CRISPR vs. Traditional Genetic Modification: A Comparative Analysis for Modern Drug Development and Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of CRISPR-based gene editing and traditional genetic modification (GM) methods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

CRISPR vs. Traditional Genetic Modification: A Comparative Analysis for Modern Drug Development and Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of CRISPR-based gene editing and traditional genetic modification (GM) methods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational mechanisms of both platforms, from Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) and TALENs to the RNA-guided CRISPR-Cas systems. The scope extends to methodological applications in drug target discovery, functional genomics, and therapeutic development, alongside a critical examination of technical challenges such as off-target effects and delivery optimization. Finally, it offers a rigorous validation and comparative assessment of precision, efficiency, scalability, and regulatory landscapes, synthesizing key insights to guide strategic tool selection in biomedical research and clinical translation.

From ZFNs to CRISPR: Unpacking the Core Mechanisms of Gene Editing Platforms

The field of genetic engineering has undergone a profound transformation, moving from the broad-stroke approaches of traditional genetic modification to the precision editing of contemporary techniques like CRISPR-Cas9. This shift represents not merely a technical improvement but a fundamental change in how researchers approach genetic interventions. Traditional genetic modification (GM) techniques, which involve the random insertion of foreign genetic material into a host genome, have been complemented and in many cases supplanted by genome editing platforms that enable precise, targeted modifications without necessarily introducing foreign DNA [1]. This evolution has created new possibilities in both basic research and therapeutic development while simultaneously generating complex regulatory and ethical questions that the scientific community continues to navigate. Understanding the distinctions between these technological paradigms is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working at the frontier of genetic science.

Fundamental Mechanistic Divergences

Traditional Genetic Modification: Random Integration

Traditional GM techniques rely on the random insertion of foreign DNA sequences into a host genome. This process typically involves using recombinant DNA technology to isolate genes from one species and introduce them into another, often distantly related species [1]. A classic example is the incorporation of genes from the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) into crops like cotton and corn to confer inherent insect resistance [1]. The random nature of this integration means that the foreign DNA can insert into any location within the genome, potentially disrupting existing genes, regulatory elements, or causing unintended pleiotropic effects [1]. The process depends on Agrobacterium-mediated transformation or biolistic methods (gene gun) to deliver the genetic constructs, with selectable marker genes (often antibiotic resistance genes) used to identify successfully transformed organisms [1].

Contemporary Genome Editing: Precision Targeting

Contemporary genome editing, particularly CRISPR-Cas systems, operates on a fundamentally different principle: precise targeting using RNA-guided nucleases. The CRISPR-Cas9 system consists of two core components: the Cas9 nuclease, which creates double-strand breaks in DNA, and a guide RNA (gRNA) that directs the nuclease to a specific genomic locus complementary to its sequence [2] [3]. This targeting is further specified by the requirement of a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence adjacent to the target site [3]. Once the double-strand break is introduced, the cell's innate DNA repair mechanisms are harnessed to achieve the desired genetic outcome:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone repair pathway that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the cut site, effectively disrupting the target gene and creating a knockout [3].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise repair pathway that uses a DNA template to introduce specific modifications, including point mutations or gene insertions [3].

This precision enables modifications ranging from single nucleotide changes to gene insertions, all at predetermined genomic locations, offering unprecedented control over genetic outcomes.

Table 1: Core Mechanistic Differences Between Traditional GM and Genome Editing

| Feature | Traditional GM | Contemporary Genome Editing (CRISPR) |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Material Introduced | Typically foreign DNA from other species | Can be edits to existing genes without foreign DNA [1] |

| Integration Site | Random and unpredictable [1] | Precise and targetable [2] |

| Targeting Mechanism | Non-specific insertion | RNA-guided nuclease with sequence complementarity [3] |

| Repair Mechanism Utilized | Non-homologous recombination | NHEJ or HDR [3] |

| Typical Modification Scale | Large DNA segments | Single nucleotides to small insertions [3] |

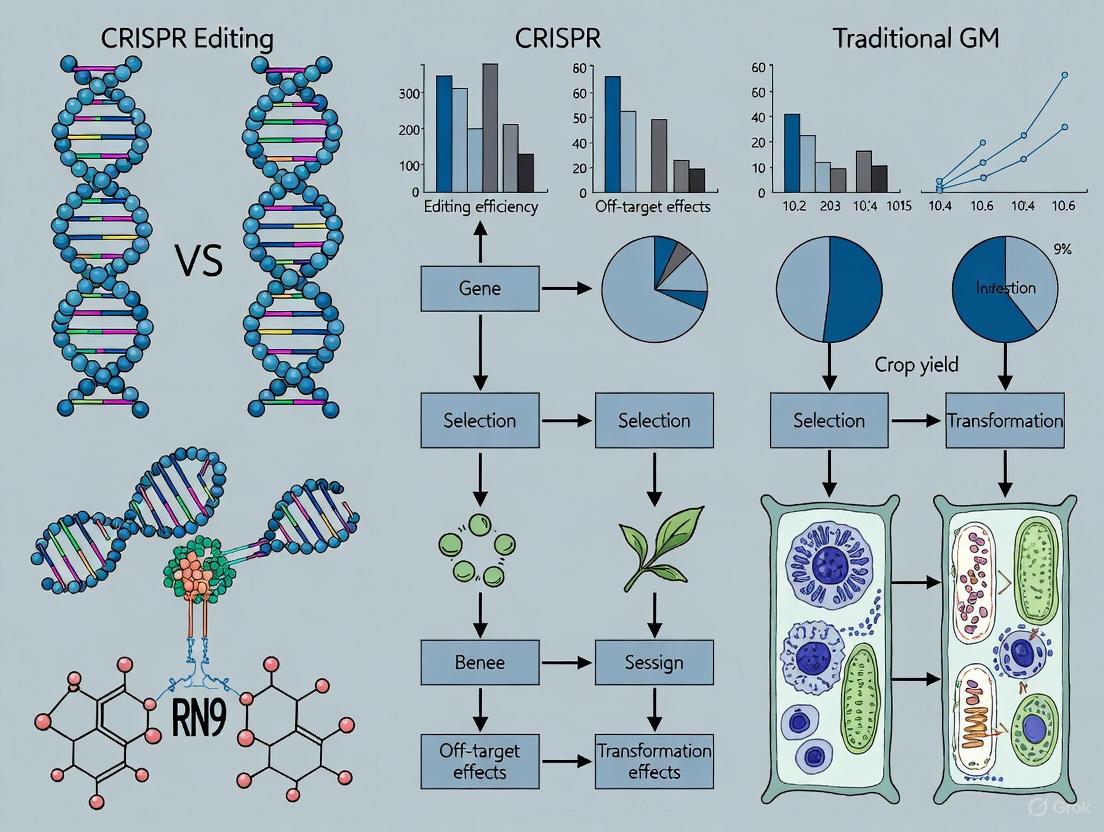

Figure 1: Comparative Workflows of Traditional GM and CRISPR Genome Editing

Technical Comparison: Efficiency, Precision, and Applications

Specificity and Unintended Effects

The precision of genetic interventions varies substantially between traditional and contemporary approaches. Traditional GM techniques are characterized by random integration events, which can lead to unpredictable disruption of native genes, alteration of regulatory elements, or positional effects that influence transgene expression [1]. In contrast, CRISPR-based editing offers targeted specificity through complementary base pairing between the gRNA and the target DNA sequence. However, CRISPR is not without its limitations regarding off-target effects, where the Cas9 nuclease may cleave sites with sequence similarity to the intended target [4] [3]. Studies have reported off-target activity frequencies of ≥50% for certain CRISPR constructs [3], though this varies significantly based on guide RNA design, Cas9 variant, and cell type.

Multiple strategies have been developed to mitigate CRISPR off-target effects:

- Computational guide design: Bioinformatic tools identify unique target sequences with minimal off-target potential [4].

- Engineered Cas variants: High-fidelity Cas9 proteins (e.g., SpCas9-HF1, eSpCas9) with reduced off-target activity [4].

- Modified guide RNAs: Truncated or chemically modified gRNAs with improved specificity [4].

- Alternative delivery methods: Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes instead of plasmid DNA reduce temporal exposure [4].

- Advanced detection methods: Genome-wide approaches like GUIDE-seq and CIRCLE-seq identify off-target sites [4].

