From Veggie to Bioregenerative Systems: A Comparative Analysis of Plant Cultivation Technologies for Long-Duration Space Missions

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of plant cultivation systems developed for space missions, targeting researchers and scientists in aerospace and agricultural technology.

From Veggie to Bioregenerative Systems: A Comparative Analysis of Plant Cultivation Technologies for Long-Duration Space Missions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of plant cultivation systems developed for space missions, targeting researchers and scientists in aerospace and agricultural technology. It explores the foundational challenges of the space environment, details the evolution and operation of current methodologies like hydroponics and controlled chambers, and analyzes troubleshooting and optimization strategies for crop production. The review quantitatively and qualitatively validates system performance, including psychological benefits for crews, and concludes by synthesizing key technological gaps and future research directions for achieving sustainable bioregenerative life support for Moon, Mars, and beyond.

The Space Environment: Foundational Challenges for Plant Biology and Growth

For long-duration space missions to the Moon, Mars, and beyond, achieving sustainable plant cultivation is a critical requirement for crew nutrition, life support, and psychological well-being [1] [2]. However, plants grown in space face a unique and complex set of environmental stressors that are not present on Earth. The three primary stressors—microgravity, ionizing radiation, and confined environments—interact in ways that can profoundly affect plant growth, development, and nutritional value [3]. Understanding these individual stressors and their combined effects is essential for the design of Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS) and for ensuring the success of future exploratory missions [1]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these space stressors, summarizing their physiological impacts on plants, detailing key experimental findings, and outlining the essential tools for ongoing research.

Comparative Analysis of Space Stressors

The table below summarizes the distinct and interactive effects of the three core space stressors on plant biology.

Table 1: Comparative Impact of Primary Space Stressors on Plant Physiology

| Stressor | Key Physiological Effects | Impact on Plant Development | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microgravity | Alters meristematic competence (cell proliferation/growth) [1]; disrupts auxin and cytokinin transport and signaling [1] [4]; induces oxidative stress [3]; causes chromatin condensation and changes in gene expression [1]. | Disruption of gravitropism; altered root and shoot architecture; potential for normal seed-to-seed cycle completion despite cellular changes [1]. | In Brassica rapa microgreens, interaction with radiation caused a 24.5% reduction in root length and a significant increase in hypocotyl/root ratio [3]. |

| Radiation (Ionizing) | Generates Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS), causing oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA [3]; can induce DNA double-strand breaks; may trigger hormesis at low doses [3]. | Can reduce germination rates and seedling development; may enhance production of protective phytochemicals (e.g., polyphenols) [3]. | Chronic low-dose gamma radiation on Brassica rapa led to a decrease in fresh weight and a 17.8% increase in hypocotyl/root ratio [3]. |

| Combined Stressors (Microgravity & Radiation) | Can have additive, synergistic, or antagonistic interactions; concentrated oxidative stress in root tissues; distinct accumulation of protective polyphenols in root stele [3]. | Altered seedling growth and morphology; increased variability in biometric parameters (e.g., root length variability up to 30.1%) [3]. | Combined stress resulted in a significant accumulation of polyphenols and O₂⁻ in root meristems, unlike individual stressors [3]. |

| Confined Environments | Limited root and canopy volume; potential for altered gas exchange (CO₂/O₂); controlled, soilless growth systems (e.g., hydroponics, "plant pillows") are required [2]. | Constrained plant size; reliance on artificial lighting and nutrient delivery; potential for pathogen proliferation in closed systems [2]. | NASA's Veggie system uses clay-based "plant pillows" to distribute water and nutrients in microgravity, successfully growing lettuce, kale, and zinnias [2]. |

Key Experimental Data and Methodologies

To build a robust knowledge base, researchers employ standardized protocols to quantify plant responses to these stressors. The following table consolidates key quantitative findings and the methodologies used to obtain them.

Table 2: Key Experimental Data and Protocols for Studying Space Stressors

| Experiment / Study Focus | Plant Model | Core Methodology | Key Quantitative Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| COMBO-AGR: Combined Stressor Effects [3] | Brassica rapa (microgreens) | Four treatment scenarios: 1) Earth control (1 g), 2) Chronic irradiation (CIR) alone, 3) Simulated reduced gravity (µg) alone, 4) CIR + µg. Used MarSimulator platform. Analyzed morphology, ROS, and polyphenols. | Fresh Weight: Significantly lower under CIR at both 1g and µg.Root Length: NoIR + 1g seedlings had significantly longer roots.Hypocotyl/Root Ratio: Increased by 42.2% under CIR + µg. |

| Plant Gravity Perception [4] | Arabidopsis thaliana | Molecular genetic analysis; use of mutants (e.g., pin2, tt4); application of auxin transport inhibitors (NPA); tracking of PIN protein localization. | Identification of key genes (PINs, PID) and proteins controlling auxin asymmetrical distribution, leading to gravitropic bending. |

| VEG-03 Crop Production [5] | Dragoon lettuce, Wasabi mustard, Red Russian kale | Cultivation in NASA's Veggie chamber with LED lighting and clay-based "seed pillows". Crew monitoring, watering, and photographic documentation. Harvest for consumption and sample analysis. | Successful growth and consumption of fresh produce on ISS; samples returned for nutritional and microbial safety analysis (no harmful contamination detected). |

| Advanced Plant Habitat (APH) Study [2] | Arabidopsis thaliana, dwarf wheat | Fully automated, enclosed growth chamber with LED lights, over 180 sensors, and controlled release fertilizer. Remote monitoring and control from Kennedy Space Center. | Time-lapse video captured successful growth from seed to mature plant; research ongoing into changes at gene, protein, and metabolite levels. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Plant Gravity Perception and Response Pathway

The molecular pathway for gravity sensing and response, primarily studied in Arabidopsis thaliana, is a complex process involving statoliths, hormone signaling, and protein relocalization [4]. The following diagram illustrates the core sequence from perception to growth response.

Combined Stressor Experimental Workflow

Investigating the interaction between microgravity and radiation requires a carefully designed workflow to separate the effects of individual and combined stresses. The following diagram outlines a standard protocol for such studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful plant space biology research relies on a suite of specialized reagents, model organisms, and technological platforms.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Platforms for Space Plant Biology

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Relevance to Space Stressor Research |

|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana [4] [2] | Model plant organism with fully sequenced genome and extensive mutant libraries. | Used for fundamental research into gravity perception and genetic/molecular responses to microgravity and radiation. |

| Brassica rapa [3] | Fast-growing crop model for applied space agriculture studies (e.g., microgreens). | Ideal for testing combined stressor effects and nutritional quality in a short-duration experiment. |

| PIN Mutants (e.g., pin2) [4] | Genetically modified plants with disruptions in auxin efflux carrier proteins. | Crucial for elucidating the role of auxin transport in gravitropism and root architecture under microgravity. |

| Auxin Transport Inhibitors (NPA) [4] | Chemical reagent that blocks polar auxin transport. | Used to pharmacologically inhibit gravitropic bending, validating genetic findings. |

| Plant "Pillows" [2] | Clay-based growth substrates with controlled-release fertilizer. | NASA's solution for containing root systems and delivering water/nutrients in microgravity within confined spaces. |

| Veggie & APH Systems [2] | ISS-based plant growth chambers with tailored LED lighting and environmental controls. | Essential platforms for conducting real microgravity experiments; APH provides extensive sensor data and automation. |

| Ground-Based Simulators (RPM, MarSimulator) [1] [3] | Devices on Earth to simulate microgravity (clinorotation, magnetic levitation) and combined stressors. | Enable preliminary studies and protocol development before costly spaceflight experiments. |

| Fixatives (e.g., for RNA) [2] | Chemicals to preserve biological samples at a specific moment (e.g., post-stimulus). | Allows for "snapshot" analysis of gene expression (e.g., in response to flag-22 immune trigger) in space-flown samples. |

