Classical vs Bayesian Methods for Sensor Reliability Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a systematic comparison of classical and Bayesian statistical methods for analyzing sensor reliability in biomedical and drug development applications.

Classical vs Bayesian Methods for Sensor Reliability Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of classical and Bayesian statistical methods for analyzing sensor reliability in biomedical and drug development applications. It covers foundational principles, from the frequentist interpretation of probability to Bayesian prior incorporation, and details methodological applications for success/no-success data and complex system modeling. The guide addresses common challenges like limited failure data and uncertainty quantification, offering optimization strategies such as hierarchical Bayesian models. Through validation frameworks and case studies, including wearables and reliability testing, it demonstrates the comparative advantages of each approach. Aimed at researchers and professionals, this review synthesizes key takeaways to inform robust sensor reliability practices in clinical research and therapeutic development.

Understanding the Core Principles: Frequency vs. Belief in Probability

In statistical analysis, the interpretation of probability itself is not a monolith but branches into two primary schools of thought: the classical frequency-based and the Bayesian belief-based paradigms. This distinction is not merely academic; it forms the foundational bedrock upon which statistical inference is built, influencing everything from experimental design in scientific research to decision-making in industrial reliability engineering. The classical, or frequentist, approach interprets probability as the long-run frequency of an event occurring in repeated, identical trials. In contrast, the Bayesian approach treats probability as a subjective measure of belief or uncertainty about an event, which can be updated as new evidence emerges [1] [2] [3]. Within the specific context of sensor reliability and degradation analysis—where data may be scarce, costly to obtain, or heavily censored—the choice between these paradigms dictates how parameters are estimated, risks are quantified, and maintenance strategies are ultimately formulated [4] [5]. This guide provides a structured, objective comparison of these two philosophical foundations, equipping researchers and engineers with the knowledge to select the appropriate tool for their specific reliability challenge.

Core Philosophical Divergence

The most fundamental difference between the classical and Bayesian paradigms lies in their very definition of probability. This philosophical schism leads to profoundly different approaches to statistical analysis and inference.

Classical (Frequentist) Probability: In this framework, probability is strictly defined as the limit of a relative frequency over a long series of repeated trials [2]. For example, a frequentist would state that the probability of a fair coin landing on heads is 0.5 because, in a vast number of tosses, the relative frequency of heads converges to 50%. This interpretation is objective; it is considered a property of the real world. Consequently, parameters of a system, such as the mean time to failure of a sensor, are treated as fixed, unknown constants. It does not make mathematical sense to assign a probability distribution to a fixed parameter [2] [3]. Statistical conclusions are based solely on the data observed in the current sample, and inferences are framed in terms of the long-run behavior of estimators and tests.

Bayesian Probability: Bayesian statistics interprets probability as a subjective degree of belief in a proposition or the state of the world [6] [3]. This belief is quantified on a scale from 0 to 1 and is personal, as it depends on the prior knowledge of the individual assessing the probability. This view allows for the assignment of probabilities to one-off events where long-run frequencies are meaningless. For instance, a Bayesian can assign a probability to the statement, "This specific sensor will function for more than 10,000 hours," based on available knowledge [7] [2]. In this framework, all unknown quantities, including parameters, are treated as random variables with probability distributions that represent our uncertainty about their true values. This belief is updated logically and mathematically as new data becomes available via Bayes' theorem.

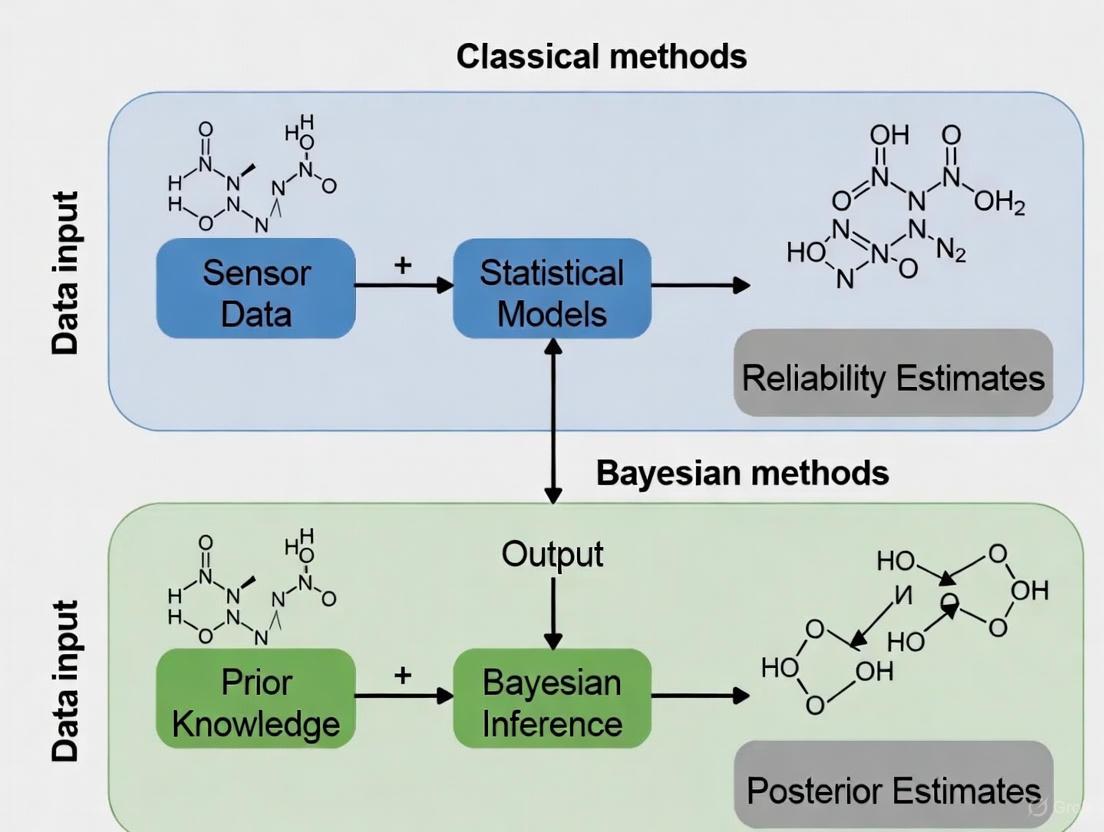

The following conceptual diagram illustrates the fundamental difference in how these two paradigms process information to reach a statistical conclusion.

Methodological Comparison and Experimental Protocols

The philosophical divergence translates into distinct methodologies for conducting analysis. The core of the Bayesian methodology is a mathematical framework for updating beliefs, while the frequentist method relies on comparing observed data to a sampling distribution.

The Bayesian Update Mechanism

At the heart of Bayesian statistics is Bayes' Theorem, which provides a formal mechanism for updating prior beliefs in light of new evidence [1] [6]. The formula is:

Posterior ∝ Likelihood × Prior

Or, more formally: π(θ | x) = [ p(x | θ) * π(θ) ] / p(x)

Where:

- π(θ | x) is the posterior distribution: the updated belief about the parameter θ after observing the data x.

- p(x | θ) is the likelihood function: the probability of observing the data x given a specific value of θ.

- π(θ) is the prior distribution: the belief about θ before observing the data x.

- p(x) is the marginal likelihood: a normalizing constant that ensures the posterior distribution is a valid probability distribution [6].

This process is iterative. The posterior distribution from one analysis can serve as the prior for the next update when new data is collected, creating a continuous learning cycle [1] [8].

Frequentist Hypothesis Testing Protocol

Frequentist methodology revolves around a structured procedure of null hypothesis significance testing (NHST). A typical experimental protocol is as follows [8] [9]:

- Define Hypotheses: Formulate a null hypothesis (H₀), often representing "no effect" (e.g., two sensor types have the same mean time to failure), and an alternative hypothesis (H₁).

- Choose Test Statistic: Select a statistic (e.g., t-statistic, F-statistic) that measures the evidence against H₀.

- Collect Data: Conduct an experiment or collect a sample.

- Calculate p-value: Compute the probability of observing a test statistic as extreme as, or more extreme than, the one calculated from the sample, assuming the null hypothesis is true.

