Closing the Carbon Loop: Advanced Life Support Systems for Terrestrial and Space Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of carbon loop closure technologies in advanced life support systems, exploring their foundational principles, methodological applications, and optimization strategies.

Closing the Carbon Loop: Advanced Life Support Systems for Terrestrial and Space Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of carbon loop closure technologies in advanced life support systems, exploring their foundational principles, methodological applications, and optimization strategies. Tailored for researchers and scientists, it bridges knowledge from space exploration—where systems like the Advanced Closed Loop System (ACLS) and Next Generation Life Support (NGLS) demonstrate high-fidelity carbon recycling—with terrestrial ecosystem management and biomedical research. We examine carbon concentration, oxygen generation, and bioregenerative methods, address troubleshooting and system reliability, and validate performance through comparative analysis and modeling. The synthesis offers critical insights for developing closed-loop systems that ensure sustainability in isolated environments, from spacecraft to clinical settings, and informs future innovations in carbon-neutral technologies.

The Principles and Urgency of Carbon Loop Closure

Defining Carbon Loop Closure in Controlled Environments

Carbon loop closure represents a critical paradigm in environmental control and life support systems (ECLSS) for advanced human exploration and terrestrial applications. This technical framework involves the continuous recycling of carbon dioxide through capture, concentration, and conversion processes to regenerate oxygen and produce valuable resources. As research advances toward completely closed habitats for deep space missions, precise carbon loop management has become essential for reducing resupply requirements and enabling long-duration human presence in isolated environments. This whitepaper examines the core principles, technological implementations, and experimental methodologies defining carbon loop closure, with particular emphasis on integrated systems currently demonstrating operational efficacy in controlled settings.

Carbon loop closure encompasses the engineered processes that capture, manage, and convert carbon dioxide into usable resources within controlled environments. In advanced life support systems research, this concept extends beyond mere carbon dioxide removal to encompass comprehensive carbon cycling that minimizes external inputs and maximizes resource regeneration. The fundamental objective is to create a balanced mass exchange where carbon emitted through human respiration and other processes is continuously recycled rather than vented as waste [1] [2].

In practical terms, carbon loop closure represents a critical path toward sustainable long-duration space missions, where resupply from Earth becomes progressively more challenging and eventually impossible. The European Space Agency's Advanced Closed Loop System (ACLS) demonstrates this principle by recycling carbon dioxide from cabin air into breathable oxygen, thereby reducing water resupply requirements by approximately 400 liters annually [1]. Similarly, terrestrial applications are emerging in industrial carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) frameworks, where point-source carbon emissions are converted into valuable products including fuels, fertilizers, and construction materials [3] [4].

Core Principles and System Components

Fundamental Operational Principles

Carbon loop systems operate on three fundamental principles: concentration, conversion, and regeneration. The concentration phase involves selective capture of CO₂ from atmospheric mixtures, typically achieved through chemical adsorption processes. The conversion stage transforms concentrated CO₂ into chemically reduced forms through various catalytic pathways. Finally, regeneration completes the loop by returning useful products to the habitat environment while replenishing any consumables required for the concentration phase [1] [2].

Mass balance precision represents another critical principle, as system stability requires careful matching of CO₂ production rates with processing capacity. In the ISS ACLS system, this balance is maintained through continuous monitoring and adjustment of the Carbon dioxide Concentration Assembly (CCA) operation to match crew metabolic output [2]. Systems must be designed with sufficient buffer capacity to accommodate fluctuations in crew size and activity levels while maintaining cabin CO₂ within acceptable limits for human health and performance.

Key System Components

Closed-loop carbon systems integrate several specialized components that function in concert to maintain continuous operation:

Carbon Concentration Assembly (CCA): Utilizes amine-functionalized adsorbent materials to selectively remove CO₂ from cabin atmosphere. The ACLS system employs specialized amine-developed beads that exhibit high CO₂ adsorption capacity and cycling stability [1]. Steam regeneration then releases concentrated CO₂ for subsequent processing while restoring adsorption capacity.

Carbon Dioxide Reprocessing Assembly (CRA): Implements Sabatier reaction chemistry where concentrated CO₂ reacts with hydrogen over a catalyst (typically ruthenium on alumina) to produce methane and water. The standard reaction (CO₂ + 4H₂ → CH₄ + 2H₂O) achieves approximately 80-90% conversion efficiency at operational temperatures of 300-400°C [1] [2].

Oxygen Generation Assembly (OGA): Utilizes proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolysis to split water recovered from the Sabatier reactor into oxygen and hydrogen. The oxygen is returned to cabin atmosphere for crew consumption, while hydrogen is recycled to the Sabatier reactor [1].

Table: Performance Metrics of ACLS System Components [1] [2]

| Component | Function | Efficiency | Output Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Concentration Assembly (CCA) | CO₂ capture from cabin air | >90% CO₂ removal | Matches crew metabolic output |

| Carbon Dioxide Reprocessing (CRA) | Sabatier conversion of CO₂ to CH₄ and H₂O | 80-90% conversion | Water production for 50% O₂ needs |

| Oxygen Generation Assembly (OGA) | Electrolysis of water to O₂ and H₂ | >99% purity O₂ | Supports 3 crew members |

Technological Implementation Frameworks

Current Space-Based Systems

The Advanced Closed Loop System (ACLS) represents the most technologically mature implementation of carbon loop closure in operational use. Deployed on the International Space Station, ACLS operates as a standardized 2-meter rack within the US Destiny module, integrating all necessary components for continuous carbon recycling [1]. The system demonstrates a partially closed loop where approximately 50% of recovered CO₂ is ultimately converted back to oxygen, with the remainder vented as methane due to stoichiometric limitations of the Sabatier process [1] [2].

The ACLS operational concept employs a sequential processing approach where cabin air first passes through the CCA for CO₂ concentration, then the concentrated CO₂ moves to the CRA (Sabatier reactor) where it combines with hydrogen from the OGA. The resulting water is purified and transferred to the OGA for electrolysis, completing the oxygen regeneration cycle. This integrated approach reduces the Station's water resupply requirements by approximately 400 liters annually while maintaining cabin CO₂ at safe levels without consumable cartridges [1].

Terrestrial Methodologies and Industrial Parallels

Terrestrial carbon closure strategies employ similar physicochemical principles but with expanded product outputs, particularly within carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) frameworks. India's research initiatives focus on point-source capture from industrial sectors (power, cement, steel) representing approximately 80% of the country's 2,600 Mt annual CO₂ emissions [3]. Conversion pathways emphasize economic viability through production of high-value marketable products including fuels, fertilizers, aggregates, and construction materials that support circular carbon economies.

Industrial carbon conversion employs multiple catalytic pathways, each with distinct operational parameters and output profiles. Thermocatalysis utilizes heat and pressure (700-1000°C) with hydrogen to produce alcohols like methanol and ethanol. Electrochemical conversion employs renewable electricity for carbon-neutral operation at ambient conditions. Photocatalysis mimics natural photosynthesis using light energy, while biocatalysis leverages enzymatic or microbial processes for specific chemical production [4].

Table: Comparative Analysis of CO₂ Conversion Technologies [4]

| Conversion Method | Operating Conditions | Primary Products | Technology Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermocatalysis | 700-1000°C, high pressure | Methanol, ethanol, methane | Commercial demonstration |

| Electrochemical Conversion | Ambient, electrical input | Carbon monoxide, formic acid | Pilot scale |

| Photocatalysis | Ambient, light input | Hydrogen, syngas | Laboratory research |

| Biocatalysis | Ambient, biological | Ethanol, ethylene | Early commercial |

| Carbon Mineralization | Ambient to moderate | Carbonates, building materials | Commercial operation |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

System Performance Validation

Research-grade evaluation of carbon closure systems requires rigorous experimental protocols to quantify performance across operational parameters. The ACLS validation approach implemented on the ISS involves continuous monitoring of key performance indicators over extended durations (typically 1 year of operation within a 2-year demonstration window) [2]. Standardized measurement protocols include:

CO₂ Concentration Efficiency: Measured via infrared spectroscopy at CCA inlet and outlet ports, calculating removal efficiency as [(Cin - Cout)/C_in] × 100%, with target performance >90% under nominal crew metabolic loads [2].

Sabatier Reactor Conversion Rate: Quantified through gas chromatography of input (CO₂ + H₂) and output (CH₄ + H₂O + unreacted gases) streams, with conversion efficiency calculated based on CO₂ depletion. Optimal performance achieves 80-90% conversion at 300-400°C with ruthenium catalysts [1] [2].

Oxygen Generation Purity: Monitored via mass spectrometry of OGA output stream, with requirement for >99% oxygen purity for crew life support applications [1].

System Mass Balance: Continuous tracking of input and output mass flows (CO₂, H₂, CH₄, H₂O, O₂) to verify closure metrics and identify any accumulation losses or byproducts affecting long-term operation [2].

