Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS): Principles, Current Research, and Strategic Imperatives for Long-Duration Space Missions

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS) as essential technologies for sustainable human presence in space.

Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS): Principles, Current Research, and Strategic Imperatives for Long-Duration Space Missions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS) as essential technologies for sustainable human presence in space. It explores the foundational ecological principles of these closed-loop systems, which integrate producers, consumers, and decomposers to regenerate oxygen, water, and food. The content examines current methodological approaches from international programs, addresses critical troubleshooting challenges for system optimization, and validates technologies through comparative analysis of ground-based and flight experiments. Designed for researchers, scientists, and technology development professionals, this review synthesizes the latest advancements in BLSS research and identifies strategic knowledge gaps requiring urgent investment to enable future Moon and Mars missions.

Ecological Foundations and Historical Development of BLSS

Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS) represent a transformative approach to sustaining human life in long-duration space missions by mimicking Earth's natural ecological processes. These closed-loop systems integrate biological and technological components to regenerate air, water, and food through the continuous recycling of waste products. This technical guide examines the core principles, theoretical frameworks, and experimental methodologies underpinning BLSS research and development. As space agencies worldwide prepare for sustained lunar habitation and Mars exploration, BLSS technologies have become increasingly critical for reducing dependence on Earth-based resupply and enabling true operational autonomy in space environments.

Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS) are engineered ecosystems designed to sustain human life in isolated environments by regenerating essential resources through biological processes [1]. Unlike physical/chemical life support systems that rely on finite consumables, BLSS create self-sustaining environments where waste products from one species become resources for others, mirroring Earth's biogeochemical cycles [2]. The fundamental objective of BLSS is to achieve maximum closure of mass exchange cycles—particularly for carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, and nitrogen—there dramatically reducing the need for external resupply missions which become prohibitively expensive and complex for long-duration missions beyond low-Earth orbit [3] [4].

The historical development of BLSS has evolved through several decades of research, beginning with early Soviet and American space programs. Notable milestones include the Soviet BIOS-1, BIOS-2, and BIOS-3 projects in the 1960s-1970s [2], NASA's Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems (CELSS) program in the 1980s-1990s [3], the Biosphere 2 project in the 1990s [5], and the European Space Agency's ongoing MELiSSA (Micro-Ecological Life Support System Alternative) program [6]. More recently, China's Beijing Lunar Palace has demonstrated significant advancements, supporting a crew of four analog taikonauts for a full year using integrated bioregenerative systems [3]. Current research focuses on optimizing these systems for specific mission profiles, including lunar orbital stations, Martian surface habitats, and potential interstellar voyages.

Core Theoretical Principles of BLSS

Foundational Ecological Concepts

BLSS operation is governed by several interconnected ecological principles that ensure system stability and functionality. At its core, a BLSS is a closed ecological system (CES) that "does not rely on matter exchange with any part outside the system" [2]. This fundamental characteristic necessitates that any waste products generated by one species must be utilized by at least one other species within the system [2]. For instance, human metabolic wastes (carbon dioxide, urine, feces) must be continuously converted into oxygen, food, and water through biological processes performed by other system components.

The principle of mass closure represents perhaps the most critical design requirement for BLSS. In these systems, the mass (food/air/water) required by organisms must be continually recycled from the waste mass produced by those same organisms [7]. While energy and information may be transferred across system boundaries, matter must be conserved and regenerated internally. This closed-loop recycling drastically reduces the need for resupply missions. Research indicates that for missions exceeding two years in duration, it becomes more mass-efficient to regenerate essential substances internally rather than relying on external supplies from Earth [6].

Another foundational concept is autotrophic integration, which stipulates that a closed ecological system "must contain at least one autotrophic organism" [2]. While both chemotrophic and phototrophic organisms are plausible, virtually all BLSS implementations to date have relied on photoautotrophs such as green algae and higher plants [2]. These organisms serve as the primary producers that convert light energy into chemical energy, fixing carbon dioxide and producing oxygen and biomass that support heterotrophic components including humans.

System Architecture and Component Integration

Effective BLSS design requires careful integration of multiple subsystems that perform specific regenerative functions. These systems work synergistically to create a balanced ecosystem that can support human life indefinitely. The major functional components include:

Atmosphere Revitalization Systems manage the critical gaseous exchanges between crew and photosynthetic organisms. Higher plants consume carbon dioxide and produce oxygen through photosynthesis, while simultaneously transpiring water vapor that can be condensed and purified [5] [4]. Microbiological components, such as those in the MELiSSA loop, can further enhance these processes by breaking down carbon dioxide into usable oxygen through specialized bioreactors [6].

Water Recycling Systems recover and purify water from multiple sources, including urine, humidity condensate, and wastewater. These systems employ advanced filtration, sterilization, and sometimes biological processing using constructed wetlands to convert waste water into clean water for drinking, hygiene, and irrigation [5] [4]. In Biosphere 2, for example, wastewater from all human uses and domestic animals was treated and recycled through a series of constructed wetlands, with the resulting water being reused for agricultural irrigation [5].

Food Production Systems typically employ controlled environment agriculture (CEA) techniques such as hydroponics and aquaponics to cultivate edible crops without soil [6]. These systems provide not only nutrition but also contribute to atmospheric regeneration and water purification. Higher plants in BLSS serve multiple functions: they produce edible biomass, generate oxygen, absorb carbon dioxide, recycle water, and contribute to psychological well-being [5] [4].

Waste Processing Systems manage both liquid and solid wastes through biological and physicochemical processes. Microbial communities break down organic matter, while composting systems convert solid waste into nutrient-rich soil amendments [4]. The integration of waste processing directly with food production creates a continuous cycle where "waste" becomes resource, exemplifying the ecological principle of nutrient cycling.

Table 1: Mass Flow Interactions in BLSS Components

| System Component | Inputs Received | Outputs Produced | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher Plants | CO₂, Water, Nutrients, Light | O₂, Food, Biomass, Water Vapor | Air revitalization, food production, water transpiration |

| Microbial Bioreactors | Organic Waste, CO₂ | O₂, Nutrients, CO₂ | Waste processing, gas balancing |

| Water Recovery System | Wastewater, Humidity | Clean Water, Brine | Water purification, recycling |

| Human Crew | O₂, Food, Water | CO₂, Urine, Feces, Waste Heat | System drivers, operators |

BLSS Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

BLSS Development Pathway

The research and development of BLSS follows a structured, phased approach that progresses from fundamental component studies to fully integrated system demonstrations. This developmental pathway ensures that technologies mature sufficiently before implementation in human-rated systems [5]. The standard research progression involves:

Unit Process Studies investigate individual biological and physicochemical processes in isolation. These foundational experiments examine specific phenomena such as plant growth in simulated microgravity, microbial waste processing efficiency, or gas exchange rates under various environmental conditions [5]. Research at this stage focuses on optimizing individual parameters before integrating components into more complex systems.

