiency of the Platinum Gate TALEN kit with Gateway recombination technology [11]. This system utilizes entry vectors (pPlat plasmids) containing cloning sites between Esp3I restriction sites within the DNA-binding domain region, enabling efficient assembly of custom TALEN arrays [11]. The resulting TALEN genes are then transferred into binary destination vectors (e.g., pDual35SGw1301) containing dual expression cassettes with cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoters for strong constitutive expression in plant cells [11].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for TALEN Implementation in Plants

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TALEN Assembly Kit | Modular construction of TALE repeat arrays | Platinum Gate TALEN kit provides pre-validated components [11] |

| Entry Vectors (pPlat) | Gateway-compatible vectors for TALEN gene construction | Contains cloning site between Esp3I sites [11] |

| Destination Vector | Binary vector for plant transformation | pDual35SGw1301 enables dual TALEN expression [11] |

| Esp3I Restriction Enzyme | Type IIS restriction enzyme for modular assembly | Enables seamless fusion of TALE repeat modules [11] |

| Single-Strand Annealing Reporter | Functional validation of TALEN activity | Luciferase-based system to quantify DNA cleavage efficiency [11] |

Validation and Functional Assessment

Rigorous validation of TALEN activity is essential before proceeding with plant transformation. The Single-Strand Annealing (SSA) assay coupled with luciferase reporter systems provides a robust method for quantitative assessment of DNA cleavage efficiency in bacterial systems [11]. This assay involves introducing target sequences into a divided luciferase gene vector and measuring the restoration of luciferase activity following TALEN-induced cleavage and recombination [11]. The Emerald-Gateway system has demonstrated high efficiency in such assays, with significant luciferase activity detected specifically when TALENs were matched with their corresponding target sequences [11].

Following validation, plant transformation is typically performed using Agrobacterium-mediated delivery of TALEN constructs [11]. Successful genome editing is confirmed through molecular analysis of transgenic lines, including PCR amplification of target regions and detection of modification events through restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis or sequencing [11]. Practical applications have demonstrated the efficacy of this approach, with documented cases of precise genome modifications in potato cells targeting the granule-bound starch synthase (GBSS) gene, resulting in specific mutations including nucleotide deletions, insertions, and substitutions [11].

Visualizing TALEN Architecture and Experimental Workflow

The following diagrams illustrate key concepts in TALEN technology and experimental implementation.

TALEN Modular Recognition Architecture

TALEN Implementation Workflow for Plants

TALEN technology represents a powerful genome editing platform with particular strengths in applications demanding high specificity and effectiveness in challenging genomic contexts. The modular single-base pair recognition mechanism provides unparalleled targeting precision, making TALENs especially valuable for plant research applications where minimizing off-target effects is paramount [8]. While CRISPR-Cas9 systems offer advantages in simplicity and multiplexing capacity, TALENs maintain a competitive edge in editing heterochromatin regions, targeting sequences with high GC content, and other challenging genomic contexts where RNA-guided systems may underperform [13].

For plant researchers, the choice between genome editing technologies should be guided by specific experimental requirements rather than presumed superiority of any single platform. TALENs represent an optimal choice for projects requiring: (1) maximal specificity with minimal off-target effects, (2) editing of heterochromatic regions, (3) modification of repetitive sequences or high-GC content targets, and (4) applications where the inherent protein-DNA recognition mechanism is advantageous [8] [13]. As the field of plant genome engineering continues to advance, TALEN technology remains an essential component of the molecular toolkit, particularly for precision breeding and metabolic engineering applications where its modular recognition system and high specificity deliver unmatched performance.

The advent of programmable nucleases has transformed genetic engineering, enabling precise, targeted modifications within complex genomes. Among these tools, Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) represented the first generation, followed by Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), with the more recent CRISPR-Cas9 system emerging as a groundbreaking technology [12]. While ZFNs and TALENs rely on custom-designed protein domains to recognize specific DNA sequences, CRISPR-Cas9 utilizes a guide RNA (gRNA) for target recognition, making it uniquely versatile and programmable [15]. This article provides a comparative analysis of these three genome-editing technologies, with a specific focus on their mechanisms, efficiencies, and applications in plant research, offering scientists a comprehensive guide for selecting the appropriate tool for their experimental needs.

Comparative Mechanisms of Action

CRISPR-Cas9: The RNA-Guided System

The CRISPR-Cas9 system consists of two fundamental components: the Cas9 nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA) [15]. The gRNA is a short RNA sequence engineered to be complementary to a target DNA locus. This RNA-guided complex scans the genome and induces a double-strand break (DSB) at the target site upon recognition [15]. The cell then repairs this break through one of two major pathways: the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), which often results in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt gene function, or the more precise homology-directed repair (HDR), which can be used to introduce specific changes using a donor DNA template [15].

TALENs: Modular Protein-Based Recognition

TALENs are fusion proteins consisting of a TALE DNA-binding domain derived from plant pathogenic bacteria and a FokI nuclease domain [8]. The DNA-binding domain is composed of tandem repeats, each recognizing a single specific nucleotide, allowing for the engineering of proteins that can bind to virtually any desired DNA sequence [8]. A critical feature of TALENs is that the FokI nuclease must dimerize to become active, meaning a pair of TALENs must bind to opposite DNA strands in close proximity to cleave the target site [8].

ZFNs: The Pioneer Technology

ZFNs, like TALENs, are chimeric proteins combining a zinc finger DNA-binding domain with the FokI nuclease domain [12]. Each zinc finger module typically recognizes a triplet of nucleotides, and multiple fingers are assembled to create a domain with specificity for a longer sequence. Similar to TALENs, ZFNs function as pairs, requiring dimerization of the FokI domains to create a DSB [12]. However, the design of zinc finger arrays with high specificity and affinity is technically challenging, as individual zinc fingers can exhibit context-dependent binding, making their development more complex than TALEN or CRISPR-Cas9 systems [12].

