From Lab to Field: Developing Smart Plant Sensors as Early Warning Systems for Crop Stress

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the development and application of smart plant sensors for the early detection of biotic and abiotic stress in crops.

From Lab to Field: Developing Smart Plant Sensors as Early Warning Systems for Crop Stress

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the development and application of smart plant sensors for the early detection of biotic and abiotic stress in crops. Targeting researchers and scientists in agritech and plant science, it explores the foundational principles of plant signaling molecules, details the methodological advances in nanosensor and wearable technology, examines the real-world challenges of technology adoption and data management, and validates these tools against traditional phenotyping methods. The synthesis offers a roadmap for translating cutting-edge sensor research into robust, field-deployable diagnostic systems that can revolutionize precision agriculture and crop protection strategies.

Decoding the Plant Stress Phenome: The Science of Early Stress Signaling

In modern agriculture, the early detection of plant stress is paramount for preventing significant yield losses and maximizing crop productivity. Plants subjected to biotic and abiotic stressors activate complex defense networks mediated by key signaling molecules long before visible symptoms appear. Among these, hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), salicylic acid (SA), and calcium (Ca²⁺) ions serve as crucial primary messengers that orchestrate physiological responses to environmental challenges [1] [2]. Understanding these signaling pathways provides the foundational knowledge required to develop innovative early warning systems that can alert farmers to stress conditions, enabling timely intervention and precise management decisions. This article explores the integrated roles of these key signaling molecules and details practical protocols for their detection and utilization in agricultural monitoring systems, framed within the context of developing real-time plant stress sensors for farming applications.

The Roles of Key Signaling Molecules in Plant Stress

Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) as a Primary Stress Messenger

Hydrogen peroxide functions as a critical signaling molecule in plant stress responses, despite being a reactive oxygen species (ROS). Under stress conditions from pests, drought, extreme temperatures, and pathogens, plants experience biochemical disruptions that lead to hydrogen peroxide production [1]. This compound serves dual roles: it acts as a direct stress marker indicating physiological imbalance, and as a intercellular signal that activates defense mechanisms [1] [3]. Research demonstrates that H₂O₂ application can induce biostimulant effects, enhancing crop development and growth in pepper plants when applied at specific concentrations [3]. The quantitative detection of H₂O₂ provides a direct window into a plant's stress status, making it an invaluable target for early monitoring systems.

Salicylic Acid (SA) in Defense Signaling and Stress Modulation

Salicylic acid is a phenolic phytohormone that regulates plant growth, development, and defense responses to environmental stressors [4]. SA serves as a master regulator of plant immunity, interacting with other signaling molecules and hormones to strengthen antioxidant systems and protect against oxidative damage [4]. Under drought conditions, exogenous SA application significantly improves chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (Fv/Fm and PIabs) in Cinnamomum camphora seedlings, enhances photosystem activity during mild drought, and mitigates damage from excessive light energy in photosynthetic institutions [4]. Transcriptomic analyses reveal that SA induces drought-resistant differentially expressed genes (DEGs), activates stress-related transcription factors (NAC, bHLH, ERF, MYB), and regulates genes involved in hormone signaling, thereby enhancing drought resilience [4]. Additionally, in Scrophularia striata, the combined application of SA and silicon elevated levels of protective compounds including β-carotene, α-tocopherol, and beta-amyrin under drought stress conditions [5].

Calcium (Ca²⁺) Ions as Ubiquitous Second Messengers

Calcium ions serve as versatile intracellular signaling molecules in numerous plant signaling pathways, playing crucial roles in growth, development, and stress responses [2]. When plants encounter environmental changes, the initial response involves an intracellular shift in free Ca²⁺ levels, triggering a signaling cascade essential for subsequent adaptive responses [2]. These Ca²⁺ changes exhibit spatiotemporal characteristics influenced by the nature, intensity, and duration of the stimulus, with decoding processes involving Ca²⁺ sensor proteins like calmodulins (CaMs), calcineurin B-like proteins (CBLs), and calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs) [2]. Research has identified that aluminum exposure specifically induces rapid, spatio-temporally defined biphasic Ca²⁺ signals in Arabidopsis roots and activates the Ca²⁺-dependent kinase CPK28, which phosphorylates the STOP1 transcription factor to enhance aluminum resistance [6]. The abundance and diversity of plant Ca²⁺ sensors, channels, and transporters enable the translation of Ca²⁺ signatures into specific physiological responses appropriate for different stress conditions [2].

Table 1: Quantitative Detection Parameters for Key Stress Signaling Molecules

| Signaling Molecule | Detection Method | Detection Time | Cost per Test | Key Stress Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Peroxide | Electrochemical patch sensor | <1 minute | <$1 USD | Pathogens, drought, temperature extremes, infections [1] |

| Salicylic Acid | Transcriptomic analysis + physiological assays | Days to weeks | >$100 USD | Drought, pathogen attack, oxidative stress [4] |

| Calcium Ions | Fluorescent dyes + imaging | Minutes to hours | $50-200 USD | Aluminum toxicity, salt stress, drought, biotic attacks [6] [2] |

Detection Technologies and Experimental Protocols

Hydrogen Peroxide Detection Protocol

Wearable Patch Sensor for Real-Time H₂O₂ Monitoring

The electrochemical patch sensor developed by Dong and colleagues provides a reliable method for real-time detection of hydrogen peroxide in live plants [1]. This protocol enables direct, non-destructive measurement of H₂O₂ levels from plant leaves with high sensitivity and rapid response time.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for H₂O₂ Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Microscopic plastic needles array | Forms base structure for leaf attachment | Flexible base with microscopic needles |

| Chitosan-based hydrogel mixture | Converts H₂O₂ changes to electrical signals | Contains enzyme for H₂O₂ reaction |

| Reduced graphene oxide | Conducts electrons through sensor | Enhances electrical conductivity |

| Enzyme (unspecified) | Reacts with H₂O₂ to produce electrons | Specific to H₂O₂ detection |

Procedure:

- Patch Fabrication: Create an array of microscopic plastic needles across a flexible base using standard microfabrication techniques [1].

- Hydrogel Coating: Coat the patterned surface with a chitosan-based hydrogel mixture containing an enzyme that reacts with hydrogen peroxide to produce electrons and reduced graphene oxide to conduct these electrons through the sensor [1].

- Plant Application: Attach patches directly to the underside of live plant leaves where stomatal density is higher, ensuring good contact with the epidermis [1].

- Measurement: Connect the patch to a portable potentiostat for electrochemical measurements. Apply a small voltage and measure the resulting current, which is directly proportional to the hydrogen peroxide concentration [1].

- Data Interpretation: Compare current levels between treated and control plants. Significantly higher electrical current indicates stress conditions, with levels directly related to the amount of hydrogen peroxide present [1].

Validation: The sensor's measurement of hydrogen peroxide should be confirmed through conventional lab analyses such as colorimetric or fluorometric assays to ensure accuracy [1]. Patches can typically be reused up to nine times before the microscopic needles lose their form [1].

Salicylic Acid Modulation Protocol

Exogenous SA Application for Enhanced Drought Resistance

This protocol outlines the methodology for applying salicylic acid to enhance drought tolerance in plants, as demonstrated in Cinnamomum camphora seedlings [4].

Materials:

- Salicylic acid (50 μM concentration)

- Handheld sprayer

- Soil moisture meter (e.g., ProCheck, DECAGON)

- Equipment for physiological measurements: Chlorophyll fluorometer, spectrophotometer for antioxidant assays

- RNA sequencing equipment for transcriptomic analysis

Procedure:

- Plant Material Preparation: Select uniform two-year-old seedlings with heights ranging from 85-100 cm and plant in pots containing standardized soil [4].

- Drought Stress Application: Establish three soil moisture levels: suitable moisture (75-80% saturated water-holding capacity), mild drought (50-55%), and severe drought (25-30%). Maintain these levels using the weighing method with daily moisture measurements [4].

- SA Treatment: Prepare 50 μM salicylic acid solution. Apply as foliar spray to designated plants until runoff, with control plants receiving distilled water only [4].

- Physiological Assessment:

- Measure chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (Fv/Fm and PIabs) to assess photosystem functionality

- Quantify oxidative stress markers (O₂⁻ and H₂O₂ contents)

- Assess antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, POD, CAT) [4]

- Transcriptomic Analysis:

- Extract RNA from leaf tissues

- Perform RNA sequencing and differential gene expression analysis

- Identify activated transcription factors (NAC, bHLH, ERF, MYB) and hormone signaling genes (AUX/IAA, PYR/PYL, A-ARRs, B-ARRs) [4]

Calcium Signaling Analysis Protocol

Monitoring Ca²⁺ Fluxes in Response to Aluminum Stress

This protocol details the approach for investigating calcium signaling in plant stress responses, specifically focusing on aluminum stress adaptation in Arabidopsis roots [6] [2].