Artificial Ecosystem Research combines multiple biological components to create simplified analog ecosystems. These experiments examine interactions between species and the emergent properties of communities without immediate human application. Examples include aquarium ecospheres and bottle gardens that demonstrate basic principles of closed ecological systems [2].

Integrated System Testing connects biological and technological components into functional loops that approximate full BLSS operation. The MELiSSA project, for instance, has developed a multi-compartment continuous system where the metabolic outputs of one compartment become inputs for another [6]. These integrated tests identify system-level challenges such as feedback dynamics, buffer requirements, and control strategies.

Human-Rated Testing represents the final experimental phase before space implementation. Facilities like Biosphere 2 [5], the Chinese Lunar Palace [3], and earlier Soviet BIOS systems [2] have enabled long-duration human habitation experiments within closed ecological systems. These large-scale tests validate system performance, human factors, and operational protocols with actual crews.

Experimental Protocols for BLSS Component Verification

Protocol 1: Plant Growth Optimization in Controlled Environments

This protocol evaluates the performance of candidate plant species for BLSS applications, measuring key parameters including biomass production, gas exchange rates, and nutritional quality.

- Select candidate species based on nutritional value, growth characteristics, and environmental requirements. Common candidates include wheat, potatoes, lettuce, and soybeans [5].

- Establish controlled growth environments with precise regulation of temperature (20-25°C), relative humidity (60-70%), light intensity (300-600 μmol/m²/s photosynthetically active radiation), photoperiod (16-18 hours light), and CO₂ concentration (1000-1200 ppm) [4].

- Implement cultivation systems using hydroponic or aeroponic techniques with optimized nutrient solutions. The Nutrient Film Technique (NFT) is commonly employed for leafy greens, while deep water culture may be used for larger plants [6].

- Monitor growth parameters daily, including plant height, leaf area, and visible symptoms. Measure biomass accumulation weekly through destructive sampling of representative plants.

- Quantify gas exchange using infrared gas analyzers to measure photosynthetic and transpiration rates. Calculate oxygen production and carbon dioxide consumption per unit area and time.

- Analyze nutritional content at harvest, assessing carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, vitamins, and minerals. Compare with human nutritional requirements for extended space missions.

- Evaluate system inputs including water, nutrients, and energy required per unit of edible biomass produced.

Protocol 2: Water Recycling System Efficiency Testing

This protocol validates the performance of water recovery subsystems in BLSS, focusing on closure of the water cycle and quality of recycled water.

- Configure test stand with wastewater collection, processing units, and storage reservoirs. Systems typically include membrane filters, biological processors, and chemical treatment units [5].

- Prepare input stream simulating crew wastewater, including urine (with appropriate synthetic analogs), humidity condensate, hygiene water, and cleaning solutions.

- Operate system continuously with daily monitoring of key water quality parameters: pH, conductivity, total organic carbon (TOC), ammonia, nitrate, and microbial counts.

- Measure recovery efficiency by comparing input and output volumes, accounting for process losses and water incorporated into biomass.

- Verify water purity through comprehensive chemical and microbiological analysis, ensuring compliance with spaceflight potable water standards.

- Assess system stability through long-duration operation (minimum 90 days) with periodic challenges simulating normal operational variations and potential failure scenarios.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics for BLSS Subsystems

| Subsystem | Performance Metrics | Target Values | Measurement Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Growth | Edible biomass yield (g/m²/day) | 20-40 g/m²/day (leafy greens) 10-20 g/m²/day (crops) | Destructive sampling, fresh/dry weight |

| Photosynthetic rate (μmol CO₂/m²/s) | 15-30 μmol/m²/s | Infrared gas analysis | |

| Water use efficiency (g biomass/L water) | 3-6 g/L | Transpiration measurement, mass balance | |

| Atmosphere Revitalization | O₂ production (g/m²/day) | 15-25 g/m²/day | Gas exchange measurement |

| CO₂ consumption (g/m²/day) | 20-35 g/m²/day | Gas exchange measurement | |

| Gas concentration stability | O₂: 19-23%, CO₂: 0.1-0.5% | Continuous gas monitoring | |

| Water Recovery | Water closure rate (%) | >95% recovery | Mass balance calculations |

| Contaminant removal efficiency | >99.9% for key pathogens | Chemical/microbiological assay | |

| Energy efficiency (kWh/L) | <0.1 kWh/L | Power monitoring |

Key Technologies and Research Reagents

Essential Research Equipment and Technologies

BLSS research requires specialized equipment to monitor and control the complex interactions within closed ecological systems. The Controlled Closed-Ecosystem Development System (CCEDS) represents an advanced approach that integrates multiple sensor arrays and actuators to maintain system stability [7]. Key technological components include:

Environmental Monitoring Systems track critical parameters including temperature, humidity, light intensity, atmospheric composition (O₂, CO₂, trace gases), water quality, and pressure. NASA's CCEDS technology employs cloud-based monitoring of sensor arrays across multiple ecosystems in real time, enabling long-term observation of sustainability experiments [7].

Controlled Environment Chambers provide precise regulation of growth conditions for biological components. These chambers typically include programmable lighting systems (often using LED arrays with specific spectral qualities), temperature and humidity control, CO₂ injection systems, and nutrient delivery mechanisms [4].

Hydroponic and Aquaponic Systems enable soil-less cultivation of plants, which is essential for space applications. These systems include nutrient film technique (NFT) channels, deep water culture (DWC) tanks, aeroponic misters, and associated pumping and aeration equipment [6].

Gas Analysis Equipment monitors the critical gaseous exchanges within BLSS. Infrared gas analyzers measure CO₂ concentrations, while paramagnetic or electrochemical sensors track O₂ levels. Gas chromatography systems identify and quantify trace gases that could accumulate to toxic levels in closed environments [5].

