Field-Proven Strategies: Troubleshooting Plant Sensor Deployment for Robust Data Collection

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and agricultural scientists on overcoming the significant challenges of deploying plant sensors in field conditions.

Field-Proven Strategies: Troubleshooting Plant Sensor Deployment for Robust Data Collection

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and agricultural scientists on overcoming the significant challenges of deploying plant sensors in field conditions. It bridges the gap between laboratory research and practical application, covering foundational principles, methodological setup, advanced troubleshooting for common hardware and software issues, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing the latest research on sensor technologies, wireless networks, and data analytics, this guide aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to enhance data accuracy, ensure system reliability, and achieve successful long-term monitoring in unpredictable agricultural environments.

Understanding the Core Challenges in Field-Based Plant Sensor Deployment

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my plant disease classification model perform well in the lab but poorly in the field? Deep learning models trained on laboratory datasets (e.g., images with homogeneous backgrounds) often experience significant performance drops in field conditions due to extrinsic factors. One study quantified this drop, where model accuracy decreased from 92.67% in the lab to 54.41% in the field. This is primarily caused by complex, variable backgrounds, changing lighting conditions, and occlusion in real-world environments, which were not represented in the training data [1].

Q2: What are the most common installation errors that cause inaccurate soil moisture sensor data? Poor soil-to-sensor contact is the most critical error. Air gaps around the sensor probes can cause accuracy loss greater than 10% [2]. In wet soils, air gaps can make readings appear too high, as the sensor measures the high dielectric permittivity of water trapped in the gaps instead of the surrounding soil. In dry soils, air gaps can cause readings to appear too low or even dip below 0% VWC [3] [2].

Q3: How can I improve the reliability of my leaf wetness duration (LWD) data? Common installation problems include incorrect height, orientation, and angle. For reliable LWD data in the Northern Hemisphere [4]:

- Height: Install sensor 30 cm (1 ft) above ground.

- Orientation: Face the sensor north.

- Angle: Install at a 30–45° angle to the ground.

- Maintenance: Regularly replace degraded sensor paper or coating, and keep the sensor surface clean from dirt and pollen [4].

Q4: My soil moisture data shows unexpected spikes or dips. What does this mean? Unexpected data patterns often indicate installation or environmental issues [3] [2]:

- Spikes during wet conditions: Can be caused by preferential water flow through cracks or wormholes creating localized saturated zones, or by air gaps that fill with water [3].

- Dips below 0% VWC in dry conditions: This is physically impossible for soil and strongly indicates an air gap near the sensor needles or a sensor too close to the surface [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Fixing Poor Soil Moisture Sensor Data

Problem: Soil moisture readings are inaccurate or show unexpected patterns.

| Diagnosis Step | Symptom | Possible Cause & Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Check Soil Contact | Readings dip below 0% VWC or are erratic during dry-down; saturation levels seem too high [2]. | Cause: Air gaps between sensor and soil [3] [2]. Fix: Re-install the sensor. For single-depth sensors, use a rubber mallet for a clean insertion. For multi-depth sensors, create a pilot hole and use a soil slurry to ensure good contact [3]. |

| Verify Calibration | Data trends seem plausible, but absolute values are consistently too high or low [3]. | Cause: Wrong soil type calibration selected [3]. Fix: Perform soil sampling and lab analysis to determine the exact soil texture, then select the appropriate calibration curve from the sensor's library [3]. |

| Inspect for Preferential Flow | Irregular wetting patterns; one depth sensor saturates much faster than others [3]. | Cause: Water moving through cracks, root paths, or wormholes [3]. Fix: Reinstall the sensor in a new location. Using a slurry during installation can help fill natural macropores [3]. |

| Check Sensor Health | No signal, constant zeros, or physically impossible values [5]. | Cause: Sensor damage, cable cuts, or power failure [5]. Fix: Check cables for damage and connections for tightness. Use a handheld reader to verify sensor output before digging it up [2]. |

Guide 2: Addressing the Plant Disease Classification "Lab-to-Field" Gap

Problem: A model trained in controlled lab conditions performs poorly when deployed in the field.

Quantifying the Performance Gap: The table below summarizes the performance drop of deep learning models when applied to field versus lab conditions [1].

| Model Architecture | Laboratory Dataset Accuracy (%) | Field Dataset Accuracy (%) | Performance Drop (Percentage Points) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MobileNetV2 | 92.67 | 54.41 | 38.26 |

| ResNet50 | Data from lab setting | Data from field setting | Similar significant drop observed |

| VGG16 | Data from lab setting | Data from field setting | Similar significant drop observed |

Methodology for Improving Field Performance:

Data Collection & Pre-processing:

- Build Representative Datasets: Collect images directly in the field, capturing the full range of variability (e.g., different lighting, complex backgrounds, leaf orientations, and occlusions) [1].

- Background Removal: Experiment with pre-processing steps like removing complex backgrounds, though this may not fully solve the problem [1].

- Data Augmentation: Use techniques to artificially increase dataset variety and size.

Model Training & Evaluation:

- Architecture Selection: Test modern architectures (e.g., EfficientNet, Transformers) known for better generalization [6] [1].

- Employ Advanced Techniques: Utilize transfer learning, weakly supervised learning, and multimodal fusion to improve robustness with less labeled data [6].

- Feature Visualization: Analyze what features the model is using for classification to ensure it focuses on the actual leaf lesion and not the background [1].

Experimental Protocols for Field Deployment

Protocol 1: Correct Installation of Soil Moisture Sensors

Objective: To achieve high-accuracy soil moisture data by ensuring perfect soil-to-sensor contact and minimal site disturbance [2].

Materials: Soil moisture sensors, handheld reader/smartphone tool for verification, rubber mallet, small hand auger (for multi-depth sensors), soil slurry mixture, PVC conduit, zip ties, permanent marker, data logger.

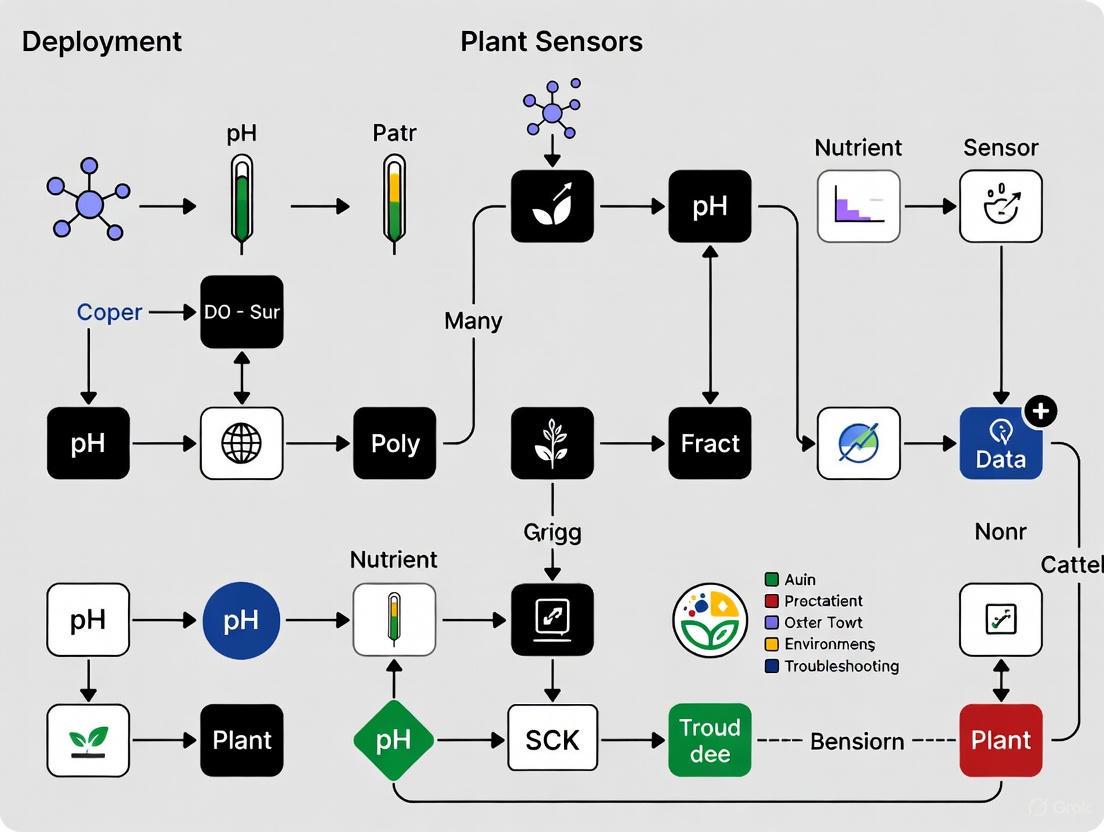

Workflow Diagram: Sensor Installation

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Pre-installation Preparation: Set up and test sensors in the lab on different soil types to understand expected readings. Program the data logger and prepare all tools [2].