Table 2: Analytical Comparison of Editing Platforms

| Parameter | Traditional GM | ZFNs/TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting Specificity | Random integration | Protein-DNA recognition | RNA-DNA complementarity |

| Off-Target Risk | Position effects, disruption | Moderate | Moderate to High (guide-dependent) [3] |

| Efficiency | Variable, depends on transformation | Moderate | High [2] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited | Difficult | High (multiple gRNAs) [2] |

| Development Timeline | Months to years | Months | Weeks [2] |

| Relative Cost | High | High | Low [2] |

Applications in Research and Therapeutics

The applications of traditional GM versus contemporary editing reflect their fundamental mechanistic differences. Traditional GM has been predominantly used in agriculture for introducing traits like herbicide tolerance (e.g., Roundup Ready system) [5] and insect resistance (Bt crops) [1], and in biopharmaceutical production (e.g., recombinant insulin). While effective, these applications typically involve adding new genetic functions rather than correcting existing sequences.

CRISPR editing has expanded these possibilities dramatically:

- Functional genomics: High-throughput knockout screens to identify essential genes and synthetic lethal interactions [2].

- Disease modeling: Precise introduction of disease-associated mutations in cell lines and animal models [2] [6].

- Gene therapy: Direct correction of pathogenic mutations in monogenic disorders like β-thalassemia and sickle cell anemia [2] [3].

- Agricultural improvements: Non-browning mushrooms, gluten-free wheat, disease-resistant citrus and cacao [7].

- Multiplexed editing: Simultaneous modification of multiple genetic loci [2].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Delivery Methods

Efficient delivery of genetic material into target cells remains a critical challenge for both traditional and contemporary approaches. Traditional GM predominantly relies on:

- Agrobacterium-mediated transformation: Particularly for plants [1].

- Biolistic methods: Particle bombardment for organisms recalcitrant to Agrobacterium transformation [1].

- Viral vectors: Retroviruses, lentiviruses, and adenoviruses for animal cells [3].

Contemporary editing platforms utilize both viral and non-viral delivery systems:

- Viral vectors: Adeno-associated viruses (AAV) commonly used for in vivo therapeutic delivery [3].

- Physical methods: Electroporation, microinjection, and nanoparticle-mediated delivery [2].

- Chemical methods: Lipid-based transfection and polymer-based reagents [2].

- Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes: Direct delivery of preassembled Cas9-gRNA complexes offering rapid activity and reduced off-target effects [4].

Analytical and Validation Methods

Rigorous validation of genetic modifications is essential for both research integrity and therapeutic safety. Traditional GM validation typically includes:

- Southern blotting: To confirm transgene integration and copy number.

- PCR analysis: To detect presence of the inserted sequence.

- Expression analysis: RT-qPCR, Western blot, or immunohistochemistry to confirm transgene expression.

CRISPR editing requires additional specificity assessments:

- Targeted deep sequencing: Of both on-target and predicted off-target sites [4].

- GUIDE-seq: Genome-wide, unbiased identification of DSBs enabled by sequencing [4].

- BLESS: Direct in situ breaks labeling, enrichment on streptavidin, and next-generation sequencing [4].

- Digenome-seq: In vitro nuclease-digested whole genome sequencing [4].

- T7E1 assay or Tracking assay: To detect nuclease-induced mutations [4].

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Genome Editing Experiments

| Reagent/Method | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Targets Cas nuclease to specific DNA sequence | Design impacts efficiency and specificity; avoid off-target sites [4] |

| Cas9 Nuclease | Creates double-strand breaks at target sites | Multiple variants available with different PAM requirements and fidelity [8] |

| Repair Templates | Provides homology for HDR-mediated precise editing | Single-stranded or double-stranded DNA donors; design depends on edit type |

| Delivery Vehicles | Introduces editing components into cells | Viral (AAV, lentivirus) vs. non-viral (electroporation, lipofection) [3] |

| Selectable Markers | Enriches for successfully modified cells | Antibiotic resistance, fluorescence; can be excised after selection [1] |

| Off-Target Detection Assays | Identifies unintended edits | GUIDE-seq, CIRCLE-seq, targeted sequencing [4] |

Regulatory and Safety Considerations

The regulatory landscape for genetically modified organisms varies significantly across jurisdictions and reflects the technical distinctions between traditional GM and genome editing. The fundamental regulatory question centers on whether gene-edited organisms should be classified and regulated similarly to traditional GMOs [1] [9].

- United States: USDA has deregulated certain CRISPR-edited crops, especially those without foreign DNA (SDN-1 and SDN-2 modifications) [1].

- European Union: Court of Justice ruling classified gene-edited organisms as GMOs, subject to existing strict regulations [1].

- Argentina and Brazil: Implemented product-based regulatory approaches focusing on the presence of "novel combinations of genetic material" [9].

- Global Governance: The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety provides an international framework, though key countries like the U.S. and Canada are not parties [9].

Safety considerations also differ between the technologies. Traditional GM raises concerns about:

- Allergenicity: Potential for novel proteins to trigger allergic responses [5].

- Antibiotic resistance: Use of antibiotic resistance markers in selection [5].

- Environmental impact: Gene flow to wild relatives, effects on non-target organisms [5].

CRISPR editing introduces distinct considerations:

- Off-target effects: Unintended modifications at similar genomic sequences [3].

- Mosaicism: Incomplete editing in some cells of the target organism [6].

- Immunogenicity: Immune responses against bacterial-derived Cas proteins in therapeutic applications [3].

- Long-term stability: Persistence of edits through cell divisions and generations.

Future Directions and Emerging Technologies

The field of genome editing continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising technologies emerging beyond standard CRISPR-Cas9 systems:

- Base editing: Enables direct, irreversible conversion of one DNA base to another without double-strand breaks, reducing indel formation [2].

- Prime editing: Offers precise small edits, insertions, and deletions without donor templates [2].

- AI-designed editors: Machine learning approaches generating novel editors with optimized properties [8].

- Epigenome editing: Targeted modification of epigenetic marks without changing DNA sequence.

- RNA editing: Precise modification of RNA transcripts for reversible therapeutic effects.

These advancements continue to blur the lines between traditional genetic modification and precision editing, while simultaneously raising new technical and ethical considerations for the research community.

The landscape of genetic engineering has fundamentally shifted from the random integration of foreign DNA characteristic of traditional GM to the precision targeting of contemporary genome editing platforms like CRISPR-Cas9. This transition has enabled unprecedented control over genetic modifications, with applications spanning basic research, therapeutic development, and agricultural improvement. While both approaches continue to have relevance in specific contexts, the precision, efficiency, and versatility of contemporary editing platforms have positioned them as the dominant technology for most research applications. However, technical challenges remain, particularly regarding off-target effects, delivery efficiency, and tissue-specific editing. Furthermore, the evolving regulatory landscape continues to shape the application of these technologies across different domains and jurisdictions. As the field advances with emerging technologies like base editing and AI-designed editors, researchers must maintain a nuanced understanding of both the technical capabilities and the ethical implications of these powerful genetic tools.

Before the advent of CRISPR-Cas9, the field of genome engineering was revolutionized by two groundbreaking protein-based technologies: Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) and Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs). These engineered nucleases provided researchers with the first tools for making targeted, precise modifications to genomes in a wide range of cell types and organisms [10] [11]. Both technologies operate on a similar principle: they fuse a customizable, sequence-specific DNA-binding domain to a non-specific DNA cleavage domain, creating molecular scissors that can induce double-strand breaks at predetermined genomic locations [10]. The cellular repair of these breaks—either through error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR)—enables a broad range of genetic modifications, from gene knockouts to precise nucleotide changes [10] [11]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of ZFNs and TALENs, examining their mechanisms, efficiencies, specificities, and practical applications in modern biological research and therapeutic development.

Molecular Mechanisms and Architectural Designs

Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs): Modular Protein Assembly

ZFNs are fusion proteins comprising an array of engineered Cys2-His2 zinc finger DNA-binding domains attached to the catalytic domain of the FokI restriction endonuclease [10] [11]. Each zinc finger domain recognizes approximately 3 base pairs (bps) in the DNA major groove, with multiple fingers (typically 3-6) assembled in tandem to recognize contiguous 9-18 bp sequences [10] [12]. The FokI nuclease domain requires dimerization for activation, necessitating the design of two ZFN subunits that bind opposite DNA strands at sequences flanking the target site, with the dimerization inducing a double-strand break in the intervening spacer region [12] [11].