Materials:

- Genetically encoded calcium indicators (e.g., GCaMP series)

- Confocal microscopy system

- Arabidopsis wild-type and mutant lines (e.g., cpk28 mutants)

- Aluminum treatment solutions

- Immunoprecipitation materials for phosphorylation studies

Procedure:

- Plant Preparation: Grow Arabidopsis plants under controlled conditions for consistent root development [6].

- Calcium Imaging:

- Express genetically encoded calcium indicators in root cells

- Mount seedlings in specialized chambers for live imaging

- Apply aluminum stress while monitoring spatiotemporal Ca²⁺ dynamics using confocal microscopy [6]

- Kinase Activation Assay:

- Extract proteins from root tissues following aluminum exposure

- Immunoprecipitate CPK28 and related signaling components

- Assess kinase activity through in vitro phosphorylation assays [6]

- Phosphorylation Mapping:

- Identify phosphorylation sites on STOP1 using mass spectrometry

- Generate phosphomimetic and phosphodead mutants for functional studies [6]

- Nuclear Localization Tracking:

- Fuse STOP1 with fluorescent tags

- Quantify nuclear accumulation under different stress conditions using fluorescence quantification [6]

Signaling Pathway Integration and Visualization

Plant stress signaling involves complex crosstalk between hydrogen peroxide, salicylic acid, and calcium pathways. The following diagram illustrates the integrated signaling network and how these molecules function synergistically to activate defense responses:

Integrated Stress Signaling Pathways in Plants

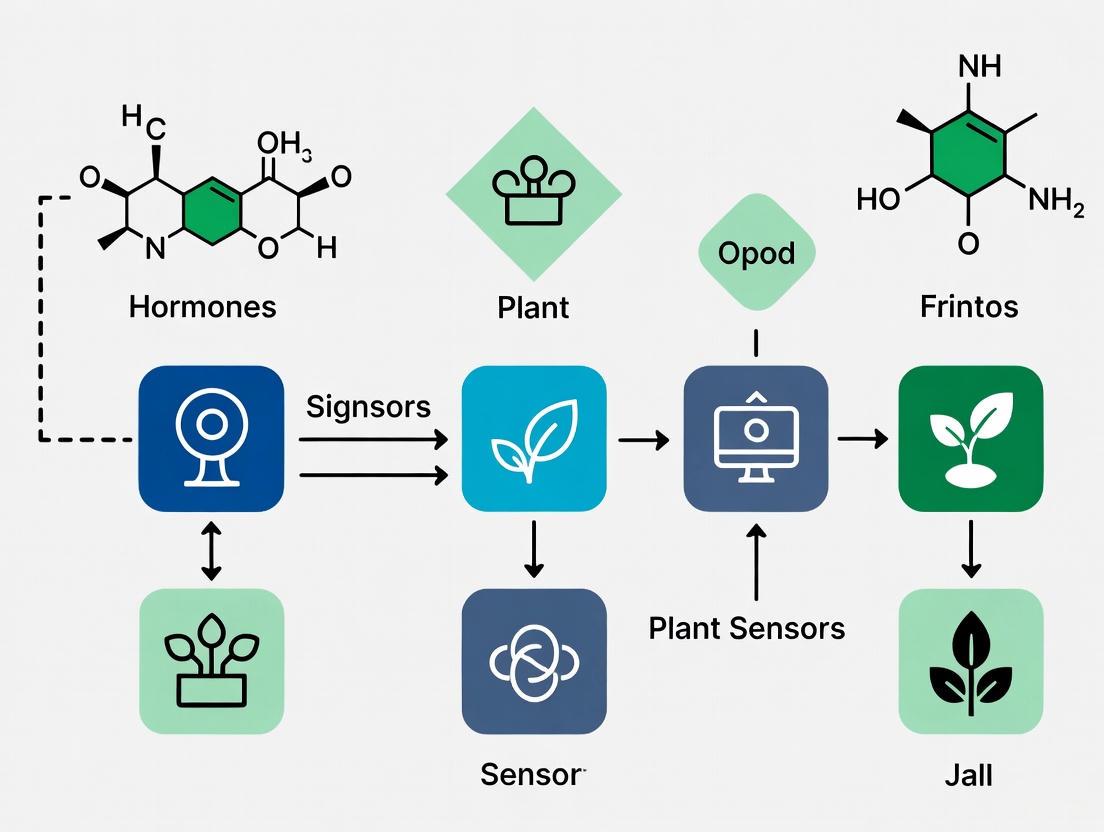

The experimental workflow for developing and validating plant stress sensors incorporates multiple approaches, from molecular analysis to field deployment, as shown in the following diagram:

Plant Stress Sensor Development Workflow

Agricultural Applications and Implementation

The translation of fundamental research on plant stress signaling molecules into practical agricultural applications has generated innovative sensor technologies with significant potential for early stress detection in farming operations.

Current Sensor Technologies for Stress Detection

Electrochemical H₂O₂ Patch Sensors Researchers have developed wearable patches for plants that quickly sense stress by detecting hydrogen peroxide, a key distress signal [1]. These patches feature microscopic plastic needles on a flexible base coated with a chitosan-based hydrogel mixture that converts small changes in hydrogen peroxide into measurable differences in electrical current [1]. The technology achieves direct measurements in under one minute for less than one dollar per test, making it practical for farmers to use for real-time disease and crop monitoring [1]. For both soybean and tobacco crops infected with bacterial pathogens, the sensor produced more electrical current on stressed leaves than on healthy ones, with current levels directly related to the amount of hydrogen peroxide present [1].

VOC Detection Systems Verdia Diagnostics is developing tiny, flexible sensors that attach to plant leaves and deliver continuous information about plant health by detecting volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by plants in real-time [7]. The system uses an array of VOC-reactive chemistries processed through machine learning algorithms that classify risky VOC emissions, essentially functioning as an "AI-enhanced smelling of stress for plants" [7]. This technology can distinguish between diseased and healthy plants approximately one week earlier than visual symptoms emerge, providing a significant lead time for intervention [7]. The company is currently focusing on controlled environment agriculture (greenhouses and vertical farms) where disease containment is particularly important [7].

Genetic Engineering Approaches InnerPlant utilizes genetic engineering to create crops that communicate stress by emitting optical signals detectable by field equipment or satellites [8]. Their technology codes crops to communicate within hours when stressed by pathogens, nutrient deficiencies, or drought [8]. These "living sensor" plants fluoresce in response to stress, with the information validated through laboratory analysis, field scouting, agronomic expertise, weather data, and advanced modeling to confirm issues like fungal disease in the network [8].

Implementation Considerations for Agricultural Use

Successful implementation of stress detection technologies in farming operations requires addressing several practical considerations:

Economic Validation Growers operate on tight margins and require clear return on investment for new technologies [7]. Demonstrating economic value through reduced yield losses and improved resource allocation is essential for adoption. Research indicates that pests and pathogens cause approximately 40% loss of global food crops, representing a significant economic burden that sensor technologies could help mitigate [7].

Integration with Existing Management Systems Sensor technologies must integrate seamlessly with existing farm management practices and decision support systems. This includes compatibility with precision agriculture platforms, irrigation control systems, and crop management software. The most successful implementations will combine sensor data with local agronomic expertise, weather data, and advanced modeling to provide actionable recommendations [8].

Scalability and Durability Agricultural technologies must withstand challenging environmental conditions while remaining cost-effective at scale. Sensor systems need to be robust enough for field deployment while maintaining sensitivity and accuracy. Current development efforts are focusing on enhancing reusability and durability to make technologies practical for farming applications [1].

Hydrogen peroxide, salicylic acid, and calcium ions represent crucial signaling molecules in plant stress responses that can be leveraged for developing innovative early warning systems in agriculture. The detection methodologies and experimental protocols detailed in this article provide researchers with practical approaches for investigating these signaling pathways and developing novel monitoring technologies. The ongoing translation of basic research on plant stress signaling into practical sensor technologies holds significant promise for enhancing agricultural productivity, reducing crop losses, and enabling more sustainable farming practices through precise, targeted interventions based on real-time plant physiological status.

Plant health monitoring is essential for understanding the impact of environmental stressors on crop production and for tailoring plant developmental and adaptive responses accordingly [9]. Plants are constantly exposed to different stressors, which can be categorized as biotic stresses (caused by living organisms like pathogens and pests) and abiotic stresses (caused by environmental factors like drought, heat, and salinity) [10]. These stressors pose a serious threat to plant survival and ultimately to global food security, with worldwide yield losses in major crops due to pathogens and pests estimated at 17-30% [11].