- Site Characterization: Record extensive metadata (GPS, soil type, sensor depth, etc.). Identify a location representative of your study area, avoiding unusual features [2].

- Create Installation Hole:

- Sensor Installation:

- Pre-burial Verification: Before closing the hole, use a handheld reader to check the sensor output. Ensure the reading is accurate and plausible for the soil conditions [2].

- Cable Protection & Site Closure: Bundle sensor cables, sheath them in flexible conduit, and run them up the data logger post. Bury the conduit and secure cables with UV-resistant zip ties. Fill and close the installation hole [2].

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Model Performance Across Environments

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate and mitigate the performance loss of a plant disease classification model when deployed from lab to field.

Materials: Laboratory image dataset (e.g., PlantVillage), field-collected image dataset (e.g., RoCoLe, Plant Pathology), deep learning framework (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch), computing resources (GPU recommended).

Workflow Diagram: Model Benchmarking

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Baseline Model Training: Train a chosen convolutional neural network (e.g., MobileNetV2, ResNet50) on a curated laboratory dataset with a homogeneous background. Split the data into training and testing sets [1].

- Laboratory Performance Evaluation: Calculate standard metrics (e.g., accuracy, precision, recall) by running the trained model on the held-out laboratory test set. Record these values [1].

- Field Performance Evaluation: Using the same trained model, perform inference on a separate, representative field-collected dataset. Calculate the same metrics [1].

- Quantify the Performance Gap: Compare the metrics from Step 2 and Step 3. The difference (e.g., 92.67% lab accuracy vs. 54.41% field accuracy) quantifies the lab-to-field gap [1].

- Implement Improvement Strategies:

- Re-evaluate and Compare: Test the improved model on the field test set to measure the reduction in the performance gap.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Soil Slurry Mixture | A mixture of soil and water used to backfill around sensors during installation. It ensures excellent soil-to-sensor contact by eliminating air gaps, which is critical for data accuracy [3]. |

| Handheld Sensor Reader | A portable device (e.g., ZSC tool) that connects to a smartphone to instantly check sensor readings during installation. This allows for verification of sensor function and accuracy before the site is closed, preventing costly errors [2]. |

| PVC Pipe Mounting | An inexpensive, customizable structure built from PVC tubes and elbows. It provides a stable and standardized platform for installing sensors like leaf wetness sensors at the correct height and angle [4]. |

| Flexible Conduit | A protective sheath for sensor cables. Burying cables inside this conduit shields them from damage by rodents, UV radiation, and farming equipment, ensuring long-term data integrity [4] [2]. |

| Graphene/Ecoflex Strain Sensor | An emerging plant-wearable sensor. Its mesh structure and biocompatible encapsulation offer high sensitivity and reliability for monitoring plant growth and stress in dynamic field environments [7]. |

This technical support center is designed within the context of a broader thesis on troubleshooting plant sensor deployment in field conditions. For researchers and scientists, collecting high-fidelity data in real-world environments is paramount. This guide addresses the most common environmental stressors—weather, soil variability, and physical damage—that compromise sensor integrity and data accuracy. The following FAQs, troubleshooting guides, and experimental protocols provide a structured approach to diagnosing, resolving, and preventing field deployment issues.

◉ Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common signs of a failing environmental sensor in the field? Symptoms vary by sensor type but generally include complete signal loss, erratic or physiologically impossible readings (e.g., a soil moisture sensor reading -10% VWC), equipment operating outside programmed parameters (e.g., irrigation activating during rain), and data that fails to correlate with observed field conditions [8]. For soil moisture sensors, a specific test involves measuring the sensor in air (should read between -5% and -50%) and then gripping the sensing area with your hand (should read between 10% and 50%); deviations from this range indicate a potential problem [9].

2. Why do I get large sensor-to-sensor variability even with identical models and placements? High sensor-to-sensor variability, especially with capacitance-type soil moisture sensors under drip irrigation, is a documented challenge [10]. This can be caused by natural soil heterogeneity (e.g., variations in gravel content, bulk density, and macropores), small-scale variations in the wetting pattern from drippers, and differences in soil contact at installation [10]. Using a robust calibration for your specific soil type and ensuring perfect soil contact during installation can mitigate this [3].

3. How does soil salinity affect soil moisture sensor readings? Soil with high salt concentrations can interfere with the accuracy of certain soil moisture sensors, particularly resistance or conductivity sensors [11]. The ions in the soil solution alter the electrical properties that the sensor measures, leading to inaccurate volumetric water content (VWC) readings. It is recommended to use sensors with calibrations that account for salinity or to use sensor types less susceptible to saline interference, such as high-quality capacitance sensors [9] [11].

4. What are the critical steps for preventing physical sensor damage during deployment? To prevent physical damage:

- Use Protective Housings: Install sensors in protective housings or flow-through assemblies to guard against impact and abrasive wear [8].

- Correct Installation: For soil probes, use a pilot hole and a rubber mallet to avoid damaging the probe during insertion. Ensure the hole diameter matches the sensor to prevent excessive force [3].

- Environmental Hardening: Select sensors designed to withstand specific environmental stressors like high temperatures, vibration, and moisture ingress [8]. Implement waterproofing measures for connectors and cables [12].

◉ Troubleshooting Guides

Common Sensor Failures and Solutions

| Stressor Category | Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weather & Environment | Drifting pH readings, slow response. | Reference junction dehydration from dry storage or low humidity [13]. | Attempt to calibrate; sensor will not hold calibration. | Store pH sensors in manufacturer-recommended solution. For deployed sensors, ensure protective caps are used [13]. |

| Erratic moisture/temperature data. | Operation outside specified temperature ranges (e.g., standard range is -5°C to 80°C) [13]. | Compare sensor data with a verified reference thermometer. | Select sensors with wider operational temperature ranges suitable for the deployment climate [8]. | |

| Unusually low irradiance or pyranometer readings. | Dust, dirt, or bird droppings on the sensor surface [14]. | Perform a physical visual inspection. | Clean the sensor surface regularly according to manufacturer guidelines using appropriate solvents [14]. | |

| Soil Variability | Poor soil moisture data accuracy. | Incorrect soil calibration selected (e.g., using a clay calibration for a sandy soil) [3]. | Perform a soil texture analysis via lab sample. | Re-calibrate the sensor using site-specific soil coefficients from a soil lab analysis [3]. |

| Inconsistent readings between adjacent sensors. | Poor soil-to-sensor contact, creating air gaps [3]. | Check for loose installation. Observe if dry readings are too low and wet readings are too high [3]. | Re-install the sensor, using a soil slurry to fill the pilot hole and ensure full contact with the soil matrix [3]. | |

| Sudden, localized changes in moisture data. | "Preferential flow" where water travels through cracks or root paths, not representing bulk soil [3]. | Inspect installation site for visible cracks or channels. | Re-install the sensor in a new location that is representative of the general soil profile [3]. | |

| Physical Damage | Sensor is unresponsive, no power. | Physical damage to wiring, connectors, or internal circuits from impact or crushing [12]. | Check power supply and inspect cables for breaks or fraying. | Replace damaged cables or the sensor unit itself. Use conduit and protective tubing for cables [8] [12]. |

| Scratched or cracked glass component (e.g., pH bulb). | Mechanical impact, abrasion from cleaning, or rapid thermal shock [13]. | Perform a visual inspection of the sensitive element. | Replace the sensor. Use protective housings and avoid abrasive cleaning tools [13]. | |

| Clogged reference junction (pH sensors). | Fouling from suspended solids, biological growth, or chemical precipitates [13]. | Sensor shows signal drift and slow response times. | Implement a regular cleaning schedule using methods tailored to the foulant (e.g., acid wash, enzymatic clean) [13]. |

