CRISPR-Cas9 in Agriculture: A Revolutionary Leap Beyond Traditional Plant Breeding

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and scientists on the transformative advantages of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing over traditional plant breeding methods.

CRISPR-Cas9 in Agriculture: A Revolutionary Leap Beyond Traditional Plant Breeding

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and scientists on the transformative advantages of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing over traditional plant breeding methods. It explores the foundational principles of precision genetic manipulation, detailing specific methodological applications in crop enhancement for traits such as disease resistance, yield, and nutritional quality. The content addresses key technical challenges including delivery optimization and off-target effects, while validating CRISPR's superior efficiency, speed, and precision through comparative analysis with conventional techniques. The synthesis offers critical insights for advancing genetic research and crop development strategies.

From Selective Breeding to Precision Scissors: Understanding the CRISPR Revolution

Plant breeding has long been the cornerstone of agricultural improvement, essential for feeding a growing global population. For centuries, traditional breeding methods, relying on controlled crossing and selection, have been used to develop new crop varieties. However, these conventional approaches are inherently constrained by significant limitations in time, labor, and the randomness of genetic recombination. These bottlenecks slow the pace of innovation, making it difficult to rapidly address emerging challenges such as climate change, new pathogen strains, and global food insecurity [1]. The revolution in genome editing, particularly with the CRISPR/Cas9 system, offers a paradigm shift. This whitepaper details the specific limitations of traditional plant breeding and frames the emergence of CRISPR/Cas9 as a transformative technology that provides precision, speed, and efficiency, thereby overcoming these long-standing hurdles for the research community.

The Inherent Bottlenecks of Traditional Breeding Methodologies

Traditional breeding methods are fundamentally hampered by their reliance on random genetic events and extensive, labor-intensive processes.

The Time-Consuming Nature of Backcross Breeding

A primary method in traditional breeding, cross-pollination between genotypes, requires numerous generations to combine desirable traits from two parents into a single plant line. This process often necessitates many generations of backcrossing over long time periods (over 10 years) before a new, stable crop variety with improved traits is obtained [2]. This slow timeline is ill-suited to addressing urgent agricultural threats.

The Randomness of Conventional Mutagenesis

Conventional mutagenesis methods, including chemical and physical agents, have played a role in generating genetic diversity. Techniques like ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) treatment or gamma-ray irradiation induce a wide range of random mutations throughout the genome [3]. While these methods have contributed to crop improvement, they generate a vast pool of undirected mutations. This randomness necessitates the screening of immense populations to identify the rare individual plants with the desired trait and no deleterious side effects, a process that is both laborious and time-consuming [3].

Table 1: Key Limitations of Traditional Breeding Methods

| Limitation | Manifestation in Traditional Breeding | Consequence for Crop Development |

|---|---|---|

| Time Intensity | Requires 6-8 years or more to breed a new variety [1]; over 10 years for cross-pollination and backcrossing [2]. | Severely delays response to emerging pests, diseases, and market demands. |

| Genetic Randomness | Linkage drag introduces unwanted genes along with desirable ones [1]; conventional mutagenesis creates uncontrolled, genome-wide mutations [3]. | Requires screening of very large populations; difficult to eliminate undesirable traits. |

| High Labor Demand | Need for large-scale field trials and manual phenotypic screening over multiple generations and locations. | Increases research costs and limits the number of breeding programs that can be pursued. |

CRISPR/Cas9: A Paradigm of Precision and Efficiency

In stark contrast to traditional methods, the CRISPR/Cas9 system enables precise, targeted modifications to the plant genome. The system functions as an adaptive immune system in bacteria, engineered for use in plant cells. Its core components are a Cas9 endonuclease that creates double-strand breaks in DNA and a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) that directs the Cas9 to a specific genomic locus [4]. The cell's natural DNA repair mechanisms, primarily Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) or Homology-Directed Repair (HDR), are then harnessed to create the desired genetic change [2].

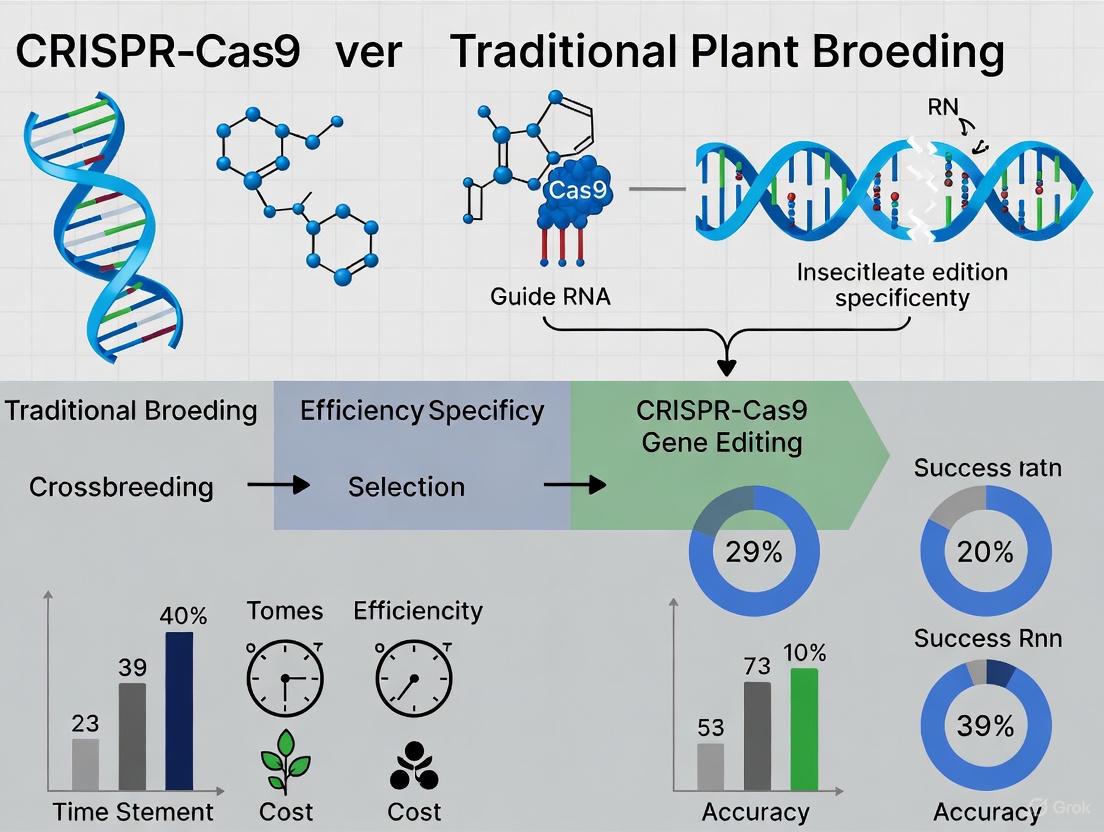

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanism of the CRISPR/Cas9 system and how it introduces targeted genetic changes, contrasting with the randomness of traditional methods.

Diagram 1: The CRISPR/Cas9 Precision Editing Mechanism. This illustrates the targeted creation of double-strand breaks and subsequent DNA repair pathways, a fundamental contrast to random mutagenesis.

Quantitative Comparisons: Traditional Breeding vs. CRISPR/Cas9

The theoretical advantages of CRISPR/Cas9 are borne out in direct, quantitative comparisons with traditional methods across key metrics.

Table 2: Direct Comparison: Traditional Breeding vs. CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing

| Parameter | Traditional Breeding | CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing |

|---|---|---|

| Development Timeline | 6-8 years to over 10 years [2] [1]. | Can dramatically accelerate breeding; specific trait introgressions achieved in a single generation. |

| Genetic Precision | Low; involves mixing entire genomes, leading to linkage drag [1]. | High; enables precise modifications at the single-base pair level [5]. |

| Nature of Genetic Change | Relies on random recombination or random mutagenesis (e.g., EMS, gamma rays) [3]. | Targeted, site-specific modifications directed by sgRNA [4]. |

| Labor & Resource Intensity | High; requires large field populations and multi-generational screening. | Lower; enables focused work on specific loci in a controlled laboratory setting. |

| Regulatory & Public Perception | Well-established but public resistance to transgenic GMOs exists. | Evolving landscape; transgene-free edited plants often face simpler regulatory paths [6] [7]. |

Case Studies and Experimental Protocols

The application of CRISPR/Cas9 in real-world crop improvement projects highlights its efficacy in overcoming the limitations of traditional breeding.

Case Study 1: Engineering Disease-Resistant Cassava

Cassava is a staple food for millions in Africa, but its production is severely threatened by viral diseases. Traditional breeding for resistance is slow and complex.