Water Quality Monitoring Systems ensure the safety and recyclability of water within BLSS. These systems typically include sensors for pH, conductivity, oxidation-reduction potential (ORP), dissolved oxygen, and specific ions. More advanced systems incorporate flow injection analysis or spectrophotometric methods for nutrient monitoring [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for BLSS Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Solutions | Provide essential minerals for plant growth | Hoagland's solution, Modified Knop's solution, Yamazaki nutrient formula |

| Microbial Media | Culture beneficial microorganisms for waste processing | R2A agar, Reasoner's 2A broth, specific methanogenic media |

| Water Quality Testing | Monitor and maintain water purity in closed loops | Hach test kits, HPLC standards for organic contaminants, microbial detection kits |

| Gas Standards | Calibrate atmospheric monitoring equipment | Certified CO₂ in air standards (100-5000 ppm), O₂ in N₂ standards (15-25%) |

| Plant Growth Regulators | Modulate plant development in confined spaces | Gibberellic acid, auxins (IAA, NAA), cytokinins (BA, kinetin) |

| Sterilization Agents | Control microbial contamination in closed systems | Hydrogen peroxide, sodium hypochlorite, peracetic acid solutions |

| Soil/Substrate Analogs | Simulate extraterrestrial growth media | JSC-1A lunar regolith simulant, MMS Mars simulant, baked clay aggregates |

Future Research Directions and Challenges

The advancement of BLSS technology faces several significant challenges that represent key research frontiers. Radiation effects on biological systems in deep space remain poorly understood and require extensive investigation [3]. The complex interplay between microgravity or partial gravity and biological processes presents another critical research area, particularly regarding long-term effects on plant growth, microbial community dynamics, and ecological stability [8].

System closure and stability represent ongoing challenges, as achieving and maintaining near-complete closure of mass cycles requires sophisticated control strategies and redundancy. Current research focuses on developing adaptive algorithms that can predict and manage the nonlinear dynamics of these complex systems [7]. The integration of biological and technological systems also needs refinement, particularly in balancing the resilience of biological systems with the reliability of engineered components.

Emerging research directions include the development of biological in-situ resource utilization (BISRU) approaches that would leverage local resources such as lunar or Martian regolith for agricultural purposes [8]. The challenge of Martian soil toxicity, particularly due to perchlorates, requires innovative mitigation strategies for successful surface agriculture [8]. Additionally, personalized BLSS approaches that tailor life support to individual metabolic and nutritional needs represent a promising frontier for optimizing system efficiency.

The geopolitical dimension of BLSS development has gained prominence, with current analysis indicating that "China has surpassed the US and its allies in both scale and preeminence of these emerging efforts and technologies" [3]. This competitive landscape underscores the strategic importance of BLSS research for future leadership in human space exploration. As missions evolve toward "endurance-class" deep space operations, the maturation of bioregenerative life support will become increasingly critical for sustaining human presence beyond Earth orbit.

The development of Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS) represents a critical endeavor for enabling long-duration human space exploration, transitioning from Earth-reliant resupply missions to self-sustaining extraterrestrial habitats. These systems are closed-loop ecosystems that rely on biological processes to regenerate essential resources—including oxygen, water, and food—by recycling waste materials [9] [10]. The historical trajectory of BLSS development has evolved from isolated national programs into increasingly collaborative international efforts, driven by both technical challenges and geopolitical dynamics. This paper examines this evolution through the lens of strategic capability development, analyzing how past decisions continue to shape current capabilities and future prospects for human exploration of the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

The Foundation: National Programs (1960s-1990s)

Early American Initiatives

The United States established foundational BLSS research through several key programs beginning in the latter half of the 20th century. The Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems (CELSS) program initiated by NASA served as the cornerstone for American bioregenerative research, focusing on the integration of biological components for resource recovery [11] [3]. This evolved into the Bioregenerative Planetary Life Support Systems Test Complex (BIO-PLEX), a habitat demonstration program designed to test integrated life support technologies [11]. Concurrently, the NASA Lunar-Mars Life Support System Test Project successfully demonstrated a growth chamber that contributed to air revitalization and food requirements for a crew of four for 91 days [10].

The theoretical foundation for these systems recognized that long-duration space habitation would require simultaneous revitalization of atmosphere, purification of water, and generation of human food, primarily through photosynthetic higher plants and algae, combined with physicochemical and bioregenerative processes for waste recycling [9].

Soviet/Russian Programs

The Soviet Union pursued parallel development through the BIOS series of facilities, beginning with BIOS-1 in 1965 and evolving through more advanced versions (BIOS-2, BIOS-3, and BIOS-3 M) [10]. These facilities established early proof-of-concept for closed ecological systems, with BIOS-3 achieving notable closure experiments during the 1970s. The Russian approach emphasized rigorous mathematical modeling of mass flows within closed systems and pioneered the integration of human crews into these ecosystems for extended durations.

Comparative Analysis of Early National Programs

Table 1: Comparison of Major Historical BLSS Programs

| Program | Lead Nation | Time Period | Key Achievements | Primary Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CELSS/BIO-PLEX | USA | 1980s-2000s | Development of controlled environment agriculture; system integration concepts | Food production & oxygen regeneration |

| BIOS Series | USSR/Russia | 1965-1990s | Human-in-the-loop testing; mathematical modeling of closed ecosystems | Complete ecosystem closure |

| Biosphere 2 | USA | 1991-1994 | Large-scale integrated ecosystem testing; identified unpredictable closure effects | Earth ecology research & space analog |

| CEEF | Japan | 1990s-2000s | Integration of animal & plant compartments; gas balance monitoring | Balanced ecosystem development |

The Transition Period: Strategic Shifts and Their Consequences (2000-2010)

A pivotal transition occurred in the early 2000s, when strategic priorities and funding allocations dramatically shifted. In 2004, following the release of NASA's Exploration Systems Architecture Study (ESAS), the agency made the consequential decision to discontinue and physically demolish the BIO-PLEX habitat demonstration program [11] [3]. This decision reflected a strategic pivot toward physical/chemical life support systems and away from comprehensive bioregenerative approaches.

The consequences of this strategic shift were profound. With the United States stepping back from BLSS development, leadership in this critical domain transferred internationally. China's space program strategically absorbed and advanced the very technologies that NASA had discontinued [11]. Published NASA BIO-Plex plans subsequently supported the China National Space Administration's (CNSA) efforts to rapidly establish a bioregenerative habitat technology program, which materialized in the form of the Beijing Lunar Palace [11] [3].

During this same period, the European Space Agency established the Micro-Ecological Life Support System Alternative (MELiSSA) program in 1989, focusing on BLSS component technology through international collaboration across research institutions [12] [10]. However, this program never approached the comprehensive closed-systems human testing pursued by other nations.