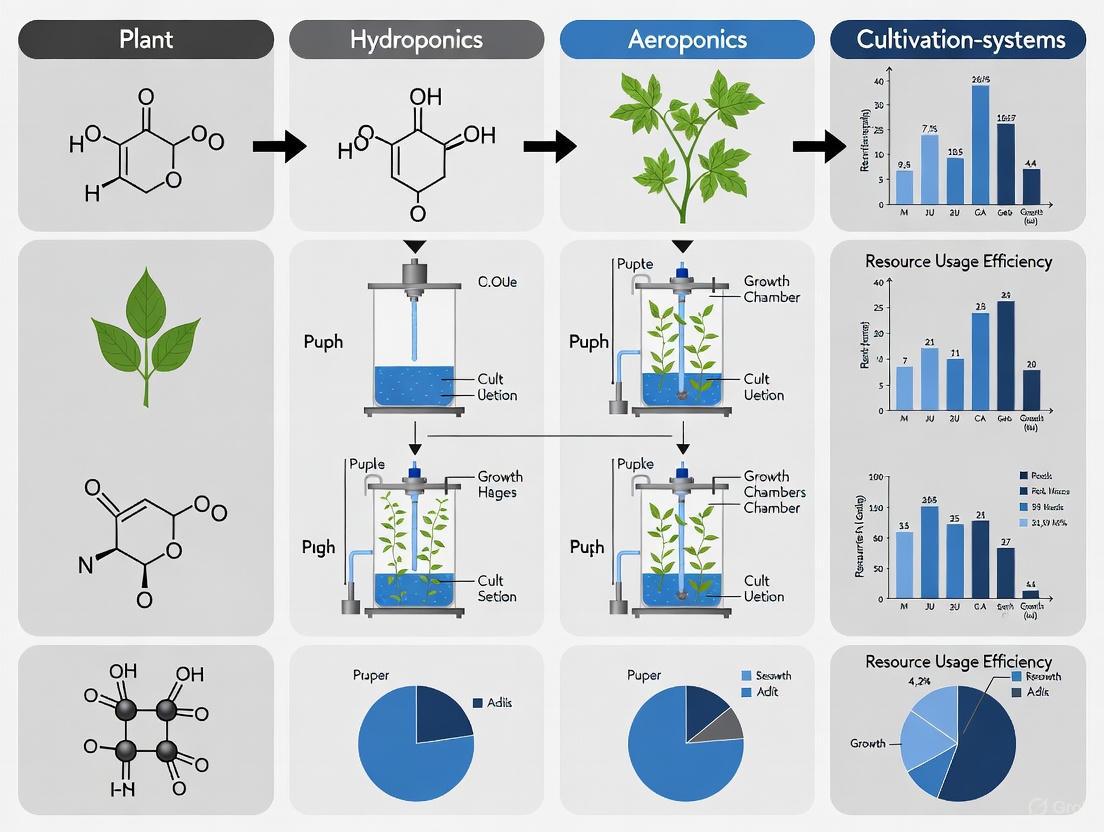

Establishing a Bioregenerative Life Support System (BLSS) is widely recognized as a crucial prerequisite for long-term human space exploration and the potential establishment of extraterrestrial bases [6]. In these systems, higher plants are fundamental components, performing multiple life-sustaining functions: they generate oxygen through photosynthesis, absorb carbon dioxide, produce fresh food for astronauts, and contribute to water recycling [6] [7]. However, the space environment, particularly microgravity, presents profound challenges to plant growth and development. On Earth, gravity is a constant force that guides plant architecture—roots exhibit positive gravitropism (growing downward), and shoots exhibit negative gravitropism (growing upward). This fundamental environmental cue is absent in space, leading to a phenomenon often described as "space syndrome" in plants, where morphological development becomes disoriented [6]. This article objectively compares advanced plant cultivation systems—specifically Hydroponics and Aeroponics—within the context of space mission constraints, evaluating their performance based on water usage, growth rates, and operational complexity, and linking these physiological outcomes to the molecular changes induced by microgravity.

Performance Comparison of Cultivation Systems

System Definitions and Operational Principles

- Hydroponics: This soil-less cultivation method involves growing plants with their roots submerged in a nutrient-rich aqueous solution [8] [9]. Variations include the Nutrient Film Technique (NFT), where a shallow film of solution flows over the roots, and Deep-Water Culture (DWC), where roots are suspended in a deeply oxygenated solution [10] [9].

- Aeroponics: A more advanced technique where plant roots are suspended in the air within a closed chamber and are periodically misted with a nutrient-dense aerosol [8] [11]. This method provides the roots with maximal oxygen exposure, which can significantly enhance growth rates [12] [8].

Comparative Performance Data from Ground-Based Studies

Ground-based experiments provide critical performance data for these systems. One comparative study evaluated several hydroponic methods and Aeroponics against a soil control, measuring key metrics such as plant mass, fruit yield, and resource consumption [10].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Different Cultivation Systems (Ground-Based Experiment)

| Cultivation System | Tomato Plant Mass | Tomato Fruit Yield | Water Consumption | Root Zone Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drip Hydroponics | Largest plant mass | Slow to flower | Moderate | Data Not Available |

| Deep-Water Culture (DWC) | Plant died prematurely | No yield (plant died) | Highest | Coolest (due to evaporation) |

| Aeroponics | Healthy growth | Largest and greatest quantity | Very Low | Warmest (due to fogger heat) |

| Kratky (Passive Hydroponics) | Healthy growth | Second-best yield | Lowest | Data Not Available |

| Soil (Control) | Moderate growth | Moderate yield | High | Data Not Available |

The broader advantages and disadvantages of Hydroponics and Aeroponics, synthesized from multiple commercial and technical sources, are summarized below [8] [11]. This comparison highlights the critical trade-offs between resource efficiency and operational complexity, which are paramount considerations for space missions.

Table 2: General Advantages and Disadvantages of Hydroponics vs. Aeroponics

| Feature | Hydroponics | Aeroponics |

|---|---|---|

| Water Usage | Saves ~80% water vs. soil [8] | Saves ~95% water vs. soil; mist is recirculated [8] [10] |

| Growth Rate | Up to 50% faster than soil [8] | Faster than Hydroponics due to superior root zone oxygenation [12] [11] |

| Operational Complexity | Lower; suitable for beginners [11] | Higher; requires precise control and maintenance [8] [11] |

| Dependence on Electricity | High (for water pumps and lights) [11] | High (for mist pumps); continuous monitoring needed [11] |

| System Maintenance | Requires periodic cleaning and pH checks [8] | More frequent maintenance; mist nozzles can clog [8] [11] |

| Initial Cost | Moderate; systems can be DIY [10] [8] | Higher due to specialized equipment like ultrasonic foggers [10] [11] |

Molecular and Physiological Responses to Microgravity

Gravitropism and the Disruption of Plant Morphology

Gravity is a fundamental environmental factor that has shaped plant physiology throughout evolution. In its absence, the well-defined tropisms that govern root and shoot orientation are disrupted [6]. Research on the International Space Station (ISS) has shown that in microgravity, plants lose their directional growth cues. Stems and roots grow in an unordered manner, which compromises the plant's ability to position leaves for optimal light capture and roots for efficient nutrient and water uptake [6]. This disordered growth is a visible manifestation of profound changes in gene and protein expression, leading to the "space syndrome" that severely impacts crop yield in space [6].

Key Signaling Pathways and Molecular Changes

Space-based experiments, particularly those using model plants like Arabidopsis thaliana, are focused on unraveling the molecular basis of these physiological changes. The European Modular Cultivation System (EMCS) on the ISS has been instrumental in studies investigating phototropism, gravitropic sensing in roots, circumnutation, and cell wall dynamics [13]. The diagram below synthesizes the current understanding of how the absence of gravity disrupts key plant signaling pathways.

The molecular logic is a cascade: The primary stress of microgravity is perceived by plant cells, potentially through the altered sedimentation of statoliths (dense starch-filled plastids) [6]. This perception disrupts calcium signaling, a key second messenger, and impairs the polar transport of auxin—the master hormone coordinating tropic responses and patterning. The mislocalization of auxin leads to widespread changes in gene and protein expression, which in turn affects fundamental processes like cell wall biosynthesis and remodeling ("cell wall dynamics") [13]. These molecular alterations ultimately manifest as the observed physiological outcomes of disordered growth and reduced yield.

Experimental Protocols for Space-Based Plant Research

Workflow for "Seed-to-Seed" Experiments in Space

A critical milestone in space botany is achieving a full "seed-to-seed" life cycle, where plants germinate, grow, flower, and produce a new generation of seeds entirely in microgravity. The recent experiment on the Chinese Space Station (CSS) that successfully accomplished this with rice and Arabidopsis serves as a key protocol [6]. The following diagram outlines the generalized experimental workflow derived from this and other ISS experiments [6] [13] [7].