Material Testing and Catalyst Evaluation

Catalyst development represents a critical research domain for improving carbon conversion efficiency and longevity. Standard experimental protocols for novel catalyst evaluation include:

Accelerated Lifetime Testing: Continuous operation under simulated feed conditions with periodic performance assessment to determine degradation rates and operational lifespan. The ACLS amine sorbent materials underwent >10,000 adsorption-desorption cycles during ground testing prior to flight approval [2].

Contaminant Tolerance Assessment: Introduction of potential atmospheric contaminants (siloxanes, hydrocarbons, etc.) at measured concentrations to quantify performance impacts and develop mitigation strategies for closed environments [2].

Surface Characterization: Pre- and post-testing analysis using SEM, XRD, and BET surface area measurements to correlate structural changes with performance degradation and identify failure mechanisms.

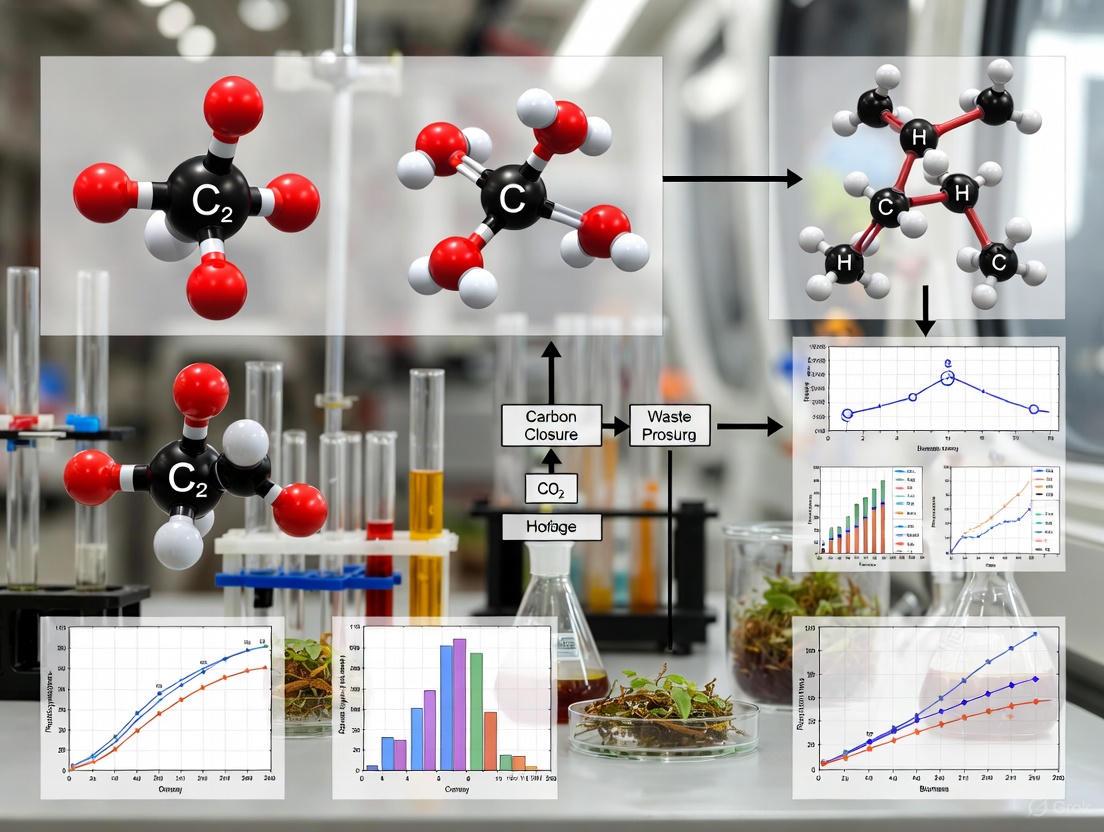

Visualization of System Processes

ACLS Carbon Loop Closure Process

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table: Essential Research Materials for Carbon Loop Closure Experiments

| Material/Component | Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Amine-functionalized Adsorbents | CO₂ capture from air | Carbon concentration subsystems |

| Ruthenium on Alumina Catalyst | Sabatier reaction facilitation | CO₂ to CH₄ conversion |

| Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) | Water electrolysis | Oxygen generation from water |

| Zeolite Molecular Sieves | Gas separation and drying | Process air purification |

| Nickel-based Catalysts | Alternative Sabatier medium | Lower-cost CO₂ conversion |

| Solid Oxide Electrolysis Cells | High-temperature electrolysis | Efficient oxygen generation |

| Calcium Oxide Sorbents | Carbon mineralization | CO₂ to carbonate conversion |

Carbon loop closure represents a critical capability for advancing human presence in isolated environments, with demonstrated efficacy in operational space systems and emerging applications in terrestrial carbon management. The integration of concentration, conversion, and regeneration technologies enables increasingly closed systems that reduce resource dependencies and support sustainable long-duration operations. Current implementations like the ACLS demonstrate technical feasibility while highlighting areas for further development, particularly in closing the methane venting gap and improving system energy efficiency.

Future research priorities include developing alternative catalytic pathways with improved stoichiometry, integrating biological processing components for food production, and advancing system autonomy for deep space missions where ground support is limited. The continuing evolution of carbon loop closure technologies will play a decisive role in enabling human exploration beyond low-Earth orbit while contributing valuable spinoff technologies for terrestrial carbon management challenges.

The Critical Role in Long-Duration Space Missions

Long-duration space missions beyond low-Earth orbit necessitate a paradigm shift from open-loop to closed-loop Environmental Control and Life Support Systems (ECLSS). The critical role of closing the carbon loop is paramount for mission sustainability, drastically reducing resupply mass and enabling human exploration of deep space. This whitepaper examines the core technologies for carbon dioxide (CO₂) concentration, reduction, and oxygen generation, presenting quantitative performance data, detailed operational methodologies, and system-level integration strategies. Framed within the broader context of achieving full carbon loop closure, this analysis provides researchers and life support scientists with the technical framework for advancing regenerative life support systems for lunar Gateway, Mars transit, and sustained planetary habitation.

In the inhospitable environment of space, sustaining human life is a complex challenge of resource management. Open-loop systems, which rely on regular resupply of consumables like water and oxygen from Earth, are logistically and economically infeasible for missions to the Moon, Mars, and beyond. The cornerstone of sustainable long-duration missions is the development of robust ECLSS that progressively close the loops on air, water, and waste [5]. Central to this challenge is the carbon loop, which revolves around the astronaut's metabolic function of consuming oxygen (O₂) and producing CO₂.

Closing the carbon loop involves capturing and processing exhaled CO₂ to recover oxygen, thereby creating a regenerative cycle. The European Space Agency's (ESA) Advanced Closed Loop System (ACLS) represents a significant leap forward, demonstrating a functional rack on the International Space Station (ISS) that recycles carbon dioxide into oxygen [1]. Similarly, NASA's expertise encompasses the research, development, and testing of closed-loop technologies for carbon dioxide removal, reduction, and oxygen generation [6]. This paper deconstructs the critical subsystems involved, their performance parameters, and their integrated operation within the broader goal of full carbon loop closure.

Core Subsystems and Quantitative Analysis

A closed-loop carbon system comprises three primary technological assemblies: the concentration of CO₂ from cabin air, its chemical reduction, and the subsequent generation of oxygen. The performance data of these subsystems directly dictates the overall efficiency and degree of loop closure achievable.

Carbon Dioxide Concentration Assembly (CCA)

The CCA is the first critical step, responsible for removing CO₂ from the cabin atmosphere to maintain acceptable levels for crew health and preparing it for downstream processing. The ACLS utilizes a solid amine-based chemical process, trapping CO₂ from the air as it passes through small beads composed of a unique amine developed by ESA [1]. The concentrated CO₂ is then released using steam for further processing.

Carbon Dioxide Reprocessing Assembly (CRA/Sabatier Reactor)

The CRA performs the key function of carbon dioxide reduction. The most common and flight-proven method is the Sabatier process, which converts CO₂ into water and methane. In this reaction, hydrogen and carbon dioxide react over a catalyst, typically nickel or ruthenium, at elevated temperatures (200-400°C) to form water (H₂O) and methane (CH₄) [1]. The water is condensed, separated, and fed to the oxygen generation assembly. The methane is typically vented to space, which represents a loss of hydrogen and explains why current systems like the ACLS recover only about 50% of the oxygen from the processed CO₂ [1].

