Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems (CELSS): Principles, Applications, and Biomedical Research Implications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems (CELSS), self-sustaining bioregenerative systems designed for long-duration space missions.

Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems (CELSS): Principles, Applications, and Biomedical Research Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems (CELSS), self-sustaining bioregenerative systems designed for long-duration space missions. It explores the foundational principles of creating closed-loop environments that recycle air, water, and waste using biological processes. The content details the core components, current methodological implementations in research facilities, and the significant technical and biological challenges in system optimization. A critical comparison with physicochemical life support systems highlights the strategic advantages and current global initiatives. For researchers and drug development professionals, this analysis identifies relevant cross-disciplinary applications, including advanced model systems for microbial ecology and the study of closed-system dynamics relevant to biomedical science.

Understanding CELSS: The Science Behind Self-Sustaining Space Habitats

Controlled (or Closed) Ecological Life-Support Systems (CELSS) are self-supporting life-support systems for space stations and colonies, typically achieved through controlled closed ecological systems [1]. The core thesis of CELSS research is to create regenerative environments that can support and maintain human life indefinitely through biological and agricultural means, moving beyond the "bring everything along" paradigm of short-duration spaceflight [1]. This represents a fundamental shift from merely supplying or recycling resources to creating truly self-sustaining ecosystems that can handle air, water, waste, and food production in tandem. For long-term human presence in space, such as on a generation ship or planetary settlement, this transition from controlled to fully closed systems is not just an optimization but a fundamental requirement for viability [1].

Core CELSS Subsystems and Quantitative Performance Metrics

A CELSS integrates several key biological and technological subsystems to maintain life support. The performance of these systems is measured against critical quantitative thresholds to ensure efficacy and closure.

Table 1: Key Subsystems in a CELSS and Their Functions

| Subsystem | Primary Function | Traditional Non-CELSS Approach | CELSS Approach | Key Quantitative Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air Revitalization | Maintain breathable air (O₂) and remove CO₂ [1] | Stored air tanks & CO₂ scrubbers (requires resupply) [1] | Foliage plants via photosynthesis [1] | Target: 100% O₂ production & CO₂ sequestration [1] |

| Food Production | Provide nutritional requirements for crew [1] | Stored, freeze-dried food [1] | Cultivation of food crops in dedicated areas [1] | Crop yield (kcal/m²/day); Closure percentage [1] |

| Wastewater Treatment | Recycle human waste and wastewater [1] | Waste storage or ejection [1] | Biological processing via aquatic plants & filtration [1] | Water recovery rate (%); Purity standards (ppm contaminants) [1] |

Table 2: Parameter Identification Framework Combining Data Types

| Data Type | Role in Parameter Identification | Mathematical Formulation | Application Example in CELSS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Data | Provides numerical targets for model fitting [2] | ( f{quant}(x) = \sumj (y{j,model}(x) - y{j,data})^2 ) [2] | Precise O₂ level measurements, crop growth rates [2] |

| Qualitative Data | Provides inequality constraints on model outputs [2] | ( f{qual}(x) = \sumi Ci \cdot \max(0, gi(x)) ) [2] | Plant health ("viable" vs "non-viable"), "higher/lower" yield [2] |

| Combined Objective Function | Unifies both data types for single scalar optimization [2] | ( f{tot}(x) = f{quant}(x) + f_{qual}(x) ) [2] | Identifying optimal growth chamber parameters from all available data [2] |

Experimental Protocol: Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Data for System Parameterization

Parameterizing a complex CELSS model often requires integrating sparse quantitative data with abundant qualitative observations. The following protocol, adapted from systems biology, provides a robust methodology.

Objective

To estimate model parameters by combining quantitative time-course data and qualitative, categorical characterizations (e.g., plant health status, growth viability) into a single, constrained optimization problem [2].

Methodology

- Model Definition: Define the dynamical system model (e.g., for plant growth, atmospheric exchange) with a parameter vector x to be estimated [2].

- Data Preparation:

- Quantitative Data: Format numerical measurements (e.g., ( O2 ) levels, biomass) as data points ( y{j, data} ) [2].

- Qualitative Data: Convert each categorical observation into an inequality constraint of the form ( gi(x) < 0 ).

- Example: If a mutant plant strain is observed to be "non-viable," this translates to ( Biomass{model}(x) < Viability_Threshold ) [2].

- Objective Function Construction: Construct a total objective function, ( f{tot}(x) ), to be minimized:

- The quantitative term, ( f{quant}(x) ), is the sum-of-squares difference between model outputs and quantitative data [2].

- The qualitative term, ( f{qual}(x) ), is implemented as a static penalty function. For each violated constraint ( gi(x) < 0 ), a penalty ( Ci \cdot max(0, gi(x)) ) is added, where ( C_i ) is a problem-specific constant [2].

- Optimization: Minimize ( f_{tot}(x) ) using a metaheuristic optimization algorithm such as Differential Evolution or Scatter Search to find the optimal parameter set ( x^* ) [2].

- Uncertainty Quantification: Employ a profile likelihood approach to quantify the confidence intervals of the estimated parameters, demonstrating how the combination of data types reduces parameter uncertainty [2].

Diagram 1: Parameter Identification Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Research into CELSS subsystems relies on a suite of specific reagents, biological materials, and technological tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for CELSS Experimentation

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in CELSS Research |

|---|---|

| Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) | Studied for their immunomodulatory properties and potential in regenerative medicine applications relevant to long-duration spaceflight [3]. |

| Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs) | Genetically reprogrammed adult cells used to create disease models for studying physiological changes in controlled environments [3]. |

| Aquatic Plant Species | Used in wastewater treatment subsystems; their root systems process waste nutrients and facilitate water reclamation [1]. |

| Foliage Plants | Key components for air revitalization; undergo photosynthesis to convert CO₂ to O₂ and remove volatile organic compounds [1]. |

| Hypoimmune hiPSC Lines | Advanced gene-edited cell lines used to enhance precision in studying biological responses and developing regenerative therapies [4]. |

| 3D Cell Culture Scaffolds | Provide structure for bioengineered tissue models and more authentic tissue cultures for life support research [4]. |

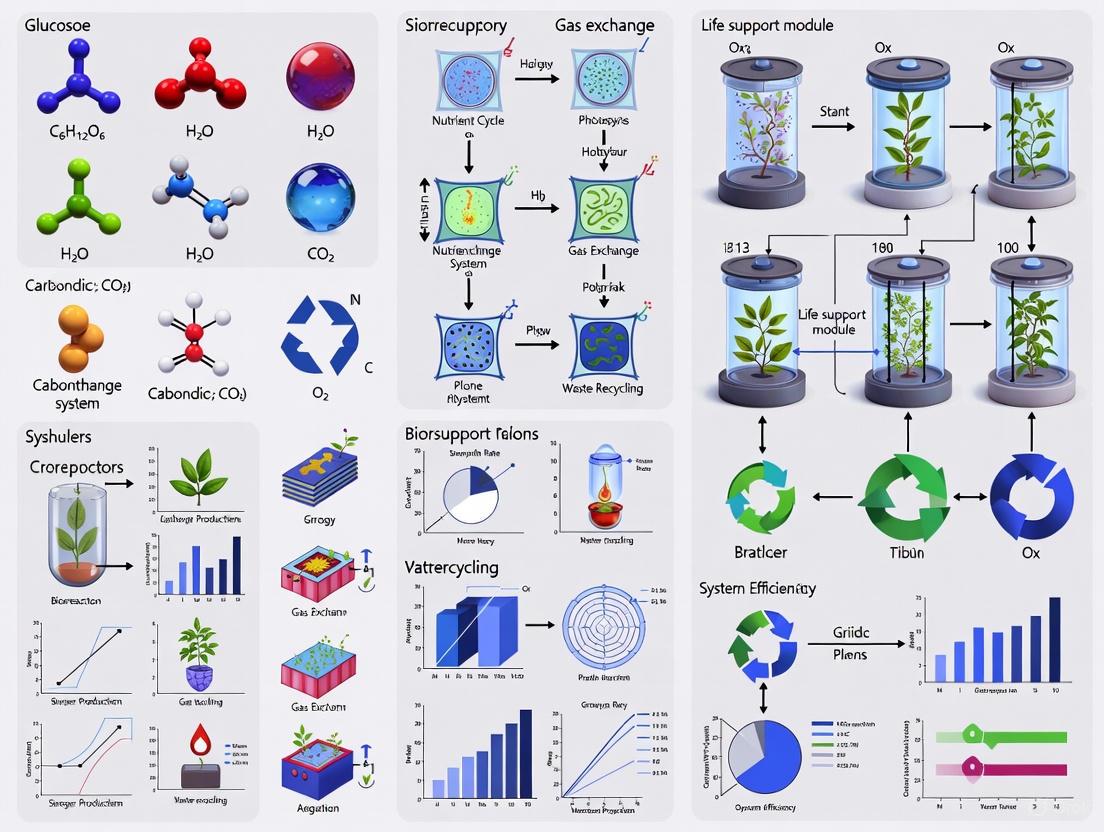

Visualization of a CELSS's Core Interdependent Subsystems

The fundamental principle of a CELSS is the closed-loop interaction of its core subsystems, where the waste output of one process becomes the resource input for another.