The workflow involves several critical phases: First, seeds are sterilized and pre-loaded into specialized experimental units on the ground before launch [6]. Once in orbit, astronauts install these units into the space station's cultivation system, such as the Life Ecology Experiment Cabinet on the CSS or the European Modular Cultivation System (EMCS) on the ISS, and initiate growth by injecting nutrient solution [6] [7]. The cultivation is largely automated, with systems controlling light, temperature, humidity, and nutrient delivery. A vital component is the use of an on-board centrifuge to generate simulated Earth gravity (1g) as an in-situ control to isolate the effects of microgravity from other spaceflight factors [13] [7]. During the growth period, astronauts perform scheduled samplings, collecting plant tissues that are immediately preserved in the station's low-temperature storage cabinets for post-flight molecular analysis (e.g., transcriptomics, proteomics) [6]. Finally, the preserved samples and newly harvested seeds are returned to Earth for comprehensive analysis, confirming the completion of the life cycle and revealing the molecular signatures of space adaptation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Conducting plant experiments in space requires highly specialized and automated equipment. The table below lists key hardware and reagents essential for this research, as derived from the described experimental protocols [6] [13] [7].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Hardware for Space Plant Biology

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application in Space Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Life Ecology Experiment Cabinet | A multi-functional, automated platform for plant cultivation on the Chinese Space Station [6]. | Provides controlled light, temperature, humidity, and nutrients for plant growth; supports real-time monitoring and sampling. |

| European Modular Cultivation System (EMCS) | A dedicated plant growth facility on the ISS with integrated centrifuges [13]. | Enables experiments in microgravity and variable gravity levels (up to 2.0 g) for in-orbit controls. |

| Generic Biological Experiment Module | A standardized unit that holds plant seeds and growth substrates [6]. | Serves as the "pot" or container for individual plant samples; is installed into larger cultivation systems. |

| Hydroponic/Aeroponic Nutrient Solution | A meticulously formulated liquid containing all essential macro and micronutrients for plant growth [9] [14]. | Delivers water and nutrients to plant roots in the absence of soil; composition is critical for health and yield. |

| On-Orbit Centrifuge | A device inside a cultivation system that generates artificial gravity. | Creates a 1-g control environment within the microgravity setting, allowing scientists to disentangle the effects of gravity from other factors. |

| Low-Temperature Preservation Cabinet | A refrigeration or freezing unit for sample storage on the space station [6]. | Preserves plant tissue, RNA, and proteins at specific stages of development for post-flight molecular analysis. |

The choice between advanced cultivation systems like Hydroponics and Aeroponics for space missions is a complex trade-off between resource efficiency and operational robustness. Aeroponics offers superior performance in terms of water conservation and potential growth speed, making it an attractive option for a BLSS where resources are extremely limited. However, its higher technical complexity and sensitivity to system failures pose significant risks. Hydroponics, particularly more passive forms like the Kratky method, may offer greater reliability with still-substantial resource savings compared to soil, a valuable characteristic for initial, lower-risk missions [10]. Ultimately, the optimal system will depend on the specific mission duration, destination, and available crew time for maintenance. Future research must continue to refine these systems and deepen our understanding of plant molecular biology in microgravity. This will ensure that plants, our silent green partners, can reliably fulfill their role in supporting humanity's journey to the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

The pursuit of sustainable plant cultivation systems has been a cornerstone of space exploration research for over four decades. This endeavor is critical for supporting long-duration missions by providing fresh food, oxygen regeneration, and psychological benefits for crew members [15] [2]. The unique challenges of the space environment, particularly microgravity and altered convection, have driven the development of specialized technologies and experimental approaches to understand and overcome these barriers [16] [17]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of the evolution of plant growth systems, the biological insights gained, and the experimental protocols that have shaped this vital field of research.

Historical Progression of Space Plant Experiments

The following table chronicles the key milestones in the history of plant growth experiments in space, highlighting the progression from simple exposure studies to complex, automated growth systems.

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Key Plant Growth Experiments in Space

| Year(s) | Mission/Facility | Plants Studied | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1946 | U.S. V-2 Rocket | Maize, Rye, Cotton | First seeds successfully recovered from a suborbital flight; studies focused on radiation exposure [15]. |

| 1982 | Salyut 7 (Fiton-3) | Arabidopsis | First plants to flower and produce seeds in space [15]. |

| 1997 | Mir (SVET-2) | Unknown | Achieved full seed-to-seed plant growth cycle in space [15]. |

| 2014-2015 | ISS (Veggie) | Red Romaine Lettuce | First crop harvested and consumed by American astronauts (Exp. 44); proven safe for consumption [15] [2]. |

| 2015-2021 | ISS (Veggie/Veg-04, Veg-05) | Mizuna mustard, Tomatoes | Tested crop yield, nutrition, and flavor under different light conditions; crew enjoyed gardening [18]. |

| 2017-Present | ISS (Advanced Plant Habitat) | Arabidopsis, Dwarf Wheat | Fully automated, sensor-rich facility enabling detailed plant physiology studies with minimal crew effort [15] [2]. |

| 2018-Present | ISS (VEG-03) | Extra Dwarf Pak Choi, Lettuce | Demonstrated the first successful plant transplant in space, saving struggling plants [18]. |

| 2020-Present | ISS (Plant Habitat-04) | Chile Peppers | First fruiting crop cultivated on the ISS; crews assessed flavor and texture [2] [18]. |

| 2023 | Earth-based Lab | Arabidopsis thaliana | Germinated and grew in lunar soil, but showed morphological and genetic signs of stress [15]. |

Comparative Analysis of Cultivation Systems

As experiments advanced, so did the hardware. The table below compares the core technologies that have been developed to support plant life in space.

Table 2: Comparison of Primary Plant Cultivation Systems for Space

| System | Growth Method | Key Features | Crew Interaction | Example Crops Grown |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veggie | Porous clay-based "pillows" [2] | Simple, low-power; uses magenta-pink LEDs for growth [2]. | High - manual watering and plant care [2]. | Lettuce, cabbage, zinnia flowers [2] [18]. |

| Advanced Plant Habitat (APH) | Porous clay substrate with controlled-release fertilizer [2] | Enclosed, automated with 180+ sensors; multiple LED colors for complex studies [15] [2]. | Low - minimal day-to-day care required [2]. | Arabidopsis, dwarf wheat [15] [2]. |

| Hydroponics/Aeroponics | Water-based or mist-based nutrient delivery [19] [16] | Soil-free; efficient water and nutrient use. Proposed for future large-scale crop production [18] [16]. | Varies by system automation. | Tested for large-scale crops [18]. |

| Biological Research in Canisters (BRIC-LED) | Petri dishes with agar or gel media [2] | Small-scale; supports study of microbes and small plants; LED-equipped [2]. | Low - primarily for sample fixation [2]. | Arabidopsis seedlings, yeast, microbes [2]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Findings

Veggie System Protocol

The Vegetable Production System (Veggie) has been a workhorse for plant research on the ISS. The standard methodology involves [2]:

- Plant Pillow Preparation: Seeds are pre-planted in special fabric "pillows" filled with a clay-based growth media and slow-release fertilizer.

- Activation: Crew members install the pillows in the Veggie unit and activate a reservoir of water that wicks into the pillows to germinate the seeds.

- Care and Monitoring: Astronauts manually water the plants as needed and monitor their health. A bank of LED lights, primarily red and blue, provides a light spectrum conducive to growth, creating a characteristic magenta-pink glow [2].

- Harvest and Analysis: At maturity, plants are harvested. Some are consumed by the crew after surface cleaning, while others are frozen or chemically fixed and returned to Earth for laboratory analysis to ensure food safety and study molecular changes [2].

Gravitational Response Studies

A fundamental focus of space botany is understanding how plants sense and respond to the absence of gravity. The diagram below illustrates the current understanding of gravitropism, a key process disrupted in microgravity.

Diagram Title: Plant Root Gravitropism: Earth vs. Microgravity

This mechanism explains why roots on Earth grow downward, while in microgravity, their growth direction is unregulated, with some roots even growing in the same direction as the stems [17].