- Make Decision: Reject or fail to reject H₀ by comparing the p-value to a pre-specified significance level (α, typically 0.05). This decision is based on the concept of "what if the experiment were repeated infinitely?" rather than the probability of the hypothesis itself [2] [9].

Side-by-Side Comparison of Key Elements

The table below summarizes the core components of both approaches for direct comparison.

| Element | Classical (Frequentist) Approach | Bayesian Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Probability Interpretation | Objective long-run frequency [2] [3] | Subjective degree of belief or uncertainty [6] [3] |

| Parameter Treatment | Fixed, unknown constants [2] | Random variables with probability distributions [2] [9] |

| Prior Information | Not incorporated formally into analysis [9] | Incorporated explicitly via the prior distribution [1] [6] |

| Primary Output | Point estimates (e.g., MLE), Confidence Intervals (CI), p-values [8] [3] | Full posterior distribution, Credible Intervals [1] [2] |

| Result Interpretation | A 95% CI means that in repeated sampling, 95% of such intervals will contain the true parameter [2]. | A 95% Credible Interval means there is a 95% probability the parameter lies within this interval, given the data [2]. |

| Handling Uncertainty | Uncertainty is quantified through the sampling distribution of the estimator [3]. | Uncertainty is quantified directly through the posterior distribution of the parameter [3]. |

Application in Sensor Reliability and Degradation Analysis

In reliability engineering, particularly for critical components like sensor systems, both paradigms offer tools for analyzing failure and degradation data, often under constraints like Type II censoring where a test is terminated after a pre-set number of failures [4].

Classical Reliability Methods

The classical approach to reliability, such as designing a failure-censored sampling plan for a lognormal lifetime model, involves calculating producer's and consumer's risks based solely on the observed failure data and the assumed distribution [4]. These methods use tools like:

- Accelerated Life Tests (ALT) and Design of Experiments (DOE) to understand how factors affect performance and predict failure distributions [5].

- Operating Characteristic (OC) Curves to evaluate the probability of accepting a batch given its quality level [4].

A key limitation is that when no failures occur during testing, classical methods struggle to quantify the probability of failure with precision, as they rely exclusively on the observed (zero) failure count [6].

Bayesian Reliability Methods

Bayesian methods are particularly powerful in reliability analysis due to their ability to incorporate prior knowledge—such as expert opinion, historical data, or simulation results—which is invaluable when failure data is scarce or expensive to obtain [6] [5].

- Incorporating Expert Opinion: A prior distribution for a sensor's reliability can be defined using a Beta distribution, which is flexible and conjugate to the binomial likelihood for success/failure data [6]. The parameters α and β can be chosen so that the prior's mean reflects the expert's belief about the reliability, and its variance reflects their confidence in that belief.

- Handling Zero-Failure Tests: Even if a new test yields zero failures, the Bayesian posterior distribution will be a blend of the prior and the new data. This allows for a quantitative estimate of reliability that is more informative than a classical estimate based on zero failures alone [6].

- Complex System Reliability: For a system composed of multiple subcomponents, a Bayesian approach combined with Monte Carlo algorithms can compute the posterior distribution of the entire system's reliability, even when only system-level test data is available [6].

The workflow below illustrates how a reliability engineer might apply the Bayesian approach to a component degradation problem, integrating multiple data sources.

Comparative Performance in a Case Study

A study on locomotive wheel-sets, a critical sensor-rich subsystem, compared classical and Bayesian semi-parametric degradation approaches for optimizing preventive maintenance. The study found that both approaches were useful tools for analyzing degradation data and supporting maintenance decisions. Notably, it concluded that the results from the different models can be complementary, providing a more robust foundation for decision-making [5]. The Bayesian approach, with its ability to model group-level effects (e.g., different bogies) through "frailties," offered a way to account for unobserved covariates that could influence degradation, a flexibility not as readily available in standard classical methods [5].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Analytical Components

When implementing the methodologies discussed, researchers rely on a set of conceptual and software-based "reagents" to conduct their analysis.

Conceptual Components for Reliability Analysis

| Component | Function | Frequentist Example | Bayesian Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability Model | Describes the random process generating the data. | Lognormal failure time distribution [4]. | Lognormal failure time with a prior on its parameters [4]. |

| Estimation Method | The algorithm or formula for deriving parameter values. | Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE). | Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) for posterior sampling [10] [9]. |

| Interval Estimate | Quantifies uncertainty about a parameter's value. | 95% Confidence Interval [4]. | 95% Credible Interval (Bayesian counterpart) [4]. |

| Risk Function | Evaluates the cost of incorrect decisions in sampling plans. | Producer’s and Consumer’s risk [4]. | Average and Posterior risks, which incorporate prior belief [4]. |

Software and Computational Tools

The practical application of these methods is enabled by statistical software and libraries.

- R: For frequentist analysis, R has extensive built-in functions and packages for survival analysis (

survivalpackage) and reliability. For Bayesian analysis, packages likerstan,brms, andbayesABprovide powerful MCMC sampling capabilities [9]. - Python: The

scipy.statsandlifelineslibraries support classical reliability and survival analysis. For Bayesian modeling,pymc3(nowpymc) andstan(viapystan) are industry standards [9]. - SAS: Procedures like

PROC LIFEREG(classical) andPROC MCMC(Bayesian) cater to both paradigms [9]. - Specialized Software: Platforms like JMP and Minitab offer workflows for both classical reliability and (increasingly) Bayesian analysis.

The choice between classical frequency-based and Bayesian belief-based probability is not about identifying a universally superior method, but about selecting the right tool for the specific research context [9].

- Opt for a Classical Approach when: Your analysis requires strict objectivity and standardization, you have large sample sizes, prior information is unavailable or unreliable, and your goal is straightforward hypothesis testing or compliance with regulatory standards that favor p-values and confidence intervals [9].

- Opt for a Bayesian Approach when: You have meaningful prior information (e.g., from experts, previous studies, or simulations), you are dealing with complex models or limited data (common in reliability testing of high-cost systems), you need to make sequential decisions or use adaptive designs, and when the direct probability statements of credible intervals are more intuitive for decision-makers [6] [9].

In practice, the lines are blurring. Many modern analysts advocate for a pragmatic, problem-first perspective, leveraging the strengths of both paradigms. For sensor reliability research, where data is often censored and system complexity is high, the Bayesian paradigm offers a compelling framework for incorporating all available information to make robust inferences about system lifetime and to optimize maintenance strategies.

In the field of sensor reliability analysis and scientific research, two primary statistical paradigms exist for dealing with uncertainty and drawing inferences from data: the classical (frequentist) approach and the Bayesian approach. The fundamental difference between these methodologies hinges on how they treat probability and uncertainty. Classical statistics assumes that probabilities are the long-run frequency of specific events occurring in a repeated series of trials and treats model parameters as fixed, unknown quantities [11] [1]. In contrast, Bayesian statistics provides a framework for updating prior beliefs or knowledge with new evidence, treating probabilities as a measure of belief in a statement's truth and model parameters as random variables [6] [1].

Bayesian methods have gained significant traction in modern research, including sensor reliability, aerospace systems, and drug development, due to their ability to formally incorporate prior knowledge, handle complex models, and provide intuitive probabilistic results [12] [13] [14]. This guide explores the three core components of Bayesian analysis—priors, likelihoods, and posteriors—and provides a structured comparison with classical methods, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to research professionals.

The Core Components of Bayesian Analysis

The Bayesian framework is built upon a recursive process of belief updating, formalized by Bayes' theorem. This process integrates three core components to produce a posterior distribution, which encapsulates all knowledge about an unknown parameter after observing data.

Prior Distribution (π(θ)): Quantifying Pre-Existing Knowledge

The prior distribution represents the initial belief about the plausibility of different values of an unknown parameter (θ) before considering the new evidence from the current data [1] [15]. Priors are the cornerstone of the Bayesian approach, allowing for the formal integration of expert opinion, historical data, or results from simulations into the analysis [6] [12].

- Informative Priors: These are used when substantial prior knowledge exists. For example, in reliability engineering, a prior for a failure rate might be constructed from handbook estimates or previous experiments on similar components [15].