Diagram 2: CELSS Closed-Loop Ecosystem

Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems (CELSS) are self-supporting life-support systems for space stations and colonies, designed to create a regenerative environment that can support and maintain human life via agricultural means [1]. The core rationale is that for long-duration space missions or settlements, carrying all necessary consumables from Earth is not viable. Instead, CELSS aims to recycle everything human crew members need—air, water, and food—within a closed, controlled system [1]. These systems are foundational to enabling long-duration human space exploration beyond low-Earth orbit, where resupply from Earth is prohibitively costly or impossible [5].

The current geopolitical and research landscape is dynamic. NASA's historical BIO-Plex program was discontinued after 2004, while the China National Space Administration (CNSA) has since advanced aggressively in this domain, successfully demonstrating a closed-system bioregenerative life support system (BLSS) that sustained a crew of four for a full year [5]. Concurrently, NASA's ongoing research includes developing compact, modular systems for waste treatment and resource recovery, highlighting a renewed focus on closing the life support loop for future lunar and Martian missions [6].

Air Revitalization

In non-CELSS environments, such as the International Space Station, air replenishment and CO₂ processing rely primarily on mechanical and physical-chemical systems like stored air tanks and CO₂ scrubbers, which require periodic replacement or resupply [1]. In a CELSS, the objective is for biological components, primarily foliage plants, to take over the complete production of oxygen and removal of carbon dioxide through the process of photosynthesis [1]. This biological method uses the waste byproduct of human respiration (CO₂) to produce the oxygen required for survival, thereby creating a closed loop for atmospheric gases [1]. Furthermore, plants in these systems have been shown to remove volatile organic compounds (VOCs) off-gassed by synthetic materials used in habitat construction, thereby improving overall air quality [1].

Key Technologies and Methodologies

The European Space Agency's Micro-Ecological Life Support System Alternative (MELiSSA) program is a prominent example of a bioregenerative approach, using compartments containing microorganisms and plants to purify air and recycle waste [7]. Higher plant cultivation modules are integral, as they provide not only food but also a means for air recycling through photosynthesis [7]. NASA's Advanced Plant Habitat (APH) and Vegetable Production System (Veggie) on the ISS are experiments that automate the study of plant growth in microgravity, providing critical data on plant-gas exchange for future system design [7].

Table: Key Air Revitalization Technologies

| Technology/Program | Key Components | Primary Function in Air Revitalization |

|---|---|---|

| Higher Plant Cultivation [7] | Foliage plants (e.g., lettuce, cabbage) | Produces O₂ and consumes CO₂ via photosynthesis. |

| MELiSSA Program [7] | Compartmentalized microorganisms & plants | Purifies air and recycles carbon in a closed loop. |

| Veggie System [7] | Automated growth chambers & plant pillows | Studies plant growth and O₂ production in microgravity. |

| Sorbent-Based Air Revitalization (SBAR) [6] | Composite silica gel & zeolite-packed beds | Physico-chemical system for humidity & CO₂ control. |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Photosynthetic O₂ Production

Objective: To quantify the oxygen production rate of a candidate plant species (e.g., Dunaliella microalgae or Latuca sativa lettuce) within a controlled environment chamber simulating spacecraft conditions.

- Chamber Setup: Place the test organism in a sealed, environmentally controlled growth chamber. Parameters such as light intensity (e.g., 300-500 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ PAR), photoperiod (e.g., 16:8 light:dark), temperature (e.g., 22°C), CO₂ concentration (e.g., 1000 ppm), and nutrient delivery (hydroponic solution) must be precisely maintained and monitored [8] [7].

- Gas Monitoring: Use calibrated in-line gas sensors (e.g., NDIR for CO₂, zirconia or electrochemical for O₂) to continuously log the concentrations of O₂ and CO₂ within the chamber headspace over a 24-hour period.

- Data Acquisition: Record gas concentration data at frequent intervals (e.g., every minute). Simultaneously monitor and record environmental parameters.

- Calculation:

- Net Oxygen Production Rate: Calculate the rate of O₂ accumulation (in mL or mg per hour) during the light period, normalized per unit of plant biomass (e.g., per gram dry weight or per m² leaf area). This provides a key metric for comparing the efficiency of different plant species or growth conditions.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data flow for this experimental protocol:

Food Production

The food production component of a CELSS moves beyond simply storing freeze-dried meals to the in-situ cultivation and harvesting of crops [1]. This module is intrinsically linked with other system functions; the plants not only provide food but also contribute to air revitalization and water recycling [7]. A larger crew requires a larger cultivation area, making space and energy efficiency critical design parameters. Research focuses on higher plant cultivation methods that offer increased productivity, enhanced nutritional value, efficient volume utilization, and shorter production cycles [7].

Key Technologies and Methodologies

NASA's Veggie and Advanced Plant Habitat (APH) are flight-proven systems on the ISS used to grow a variety of leafy greens (e.g., red romaine lettuce, mizuna mustard, Chinese cabbage) and flowers, providing fresh food and valuable data on plant-microbe interactions in microgravity [7]. A significant challenge is the growth medium. While hydroponic systems are used, they are susceptible to microbial contamination (e.g., by Fusarium oxysporum) [7]. An alternative being investigated is In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU) of lunar or Martian regolith (soil) as a growth medium. A key limitation of regolith is the absence of reactive nitrogen. To address this, researchers are inoculating regolith with nitrogen-fixing bacteria (e.g., Sinorhizobium meliloti) to improve soil fertility, a process known as biological ISRU (bISRU) [7]. Furthermore, microalgae (e.g., Chlorella) are being studied as a compact source of food, oxygen, and waste processing due to their high nutritional value (rich in proteins, antioxidants, and polyunsaturated fatty acids) and efficiency [8].

Table: Food Production Systems and Methods

| System/Method | Description | Key Findings/Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Veggie System (ISS) [7] | Hydroponic plant growth facility. | Successfully grew pathogen-free lettuce, cabbage, and kale; safe for human consumption. |

| Regolith bISRU [7] | Using Martian/Lunar soil amended with bacteria. | Clover inoculated with S. meliloti showed improved growth in simulated regolith. |

| Microalgae Reactors [8] | Photobioreactors cultivating algae. | Produces edible biomass rich in proteins and PUFA; also provides O₂ and consumes CO₂. |

| BIOS-3 [7] | Soviet-era underground phytotrons. | Demonstrated feasibility of fully enclosed greenhouse with algae and wheat for air and food. |

Experimental Protocol: Testing Plant Growth in Simulated Regolith

Objective: To evaluate the growth and yield of a candidate crop plant (e.g., Melilotus officinalis - clover) in simulated Martian regolith when inoculated with a nitrogen-fixing bacterium.

- Experimental Groups: Establish three groups: (1) Simulated regolith only (control), (2) Simulated regolith inoculated with a nitrogen-fixing bacterium (e.g., Sinorhizobium meliloti), and (3) a terrestrial potting soil baseline.

- Growth Conditions: Plant seeds in their respective growth media within controlled environment chambers. Maintain consistent light, temperature, and humidity. Water with a nutrient solution lacking nitrogen to force dependence on the nitrogen-fixer in the inoculated group.

- Monitoring and Harvest: Monitor plant germination, growth rate, and visible health over a defined period (e.g., 90 days). At harvest, measure key biometrics: plant height, leaf area, and both wet and dry biomass weight.

- Soil and Tissue Analysis: Analyze post-harvest regolith/soil for reactive nitrogen content (NO₃⁻, NH₄⁺). Conduct elemental analysis of plant tissue to determine nitrogen uptake.

The workflow for this bISRU experiment is as follows:

Waste Recycling

Waste recycling transforms mission-generated waste from a disposal liability into a source of valuable resources. Early spaceflight stored or ejected waste, but CELSS research focuses on breaking down human wastes and integrating the processed products back into the ecology [1]. This includes converting urine into water safe for plant irrigation and processing solid waste into compost [1]. The goal is to achieve near-total recycling of water and nutrients, drastically reducing the mass of consumables that need to be launched from Earth. On a month-long mission, a single crew member is estimated to generate ~1493 kg of urine; recovering 95% of this water could meet 60% of the crew's water demand [8].