Molecular Omics Profiling

Modern plant space biology employs comprehensive omics strategies to gain a systems-level understanding. A typical workflow for such an experiment is as follows:

Diagram Title: Workflow for Space Plant Omics Studies

This integrated approach reveals that spaceflight induces profound molecular changes, including alterations in gene expression related to stress responses, cell wall remodeling, and hormone signaling, as well as reprogramming of energy metabolism and membrane composition [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Successful plant research in space relies on specialized materials and reagents designed to function reliably in microgravity.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Space-Based Plant Biology

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Plant Pillows | Fabric packages containing clay-based growth media and fertilizer; wick water to roots and provide aeration in microgravity [2] [18]. | Used in the Veggie system to grow lettuce, cabbage, and pak choi [2] [18]. |

| Controlled-Release Fertilizer | Embedded in growth media to provide a steady, long-term supply of essential nutrients to plants [2]. | Used in both the Veggie and Advanced Plant Habitat (APH) systems [2]. |

| LED Light Arrays | Provide specific light spectra (red, blue, green, white, far-red) optimized for plant growth and experimental imaging in space [2] [18]. | Standard in Veggie (magenta light) and APH (full spectrum); used to study light effects on plant yield and nutrition [2] [18]. |

| Chemical Fixatives | Preserve biological samples (e.g., plant tissues) at a specific moment by halting all cellular activity for post-flight molecular analysis [2]. | Used in BRIC-LED experiments to "freeze" the plant's gene expression response to immune triggers for later RNA analysis on Earth [2]. |

| Flag-22 Peptide | A conserved 22-amino acid sequence derived from bacterial flagella; used to experimentally trigger a plant's innate immune response without using live pathogens [2]. | Applied in ground-based studies to simulate pathogen attack and investigate if spaceflight alters plant immune function [2]. |

| Porous Clay Substrate | Serves as a sterile, inert support structure for roots, facilitating the distribution of water, nutrients, and air [2] [16]. | The growth media used in the Advanced Plant Habitat (APH) [2]. |

| Hydrogels | Polymer materials that can absorb and hold large amounts of water and nutrients, potentially acting as a soil substitute in microgravity [16]. | Proposed for use in future substrate-free hydroponic systems to aid water and nutrient delivery [16]. |

Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS) are advanced, closed ecosystems essential for long-duration human space exploration, enabling mission self-sufficiency by recycling resources and producing food. Within these systems, higher plants serve as the cornerstone photoautotrophic compartment, performing critical functions including oxygen production, carbon dioxide recycling, water purification, and fresh food production. This review objectively compares the performance of various plant species and cultivation technologies for space applications, analyzing quantitative data on growth parameters, nutritional profiles, and resource requirements. We synthesize experimental data from ground-based demonstrators and spaceflight experiments to define the specific requirements for plant integration into BLSS, addressing the unique constraints of microgravity, ionizing radiation, and closed-loop resource management.

Long-duration human space exploration missions to the Moon and Mars require environmental control and closed Life Support Systems (LSS) capable of producing and recycling resources to fulfill all essential metabolic needs for human survival, where resupply from Earth becomes technically and economically unfeasible [21]. Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS), also termed Closed Ecological Life Support Systems (CELSS), represent the next evolution beyond current mostly abiotic LSS through the incorporation of biological elements for additional resource recovery, food production, and waste treatment solutions [21]. These systems are conceived as artificial ecosystems comprising several interconnected compartments in which different organisms sequentially recycle resources [1].

The BLSS concept mimics natural ecological networks where multiple trophic levels guarantee biomass cycling [21]. As illustrated in Figure 1, a BLSS typically integrates three main functional compartments: (1) biological producers (e.g., plants, microalgae, photosynthetic bacteria) that generate biomass and oxygen via photosynthesis; (2) consumers (i.e., crew members) who utilize these products; and (3) waste degraders and recyclers (e.g., fermentative and nitrifying bacteria) that break down waste materials into forms usable by the producers [21]. Within this loop, the higher plant compartment provides unique, multifunctional capabilities that cannot be fully replaced by physicochemical processes or microbial systems alone.

Table 1: Core Functions of Plant Compartments in BLSS

| Function | Mechanism | Significance for Long-Duration Missions |

|---|---|---|

| Food Production | Photosynthetic conversion to edible biomass | Provides fresh nutrition; counters vitamin degradation in stored foods [21] |

| Air Revitalization | CO₂ absorption and O₂ production via photosynthesis | Maintains cabin atmosphere; reduces reliance on physicochemical systems [21] |

| Water Recovery | Transpiration and water purification | Closes water loop; provides potable water [21] |

| Waste Recycling | Utilization of mineralized waste products | Converts crew waste into nutrients for plant growth [21] |

| Psychological Support | Horticultural therapy through plant interaction | Counters isolation and confinement effects [21] |

The requirements for plant compartments vary significantly based on mission architecture. For short-duration missions in Low Earth Orbit (LEO), plant production focuses on fast-growing species that occupy minimal volumes while providing high nutritive value, such as leafy greens, microgreens, or sprouts [21]. These function primarily as dietary supplements and provide psychological benefits without substantial contributions to resource recycling. In contrast, for long-duration missions and planetary outposts, staple crops (e.g., wheat, potato, rice, soy) must be included to provide carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, along with longer-cycle vegetables and fruits (e.g., tomato, peppers, beans, berries) [21]. In these scenarios, plants substantially contribute to resource recycling but require significantly more growing area and resource inputs.

Comparative Analysis of Candidate Plant Species for BLSS

The selection of plant species for BLSS involves balancing multiple factors including growth characteristics, nutritional value, environmental requirements, and compatibility with space cultivation constraints. Research has focused on a range of species from traditional crops to alternative species with specialized advantageous traits.

Conventional Crops: From Salad Machines to Staple Foods

The "salad machine" or "vegetable production unit" concept, proposed since the early 1990s, focuses on fast-growing species for dietary supplementation [21]. NASA's Vegetable Production System (Veggie) on the International Space Station has successfully grown multiple crops including three types of lettuce, Chinese cabbage, mizuna mustard, red Russian kale, and zinnia flowers [2]. These species typically have short growth cycles, minimal spatial requirements, and provide high levels of nutraceuticals like antioxidants and prebiotics [21].

For long-duration missions, staple crops become essential. Current research includes dwarf varieties of wheat, rice, and potato, selected for their nutritional value, resource efficiency, and high edible-to-waste biomass ratio [21]. The Advanced Plant Habitat (APH) on the ISS, a more automated and enclosed growth chamber compared to Veggie, has conducted experiments with Arabidopsis thaliana and dwarf wheat to study space-specific plant responses [2].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Selected Plant Species for BLSS

| Species | Growth Cycle (Days) | Edible Biomass Yield | Key Nutrients | Resource Efficiency | Space Validation Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red Romaine Lettuce | 28-35 | Moderate | Vitamins A, C, K; antioxidants | High water use efficiency | Extensive (Veggie ISS) [2] |

| Wolffia species | 10-14 (doubling time) | Very high (relative growth rate 0.155-0.559 day⁻¹) | Complete protein (40% by weight), omega-3 fatty acids | Extremely high; no non-edible biomass | Proposed; limited space testing [22] |

| Dwarf Wheat | 60-70 | High | Carbohydrates, protein | Moderate-high nutrient requirements | APH ISS testing [2] |

| 'Outredgeous' Lettuce | 28 | Moderate | Vitamins, antioxidants | Moderate | Veggie ISS [23] |

| Zinnia hybrids | 60-70 | Ornamental only | N/A | Moderate | Veggie ISS (psychological benefit) [2] |

Alternative Species: The Case of Wolffia

A different selection approach focuses on alternative species not widely cultivated on Earth but possessing attractive traits for space applications. Among these, plants in the family Lemnaceae (duckweeds), particularly the genus Wolffia, show significant promise [22]. Wolffia species represent the smallest and fastest-growing flowering plants, with distinctive advantages for BLSS applications [22].

Key advantageous traits of Wolffia species include:

- Exceptional Growth Rates: Relative growth rates ranging from 0.155 to 0.559 day⁻¹, among the highest observed in angiosperms [22].

- Maximized Harvest Index: Rootless morphology eliminates production of non-edible biomass [22].

- Nutritional Profile: Contains up to 40% protein by weight (complete with all essential amino acids), beneficial omega-3 fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals, while lacking antinutritional compounds like oxalic acid present in some terrestrial vegetables [22].

- Cultural Simplicity: Floating aquatic habit potentially simplifies cultivation system design and nutrient delivery in microgravity [22].

- Positive Buoyancy: This natural trait could facilitate the transition between Earth and space environments where gravity is absent [22].

Despite these advantages, significant research gaps remain before Wolffia can be successfully integrated into operational BLSS. These include understanding reproductive biology (particularly sexual reproduction for genetic diversity), responses to space environmental factors (microgravity, radiation), and optimization of cultivation conditions for space applications [22].

Experimental Platforms and Methodologies for BLSS Plant Research

The development of plant compartments for BLSS relies on both ground-based and space-based research facilities with progressively increasing capabilities and integration levels.

Ground-Based BLSS Demonstrators

Several large-scale ground-based demonstrators have tested closed-loop BLSS with human crews:

- BIOS-1, 2, 3, and 3 (Russia): Early integrated BLSS testing facilities [21].