The modular assembly of zinc finger arrays presented significant engineering challenges. While zinc finger domains have been developed to recognize most of the 64 possible nucleotide triplets, zinc fingers assembled in arrays can exhibit context-dependent effects where the specificity of neighboring fingers influences overall DNA-binding affinity [10] [12]. This complexity made the rational design of effective ZFNs challenging for nonspecialists, though modular assembly systems and open-source component libraries were developed to address these limitations [10] [11].

Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs): Deciphered Code

TALENs similarly fuse DNA-binding domains to the FokI nuclease domain but utilize a different architectural principle derived from transcription activator-like effector (TALE) proteins of Xanthomonas bacteria [10] [11]. The DNA-binding domain consists of a series of 33-35 amino acid repeats, each recognizing a single DNA base pair [10]. Specificity is determined by two hypervariable amino acids at positions 12 and 13, known as repeat-variable diresidues (RVDs), which follow a simple recognition code: NI for adenine, NG for thymine, HD for cytosine, and NN for guanine/adenine [10] [11].

Unlike ZFNs, TALE repeats operate independently without significant neighbor effects, making TALEN design more straightforward and predictable [10] [12]. Like ZFNs, TALENs function as pairs binding opposite DNA strands, with FokI dimerization creating a double-strand break in the spacer region (typically 14-20 bp) between the binding sites [12].

Figure 1: Molecular Architecture of ZFNs and TALENs. Both systems utilize FokI nuclease domains that require dimerization for activation, but differ in their DNA recognition mechanisms: ZFNs use zinc finger arrays that recognize 3bp per module, while TALENs use TALE repeats that recognize 1bp per module through a simple RVD code.

Performance Comparison: Efficiency, Specificity, and Experimental Data

Quantitative Comparison of Editing Performance

Direct comparative studies provide valuable insights into the relative performances of ZFNs, TALENs, and the contemporary benchmark CRISPR-Cas9. A systematic comparison using GUIDE-seq methodology to evaluate genome-wide specificity at human papillomavirus 16 (HPV16) target sites revealed substantial differences in off-target profiles [13] [14].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Editing Efficiency and Specificity Across Platforms

| Platform | Target Gene | On-Target Efficiency | Off-Target Count | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZFN | HPV16 URR | High | 287-1,856 [14] | High specificity when properly designed [15] | Context-dependent finger effects [12] |

| TALEN | HPV16 E7 | High | 36 [14] | Simple design rules, modular assembly [10] | Large repeat size challenges delivery [2] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 | HPV16 E7 | High | 4 [14] | Easy design, multiplexing capability [2] | Off-target concerns with standard Cas9 [2] |

In bovine and dairy goat fetal fibroblasts, CRISPR-Cas9 demonstrated significantly higher knock-in efficiency compared to both ZFNs and TALENs. For enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) knock-in, CRISPR-Cas9 achieved 77.02% efficiency compared to 13.68% for ZFNs—approximately 5.6-fold higher [16]. Similarly, for humanized Fat-1 (hFat-1) knock-in, CRISPR-Cas9 achieved 79.01% efficiency while ZFNs failed to produce any knock-in events [16]. In direct comparison with TALENs, CRISPR-Cas9 showed more than double the knock-in efficiency for both eGFP (70.37% vs. 32.35%) and hFat-1 (74.29% vs. 26.47%) [16].

Experimental Protocols for Efficiency and Specificity Assessment

Gene Knock-in Efficiency Protocol

The comparative study of knock-in efficiencies in bovine and dairy goat fetal fibroblasts followed this methodology [16]:

Nuclease Design: ZFNs and CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids were designed to target exon 2 of the bovine myostatin (MSTN) gene; TALENs and CRISPR/Cas9 targeted exon 2 of the dairy goat β-casein gene.

Donor Construction: Donor plasmids were constructed in the GFP-PGK-NeoR plasmid backbone containing 5' and 3' homologous arms flanking either hFat-1 or eGFP transgenes.

Cell Transfection: ZFNs, TALENs, or CRISPR/Cas9 plasmids were co-transfected with donor plasmids into fetal fibroblasts via electroporation.

Selection and Cloning: After G418 (Geneticin) selection, single cells were isolated using mouth pipetting, flow cytometry, or a cell shove.

Analysis: Gene knock-in events were screened by PCR across homologous arms, with efficiencies calculated as the percentage of successfully edited clones.

GUIDE-seq Off-Target Detection Protocol

The genome-wide unbiased identification of double-stranded breaks enabled by sequencing (GUIDE-seq) method was adapted for ZFNs and TALENs as follows [13] [14]:

dsODN Tag Integration: Double-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (dsODNs) were introduced into cells expressing the nucleases, where they integrated into nuclease-induced double-strand break sites.

Library Preparation and Sequencing: Genomic DNA was extracted, fragmented, and libraries prepared for next-generation sequencing with primers specific to the integrated dsODN tags.

Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequencing reads were mapped to the reference genome to identify off-target sites containing integrated dsODN tags.

Validation: Potential off-target sites were validated using targeted sequencing or T7 endonuclease I (T7E1) mismatch detection assays.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Gene Editing Studies

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for ZFN and TALEN Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Assembly Systems | Zinc Finger Modular Assembly [10], Golden Gate TALEN Assembly [10] | Construction of custom DNA-binding domains | TALEN assembly is more straightforward than ZFNs [10] |

| Delivery Vectors | Plasmid DNA, mRNA, Viral Vectors (Lentivirus, Adenovirus) [2] | Introduction of nuclease constructs into cells | Protein delivery reduces off-target effects [11] |

| Validation Assays | T7E1 Mismatch Detection [14], GUIDE-seq [13] [14] | Detection of nuclease activity and off-target effects | GUIDE-seq provides genome-wide off-target profiling [14] |

| Cell Culture Resources | G418 (Geneticin) [16], Fetal Fibroblasts [16] | Selection and maintenance of edited cells | Antibiotic selection enriches for successfully edited cells [16] |

| Repair Templates | ssODNs [11], Donor Vectors with Homology Arms [16] | Introduction of specific mutations via HDR | Homology arm length affects knock-in efficiency [16] |

Applications and Therapeutic Implementation

ZFNs and TALENs have enabled diverse applications across basic research, biotechnology, and clinical therapy. In biomedical research, they facilitate the creation of genetically modified cell lines and animal models for studying gene function and disease mechanisms [10] [17]. Therapeutically, ZFNs have advanced to clinical trials for HIV treatment through CCR5 disruption in CD4+ T cells, demonstrating safety and efficacy in reducing HIV DNA copies in patients [14]. Similarly, TALEN-engineered universal chimeric antigen receptor T-cells (UCART19) have induced molecular remission in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients [14].

The choice between ZFNs and TALENs involves careful consideration of project requirements. ZFNs may be preferable for applications where smaller size is advantageous for delivery, while TALENs offer simpler design rules for laboratories with limited protein engineering expertise [10] [15]. Both platforms benefit from obligate heterodimer FokI variants that reduce off-target effects by preventing homodimer formation [11].

While CRISPR-Cas9 has largely superseded ZFNs and TALENs for many applications due to its simpler design, higher efficiency, and easier multiplexing capability [2] [16] [14], the protein-based platforms retain importance in specific contexts. ZFNs have established regulatory approval pathways and demonstrated clinical success, while TALENs offer high precision with potentially lower off-target risks in certain genomic contexts [2] [15]. The development of these technologies represented crucial milestones in genome engineering, providing the conceptual and technical foundations for programmable nuclease platforms and expanding the boundaries of biological research and therapeutic development [10] [11]. Their continued evolution and specialized applications ensure that ZFNs and TALENs remain valuable components of the modern genome editing toolkit, particularly for clinical applications where their long development history and characterized specificity profiles provide distinct advantages.

The landscape of genetic engineering has been fundamentally reshaped by the advent of CRISPR-Cas systems, which represent a significant departure from traditional gene-editing approaches. Unlike earlier protein-based methods, CRISPR technology utilizes an RNA-guided mechanism for precise DNA targeting, offering unprecedented simplicity, efficiency, and versatility. This revolutionary system, derived from a natural bacterial immune defense mechanism, has democratized genome editing by making precise genetic modifications accessible to researchers across diverse fields including therapeutics, agriculture, and basic biological research. As CRISPR technologies continue to evolve at a rapid pace, understanding their comparative advantages, limitations, and appropriate applications becomes essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to harness their full potential.