- Non-Informative (or Vague) Priors: These are used when prior knowledge is limited, aiming to exert minimal influence on the posterior results. A common example is the uniform distribution, which assigns equal probability to all possible parameter values [6] [15].

- Conjugate Priors: A special class of priors chosen for mathematical convenience, as they yield a posterior distribution that belongs to the same family as the prior. A classic example is using a Beta prior for a binomial likelihood, which results in a Beta posterior [6] [14].

Table 1: Common Conjugate Prior Distributions

| Likelihood Model | Parameter | Conjugate Prior | Posterior Hyperparameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binomial | Probability of success (θ) | Beta(α, β) | Alpha (α) + successes, Beta (β) + failures [6] |

| Exponential | Failure rate (λ) | Gamma(α, β) | Alpha (α) + number of failures, Beta (β) + total time [15] |

| Normal (Known Variance) | Mean (μ) | Normal(μ₀, σ₀²) | A weighted average of prior mean and sample mean [16] |

In practice, for a reliability parameter like the probability of a sensor surviving a test (θ), an engineer might choose a Beta prior. Selecting parameters α = 2 and β = 10 expresses a prior belief that θ is likely low, while α = 20 and β = 30 would express a similar prior mean but with much higher confidence [6].

Likelihood (p(x\|θ)): The Weight of the New Evidence

The likelihood function represents the probability of observing the collected data given a specific value of the parameter θ [1]. It quantifies how well different parameter values explain the observed data. In Bayesian analysis, the likelihood is the engine that updates the prior, shifting belief towards parameter values that make the observed data more probable.

The choice of likelihood function is determined by the nature of the data and the underlying process being modeled. Common likelihoods in reliability and sensor research include:

- Bernoulli/Binomial Likelihood: For success/failure or pass/fail data [6].

- Exponential Likelihood: For modeling time-to-failure data with a constant failure rate [15].

- Weibull Likelihood: A more flexible model for time-to-failure data that can account for increasing, decreasing, or constant failure rates [11].

- Normal Likelihood: For continuous measurement data, such as sensor output readings [14].

Posterior Distribution (π(θ\|x)): The Updated Belief

The posterior distribution is the final output of Bayesian analysis. It combines the prior distribution and the likelihood via Bayes' theorem to produce a complete probability distribution for the parameter θ after seeing the data [6] [1]. It is the solution to the problem and contains all information needed for inference.

Bayes' theorem is mathematically expressed as: [ \pi(\theta \mid \mathbf{x}) = \frac{p(\mathbf{x} \mid \theta) \pi(\theta)}{\int p(\mathbf{x} \mid \theta) \pi(\theta) d\theta} \propto p(\mathbf{x} \mid \theta) \pi(\theta) ] In words, the posterior is proportional to the likelihood times the prior [6] [14] [15]. The denominator is a normalizing constant ensuring the posterior distribution integrates to one.

The posterior distribution is the basis for all statistical conclusions, allowing for direct probability statements about parameters. For instance, one can calculate the probability that a sensor's reliability exceeds 0.99 or that the mean time between failures falls within a specific interval [6].

Figure 1: The core workflow of Bayesian inference, showing how the prior and likelihood are combined via Bayes' Theorem to form the posterior distribution.

Experimental Protocols: Implementing Bayesian Analysis in Practice

Applying Bayesian methods to real-world research problems, such as sensor reliability analysis, involves a structured process. The following protocols, drawn from recent research, detail the key methodologies.

Protocol 1: Bayesian Reliability Estimation for Systems with Sparse Data

This protocol is designed for situations with limited physical test data, common in high-cost or high-reliability systems like aerospace sensors [6] [12].

- Formulate the Prior: Elicit an informative prior distribution for the system's reliability (θ). This can be based on expert opinion, subsystem-level test data, or high-fidelity simulations. A Beta distribution is often used for its conjugacy with binomial data. The parameters (α, β) are set to reflect the prior mean (α/(α+β)) and confidence (higher α+β implies higher confidence) [6].

- Define the Likelihood: Conduct a limited number of system-level tests (n), recording the number of successes (x). The likelihood is a Binomial distribution: p(x \| θ) = C(n, x) * θˣ * (1-θ)ⁿ⁻ˣ [6].

- Compute the Posterior: With a Beta(α, β) prior and binomial likelihood, the posterior is a Beta(α + x, β + n - x) distribution. This provides a full probabilistic description of system reliability after testing [6].

- Draw Inference: Calculate posterior summaries such as the mean, median, and 95% credible interval. The probability of exceeding a reliability threshold (e.g., P(θ > 0.95)) can be directly computed from the posterior [6].

Protocol 2: Hierarchical and Multi-Fidelity Data Fusion for Aerospace Systems

This advanced protocol, such as the Integrated Hierarchical Fusion for Mission Reliability Prediction (IHF-MRP), addresses the challenge of integrating heterogeneous data sources (e.g., sparse physical tests and abundant simulation data) for complex, coupled systems [12].

- Model Subsystem Interactions: Instead of relying on predefined reliability block diagrams, establish a data-driven probabilistic mapping from subsystem performance signatures (e.g., sensor anomalies, actuator latency) to overall mission outcomes using a Dirichlet-multinomial model [12].

- Fuse Multi-Fidelity Data: Develop an adaptive weighting mechanism to combine data from different sources (e.g., all-digital simulations, hardware-in-the-loop, flight tests). This mechanism uses a robust sparse-sample Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence estimator to quantify and account for data fidelity gaps [12].

- Bayesian Updating and Learning: Continuously update the hierarchical model as new test data becomes available. The framework not only predicts mission reliability but also identifies the primary performance drivers and failure modes from the heterogeneous data [12].

Protocol 3: Bayesian Linear Profiling for Chemical Gas Sensor Monitoring

This protocol demonstrates the application of Bayesian methods for quality control and process monitoring in sensor manufacturing [14].

- Data Collection via Neoteric Ranked Set Sampling (NRSS): Collect sensor calibration data using an efficient NRSS scheme instead of simple random sampling to improve the representativeness of the data [14].

- Define Profile Model and Priors: Model the relationship between sensor input and output as a linear profile (a simple linear regression). Specify prior distributions for the profile parameters: intercept, slope, and error variance [14].

- Construct Bayesian Control Charts: Calculate the posterior distributions of the profile parameters. Use these posteriors to construct Bayesian Shewhart, CUSUM, or EWMA control charts. These charts monitor the stability of the sensor's calibration profile over time [14].

- Monitor and Detect Shifts: The process is considered out-of-control if the posterior probability of a parameter shift exceeds a predefined threshold. Bayesian charts have been shown to detect process disturbances more efficiently than their classical counterparts [14].

Comparative Analysis: Bayesian vs. Classical Methods

The following tables provide a structured comparison of classical and Bayesian statistical methods, summarizing their key differences, performance, and applications.

Table 2: Conceptual and Methodological Comparison

| Aspect | Classical (Frequentist) Approach | Bayesian Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Definition of Probability | Long-run frequency of an event [6] [1] | Degree of belief that a statement is true [6] [1] |

| Treatment of Parameters | Fixed, unknown constants [11] | Random variables with probability distributions [11] |

| Use of Prior Information | Not directly incorporated | Formally incorporated via the prior distribution [15] |

| Primary Output | Point estimate and confidence interval [11] | Full posterior distribution [16] |

| Interpretation of Uncertainty | A 95% CI means: with repeated sampling, 95% of such intervals will contain the true parameter. It does not quantify the probability of the parameter [1]. | A 95% Credible Interval means: there is a 95% probability that the true parameter lies within this interval, given the data and prior [16]. |