Comparative Efficiency and Performance in Plants

The following table summarizes key performance metrics of the three genome-editing technologies based on recent applications in plant systems.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Genome Editing Technologies in Plants

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 | TALENs | ZFNs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting Mechanism | RNA-guided (gRNA) [15] | Protein-DNA (TALE repeats) [8] | Protein-DNA (Zinc fingers) [12] |

| Ease of Design & Cloning | Rapid and simple (guide RNA design) [12] | Moderately complex (protein engineering) [12] | Complex (protein engineering with context dependence) [12] |

| Editing Efficiency in Plants | High (e.g., 94.6-100% in banana [16]; 18% in Fraxinus [17]) | High, with high specificity [8] | Variable, can be high if well-designed [12] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (multiple gRNAs easily expressed) [18] | Low to moderate [12] | Low [12] |

| Off-Target Effects | Moderate (potential with imperfect gRNA pairing) [12] | Low (high specificity of protein-DNA binding) [8] [12] | Moderate (can vary with design) [12] |

| Optimal Use Cases | High-throughput screening, multiplexed editing, rapid prototyping [19] [16] | Editing repetitive regions, high-GC content targets, applications requiring minimal off-targets [8] [12] | Established for specific, well-characterized targets [12] |

| Typical Mutation Pattern | Primarily small indels via NHEJ [15] | Primarily small indels via NHEJ [8] | Primarily small indels via NHEJ [12] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Data

Case Study 1: CRISPR-Cas9 in East African Highland Bananas

A 2025 study established an efficient CRISPR-Cas9 system for the triploid East African Highland banana (EAHB), a vital staple crop [16].

- Experimental Objective: To knockout the phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene as a visual marker to validate editing efficiency in two EAHB cultivars, Nakitembe (NKT) and NAROBan5 (M30) [16].

- Methodology:

- sgRNA Design: Two sgRNAs were designed targeting exons 5 and 6 of the Nakitembe PDS gene [16].

- Vector Construction: The sgRNAs were cloned into the pYPQ142 vector and recombined with a Cas9 entry vector and the pMDC32 binary vector to create the final construct, pMDC32Cas9NktPDS [16].

- Plant Transformation: Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain AGL1 harboring the construct was used to transform banana embryogenic cell suspensions (ECS). Transformed cells were regenerated on selective media [16].

- Key Results:

- A total of 47 NKT and 130 M30 independent events were regenerated [16].

- 100% of NKT and 94.6% of M30 edited events exhibited albinism (a clear phenotype of PDS knockout) [16].

- Sequencing confirmed frameshift mutations in the PDS gene of all edited plants, demonstrating the system's high efficiency and precision even in a triploid genome [16].

Case Study 2: CRISPR-Cas9 in Fraxinus mandshurica

Researchers developed a CRISPR-Cas9 system for Fraxinus mandshurica (Manchurian ash), a hardwood tree species lacking a mature tissue culture system [17].

- Experimental Objective: To establish a functional gene-editing system by knocking out the FmbHLH1 gene, a transcription factor involved in drought stress response [17].

- Methodology:

- Target Selection and Vector Construction: Three specific knockout targets for FmbHLH1 were selected and cloned into a CRISPR/Cas9 vector (pYLCRISPR/Cas9P35S-N) [17].

- Plant Transformation: The vector was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105. Sterile plantlets were infected via Agrobacterium-mediated transient transformation [17].

- Screening: A clustered bud system was used to induce and screen for homozygous edited plants [17].

- Key Results:

- Among 100 randomly transformed growing points, 18% of the induced clustered buds were successfully gene-edited, confirming the system's effectiveness in a recalcitrant species [17].

- Phenotypic analysis revealed that FmbHLH1 knockout plants had reduced drought tolerance, elucidating the gene's function [17].

Case Study 3: TALENs for Secondary Metabolite Engineering

TALENs have been effectively applied to enhance the production of valuable secondary metabolites in medicinal plants [8].

- Experimental Objective: To precisely manipulate genes in biosynthetic pathways for alkaloids, flavonoids, and terpenoids to increase their yield [8].

- Methodology:

- Key Results:

- TALENs have been used to create novel genetic variations that enhance the production of bioactive compounds without introducing foreign DNA, a significant advantage for consumer acceptance [8].

- The high specificity of TALENs minimizes off-target effects, which is crucial when engineering complex, interconnected metabolic pathways [8].

The workflow below generalizes the process of establishing a genome editing system in plants, as demonstrated in the case studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful genome editing requires a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Plant Genome Editing

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 Vector | Delivers the Cas9 nuclease and gRNA(s) into the plant cell. | pMDC32Cas9NktPDS vector used in banana editing [16]. |

| TALEN Pair | A pair of plasmids encoding the left and right TALEN proteins that dimerize to cleave the target DNA. | Custom TALEN pairs designed for biosynthetic pathway genes [8]. |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens Strain | A bacterium used as a vector to transfer T-DNA (containing the editing constructs) into the plant genome. | Strains AGL1 (banana) [16] and EHA105 (Fraxinus) [17] are commonly used. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | In CRISPR, a short RNA sequence that directs Cas9 to the specific genomic target. | Two sgRNAs designed from the Nakitembe PDS gene [16]. |

| Selection Agent (e.g., Kanamycin) | An antibiotic or herbicide added to growth media to select for plant cells that have successfully integrated the transformation vector. | Kanamycin used to select transformed Fraxinus embryos [17]. |

| Plant Tissue Culture Media | A nutrient medium supporting the growth and regeneration of whole plants from single cells or explants. | Woody Plant Medium (WPM) for Fraxinus [17]; specific media for banana ECS [16]. |

| PCR & Sequencing Primers | Oligonucleotides used to amplify and sequence the target locus to confirm successful editing. | Primers used for band-shift PCR and sequencing in banana study [16]. |

The choice between CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs, and ZFNs is not a matter of identifying a single "best" technology, but rather of selecting the most appropriate tool for a specific research context. CRISPR-Cas9 stands out for its unparalleled ease of design, high efficiency, and powerful multiplexing capabilities, making it the preferred choice for high-throughput functional genomics and rapid trait improvement in a wide range of plant species, from staples like banana to hardwoods like Fraxinus [17] [16]. In contrast, TALENs offer superior specificity with minimal off-target effects, proving highly valuable for applications requiring extreme precision, such as engineering complex secondary metabolite pathways or editing genomic regions with high sequence similarity [8] [12]. While ZFNs pioneered the field, their technical complexity and lower adoption have made them less common for new plant research projects [12].

