Comparative Analysis of Plant Gene Families: Methods, Tools, and Applications for Genomic Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the methodologies for comparative analysis of plant gene families, a cornerstone of modern functional genomics.

Comparative Analysis of Plant Gene Families: Methods, Tools, and Applications for Genomic Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the methodologies for comparative analysis of plant gene families, a cornerstone of modern functional genomics. Tailored for researchers and scientists, it bridges foundational concepts with advanced applications. The content systematically explores the evolutionary and functional significance of gene families, details step-by-step analytical workflows using contemporary tools like OrthoFinder and PlantTribes2, and offers practical troubleshooting strategies. It further outlines robust frameworks for validating results and performing cross-species comparisons, empowering researchers to decipher the genetic underpinnings of trait variation, adaptation, and disease resistance in plants.

The Why and What: Foundations of Plant Gene Family Evolution and Function

Defining Gene Families and Their Role in Plant Adaptation and Evolution

Gene families are sets of homologous genes that originate from a common ancestral sequence, primarily through the mechanism of gene duplication [1]. The expansion and contraction of these families are fundamental forces in the evolution of plant genomes, providing the raw genetic material for evolutionary innovation and environmental adaptation [2] [1]. In plants, the high frequency of whole-genome duplication (WGD) and tandem duplication events has resulted in exceptionally dynamic gene families, which are crucial for adapting to environmental stresses such as climate change, pathogen attack, and soil toxicity [2]. The functional divergence of duplicated genes, including the evolution of novel functions or the partitioning of ancestral functions, enables plants to develop complex regulatory networks and adaptive traits [3]. This application note provides a detailed protocol for the comparative analysis of plant gene families, placing these methods within the broader context of a research thesis aimed at understanding the genomic basis of plant adaptation.

Key Concepts and Quantitative Foundations

A gene family is operationally defined as a set of sufficiently similar genes, formed by the duplication of an original gene, and can include both orthologs and paralogs [1]. Phylogenomic studies consistently reveal a positive correlation between the number of paralogs in a genome and its overall size [1]. This relationship underscores the role of gene duplication in genome expansion. Furthermore, recent meta-analyses of 25 plant species, spanning deep evolutionary distances of approximately 300 million years, have demonstrated significant genetic repeatability in local adaptation to climate, identifying 108 gene families (orthogroups) that are repeatedly associated with climatic variables across distantly related species [4].

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from Large-Scale Genomic Analyses

| Observation | Description | Implication for Plant Adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| Correlation with Genome Size | A general positive correlation exists between the number of gene copies (paralogs) and genome size in prokaryotes and plants [1]. | Facilitates genome expansion and provides genetic material for functional innovation. |

| Repeatedly Associated Orthogroups (RAOs) | 108 gene families show statistically significant, repeated associations with adaptation to diverse climate variables across 25 plant species [4]. | Identifies a core set of gene families with conserved adaptive roles in climate response. |

| Pleiotropy of RAOs | Orthogroups with strong evidence for repeated adaptation exhibit greater network centrality and broader expression across tissues (higher pleiotropy) [4]. | Contrary to some theories, genes with broader functional impacts may be key targets of repeated selection. |

| Intron Evolution | Intronless and intron-poor genes have emerged within intron-rich plant gene families, with many playing roles in drought and salt stress response [3]. | Structural gene evolution (intron loss) is linked to adaptive functional specialization, particularly for stress responses. |

Application Notes: Protocol for Gene Family Analysis

This protocol outlines the use of the PlantTribes2 framework for comprehensive gene family analysis, from initial sequence input to evolutionary interpretation [5]. PlantTribes2 is a scalable, accessible tool suite designed for comparative and evolutionary studies using genomic or transcriptomic data.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools and Resources for Plant Gene Family Analysis

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| PlantTribes2 [5] | Analysis Framework | A modular toolkit for gene family assembly, phylogeny, duplication inference, and visualization. |

| PLAZA [6] | Comparative Genomics Platform | Hosts curated plant genomes and pre-computed gene families, orthology relationships, and colinearity data. |

| Phytozome [7] | Genomic Portal | Provides access to sequenced plant genomes and gene families, enabling clade-specific orthology/paralogy analysis. |

| OrthoFinder2 [4] | Orthology Inference Software | Reconstructs orthology relationships across multiple species and classifies genes into orthogroups. |

| GENESPACE [7] | Synteny Visualization Tool | Tracks regions of interest and gene copy number variation across multiple genomes to explore pangenome views. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Step 1: Data Input and Preparation

- Input: Provide annotated protein sequences in FASTA format from genome assemblies or transcriptomes. For well-studied species, high-quality annotations are available in databases like PLAZA [6] or Phytozome [7].

- Quality Control: Assess the quality of gene model annotations. PlantTribes2 can be used to improve transcript models prior to analysis [5].

Step 2: Gene Family Assignment (Orthogroup Clustering)

- Objective: Sort protein sequences into orthologous gene family clusters (orthogroups).

- Method: Use the PlantTribes2 "Gene Family Scaffolder" tool. This tool compares your input sequences to pre-computed orthogroups derived from a set of high-quality reference plant genomes [5].

- Alternative: For novel analyses or non-model organisms, run OrthoFinder2 independently to infer orthogroups de novo from your dataset and any relevant public genomes [4].

Step 3: Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogeny Reconstruction

- Alignment: For a gene family of interest, use the PlantTribes2 "Multiple Sequence Alignment" tool with algorithms like MAFFT or ClustalO to generate an alignment of member protein or nucleotide sequences [5].

- Phylogenetic Inference: Construct a gene tree using the "Gene Family Phylogeny" tool. Maximum Likelihood methods (e.g., IQ-TREE) implemented within the pipeline are recommended for robustness [5].

Step 4: Inference of Evolutionary Events and Selective Pressure

- Duplication Inference: The "Genome Duplication" tool reconciles the gene tree with the species tree to identify large-scale and small-scale duplication events, which are key to gene family expansion [5].

- Selection Analysis: Calculate synonymous ((dS)) and non-synonymous ((dN)) substitution rates for pairs of homologous sequences using the PlantTribes2 tool. A (dN/dS) ratio >1 indicates positive selection, while <1 suggests purifying selection [5].

Step 5: Integration with Functional and Phenotypic Data

- Functional Annotation: Overlay functional data (e.g., Gene Ontology terms) from the scaffolded gene families or external databases onto the phylogenetic tree.

- Genotype-Environment Association (GEA): To link gene families to adaptation, perform GEA analysis. For example, associate population-level allele frequencies for genes within a family with climatic variables (e.g., from WorldClim) using Kendall’s τ correlation, followed by a meta-analysis across species to identify Repeatedly Associated Orthogroups (RAOs) [4].

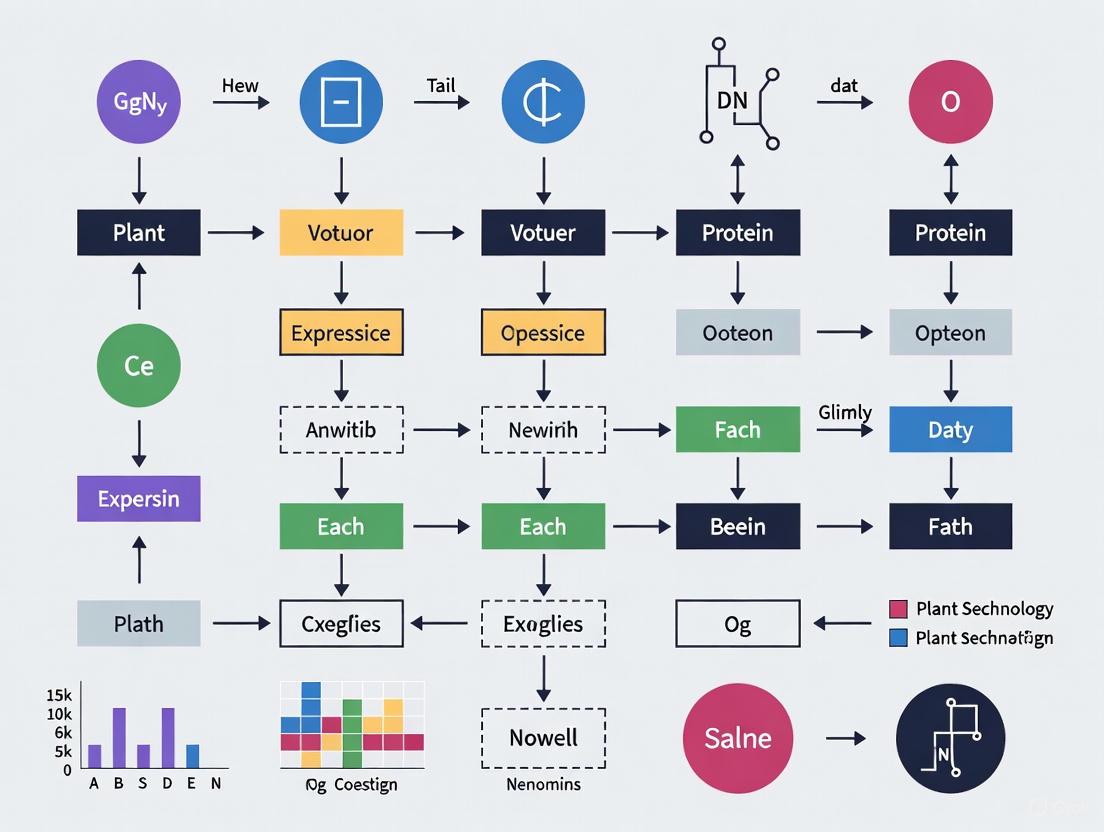

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated steps of this protocol.