Quantitative Sensor Performance Data

Table 2: Comparison of 2025 Soil Moisture Sensor Technologies for Research [11]

| Sensor Type | Principle of Operation | Estimated Accuracy | Typical Cost (Est.) | Power Consumption | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacitance | Measures dielectric permittivity | ±2% VWC | $50 - $100 | Low | Irrigation scheduling, water use efficiency |

| TDR | Time for electric pulse to return | ±1% VWC | $200 - $500 | Medium | Research, precision irrigation, soil health |

| Resistance (Gypsum Block) | Electrical resistance between electrodes | ±4% VWC | $15 - $30 | Low | Basic irrigation management, educational |

| Neutron Probe | Slow neutron moderation by water | ±1% VWC | $3000 - $5000 | High | Calibration, research (lab-based) |

Table 3: Comparison of 2025 Temperature Sensor Technologies [11]

| Sensor Type | Principle of Operation | Estimated Accuracy | Typical Cost (Est.) | Data Transmission | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Thermistor | Resistance changes with temperature | ±0.5°C | $20 - $60 | LoRaWAN, Bluetooth | Soil temp monitoring, planting, yield prediction |

| Infrared Temperature Sensor | Infrared radiation measurement | ±1–2°C | $80 - $120 | Wi-Fi, GSM | Canopy stress, disease forecasting |

◉ Experimental Protocols for Field Validation

Protocol 1: Validating Soil Moisture Sensor Accuracy and Placement

This methodology is designed to quantify sensor-to-sensor variability and validate placement strategies in a drip-irrigation system, as explored in scientific literature [10].

1. Hypothesis: Sensor-to-sensor variability in field conditions is significantly greater than variability observed in controlled laboratory settings, primarily due to soil heterogeneity and dynamic wetting patterns.

2. Materials:

- Multiple identical capacitance/FDR soil moisture sensors (e.g., EC-5, 10HS) [10].

- Data loggers (e.g., CR800, CR1000) with multiplexers [10].

- Equipment for soil analysis: soil auger, core sampler, bags for soil samples.

- Lab access for soil texture (sand, silt, clay %), bulk density, and organic matter analysis [10].

3. Experimental Setup:

- Site Selection: Choose a representative plot (e.g., a drip-irrigated orchard).

- Sensor Deployment: Install sensors at multiple depths (e.g., 15 cm, 30 cm, 60 cm) and positions relative to the dripper (e.g., at the dripper, midpoint between drippers). Employ at least 3 repetitions per position/depth combination around different drippers [10].

- Soil Characterization: Collect soil samples at the same depths for lab analysis of texture, bulk density, and organic matter to establish baseline soil properties [10].

4. Data Collection & Analysis:

- Log soil moisture data at high frequency (e.g., every 10 s, stored as 5-min averages) over multiple irrigation seasons [10].

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate the mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation for sensors installed at equivalent depths and positions.

- Model Comparison: Use software like HYDRUS-3D to simulate the expected soil water dynamics and wet bulb formation. Compare the measured sensor-to-sensor differences with the simulated differences from the model to decouple measurement uncertainty from natural soil variability [10].

Protocol 2: Stress-Testing Sensor Resilience to Physical Damage

1. Hypothesis: Standard sensor housings and mounting solutions are insufficient to maintain data integrity under repeated mechanical stress and harsh environmental conditions.

2. Materials:

- Sensors of interest (e.g., photoelectric, capacitive, ultrasonic).

- Environmental chamber (for controlled temperature/humidity cycling).

- Vibration table.

- Equipment for abrasion and impact testing.

- Data acquisition system to monitor sensor output in real-time.

3. Experimental Workflow: The following diagram outlines the stress-testing protocol to systematically evaluate sensor durability.

4. Data Analysis:

- Record failure modes (e.g., signal dropout, drift, physical cracking).

- Compare pre- and post-stress calibration data to quantify accuracy loss.

- Determine the Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF) for each sensor model under specific stress conditions.

◉ The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key Materials for Sensor Deployment and Calibration

| Item | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Soil Sampling Kit | For collecting undisturbed soil cores to determine texture, bulk density, and organic matter content. | Critical for selecting the correct soil calibration coefficients for moisture sensors [3] [10]. |

| Reference Tensiometer | Provides a direct measurement of soil water potential, serving as a ground-truth reference for validating soil moisture sensor data. | Used for in-situ calibration and verification, especially in soils with unusual composition [10]. |

| HYDRUS Software | A mathematical model for simulating water, heat, and solute movement in variably saturated porous media. | Used to simulate "virtual sensor" readings and decouple sensor error from natural soil moisture variability [10]. |

| Calibration Solutions (pH/Buffer) | Solutions of known pH value (e.g., 4.01, 7.00, 10.01) used to calibrate and verify the accuracy of pH sensors. | Prevents sensor drift. Essential for maintaining data accuracy in chemical and biological applications [13]. |

| Protective Sensor Housings | Shields sensors from direct impact, UV radiation, and abrasive particles in the environment. | Significantly extends sensor lifespan in harsh field conditions [8]. |

| Rubber Mallet & Pilot Hole Auger | Tools for the correct installation of probe-type soil sensors. | Ensures good soil-to-sensor contact and prevents damage to the probe during insertion [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our hyperspectral data shows inconsistent results between laboratory and field deployments. What are the key calibration steps we might be missing?

A1: Inconsistent data often stems from incomplete calibration. A full calibration workflow is essential for reliable physical reflectance data. Key steps include:

- Sensor Wavelength Calibration: Map each camera pixel to its precise wavelength.

- Radiometric Calibration: Correct for sensor offset, noise, and non-uniform sensitivity. This involves taking dark (with lens covered) and white (using a calibration panel) references under the same illumination as your experiment.

- Geometric Correction: Account for lens distortion and, for 3D plant canopies, correct for the influence of leaf inclination angles. Perform camera calibration to rectify lens-induced distortions [15] [16].

- Illumination Consistency: Always use stable, consistent lighting conditions during data capture. Perform calibration under the same illumination as your plant measurements [15].

Q2: When should we choose a hyperspectral imaging system over a standard RGB camera for plant disease detection?

A2: The choice depends on your detection goals, budget, and processing capabilities. The following table compares the core features of RGB and Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI):

| Feature | RGB Imaging | Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Bands | 3 broad bands (Red, Green, Blue) [17] | Hundreds of narrow, continuous bands [15] [18] |

| Primary Strength | Detecting visible symptoms; high accessibility and lower cost [19] | Detecting pre-symptomatic, physiological changes; high precision and early warning [19] [18] |

| Typical Accuracy | 95-99% (lab), 70-85% (field) [19] | Can achieve over 90% accuracy in controlled studies [19] [18] |

| Cost | $500-$2,000 USD [19] | $20,000-$50,000 USD [19] |

| Best For | Identifying diseases with clear visual symptoms, large-scale screening where cost is a constraint. | Early disease detection, differentiating between similar diseases, research on plant physiology [18]. |

Q3: What are the common failure points for wearable plant sensors, and how can we ensure reliable data in field conditions?

A3: Wearable sensors fail primarily due to environmental interference, physical damage, and power issues.

- Biocompatibility and Attachment: Ensure the sensor's flexible substrate (e.g., PDMS, Ecoflex) and adhesive do not damage the plant organ or inhibit its natural growth and transpiration. A poor attachment can lead to motion artifacts or tissue damage [20] [21].

- Environmental Resilience: Sensors must be encapsulated to protect against rain, humidity, and UV degradation. Check the encapsulation material's durability under varying weather conditions [20].

- Power Management: For long-term monitoring, integrate an Energy Harvesting (EH) solution such as a small photovoltaic cell to power the sensor and its wireless data transmission, which is often the largest energy drain [22].

- Signal Drift: Regularly calibrate chemical sensors (e.g., for VOCs) to account for signal drift over time [23].

Q4: How can we effectively fuse data from different sensor modalities, like RGB, hyperspectral, and chlorophyll fluorescence?

A4: Multi-modal data fusion requires precise image registration. The following workflow outlines a robust, automated pipeline for aligning images from different sensors [16]:

- Step 1: Camera Calibration. Individually calibrate each camera (RGB, HSI, Fluorescence) to correct for lens distortion. This is a prerequisite for accurate alignment.

- Step 2: Coarse Global Registration. Use an affine transformation (accounting for translation, rotation, scaling, and shearing) to align the images globally. Algorithms like Phase-Only Correlation (POC) or Enhanced Correlation Coefficient (ECC) are robust to intensity differences between modalities [16].