Table 3: Performance Comparison in Reliability & Sensor Applications

| Metric | Classical Methods | Bayesian Methods | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small-Sample Performance | Struggles with sparse data; MLE can be unstable or undefined (e.g., with zero failures) [6] [11]. | Excels by leveraging prior information; provides meaningful estimates even with no observed failures [6] [11]. | Simulation studies show Bayesian methods provide more stable estimates with n < 30 [11]. |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Relies on asymptotic approximations (e.g., normal approximation for MLE) which can be poor with small samples [15]. | Provides exact, finite-sample uncertainty from the posterior distribution; more consistent [15]. | In failure-censored sampling, Bayesian credible intervals provided more robust coverage than classical intervals under small samples [4]. |

| Computational Complexity | Generally computationally efficient (e.g., MLE) [11]. | Can be computationally intense, requiring MCMC or variational inference for complex models [11] [16]. | Noted as a key challenge, especially for large datasets and complex hierarchical models [16]. |

| Handling Complex Systems | Limited by assumptions of subsystem independence and binary states [12]. | Superior for modeling coupled interactions and continuous performance signatures via hierarchical models [12]. | IHF-MRP framework successfully predicted missile intercept reliability by fusing multi-fidelity data [12]. |

| Process Monitoring | Assumes process parameters are fixed, which is less practical under parameter uncertainty [14]. | Efficiently handles parameter uncertainty; Bayesian control charts show faster detection of process shifts [14]. | Bayesian EWMA charts for linear profiles detected smaller shifts more quickly than classical charts in a sensor monitoring case study [14]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Bayesian Reliability Experiments

For researchers implementing the protocols described, the following "reagents" are essential computational and methodological components.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Bayesian Analysis

| Reagent Solution | Function in the Analysis |

|---|---|

| Beta Distribution | A versatile conjugate prior and posterior model for probabilities and reliabilities bounded between 0 and 1 [6] [4]. |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) | A class of algorithms (e.g., Metropolis-Hastings, Gibbs Sampling) used to generate samples from complex posterior distributions when analytical solutions are intractable [11] [15]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Prior | A flexible prior used to model unknown functions or spatial/temporal correlations, such as inferring a plasma current density distribution from magnetic sensor data [17]. |

| Dirichlet-Multinomial Model | A hierarchical model used to establish probabilistic mappings from multiple discrete inputs (e.g., subsystem performance states) to categorical outcomes (e.g., mission success/failure) [12]. |

| Kullback-Leibler (KL) Divergence Estimator | An information-theoretic measure used in multi-fidelity data fusion to quantify the discrepancy between data sources and compute adaptive weights [12]. |

Figure 2: A data fusion workflow for complex system reliability prediction, integrating diverse data sources within a hierarchical Bayesian model.

The choice between classical and Bayesian methods is not merely a technicality but a fundamental decision that shapes the approach to uncertainty in research. Classical statistics offers computational efficiency and objectivity in data-rich environments. However, the Bayesian paradigm, with its core components of priors, likelihoods, and posteriors, provides a powerful, coherent framework for updating beliefs with evidence.

As demonstrated in sensor reliability, aerospace, and pharmaceutical applications, the strengths of Bayesian methods are particularly evident when dealing with complex systems, limited data, and the need to formally incorporate diverse sources of information. The ability to provide direct probabilistic interpretations and to seamlessly integrate multi-fidelity data makes Bayesian analysis an indispensable tool for modern researchers and scientists striving to make robust inferences under uncertainty.

Analytical Frameworks for Sensor Reliability

In biomedical applications, from implantable devices to wearable sensors, ensuring long-term reliability is paramount for accurate diagnosis and effective patient monitoring. The analysis of sensor reliability often hinges on interpreting time-to-failure data, which is frequently censored; meaning the complete failure time for all units is not always observable within a study period. Statistical methods are essential to draw valid inferences from such incomplete data. Two predominant philosophical frameworks exist for this analysis: the Classical (or Frequentist) approach and the Bayesian approach.

The core distinction lies in how each framework handles uncertainty and prior knowledge. Classical statistics treats parameters as fixed unknown constants to be estimated solely from the observed data. In contrast, Bayesian statistics formally incorporates prior knowledge or beliefs about parameters, which are updated with observed data to form a posterior distribution [1]. This fundamental difference shapes their application in biomedical sensor reliability, influencing how study designs are structured, risks are quantified, and conclusions are drawn for critical decision-making in drug development and clinical research.

Comparative Analysis: Classical versus Bayesian Methods

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of the Classical and Bayesian approaches as applied to reliability assessment.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Classical and Bayesian Methods for Reliability Analysis

| Feature | Classical (Frequentist) Approach | Bayesian Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophical Basis | Probabilities represent long-run frequencies of events in repeated trials [1]. | Probabilities represent a degree of belief or certainty about an event, which is updated as new data arrives [1]. |

| Parameter Treatment | Parameters (e.g., mean failure rate) are fixed, unknown constants. | Parameters are random variables described by probability distributions. |

| Use of Prior Information | Does not formally incorporate prior knowledge or beliefs. | Explicitly incorporates prior knowledge via a "prior distribution," which is updated with data to form the "posterior distribution" [1]. |

| Output & Interpretation | Provides point estimates and confidence intervals. A 95% confidence interval means that if the experiment were repeated many times, 95% of such intervals would contain the true parameter. | Provides a full posterior probability distribution for parameters. A 95% credible interval means there is a 95% probability the true parameter lies within that interval, given the data and prior. |

| Computational Complexity | Generally less computationally intensive (e.g., Maximum Likelihood Estimation). | Often more computationally intensive, relying on Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods for complex models [1]. |

The practical performance of these methods has been quantitatively compared in various studies. Research on the Weighted Lindley distribution under unified hybrid censoring schemes, relevant for survival and reliability data, demonstrated that Bayesian estimators consistently yielded lower Mean Squared Errors (MSEs) than classical Maximum Likelihood Estimators (MLEs). Furthermore, the Bayesian credible intervals were generally narrower than the frequentist confidence intervals [18]. Similarly, in the context of optimizing failure-censored sampling plans for lognormal lifetime models, Bayesian methods were found to provide more robust designs, especially when prior information is uncertain [4].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison from Reliability Studies

| Study Context | Performance Metric | Classical Method | Bayesian Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted Lindley Distribution under Censoring [18] | Estimator Accuracy (Mean Squared Error) | Higher | Lower |

| Weighted Lindley Distribution under Censoring [18] | Interval Estimate Width | Wider | Narrower |

| Locomotive Wheel-Set Reliability Analysis [5] | Utility for Preventive Maintenance | Effective, uses ALT & DOE | Effective, uses semi-parametric models with Gamma frailties |

| Lognormal Sampling Plans [4] | Robustness under Parameter Uncertainty | Greater sensitivity to changes | More robust designs |

Experimental Protocols for Method Comparison

To objectively compare classical and Bayesian methods in a biomedical sensor context, a structured experimental and analytical protocol is essential. The following workflow outlines the key stages, from data collection to inference, highlighting where the methodological approaches diverge.

Core Experimental Components

The reliability analysis of biomedical sensors relies on several key components and methodologies, as evidenced by real-world studies and reviews.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Sensor Reliability Analysis

| Component / Solution | Function in Reliability Analysis | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Unified Hybrid Censoring Scheme (UHCS) | A versatile framework integrating multiple censoring strategies to efficiently collect and analyze lifetime data under resource constraints [18]. | Used to evaluate the Weighted Lindley distribution for modeling sensor lifetime data, allowing experiments to be terminated based on either a pre-set time or a pre-set number of failures [18]. |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) | A computational algorithm used in Bayesian analysis to sample from the complex posterior probability distribution of parameters, enabling inference [5]. | Employed in a Bayesian semi-parametric degradation approach for locomotive wheel-sets to establish lifetime using degradation data and explore the influence of unobserved covariates [5]. |

| Piecewise Constant Hazard Model with Gamma Frailties | A semi-parametric Bayesian survival model that does not assume a specific shape for the hazard function over time. Frailties account for unobserved heterogeneity or dependencies between units (e.g., sensors on the same device) [5]. | Applied to model the dependency of wheel-set degradation based on their installed position (bogie) on a locomotive, revealing that the specific bogie had more influence on lifetime than the axle or side [5]. |

| Bayesian Structural Time Series (BSTS) | A framework for modeling time series data to evaluate the causal impact of an intervention by constructing a counterfactual (what would have happened without the intervention) [19]. | Proposed for analyzing mobile health and wearable sensor data to quantify the impact of a health intervention (e.g., exercise on blood glucose) by correcting for complex covariate structures and temporal patterns [19]. |

Detailed Protocol: A Case Study in Method Comparison

The following protocol is adapted from a comparative study on the Weighted Lindley distribution, which is directly applicable to modeling sensor lifetime data [18].