Understanding Gene Editing Platforms: From Traditional Methods to CRISPR

The evolution of gene editing technologies has progressed through distinct generations, beginning with early methods that required complex protein engineering and culminating in the RNA-guided precision of CRISPR systems. Traditional gene editing platforms including Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) and Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) pioneered targeted genetic modifications but presented significant technical challenges that limited their widespread adoption [2] [18].

ZFNs, developed first among programmable nucleases, utilize engineered zinc finger proteins that typically recognize 3-base pair DNA sequences. These domains are fused to the FokI nuclease domain, which requires dimerization to become active, necessitating the design of two separate ZFNs that bind opposite DNA strands in precise orientation and spacing [2] [18]. This requirement for paired proteins makes ZFN design complex and often unsuccessful. Similarly, TALENs employ transcription activator-like effector (TALE) proteins in which each repeat domain recognizes a single specific nucleotide, also fused to FokI nuclease domains requiring dimerization for activity [2]. While TALENs offer more straightforward design rules than ZFNs, their assembly remains labor-intensive due to the highly repetitive nature of TALE proteins and the substantial molecular cloning required [2] [18].

The fundamental distinction between these traditional methods and CRISPR systems lies in their targeting mechanisms: ZFNs and TALENs rely on protein-DNA interactions for sequence recognition, whereas CRISPR systems utilize RNA-DNA complementarity through a guide RNA molecule that directs Cas nucleases to specific genomic loci [18]. This fundamental difference in targeting mechanism explains much of CRISPR's advantage in design simplicity and versatility, as modifying RNA sequences is substantially easier than engineering custom DNA-binding proteins for each new target [2].

Mechanism of Action: RNA-Guided DNA Targeting

The CRISPR-Cas Molecular Machinery

The CRISPR-Cas system operates through an elegantly simple yet highly effective mechanism centered on RNA-guided DNA recognition. The core components include the Cas nuclease (most commonly Cas9) and a guide RNA (gRNA) molecule that combines the functions of CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) into a single chimeric molecule [18] [19]. This gRNA contains a 20-nucleotide sequence that determines targeting specificity through complementary base pairing with the target DNA [20].

The process initiates when the Cas nuclease-gRNA complex scans DNA for sequences complementary to the gRNA that are adjacent to a short DNA sequence known as the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) [18]. For the most widely used Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where "N" represents any nucleotide [18] [20]. PAM recognition triggers local DNA melting, followed by RNA-DNA hybridization between the gRNA spacer and the target DNA strand. Successful complementarity leads to activation of the Cas nuclease, which generates a double-strand break (DSB) approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM sequence [18] [19].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanism of RNA-guided DNA targeting by CRISPR-Cas systems:

DNA Repair Pathways and Editing Outcomes

Following the creation of a DSB, cellular repair mechanisms are activated that determine the ultimate editing outcome. The primary repair pathways include Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) [2] [18]. NHEJ is an error-prone process that directly ligates broken DNA ends, often resulting in small insertions or deletions (indels) that can disrupt gene function by causing frameshift mutations or premature stop codons [2]. This pathway is predominant in most cell types and is highly efficient for gene knockout applications.

In contrast, HDR utilizes a DNA repair template to enable precise genetic modifications, including specific nucleotide changes, gene insertions, or reporter knock-ins [2] [21]. While HDR offers greater precision, its efficiency is generally lower than NHEJ and is restricted to specific cell cycle phases (S/G2 phases) [21]. The development of base editing and prime editing technologies has addressed some limitations of HDR by enabling precise nucleotide changes without requiring DSBs or donor templates, thereby expanding the toolkit for precise genome editing [22].

Comparative Analysis: CRISPR vs. Traditional Gene Editing Methods

Technical Performance Metrics

Direct comparison of CRISPR systems with traditional gene editing methods reveals distinct advantages and limitations across multiple performance parameters. The following table summarizes key comparative metrics based on current experimental data:

| Performance Parameter | CRISPR-Cas Systems | Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) | Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting Efficiency | 0-81% (High) [18] | 0-12% (Low) [18] | 0-76% (Moderate) [18] |

| Target Specificity | Moderate to high; predictable off-target effects [18] | High; less predictable off-target effects [2] | High; less predictable off-target effects [2] |

| Ease of Design | Simple; only gRNA requires redesign [2] [18] | Difficult; requires protein engineering [2] [18] | Difficult; requires protein engineering [2] [18] |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High; enables simultaneous editing of multiple genes [2] [18] | Limited; challenging to implement [18] | Limited; challenging to implement [18] |

| Development Timeline | Days (gRNA design and synthesis) [2] | Months (extensive protein engineering) [2] | Weeks to months (labor-intensive assembly) [2] |

| Cost Considerations | Low [2] [18] | High [2] [18] | High [2] [18] |

| Primary Applications | Broad range including functional genomics, therapeutics, agriculture, diagnostics [2] [23] [24] | Niche applications requiring high precision; stable cell line generation [2] | Niche applications requiring high precision; small-scale precision edits [2] |

Experimental Validation: Case Studies

The practical differences between editing platforms are exemplified in several experimental case studies. In one comparative analysis targeting the CCR5 gene (a co-receptor for HIV), TALENs demonstrated high specificity with minimal off-target effects, while CRISPR achieved superior editing efficiency and significantly reduced development time [2]. This efficiency advantage makes CRISPR particularly suitable for large-scale functional genomics screens, where thousands of genetic perturbations need to be tested in parallel [2].

For therapeutic applications, CRISPR-based therapies have demonstrated remarkable clinical success. In clinical trials for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (hATTR), CRISPR-Cas9 delivered via lipid nanoparticles achieved approximately 90% reduction in disease-related protein levels, with sustained response maintained over two years in all participants [24]. Similarly, in hereditary angioedema (HAE), CRISPR treatment resulted in an 86% reduction in kallikrein protein levels and significantly reduced inflammatory attacks [24]. These results highlight the therapeutic potential of CRISPR systems, which benefit from simplified design processes and efficient delivery mechanisms.

Advanced CRISPR Technologies and Methodologies

Expanding the CRISPR Toolkit

Beyond standard CRISPR-Cas9 systems, numerous advanced variants have been developed to address specific experimental needs and overcome limitations of first-generation tools. Base editing systems enable direct, irreversible conversion of one DNA base pair to another without requiring DSBs, thereby minimizing indel formation [22]. These systems combine a catalytically impaired Cas nuclease (nickase) with a deaminase enzyme, enabling precise C•G to T•A or A•T to G•C conversions [22].

Prime editing represents a further advancement, capable of installing all possible nucleotide transitions and transversions, as well as small insertions and deletions, without requiring DSBs or donor templates [21]. This technology uses a catalytically impaired Cas9 fused to a reverse transcriptase and a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that both specifies the target site and encodes the desired edit [21].

The discovery and engineering of novel Cas variants continues to expand the targeting range and specificity of CRISPR systems. CRISPR-Cas12a (formerly Cpf1) differs from Cas9 in creating staggered DNA cuts rather than blunt ends, requiring a T-rich PAM sequence, and utilizing a single RNA molecule for processing and targeting [25]. Recent advances in metagenomic mining and machine learning approaches have identified numerous novel Cas12a subtypes with diverse properties, including distinct PAM preferences and editing windows [25].

Experimental Protocols for CRISPR Applications

Protocol 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Gene Knockout

This standard protocol enables efficient gene disruption through NHEJ-mediated repair:

gRNA Design: Select 20-nucleotide target sequences adjacent to 5'-NGG-3' PAM sites using established tools (e.g., CRISPOR, CHOPCHOP) [20]. Prioritize targets with minimal off-target potential based on specificity scores.

Vector Construction: Clone gRNA sequence into appropriate CRISPR plasmid backbone (e.g., pSpCas9(BB)) using Golden Gate assembly or other standardized methods.

Delivery System: Transfert target cells using appropriate method (lipofection, electroporation, or viral delivery) with 1:1 mass ratio of Cas9 and gRNA vectors [2].

Validation: Assess editing efficiency 48-72 hours post-transfection using T7E1 assay, TIDE analysis, or next-generation sequencing. Confirm phenotypic effects through functional assays.