Key Technologies and Methodologies

NASA's Modular System for Waste Treatment, Water Recycling, and Resource Recovery is a closed-loop system that processes various wastewater streams (urine, hygiene water, humidity condensate) and organic food waste [6]. Its core is an Anaerobic Membrane Bioreactor (AnMBR), which uses an anaerobic microbial consortium to break down organic matter, while an ultrafiltration membrane removes pathogens [6]. The system produces clean water, methane and hydrogen gas (for fuel), and a nutrient-rich effluent ideal for fertilizing hydroponic systems or photobioreactors cultivating microalgae [6]. The MELiSSA loop also investigates the renewal of water and nutrients from urine, aiming to create a robust closed ecosystem [8]. Emerging concepts include Photosynthetic Microbial Fuel Cells (PMFCs) hybridized with photobioreactors, which use microalgae (e.g., diatoms) to treat waste while simultaneously generating bioelectricity and valuable biomass [8].

Table: Waste Recycling and Resource Recovery Technologies

| Technology | Process Description | Outputs/Products |

|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic Membrane Bioreactor (AnMBR) [6] | Anaerobic digestion coupled with ultrafiltration. | Clean water, methane (CH₄), hydrogen (H₂), fertilizer. |

| Nutrient Recovery [6] | Management of salts and nutrients from AnMBR effluent. | Nutrient stream for hydroponics or algae cultivation. |

| Photosynthetic MFC [8] | Algal cathode microbial fuel cell for waste treatment. | Bioelectricity, treated water, algal biomass for food/feed. |

| Water Dewatering [8] | Extracting 95% of water from human urine. | Potable water (60% of crew need) and nutrient-rich brine. |

Experimental Protocol: Operation of an Anaerobic Membrane Bioreactor (AnMBR)

Objective: To operate a lab-scale AnMBR for the treatment of synthetic wastewater and measure its treatment efficiency and resource recovery outputs.

- System Inoculation and Startup: Inoculate the bioreactor vessel with a consortium of anaerobic microorganisms (e.g., from anaerobic digester sludge). Fill the system with synthetic wastewater designed to mimic the composition of spacecraft wastewater (e.g., containing urea, organic acids, and salts).

- Continuous Operation: Operate the system in continuous mode, feeding wastewater at a controlled flow rate while maintaining strict anaerobic conditions, a constant temperature (e.g., mesophilic, 35°C), and pH.

- Permeate Production and Gas Collection: The integrated ultrafiltration membrane separates treated water (permeate). Biogas produced from the anaerobic digestion (a mixture of CH₄, CO₂, and H₂) is collected in a gas bag or column for volume measurement and composition analysis via gas chromatography.

- Analysis:

- Water Quality: Analyze influent and permeate for key parameters: Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) to measure organic removal, Total Nitrogen (TN), and Ammonia to track nutrient content, and microbial counts to confirm pathogen removal.

- Gas Analysis: Quantify the volume and composition of the produced biogas.

The component relationships and process flow within a waste recycling system are as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents and Materials for CELSS Component Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Simulated Regolith | A terrestrial soil mixture mimicking the chemical and physical properties of Lunar or Martian soil; used as a growth medium in bISRU plant cultivation experiments [7]. |

| Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria (e.g., Sinorhizobium meliloti) | Used as a soil inoculant to convert atmospheric N₂ into reactive nitrogen (ammonia), thereby enhancing the fertility of simulated regolith for plant growth [7]. |

| Hydroponic Nutrient Solution | A precisely formulated, water-soluble mix of essential mineral nutrients (N, P, K, Ca, Mg, S, and micronutrients) required for plant growth in soilless (hydroponic or aeroponic) cultivation systems [7]. |

| Microalgal Cultures (e.g., Chlorella, Dunaliella) | Single-celled photosynthetic organisms cultivated in photobioreactors; function as a model system for studying O₂ production, CO₂ sequestration, wastewater treatment, and food biomass production [8]. |

| Anaerobic Microbial Consortium | A mixed culture of microorganisms from anaerobic digesters; used to inoculate Anaerobic Membrane Bioreactors (AnMBRs) for breaking down complex organic wastes into simpler molecules and gases [6]. |

| Synthetic Wastewater | A laboratory-prepared solution with a defined chemical composition that mimics the properties (e.g., urea, organic carbon, salt content) of real spacecraft wastewater streams; used for standardized testing of treatment systems [6] [8]. |

Long-duration human space exploration beyond Low Earth Orbit (LEO) presents profound logistical challenges that render current life support strategies impractical. Missions to Mars or sustained lunar habitation require a fundamental shift from physical/chemical-based Environmental Control and Life Support Systems (ECLSS) toward bioregenerative life support systems (BLSS) that mimic Earth's ecological processes [9] [10]. The current International Space Station (ISS) ECLSS achieves approximately 85% water recovery and utilizes a combination of adsorption, water electrolysis, and Sabatier reactions for air revitalization, but still vents methane into space and cannot regenerate food [10]. For missions where resupply is impossible, a BLSS that closes the material loops becomes essential for human survival. These systems utilize biological organisms—plants, microbes, and algae—to regenerate air, water, and food from crew waste, thereby dramatically reducing the initial mass and volume of consumables that must be launched from Earth [11] [12].

Historical Context and Strategic Landscape

The concept of Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS), also termed Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems (CELSS), has been explored since the 1960s [11]. NASA pioneered early research through programs like the Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems (CELSS) program and the Bioregenerative Planetary Life Support Systems Test Complex (BIO-PLEX) [9] [5]. However, following the 2004 Exploration Systems Architecture Study (ESAS), NASA discontinued and physically demolished these programs [9]. This discontinuation created a strategic capability gap that other spacefaring nations have since addressed. The China National Space Administration (CNSA) has emerged as a leader in BLSS development, successfully demonstrating a closed-system supporting a crew of four analog taikonauts for a full year in the Beijing Lunar Palace [9] [5]. This facility was derived in part from the discontinued NASA CELSS research [9]. The European Space Agency's more moderate MELiSSA (Micro-Ecological Life Support System Alternative) program focuses on component technology and has not yet progressed to full closed-system human testing [9] [5]. This geopolitical and technological landscape underscores the urgency of reinvestment in BLSS to ensure international competitiveness in future human space exploration [9].

Core Components and Stoichiometric Balance of a BLSS

A functioning BLSS is an artificial ecosystem comprising interconnected compartments, each with specific metabolic functions. The overarching goal is to achieve a high degree of material closure for the elements Carbon (C), Hydrogen (H), Oxygen (O), and Nitrogen (N) [12].

System Architecture and Trophic Levels

A canonical BLSS, such as the ESA's MELiSSA loop, integrates several key compartments [11] [12]:

- Consumers (Crew Compartment): The human crew consumes oxygen, water, and food, producing carbon dioxide, urine, feces, and other waste streams.

- Waste Degraders (Compartments C1-C3): A series of bioreactors (e.g., thermophilic anaerobic, photoheterotrophic, and nitrifying) progressively break down solid and liquid human waste into simpler compounds.

- Producers (Compartments C4a & C4b): Photoautotrophic organisms, such as microalgae (e.g., Limnospira indica) and higher plants, utilize the processed waste (nutrients and CO₂) to produce biomass (food), oxygen, and clean water.

The logical relationships and mass flows between these compartments are visualized in the following system architecture diagram.

Stoichiometric Modeling for System Closure

Achieving system closure requires precise stoichiometric modeling to balance the mass flows of all key elements. The following table summarizes the input and output compounds that must be balanced for a crew of six in a conceptual, fully closed MELiSSA-inspired BLSS, as described in recent research [12].