- Biosphere 2 (USA): Large-scale closed ecological system [21].

- Closed Ecology Experiment Facility (CEEF) (Japan): Advanced integrated BLSS testing [21].

- Lunar Palace 1 (China): Recent BLSS demonstrator [21].

- MELiSSA Pilot Plant (Spain) and PaCMan (Italy): European Space Agency facilities developing and testing closed-loop system compartments for oxygen, water, and food production [21].

These facilities enable testing of specific technologies for controlled cultivation chambers, food production systems, and biological waste management, while also allowing evaluation of psychological impacts on isolated crews and potential benefits of plant interactions [21].

Space-Based Plant Growth Facilities

Current space-based plant growth systems range from simple cultivation chambers to highly automated facilities:

Vegetable Production System (Veggie)

- Design: Approximately carry-on luggage sized unit supporting six plants [2].

- Growth Method: Plant "pillows" containing clay-based growth media and fertilizer [2].

- Environmental Control: LED lighting bank producing spectrum optimized for plant growth (predominantly red and blue, appearing magenta pink) [2].

- Functionality: Requires significant crew interaction for watering, maintenance, and monitoring [23].

Advanced Plant Habitat (APH)

- Design: Enclosed, automated chamber with extensive monitoring capabilities [2].

- Sensing: Over 180 sensors in constant contact with ground teams [2].

- Environmental Control: Fully automated water recovery and distribution, atmosphere content, moisture levels, and temperature [2].

- Lighting: Expanded spectrum including red, green, blue, white, far red, and infrared for growth and nighttime imaging [2].

- Operation: Minimal day-to-day crew care required [2].

Biological Research in Canisters (BRIC-LED)

- Design: Compact facility for small organisms including plants, mosses, algae, and cyanobacteria [2].

- Capability: LED lighting for photosynthetic organisms [2].

- Application: Gene expression studies, particularly plant immune responses to space conditions [2].

Figure 1: Material flows between the three main compartments of a Bioregenerative Life Support System (BLSS), showing the interconnected cycling of resources that enables system closure [21].

Key Experimental Protocols

Gene Expression Analysis in Altered Gravity

- Objective: Understand plant molecular responses to microgravity and partial gravity (Moon: 0.17g, Mars: 0.38g) [1].

- Methodology: Transcriptomic and proteomic analysis of plants grown in space facilities (EMCS, Veggie, APH) and ground simulators (Random Positioning Machine, clinostats) [1].

- Key Findings: Reprogramming of gene expression affecting heat shock elements, cell wall remodeling factors, oxidative burst intermediates, and general plant defense mechanisms; differential responses at various gravity levels [1].

- Experimental Model: Arabidopsis thaliana as primary model organism; crop species including lettuce, wheat, and peppers for applied studies [1] [2].

Plant Immune Function Assessment

- Objective: Evaluate space impact on plant pathogen defense capabilities [2].

- Methodology: Treatment with flagellin peptide (flag-22) to simulate pathogen attack without actual pathogens; subsequent transcriptomic analysis of defense pathway activation [2].

- Key Findings: Preliminary evidence of altered immune gene expression and increased oxidative stress in space-grown plants [2].

- Preservation: Chemical fixation and freezing for Earth-based analysis [2].

Seed-to-Seed Life Cycle Studies

- Objective: Verify plant capability to complete full generational cycle in space [1] [15].

- Methodology: Long-duration cultivation through germination, vegetative growth, flowering, pollination, and seed set in space environments [1] [15].

- Key Findings: Successful completion demonstrated for Arabidopsis, lettuce, and other species; however, developmental and molecular alterations observed despite normal apparent growth [1].

Technical Challenges and Plant Responses to Space Environments

Plants in space face unique environmental challenges that significantly differ from terrestrial conditions, requiring specific adaptations and technological solutions.

Microgravity and Altered Gravity Effects

Plants have evolved under Earth's 1g gravity for approximately 475 million years, yet demonstrate remarkable plasticity in responding to altered gravity conditions [1]. Key effects include:

Developmental and Physiological Impacts

- Meristem Function: Disruption of meristematic competence in root tips, characterized by loss of coordinated cell proliferation and growth patterns [1].

- Cell Cycle Alterations: Acceleration detected in simulated microgravity, with differential regulation of genes controlling G1/S and G2/M transitions [1].

- Gene Expression Reprogramming: No dedicated "gravity response genes" identified; instead, modification of existing stress response pathways including heat shock elements, cell wall remodeling factors, and oxidative burst components [1].

Gravity Perception and Signaling

- Gravity Sensing Threshold: Lentil roots can perceive accelerations as low as 10⁻³g or lower [1].

- Auxin Cytokinin Interactions: Complex, incompletely understood changes in hormone distribution and polar transport; observed decrease in polarized auxin transport in pea hypocotyls in microgravity [1].

- LAZY Proteins: Key players linking gravity perception to gravitropic response through auxin redistribution and PIN protein relocation [1].

Figure 2: Plant responses to space environmental stressors, showing the complex interplay between multiple space factors and their effects on plant molecular processes and development [1].

Ionizing Radiation Effects

The space radiation environment presents significant challenges for plant growth, particularly during long-duration missions beyond Earth's protective magnetosphere:

- Oxidative Stress: Increased production of reactive oxygen species damaging cellular components including DNA and mitochondria [2].

- Immune System Alterations: Changes in expression of genes associated with pathogen defense; potential compromise of disease resistance [2].

- Developmental Impacts: Despite radiation exposure, plants successfully complete life cycles, though cumulative genetic damage remains a concern [1].

Cultivation Technical Challenges

Root Zone Management

- Fluid Behavior: In microgravity, fluids form bubbles potentially drowning roots or creating air pockets [2].

- Solution: Clay-based "plant pillows" with controlled-release fertilizer to distribute water, nutrients, and air around roots [2].

- Alternative Systems: Porous tube delivery systems and other nutrient delivery technologies under development [15].

Gas Exchange

- Challenges: Altered convection in microgravity affects boundary layers around leaves and gas exchange [21].

- Monitoring: Continuous assessment of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and volatile organic compound levels [21].

Pathogen Management

- Vulnerability: Observations of increased fungal susceptibility in space-grown zinnias [2].

- Prevention: Microbial monitoring and sterile growth media protocols [2] [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for BLSS Plant Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Plant Growth Media | Root support, nutrient delivery, aeration | Clay-based calcined media (Veggie plant pillows) [2] [23] |

| Controlled-Release Fertilizer | Timed nutrient availability | Osmocote-type fertilizers incorporated into growth media [2] |

| LED Lighting Systems | Photosynthetic energy source, environmental signaling | Red-blue spectrum optimization (Veggie), full spectrum with infrared (APH) [2] |

| Chemical Fixatives | Preservation of biological samples for Earth analysis | RNAlater, formaldehyde, or other fixatives for transcriptomic studies [2] |

| Flagellin Peptides (flag-22) | Elicitor of plant immune responses | Simulation of pathogen attack to study defense activation [2] |

| RNA Sequencing Kits | Gene expression analysis | Transcriptomic profiling of space-grown plants [1] |

| Antibody Assays | Protein detection and quantification | Analysis of stress markers, hormone distributions [1] |

The successful integration of plant compartments into BLSS requires addressing multiple interconnected challenges spanning biological, technological, and operational domains. Current research demonstrates that plants can successfully germinate, grow, and reproduce in space environments, but with measurable alterations in physiological processes and molecular pathways. The comparison of cultivation systems reveals trade-offs between simplicity and crew time requirements (Veggie) versus automation and experimental control (APH).

Critical research gaps requiring further investigation include:

- Gravity Thresholds: Determination of minimum gravity levels required for normal plant development across species [1].

- Reproductive Biology: Optimization of pollination and seed set in space environments, particularly for staple crops [22].

- Multigenerational Studies: Assessment of genetic stability and potential adaptive evolution over multiple plant generations in space [1].

- System Integration: Closure of material loops between plant, crew, and waste processing compartments [21].

- Radiation Countermeasures: Development of biological and technological approaches to mitigate space radiation damage [1] [2].

As research progresses, the integration of plant-based systems will evolve from supplemental food production to comprehensive life support functionality, enabling the next era of human exploration beyond Earth orbit. The complementary approaches of optimizing traditional crops and developing alternative species like Wolffia provide multiple pathways toward achieving the bioregenerative capabilities necessary for sustainable presence on the Moon and Mars.