Oxygen Generation Assembly (OGA)

The OGA completes the loop by electrolyzing water to produce oxygen for the crew and hydrogen for the Sabatier reactor. The OGA is an electrolyser that splits water into oxygen and hydrogen using an electrical current [1]. The oxygen is introduced into the cabin for the crew to breathe, while the hydrogen is directed back to the Sabatier reactor to facilitate the reduction of more CO₂.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of the Advanced Closed Loop System (ACLS)

| Parameter | Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Production Capacity | Supports 3 astronauts [1] | Demonstrates capability to support a significant portion of a standard ISS crew. |

| Water Savings | ~400 liters per year [1] | Quantifies the direct reduction in resupply mass from Earth. |

| CO₂ Recovery Rate | 50% [1] | Highlights current system limitation due to methane venting. |

| Physical Dimensions | 2 m high, 1 m wide, 85.9 cm deep [1] | Informs mass and volume constraints for vehicle integration. |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Carbon Loop Closure Technologies

| Technology | Process | Inputs | Outputs | Loop Closure Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sabatier Reactor | CO₂ + 4H₂ → CH₄ + 2H₂O (over catalyst) [1] | Carbon Dioxide, Hydrogen | Water, Methane | Partial (50% O₂ recovery) [1] |

| Bosch Reaction | CO₂ + 2H₂ → C + 2H₂O | Carbon Dioxide, Hydrogen | Water, Solid Carbon | Potentially Full (no methane vented) |

| Advanced Sabatier | Sabatier with methane pyrolysis (CH₄ → C + 2H₂) | Carbon Dioxide | Water, Solid Carbon, Hydrogen | Potentially Full (hydrogen recycled) |

Experimental Protocols and System Workflows

For researchers developing and testing these subsystems, standardized methodologies are crucial for benchmarking performance and ensuring reliability.

Protocol for Solid Amine CO₂ Sorption/Desorption Cycling

This protocol details the process for evaluating and operating a solid amine CO₂ concentrator.

- Objective: To characterize the efficiency and capacity of a solid amine sorbent for concentrating CO₂ from a simulated cabin atmosphere.

- Materials:

- Test chamber packed with solid amine sorbent beads.

- Gas mixing system to simulate cabin air (∼0.5-1% CO₂, 21% O₂, 78% N₂).

- Steam generator for desorption phase.

- Mass Flow Controllers (MFCs) for precise gas handling.

- CO₂, O₂, and humidity sensors at inlet and outlet.

- Data acquisition system.

- Procedure:

- Sorption Phase: Condition the sorbent bed. Flow the simulated cabin air through the sorbent bed at a specified rate and temperature (e.g., 25-30°C). Monitor the outlet CO₂ concentration until breakthrough is detected, indicating sorbent saturation.

- Desorption Phase: Isolate the bed from the cabin air stream. Heat the bed internally or externally while introducing a controlled flow of steam. The steam lowers the partial pressure of CO₂ and provides the thermal energy required to break the amine-CO₂ bond, releasing a concentrated stream of CO₂.

- Collection & Measurement: Channel the desorbed gas stream through a condenser to remove water. Measure the volume and concentration of the dry, concentrated CO₂.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the dynamic CO₂ adsorption capacity of the sorbent (grams of CO₂ per kg of sorbent) and the concentration factor achieved.

Protocol for Sabatier Reactor Performance Characterization

This protocol outlines the testing of a Sabatier reactor's conversion efficiency.

- Objective: To determine the conversion efficiency of a Sabatier reactor catalyst under varying operational parameters.

- Materials:

- Sabatier reactor core containing the catalyst (e.g., Ruthenium on Alumina).

- Precisely controlled supply of H₂ and CO₂ gases.

- Heated reactor jacket with temperature control.

- In-line Gas Chromatograph (GC) or Mass Spectrometer (MS) for product analysis.

- Pressure regulators and sensors.

- Condenser and water separator.

- Procedure:

- System Preparation: Purge the reactor with an inert gas. Set the reactor to the desired operating temperature (typically 300-400°C).

- Reaction Initiation: Introduce H₂ and CO₂ at a stoichiometric ratio of 4:1. Adjust the total gas flow rate to achieve the desired space velocity.

- Steady-State Operation: Maintain conditions until the product stream composition stabilizes (monitored via GC/MS).

- Product Analysis: Sample the output gas stream after the condenser to analyze the composition (remaining H₂, CO₂, CH₄). Collect and measure the quantity of water produced.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the CO₂ conversion efficiency: [(CO₂in - CO₂out) / CO₂_in] * 100%. Correlate efficiency with temperature, pressure, and space velocity.

The logical and material flow between these subsystems and the crew is best understood through a system diagram.

Carbon Loop Closure in Life Support Systems

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The experimental and operational protocols rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key items critical for research and development in carbon loop closure.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Carbon Loop Systems

| Item Name | Function / Role in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Solid Amine Sorbents | Porous beads or structured substrates with amine functional groups for selective CO₂ capture from cabin air through chemical sorption [1]. |

| Sabatier Catalyst | A catalytic surface, typically ruthenium or nickel supported on alumina, that lowers the activation energy for the reaction between CO₂ and H₂, enabling efficient production of water and methane [1]. |

| Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) Electrolysis Cell | The core component of a modern OGA, where a solid polymer electrolyte facilitates the efficient splitting of water into oxygen and hydrogen gas using an electric current [1]. |

| Mass Flow Controllers (MFCs) | Critical for laboratory setups, these devices precisely control and measure the flow rates of gases (e.g., CO₂, H₂, N₂) into reactors, ensuring accurate stoichiometry and repeatable experimental conditions. |

| Gas Chromatograph / Mass Spectrometer (GC/MS) | An essential analytical instrument for quantifying the composition of gas streams before, during, and after reactor experiments, used to determine conversion efficiencies and identify byproducts. |

Integration and Future Directions for Full Closure

The ultimate objective is the integration of these subsystems into a highly reliable and largely autonomous ECLSS. The current state-of-the-art, as exemplified by the ACLS, represents a hybrid system—it closes a significant portion of the loop but is not fully closed due to the venting of methane, which contains valuable hydrogen atoms [1]. This hydrogen loss must be compensated by the electrolysis of resupplied water from Earth, creating a critical dependency.

Future research is directed towards achieving 100% oxygen recovery from metabolic CO₂. This requires addressing the hydrogen loss in the Sabatier process. Promising paths include:

- Bosch Reaction: An alternative to the Sabatier process that produces solid carbon instead of methane, thereby retaining all hydrogen within the water product. The main challenge is managing the solid carbon, which can foul the reactor.

- Methane Pyrolysis: Coupling a Sabatier reactor with a secondary unit that "cracks" methane (CH₄) into solid carbon and hydrogen gas, with the hydrogen being recycled back to the Sabatier reactor. This would create a fully closed carbon-oxygen cycle.

- In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU): For planetary surfaces, future systems could extract hydrogen from local resources, such as water ice on the Moon or Mars, to offset the hydrogen vented as methane and achieve full loop closure with local materials [5].

System reliability is paramount, as failure can be catastrophic. Strategies such as redundant components, regular maintenance protocols, and thorough ground-based testing are employed to ensure these systems can operate continuously for years with minimal intervention [5] [6]. As we venture further into the solar system, the critical role of a fully closed carbon loop will only increase, forming the very foundation of sustainable human presence in space.

Closing the carbon loop is a fundamental challenge for advanced life support systems (LSS) required for long-duration human space exploration. These systems must maintain a breathable atmosphere, provide sustenance, and manage waste within the isolated environment of a spacecraft or planetary habitat. The core of this challenge lies in effectively managing carbon dioxide (CO₂) produced by crew respiration and various processes, converting it from a waste product into valuable resources. This technical guide details the three core technological components—concentration, reduction, and oxygen generation—that work in concert to achieve carbon loop closure. The integration of these processes enables the creation of a self-sustaining ecosystem, reducing reliance on Earth-based resupply and enabling ambitious missions to the Moon, Mars, and beyond [7] [8].

The urgency for developing robust LSS is underscored by data from the Global Carbon Budget 2024, which shows atmospheric CO₂ concentrations reached 419.31 ppm in 2023, with preliminary data for 2024 suggesting a rise to 422.45 ppm [9]. In the confined environment of a space habitat, preventing the accumulation of CO₂ is immediately critical to crew health, while the subsequent conversion of this CO₂ is crucial for long-term mission sustainability. Research and development in this field, exemplified by consortia such as NASA-funded initiatives and the European MELiSSA (Micro-Ecological Life Support System Alternative) project, are focused on creating efficient, reliable, and energy-effective systems for these purposes [7] [8].

Carbon Dioxide Concentration

The first step in closing the carbon loop is the efficient removal and concentration of CO₂ from the cabin atmosphere. This process prevents the buildup of toxic CO₂ levels and provides a concentrated stream for downstream reduction processes. Traditional methods have relied on physical adsorption materials like zeolites, but recent innovations focus on increasing efficiency and lowering the energy required for regeneration.