Results and Data Interpretation

The application of this protocol yields several key outputs for interpretation:

- Gene Family Phylogeny: A phylogenetic tree reveals evolutionary relationships among family members. Clades containing genes from a single species indicate lineage-specific expansions (e.g., tandem duplications), while clades mixing genes from multiple species suggest expansions predating speciation (e.g., from WGD) [5] [6].

- Inferred Duplication Events: The reconciliation of gene and species trees identifies specific duplication nodes. A high frequency of duplication in a gene family, particularly one associated with stress response, points to its adaptive role [2] [4].

- Selection Signatures: The detection of positive selection ((dN/dS > 1)) on specific branches or within clades provides evidence for adaptive evolution following duplication [5].

- RAO Identification: The orthogroups that show repeated associations with environmental variables across independent species represent high-confidence candidates for genes with conserved adaptive functions [4]. For instance, the protocol would flag orthogroups associated with "maximum temperature in the warmest month" for further functional validation.

Discussion and Research Applications

The integration of phylogenomics, epigenetic regulation, and protein dynamics is essential for a holistic understanding of how gene families drive plant evolution and adaptation [2]. The discovery of 108 Repeatedly Associated Orthogroups (RAOs) for climate adaptation demonstrates that evolution is significantly repeatable across deep evolutionary time and highlights a core set of gene families critical for environmental resilience [4]. This finding has profound implications for predicting how wild and crop species may respond to anthropogenic climate change.

The following diagram contextualizes the role of gene family analysis within the broader cycle of a plant comparative genomics research thesis.

Furthermore, structural variations within gene families, such as the emergence of intronless or intron-poor genes within otherwise intron-rich families, are linked to specialized functions in abiotic stress response [3]. This suggests that changes in gene structure are another evolutionary avenue for adaptation.

In conclusion, the precise definition and analysis of gene families are foundational to dissecting the genetic architecture of complex traits and adaptive responses in plants. The protocols and resources detailed here provide a roadmap for researchers to generate biologically meaningful insights, which can be further validated through experimental studies of epigenetic regulation and protein function, ultimately contributing to the development of climate-resilient crops [2].

Structural variants (SVs) and copy number variations (CNVs) represent a significant source of genomic diversity, driving phenotypic variation and environmental adaptation in plants. SVs are defined as genomic alterations affecting more than 50 base pairs, encompassing insertions, deletions, duplications, inversions, and translocations [8] [9]. CNVs, a specific category of unbalanced SVs, result from the gain (duplication) or loss (deletion) of DNA segments, leading to variation in the number of copies of a particular genomic region [9]. These large-scale variations can drastically alter gene content and genome architecture, influencing gene expression, protein function, and ultimately, phenotypic traits [10] [8].

In plant genomics, SVs and CNVs have emerged as pivotal drivers of evolutionary innovation and agricultural improvement. Unlike single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), SVs can affect multiple genes simultaneously and are more likely to cause large-scale genomic perturbations [9]. Recent studies leveraging pangenome approaches—which capture the complete genetic repertoire across multiple individuals of a species—have revealed that SVs are responsible for extensive presence-absence variations (PAVs) of genes, uncovering SV-linked agronomic traits that traditional single-reference genome-based approaches often overlook [10]. The functional impact of these variations spans from modulating disease resistance and stress adaptation to influencing fruit ripening, flavor, and flower development [10] [8] [9].

Table 1: Categories and Functional Impact of Major Genomic Variations

| Variation Type | Size Range | Structural Classes | Potential Functional Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Variants (SVs) | >50 bp to several Mb | Insertions, Deletions, Inversions, Translocations, Duplications [8] [9] | Gene disruption, altered gene regulation, fusion genes, presence-absence variation (PAV) [10] [9] |

| Copy Number Variants (CNVs) | 50 bp to several Kb | Tandem duplications, Segmental duplications, Deletions [9] | Altered gene dosage, changes in expression levels, functional redundancy, novel traits [9] [11] |

Experimental Protocols for SV and CNV Analysis

Genome-Wide CNV Profiling Using Read-Depth Analysis

Principle: This protocol estimates copy number by analyzing the depth of sequencing reads aligning across genomic regions. Regions with significantly higher or lower read depth compared to a reference indicate duplications or deletions, respectively [9].

Materials:

- Reagent Solutions: High-quality genomic DNA, library preparation kit, sequencing reagents, mrsFAST aligner, mrCaNaVaR algorithm, RepeatMasker, Tandem Repeats Finder.

Procedure:

- DNA Extraction & Sequencing: Extract high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from plant tissue. Prepare a whole-genome sequencing library and sequence using an Illumina platform to generate short-read data [9].

- Reference Genome Preparation: Download a high-quality reference genome. Mask common and tandem repeats using RepeatMasker and Tandem Repeats Finder to improve mapping accuracy [9].

- Read Mapping: Map the sequencing reads to the repeat-masked reference genome using the mrsFAST aligner, limiting the mismatch rate to 5% of the read length for stringent alignment [9].

- CNV Calling: Use the mrCaNaVaR algorithm to predict integer copy numbers. The tool calculates read depth distribution in sliding windows and identifies segmental duplications and deletions based on excess or reduced depth of coverage [9].

- Validation: Perform quality control by mapping a subset of reads to the unmasked reference genome to assess mapping rates and potential biases.

Identification of Large SVs via Long-Read Sequencing and Comparative Assembly

Principle: Long-read sequencing technologies generate reads spanning thousands of base pairs, enabling the detection of large, complex SVs that are often missed by short-read technologies. Comparative assembly of different accessions reveals divergent regions [8].

Materials:

- Reagent Solutions: Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) HiFi or Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) sequencing reagents, Hi-C library kit, Hifiasm/HiCanu/Flye assemblers, whole-genome aligner.

Procedure:

- Long-Read Sequencing & Assembly: Sequence the target plant genome using PacBio HiFi or ONT. Assemble the reads into contigs using assemblers like Hifiasm or HiCanu to produce a phased, haplotype-resolved genome assembly [8].

- Assembly Quality Assessment: Evaluate assembly completeness and contiguity using metrics like N50 and BUSCO. Compare assemblies generated by different tools to resolve inconsistencies [8].

- Whole-Genome Alignment: Perform pairwise whole-genome alignment between the newly assembled genome and a reference genome using a tool like MUMmer to identify large-scale divergent regions [8].

- SV Characterization: Annotate the identified SV regions for gene content using tools like Prokka and for repetitive elements using RepeatMasker. Investigate the enrichment of specific transposable element superfamilies (e.g., MUDR-Mutator) within the SVs [8].

- Population-Level Validation: Map short-read data from multiple accessions to the new assembly to assess the variability and prevalence of the discovered SV across a population [8].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genomic Variation Studies

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PacBio HiFi Reads | Long-read sequencing for high-fidelity, contiguous genome assembly. | Resolving complex haplotype-specific SVs in cassava [8]. |

| Oxford Nanopore MinION | Long-read sequencing for real-time SV detection. | Detecting SVs in Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes [12]. |

| Hi-C Library Kit | Capturing chromatin interaction data for scaffolding. | Achieving chromosome-scale genome assembly for SV analysis [8]. |

| mrsFAST Aligner | Ultra-fast mapping of short reads for read-depth analysis. | Mapping reads for CNV detection in apple genomes [9]. |

| mrCaNaVaR Algorithm | Read-depth-based tool for predicting integer copy numbers. | Profiling gene CNVs across 116 Malus accessions [9]. |

| Roary | Rapid pangenome analysis pipeline for bacterial species. | Constructing the pangenome of symbiotic Bradyrhizobium [13]. |

Signaling Pathways and Functional Networks Influenced by SVs and CNVs

Genomic variations are not isolated events; they directly impact the structure and regulation of key biological pathways. The diagram below illustrates how SVs and CNVs influence the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway, a well-characterized system in plants.