From Seed Pillows to Advanced Habitats: A Review of Current Cultivation Methodologies

The pursuit of sustainable life-support systems for long-duration space missions necessitates advanced plant cultivation technologies that operate independently of terrestrial constraints. Soilless cultivation systems, specifically hydroponics and aeroponics, have emerged as leading candidates for space-based agriculture due to their exceptional resource efficiency and compatibility with controlled environments. These systems eliminate soil dependency, thereby significantly reducing system mass—a critical factor for space launch logistics—while simultaneously maximizing water and nutrient utilization.

Research and development initiatives, particularly those spearheaded by NASA, have demonstrated the profound potential of these technologies for space application. Aeroponics, the process of growing plants with their roots suspended in air and misted with nutrient solution, has shown remarkable capability, reducing water usage by 98% and fertilizer usage by 60% compared to traditional agriculture [24]. This efficiency, combined with the observed acceleration in plant growth rates, positions these systems as foundational technologies for future missions into deep space, where crews must produce fresh food, regenerate oxygen, and purify water within a closed-loop system [24].

This guide provides an objective comparison of hydroponic and aeroponic systems, framing their performance within the specific environmental and operational requirements of space habitats.

Hydroponic Systems

Hydroponics is a method of growing plants without soil by using a nutrient-rich water solution to deliver minerals directly to the roots [25] [26]. In space applications, this approach offers a controlled and reliable means of food production. Several system designs are applicable:

- Deep Water Culture (DWC): Plants are suspended on a floating platform with their roots submerged in an oxygenated nutrient solution [27] [28]. This system is relatively simple and highly water-efficient due to its closed, recirculating nature [28].

- Nutrient Film Technique (NFT): A shallow, continuous stream of nutrient solution flows over the roots, which are contained in a sloped channel [27] [28]. The thin film of water ensures the roots have simultaneous access to nutrients, water, and oxygen, with minimal water volume [28].

- Wick Systems: A passive hydroponic system where nutrient solution is drawn up to the plant's roots from a reservoir via capillary action through wicks [28]. This method is simple and requires no moving parts, but is generally more suitable for smaller plants with lower water demands [28].

Aeroponic Systems

Aeroponics represents a more advanced technique where plant roots are suspended in a closed or semi-closed chamber and are periodically misted with a hydro-atomized nutrient solution [29]. This method provides the root zone with an oxygen-rich environment, which significantly stimulates plant growth and nutrient uptake [29]. The system's design is inherently mass-efficient for space missions, as it uses no solid growing medium and very little water is held in the system at any time.

- High-Pressure Aeroponics (HPA): Considered the most efficient method, HPA uses a high-pressure pump (e.g., 80-105 PSI) to create an ultra-fine mist with droplet sizes typically between 5-50 micrometers [29] [30]. This increases the bioavailability of nutrients and requires a reduction in nutrient strength to prevent root burn [29].

- Tower-style Aeroponics: These systems use a vertical design, where a pump lifts the nutrient solution to the top of the column, and it then cascades down over the roots inside the tower [30]. This design is popular for its space-saving efficiency, making it suitable for the volume-constrained environments of space habitats [30].

Direct System Comparison

The following table summarizes the key performance characteristics of hydroponic and aeroponic systems in the context of space mission requirements.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Hydroponics and Aeroponics for Space Applications

| Performance Metric | Hydroponics (DWC/NFT) | Aeroponics (HPA) |

|---|---|---|

| Water Usage Efficiency | High (Up to 90% savings vs. soil) [27] | Exceptional (Up to 98% savings vs. soil) [24] |

| Fertilizer Efficiency | Efficient use of nutrients [25] | High (Up to 60% reduction vs. soil) [24] |

| Plant Growth Rate | Faster than soil-based growth [26] | Faster than hydroponics; accelerated growth cycles [24] [29] |

| Oxygen Availability to Roots | Moderate (Requires active oxygenation in DWC) [31] | Maximum (Roots exposed to air) [29] [32] |

| System Mass & Volume | Higher (Requires large liquid reservoirs) | Lower (Minimal liquid volume and no media) [24] |

| Technical Complexity | Moderate [33] | High (Precision pumps and nozzles required) [26] [33] |

| System Reliability | High (Less sensitive to short-term pump failure) | Lower (Risk of root desiccation from mist failure) [29] [31] |

| Suitability for Microgravity | Challenging (Liquid management in free-fall) | More adaptable (Contained mist environment) |

Experimental Protocols and Research Findings

Key NASA and Partner Experiments

The development of aeroponics for space has been propelled by a series of collaborative experiments between NASA, commercial entities, and academic institutions.

- Mir Space Station Experiment (1997): NASA partnered with AgriHouse Inc. to deploy an aeroponic experiment on the Mir space station. This partnership focused on testing and refining aeroponic crop production technology in microgravity, establishing foundational protocols for space-based plant growth [24].

- International Space Station (ISS) Experiments: A significant experiment flown aboard the ISS in 2007 utilized AeroGrow International's "Seed Pod" technology [24]. This technology was critical for protecting seeds during transit and preventing premature germination. The experimental protocol involved:

- Seed Transport: Seeds were encased in a plastic framework (Seed Pods) for physical protection and germination control [24].

- In-Space Activation: Upon activation on the ISS, the seeds were exposed to the aeroponic environment to initiate growth.

- Comparative Ground Studies: The space-based experiment was part of a broader educational initiative involving 15,000 K-12 students who conducted parallel comparative experiments in their classrooms, providing ground-truth data [24].

- Nutrient Uptake Studies: Aeroponics has proven to be a powerful research tool for non-destructively studying plant physiology. The work of Barak et al. (1996) demonstrated the use of aeroponics to measure real-time water and ion uptake rates in cranberries by analyzing the input and efflux solutions' concentration and volume [29]. This methodology is particularly valuable for monitoring plant health and optimizing nutrient recipes in the closed environments of space habitats [29].

Aeroponic System Workflow

The core operational logic of a high-pressure aeroponics system, as used in advanced research and space applications, can be visualized as a continuous cycle of monitoring and precise delivery. The following diagram illustrates this controlled process.

Diagram 1: HPA system control loop for space habitat plant growth modules.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers developing and testing soilless cultivation systems for space, a specific set of reagents, components, and materials is essential. The selection focuses on precision, reliability, and compatibility with closed-loop environmental control.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Space Soilless Cultivation

| Item | Function/Description | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Hydroponic Nutrient Solutions | Pre-mixed or custom-formulated solutions containing macro and micronutrients. | Formulating the primary nutrient matrix for plant growth; studying ion uptake [29]. |

| pH & EC (Electrical Conductivity) Meters | Instruments for monitoring solution acidity/alkalinity and nutrient concentration. | Critical for maintaining optimal nutrient bioavailability and ion balance [25] [32]. |

| High-Pressure Diaphragm Pumps | Pumps capable of generating consistent pressure (e.g., 80-105 PSI) for mist creation. | Core component of HPA systems for generating nutrient droplets of 5-50 µm [29]. |

| Solenoid Valves & Timers | Electronic components for controlling the duration and frequency of misting cycles. | Enabling precise root zone irrigation schedules (e.g., short feed/pause cycles) [29]. |

| Low-Mass Polymer Misting Nozzles | Nozzles designed to resist mineralization and clogging, producing a fine mist. | Ensuring reliable, long-term mist delivery in HPA systems; a subject of NASA-funded material research [29]. |

| Seed Pods / Germination Supports | Sterile, porous substrates or frameworks (e.g., neoprene collars, plastic pods) to support seeds and seedlings. | Providing mechanical support for plants in the system; used in ISS experiments [24]. |

| Environmental Sensors | Sensors for monitoring root zone and canopy parameters (O₂, CO₂, humidity, temperature). | Data collection for system optimization and studying plant response to the growth environment [29] [32]. |

| Sterilants (e.g., H₂O₂) | Solutions for system decontamination and preventing pathogen growth in recirculating systems. | Maintaining a sterile root zone environment to prevent disease in closed-loop systems [29]. |

Both hydroponics and aeroponics offer compelling advantages for sustainable agriculture in space, yet they present distinct trade-offs. Hydroponic systems, particularly DWC and NFT, provide a robust, less complex, and highly reliable option for continuous food production, with a lower risk of catastrophic crop failure from single-point technical faults [31] [33].

Aeroponics, however, demonstrates superior performance in metrics critically limited in space missions: mass, water, and fertilizer efficiency [24]. The technology's ability to accelerate plant growth and increase yields further enhances its appeal. The primary challenge for aeroponics remains its higher technical complexity and sensitivity to system failures, such as clogged misters or pump malfunctions, which can lead to rapid root desiccation and plant loss [29] [31].