Advanced Materials for CO₂ Capture

A groundbreaking development in this field is the creation of Micro/Nano-Reconfigurable Robots (MNRMs) for intelligent carbon management. These materials are not robots in a macroscopic sense but are molecular-scale systems designed to act autonomously in response to environmental cues. As detailed in recent research, MNRMs can capture CO₂ with high capacity and regenerate at remarkably low temperatures [10].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of CO₂ Capture Technologies

| Technology/Material | CO₂ Adsorption Capacity | Regeneration Temperature | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro/Nano-Reconfigurable Robot (MNRM) | 6.19 mmol g⁻¹ | 55 °C | Ultralow regeneration energy, non-contact magnetic actuation, prevents local overheating [10] |

| Temperature-Sensitive Fiber-Based Sorbents | >6 mmol g⁻¹ | ~60 °C | Class-leading energy efficiency for solid amines [10] |

| Ag/UiO-66 MOF | 1.14 mmol g⁻¹ | Photothermal (90.5% release) | Utilizes solar energy for regeneration [10] |

| Liquid Amines | Varies | >110 °C | Established technology, but high energy penalty and health risks from amine leakage [10] |

The MNRM is synthesized from a cross-linked network of cellulose nanofibers (CNF), polyethyleneimine (PEI) as the CO₂-hunting amino group provider, Pluronic F127 (F127) as a temperature-sensitive molecular switch, graphene oxide (GO) as a thermally conductive bridge, and Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles (NPs) as a photothermal conversion and magnetically-driven engine [10]. The core innovation is its reconfigurability:

- Nano-reconfiguration: The thermosensitive F127 network undergoes a conformational transition. At lower temperatures, the molecular chains are extended, facilitating CO₂ access to amine groups. Upon heating, the chains curl, altering the amino microenvironment's electrostatic potential and energy levels. This change weakens the interaction with adsorbed CO₂ products, inhibiting the formation of stable urea derivatives and enabling regeneration at a mere 55 °C [10].

- Micro-reconfiguration: The Fe₃O₄ NPs allow the material to be manipulated by an external magnetic field. This enables non-contact movement and heat management, preventing local overheating during the photothermal regeneration process and significantly extending the material's service life [10].

The efficacy of this system was validated in a confined-space animal model, where MNRMs prolonged the survival time of mice by 54.61% compared to the control group, effectively mitigating the risk of hypercapnia-induced lung failure [10].

Experimental Protocol: Testing MNRM CO₂ Adsorption Capacity

Objective: To determine the CO₂ adsorption capacity and regeneration efficiency of the Micro/Nano-Reconfigurable Robot (MNRM) under controlled conditions. Materials:

- Synthesized MNRM material (e.g., MNRM-Fe₃O₄(20)/F127(15))

- Fixed-bed adsorption reactor connected to a thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA) or gas chromatograph (GC)

- CO₂ gas supply (typically 0.5-1% CO₂ in N₂ to simulate cabin air)

- Water vapor generator

- Light source for photothermal testing (e.g., simulated solar light)

- Alternating magnetic field generator

Methodology:

- Preparation: The MNRM sample is placed in the reactor and pre-dried under a gentle N₂ stream at 40°C for 30 minutes.

- Adsorption Cycle: A gas mixture of 0.5% CO₂ in N₂, saturated with 2% water vapor at 25°C, is passed through the reactor. The weight gain (via TGA) or the outlet CO₂ concentration (via GC) is monitored until saturation is reached. The adsorption capacity (mmol g⁻¹) is calculated from this data [10].

- Regeneration Cycle: The CO₂ feed is switched to pure N₂. The regeneration is initiated using one of two methods:

- Photothermal Method: The sample is irradiated with a light source (e.g., 1 sun intensity) while the temperature is recorded.

- Magnetic Actuation Method: An alternating magnetic field is applied to actuate the Fe₃O₄ NPs, providing non-contact heating.

- Desorption Monitoring: The released CO₂ is quantified. The cycle is repeated at least 10 times to assess the material's stability and capacity retention [10].

Diagram 1: MNRM CO₂ Adsorption/Desorption Workflow.

Carbon Dioxide Reduction

Once captured and concentrated, CO₂ can be reduced into valuable organic compounds that serve as precursors for food, bioplastics, and other materials. This process transforms a waste product into essential resources, enhancing the sustainability of the life support system. Two prominent technological approaches are Chemical Looping Combustion (CLC) and biological conversion via microbial biomanufacturing.

Chemical Looping Combustion (CLC)

CLC is a promising technology for managing CO₂ emissions with an inherently low energy penalty for capture. While its primary application in a life support context could be for energy generation from waste carbon, its principle is highly relevant for achieving efficient combustion with near-pure CO₂ output [11].

The process utilizes a metal oxide (the "oxygen carrier"), such as iron, nickel, or copper oxides, circulated between two reactors:

- Fuel Reactor: The metal oxide (MeO) reacts with a fuel (e.g., syngas from waste), oxidizing the fuel to CO₂ and H₂O while the metal oxide is reduced to its metal form (Me) or a lower oxide.

- Reaction:

Fuel (CₙHₘOₖ) + MeO → CO₂ + H₂O + Me

- Reaction:

- Air Reactor: The reduced oxygen carrier (Me) is transferred to the air reactor, where it is re-oxidized by air.

- Reaction:

Me + Air (O₂ + N₂) → MeO + N₂

- Reaction:

The key advantage is that the fuel reactor's exhaust stream is not diluted with nitrogen from the air, consisting primarily of CO₂ and H₂O. After water condensation, a nearly pure CO₂ stream is obtained, ready for storage or, more pertinently for LSS, as a feedstock for biological reduction processes [11]. When using biofuels, this process can achieve negative emissions [11].

Table 2: Comparison of CO₂ Reduction Pathways

| Reduction Pathway | Principle | Products | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Looping Combustion (CLC) | Metal oxide-mediated fuel combustion without N₂ dilution | Concentrated CO₂ stream, energy | Oxygen carrier lifetime and reactivity, fuel flexibility [11] |

| Anaerobic Digestion (AD) | Microbial conversion of organic waste in absence of oxygen | Volatile Fatty Acids (VFAs), CO₂ | Controlling methane production, microbial community balance [7] |

| Phototrophic Biosystem | Cyanobacteria using light and CO₂ for photosynthesis | Oxygen, protein-rich biomass, PHA bioplastics, β-carotene [7] | Efficiency in space conditions (e.g., low gravity, radiation) [7] |

Biological Reduction and Biomanufacturing

Biological systems offer a versatile pathway for CO₂ reduction. The AD ASTRA consortium, for example, is developing an integrative system that links anaerobic digestion with a phototrophic biosystem [7].

- Anaerobic Digestion (AD): This process uses microbial communities to break down human waste. The research focuses on optimizing these communities to produce volatile fatty acids (VFAs) like acetate, instead of methane. These VFAs and the resulting CO₂ are then used as feedstocks for the next stage [7]. SLU researchers use molecular and sequencing-based techniques to monitor the conversion of waste to VFAs and control methane production by analyzing the

mcrAgene responsible for methane biosynthesis [7]. - Phototrophic Biosynthesis: Cyanobacteria and other microbes are engineered to consume the VFAs, CO₂, and nutrients from processed wastewater. They produce oxygen, protein-rich biomass for food, polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) polymers for bioplastics, and valuable natural products like β-carotene [7].

Another innovative approach, termed Alternative Feedstock-driven In-Situ Biomanufacturing (AF-ISM), leverages local resources. It uses Martian or Lunar regolith simulants as a mineral source and anaerobically pretreated fecal waste as a nutrient source to support the microbial production of nutrients like lycopene by Rhodococcus jostii PET strain S6 (RPET S6). This process has been validated under microgravity conditions, achieving production levels comparable to those on Earth [12].

Experimental Protocol: Anaerobic Digestion for Volatile Fatty Acid Production

Objective: To establish and optimize an anaerobic digestion process for converting human waste into volatile fatty acids (VFAs) while suppressing methane production. Materials:

- Anaerobic bioreactor with temperature and pH control

- Inoculum (adapted anaerobic microbial consortium)

- Synthetic or real human waste feedstock

- Anaerobic chamber for sample handling

- Gas chromatograph (GC) for VFA analysis (e.g., acetate, propionate, butyrate)

- PCR machine and reagents for genetic analysis (e.g.,

mcrAgene quantification)

Methodology:

- Reactor Setup: The bioreactor is filled with inoculum and feedstock. Anaerobic conditions are maintained by sparging with N₂/CO₂. Temperature is kept at mesophilic ranges (~35°C), and pH is monitored and controlled [7].

- Process Monitoring:

- Chemical Analysis: Liquid samples are taken regularly, centrifuged, and the supernatant is analyzed by GC to quantify VFA production and composition.

- Genetic Analysis: DNA is extracted from sludge samples. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) is performed targeting the

mcrAgene to monitor the abundance of methanogenic archaea. The goal is to manipulate conditions (e.g., pH, retention time) to minimizemcrAexpression [7].

- Optimization: The hydraulic retention time (HRT) and organic loading rate (OLR) are varied to find the optimal balance for high VFA yield and low methane production. The microbial community structure is characterized using 16S rRNA sequencing to understand the factors driving efficient VFA production [7].