- Target Trait: Immunity to Cassava Mosaic Virus.

- CRISPR Application: Researchers targeted a gene involved in plant immunity (a susceptibility gene) to create a loss-of-function mutation, thereby increasing resistance to the virus [3].

- Experimental Protocol:

- sgRNA Design: Design sgRNAs complementary to the target susceptibility gene sequence.

- Vector Construction: Clone the sgRNA sequence into a CRISPR/Cas9 expression vector.

- Plant Transformation: Introduce the vector into cassava cells using Agrobacterium-mediated transformation.

- Regeneration and Selection: Regenerate whole plants from transformed cells and select edited lines.

- Molecular Validation: Use PCR amplification of the target locus followed by sequencing to confirm the presence of indel mutations.

- Phenotypic Screening: Infect validated plants with the virus to confirm enhanced resistance [3].

- Outcome: Development of CRISPR-edited cassava plants with natural immunity to the pathogen, a crucial advancement for food security in Sub-Saharan Africa [3] [8].

Case Study 2: Developing Non-Transgenic, Genome-Edited Citrus

The citrus industry faces devastation from Huanglongbing (HLB) disease. A key innovation is creating edited plants without integrating foreign DNA, simplifying regulatory approval.

- Target Trait: Natural immunity to HLB.

- CRISPR Application: Use of a transient expression system to edit genes involved in disease susceptibility without incorporating CRISPR genes into the plant genome [6].

- Experimental Protocol (Transgene-Free Editing):

- Agrobacterium-Mediated Transient Expression: Use Agrobacterium to deliver CRISPR/Cas9 genes into plant cells. The genes are expressed temporarily but not integrated into the plant chromosome.

- Kanamycin Selection (Refined Method): A short 3-4 day kanamycin treatment helps identify cells that were successfully infected and are temporarily expressing the CRISPR genes, enriching for edited cells [6].

- Plant Regeneration: Regenerate plants from the edited cells. Since the CRISPR genes are not integrated, the resulting plants are transgene-free.

- Molecular Analysis: Use next-generation sequencing to detect and characterize the modifications, ensuring the absence of the CRISPR transgene and confirming the desired edit [3] [6].

- Outcome: This refined method was 17 times more efficient than previous versions in producing genome-edited citrus plants, demonstrating a highly efficient pathway to non-GMO, disease-resistant crops [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Based Plant Breeding

Transitioning to CRISPR-based research requires a specific set of molecular tools and reagents.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR/Cas9 Plant Genome Editing

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease Variants | Engineered versions of the Cas9 protein (e.g., high-fidelity Cas9) that introduce double-strand breaks with reduced off-target effects [3]. | Used in RNP complex delivery for transgene-free editing [9]. |

| sgRNA Synthesis Kit | For in vitro transcription or synthesis of target-specific single-guide RNA. | Designing sgRNAs to target genes like OsSWEET13 in rice for blight resistance [3]. |

| Delivery Vector System | A plasmid construct for stable expression of Cas9 and sgRNA in plant cells (e.g., using T-DNA from Agrobacterium tumefaciens). | Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of citrus [6] and stable transformation of Elymus nutans [9]. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes | Pre-assembled complexes of purified Cas9 protein and sgRNA delivered directly into plant protoplasts, avoiding foreign DNA integration. | Used to create transgene-free edited carrot plants [9]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | For high-throughput verification of editing efficiency and detection of potential off-target effects [3]. | Used to analyze edits in citrus and other crops to ensure accuracy [3] [6]. |

The limitations of traditional plant breeding—its protracted timelines, immense labor requirements, and dependence on random genetic events—are fundamental and constraining. CRISPR/Cas9 technology represents a decisive leap forward, offering researchers and scientists a tool of unparalleled precision, speed, and efficiency. By enabling targeted genetic improvements without the baggage of linkage drag and by facilitating the development of non-transgenic crops, CRISPR/Cas9 is not merely an improvement but a necessary evolution in plant breeding. Its continued adoption and refinement are paramount for empowering the global research community to meet the urgent and complex agricultural challenges of the 21st century.

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) system represents a transformative breakthrough in genetic engineering, offering unprecedented precision and efficiency for modifying DNA sequences in living cells [10]. Originally discovered as an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes that defends against viruses or bacteriophages, researchers have harnessed this bacterial defense mechanism to create a highly versatile genome-editing tool [10] [11]. The core innovation of CRISPR-Cas9 lies in its ability to be programmed to target virtually any genomic locus by simply redesigning a short guide RNA sequence, a feature that dramatically simplifies genetic modifications compared to previous technologies [12]. This programmability, combined with its precision, has positioned CRISPR-Cas9 as a powerful tool with vast potential for disease treatment and the creation of genetically modified organisms [11], revolutionizing fields from medicine to agricultural biotechnology.

Core Components of the CRISPR-Cas9 System

The CRISPR-Cas9 system requires two fundamental components to function: the Cas9 nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA). These elements work in concert to identify and cleave specific DNA sequences with remarkable accuracy.

The Cas9 Nuclease: A Molecular Scissor

The Cas9 protein is a large, multi-domain DNA endonuclease that functions as the catalytic engine of the system, responsible for cleaving the target DNA to create a double-stranded break (DSB) [10]. Structurally, Cas9 consists of two primary lobes [10]:

- Recognition Lobe (REC Lobe): Comprising REC1 and REC2 domains, this lobe is primarily responsible for binding to the guide RNA.

- Nuclease Lobe (NUC Lobe): Contains the RuvC and HNH nuclease domains along with the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) interacting domain.

The most commonly used nuclease, SpCas9, is derived from Streptococcus pyogenes and recognizes a specific PAM sequence (5'-NGG-3') adjacent to the target DNA site [10] [12]. The RuvC and HNH domains are each responsible for cleaving one strand of the DNA duplex, together generating a blunt-ended double-strand break approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence [10] [12].

The Guide RNA: A Programmable Navigator

The guide RNA (gRNA) serves as the targeting system that directs Cas9 to a specific genomic location. This RNA component consists of two distinct molecular parts that can be supplied separately or as a single molecule [10] [13]:

- crRNA (CRISPR RNA): Contains the ~20 nucleotide spacer sequence that defines the target DNA through complementary base pairing.

- tracrRNA (trans-activating crRNA): Features a long stretch of loops that serves as a binding scaffold for the Cas9 nuclease.

In practice, these two components are often combined into a single guide RNA (sgRNA) for simplified experimental implementation [10]. The sgRNA forms a complex secondary structure with distinct conserved motifs, including the nexus and two hairpins, which are essential for proper Cas9 binding and function [14]. The targeting specificity of the entire system depends on the 8-10 base pair "seed sequence" at the 3' end of the gRNA spacer, which must perfectly match the target DNA for efficient cleavage to occur [12].

Table 1: Core Components of the CRISPR-Cas9 System

| Component | Structure | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Multi-domain enzyme with REC and NUC lobes | Creates double-stranded breaks in target DNA | Requires PAM sequence (5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9); Contains RuvC and HNH nuclease domains |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | crRNA + tracrRNA (can be combined as sgRNA) | Directs Cas9 to specific genomic targets | ~20 nucleotide spacer defines target specificity; Scaffold region binds Cas9 |

| crRNA | ~20 nucleotide sequence | Provides target recognition through complementarity | Determines genomic targeting; Seed sequence (8-10 bp) is critical for specificity |

| tracrRNA | RNA with hairpin structures | Serves as binding scaffold for Cas9 | Essential for Cas9 activation; Structural component |

The Mechanism of Targeted DNA Cleavage

The CRISPR-Cas9 mechanism operates through a precise sequence of molecular events that can be divided into three distinct stages: recognition, cleavage, and repair.

Target Recognition and Binding

The process begins when the Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complex surveys the genome in search of a complementary DNA sequence adjacent to a valid PAM sequence [10]. The PAM sequence, typically 5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9, serves as an essential recognition signal that distinguishes self from non-self DNA in the native bacterial system [10] [12]. Once Cas9 identifies a potential PAM sequence, it triggers local DNA melting, allowing the seed region of the gRNA to begin annealing to the target DNA [12]. If sufficient complementarity exists between the gRNA spacer and the target DNA, complete hybridization occurs, leading to full activation of the Cas9 nuclease.

DNA Cleavage and Double-Strand Break Formation

Upon successful target binding and verification, Cas9 undergoes a conformational change that positions its nuclease domains for catalytic activity [10]. The HNH domain cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the gRNA spacer sequence, while the RuvC domain cleaves the opposite strand [10] [12]. This coordinated action results in a blunt-ended double-strand break (DSB) approximately 3 base pairs upstream of the PAM sequence [10]. The resulting DSB then triggers the cell's innate DNA repair machinery, which attempts to rectify the damage through one of two primary pathways.