Future research for space applications should focus on enhancing the reliability of aeroponic systems through redundant components, advanced materials for misting hardware, and fully autonomous control systems. Integrating these soilless cultivation systems into broader closed-loop life support systems, where they contribute to air revitalization and water purification, will be the ultimate step in validating their role for long-duration exploration missions.

Plant cultivation systems are critical for advancing human space exploration, transitioning from pure research platforms to bioregenerative life support systems (BLSS) that can produce food, regenerate oxygen, and recycle water on long-duration missions. The Vegetable Production System (Veggie) and Advanced Plant Habitat (APH) represent two complementary flight hardware platforms aboard the International Space Station (ISS) that enable plant bioscience research in microgravity. Understanding the technical capabilities, research applications, and performance characteristics of these systems is essential for researchers designing space biology experiments and planning future food production missions. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these systems, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols, to inform the selection of appropriate platforms for specific research objectives in space plant sciences.

Vegetable Production System (Veggie)

The Veggie system is a simple, low-power, and scalable plant growth unit designed primarily for pick-and-eat crops and crew engagement [34]. With a growth area of approximately 0.16 m², it functions as a semi-open system that circulates ISS cabin air through the plant growth volume [35]. Its design prioritizes operational simplicity, relying on crew interaction for planting, maintenance, and harvesting activities. The system uses rooting "pillows" containing a clay-based growth substrate and controlled-release fertilizer, with a wick system for water and nutrient delivery [36]. Veggie's lighting system initially employed red and blue LEDs, with green LEDs added later to make the plants appear more palatable to the crew [37].

Advanced Plant Habitat (APH)

The APH represents the most advanced fully enclosed, environmentally controlled plant growth research facility on the ISS [35] [38]. Occupying the lower half of an EXPRESS rack, it provides a tightly regulated, closed-loop plant life support system capable of supporting research missions of up to 135 days with minimal crew involvement [34] [38]. APH incorporates comprehensive environmental control capabilities, including precise regulation of temperature, humidity, CO₂ levels, and light spectrum, supported by more than 180 sensors for real-time environmental monitoring and data collection [38] [36]. Its irrigation system utilizes a porous ceramic tube manifold within a granular argillite substrate, with active moisture content control through negative pressure to optimize root zone conditions in microgravity [35] [36].

Table 1: Technical Specifications Comparison of Veggie and APH

| Specification | Veggie | Advanced Plant Habitat (APH) |

|---|---|---|

| System Type | Semi-open, passive environmental control [35] | Fully enclosed, closed-loop environmental control [35] [38] |

| Growth Area | 0.16 m² [36] | 0.2 m² [36] |

| Primary Mission | Fresh food production, crew well-being, basic research [34] [37] | Fundamental and applied plant research [35] [38] |

| Automation Level | Low (requires crew operation) [36] | High (teleoperated from ground) [38] [36] |

| Lighting System | Red, blue, and green LEDs [37] | Full-spectrum LEDs including white, far-red, and infrared [37] |

| Maximum PPFD | Not specified in results | 1,000 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹ [35] |

| Environmental Control | Limited (dependent on ISS cabin environment) [35] | Comprehensive (CO₂, temperature, humidity, ethylene) [38] |

| Root Zone Substrate | Clay-based "pillows" with wick system [36] | Porous ceramic tubes in argillite substrate [36] |

| Sensors & Monitoring | Basic | 180+ sensors and imaging capabilities [38] [36] |

| Mission Duration | Short-term crop cycles | Up to 135 days [34] [38] |

| Crew Involvement | High (planting, maintenance, harvesting) [36] | Minimal (water addition, sample collection) [36] |

Experimental Applications and Research Output

Research Focus and Crop Selection

Veggie has primarily supported food production-oriented research and technology demonstrations, focusing on leafy greens and small fruits that can supplement the astronaut diet [39]. Successful crops include 'Outredgeous' red romaine lettuce (the first consumed in space in 2015), Tokyo bekana cabbage, mizuna mustard, Dragoon lettuce, Red Russian kale, and 'Red Robin' tomato [39] [37]. These crops were selected for their short stature, fast growth, and high organoleptic acceptance by the crew [37]. The system has also been used to study cut-and-come-again harvest methods for continuous production and to analyze the microbial communities that colonize space-grown plants [37].

In contrast, APH supports more fundamental plant biology research under highly controlled conditions. Its experiments have included multi-generational studies on Arabidopsis thaliana and dwarf wheat to understand genetic and epigenetic adaptations to spaceflight [38] [37]. The facility has been used to investigate gravitropism, lignification, metabolic responses, and canopy photosynthesis in microgravity [35] [38]. The Plant Habitat-03 experiment, for instance, specifically assesses whether epigenetic adaptations in one generation of space-grown plants can transfer to the next generation [38].

Methodologies for Key Experiments

Veggie Food Production Protocol (Veg-04B)

The Veg-04B experiment investigated how light quality and fertilizer composition affect the microbial safety, nutritional value, and taste of mizuna grown in Veggie [37]. The methodology involved:

- Plant Material: Mizuna (Brassica rapa var. japonica) seeds were planted in six plant pillows per Veggie unit, with each pillow containing a controlled-release fertilizer and calcined clay substrate [37].

- Lighting Treatments: Plants were exposed to different red:blue light ratios, with some treatments including green light to improve visual appeal and potentially influence phytochemical composition [37].

- Nutrient Delivery: A wicking system distributed water from the reservoir to the roots, with the pillows designed to prevent root drowning or air trapping in microgravity [37].

- Assessment Parameters: Crew members conducted regular observations, harvested the crops, and completed taste tests. Samples were returned to Earth for analysis of microbial communities, nutritional content, and phytochemical composition [37].

APH Canopy Photosynthesis Protocol

A 7-week hardware validation test conducted in APH demonstrated its capability to measure fundamental plant responses to spaceflight, including canopy photosynthesis [35]. The experimental methodology included:

- Plant Material: The root module was planted with both Arabidopsis (cv. Col-0) and wheat (cv. Apogee) to test different plant types and growth characteristics [35].

- Environmental Control: The APH system maintained precise environmental conditions, with CO₂ concentration actively controlled for gas exchange measurements [35].

- Gas Exchange Measurements: The CO₂ drawdown technique was used to measure daily rates of canopy photosynthesis during light periods and respiration during dark periods by monitoring chamber CO₂ concentrations [35].

- Data Collection: Three cameras (overhead, sideview, and sideview near-infrared) captured predetermined photographic events, while sensors continuously monitored environmental parameters and plant responses [35].

- Validation Parameters: The test assessed APH's ability to control light intensity, spectral quality, humidity, CO₂ concentration, photoperiod, temperature, and root zone moisture, while also validating containment of plant debris during harvest and recovery of transpired water [35].

Performance Data and Research Outcomes

Crop Production and System Performance

Veggie has successfully demonstrated the feasibility of fresh food production in space, with multiple crops being grown and consumed aboard the ISS. The first crop of 'Outredgeous' red romaine lettuce reached maturity in just 33 days in space compared to 64 days on Earth [37]. The system has proven capable of supporting sequential harvests, with the Veg-04B experiment involving multiple harvests of mizuna [37]. Microbial analysis of space-grown lettuce found communities similar to Earth-grown counterparts, indicating no unusual pathogen risks [37].

APH validation tests confirmed its sophisticated research capabilities. The system successfully maintained optimal root zone moisture and recovered transpired water by condensation, even under the high evaporative load presented by a wheat canopy [35]. The facility demonstrated precision in executing pre-programmed experimental profiles that scheduled environmental changes, photographic events, and measurement sequences throughout the plant life cycle [35]. The CO₂ drawdown experiments provided reliable measurements of canopy photosynthetic rates and dark-period respiration in microgravity [35].

