Building Robust Computational Models in Plant Biology: From Data Integration to Predictive Power

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on enhancing the robustness of computational models in plant biology.

Building Robust Computational Models in Plant Biology: From Data Integration to Predictive Power

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists on enhancing the robustness of computational models in plant biology. It explores the foundational principles of model building, including the unique challenges posed by plant genomes, such as polyploidy and high repetitive content. The piece details advanced methodological approaches, from foundation models for DNA and protein sequences to deep learning applications for phenotyping. It further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for data and architecture selection, and concludes with rigorous validation and comparative analysis frameworks. By synthesizing the latest advances, this resource aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to develop more reliable, generalizable, and impactful predictive models for both basic plant science and applied crop improvement.

Laying the Groundwork: Principles and Challenges in Plant Biology Modeling

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental definition of robustness in computational biology? A1: Robustness is formally defined as the capacity of a system to maintain a function in the face of perturbations [1]. This means a robust biological model continues to perform correctly even when its parameters, inputs, or environmental conditions vary.

Q2: How is robustness different from reproducibility and replicability? A2: These are distinct but related concepts [2]:

- Reproducibility: Achieving quantitatively identical results using the same methods, data, and code.

- Replicability: Obtaining statistically similar results when repeating experiments under the same conditions.

- Robustness: Maintaining similar outcomes despite variations in conditions or protocol parameters.

Q3: What are the main types of robustness quantified in biological models? A3: Research identifies several key implementation types [3]:

Table: Types of Robustness Quantification in Biological Systems

| Robustness Type | What is Measured | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Stability | Stability of system functions across different perturbations | Growth rate stability across hydrolysates |

| Cross-System Similarity | Similarity of functions across different systems under same perturbation | Growth function similarity across yeast strains |

| Temporal Stability | Stability of parameters over time | Intracellular parameter dispersion over time |

| Population Homogeneity | Homogeneity of parameters within a cell population | Quantifying population heterogeneity |

Q4: Why should plant biologists care about model robustness? A4: Robust outcomes from experiments or models are more likely to be biologically relevant under natural conditions, which are inherently variable [2]. Furthermore, robust protocols are more transferable between labs with different equipment or resources, enhancing collaborative potential.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Model Robustness to Parameter Variations

Symptoms: Your model's predictions change dramatically with small changes in parameter values, or it requires excessively precise parameter tuning to match experimental data.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Root Cause: Over-fitting to a specific dataset or nominal parameter set, lacking generalizability.

- Corrective Actions:

- Implement Robustness Quantification: Systematically test your model against a defined "perturbation space." Use Trivellin’s robustness equation, a Fano factor-based method, to compute a dimensionless robustness score for key model outputs [3].

- Distinguish Absolute and Relative Robustness:

- Formalize Expected Behavior with Temporal Logic: Precisely define the system's desired function using Linear Temporal Logic (LTL). The violation degree of these LTL formulae can then computationally assess how far a perturbed behavior is from the expected one, providing a quantitative measure of robustness [1].

Problem 2: Model Fails to Capture Biological Generalizability

Symptoms: The model works well for one specific biological context (e.g., one cell type, species, or environment) but fails to predict outcomes in related contexts.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Root Cause: The model is likely a "pattern model" that identifies correlations from data but lacks underlying mechanistic principles [4].

- Corrective Actions:

- Incorporate Mechanistic Mathematical Modeling: Move beyond statistical correlations by building models based on biochemical reactions, biophysical laws, and mass-action kinetics. These ODE-based models provide a more principled basis for generalizing across contexts [4].

- Adopt Multi-Scale Hybrid Frameworks: Integrate different modeling approaches to capture different biological scales. For example, combine agent-based modeling (for cells) with ODEs/PDEs (for molecular reactions) to create a more comprehensive representation of the system [5].

- Integrate Multi-Omics Data: Use Machine Learning (ML) to integrate heterogeneous data (genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic). This helps capture the complex interactions among genes, pathways, and environment that govern generalizable responses [6].

Problem 3: Inconsistent Experimental Results Hampering Model Validation

Symptoms: You cannot get consistent, replicable results from wet-lab experiments, making it impossible to build or validate a reliable computational model.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Root Cause: High sensitivity to uncontrolled variations in complex multi-step experimental protocols [2].

- Corrective Actions:

- Systematically Document Protocol Variations: Identify and record all potential sources of variation. As demonstrated in split-root assays, factors like nutrient concentrations, light levels, and recovery periods can significantly impact outcomes [2].

- Test for Robustness Experimentally: Actively investigate which protocol variations substantially affect outcomes and which changes the system can buffer against. Robust phenotypic outcomes are more reliable for model validation [2].

- Enhance SOPs with Critical Step Highlighting: In Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), use bold text or color to highlight steps that are particularly sensitive or prone to human error, such as specific pipetting techniques or wash steps [7].

Experimental Protocols for Robustness Analysis

Protocol 1: Quantifying Robustness in Microbial Strains

This protocol outlines the method used to characterize the robustness of Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains in hydrolysates [3].

1. Objective: To quantify the robustness of growth-related functions and intracellular parameters in yeast strains across different lignocellulosic hydrolysates.

2. Materials and Reagents: Table: Key Research Reagents for Microbial Robustness Assay

| Reagent / Tool | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae strains (e.g., CEN.PK113-7D, Ethanol Red) | Model systems for robustness quantification. |

| Lignocellulosic Hydrolysates (e.g., from wood waste) | Complex perturbation space to test stability. |

| Synthetic-defined minimal Verduyn medium | Control medium for baseline comparisons. |

| ScEnSor Kit fluorescent biosensors | Monitor 8 intracellular parameters (pH, ATP, oxidative stress, etc.). |

| BioLector I high-throughput microbioreactor | Enables parallel cultivation under controlled conditions. |

3. Methodology: 1. Cultivation: Grow yeast strains in a high-throughput system (e.g., BioLector I) in control medium and seven different lignocellulosic hydrolysates. 2. Data Collection: Measure growth-related functions (specific growth rate, product yields) and eight intracellular parameters via fluorescent biosensors. 3. Robustness Calculation: Apply Trivellin’s robustness equation to the collected data to compute robustness indices for the four types outlined in FAQ A3.

4. Expected Output: A robustness score for each strain, allowing for the selection of strains that are not only high-performing but also stable across variable industrial substrates.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Robustness in a Plant Biology Protocol

This protocol uses the split-root assay as a case study for testing the robustness of an experimental outcome itself [2].

1. Objective: To determine which variations in a split-root assay protocol robustly yield the phenotype of preferential nitrogen foraging.

2. Materials: - Arabidopsis thaliana seeds. - Agar plates with varying nitrate concentrations (High Nitrogen: 1-10 mM KNO₃, Low Nitrogen: 0.05 mM KNO₃ or KCl controls). - Growth chambers with controlled light and temperature.

3. Methodology: 1. Systematic Variation: Execute the split-root assay while deliberately varying key parameters as found in literature, such as: - HN and LN concentrations. - Photoperiod and light intensity. - Duration of growth before splitting, recovery, and heterogeneous treatment. - Sucrose and nitrogen source in the growth media. 2. Phenotype Scoring: For each protocol variant, quantify the key foraging phenotype (preferential investment in root growth on the high nitrate side). 3. Robustness Assessment: Determine if the phenotype is consistently observed across the wide range of tested protocol parameters.

4. Expected Output: Identification of critical and non-critical protocol steps, leading to a more robust and transferable experimental method.