Diagram 2: Anaerobic Digestion to VFAs Process.

Oxygen Generation

The final component of the carbon loop is the regeneration of oxygen, which is vital for crew respiration. Oxygen can be produced abiotically through the electrolysis of water, or biotically through photosynthetic organisms.

Biological Oxygen Generation

Phototrophic organisms, such as cyanobacteria and algae, use light energy to split water molecules and reduce CO₂, releasing oxygen as a byproduct. The AD ASTRA consortium engineers cyanobacterial strains to use the CO₂ and VFAs from the anaerobic digestion process, simultaneously producing oxygen and valuable biomass [7]. A significant research focus is understanding how simulated low gravity affects these phototrophic metabolisms and bioproduction rates [7].

The AF-ISM process also contributes to oxygen generation as part of the microbial metabolism during lycopene production, demonstrating the integration of multiple life support functions within a single biological process [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Carbon Loop Closure Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Pluronic F127 | Temperature-sensitive molecular switch | Enables low-temperature (55°C) regeneration of MNRM CO₂ sorbents by undergoing conformational change [10] |

| Polyethyleneimine (PEI) | CO₂ "molecular hunter"; provides amine groups for chemical CO₂ adsorption | Primary functional group in MNRMs and other solid amine sorbents for capturing CO₂ [10] |

| Fe₃O₄ Nanoparticles | Photothermal conversion and magnetically-driven engine | Provides non-contact heating and actuation in MNRMs for energy-efficient sorbent regeneration [10] |

| mcrA Gene Primers | Genetic marker for methanogenic archaea | Used in qPCR to monitor and suppress methane production in anaerobic digesters, steering products toward VFAs [7] |

| Lunar/Martian Regolith Simulants | Analog for extraterrestrial mineral sources | Serves as a source of essential minerals (e.g., P, S, K, Mg) for microbial growth media in ISRU experiments (e.g., AF-ISM) [12] |

| Rhodococcus jostii PET S6 | Engineered microbial chassis for bioproduction | Upcycles plastic hydrolysate or uses regolith minerals to produce lycopene; a candidate for off-world biomanufacturing [12] |

The path to sustainable long-duration spaceflight hinges on the robust integration of the core components: CO₂ concentration, reduction, and oxygen generation. The field is moving beyond simple, energy-intensive physical-chemical systems toward hybrid and fully biological solutions that offer greater closure of the carbon loop. Innovations like micro/nano-reconfigurable robots for low-energy CO₂ capture, chemical looping for efficient combustion, and engineered microbial consortia that transform waste into food, oxygen, and materials represent the cutting edge of life support system research. The integration of these technologies, supported by in-situ resource utilization, will be the cornerstone of future closed-loop life support systems, enabling humanity to become a multi-planetary species.

The development of advanced, closed-loop life support systems is a critical prerequisite for long-duration human space exploration. These systems must efficiently regenerate vital resources—oxygen, water, and food—from astronaut metabolic waste, minimizing reliance on resupply from Earth. The core challenge lies in achieving robust carbon loop closure, wherein exhaled carbon dioxide (CO₂) is reconstituted into breathable oxygen and edible biomass. On Earth, the planet's natural ecosystems have performed this precise function for millennia through the global carbon cycle. This whitepaper examines terrestrial carbon cycle processes as analogue systems to inform the engineering of bioregenerative life support systems (BLSS) for space applications. By analyzing the mechanisms that govern carbon storage and flux in Earth's biosphere, researchers can derive design principles, identify potential bottlenecks, and develop strategies for creating stable, long-term life support systems for missions to the Moon, Mars, and beyond [13].

Terrestrial Carbon Cycle Fundamentals

The terrestrial carbon cycle represents a planetary-scale, closed-loop life support system, seamlessly transferring carbon between the atmosphere, biosphere, and pedosphere (soil). Understanding its components and fluxes is foundational to emulating its efficiency in a controlled habitat.

Key Carbon Pools and Fluxes

The major stocks and flows of carbon create a dynamic equilibrium. Carbon pools are reservoirs where carbon is stored for varying durations, while carbon fluxes are the rates of transfer between these pools [14]. The primary fluxes driving the cycle are gross primary production (GPP) and ecosystem respiration.

Table 1: Major Terrestrial Carbon Pools and Fluxes (Approximated from Global Carbon Budget 2025) [14] [15]

| Component | Estimated Magnitude (Pg C) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Atmospheric Pool | ~900 Pg C | Carbon stored as CO₂ and other gases; the immediate source for photosynthesis. |

| Vegetation Pool | ~450-650 Pg C | Carbon incorporated into plant biomass (leaves, stems, roots). |

| Soil Pool | ~1500-2400 Pg C | Carbon stored as organic matter in soils; the largest terrestrial pool. |

| Gross Primary Production (GPP) | ~113 Pg C yr⁻¹ | Total CO₂ captured by plants via photosynthesis per year. |

| Ecosystem Respiration | ~111 Pg C yr⁻¹ | Total CO₂ released back to the atmosphere by plants and soil organisms. |

| Net Land Sink (S_LAND) | 1.9 ± 1.1 Pg C yr⁻¹ (2024) | Net annual CO₂ uptake by land; the residual of GPP minus respiration and disturbances. |

Critical Processes for Loop Closure

For carbon loop closure, several biological processes are paramount:

- Photosynthesis: The foundational process that captures atmospheric CO₂ and converts it into organic compounds using light energy. This is the analogue for food and biomass production in a BLSS [14].

- Respiration: The process in plants and soil microorganisms that metabolizes organic carbon, releasing CO₂ back into the atmosphere. In a BLSS, this must be carefully managed to balance the system [14].

- Soil Organic Matter (SOM) Formation and Decomposition: This represents a critical carbon stabilization process. In a BLSS, an analogous "soil" or compost system could be key for recycling solid waste and stabilizing carbon cycles over the long term [16].

The following diagram illustrates the core logical relationships and carbon fluxes within the terrestrial carbon cycle that serve as the model for life support system closure.

Quantitative Framework for Analogue Analysis

Translating terrestrial cycle insights into engineering parameters requires a rigorous quantitative framework. The following data, synthesized from current global budgets and operational space systems, provides critical benchmarks for BLSS development.

Table 2: Carbon Flux and Sequestration Rates in Terrestrial and BLSS Contexts [1] [14] [15]

| System / Process | Rate / Capacity | Relevance to BLSS Design |

|---|---|---|

| Global Net Land Sink (S_LAND) | 1.9 ± 1.1 Pg C yr⁻¹ | Demonstrates planetary-scale capacity for anthropogenic CO₂ offsetting. |

| Ocean Carbon Sink (S_OCEAN) | 3.4 ± 0.4 Pg C yr⁻¹ | Analogous to physico-chemical CO₂ scrubbing systems. |

| ESA ACLS Water Savings | ~400 liters/year | Quantifies resupply mass reduction via CO₂ recycling to O₂. |

| ESA ACLS Oxygen Production | Supply for 3 astronauts | Benchmarks for current state-of-the-art mechanical closure. |

| Free-Air CO₂ Enrichment (FACE) NPP boost | 10-25% initial enhancement [16] | Informs expectations for crop yield response to elevated CO₂ in habitats. |

Experimental Protocols for Carbon Cycle Research

Methodologies developed for terrestrial carbon science provide robust experimental templates for BLSS component testing.

Free-Air CO₂ Enrichment (FACE) Experiments

Objective: To quantify the long-term response of ecosystem productivity (NPP) and carbon storage to elevated atmospheric CO₂ levels, simulating the high-CO₂ environments anticipated in space habitats [16].

Detailed Methodology:

- Site Establishment: Select a representative ecosystem (e.g., forest, grassland). Arrange multiple experimental plots in a randomized block design. For example, the Duke and ORNL FACE experiments used plots of 25-30m diameter [16].

- CO₂ Treatment Application: Construct a network of pipes and towers to release pure CO₂ around the treatment plots. Use a computerized control system that monitors wind speed and direction in real-time to adjust CO₂ release, maintaining a preset elevated concentration (e.g., +200 ppm above ambient) [16].

- Data Collection:

- Carbon Fluxes: Measure Net Primary Production (NPP) via annual harvest of vegetation or allometric tree growth measurements. Quantify soil CO₂ efflux (respiration) using automated soil chambers.

- Carbon Stocks: Conduct periodic biomass inventories (above and below-ground). Collect soil cores to depth for analysis of Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) content.

- Nutrient Cycling: Analyze foliar and soil N content. Measure rates of soil net nitrogen mineralization (f~Nmin~) through in-situ incubation assays [16].

- Data Analysis: Contrast C and N cycle responses (e.g., NPP, NUE, f~Nup~) between elevated CO₂ and ambient control plots over a multi-year period to assess sustainability and the emergence of nutrient limitations [16].

Eddy Covariance Flux Measurements

Objective: To provide continuous, direct measurement of net ecosystem-atmosphere exchange of CO₂ (NEE) for model validation.