The future of plant genome editing lies in the continued refinement of these tools. For CRISPR-Cas9, this includes the development of high-fidelity Cas variants, base editors, and prime editors that can make precise changes without creating double-strand breaks, thereby further reducing off-target potential [20] [15]. The integration of genome editing with other advanced technologies—such as multi-omics data analysis, artificial intelligence for improved gRNA and TALEN repeat design, and advanced tissue culture robotics—promises to accelerate the development of climate-resilient, high-yielding crop varieties [21]. As these technologies evolve and global regulatory frameworks adapt, programmable nucleases will undoubtedly play an increasingly critical role in ensuring future food security and advancing fundamental plant science.

Comparative Analysis of DNA Recognition and Binding Mechanisms

The advent of targeted genome editing has revolutionized biological research and therapeutic development. At the core of this revolution lie three powerful technologies: Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 system. Each platform employs fundamentally different mechanisms for DNA recognition and binding, which directly impacts their efficiency, specificity, and application potential. Understanding these molecular mechanisms is crucial for researchers selecting the appropriate tool for specific experimental or therapeutic goals. This comparative analysis examines the structural basis, operational mechanisms, and functional consequences of DNA recognition by these genome-editing platforms, with particular emphasis on their applications in plant systems. The fundamental differences in how these systems locate and bind their DNA targets ultimately determine their performance characteristics across various biological contexts.

Fundamental Protein-DNA Recognition Mechanisms

Before examining specific genome editing technologies, it is essential to understand the basic principles governing how proteins recognize and bind DNA. Protein-DNA recognition occurs through multiple mechanisms that can be categorized as direct readout (specific interactions with nucleotide bases) and indirect readout (recognition of DNA shape and structural properties) [22].

The primary molecular interactions facilitating protein-DNA binding include hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, hydrophobic effects, and van der Waals forces [23]. Hydrogen bonds form between protein functional groups and DNA bases or backbone atoms, with geometry affecting bond strength. Electrostatic interactions occur primarily between basic protein residues and the acidic DNA phosphate backbone. Hydrophobic effects drive the exclusion of water from interfaces, while van der Waals forces provide stabilizing contacts between complementary surfaces [23].

DNA-binding proteins typically employ structural motifs for DNA recognition. The helix-turn-helix (HTH) motif is common among prokaryotic and eukaryotic DNA-binding proteins, consisting of two nearly perpendicular α-helices connected by a short turn [24]. The second "recognition helix" inserts into the DNA major groove, where side chains contact nucleotide bases. Related winged helix-turn-helix variants incorporate additional structural elements that enhance DNA binding [24]. Understanding these fundamental mechanisms provides context for evaluating engineered DNA-binding platforms.

DNA Recognition Mechanisms by Editing Platforms

Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs)

Mechanism of DNA Recognition: ZFNs utilize engineered Cys2-His2 zinc finger proteins, one of the most common DNA-binding motifs in eukaryotes [2]. Each zinc finger domain consists of approximately 30 amino acids arranged in a ββα configuration that recognizes primarily three base pairs in the DNA major groove [2]. Multiple fingers are assembled in tandem (typically 3-6 fingers) to recognize extended DNA sequences of 9-18 base pairs, providing sufficient length for unique genomic targeting [2] [14].

Structural Basis: The modular structure of zinc finger proteins enables their engineering for specific DNA recognition. Successful targeting requires assembly of fingers that maintain specificity in extended arrays, which has been addressed through various strategies including modular assembly and selection-based approaches like OPEN (Oligomerized Pool Engineering) [2]. Each finger recognizes its triplet primarily through amino acid residues at key positions on the α-helical surface, with context-dependent interactions between neighboring fingers influencing binding affinity [2].

Nuclease Component: The DNA-binding domain is fused to the non-specific FokI endonuclease domain, which requires dimerization for activation. Thus, ZFNs function as pairs binding opposite DNA strands with appropriate spacing and orientation to allow FokI domains to dimerize and create double-strand breaks [14].

Table 1: ZFN Architecture and Properties

| Feature | Specification |

|---|---|

| DNA recognition domain | Engineered zinc finger arrays |

| Recognition unit size | ~3 bp per zinc finger |

| Typical total recognition length | 9-18 bp per ZFN monomer |

| Nuclease domain | FokI endonuclease |

| Binding requirement | Pair binding in opposite orientation with spacer |

| Engineering approach | Modular assembly, OPEN, or commercial sources |

Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs)

Mechanism of DNA Recognition: TALENs utilize DNA-binding domains derived from Transcription Activator-Like Effectors (TALEs), proteins naturally produced by Xanthomonas plant pathogens [2] [8]. The DNA-binding domain consists of tandem repeats of 33-35 amino acids, with each repeat recognizing a single base pair [2] [8]. This one-to-one correspondence between repeats and nucleotides simplifies target site prediction and engineering.

Repeat-Variable Diresidues (RVDs): Specificity is determined by two hypervariable amino acids at positions 12 and 13 within each repeat, known as Repeat-Variable Diresidues (RVDs) [2]. The RVD code defines base recognition: NI for adenine, NG for thymine, HD for cytosine, and NN for guanine/adenine [2] [8]. This simple cipher enables predictable engineering for novel DNA targets.

Structural Basis: TALE repeats assemble into a right-handed superhelical structure that wraps around the DNA major groove, with each RVD contacting its cognate base pair [2]. The modular nature of TALE repeats allows engineering of arrays capable of recognizing virtually any DNA sequence, with binding affinity generally increasing with repeat number.

Nuclease Component: Similar to ZFNs, TALENs fuse the TALE DNA-binding domain to the FokI nuclease domain, requiring paired binding with proper spacing for dimerization and DNA cleavage [8].