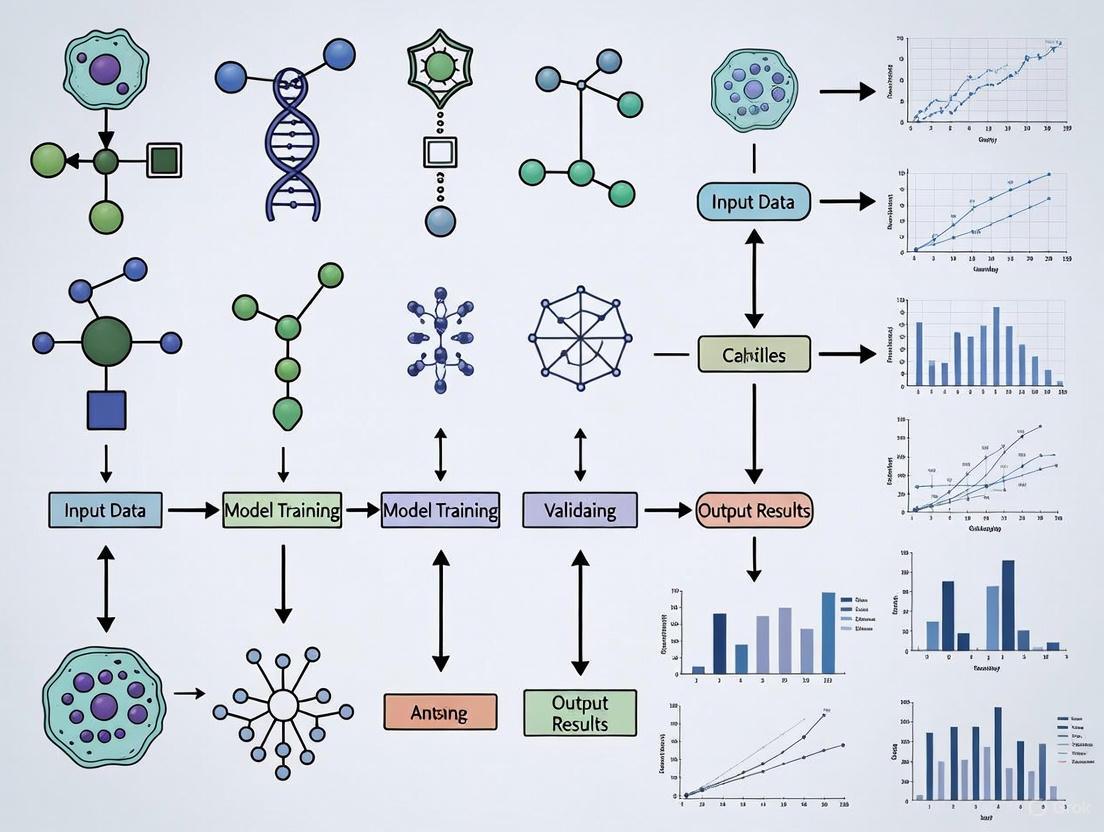

Essential Visualizations

Diagram 1: Robustness Quantification Workflow in Computational Biology

Diagram 2: Multi-Scale Modeling for Robustness Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do computational models trained on animal or human data often perform poorly on plant genomes? Plant genomes possess unique characteristics that are not well-represented in models trained on other kingdoms. Key challenges include:

- Polyploidy: Many plants, like wheat (allohexaploid) or peanut (allotetraploid), contain more than two sets of chromosomes. This creates multiple, very similar genomic sequences (homeologs) that are difficult to distinguish during sequencing and assembly, leading to fragmented and incomplete reference genomes [8] [9].

- High Repetitive Content: Plant genomes can be composed of over 80% repetitive sequences and transposable elements (e.g., in maize). This creates ambiguity for sequence alignment and introduces significant noise during model training [9].

- Environment-Responsive Regulation: Plant gene expression is dynamically regulated by diverse environmental factors (e.g., drought, salinity, light). Models trained on data from stable laboratory conditions may not generalize well to these complex, dynamic responses [9] [10].

Q2: What are the main computational challenges in assembling polyploid plant genomes, and how can they be overcome? The primary challenge is distinguishing between highly similar sub-genomes (homeologs). Standard assembly tools designed for diploid genomes often collapse these duplicate regions, creating a chimeric and inaccurate assembly [8].

- Solution: Utilize "third-generation" long-read sequencing technologies (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore). Their longer reads can span repetitive regions and homeologous variations, enabling more accurate chromosome-scale scaffolding. Advanced bioinformatics techniques like haplotyping by phasing are also crucial for separating the individual sub-genomes [8].

Q3: How does environmental stress directly impact a plant's genome and the data we collect from it? Environmental stress does not only change gene expression; it can directly accelerate the rate of genomic change. Research on Arabidopsis thaliana has shown that multigenerational growth in saline soil can lead to [11]:

- Increased Mutation Rates: A ~100% increase in the frequency of accumulated DNA sequence mutations.

- Altered Mutation Profiles: A distinctive molecular spectrum with a higher proportion of transversions and indels.

- Epigenetic Changes: A ~45% increase in inherited epigenetic marks (differentially methylated cytosine positions). These stress-induced changes increase genetic diversity and noise in datasets, which must be accounted for in experimental design and model training [11] [12].

Q4: What types of computational models are best suited for predicting plant growth in response to complex environmental conditions? For modeling complex, non-linear relationships like plant growth, data-driven approaches are highly effective. Bayesian Neural Networks (BNNs) have been successfully used to model daily plant growth in controlled environments by integrating data on temperature, light, CO₂, and humidity [13]. These models can handle the randomness and complexity of agricultural data, providing accurate predictions that can inform climate control strategies to maximize yield and resource-use efficiency [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Performance of a Foundational Model on Your Plant Species

- Symptoms: Low accuracy in tasks like gene expression prediction, variant effect prediction, or regulatory element identification.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: The model was pre-trained on data from non-plant species (e.g., human or animal genomes) and cannot generalize to plant-specific complexities [9].

- Solution: Use or fine-tune a plant-specific foundation model such as AgroNT, PlantCaduceus, or PlantRNA-FM, which are designed to handle issues like polyploidy and repetitive sequences [9].

- Cause 2: The genomic context of your species of interest is too divergent from the training data of even a plant-specific model.

- Cause 1: The model was pre-trained on data from non-plant species (e.g., human or animal genomes) and cannot generalize to plant-specific complexities [9].

Problem: High Error Rate in Genome Assembly for a Polyploid Crop

- Symptoms: A highly fragmented assembly with short contigs and scaffolds; inability to resolve homeologous chromosomes.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Reliance on short-read sequencing data.

- Solution: Integrate long-read sequencing data to generate a more contiguous and complete assembly. The table below compares the impact of sequencing techniques on polyploid genome assembly [8].

- Cause 1: Reliance on short-read sequencing data.

Table 1: Impact of Sequencing Technologies on Polyploid Plant Genome Assembly

| Sequencing Technology | Typical Read Length | Advantages for Polyploids | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Read (Illumina) | 50-300 bp | High accuracy, low cost | Cannot resolve long repeats or homeologous regions, leading to fragmented assemblies. |

| Long-Read (PacBio, Nanopore) | 10 kb - 1 Mb+ | Spans repetitive sequences and homeologs, enabling chromosome-scale scaffolds. | Higher error rate (though now much improved), higher DNA quantity/quality required. |

* Cause 2: Using a standard diploid-focused assembly pipeline. * Solution: Employ specialized assemblers and phasing tools (e.g., integrated in the Pairtools suite for Hi-C data) that can leverage long-range information to separate sub-genomes and correctly assign haplotypes [8] [14].

Problem: Noisy or Inconsistent Gene Expression Data from Stress Experiments

- Symptoms: High variability between biological replicates, difficulty in identifying statistically significant differentially expressed genes.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The dynamic and individualized nature of plant stress responses, compounded by genetic and epigenetic heterogeneity [11] [10] [12].

- Solution:

- Increase Replication: Use more biological replicates than standard protocols recommend to account for high variability.

- Control Environmental Variance: Strictly control growth conditions (light, humidity, soil composition) to minimize non-stress-related noise.

- Apply Robust Normalization: Use statistical methods designed for noisy data (e.g., those in tools like DESeq2) and consider time-series analyses to capture dynamic patterns rather than single time-point snapshots [4].

- Solution:

- Cause: The dynamic and individualized nature of plant stress responses, compounded by genetic and epigenetic heterogeneity [11] [10] [12].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Stress-Induced Genomic and Epigenomic Variation

- Objective: To quantify the rate and spectrum of mutations and epimutations in plants grown over multiple generations under environmental stress.

- Background: This protocol is based on a Mutation Accumulation (MA) lineage study in Arabidopsis thaliana exposed to saline soil [11].

- Materials:

- Plant lines (e.g., isogenic lines of A. thaliana Col-0).

- Control and saline soil treatments.

- Equipment for DNA and bisulfite sequencing.