Detailed Methodology:

- Instrumentation Setup: Erect a tall tower (exceeding canopy height) equipped with a 3D sonic anemometer (measures wind speed) and a high-precision, fast-response infrared gas analyzer (IRGA) (measures CO₂ and H₂O concentration).

- Data Acquisition: Collect raw data on wind vectors and gas concentrations at high frequency (10-20 Hz).

- Flux Calculation: Process the high-frequency data to compute the net ecosystem exchange (NEE) as the mean of the covariance between vertical wind velocity and CO₂ concentration.

- Gap-Filling and Partitioning: Apply statistical models to fill data gaps from instrument failure or non-ideal turbulence. Partition NEE into its component fluxes, Gross Primary Production (GPP) and Ecosystem Respiration (R~eco~).

The workflow for implementing these key experiments is methodically structured as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

Research at the intersection of terrestrial carbon science and BLSS development relies on a suite of specialized reagents, instruments, and models.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Carbon Cycle and BLSS Investigations

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotopes (¹³C, ¹⁵N) | Trace the fate of carbon and nutrients through ecosystems. | Quantifying C allocation in plants; tracing waste N in BLSS recycling loops. |

| Fast-Response IRGA | Measures turbulent fluctuations of CO₂ and H₂O concentrations. | Core sensor for eddy covariance towers; monitoring cabin atmosphere. |

| Dynamic Global Vegetation Models (DGVMs) | Simulate vegetation dynamics and biogeochemical cycles. | Projecting long-term BLSS stability; testing N limitation scenarios [15] [16]. |

| Amine-Based Sorbents | Chemically trap and concentrate CO₂ from the air. | CO₂ removal and concentration in systems like ESA's ACLS [1]. |

| Sabatier Reactor | Catalytically converts CO₂ and H₂ into CH₄ and H₂O. | Key physico-chemical component for closing the oxygen loop [1]. |

| Leaf Fluorometer | Measures chlorophyll fluorescence, a proxy for photosynthetic efficiency. | Monitoring plant health and CO₂ response in BLSS crop chambers. |

Carbon-Climate Feedback and BLSS Stability

A primary lesson from terrestrial carbon science is that carbon-cycle processes are highly sensitive to environmental conditions, leading to complex feedback loops. The phenomenon of Progressive Nitrogen Limitation (PNL) is a critical feedback with direct implications for BLSS longevity [16]. In terrestrial ecosystems, eCO₂ initially boosts plant growth (NPP), but this increased growth requires more nitrogen. When N is limited, the extra plant biomass and soil carbon produced sequester available N, making it less accessible for further growth. This can cause the initial CO₂ fertilization effect to decline over time, as observed at the ORNL FACE site [16].

In a BLSS context, this translates to a risk that enhanced food production efforts could deplete available nutrients, leading to a gradual decline in crop yields unless robust nutrient recycling systems—analogous to soil microbial networks and decomposers—are in place to regenerate essential elements from plant and human waste.

Synthesis and Research Outlook

Integrating terrestrial carbon cycle principles into BLSS engineering reveals a clear pathway toward robust carbon loop closure. The operational ESA Advanced Closed Loop System (ACLS), which combines amine-based CO₂ capture with a Sabatier reactor and electrolysis, represents a significant achievement in physico-chemical closure of the oxygen loop, recovering about 50% of the CO₂ and saving 400 liters of water annually [1]. This mirrors the function of the inorganic terrestrial carbon cycle.

The future challenge lies in fully integrating the biological component—the food production system—in a way that mimics the resilient, self-sustaining nature of Earth's ecosystems. Priority research areas, supported by ongoing funding initiatives from NASA and the DOE [17], must focus on:

- Closing the Nutrient Loop: Developing efficient waste processing systems to convert solid and liquid wastes into plant-available nutrients, preventing PNL in BLSS agriculture.

- Multi-Kingdom Integration: Engineering balanced systems that incorporate plants, microbes, and potentially other organisms to create a more resilient and self-regulating ecology.

- Modeling and Validation: Using terrestrial carbon cycle models, especially those that incorporate C-N interactions [16], to predict BLSS behavior and guide design before costly prototyping and in-situ testing.

By continuing to treat Earth's biosphere as the ultimate analogue system, researchers can extract the fundamental principles needed to build the life-support ecosystems that will sustain humanity as we venture into the solar system.

The pursuit of deep space exploration, encompassing missions to the Moon and Mars, is fundamentally constrained by the requirement for life support systems that are both highly reliable and self-sustaining. Unlike missions in low Earth orbit (LEO), where resupply from Earth is feasible, deep space habitats require near-perfect closure of mass loops, particularly for critical elements like carbon, oxygen, and water. Carbon dioxide (CO₂), a primary metabolic waste product of human respiration, must be efficiently captured and recycled into breathable oxygen and other valuable resources. This whitepaper details the current state-of-the-art in Advanced Life Support Systems (ALS), tracing the evolution from operational systems aboard the International Space Station (ISS) to the groundbreaking technologies and simulation frameworks under development for future deep space habitats. The central thesis is that closing the carbon cycle is not merely an incremental improvement but a paradigm shift essential for long-duration, Earth-independent human presence in space.

Current State-of-the-Art: ISS-Based Systems

The International Space Station serves as the primary testbed for validating life support technologies in a sustained microgravity environment. After nearly 25 years of continuous human presence, the systems aboard the ISS represent the most advanced closed-loop life support capabilities ever operationally deployed [18] [19].

The Advanced Closed Loop System (ACLS)

A cornerstone of current carbon loop closure efforts on the ISS is the Advanced Closed Loop System (ACLS), developed by the European Space Agency (ESA). This system is a significant step towards revitalizing the atmosphere within the spacecraft by recycling carbon dioxide into oxygen [1].

The ACLS is integrated into a standard International Standard Payload Rack, measuring approximately 2 meters high, 1 meter wide, and 85.9 cm deep. It performs three major functions [1]:

- Carbon Dioxide Concentration (CCA): The system concentrates CO₂ from the cabin air using unique amine-developed beads, maintaining acceptable CO₂ levels for the crew.

- Carbon Dioxide Reprocessing (CRA): The concentrated CO₂ is then fed into a Sabatier reactor, where it reacts with hydrogen (a byproduct of oxygen generation) over a catalyst to form water and methane.

- Oxygen Generation (OGA): The water produced by the Sabatier reactor is subsequently split via electrolysis into breathable oxygen and hydrogen. The oxygen is returned to the cabin, and the hydrogen is fed back into the Sabatier reactor.

This process allows the ACLS to recycle about 50% of the CO2, saving approximately 400 liters of water that would otherwise need to be launched from Earth each year. The methane produced is vented overboard, which is the primary reason the system does not achieve 100% carbon recovery [1].

Water Recovery and Oxygen Generation

Parallel developments on the ISS have focused on closing the water loop, which is intrinsically linked to oxygen production. The U.S. segment of the ISS has achieved 98% water recovery, a critical benchmark for missions beyond LEO where resupply is not feasible [18]. This recovered water is a key feedstock for the Oxygen Generation System (OGS), which uses electrolysis to produce oxygen for the crew. Maintenance of these systems, such as the replacement of components and advanced hydrogen sensors in the OGS, is a routine but vital activity for station operations [20].

In-Space Production and Resource Utilization

Beyond atmospheric revitalization, the ISS is pioneering technologies to utilize local resources, a concept known as In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU). Key advancements include [18]:

- Scalable Crop Production: Over 50 species of plants have been grown aboard the station using aeroponic and hydroponic systems. These systems are vital for producing fresh food and nutrients, and they contribute to carbon cycling by consuming CO₂ and producing oxygen through photosynthesis.

- In-Space Manufacturing: 3D printing has been successfully demonstrated for creating tools and parts on-demand. The European Space Agency has 3D-printed the first metal part on the station, a step towards using recycled materials or even lunar and Martian regolith (soil) for construction. This reduces the need to launch supplies from Earth and supports habitat construction.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics of Current ISS Life Support Systems

| System/Technology | Key Metric | Performance Value | Significance for Deep Space |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced Closed Loop System (ACLS) | CO₂ Recycling Rate | ~50% [1] | Demonstrates core technology for O₂ recovery; highlights need to close methane venting loop. |

| Water Recovery System | Water Recovery Rate | 98% [18] | Meets target for water independence on long-duration missions beyond LEO. |

| Oxygen Generation System | Feedstock | Recovered Water [18] | Directly links water and oxygen loops, reducing Earth-based resupply. |

| Food Production | Plant Species Grown | >50 [18] | Tests scalable crop systems for fresh food and supplemental atmospheric revitalization. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

The advancement of life support systems relies on rigorous experimentation, both in space and on the ground. The following protocols detail the current approaches for testing and validating these technologies.