Table 2: TALEN Architecture and Properties

| Feature | Specification |

|---|---|

| DNA recognition domain | TALE repeat arrays |

| Recognition unit size | 1 bp per TALE repeat |

| Typical total recognition length | 12-20 bp per TALEN monomer |

| Specificity determinant | Repeat-Variable Diresidues (RVDs) |

| Key RVD specificities | NI→A, NG→T, HD→C, NN→G/A |

| Nuclease domain | FokI endonuclease |

| Engineering advantage | Simple cipher, high success rate |

CRISPR-Cas9 System

Mechanism of DNA Recognition: The CRISPR-Cas9 system employs a fundamentally different recognition mechanism based on RNA-DNA complementarity rather than protein-DNA interactions [25]. The Cas9 nuclease is directed to target sites by a guide RNA (gRNA) of approximately 20 nucleotides that forms complementary base pairs with the target DNA sequence [26] [25].

Structural Basis: Cas9 undergoes conformational changes upon gRNA binding, creating a channel that accommodates the RNA-DNA heteroduplex. The recognition (REC) lobe contains domains that facilitate binding to the gRNA-DNA complex, while the nuclease (NUC) lobe contains the HNH and RuvC catalytic domains [25]. The HNH domain cleaves the complementary DNA strand, while the RuvC domain cleaves the non-complementary strand [25].

PAM Requirement: Cas9 requires a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) adjacent to the target sequence for recognition and cleavage [26]. For the most commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where N is any nucleotide [25]. The PAM requirement restricts potential target sites but provides a safeguard against self-targeting of the bacterial CRISPR locus.

Table 3: CRISPR-Cas9 Architecture and Properties

| Feature | Specification |

|---|---|

| DNA recognition domain | RNA-guided (gRNA:DNA complementarity) |

| Recognition unit size | 20 nt guide sequence |

| Total recognition length | 20 bp + PAM |

| Specificity determinant | RNA-DNA base pairing |

| Nuclease domain | HNH and RuvC in Cas9 |

| Additional requirement | Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) |

| Engineering advantage | Simple gRNA design, multiplexing capability |

Comparative Analysis of Recognition and Binding Properties

Specificity and Off-Target Effects

ZFNs demonstrate moderate specificity, with off-target effects resulting from binding to sequences similar to the intended target. The challenge of engineering zinc finger arrays with high specificity, particularly due to context-dependent effects between adjacent fingers, can limit targeting density [14]. Studies in human stem cells have identified off-target mutations at sites with high sequence similarity to the target [14]. Specificity can be improved using obligate heterodimer FokI variants that prevent homodimer formation [14].

TALENs generally exhibit high specificity due to the precise one-to-one recognition code and the requirement for longer binding sequences. The protein-DNA interaction is highly specific, with reduced off-target effects compared to ZFNs and CRISPR-Cas9 in some studies [8]. The requirement for TALE repeats to begin with thymine (recognized by a truncated N-terminal domain) further constrains targetable sites [2].

CRISPR-Cas9 has raised concerns about off-target effects due to tolerance of mismatches, particularly in the PAM-distal region of the guide sequence [26] [25]. Off-target activity can occur at sites with up to 5 nucleotide mismatches, depending on their position and distribution [26]. However, high-fidelity Cas9 variants, truncated gRNAs, and improved design algorithms have significantly reduced off-target effects in recent implementations.

Efficiency and Practical Implementation

ZFNs were the first engineered nucleases to demonstrate efficient genome editing but present practical challenges in engineering. Publicly available platforms like OPEN address context dependence but require screening efforts, while commercial sources provide validated ZFNs but at higher cost [14]. Effective ZFN pairs can achieve mutation efficiencies of 1-50% in various cell types.

TALENs are considerably easier to design than ZFNs due to the simple RVD code, contributing to their rapid adoption. Golden Gate cloning and other modular assembly methods enable construction of custom TALEN arrays within days [2] [25]. TALENs typically show high activity across diverse target sites, with reported mutation efficiencies often exceeding those of ZFNs in side-by-side comparisons.

CRISPR-Cas9 offers the simplest design process, requiring only the synthesis of a ~20 nt guide RNA sequence to target new sites [25]. This simplicity enables rapid prototyping and multiplexing of targets. CRISPR-Cas9 generally demonstrates high efficiency across diverse organisms and cell types, though efficiency varies with gRNA sequence, chromatin accessibility, and cell division state.

Table 4: Comprehensive Comparison of Genome Editing Platforms

| Property | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition mechanism | Protein-DNA (zinc fingers) | Protein-DNA (TALE repeats) | RNA-DNA (gRNA complementarity) |

| Targeting length | 9-18 bp per monomer | 12-20 bp per monomer | 20 bp + PAM |

| Engineering difficulty | High (context dependence) | Moderate (repeat assembly) | Low (gRNA design) |

| Targeting density | ~1 site/200 bp (open source) | ~1 site/1-2 bp | ~1 site/8 bp (NGG PAM) |

| Mutation efficiency | Variable (1-50%) | Generally high | Generally high |

| Off-target concerns | Moderate | Low | Moderate to high |

| Multiplexing capability | Difficult | Difficult | Straightforward |

| Typical delivery | DNA/mRNA | DNA/mRNA | DNA/RNA/protein |

| Commercial availability | Limited (CompoZr) | Various sources | Widely available |

Applications in Plant Research

Plant genome editing presents unique challenges including cell wall barriers, transformation efficiency, and regenerative capacity. All three platforms have been successfully implemented in diverse plant species, with distinct advantages for specific applications.

ZFNs in Plants: ZFNs demonstrated early success in plant genome editing, with applications in targeted gene mutagenesis in Arabidopsis, tobacco, and maize [25]. The relatively small size of ZFN constructs compared to TALENs facilitates delivery via plant transformation methods. However, the engineering challenges have limited widespread adoption in the plant research community.