DNA Repair Pathways and Genetic Outcomes

The fate of the CRISPR-induced DNA break depends on which cellular repair mechanism addresses the damage:

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): This dominant repair pathway functions throughout the cell cycle by directly ligating the broken DNA ends without requiring a template [10]. NHEJ is efficient but error-prone, often resulting in small random insertions or deletions (indels) at the cleavage site [10] [12]. When these indels occur within protein-coding exons, they frequently produce frameshift mutations or premature stop codons that effectively knockout gene function [12].

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): This high-fidelity pathway uses a homologous DNA template—either the sister chromatid or an externally supplied donor DNA—to precisely repair the break [10]. HDR is most active during the late S and G2 phases of the cell cycle and enables precise gene insertion or specific nucleotide substitutions when an appropriate donor template is provided [10] [12].

Diagram 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Mechanism: From Target Recognition to DNA Repair. The core pathway shows how the Cas9-gRNA complex identifies target DNA via PAM recognition, creates a double-strand break, and cellular repair pathways (NHEJ or HDR) lead to different genetic outcomes.

Advantages Over Traditional Plant Breeding Methods

CRISPR-Cas9 technology represents a quantum leap beyond conventional plant breeding approaches, offering unprecedented precision, speed, and versatility in crop improvement.

Precision and Efficiency

Unlike traditional breeding methods that rely on random genetic recombination through crossing and selection, CRISPR-Cas9 enables direct, targeted modifications to specific genes without introducing foreign DNA [15]. This precision allows researchers to enhance desirable traits or disable unfavorable ones with minimal unintended effects on the rest of the genome. The technology is particularly valuable for its ability to function without stable integration of foreign DNA into the plant genome, which aligns favorably with regulatory frameworks in many countries [15].

Trait Development Speed

Traditional plant breeding is often labor-intensive and time-consuming, involving multiple cycles of crossing and selection that can take 10-15 years to develop new varieties [15]. In contrast, CRISPR-Cas9 can introduce specific genetic improvements in a single generation, dramatically accelerating the breeding cycle. This efficiency is especially beneficial for developing climate-resilient crops that can address rapidly changing environmental conditions [16] [17].

Applications in Crop Improvement

The agricultural biotechnology sector has leveraged CRISPR-Cas9 to address numerous challenges in crop production:

- Drought Tolerance: Researchers have successfully used CRISPR-Cas9 to edit the StCBP80 gene in potato, resulting in enhanced drought tolerance through improved stomatal regulation and ABA sensitivity [15].

- Disease Resistance: The technology has been applied to develop resistance against various pathogens in crops like maize, wheat, and potato [15] [18].

- Nutritional Enhancement: CRISPR-Cas9 enables biofortification of staple crops by increasing essential vitamins, minerals, and proteins [16] [18].

- Herbicide Tolerance: Development of herbicide-tolerant varieties allows for more effective weed management with reduced environmental impact [18] [19].

Table 2: CRISPR-Cas9 vs. Traditional Plant Breeding Methods

| Characteristic | CRISPR-Cas9 Technology | Traditional Breeding |

|---|---|---|

| Time Required | 1-3 years for trait development | 10-15 years for new varieties |

| Precision | Targets specific genes without affecting rest of genome | Relies on random genetic recombination |

| Genetic Changes | Defined, predictable modifications | Undefined genetic background |

| Regulatory Status | Considered non-GMO in some countries if no foreign DNA integrated | Generally unregulated |

| Trait Stacking | Multiple traits can be edited simultaneously | Requires sequential crossing over generations |

| Resource Requirements | Laboratory-intensive, technical expertise needed | Field-intensive, larger population sizes |

Advanced gRNA Designs and Experimental Optimization

Recent advances in gRNA engineering have significantly improved the efficiency and reliability of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, particularly for previously challenging targets.

Enhanced gRNA Designs

Standard gRNAs can suffer from misfolding or unstable secondary structures that reduce editing efficiency. To address these limitations, researchers have developed:

- GOLD-gRNA (Genome-editing Optimized Locked Design): Incorporates highly stable hairpins in constant regions to prevent misfolding, increasing editing efficiency up to 1000-fold for difficult targets [14].

- Chemically Modified gRNAs: Feature phosphorothioate bonds for terminal nucleotides and internal 2'OMe modifications to improve nuclease resistance and stability [14].

- HEAT sgRNA (Hybridization Extended A-T Inversion): Extends complementary sequences between crRNA and tracrRNA to enhance Cas9 binding [14].

These optimized gRNAs are especially valuable for editing target sites with refractory sequences, such as those containing PAM-proximal GCC motifs that normally block cleavage [14].

Experimental Design Considerations

Successful CRISPR-Cas9 experiments require careful planning and optimization:

- gRNA Design: Select target sequences with minimal off-target potential and ensure proximity to PAM sequence. Design 3-5 gRNAs per target to identify the most efficient variant [12] [13].

- Delivery Methods: Choose appropriate delivery systems based on target cells—physical methods (microinjection, electroporation), carrier-based approaches (lipid nanoparticles), or viral vectors (AAV, lentivirus) [11].

- Validation: Employ genomic cleavage detection assays and sequencing to verify editing efficiency and detect potential off-target effects [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nucleases | SpCas9, Fidelity-enhanced variants (eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1, HypaCas9), PAM-flexible variants (xCas9, SpCas9-NG) | DNA cleavage with varying specificity profiles and PAM requirements [12] |

| gRNA Formats | Synthetic sgRNA, crRNA:tracrRNA duplex, GOLD-gRNA, Chemically modified gRNAs | Target recognition with different efficiency and stability characteristics [12] [14] |

| Delivery Systems | Electroporation, Lipid nanoparticles, AAV vectors, Lentiviral vectors, Microinjection | Introduction of CRISPR components into target cells [11] |

| Detection & Validation | T7E1 assay, TIDE analysis, NGS-based methods, Sanger sequencing | Assessment of editing efficiency and off-target profiling [13] |

| Control Reagents | Validated control gRNAs, Non-targeting gRNAs, Mock transfection controls | Experimental normalization and specificity confirmation [13] |

The core mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9—centered on the programmable gRNA and Cas9 nuclease—represents a fundamental breakthrough in genetic engineering with profound implications for agricultural biotechnology. The system's precision, efficiency, and versatility offer distinct advantages over traditional plant breeding methods, enabling targeted improvements in crops with unprecedented speed and accuracy. As gRNA designs continue to evolve and delivery methods improve, CRISPR-Cas9 is poised to play an increasingly vital role in addressing global challenges in food security, climate resilience, and sustainable agriculture. The technology's ability to make precise genetic modifications without introducing foreign DNA positions it as a transformative tool for the future of crop improvement, potentially bridging the gap between conventional breeding and genetic engineering while addressing regulatory and consumer concerns.

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 technology represents a paradigm shift in plant biotechnology, offering unprecedented precision, efficiency, and speed in crop improvement compared to conventional breeding methods. This whitepaper delineates the key technological milestones in the journey of CRISPR-Cas9 from its origins as a bacterial immune system to its current status as a transformative tool in plant breeding. Framed within a broader thesis on its benefits over traditional breeding, this analysis provides a comprehensive technical guide for researchers and drug development professionals. Quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and essential research toolkits are synthesized to demonstrate how CRISPR-Cas9 surmounts the limitations of traditional approaches, enabling the rapid development of crops with enhanced yield, climate resilience, and nutritional profiles to address global food security challenges.

Plant breeding, the science of improving plant genetics to develop desirable traits, has evolved from millennia of selective cultivation to highly precise genetic intervention. Conventional breeding techniques—including selective breeding, hybridization, and mutation breeding—rely on the artificial selection of phenotypic traits over multiple generations, a process often spanning 8-15 years from conception to commercial release [20]. While these methods have historically sustained agricultural productivity, they are inherently limited by their dependence on existing genetic variation, long reproductive cycles, and extensive land resources.

The global plant breeding market, valued at approximately $8.91 billion in 2025, is projected to reach $13.86 billion by 2030, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.2% [18]. This growth is largely propelled by biotechnological methods, with the CRISPR-enabled segment emerging as a significant driver. This whitepaper posits that CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing constitutes a fundamental advancement over traditional plant breeding by providing molecular-level precision, radically accelerated timelines, and the ability to engineer complex traits unattainable through conventional means. The following sections will dissect the technology's journey and provide the technical scaffolding for its application in modern crop development.