For difficult-to-transfect cells, ribonucleoprotein (RNP) delivery of precomplexed Cas9 protein and gRNA can improve efficiency while reducing off-target effects [23].

Protocol 2: Base Editing for Precise Nucleotide Conversion

This protocol enables precise nucleotide changes without creating double-strand breaks:

Base Editor Selection: Choose appropriate base editor (e.g., BE4-Gam for C•G to T•A conversions; ABE7.10 or ABE8e for A•T to G•C conversions) [22].

gRNA Design: Design gRNAs positioning the target nucleotide within the editing window (typically positions 4-8 for ABE7.10 and BE4) [22]. Use prediction tools (e.g., CRISPRon-ABE, CRISPRon-CBE) to optimize efficiency and minimize bystander edits [22].

Delivery: Transfert base editor plasmid or deliver as RNP complex. For plasmid transfection, use 2:1 mass ratio of base editor to gRNA vector.

Analysis: Evaluate editing efficiency 72-96 hours post-transfection using Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing. Screen for potential off-target effects at predicted sites.

Recent advances in machine learning have significantly improved base editing outcome predictions. Deep learning models trained simultaneously on multiple experimental datasets now enable more accurate prediction of both editing efficiency and specific outcomes, addressing the challenge of data heterogeneity across different experimental conditions [22].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of CRISPR technologies requires specific reagents and tools. The following table outlines essential research reagents and their applications:

| Research Reagent | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | RNA-guided DNA endonuclease creating double-strand breaks | Gene knockout, knock-in, functional screening [2] [18] |

| Base Editors | Fusion proteins enabling precise single nucleotide changes without DSBs | Disease modeling, therapeutic correction of point mutations [22] |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | Synthetic RNA molecule directing Cas nuclease to specific DNA target | All CRISPR applications; determines targeting specificity [2] [20] |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Delivery vehicles for CRISPR components; particularly efficient for liver targeting | Therapeutic applications (e.g., hATTR, HAE) [24] |

| CRISPR Screening Libraries | Pooled collections of gRNAs targeting multiple genes | Genome-wide functional screens, drug target identification [2] |

| Anti-CRISPR Proteins | Naturally occurring inhibitors of Cas nucleases | Control of editing timing, reduction of off-target effects [20] |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The CRISPR technology landscape continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping future applications. The discovery of novel Cas nucleases through metagenomic mining and machine learning approaches is expanding the available toolkit beyond the well-characterized Cas9 and Cas12a [26] [25]. These efforts have identified compact Cas variants such as Cas12f (approximately one-third the size of SpCas9) that enable delivery via size-constrained vectors [23] [25].

The application of artificial intelligence and deep learning represents another significant advancement, improving the prediction of editing outcomes and gRNA efficiency [22] [25]. For example, the development of "dataset-aware" training approaches allows models to effectively learn from multiple heterogeneous datasets while accounting for systematic differences between experimental conditions [22]. These AI-driven tools are becoming increasingly important for optimizing editing precision and reducing off-target effects.

In therapeutic development, personalized CRISPR treatments are emerging as a promising approach for rare genetic disorders. The landmark case of an infant with CPS1 deficiency who received a bespoke in vivo CRISPR therapy developed and delivered in just six months demonstrates the potential for rapid customization of CRISPR therapies for individual patients [24]. Additionally, the ability to administer multiple doses of LNP-delivered CRISPR treatments (as demonstrated in both the CPS1 deficiency and hATTR trials) represents a significant advantage over viral vector delivery, which typically precludes redosing due to immune responses [24].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for developing and implementing CRISPR-based therapeutic interventions:

The CRISPR revolution has fundamentally transformed the landscape of genetic engineering, establishing RNA-guided DNA targeting as the predominant approach for precise genome manipulation. While traditional methods like ZFNs and TALENs continue to have value for specific applications requiring exceptional precision, CRISPR technologies offer superior versatility, efficiency, and accessibility for most research and therapeutic applications. The rapid advancement of base editing, prime editing, and novel Cas variants continues to expand the capabilities of CRISPR systems, addressing initial limitations and opening new possibilities for both basic research and clinical applications. As the field progresses, the integration of machine learning and computational approaches with experimental methods will further enhance the precision and predictability of CRISPR-mediated genome editing, solidifying its role as an indispensable tool in modern biological research and therapeutic development.

The field of genetic engineering has undergone a revolutionary transformation, evolving from the broad, imprecise techniques of recombinant DNA technology to the unparalleled precision of modern programmable nucleases. This journey represents a fundamental shift in our ability to interact with the genetic code, moving from the transfer of large DNA segments between species to the precise rewriting of nucleotides at single-base resolution. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this evolution is not merely an academic exercise but a critical framework for selecting appropriate experimental strategies, navigating regulatory landscapes, and developing novel therapeutic interventions. The comparative analysis between traditional genetically modified organism (GMO) approaches and contemporary gene-editing platforms reveals distinct paradigms in experimental design, risk assessment, and application potential. This guide provides a comprehensive technical comparison of these technologies, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform strategic decision-making in research and therapeutic development.

Historical Trajectory and Technological Paradigms

The history of genetic manipulation is characterized by increasing precision and control over genetic outcomes, marked by several key technological breakthroughs that have fundamentally reshaped experimental possibilities.

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Genetic Engineering

| Time Period | Technology | Key Innovation | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970s-1980s | Recombinant DNA Technology | Gene transfer between species | Production of therapeutic proteins (e.g., insulin) |

| 2000s | Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) | First programmable nucleases | Gene knockout in model organisms |

| 2011 | TALENs | Modular DNA-binding domain | Gene therapy development |

| 2012 | CRISPR-Cas9 | RNA-guided DNA cleavage | High-throughput functional genomics |

Recombinant DNA Technology: The Foundation Era

Recombinant DNA technology, emerging in the 1970s, enabled the transfer of genes between unrelated species, creating transgenic organisms with novel traits. This approach relied on random integration of foreign DNA into host genomes, typically using Agrobacterium-mediated transformation or biolistic methods for plants [1]. A classic example includes Bt crops, where genes from Bacillus thuringiensis were inserted into cotton and corn to confer insect resistance [1]. While revolutionary, this technology faced limitations including random integration sites, unpredictable expression levels, and significant public controversy regarding environmental and health impacts.

The Rise of Programmable Nucleases

The development of engineered nucleases marked a critical transition toward precision genetic manipulation. These technologies enabled targeted double-strand breaks (DSBs) at specific genomic locations, harnessing cellular repair mechanisms to generate desired modifications.

Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs), the first programmable nucleases, combined zinc finger DNA-binding domains with the FokI nuclease domain [27]. Each zinc finger module recognizes a 3-base pair DNA sequence, and multiple fingers are assembled to target longer sequences (typically 18-24 bp) [2]. The requirement for FokI dimerization ensures high specificity, as two ZFN molecules must bind opposite DNA strands to enable cleavage [27].

TALENs (Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases) improved upon ZFNs by utilizing TALE proteins from Xanthomonas bacteria, where each repeat domain recognizes a single nucleotide [2] [27]. This simpler recognition code provided greater design flexibility and targeting range compared to ZFNs, though protein engineering remained labor-intensive [2].

The CRISPR-Cas System represented a paradigm shift from protein-based to RNA-guided targeting. Originally identified as a bacterial adaptive immune system, CRISPR-Cas9 was adapted for genome editing in 2012 [28]. The system utilizes a Cas nuclease (e.g., Cas9) directed by a guide RNA (gRNA) complementary to the target DNA sequence, requiring only the redesign of the gRNA to redirect targeting [1] [28]. This simplicity, versatility, and efficiency led to its rapid adoption across biological research and therapeutic development.

Figure 1: Evolution of genetic engineering technologies showing increasing precision and accessibility.

Comparative Technical Analysis of Editing Platforms

Mechanism of Action and Experimental Workflows

Understanding the distinct molecular mechanisms of each editing platform is essential for appropriate experimental design and interpretation of results.

Recombinant DNA Technology relies on the insertion of foreign DNA fragments into host genomes, typically using vector systems (e.g., plasmids) containing the gene of interest along with regulatory elements and selectable markers. The random nature of integration leads to variable expression and potential disruption of endogenous genes [1].