TALENs in Plants: TALENs have been successfully applied in over 50 plant genes across species including Arabidopsis, barley, Brachypodium, maize, tobacco, rice, soybean, tomato, and wheat [25]. Optimized TALEN scaffolds have been developed for high activity in plants [25]. Notable applications include engineering disease resistance in rice by modifying promoter elements of susceptibility genes [25] and creating powdery mildew-resistant wheat by targeting MLO genes [25]. The high specificity of TALENs is particularly valuable for applications in polyploid plants where precise targeting of homologous genes is required.

CRISPR-Cas9 in Plants: The simplicity of CRISPR-Cas9 has made it the most widely adopted platform for plant genome editing. It has been used for targeted gene mutagenesis, multiplexed editing, gene regulation, and base editing in numerous crop species [26] [25]. In rice, CRISPR-Cas9 has achieved mutation efficiencies of 3-8% in transformed cells [26]. The ability to simultaneously target multiple genes is particularly valuable for studying gene families and engineering complex traits in plants.

Experimental Considerations and Methodologies

Design and Assembly Protocols

ZFN Engineering: The OPEN (Oligomerized Pool Engineering) platform involves identifying potential zinc finger arrays through screening of randomized libraries that account for context-dependent interactions [2]. Alternatively, modular assembly approaches utilize pre-characterized zinc finger modules, though these may suffer from reduced activity due to context effects [2]. ZFN pairs must be designed to bind opposite DNA strands with 5-7 bp spacing for proper FokI dimerization.

TALEN Assembly: Golden Gate cloning is the most common assembly method, utilizing type IIS restriction enzymes to sequentially ligate TALE repeat modules [2] [25]. Other methods include high-throughput solid-phase assembly and ligation-independent cloning techniques [2]. TALEN pairs typically require 14-20 bp binding sites per monomer with 12-20 bp spacing.

CRISPR-Cas9 Design: gRNA design involves selecting 20 nt sequences adjacent to PAM sites (5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9) with minimal off-target potential. Numerous computational tools are available for gRNA design, which consider factors like GC content, specific nucleotide positions, and genome-wide off-target sites [25]. Modified gRNA architectures including truncated gRNAs and extended gRNAs can enhance specificity.

Delivery Methods in Plant Systems

DNA Delivery: All three platforms are typically delivered as DNA constructs via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation or biolistics. For ZFNs and TALENs, mRNA delivery can reduce off-target effects and persistent nuclease expression [14]. CRISPR-Cas9 can be delivered as DNA, RNA, or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes.

RNP Delivery: Direct delivery of preassembled Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoproteins has gained popularity for plant genome editing due to reduced off-target effects and transient activity [25]. RNPs can be delivered via biolistics or protoplast transfection, enabling editing without integration of foreign DNA.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Genome Editing Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclease platforms | ZFN pairs, TALEN pairs, SpCas9 variants | Core editing machinery for DSB induction |

| Assembly systems | Golden Gate TALEN kits, CRISPR gRNA cloning vectors | Modular construction of custom editors |

| Delivery vehicles | Agrobacterium strains, biolistic equipment, transfection reagents | Introduction of editing components into cells |

| Detection assays | T7E1 assay, SURVEYOR assay, deep sequencing | Validation of editing efficiency and specificity |

| Selection markers | Antibiotic resistance, fluorescent proteins, metabolic markers | Enrichment for successfully edited cells |

| Reporter systems | GFP reconstitution, luciferase assays | Rapid assessment of editing activity |

| Cell culture reagents | Plant growth media, hormones, protoplast isolation kits | Maintenance and transformation of plant cells |

The comparative analysis of DNA recognition and binding mechanisms reveals a clear evolution from protein-based recognition (ZFNs, TALENs) to RNA-guided systems (CRISPR-Cas9). Each platform offers distinct advantages: ZFNs as pioneering tools with moderate size, TALENs for high-precision applications with minimal off-target effects, and CRISPR-Cas9 for unparalleled simplicity and multiplexing capability. In plant research, all three platforms have demonstrated success, with choice depending on specific requirements for precision, efficiency, and regulatory considerations. The continued refinement of these technologies, including the development of high-fidelity variants and expanded targeting capabilities, promises to further enhance their utility for both basic research and agricultural biotechnology. As the field advances, the optimal application of each technology will increasingly depend on matching their inherent recognition and binding properties to the specific biological context and editing objectives.

The Critical Role of Double-Strand Breaks and Cellular Repair Pathways (NHEJ and HDR)

The advent of targeted genome editing has revolutionized biological research and therapeutic development, with its fundamental mechanics rooted in the cellular repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs). DSBs represent the most severe form of DNA damage, posing a critical threat to genomic integrity and cell survival [27] [28]. When such breaks occur, cells activate a sophisticated network of DNA Damage Response (DDR) pathways to detect, signal, and repair the lesions [29]. The two primary mechanisms for repairing DSBs are Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and Homology-directed repair (HDR) [29] [27]. These repair pathways are not merely background biological processes; they are the essential mechanisms that researchers harness to achieve precise genetic modifications using engineered nucleases like ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR/Cas9 [2] [30]. The fundamental difference between these pathways lies in their requirement for a template: NHEJ directly ligates broken ends, while HDR requires a homologous DNA template to accurately restore the sequence [29] [31].

The competition and cooperation between NHEJ and HDR pathways determine the outcome of genome editing experiments. Understanding their distinct mechanisms, efficiencies, and cellular regulation is paramount for selecting the appropriate strategy for specific research goals, whether it's gene knockout, precise point mutation, or gene knockin [29] [31]. This knowledge is particularly crucial in plant research, where the efficiency of genetic modifications can significantly accelerate basic science and breeding programs [30].

Molecular Mechanisms of NHEJ and HDR

The Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) Pathway

NHEJ is considered the dominant and faster DSB repair pathway in most eukaryotic cells, operating throughout the cell cycle but particularly dominant outside the S and G2 phases [27]. This pathway is often described as "error-prone" because it rejoins broken DNA ends without requiring a homologous template, frequently resulting in small insertions or deletions (INDELs) at the repair site [29] [31].