- Method Steps:

- Establish MA Lineages: Propagate at least three independent, single-seed descent lineages for a minimum of 5-10 generations under both control and stress conditions.

- Phenotypic Monitoring: Record generation time and visible stress symptoms (e.g., growth retardation, chlorosis) each generation [11] [10].

- Sequencing: In the final generation (e.g., G10), perform Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) and Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) on plants from each lineage and the progenitor.

- Variant Calling: Identify de novo DNA sequence mutations and differentially methylated positions (DMPs) by comparing G10 genomes to the progenitor genome.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate and compare mutation rates and epimutation rates between control and stressed lineages.

- Analyze the molecular spectrum of mutations (e.g., Ti/Tv ratio, indel frequency) [11].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Long-Read Sequencer | Generating long sequencing reads to resolve complex genomic regions. | PacBio Sequel II or Oxford Nanopore PromethION for assembling polyploid genomes [8]. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit | Converting unmethylated cytosines to uracils for methylation profiling. | Essential for Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing to detect epigenetic changes [11]. |

| Plant-Specific Foundation Model | A pre-trained model for genomic analysis tasks tailored to plant genomes. | AgroNT (for gene regulation), PlantCaduceus (for genome analysis) [9]. |

| Pairtools Suite | Processing sequencing data from Hi-C and other 3C+ protocols into chromosome contacts. | Critical for assessing 3D genome structure and validating assembly [14]. |

| Bayesian Neural Network (BNN) | Modeling and predicting plant growth from complex environmental data. | Effectively handles uncertainty and randomness in greenhouse sensor data [13]. |

Protocol 2: Building a Predictive Growth Model Using Bayesian Neural Networks

- Objective: To create a model that predicts daily plant growth (e.g., lettuce fresh weight) in response to environmental conditions in a controlled greenhouse [13].

- Materials:

- Sensor network for continuous monitoring of air temperature, humidity, CO₂ concentration, and light radiation.

- Daily plant growth measurements (e.g., leaf area, fresh weight).

- Method Steps:

- Data Collection: Collect high-temporal-resolution environmental data and corresponding plant growth data over at least one full growth cycle in both warm and cold seasons.

- Data Pre-processing: Clean the data, handle missing values, and normalize the input features.

- Model Training: Train several BNN architectures on the environmental data to predict plant growth metrics. BNNs are suitable as they quantify prediction uncertainty, which is valuable for agricultural decision-making [13].

- Model Validation: Evaluate the model's accuracy on a held-out test dataset from a different season using metrics like Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

- Deployment: Integrate the trained model into a greenhouse control system to optimize environmental parameters for maximizing yield and resource-use efficiency [13].

Visualizations

Stress-Induced Genome Evolution

Solving Plant Modeling Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. When should I choose a mechanistic model over a machine learning approach? Choose a mechanistic model when your goal is to understand the causal relationships in your system, you have small datasets, or you need to make predictions about scenarios not present in your existing data (extrapolation). Mechanistic models are ideal for generating and testing hypotheses about biological functions [15].

2. My mechanistic model is computationally too slow for parameter exploration. What can I do? You can develop a Machine Learning Surrogate Model. This involves training a machine learning model to approximate the input-output relationships of your complex mechanistic model. Once trained, the ML surrogate can provide results in a fraction of the time, enabling rapid parameter screening and sensitivity analyses [16].

3. How can I leverage machine learning if I have limited plant omics data? Consider using Foundation Models (FMs) pre-trained on large-scale biological sequences from multiple species. These models, such as AgroNT or PlantCaduceus, have learned general biological principles and can be fine-tuned for specific downstream tasks in your plant system, even with limited data [9].

4. Why do my model's predictions fail when our experimental protocol slightly changes? This may indicate a lack of robustness. In computational biology, a robust model's outcomes should remain stable despite moderate changes to parameters or assumptions. Investigate which protocol variations substantially affect outcomes; this informs which parameters are critical and can lead to more reliable, real-world relevant models [2].

5. How can I integrate single-cell RNA-seq data into my models of plant development? Single-cell RNA-seq data can be clustered to identify distinct cell types and states. This information can be used to parameterize or constrain mechanistic models of developmental processes. The resulting models can simulate cellular dynamics and gene regulatory networks with much higher resolution [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Predictions Do Not Match Experimental Observations

Checklist:

- Calibrate and Validate: Ensure you use a two-stage process: a subset of data for model calibration and a separate, further dataset for validation [15].

- Review Simplifying Assumptions: Mechanistic models are built on simplified assumptions. Re-evaluate if critical mechanisms have been overlooked for your specific use case [15].

- Check for Data Shift (ML Models): For machine learning, ensure the data you are using for prediction comes from the same distribution as the training data. ML models struggle with extrapolation [15].

Problem: Computational Time of the Model is Prohibitive

Solution: Implement an ML Surrogate Model This workflow creates a fast, approximate version of your slow mechanistic model [16].

Procedure:

- Define Scope: Identify the key inputs/parameters and the target outputs of your mechanistic model you wish to approximate.

- Generate Data: Run the original mechanistic model thousands of times with varying inputs to create a dataset of input-output pairs.

- Train Surrogate: Use 80-90% of this data to train a machine learning model (e.g., LSTM, neural network, Gaussian process).

- Validate: Test the trained ML surrogate on the remaining 10-20% of the data. Validate that its predictions are sufficiently accurate and that it captures the core behavior of the original model.

- Deploy: Use the validated ML surrogate for all subsequent simulations and analyses. This can yield a speed improvement of 3 to 6 orders of magnitude [16].

Problem: Ensuring Robust and Replicable Results in Complex Experiments

Context: This is common in multi-step plant biology experiments, such as split-root assays for studying nutrient foraging [2].

Solution: Protocol Sensitivity Analysis

Procedure:

- Systematically Document Variations: Record all potential sources of variation in your experimental protocol (e.g., growth media concentrations, light levels, duration of steps).

- Test Key Parameters: Conduct experiments where you intentionally vary these parameters one at a time within a reasonable range.

- Identify Critical Factors: Determine which parameters significantly alter the outcome (e.g., the observation of preferential root growth). These are the factors that must be tightly controlled and meticulously reported.

- Establish Robust Protocol: Use this knowledge to create a detailed protocol that specifies which steps are critical and which allow for flexibility, enhancing the replicability of your research across different labs [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key resources for setting up and analyzing split-root assays, a common but complex experiment in plant nutrient foraging research.

| Item | Function | Example Usage/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Model plant organism | Ensure consistent genetic background for replicability [2]. |

| Agar Plates | Solid growth medium | Allows for precise control of nutrient localization and root visualization [2]. |

| KNO₃ & KCl | Nitrogen source and ionic control | Used to create High Nitrate (HN) and Low Nitrate (LN) conditions (e.g., 5mM KNO₃ vs. 5mM KCl) [2]. |

| Sucrose | Carbon source in media | Concentration can vary (e.g., 0.3% to 1%); must be consistent as it impacts growth [2]. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | Isolation of nuclei for single-cell omics | Used for snRNA-seq to avoid gene expression changes from protoplasting [17]. |

| 10x Genomics Platform | High-throughput scRNA-seq library construction | Enables cell-type-specific transcriptome profiling [17]. |

| Seurat / SCANPY | scRNA-seq data analysis toolkit | Used for clustering, normalization, and cell type annotation [17]. |

Model Selection and Integration Workflow

Use this decision diagram to select the appropriate modeling approach for your project and understand how they can be integrated.

Integration Pathways:

- ML within Mechanistic: Machine learning can be used to learn specific, hard-to-model components within a larger mechanistic framework. For example, using a surrogate model to speed up one computationally expensive part of a multiscale simulation [15] [16].

- Mechanistic within ML: Mechanistic models can generate derived parameters or features that are then used as inputs to machine learning algorithms, providing them with biologically informed priors and improving their performance [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My computational model becomes intractable when I include full metabolic pathway details. How can I simplify it without losing predictive power? Focus on identifying rate-limiting steps. Map the complete pathway using a tool like Graphviz to visualize connections, then perform a sensitivity analysis to quantify the effect of each reaction parameter on your final output. Nodes with low sensitivity indices (e.g., < 0.05) are candidates for removal or simplification into a static function.