Pathway Logic: The pathway begins with phenylalanine and proceeds through a series of enzymatic steps catalyzed by proteins like chalcone synthase (CHS) and flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H). A critical branchpoint occurs at dihydroflavonols, where flavonol synthase (FLS) and dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR) compete for substrates. SVs and CNVs, particularly tandem duplications, can drive the expansion of the DFR gene family [14]. This expansion alters enzyme dosage and can lead to neofunctionalization, changing substrate specificity (e.g., creating Asn-, Asp-, or Arg-type DFRs) and ultimately shifting metabolic flux toward anthocyanin production over flavonols, affecting pigmentation and stress responses [14].

Integrated Workflow for Comparative Analysis of Plant Gene Families

A robust analysis of how SVs and CNVs shape gene family evolution requires an integrated workflow that combines comparative genomics, functional genetics, and evolutionary biology.

Workflow Description: The process begins with sequencing and assembling genomes from multiple accessions or species to build a pangenome resource that captures species-wide genetic diversity [10]. The pangenome is partitioned into core (shared) and accessory (variable) gene pools, which are heavily influenced by SVs [13]. Specific SV and CNV loci are then detected using read-depth or assembly-based methods [8] [9]. Next, gene families of interest are identified from the pangenome, and their evolutionary relationships are reconstructed using phylogenetics [14]. The identified SVs/CNVs are statistically associated with phenotypic traits to prioritize causal variations [9] [11]. Finally, the role of SVs/CNVs in gene family evolution and function is validated through expression analysis (e.g., RNA-seq) and functional genetics [10] [11].

Table 3: Quantitative Insights from Recent Genomic Variation Studies

| Study System | Key Finding | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Apple Domestication (Malus) [9] | >20,000 genes showed differing CN profiles between species; genes for fruit flavor & anthocyanins had higher copy number in domesticated apples. | CNVs are a key driver of domestication traits, providing targets for fruit quality improvement. |

| Cassava (Manihot esculenta) [8] | Discovery of a 9.7 Mbp haplotype-specific insertion on chromosome 12, enriched with MUDR transposons and deacetylase genes. | Highlights the role of large SVs and TEs in genomic diversity of clonally propagated crops. |

| DFR Gene Family (237 Plant Species) [14] | DFR family originated in ferns/seed plants; tandem duplications primary force for expansion and emergence of Asn/Asp substrate types. | Clarifies the evolutionary mechanism behind diversity in a key flavonoid pathway gene. |

| Mycorrhizal Symbiosis (42 Angiosperms) [11] | Expanded gene families in mycorrhizal plants showed 200% more context-dependent expression; expansions primarily from tandem duplications. | Tandem duplications provide molecular flexibility for fine-tuning symbiotic interactions with the environment. |

Gene duplication is a fundamental evolutionary process that provides the raw genetic material for innovation. Following duplication, genes primarily face three evolutionary fates: nonfunctionalization (loss of function), neofunctionalization (acquisition of new function), and subfunctionalization (partitioning of ancestral functions) [15]. The initial preservation of duplicates is often influenced by gene dosage effects, particularly following whole-genome duplication events, where maintaining stoichiometric balance in protein complexes creates selective pressure to retain both copies [16] [17]. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for comparative gene family analysis in plants, where whole-genome duplications are prevalent and have driven adaptation and domestication [16] [18].

This article outlines practical protocols for analyzing these evolutionary forces, using recent plant genomics studies as models. The principles are broadly applicable to investigating gene family evolution across taxa.

Core Concepts and Analytical Framework

Defining the Key Evolutionary Mechanisms

- Neofunctionalization: occurs when one paralog acquires a completely novel function through adaptive mutation, while the other retains the original function. This process is considered rare because it requires a series of advantageous mutations rather than degenerative ones [15].

- Subfunctionalization: involves both duplicates undergoing complementary loss-of-function mutations, resulting in the partitioning of the ancestral gene's subfunctions. Both copies are thus preserved because together they reconstitute the original functional spectrum [19].

- Gene Dosage Effects: immediately after whole-genome duplication, purifying selection often maintains both copies to preserve stoichiometric balance in multiprotein complexes. This dosage balance acts as a temporary mechanism, prolonging duplicate retention and providing an evolutionary window for subsequent neo- or sub-functionalization to occur [16] [17].

- Neosubfunctionalization: describes an evolutionary trajectory where subfunctionalization serves as an intermediate stage, eventually leading to neofunctionalization in one or both copies [15].

Quantitative Patterns of Gene Family Evolution

Table 1: Evolutionary Patterns in Plant Gene Families

| Gene Family | Evolutionary Force | Genomic Evidence | Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| NLR genes in Asparagus [20] | Gene family contraction | Reduction from 63 NLRs in wild A. setaceus to 27 in cultivated A. officinalis | Increased disease susceptibility in domesticated species |

| 14-3-3 genes in Brassicaceae [18] | Purifying selection | Expansion following WGD, with ε-group experiencing weaker selective constraints | Functional conservation in growth, development, and stress responses |

| Antifreeze protein in fish [15] | Neofunctionalization | Duplicated sialic acid synthase gene acquired ice-binding function | Adaptation to frigid Antarctic environments |

| Visual opsin genes in vertebrates [15] | Repeated neofunctionalization | Series of duplications led to five opsin classes with distinct light absorption | Color vision and dim-light vision capabilities |

Table 2: Reagent Solutions for Evolutionary Genomics

| Research Reagent / Tool | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| OrthoFinder [20] | Orthogroup inference and phylogenetic orthology analysis | Identifying conserved NLR gene pairs between A. setaceus and A. officinalis [20] |

| MEME Suite [20] | Discovery of conserved protein motifs | Characterizing NB-ARC domain architecture in NLR proteins [20] |

| PlantCARE [20] | Identification of cis-acting regulatory elements | Analyzing promoter regions of NLR genes for defense-related elements [20] |

| InterProScan [20] | Protein domain classification and functional analysis | Validating NLR domain structure (NBS, LRR, TIR/CC/RPW8) [20] |

| MEGA [21] | Phylogenetic tree construction and evolutionary analysis | Reconstructing evolutionary relationships of CNGC or 14-3-3 gene families [21] [18] |

| BEDTools [20] | Genomic interval operations and cluster analysis | Identifying chromosomal clustering of NLR genes [20] |

Protocol: Comparative Analysis of Gene Family Evolution

Genome-Wide Identification and Classification

Objective: Comprehensively identify members of a target gene family across multiple species and classify them based on domain architecture.

Materials: Genome assemblies and annotation files for target species; reference sequences from model organisms; computational tools (HMMER, BLAST+, InterProScan, Pfam database).

Procedure:

- Sequence Retrieval:

Homology-Based Identification:

Domain Validation and Classification:

- Process candidate sequences through InterProScan and NCBI's CD-Search to validate domain composition [20].

- Retain only sequences containing characteristic domain architectures (e.g., NB-ARC for NLRs; cNMP-binding and ion transport for CNGCs) [20] [21].

- Classify genes into subfamilies based on specific domains (e.g., CNLs, TNLs, RNLs for NLRs; ε and non-ε for 14-3-3 proteins) [20] [18].

Evolutionary and Phylogenetic Analysis

Objective: Reconstruct evolutionary relationships, identify orthologs/paralogs, and detect signatures of selection.

Materials: Multiple sequence alignment software (Clustal Omega, MUSCLE); phylogenetic tools (MEGA, IQ-TREE); selection analysis programs (PAML, HyPhy).

Procedure:

- Multiple Sequence Alignment:

Phylogenetic Reconstruction:

Orthology and Synteny Analysis:

- Use OrthoFinder to identify orthogroups across species [20].

- Perform synteny analysis using MCScanX or similar tools to identify conserved genomic blocks.

- Map gene duplication events (tandem, segmental, WGD) onto phylogenetic contexts.

Selection Pressure Analysis:

- Calculate nonsynonymous/synonymous substitution rates (dN/dS) using codeml in PAML or similar tools.