The Contemporary Landscape: Internationalization and Capability Gaps

China's Ascendancy in BLSS Development

China has emerged as the global leader in bioregenerative life support technology through systematic, sustained investment. The Beijing Lunar Palace (Lunar Palace 1) program has achieved remarkable milestones, including supporting a crew of four analog taikonauts for a full year within a closed-system environment that successfully demonstrated atmosphere, water, and nutrition recycling [11] [3] [13].

The Lunar Palace 365 project (2017-2018) represented a particularly significant achievement, with eight volunteers completing a 370-day mission in the LP1 facility divided into three phases with crew rotations [13]. This project provided invaluable data on system stability, microbial dynamics, and human factors in prolonged isolation.

Current International Initiatives

The contemporary landscape features two major international lunar exploration initiatives with distinct partnerships and technological approaches:

Artemis Accords (led by NASA and the U.S. State Department): With 55 signatory countries as of June 2025, this framework extends the 1967 Outer Space Treaty principles while emphasizing international cooperation and private sector participation [11] [3].

International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) (led by China and Russia): Established as a competing vision for lunar exploration and utilization, with BLSS technology representing a cornerstone capability [3].

Table 2: Comparison of Current BLSS-Related International Initiatives

| Initiative | Leading Agencies | Primary BLSS Approach | Key BLSS Assets | Notable Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artemis Program | NASA & international partners (ESA, JAXA) | Primarily physical/chemical with bioregenerative research | Planned bioregenerative components | Ongoing research; limited integrated testing |

| ILRS | CNSA & Roscosmos | Comprehensive bioregenerative systems | Lunar Palace 1 & expansions | 370-day closed human habitation mission |

| MELiSSA | ESA & international partners | Component-focused bioregenerative technology | MELiSSA Pilot Plant (MPP), PaCMan | Compartmentalized testing; no full human integration |

Persistent Technological Gaps

The transition away from BLSS research has created significant capability gaps for the United States and its partners. Currently, no official programs outside China are pursuing a fully integrated, closed-loop bioregenerative architecture for establishing lunar or Martian habitats [11] [3]. The European Space Agency's MELiSSA program, while productive, remains focused on component technology rather than integrated system demonstration [11].

These gaps pose strategic risks for future "endurance-class" deep space missions, particularly regarding knowledge of deep space radiation effects on biological systems and the scaling of bioregenerative solutions to support multi-year missions without resupply [11].

Experimental Methodologies in BLSS Research

Ground-Based Analog Testing

BLSS development relies extensively on ground-based analog facilities that simulate space mission conditions while allowing for controlled experimentation and system validation. The Lunar Palace 365 experiment exemplifies this approach, with its 160 m² facility containing multiple integrated compartments: two plant cabins, a comprehensive cabin (with private bedrooms, living room, bathroom, and insect culturing room), and a solid waste treatment cabin [13].

The standard methodology involves:

- Long-duration human occupancy with monitoring of physiological and psychological parameters

- Comprehensive mass balance accounting tracking inputs and outputs of air, water, and waste streams

- Microbial community monitoring to assess system stability and crew health risks

- Crop production evaluation measuring yield, resource utilization efficiency, and nutritional quality

Microbial Community Analysis

Understanding microbial dynamics in closed systems represents a critical BLSS research area, with implications for both system functioning and crew health. The methodology typically includes:

- Sample Collection: Air dust samples collected via high-efficiency particulate absorbing (HEPA) filters at multiple locations and time points throughout the mission [13].

- DNA Extraction: Microbial community DNA extraction from collected samples using standardized kits.

Sequencing and Analysis:

- 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing to characterize bacterial community diversity and composition

- Shotgun metagenomic sequencing to assess functional potential

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR) to determine absolute abundances of specific microbial targets, including antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) [13]

Data Interpretation: Source tracking analysis to identify origins of airborne microbes (e.g., human-associated vs. plant-associated).

Plant Compartment Research

The plant compartment represents a fundamental BLSS element, requiring species-specific optimization. Research methodologies include:

- Species Selection: Evaluation based on nutritional value, resource requirements, edible-to-waste biomass ratio, and growth characteristics [10].

- Controlled Environment Agriculture: Precise management of temperature, light, humidity, CO₂, and nutrient delivery.

- Performance Metrics: Measurement of photosynthetic efficiency, gas exchange rates, biomass production, and resource consumption.

- Alternative Species Investigation: Research on non-traditional organisms like aquatic bryophytes (mosses) for specialized functions such as biofiltration [12].