- Step 3: Fine Object-Level Registration. Since a single global transformation may not be perfect across all objects, perform an additional fine registration on individual plant organs or regions of interest to achieve pixel-level accuracy. This can achieve an overlap ratio exceeding 96% [16].

The diagram below illustrates this multi-modal image registration workflow.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Accuracy in Field-Based Hyperspectral Disease Detection

Problem: A model trained on hyperspectral data in the laboratory shows a significant drop in accuracy when deployed in the field.

Solution:

- Review Data Preprocessing: Ensure you are applying all necessary preprocessing steps to field data identical to your lab data.

- Spectral Calibration: Verify wavelength alignment.

- Normalization: Apply the same normalization technique used during model training to account for varying illumination in the field [18].

- Check for Environmental Interference: Factors like wind (causing motion blur), changing sunlight angles, and shadowing can corrupt data. Collect data during stable, clear weather conditions around midday [18].

- Re-train with Field Data: Laboratory models often fail to generalize. Augment your training dataset with spectral data collected from the field under various conditions to make the model more robust [19].

- Simplify the Model: If using a complex model like a deep neural network, try a simpler algorithm (e.g., Random Forest) which can be more robust with smaller, noisier datasets. Use feature selection (e.g., RELIEF-F algorithm) to identify the most robust spectral bands for your application [18].

Issue: Wearable Sensor Causing Plant Tissue Damage or Influencing Physiology

Problem: The plant organ where the sensor is attached shows signs of necrosis, abnormal growth, or reduced transpiration.

Solution:

- Re-evaluate Sensor Materials: The sensor must be highly flexible, lightweight, and biocompatible.

- Verify Attachment Method: Avoid adhesives or clamps that are too tight and constrict growth or damage the epidermis. The attachment should be secure but minimal.

- Monitor for Long-Term Effects: Conduct control experiments to quantify the sensor's impact on plant physiology over the entire growth cycle. Calibrate sensor readings against non-invasive measurements to account for any influence [23].

Issue: Power Drainage in Wireless Wearable Sensor Nodes

Problem: The battery in a wearable sensor node depletes too quickly for long-term monitoring.

Solution:

- Analyze Power Budget: Identify the main power consumers. Typically, wireless data transmission is the most energy-intensive task [22].

- Implement Energy Harvesting: Integrate a micro-energy harvester to power the node.

- Solar: Use a small photovoltaic cell for outdoor deployments.

- Thermal: A thermoelectric generator can exploit temperature differences between the plant and air.

- Kinetic: Piezoelectric materials can harvest energy from wind-induced plant movement [22].

- Optimize Data Transmission Protocol:

- Reduce the frequency of data transmission.

- Implement a wake-on-demand or low-power sleep schedule for the microcontroller and transmitter.

- Use energy-efficient communication protocols like LoRaWAN or Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for developing and deploying plant wearable sensors, based on current research.

| Item | Function in Experiment | Key Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Flexible Substrates | Provides a base for the sensor that can conform to plant surfaces without causing damage. | Buna-N rubber, Latex, Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), Ecoflex, Polyimide (PI), Hydrogels [20] [21]. |

| Conductive/Sensing Materials | Forms the active sensing element, changing electrical properties in response to stimuli. | Graphite ink, Carbon Nanotubes (CNT), Graphene, Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO), Gold metal films, conductive polymers like Polyaniline (PANI) [20] [21]. |

| Encapsulation Materials | Protects the sensing element from environmental damage (water, UV) and shields the plant from potentially toxic materials. | PDMS, Ecoflex, SU-8 photoresist [20]. |

| Calibration Equipment | Critical for validating and standardizing sensor readings, especially for spectral and chemical sensors. | Spectrophotometer for wavelength calibration, calibrated white reference panels for radiometric calibration, gasses for VOC sensor calibration [15] [23]. |

| Energy Harvesting Components | Enables long-term, battery-free operation of active wearable sensors in the field. | Photovoltaic (PV) cells, piezoelectric materials (e.g., PVDF, AlN), thermoelectric generators [22]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary types of soil moisture sensors used in agricultural research? Researchers primarily work with two types of sensors, selected based on whether the study focuses on the physical amount of water or its biological availability to plants [24]:

- Volumetric Water Content (VWC) Sensors: Measure the volume of water in the substrate. They are common in commercial greenhouse studies and provide direct readings of water content for a variety of growing media [24].

- Soil Water Potential (SWP) Sensors: Measure the tension (matric potential) with which water is held in the substrate. This is a critical factor for determining plant-available water, as it reflects the force plants must exert to extract water [24].

Q2: Why is sensor calibration, particularly for soil type, so critical for data accuracy? Calibration is fundamental because soil moisture sensors measure capacitive resistance, which is then converted into a volumetric water content percentage [3]. This conversion is highly dependent on the specific soil texture.

- The Calibration Process: Using an incorrect soil calibration will misalign the thresholds for field capacity (upper water limit) and plant stress (lower water limit), making irrigation scheduling data unreliable [3]. Soil maps are a starting point, but for high-precision research, soil sampling and lab analysis are recommended to obtain a site-specific calibration [3].

Q3: What are the emerging technological trends for the 2025 growing season? The field is rapidly evolving with several key trends [24]:

- Wireless Sensors: Offer greater flexibility and reduce installation labor.

- Data Integration: Soil moisture data is being combined with other environmental data (e.g., temperature, humidity, light) for a holistic view of growing conditions.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI): AI is used to analyze data and provide precise irrigation recommendations, learning from historical data to adapt to changing conditions.

- Remote Sensing: Drones and satellites are being used to map soil moisture variability across large areas.

Q4: How many sensors are typically needed for a representative experimental setup? The number of sensors is not one-size-fits-all and depends on the experimental design [24]:

- Key Factors: The size of the study area, the number of distinct crop types or treatments, the variability of soil conditions, and the irrigation system's zoning.

- General Recommendations: For small-to-medium plots, start with 2-4 sensors in key areas. For large-scale field trials, 10 or more sensors may be necessary for comprehensive coverage and statistical significance [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide to Erratic or Inaccurate Sensor Readings

Problem: Sensor data shows unexpected highs, lows, or high-variance fluctuations that do not correlate with irrigation events or weather conditions.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Probable Cause 1: Poor Soil Contact

- Symptoms: Readings are consistently too low in dry conditions (sensor measuring air pockets) or too high in saturated conditions (air gaps filled with water) [3].

- Solution: Re-install the sensor. For single-depth sensors, remove and reinstall in a new location a few feet away, using a rubber mallet to ensure full insertion [3]. For multi-depth sensors, create a pilot hole with a 1” auger, hammer the sensor in with a mallet, and use a soil slurry mixture to fill any remaining gaps [3].

Probable Cause 2: Incorrect Sensor Placement in Substrate

- Symptoms: VWC readings are persistently too low or too high.

- Solution: Follow substrate-specific placement protocols [25]:

- Rockwool cubes/slabs: Place 1 inch from the bottom.

- CoCo substrates: Place 2 inches from the bottom for 1-gallon pots; 3 inches for 2-gallon pots and larger.

- A sensor placed too high will read low; a sensor placed too low will read high due to pooled water [25].

Probable Cause 3: Preferential Flow Channels

- Symptoms: Irregular readings, particularly after irrigation, as water travels down cracks, wormholes, or root paths instead of wetting the soil uniformly [3].

- Solution: Reinstall the sensor in a new location. Flooding the pilot hole with a slurry during installation can help ensure even soil contact and prevent this issue [3].

Probable Cause 4: Incorrect Soil Calibration

- Symptoms: Data values are within a plausible range but do not accurately reflect true field conditions, making it difficult to establish correct field capacity and plant stress points.

- Solution: Verify the soil texture through sampling and lab analysis. Select the correct, research-grade calibration from the sensor manufacturer's library or use a custom calibration [3].

Guide to Sensor Communication and Power Failures

Problem: Sensor is not reporting any data or is reporting erratically.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

Probable Cause 1: Incorrect Electrical Terminations

Probable Cause 2: Controller Requires Reset

- Symptoms: Newly connected sensor is not recognized.

- Solution: Tap the reset button on the controller. Some controllers only scan for new hardware during a reboot [25].

Probable Cause 3: Daisy-Chaining Configuration Error

- Symptoms: Multiple sensors are connected, but one or more are not reporting data.