Table 1: Key Mass Flows in a Stoichiometric Model for a Fully Closed BLSS (Crew of Six)

| Element | Major Input Compounds to Crew | Major Output Compounds from Crew | Closure Status in Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon (C) | Food (Carbohydrates, Lipids, Protein), O₂ | CO₂, Feces, Urine | ~100% Closure [12] |

| Oxygen (O) | O₂, Water (H₂O) | CO₂, H₂O (Respiration, Sweat, Urine) | ~100% Closure (Minor Loss) [12] |

| Hydrogen (H) | Water (H₂O), Food | Water (H₂O), Urine | ~100% Closure [12] |

| Nitrogen (N) | Food (Protein) | Urine (Urea), Feces | ~100% Closure [12] |

This model demonstrates that near-complete closure is theoretically achievable, with 12 out of 14 tracked compounds exhibiting zero loss at steady state, and only oxygen and CO₂ showing minor, manageable losses between iterations [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Research and development of BLSS components rely on a suite of specialized reagents, biological materials, and analytical techniques. The following table details key items essential for experimental work in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for BLSS Experimentation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application in BLSS Research | Example Organisms/Formulations |

|---|---|---|

| Microalgae Strains | Photoautotrophic O₂ production, CO₂ sequestration, water polishing, and potential food source. | Limnospira indica (Spirulina), Chlorella vulgaris [12] [10] |

| Higher Plant Cultivars | Primary food production, air revitalization, and water transpiration. | Staple crops: Wheat, Potato, Soy. Leafy greens: Lettuce, Kale. Dwarf varieties: Tomato, Pepper [11] |

| Nitrifying Bacteria | Biological conversion of ammonia from urine into nitrate, a key plant nutrient. | Mixed cultures from activated sludge; specific strains like Nitrosomonas and Nitrobacter [12] |

| Synthetic Urine/Feces | Standardized, safe medium for testing waste processing bioreactors without human subjects. | Chemically defined solutions mimicking the elemental composition (C, H, O, N) of human waste [12] |

| Hydroponic Nutrient Solutions | Precisely control mineral nutrient delivery to plants in soil-free growth systems. | Hoagland's solution, or modifications thereof, tailored for space environments [11] |

| Internal Standards (IS) | Enable accurate quantitative analysis of metabolites in single-cell or systems biology studies. | Stable isotope-labeled compounds for Mass Spectrometry (MS) normalization and calibration [13] |

Experimental Protocols for BLSS Compartment Testing

Rigorous ground-based testing is a prerequisite for deploying any BLSS technology in space. The following are detailed methodologies for key experimental analyses.

Quantitative Analysis of Metabolites in Single-Cell Organisms

Objective: To accurately measure the concentration of bio-molecules (e.g., metabolites, lipids) in individual microbial or algal cells to understand heterogeneity and optimize BLSS compartment performance [13].

- Sampling: Extract cell contents using a nano-capillary tip or via laser ablation.

- Normalization: Add a known quantity of Internal Standard (IS) to the extraction solvent immediately upon cell lysis. The IS corrects for matrix effects and instrumental variation.

- Ionization: Transfer the sample to a mass spectrometer using a soft ionization technique (e.g., nano-Electrospray Ionization (nano-ESI) or nano-Desorption Electrospray Ionization (nano-DESI)).

- Calibration: Construct a calibration curve by analyzing a series of standard solutions with known concentrations of the target molecule, each containing the same IS.

- Quantification: Compare the normalized signal (analyte signal/IS signal) from the single cell to the calibration curve to determine the absolute amount of the target molecule [13].

The workflow for this protocol, from sample preparation to data analysis, is outlined below.

Stoichiometric Model Development and Balancing

Objective: To create a mathematical framework that describes the flow of elements (C, H, O, N) through all compartments of a BLSS, ensuring mass balance and identifying closure points [12].

- System Scoping: Define all system compartments (C1-C5 in MELiSSA) and the key compounds flowing between them.

- Literature Review: Compile the stoichiometric equations for the metabolic processes in each compartment from existing research (e.g., biomass composition, waste degradation reactions).

- Equation Formulation: Write a compact set of chemical equations with fixed or dynamically calculated stoichiometric coefficients for all processes.

- Spreadsheet Modeling: Implement the equations in a computational model (e.g., a spreadsheet) for a defined crew size. The model simulates the flow of all relevant compounds.

- Iterative Balancing: Adjust the dimensions (scaling) of the different biological compartments until the input and output flows for the majority of compounds are balanced, achieving a high degree of closure at steady state [12].

Despite significant progress, critical challenges remain. Future research must address the impacts of space environments (e.g., reduced gravity, space radiation) on biological processes and system stability [11]. Scaling up from ground-based demonstrators to operational systems requires advancements in automation, control systems, and failure recovery [11] [10]. Furthermore, integrating BLSS with in-situ resource utilization (ISRU)—using Martian CO₂ and regolith, for instance—will be crucial for ultimate sustainability [10].

In conclusion, bioregenerative life support is not merely an enhancement but a fundamental prerequisite for autonomous, long-duration human space exploration. By closing the loops on air, water, and food, BLSS technology enables a future where humanity can sustainably live and work beyond the cradle of Earth. The path forward requires a concerted, international effort in fundamental biological research, systems engineering, and integrated testing to transform these closed ecological systems from a rational concept into a operational reality.

Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems (CELSS), also referred to as Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS), are advanced technological environments designed to sustain human life in space through the biological regeneration of essential resources. These systems utilize biological components, primarily plants and microorganisms, to recycle air, water, and waste and to produce food for crew consumption. The core principle of a CELSS is to create a largely self-sustaining, closed-loop habitat that minimizes the need for external resupply missions, which is a critical capability for long-duration human exploration missions beyond low-Earth orbit, such as to the Moon or Mars [9]. The historical development of these systems is epitomized by two major facilities: the Soviet BIOS-3 and NASA's Bioregenerative Planetary Life Support Systems Test Complex (BIO-PLEX).

This whitepaper traces the trajectory of CELSS research from the Soviet-era BIOS-3 to NASA's BIO-PLEX program. It provides a detailed technical comparison of their architectures and performance, summarizes key experimental protocols, and outlines the essential reagents and methodologies that formed the foundation of this critical field of research. Understanding this historical context is particularly urgent, as past decisions to discontinue programs like BIO-PLEX have led to strategic capabilities gaps, coinciding with other space agencies, notably the China National Space Administration (CNSA), making substantial investments in and demonstrating leadership with their own operational bioregenerative habitats [9].

System Architectures and Historical Trajectories

BIOS-3: The Soviet Pioneer

The BIOS-3 facility, located at the Institute of Biophysics in Krasnoyarsk, Russia, was constructed between 1965 and 1972. This underground steel structure provided a sealed environment of 315 cubic meters, designed to support a crew of up to three persons. The facility was divided into four compartments: one served as the crew area (containing single cabins, a galley, and a control room), while the other three were initially configured as one algal cultivator and two phytotrons (controlled plant growth chambers) [14].

The life support strategy in BIOS-3 relied on a hybrid biological and physicochemical approach. Chlorella algae were cultivated in stacked tanks under intense artificial light from 20 kW xenon lamps to recycle the crew's respiratory carbon dioxide back into oxygen via photosynthesis. It was determined that approximately 8 square meters of exposed Chlorella were required to balance the oxygen and carbon dioxide for one human [14]. Higher-grade air purification, particularly the removal of complex organic compounds, was achieved not biologically, but by heating the air to 600 °C in the presence of a catalyst [14]. While the system successfully recycled water with an 85% efficiency by 1968, it did not recycle solid human waste; urine and feces were typically dried and stored [14]. The facility also depended on an external energy source, consuming 400 kW of electricity supplied by a nearby hydroelectric power station [14].

NASA's BIO-PLEX: The Ambitious Successor

NASA's Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems (CELSS) program, initiated in the latter part of the 20th century, was the foundation for the Bioregenerative Planetary Life Support Systems Test Complex (BIO-PLEX). This program was conceived as an integrated habitat demonstration facility to advance bioregenerative technology for human exploration [9]. The BIO-PLEX represented a significant evolution in scale and integration ambition, designed to push the boundaries of closed-loop life support.

However, the NASA BIO-PLEX program was discontinued and its physical infrastructure was reportedly demolished following the release of the Exploration Systems Architecture Study (ESAS) in 2004 [9]. This decision terminated a major U.S. initiative in bioregenerative life support and created a strategic gap in American capabilities. The research and technological frameworks developed under the CELSS and BIO-PLEX programs subsequently influenced international efforts, most notably contributing to the CNSA's development of the Beijing Lunar Palace, which has since demonstrated advanced closed-system operations [9].

Table 1: Key Architectural and Performance Parameters of BIOS-3 and BIO-PLEX

| Parameter | BIOS-3 (USSR/Russia) | NASA BIO-PLEX |

|---|---|---|

| Operational Period | 1972-1984 (key experiments) | Pre-2004 (Program discontinued post-ESAS) [9] |

| Facility Volume | 315 m³ [14] | Information Limited |

| Crew Capacity | 1-3 persons [14] | Information Limited |

| Primary O₂ Production | Chlorella Algae & Wheat/Vegetables [14] | Planned Higher Plant & Biological Systems [9] |

| Water Recovery Rate | 85% (achieved by 1968) [14] | Information Limited |

| Waste Recycling | Solid waste stored, not recycled [15] | Aimed for higher closure (targets unspecified) [9] |

| External Energy Need | 400 kW (from hydroelectric plant) [14] | Information Limited |

| Longest Crewed Test | 180 days (1972-73) [14] | Information Limited |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The advancement of CELSS technology relied on rigorous, long-duration experiments to validate system stability and crew-plant-microorganism interactions. The following protocols summarize the core methodologies employed in these historic tests.