Study Design and Data Collection:

- A sample of

nidentical biomedical sensors is placed on a life-testing platform. - A Unified Hybrid Censoring Scheme (UHCS) is implemented. This means the test will terminate at a random time

T* = min{max(X_{m}, T1), T2}, whereT1andT2are pre-set times (T1 < T2), andX_{m}is the time of them-th failure. This scheme efficiently combines Type-I and Type-II censoring.

- A sample of

Classical (Frequentist) Analysis:

- Parameter Estimation: The Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) method is used. The likelihood function is constructed based on the observed censored data, and numerical optimization techniques (e.g., Newton-Raphson) are applied to find the parameter values that maximize this function.

- Interval Estimation: Asymptotic Confidence Intervals for the parameters are derived based on the observed Fisher information matrix. This relies on the large-sample property that MLEs are normally distributed.

Bayesian Analysis:

- Prior Selection: Informative or non-informative prior distributions (e.g., Gamma, Uniform) are specified for the model parameters, reflecting prior knowledge or belief about their values before the experiment.

- Posterior Computation: The posterior distribution is computed by combining the prior distributions with the likelihood of the observed data using Bayes' Theorem. Since an analytical solution is often intractable, Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods like the Gibbs sampler or Metropolis-Hastings algorithm are used to generate samples from the posterior distribution.

- Inference: Point estimates (e.g., posterior mean or median) and Bayesian Credible Intervals (e.g., Highest Posterior Density intervals) are computed directly from the MCMC samples.

Performance Comparison:

- A Monte Carlo simulation is run, repeating the above process hundreds or thousands of times to compare the methods.

- Key performance metrics are calculated and compared, including:

- Mean Squared Error (MSE): Average squared difference between the estimated and true parameter values. Lower MSE indicates better accuracy.

- Interval Width: The average width of the confidence/credible intervals. Narrower intervals indicate greater precision.

- Coverage Probability: The proportion of times the confidence/credible interval contains the true parameter value.

This structured protocol allows for a direct, quantitative comparison of the robustness and efficiency of classical versus Bayesian methods in a controlled, yet realistic, biomedical sensor testing environment.

The comparison between classical and Bayesian methods for biomedical sensor reliability is not about declaring a universal winner. Each offers distinct advantages. The Bayesian approach, with its ability to formally incorporate prior information and provide intuitive probabilistic outputs, often leads to more precise estimates and robust designs, particularly with limited data or well-understood failure mechanisms [18] [4]. The Classical approach remains a powerful, straightforward tool, especially when prior knowledge is absent or when its objectivity is required for regulatory purposes.

Future research will be shaped by several key trends. The rise of digital twins—virtual patient models dynamically updated with real-time sensor data—for precision medicine will place new demands on VVUQ (Verification, Validation, and Uncertainty Quantification) processes. Here, Bayesian frameworks are uniquely positioned to continuously update model predictions and quantify uncertainty in a clinically actionable way [20]. Furthermore, the integration of ensemble learning and AI with traditional reliability models promises to enhance the classification and prediction of complex failure patterns from multi-modal sensor data [21] [19]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice of method will ultimately depend on the specific application, the quality of prior knowledge, and the required form of inference for decision-making.

The Role of Uncertainty in Sensor Data and Model Predictions

In modern technological systems, from autonomous vehicles to industrial manufacturing, the reliability of sensor data is paramount for ensuring proper functioning and safety [22]. However, sensor data is inherently afflicted by various sources of uncertainty that can compromise the accuracy and reliability of model predictions. These uncertainties become particularly critical in applications like medical device monitoring, pharmaceutical manufacturing, and drug development, where decision-making depends on highly accurate sensor readings. The random deviations present in sensor measurements contribute significantly to overall measurement uncertainty, presenting substantial challenges for data interpretation and model performance [23].

The field of reliability engineering has developed two principal statistical paradigms to address these challenges: classical (frequentist) and Bayesian inference methods [11]. Classical approaches treat model parameters as fixed but unknown quantities and use techniques like maximum likelihood estimation to draw inferences from observed data. In contrast, Bayesian methods treat parameters as random variables with associated probability distributions, allowing for the incorporation of prior knowledge which is updated through Bayes' theorem as new data becomes available [11]. Understanding the strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications of each framework is essential for researchers and professionals working with sensor-derived data in scientific and industrial contexts.

Theoretical Foundations of Uncertainty

Typology of Uncertainty

In supervised machine learning and predictive modeling, uncertainty is broadly categorized into two primary types: aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty [24]. Aleatoric uncertainty refers to the inherent randomness or noise in the data generation process itself. This type of uncertainty is irreducible, meaning it cannot be diminished by collecting more data or improving models. In sensor systems, aleatoric uncertainty manifests as sensor noise, measurement errors, motion blur in cameras, or signal quantization errors [25]. For example, a camera may produce blurred images due to rapid movement, while radar systems exhibit signal noise from electrical interference.

Epistemic uncertainty, conversely, stems from incomplete knowledge or information about the system being modeled [24]. This includes limitations in the model structure, insufficient training data, or lack of coverage of all possible operational states. Unlike aleatoric uncertainty, epistemic uncertainty can be reduced by gathering more data, improving model architectures, or incorporating additional domain knowledge [25]. A practical example includes a self-driving car encountering unfamiliar weather conditions or a drone discovering previously unobserved objects in its environment.

Multiple factors contribute to uncertainty in sensor-based systems, each requiring specific mitigation strategies:

Sensor Noise and Bias: Every sensor introduces measurement noise, which is unpredictable and random in nature [25]. This includes phenomena like motion blur in cameras, signal noise in radar systems, and quantization errors in image sensors. Bias represents a systematic shift in measurements that affects all readings consistently in one direction.

Temporal and Spatial Misalignment: In multi-sensor systems, different sensors may capture measurements at varying times and from different physical locations [25]. A camera might capture an image at one moment, while a radar scan occurs milliseconds later. Without proper synchronization and alignment, this can lead to positional discrepancies that introduce uncertainty in object localization.

Data Association Errors: When multiple objects move within a sensor's field of view, correctly associating sensor readings with specific objects becomes challenging [25]. This problem is exacerbated when sensors have different resolutions or when objects occupy overlapping areas in the sensor data.

Environmental Factors: Extreme conditions during manufacturing or operation, such as vibration, temperature fluctuations, and humidity variations, can degrade sensor performance and introduce uncertainty into the data [23].

Classical Methods for Uncertainty Quantification

Fundamental Principles

Classical (frequentist) approaches to uncertainty quantification treat model parameters as fixed but unknown quantities that must be estimated from observed data [11]. These methods rely heavily on statistical techniques such as maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), confidence intervals, and hypothesis testing to draw inferences about the underlying system. The classical framework assumes that parameters have true values that remain constant, and any uncertainty arises solely from sampling variability rather than inherent randomness in the parameters themselves.

In reliability engineering, classical methods have served as the cornerstone for decades, with techniques like Non-Homogeneous Poisson Processes (NHPP) modeling time-varying failure rates and the Kaplan-Meier estimator handling censored data in reliability testing [11]. These approaches are computationally efficient, widely implemented in industrial standards, and provide straightforward interpretation through point estimates and confidence intervals.

Implementation Approaches

Confidence Intervals for Uncertainty Quantification: A prominent classical approach for sensor data-driven prognosis utilizes confidence intervals based on z-scores to quantify prediction uncertainty [26]. The confidence interval is calculated as:

$$ CI = \bar{X} \pm z \cdot \frac{\omega}{\sqrt{n}} $$

where $\bar{X}$ represents the sample mean, $z$ is the z-score associated with a chosen confidence level (e.g., 2.5758 for 99% confidence), $\omega$ signifies the standard deviation, and $n$ is the number of data points [26]. The interval width ($CI_w = 2z \cdot \frac{\omega}{\sqrt{n}}$) serves as a direct metric for uncertainty, with narrower intervals indicating higher confidence in predictions [26].