- Solution: Ensure the controller supports daisy-chaining (e.g., operating as a module). Each sensor on the same bus must be set to a unique SDI-12 address to be detected properly [25].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Optimal Sensor Installation

This protocol ensures the collection of accurate and representative soil moisture data.

1. Site Selection:

- Choose a location that represents the average soil conditions and crop growth in the study area [24].

- Avoid areas with unusual drainage, poor vigor, or near obstacles like support beams and walkways that could interfere with readings [24].

2. Sensor Preparation:

- Follow the manufacturer’s recommendations for initial wetting and drying of the sensor to ensure optimal performance [24].

3. Installation:

- Depth: Place the sensor within the active root zone of the plants being studied. For larger plants, consider multiple sensors at different depths to profile water uptake [24].

- Contact: Ensure excellent soil contact with the sensor probes. Avoid air pockets by using a slurry or pilot hole technique as described in the troubleshooting guide [24] [3].

- Drip Irrigation: If using drip irrigation, place the sensor near the dripper to measure the moisture level in the wetted root zone [24].

4. Post-Installation:

- Set initial irrigation thresholds based on crop requirements and adjust as the experiment progresses [24].

Protocol for Sensor Calibration and Validation

This protocol outlines steps for verifying and maintaining sensor accuracy.

1. Soil Sampling:

- Collect soil samples from the immediate vicinity of the sensor installation.

- Send samples to a certified soil lab (e.g., Eurofins) for texture analysis [3].

2. Calibration Selection:

- Use the lab's texture results to select the most appropriate calibration from the manufacturer’s library (e.g., Sensoterra's library of over 50 soil types) [3].

- For the highest precision, work with the manufacturer's lab to develop a custom calibration for your specific soil [3].

3. Gravimetric Validation:

- Periodically, take a soil sample adjacent to the sensor at the same depth.

- Determine the gravimetric water content (GWC) by weighing the sample, oven-drying it at 105°C for 24-48 hours, and re-weighing it.

- Convert GWC to VWC using the soil's bulk density and compare this value to the sensor's reading to validate accuracy.

Data Presentation Tables

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Soil Moisture Sensor Types for Research

| Feature | Volumetric Water Content (VWC) Sensors | Soil Water Potential (SWP) Sensors |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Parameter | Volume of water per volume of soil [24] | Tension (matric potential) of soil water [24] |

| Primary Research Application | Quantifying total water volume in the root zone [24] | Studying plant-available water and water stress [24] |

| Key Consideration | Provides a direct measure of water quantity [24] | Reflects the energy state of water; critical for plant physiology studies [24] |

| Influencing Factors | Soil texture and calibration affect accuracy [3] | Helps define when plants can easily access water [24] |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Matrix for Common Sensor Issues

| Observed Problem | Most Likely Causes | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Erratic / Noisy Data | Air pockets, root-bound substrate, preferential flow [3] [25] | Reinstall sensor with slurry to ensure soil contact [3] |

| Persistently Low VWC | Sensor placed too high in substrate, poor soil contact [3] [25] | Reinstall at proper depth for the substrate type [25] |

| Persistently High VWC | Sensor placed too low in substrate (in pooled water) [25] | Reinstall at a higher position in the root zone [25] |

| No Data Reporting | Incorrect wiring, controller needs reset, address conflict [25] | Check terminations, reboot controller, verify unique addresses [25] |

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Plant Sensor Deployment

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Capacitance-Based Soil Sensor | The primary data collection tool; measures the dielectric permittivity of the substrate to estimate VWC and salinity [25]. |

| Soil Auger (1” diameter) | For creating pilot holes for multi-depth sensor installation, minimizing soil disturbance and ensuring proper depth placement [3]. |

| Rubber Mallet | For installing sensors to the correct depth without damaging the sensitive electronics or probe structure [3]. |

| Data Logger / Controller | Records sensor measurements over time. Modern systems allow for wireless data transmission and integration with other environmental data [24]. |

| Oven and Precision Scale | Essential for the gravimetric soil moisture method, which is used to validate and calibrate the electronic sensor readings. |

| Soil Sampling Kit | For collecting soil cores to be sent to a lab for texture analysis, which is critical for selecting the correct sensor calibration [3]. |

Visualized Workflows and Diagrams

Methodologies for Robust Sensor System Design and Network Architecture

FAQs: Sensor Selection and Deployment

Q1: What are the primary technical trade-offs between low-cost and commercial-grade sensors?

The choice involves balancing immediate cost against long-term reliability, data accuracy, and total cost of ownership. Low-cost sensors offer compelling upfront savings but often have narrower operating ranges, higher calibration drift, and shorter lifespans, which can compromise long-term research integrity [26] [27]. Commercial-grade systems are characterized by robust construction, higher accuracy specifications, factory calibration, and insensitivity to environmental variables like temperature, which is a known source of error for many soil moisture sensors [28] [3] [24].

Q2: In field conditions, what are the most common causes of inaccurate sensor readings?

The most frequent issues are related to installation and environmental factors, not necessarily the sensor itself. Key problems include:

- Poor Soil Contact: Air pockets between the sensor probe and the soil, often caused by improper installation or soil shifting, lead to significant measurement errors by measuring air instead of soil [28] [3].

- Preferential Flow: Water moving rapidly through cracks, root paths, or wormholes creates irregular wetting patterns, causing misleading localized readings [28] [3].

- Soil Disturbance: Any change to the soil's natural structure during installation alters its density, water storage capacity, and electrical conductivity, impacting readings until the soil stabilizes [28].

- Temperature Effects: The dielectric permittivity measured by many sensors is affected by temperature, causing readings to fluctuate between night and day independent of actual moisture changes [28].

Q3: How does sensor calibration impact data quality for research?

Calibration is critical for transforming raw sensor readings into accurate, actionable data. Many low-cost sensors provide a generic calibration, while commercial-grade systems often come with factory calibrations for specific soil types or allow for custom local calibration [3] [24]. Calibration drift over time is a recognized challenge, particularly for chemical sensors, and can restrict their use in long-lifecycle applications where measurement accuracy is paramount [26]. For research, selecting a sensor with a known calibration margin of error and a stable calibration profile is essential.

Q4: What are the hidden costs associated with low-cost IoT sensor systems?

The initial purchase price is only one component of the total cost. Hidden costs can include [24] [27]:

- Labor for Maintenance and Battery Replacement: A large network of sensors may require significant manual effort to maintain.

- Data Gaps and Failed Experiments: Sensor failure or inaccurate data can invalidate research results, costing time and resources.

- Data Management Overhead: Systems with limited memory or disparate data storage can create manual work for data extraction and homogenization [27].

- Replacement Costs: Shorter sensor lifespans lead to more frequent repurchasing.

Q5: When is it absolutely necessary to invest in a commercial-grade sensor system?

Commercial-grade systems are warranted when the research involves:

- Regulated Environments where data integrity must be proven, such as in pharmaceutical development or GxP-compliant studies [26] [29].

- Long-Term Studies where calibration drift and sensor longevity are primary concerns [26] [27].

- Scientific Publication where the highest possible data accuracy and reliability are required to withstand peer review [28] [24].

- Harsh Environmental Conditions where industrial-grade robustness is needed to ensure continuous operation.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Erratic Soil Moisture Readings

Problem: Sensor data shows unexpected dryness or saturation that doesn't match field observations.

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

Verify Physical Installation:

- Action: Carefully excavate around the sensor to inspect for air gaps or voids.

- Fix: Reinstall the sensor in a new location. For single-depth probes, use a rubber mallet to ensure full insertion. For multi-depth sensors, create a pilot hole and use a soil slurry to guarantee contact at all depths [3].

Check for Preferential Flow Paths:

- Action: Look for visible cracks, insect nests, or root channels near the installation site.

- Fix: Relocate the sensor to an area with uniform soil structure. Mound soil above the sensor point to prevent water from channeling directly down to the probe [28].

Confirm Calibration Settings:

Correlate with Temperature Data:

- Action: Plot soil moisture data against temperature data from the same period.

- Fix: If a strong correlation is found without irrigation or rain, the readings are likely biased by temperature. Consider switching to a higher-quality sensor designed to minimize temperature effects [28].

Guide 2: Addressing Data Logger and Connectivity Failures

Problem: Missing data points, failed alarms, or loss of communication with the central data platform.