The development of robust large-scale plant scanning methods is key to successfully monitoring detrimental crop pathogens and assisting in their timely eradication [12]. However, a major limitation in plant health monitoring is that the subtle physiological alterations caused by disease reflect changes in plant physiological state that are commonly modulated by both biotic and abiotic confounding factors [12]. This review explores the distinct signaling pathways and spectral fingerprints associated with biotic versus abiotic stress conditions, focusing on advanced sensor technologies that enable early detection and differentiation of these stress types for agricultural applications.

Technical Background: Plant Stress Signaling Pathways

Plants have evolved complex signaling mechanisms to respond to environmental stressors. As sessile organisms, plants must cope with abiotic stresses such as soil salinity, drought, and extreme temperatures, while also defending against biotic stressors including pathogen infections and herbivore attacks [10]. Core stress signaling pathways involve protein kinases related to the yeast SNF1 and mammalian AMPK, suggesting that stress signaling in plants evolved from energy sensing [10].

Key Signaling Molecules in Plant Stress Responses

Plants respond to stress conditions through the production of diverse signaling molecules that regulate growth and adaptive responses. The exceptional responsiveness of plants to environmental cues is driven by diverse signaling molecules including calcium (Ca²⁺), reactive oxygen species (ROS), hormones, small peptides, and metabolites [9]. Additionally, other factors like pH also influence these responses [9].

Table 1: Key Plant Stress Signaling Molecules and Their Functions

| Signaling Molecule | Primary Function in Stress Response | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium (Ca²⁺) | Secondary messenger; transient fluctuations in concentration act as early signaling events | Genetically encoded Ca²⁺ indicators (GECIs) like Aequorin, Cameleon [9] |

| Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) | Secondary messengers in signal transduction; regulate defense and acclimation responses | H2DCFDA, dihydroethidium, Amplex red, boronate-based probes [9] |

| Salicylic Acid (SA) | Hormone involved in regulating growth, development, and response to stress; particularly important in pathogen defense | Carbon nanotube-based sensors, LC-MS [13] [9] |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Distress signal when under attack from insects or encountering stresses like bacterial infection | Carbon nanotube-based sensors, fluorescent probes [13] [9] |

| Abscisic Acid (ABA) | Phytohormone that elicits adaptive responses to drought and salt stress | ABACUS, ABAleon, SNACS sensors [9] [10] |

Diagram: Generalized Plant Stress Signaling Pathway

Figure 1: Generalized plant stress signaling pathway showing divergent responses to biotic and abiotic stressors. SA (salicylic acid) pathway is typically associated with biotic stress, while ABA (abscisic acid) pathway is associated with abiotic stress.

Differential Responses to Biotic vs. Abiotic Stress

Distinct Spectral and Physiological Fingerprints

Research using airborne spectroscopy and thermal scanning of areas covering more than one million trees of different species, infections, and water stress levels has revealed the existence of divergent pathogen- and host-specific spectral pathways that can disentangle biotic-induced symptoms [12]. These deviating pathways remain pathogen- and host-specific, revealing detection accuracies exceeding 92% across pathosystems [12].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Biotic vs. Abiotic Stress Responses

| Parameter | Biotic Stress Response | Abiotic Stress Response |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Signals | Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), effectors, herbivore-associated elicitors [14] | Osmotic stress, ionic imbalance, temperature extremes, redox changes [10] |

| Calcium Signatures | PTI: rapid transients returning to baseline in minutes; ETI: prolonged increase lasting hours [14] | Distinct signatures depending on stress type; hyperosmolality-induced calcium spikes [10] |

| Key Hormonal Pathways | Salicylic acid, jasmonic acid, ethylene [14] | Abscisic acid, cytokinins, auxins [10] |

| Spectral Indicators | Canopy temperature increase, reduced solar-induced fluorescence, altered xanthophyll cycle, species-specific pigment changes [12] | Stomatal conductance changes, photosynthetic efficiency alterations, uniform pigment changes [12] |

| Temporal Pattern | Specific time-dependent waves of H₂O₂ and SA depending on stress type [13] | Immediate response to physical stress factors; recovery following stress relief |

Molecular Differentiation of Stress Types

At the molecular level, plants generate distinctive signaling patterns that serve as fingerprints for different stress types. Research using carbon nanotube sensors has shown that plants produce hydrogen peroxide and salicylic acid at different timepoints for each type of stress, creating distinctive patterns that could serve as an early warning system [13]. For example:

- Heat, light, and bacterial infection all provoke salicylic acid production within two hours of the stimulus, but at distinct time points [13].

- Insect bites do not stimulate salicylic acid production at all but generate hydrogen peroxide signals [13].

- These chemical signatures represent a "language" that plants use to coordinate their response to stress [13] [15].

Experimental Protocols for Stress Differentiation

Protocol: Hyperspectral Imaging for Stress Type Discrimination

This protocol describes how to use airborne hyperspectral and thermal imaging to distinguish between biotic and abiotic stress in field conditions, based on methodologies that have successfully scanned over one million trees [12].

Materials:

- Hyperspectral imaging sensor (400-2500 nm range)

- Thermal infrared camera

- GPS and inertial measurement unit (IMU)

- Radiometric calibration targets

- Data processing workstation with specialized software

Procedure:

Experimental Setup and Calibration

- Mount sensors on airborne platform (aircraft or UAV)

- Perform radiometric calibration using calibration targets

- Synchronize GPS and IMU data with image acquisition

Data Acquisition

- Fly over target area during peak solar illumination (10:00-14:00 local time)

- Maintain appropriate spatial resolution (≤1 m² for tree-level detection)

- Capture coincident thermal and hyperspectral data

- Include reference areas of known health status

Data Processing

- Convert raw data to radiance and then to reflectance

- Apply geometric and atmospheric corrections

- Calculate multiple plant traits through radiative transfer model inversion:

- Solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence (SIF)

- Photochemical Reflectance Index (PRI)

- Normalized Pigment Chlorophyll Index (NPCI)

- Anthocyanin content

- Crop Water Stress Index (CWSI)

Machine Learning Analysis

- Apply multicollinearity analysis using variance inflation factor (VIF)

- Use machine learning algorithms to identify significant spectral traits

- Normalize importance for each spectral trait by the highest importance within each model

- Validate models with ground-truth data

Stress Differentiation

- Identify divergent spectral pathways specific to pathogens vs. water stress

- Quantify uncertainty in detection (<6% achievable for Xylella fastidiosa)

- Generate spatial maps of stress distribution and type

Protocol: Nanosensor Deployment for Real-Time Stress Monitoring

This protocol describes the use of carbon nanotube-based sensors for detecting hydrogen peroxide and salicylic acid signaling in plants, enabling real-time stress identification [13] [15].

Materials:

- Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNT)

- Specific polymers for wrapping (PEI for H₂O₂, PCD for salicylic acid)

- Near-infrared fluorescence spectrometer or camera

- Surfactant solutions for sensor application

- Control plants for baseline measurements

Procedure:

Sensor Preparation

- Suspend SWCNT in surfactant solutions

- Functionalize with specific polymers for target molecules

- Characterize sensor response using standard solutions

- Optimize concentration for plant application

Plant Application

- Dissolve sensors in appropriate solution

- Apply to underside of plant leaves using spray or gentle application

- Allow sensors to enter leaves through stomata

- Ensure residence in mesophyll layer

Stress Induction and Monitoring

- Expose plants to various stressors:

- Heat stress (35-40°C)

- High light intensity (1000-1500 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹)

- Bacterial infection (Pseudomonas syringae)

- Insect herbivory

- Monitor sensor fluorescence using near-infrared imaging

- Collect temporal data at 5-15 minute intervals

- Expose plants to various stressors:

Data Analysis

- Track fluorescence intensity changes over time

- Identify specific temporal patterns of H₂O₂ and SA for each stress

- Create fingerprint profiles for different stress types

- Establish thresholds for early warning

Diagram: Nanosensor Stress Detection Workflow

Figure 2: Workflow for nanosensor-based stress detection in plants, from sensor preparation to stress identification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Plant Stress Differentiation Studies

| Reagent/Sensor Type | Function | Example Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperspectral Imaging Systems | Captures spectral data across multiple wavelengths for physiological trait analysis | Differentiating Xylella infection from water stress in olive trees [12] | Non-invasive, canopy-level measurement, detects non-visual symptoms |

| Carbon Nanotube Sensors | Detect specific signaling molecules (H₂O₂, SA) in real-time | Identifying stress-specific chemical fingerprints in pak choi [13] | Real-time, in vivo monitoring, universal application across plant species |

| Genetically Encoded Ca²⁺ Indicators (GECIs) | Monitor calcium signaling dynamics in response to stresses | Studying early signaling events in plant-pathogen interactions [9] | Cell-specific resolution, non-destructive, compatible with live imaging |

| Wearable VOC Sensors | Monitor volatile organic compounds emitted by plants | Early detection of Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus before symptom appearance [16] | Continuous monitoring, detects infections 7+ days before visual symptoms |

| Portable Colorimetric Sensors | Field-based detection of plant pathogens through color changes | Detection of Phytophthora infestans in tomato leaves [16] | >95% accuracy, smartphone compatibility, field-deployable |

| Thermal Imaging Cameras | Measure canopy temperature changes associated with stress | Quantifying crop water stress index (CWSI) for irrigation management [12] | Detects stomatal closure, non-contact, large area coverage |

Application in Early Warning Systems for Farmers

The differentiation between biotic and abiotic stress fingerprints has direct applications in developing early warning systems for farmers. By detecting specific stress signatures before visible symptoms appear, farmers can implement targeted interventions, potentially saving crops and reducing unnecessary pesticide use [13] [16].

Implementation Framework

Sentinel Plants: Deploy sensor-equipped plants throughout agricultural fields to serve as early detectors of stress conditions [15].

Remote Sensing Platforms: Utilize UAVs equipped with hyperspectral and thermal sensors for regular field monitoring, enabling detection of stress patterns across large areas [12] [17].

Integrated Decision Support Systems: Combine sensor data with environmental information and predictive models to provide farmers with real-time alerts and management recommendations [16] [15].

Benefits to Agricultural Management

- Early Intervention: Detection of pathogen infection before visible symptoms appear allows for more effective containment measures [12] [16].

- Resource Optimization: Accurate differentiation between biotic and abiotic stress prevents unnecessary pesticide application when environmental factors are the primary issue [12].

- Precision Management: Targeted interventions based on specific stress identification reduce input costs and environmental impact [16] [17].

The ability to distinguish between biotic and abiotic stress responses in plants through their distinct molecular and spectral fingerprints represents a significant advancement in agricultural technology. By employing sophisticated sensor systems including hyperspectral imaging, carbon nanotube-based nanosensors, and thermal scanning, researchers and farmers can now identify specific stress types with unprecedented accuracy and timing. These technological advances, grounded in understanding the fundamental signaling pathways plants use to respond to different stressors, enable the development of effective early warning systems that can help secure global food production in the face of climate change and evolving pathogen threats. As these sensor technologies continue to advance and become more accessible, they hold the potential to revolutionize crop management practices and contribute to more sustainable agricultural systems worldwide.

The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and pH in Intracellular Communication

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and pH are fundamental intracellular signaling molecules that facilitate plant responses to environmental stressors. In the context of modern agriculture, understanding these signaling pathways is critical for developing plant health monitoring systems. These systems function as early warning mechanisms, allowing farmers to intervene before visible crop damage occurs. ROS, including hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and superoxide anion (O₂•⁻), act as crucial secondary messengers that regulate a wide array of physiological processes, from pathogen defense to programmed cell death [18]. Similarly, extracellular pH (pHe) dynamics influence root growth and immunity by modulating the activity of cell-surface peptide-receptor complexes [19]. This application note details the protocols and methodologies for quantifying these key signaling molecules, providing a scientific foundation for smart farming technologies that can detect abiotic and biotic stresses in crops.

ROS and pH Signaling: Core Mechanisms and Quantitative Profiles

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in Signaling

ROS function as double-edged swords in cellular physiology: at low levels, they mediate essential redox signaling pathways (redox biology), while at high levels, they cause oxidative damage [20]. The signaling capacity of different ROS varies significantly based on their chemical reactivity and half-lives.

Table 1: Properties and Signaling Roles of Major Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

| ROS Type | Chemical Formula | Half-Life | Primary Production Sites | Major Signaling Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Peroxide | H₂O₂ | A few seconds [21] | Chloroplasts, Peroxisomes, NADPH Oxidases (RBOHs) [18] | Systemic signaling, stomatal closure, pathogen defense [18] [20] |

| Superoxide Anion | O₂•⁻ | 10⁻⁶ – 10⁻³ s [21] | Mitochondrial ETC, Chloroplasts, NADPH Oxidases [18] [21] | Primarily intracellular; precursor for H₂O₂ [21] |

| Singlet Oxygen | ¹O₂ | 10⁻¹² – 3×10⁻⁶ s [21] | Chloroplasts (Photosystem II) [18] | Influences photosynthesis; can trigger programmed cell death [18] |

| Hydroxyl Radical | •OH | Extremely short [21] | Formed from H₂O₂ (Fenton reaction) [18] | Highly damaging; can cause cell wall loosening and DNA damage [18] |

| Peroxynitrite | ONOO⁻ | ~1 second [21] | Reaction of O₂•⁻ with nitric oxide (NO•) [21] | Can function as an intracellular messenger; modifies protein tyrosines [21] |

pH Dynamics in Intracellular Communication

The pH of various plant compartments is tightly regulated and forms a gradient from the alkaline endoplasmic reticulum (pH ~7.1-7.5) to the acidic vacuole (pH ~5.5-6.0) [22]. This gradient is essential for processes like enzyme activity and protein trafficking. Furthermore, the extracellular pH (pHe) is a dynamic signal. For instance, the acidic pHe in the root apical meristem is crucial for the interaction between the root growth factor RGF1 and its receptors (RGFRs). Pathogen-associated molecular patterns can trigger an alkalinization of the apoplast, which inhibits RGF1-RGFR binding but promotes the binding of plant elicitor peptides (Peps) to their receptors (PEPRs), thereby shifting the balance from growth to immunity [19] [23].

Experimental Protocols for Monitoring ROS and pH

Protocol: Whole-Plant Live Imaging of ROS

This protocol enables the non-invasive, real-time visualization of ROS dynamics in living plants, which is vital for understanding systemic stress signaling [24].

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Plant Material: Arabidopsis thaliana or tobacco plants.

- Nanosensors: Carbon nanotube-based sensors for H₂O₂ and salicylic acid [25].

- Imaging Setup: Confocal microscope or an infrared camera system.

Procedure:

- Sensor Preparation: Prepare a solution of carbon nanotube sensors. These sensors are tailored with specific polymers that change their fluorescent properties upon binding to target molecules like H₂O₂ or salicylic acid [25].

- Plant Infiltration: Apply the sensor solution to the underside of a plant leaf. The sensors enter the leaf tissue through the stomata and localize in the mesophyll layer where photosynthesis occurs [25].

- Stress Application: Expose the plant to a defined stressor (e.g., high light, heat, mechanical injury, or pathogen elicitors).

- Image Acquisition: At defined time points post-stress, capture fluorescence images using an infrared camera. The distinct fluorescent signatures of the sensors allow for the simultaneous monitoring of multiple signaling molecules [25].

- Data Analysis: Quantify the fluorescence intensity over time and across different plant regions. Different stresses produce unique temporal and spatial patterns of H₂O₂ and salicylic acid, creating a "fingerprint" for each type of stress [25].

Protocol: In Vivo Measurement of Intracellular pH

This protocol describes the use of genetically encoded ratiometric pH sensors to measure the luminal pH of specific endomembrane compartments in plant cells [22].

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Genetic Constructs: Plasmids containing pHluorin (a pH-sensitive GFP) fused to targeting sequences for specific organelles (e.g., ER, Golgi, trans-Golgi Network (TGN), prevacuolar compartments (PVC)) [22].

- Plant Material: Tobacco epidermal cells or Arabidopsis root cells for transient or stable transformation.

- Microscopy: Confocal laser scanning microscope capable of ratiometric imaging.

Procedure:

- Plant Transformation: Transform plants with the desired pHluorin-targeting construct via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation or other suitable methods.

- Sample Preparation: Mount a leaf or root from the transformed plant on a microscope slide for live-cell imaging.

- Ratiometric Imaging: For each compartment of interest, acquire fluorescence images at two different excitation wavelengths (typically 405 nm and 488 nm) while collecting emission at around 510 nm. The ratio of the emissions (510 nm/510 nm) is pH-dependent [22].

- pH Calibration: Generate a calibration curve by perfusing plant tissues with buffers of known pH (ranging from 5.5 to 8.0) containing ionophores to equilibrate intra- and extracellular pH. Measure the resulting fluorescence ratio at each known pH [22].