Experimental Protocol for Vibration Signal Analysis: In a practical implementation for bearing degradation monitoring, researchers generated synthetic vibration signals mimicking real-world sensor data [26]. The mathematical model incorporated an exponentially growing sinusoidal pattern with additive Gaussian noise and outliers:

$$ X = A \sin(2\pi f T) \cdot e^{-\lambda \bar{T}} + \mu + \rho $$

where $A$ represents amplitude, $f$ is oscillation frequency, $\lambda$ denotes the decay rate, $\mu$ is Gaussian noise, and $\rho$ represents outliers [26]. The health index $Y$ was modeled as a linearly decreasing function: $Y_i = 1 - \frac{i}{n}$ for $i = 1, 2, ..., n$.

The experimental workflow involved:

- Time vector formulation with a predetermined number of points

- Generation of composite sensor signals with exponential decay oscillations

- Introduction of Gaussian noise and outliers to simulate real measurement conditions

- Health index calculation representing progressive system degradation

- Data splitting using an 80-20 train-test validation approach

- Model training with optimization targeting confidence interval width minimization [26]

Bayesian Methods for Uncertainty Quantification

Fundamental Principles

Bayesian methods adopt a fundamentally different perspective by treating unknown parameters as random variables with associated probability distributions rather than fixed quantities [11]. This framework incorporates prior knowledge—such as expert opinion, historical data, or domain expertise—which is then updated with observational data through Bayes' theorem to form posterior distributions. The Bayesian approach is particularly valuable in scenarios involving limited data, expert judgment, or the need for probabilistic decision-making under uncertainty [11].

The mathematical foundation of Bayesian inference rests on Bayes' theorem:

$$ P(\theta|D) = \frac{P(D|\theta) \cdot P(\theta)}{P(D)} $$

where $P(\theta|D)$ represents the posterior distribution of parameters $\theta$ given data $D$, $P(D|\theta)$ is the likelihood function, $P(\theta)$ is the prior distribution encapsulating previous knowledge, and $P(D)$ serves as the normalizing constant.

Implementation Approaches

Bayesian Model Fusion: This technique leverages Bayesian probability theory to fuse predictions from multiple models, creating a probabilistic ensemble that enhances predictive accuracy while quantifying uncertainty [27]. The implementation involves calculating likelihoods from individual model predictions, applying prior weights to each model, and computing posterior probabilities through weighted aggregation [27].

A practical implementation for image classification using MNIST data demonstrated this approach with three different models: Support Vector Classifier (SVC), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), and Logistic Regression (LR) [27]. The Bayesian fusion process computed posteriors as:

$$ \text{posteriors} = \sum(\text{noisy_likelihoods} \cdot \text{priors}[:, \text{np.newaxis}, \text{np.newaxis}]) $$

The uncertainty was then quantified using entropy calculated from the posterior probabilities: $-\sum(\text{probs} \cdot \log_2(\text{probs} + 10^{-15}))$ [27].

Bayesian Reliability Estimation: For reliability testing with Type II censoring, Bayesian methods provide robust frameworks for estimating system reliability parameters [4]. In this context, the defect rate $p$ is treated as a random variable following a Beta distribution, which serves as a conjugate prior to the binomial distribution, simplifying posterior computation [4]. The approach is particularly valuable when traditional acceptance sampling assumes fixed defect rates, while in reality, defect rates may vary across batches due to material differences, processing conditions, or environmental factors.

Comparative Analysis: Classical vs. Bayesian Methods

Performance Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Classical and Bayesian Methods for Sensor Reliability Analysis

| Aspect | Classical Methods | Bayesian Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Treatment | Parameters as fixed, unknown quantities [11] | Parameters as random variables with probability distributions [11] |

| Prior Knowledge | Does not incorporate prior knowledge | Explicitly incorporates prior knowledge through prior distributions [11] |

| Uncertainty Representation | Confidence intervals based on hypothetical repeated sampling [26] | Posterior distributions and credible intervals with probabilistic interpretation [27] |

| Computational Complexity | Generally computationally efficient [11] | Can become computationally intensive, especially with many models and data points [27] |

| Data Requirements | Relies on large sample sizes for stable inferences [11] | Effective with small sample sizes, leveraging prior information [11] |

| Handling of Censored Data | Uses specialized estimators (e.g., Kaplan-Meier) [11] | Naturally incorporates censoring through likelihood construction [4] |

| Interpretation | Straightforward interpretation of point estimates and confidence intervals [11] | Probabilistic interpretation directly addressing parameter uncertainty [27] |

Table 2: Experimental Results from Vibration-Based Prognosis Study [26]

| Metric | LSTM (RMSE Objective) | LSTM (Uncertainty Quantification Objective) |

|---|---|---|

| Confidence Interval Width | Wider and less stable intervals | Tighter and more stable confidence intervals |

| Prediction Residuals | Larger deviations from true values | Closer to zero on average |

| Uncertainty Estimation | Less reliable uncertainty estimates | Improved uncertainty estimation and model calibration |

| Robustness | More sensitive to data variations | Enhanced robustness against data variations |

Case Study: Reliability Testing with Type II Censoring

A comparative study on failure-censored sampling plans for lognormal lifetime models examined both classical and Bayesian risks in optimal experimental design [4]. The research focused on how variations in prior distributions, specifically beta distributions for defect rates, influence producer's risk, consumer's risk, and optimal sample size.

The experimental protocol involved:

- System Modeling: Lifetime $T$ of electronic components followed a two-parameter lognormal distribution, with logarithmic lifetime $X = \log(T)$ following a normal distribution with parameters $(\mu, \sigma)$ [4]

- Censoring Mechanism: Tests were terminated after a predetermined number of failures ($m$), with censoring rate defined as $q = 1 - \frac{m}{n}$ [4]

- Parameter Estimation: For classical methods, maximum likelihood estimation was used, while Bayesian approaches employed Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) techniques for posterior sampling [4]

- Risk Assessment: Both producer's risk (rejecting conforming products) and consumer's risk (accepting non-conforming products) were evaluated under both frameworks [4]

The results demonstrated that Bayesian methods generally provided more robust experimental designs under uncertain prior information, while classical methods exhibited greater sensitivity to parameter changes [4]. Bayesian approaches allowed for more effective balancing of sample size constraints with risk control objectives, particularly in small-sample scenarios common in reliability testing of high-reliability components.

Methodological Workflows

Classical Method Workflow for Sensor Reliability

Classical Reliability Analysis Workflow

Bayesian Method Workflow for Sensor Reliability

Bayesian Reliability Analysis Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Sensor Reliability Experiments

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R, Python (Scikit-learn, PyMC3, TensorFlow Probability) | Implementation of classical and Bayesian statistical models for reliability analysis [27] [26] |

| Sensor Simulation Tools | Large Eddy Simulation (LES), Computational Aeroacoustics (CAA) | Generating synthetic sensor data for method validation under controlled conditions [28] |

| Reliability Testing Platforms | Accelerated Life Testing Systems, Environmental Chambers | Subjecting sensors to controlled stress conditions to collect failure time data [11] |

| Uncertainty Quantification Libraries | TensorFlow Uncertainty, Uber Pyro, Stan | Implementing Bayesian neural networks, Monte Carlo dropout, and probabilistic deep learning models [27] [26] |

| Data Annotation Platforms | Human-in-the-Loop annotation systems | Providing high-quality labeled data for training uncertainty-aware models [25] |

| Optimization Frameworks | Bayesian Optimization, Hyperopt | Tuning hyperparameters of machine learning models with uncertainty considerations [26] |

The comparative analysis of classical and Bayesian methods for sensor reliability analysis reveals distinct advantages and limitations for each approach. Classical methods offer computational efficiency, straightforward interpretation, and well-established implementation protocols, making them suitable for applications with abundant data and minimal prior knowledge [11]. Their reliance on large-sample properties and fixed-parameter assumptions, however, can limit their effectiveness in small-sample scenarios or when incorporating expert judgment is essential.

Bayesian methods excel in contexts characterized by limited data, the need to incorporate prior knowledge, and requirements for probabilistic interpretation of parameters [11] [4]. The ability to provide full posterior distributions rather than point estimates offers more comprehensive uncertainty quantification, particularly valuable in critical applications where understanding confidence in predictions is as important as the predictions themselves [27]. The computational demands of Bayesian methods and the challenge of specifying appropriate prior distributions remain practical considerations for implementation.