Historical Trajectory: From Bacterial Immunity to a Genetic Engineering Tool

The CRISPR-Cas system originated as an adaptive immune mechanism in prokaryotes, protecting bacteria and archaea from viral infections. The seminal discovery of this system revealed a mechanism where bacteria integrate short sequences of invading viral DNA into their own genomes—creating Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR). These sequences, when transcribed, guide Cas (CRISPR-associated) proteins to cleave complementary foreign DNA upon re-infection [21].

The repurposing of this system for genetic engineering began in earnest following key publications in 2012 that established its programmability. The system was simplified into a two-component tool comprising a Cas9 nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA). The gRNA, with its ~20 nucleotide targeting sequence, directs Cas9 to a specific genomic locus where the enzyme induces a double-strand break. The cell's subsequent repair of this break—via either error-prone Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) or precise Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)—enables targeted gene knockout, insertion, or modification [21].

The application of this technology in plants was rapidly demonstrated in 2013 in model species like Nicotiana benthamiana and Arabidopsis thaliana, and shortly thereafter in staple crops such as rice and wheat [21]. This marked a critical milestone, proving that CRISPR-Cas9 could function effectively within the complex genomic landscapes of plants, thereby opening a new frontier in plant biotechnology.

Quantitative Superiority: CRISPR-Cas9 vs. Traditional Breeding

The quantitative advantages of CRISPR-Cas9 over traditional breeding are profound, impacting timelines, precision, and economic efficiency. The data below provides a comparative analysis.

Table 1: A Comparative Analysis of Breeding Key Parameters

| Parameter | Traditional Breeding | CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Breeding |

|---|---|---|

| Development Timeline | 8-15 years [20] | 3-5 years [22] |

| Generations per Year | 1-2 (for most crops) [20] | 4-6 (enabled by speed breeding) [20] |

| Genetic Precision | Low; involves mixing thousands of genes via crossing | High; enables precise modification of single or few genes [21] |

| Trait Stacking Efficiency | Low; requires successive backcrossing over many generations | High; enables simultaneous editing of multiple genes/traits [23] |

| Dependence on Sexual Compatibility | Yes; limits gene pool to crossable species | No; allows direct modification of the native genome [21] |

Table 2: Market and Economic Impact Comparison

| Aspect | Traditional Breeding | CRISPR-Cas9 Breeding | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Projected Market Growth (CAGR) | Part of overall market at ~9.2% | Specific segment growing at ~14.77% (overall CRISPR market) [24] | |

| Time to Market for New Varieties | ~10 years (including regulatory approval) | Significantly reduced; breeding cycle "drastically reduced" [20] | |

| Cost & Resource Implications | High field trial costs over many years | More economical and time-efficient; "relatively cheaper" [21] |

Technical Guide: Implementing CRISPR-Cas9 in Plant Systems

The following section provides a detailed, generalized protocol for CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in plants, synthesizing methodologies from successful case studies in crops like tomato and larch [25] [26] [23].

Experimental Workflow for Plant Genome Editing

The end-to-end process from target selection to the analysis of edited plants involves multiple critical steps, as visualized below.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experimental Steps

Step 1: gRNA Design and Vector Construction

- Target Selection: Identify a 20-nucleotide target sequence adjacent to a 5'-NGG-3' Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) within the gene of interest. Use online tools (e.g., http://skl.scau.edu.cn/targetdesign/) to minimize off-target effects [26].

- Oligonucleotide Synthesis: Synthesize complementary oligonucleotides corresponding to the target sequence with 5' overhangs compatible with the chosen cloning system (e.g., BsaI for Golden Gate assembly) [25].

- Plasmid Assembly: Using the Golden Gate cloning system, anneal and ligate the oligonucleotides into a BsaI-digested binary vector (e.g., pYLCRISPR/Cas9P35S-N) behind a U6 promoter [25] [26]. The vector contains the Cas9 gene driven by a constitutive promoter like CaMV 35S or a strong endogenous promoter (e.g., LarPE004 in larch) [23].

- Transformation into Agrobacterium: The final construct is transformed into an Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain such as EHA105 for subsequent plant transformation [26].

Step 2: Plant Transformation and Regeneration

- Explant Preparation: Surface sterilize seeds and excise cotyledons or other explants from sterile plantlets. For species like Fraxinus mandshurica, growing points from embryos are used [26].

- Agrobacterium Co-cultivation: Infect explants with an Agrobacterium suspension (OD₆₀₀ optimized between 0.5-0.8) in a transformation solution (e.g., containing MES, acetosyringone, sucrose, and mannitol) for a specified duration [26]. For protoplast-based systems, polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated transfection is used [23].

- Selection and Regeneration: Transfer co-cultivated explants to a selective regeneration medium (e.g., Woody Plant Medium for trees) containing antibiotics to eliminate Agrobacterium and a selective agent (e.g., kanamycin at 20-70 mg/L) to select for transformed plant cells. Induce shoot and root formation under controlled environmental conditions [25] [26]. The protocol for tomato yields approximately 10 Cas-positive independent lines from 100 transformed cotyledons [25].

Step 3: Molecular and Phenotypic Analysis

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Extract DNA from regenerated plantlets using a commercial kit.

- Mutation Detection: Perform PCR amplification of the target genomic region. Analyze the products via Sanger sequencing and use tools like TIDE or DECODR to quantify editing efficiency. For the FmbHLH1 gene in Fraxinus mandshurica, an editing efficiency of 18% was confirmed in induced clustered buds [26].

- Homozygous Plant Selection: Regenerate multiple generations (T0, T1) via a clustered bud system or self-pollination to segregate and identify homozygous lines devoid of the Cas9 transgene [26].

- Phenotypic Evaluation: Subject homozygous knockout lines and wild-type controls to physiological stress assays. For drought tolerance evaluation, measure indicators like reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging ability and osmotic adjustment under polyethylene glycol (PEG)-simulated drought conditions [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of CRISPR-Cas9 in plants requires a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Plant CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Vector System | Delivers gRNA and Cas9 nuclease into plant cells. | pYLCRISPR/Cas9P35S-N vector [25]. Endogenous promoters (e.g., LarPE004 in larch) can enhance efficiency [23]. |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens Strain | Mediates stable integration of T-DNA into the plant genome. | EHA105 [26]. |

| Plant Growth Media | Supports growth, regeneration, and selection of transformed tissues. | Woody Plant Medium (WPM) for trees [26]; Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium for many dicots. |

| Selection Agents | Eliminates non-transformed cells and selects for positive events. | Kanamycin (optimal concentration must be determined empirically, e.g., 20-70 mg/L) [26]. |

| Transformation Solution Additives | Enhances Agrobacterium virulence and transformation efficiency. | Acetosyringone (120 μM), MES buffer, DTT, Sucrose, Mannitol [26]. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolates high-quality genomic DNA for screening. | Commercial plant genomic DNA extraction kit [26]. |

| PCR & Sequencing Reagents | Amplifies and sequences the target locus to confirm editing. | High-fidelity DNA polymerase, Sanger sequencing services [26]. |

The trajectory of CRISPR-Cas9 from a fundamental biological curiosity in bacteria to a cornerstone of plant biotechnology marks one of the most significant scientific advancements of the past decade. The quantitative data and technical protocols detailed in this whitepaper unequivocally demonstrate its superior efficacy, precision, and speed compared to traditional breeding paradigms. For researchers and drug development professionals, the adoption of CRISPR-Cas9 is no longer merely an option but a strategic imperative to address the urgent challenges of climate change, population growth, and sustainable agriculture. As regulatory frameworks evolve and the technology continues to mature with developments like base editing and prime editing, CRISPR-Cas9 is poised to unlock a new era of innovation in crop improvement and molecular farming.

CRISPR-Cas9 technology represents a paradigm shift in plant breeding, offering unprecedented precision, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness compared to conventional methods. This revolutionary gene-editing system functions as a programmable molecular scissor, enabling researchers to make targeted modifications to specific DNA sequences with exceptional accuracy [27]. While traditional breeding relies on phenotypic selection and cross-hybridization—processes that are often time-consuming and imprecise—CRISPR-Cas9 operates at the nucleotide level, allowing for direct trait manipulation without introducing foreign DNA [28] [29]. This technical guide examines the fundamental advantages of CRISPR-Cas9 through quantitative data, experimental protocols, and visual workflows, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive resource for leveraging this transformative technology in agricultural biotechnology.

Quantitative Advantages of CRISPR-Cas9

The superiority of CRISPR-Cas9 over traditional plant breeding methods becomes evident when examining key performance metrics across multiple parameters. The following tables summarize comprehensive comparative data.