BLSS System Architecture and Compartment Flows

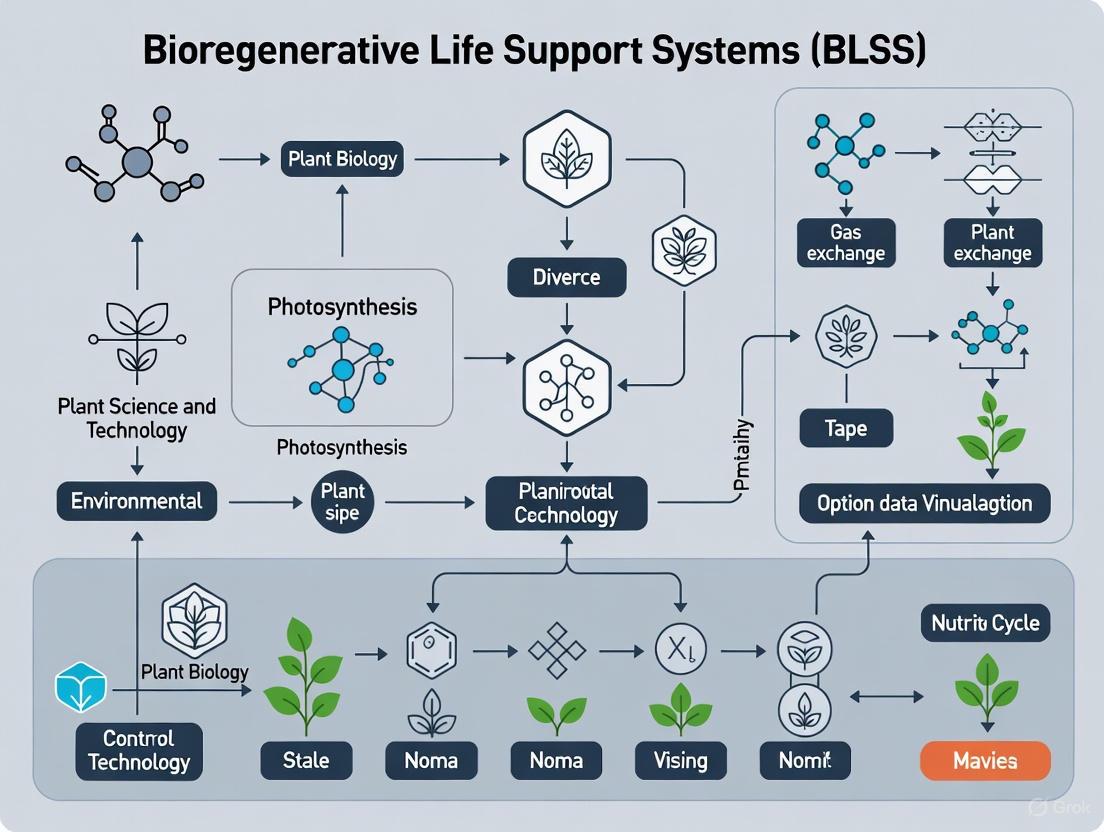

The fundamental architecture of a BLSS consists of interconnected compartments that exchange materials in a closed-loop fashion. The system can be visualized through its mass flows and functional relationships:

BLSS Material Flow Architecture

This diagram illustrates the fundamental material exchanges between BLSS compartments, showing how waste outputs from one compartment become resource inputs for another, creating a sustainable closed-loop system.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

BLSS experimentation requires specialized reagents and materials to monitor system performance and crew health. The following table details key research solutions used in contemporary BLSS investigations:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for BLSS Experimentation

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Example | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| HEPA Filters | Airborne microbial particle collection | Microbial community analysis in habitat air [13] | 0.3 micron particle retention |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Microbial community DNA isolation | Metagenomic analysis of air/ surface samples [13] | Compatibility with complex environmental samples |

| 16S rRNA Primers | Bacterial community profiling | Amplicon sequencing of habitat microbiomes [13] | Target V3-V4 hypervariable regions |

| qPCR Assays | Absolute quantification of specific genes | Antibiotic resistance gene (ARG) monitoring [13] | Include standard curves for quantification |

| Chlorophyll Fluorescence Imaging System | Photosynthetic efficiency measurement | Plant health monitoring under BLSS conditions [12] | Capable of Fv/Fm and ΦPSII measurements |

| Controlled Environment Growth Chambers | Precise plant growth condition maintenance | Crop optimization studies [10] | Temperature, humidity, light, CO₂ control |

| Aquatic Bryophyte Cultures | Biofiltration and resource regeneration | Alternative biological component research [12] | Taxiphyllum barbieri, Leptodictyum riparium |

The historical evolution of Bioregenerative Life Support Systems from national programs to international efforts reveals critical insights about technological leadership in space exploration. Early investments by the United States through the CELSS and BIO-PLEX programs established foundational capabilities that were subsequently discontinued, creating strategic gaps that have been exploited by other nations, particularly China. The current international landscape features distinct pathways—with China demonstrating clear leadership in integrated system testing through achievements like the Lunar Palace 365 mission, while the United States and its partners maintain more fragmented research programs.

Future progress in BLSS development will require reinvigorated international collaboration, sustained investment in integrated ground demonstrations, and resolution of key technical challenges related to system closure, microbial management, and radiation effects on biological systems. The historical pattern suggests that nations which strategically prioritize and consistently fund BLSS capabilities will likely determine the future of sustained human presence beyond Earth orbit.

Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS) are closed-loop systems that rely on biological processes to regenerate essential resources and recycle waste, which is critical for sustaining long-duration human space missions [12]. The development paths of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the China National Space Administration (CNSA) have significantly diverged in this field, creating a distinct strategic geopolitical context. This divergence has profound implications for leadership in human space exploration and the feasibility of future endurance-class missions to the Moon and Mars.

The core function of a BLSS is to achieve a high degree of closure, defined as the percentage of total required resources provided by recycling, thereby reducing dependency on resupply from Earth [14]. This paper examines how historical decisions, funding priorities, and international policies have shaped the current BLSS capabilities of both space agencies, with CNSA having operationalized technologies that NASA once pioneered but later discontinued.

Historical Context and Strategic Divergence

The Foundation and Shift in NASA's BLSS Program

NASA's foundational work in BLSS began with the Controlled Ecological Life Support Systems (CELSS) program, which logically evolved into the ambitious Bioregenerative Planetary Life Support Systems Test Complex (BIO-PLEX) habitat demonstration program [15]. The BIO-PLEX was designed as an integrated, closed-loop habitat testbed for advancing controlled environment agriculture (CEA) to achieve logistical biosustainability for exploration, echoing the goals of even earlier concepts like the 1959 Project Horizon for a lunar base [15].

A critical turning point occurred following the 2004 Exploration Systems Architecture Study (ESAS), which led to the discontinuation and physical demolition of the BIO-PLEX facility [15]. This decision effectively terminated NASA's most advanced integrated BLSS program and marked a strategic shift away from bioregenerative approaches toward reliance on physical/chemical (P/C) life support systems and resupply for the International Space Station (ISS). This shift created a strategic capability gap that has persisted for two decades.

CNSA's Strategic Adoption and Advancement

Concurrent with NASA's retreat from BLSS, the China National Space Administration embarked on a systematic program to develop and mature these very technologies [15]. CNSA synthesized the discontinued NASA research, other international efforts, and domestic innovation to create a robust BLSS initiative. This strategic adoption is most visibly embodied in the Beijing Lunar Palace, a ground-based analog habitat that has successfully demonstrated closed-system operations for atmosphere, water, and nutrition, sustaining a crew of four analog taikonauts for a full year [15].

Table: Historical Timeline of Key BLSS Program Decisions

| Year | NASA Action | CNSA Action | Impact on BLSS Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-2004 | Development of CELSS and BIO-PLEX programs | Monitoring international research and initial planning | NASA held leadership position; CNSA in learning phase |

| 2004 | Discontinuation of BIO-PLEX post-ESAS | Initiation of domestic BLSS development based on NASA research | Critical divergence point; NASA creates strategic gap |

| 2011 | Wolf Amendment restricts bilateral cooperation | Accelerated independent development | Reinforced divergence, limited potential for knowledge exchange |

| 2020s | Focus on P/C systems for Artemis | Operational demonstration of year-long crewed BLSS mission in Lunar Palace | CNSA achieves demonstrated leadership in integrated BLSS |

Current Capability Landscape

Analysis of NASA's Current Posture

NASA's current approach, particularly for the Artemis program and the ISS, relies heavily on resupply of food, water, and other consumables for Physical/Chemical-based Environmental Closed Loop Life Support Systems (ECLSS) [15]. While the ISS's ECLSS processes some water and controls CO₂, it remains a largely open-loop system requiring considerable resupply [14]. The agency's research focus has narrowed, with no current official program pursuing a fully integrated, closed-loop bioregenerative architecture for lunar or Martian habitats [15].