- pH Calculation: Use the calibration curve to convert the experimentally measured fluorescence ratios into precise pH values for each compartment.

Signaling Pathway Integration and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected network of ROS and pH signaling in plant stress response, which forms the mechanistic basis for early warning systems.

ROS-pH Signaling Network in Plant Stress Response

The experimental workflow for validating these pathways and developing agricultural sensors is outlined below.

Experimental Workflow for Sensor Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for ROS and pH Signaling Research

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Primary Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| H₂DCFDA | Chemical Fluorescent Probe | Detects general ROS levels; becomes fluorescent upon oxidation [9]. | Qualitative assessment of overall ROS burst in response to stress. |

| Carbon Nanotube (CNT) Nanosensors | Nanomaterial-based Sensor | Detects specific signaling molecules (e.g., H₂O₂, salicylic acid) in live plants [25]. | Real-time, non-invasive monitoring of stress-specific signatures in whole plants. |

| pHluorin-based GECIs | Genetically Encoded Sensor | Ratiometric measurement of pH in specific cellular compartments [22]. | Quantifying pH dynamics in the Golgi, TGN, or prevacuolar compartments. |

| Aequorin | Genetically Encoded Sensor | Detects cytosolic calcium (Ca²⁺) waves [9]. | Studying Ca²⁺ signaling downstream of ROS and pH perception. |

| SOSG (Singlet Oxygen Sensor Green) | Chemical Fluorescent Probe | Specific detection of singlet oxygen (¹O₂) [9]. | Monitoring photo-oxidative stress in chloroplasts. |

| RBOH Inhibitors (e.g., DPI) | Pharmacological Inhibitor | Inhibits NADPH oxidases, key enzymes for apoplastic ROS production [18]. | Elucidating the specific role of RBOH-derived ROS in a signaling pathway. |

| V-ATPase Inhibitors (e.g., Concanamycin A) | Pharmacological Inhibitor | Disrupts proton gradients in endomembranes [22]. | Investigating the role of organelle acidification in protein trafficking and signaling. |

Application in Agriculture: Towards an Early Warning System

The integration of these fundamental signaling principles with sensor technology is transforming precision agriculture. Research has demonstrated that plants produce distinctive temporal patterns of H₂O₂ and salicylic acid in response to different stressors such as heat, intense light, or pathogen attack [25]. By deploying nanosensors that detect these molecules, farmers can gain real-time insights into crop health status. This system functions as an early warning mechanism, identifying the nature and onset of stress before visible symptoms like wilting or chlorosis appear [25]. This allows for timely and precise interventions, such as targeted irrigation, shading, or pesticide application, thereby minimizing crop loss and optimizing resource use. The ultimate goal is the development of a robust smart farming framework where plants themselves communicate their physiological status directly to growers.

The foundation of modern precision agriculture rests on the ability to detect plant stress long before visible symptoms manifest. Traditional monitoring methods, which rely on visual identification of crop damage, often provide warnings too late for effective intervention, resulting in significant yield losses [26]. The emerging paradigm shift toward molecular-level detection leverages plant sensors that translate biochemical signals into actionable data for farmers [27] [28]. This approach aligns with a broader thesis on developing robust plant sensor networks that serve as early warning systems, enabling preemptive management strategies to sustain global food security.

Plant stress responses initiate at the molecular level through complex signaling cascades. When crops face biotic or abiotic threats, they produce specific signaling molecules as part of their defense mechanisms [28]. These molecular signatures, detectable through advanced sensor technology, create distinctive patterns that serve as fingerprints for different stress types—from pathogen attacks to environmental pressures [28]. By correlating these molecular events with subsequent phenotypic symptoms, researchers can establish predictive models that translate sensor data into diagnostic and prognostic information for crop management.

Results: Quantitative Analysis of Molecular Signatures

This section presents experimental data demonstrating the relationship between early molecular events and later visible symptoms across different stress conditions. The quantitative measurements were obtained using plant nanosensors deployed on pak choi (Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis) under controlled stress induction protocols.

Table 1: Temporal Dynamics of Molecular Stress Markers Following Stress Induction

| Stress Type | H₂O₂ Peak Concentration (Time) | Salicylic Acid Peak Concentration (Time) | First Visible Symptoms (Time) | Symptom Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heat Stress | 45-55 μM (15-20 min) | 3.2-3.8 μM (2-2.5 hr) | 24-36 hr | Leaf curling, chlorosis |

| High Light Intensity | 40-50 μM (10-15 min) | 2.8-3.5 μM (1.5-2 hr) | 12-18 hr | Leaf bleaching, necrosis |

| Bacterial Infection | 60-70 μM (20-30 min) | 4.0-5.2 μM (3-4 hr) | 48-72 hr | Water-soaked lesions, wilting |

| Insect Herbivory | 50-60 μM (5-10 min) | Not detected | 6-12 hr | Irregular leaf damage, frass |

The data reveal that hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) serves as a universal first responder to all stress types, with concentrations rising within minutes of stress induction and returning to baseline within approximately one hour [28]. In contrast, salicylic acid production follows a more selective and delayed pattern, with no detectable response to insect herbivory [28]. The consistent delay between molecular signaling (minutes to hours) and visible symptoms (hours to days) highlights the critical intervention window enabled by sensor-based detection.

Table 2: Sensor Performance Characteristics for Stress Biomarker Detection

| Sensor Target | Detection Mechanism | Time to Result | Detection Limit | Plant Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactive Oxygen Species | Biohydrogel-based detection | < 3 minutes [27] | ~5 μM [27] | Soybean, Pak Choi [27] [28] |

| Salicylic Acid | Polymer-wrapped carbon nanotubes | < 5 minutes [28] | ~0.8 μM [28] | Pak Choi, Tobacco [28] |

| Bean Pod Mottle Virus | Nanocavity binding | < 2 minutes [27] | ~10 virus particles/μL [27] | Soybean [27] |

| Dicamba Herbicide | Direct chemical sensing | Real-time [27] | ~0.1 ppm [27] | Soybean [27] |

The sensor performance data demonstrate the capability for rapid, on-site analysis of plant health status. The detection limits for all sensors fall within biologically relevant ranges, allowing identification of stress signals before irreversible damage occurs [27] [28]. The compatibility across various plant species suggests broad applicability of these sensing platforms with minimal modification required for different crops.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Nanosensor Application and Molecular Signature Profiling

This protocol describes the procedure for applying nanosensors to plant leaves and monitoring molecular stress signatures in response to various stressors, adapted from the MIT/SMART research team methodology [28].

Materials Required

- Carbon nanotube-based sensors for H₂O₂ and salicylic acid detection

- Solution buffer (10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4)

- Infrared imaging system with appropriate filters

- Controlled environment growth chamber

- Pak choi or soybean plants at 4-6 leaf stage

- Micropipettes and sterile tips

Procedure

- Sensor Solution Preparation: Suspend H₂O₂ and salicylic acid sensors in buffer solution at 1 mg/mL concentration. Sonicate for 30 minutes to ensure homogeneous dispersion.

- Plant Preparation: Select uniformly developed plants. Gently clean the abaxial (underside) of leaves with distilled water to remove debris.

- Sensor Application: Apply 100 μL of sensor solution to the abaxial surface of each leaf, ensuring coverage of approximately 4 cm². The sensors enter leaves through stomata and localize in the mesophyll layer [28].

- Acclimation Period: Allow treated plants to stabilize for 12 hours under optimal growth conditions before stress induction.

- Stress Induction: Apply one of four stress conditions:

- Heat Stress: Transfer plants to growth chamber maintained at 38°C

- Light Stress: Expose plants to 1500 μmol photons/m²/s

- Bacterial Infection: Inoculate with Pseudomonas syringae (10⁸ CFU/mL)

- Insect Herbivory: Place 5-7 Pieris rapae larvae on each plant

- Signal Monitoring: Capture fluorescent signals using infrared camera at 5-minute intervals for the first 2 hours, then at 15-minute intervals for 24 hours.

- Data Analysis: Quantify signal intensity using image analysis software. Normalize values to pre-stress baseline. Generate temporal profiles for each stress condition.

Critical Step: Ensure consistent environmental conditions during monitoring, as temperature and humidity fluctuations can affect signal intensity.

Note: This protocol enables simultaneous monitoring of multiple plants, making it suitable for high-throughput screening of stress responses.

Protocol 2: Sensor Validation Against Molecular Diagnostics

This protocol describes the validation of sensor readings against established molecular techniques to confirm stress pathway activation, incorporating multi-omics verification approaches [26] [29].