Q2: How do I validate that my simplified plant growth model is still biologically plausible? Design a multi-scale validation protocol. Calibrate your model using primary data from one spatial scale (e.g., cellular). Then, test its predictions against a separate, held-out dataset from a different scale (e.g., tissue or organ). A robust model should maintain an R² value of >0.7 across scales.

Q3: What is the best practice for handling unknown parameters in a newly developed model? Apply a parameter ensemble approach. Instead of seeking a single "correct" value, define a plausible range for the unknown parameter based on literature. Run multiple simulations sampling from this range and analyze the variance in your outcomes. This identifies which unknowns critically influence model robustness.

Q4: I am getting conflicting results when my model is run with different numerical solvers. How should I troubleshoot this? This often indicates a "stiff" system of equations. Create a diagnostic workflow: First, check for solver stability by comparing results with drastically reduced time steps. Second, profile your model's execution time to identify specific equations that cause the slow-down. The solution may require reformulating these equations or using a solver designed for stiff systems.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Model Generalization

Your model fits your calibration data well but fails to predict independent datasets.

Investigation Protocol:

- Test for Overfitting: Calculate the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). A lower AIC suggests a better balance of fit and simplicity. If adding complexity only slightly improves fit but greatly increases AIC, your model is likely over-parameterized.

- Conduct Cross-Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation (typically k=5 or 10). If model performance varies significantly across folds, it has not learned generalizable rules.

- Check Input Data: Ensure the independent dataset follows the same distribution and was generated under comparable experimental conditions as the calibration data.

Solution: Apply regularization techniques (e.g., L1/L2 regularization) during parameter estimation to penalize complexity. Simplify the model by merging parameters with high correlation or by removing biological details that contribute little to the overall output variance.

Problem: Model Simulation Crashes or Fails to Converge

The numerical solver fails to find a solution, often due to mathematical instability.

Investigation Protocol:

- Isolate the Issue: Run the model with a minimal set of inputs and gradually add components to identify the module causing the crash.

- Inspect Parameter Values: Check for physically impossible values (e.g., negative concentrations) or parameters that have drifted to extreme values during estimation.

- Analyze Equation Formulation: Look for division by a variable that can approach zero or highly non-linear functions that may create discontinuities.

Solution: Reformulate problematic equations. Implement safeguards in the code, such as setting value bounds for critical variables. Switch to a more robust numerical solver designed for stiff differential equations.

Experimental Protocols for Cited Key Experiments

Protocol 1: Sensitivity Analysis for Model Simplification

Objective: To identify which model parameters have the least influence on output, allowing for safe simplification. Methodology:

- Define a baseline output for your model under standard conditions.

- For each parameter

p_i, perturb its value by a fixed percentage (e.g., ±10%). - Run the model for each perturbation and record the change in output.

- Calculate a normalized sensitivity coefficient

S_ifor each parameter:S_i = (ΔOutput / Output_baseline) / (Δp_i / p_i_baseline). - Rank parameters by the absolute value of

S_i. Parameters with the lowest|S_i|are the best candidates for removal or aggregation.

Protocol 2: Multi-Scale Validation of a Simplified Root Architecture Model

Objective: To ensure a model simplified from the cellular level still validly predicts organ-level phenotypes. Methodology:

- Cellular Calibration: Calibrate the model using data on single root cell division and elongation rates from time-lapse microscopy.

- Tissue-Level Validation: Use the calibrated model to predict the emergent formation of root tissue layers. Compare predictions to histological sections of the root, measuring layer thickness and cell count.

- Organ-Level Prediction: Run the model to simulate overall root growth architecture (primary root length, lateral root density). Validate against independent datasets of whole-root system scans.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| L-Glutamine (Isotope-Labeled) | Tracks nitrogen uptake and assimilation pathways in metabolic flux analysis. |

| Cellulose Synthesis Inhibitor (e.g., Isoxaben) | Perturbs cell wall formation to test model predictions on growth mechanics. |

| Genetically Encoded Calcium Indicator (e.g., GCaMP6) | Live-imaging of calcium signaling, a key second messenger in stress responses. |

| Phytohormone (e.g., Auxin, Abscisic Acid) | Used in pulse-chase experiments to parameterize hormone-response modules in models. |

Visualizing a Simplified Signaling Pathway Workflow

The diagram below illustrates a logical workflow for deciding which parts of a biological signaling pathway to include in a computational model, adhering to specified color and contrast rules.

Key Experiment: Signaling Pathway Integration Logic

This diagram outlines the core logic for integrating a key signaling pathway (e.g., auxin response) into a larger model, highlighting points of abstraction.

Advanced Computational Frameworks: From Foundation Models to Multi-Omics Integration

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of plant-specific foundation models over general genomic models?

Plant-specific models like PlantCaduceus, AgroNT, and GPN-MSA are specifically designed to handle the unique complexities of plant genomes, which include high proportions of repetitive sequences (over 80% in maize), polyploidy, and environment-responsive regulatory elements [9]. These models are pre-trained on curated datasets of plant genomes, enabling them to learn evolutionary conservation across species diverged by up to 160 million years [18]. This specialized training allows for superior performance in plant genomics tasks compared to models trained primarily on human or animal data.

Q2: How do I choose the right model for my specific research task?

Model selection depends on your specific task, available computational resources, and target species. The table below provides a comparative overview to guide your decision:

| Model | Primary Architecture | Key Features | Best Suited For | Pre-training Data Scope |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PlantCaduceus | Caduceus/Mamba [18] | Bi-directional context, reverse complement equivariance, single-nucleotide tokenization [18] [19] | Cross-species prediction, variant effect scoring, splice site identification [18] [19] | 16 Angiosperm genomes [18] |

| AgroNT | Transformer [9] | k-mer tokenization, focused on agricultural species | Promoter identification, protein-DNA binding tasks [9] | Plant genomes (specifics not detailed) |

| GPN-MSA | Not Specified | Incorporates multi-species alignment data [9] | Predicting functional variants in non-coding regions [9] | Multi-species alignments |

For a balance of performance and efficiency, PlantCaduceusl32 is recommended for research, while PlantCaduceusl20 is suitable for testing [19].

Q3: What are the common data formatting requirements for these models?

Most models require DNA sequences in FASTA format. However, tokenization strategies differ significantly. PlantCaduceus uses single-nucleotide tokenization, treating each base pair as a separate token [18]. In contrast, models like AgroNT and DNABERT use k-mer tokenization (e.g., overlapping 3-6 base pair segments) [9]. For variant scoring, PlantCaduceus uses standard VCF files for variants and BED files for genomic regions [19]. Ensuring your input data matches the model's expected tokenization strategy is critical for successful operation.

Q4: My model produces poor cross-species predictions. How can I improve this?

This is a common challenge when a model fine-tuned on one species (e.g., Arabidopsis) is applied to a distant species (e.g., maize). To improve cross-species transferability:

- Leverage Pre-trained Embeddings: Use a feature-based approach as implemented in PlantCaduceus. Freeze the pre-trained model and train a simpler classifier (e.g., XGBoost) on the extracted embeddings from your limited labeled data [18]. This leverages the evolutionary conservation already captured by the foundation model.

- Ensure Data Curation: PlantCaduceus showed that down-sampling non-coding regions and down-weighting repetitive sequences during pre-training reduces bias and improves model generalization across species [18]. Apply similar curation to your fine-tuning dataset.

- Use the Right Model: Select models explicitly designed for cross-species applications. PlantCaduceus has demonstrated effective transferability to species not included in its pre-training set, such as maize, outperforming other DNA LMs by 1.45 to 7.23-fold on tasks like splice site prediction [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Installation and Setup Issues

Problem: GPU-related errors during model loading or inference.

- Cause: The model requires an NVIDIA GPU for local operation and might be incompatible with your CUDA version or GPU hardware [19].

- Solution:

- Verify Installation: Ensure you have installed the correct versions of

mamba-ssmandtransformerslibraries as specified in the model's repository [19]. - Check CUDA Compatibility: Confirm that your PyTorch installation is compatible with your CUDA version.

- Use Google Colab: For testing and quick analysis, use the provided Google Colab demo, which requires only a Google account and handles the GPU setup automatically [19].

- Model Selection: If GPU memory is limited, try a smaller model variant like

PlantCaduceus_l20orPlantCaduceus_l24[19].