The European Space Agency's (ESA) MELiSSA (Micro-Ecological Life Support System Alternative) program represents a moderate but productive allied effort focused on BLSS component technology, though it has not approached closed-systems human testing at the scale of CNSA's efforts [15].

Analysis of CNSA's Current Posture

CNSA has established a clear lead in both the scale and preeminence of BLSS efforts [15]. The successes of the Beijing Lunar Palace have provided CNSA with invaluable operational data and have validated their bioregenerative technologies for atmosphere revitalization, water recovery, and food production. Published plans from CNSA indicate that these advancements are a core component of their long-term strategy for a sustained human presence on the Moon [15].

This capability directly supports China's broader lunar ambitions, including the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) project, positioning BLSS not merely as a life support technology but as a strategic asset for establishing a permanent extraterrestrial presence.

Table: Comparative Agency Capabilities in BLSS (as of 2025)

| Capability Metric | NASA | CNSA | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrated BLSS Testing | No current integrated human-testing program | Operational demonstration with 4 crew for 1 year (Lunar Palace) | CNSA possesses validated data for system scaling and crew psychology |

| Food Production System | Research & development stage; not mission-critical | Integrated and demonstrated as primary life support component | CNSA has reduced logistics burden for long-duration missions |

| Closed-Loop Water & Air | Relies on P/C systems (ISS); BLSS in R&D | Bioregenerative closure demonstrated in analog habitat | CNSA technology path may offer higher sustainability for bases |

| Lunar Mission Integration | Not part of initial Artemis architecture | Core to announced long-duration lunar habitation plans | Strategic divergence in mission sustainability and operational tempo |

Technical Methodologies in Modern BLSS Research

Experimental Framework for Novel BLSS Components

Recent research has expanded beyond traditional higher plants and algae to investigate non-vascular plants like aquatic bryophytes (mosses) as multifunctional biofilters and resource regenerators. The following methodology, derived from a 2025 study, provides a template for evaluating new biological components for BLSS [12] [16].

1. Research Objective: To characterize the potential of three aquatic bryophytes—Taxiphyllum barbieri (Java moss), Leptodiccyum riparium, and Vesicularia montagnei (Christmas moss)—as biofilters and resource regenerators in BLSS by assessing their physiological and biofiltration performance under controlled conditions [12].

2. Experimental Organisms and Cultivation:

- Species Selection Rationale: T. barbieri for wide adaptability; L. riparium for tolerance to extreme environments; V. montagnei for high surface-area density [12].

- Cultivation Conditions: Specimens are purchased semi-axenic and maintained under two controlled environment regimes to test performance across different potential BLSS configurations [12].

3. Controlled Environment Parameters:

- Condition A (High Light): 24°C and 600 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹.

- Condition B (Low Light): 22°C and 200 μmol photons m⁻² s⁻¹ [12] [16].

4. Key Performance Metrics and Measurement Protocols:

- Gas-Exchange Capacity: Measure photosynthetic rate (CO₂ uptake) and transpiration rate to quantify oxygen production and water recycling potential.

- Chlorophyll Fluorescence: Use pulse-amplitude modulation (PAM) fluorometry to determine the quantum yield of photosystem II (PSII), a key indicator of photosynthetic efficiency and plant health under stress.

- Antioxidant Activity Profiling: Quantify concentrations of antioxidant compounds (e.g., via ORAC assay) to assess the organism's capacity to withstand oxidative stress, a critical factor for space radiation environments.

- Biofiltration Efficiency: Expose moss specimens to aqueous solutions containing known concentrations of nitrogen compounds (e.g., ammonia, nitrates) and heavy metals (e.g., Zinc). Biofiltration efficiency is calculated as the percentage removal of target contaminants over a defined period, analyzed via spectrophotometry or ICP-MS.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents and Materials for BLSS Component Evaluation

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in BLSS Experimentation |

|---|---|

| PAM Fluorometry System | Measures chlorophyll fluorescence to quantify photosynthetic efficiency and photochemical stress in plant candidates. |

| Gas Exchange Chamber (IRGA) | Precisely monitors CO₂ uptake and O₂ release rates to determine gas exchange performance of biological components. |

| ORAC Assay Kit | Quantifies oxygen radical absorbance capacity, evaluating antioxidant strength for radiation stress tolerance screening. |

| ICP-MS (Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry) | Detects and quantifies trace heavy metal uptake (e.g., Zn, Cd) for assessing biofiltration remediation capabilities. |

| Semi-axenic Bryophyte Cultures | Provides standardized, contaminant-controlled plant material for reproducible physiological and biofiltration studies. |

| Controlled Environment Growth Chambers | Maintains precise temperature, humidity, and light levels to simulate different BLSS operational scenarios. |

Geopolitical Factors and Future Trajectories

The Impact of the Wolf Amendment

Enacted in 2011, the Wolf Amendment prohibits NASA from using government funds for direct, bilateral cooperation with the Chinese government and China-affiliated organizations, including CNSA, without explicit authorization from the FBI and Congress [17]. This legislative barrier has systematically limited scientific exchange between American and Chinese researchers in space science, creating a one-way barrier that has reinforced the divergent development paths.

While the amendment includes provisions for case-by-case certifications for activities that do not risk transfer of sensitive technology, it has cast a chilling effect on collaboration [17]. The legislation has been criticized within the scientific community as a "deplorable 'own goal' by the US," as it limits access for U.S. researchers to groundbreaking materials, such as the lunar samples returned by China's Chang'e-6 mission from the far side of the Moon [17].

Competing International Visions

The divergence in BLSS development is set against the backdrop of two competing international lunar exploration frameworks:

- The Artemis Accords: Led by NASA and the U.S. State Department, based on the 1967 Outer Space Treaty and focusing on shared principles for exploration and resource utilization [15].

- The International Lunar Research Station (ILRS): Led by China and Russia, with CNSA's demonstrated BLSS capabilities forming a foundational technological pillar for its long-duration habitation plans [15].

These frameworks represent not only different operational models but also divergent philosophies on sustaining human life in space, with the U.S. favoring a more traditional resupply-based model in the near term, while China pursues a bioregenerative self-sufficiency model.