BIOS-3 Closure Experiment Protocol

The renowned 180-day BIOS-3 experiment serves as a classic model for closed-system testing [14].

- Objective: To demonstrate the feasibility of sustaining a three-person crew for six months within a closed ecosystem, achieving atmospheric balance and a significant portion of food production internally.

- System Preparation and Sealing:

- Compartment Conditioning: The phytotrons and algal cultivator are prepared. Growth trays are filled with nutrient solution and planted with specified crops (e.g., wheat, vegetables) and Chlorella algae strains.

- Atmospheric Baseline: The internal atmosphere is purged and brought to a predetermined composition (e.g., 78% N₂, 21% O₂, 0.04% CO₂).

- Resource Loading: All required water and nutrient stocks are stored within the facility. A supply of dried meat is imported.

- Physical Sealing: The facility is hermetically sealed. All transfer of matter with the external environment is stopped, except for electrical power and information exchange.

- In-Experiment Monitoring and Data Collection:

- Atmospheric Analysis: Continuous or frequent sampling of O₂, CO₂, and trace volatile organic compounds (VOCs). CO₂ levels are managed by adjusting algal or plant growth chamber lighting.

- Plant and Algae Management: Standard hydroponic practices are followed. Plant health, growth rates, and yields are meticulously recorded. Algal culture density is monitored and maintained.

- Crew Health and Diet: Crew physiological parameters are tracked. The diet consists of internally grown vegetables and wheat, supplemented with the pre-loaded dried meat.

- Waste Handling: Human metabolic waste (feces and urine) is collected, dried, and stored within the facility for the duration of the experiment without in-situ recycling [15].

- Post-Experiment Analysis:

- System Mass Balance: A comprehensive audit is performed on all inputs and outputs to calculate closure percentages for oxygen, water, and nutrients.

- Biological Material Analysis: Plant and algal biomass is analyzed for nutritional content and potential accumulation of trace contaminants.

- Crew Health Assessment: A full medical evaluation is conducted to identify any physiological or psychological effects of the prolonged enclosure.

BIO-PLEX and CELSS Plant Growth Experiment Protocol

NASA's CELSS research established rigorous protocols for quantifying plant performance in closed environments, a critical component for BIO-PLEX [9].

- Objective: To select and optimize candidate plant species for high-yield food production, efficient gas exchange, and water recycling in a closed life support system.

- Experimental Setup:

- Environmental Chambers: Plants are grown in controlled environment chambers (Phytotrons) that regulate temperature, humidity, light intensity (using high-intensity electric lamps), photoperiod, and CO₂ concentration.

- Hydroponic System: A nutrient delivery system (e.g., film, aeroponics) is used to provide precise control over root zone conditions and nutrient composition.

- Experimental Repeats: The experiment is conducted with multiple biological repeats (independent replicates from different biological samples) to ensure statistical robustness and account for biological variability [16].

- Data Acquisition and Metrology:

- Gas Exchange Measurements: A closed-chamber method is used. The chamber is sealed for a short period, and the drawdown of CO₂ and release of O₂ are measured using infrared gas analyzers and paramagnetic O₂ sensors, respectively. This quantifies the photosynthetic and respiration rates.

- Biomass and Yield Tracking: The fresh and dry mass of edible and inedible biomass is recorded at harvest. The Harvest Index (ratio of edible mass to total biomass) is calculated.

- Water Transpiration: The mass of water consumed by the plants is measured by tracking the loss from the nutrient reservoir, allowing calculation of water-use efficiency.

- Nutrient Uptake Analysis: Periodic samples of the nutrient solution are analyzed via ion chromatography or ICP-MS to track the uptake of essential minerals (e.g., N, P, K, Ca).

- Data Analysis Workflow:

- Data Exploration: Researchers perform exploratory data analysis using programming languages like Python or R to visualize trends, identify outliers, and refine hypotheses. This involves creating plots of growth rates, gas exchange, and yield as a function of environmental conditions [16].

- Quantitative Phenotyping: Quantitative metrics for plant phenotype are developed, including growth rates, leaf area, and morphological characteristics, to provide definitive, repeatable metrics for comparison [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The research and development of CELSS depends on a suite of biological and technological components. The table below details the essential "research reagents" that formed the cornerstone of historical experiments in BIOS-3 and BIO-PLEX.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for CELSS Experimentation

| Reagent/Material | Function in CELSS Research | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chlorella Algae | Primary producer for O₂ generation and CO₂ absorption. Fast-growing and highly efficient at gas exchange. | Used in BIOS-3; requires ~8 m² per person for air balance [14]. |

| Cereal Crops | Source of carbohydrates and plant-based protein for crew diet. Also contributes to gas exchange. | Dwarf wheat was a major focus in CELSS/BIO-PLEX research [9]. |

| Vegetable Crops | Provides essential vitamins, minerals, and dietary variety for crew nutrition and psychological well-being. | Grown in BIOS-3 phytotrons; choices often include lettuce, tomato, potato [14] [15]. |

| Hydroponic Nutrients | Supplies essential mineral elements for plant growth in soilless (hydroponic or aeroponic) systems. | Precise control of macro-nutrients (N, P, K) and micro-nutrients (Fe, Mn, Zn) is critical [9]. |

| Catalytic Oxidizer | Physicochemical unit for removing trace volatile organic compounds and purifying the cabin air. | BIOS-3 used a high-temperature (600°C) catalytic oxidizer as a backup to biological systems [14]. |

| Quantitative Imaging Software | Tool for analyzing plant health, growth, and morphological characteristics from image data. | Used to generate quantitative metrics of plant phenotype (e.g., leaf area, growth rates) [17]. |

| Data Analysis Platforms (R/Python) | Programming environments for statistical analysis, data exploration, and visualization of experimental results. | Essential for handling complex datasets on gas exchange, biomass yield, and nutrient flows [16]. |

System Logic and Functional Relationships

The core of a CELSS is the interdependent relationship between the crew and the biological systems. The following diagram maps the logical flow of mass and energy within a generalized bioregenerative life support system, synthesizing the approaches of both BIOS-3 and BIO-PLEX.

The historical journey from Soviet BIOS-3 to NASA's BIO-PLEX represents a critical epoch in the development of controlled ecological life support systems. BIOS-3 demonstrated the fundamental feasibility of sustained human life within a closed bioregenerative system, achieving notable milestones in water recycling and atmospheric management, albeit with clear limitations in waste recycling and energy independence [14] [15]. NASA's BIO-PLEX program sought to build upon this foundation, aiming for a more integrated and advanced habitat. However, its discontinuation in the mid-2000s created a significant strategic gap in U.S. capabilities for endurance-class human space exploration [9].

The quantitative data, experimental protocols, and research tools detailed in this whitepaper provide a technical foundation for understanding the achievements and challenges of this field. The legacy of these programs is not merely historical; it directly informs ongoing international efforts. As human space exploration aims for the Moon and Mars, re-investing in and advancing CELSS technology is not just a scientific pursuit, but a strategic imperative to ensure long-term leadership and operational sustainability in deep space [9].

Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems (CELSS) are self-supporting systems designed to sustain human life in space by creating a regenerative environment through biological and ecological means [1]. The core rationale is to move beyond merely carrying all consumables, which is feasible only for short missions, to establishing systems that can regenerate air, water, and food over long-duration missions or extraterrestrial settlements [1]. The aim is a regenerative environment that supports and maintains human life via agricultural processes, fundamentally relying on two key biological processes: photosynthesis for air revitalization and food production, and microbial bioreactors for waste processing and valuable product synthesis [1].

The strategic importance of these systems has been highlighted by recent geopolitical developments. Following the discontinuation of NASA's Bioregenerative Planetary Life Support Systems Test Complex (BIO-PLEX), the China National Space Administration (CNSA) has advanced this technology, successfully demonstrating a closed-system life support system sustaining a crew of four for a full year [5]. This underscores the urgency for the US and its allies to reinvest in bioregenerative life support systems (BLSS) to maintain international competitiveness in human space exploration [5].

Photosynthesis: From Natural Principles to Engineered Systems

Natural Photosynthesis and Its Application in CELSS

In a CELSS, natural photosynthesis is primarily harnessed through foliage plants. These plants perform the dual function of air revitalization—consuming carbon dioxide from human respiration and producing oxygen—and providing food for the crew [1]. This process directly addresses the logistical constraints of long-duration spaceflight by reducing the need for stored air tanks and CO2 scrubbers, which deplete over time [1]. Furthermore, plants have been found to remove volatile organic compounds off-gassed by synthetic materials used in habitat construction, thereby contributing to air quality maintenance [1].