Programmable Nuclease Platforms share a common mechanism involving the induction of targeted double-strand breaks (DSBs) followed by cellular repair, but differ in their targeting approaches:

ZFNs and TALENs: Both utilize protein-based DNA recognition domains fused to the FokI nuclease domain. The FokI domain must dimerize to become active, requiring two engineered nuclease proteins to bind opposite DNA strands in close proximity and correct orientation [27]. ZFNs recognize nucleotides in triplets via zinc finger modules, while TALENs use repeat-variable diresidues (RVDs) that each recognize a single nucleotide [2] [27].

CRISPR-Cas Systems: Utilize a complex of Cas nuclease with a guide RNA (gRNA) that hybridizes to the target DNA sequence via complementary base pairing. The Cas9 nuclease requires a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence adjacent to the target site for recognition and cleavage [1] [28]. Upon binding, Cas9 introduces a blunt-ended DSB approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM site [29].

Figure 2: Comparative mechanisms of programmable nuclease platforms.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Direct comparison of technical parameters reveals the distinct advantages and limitations of each platform for specific research applications.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Gene Editing Platforms

| Parameter | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR-Cas9 | Traditional Recombinant DNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting Specificity | High | High | Moderate to High | N/A (Random integration) |

| Off-Target Effects | Low | Low | Moderate to High [2] | N/A |

| Editing Efficiency | Moderate | Moderate | High | N/A |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Low | Low | High [2] | Limited |

| Design Complexity | High (Protein engineering) | High (Protein engineering) | Low (gRNA design) | Moderate (Vector construction) |

| Development Timeline | Weeks to months | Weeks to months | Days [2] | Weeks |

| Cost | High | High | Low | Moderate |

The data reveal CRISPR-Cas9's superior efficiency and multiplexing capabilities, while ZFNs and TALENs maintain advantages in specificity with lower off-target effects [2]. Traditional recombinant DNA operates in a fundamentally different paradigm without targeted specificity.

Experimental Design and Methodological Considerations

Protocol for CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing

The following detailed protocol outlines a standard workflow for CRISPR-Cas9 mediated gene editing in mammalian cells, incorporating critical optimization steps for high efficiency and specificity:

Target Selection and gRNA Design: Identify target sequence with 5'-NGG-3' PAM motif. Design gRNA with 20-nucleotide complementarity region. Utilize computational tools (e.g., CRISPR-GPT) to predict on-target efficiency and nominate potential off-target sites [30]. Select multiple gRNAs for comparison.

Vector Construction or RNP Preparation:

- Plasmid-based: Clone gRNA sequence into CRISPR expression vector (e.g., pX330) containing human codon-optimized Cas9 and gRNA scaffold.

- RNP-based: Complex purified Cas9 protein with in vitro transcribed or synthetic gRNA at 3:1 molar ratio (Cas9:gRNA) in nuclease-free buffer, incubate 10 minutes at room temperature for RNP formation [29].

Delivery Optimization:

- For plasmid DNA: Use lipid-based transfection (e.g., Lipofectamine 3000) or viral delivery (lentiviral, adenoviral).

- For RNP: Utilize electroporation (e.g., Neon System) for high efficiency delivery, particularly in primary cells.

- For in vivo applications: Employ lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) optimized for tissue targeting [24].

Editing Validation:

- 48-72 hours post-delivery, harvest cells for genomic DNA extraction.

- Assess editing efficiency using T7 Endonuclease I or TIDE assay for indel quantification.

- For precise edits, include donor DNA template (single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide or double-stranded DNA) with 30-50 nt homology arms.

Off-Target Assessment:

- Perform BreakTag sequencing for unbiased nomination of off-target sites and characterization of nuclease activity [29].

- Utilize targeted amplicon sequencing of predicted off-target loci.

- Employ functional assays relevant to the specific experimental context.

Protocol for ZFNs/TALENs Genome Editing

The protein-based nuclease workflow shares similarities with CRISPR but involves distinct design and validation steps:

Target Site Selection: Identify pairs of binding sites in forward and reverse orientation with 16-20 bp spacing for FokI dimerization. Avoid sites with high DNA methylation or nucleosome occupancy.

Nuclease Assembly:

- For ZFNs: Assemble zinc finger arrays using modular assembly or selection-based methods (e.g., OPEN) to target 9-18 bp per monomer.

- For TALENs: Construct repeat arrays using golden gate cloning with specific RVDs (NI=A, HD=C, NN=G/A, NG=T) for target recognition.

Expression Vector Construction: Clone engineered nuclease sequences into mammalian expression vectors with nuclear localization signals. Co-express both monomers from separate promoters or vectors.

Delivery and Validation: Follow similar delivery and validation approaches as CRISPR-Cas9, with particular attention to balancing expression of both monomers for optimal cleavage efficiency.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Genome Editing Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclease Systems | SpCas9, AsCas12a, OpenCRISPR-1 [8] | DNA cleavage at target sites | PAM requirements, size constraints for delivery |

| Editing Enhancers | Base editors, Prime editors | Enable precise edits without DSBs | Editing window, product purity |

| Delivery Tools | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) [24], AAV vectors, Electroporation systems | Deliver editing components to cells | Packaging capacity, cell toxicity, tropism |

| gRNA Design Tools | CRISPR-GPT [30], BreakInspectoR [29] | Predict efficiency and specificity | Incorporates off-target predictions |

| Validation Assays | BreakTag [29], T7E1, NGS-based methods | Assess on-target editing and off-target effects | Sensitivity, throughput, cost |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Cytokines, Small molecules | Enhance HDR efficiency, support cell viability | Optimization required for cell type |

Regulatory and Safety Considerations

The regulatory landscape for gene-edited products varies significantly based on the technology used and the nature of the genetic modification. Traditional recombinant DNA techniques, which involve introducing foreign DNA, are typically subject to strict GMO regulations worldwide [1]. In contrast, the regulatory status of CRISPR-edited organisms remains complex and varies by jurisdiction:

- United States: The USDA has deregulated certain CRISPR-edited crops, particularly those lacking foreign DNA (transgenes), considering them equivalent to conventionally bred plants in some instances [1].

- European Union: Maintains a more precautionary approach, generally considering all plants modified through gene editing as GMOs, even if transgene-free [1] [27].

- Global Variation: Countries including Argentina, Brazil, and Japan have established differentiated approaches that may classify certain CRISPR edits as non-GM, particularly for SDN1 and SDN2 modifications that involve small changes without introducing foreign DNA [1].

For therapeutic applications, regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA evaluate CRISPR-based therapies through existing drug approval pathways, with particular attention to off-target effects, delivery safety, and long-term consequences [24]. The first FDA-approved CRISPR therapy, Casgevy for sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia, has established important regulatory precedents for future applications [24].

Future Directions and Emerging Technologies

The field of genetic engineering continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging technologies poised to address current limitations and expand application possibilities:

AI-Designed Editors: Large language models trained on CRISPR sequence diversity are now generating novel editors with optimized properties. OpenCRISPR-1, an AI-designed editor, demonstrates comparable activity to SpCas9 while being 400 mutations distant from natural sequences [8]. These approaches enable tailoring of editors for specific properties including size, PAM preferences, and editing efficiency.

Advanced Delivery Platforms: Extracellular vesicle-based delivery systems show promise for tissue-specific targeting while avoiding immune responses associated with viral vectors [31]. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) continue to be optimized for different tissue tropisms and redosing capability [24].

Epigenetic Modulators: Technologies combining TALE and dCas9 platforms achieve durable gene silencing without permanent DNA changes, offering potential therapeutic alternatives for conditions where temporary modulation is desirable [31].

Multiplexed Editing Approaches: Strategies simultaneously targeting multiple genomic loci address limitations of single-target approaches, such as variable therapeutic response in sickle cell disease treatment [31].

The integration of artificial intelligence throughout the experimental workflow—from editor design to gRNA optimization and experimental planning—is dramatically accelerating the pace of discovery and therapeutic development while potentially increasing accessibility to researchers across experience levels [30] [8].

Transforming Research: Methodological Applications in Drug Discovery and Therapy

High-throughput functional genomics has been revolutionized by the advent of CRISPR-based technologies, which enable systematic interrogation of gene function at unprecedented scale and precision. These approaches have largely superseded traditional gene modification methods, including zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), which required intricate protein engineering and offered limited scalability [2]. CRISPR screening technologies now serve as cornerstone methodologies for identifying gene functions, validating drug targets, and understanding complex genetic networks in biomedical research [32] [33].