Investigation and Resolution Protocol:

Diagnose Power and Connectivity:

- Action: Check the device's power indicator and battery status. For wireless units, verify network signal strength (e.g., LoRaWAN, cellular) [30] [27].

- Fix: Replace batteries or secure power connections. For network issues, consider devices with dual-SIM capabilities or 4G failover to maintain connectivity [27].

Investigate Data Gaps and Missed Alarms:

- Action: Review data logs for precise timing of dropouts.

- Fix: This is a common flaw in simple data loggers. Upgrade to a real-time data acquisition system that buffers data during outages and delivers all missed alarms upon reconnection instead of being overwhelmed [27].

Validate Sensor-Data Logger Communication:

- Action: Ensure sensors are properly connected to the data logger and that the configuration (e.g., measurement interval) is correct.

- Fix: A professional installation of an integrated data acquisition system can prevent errors from misconnected or miscalibrated sensors [27].

Quantitative Data Comparison

Table 1: Cost-Benefit Analysis of Sensor Grades

| Factor | Low-Cost IoT Sensor | Commercial-Grade System |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Unit Cost | Low (<$100 in many cases) | High (Can be 5-10x more) |

| Typical Accuracy | Moderate, with broader error margins [28] | High (e.g., >99.5% calibrated accuracy) [3] |

| Calibration | Often generic; prone to drift [26] | Factory-calibrated for specific materials/conditions [3] [24] |

| Durability & Lifespan | Shorter; may not be industrial-grade [27] | Long; designed for continuous field operation |

| Power Management | Often battery-dependent, requiring frequent changes [27] | Options for energy harvesting, PoE, and redundant power [26] |

| Data Integrity | Risk of gaps, missed alarms, and disparate data [27] | High; real-time streaming with backup buffers [27] |

| Total Cost of Ownership | Higher over time due to maintenance and replacement [27] | Lower over a long-term study despite higher initial investment |

Table 2: IoT Sensor Market Trends & Technical Specs (2025-2030)

| Parameter | Current Market Data & Forecast | Relevance to Sensor Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Global IoT Sensor Market Size | USD 21.58 Bn (2025) → USD 188.59 Bn (2032) at 36.3% CAGR [30] | Indicates rapid innovation and falling costs for core technologies. |

| Wireless Sensor Share | 78.8% of market revenue in 2025 [30] | LPWAN (LoRaWAN, NB-IoT) is dominant, enabling scalable, low-power deployments [26]. |

| Leading Sensor Type | Accelerometers/Inertial/Gyroscope (26.3% share in 2025) [30] | Critical for predictive maintenance in industrial research settings [31]. |

| Key Growth Driver | Predictive Maintenance (25% cost savings, 70% downtime avoidance reported) [32] | Justifies investment in higher-grade sensors for monitoring critical equipment. |

| Major Market Restraint | Calibration drift in long-lifecycle chemical sensors [26] | A key factor to vet when selecting sensors for long-term studies. |

Sensor Selection Logic and Workflow

The following diagram outlines a systematic decision-making process for selecting between low-cost and commercial-grade sensors, based on research objectives, environmental constraints, and budgetary considerations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for Sensor Deployment and Validation

| Item | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Soil Sampling Kit | To collect undisturbed soil cores for laboratory texture analysis. | Essential for verifying field conditions and selecting the correct soil calibration for moisture sensors [3]. |

| Soil Slurry Mixture | A mud-like paste of soil and water. | Used during installation of multi-depth sensors to eliminate air gaps and ensure perfect soil-to-sensor contact at all measurement levels [3]. |

| Calibration Standards | Solutions or materials with known properties (e.g., conductivity, moisture content). | Used for periodic validation and recalibration of sensors to combat drift and ensure long-term data accuracy [26] [24]. |

| Data Acquisition System | Hardware and software for recording, storing, and analyzing sensor data in real-time. | Superior to basic data loggers, as it provides continuous monitoring, immediate alarms, and avoids data gaps [27]. |

| Rubber Mallet | A soft-faced hammer. | Used for the proper installation of probe-style sensors to ensure they are fully inserted into the soil without damaging the device [3]. |

Optimizing Wireless Sensor Network (WSN) Architecture for Energy Efficiency and Reliable Data Transmission

FAQs: Deployment and Connectivity

Q1: What is the optimal height for deploying sensor nodes in an orange orchard to maximize coverage?

A: Research indicates that near-ground deployment generally provides the best coverage in agricultural settings like orange orchards. One study tested on-ground, near-ground, and above-ground placements, finding that node height significantly affects signal quality due to interactions with vegetation [33].

Q2: How does plant foliage density impact my wireless signal, and how can I mitigate this?

A: Densely vegetated areas cause high signal variability and attenuation. The attenuation level depends on the specific type of vegetation, its density, and the communication frequency [33]. To mitigate this:

- Node Placement: Strategically place nodes to avoid the densest parts of the canopy where possible.

- Node Density: Consider a higher density of nodes to ensure reliable data transmission.

- Deployment Strategy: A near-ground deployment can sometimes offer a more reliable path than one through thick foliage [33].

Q3: What are the key differences between deploying a WSN in a grassland versus an orchard?

A: The propagation characteristics differ significantly. Studies have shown that grasslands generally offer better propagation models for radio signals, followed by forests and then scrublands [33]. Orchards, with their structured but dense vegetation, present unique challenges. The semi-regular pattern of trees creates a complex environment with potential for both signal blockage and guided wave paths, making empirical testing in your specific field crucial [33].

Q4: My sensor nodes are experiencing a high rate of data packet loss. What are the primary factors I should investigate?

A: A high packet delivery rate (e.g., above 95% as achieved in some field tests) is achievable with proper design [34]. Investigate these factors:

- Link Quality: Check the Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI). A poor RSSI (e.g., approaching -90 dBm) indicates a weak link [33].

- Environmental Interference: Canopy and soil can significantly impact system reliability [34].

- Energy Levels: Low power can cause transmission faults. Ensure stable power supplies and check battery levels.

- Hardware Faults: Inspect for physical damage to nodes or antennas from animals, machinery, or environmental exposure [34].

FAQs: Energy Management and Network Lifetime

Q5: What is the most effective strategy for conserving energy in a long-term soil monitoring WSN?

A: A multi-faceted approach is required. Key strategies include:

- Clustering and Deep Learning: Employ a Deep Learning-based Grouping Model Approach (DL-GMA) that uses Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) with Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) for optimal cluster formation and Cluster Head (CH) selection. This can achieve high Energy Efficiency (88.7%) and Network Stability (90.8%) [35].

- Low-Power Protocols: Utilize low-power communication protocols and microcontrollers to minimize energy consumption during both active and idle states [33].

- Power Source: Use solar panels to supplement batteries, which is often essential for remote, long-term deployments [33].

Q6: How can I transition my network maintenance strategy from reactive to predictive?

A: Implement condition-based maintenance and predictive models. This involves:

- IoT Sensors: Deploy smart sensors to monitor equipment health and performance in real-time [36] [37].

- Data Analytics: Use AI and machine learning to analyze historical and live sensor data (e.g., vibration, temperature) to forecast component failures [37].

- Proactive Scheduling: Schedule maintenance based on actual equipment condition and predictive insights, rather than on a fixed schedule or after a failure. This can reduce downtime by up to 65% and cut maintenance costs by 40-50% [37].

Table 1: Performance of a Deep Learning-Based Energy Optimization Model

This table summarizes the reported performance of a Deep Learning-based Grouping Model Approach (DL-GMA) for WSNs [35].

| Metric | Performance Value |

|---|---|

| Energy Efficiency | 88.7% |

| Network Stability | 90.8% |

| Network Scalability | 87.1% |

| Congestion Level | 18.3% |

| Quality of Service (QoS) | 93.4% |

Table 2: WSN Deployment Performance in a Wheat Field

This table shows the performance results of a practical WSN deployment for soil property monitoring [34].

| Metric | Performance Value |

|---|---|

| Average Packet Delivery Rate | > 95% |

| Valid Data Rate | > 95% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating Node Deployment Height and Vegetation Impact

Objective: To identify the optimal node deployment height for reliable communication in a specific crop environment.

Materials: Multiple wireless sensor nodes (e.g., ESP32), protective cases, power sources, measuring equipment, RSSI logging software.

Methodology:

- Site Selection: Choose test plots representing different vegetation types (e.g., orchard, grassland, scrubland).