Protocol: Advanced Closed Loop System Operation

Objective: To concentrate cabin CO₂ and convert it into oxygen, thereby reducing the reliance on Earth-based resupply of water for oxygen generation [1].

- Carbon Dioxide Concentration: Cabin air is passed through a column containing amine-developed beads, which selectively trap CO₂ molecules.

- Desorption and Processing: Steam is applied to the saturated beads to release the concentrated CO₂ stream.

- Sabatier Reaction: The concentrated CO₂ is mixed with hydrogen (H₂) and passed over a catalyst in a Sabatier reactor. The reaction CO₂ + 4H₂ → CH₄ + 2H₂O occurs, producing methane (CH₄) and water (H₂O).

- Water Electrolysis: The produced water is condensed and fed into an electrolysis assembly, where an electric current splits it into oxygen (O₂) and hydrogen (H₂). The oxygen is returned to the cabin atmosphere.

- Product Management: The hydrogen is recycled to the Sabatier reactor. The methane is vented into space.

Protocol: HabSim Virtual Testbed for Habitat Resilience

Objective: To model disruptive events in a deep space habitat and evaluate the efficacy of different contingency strategies for restoring system functionality, particularly during the critical transition from a dormant to a crewed state [21].

- System Modeling: A high-fidelity numerical model of a deep space habitat is created, integrating key subsystems including pressure control, thermal regulation, power management, and atmospheric composition.

- Disruption Introduction: A disruptive event (e.g., a micrometeoroid impact causing a pressure leak and dust accumulation on radiators) is introduced into the simulation.

- Propagation Analysis: The testbed models how the initial disruption propagates through the interconnected habitat systems, identifying cascading failures.

- Contingency Strategy Testing: Researchers implement and test different repair and recovery strategies. These can involve:

- Single-Contingency Responses: Addressing one primary failure (e.g., patching a leak).

- Multiple-Contingency Responses: Addressing multiple, interconnected failures simultaneously (e.g., patching a leak, removing dust from radiators, and compensating for temperature and pressure decreases).

- Strategy Optimization: Data from the simulations are used to identify the most effective strategies for restoring the habitat to a safe and fully functional state. The research has demonstrated that multiple-contingency responses are typically required for a successful recovery [21].

Diagram 1: Habitat resilience testing workflow.

Future Directions: Technologies for Deep Space Habitats

As missions venture farther from Earth, the technologies tested on the ISS are being refined and integrated with novel concepts to create truly sustainable habitats for the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

Closing the Carbon Loop: Multi-Product CO₂ Utilisation

Current research is exploring pathways to achieve a higher degree of carbon cycle closure by converting CO₂ into valuable products beyond just oxygen. Multi-product Carbon Capture and Utilisation (CCU) configurations represent a promising avenue. Studies have evaluated systems where CO₂ is captured and converted into dimethyl ether (DME) and polyols simultaneously (parallel configuration) or in consecutive cycles (cascade configuration) [22]. When combined with a small amount of CO₂ storage (CCUS), these multi-product systems can achieve significant reductions in climate change potential (up to -18% compared to a reference system) while remaining economically feasible, primarily due to the replacement of fossil feedstocks with utilized CO₂ [22].

Autonomous and Resilient Habitat Operations

The Resilient Extra-Terrestrial Habitat institute (RETHi) is pioneering the development of smart habitats that can autonomously anticipate, adapt to, and recover from disruptions. As simulated using tools like HabSim, future habitats will require complex, multi-contingency response plans to handle events like micrometeoroid impacts, fires, or moonquakes [21]. The research demonstrates that a single response is insufficient; a coordinated strategy addressing dust removal, temperature control, and pressure stabilization is necessary for a successful recovery. This resilience is critical for maintaining a stable, life-sustaining environment where carbon loops remain closed even in the face of failures.

Biological Life Support Systems & In-Situ Resource Utilization

Biological systems will play an increasingly important role in closing carbon loops. Beyond supplemental food production, future research will focus on integrating microbial processes and higher plant growth to create a more balanced and robust Ecological Life Support System (ELSS). These systems can contribute to waste processing, water purification, and atmospheric management. Furthermore, the use of local resources, such as Martian CO₂ for synthetic fuel production or lunar regolith for 3D printing habitats, will be essential for achieving long-term sustainability and reducing the mass that must be launched from Earth [18].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Carbon Management Technologies

| Technology | Current TRL* (ISS) | Target TRL (Deep Space) | Key Challenge | Carbon Loop Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sabatier Process (ACLS) | High (8-9) [1] | 9 | Venting of methane (CH₄) breaks the carbon loop. | Partial (~50% recovery) |

| Bosch Reaction | Medium (4-5) | 6-7 | Carbon deposition clogs the reactor, requiring maintenance. | High (Theoretically 100%) |

| Photobioreactors (Algae) | Medium (4-5) | 7 | System volume, power, and stability in microgravity. | High (Converts CO₂ to O₂ and biomass) |

| Multi-Product CCU (e.g., DME) | Low (2-3) [22] | 5-6 | System complexity and energy efficiency for deep space. | High (Converts CO₂ to useful products) |

| *Technology Readiness Level |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The development and testing of advanced life support systems rely on a suite of specialized materials and reagents.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Life Support Systems

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Amine-based Sorbents | Chemically captures and concentrates CO₂ from the cabin atmosphere. | The "unique amine-developed beads" used in the ACLS's Carbon Dioxide Concentration Assembly (CCA) [1]. |

| Sabatier Catalyst | Facilitates the chemical reaction between CO₂ and H₂ to produce methane and water. | A nickel or ruthenium-based catalyst used in the Carbon Dioxide Reprocessing Assembly (CRA) of the ACLS [1]. |

| Electrolyte for Electrolysis | A medium that conducts ions to facilitate the splitting of water into oxygen and hydrogen. | A solid polymer electrolyte (like Nafion) or a liquid alkaline solution used in the Oxygen Generation Assembly (OGA) [18] [1]. |

| Microbial Cultures | Used to process waste, produce nutrients, or in bioprocessing of CO₂. | Cultures of specific bacteria or cyanobacteria studied for waste recycling or food production in closed systems. |

| Plant Growth Media | A soil-less substrate for supporting plant growth in space. | Hydroponic nutrient solutions or aeroponic misters used to grow over 50 plant species on the ISS [18]. |

| 3D Printing Feedstock | Material for manufacturing tools and parts on-demand. | Recycled plastics or metals, with future potential for regolith-based composites, used in ISS 3D printers [18]. |

The journey from the International Space Station to future deep space habitats is marked by a critical, escalating requirement: the need to close mass loops, with carbon being a central element. The current state-of-the-art, exemplified by the ISS's 98% water recovery and the ACLS's 50% CO₂ recycling, provides a formidable foundation. However, achieving the near-total closure required for Earth-independent exploration demands a new generation of technologies. The path forward will be paved by integrating physicochemical systems like multi-product CCU, biological systems for food and air revitalization, and resilient autonomous operations as modeled by tools like HabSim. Closing the carbon cycle is not a solitary technical hurdle but a systems-level challenge that will define the feasibility, safety, and sustainability of humanity's future as a deep-space species.

Technological Pathways and System Architectures for Carbon Recycling

In the context of Advanced Life Support (ALS) systems for long-duration space missions, achieving closure of the carbon loop is a fundamental challenge. Physical-Chemical (P/C) systems, particularly Sabatier reactors and electrolyzers, form the technological backbone for converting waste carbon dioxide into vital resources, thereby reducing dependence on Earth resupply. An ALS system's degree of closure is defined as the percentage of total resources provided by recycling, with higher closure dramatically reducing launch mass and enabling sustained human presence in space [23]. The core function of these P/C systems is to facilitate the Carbon Dioxide Reduction Assembly (CDRA), a critical process where metabolic CO₂ is transformed into water and methane, which can subsequently be used for oxygen generation or as propellant [1]. This technical guide examines the operational principles, system integrations, and experimental methodologies that underpin these essential technologies for carbon loop closure in advanced life support systems.

Fundamental Principles and System Architectures

The Sabatier Reaction: Core Reaction and Thermodynamics

The Sabatier reaction is a well-established catalytic process that converts carbon dioxide and hydrogen into methane and water. Its fundamental reaction is:

CO₂ + 4H₂ → CH₄ + 2H₂O ΔH° = −165 kJ/mol

This highly exothermic reaction requires a catalyst, typically nickel-based, and operates at elevated temperatures (150-400°C) [24]. The reaction's significance in life support systems is twofold: it removes metabolic CO₂ from the cabin atmosphere and produces valuable water. According to Le Chatelier's principle, in-situ water removal during the reaction shifts the equilibrium toward higher CO₂ conversion, a key principle exploited in advanced membrane Sabatier systems [24]. In the broader carbon loop, this methane can be utilized as rocket propellant for return journeys, while the water is recycled for human consumption or electrolysis to regenerate oxygen [24].