Materials Required

- TRIzol reagent for RNA extraction

- PCR equipment and reagents

- Salicylic acid ELISA kit

- Hydrogen peroxide colorimetric assay kit

- Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry system

- Plant tissue grinder

Procedure

- Parallel Sampling: Collect leaf tissue samples from sensor-monitored plants at predetermined intervals post-stress induction (15 min, 1 hr, 3 hr, 6 hr, 24 hr).

- Molecular Analysis:

- Gene Expression: Extract total RNA, synthesize cDNA, and perform qPCR for pathogenesis-related (PR) genes using standard protocols [26].

- Protein Analysis: Prepare protein extracts and assess PR protein accumulation via western blot.

- Phytohormone Quantification: Measure salicylic acid levels using ELISA and LC-MS.

- Oxidative Stress Markers: Quantify H₂O₂ using colorimetric assays and antioxidant enzyme activities.

- Data Correlation: Statistically correlate sensor signals with molecular marker levels using Pearson correlation coefficients.

- Validation Criteria: Establish threshold sensor values that correspond to significant molecular changes (p < 0.05).

Troubleshooting Tip: If sensor signals do not correlate with molecular markers, verify sensor specificity by testing with known concentrations of target analytes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Plant Stress Signaling Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanotube Sensors | Detect specific signaling molecules via fluorescence emission | Real-time monitoring of H₂O₂ and salicylic acid in living plants [28] |

| Biohydrogel Sensors | Measure reactive oxygen species through sensitive polymer matrix | Early detection of oxidative stress in soybean plants [27] |

| Virus-Specific Nanocavities | Selective binding and identification of viral pathogens | Detection of bean pod mottle virus in soybeans [27] |

| CRISPR-Based Assays | Ultrasensitive nucleic acid detection for pathogen identification | Field-deployable diagnosis of Phytophthora infestans [26] |

| LAMP Kits | Isothermal amplification for rapid pathogen detection | On-site screening of Fusarium species in grains [26] |

| Hyperspectral Imaging Systems | Non-destructive monitoring of biochemical changes in plants | Detection of disease-induced changes in stored produce [26] |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Plant Stress Signaling Pathway

Plant Stress Signaling Pathway: This diagram illustrates the progression from stress perception to visible symptoms, highlighting the molecular events detectable by plant sensors long before visual symptoms appear.

Experimental Workflow for Sensor Validation

Sensor Validation Workflow: This experimental workflow outlines the process for correlating sensor signals with molecular markers to validate sensor accuracy and establish diagnostic thresholds.

Discussion

The integration of plant sensor technology with molecular signature analysis represents a transformative approach to agricultural management. The data presented demonstrate that distinct chemical fingerprints for different stress types enable precise diagnosis of plant health issues before irreversible damage occurs [28]. This molecular-level insight provides a scientific foundation for developing decision support systems that translate sensor data into actionable management recommendations for farmers.

The practical implementation of these technologies faces several challenges, including sensor durability under field conditions, cost-effectiveness for widespread deployment, and data interpretation for diverse crop species [27] [26]. Future research directions should focus on developing multi-analyte sensor arrays that can simultaneously monitor multiple signaling molecules, creating more robust diagnostic capabilities [27]. Additionally, the integration of sensor data with machine learning algorithms will enhance predictive accuracy and enable more precise intervention timing [26]. As these technologies mature, they will increasingly form the backbone of intelligent agricultural systems that proactively maintain crop health, ultimately contributing to global food security through reduced losses and optimized input use.

Next-Generation Sensing Platforms: From Nanosensors to Plant Wearables

Carbon Nanotube-Based Sensors for Real-Time Metabolite Detection

Carbon nanotube (CNT)-based sensors represent a frontier technology in electrochemical sensing, enabling real-time, in vivo monitoring of metabolites with high accuracy and versatility. These sensors utilize a novel architecture where single-wall carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) function as electrodes that support tandem metabolic pathway-like reactions, linking them to oxidoreductase-based electrochemical analysis [30]. This design fundamentally broadens the range of detectable metabolites and overcomes key limitations of traditional analytical methods like mass spectrometry, which are restricted to ex vivo analysis and provide only metabolic snapshots rather than dynamic, continuous data [30]. For agricultural research, particularly in developing early warning systems for farmers, this technology offers transformative potential by allowing continuous monitoring of plant stress signals before visible symptoms appear.

The core innovation lies in integrating multifunctional enzymes and cofactors directly with SWCNTs, creating a system that sequentially transforms metabolites into detectable electrochemical signals. The CNTs provide an exceptional platform due to their high surface-to-volume ratio, favorable electronic properties, fast electron transfer rate, and biocompatibility, which collectively enhance sensor performance and sensitivity while enabling greater enzyme loading and faster reaction rates [30] [31]. This direct integration of cofactors supports self-mediation, eliminating the need for additional chemical mediators, reducing electrode fouling, and enhancing compatibility with biological environments—critical advantages for both plant and in vivo applications [30].

Experimental Protocols

Sensor Fabrication and Functionalization

CNT Synthesis via Pulsed AC Arc Discharge Method:

- Apparatus Setup: Two hollow metallic rods are positioned head-to-head with a precise gap on a glassy substrate. The electrodes are connected to a high-voltage AC source (typically 50 Hz) with maximum electrical power input of 0.9 kW [31].

- Process Parameters: A high-density polyethylene (HDPE) substrate serves as the carbon source due to its favorable properties and low cost. When voltage is applied between electrodes, electrons travel between cathode and anode, triggering an electrical arc [31].

- CNT Formation: The resulting thermal plasma contains carbon ions, H₂, CO₂, and CO gases. The input electrical field drives carbon ions to the cathode surface, where they quench and form CNTs [31].

- Validation: Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrum analysis confirm successful CNT synthesis and quality [31].

Sensor Functionalization for Metabolite Detection:

- Purification Enhancement: Reflux CNTs in nitric acid followed by dispersion in Dimethylformamide (DMF), which significantly improves sensitivity compared to Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) dispersion [32].

- Optimal Concentration: Use 25 mg of CNT per 100 ml of DMF for optimal sensitivity [32].

- Lipid Exchange Envelope Penetration (LEEP): Apply the LEEP technique to incorporate sensors into plant leaves. This method designs nanoparticles that penetrate plant cell membranes, enabling embedding of functionalized CNTs directly into leaf structures [33].

- Probe Immobilization: For specific targeting, immobilize recognition elements (enzymes, ss-DNA) through physical adsorption, covalent bonding using functional groups, or avidin-biotin interactions to create specific metabolite detection capabilities [31].

Metabolite Sensing and Signal Measurement

Detection Mechanism Activation:

- Stress Application: Induce plant stress through mechanical wounding, pathogen infection, or light/heat damage to trigger hydrogen peroxide signaling waves [33].

- Signal Propagation Monitoring: Observe hydrogen peroxide release from wound sites generating waves that spread along leaves, similar to neuronal electrical impulses. As plant cells release hydrogen peroxide, they trigger calcium release in adjacent cells, stimulating further hydrogen peroxide production in a propagated wave [33].

Electrochemical Measurement:

- Configuration: Utilize a conventional three-electrode setup (working, reference, and counter electrodes) or a chemiresistor/FET configuration where CNTs serve as conducting channels between source and drain electrodes [31].

- Instrumentation: Measure current-voltage (I-V) characteristics using an Autolab system or similar electrochemical workstation with applied voltage typically ranging 0-2V [31].

- Data Acquisition: Capture near-infrared fluorescence produced by sensors using a small infrared camera connected to a Raspberry Pi computer. Record signal changes before and after metabolite detection events [33].

- Signal Processing: Plot current and voltage data using analytical software (e.g., Matlab) to quantify conductance changes resulting from metabolite binding events [31].

Application in Plant Stress Monitoring

CNT-based sensors demonstrate exceptional capability for early detection of plant stress, a crucial application for developing farmer early warning systems. These sensors detect hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) signaling waves that plants generate when responding to stresses such as injury, infection, light damage, or pathogen attack [33]. This hydrogen peroxide functions as a plant distress signal, stimulating leaf cells to produce compounds that facilitate damage repair or predator defense.

The technology has been successfully validated across eight different plant species, including spinach, strawberry plants, arugula, lettuce, watercress, and sorrel, demonstrating its broad applicability [33]. Each species produces distinctive hydrogen peroxide waveforms—the characteristic shape generated by mapping hydrogen peroxide concentration over time—which encode specific information about both the plant species and stress type [33]. This waveform differentiation enables precise identification of stress nature and severity before visible symptoms manifest, providing critical early warning capabilities.