Table 1: Direct Comparison of CRISPR-Cas9 vs. Traditional Breeding Methods

| Parameter | Traditional Breeding | CRISPR-Cas9 | Reference/Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Required for Trait Introduction | 7-15 years [27] | 1-3 years [27] | Rice grain yield improvement [27] |

| Typical Editing Precision | Chromosomal segments (imprecise) | Single nucleotide [27] | Site-specific mutagenesis [30] |

| Mutation Efficiency | Variable, relies on random recombination | Nearly 100% success rate achievable [30] | P3a mutagenesis method [30] |

| Editing Specificity | Non-targeted (entire genome) | High (with guide RNA targeting) | gRNA-directed Cas9 protein [27] |

| Regulatory Status | Generally exempt | Evolving, often favorable vs. GMOs [18] | U.S., Japan, and other markets [18] |

Table 2: Economic and Output Impact of CRISPR-Cas9 in Crop Development

| Metric | Impact Level | Evidence/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Yield Improvement | 25-31% increase [27] | Rice variety with edited abscisic acid genes [27] |

| Disease Resistance | 5x greater output [27] | Rice blast-resistant varieties [27] |

| Market Growth Rate | 13.00% CAGR (2025-2034) [31] | Global CRISPR-based gene editing market [31] |

| Commercial Adoption | Rapid expansion in Asia Pacific [18] | Supportive regulations in China, India, Japan [18] |

Experimental Protocols for CRISPR-Cas9 Implementation

Workflow for Plant Genome Editing

The standard CRISPR-Cas9 workflow involves sequential steps from target identification to validation. The following diagram illustrates this process:

Methodologies for Quantifying Editing Efficiency

Accurately detecting and quantifying CRISPR edits is crucial for developing robust plant genome editing applications. The following experimental methods represent the current standard approaches, particularly when analyzing heterogeneous populations from transient expression-based approaches [32].

Targeted Amplicon Sequencing (AmpSeq)

Protocol Objective: To achieve gold standard quantification of editing efficiency with high sensitivity and accuracy [32].

Materials & Reagents:

- DNA extraction kit (e.g., CTAB-based methods)

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., Q5, SuperFi II)

- PCR purification kit

- Next-generation sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina)

Procedure:

- Extract genomic DNA from CRISPR-treated plant tissue (≥100mg)

- Design primers flanking the target site (amplicon size: 300-500bp)

- Amplify target region using high-fidelity polymerase (30-35 cycles)

- Purify PCR products and quantify using fluorometry

- Prepare sequencing library with dual-indexing approach

- Sequence on appropriate NGS platform (minimum 10,000 reads/sample)

- Analyze sequences using bioinformatics tools (e.g., CRISPResso2)

Technical Notes: AmpSeq detects editing frequencies as low as 0.1% and provides comprehensive mutation profiling, but requires specialized facilities and has higher cost per sample [32].

PCR-Capillary Electrophoresis/InDel Detection by Amplicon Analysis (PCR-CE/IDAA)

Protocol Objective: To rapidly quantify editing efficiency with high accuracy compared to AmpSeq [32].

Materials & Reagents:

- Fluorescently-labeled PCR primers (FAM, HEX, or TET)

- Standard Taq polymerase

- Capillary electrophoresis system (e.g., ABI 3500)

- Size standard (e.g., GS600 LIZ)

Procedure:

- Extract genomic DNA from CRISPR-treated tissue

- Amplify target region with fluorescent forward primer and unlabeled reverse primer (30 cycles)

- Dilute PCR products 1:20-1:50 in molecular grade water

- Mix 1μl diluted PCR product with 8.7μl Hi-Di formamide and 0.3μl size standard

- Denature at 95°C for 5 minutes, then immediately cool on ice

- Run samples on capillary electrophoresis system (injection parameters: 1.2kV for 24s)

- Analyze fragment sizes and peak areas using specialized software

Technical Notes: PCR-CE/IDAA accurately quantifies major indels when benchmarked against AmpSeq, has moderate cost, and provides rapid turnaround, but may miss complex mutation patterns [32].

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR)

Protocol Objective: To achieve absolute quantification of editing efficiency without standard curves [32].

Materials & Reagents:

- ddPCR supermix for probes

- Target-specific FAM and HEX-labeled probes

- Droplet generator and reader

- DG8 cartridges and gaskets

Procedure:

- Design hydrolysis probes targeting wild-type and edited sequences

- Prepare 20μl reaction mix: 10μl ddPCR supermix, 1μl each primer (900nM final), 0.5μl each probe (250nM final), 50ng genomic DNA, nuclease-free water to volume

- Generate droplets using droplet generator (approximately 20,000 droplets/sample)

- Transfer droplets to 96-well PCR plate and seal

- Amplify using touch-down PCR: 95°C for 10min; 40 cycles of 94°C for 30s, 60°C (-0.5°C/cycle) for 1min; 72°C for 2min; 98°C for 10min; 4°C hold

- Read plate on droplet reader

- Analyze data using quantification software to determine editing percentage

Technical Notes: ddPCR provides high precision for frequency quantification, has good sensitivity, but requires specialized equipment and probe design [32].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Plant Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerases | Q5, SuperFi II [30] [32] | High-fidelity amplification for vector construction and amplicon sequencing; critical for P3a mutagenesis [30] |

| CRISPR Delivery Vectors | pIZZA-BYR-SpCas9, pBYR2eFa-U6-sgRNA [32] | Dual geminiviral replicon system for transient co-expression in N. benthamiana leaves [32] |

| Detection Enzymes | T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) [32] | Mismatch cleavage assay for initial editing screening; moderate sensitivity but low cost [32] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | CTAB-based methods [32] | Reliable DNA isolation from plant tissues containing polysaccharides and polyphenols |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina systems [32] | AmpSeq for gold standard validation; enables detection of low-frequency edits (≥0.1%) [32] |

| Capillary Electrophoresis | ABI 3500 series [32] | Fragment analysis for PCR-CE/IDAA method; balances accuracy with throughput [32] |

Technological Mechanisms and Workflows

Molecular Mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9

The core CRISPR-Cas9 system functions through a targeted DNA recognition and cleavage mechanism. The following diagram details this process:

The CRISPR-Cas9 mechanism begins with the formation of a ribonucleoprotein complex between the Cas9 enzyme and a synthetic guide RNA (gRNA) [27]. This complex scans the genome for complementary DNA sequences adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), typically 5'-NGG-3' for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 [27]. Upon recognition, Cas9 induces a double-strand break (DSB) 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM site [27]. The cellular repair mechanisms then activate, primarily through error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), which often results in insertion/deletion mutations (indels) that disrupt gene function, or less frequently, through homology-directed repair (HDR) when a donor DNA template is provided, enabling precise gene modifications [27].

Method Selection Workflow for Editing Quantification

Selecting the appropriate quantification method requires consideration of multiple experimental factors:

CRISPR-Cas9 technology represents a transformative advancement in plant breeding, offering substantial improvements in precision, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness over conventional methods. The quantitative data presented demonstrates reductions in development timelines from decades to years, precision at the single-nucleotide level, and significant enhancements in crop yield and disease resistance [27]. The experimental protocols and reagent toolkit provide researchers with practical resources for implementation, while the visualization of workflows clarifies the molecular mechanisms and methodological decision-making processes. As the field evolves with emerging improvements like P3a mutagenesis with nearly 100% efficiency [30] and AI-enhanced guide RNA design [31], CRISPR-Cas9 is poised to become increasingly indispensable for researchers and drug development professionals addressing global food security challenges.

Precision in Practice: Methodologies and Crop Enhancement Applications

The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has revolutionized plant biotechnology, offering a precise and efficient alternative to traditional breeding methods. While traditional breeding relies on cross-pollination and selection over multiple generations—a process that can take years and is limited by species barriers—CRISPR-Cas9 enables direct, targeted genetic modifications in a single generation while preserving the elite genetic background of existing cultivars [33]. This technological leap significantly accelerates the development of plants with improved traits, such as enhanced stress resistance, increased yield, and improved nutritional quality [34].

The practical application of CRISPR-Cas9 in plants hinges on effective delivery methods that introduce editing components into plant cells. The three primary techniques—Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, protoplast transformation, and biolistic delivery—each possess distinct characteristics, advantages, and limitations. These methods facilitate the introduction of CRISPR-Cas9 as DNA, RNA, or preassembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes [33] [34]. The choice of delivery system significantly impacts critical factors including editing efficiency, the potential for transgene integration, and the feasibility of regenerating transgene-free edited plants, all of which are crucial considerations for both research and commercial applications [35] [34].

Comparative Analysis of Delivery Methods

The following sections provide a detailed technical examination of each delivery method, focusing on their mechanisms, applications, and protocol considerations.

Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation

Mechanism and Workflow: Agrobacterium tumefaciens is a naturally occurring soil bacterium genetically engineered to deliver a segment of DNA (T-DNA) from its tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid into the plant genome [36] [37]. In the context of CRISPR-Cas9, the genes encoding the Cas9 nuclease and guide RNA (gRNA) are cloned into the T-DNA region of a binary vector. Upon co-cultivation of Agrobacterium with plant explants (e.g., leaf discs, embryos, or suspension cells), the T-DNA is transferred and integrated into the plant genome, leading to stable transformation [37].

Key Applications and Optimizations: This method is widely used for stable transformation and has been successfully adapted for transient expression systems. For instance, in sunflower, highly efficient (exceeding 90%) transient transformation was achieved using optimized protocols involving Agrobacterium strain GV3101 at OD₆₀₀ of 0.8 with 0.02% Silwet L-77 surfactant, using infiltration, injection, or ultrasonic-vacuum methods [38]. A highly efficient transformation of photosynthetic Arabidopsis suspension cells was also achieved using the hypervirulent AGL1 strain, co-cultivation on solidified medium, and the addition of AB minimal salts and Pluronic F68 surfactant [36].

Protoplast-Mediated Transformation

Mechanism and Workflow: This method involves the enzymatic removal of the plant cell wall to create protoplasts—naked plant cells surrounded by a plasma membrane [39]. These protoplasts are then transformed using polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated transfection or electroporation to introduce CRISPR-Cas9 components, which can be in the form of plasmid DNA, RNA, or RNPs [33] [40]. After transformation, the protoplasts are cultured in a sequence of media designed to regenerate a new cell wall, undergo cell division to form microcalli, and ultimately regenerate into whole plants [39].

Key Applications and Optimizations: Protoplast transformation is particularly valuable for DNA-free editing using RNPs, which eliminates the risk of transgene integration and produces genetically modified plants that may be classified as non-GMO in some regulatory frameworks [33]. A optimized protocol for grapevine (Chardonnay) achieved a protoplast yield of approximately 75 × 10⁶ per gram of leaf material with 91% viability and a transformation efficiency of 87% [39]. Similarly, PEG-mediated transformation has been successfully used to edit the phytoene desaturase (CnPDS) gene in coconut protoplasts [40]. A significant challenge, however, lies in the regeneration of whole plants from protoplasts, which remains difficult for many plant species, including grapevines [39].

Biolistic Delivery (Particle Bombardment)

Mechanism and Workflow: The biolistic method uses high-velocity microprojectiles (typically gold or tungsten particles coated with DNA, RNA, or proteins) to physically deliver genetic material into plant cells [34]. This process is performed using a gene gun device, such as the Bio-Rad PDS-1000/He system. The coated particles are accelerated by a helium pulse and penetrate the cell walls and membranes of the target plant tissues, which can include immature embryos, meristems, or other explants [34].

Key Applications and Optimizations: Biolistics is renowned for its species independence, making it the preferred method for transforming plants recalcitrant to Agrobacterium infection [34]. A significant recent advancement is the development of a flow guiding barrel (FGB) for the gene gun. Computational fluid dynamics revealed that the conventional device's design caused turbulent flow and significant particle loss. The 3D-printed FGB creates a uniform laminar flow, directing nearly 100% of the loaded particles to the target with twice the velocity and four times the coverage area [34]. This innovation has dramatically improved performance, achieving a 22-fold increase in transient GFP-DNA transfection in onion epidermis, a 4.5-fold increase in CRISPR-Cas9 RNP editing efficiency, and a 10-fold improvement in stable transformation frequency in maize B104 embryos [34]. It also doubled the efficiency of in planta CRISPR-Cas12a-mediated genome editing in wheat meristems [34].

Comparative Data and Workflow Visualization

Quantitative Method Comparison

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of the three delivery methods based on recent research.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery Methods in Plants

| Delivery Method | Editing Efficiency (On-Target) | Off-Target Mutations | Unwanted Plasmid Integration | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium-mediated | High (in chicory CiGAS genes) [33] | Not detected (in studied chicory off-targets) [33] | Not applicable (integration is intentional for stable lines) | Stable integration; low copy number; ability to transfer large DNA fragments [36] [37] | Genotype dependence; chimerism in T0 plants; risk of vector backbone integration [33] |

| Protoplast (RNP Delivery) | High (in chicory CiGAS-S1/S2); lower for mismatched targets [33] | Not detected (in studied chicory off-targets) [33] | 0% (DNA-free method) [33] | Non-transgenic edited plants; no foreign DNA integration; high editing efficiency [33] [39] | Difficult regeneration for many species; technical complexity of protoplast culture [39] |

| Protoplast (Plasmid Delivery) | High (in chicory CiGAS genes) [33] | Not detected (in studied chicory off-targets) [33] | ~30% [33] | Useful for transient assays; high efficiency in optimized systems [39] | High rate of unwanted plasmid integration [33] |

| Biolistic (with FGB) | 4.5-fold increase in RNP editing in onion [34] | Data not provided in sources | Can be avoided with RNP delivery | Species/tissue independent; delivers diverse cargo (DNA, RNA, RNP); improved efficiency with FGB [34] | Can cause tissue damage; potentially complex transgene insertions [34] |

Experimental Workflow and Method Selection

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for creating genome-edited plants using the three delivery methods, highlighting key decision points.

Diagram 1: Workflow for Plant Genome Editing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of plant genome editing protocols requires specific biological and chemical reagents. The following table details key solutions used in the featured methods.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Cas9 Delivery in Plants

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example Usage in Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Hypervirulent Agrobacterium Strains (AGL1, GV3101) | Mediates efficient T-DNA transfer from bacterium to plant cells. | Used for transforming Arabidopsis suspension cells and sunflower cotyledons [36] [38]. |

| Acetosyringone | A phenolic compound that induces the Agrobacterium vir genes, enhancing T-DNA transfer. | Added to the co-cultivation medium at 200 µM [36]. |

| Pluronic F68 | A non-ionic surfactant that reduces fluid shear stress and improves cell viability during transformation. | Added to the co-cultivation medium to increase transformation efficiency of suspension cells [36]. |

| Silwet L-77 | A surfactant that reduces surface tension, promoting the spreading and infiltration of Agrobacterium suspension into plant tissues. | Used at 0.02% in transient transformation of sunflower seedlings [38]. |

| Mannitol Solution (0.6 M) | An osmoticum used for pre-plasmolysis of plant tissues, improving protoplast yield and viability during isolation. | Used as a pre-treatment during grapevine protoplast isolation [39]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A polymer that promotes the fusion of plasma membranes and facilitates the uptake of DNA or RNPs into protoplasts. | Used for PEG-mediated transformation of coconut and grapevine protoplasts [39] [40]. |

| Macerozyme R-10 & Cellulase R-10 | Enzyme mixtures used to digest cell wall components (pectin and cellulose) for protoplast isolation. | Core components of the enzymatic solution for digesting grapevine leaf tissue [39]. |

| Gold Microcarriers (0.6 µm) | Microscopic particles that serve as projectiles to carry DNA, RNA, or proteins into cells during biolistic transformation. | Coated with plasmid DNA, RNA, or RNPs for bombardment using a gene gun [34]. |

| Preassembled CRISPR-Cas9 RNP Complex | The complex of Cas9 protein and guide RNA; the DNA-free editing entity that minimizes off-target effects and prevents transgene integration. | Delivered via protoplast transfection or biolistics to create non-transgenic edited plants [33] [34]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protoplast Isolation and Transformation (Grapevine)

This protocol, adapted from recent research, outlines an efficient procedure for isolating and transforming protoplasts from grapevine leaves [39].

- Plant Material Preparation: Use young, fully expanded leaves from in vitro-grown grapevine (e.g., Chardonnay) plants. Sterilize leaves by submerging in 5.25% sodium hypochlorite for 1 minute, followed by 70% ethanol for 2 minutes, and rinse four times with sterile distilled water.

- Protoplast Isolation:

- Strip-cutting: Place the sterilized leaf on filter paper and gently shred it into 0.5–1.0 mm strips using a razor blade, discarding the petiole.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Transfer the strips to an enzymatic solution (e.g., containing Macerozyme R-10 and Cellulase R-10 in 0.6 M mannitol). Incubate in the dark for 16 hours with gentle shaking.

- Purification: Filter the digested mixture through a 40 µm nylon mesh to remove debris. Centrifuge the filtrate to pellet the protoplasts. Resuspend the pellet in a W5 solution (154 mM NaCl, 125 mM CaCl₂, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MES, pH 5.7) and purify further by floating on a sucrose gradient (0.6 M sucrose). Count protoplasts using a hemocytometer; expected yield is approximately 75 × 10⁶ protoplasts per gram of fresh weight with >90% viability [39].