- Configuration: Set up a transmitter node and a receiver node.

- Height Variation: For each vegetation type, test three deployment strategies:

- On-ground: Nodes placed directly on the soil surface.

- Near-ground: Nodes elevated slightly above the ground (e.g., 0.5 - 1 meter).

- Above-ground: Nodes placed high (e.g., 2+ meters), potentially above the canopy.

- Data Collection: At each height configuration, systematically increase the distance between the transmitter and receiver. At each distance, record the Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI).

- Analysis: Determine the maximum coverage distance for each configuration where the RSSI remains above a quality threshold (e.g., >-90 dBm). Analyze the variability in signal quality [33].

Protocol 2: Implementing a Deep Learning-Based Clustering Model for Energy Efficiency

Objective: To maximize network lifetime by optimizing cluster formation and cluster head selection using deep learning.

Materials: Network simulator or testbed with multiple sensor nodes, computing platform for running deep learning models (e.g., with RNN-LSTM capabilities).

Methodology:

- Network Setup: Deploy or simulate a WSN with a defined number of nodes.

- Model Training: Train an RNN with LSTM on historical network data. The model should learn to predict energy consumption patterns and link stability.

- Cluster Formation: Use the trained DL model (DL-GMA) to dynamically group nodes into clusters. The model should consider factors like node proximity, residual energy, and link quality.

- Cluster Head Selection: The DL model selects the most suitable node in each cluster as the Cluster Head (CH), prioritizing nodes with higher energy and better connectivity to the sink.

- Performance Evaluation: Run the network and measure key metrics against a control network without the DL model. Metrics include Energy Efficiency, Network Stability, Network Lifespan, and Quality of Service (QoS) [35].

System Architecture and Workflow Diagrams

WSN Deployment Configurations

Energy-Efficient WSN Cluster Model

Data Flow in a Precision Agriculture WSN

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for WSN Field Deployment

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| ESP32 Microcontroller | A low-cost, low-power system-on-chip with integrated Wi-Fi and Bluetooth, widely used as the core of sensor nodes in agricultural WSNs [33]. |

| Soil Moisture Sensor (e.g., EC-5) | Measures volumetric water content in the soil. Multiple sensors are often deployed at different depths to create a soil moisture profile [34]. |

| Soil Temperature Sensor (e.g., EC-TE) | Measures the soil temperature, a critical parameter for understanding plant growth and biological activity in the root zone [34]. |

| Electrical Conductivity (ECa) Sensor | Measures the apparent electrical conductivity of the soil, which correlates with soil texture, salinity, and other properties [34]. |

| Solar Power System | Provides a sustainable power source for sensor nodes and gateways in remote field locations where grid power is unavailable [33]. |

| Protective Enclosure | A waterproof and dustproof case to protect the sensitive electronics of the sensor node from harsh environmental conditions [33]. |

| Cellular Gateway | A device that aggregates data from the local WSN and uses a long-range cellular network (e.g., 3G/4G) to transmit it to a remote server [34]. |

## Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: The Plant Monitor integration in my smart garden setup does not recognize my Zigbee soil moisture sensor. What should I do?

This is a known device configuration issue. The integration's dropdown menu only populates with entities that have a device_class of moisture. You have two options to resolve this [38]:

- Initial Setup: Leave the soil moisture sensor field blank during the initial plant configuration.

- Post-Setup Action: After setup, use the Developer Tools → Actions menu to run the

plant.replace_sensoraction. You will need to specify the entity of your plant and the entity of your soil moisture sensor [38].

Q2: My sensor readings are accurate in the manufacturer's app but show as "unavailable" in my research data platform. How can I troubleshoot this?

This often indicates a communication or data processing failure within your platform, not necessarily a sensor hardware fault. First, check your platform's diagnostic logs for errors. A common cause is an entity or statistic ID conflict during sensor re-integration, which can manifest as sqlite3.IntegrityError or similar unique constraint failures in the database [39]. Ensure your sensor's integration is correctly configured and that there are no naming conflicts with other entities.

Q3: What are the primary objectives to balance when formulating a sensor placement optimization problem for field conditions?

Sensor placement is inherently a Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) problem. The core objectives to balance are [40]:

- Maximizing Monitoring Performance: This is typically quantified by metrics that act as proxies for state estimation accuracy, such as Mutual Information (MI) or the minimization of reconstruction errors.

- Minimizing Deployment Cost: This includes the financial cost of the sensors themselves and the operational costs associated with installing and maintaining them. Other considerations, such as network reliability and resilience, can also be incorporated into this framework [40].

Q4: My sensor placement optimization is computationally intractable for a large-scale field deployment. What strategies can reduce the model complexity?

High-dimensional spatio-temporal data is a primary driver of computational complexity. Employ the following strategies:

- Use Reduced-Order Models (ROMs): Apply techniques like Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) to decompose the state field into dominant modes, significantly reducing the data dimensionality without substantial loss of information [40] [41].

- Leverage Efficient Algorithms: Implement advanced combinatorial optimization algorithms like the lazy greedy (LG)-∊-constraint method, which provides robust, near-optimal solutions with a theoretically bounded performance, making them suitable for large-scale problems [40].

Q5: How do I handle physical and safety constraints in a real-world sensor placement optimization?

A data-driven greedy algorithm can effectively incorporate user-defined constraints. Your optimization framework must be designed to accept constraints such as [41]:

- Fixed Locations: Certain sensors must be placed at predetermined points.

- Restricted Areas: Specific zones are off-limits for placement due to safety or physical barriers.

- Proximity Requirements: Sensors may need to be a minimum distance apart to avoid interference. The algorithm then optimizes locations over a high-dimensional grid while adhering to these restrictions [41].

Q6: Sensor measurements are inherently noisy. How does optimization account for this uncertainty?

Uncertainty can be explicitly modeled and incorporated into the placement strategy. A common and effective method is to use Gaussian Process (GP) to model the uncertainty in the dominant modes of the system after applying POD [40]. This allows the optimization to place sensors in locations that not only capture the most significant dynamics of the system but also maximize the information gain under uncertainty, leading to more robust and reliable data reconstruction.

## Troubleshooting Guides

### Guide 1: Resolving Integration and Data Availability Issues

Symptoms: Sensors are detected but specific data entities (e.g., soil moisture, light fertility) are unavailable or not displayed in the monitoring platform, even though they work in a secondary app [39].

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Next Step |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify Sensor Pairing | Ensure the sensor is fully and correctly paired with your primary hub (e.g., via ZHA for Zigbee devices). Check all data entities are created. |

| 2 | Inspect System Logs | Review your platform's diagnostic logs for errors. Look for sqlite3.IntegrityError or similar unique constraint failures, which indicate a database conflict [39]. |

| 3 | Reintegrate with Clean Slate | If conflicts are found, you may need to remove the sensor integration, clear its orphaned entities, and then re-pair it. |

| 4 | Use Manual Entity Assignment | If the Plant Monitor integration is the issue, bypass the automatic dropdown by leaving the field blank and using the plant.replace_sensor action to manually assign the correct entity later [38]. |

### Guide 2: Debugging Poor Data Reconstruction Fidelity

Symptoms: The data collected from the deployed sensor network leads to inaccurate reconstructions of the field state (e.g., temperature, moisture maps) with high errors.

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Next Step |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quantify Reconstruction Error | Calculate the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between the reconstructed field and ground-truth measurements to have an objective performance metric [40]. |

| 2 | Validate Sensor Placement | Compare your sensor locations against a Pareto-optimal frontier generated by a multi-objective optimization to see if a better configuration exists for your sensor budget [40]. |

| 3 | Incorporate Physical Constraints | Re-run your placement optimization with all field-specific physical constraints (e.g., no-go zones, minimum sensor spacing) explicitly defined in the model [41]. |

| 4 | Account for Measurement Noise | Ensure your placement strategy uses a formulation like Gaussian Process that is robust to sensor noise, optimizing for information gain under uncertainty [40]. |

## Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

### Performance Comparison of Sensor Placement Algorithms

The following table summarizes the key quantitative results from a computational experiment that benchmarked different sensor placement methods using the Berkeley Intel Lab temperature dataset. The performance was measured by the state estimation accuracy (Testing RMSE) against a ground truth [40].

| Optimization Method | Core Approach | Testing RMSE | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| ROM-based MOO (POD+LG-∊) | Integrated Proper Orthogonal Decomposition with Lazy Greedy ∊-constraint algorithm [40]. | Lowest | High (Designed for large-scale problems) |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | A heuristic search based on principles of natural selection [40]. | Moderate | Moderate |

| Convex Relaxation | Relaxes the discrete placement problem into a continuous, convex one [40]. | Higher | High |

| Standard Greedy | Iteratively selects the best local sensor position [40]. | Varies (Unbounded local optima) | Very High |

### Protocol: Multi-Objective Optimization for Sensor Placement

This protocol details the methodology for determining the Pareto-optimal sensor placements, as cited in the computational experiments [40].