For researchers and professionals in drug development and pharmaceutical applications, the choice between classical and Bayesian approaches should be guided by specific application requirements, data availability, and decision-making context. Bayesian methods are particularly well-suited for applications incorporating historical data or expert knowledge, while classical approaches offer efficiency and simplicity when dealing with large, representative datasets. Hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both paradigms present promising avenues for future research in sensor reliability analysis.

Practical Implementation: From Bernoulli Trials to Complex System Modeling

In reliability engineering, sensor development, and pharmaceutical research, statistical analysis of success/no-success data—often termed "Bernoulli trials"—is fundamental for determining product reliability, treatment efficacy, and system performance. The classical binomial model and Bayesian beta-binomial model represent two philosophically and methodologically distinct approaches to this analysis. The binomial model operates within the frequentist paradigm, treating parameters as fixed unknown quantities to be estimated solely from collected data [29]. In contrast, the beta-binomial model operates within the Bayesian framework, explicitly incorporating prior knowledge or expert belief into the analysis while providing a natural mechanism to account for overdispersion—the common phenomenon where observed data exhibits greater variability than predicted by simple binomial sampling [30] [31].

The choice between these methodologies carries significant implications for research conclusions, particularly in fields with high-stakes decision-making such as medical device validation and drug development. This guide provides an objective comparison of these competing approaches, examining their theoretical foundations, implementation requirements, and performance characteristics to inform methodological selection in reliability and development research contexts.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Frameworks

The Classical Binomial Model

The classical binomial model represents the frequentist approach to analyzing binary outcome data. It assumes that each trial is independent and identically distributed, with a constant, fixed probability of success across all trials.

Mathematical Formulation: For ( n ) independent trials with a fixed probability of success ( \theta ), the probability of observing ( y ) successes is given by: [ P(Y = y | \theta) = \binom{n}{y} \theta^y (1-\theta)^{n-y} ] where ( \theta ) is treated as an unknown but fixed parameter [29]. Estimation typically proceeds via maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), yielding the intuitive estimator ( \hat{\theta}_{MLE} = y/n ). Confidence intervals are constructed to express the frequency properties of the estimation procedure, interpreted as the long-run coverage probability across repeated sampling.

The Bayesian Beta-Binomial Model

The Bayesian beta-binomial model reformulates the problem by treating the parameter ( \theta ) as a random variable with its own probability distribution, enabling researchers to incorporate prior knowledge formally into the analysis.

Mathematical Formulation: The model uses a beta distribution as the conjugate prior for the binomial likelihood: [ \begin{align} \text{Prior:} \quad & \theta \sim \text{Beta}(\alpha, \beta) \ \text{Likelihood:} \quad & Y | \theta \sim \text{Bin}(n, \theta) \ \text{Posterior:} \quad & \theta | y \sim \text{Beta}(\alpha + y, \beta + n - y) \end{align} ] where ( \alpha ) and ( \beta ) are hyperparameters that characterize prior beliefs about the success probability [32] [29]. The posterior distribution combines prior knowledge with empirical evidence, with the relative influence of each determined by the sample size and the concentration of the prior.

The beta-binomial model naturally accommodates overdispersion through its hierarchical structure. When population heterogeneity exists—violating the binomial assumption of constant success probability—the beta-binomial provides a better fit by modeling this extra-binomial variation [30] [31].

Methodological Comparison and Experimental Evaluation

Fundamental Philosophical and Practical Differences

Table 1: Core Conceptual Differences Between Binomial and Beta-Binomial Models

| Aspect | Classical Binomial Model | Bayesian Beta-Binomial Model |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter Interpretation | Fixed unknown constant | Random variable with distribution |

| Prior Information | Not incorporated | Explicitly incorporated via prior distribution |

| Output | Point estimate and confidence interval | Full posterior distribution |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Frequency-based (sampling distribution) | Probability-based (credible intervals) |

| Overdispersion Handling | Cannot accommodate | Naturally handles through hierarchical structure |

| Computational Complexity | Generally simple | Often requires MCMC for complex extensions |

Experimental Performance Comparison

Experimental studies have systematically evaluated the performance of both approaches under various conditions, particularly focusing on estimation accuracy and uncertainty quantification.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Based on Simulation Studies

| Performance Metric | Classical Binomial Model | Bayesian Beta-Binomial Model |

|---|---|---|

| Bias in Small Samples | High when data are sparse | Reduced with informative priors |

| Variance Estimation | Often underestimated with overdispersion | More accurate with overdispersion |

| Coverage Probability | Below nominal level with model violations | Closer to nominal with appropriate priors |

| Influence of Prior | Not applicable | Significant with small samples, diminishes with large samples |

| Handling of Zero Events | Problematic (zero estimate) | Accommodated through prior |

Research by Palm et al. demonstrated that the beta-binomial model "outperforms the usual ARMA- and Gaussian-based detectors" in signal detection applications, highlighting its superior performance in specific inferential contexts [33]. In reliability engineering, Bayesian approaches have proven particularly valuable for high-reliability systems where failures are rare, as they can formally incorporate information from similar systems, expert opinion, or previous generations of a product [34] [35].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Method Comparison

To objectively compare these methodologies in practice, researchers can implement the following experimental protocol:

Step 1: Data Generation

- Simulate binary outcome data under varying conditions: (a) ideal binomial conditions (constant θ), (b) with overdispersion (θ varying across subgroups), and (c) with small sample sizes (n < 30)

- For overdispersed scenarios, implement a beta-binomial data generation process where θ ~ Beta(α,β) and then Y | θ ~ Bin(n,θ)

Step 2: Model Implementation

- For classical binomial: Compute MLEs and Wald-type 95% confidence intervals

- For beta-binomial: Implement with both weakly informative (Beta(1,1)) and moderately informative priors (e.g., Beta(3,1) for high-reliability scenarios)

- Use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods for posterior sampling if closed-form solutions are unavailable

Step 3: Performance Evaluation

- Calculate empirical bias: ( \frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^N (\hat{\theta}i - \theta_{true}) )

- Compute mean squared error: ( \frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^N (\hat{\theta}i - \theta_{true})^2 )

- Evaluate coverage probability: proportion of simulations where confidence/credible intervals contain θtrue

- Assess interval width: average length of confidence/credible intervals

This protocol mirrors approaches used in rigorous methodological comparisons, such as those described by Harrison who evaluated models "under various degrees of overdispersion" and across "a range of random effect sample sizes" [30].

Implementation Workflows and Computational Tools

Analytical Workflows

The conceptual and analytical workflows for implementing these approaches differ significantly, as illustrated below:

Table 3: Essential Tools for Implementing Binomial and Beta-Binomial Analyses

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Software | R, Python, Stan, JAGS | General implementation |

| R Packages | binom, VGAM, emdbook | Classical binomial analysis |

| Bayesian R Packages | rstanarm, brms, MCMCpack | Beta-binomial modeling |

| Diagnostic Tools | Posterior predictive checks, residual plots | Model validation |

| Prior Elicitation | SHELF protocol, prior predictive checks | Informed prior specification |

For reliability applications with limited data, Botts emphasizes that Bayesian methods are particularly valuable as they "enable inclusion of other types of data (such as computer simulation experiments or subject-matter-expert opinions)" [6]. This capability is crucial in fields like pharmaceutical development and high-reliability engineering where ethical constraints, cost, or rarity of events limits sample sizes.

Application in Sensor Reliability and Drug Development Contexts

Sensor Reliability Analysis

In sensor reliability assessment, researchers often encounter scenarios with limited failure data, especially for high-reliability components. The Bayesian approach provides a formal mechanism to incorporate information from accelerated life tests, similar component types, or physics-based models. For example, a study on hierarchical Bayesian modeling demonstrated that "choosing strong informative priors leads to distinct predictions, even if a larger sample size is considered" [34]. This property is particularly valuable when assessing conformance to reliability requirements with minimal testing.

In a three-state reliability model (normal, potential failure, functional failure), Bayesian methods allow integration of multi-source prior information, addressing the "contradiction between small test samples and high reliability requirements" that directly impacts development costs and timelines [35].