Engineered and New-to-Nature Photosynthesis (NPS)

Recent breakthroughs in synthetic biology have enabled the creation of new-to-nature photosynthesis (NPS) systems, reconstructing photosynthetic capabilities in non-photosynthetic organisms. A landmark 2025 study successfully engineered a synthetic photosynthesis system in Escherichia coli [18].

The system comprised:

- A Light Reaction: A biogenic photosystem (NPM) was constructed by assembling backbone proteins (NuoK + PufL) in the inner membrane and incorporating magnesium protoporphyrin IX (MgP) molecules. Upon illumination, this system generated photoelectrons using methanol as an electron donor, resulting in a 337.9% increase in ATP and a 383.7% increase in NADH content [18].

- A Dark Reaction: A synthetic CO2 fixation pathway was constructed to convert CO2 into pyruvate [18].

- An Energy Adapter: This component dynamically matched the energy generation from the light reaction with the biosynthetic demands of the dark reaction [18].

This engineered system enabled E. coli to utilize one-carbon substrates for the production of acetone, malate, and α-ketoglutarate with a negative carbon footprint of -0.84 to -0.23 kgCO2e/kg product, and supported light-driven trophic growth with a doubling time of 19.86 hours [18].

Diagram 1: Engineered Photosynthesis System in E. coli.

Microbial Bioreactors: Technology and Protocols

Principles of Microbial Bioreactors in CELSS

Microbial bioreactors in CELSS serve multiple functions, from wastewater treatment to the production of valuable chemicals and biofuels. They often leverage microalgal-bacterial consortia, where photosynthesis by microalgae provides oxygen for bacterial activity, while bacteria provide CO2 for algal growth, creating a synergistic relationship [19]. Furthermore, photosynthetic microbial fuel cells (PMFCs) represent an advanced bioreactor technology that combines wastewater treatment with bioelectricity generation. In a PMFC, photosynthetic microorganisms at the cathode, such as microalgae, utilize CO2 and produce oxygen and valuable products, while bacteria at the anode oxidize organic matter to generate electricity [20].

Bioreactor Types and Scaling for CELSS Applications

The choice of bioreactor is critical for the efficiency and scalability of processes in a CELSS. Different designs are employed based on the organism and the target product.

Table 1: Bioreactor Types for Microbial and Plant Cell Cultures in CELSS Research

| Bioreactor Type | Key Features | Applications in CELSS | Scalability | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stirred-Tank (CSTR) | Mechanical agitation for uniform mixing and gas exchange [21]. | Suspension cultures of microbes and plant cells; production of recombinant proteins [21]. | High (Lab to Industrial) [21]. | Shear stress can damage sensitive plant cells [21]. |

| Airlift | Agitation via gas sparging; low shear stress [21]. | Cultivation of shear-sensitive organisms like microalgae and plant cells [21]. | High (Pilot to Industrial) [21]. | Mixing can be less uniform than in CSTR [21]. |

| Photobioreactor (PBR) | Includes a light source to support photosynthetic organisms [21]. | Cultivation of microalgae and cyanobacteria for O₂ production, CO₂ sequestration, and biofuel synthesis [19] [22]. | Moderate (Lab to Pilot) [21]. | Light penetration and distribution can be a limiting factor [21]. |

| Single-Use Bioreactor (SUB) | Pre-sterilized, disposable bags; reduce cross-contamination [21]. | Ideal for GMP-compliant production of pharmaceuticals and high-value metabolites [21]. | Bench-top to 2000L Commercial [21]. | Reduced cleaning and validation time; plastic waste generation [21]. |

Experimental Protocol: Flow Cytometry for Monitoring Consortia

Monitoring the composition of microalgal-bacterial consortia is essential for system stability. Flow cytometry (FCM) provides a powerful method for this.

Objective: To quantify the absolute abundance of microalgae and bacteria in a consortium from a photobioreactor treating real wastewater [19]. Principle: FCM distinguishes cells based on light scattering and fluorescence. Microalgae are identified via red autofluorescence from chlorophyll, while bacteria are stained with a green fluorescent dye like SYBR Green I [19].

Methodology:

- Sample Dilution: Dilute the sample to a concentration suitable for FCM analysis [19].

- Biomass Disaggregation: Subject the sample to optimized ultrasonication (e.g., 5 min at 20 kHz) to disaggregate flocs into single cells without causing significant cell damage [19].

- Filtration: Filter the sonicated sample through a 20 μm mesh to remove large debris while allowing microbial cells to pass through [19].

- Staining: Stain the sample with SYBR Green I to fluorescently label bacterial DNA [19].

- FCM Analysis: Analyze the sample using a flow cytometer. Trigger on green fluorescence (e.g., 530 nm) to count bacteria and on red autofluorescence (e.g., >670 nm) to count photosynthetic cells [19].

Diagram 2: Flow Cytometry Workflow for Consortium Analysis.

Synthesis and Integration in CELSS

The integration of photosynthesis and bioreactor technologies forms the foundation of a functional CELSS. The ultimate goal is to create a synergistic loop where human waste streams are processed by microbial systems, which in turn support plant growth, which then provides oxygen and food for the crew.

Table 2: CELSS Subsystem Integration and Outputs

| CELSS Subsystem | Primary Inputs | Biological Process / Technology | Primary Outputs / Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air Revitalization | CO₂ (from crew), Light, Water [1] | Photosynthesis (Foliage Plants) [1] | O₂ (for crew), Food, VOCs removal [1] |

| Wastewater Treatment & Recycling | Wastewater (from crew), CO₂ [20] [19] | Microbial Bioreactors; Microalgal-Bacterial Consortia [20] [19] | Clean Water, Biomass, Nutrient Recovery [1] |

| Bioelectricity & Chemical Production | Waste Organics, Light, CO₂ [20] [18] | Photosynthetic Microbial Fuel Cells (PMFCs); Engineered NPS [20] [18] | Electricity (for systems), Valuable Chemicals (e.g., Acetone), Biofuels [20] [18] |

Diagram 3: Integration of Biological Processes in a CELSS Loop.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for CELSS Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| SYBR Green I | A fluorescent nucleic acid stain used to label and quantify bacterial cells in a mixture via flow cytometry [19]. | Differentiating and counting bacteria in a microalgal-bacterial consortium from a wastewater-treating PBR [19]. |

| Magnesium Protoporphyrin IX (MgP) | An analog of bacteriochlorophyll; acts as a photosensitizer to absorb light and generate photoelectrons in engineered systems [18]. | Reconstructing a light reaction in the biogenic photosystem of engineered E. coli for NPS [18]. |

| FM4-64 | A red-fluorescent lipophilic dye that stains cell membranes. Used for visualizing and confirming membrane localization of proteins [18]. | Verifying the assembly of the anchor protein NuoK-EGFP fusion on the inner membrane of E. coli [18]. |

| Oligonucleotide Probes / BioBricks | Standardized, well-characterized genetic parts (promoters, genes, etc.) for the rational design of artificial genetic circuits [22]. | Using synthetic biology to engineer cyanobacteria or other hosts for optimized production of solar fuels (H₂) or chemicals [22]. |

| Sonication Device | Uses ultrasonic energy to disaggregate biological flocs and granules into single-cell suspensions for accurate analysis [19]. | Pre-treatment of microalgal-bacterial samples before flow cytometry to break up flocs without damaging cells [19]. |

Implementing CELSS: System Design, Current Projects, and Research Applications

Within the framework of Controlled Ecological Life Support System (CELSS) research, the engineering of closed ecosystems is paramount for sustaining human life during long-duration space exploration. A CELSS aims to create a self-sustaining environment by regenerating air, water, and food through biological processes, thereby reducing reliance on resupply missions from Earth. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) historically established the CELSS program and the Bioregenerative Planetary Life Support Systems Test Complex (BIO-PLEX) to advance this technology [9]. However, following the Exploration Systems Architecture Study in 2004, these programs were discontinued in the US, leading to critical strategic gaps [9]. In the interim, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) has embraced and advanced this domain, successfully demonstrating closed-system operations that sustain a crew of four analog taikonauts for a full year in their Beijing Lunar Palace facility [9]. Growth chambers serve as the foundational technology within a CELSS for the controlled cultivation of plants, which are responsible for air revitalization, water purification, and food production. These chambers provide the precise environmental control necessary to study and optimize plant growth for logistically biosustainable exploration, a concept dating back to initiatives like Project Horizon in 1959 [9]. This guide details the core engineering principles and controls of these chambers, contextualized for researchers and scientists developing closed ecological systems.

Core Engineering Principles of Plant Growth Chambers

A plant growth chamber is an environmentally controlled enclosure designed to simulate and manipulate conditions for plant growth and scientific experiments [23]. In CELSS research, they are invaluable for determining the effects of specific environmental parameters on plants in a closed, controllable system, unlike field experiments which are affected by numerous simultaneous factors [24]. Their core function is to provide reliable and repeatable conditions for investigating plant physiology and optimizing growth for life support consumables.