The diverging paths of NASA and CNSA in Bioregenerative Life Support Systems research represent a critical strategic inflection point in human space exploration. CNSA's focused investment and demonstration of integrated BLSS, leveraging research from discontinued NASA programs, has provided it with a tangible technological advantage in a field essential for long-duration missions and sustainable planetary habitats.

The strategic gap in U.S. BLSS capabilities poses a significant risk to the long-term viability and leadership of NASA and its partners in the Artemis Accords in the emerging era of lunar exploration and beyond. For the United States to maintain international competitiveness and ensure a sustainable pathway for endurance-class human space exploration, it is both necessary and urgent to address these gaps through renewed program investments, strategic international partnerships with allies, and a recommitment to the development of mature, flight-ready bioregenerative technologies.

The functioning of both natural ecosystems on Earth and artificial environments in Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS) hinges on the interplay of three fundamental biological components: producers, consumers, and decomposers. These groups form the foundation of ecological trophic levels, creating a hierarchical structure that facilitates the flow of energy and the cycling of nutrients essential for sustaining life [18]. In BLSS, which are engineered to support human life in space through closed-loop resource regeneration, replicating and optimizing these ecological roles is paramount for achieving system sustainability [19]. These systems are designed to minimize resupply needs from Earth by regenerating oxygen, water, and food through biological processes while recycling waste, thereby creating an artificial ecosystem based on ecological principles [20] [19].

The integration of these biological components represents a critical advancement over purely physicochemical life support systems, particularly for long-duration missions beyond low Earth orbit where resupply becomes economically and technically unfeasible [10] [21]. Organisms within BLSS not only provide multiple life support functions but also possess the ability to reproduce and self-repair, enabling continuous system operation with minimal external input [21]. This whitepaper examines the specific roles, functions, and interactions of producers, consumers, and decomposers within the context of BLSS, providing a technical guide for researchers and scientists engaged in the development of robust life support systems for space exploration.

Producers: The Foundation of Ecosystems and BLSS

Definition and Core Function

Producers, or autotrophs, are organisms that form the base of all ecological trophic pyramids by synthesizing their own food through photosynthesis or chemosynthesis [22] [18]. Through photosynthesis, the most common mechanism relevant to BLSS, producers convert light energy, carbon dioxide (CO₂), and water (H₂O) into chemical energy in the form of glucose (C₆H₁₂O₆) and release oxygen (O₂) as a byproduct [18]. The simplified chemical equation for this process is:

$$ 6CO2 + 6H2O + light \ energy \rightarrow C6H{12}O6 + 6O2 $$

This process not only sustains the producers themselves but also generates the organic matter and oxygen that support all other trophic levels within the ecosystem [22]. In BLSS, producers simultaneously perform multiple essential functions: they revitalize atmosphere by liberating oxygen and fixing carbon dioxide, purify water through transpiration, and generate food for human crew members [9] [10].

Key Organisms and BLSS Applications

In terrestrial ecosystems, producers primarily include green plants, algae, and certain bacteria [18]. In BLSS design, producer selection is guided by mission-specific parameters including duration, available volume, power constraints, and nutritional requirements [10].

Table: Producer Organisms in BLSS Research and Applications

| Organism Type | Specific Examples | Primary Functions in BLSS | Mission Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leafy Greens | Lettuce (Lactuca sativa), Kale | Oxygen production, water purification, supplemental nutrition, psychological benefits | Short-duration missions, LEO platforms [10] |

| Staple Crops | Wheat (Triticum aestivum), Potato, Rice, Soy | Calorie provision, macronutrient production (carbohydrates, proteins), extensive oxygen generation | Long-duration missions, planetary outposts [10] [23] |

| Microalgae | Spirulina platensis, Chlorella vulgaris | Atmospheric revitalization, water recycling, potential food source | Compact systems, auxiliary life support [19] |

| Fruiting Vegetables | Tomato, Peppers, Beans | Nutritional diversity, phytonutrient provision, psychological value | Medium to long-duration missions [10] |

The "vegetable production unit" or "salad machine" concept, designed to supplement astronaut diets with fresh produce, exemplifies the application of producers in near-term missions [10]. For long-duration missions and permanent planetary outposts, staple crops such as wheat, potato, and rice become essential to provide the necessary carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, contributing substantially to overall resource recycling [10].

Experimental Protocols for Producer Research

Protocol 1: Measuring Photosynthetic Efficiency in Controlled Environments This protocol is critical for optimizing plant growth and gas exchange in BLSS.

- Plant Material Selection: Select candidate species (e.g., lettuce, wheat) based on nutritional value and resource requirements [10].

- Environmental Control: Establish growth chambers with precise control of light intensity (PPFD: 200-600 μmol m⁻² s⁻¹), spectral quality, CO₂ concentration (800-1200 ppm), temperature (22-26°C), and relative humidity (60-70%) [10].

- Gas Exchange Measurement: Utilize infrared gas analyzers (IRGA) to measure net CO₂ uptake and O₂ evolution rates. Calculate photosynthetic efficiency as the quotient of assimilated carbon to incident light energy [23].

- Biomass Analysis: Harvest plants at maturity and measure fresh and dry weight to determine biomass production efficiency (g MJ⁻¹) [23].

- Data Application: Use results to model contributions to atmospheric revitalization and food production, informing crop selection and cultivation system design for specific mission scenarios [10].

Consumers: Energy Transfer and Ecosystem Dynamics

Definition and Classification

Consumers, or heterotrophs, are organisms that cannot produce their own energy and must consume other organisms to obtain energy and nutrients [22] [18]. In BLSS, the primary consumers are the human crew members, though other consumer organisms may be incorporated for additional food sources or ecosystem services [23]. Consumers are categorized based on their feeding habits and position in the food chain:

- Primary Consumers (Herbivores): Organisms that consume producers as their energy source. In BLSS, this can include insects or fish cultivated for protein [23].

- Secondary Consumers (Carnivores): Organisms that consume primary consumers. In most BLSS designs, this role is filled by humans, though some systems may incorporate pest control organisms [22].

- Omnivores: Organisms that consume both producers and other consumers. Humans are the quintessential omnivores in BLSS [18].

In the context of BLSS, consumers play a critical role in transferring energy from one trophic level to the next, though this transfer is inherently inefficient, with only about 10% of energy passed from one level to the next due to energy lost as heat during metabolic processes, incomplete consumption, and energy expended in movement and growth [18].