- Verify Installation: Ensure you have installed the correct versions of

Poor Performance on Downstream Tasks

Problem: Fine-tuned model achieves low accuracy on your target task.

- Cause: This can be due to insufficient labeled data for fine-tuning, a mismatch between the pre-training data and your target species/task, or incorrect fine-tuning methodology.

- Solution:

- Use Feature-Based Fine-Tuning: Instead of full fine-tuning, which can be data-inefficient, use the approach validated with PlantCaduceus: extract sequence embeddings from the pre-trained model and use them to train a task-specific XGBoost classifier. This method has been shown to work effectively even with limited labeled data [18].

- Leverage Pre-Trained Classifiers: Check if pre-trained classifiers are available for common tasks (e.g., translation initiation sites, splice sites). The PlantCaduceus repository provides such classifiers in its

classifiersdirectory [19]. - Data Quality Check: Ensure your labeled data is high-quality and representative of the genomic context you are studying. Remove low-quality sequences and verify annotations.

Interpreting Model Outputs

Problem: Difficulty in understanding the model's scores and embeddings.

- Cause: The output of foundation models, such as log-likelihood scores for variants or high-dimensional embeddings, can be complex to interpret biologically.

- Solution:

- For Variant Scoring (Zero-Shot): When using

zero_shot_score.pyin PlantCaduceus, the output is a log-likelihood ratio. A lower (more negative) score indicates that the alternative allele is less likely than the reference, suggesting a potentially more deleterious mutation [19]. The script supports different aggregation methods (max,average,all) for analyzing alternative alleles. - For Sequence Embeddings: The embedding from PlantCaduceus has a bi-directional architecture. The first half corresponds to the forward sequence and the second half to the reverse complement. For downstream analysis, these should be averaged:

averaged_embeddings = (forward + reverse) / 2[19]. These embeddings can then be used for clustering, visualization with UMAP (as done in the original paper), or as input to classifiers [18].

- For Variant Scoring (Zero-Shot): When using

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Cross-Species Gene Annotation Using PlantCaduceus

Objective: Accurately predict functional elements (e.g., splice sites) in a target crop species using a model fine-tuned on a model organism.

Principle: This protocol leverages the evolutionary conservation learned by PlantCaduceus during its pre-training on multiple angiosperms. A classifier is trained on embeddings from a well-annotated species (e.g., Arabidopsis) and applied to a poorly annotated species (e.g., maize) [18].

Workflow for Cross-Species Annotation

Steps:

- Data Preparation: Format your labeled data from the source species (e.g., Arabidopsis) and unlabeled sequences from the target species into a tab-separated values (TSV) file, specifying sequences and their labels.

- Embedding Extraction: Use the pre-trained PlantCaduceus model (weights frozen) to generate embeddings for all sequences in your training and target datasets.

- Classifier Training: Train an XGBoost model on the embeddings extracted from the labeled source species data.

- Prediction: Use the trained XGBoost classifier to predict labels for the target species sequences based on their PlantCaduceus embeddings.

Key Considerations:

- This method relies on the model's inherent understanding of evolutionary conservation. Its performance will be higher for species closely related to those in the pre-training set but has been shown to work for species diverged by up to 160 million years [18].

- The XGBoost model is trained only on the source species data, requiring no labels from the target species.

Protocol: Zero-Shot Scoring of Genomic Variants

Objective: Prioritize deleterious mutations across the genome without task-specific training.

Principle: This protocol uses the model's inherent sequence modeling capability. The model evaluates how likely a sequence is with and without a variant; a large drop in likelihood for the alternative allele suggests a deleterious effect [18] [19].

Steps:

- Input Preparation:

- For Specific Variants: Prepare a VCF file containing the variants of interest.

- For Genome-Wide Scanning: Prepare a BED file defining the genomic regions you wish to scan.

- Run Scoring Script: Execute the

zero_shot_score.pyscript provided with PlantCaduceus [19].

- Interpret Results: Analyze the output file. For VCF mode, scores are added to the INFO column. Lower (more negative) log-likelihood ratios indicate higher predicted deleteriousness.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational tools and resources essential for working with foundation models in plant genomics.

| Resource Name | Type | Function/Purpose | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| PlantCaduceus Models | Pre-trained Foundation Model | Provides base embeddings for DNA sequences and enables zero-shot variant scoring and fine-tuning for various tasks. | kuleshov-group/PlantCaduceus_l32 on HuggingFace [19] |

| XGBoost | Machine Learning Library | Used as a downstream classifier on top of frozen model embeddings for tasks like TIS and splice site prediction [18]. | Python package xgboost |

| Zero-Shot Scoring Script | Analysis Pipeline | Facilitates the evaluation of variant effects without task-specific training by calculating log-likelihood scores [19]. | zero_shot_score.py in PlantCaduceus repository [19] |

| Pre-trained XGBoost Classifiers | Task-Specific Model | Offers ready-to-use models for common annotation tasks, saving time and computational resources for fine-tuning. | Available in PlantCaduceus classifiers directory [19] |

| In-silico Mutagenesis Pipeline | Analysis Pipeline | Allows for large-scale simulation and analysis of genetic variants to study their potential effects. | Found in PlantCaduceus pipelines directory [19] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My CNN model for leaf disease classification is not achieving high accuracy. What could be wrong? A common issue is a dataset that is too small or lacks diversity, making the model prone to overfitting and unable to generalize. Ensure your dataset is large and varied enough to cover different disease stages, lighting conditions, and plant varieties [20]. Using data augmentation techniques (like rotation, flipping, and color adjustments) and leveraging transfer learning with a pre-trained model (e.g., ResNet, VGG) can significantly improve performance [20] [21].

Q2: How can I make my deep learning model feasible for use on mobile devices in the field? Traditional models like VGG or ResNet can be computationally intensive. To deploy models on resource-constrained devices, consider using lightweight architectures specifically designed for efficiency. The HPDC-Net is an example of a compact model that uses depth-wise separable convolutions and channel-wise attention to achieve high accuracy with a minimal number of parameters, making it suitable for CPUs and mobile deployment [21].

Q3: My model's predictions are not trusted by domain experts. How can I make it more interpretable? The "black box" nature of complex models can hinder trust. To address this, integrate Explainable AI (XAI) techniques into your workflow. You can use tools like SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to generate saliency maps. These maps visually highlight the regions of an input image (e.g., specific leaf lesions) that were most influential in the model's decision, making its reasoning more transparent and interpretable for scientists [20].

Q4: What is the best way to manage and collect phenotypic data for training these models? Manual data collection can be error-prone. Utilizing specialized, cross-platform digital tools can greatly enhance data quality and efficiency. The GridScore app, for instance, allows for efficient data collection by providing a visual overview of field plots, supports barcode scanning, GPS georeferencing, and data type validation, reducing errors and streamlining the process of building a high-quality dataset [22].

Q5: I am getting poor results when applying my model to images taken in real-field conditions. How can I improve robustness? Models trained on clean, lab-style images often fail in the field due to varying backgrounds, occlusions, and lighting. Improve robustness by:

- Training on diverse data: Include images taken directly in field conditions with complex backgrounds [20].

- Using advanced architectures: Models like Res2Next50 and Faster-RCNN have shown robustness for tasks like disease detection and localization in complex environments [21].

- Focusing on data quality: The significant disparities in image quality (illumination, sharpness, occlusions) are a major challenge; ensuring your training data reflects this variability is key [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Overfitting in Plant Disease Classification Model

Problem: Your model performs well on training data but poorly on unseen validation or test images.

Diagnosis: The model has learned the noise and specific patterns of the training set instead of generalizable features.

Solution:

| Step | Action | Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Data Augmentation | Artificially expand your dataset by applying random transformations: rotation, horizontal/vertical flip, brightness/contrast adjustment, and scaling [20] [21]. |

| 2 | Apply Regularization | Use techniques like Dropout layers or L2 regularization within your network to prevent complex co-adaptations on training data. |

| 3 | Use Transfer Learning | Start with a pre-trained model (e.g., ResNet, EfficientNet) and fine-tune it on your plant dataset. This leverages features learned from a much larger dataset (e.g., ImageNet) [20]. |

| 4 | Simplify the Model | If your dataset is small, reduce the model's complexity (number of layers or parameters) to decrease its capacity to overfit [21]. |

Issue: Low Inference Speed on Resource-Constrained Hardware

Problem: Model is too slow for real-time disease classification on a smartphone or edge device in the field.