Table 2: Experimental Results from Space-Based Studies

| Experiment Metric | Veggie Performance | APH Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Crop Growth Duration | Red romaine: 33 days to maturity [37] | Life cycle studies up to 135 days [38] |

| Gas Exchange Measurement | Not available | Canopy photosynthesis and respiration measured via CO₂ drawdown [35] |

| Environmental Control Precision | Limited, relies on ISS cabin environment [35] | High-precision control of all environmental parameters [38] |

| Crop Yield Success | Multiple successful crops: lettuce, Tokyo bekana, mizuna [37] | Arabidopsis and wheat grown through full life cycle [35] |

| Research Applications | Food production, crew well-being, microbial ecology [37] | Canopy photosynthesis, gravitropism, multi-generational studies [35] [38] |

| Crew Time Requirements | Higher (daily maintenance required) [36] | Minimal (largely automated) [36] |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The following table summarizes key reagents, materials, and hardware components used in plant biology research with Veggie and APH, providing researchers with essential information for experimental planning.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Space-Based Plant Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | System Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Plant "Pillows" | Growth substrate units containing media and seeds; distribute water, nutrients, and air to roots [36] | Veggie [36] |

| Calcined Clay | Growth medium component that increases aeration; similar to material used on baseball fields [37] | Veggie [37] |

| Controlled-Release Fertilizer | Provides essential nutrients to plants over time through slow-release mechanisms [37] | Veggie [37] |

| Porous Ceramic Tubes | Irrigation system component that delivers water to root zone through porous walls [36] | APH [36] |

| Argillite Substrate | Porous granular mineral material that serves as rooting media in APH [36] | APH [36] |

| LED Lighting Systems | Provides specific light wavelengths for plant growth and research; different spectra available [35] [37] | Both systems |

| Citric-Acid Sanitizing Wipes | Food safety preparation for consumed crops; sanitizes produce surfaces before consumption [37] | Veggie [37] |

System Selection Guidelines for Research Applications

The decision between Veggie and APH depends primarily on research objectives, resource constraints, and required levels of environmental control and automation. The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for selecting between these systems based on key research parameters:

Veggie is the appropriate choice for research focused on crop production optimization, food safety studies, and psychological benefit assessments [39] [37]. Its simpler design and reliance on crew interaction make it ideal for experiments where human-plant interaction is a variable of interest. The system's open nature allows plants to be exposed to the ISS cabin environment, which may be desirable for testing crop performance under realistic space station conditions [35].

APH should be selected for investigations requiring precise environmental control, minimal crew disturbance, or complex physiological measurements [35] [38]. Its capabilities make it particularly suitable for gravitropism studies, genetic and epigenetic analyses, metabolic profiling, and quantitative measurements of gas exchange [35] [38]. The system's high level of automation and extensive sensor suite enables ground-controlled experiments that can run for multiple plant generations without significant crew time investment [38] [36].

Veggie and APH represent complementary approaches to plant research in microgravity, each with distinct advantages for specific research applications. Veggie serves as a practical platform for food production research and technology demonstrations, with relatively low resource requirements and direct crew engagement. APH provides sophisticated environmental control and monitoring capabilities for fundamental plant biology research, enabling high-precision experiments with minimal crew involvement. Future developments in space plant research hardware, such as the XROOTS investigation exploring nutrient delivery by aeroponics and hydroponics, and the Ohalo III prototype for Mars transit vehicles, will build upon the capabilities demonstrated by these systems [36]. As mission durations increase and distances from Earth expand, the lessons learned from both Veggie and APH will be critical for developing the robust, scalable bioregenerative life support systems necessary for sustainable human presence beyond low Earth orbit.

Crop Selection and Cultivar Development for Optimal Space Performance

For long-duration space missions beyond Earth's orbit, the development of Bio-regenerative Life-Support Systems (BLSS) becomes essential to sustain human life by regenerating resources and producing food [40]. Plants serve as fundamental biological regenerators within these systems, performing multiple critical functions beyond nutrition—including air revitalization, water recycling, and waste processing [41]. The choice of candidate crops for space cultivation must address unique constraints such as limited volume, energy availability, microgravity conditions, and the need for high resource-use efficiency [40]. This comparative guide objectively evaluates plant cultivation systems and crop selection methodologies based on experimental data to inform researchers and scientists developing advanced life support technologies for future lunar and Martian missions.

Comparative Analysis of Space Plant Cultivation Systems

Multiple plant growth systems have been developed and tested for space applications, each with distinct technological approaches and research capabilities. The Vegetable Production System (Veggie) and Advanced Plant Habitat (APH) represent current NASA capabilities aboard the International Space Station, while ground-based test beds like the Laboratory Biosphere provide essential terrestrial research platforms [2] [42].

Table 1: Comparison of Plant Cultivation Systems for Space Applications

| System Feature | Veggie | Advanced Plant Habitat (APH) | Laboratory Biosphere |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Food production & crew well-being [2] | Advanced plant research [2] | Ground-based BLSS prototyping [42] |

| Automation Level | Low (requires crew operation) [2] | High (fully automated with remote monitoring) [2] | Variable (controlled environment research) [42] |

| Environmental Control | Basic (LED lighting, plant pillows) [2] | Comprehensive (CO₂, humidity, temperature, irrigation) [2] | Extensive (atmospheric composition, temperature) [42] |

| Monitoring Capabilities | Visual observation [2] | 180+ sensors, cameras [2] | Atmospheric dynamics monitoring [42] |

| Lighting System | Red-blue LEDs (magenta spectrum) [2] | Full-spectrum LEDs + white, far red, infrared [2] | High-pressure sodium lamps [42] |

| Research Applications | Crop trials, nutritional studies [2] | Gene expression, metabolic studies [2] | System-level BLSS validation [42] |

The selection between these systems depends on mission-specific requirements: Veggie provides practical food production capabilities, APH enables sophisticated plant biology research, and ground-based facilities allow for integrated BLSS testing before space deployment.

Crop Selection Methodologies and Performance Criteria

Selecting optimal crops for space environments requires systematic evaluation against multiple criteria. Research institutions including the Italian Space Agency (ASI) and University of Naples Federico II have developed algorithmic approaches to objectively compare candidate species [40].

Algorithmic Selection Framework

The crop selection algorithm employs a two-phase methodology that transforms qualitative characteristics into quantitative ranking scores [40]:

- Literature-Based Preliminary Screening: Initial evaluation of 39 genotypes against 25 parameters including growth characteristics, phytonutrient content, and mineral composition [40].

- Experimental Validation: Germination and cultivation trials for top-ranked species with precise measurement of metabolite production per day per square meter [40].

Data normalization enables direct comparison between diverse parameters: each measured parameter x is transformed using the formula Xᵢ = [xᵢ – min(x)] / [max(x) – min(x)], where minimum values equate to 0 and maximum values to 1. Parameters where lower values are desirable (e.g., nitrate content, growth period) are inverted in the normalization process [40].

Key Selection Criteria for Space Crops

The algorithm prioritizes specific plant traits essential for space cultivation [40]:

- Productivity Metrics: Growth rate, biomass yield, and harvest index

- Phytonutrient Profile: Concentrations of tocopherol, phylloquinone, ascorbic acid, polyphenols, and carotenoids

- Resource Efficiency: Water and nutrient utilization, lighting requirements

- Cultivation Practicality: Minimal growth space, disease resistance, handling time

Performance Comparison of Candidate Space Crops

Microgreens as High-Efficiency Space Crops

Microgreens have emerged as particularly promising candidates for space agriculture due to their compact size, rapid production cycle, and high phytonutrient density [40]. Experimental studies have demonstrated their superior performance compared to traditional crops across multiple efficiency metrics.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Select Microgreens for Space Cultivation

| Crop Species | Family | Growth Period (Days) | Key Phytonutrients | Productivity Score | Nutritional Score | Overall Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radish | Brassicaceae | 10-14 [40] | Glucosinolates, Anthocyanins [40] | High [40] | High [40] | 1 [40] |

| Savoy Cabbage | Brassicaceae | 10-14 [40] | Glucosinolates, Vitamin K [40] | High [40] | High [40] | 1 [40] |

| Mizuna Mustard | Brassicaceae | 14-21 [2] | Glucosinolates, Vitamin C [2] | Medium [2] | Medium-High [2] | 3-6 [40] |

| Red Russian Kale | Brassicaceae | 14-21 [2] | Carotenoids, Lutein [2] | Medium [2] | Medium-High [2] | 3-6 [40] |

| Lettuce | Asteraceae | 21-28 [2] | Folate, Vitamin K [2] | Medium [2] | Medium [2] | 3-6 [40] |

Traditional Crops for BLSS Applications

Larger traditional crops remain relevant for BLSS where higher biomass production is required. Studies in the Laboratory Biosphere facility have evaluated the performance of these crops under controlled environment conditions analogous to space habitats [42].

Table 3: Performance Data for Traditional Candidate Space Crops

| Crop | Planting Density (plants/m²) | Yield (g dry seed/m²) | Daily Productivity (g/m²/day) | CO₂ Range (ppm) | Temperature Regime (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|