The molecular mechanism of NHEJ initiates with the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer recognizing and binding to the broken DNA ends [27]. This complex then recruits and activates the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs), forming the complete DNA-PK complex [27]. Subsequently, end-processing enzymes such as the Artemis nuclease may be recruited to trim damaged ends or overhangs [27]. Finally, the XRCC4-DNA ligase 4 (Lig4) complex, stabilized by XRCC4-like factor (XLF), performs the ligation step that physically rejoins the DNA strands [27]. A recent groundbreaking study revealed that NHEJ employs distinct mechanisms to repair each strand of a double-strand break, with simpler breaks being joined near-simultaneously while more complex end structures require obligatorily ordered repair where the first strand repaired serves as a template for the second [32].

The Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) Pathway

In contrast to NHEJ, HDR is a precise, "error-free" repair mechanism that utilizes a homologous DNA template—typically a sister chromatid during the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle—to accurately restore the original sequence at the break site [29] [27]. This pathway is highly conserved and provides the foundation for precise genome editing applications.

The HDR process begins with the MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) complex recognizing the DSB site [27]. This complex, along with its cofactor, initiates end resection, a 5' to 3' nucleolytic degradation of the broken DNA ends that generates 3' single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhangs [27]. The exposed ssDNA is rapidly coated by replication protein A (RPA), which removes secondary structures and prevents degradation [27]. Key mediator proteins, including BRCA1 and BRCA2, then facilitate the replacement of RPA with the RAD51 recombinase to form a nucleoprotein filament [27]. This RAD51-coated filament invades the homologous donor template—whether a sister chromatid or an exogenously supplied donor DNA—and uses this template to guide accurate DNA synthesis and repair [27].

Table 1: Key Protein Complexes in NHEJ and HDR Pathways

| Repair Pathway | Key Initiating Complex | Primary Effector Proteins | End Processing Enzymes | Ligation/Resolution Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHEJ | Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer | DNA-PKcs | Artemis nuclease, Pol μ, Pol λ | XRCC4, Lig4, XLF |

| HDR | MRN complex (MRE11-RAD50-NBS1) | RPA, BRCA1, BRCA2, RAD51 | Exonucleases (e.g., MRE11) | DNA polymerase, DNA ligase |

Diagram 1: Molecular Mechanisms of NHEJ and HDR Pathways. NHEJ rapidly ligates broken ends, often generating INDELs, while HDR uses a homologous template for precise repair.

Comparative Analysis of Genome Editing Platforms

ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR/Cas9: Mechanisms and Applications

The three major genome editing platforms—ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR/Cas9—all operate through a common fundamental principle: creating targeted DSBs in the genome to harness cellular repair mechanisms [2]. Despite this shared mechanism, they differ significantly in their molecular architecture, specificity, and practical implementation.

Zinc-Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) are chimeric proteins composed of a customizable DNA-binding domain—formed by assembling multiple Cys2-His2 zinc-finger motifs (each recognizing approximately 3 bp)—fused to the FokI nuclease domain [2]. ZFNs function as dimers, requiring two complementary ZFN units to bind opposite DNA strands with precise spacing and orientation for FokI dimerization and subsequent DSB formation [2].

Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) similarly fuse a customizable DNA-binding domain to the FokI nuclease domain. However, TALENs utilize TALE repeat domains derived from Xanthomonas bacteria, with each repeat recognizing a single base pair through two hypervariable amino acids known as repeat-variable diresidues (RVDs) [2]. This simpler, more predictable code (e.g., NI for A, NG for T, HD for C, NN for G) provides greater design flexibility compared to ZFNs [2].

CRISPR/Cas9 represents a fundamentally different approach, utilizing a RNA-guided DNA recognition mechanism. The system consists of two components: the Cas9 nuclease and a single guide RNA (sgRNA) that directs Cas9 to complementary genomic sequences adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) [2] [30]. This RNA-based targeting eliminates the need for protein engineering for each new target, significantly simplifying and accelerating the design process [2] [30].

Table 2: Comparison of Major Genome Editing Platforms

| Feature | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR/Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Recognition Mechanism | Protein-based (Zinc finger domains) | Protein-based (TALE repeats) | RNA-based (sgRNA) |

| Targeting Specificity | 18-24 bp (dimer) | 30-40 bp (dimer) | 20 bp + PAM |

| Nuclease Component | FokI (requires dimerization) | FokI (requires dimerization) | Cas9 (single protein) |

| Targeting Constraints | Requires G-rich sequences; context-dependent effects | Requires 5'-T precursor; repetitive cloning challenges | Requires PAM sequence (NGG for SpCas9) |

| Editing Efficiency | Moderate | Moderate to High | High |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Low | Low | High (multiple gRNAs) |

| Ease of Design & Construction | Complex (context-dependent effects) | Moderate (repetitive cloning) | Simple (cloning of sgRNA) |

| Relative Cost | High | Moderate to High | Low |

Efficiency and Specificity in Plant Genome Editing

In plant research, the choice of editing platform is influenced by multiple factors, including transformation efficiency, cell viability, and the ability to regenerate whole plants from edited cells [30]. CRISPR/Cas9 has emerged as the predominant system for plant genome editing due to its simplicity, high efficiency, and capacity for multiplexing [30].

A critical advantage of CRISPR/Cas9 in plants is the ability to create multiple gene knockouts simultaneously through NHEJ-mediated repair by introducing numerous DSBs at different genomic loci [30]. This is particularly valuable for studying gene families with redundant functions or complex polygenic traits. For precision plant breeding applications requiring specific nucleotide changes or gene insertions, HDR-based approaches with CRISPR/Cas9 are employed, though with lower efficiency due to the competitive dominance of the NHEJ pathway [29] [30].