Agricultural researchers can leverage this technology to screen plant varieties for enhanced stress resistance, monitor pathogen responses including fungi and bacteria causing devastating crop diseases, and study shade avoidance syndrome in high-density planting [33]. By intercepting and decoding these early stress signals, the sensors provide the fundamental technological platform for developing proactive agricultural management systems that alert farmers to emerging threats, enabling timely interventions before significant crop damage occurs.

Performance Data and Technical Specifications

Table 1: Performance Metrics of CNT-Based Metabolite Sensors

| Performance Parameter | Reported Value | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Detectable Metabolites | Up to 12 distinct metabolites | Tandem metabolic reaction-based system [30] |

| Signal-to-Noise Improvement | Up to 100-fold increase | Compared to previous sensor technologies [30] |

| Operational Stability | Several days of reliable function | Continuous monitoring applications [30] |

| Gauge Factor (Sensitivity) | 3.66-10.25 (depending on purification) | Strain sensing applications; varies with preparation [32] |

| Optimal CNT Concentration | 25 mg/100 ml DMF | Provides highest sensitivity [32] |

| Detection Method | Electrochemical/optical | Hydrogen peroxide detection in plants [33] |

Table 2: Sensor Response Variation with CNT Preparation Parameters

| Preparation Factor | Condition | Impact on Sensitivity (Gauge Factor) |

|---|---|---|

| Purification Method | Nitric acid reflux + DMF | 7.71 [32] |

| Purification Method | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | 3.66 [32] |

| Aspect Ratio | Higher (3.8) | 5.32 [32] |

| CNT Type | Semiconducting | Better sensitivity than metallic [31] |

Signaling Pathways and Detection Workflows

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs) | Conducting channel for electron transfer | High aspect ratio (≥3.8) recommended; semiconducting type preferred for better sensitivity [31] [32] |

| Dimethylformamide (DMF) | CNT dispersion solvent | Superior to SDS for sensitivity; use 25mg CNT/100ml optimal concentration [32] |

| Nitric Acid | CNT purification | Reflux treatment significantly enhances sensor sensitivity [32] |

| High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) | Carbon source for CNT synthesis | Low-cost substrate with favorable properties for arc-discharge synthesis [31] |

| Multifunctional Enzymes/Oxidoreductases | Biorecognition elements | Enable tandem metabolic pathway-like reactions for metabolite detection [30] |

| Cofactors (NAD+/NADP+) | Electron transfer mediation | Integrated with CNTs for self-mediation, eliminating need for external mediators [30] |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | Primary signaling molecule | Target analyte for plant stress detection; indicates mechanical injury, pathogen attack [33] |

Flexible and Wearable Plant Sensors for In-Situ Monitoring

Plant health is inextricably linked to global food security, with plant diseases alone causing annual global crop losses of 20–40% [34]. The emergence of flexible and wearable plant sensors represents a transformative advancement in precision agriculture, enabling real-time, in-situ monitoring of physiological biomarkers for early warning systems [34]. Unlike traditional rigid sensors that can damage plant tissues and cause biological rejection, flexible sensors exhibit excellent mechanical properties and biocompatibility, allowing seamless integration with crops for continuous health assessment [35] [36]. This application note details the protocols and implementation frameworks for deploying these sensors as critical components in early warning systems for farmers, facilitating timely interventions against biotic and abiotic stresses.

Flexible wearable plant sensors are typically structured in a three-layer sandwich arrangement, comprising a flexible substrate, a sensing element, and an encapsulation material [34]. These sensors are classified into three primary functional categories based on their monitoring targets: plant growth variables (e.g., stem diameter, fruit size), plant microclimates (e.g., humidity, temperature), and plant stress indicators (e.g., volatile organic compounds) [34]. The successful implementation of these sensors within agricultural systems provides a technological foundation for early warning mechanisms by converting biological signals into electrical data that can be analyzed to detect stress conditions before visible symptoms appear [37].

Table 1: Classification of Flexible Wearable Plant Sensors

| Sensor Category | Measured Parameters | Early Warning Capability | Common Sensing Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Growth Sensors | Stem diameter, fruit enlargement, leaf movement [35] | Detection of growth anomalies indicating stress conditions [37] | CNT/graphite, graphene, polyaniline [34] |

| Microclimate Sensors | Temperature, humidity, vapor pressure deficit [34] | Microenvironmental conditions predisposing plants to stress [37] | Graphene oxide (GO), ZnIn₂S₄ (ZIS) nanosheets [34] |

| Stress Detection Sensors | Volatile organic compounds (VOCs), sap flow, pesticides [34] [37] | Early identification of pathogen attacks, water stress, contamination [34] | Reduced graphene oxide (rGO), MXene, functionalized ligands [34] |

Monitoring Modalities and Experimental Protocols

Plant Growth Monitoring

Operating Principle: Wearable strain sensors for growth monitoring operate primarily on the mechanism of resistance signal change. As the plant organ expands, it induces mechanical strain on the sensor, which causes measurable changes in electrical resistance through deformation of the conductive sensing material [34].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Representative Growth Sensors

| Sensing Material | Substrate | Sensitivity/Range | Stability | Target Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deposited graphite ink [34] | Latex | Strain range: 1% to 8% [34] | 7 days continuous operation [34] | Solanum melongena L. and Cucurbita pepo growth [34] |

| CNT/graphite composite [34] | Latex | 3 mm/min growth rate detection [34] | 30 minutes continuous monitoring [34] | General plant stem expansion [34] |

| Graphene-based composite [34] | Ecoflex | Resistance: 3.9/2.9 kΩ/mm [34] | 336 hours (14 days) [34] | Fruit growth monitoring [34] |

Experimental Protocol: Stem Diameter Monitoring

- Sensor Fabrication: Prepare conductive ink by dispersing graphite flakes (45% by weight) in a polymer binder solution. Deposit the ink onto a pre-stretched latex substrate (0.5 mm thickness) using direct writing or drop-casting methods [34].

- Sensor Calibration: Mount the sensor on a calibrated expansion apparatus and measure resistance changes while applying known displacements. Generate a calibration curve relating resistance change to radial expansion [34].

- Field Deployment: Gently wrap the sensor around the plant stem at the measurement location. Ensure conformal contact without constricting natural growth. Use medical-grade adhesive tape at the ends for fixation, avoiding complete circumscription of the stem [34].

- Data Acquisition: Connect sensor electrodes to a portable data acquisition system with wireless transmission capability. Program the system to record resistance measurements at 10-minute intervals. Transmit data to a central monitoring platform for analysis [34].

- Data Interpretation: Establish a baseline growth pattern under optimal conditions. Deviations from this baseline (reduced growth rates) may indicate emerging stress conditions, triggering alerts in the early warning system [37].

Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) Detection for Stress Monitoring

Operating Principle: Plants emit specific VOC profiles in response to biotic and abiotic stresses. Wearable VOC sensors employ chemiresistive sensing mechanisms, where functionalized sensing materials (e.g., rGO with various ligands) undergo resistance changes upon adsorption of target VOCs [34] [37]. More than 1,700 VOCs from 90 different plant species have been identified, serving as chemical indicators of plant health status [37].

Experimental Protocol: Early Disease Detection

- Sensor Selection: Utilize a chemiresistive sensor array with multiple functionalized sensing elements. Each element should be functionalized with different ligands (e.g., metal nanoparticles, organic compounds) to detect a broad spectrum of VOCs [34].

- Sensor Placement: Mount the VOC sensor array in proximity to plant organs most likely to emit stress signals (typically leaves). Ensure adequate air circulation around the sensor while protecting it from direct rainfall [37].

- Baseline Establishment: Monitor and record VOC profiles from healthy plants over a 5-7 day period to establish a normalized baseline signature under non-stress conditions [37].

- Continuous Monitoring: Operate sensors continuously with data recording at 15-minute intervals. Implement diurnal normalization to account for natural daily variations in VOC emissions [37].

- Anomaly Detection: Apply machine learning algorithms to identify statistically significant deviations from the established baseline. Correlate specific VOC signatures with known stress conditions (e.g., pathogen presence, nutrient deficiency) through pattern recognition [37].

- Alert Thresholds: Set multi-level alert thresholds based on deviation magnitude and persistence. Implement farmer notifications through mobile applications when thresholds are exceeded [37].