Essential Environmental Control Subsystems

The controlled environment is maintained by several integrated subsystems:

- Temperature Control Systems: These advanced systems maintain stable temperature levels throughout the chamber, providing ideal growth conditions irrespective of external fluctuations [23].

- Humidity Regulation: Control systems adjust moisture levels within the chamber to prevent plant dehydration and encourage healthy growth [23].

- Lighting Systems: Customizable systems using fluorescent, LED, or high-intensity discharge (HID) lamps provide the necessary spectrum and intensity for photosynthesis across different plant species and growth stages [23]. Advanced ray-tracing models can simulate light quantity and quality (phylloclimate) at the organ scale to optimize this critical parameter [25].

- CO₂ Enrichment: As CO₂ is essential for photosynthesis, growth chambers often include systems to enrich atmospheric levels within the chamber, thereby accelerating plant growth rates [23].

- Air Circulation and Ventilation: Fans and ventilation systems ensure uniform environmental conditions, prevent heat or humidity build-up, and facilitate adequate gas exchange [23].

Quantifying the "Chamber Effect" and Ensuring Experimental Fidelity

A critical consideration in CELSS research is the "chamber effect"—where results are biased not by experimental treatment but by inconspicuous differences in supposedly identical chambers [24]. This effect can be categorized as:

- Resolvable Chamber Effects: Caused by malfunctioning components, such as a closed air damper leading to excessive injection of CO₂ from gas cylinders, which can be identified and repaired [24].

- Unresolved Chamber Effects: Caused by unknown factors that can only be mitigated through appropriate experimental design and sufficient replication [24].

Research has identified the most effective plant traits for detecting a chamber effect. For instance, using Vicia faba L. 'Aquadulce Claudia' (broad bean), fresh weight and flower count were the most efficient and effective traits for initial detection, while stable carbon isotopes (δ13C) and gas exchange analysis helped distinguish between resolvable and unresolved effects [24]. This underscores the necessity of chamber validation prior to critical experimentation.

Global Market and Technological Landscape

The development of growth chamber technology is supported by a robust and growing global market. Understanding this landscape is vital for CELSS researchers procuring equipment and leveraging technological advancements.

Table 1: Global Plant Growth Chamber Market Size and Forecast

| Region | Market Size in 2024 (USD Million) | Projected Market Size in 2033 (USD Million) | CAGR (2025-2033) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global | 439.3 - 574.1 [26] [27] | 761.7 - 969.4 [26] [27] | 5.90% - 6.0% [26] [27] |

| North America | 219.34 [28] | 307.2 [28] | 4.3% [28] |

| Europe | 171.91 [28] | 250.1 [28] | 4.8% [28] |

| Asia Pacific | 142.27 [28] | 273.2 [28] | 8.5% [28] |

Table 2: Market Segmentation Analysis (2024)

| Segment | Leading Sub-category | Market Share (%) | Key Driving Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equipment Type | Reach-in [27] | ~76% [27] | Space efficiency, suitability for smaller research spaces, and versatility for multiple simultaneous experiments [27]. |

| Application | Short to Medium Height Plants [27] | ~69% [27] | Relevance to key research on crop yield, pest resistance, and nutrient absorption [27]. |

| Function | Plant Growth [27] | ~42% [27] | Drive to accelerate agricultural advancements and develop high-yielding, resilient crops [27]. |

| End Use | Clinical Research [27] | ~74% [27] | Growing need in pharmaceuticals and biotechnology for controlled environments to study plant-derived compounds [27]. |

Key market trends include significant investments in research and development and a growing emphasis on customization and modular designs [27]. Tailored solutions allow chambers to be configured for specific plant species or experimental protocols, enhancing productivity and accuracy. Modular designs provide scalability for expanding research projects, while specialized features like adjustable shelving and integrated sensors maximize efficiency and control [27].

Advanced Experimental Protocols for CELSS Research

Protocol: Validating Growth Chamber Uniformity and Detecting Chamber Effects

This protocol is based on a study that successfully identified chamber effects in four out of eight walk-in chambers [24].

1. Objective: To establish the presence of a "chamber effect" and determine if measured plant traits are biased by inconspicuous differences between identical growth chambers.

2. Experimental Design:

- Plant Material: Select a environmentally sensitive plant species. Vicia faba L. (broad bean) is recommended for its documented sensitivity to environmental stimuli like light and CO₂ [24].

- Growing Conditions: Grow all plants from seed in an identical growing medium and pot size. Select uniform seedlings and randomize their placement across the chambers under test [24].

- Chamber Parameters: Set all chambers to identical setpoints for light, temperature, humidity, and atmospheric CO₂ concentration. Monitor these parameters continuously throughout the experiment.

3. Data Collection and Measurement Traits: After a predetermined growth period, measure the following traits on all plants. The most efficient traits to measure are listed first.

- Fresh Weight: Harvest and immediately weigh above-ground biomass [24].

- Flower Count: Count the number of individual flowers on all inflorescences [24].

- Stable Carbon Isotopes (δ13C): Analyze the stable carbon isotope composition of leaf tissue. This is particularly effective for identifying resolvable chamber effects related to CO₂ source and concentration [24].

- Gas Exchange Analysis: Measure the net rate of CO₂ assimilation (An) and stomatal conductance (gs) using an infrared gas analyzer [24].

- Chlorophyll Fluorescence: Measure the total performance index (PI) to assess photosystem II efficiency [24].

4. Data Analysis:

- Employ a means comparison test (e.g., ANOVA) to look for statistically significant differences in the measured traits between chambers operated under identical setpoints.

- The presence of significant differences for any trait indicates a chamber effect.

- If a δ13C anomaly is detected, investigate the chamber's CO₂ delivery system for malfunctions (a resolvable effect). If no technical fault is found, the effect is unresolved and must be mitigated through experimental design [24].

Protocol: Optimizing Strain Uniformity in Mechanobiological Culture Chambers

For CELSS research involving cell cultures—such as for in vitro food production or biomedical applications—uniform mechanical stimulation is critical. This protocol outlines the optimization of a culture chamber's basement membrane to achieve a uniform strain field.

1. Objective: To design and fabricate a culture chamber with a basement membrane that exhibits a high strain uniformity factor when subjected to mechanical loading.

2. Chamber Optimization and Fabrication:

- Material Characterization: Conduct a uniaxial tensile test on the silicone rubber material to be used (e.g., medical-grade A and B silicone) to derive its stress-strain curve and define material parameters for finite-element analysis (FEA) [29].

- Finite-Element Analysis (FEA):

- Model the culture chamber with a rectangular basement membrane in FEA software (e.g., ABAQUS).

- Use a shape optimization function with the objective of maximizing strain uniformity. The design variable is the basement membrane thickness (Tn) [29].

- Apply a tensile strain (e.g., 1% to 10%) to the model and iterate until an optimized "M" profile basement membrane structure is achieved [29].

- Strain Uniformity Factor Calculation: Introduce the strain uniformity factor, γ(x%), calculated as γ(x%) = s(x%) / S, where S is the total membrane area and s(x%) is the effective area where strain is within ±x% of the strain at the center point [29].

- Chamber Fabrication: Cast the optimized chamber using a vacuum process to ensure material consistency and eliminate defects [29].

3. Validation using 3D Digital Image Correlation (3D-DIC):

- Use a self-designed mechanical loading device to apply a precise tensile strain to the optimized chamber [29].

- Employ 3D-DIC technology to measure the actual strain field across the membrane surface and verify that the optimized chamber achieves a higher strain uniformity factor (e.g., 90% uniform area) compared to a traditional design (e.g., ~70%) [29].