The specificity of each platform—the frequency of off-target effects—varies significantly. ZFNs can display considerable off-target activity due to context-dependent effects between adjacent zinc fingers [2]. TALENs generally offer higher specificity with minimal off-target effects, attributed to their longer recognition sequences and the requirement for dimerization [2]. CRISPR/Cas9 specificity depends on the sgRNA design, with off-target cleavage occurring at genomic sites bearing partial complementarity to the sgRNA, particularly in sequences with mismatches in the 5' region while maintaining PAM compatibility [2] [30].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Designing Experiments for Controlled DSB Repair

To achieve predictable genome editing outcomes, researchers must carefully design their experiments to steer DSB repair toward the desired pathway. For NHEJ-mediated gene knockouts, the experimental design is relatively straightforward: delivery of the nuclease (ZFN, TALEN, or CRISPR/Cas9) alone is typically sufficient to generate disruptive INDELs at the target locus [29]. The key consideration is designing targeting molecules that maximize on-target efficiency while minimizing off-target effects.

For HDR-mediated precise editing, the experimental design is more complex. Researchers must co-deliver the nuclease system with a donor DNA template containing the desired modification flanked by homology arms (sequences identical to those surrounding the DSB) [29] [31]. The length of these homology arms varies by system and organism but typically ranges from 400-800 bp for plasmid donors to shorter arms for single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) donors [31]. Critical parameters to optimize include:

- Donor concentration and design: Higher donor concentrations generally improve HDR efficiency; nuclear localization signals can enhance donor delivery [33].

- Cell cycle synchronization: Since HDR is active primarily in S/G2 phases, synchronizing cells or timing nuclease expression to coincide with these phases can enhance HDR efficiency [33].

- Modulating repair pathway preferences: Co-expression of HDR-promoting factors or temporary inhibition of key NHEJ proteins can shift the balance toward HDR [29].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for NHEJ and HDR Genome Editing. The experimental design diverges based on whether the goal is gene knockout (NHEJ) or precise editing (HDR).

Analytical Methods for Assessing Editing Outcomes

Validating genome editing outcomes requires specific analytical approaches tailored to the expected modifications. For NHEJ-generated INDELs, common detection methods include:

- T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) or Surveyor Assay: Mismatch detection assays that identify heterogeneous PCR products from pools of edited cells.

- Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP): Useful when INDELs create or destroy restriction enzyme sites.

- High-resolution melt analysis (HRMA): Detects sequence variations through differential DNA melting properties.

- Sanger sequencing followed by decomposition analysis: Precisely characterizes the spectrum of INDEL mutations.

- Next-generation sequencing (NGS): Provides comprehensive quantitative analysis of editing efficiency and mutation profiles.

For HDR-mediated precise edits, validation typically involves:

- Allele-specific PCR: Amplifies specifically the edited allele using primers that match the introduced sequence.

- Restriction-based screening: Utilizes newly introduced restriction sites in the donor template.

- Sanger sequencing: Confirms the precise sequence change without collateral mutations.

- Digital PCR (dPCR): Enables absolute quantification of HDR efficiency, particularly valuable for low-efficiency events.

Research Reagent Solutions for Genome Editing

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Genome Editing Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Genome Editing |

|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Systems | ZFN pairs, TALEN pairs, CRISPR/Cas9 (plasmid, mRNA, protein) | Creates targeted double-strand breaks at specific genomic loci |

| Donor Templates | dsDNA plasmids with homology arms, ssODNs, AAV vectors | Provides repair template for HDR-mediated precise editing |

| Delivery Tools | Electroporation systems, Lipofectamine, Viral vectors (Lentivirus, AAV) | Introduces editing components into target cells |

| Detection Assays | T7E1 enzyme, Surveyor nuclease, restriction enzymes, sequencing primers | Validates editing efficiency and characterizes mutations |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Cell synchronization agents (e.g., nocodazole), antibiotics, growth factors | Maintains optimal cellular conditions for editing and recovery |

| Enrichment Tools | Fluorescent markers, antibiotic resistance genes, FACS systems | Selects successfully edited cells from complex populations |

The strategic selection between NHEJ and HDR pathways, coupled with the appropriate genome editing platform, fundamentally determines the success of genetic engineering experiments. NHEJ offers higher efficiency and simplicity for gene disruption studies, making it ideal for functional genomics and loss-of-function studies [29] [31]. In contrast, HDR provides precision for sophisticated genetic modifications including point mutations, gene insertions, and sequence corrections, albeit with lower efficiency and greater technical complexity [29] [31].

In plant research and breeding, CRISPR/Cas9 has largely superseded ZFNs and TALENs due to its technical simplicity, high efficiency, and multiplexing capabilities [30]. However, the choice of editing platform should be guided by the specific application, with considerations for off-target potential, delivery constraints, and regulatory requirements.

The ongoing development of novel editing technologies—including base editors, prime editors, and CRISPR fusion systems that operate without creating DSBs—promises to further expand the toolbox available to researchers [20]. These advancements may eventually circumvent the inherent competition between NHEJ and HDR, offering more predictable outcomes. Nevertheless, understanding the fundamental biology of DSB repair pathways remains essential for maximizing the efficacy and safety of genome editing applications across basic research, therapeutic development, and agricultural biotechnology.

From Lab to Field: Practical Applications and Workflows for Plant Genome Editing

In plant genome editing, the journey from concept to a fully assembled vector is a critical determinant of research efficiency and success. The design and assembly of delivery vectors for Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), and Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 systems present vastly different challenges, time investments, and technical requirements [12]. While much attention focuses on the editing precision and efficiency of these systems at the genomic level, the initial stages of vector construction often pose significant bottlenecks that can dictate the feasibility of entire projects [8] [34]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of vector design and assembly complexities, timeframes, and methodologies for these three major genome-editing platforms, offering plant researchers objective data to inform their experimental planning.