- PEG-Mediated Transformation:

- Collect ~2 × 10⁵ protoplasts by centrifugation and resuspend in 100 µL of MMG solution (0.6 M mannitol, 15 mM MgCl₂, 4 mM MES, pH 5.7).

- Add 10 µg of plasmid DNA or a preassembled RNP complex.

- Add an equal volume (110 µL) of 40% PEG 4000 solution (dissolved in 0.6 M mannitol and 0.1 M CaCl₂). Mix gently and incubate at room temperature for 15–30 minutes.

- Dilute the mixture stepwise with W5 solution, centrifuge to remove PEG, and resuspend the transformed protoplasts in 1 mL of culture medium.

- Culture and Regeneration: Culture the protoplasts in liquid or solid MS medium supplemented with 2 mg/L 2,4-D and 0.5 mg/L BA to facilitate microcalli formation. Transfer developed calli to regeneration media to induce shoot and root organogenesis. Note that regeneration remains a significant bottleneck in grapevine and many other species [39].

Optimized Biolistic Transformation with Flow Guiding Barrel (FGB)

This protocol leverages the FGB to significantly enhance biolistic transformation efficiency [34].

- Microcarrier Preparation:

- Weigh 60 mg of 0.6 µm gold particles into a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Add 1 mL of 100% ethanol, vortex thoroughly, and let sit for 15 minutes. Centrifuge briefly and discard the supernatant.

- Wash the particles three times with 1 mL of sterile distilled water.

- Resuspend the gold particles in 1 mL of sterile 50% glycerol.

- For DNA delivery, aliquot 50 µL of the gold suspension, add 5 µL of DNA (1 µg/µL), 50 µL of 2.5 M CaCl₂, and 20 µL of 0.1 M spermidine. Vortex for 10 minutes. For RNP delivery, coat the particles with the preassembled complex following a similar co-precipitation protocol.

- Centrifuge briefly, remove the supernatant, and wash with 140 µL of 100% ethanol. Finally, resuspend in 48 µL of 100% ethanol.

- Bombardment Setup and Execution:

- Sterilize the FGB device and the gene gun chamber with 70% ethanol.

- Pipette 10 µL of the coated gold suspension onto the center of a macrocarrier and let it dry.

- Place the rupture disk, macrocarrier, stopping screen, and target tissue (e.g., onion epidermis, maize immature embryos) at the optimized distances within the PDS-1000/He system according to the manufacturer's instructions and the FGB specifications.

- Perform the bombardment at the desired helium pressure (e.g., 1100 psi). The FGB allows for a longer target distance and lower pressure while maintaining high efficiency [34].

- Post-Bombardment Culture:

- For transient assays, incubate the bombarded tissues under standard growth conditions for 24–48 hours before analysis.

- For stable transformation, transfer the tissues to appropriate recovery and selection media. The FGB has been shown to enable a 10-fold increase in stable transformation frequency in maize B104 embryos and allows for a higher throughput of up to 100 embryos per bombardment plate [34].

The choice of delivery method for CRISPR-Cas9 in plants is a critical determinant of experimental and breeding outcomes. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation offers efficient stable integration but can be limited by genotype dependence and the potential for chimerism. Protoplast transformation is a powerful route for DNA-free, transgene-free editing but is often hampered by the formidable challenge of plant regeneration. Biolistic delivery provides unparalleled species independence and is uniquely suited for RNP delivery in species where protoplast regeneration is not feasible, with its efficiency being dramatically enhanced by recent engineering innovations like the FGB [33] [39] [34].

Within the broader thesis on CRISPR-Cas9's benefits over traditional breeding, these delivery methods are the essential enabling technologies. They allow for precise genetic improvements without disrupting the genetic background of elite cultivars—a key advantage over traditional crossing, which introduces thousands of unknown genes through linkage drag. As these delivery systems continue to be refined, particularly through improvements in efficiency and the facilitation of transgene-free editing, they will further accelerate the development of improved crop varieties to meet global agricultural challenges.

The stability of global food systems is increasingly threatened by abiotic stresses, including drought, salinity, and extreme temperatures, which are intensifying due to climate change [41] [42]. These stresses significantly suppress crop growth, development, and yield, posing severe risks to food security for a growing population [43] [44]. Traditional plant breeding methods, while responsible for historical improvements in crop yields, are often described as labor-intensive and time-consuming, typically requiring nine to eleven years to develop a new commercial variety [41] [44] [42]. Furthermore, conventional breeding is limited by its reliance on existing genetic variation and the complex, polygenic nature of most abiotic stress tolerance traits [45].

The advent of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 genome editing technology has revolutionized plant biotechnology by enabling precise, efficient, and targeted genetic modifications [43] [44]. Unlike traditional genetic engineering, which often involves introducing foreign DNA, CRISPR-Cas9 can generate transgene-free plants with specific, desirable edits in a single generation. This technical guide outlines the application of CRISPR-Cas9 for enhancing drought, salinity, and thermotolerance in crops, providing detailed methodologies, key genetic targets, and experimental data, all framed within its demonstrable advantages over conventional plant breeding research.

Core Principles of CRISPR-Cas9 and Its Superiority to Traditional Breeding

The CRISPR-Cas9 Mechanism

The CRISPR-Cas9 system functions as a versatile and precise genome-editing tool derived from a bacterial adaptive immune system [43] [46]. Its core components are:

- The Cas9 endonuclease, which creates double-stranded breaks (DSBs) in DNA.

- A single-guide RNA (sgRNA), a synthetic RNA molecule that combines the functions of CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA). The sgRNA directs the Cas9 protein to a specific genomic locus complementary to its 20-nucleotide spacer sequence [46].

A critical requirement for Cas9 cleavage is the presence of a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) immediately downstream of the target sequence. For the most commonly used Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3' [46]. Upon binding, the Cas9 protein cleaves the DNA, creating a DSB. The cell then repairs this break through one of two primary pathways:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone repair process that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels). These indels can disrupt the coding sequence of a gene, leading to a loss of function [43] [46].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise repair mechanism that uses a donor DNA template to introduce specific nucleotide changes or insertions [43].

Advantages Over Traditional and Transgenic Methods

CRISPR-Cas9 offers several distinct advantages that make it superior to traditional breeding and earlier biotechnological approaches for stress resilience research:

- Precision and Speed: CRISPR-Cas9 allows for direct modification of specific genes or regulatory sequences controlling stress responses, bypassing the need for multiple, lengthy backcrossing generations required in conventional breeding [44] [42]. For instance, domesticating wild tomato with improved traits was achieved in just 3 years with CRISPR, compared to a decade using earlier methods [47].

- Multiplexing Capability: The system can be engineered to target multiple genes simultaneously by expressing several sgRNAs. This is particularly valuable for improving complex polygenic traits like drought tolerance, where multiple genetic pathways may need coordinated adjustment [43].

- Expanded Genetic Diversity: It can create novel genetic variations and de-domesticate genes to reintroduce valuable traits lost during centuries of cultivation, moving beyond the constraints of a crop's existing gene pool [47].

- Regulatory and Acceptance Benefits: CRISPR can generate transgene-free edited plants by segregating out the Cas9 and sgRNA constructs in subsequent generations. These products are often subject to less stringent regulations compared to traditional genetically modified (GM) crops, facilitating a smoother path to commercialization [48] [46].

Table 1: Comparison of Plant Breeding and Genetic Improvement Techniques

| Feature | Conventional Breeding | Transgenic (GMO) Approach | CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Required | 9-11 years or more [44] | Varies, includes long regulatory processes [42] | Significantly reduced (e.g., 3 years for tomato domestication [47]) |

| Precision | Low; involves mixing entire genomes | Medium; introduces entire foreign gene(s) | High; enables precise nucleotide-level changes |

| Genetic Variation | Limited to sexually compatible species | Can introduce genes from any organism | Can create novel variation within the species' own genome |

| Multiplexing | Extremely difficult and time-consuming | Complex | Relatively straightforward with multiple sgRNAs [43] |

| Final Product | Cross-bred variety | Transgenic plant | Can be a non-transgenic, edited plant [48] |

Targeted Pathways and Key Genes for Abiotic Stress Tolerance

Understanding the molecular mechanisms of plant stress responses is crucial for identifying effective targets for genome editing. The following sections and tables summarize key genes that have been successfully engineered to enhance tolerance.