Electrolysis: Oxygen Generation and Hydrogen Production

Electrolysis systems complement Sabatier reactors by providing the hydrogen required for the methanation process while simultaneously generating breathable oxygen for crewed missions. Two primary electrolyzer technologies are relevant for space applications:

- Solid Oxide Electrolyzer Cells (SOEC): Employed in co-electrolysis of steam and CO₂ to produce syngas (H₂ + CO), which is subsequently methanated. SOEC-based systems demonstrate higher exergy and power-to-gas efficiencies compared to PEM systems [25].

- Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Electrolyzer Cells (PEMEC): Used for hydrogen production via water electrolysis, with the hydrogen then fed to a Sabatier reactor for methane production. PEMEC systems benefit from lower operational temperatures and pressures [25].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Electrolyzer Technologies for Space Applications

| Parameter | Solid Oxide Electrolyzer Cell (SOEC) | Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Electrolyzer Cell (PEMEC) |

|---|---|---|

| Process Type | Co-electrolysis of steam & CO₂ | Water electrolysis for H₂ production |

| Operating Temperature | High temperature (~700-850°C) | Low temperature (~50-100°C) |

| Efficiency | Higher exergy & power-to-gas efficiency | Lower efficiency but produces 1.2% more methane [25] |

| System Advantages | Lower electricity consumption; Direct CO₂ processing | Less purchase cost; Longer life cycle; Faster response |

| Integration | With methanation reactor | With Sabatier reactor |

| LCOE (Based on LHV) | 11% lower than PEMEC-based system [25] | Higher levelized cost of energy |

System Integration Architectures for Carbon Loop Closure

The integration of Sabatier reactors with electrolyzers creates synergistic systems that enhance overall carbon loop closure. Two prominent architectures have emerged:

SOEC with Methanation Reactor: This configuration relies on co-electrolysis of steam and carbon dioxide to produce syngas, which is subsequently converted to methane in a separate methanation unit. The system leverages the high efficiency of co-electrolysis, where the application of steam/CO₂ co-electrolysis demonstrates 54-66% enhancements in energy efficiencies compared to steam electrolysis alone for synthetic natural gas production [25].

PEMEC with Sabatier Reactor: In this architecture, a PEM electrolyzer produces hydrogen, which is then combined with CO₂ in a Sabatier reactor. While consuming more electricity relative to SOEC, this system benefits from PEMEC's lower purchase cost and longer lifecycle, making it attractive for certain mission profiles [25].

The integration of these systems has been successfully demonstrated in operational space hardware, notably in the Advanced Closed Loop System (ACLS) on the International Space Station. The ACLS incorporates a Carbon Dioxide Concentration Assembly (CCA), Oxygen Generation Assembly (OGA) electrolyzer, and Carbon Dioxide Reprocessing Assembly (CRA) Sabatier reactor, collectively capable of recycling 50% of recovered CO₂ and producing oxygen for three astronauts [1].

Figure 1: Carbon Loop Closure via Integrated Sabatier-Electrolysis System. This diagram illustrates the principal mass flows in a closed-loop life support system, showing how metabolic CO₂ and water are processed to recover breathable oxygen and produce water, thereby reducing resupply requirements.

Advanced System Designs and Performance Optimization

Membrane Sabatier Reactor Technology

Recent innovations have introduced membrane Sabatier systems that significantly enhance CO₂ conversion efficiency and system reliability. These systems integrate a catalytic reactor with a water vapor permselective membrane tube, typically composed of NaA zeolite, which continuously removes water vapor from the reaction zone [24]. This design leverages Le Chatelier's principle to drive the equilibrium toward higher methane yield while simultaneously addressing the challenge of water-caused catalyst sintering.

The performance advantages of membrane Sabatier systems are substantial:

- Enhanced CO₂ Conversion: At 300°C, membrane reactors achieve 99% CO₂ conversion with 100% CH₄ selectivity, exceeding thermodynamic equilibrium conversion calculated based on feed conditions [24].

- Superior Space-Time Yield: Membrane systems demonstrate a space-time yield (STY) of CH₄ reaching 1947 mmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹ with a space velocity of 342,857 mL gcat⁻¹ h⁻¹ at 300°C [24].

- Long-term Stability: The removal of H₂O mitigates H₂O-caused sintering of the catalyst, resulting in no obvious deactivation during long-term stability tests of 10 days at 240°C [24].

- Microgravity Compatibility: The membrane-based water separation eliminates the need for complex centrifugal phase separators required in microgravity environments, reducing system complexity, power consumption, and noise pollution [24].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Conventional vs. Membrane Sabatier Systems

| Performance Parameter | Conventional Sabatier System | Membrane Sabatier System |

|---|---|---|

| CO₂ Conversion at 300°C | ~80-85% (thermodynamic equilibrium) | 99% (exceeds equilibrium) [24] |

| CH₄ Selectivity at 300°C | >95% | 100% [24] |

| Space-Time Yield of CH₄ | Varies with conditions | 1947 mmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹ [24] |

| Long-term Stability | Gradual deactivation from H₂O exposure | No deactivation after 10 days [24] |

| Microgravity Adaptation | Requires centrifugal separator | Integrated membrane separation [24] |

| System Complexity | Higher due to separate gas-liquid separator | Simplified with integrated membrane [24] |

Multiple-Inlet Reactor Configurations for Biogas Upgrading

Distributed feeding strategies in multiple-inlet fixed bed reactors represent another advancement in Sabatier reactor design. Parametric studies demonstrate that biogas dosing through several side inlets significantly improves methane selectivity compared to conventional single-inlet feeding configurations [26]. The effect becomes more pronounced as the number of feeding points increases, with higher inlet counts leading to greater selectivity enhancements toward the desired CH₄ product [26].

Operational parameters significantly influence system performance in multiple-inlet configurations:

- Temperature and H₂:CO₂ Ratio: While these parameters influence selectivities as predicted at low conversions, space velocity (WHSV) emerges as the most critical factor for selectivities at higher conversion levels [26].

- Biogas Composition: Interestingly, modifying the biogas CH₄:CO₂ ratio in the broad range of 55-70 vol% methane shows no significant changes in reaction performance, indicating robust operation across varying feed compositions [26].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Membrane Sabatier System Fabrication and Testing

The development of advanced membrane Sabatier systems requires precise fabrication and characterization protocols. The following methodology outlines the key steps for creating and evaluating a membrane Sabatier system:

Membrane Synthesis Protocol:

- Support Preparation: Use a ceramic hollow tube support (50mm length, 12mm OD, 8mm ID, 500nm pore size) with a rough surface to enhance seed immobilization [24].

- Seed Solution Preparation: Synthesize NaA zeolite seeds (50-200nm) via hydrothermal synthesis, confirmed through EDX elemental mapping showing presence of Al, O, Na, and Si elements [24].

- Seed Coating: Employ dip-coating method by pre-heating support to 120°C, dipping into zeolite seed solution for 20 seconds, followed by drying at 100°C for 1 hour [24].

- Annealing Process: Anneal coated support at 180°C for 12 hours to chemically bond zeolite seeds to the support surface via dehydration of surface hydroxyl groups [24].

- Membrane Growth: Prepare synthesis solution with molar composition 1Al₂O₃:5SiO₂:50Na₂O:1000H₂O and crystallize on seeded support at 90°C for 20 hours [24].

- Membrane Characterization: Verify successful membrane formation through EDX elemental mapping, XRD profiling, and water contact angle measurements to confirm hydrophilicity [24].

Catalyst Preparation and Reactor Integration:

- Catalyst Synthesis: Prepare ZrO₂-supported Ni catalyst using impregnation method, followed by calcination and reduction steps to activate the catalyst [24].

- Reactor Assembly: Load catalyst into the annular space between the membrane tube and outer reactor shell, ensuring proper sealing for gas containment [24].

- System Testing: Evaluate performance across temperature range (150-300°C), space velocities (12,000-342,857 mL gcat⁻¹ h⁻¹), and H₂:CO₂ ratios (4:1), monitoring CO₂ conversion, CH₄ selectivity, and long-term stability [24].

Figure 2: Membrane Sabatier System Fabrication Workflow. This diagram outlines the key synthetic and assembly steps required to fabricate and validate a membrane Sabatier reactor, from initial support preparation through final performance testing.

Distributed Feeding Reactor Experimental Methodology

For investigating multiple-inlet reactor configurations, the following experimental approach provides comprehensive performance data:

Reactor Configuration Protocol:

- Reactor Setup: Configure fixed-bed reactor with multiple side inlets for distributed feeding of reactants, varying the number of inlets (N) to assess impact on selectivity [26].

- Parameter Variation: Systematically study operational parameters including dosage degree of reactants, temperature, H₂:CO₂ ratios, and biogas composition (CH₄:CO₂ ratios from 55:45 to 70:30) [26].

- Performance Metrics: Monitor CO₂ conversion, CH₄ selectivity, and CO selectivity at various space velocities to determine optimal conditions [26].