Comparative Analysis of Design and Assembly Parameters

The assembly of genome editing vectors differs substantially across ZFNs, TALENs, and CRISPR-Cas9 systems, impacting researcher workload, project timelines, and technical feasibility.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Vector Design and Assembly Characteristics

| Parameter | ZFN | TALEN | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design Complexity | High [12] | Moderate to High [12] | Low [12] |

| Assembly Process | Technically demanding protein engineering [12] | Laborious stepwise cloning of repetitive sequences [34] [12] | Simple guide RNA cloning [12] |

| Primary Bottleneck | Context-dependent effects on specificity; complex design [12] | Repetitive nature of TALE arrays complicates cloning [35] | Minimal; primarily limited to sgRNA design [12] |

| Modularity | Moderate | High [8] | High |

| Typical Assembly Time | Several weeks [12] | Traditional: 1-2 weeks [12]; ZQTALEN: Significantly reduced [34] | 1-3 days [12] |

| Key Recent Improvement | - | ZQTALEN system (2025) simplifies assembly [34] [36] | Viral delivery systems (e.g., ISYmu1) bypassing complex cloning [37] |

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

TALEN Assembly: Traditional vs. Modern Protocols

Traditional TALEN Assembly

Traditional TALEN construction has been a significant barrier to widespread adoption [34]. The process involves sequentially assembling multiple repetitive DNA sequences that code for the TALE repeat units, each recognizing a single DNA base pair [8] [12]. This labor-intensive process requires:

- Stepwise Cloning: Each TALE repeat module (typically 33-35 amino acids) must be assembled in a specific order corresponding to the target DNA sequence [8].

- Repeat-Variable Diresidues (RVD) Engineering: The 12th and 13th amino acids in each repeat (the RVDs) must be carefully engineered to match the target nucleotide (NI for A, HD for C, NG for T, NN for G) [35].

- FokI Nuclease Domain Fusion: The assembled TALE DNA-binding domain must be fused to the FokI nuclease domain, which requires dimerization to become active [8].

- Quality Control: The highly repetitive nature of TALEN constructs makes them prone to recombination events in bacterial systems, requiring extensive sequence verification [35].

ZQTALEN Streamlined Protocol (2025)

The recently developed ZQTALEN system significantly simplifies this process through optimized modular assembly [34] [36]. The protocol involves:

- PCR Amplification of Repeat Units: TALE repeat units are obtained via PCR using a template vector as the amplification template [34].

- Modular Assembly: The repeats are sequentially assembled first into donor vectors to form entry vectors [34].

- Gateway Recombination: The entry vectors are transferred to destination vectors using Gateway recombination to generate the final binary vector [34].

- Codon Optimization: The system features optimized codon usage for plants and reduced repetitive sequences in the final vector, improving stability [34] [36].

This system was successfully validated by targeting the endogenous Nramp5 gene in rice, resulting in high-frequency acquisition of mutants with significantly reduced assembly time compared to traditional TALEN methods [34].

CRISPR-Cas9 Assembly Workflow

CRISPR-Cas9 vector construction is notably more straightforward, contributing to its rapid adoption [12] [35]. A typical protocol for a plant binary vector involves:

- sgRNA Design: A 20-nucleotide spacer sequence complementary to the target site is selected, considering genomic context and potential off-target sites [16].

- Oligonucleotide Annealing: Complementary oligonucleotides encoding the sgRNA target sequence are synthesized and annealed [16].

- Golden Gate Cloning: The annealed oligonucleotides are cloned into sgRNA expression plasmids (e.g., pYPQ131C, pYPQ132C) [16]. Multiple sgRNAs can be multiplexed in a single reaction (e.g., into pYPQ142) [16].

- Binary Vector Assembly: The sgRNA cassette is recombined with a Cas9 entry vector (e.g., pYPQ167) and a binary vector (e.g., pMDC32) to generate the final construct (e.g., pMDC32Cas9NktPDS) [16].

- Transformation: The final binary vector is transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens (e.g., strain AGL1) for plant transformation [16].

The entire process can be completed in days, with the simple replacement of sgRNAs enabling rapid targeting of different genomic loci without redesigning the entire system [12].

Figure 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Vector Construction Workflow. This streamlined process can be completed in days.

ZFN Assembly Challenges

ZFN assembly remains the most technically demanding approach, requiring extensive expertise and time [12]. Key challenges include:

- Complex Protein-DNA Interactions: Each zinc finger must be engineered to recognize a unique 3-nucleotide sequence, with context-dependent effects influencing specificity [12].

- Technical Expertise: The design and assembly require specialized knowledge of zinc finger protein engineering that is not readily accessible to most plant research laboratories [12].

- Low Throughput: The complexity of design and assembly limits the number of constructs that can be generated and tested within a practical timeframe [12].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of genome editing technologies requires specific molecular tools and reagents. The following table outlines key solutions for vector construction across the three platforms.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Vector Construction

| Reagent/System | Technology | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| ZQTALEN System [34] [36] | TALEN | A novel 9-plasmid system for streamlined TALEN assembly featuring optimized codon usage and reduced repetitive sequences. |

| Golden Gate Assembly System | CRISPR-Cas9 | Modular cloning system (e.g., pYPQ vectors) enabling efficient multiplexing of sgRNA expression cassettes [16]. |

| Gateway Technology | TALEN, CRISPR | Site-specific recombination system for rapid transfer of DNA fragments between entry and destination vectors [34]. |

| FokI Nuclease Domain | ZFN, TALEN | Endonuclease that must dimerize to create double-strand breaks; used in both ZFN and TALEN architectures [8]. |

| pMDC32 Binary Vector | CRISPR-Cas9 | Plant binary vector used for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of CRISPR-Cas9 constructs [16]. |

| ISYmu1 Compact System [37] | CRISPR | A compact CRISPR-like enzyme engineered for viral delivery (tobacco rattle virus), bypassing traditional vector assembly. |

The landscape of vector design and assembly for plant genome editing reveals clear trade-offs between specificity, versatility, and practical implementation. CRISPR-Cas9 systems offer unparalleled simplicity and speed in vector construction, making them accessible for high-throughput applications. While traditional TALEN assembly posed significant challenges, recent innovations like the ZQTALEN system have substantially reduced this barrier, maintaining the platform's advantage in targeting challenging genomic regions. ZFNs remain the most technically demanding option, limiting their widespread use. The choice between systems should therefore consider not only genomic editing outcomes but also the practical constraints of vector construction, including technical expertise, timeframe, and available reagents. As delivery methods continue evolving—particularly viral vectors for compact CRISPR systems—the logistical hurdles of vector assembly are likely to diminish further across all platforms.