- Identify sites under positive selection (dN/dS > 1) or purifying selection (dN/dS < 1) [18].

- Compare selection pressures between different gene subfamilies or phylogenetic groups.

Case Study: NLR Gene Family in Asparagus

Experimental Design and Phenotypic Context

A comparative analysis of NLR (Nucleotide-binding Leucine-rich Repeat) genes in garden asparagus (Asparagus officinalis) and its wild relatives (A. setaceus and A. kiusianus) revealed how domestication impacted disease resistance mechanisms [20]. The study combined genomic, transcriptomic, and pathogen inoculation assays.

Pathogen Response Assay:

- Objective: Compare phenotypic responses to Phomopsis asparagi infection between species.

- Method: Inoculate plants with fungal pathogen under controlled conditions.

- Results: Distinct phenotypic responses were observed - A. officinalis was susceptible, while A. setaceus remained asymptomatic [20].

Genomic and Expression Analyses

Gene Family Quantification:

- Identified 63, 47, and 27 NLR genes in A. setaceus, A. kiusianus, and A. officinalis, respectively, demonstrating marked gene family contraction during domestication [20].

Orthologous Group Analysis:

- Used OrthoFinder to identify 16 conserved NLR gene pairs between A. setaceus and A. officinalis, representing NLRs preserved during domestication [20].

Expression Profiling:

- Analyzed transcriptomic data after fungal challenge.

- Found that most preserved NLR genes in A. officinalis showed unchanged or downregulated expression following infection, suggesting functional impairment in disease resistance mechanisms [20].

Interpretation of Evolutionary Forces

The study demonstrated that domestication led to:

- Gene family contraction through nonfunctionalization (loss of NLR genes).

- Possible subfunctionalization in retained NLRs, with altered expression patterns.

- Relaxed selection on defense mechanisms, potentially due to artificial selection for yield and quality traits [20].

This case study provides a protocol for linking genomic changes to phenotypic outcomes during domestication, highlighting the interplay between different evolutionary forces.

Emerging Approaches and Foundation Models

Recent advances in foundation models (FMs) are transforming evolutionary genomics. Plant-specific FMs such as GPN-MSA, AgroNT, and PlantCaduceus address challenges like polyploidy, high repetitive sequence content, and environment-responsive regulatory elements [22]. These models can:

- Predict functional effects of genetic variants across species.

- Identify regulatory elements and non-coding RNAs.

- Model protein structure-function relationships.

- Generate hypotheses about gene family evolution [22].

When incorporating these tools, consider:

- Using DNA-level FMs (e.g., Nucleotide Transformer, HyenaDNA) for promoter analysis and cis-regulatory element prediction.

- Applying protein-level FMs (e.g., ESM series, AlphaFold3) to understand structural consequences of amino acid changes in duplicated genes.

- Leverating single-cell FMs for resolving expression patterns in complex tissues [22].

These approaches complement traditional comparative genomics and enable more sophisticated analysis of evolutionary forces shaping gene families.

In plant comparative genomics, accurately identifying evolutionary relationships between genes is a foundational step for research on gene function, genome evolution, and trait diversity. Homology describes the relationship between any two genes that share a common ancestral sequence [23]. This broad category is precisely divided into two critical classes based on the evolutionary event that led to their divergence: orthologs and paralogs [24] [23]. Orthologs are genes in different species that originated from a single gene in the last common ancestor of those species, having diverged through a speciation event [25] [24]. In contrast, paralogs are genes related by gene duplication within a genome and may subsequently evolve new functions [24] [23].

The practical distinction between these categories is crucial. It is generally accepted that orthologs are likely to retain the same biological function across different species, making them primary targets for functional gene annotation transfer from model organisms like Arabidopsis thaliana to crops [25] [24]. Paralogs, having arisen from duplication, are more likely to undergo neofunctionalization or subfunctionalization, and are therefore often studied to understand functional innovation [24]. These concepts are extended to the orthogroup, defined as the set of all genes—including both orthologs and paralogs—descended from a single gene in the last common ancestor of all species under consideration [26]. The orthogroup provides a comprehensive framework for multi-species comparison, which is especially valuable for plant genomes with complex histories of duplication and loss [26] [27].

Key Terminology and Classifications

The relationships between homologous genes can be further refined based on specific evolutionary scenarios [24]:

- One-to-one orthologs: A single gene in one species is orthologous to a single gene in another species.

- One-to-many/Many-to-many orthologs: A single gene in one species is orthologous to multiple genes in another species, typically due to a duplication event in one lineage after speciation.

- In-paralogs: Paralogs that resulted from a duplication event after a given speciation event. These genes are co-orthologous to a gene in another species.

- Out-paralogs: Paralogs that resulted from a duplication event before a given speciation event.

- Co-orthologs: Two or more genes in one species (in-paralogs) that are collectively orthologous to a single gene (or a set of in-paralogs) in another species.

- Homoeologs: A specific type of homolog found in polyploid species, originating from speciation and brought together in the same genome by hybridization (allopolyploidization) [24].

Table 1: Summary of Key Terminology in Orthology and Paralogy

| Term | Definition | Evolutionary Event | Functional Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homolog | Genes sharing a common ancestor | Any | Shared ancestry, function may vary |

| Ortholog | Genes diverged through speciation | Speciation | High probability of functional conservation |

| Paralog | Genes diverged through gene duplication | Gene Duplication | Potential for functional diversification |

| Orthogroup | Set of all genes from multiple species descended from a single ancestral gene | N/A (grouping unit) | Enables comprehensive multi-species comparison |

Inference methods are broadly classified into two paradigms: graph-based and tree-based approaches [28] [24].

Graph-Based Approaches

Graph-based methods are computationally efficient and scale well for large numbers of genomes. They typically operate in two phases [24]:

- Graph Construction: Genes are represented as nodes in a graph, and edges are drawn between them based on sequence similarity. A common starting point is the Reciprocal Best Hit (RBH or BBH), where two genes from different species are each other's best match [24]. While precise, RBH fails to capture one-to-many and many-to-many orthology relationships.

- Clustering: The graph is partitioned into clusters (orthogroups) using algorithms like Markov Clustering (MCL), which identifies densely connected regions [26] [24]. Tools like InParanoid extend RBH by identifying in-paralogs, thus capturing co-orthology relationships [24]. OrthoMCL is a widely used method that applies MCL to a graph of sequence similarities [26].

Tree-Based Approaches

Tree-based methods, also known as phylogenomic approaches, solve the more general problem of gene tree-species tree reconciliation [29] [25] [24]. The process involves:

- Gene Family Clustering: Homologous genes from multiple species are grouped into families.

- Multiple Sequence Alignment and Tree Building: A multiple sequence alignment is generated for the family, and a gene tree is inferred.

- Tree Reconciliation: The gene tree is compared to the known species tree. Each node in the gene tree is annotated as a speciation or duplication event. Genes coalescing at a speciation node are orthologs, while those at a duplication node are paralogs [24].

This method is considered more accurate as it explicitly models evolutionary history but is computationally intensive and requires a known species tree [25] [24].

Addressing Bias: The OrthoFinder Algorithm

A significant advancement in graph-based methods came with the identification of a fundamental gene length bias in orthogroup inference. Traditional methods relying on BLAST scores are biased because short sequences cannot achieve high scores, leading to their exclusion from orthogroups (low recall), while long sequences produce many high-scoring hits, causing incorrect cluster merging (low precision) [26].

OrthoFinder introduced a novel length-normalization transform for BLAST bit scores. It models the relationship between sequence length and alignment score for each species-pair independently and then normalizes all scores, ensuring that the best hits for short and long genes are comparable [26]. This innovation, combined with the use of Reciprocal Best Normalised Hits (RBNH), dramatically improved accuracy, reducing gene length dependency and increasing both precision and recall [26].

Incorporating Synteny for Reliable Orthology

For species with high-quality genome assemblies, synteny—the conservation of gene order on chromosomes—provides powerful additional evidence for orthology. Synteny is particularly useful for identifying paralogs derived from ancient whole-genome duplications (WGDs), which are common in plants [30]. A study on Brassicaceae demonstrated that synteny-based ortholog identification reliably yielded more orthologs and allowed for confident paralog detection compared to conventional methods like OrthoFinder alone. The syntenic gene sets covered a wider range of gene functions, making them highly suitable for studies linking phylogenomics to trait evolution [30].