Visualization of Methodologies

Chamber Validation Workflow

Chamber Optimization Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for CELSS-Focused Growth Chamber Experiments

| Item | Function / Role | Technical Notes & CELSS Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Vicia faba L. (Broad bean) | A model plant for detecting "chamber effects" due to its high sensitivity to environmental stimuli (light, CO₂, drought) [24]. | Enables calibration and validation of chamber performance, a critical first step for reliable CELSS plant research [24]. |

| Stable Carbon Isotope (δ13C) Analysis | Tracks the source and concentration of atmospheric CO₂ by analyzing the 13C:12C ratio fixed in plant leaf tissues [24]. | Identifies resolvable chamber effects from CO₂ system malfunctions; can be used to verify the closed-loop air revitalization in a CELSS [24]. |

| Medical-Grade Silicone | A hyper-elastic material used to fabricate the basement membrane for cell culture chambers in mechanobiological studies [29]. | Used in the development of bioreactors for cell culture-based food production or tissue engineering within a CELSS [29]. |

| Three-Dimensional Digital Image Correlation (3D-DIC) | A non-contact optical technique to measure full-field strain and deformation on a material's surface [29]. | Validates the uniformity of mechanical stress applied to cells or engineered tissues in culture chambers, ensuring experimental accuracy [29]. |

| Ray-Tracing Simulation Software | Accurately simulates light quantity (photon flux) and quality (spectrum) intercepted by plant organs in a 3D space [25]. | Critical for optimizing light distribution within a CELSS growth chamber to maximize canopy photosynthesis and energy use efficiency [25]. |

| Controlled Environment Chamber | Provides a fully enclosed space with precise control over temperature, humidity, light, and atmospheric composition [23]. | The fundamental hardware for all CELSS-related plant growth research, allowing for the study of plant responses in a closed, controlled environment [23]. |

Growth chambers with precisely engineered environmental controls are the bedrock of advanced CELSS research, enabling the study and optimization of biological processes for closed ecosystems. As global market trends and technological advancements push toward greater customization, precision, and integration with simulation tools, the capabilities of these systems will continue to evolve. For scientists and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of both the engineering principles outlined here—from core subsystems to advanced validation and optimization protocols—is essential. Mastering this technology is a critical step toward achieving the logistically biosustainable human exploration of deep space, as envisioned by early programs like BIO-Plex and now being demonstrated by international partners [9]. The path to robust, long-duration life support lies in the continued refinement of these controlled environment systems.

Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems (CELSS), also termed Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS), are engineered ecosystems designed to sustain human life in isolated environments by biologically regenerating essential resources. These systems use photosynthetic organisms (plants, algae) to regenerate oxygen, fix carbon dioxide, and produce food, while employing physical-chemical and biological processes to recycle water and waste. The core principle is to create a materially closed, self-sustaining loop that minimizes the need for external resupply, which is critical for long-duration space exploration missions and understanding Earth's biosphere [5] [30].

Research in CELSS provides a unique scientific tool; by establishing total material closure, researchers can track element cycles and system state variables with a completeness impossible in open systems [30]. This paper examines three landmark projects—BIOS-3, Biosphere 2, and Beijing Lunar Palace—that have significantly advanced the field through their distinct designs, experimental paradigms, and technological contributions.

The development of CELSS has been driven by national and international efforts, each contributing unique insights and technological milestones.

BIOS-3 (Russia)

BIOS-3, located at the Institute of Biophysics in Krasnoyarsk, Russia, was one of the first dedicated CELSS research facilities. Its construction began in 1965 and was completed in 1972. This underground steel facility provided a sealed habitat of 315 cubic meters, designed to support a crew of up to three people [14] [31]. The Soviet program laid the foundational groundwork for closed ecosystem research, demonstrating the feasibility of using biological components for life support over extended periods.

Biosphere 2 (United States)

Biosphere 2, located in Oracle, Arizona, was a monumental project in the early 1990s designed to explore the complex interactions within a vastly larger, multi-biome closed ecological system. With an airtight footprint of 1.27 hectares and an enclosed volume of approximately 180,000 cubic meters, it was the largest closed ecological system ever created [32]. Its initial mission, which enclosed eight crew members for two years, aimed to study the viability of sustaining human life in a closed, complex biosphere and to serve as a testbed for future space-based habitats [30] [32].

Beijing Lunar Palace (China)

Lunar Palace 1 (Beijing Lunar Palace), developed by Beihang University, is China's first and the world's third Integrative Experimental Facility for Permanent Astrobase Life-support Artificial Closed Ecosystem (PALACE). Established in October 2013, it represents the current state-of-the-art in BLSS research [33]. The Chinese program synthesized previous international knowledge, including work from the discontinued NASA BIO-Plex program, with domestic innovation to develop a highly advanced system [5]. Its recent successes, such as the 365-day crewed experiment, have positioned China as a leading force in bioregenerative life support technology [5] [33].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major CELSS Projects

| Feature | BIOS-3 | Biosphere 2 | Beijing Lunar Palace |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Krasnoyarsk, Russia | Oracle, Arizona, USA | Beijing, China |

| Operational Start | 1972 | 1991 | 2013 |

| Total Volume | 315 m³ [14] | ~180,000 m³ [32] | Not specified in results |

| Footprint | 14m x 9m [14] | 1.27 Hectares [32] | Not specified in results |

| Primary Goal | Develop closed human life-support ecosystems [14] | Study complex biosphere interactions & human habitation [32] | Demonstrate & verify BLSS for Moon/Mars [33] |

| Number of Crew | Up to 3 [14] | 8 (first mission) [32] | 4 (in long-duration tests) [5] |

Technical Specifications and System Design

The architecture of each CELSS reflects its unique research objectives and technological era, with varying approaches to closure, biological components, and engineering systems.

BIOS-3 Infrastructure and Subsystems

BIOS-3 was a highly controlled, energy-intensive facility. It was divided into four compartments: one served as the crew area with single cabins, a galley, and a control room, while the other three initially functioned as an algal cultivator and two phytotrons (plant growth chambers) [14]. The facility used powerful 20 kW xenon lamps, cooled by water jackets, to provide light levels comparable to sunlight, consuming a total of 400 kW of electricity from a nearby hydroelectric plant [14] [31].

- Atmosphere Regeneration: The primary biological component for air revitalization was Chlorella algae, cultivated in stacked tanks. Approximately 8 m² of exposed Chlorella was required to balance the oxygen and carbon dioxide for one human [14] [31]. A physical-chemical backup system heated the air to 600°C with a catalyst to remove complex organic compounds [14].

- Water and Waste Recycling: The system achieved an 85% water recycling efficiency by 1968 [14]. Nutrients were stored in advance, and while urine and feces were dried and stored, they were not fully integrated into the food production loop [14]. The crew's diet was supplemented with imported dried meat [31].

Biosphere 2's Multi-Biome Engineering

Biosphere 2 was an unparalleled feat of engineering, designed to host seven distinct biomes: a rainforest, a savannah, an ocean with a coral reef, a marsh, a desert, an intensive agricultural area, and a human habitat [32].

- Closure and Pressure Management: A critical innovation was the use of variable-volume chambers called "lungs" to accommodate thermal expansion and contraction of the internal atmosphere without risking the integrity of the sealed structure [32]. The overall atmospheric leakage rate was measured at a remarkably low 10% per year [32].

- Energy and Water Systems: Sunlight, filtered through the massive glass and space-frame structure, was the primary energy source for photosynthesis. A sophisticated condensate system collected water vapor from the air, providing a pure water supply that was balanced with the evapotranspiration from the biomes [32].

- Monitoring and Control: A vast "nerve system" of hundreds of sensors monitored temperature, humidity, light, and gas concentrations, providing immense datasets on the system's dynamics [32].

Beijing Lunar Palace's Integrated BLSS

Lunar Palace 1 is designed as a highly closed, integrated human-animal-plant-microorganism ecosystem [33]. Its system emphasizes the stable, long-term circulation of mass and the health of the crew.

- Biological Components: It incorporates higher plants for food and gas exchange, and its design places a strong emphasis on the role of microorganisms within the recycling loops.

- System Stability and Control: A key achievement of the Lunar Palace team is the development of biological modulation technology to control and adjust the system's stability. This was successfully tested during the "Lunar Palace 365" experiment through crew shift changes and simulated emergencies like power cuts [33].

- Waste Recycling: The system has developed advanced techniques for the long-term recycling, purification, and allocation of nutrient solutions, aiming for a high degree of mass closure [33].

Table 2: Biological and Technical Components Comparison

| System Function | BIOS-3 | Biosphere 2 | Beijing Lunar Palace |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary O₂ Production | Chlorella Algae & Higher Plants [14] | Higher Plants from multiple biomes [32] | Higher Plants in an integrated ecosystem [33] |

| Food Production | Wheat, Vegetables, & imported meat [14] [31] | Intensive Agriculture (crew grown) [32] | Cultivated grains & vegetables [33] |

| Waste Processing | Dried and stored [14] | Biological recycling in soils & systems [30] | Microbial recycling & nutrient solution recovery [33] |

| Water Recovery | Water recycling (85% efficiency) [14] | Condensate collection from air handling [32] | Nutrient solution purification & allocation tech [33] |

| Unique Features | High-temperature catalyst for trace gas removal [14] | Variable-volume "lungs" for pressure buffering [32] | Biological modulation tech for system stability control [33] |

Key Experiments and Methodologies

Ground-based experimental campaigns within these facilities have provided invaluable data and operational experience for closed-system human habitation.

BIOS-3 Crewed Closure Experiments