Table 3: VOC Biomarkers for Stress Detection

| Stress Type | Key VOC Biomarkers | Detection Timeline | Sensor Technology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogen Attack | Terpenoids, green leaf volatiles [37] | 24-48 hours before visual symptoms [37] | rGO functionalized with metal nanoparticles [34] |

| Herbivore Damage | Jasmonates, specific terpene blends [37] | Within hours of damage [37] | Ligand-functionalized chemiresistive sensors [34] |

| Drought Stress | Methanol, saturated aldehydes [37] | 2-3 days before wilting [37] | MXene-based sensor arrays [34] |

Microclimate Monitoring

Operating Principle: Microclimate sensors simultaneously track multiple environmental parameters including humidity, temperature, and light intensity at the plant-canopy level. These parameters directly influence plant physiological processes and can predispose plants to stress conditions [34] [37].

Experimental Protocol: Integrated Microclimate Assessment

- Sensor Deployment: Install flexible multimodal sensors at strategic locations within the crop canopy to capture microenvironmental variations. Position sensors to represent different canopy levels and orientations [37].

- Parameter Correlation: Correlate microclimate data with plant physiological responses. For instance, high vapor pressure deficit (VPD) conditions combined with low sap flow rates indicate imminent drought stress [34].

- Predictive Modeling: Integrate microclimate data with plant response models to predict stress development. For example, specific temperature and humidity combinations can forecast pathogen favorable conditions before disease onset [37].

- Intervention Triggers: Establish microenvironmental thresholds that automatically trigger interventions (e.g., irrigation activation, shade adjustment) through connected agricultural systems [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Flexible Plant Sensor Research

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Flexible Substrates | Base material providing mechanical flexibility and stretchability [34] | Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), Ecoflex, polyimide (PI), latex, Buna-N rubber [34] |

| Conductive Nanomaterials | Sensing elements that transduce biological signals to electrical signals [34] | Graphene, carbon nanotubes (CNT), reduced graphene oxide (rGO), MXene [34] |

| Functionalization Ligands | Molecular recognition elements for specific analyte detection [34] | Metal nanoparticles, organic compounds, biological receptors for VOC sensing [34] |

| Encapsulation Materials | Protective layers ensuring sensor stability in environmental conditions [34] | PDMS, Ecoflex, SU-8 photoresist [34] |

| Conductive Inks | Patternable conductive formulations for sensor fabrication [34] | Graphite ink (45% by weight in polymer binder), CNT/graphite composites [34] |

Implementation Framework for Early Warning Systems

The effective deployment of flexible wearable sensors as early warning systems requires careful consideration of several implementation factors. Sensor networks must be designed to provide comprehensive coverage of agricultural fields while maintaining reliable data transmission through wireless connection protocols [34]. Power management remains a critical consideration, with emerging solutions including biodegradable batteries and energy harvesting systems that extend operational lifetimes [35]. Data analytics platforms must integrate sensor outputs with agricultural models to transform raw measurements into actionable alerts for farmers [37].

Flexible and wearable plant sensors represent a paradigm shift in agricultural monitoring, moving from reactive to proactive farm management through continuous, in-situ health assessment. The protocols and implementation frameworks detailed in this application note provide researchers with standardized methodologies for deploying these technologies within early warning systems. As these sensors continue to evolve through advances in materials science, data analytics, and wireless technologies, their integration into precision agriculture frameworks will become increasingly sophisticated, offering farmers unprecedented capabilities for protecting crop health and optimizing productivity. Future developments should focus on enhancing sensor durability, reducing costs, and improving the specificity of stress detection algorithms to further strengthen early warning capabilities.

Integration of Micro-Nano Technology and Fiber Optics (e.g., FBG)

The integration of Micro-Nano Technology with Fiber Optic Sensing, particularly Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) systems, creates powerful tools for developing advanced plant sensors. These systems enable precise, real-time monitoring of physiological and environmental parameters in agricultural settings.

Fiber Bragg Grating (FBG) Fundamentals: An FBG is a periodic microstructure inscribed into the core of an optical fiber that reflects a specific wavelength of light while transmitting all others [38]. The central operating principle is defined by the Bragg condition: λB = 2neff · Λ, where λB is the Bragg wavelength, neff is the effective refractive index of the fiber core, and Λ is the grating period [39] [38]. When the fiber experiences strain or temperature changes, both neff and Λ are altered, resulting in a measurable shift in λB [39]. This shift is the fundamental mechanism that allows FBGs to function as highly sensitive transducers.

Micro-Nano Fiber (MNF) Technology: MNFs are optical fibers with diameters reduced to the micro- or nano-scale, close to or below the wavelength of the light they guide [40]. This miniaturization creates a strong evanescent field that extends significantly beyond the fiber's physical surface [41] [40]. This property makes MNFs exceptionally sensitive to changes in the surrounding environment, such as the presence of specific biochemical compounds or variations in refractive index, which is crucial for detecting plant stressors.

Synergistic Integration: Combining FBGs with micro-nano functionalization enhances their capabilities. This involves applying specialized micro-nanostructures or functional coatings (e.g., pH-sensitive gels, hygroscopic polymers, or bio-recognition elements) to the optical fiber [39] [41]. These coatings transduce a target environmental or biochemical stimulus (e.g., soil moisture, sap pH, or pathogen presence) into a mechanical strain or a change in the local refractive index, which is then precisely measured by the FBG as a wavelength shift [39].

Agricultural Application Notes for Early Warning Systems

The following applications demonstrate how integrated micro-nano fiber optic sensors can serve as critical components in an early warning system for farmers.

Stem Micro-Strain and Growth Monitoring: FBG strain sensors can be directly attached to plant stems or trunks to monitor micro-strain induced by wind, fruit load, or pathological conditions like borer insects. This provides an early warning for physical stress and potential structural failure [42]. The technology offers a large strain range (±1800 µε) and excellent linearity (R² ≥ 0.9998), making it suitable for measuring both subtle growth and extreme weather events [42].

Micro-Climate and Leaf Temperature Sensing: FBGs are highly sensitive temperature sensors [43]. Miniaturized, waterproofed FBG sensors can be deployed within the crop canopy to monitor micro-climate conditions. Their immunity to electromagnetic interference (EMI) makes them ideal for use near farm machinery and electrical fencing [43] [38]. A proposed FBG temperature sensor design offers a high sensitivity of 0.61 nm/°C, allowing for precise tracking of ambient conditions that influence disease risk and plant development [43].

Sap pH and Xylem Biochemical Sensing: FBGs can be functionalized for biochemical sensing. A pH-sensitive gel coating swells or contracts in response to the acidity of the plant's sap or the surrounding soil solution [39]. This induces stress on the FBG, causing a Bragg wavelength shift correlated to pH levels, which can indicate nutrient deficiencies or disease [39]. For higher sensitivity, cladding-etched FBGs or MNFs can be used to measure the refractive index of xylem sap, which changes with ionic concentration and solute composition, serving as a biomarker for water stress or pathogen invasion [39].

Soil Moisture and Root Zone Environment Monitoring: FBG sensors packaged with hygroscopic polymers like Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) can measure relative humidity in the root zone [41]. The polymer absorbs or releases water vapor, causing it to expand or contract and strain the embedded FBG. This provides direct data on soil water status, enabling precise irrigation control and preventing drought stress or waterlogging [41].

Table 1: Performance Specifications of Fiber Optic Sensors for Agricultural Applications

| Sensor Type | Measurand | Sensitivity | Range | Key Advantage for Farming |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBG Strain Sensor [42] | Axial Strain | ~1.2 pm/µε (standard); Enhanced by packaging | ±1800 µε | Early detection of physical stress (wind, load, pests) on stems and branches. |

| FBG Temperature Sensor [43] | Temperature | 0.61 nm/°C | Not specified | EMI-immune micro-climate monitoring in electrically noisy farm environments. |

| Polymer-Functionalized FBG [41] | Relative Humidity | 0.5 dB/%RH | Not specified | Root zone soil moisture sensing for precision irrigation scheduling. |

| Microfiber Coupler Acoustic Sensor [41] | Acoustic Vibration | 1929 mV/Pa @ 120 Hz | 30 Hz - 20 kHz | Detection of insect chewing sounds or water flow in irrigation pipes. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of a UV-Resin Packaged FBG Strain Sensor for Plant Stem Monitoring

This protocol details the creation of a robust, high-performance FBG strain sensor suitable for mounting on plant stems or supporting structures [42].

1. Objectives:

- To inscribe a high-quality FBG into a single-mode optical fiber.

- To package the FBG in a planar UV-curable resin substrate to enhance strain transfer and provide environmental protection.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Optical Fiber: Photosensitized single-mode fiber (e.g., Corning SMF-28e) [42].

- UV Laser System: 248 nm excimer laser [42].

- Phase Mask: Matched to the desired Bragg wavelength (e.g., ~1550 nm) [42].

- Optical Spectrum Analyzer (OSA) and Amplified Spontaneous Emission (ASE) Broadband Light Source [42].