Table 2: Comparison of Major Orthology Inference Methods

| Method | Type | Key Features | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBH / BBH | Graph-based | Reciprocal Best BLAST Hit | Fast, high precision | Misses one-to-many orthologs |

| InParanoid | Graph-based | Identifies in-paralogs around RBH | Captures co-orthology | Limited to two species |

| OrthoMCL | Graph-based | Applies MCL to BLAST graph | Scalable to multiple species | Suffers from gene-length bias |

| OrthoFinder | Graph-based | Gene-length normalization, RBNH | High accuracy, scalable, infers species tree | Relies on sequence similarity only |

| Synteny-Based | Evidence-based | Uses conserved gene order | Highly reliable, identifies WGD paralogs | Requires high-quality genomes |

| Tree Reconciliation | Tree-based | Gene/species tree comparison | Evolutionarily accurate, models history | Computationally slow, needs species tree |

Experimental Protocol: Orthogroup Inference Using OrthoFinder

This protocol details a standard workflow for inferring orthogroups from protein sequences of multiple plant species using OrthoFinder, a highly accurate and widely used tool [26] [27].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Software Tools

| Item | Function/Description | Example or Note |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Sequence Files | Input data in FASTA format (.fa, .fasta). | One file per species, containing all annotated protein sequences. |

| OrthoFinder Software | The core program for orthogroup inference. | Install via Conda, Docker, or from source [26]. |

| BLAST+ | Computes pairwise sequence similarities. | Often bundled with OrthoFinder. |

| MSA Tool | For multiple sequence alignment. | e.g., MAFFT, required for gene tree generation. |

| Gene Tree Tool | For inferring phylogenetic trees. | e.g., FastTree, required for gene tree generation. |

| Species Tree Tool | For inferring species trees from gene trees. | e.g., ASTRAL, optional within OrthoFinder. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Environment for computation. | Essential for large datasets (e.g., >10 species). |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Preparation

- Obtain proteome files for all species to be analyzed. Ensure consistent and high-quality gene annotations.

- Place all proteome FASTA files in a single directory (e.g.,

protein_fastas/).

Software Installation

- Install OrthoFinder and its dependencies. Using Bioconda is recommended:

conda install -c bioconda orthofinder.

- Install OrthoFinder and its dependencies. Using Bioconda is recommended:

Running OrthoFinder (Basic Inference)

- Execute a basic run with the command:

- This command will automatically run BLAST, perform length normalization, cluster sequences into orthogroups, and output the results.

Running OrthoFinder (With Gene Trees)

- For a more comprehensive analysis including gene trees and a species tree, use:

-M msa: Use multiple sequence alignment for gene tree inference.-S diamond: Use DIAMOND for faster sequence searches (BLAST alternative).-T fasttree: Use FastTree for gene tree inference.

Output Analysis

- OrthoFinder generates results in a dated output directory. Key files include:

Orthogroups/Orthogroups.tsv: The core file listing all orthogroups and their constituent genes.Orthogroups/Orthogroups.txt: The same information in a different format.Orthogroups/Orthogroups_SingleCopyOrthologues.txt: List of single-copy orthogroups.Gene_Trees/: Directory containing inferred gene trees for each orthogroup.Species_Tree/: Directory containing the inferred species tree.

- OrthoFinder generates results in a dated output directory. Key files include:

Downstream Validation and Application

- Validation: For critical gene families, manually inspect gene trees and alignments. In plants, use synteny information where available to confirm orthology/paralogy predictions, especially for genes in complex duplicated regions [30].

- Application: Use the orthogroups for downstream analyses such as gene family expansion/contraction studies, positive selection analysis, or as a basis for phylogenetic inference.

Diagram: Workflow for orthology inference, showing graph-based (top) and tree-based (bottom) paths, with key innovations highlighted.

Application in Plant Gene Family Research: A Case Study in Brassicaceae

The Brassicaceae family, which includes Arabidopsis thaliana and numerous crops, serves as an excellent model for orthology analysis due to shared whole-genome duplications and complex genomic histories [27] [30]. A benchmark study evaluated four algorithms—OrthoFinder, SonicParanoid, Broccoli, and OrthNet—on eight Brassicaceae genomes, including diploids and polyploids [27].

The study found that orthogroup compositions generally reflected the known ploidy and genomic histories of the species. For instance, diploid species showed predominantly single-copy relationships, while mesopolyploids and hexaploids exhibited more complex patterns with more genes per orthogroup [27]. While the core results from OrthoFinder, SonicParanoid, and Broccoli were largely comparable and useful for initial predictions, OrthNet (which incorporates gene colinearity) was an outlier, suggesting that different methodologies can yield distinct groupings [27]. This underscores the importance of selecting an appropriate algorithm and potentially using synteny for fine-tuning.

For example, a focused analysis of the YABBY gene family, a plant-specific transcription factor family, revealed that while most algorithms identified the same core orthogroups, there were discrepancies in the exact gene composition within them [27]. This highlights that orthology inference, while powerful, is not infallible. For critical applications, confirming predictions with phylogenetic tree inference and synteny information is a necessary step to ensure biological accuracy [27] [30].

In the field of plant comparative genomics, interpreting genomic signatures is fundamental to understanding how evolutionary forces shape gene families and, ultimately, plant diversity and adaptation. Genomic signatures are patterns within DNA sequences that reveal the action of evolutionary processes such as mutation, genetic drift, and selection [31]. Selection pressure, quantified by metrics like the Ka/Ks ratio (non-synonymous to synonymous substitution rate), determines whether genetic changes are neutral, beneficial, or deleterious [32]. Together with evolutionary dynamics—the changes in gene and genome architecture over time—these signatures allow researchers to decipher the functional history and adaptive potential of plant gene families [5] [32].

The integration of these analyses into comparative gene family studies provides a powerful framework for linking genetic variation to important agronomic traits. This is particularly relevant for foundational research in crop improvement, conservation biology, and understanding plant responses to environmental stress [31] [33]. This Application Note provides detailed protocols for detecting and interpreting these signatures, framed within the context of plant gene family research.

Key Genomic Signatures and Analytical Methods

The following table summarizes the primary genomic signatures, their biological significance, and the core methods used for their detection in plant gene family analysis.

Table 1: Key Genomic Signatures and Analytical Methods

| Genomic Signature | Biological Significance | Core Analytical Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Ka/Ks Ratio | Measures selection pressure on protein-coding genes. Ka/Ks > 1 indicates positive selection; < 1 indicates purifying selection; ≈ 1 indicates neutral evolution [32]. | Calculation from aligned coding sequences (CDS) using tools like wgd [32]. |

| Selective Sweeps | Genomic regions where diversity has been reduced due to strong positive selection, often linking a beneficial allele to adaptation [33]. | Population genetics statistics (e.g., π, Tajima's D, FST); sliding window analyses across genomes [33]. |

| Gene Presence-Absence Variation (PAV) | Reveals gene gain or loss within a gene family across a pan-genome, contributing to functional variation and adaptation [32]. | Pan-genome construction from multiple high-quality genomes; clustering of homologous genes [32]. |

| Genotype-Environment Association (GEA) | Identifies loci under local adaptation by correlating genetic variation with environmental factors [33]. | Statistical models (e.g., Latent Factor Mixed Models - LFMM) testing allele frequency against environmental variables [33]. |

Computational Workflow for Gene Family Analysis

A robust analytical workflow is essential for accurate inference of evolutionary dynamics. The following diagram outlines a generalized protocol for a comparative plant gene family study.

Figure 1: A generalized computational workflow for comparative analysis of plant gene families, from data acquisition to biological interpretation.

Protocol 1: Gene Family Identification and Alignment

This protocol details the steps for identifying members of a gene family across multiple plant genomes and producing a high-quality multiple sequence alignment, a prerequisite for all downstream evolutionary analyses.

Applications: Identification of orthologs and paralogs; construction of core gene families for phylogenetic analysis; pan-genome analysis of gene content [5] [32].

Materials:

- Input Data: Annotated protein or coding sequence (CDS) files for your target species and reference genomes. High-quality genome assemblies are critical [32].

- Software/Tools: A gene family clustering tool is required. The PlantTribes2 framework is highly recommended for its plant-centric resources and accessibility via the Galaxy platform [5]. Alternative tools include OrthoFinder.

- Computing Resources: A standard laptop may suffice for small families, but server or cloud computing access is recommended for genome-scale analyses [34].

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Gather the annotated protein FASTA files for all species in your analysis. Ensure consistent annotation quality to avoid artifacts.