The fundamental advantage of CRISPR systems lies in their RNA-programmable nature, which allows researchers to rapidly redesign targeting specificity simply by modifying guide RNA (gRNA) sequences, dramatically reducing the time and cost associated with large-scale genetic screens [2]. This programmability has enabled the development of three principal screening modalities: CRISPR knockout (CRISPRko) for complete gene disruption, CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) for transcriptional repression, and CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) for gene upregulation [34]. Each approach offers distinct mechanistic advantages and is optimally suited for specific research applications in functional genomics and drug discovery.

Comparative Analysis of CRISPR Screening Modalities

Molecular Mechanisms and Applications

CRISPR knockout (CRISPRko) utilizes the wild-type Cas9 nuclease to create double-strand breaks in DNA, which are repaired by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), often resulting in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt the coding sequence of the target gene [35] [33]. This approach permanently inactivates genes and is particularly valuable for identifying essential genes and investigating loss-of-function phenotypes. CRISPRko screens have proven highly effective for negative selection screens where the loss of essential genes leads to depletion of corresponding guide RNAs from the cell population [34].

CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) employs a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to repressive domains such as the KRAB (Krüppel-associated box) domain of Kox1 [36] [34]. Unlike CRISPRko, CRISPRi does not cleave DNA but instead sterically hinders transcription initiation or elongation when targeted to transcription start sites, resulting in reversible gene suppression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [36] [34]. This system is particularly advantageous when studying essential genes, as it avoids the potential toxicity associated with double-strand breaks in high-copy number genes and enables tunable, reversible suppression [34].

CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) also uses dCas9 but fused to transcriptional activation domains such as VP64, VP64-p65-Rta (VPR), or SunTag systems [36] [34]. By targeting specific regions upstream of transcription start sites (typically -75 to -150 nucleotides), CRISPRa recruits transcriptional machinery to drive gene expression [34]. This gain-of-function approach allows researchers to identify genes whose overexpression confers selective advantages, such as drug resistance, or to study the functions of lowly expressed genes that might be missed in loss-of-function screens [34].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Features of CRISPRko, CRISPRi, and CRISPRa Screening Approaches

| Feature | CRISPRko | CRISPRi | CRISPRa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Type | Wild-type Cas9 nuclease | dCas9-KRAB fusion | dCas9-activator fusion |

| Mechanism | DNA cleavage → indels → gene disruption | Steric blockade of transcription | Recruitment of transcriptional machinery |

| Permanence | Permanent knockout | Reversible suppression | Reversible activation |

| Optimal Targeting | Early exons | Near transcription start site | -75 to -150 bp upstream of TSS |

| Primary Applications | Essential gene identification, loss-of-function studies | Fine-tuned repression, essential gene studies | Gain-of-function, drug resistance studies |

| Toxicity Concerns | Higher (DNA damage response) | Lower | Lower |

| Example Libraries | Brunello (77,441 sgRNAs) [34] | Dolcetto (3-6 sgRNAs/gene) [34] | Calabrese (6 sgRNAs/gene) [34] |

Performance Comparison with Traditional Methods

When compared to preceding gene perturbation technologies, CRISPR screens demonstrate significant advantages in specificity, scalability, and reproducibility. RNA interference (RNAi), while valuable for gene knockdown, operates at the post-transcriptional level and suffers from substantial off-target effects due to seed sequence matches in 3'UTRs [35]. Multiple studies have confirmed that CRISPR-based screens provide more consistent results with fewer off-target effects than RNAi screens [35]. Furthermore, because CRISPRko permanently disrupts gene function rather than transiently knocking down mRNA, it often produces stronger phenotypic signals and allows for analysis over extended timeframes [35].

The comparative efficiency of CRISPR systems becomes particularly evident in practical screening applications. In benchmark studies, optimized CRISPRko libraries such as Brunello with only 4 sgRNAs per gene have demonstrated superior performance in negative selection screens compared to libraries with more guides per gene, highlighting the impact of improved guide RNA design [34]. Similarly, the compact Dolcetto and Calabrese libraries (with only 3-6 sgRNAs per gene) for CRISPRi and CRISPRa respectively have shown enhanced performance in genome-wide screens, enabling more efficient screening in primary cells and complex model systems [34].

Screening Methodologies: Pooled vs. Arrayed Approaches

Experimental Workflows and Applications

CRISPR screens are implemented in two primary formats: pooled and arrayed screens, each with distinct experimental workflows and applications. Pooled screens involve introducing a complex mixture of lentiviral vectors, each encoding a specific sgRNA, into a single population of cells [35] [37]. After transduction, cells are cultured together under selective pressure or subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) based on a desired phenotype. The relative abundance of each sgRNA before and after selection is determined by next-generation sequencing, revealing genes that confer selective advantages or disadvantages [37].

In contrast, arrayed screens involve distributing individual sgRNAs or gene targets across separate wells of multiwell plates, enabling researchers to directly link specific genetic perturbations to complex phenotypic readouts [35] [37]. This format is compatible with a wider range of assay types, including high-content imaging and multiparametric analysis of cell morphology and function [35] [37].

Table 2: Comparison of Pooled vs. Arrayed Screening Approaches

| Consideration | Pooled Screens | Arrayed Screens |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | High (entire genome in one tube) | Moderate (one gene per well) |

| Phenotype Compatibility | Binary assays (viability, FACS) | Multiparametric assays (imaging, kinetics) |

| Cell Model Requirements | Dividing cells (for sgRNA integration) | Primary cells, neurons, non-dividing cells |

| Data Analysis | Complex (requires NGS and deconvolution) | Straightforward (direct genotype-phenotype link) |

| Equipment Needs | Standard lab equipment | Automated liquid handling, high-content imaging |

| Cost Structure | Lower upfront cost | Higher upfront cost |

| Optimal Use Cases | Primary screens, simple phenotypes | Secondary validation, complex phenotypes |

Implementation Considerations

The choice between pooled and arrayed screening formats depends on multiple factors, including the biological question, available resources, and desired readouts. Pooled screens excel in discovery-phase research where the goal is to identify hits from thousands of candidates using simple binary readouts like cell viability [37]. However, they require the generation of stable cell lines, extensive sequencing, and complex bioinformatic analysis [35] [37].

Arrayed screens, while more resource-intensive initially, provide immediate assignment of phenotypes to specific perturbations without requiring sequencing [37]. This format is particularly valuable for validating hits from primary screens in more physiologically relevant models, such as primary cells or complex co-culture systems [37]. The compatibility of arrayed screens with high-content imaging also enables deep phenotypic profiling, including analysis of subcellular morphology, protein localization, and dynamic processes [35].

Many research programs employ a hybrid approach, using pooled screens for primary discovery followed by arrayed screens for secondary validation and mechanistic follow-up studies [37]. This combined strategy leverages the strengths of both methodologies to maximize the robustness and biological relevance of screening outcomes.

Advanced Applications and Emerging Technologies

Inducible and Bidirectional Systems

Recent advancements in CRISPR screening technologies have focused on enhancing temporal control and enabling more complex genetic interactions. Inducible CRISPR systems, such as the iCRISPRa/i system, fuse CRISPR components with mutated human estrogen receptor (ERT2) domains that respond to 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4OHT) [36]. Upon 4OHT treatment, these systems rapidly translocate from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, enabling precise temporal control of gene perturbation with lower background activity and faster response times compared to earlier inducible systems [36]. This temporal precision is particularly valuable for studying genes involved in dynamic processes like development and cellular differentiation, where constitutive perturbation might cause embryonic lethality or mask transient phenotypes [36].

Bidirectional epigenetic editing systems, such as CRISPRai, represent another significant innovation, enabling simultaneous activation and repression of two distinct genomic loci in the same cell [38]. This approach combines orthogonal dCas9 proteins from different bacterial species (e.g., VPR-dSaCas9 for activation and dSpCas9-KRAB for repression) to enable independent targeting of two genetic elements [38]. When coupled with single-cell RNA sequencing (Perturb-seq), CRISPRai allows researchers to investigate genetic interactions and epistasis at unprecedented resolution, revealing hierarchical relationships in gene regulatory networks [38].