Objective: To find a set of sensor placements that form a Pareto frontier, optimally trading off deployment cost against monitoring performance.

Materials and Dataset:

- Dataset: Spatio-temporal field data (e.g., Berkeley Intel Lab temperature dataset) [40].

- Computing Environment: Software capable of matrix decomposition and combinatorial optimization (e.g., Python with NumPy, SciPy).

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Organize the historical field data into a state matrix where each column represents a sensor location and each row a point in time.

- Model Reduction: Apply Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) to the state matrix. This identifies the dominant spatial modes (POD modes) that capture the most significant variations in the field. Retain the first

rmodes to create a Reduced-Order Model (ROM). - Uncertainty Modeling: Model the uncertainty in the coefficients of the retained POD modes using a Gaussian Process (GP).

- Define Objectives: Formally define the two objective functions:

- f1(x) = -I(x; xc): Negative Mutual Information, to be minimized (this maximizes monitoring performance).

- f2(x) = Cost(x): Total deployment cost, to be minimized.

- Solve MOO Problem: Implement the Lazy Greedy (LG)-∊-constraint algorithm to solve the multi-objective combinatorial optimization. This involves running a series of constrained single-objective optimizations where the cost is constrained by different values of ∊.

- Validation (Optional but Recommended): For a small-scale instance of the problem, validate a subset of the solutions on the Pareto frontier using an exact algorithm like Branch and Bound (BnB) to ensure global optimality.

## The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists the essential computational tools and algorithms that form the "reagent solutions" for advanced sensor placement research.

| Tool / Algorithm | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (POD) | A model reduction technique that decomposes a spatio-temporal field into a minimal set of dominant spatial modes, drastically reducing computational complexity [40]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) | A probabilistic model used to represent the uncertainty in the system's state, allowing for optimal sensor placement that is robust to measurement noise [40]. |

| Lazy Greedy (LG)-∊-constraint | A combinatorial optimization algorithm that efficiently generates the Pareto frontier for the multi-objective sensor placement problem, providing a set of optimal trade-off solutions [40]. |

| Branch and Bound (BnB) | An exact algorithm that can find the globally optimal sensor configuration for validation purposes, though it is often computationally prohibitive for very large problems [40]. |

| Mutual Information (MI) | An information-theoretic metric used as the objective function to maximize the information gain about the unmonitored parts of the field from the sensor measurements [40]. |

## Workflow Visualization

### Sensor Placement Optimization Workflow

### Constraint Handling in Sensor Placement

Troubleshooting Guides

G1: Sensor Data Inconsistencies or Inaccuracies

Q1: My soil moisture sensor readings are erratic or do not match expected values. What are the common causes and solutions?

| Issue | Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Erratic VWC Readings | Air pockets or root-bound substrate creating high variance in reported permittivity [25]. | Inspect sensor tines for gaps or root obstruction. Check data log for high-frequency variance. | Reinstall sensor to ensure full soil contact; consider a new location if roots are invasive [25] [42]. |

| Low VWC Readings | Sensor placed too high in the substrate; induced current does not propagate fully [25]. | Verify sensor placement depth against guidelines (e.g., 1" from bottom for Rockwool). | Reinstall sensor lower in the substrate, closer to the bottom [25]. |

| High VWC Readings | Sensor placed too low in the substrate, sitting in pooled water [25]. | Verify sensor placement depth and check for water accumulation at pot bottom. | Reinstall sensor higher in the substrate relative to the bottom [25]. |

| Inaccurate Readings | Poor soil contact or preferential water flow paths [3] [42]. | Check for gaps between sensor and soil; look for cracks or wormholes directing water. | Reinstall sensor, ensuring firm soil contact; mound soil to prevent preferential flow [3] [42]. |

| Inaccurate Readings | Incorrect soil calibration for the specific soil type [3]. | Compare sensor data with soil sampling and lab analysis. | Select the correct soil type from the sensor's calibration library or use a custom calibration [3]. |

| Data Drift | Influence of temperature on the soil's dielectric permittivity [42]. | Correlate soil moisture data with temperature logs in the absence of irrigation. | Use high-quality sensors with temperature compensation; double-check data to understand correlation [42]. |

Q2: My multi-sensor system is not reporting data from one or more sensors. How do I diagnose this?

- Assumption Check: Systematically test your basic assumptions [43].

- Connection Verification:

- Tool-Based Diagnosis: Use a digital multimeter to check for voltage at the sensor terminals and test for electrical continuity along wires to identify breaks [43].

G2: Data Workflow and Integration Failures

Q3: The data from my different sensors (multi-modal) is misaligned and I cannot fuse it effectively. What is wrong?

- Cause: A lack of temporal synchronization between data streams with different sampling rates [44].

- Solution: Implement temporal alignment techniques during data preprocessing. This can include timestamp matching or using keypoint detection to align data frames across modalities [44].

- Protocol: Intermediate Fusion. Process each sensor modality separately to extract features, then combine these features at an intermediate model layer. This strategy balances the need for modality-specific processing with joint learning and is more tolerant of minor synchronization issues than early fusion [44].

Q4: My data acquisition system is collecting vast amounts of data, but it is noisy and much of it is meaningless. How can I optimize this?

- Principle: Adopt a "less is more" philosophy. Collect only the data necessary to meet your system's demands [45].

- Optimization Steps:

- Right-Size Sampling Rate: Sample at a rate high enough to satisfy the Nyquist Theorem (at least twice the highest signal frequency) but avoid excessively high rates that capture only noise. For slow processes like temperature change, sampling at kHz rates is unnecessary [45].

- Apply Signal Conditioning: Use hardware or software filtering to band-limit the signal and reduce the noise platform before logging [45].

- Verify Data Meaning: Shortly after deployment, graph the collected data and verify that it makes sense and reflects actual physical processes. Look for gaps, noise, or illogical values [45].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary strategies for fusing data from different types of sensors (e.g., soil moisture, temperature, vision)?

The three core multimodal data fusion strategies are [44]:

- Early Fusion (Feature-Level): Combines raw or low-level features from different modalities before feeding them into a model. Best for perfectly synchronized and aligned data.

- Intermediate Fusion (Model-Level): Processes each modality separately to extract features, which are then combined at an intermediate layer of a neural network. Offers a good balance, allowing the model to learn cross-modal interactions.

- Late Fusion (Decision-Level): Each modality is processed independently to make a decision or prediction. These decisions are then combined (e.g., by weighted averaging). Most robust for handling asynchronous data or missing modalities.

Q2: How can I handle a situation where data from one sensor modality is missing or corrupted?

Advanced fusion methods can handle missing data. Techniques include [44]:

- Data Imputation: Estimating the missing values based on other available data.

- Modality Dropout: Training the model with randomly dropped modalities, which teaches it to be robust to missing inputs during inference.

- Leveraging Late Fusion: Since late fusion processes modalities independently, it can naturally accommodate missing ones by adjusting the weighting of the remaining modalities [44].

Q3: What are the best practices for setting up a reliable data acquisition (DAQ) system in field conditions?

- Strategic Data Collection: Collect the minimum necessary data to fulfill the research objective to avoid storage and management issues [45].

- Power Management: Ensure reliable power and regularly check battery levels, especially in remote deployments [43].

- Noise Reduction: Use differential sensor inputs (instead of single-ended) for long cable runs or electrically noisy environments to better reject common-mode noise [45].

- Data Buffering: Enable buffering on interface nodes. This allows data to be stored temporarily if the connection to the central historian is lost, preventing data loss [46].

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates a robust methodology for multimodal sensor fusion, inspired by Bayesian inference and compressed sensing principles, which is particularly useful for handling lossy or subsampled data [47].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Digital Multimeter | Provides independent verification of voltages and checks electrical continuity in sensor wiring [43]. | Essential for basic troubleshooting of power and signal issues. |