Diagnosis: The model architecture is too heavy, with a high number of parameters and computational requirements (GFLOPs).

Solution:

| Step | Action | Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Choose a Lightweight Model | Adopt architectures designed for efficiency, such as HPDC-Net, MobileNetV2, or SqueezeNet [21]. |

| 2 | Model Compression | Apply techniques like pruning (removing insignificant weights) or quantization (reducing numerical precision of weights) to a pre-trained model. |

| 3 | Benchmark Performance | Evaluate the model's speed in Frames Per Second (FPS) on your target hardware (CPU/GPU). For example, HPDC-Net achieved 19.82 FPS on a CPU [21]. |

| 4 | Optimize Architecture | Incorporate efficient operations like depth-wise separable convolutions, which significantly reduce parameters and computation compared to standard convolutions [21]. |

Robust Phenotyping Workflow

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Implementing a Lightweight CNN for Leaf Disease Classification

This protocol outlines the steps to implement the HPDC-Net architecture, a model designed for high accuracy and low computational cost [21].

- Data Preparation: Collect a dataset of leaf images (e.g., from PlantVillage). Split into training, validation, and test sets. Apply preprocessing: resize images to a consistent input size and normalize pixel values.

- Model Architecture: Construct the HPDC-Net using its three core blocks:

- DSCB (Depth-wise Separable Convolution Block): For efficient feature extraction.

- DAPB (Dual-Path Adaptive Pooling Block): For fusing features at different scales.

- CARB (Channel-Wise Attention Refinement Block): To weight important feature channels.

- Training: Compile the model with an Adam optimizer and categorical cross-entropy loss. Train on a GPU, monitoring validation accuracy to avoid overfitting.

- Evaluation: Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set. Report accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. Benchmark inference speed (FPS) on both GPU and CPU.

Performance Comparison of CNN Models for Plant Phenotyping

The table below summarizes the performance of various models as reported in recent literature, highlighting the trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency.

| Model Name | Primary Task | Reported Accuracy | Computational Efficiency | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPDC-Net [21] | Tomato/Potato leaf disease classification | >99% | 0.52M parameters, 0.06 GFLOPs, 19.82 FPS (CPU) | Lightweight, designed for edge devices |

| ResNet-9 [20] | Multi-species pest & disease classification | 97.4% | Not specified | Used with SHAP for model interpretability |

| EfficientNetV2_m [20] | Apple leaf disease detection | ~100% | Not specified | High performance on controlled datasets |

| Res2Next50 [20] | Tomato leaf disease detection | 99.85% | Computationally intensive | High accuracy on curated data |

| Faster-RCNN (ResNet-34) [21] | Tomato disease localization & classification | ~99% | High computational demand | Capable of detecting and localizing diseases |

Essential Tools and Datasets for Plant Phenotyping Research

| Item Name | Type | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| GridScore [22] | Data Collection App | Cross-platform tool for accurate, efficient, and georeferenced phenotypic data collection in field trials. |

| Plant-Phenotyping.org Datasets [24] | Benchmark Data | Finely-grained annotated image datasets for developing and validating plant segmentation and phenotyping algorithms. |

| TPPD Dataset [20] | Specialized Image Data | Turkey Plant Pests and Diseases dataset with 4,447 images across 15 classes of pests and diseases for six plants. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [20] | Analysis Library | Explainable AI (XAI) tool that creates saliency maps to interpret and explain predictions made by deep learning models. |

| HPDC-Net Code [21] | Model Architecture | Open-source code for a lightweight hybrid CNN model, facilitating deployment on resource-constrained devices. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary challenges when integrating genomic, transcriptomic, and phenomic data? The main challenges include achieving data interoperability across different platforms and formats, addressing spatial and temporal biases in data collection, and integrating in-situ observations with remote sensing data effectively [25]. Additional hurdles involve managing the heterogeneity and high dimensionality of the data and the need for substantial computational resources [26] [27].

2. Which computational architecture is best suited for multi-modal data integration and prediction? The Dual-Extraction Modeling (DEM) architecture is a state-of-the-art, deep-learning approach specifically designed for heterogeneous omics data. It uses a multi-head self-attention mechanism and fully connected feedforward networks to extract representative features from individual omics layers and their combinations, leading to superior performance in both classification and regression tasks for complex traits [26]. For a serverless, cloud-based approach, architectures leveraging tools like AWS HealthOmics, Amazon Athena, and SageMaker provide a scalable environment for preparing and querying genomic, clinical, and imaging data [28].

3. How can I standardize my diverse datasets for integration? Standardization involves two key processes:

- Data Harmonization: Align data from different sources onto a common scale or reference, often using domain-specific ontologies [27].

- Data Standardization: Ensure data is collected and processed consistently using agreed-upon standards like Darwin Core for biodiversity data or other community-accepted protocols [25] [27]. This also includes normalization to account for differences in sample size or concentration and batch effect correction [27].

4. What is the difference between pattern models and mechanistic mathematical models?

- Pattern Models (Data-Driven): These models, which include many machine learning and statistical approaches, test hypotheses about spatial, temporal, or relational patterns between system components. They are excellent for finding correlations from large datasets (e.g., clustering expression data) but do not typically establish causation [4].

- Mechanistic Mathematical Models (Theory-Driven): These models describe the underlying chemical, biophysical, and mathematical properties of a biological system (e.g., using ordinary differential equations). They aim to explain how a system behaves based on its core structure and processes, allowing for hypothesis testing and prediction even without exhaustive data [4] [29].

5. Why is a systems biology approach starting with phenomics recommended? Starting with phenomics—the unbiased study of a large number of expressed traits—allows you to see the intertwined biological processes that lead back to genetic and metabolic associations. This approach captures pleiotropic effects (where one gene influences multiple traits) and helps distinguish causal pathways from secondary effects, providing a more clinically relevant starting point for understanding drug efficacy or complex diseases [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Predictive Performance of Integrated Model

Problem: Your multi-omics model shows low accuracy when predicting phenotypic outcomes.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Data Preprocessing Issues | Check for unnormalized data, batch effects, or features with high null-value proportions. | Preprocess data by removing low-variance features, imputing missing values, and applying robust scaling [26] [27]. |

| Incorrect Model Architecture | Evaluate if a simple model (e.g., linear) performs similarly, indicating under-fitting. | Switch to or incorporate a more powerful architecture like DEM [26] or a multi-head self-attention network that can capture global feature dependencies. |

| Failure to Capture Omics-Specific Information | Test models trained on single-omics data. If they perform well, the integration method may be the issue. | Implement a dual-stream architecture like DEM, which first models each omics type independently before performing integrated modeling, thus preserving omics-specific signals [26]. |

Issue 2: Inability to Identify Biologically Meaningful Genes or Pathways

Problem: Your model predicts phenotypes accurately but lacks interpretability and fails to pinpoint functional genes.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Use of a "Black Box" Model | Confirm that the model does not provide feature importance scores. | Apply post-hoc interpretation methods. For instance, shuffle feature values and compare the prediction performance against the model with actual values; high-ranking features that cause significant performance drops are likely important [26]. |

| Lack of Morphological Validation | Check if predictions are based solely on molecular data without cellular validation. | Integrate high-content morphological profiling like NeuroPainting, an adaptation of the Cell Painting assay for neural cells. This can reveal cell-type-specific morphological signatures that correlate with transcriptomic changes [31]. |

Issue 3: Data Integration and Workflow Breakdown

Problem: The process of ingesting, transforming, and storing multi-modal data is inefficient and error-prone.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of a Unified Data Lake | Check if data is siloed across different locations and formats. | Implement a centralized data lake architecture using cloud solutions (e.g., Amazon S3). Use infrastructure-as-code (IaC) for automated, reproducible deployment of ingestion pipelines [28]. |

| Manual and Non-Reproducible ETL/ELT Processes | Review if data transformation steps are documented and scripted. | Utilize scalable, serverless ETL services like AWS Glue to prepare, catalog, and transform genomic, transcriptomic, and imaging data into a query-friendly format (e.g., Parquet) [28]. |

Comparison of Multi-Modal Data Integration Methods

The table below summarizes key computational methods for integrating multi-modal data, highlighting their applications and strengths.

