Clothomics: Unraveling Ancient Mysteries Through Biomolecular Science

A new scientific field is transforming dusty archaeological fragments into vivid pages from human history.

Article Navigation

Key Insights

- Precise species identification

- Reveals ancient trade networks

- Validates historical accounts

- Shows resource management patterns

Introduction: More Than Just Ancient Threads

When archaeologists uncover fragments of ancient cloth, they're not just finding crumbling textiles—they're discovering hidden chapters of human history. For centuries, researchers could only study these materials through visual examination and microscopes, limited to what the eye could see. Now, a revolutionary scientific field called "clothomics" is transforming our understanding of archaeological textiles, leather, and furs by reading the biomolecular stories they contain.

By applying advanced genomic and proteomic analyses to ancient cloth, scientists are answering questions that were previously unanswerable: What animals provided the materials for Viking Age clothing? How did ancient trade routes influence textile production? What can a 5,000-year-old mummy's wardrobe tell us about his society?

Clothomics represents the convergence of cutting-edge laboratory science and traditional archaeology, creating an interdisciplinary field that extracts unprecedented information from the most delicate of ancient materials 1 . As we'll explore, this emerging discipline is rewriting history one thread at a time.

Traditional Limitations

Visual examination alone couldn't reveal the full story of ancient textiles, missing crucial biomolecular evidence.

New Possibilities

Biomolecular analysis now allows precise identification of animal species and manufacturing techniques.

What is Clothomics? The Science of Reading Ancient Fibers

Clothomics applies diverse omics methodologies—including genomics, proteomics, lipidomics, and metabolomics—to archaeological cloth research 1 . The term deliberately echoes fields like genomics, reflecting its comprehensive approach to analyzing all recoverable biomolecules from ancient textiles and animal skins.

Why Cloth Matters in Archaeology

Cloth-type materials, including textiles, leather, and furs, were fundamental to all human societies, serving far more than just clothing needs. They were used for shelter, storage, transportation (like boat sails), protection (shields), and as cultural markers 1 . Despite their importance, cloth has been historically overlooked in archaeological interpretation due to poor preservation and underappreciation of its significance 1 .

The central goal of clothomics is to understand the entire chaîne opératoire—the operational sequence from raw material procurement to finished product—revealing insights about technology, trade, animal management, and cultural choices 1 .

The Biomolecular Revolution in Cloth Research

Traditional morphological studies of ancient cloth face significant limitations:

Degradation

From burial conditions and manufacturing processes 1

Reference Gaps

Absence of comprehensive collections for comparison 1

Methodology Issues

Lack of standardized, objective identification methods 1

Clothomics overcomes these challenges by analyzing the fundamental building blocks of life that persist in archaeological materials—proteins and DNA—offering precise species identification and new insights into ancient manufacturing practices 1 .

Clothomics in Action: The Viking Age Fur Project

A compelling example of clothomics research comes from a recent study presented at the 42nd Interdisciplinary Viking Symposium, titled "A clothomics approach to Viking Age fur" 4 . This project exemplifies how biomolecular analysis can transform our understanding of historical clothing and resource use.

Methodology: Step-by-Step Scientific Process

The research followed a systematic approach to extract maximum information from delicate archaeological fur samples:

Sample Selection

Researchers obtained fur fragments from Viking Age archaeological sites, prioritizing materials from secure contextual and dating information.

Non-Destructive Preliminary Analysis

Initial visual and microscopic examination documented weave structures, fiber characteristics, and preservation state before biomolecular sampling.

Minimally Invasive Sampling

Tiny samples (often less than 1mg) were carefully collected for proteomic analysis using clean techniques to prevent contamination.

Protein Extraction and Preparation

Proteins were extracted from the samples and digested into peptides using enzymatic processing, making them suitable for mass spectrometry analysis.

LC-MS/MS Analysis

Liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry separated and fragmented the peptide mixtures, generating spectral data for identification.

Database Searching

The mass spectra were compared against protein sequence databases to identify specific animal species based on characteristic peptide patterns.