Pharmaceutical Development Applications

In drug development, success/no-success data arises in various contexts including toxicology studies, clinical trial endpoints, and manufacturing quality control. The beta-binomial model's ability to handle overdispersion makes it particularly valuable for multi-center clinical trials where patient populations or practice patterns may introduce variability beyond simple binomial sampling.

Bayesian approaches also facilitate adaptive trial designs through natural incorporation of accumulating evidence, potentially reducing development costs and time-to-market while maintaining rigorous decision standards. The explicit quantification of uncertainty via posterior distributions supports more nuanced risk-benefit assessments in regulatory submissions.

The choice between classical binomial and Bayesian beta-binomial models involves trade-offs between philosophical frameworks, implementation complexity, and inferential goals. The classical binomial model offers simplicity, computational efficiency, and familiar interpretation, performing well when the binomial assumptions are met and sample sizes are adequate. Conversely, the Bayesian beta-binomial model provides greater flexibility for incorporating prior knowledge, naturally handles overdispersion, and offers more intuitive uncertainty quantification through credible intervals.

For research applications, selection guidelines include:

- Use classical binomial when prior information is unavailable or incorporation is undesirable, data follow binomial assumptions, and rapid implementation is prioritized

- Prefer beta-binomial when prior information exists, sample sizes are small, overdispersion is suspected, or intuitive probability statements about parameters are desired

In sensor reliability and drug development contexts where testing is costly and failures are rare, the Bayesian approach offers distinct advantages through formal information integration. As with any methodological choice, model assumptions should be validated against empirical data, and sensitivity analyses conducted—particularly for prior specification in Bayesian applications.

In sensor reliability analysis, the choice between classical (frequentist) and Bayesian statistical paradigms profoundly influences model robustness, interpretability, and practical utility. While classical methods offer established, data-driven approaches without requiring prior knowledge, Bayesian methods explicitly incorporate expert opinion and historical data through prior distributions, enabling a more nuanced handling of uncertainty. This guide provides a structured comparison of these frameworks, focusing on their application in sensor data fusion and reliability evaluation. Supported by experimental protocols and quantitative data comparisons, we demonstrate that Bayesian approaches, particularly those utilizing hierarchical models and contextual discounting, offer superior adaptability in dynamic environments and enhanced performance in data-scarce scenarios. The synthesis aims to equip researchers and engineers with the knowledge to select and implement the most appropriate methodology for their specific reliability analysis challenges.

Sensor reliability analysis is a cornerstone of robust multi-sensor data fusion systems, which are critical in fields ranging from target recognition and industrial monitoring to complex network management. These systems combine information from multiple sensors to form a more accurate and coherent perception of the environment than any single sensor could provide. However, sensor data is inherently imperfect, contaminated by environmental noise, deceptive target behaviors, and hardware limitations. Effectively managing this uncertainty and the inherent reliability of each sensor is a fundamental challenge. The Dempster-Shafer Evidence Theory (Evidence Theory) and Bayesian probability have emerged as two powerful, yet philosophically distinct, frameworks for representing and reasoning with such imperfect information [36] [37].

The core divergence between classical and Bayesian methods lies in their treatment of uncertainty and unknown parameters. Classical (frequentist) approaches treat sensor reliability parameters as fixed, unknown quantities to be estimated solely from observed data. Inference relies on long-run frequency properties, such as the performance of an estimator over many hypothetical repeated experiments. In contrast, the Bayesian framework treats all unknown parameters as random variables with associated probability distributions. This allows for the formal incorporation of pre-existing knowledge—whether from expert opinion or historical data—through prior distributions, which are then updated with new observational data via Bayes' theorem to yield posterior distributions [38] [39]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of these two paradigms within the context of sensor reliability analysis, offering experimental protocols, data-driven comparisons, and practical guidance for researchers and engineers.

Theoretical Framework: Classical vs. Bayesian Methods

The Classical (Frequentist) Paradigm

Classical methods in sensor reliability are built on the principle of long-run frequency. A sensor's reliability is a fixed property, and statistical methods aim to estimate it without recourse to prior beliefs.

- Philosophical Basis: Probability is defined as the limit of the relative frequency of an event after a large number of trials. Unknown parameters, such as a sensor's failure rate, are considered fixed, and the data is random [40] [11].

- Reliability Estimation: Common techniques include Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) for point estimates of parameters (e.g., failure rate λ in an exponential model) and confidence intervals to express uncertainty. For example, a 95% confidence interval for a sensor's Mean Time To Failure (MTTF) implies that if the same experiment were repeated numerous times, 95% of the calculated intervals would contain the true MTTF [11]. It is a common misconception to interpret this as a 95% probability that the true value lies within a specific, calculated interval [40] [38].

- Handling Conflict: In evidence theory, the classical Dempster's rule of combination can produce counter-intuitive results when fusing highly conflicting evidence from multiple sensors, a problem famously highlighted by Zadeh [37].

The Bayesian Paradigm and the Role of Priors

The Bayesian paradigm offers a fundamentally different approach by formally integrating existing knowledge with empirical data.

- Philosophical Basis: Probability is interpreted as a degree of belief. Parameters are random variables, and the goal is to quantify belief in their possible values given the observed data [39] [11]. This is achieved through Bayes' theorem:

Posterior ∝ Likelihood × Prior. - Specifying Prior Distributions: The prior distribution is the mechanism for incorporating existing knowledge.

- Expert Elicitation: This is a structured interview process that guides domain experts to express their knowledge in probabilistic form. For instance, experts might be asked to bet on parameter values or assess the plausibility of future data to formulate an informed prior [41]. The reliability of a sensor can be assessed conditionally on different contexts (e.g., different target types or weather conditions), leading to a vector of discount rates rather than a single number [42].

- Historical Data: Data from previous, similar systems or experiments can be used to construct an empirical prior. In hierarchical Bayesian modeling, this can be extended by placing hyperpriors on the parameters of the prior distribution itself, adding another layer of flexibility [43].

- Expressing Results: The outcome of a Bayesian analysis is the posterior distribution. Summaries of this distribution, such as the credible interval, provide an intuitive and direct probabilistic statement. A 95% credible interval means there is a 95% probability that the true parameter value lies within that interval, given the data and the prior [38] [39].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow of the Bayesian approach to updating beliefs about a sensor's reliability.

Comparative Experimental Analysis

To objectively compare the performance of classical and Bayesian methods, we outline a standardized experimental protocol and present synthesized results from the literature.

Experimental Protocol for Sensor Reliability Evaluation

- System Modeling: Define a target recognition system with a set of heterogeneous sensors (e.g., optical, RADAR, infrared) [36]. The frame of discernment, Ω, might consist of possible target classes {ω₁, ω₂, ..., ωₚ}.

- Data Generation: Simulate sensor outputs and true target classes. Data should include:

- A training set for establishing baseline performance.

- A test set with varying conditions (e.g., different targets, environmental noise) to evaluate dynamic performance [36].

- Reliability & BBA Determination:

- Classical Method: Compute a static reliability factor for each sensor based on its confusion matrix or recognition rate from the training set. Generate Basic Belief Assignments (BBA) and combine them using Dempster's rule (potentially with pre-processing to handle conflict) [37].

- Bayesian Method: Elicit prior distributions for sensor reliability from experts or derive them from the training set. For evidence theory, implement a discounting operation (classical or contextual) using the reliability factor α, where the BBA m is transformed to m_α [36] [42]. Update beliefs using Bayesian inference or the appropriate combination rule.

- Performance Metrics: Compare methods based on target classification accuracy, robustness to conflicting evidence, and computational efficiency.

Quantitative Comparison of Methodologies

The table below summarizes a synthesized comparison based on experimental results from the reviewed literature.

Table 1: Comparative performance of classical and Bayesian methods in sensor reliability analysis

| Feature | Classical (Frequentist) Methods | Bayesian Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophical Basis | Probability as long-run frequency [40] | Probability as degree of belief [39] |

| Treatment of Parameters | Fixed, unknown quantities [11] | Random variables with distributions [11] |

| Use of Prior Knowledge | Not directly incorporated | Formally incorporated via prior distributions [41] |