| Method / Architecture | Data Types Supported | Key Function | Key Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dual-Extraction Modeling (DEM) | Genomics, Transcriptomics, other Omics | Phenotypic prediction & functional gene mining | Multi-head self-attention; Dual-stage extraction; Superior accuracy & interpretability | [26] |

| NeuroPainting | Transcriptomics, High-content Imaging (Phenomics) | Morphological profiling in neural cells | Adapted Cell Painting; ~4000 morphological features; Links molecular changes to cellular phenotype | [31] |

| AWS Multi-Omics Guidance | Genomics, Clinical, Mutation, Expression, Imaging | Data ingestion, storage, & large-scale analysis | Serverless (AWS HealthOmics, Athena); Scalable data lake; Infrastructure as Code (IaC) | [28] |

| Species Distribution Models & Machine Learning | Species Occurrence, Trait Data, Environmental Variables | Biodiversity modeling & prediction | Uses Darwin Core standards; Predicts impacts of environmental drivers | [25] |

| mixOmics (R)/INTEGRATE (Python) | Multi-Omics | Data integration analysis | Toolkit for omics integration; Effective for dimension reduction and multi-modal data exploration | [27] |

Experimental Protocol: Integrating Transcriptomics and Phenomics with NeuroPainting

This protocol details a method for uncovering cell-type-specific morphological and molecular signatures by combining transcriptomic data with high-content imaging, as used in studies of the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome [31].

Cell Culture and Differentiation

- Material: 44 human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) lines (22 with 22q11.2 deletion, 22 matched controls).

- Method: Differentiate iPSCs into relevant neural cell types (e.g., neuronal progenitor cells, neurons, astrocytes) using established protocols [31].

- Plating: Plate cells in 384-well microplates at optimized densities:

- iPSCs: 10,000 cells/well, fix 24 hours post-plating.

- NPCs: 15,000 cells/well, fix 24 hours post-plating.

- Neurons: 2,500 cells/well, fix 25 days post-plating.

- Astrocytes: 3,000 cells/well, fix 48 hours post-plating.

- Randomization: Randomize plate maps to ensure equal distribution of genotypes and cell lines across plates, minimizing technical variation.

NeuroPainting Staining and Imaging

- Staining: Adapt the Cell Painting assay for neural cell types using six dyes: Hoechst (DNA), MitoTracker (mitochondria), Phalloidin (actin cytoskeleton), among others, to stain various cellular compartments.

- Imaging: Image plates using a high-content imaging system (e.g., Perkin Elmer Phenix) at 20x magnification.

Image Analysis and Feature Extraction

- Software: Use CellProfiler to create an analysis pipeline optimized for neural cell types.

- Segmentation: Segment cells, nuclei, and cytoplasm based on the respective stains.

- Feature Extraction: Quantify over 4,000 morphological features related to:

- AreaShape: Size and shape of cellular components.

- Granularity & Texture: Patterns of organelle organization.

- Intensity & Radial Distribution: Staining intensity and its distribution within the cell.

- Data Reduction: Preprocess the data by:

- Removing low-variance features.

- Applying robust standardization (median absolute deviation).

- Performing rank-based inverse normal transformation.

- Applying correlation-based feature selection to eliminate redundancy, resulting in ~700 features for downstream analysis.

Transcriptomic Analysis

- RNA Sequencing: Perform RNA sequencing on the same cell lines and types.

- Differential Expression: Identify genes with significantly reduced or increased expression in 22q11.2 deletion samples compared to controls.

Data Integration and Analysis

- Correlation: Integrate RNA sequencing data with NeuroPainting morphological data to pinpoint specific gene expression changes (e.g., in cell adhesion genes) that correlate with observed morphological phenotypes (e.g., mitochondrial disruption) [31].

- Validation: Compare findings with post-mortem brain data to validate the biological relevance of the integrated signatures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function in Multi-Modal Integration |

|---|---|

| Human iPSCs | Provides a patient-derived, disease-relevant cellular system for modeling genetic disorders in various cell types [31]. |

| NeuroPainting Dye Cocktail | Stains multiple organelles (DNA, mitochondria, ER, cytoskeleton) to generate high-dimensional morphological profiles [31]. |

| CellProfiler Software | Open-source software for creating customized image analysis pipelines to extract thousands of morphological features [31]. |

| Darwin Core Standards | A standardized framework for sharing biodiversity data, enabling interoperability between species occurrence, trait, and environmental datasets [25]. |

| AWS HealthOmics | A managed service for storing, analyzing, and querying genomic and other omics data at scale, simplifying data management in the cloud [28]. |

| Dual-Extraction Modeling (DEM) Software | User-friendly deep-learning software for predicting phenotypes and mining functional genes from heterogeneous multi-omics datasets [26]. |

Workflow Diagrams

Multi-Modal Data Integration and Analysis Workflow

Dual-Extraction Modeling (DEM) Architecture

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the most advanced tools for predicting RNA-binding protein (RBP) binding sites, and how do I choose between them?

Answer: For predicting RBP binding sites, deep learning-based webservers are the most advanced. A key tool is RBPsuite 2.0, which offers a significant upgrade from its previous version [32].

The table below compares its features to help you select the right option:

| Feature | RBPsuite 1.0 | RBPsuite 2.0 |

|---|---|---|

| Supported RBPs | 154 human RBPs [32] | 223 human RBPs (351 across all species) [32] |

| Supported Species | Human only [32] | 7 species: Human, Mouse, Zebrafish, Fly, Worm, Yeast, Arabidopsis [32] |

| circRNA Prediction | CRIP method [32] | iDeepC method (improved accuracy) [32] |

| Key Features | Basic binding site prediction [32] | Binding site prediction, motif contribution scores, and UCSC genome browser track visualization [32] |

Troubleshooting: If your model organism is not human, you must use RBPsuite 2.0. For studies on circular RNAs (circRNAs), the updated iDeepC engine in RBPsuite 2.0 provides more reliable predictions [32].

FAQ 2: I work with plant species. Why do standard lncRNA identification tools perform poorly, and what is the recommended solution?

Answer: Standard tools (e.g., CPAT, LncFinder, PLEK) are often trained on human or animal data and fail to capture the unique characteristics of plant lncRNAs, leading to inaccurate identification [33].

The solution is to use tools retrained on plant-specific data. The Plant-LncPipe pipeline integrates the two best-performing retrained models, CPAT-plant and LncFinder-plant, which significantly improve prediction accuracy for plant transcripts [33].

Troubleshooting Guide:

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High false positive rate in lncRNA identification. | Tool trained on non-plant genomic features. | Use the plant-specific Plant-LncPipe pipeline [33]. |

| Inconsistent results across different plant species. | Lack of generalization in the model. | Ensure you are using the ensemble method within Plant-LncPipe, which combines CPAT-plant and LncFinder-plant for robust performance [33]. |

FAQ 3: How can I functionally validate the binding of an RBP to a lncRNA predicted by computational tools?

Answer: Computational predictions should be validated experimentally. Here is a standard protocol for validating RBP-lncRNA interactions using RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP), a method successfully used to confirm predictions from tools like RBPsuite [32].

Experimental Protocol: RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP)

- Cell Lysis and Preparation: Harvest your plant cells or tissues and lyse them using a mild lysis buffer to preserve protein-RNA interactions.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate the cell lysate with an antibody specific to your RBP of interest. Include a control with a non-specific IgG antibody.

- Bead Capture: Add protein A/G beads to capture the antibody-RBP complex and any bound RNAs.

- Washing: Wash the beads extensively with buffer to remove non-specifically bound RNAs.

- RNA Extraction and Purification: Isolve and purify the RNA that is bound to the RBP.

- Analysis: Convert the purified RNA to cDNA and perform quantitative PCR (qPCR) to detect the presence of the specific lncRNA. For a genome-wide approach, the purified RNA can be used for high-throughput sequencing (RIP-Seq).

The following workflow diagram illustrates this process:

FAQ 4: What tools can I use for the functional perturbation of lncRNAs to study their role in plant biology?

Answer: Beyond identification, studying lncRNA function requires perturbation tools. The table below lists key reagent solutions for loss-of-function and gain-of-function studies.