Results and Significance: Rewriting Viking History

The Viking Age fur study yielded fascinating insights into resource use and cultural practices:

| Animal Species | Type of Garment/Accessory | Historical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Beaver | Fur clothing | Wild animal exploitation beyond subsistence |

| Various seal species | Accessories, clothing elements | Marine resource utilization |

| Domesticated animals (cattle, sheep) | Leather accessories | Differential use of domesticated vs. wild animals |

The analysis revealed that wild animals were exclusively used for fur clothing, while domesticated animals provided leather for accessories 1 4 . This patterning suggests that Vikings made deliberate choices about materials based on functionality, availability, and possibly cultural preferences or status display.

Interestingly, these findings align with earlier clothomics research showing similar patterns in other regions. A study of 109 samples from Bronze Age-Iron Age China also found textiles were mainly sheep wool, while furs or pelts were mostly goat 1 . Such parallels suggest widespread cross-cultural practices in animal resource management for cloth production.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Methods

Clothomics research relies on specialized reagents and analytical techniques to extract and identify ancient biomolecules. Here are the key components of the clothomics toolkit:

| Reagent/Method | Function in Clothomics | Specific Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Proteomics reagents (trypsin, extraction buffers) | Digest proteins into identifiable peptides | Species identification through characteristic protein fragments |

| LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry) | Separate and analyze protein mixtures | Untargeted identification of thousands of peptides in a single run |

| ZooMS (Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry) | Collagen peptide mass fingerprinting | Rapid screening of animal species from collagen-based materials |

| DNA extraction kits | Isolate trace ancient DNA | Genetic analysis of animal sources, despite challenges with degradation |

| GC-MS (Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry) | Analyze lipid and metabolic profiles | Identification of paint binders, preservatives, or accidental contaminants |

Each tool addresses specific challenges in ancient cloth analysis. For instance, proteomics has proven particularly valuable because proteins often survive better than DNA in archaeological textiles, especially those subjected to manufacturing processes like tanning that degrade genetic material 1 . Early attempts to retrieve ancient DNA from cloth showed significant difficulties due to degradation during tanning processes, making proteomics a more reliable approach for many applications 1 .

DNA Analysis

Challenges:

- Degradation during manufacturing

- Contamination risks

- Limited survival in some conditions

Best for: Well-preserved materials with minimal processing

Proteomics

Advantages:

- Better survival in processed materials

- Species-specific identification

- More resilient to degradation

Best for: Most archaeological textiles and leather

Remarkable Discoveries: Clothomics Rewriting History

The application of clothomics has led to several groundbreaking discoveries that have transformed our understanding of past societies:

| Civilization/Context | Key Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Scythian populations | Human skin used to cover quivers | Confirms Herodotus' historical accounts of using defeated enemies' skin |

| Precolumbian Peru | Mountain Viscacha fibers in textiles (300 BCE-100 CE) | Reveals unexpected trade networks with highland regions |

| Ötzi the Iceman | Multiple animal sources (bear, deer, goat, cattle) | Demonstrates sophisticated resource use 5,300 years ago |

| Ancient Egypt | Gazelle skin identified in artifacts | Illuminates hunting practices and material selection |

| Historical Arctic | Arctic fox, hare, wolverine species | Shows environmental adaptation in extreme climates |

One of the most striking discoveries came from Scythian sites, where clothomics analysis identified human skin used to cover quivers, confirming claims by the ancient historian Herodotus that Scythians made materials from the skin of defeated enemies 1 . This demonstrates how clothomics can validate—or challenge—historical accounts through physical evidence.

Similarly, the analysis of Ötzi the Iceman's clothing has revealed surprising complexity. Proteomic analyses identified multiple animal sources in his different garments: his coat was made of sheep, his legging also of sheep, his moccasins of cattle, and other items incorporated goat, brown bear, chamois, red deer, and canid 1 . This diversity suggests sophisticated knowledge of material properties and resource availability in his Alpine environment.