Drought Tolerance

Drought stress triggers a cascade of physiological and molecular responses in plants, including stomatal closure to reduce water loss, accumulation of protective osmolytes, and activation of stress-responsive signaling pathways [41] [49]. A central regulator of these responses is the phytohormone abscisic acid (ABA), which controls stomatal aperture and the expression of numerous drought-responsive genes [41]. The ABA-responsive element-binding proteins (AREBs)/ABRE-binding factors (ABFs), which are basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors, are major mediators of ABA signaling and promising targets for editing [41].

Table 2: Key Gene Targets for Enhanced Drought Tolerance via CRISPR-Cas9

| Gene(s) Edited | Gene Function | CRISPR Editing Strategy & Outcome | Experimental Validation & Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| AREB1/ABF2 (e.g., in Arabidopsis, soybean, rice) | ABA-dependent transcription factor; master regulator of drought response genes [41] | Overexpression via promoter editing or loss-of-function to study mechanism. AREB1 overexpression improves drought tolerance [41]. | Studies in model plants show AREB1 controls a broad range of genes downstream of ABA signaling, enhancing antioxidant signaling and osmotic stress response [41]. |

| OsERA1 | β-subunit of farnesyltransferase; negative regulator of drought response [43] | Knock-out to enhance ABA sensitivity and reduce water loss. | Mutant rice plants showed reduced stomatal conductance, increased ABA sensitivity, and superior survival under drought stress [43]. |

| Abscisic Acid Receptors (e.g., in rice) | Proteins involved in sensing ABA and initiating stress signaling [47] | Targeted mutagenesis to alter receptor function. | Mutations in a subfamily of these receptors resulted in a 25-31% increased grain yield in field tests in China [47]. |

Salinity Tolerance

Salinity stress imposes both osmotic and ionic damage on plants, leading to oxidative stress and nutrient imbalance [48] [45]. Enhancing salinity tolerance involves improving ion homeostasis (e.g., by regulating sodium transporters) and reinforcing the plant's antioxidant and osmoprotection systems.

Table 3: Key Gene Targets for Enhanced Salinity Tolerance via CRISPR-Cas9

| Gene(s) Edited | Gene Function | CRISPR Editing Strategy & Outcome | Experimental Validation & Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| OsRR22 (in rice) | B-type response regulator transcription factor involved in cytokinin signaling and metabolism [48] | Knock-out to enhance salinity tolerance. | Homozygous mutant rice lines showed significantly enhanced salinity tolerance at the seedling stage with no negative impact on agronomic traits [48]. |

| OsHAK1 (in rice) | Potassium transporter; crucial for maintaining K+/Na+ homeostasis under salt stress [48] | Knock-out to study gene function. | Mutants exhibited increased sensitivity to salt stress, confirming the gene's role in salinity tolerance [48]. |

| SNAC1, DST, SKC1 (in rice) | Various functions including transcription regulation and ion transport [48] | Knock-out or targeted mutagenesis to improve stress response. | These genes have been successfully cloned and are considered prime candidates for CRISPR editing to improve salt tolerance [48]. |

Thermotolerance

Heat stress disrupts protein folding, membrane integrity, photosynthetic efficiency, and reproductive development [46]. Key mechanisms for thermotolerance include the expression of Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs) as molecular chaperones, the activation of the antioxidant system to scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS), and the accumulation of protective osmolytes [46].

Table 4: Key Gene Targets for Enhanced Thermotolerance via CRISPR-Cas9

| Gene(s) Edited | Gene Function | CRISPR Editing Strategy & Outcome | Experimental Validation & Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| OsMDHAR4 (in rice) | Monodehydroascorbate reductase; involved in ROS scavenging [46] | Knock-out to modulate ROS signaling. | Mutant plants exhibited greater tolerance to high temperatures by mediating H2O2-induced stomatal closure [46]. |

| Thermotolerance Genes (e.g., encoding HSPs, HSFs) | Chaperones and transcription factors that protect proteins from heat-induced damage [46] | Knock-out to identify and validate gene function. | CRISPR is widely used to understand the genetic basis of heat stress by creating knockouts of both tolerance and susceptibility genes [46]. |

| Ca2+ Signaling Genes (in rice) | Components of calcium signaling pathways that regulate stress responses [46] | Knock-out to decipher role in thermotolerance. | Research is ongoing to understand the function of cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels in calcium signaling under heat stress [46]. |

The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways through which plants perceive and respond to these abiotic stresses, and highlights key intervention points for CRISPR-Cas9 editing.

Diagram Title: CRISPR Targets in Abiotic Stress Signaling

Detailed Experimental Protocol for CRISPR-Cas9 Workflow

This section provides a step-by-step methodology for conducting a CRISPR-Cas9 experiment aimed at enhancing abiotic stress tolerance, using the successful editing of the OsRR22 gene in rice for salinity tolerance as a model [48].

Target Selection and sgRNA Design

- Identify Target Gene: Based on literature and functional studies, select a target gene known to influence stress tolerance (e.g., OsRR22 for salinity tolerance in rice) [48].

- Design sgRNA: Identify a 20-nucleotide target sequence immediately upstream of a 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequence within the coding or regulatory region of the gene.

- Check Specificity: Perform a BLAST search of the target sequence (including the PAM) against the host plant's genome to ensure specificity and minimize off-target effects. The target sequence should have a difference of at least two bases compared with similar non-target sequences [48].

Vector Construction

- Assemble CRISPR Vector: Use established cloning systems, such as the pYLCRISPR/Cas9Pubi-H vector system.

- Synthesize gRNA Expression Cassette: The target-specific sequence is incorporated into primers and synthesized via overlapping PCR using a template like pYLgRNA-OsU6a/LacZ [48].

- Clone into Expression Vector: The final gRNA fragment is cloned into the BsaI site of the Cas9 plant expression vector. The resulting binary construct will typically contain:

- A Cas9 expression cassette (e.g., driven by a Ubi promoter).

- The sgRNA expression cassette (driven by a U6 promoter).

- A selectable marker cassette (e.g., Hygromycin resistance, HPT) for plant transformation [48].

Plant Transformation and Regeneration

- Transformation: Introduce the binary vector into Agrobacterium tumefaciens and use it to transform the target plant material. For rice, this is typically done using embryogenic calli induced from mature seeds [48].

- Selection and Regeneration: Culture the transformed calli on hygromycin-containing medium to select for positive events. Transfer vigorously growing, resistant calli to regeneration media to generate transgenic plants (T0 generation) [48].

Molecular Identification of Mutants

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from the leaves of T0 transgenic plants.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the genomic region flanking the CRISPR target site using gene-specific primers.

- Mutation Analysis: Sequence the PCR products directly or after cloning into a sequencing vector. Compare the sequences with the wild-type to identify mutations (indels). Homozygous, heterozygous, or biallelic mutations can be decoded through Sanger sequencing and degenerate sequence decoding [48].

Segregation of T-DNA

- Generate Transgene-Free Plants: Grow the T1 progeny of the T0 mutants. Identify plants that harbor the desired gene mutation but have lost the Cas9/sgRNA T-DNA through genetic segregation. This is confirmed by PCR using primers specific to the Cas9 or HPT genes, which should yield no product [48].

Phenotypic Evaluation of Mutants

- Stress Assays: Subject the T2 homozygous mutant lines and wild-type controls to controlled stress conditions.

- For Salinity Tolerance (OsRR22 example): Grow seedlings in a nutrient solution, then expose them to salt stress (e.g., NaCl). Assess tolerance by comparing survival rates, biomass, and physiological parameters between mutant and wild-type plants [48].

- For Drought Tolerance: Withhold water and measure parameters like relative water content, stomatal conductance, and survival rate.

- For Thermotolerance: Expose plants to high temperatures and assess membrane stability, photosynthetic efficiency, and yield components.

- Agronomic Trait Analysis: Under normal growth conditions, compare the mutant lines with wild-type plants for key agronomic traits such as plant height, yield, and grain quality to ensure no yield penalties are introduced [48].

The following diagram visualizes this multi-stage experimental workflow.

Diagram Title: CRISPR Workflow for Stress-Tolerant Crops

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of a CRISPR-Cas9 project for abiotic stress tolerance requires a suite of specific reagents and tools. The following table details essential components and their functions.

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments in Plants

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Specifics & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Endonuclease | The enzyme that creates double-stranded breaks in the target DNA. | Available as full-length, nickase (nCas9), or catalytically dead (dCas9) for advanced applications. Variants like SaCas9 are smaller for easier delivery [43]. |

| sgRNA Expression Vector | Plasmid carrying the sequence for the single-guide RNA under a suitable promoter (e.g., U6). | Vectors like pYLgRNA are commonly used. The sgRNA is designed with a 20-nt target-specific sequence [48]. |