Research Reagent Solutions for lncRNA Functional Studies

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application in Plant Research |

|---|---|---|

| Lincode siRNA | Precision knockdown; chemically modified for high specificity and reduced off-target effects [34]. | Silencing specific lncRNAs to study their role in processes like immune response [34]. |

| SMARTvector Inducible shRNA | Sustained, doxycycline-regulated knockdown using lentiviral delivery [34]. | Creating stable plant cell lines for temporal control of lncRNA silencing. |

| CRISPR/dCas9 Systems | Targeted gene regulation without cutting DNA [34]. | CRISPRi to repress and CRISPRa to activate lncRNA transcription in its native genomic context [34]. |

| cDNA/ORF Clone Libraries | Overexpression of specific lncRNA isoforms [34]. | Functional dissection of domain-specific effects of lncRNA isoforms. |

The logical relationship between perturbation tools and experimental outcomes can be visualized as follows:

Data Presentation Tables

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of RBPsuite 2.0's Expanded Coverage. This table summarizes the significant increase in data coverage, which enhances model robustness and generalizability [32].

| Species | Genome Version | Number of Supported RBPs | Primary Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | hg38 | 223 | POSTAR3 CLIPdb [32] |

| Mouse | mm10 | Included in 351 total | POSTAR3 CLIPdb [32] |

| Zebrafish | danRer11 | Included in 351 total | POSTAR3 CLIPdb [32] |

| Fly | dm6 | Included in 351 total | POSTAR3 CLIPdb [32] |

| Worm | ce11 | Included in 351 total | POSTAR3 CLIPdb [32] |

| Arabidopsis | TAIR10 | Included in 351 total | POSTAR3 CLIPdb [32] |

| Yeast | sacCer3 | Included in 351 total | POSTAR3 CLIPdb [32] |

Table 2: Advantages of Plant-Specific LncRNA Identification Models. This table compares the performance of standard models versus plant-retrained models, demonstrating the critical importance of species-specific training for model accuracy [33].

| Model | Training Data | Key Advantage | Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPAT-plant | Plant transcriptomes | Significantly improved precision for plant lncRNAs [33] | Plant lncRNA identification |

| LncFinder-plant | Plant transcriptomes | Top performer on multiple evaluation metrics [33] | Plant lncRNA identification |

| Plant-LncPipe | Integrates multiple models | Ensemble pipeline for identification, classification, and origin analysis [33] | Comprehensive plant lncRNA analysis |

Overcoming Practical Hurdles: Data, Architecture, and Computational Efficiency

Confronting Data Scarcity and Heterogeneity in Plant Sciences

FAQs: Core Data Challenges

FAQ 1: What are the primary forms of data heterogeneity in modern plant science? Modern plant breeding and research generate massive, high-dimensional data from a gamut of sources, leading to significant heterogeneity. The most significant data types include [35]:

- Genomic Data: Related to the structure, function, evolution, mapping, and editing of genomes (DNA and RNA).

- Phenotypic Data: Related to morphological and functional plant traits (growth, yield, architecture). The collection protocols for this data are often fragmented and lack global standards.

- Farm Management Metadata: Information on practices and technologies used, such as seeding depth, crop rotations, and input application dates.

- Geospatial Data: Site-specific information associated with precision agriculture, such as soil characteristics and yield.

- Telematics Data: Operational data collected from field equipment and machinery via sensors and positioning systems. This heterogeneity presents challenges in integration, manipulation, and interpretation, requiring sophisticated analytical tools and management facilities [35].

FAQ 2: Where is data scarcity most pronounced in global food production systems? Data scarcity is most acute in livestock, fisheries, and aquaculture sectors at both national and local levels [36]. Geographically, the most significant scarcity is observed in developing regions, including Central America, sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa, and parts of Asia [36]. This is concerning because these regions often coincide with areas facing acute food insecurity. The scarcity is driven by challenges such as inadequate financial and human resources to conduct regular agricultural censuses or surveys, and the inherent difficulty and cost of collecting accurate data for mobile fisheries and livestock [36].

FAQ 3: How can I improve the robustness and replicability of my complex plant biology experiments? Robustness—the capacity to generate similar outcomes under slightly different conditions—is crucial for biological relevance. To enhance it [2]:

- Systematically Investigate Protocol Variations: Identify which steps in your protocol are critical and which can be buffered against minor changes. For example, in split-root assays, factors like nitrate concentration, photoperiod, and recovery period duration can vary significantly between published studies while still producing the core foraging phenotype.

- Extend the Level of Detail in Methods: Document not just what was done, but which aspects of the protocol were optimized versus those that were habitual or arbitrary. This information is decisive for the success of future replication efforts.

- Adhere to FAIR Principles: Make your data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable to support replicability and collaborative science [35] [2].

FAQ 4: What computational approaches help integrate heterogeneous multi-omics data?

- Genome-Scale Metabolic Network Reconstruction: This approach uses genome annotation to predict functional cellular network structures, providing a mechanistic framework for interpreting genomic, transcriptomic, and metabolomic data. It helps place molecules into a pathway and network context, supporting biochemical interpretation [37].

- Machine Learning and Computational Statistics: These methods are essential for mining vast amounts of multi-dimensional data, finding patterns, and driving integration strategies to achieve a systems-level understanding [37].

- Entity Resolution and Data Fusion: From computer science, these systematic solutions address value-level heterogeneity by identifying different descriptions of the same real-world entity (e.g., a protein across databases) and fusing them into a single, unified representation [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Data Heterogeneity for Model Integration

Problem: Computational models of plant metabolism yield inconsistent or unreliable predictions when fed with heterogeneous data from disparate sources.

| Observed Issue | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Model fails to validate against experimental data. | Structural heterogeneity: Underlying data schemas and formats are incompatible. | Apply schema mapping techniques to resolve structural differences and align data representations [38]. |

| Inability to link genomic and phenotypic data. | Value-level heterogeneity: The same entity (e.g., gene ID) has different representations across databases. | Implement entity resolution algorithms to group different descriptions of the same real-world entity [38]. |

| Unified data view remains inconsistent after integration. | Conflicting values for the same attribute from different sources. | Employ data fusion methodologies to resolve conflicts and create a single, coherent representation from the grouped entities [38]. |

| Model is overly sensitive to minor parameter changes. | Lack of robustness testing; model may be fine-tuned to a specific, narrow dataset. | Test the model's robustness by varying input parameters and protocol assumptions, ensuring it simulates the right behavior for the right reasons [2]. |

Data Integration Workflow for Robust Modeling

Troubleshooting Experimental Data Scarcity

Problem: A lack of timely, granular, and transparent data is hindering field-level interventions and modeling for crop improvement.

| Observed Issue | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Missing data for key crops in specific regions. | Lack of recent agricultural censuses or surveys due to resource constraints [36]. | Leverage complementary remote sensing and satellite-based data collection to fill spatial and temporal gaps [36]. |

| Inability to target food security interventions. | Data is available only at the national level, lacking local granularity [36]. | Advocate for and participate in open data initiatives and build local capacity for fine-grained data collection and management. |

| Livestock or aquaculture data is unreliable. | Data collection is cost-prohibitive, and methods are difficult to reproduce [36]. | Develop and adopt standardized, low-cost protocols for data collection in these sectors, potentially using novel sensor technologies. |

| Single-cell analyses are limited to model species. | Technical challenges in applying single-cell methods to non-model species, including cell wall dissociation [39]. | Invest in developing universal methods for cell or nucleus isolation and processing to democratize single-cell technologies for environmental species [39]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Split-Root Assay for Investigating Systemic Signaling

This protocol, used to study nutrient foraging in Arabidopsis thaliana, exemplifies a complex multi-step experiment where variations can challenge replicability and robustness [2].

1. Objective: To discern local versus systemic root responses by dividing the root system and exposing each half to different nutrient environments.

2. Key Materials and Reagents:

- Plant Material: Sterilized seeds of Arabiana thaliana (e.g., Col-0 wild-type).

- Growth Media: Solid agar media with defined nitrate concentrations. Typical "High Nitrate" (HN) media uses 5-10 mM KNO₃, while "Low Nitrate" (LN) media uses 0.05-1 mM KNO₃ or a replacement like KCl [2].

- Sucrose: Often added at 0.3% - 1% to the media as a carbon source [2].