- Gene Family Clustering: Use a tool like PlantTribes2 to cluster all protein sequences into orthogroups (gene families). This step groups homologous genes (orthologs and paralogs) based on sequence similarity.

- Family Selection: Extract the orthogroup corresponding to your gene family of interest (e.g., JAZ genes, TCP transcription factors).

- Multiple Sequence Alignment: Align the protein sequences within the orthogroup using a tool like MAFFT [35]. For codon-based analysis like Ka/Ks, back-translate the protein alignment to the corresponding CDS alignment to maintain the correct reading frame.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Poor Alignment: Manually inspect and trim the alignment. Remove poorly aligned regions or sequences with excessive gaps that may be mis-annotated.

- Computational Time: For large gene families, use the parallel processing options available in tools like MAFFT or perform analyses on a high-performance computing (HPC) cluster or cloud environment [34].

Protocol 2: Calculating Selection Pressure (Ka/Ks)

This protocol describes how to calculate the ratio of non-synonymous (Ka) to synonymous (Ks) substitution rates to infer selection pressure acting on a gene or gene family.

Applications: Identifying genes under positive selection during domestication or adaptation; assessing functional constraint on conserved genes; detecting divergent selection between paralogs [32].

Materials:

- Input Data: A high-quality multiple sequence alignment of coding sequences (CDS) from Protocol 1.

- Software/Tools: Software for calculating Ka/Ks ratios, such as

wgd(whole-genome duplication analysis tool) orTBtools[32]. - Computing Resources: Command-line interface for

wgd; graphical interface forTBtools.

Procedure:

- Input Alignment: Provide the CDS alignment file to your chosen software.

- Phylogenetic Tree: A phylogenetic tree of the sequences is often required. Construct this using a maximum likelihood method (e.g., RAxML, IQ-TREE) on the aligned sequences [32].

- Ka/Ks Calculation: Run the Ka/Ks analysis tool, referencing the alignment and the phylogenetic tree. Models can range from a single average Ka/Ks for all branches to complex branch-site models that test for positive selection on specific lineages.

- Interpretation:

- Ka/Ks << 1: Suggests purifying (negative) selection, where most non-synonymous mutations are harmful and removed. Typical for highly conserved genes.

- Ka/Ks ≈ 1: Suggests neutral evolution, where mutations are neither beneficial nor harmful.

- Ka/Ks > 1: Suggests positive (diversifying) selection, where non-synonymous mutations are advantageous and fixed. For example,

CsJAZ1,CsJAZ8, andCsJAZ9in tea plants showed Ka/Ks > 1, indicating positive selection during domestication [32].

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Saturation of Ks: At high divergence levels, Ks can become saturated (approach 1), making the Ka/Ks ratio unreliable. This analysis is best for moderately diverged sequences.

- Complex Models: For advanced tests of positive selection (e.g., branch-site models), use software like PAML (CodeML), which requires a configured null model and likelihood ratio test for statistical significance.

Case Study: JAZ Gene Family in Tea Plant (Camellia sinensis)

A pan-genome study of 22 Camellia sinensis genomes provides a clear application of these protocols for interpreting genomic signatures of the JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN (JAZ) gene family, key regulators of stress response [32].

Experimental Protocol: Pan-Genome Based PAV and Selection Analysis

Objective: To characterize the evolutionary dynamics and selection pressures acting on the JAZ gene family across diverse tea plant cultivars.

Materials:

- Genomic Data: 22 high-quality tea plant genome assemblies [32].

- Software: Genome annotation pipelines; OrthoFinder or PlantTribes2 for gene family clustering;

wgdfor Ka/Ks calculation; phylogenetic software (e.g., RAxML).

Procedure & Findings:

- Gene Identification: JAZ genes were identified in each genome using homology-based searches and hidden Markov models (HMMs) of known JAZ domains [32].

- PAV Classification: Genes were classified based on their presence across the pan-genome:

- Core genes: Present in all 22 genomes (e.g., 2 JAZ genes).

- Near-core genes: Present in 20-21 genomes (e.g., 3 JAZ genes).

- Dispensable genes: Present in 2-19 genomes (e.g., 10 JAZ genes).

- Private genes: Unique to a single genome (e.g., 6 JAZ genes) [32].

- Selection Pressure Analysis: Ka/Ks ratios were calculated for each JAZ gene. The study found that

CsJAZ1,CsJAZ8, andCsJAZ9had Ka/Ks > 1, providing evidence of positive selection [32]. - Integration with Expression Data: RNA-seq analysis from four tissues showed that certain JAZ genes (e.g.,

CsJAZ1,CsJAZ9) were consistently highly expressed, linking evolutionary signatures to potential functional importance [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Genomic Analysis of Plant Gene Families

| Item Name | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| High-Quality Reference Genomes | Essential for accurate gene model prediction, synteny analysis, and serving as a baseline for pan-genome studies. Quality is measured by contiguity (N50) and completeness (BUSCO scores) [32]. |

| PlantTribes2 Framework | A scalable, Galaxy-based toolkit for gene family analysis. It classifies sequences into orthologous gene family clusters and performs downstream phylogenetics and duplication analysis [5]. |

| Ensembl Plants Database | A centralized portal providing access to annotated plant genomes, pre-computed gene trees, whole-genome alignments, and gene families, enabling comparative genomics without local computation [36]. |

| GA4GH Passports & Standards | A set of technical and regulatory standards for secure, ethical, and interoperable genomic data sharing across institutions and borders, which is crucial for collaborative large-scale studies [37]. |

| Crypt4GH File Container Standard | A genomics-focused encryption standard for securing genomic data files, protecting participant privacy while allowing controlled access for analysis [38]. |

| Oxford Nanopore/PacBio Sequencers | Long-read sequencing technologies that generate highly contiguous genome assemblies, which are vital for accurately resolving complex gene families and structural variations [34]. |

The How-To Guide: Step-by-Step Workflows and Toolkits for Gene Family Analysis

Genome assembly and annotation are foundational processes in genomics that transform raw DNA sequence data into a biologically meaningful representation of an organism's genetic blueprint. These interrelated processes reconstruct the full DNA sequence into continuous strands and assign functional roles to the identified sequences, enabling researchers to investigate genetic architectures across diverse species [39]. For plant gene family research, high-quality genome assembly and annotation provide the essential framework for comparative analyses, allowing scientists to trace evolutionary relationships, identify lineage-specific adaptations, and understand the functional diversification of gene families such as NLR immune receptors and CNGC ion channels [21] [40]. The advent of advanced sequencing technologies and sophisticated computational tools has dramatically improved our capacity to assemble and annotate even complex plant genomes with high repeat content and polyploidy, establishing these methodologies as critical components in modern plant genomics [39].

Workflow Fundamentals

The journey from raw sequencing data to an annotated genome follows a structured pathway with distinct stages, each with specific quality objectives. The entire process transforms short DNA sequences into chromosome-scale assemblies with comprehensive functional annotation, providing the basis for downstream comparative genomics and gene family analysis.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Assessing Genome Assembly and Annotation Quality

| Metric | Description | Optimal Range/Value |

|---|---|---|

| N50/L50 | Contig or scaffold length at which 50% of the total assembly length is contained in sequences of this size or longer; indicates continuity [39]. | Higher values indicate more continuous assemblies. |

| BUSCO Score | Assessment of assembly completeness based on evolutionarily informed expectations of universal single-copy orthologs [39] [41]. | >90% (Complete) indicates high completeness. |

| Gene Space Completeness | Proportion of expected or conserved genes present in the annotation. | Assessed via orthogroup occupancy in tools like PlantTribes2 [42]. |

| Base-Level Accuracy | Rate of misassembled or incorrect bases; improved through polishing [39]. | QV (Quality Value) > 40 is considered high quality. |

Phase 1: Genome Assembly

Pre-Assembly Considerations

Successful genome assembly begins with careful experimental planning and understanding of genomic properties. Key considerations include:

- DNA Quality: The extraction of high-quality, high-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA is crucial, especially for long-read sequencing technologies [43]. The DNA must be chemically pure and structurally intact, free from contaminants like polysaccharides, polyphenols, or humic acids that can impair library preparation.

- Genomic Properties: Investigate genome size, heterozygosity, ploidy level, repeat content, and GC-content before sequencing [43]. High heterozygosity and repeat content can lead to fragmented assemblies, while extreme GC-content can cause coverage biases in Illumina sequencing.