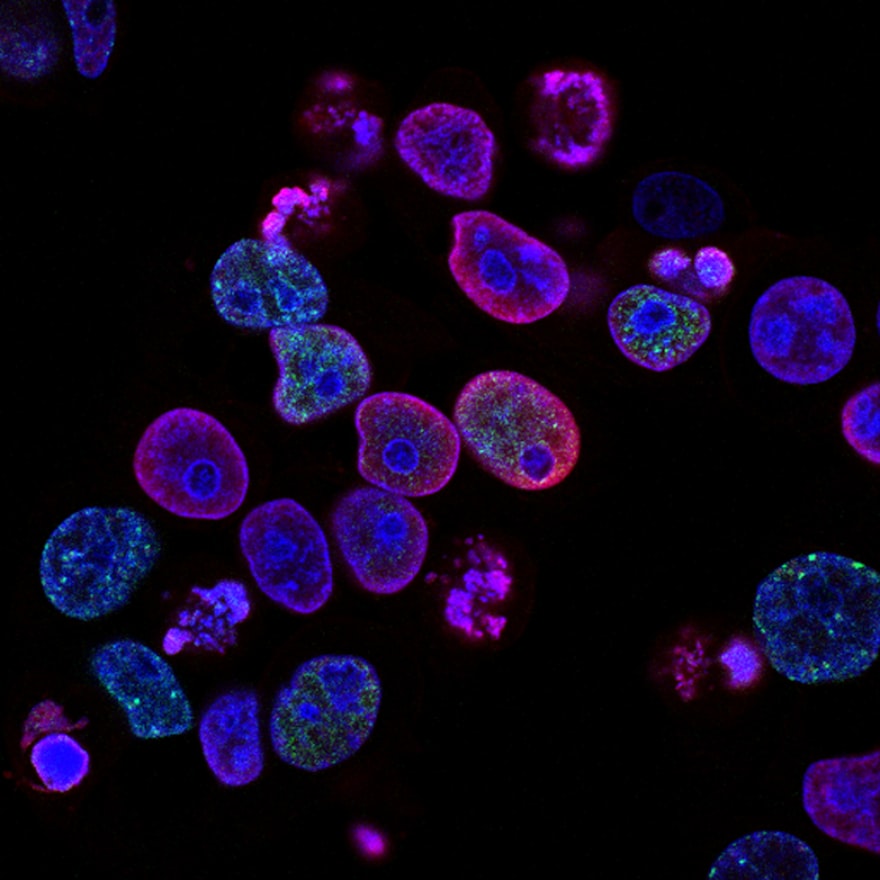

Ancient textile fragments reveal biomolecular stories of past civilizations.

Timeline of Key Clothomics Discoveries

2018

Scythian Human Skin Confirmation

Validation of Herodotus' accounts through biomolecular evidence 1

Future Directions: The Expanding Horizon of Clothomics

As clothomics matures, several promising developments are emerging:

Technical Advancements

Researchers are developing methods to recover and detect even more degraded biomolecules, expanding the temporal and geographical range of clothomics applications 1 .

Data Sharing and Collaboration

The field is becoming more inclusive through data sharing initiatives and participatory science, accelerating methodological improvements 1 .

Plant Fiber Applications

While current research focuses heavily on animal-based materials, future work aims to extend these techniques to plant fibers like flax, hemp, and cotton 1 .

Multi-omics Integration

Combining proteomics with genomics, lipidomics, and other approaches provides a more comprehensive understanding of ancient materials 7 .

Looking Ahead

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with clothomics data promises to accelerate pattern recognition and interpretation, potentially revealing connections that would otherwise remain hidden in complex datasets.

Conclusion: Weaving Together Past and Future

Clothomics represents more than just technical innovation—it's a fundamental shift in how we extract stories from ancient materials. By reading the molecular messages preserved in textiles, leather, and furs, we're recovering lost knowledge about human ingenuity, resource management, and cultural expression.

As this field develops, we can anticipate even more startling revelations about our shared past. The humble textile fragment, once considered barely worthy of collection, now stands as a rich repository of historical information, waiting for its molecular story to be told.

The true power of clothomics lies in its ability to connect disciplines—bringing together archaeologists, conservators, geneticists, and protein scientists to weave a more complete tapestry of human history, one thread at a time 1 .

Interdisciplinary Science

Clothomics bridges archaeology with cutting-edge laboratory techniques.