Specialized Screening Applications

The application scope of CRISPR screens has expanded beyond conventional cell line models to encompass more physiologically relevant systems. In vivo CRISPR screens conducted in animal models like zebrafish and mice enable functional genetic analysis in the context of intact tissues and whole-organism physiology [33]. For example, large-scale CRISPR screens in zebrafish have successfully identified genes essential for hair cell regeneration and retinal development, demonstrating the power of this approach for uncovering novel biological mechanisms [33].

CRISPR screens in primary human cells are also becoming more feasible with the development of compact, highly efficient guide RNA libraries that require fewer cells [34]. These advances are particularly valuable for immunology and cancer research, where primary immune cells and patient-derived samples offer more relevant models than established cell lines. Additionally, the integration of single-cell readouts with CRISPR screening (Perturb-seq) enables high-resolution mapping of genetic networks and their effects on transcriptional states [38].

Experimental Design and Protocols

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Screens

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Libraries | Brunello (CRISPRko), Dolcetto (CRISPRi), Calabrese (CRISPRa) [34] | Genome-wide sgRNA collections optimized for specific screening modalities |

| Cas9 Variants | Wild-type SpCas9, dCas9-KRAB, dCas9-VPR [36] [34] | Effector proteins for gene knockout, interference, or activation |

| Delivery Systems | Lentiviral vectors, lipid nanoparticles, electroporation | Introduction of CRISPR components into target cells |

| Cell Models | Immortalized cell lines, primary cells, iPSCs, organoids | Cellular systems for conducting screens |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance, fluorescent proteins | Enrichment for successfully transduced cells |

| Sequencing Tools | Next-generation sequencing platforms | Detection and quantification of sgRNA abundance |

Workflow for a Typical Pooled CRISPRko Screen

The implementation of a genome-wide pooled CRISPRko screen involves multiple critical steps [35] [37]. First, a pooled sgRNA library is constructed or obtained from commercial sources. Libraries such as Brunello contain approximately 77,441 sgRNAs targeting ~19,000 human genes with 4 sgRNAs per gene, along with 1,000 non-targeting control guides [34]. The library is packaged into lentiviral particles at low multiplicity of infection (MOI ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive a single sgRNA [37].

Cells expressing Cas9 are transduced with the viral library and selected with antibiotics to generate a representative mutant pool. This pool is then divided and subjected to experimental conditions (e.g., drug treatment) alongside control conditions. After a sufficient period for phenotypic manifestation (typically 10-14 population doublings), genomic DNA is extracted from both experimental and control populations [37]. The integrated sgRNA sequences are amplified by PCR and quantified by next-generation sequencing. Bioinformatic analysis identifies sgRNAs significantly enriched or depleted in experimental versus control conditions, revealing genes that confer sensitivity or resistance to the treatment [35] [37].

Protocol for CRISPRi/a Screens with Inducible Systems

Inducible CRISPRi/a screens provide temporal control over gene perturbation, which is particularly valuable for studying essential genes or dynamic processes [36]. The protocol begins with generating stable cell lines expressing the inducible CRISPR machinery. For the iCRISPRa/i system, this involves expressing dCas9 fused to ERT2 domains that remain sequestered in the cytoplasm by HSP90 until induction [36]. These cells are then transduced with the sgRNA library (Dolcetto for CRISPRi or Calabrese for CRISPRa) at low multiplicity of infection to ensure single guide integration [34].

After allowing time for stable integration and expansion, gene perturbation is induced by adding 4OHT (for iCRISPRa/i) or doxycycline (for Tet-On systems), which triggers nuclear translocation of the CRISPR machinery [36] [38]. The induced cells are cultured for an appropriate duration to allow gene expression changes and phenotypic manifestation. For bidirectional CRISPRai screens, cells express both activator-fused dSaCas9 and repressor-fused dSpCas9, enabling simultaneous activation and repression of different target genes in the same cell [38].

Phenotypic analysis varies based on the screening format. Pooled screens typically use selection pressures or FACS sorting followed by NGS quantification of sgRNA abundance [37]. For arrayed screens, high-content imaging or other multiparametric assays directly measure phenotypic consequences in each well [35]. Advanced approaches like Perturb-seq combine single-cell RNA sequencing with gRNA detection to provide comprehensive transcriptional profiles for each genetic perturbation [38].

CRISPRko, CRISPRi, and CRISPRa technologies have established themselves as powerful, complementary tools for high-throughput functional genomics. CRISPRko remains the gold standard for complete gene inactivation and essential gene identification, while CRISPRi offers reversible, tunable suppression with reduced toxicity. CRISPRa enables gain-of-function studies that reveal genes whose overexpression drives specific phenotypes. The continuing evolution of these technologies—including inducible systems, bidirectional editing, and advanced readout methods—promises to further enhance their precision, scalability, and biological relevance.

When designing CRISPR screens, researchers should carefully consider their biological questions, available resources, and desired outcomes to select the most appropriate perturbation modality and screening format. As these technologies continue to mature and integrate with other emerging methodologies, they will undoubtedly remain at the forefront of functional genomics, drug discovery, and biomedical research.

Target identification (ID) and validation represent the critical foundational stages in the drug discovery pipeline, where potential therapeutic targets are pinpointed and their causal role in disease is confirmed. For decades, traditional genetic modification methods have served as the primary tools for probing gene function. However, the emergence of CRISPR-based editing systems has revolutionized this landscape by offering unprecedented precision, scalability, and efficiency. The comparative analysis between CRISPR editing and traditional GM approaches is not merely academic; it directly impacts the speed, cost, and success rate of early drug discovery [2] [39].

Traditional methods like Zinc Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) and Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) provided early breakthroughs in targeted genetic modifications but required intricate protein engineering for each new DNA target sequence. This process was often time-consuming, expensive, and limited in its ability to scale for high-throughput functional genomics studies [2] [39]. The development of CRISPR-Cas systems has fundamentally altered this paradigm by introducing a programmable, RNA-guided platform that significantly simplifies the design and implementation of targeted genetic modifications, thereby accelerating the entire process from hit finding to mechanism-of-action (MOA) studies [2] [40].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of these platforms, focusing on their application in target ID and validation workflows. By objectively evaluating performance metrics, experimental protocols, and practical implementation considerations, we aim to equip researchers with the information necessary to select the optimal technological approach for their specific drug discovery challenges.

Traditional Gene Editing Platforms

Traditional gene editing platforms are characterized by their protein-based targeting systems. ZFNs are engineered proteins that combine a zinc finger DNA-binding domain, where each finger recognizes a specific DNA triplet, with the FokI nuclease domain that creates double-strand breaks (DSBs). Similarly, TALENs utilize transcription activator-like effector (TALE) proteins, where each repeat domain recognizes a single DNA base pair, fused to the FokI nuclease [2] [39]. Both systems operate as dimers, requiring two constructs to bind opposite DNA strands for successful nuclease activity. Prior to these programmable nucleases, homologous recombination and RNA interference (RNAi) were widely used for gene targeting and silencing, respectively, though these methods often lacked the precision and efficiency of modern techniques [2].

CRISPR-Cas Systems

CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) systems originated as adaptive immune mechanisms in bacteria and archaea. The most commonly used CRISPR-Cas9 system has been adapted for precise genome editing through a simplified two-component system: a guide RNA (gRNA) that directs the Cas9 nuclease to a specific DNA sequence via complementary base pairing, and the Cas9 nuclease itself that induces a DSB [2] [40]. The cell's subsequent repair of this break—through error-prone Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) or precise Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)—enables specific genetic modifications. Unlike protein-based platforms, CRISPR's programmability resides in its easily synthesized gRNA, fundamentally changing the economics and accessibility of precision gene editing [2].

Fundamental Mechanistic Differences

The core distinction between these platforms lies in their targeting mechanisms: protein-based (ZFNs, TALENs) versus RNA-based (CRISPR) recognition. This fundamental difference drives significant variations in design simplicity, multiplexing capability, and overall efficiency. CRISPR's RNA-guided system allows for rapid retargeting by simply modifying the gRNA sequence, whereas traditional methods require laborious protein re-engineering for each new target [2] [39]. Furthermore, CRISPR systems naturally lend themselves to multiplexed editing, where multiple gRNAs can be employed simultaneously to target several genes or genomic loci in a single experiment, a capability that is considerably more challenging and costly to implement with traditional platforms [2].

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Analysis