Data Generation and Preprocessing

Current sequencing strategies often combine multiple technologies to leverage their complementary strengths:

- Long-Read Technologies: Platforms such as PacBio and Oxford Nanopore generate reads spanning several kilobases, which are invaluable for resolving repetitive regions and producing more contiguous assemblies [43] [41].

- Short-Read Technologies: Illumina sequencing provides highly accurate short reads that are useful for polishing long-read assemblies and correcting base-level errors.

- Data Preprocessing: Raw sequencing reads undergo quality control, adapter trimming, and error correction using tools like FastQC and Trimmomatic [39]. This step ensures that only high-quality data proceeds to assembly.

Assembly and Quality Control

Table 2: Common Tools for Genome Assembly and Assessment

| Tool | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Canu | De novo assembly of long reads [39] [41]. | Corrects reads, trims reads, and assembles corrected reads. Suitable for noisy long reads. |

| Flye | De novo assembly of long reads [39] [41]. | Uses repeat graphs for assembly, effective for large genomes. |

| SPAdes | De novo assembly of short reads or hybrid assembly [39]. | Uses de Bruijn graphs, works well with small genomes and hybrid data. |

| Pilon | Assembly improvement/polishing [39]. | Uses alignment information to correct indels, mismatches, and fill gaps. |

| BUSCO | Assembly completeness assessment [39] [41]. | Benchmarks universal single-copy orthologs to assess completeness. |

The assembly process itself involves reconstructing the genome from sequencing reads through either de novo (without a reference) or reference-guided approaches. Assemblers align and merge reads into contigs, which are then ordered and oriented into scaffolds representing chromosomes [39]. The resulting assembly must undergo rigorous quality assessment using metrics like N50 and BUSCO scores [39] to evaluate contiguity and completeness before proceeding to annotation.

Phase 2: Genome Annotation

Structural Annotation

Structural annotation identifies the precise location and structure of genomic features, including genes, exons, introns, and regulatory elements.

- Repeat Masking: The first step involves identifying and masking repetitive elements using tools like RepeatMasker to prevent false-positive gene predictions [39].

- Gene Prediction: This can be achieved through several approaches:

- Ab initio Prediction: Tools like AUGUSTUS and GeneMark use statistical models to identify genes based on sequence patterns such as splice sites, start/stop codons, and codon usage [39].

- Evidence-Based Prediction: This approach incorporates transcriptomic (RNA-seq) or proteomic data to guide and validate gene models, often resulting in more accurate predictions [39] [43].

- Automated Pipelines: Tools such as MAKER and BRAKER3 combine multiple evidence sources and prediction algorithms in a comprehensive workflow to generate consensus structural annotations [39] [41].

Functional Annotation

Functional annotation assigns biological meaning to the structurally annotated genes by comparing them against known sequence databases.

- Homology-Based Assignment: Tools like BLAST are used to align predicted protein sequences to curated databases such as UniProt, identifying homologous relationships and transferring functional information [39] [21].

- Domain and Motif Analysis: Tools including InterProScan and HMMER identify conserved protein domains and motifs by scanning against databases like Pfam and SMART, providing insights into protein function and classification [21] [40].

- Pathway Integration: Functional annotation is further enriched by linking genes to biological pathways using databases like KEGG, placing genes in the context of larger metabolic and regulatory networks [39].

Application to Plant Gene Family Analysis

Identification and Classification of Gene Families

Comparative analysis of gene families begins with the identification of homologous genes across species, which relies heavily on high-quality genome annotations [42] [21]. The standard protocol involves:

- Data Mining: Compile protein sequences from reference genomes of interest [21].

- Homology Search: Use characterized gene family members from a reference species (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana CNGCs or NLRs) as queries in BLASTP searches against target proteomes with a defined significance threshold (e.g., E-value < 1e-5) [21] [40].

- Domain Verification: Confirm candidate genes by checking for defining protein domains using tools like HMMER or Pfam [21]. For CNGCs, this includes both a cNMP-binding domain and an ion transport domain.

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Perform multiple sequence alignment using tools like MAFFT or MUSCLE, followed by phylogenetic tree construction with RAxML or MEGA to determine evolutionary relationships and classify genes into subfamilies [42] [21] [40].

Evolutionary and Functional Analysis

Once gene family members are identified and classified, several analyses elucidate their evolutionary history and functional constraints:

- Analysis of Gene Duplication: Identify tandem and segmental duplication events by analyzing genomic synteny, which reveals mechanisms of gene family expansion [42] [21].

- Calculation of Evolutionary Rates: Estimate synonymous (dN) and non-synonymous (dS) substitution rates to understand selective pressures acting on gene family members [42].

- Identification of Conserved Motifs: Use motif discovery tools like MEME to identify short, conserved sequence patterns that may represent functionally important regions, even in highly diverse gene families like plant NLRs [40].

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Gene Family Analysis

| Category/Tool | Function | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genomes | High-quality annotated genomes for sequence retrieval and homology searches. | Source of query sequences and comparative data (e.g., from PLAZA, Phytozome) [42] [44]. |

| BLAST+ Suite | Local alignment tool for identifying homologous sequences [21] [40]. | Initial identification of candidate gene family members in a proteome. |

| HMMER | Profile hidden Markov model tool for domain searching [40]. | Verification of defining protein domains in candidate genes. |

| MAFFT | Multiple sequence alignment program [40]. | Creating alignments of gene family members for phylogenetic analysis. |

| RAxML | Phylogenetic tree inference using maximum likelihood [40]. | Reconstructing evolutionary relationships among gene family members. |

| MEME Suite | Discovery of conserved sequence motifs [40]. | Identifying short, conserved functional motifs within aligned protein sequences. |

| PlantTribes2 | Gene family analysis pipeline [42]. | Scaffolding, sorting sequences into orthologous groups, and downstream evolutionary analyses. |

Integrated Protocols

Protocol: Phylogenomics of Plant NLR Immune Receptors

This protocol identifies evolutionarily conserved motifs in diverse plant nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NLR) receptors [40].

- Annotation: Annotate NLR genes from proteome datasets using NLRtracker or NLR-Annotator tools.

- Alignment and Phylogeny: Combine sequences with known reference NLRs. Perform multiple sequence alignment with MAFFT and construct a phylogenetic tree with RAxML.

- Sequence Extraction: Extract sequences of a specific NLR subfamily (e.g., CC-NLRs) based on phylogenetic clustering.

- Motif Discovery: Use the MEME suite to identify conserved, ungapped sequence motifs within the extracted protein sequences.

- Validation: Map identified motifs onto the protein alignment and phylogenetic tree to assess conservation patterns and functional relevance.

Protocol: Comparative Analysis of Plant CNGC Gene Family

This protocol details the identification and evolutionary characterization of Cyclic Nucleotide-Gated Channel (CNGC) genes in plants [21].

- Identification and Filtering: Use 20 reference AtCNGC proteins in a BLASTP search against a target plant proteome (E-value < 1e-5). Retain sequences with >75% similarity over ~70% of the query length.

- Domain and Motif Validation: Verify the presence of both cNMP-binding and ion transport domains using HMMER/Pfam. Manually check aligned sequences for the presence of the critical "PBC" and "hinge" regions.

- Phylogenetic Classification: Perform a phylogenetic analysis with reference AtCNGCs using MEGA software. Classify and name new CNGC genes based on their clustering with established Arabidopsis groups.

- Evolutionary Analysis: Analyze gene structures (exon-intron patterns), calculate non-synonymous/synonymous substitution rates (dN/dS), and investigate syntenic relationships to infer duplication events and evolutionary history.

A robust workflow from genome assembly to functional annotation is fundamental for comparative plant genomics. The integration of long-read sequencing technologies, advanced computational tools, and standardized protocols enables the generation of high-quality genomic resources. These resources, in turn, empower detailed investigations into the evolution and function of plant gene families. As sequencing technologies continue to advance and computational methods become more sophisticated, these workflows will provide even deeper insights into the genetic basis of plant biology, with significant implications for crop improvement, evolutionary studies, and understanding plant-environment interactions.

The identification and classification of gene families is a cornerstone of modern plant genomics, enabling researchers to decipher evolutionary relationships, infer gene function, and identify genetic patterns underlying key agronomic traits [45]. As sequencing technologies continue to produce vast amounts of genomic data, the challenge has shifted from data generation to meaningful biological interpretation [5] [46]. This protocol details a robust methodology for gene family identification that integrates multiple complementary bioinformatics tools—BLAST for sequence similarity searches, HMMER for profile-based detection, and conserved domain databases (Pfam, SPARCLE) for structural validation. When applied within the context of plant comparative genomics, this integrated approach significantly enhances detection sensitivity and reduces false positives compared to single-method pipelines, particularly for distantly related homologs and complex gene families [47] [45] [48].

Table 1: Core Bioinformatics Tools for Gene Family Identification

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Similarity Search | BLASTP, BLASTX | Identify sequences with significant similarity to query | Fast, widely understood, good for initial screening |

| Profile-Based Search | HMMER | Detect remote homologs using hidden Markov models | Superior for detecting divergent sequences |

| Conserved Domain Databases | Pfam, SPARCLE | Identify and classify protein domains | Provides functional and evolutionary context |

| Integrated Pipelines | PlantTribes2, geneHummus | Combine multiple methods for comprehensive analysis | Automated, reproducible, scalable |

Materials

Bioinformatics Software and Databases

The following software tools and databases are essential for implementing the gene identification protocols described in this application note. Installation instructions for all tools are available on their respective official websites.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Category | Name | Function/Application | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Search Tools | NCBI BLAST+ Suite | Local sequence similarity searches | https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |

| HMMER | Profile hidden Markov model searches | http://hmmer.org | |

| Domain Databases | Pfam | Protein family and domain classification | http://pfam.xfam.org |

| SPARCLE | Protein architecture and subfamily classification | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sparcle | |

| Integrated Environments | PlantTribes2 | Scalable gene family analysis framework | https://github.com/dePamela/PlantTribes2 |

| geneHummus | R package for automated gene family identification | https://github.com/halleybug/genehummus | |

| Reference Data | RefSeq | Curated non-redundant reference sequences | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq |

Computational Requirements

For optimal performance, the following computational resources are recommended:

- Memory: Minimum 16 GB RAM (64+ GB recommended for genome-scale analyses)

- Storage: High-speed SSD with sufficient capacity for large sequence databases and intermediate files

- Processing: Multi-core processors (16+ cores) significantly accelerate HMMER and alignment steps

Methods

Integrated Workflow for Comprehensive Gene Family Identification

The following integrated methodology leverages the complementary strengths of similarity-based, profile-based, and domain-based identification approaches to maximize the detection of true gene family members while minimizing false positives.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

BLAST-Based Gene Identification

BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) provides a fundamental method for identifying sequences with significant similarity to known query sequences.

Procedure:

- Query Selection: Select one or more well-characterized protein sequences representing the gene family of interest. For plant studies, consider including queries from diverse species (e.g., Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa) to maximize detection sensitivity [45].

- Database Preparation: Format target proteome or genome databases using

makeblastdbfor efficient searching. - BLAST Execution: Perform BLASTP or TBLASTN searches with the following optimized parameters:

- Result Filtering: Retain hits with E-values < 1e-5 and sequence identity >30% for further analysis. For large gene families, consider more stringent thresholds (E-value < 1e-10) to reduce false positives [45].

HMMER and Pfam Domain Analysis

Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) provide superior sensitivity for detecting evolutionarily divergent members of gene families that may be missed by BLAST alone [49] [48].

Procedure:

- Domain Identification: Identify characteristic protein domains for your gene family using Pfam (https://pfam.xfam.org). For example, the ARF gene family is characterized by B3 (PF02362), AUX_RESP (PF06507), and AUX/IAA (PF02309) domains [47].

- HMM Profile Acquisition: Download pre-built HMM profiles from Pfam or build custom profiles from multiple sequence alignments of known family members using

hmmbuild. - HMMER Search: Execute profile searches against your target database:

- Domain Architecture Validation: Verify that candidate sequences contain the complete complement of domains expected for the gene family using InterProScan or similar tools.

SPARCLE Database Querying

The SPARCLE database provides pre-computed protein architecture information that can dramatically accelerate gene family identification, particularly for well-characterized families [47].

Procedure:

- Architecture Definition: Determine the specific domain architecture that defines your gene family of interest.

- SPARCLE Query: Access SPARCLE through the NCBI interface or programmatically via E-utilities to retrieve proteins matching your target architecture.

- Taxonomic Filtering: Restrict results to relevant taxonomic groups (e.g., Viridiplantae for plant-specific studies).

- Sequence Retrieval: Download protein sequences and corresponding accessions for architectures matching your gene family definition.

Manual Curation and Validation

Manual curation between computational steps significantly enhances the validity of gene family identification by allowing for the detection of problematic sequences that might be retained in fully automated pipelines [45].

Procedure:

- Sequence Alignment: Perform multiple sequence alignment of candidate genes using MAFFT or MUSCLE:

- Phylogenetic Analysis: Construct preliminary phylogenetic trees using maximum likelihood or Bayesian methods:

- Visual Inspection: Manually inspect alignments and tree topology to verify that candidate sequences group with known members of the gene family and display characteristic conserved residues.

- Final Membership Determination: Based on all available evidence, make a final determination of gene family membership.

Case Study: ARF Gene Family Identification in Legumes

To illustrate the practical application of these methods, we describe a case study identifying auxin response factor (ARF) genes in legume species, adapting the approach implemented in the geneHummus package [47].

Experimental Protocol:

- Domain Definition: The ARF gene family was defined by the presence of B3 DNA binding domain (Pfam 02362), AUX_RESP (Pfam 06507), and AUX/IAA (Pfam 02309) domains.

- SPARCLE Query: The SPARCLE database was queried for proteins containing the complete ARF domain architecture, filtered for Fabaceae taxonomy IDs.

- Sequence Retrieval: Protein accessions were retrieved from the RefSeq database and converted to amino acid sequences.

- Validation: The pipeline identified 24 ARF proteins in the chickpea (Cicer arietinum) genome, reproducing previous manual annotations but completing the analysis in under 6 minutes compared to 6 months for manual approaches [47].

Table 3: ARF Gene Family Members Identified in Legume Species

| Species | Genome Version | ARF Proteins Identified | Gene Loci | Analysis Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cicer arietinum (Chickpea) | v2.0 | 24 | 24 | <6 minutes |

| Arachis duranensis | v1.0 | 31 | ~18 | <6 minutes |

| Arachis ipaensis | v1.0 | 29 | ~17 | <6 minutes |

| Medicago truncatula | Mt4.0v1 | 27 | ~22 | <6 minutes |

| Glycine max (Soybean) | Wm82.a2.v1 | 55 | ~41 | <6 minutes |

Discussion

Comparative Performance of Gene Identification Methods

Each gene identification method offers distinct advantages and limitations that make them suitable for different research scenarios. Understanding these trade-offs is essential for selecting appropriate methodologies for specific research questions.

Table 4: Method Comparison for Gene Family Identification

| Method | Sensitivity | Specificity | Speed | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLAST | Moderate | Moderate | Fast | Initial screening, closely related sequences |

| HMMER/Pfam | High | High | Moderate | Divergent sequences, domain-based families |

| SPARCLE | High for defined architectures | Very High | Very Fast | Well-characterized families with defined architectures |

| Manual Pipeline | Highest | Highest | Slow | Critical analyses requiring high confidence |

| Integrated Approach | Highest | Highest | Moderate | Comprehensive studies requiring maximal detection |

Applications in Plant Comparative Genomics

The integration of these gene identification methods enables powerful applications in plant comparative genomics, including:

Evolutionary History Reconstruction: Gene family analysis can reveal lineage-specific expansions and contractions that illuminate evolutionary adaptations. For example, the PlantTribes2 framework has been used to infer large-scale duplication events and phylogenetic relationships across diverse plant lineages [5].

Functional Prediction: Identification of orthologs in non-model species allows for functional inference based on characterized genes in model systems, though caution is needed as orthologs in distantly related species may not share identical functions [45].

Crop Improvement: Comparative analysis of gene families underlying agronomic traits in related species can identify candidates for breeding programs. The application of PlantTribes2 to Rosaceae species exemplifies this approach for economically important plants [5] [42].

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common challenges in gene family identification and recommended solutions:

- High False Positive Rates: Implement stricter E-value thresholds (1e-10 instead of 1e-5) and require complete domain architectures characteristic of the gene family.

- Missing Divergent Homologs: Combine BLAST searches with HMMER profiling and consider more sensitive alignment modes in HMMER.

- Inconsistent Domain Boundaries: Manually verify domain boundaries using multiple tools (Pfam, SMART, CDD) and consider known structures from resources like ECOD.

- Computational Resource Limitations: For large genomes, consider cloud computing resources or optimized implementations like HMMER3, which provides approximately 100-fold speed improvement over previous versions [50].