In BLSS, the human crew constitutes the primary consumer group, driving the system's resource requirements. Research focuses on meeting human nutritional needs while minimizing resource inputs. Recent BLSS research has explored integrating insect consumers as a sustainable protein source. Species such as house crickets (Acheta domesticus), yellow mealworms (Tenebrio molitor), and silkworms (Bombyx mori) show promise due to their nutritional value, feed conversion efficiency, and ability to utilize organic waste streams [23]. These organisms can serve as primary consumers (herbivores) or decomposers (detritivores), providing multifunctional roles within the system.

Table: Consumer Organisms in BLSS Research

| Consumer Type | Examples | Trophic Level | BLSS Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Crew | Astronauts | Omnivore (Primary & Secondary) | System driver, waste production | Nutritional requirements, psychological health, metabolic outputs [19] |

| Insects | Acheta domesticus, Tenebrio molitor | Primary Consumer (Herbivore/Detritivore) | Protein production, waste processing | Nutritional profile, growth rate, system compatibility [23] |

| Fish | Tilapia, Other Aquaponics Species | Primary/Secondary Consumer | Protein production, nutrient cycling | Space requirements, water quality management [10] |

The inclusion of non-human consumers remains a subject of ongoing research. While insects offer efficient protein conversion and waste utilization capabilities, they are significantly underrepresented in BLSS literature compared to plant producers, with only about one animal-focused paper published annually versus 4.7 plant-related papers [23].

Experimental Protocols for Consumer Research

Protocol 2: Evaluating Insect Species as Sustainable Protein Sources in BLSS This protocol assesses the viability of insect consumers for resource-efficient protein production.

- Species Selection: Select candidate insect species (e.g., Acheta domesticus, Tenebrio molitor) based on nutritional profile, feed conversion efficiency, and space requirements [23].

- Diet Formulation: Develop diets based on BLSS-generated biomass (crop residues, food waste) and measure consumption rates.

- Growth Performance Monitoring: Track key metrics including: specific growth rate, feed conversion ratio, and mortality rate.

- Nutritional Analysis: Analyze macronutrient and micronutrient composition of harvested insects.

- Waste Output Characterization: Quantify and characterize frass production for integration with decomposer subsystems.

- System Integration Assessment: Evaluate compatibility with other BLSS components.

Decomposers: The Nutrient Recycling Engine

Definition and Critical Function

Decomposers, primarily bacteria and fungi, are organisms that break down dead organic material and waste products, returning essential nutrients to the ecosystem in forms usable by producers [22] [18]. This decomposition process is vital for nutrient cycling, ensuring that elements like nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon are continuously recycled rather than locked in dead biomass [18]. In BLSS, decomposers transform human waste, inedible plant biomass, and other organic wastes into mineral nutrients that can be reused by plants, thereby closing the nutrient loop [10] [19].

Functions of decomposers include:

- Break down dead organisms and waste products

- Release nutrients back into the soil and water

- Help maintain soil fertility and structure [18]

Without decomposers, ecosystems would accumulate dead material, nutrient cycling would cease, and the entire food web would eventually collapse due to nutrient depletion [22] [18]. In BLSS, this function is typically facilitated by microbial bioreactors that efficiently process waste streams while minimizing volume and energy requirements [10].

BLSS Applications and Microbial Communities

Decomposers in BLSS perform the critical function of recycling organic wastes, including inedible plant biomass, food waste, and human metabolic wastes, into inorganic nutrients that can be taken up by plants [19]. The Microbial Ecological Life Support System Alternative (MELiSSA) project, for instance, employs a series of interconnected bioreactors containing specific microbial communities to degrade organic waste and recover nutrients [10]. These engineered microbial communities are designed to mimic the nutrient cycling functions of natural decomposers while operating reliably in controlled environments.

Advanced BLSS concepts explore the use of "soil-like substrates" produced through aerobic fermentation and earthworm treatment, creating a more complex decomposition environment that can enhance nutrient availability and plant growth [19]. The interplay between microbial decomposers and physicochemical waste processing systems is an active area of research, aiming to achieve robust and efficient nutrient recycling with minimal energy input and operational complexity.

Integrated System Dynamics in BLSS

Energy Flow and Nutrient Cycling

In a fully integrated BLSS, producers, consumers, and decomposers form an interconnected network where the outputs of one compartment serve as inputs for another, creating a closed-loop system [10] [19]. Energy flows unidirectionally from producers to various levels of consumers and finally to decomposers, while nutrients cycle continuously between these compartments [18]. This integration can be represented through food chains and more complex food webs that illustrate the multifaceted feeding relationships within the ecosystem [18].

The efficiency of energy transfer between trophic levels is a critical design parameter for BLSS. With only approximately 10% of energy transferred from one trophic level to the next, system design must prioritize shortening food chains and selecting highly efficient producer-consumer relationships to maximize overall system efficiency [18]. This inefficiency explains why most BLSS designs emphasize plant-based diets for human crew members, as introducing animal intermediates reduces the total calories available from the same initial photosynthetic output [10].

Trophic Relationships and System Integration

The following diagram illustrates the integrated relationships and resource flows between the core biological components of a BLSS:

BLSS Integration and Resource Flows

This diagram illustrates the circular flow of resources within a BLSS, where waste outputs from one process become inputs for another, minimizing external resource requirements. The system's closure is maintained through biological processes that continuously regenerate vital resources from waste streams [19].

Research Tools and Methodologies

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

BLSS research requires specialized materials and reagents to study and optimize the biological components of these closed ecosystems. The following table details key research solutions essential for experimental investigations in this field:

Table: Key Research Reagents and Materials for BLSS Component Investigation

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Specifications | Primary Research Application | BLSS Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroponic Nutrient Solutions | Balanced macro/micronutrients (N, P, K, Ca, Mg, Fe, etc.) | Plant growth optimization, nutrient uptake studies | Producer compartment nutrient delivery [10] |

| Microbial Culture Media | Specific media for nitrifying bacteria, decomposer fungi | Decomposer functionality, waste processing optimization | Degradation of organic waste into plant-available nutrients [10] |

| Gas Analysis Standards | Certified CO₂, O₂, CH₄ calibration gas mixtures | Atmospheric composition monitoring, photosynthetic/respiratory gas exchange | Tracking gas fluxes between system compartments [19] |

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits | Commercial kits for microbial/plant molecular analysis | Microbial community characterization, plant gene expression | Monitoring system health and organism responses [23] |

| Insect Artificial Diets | Defined formulations with varying protein/carbohydrate ratios | Insect growth performance, waste conversion efficiency | Evaluating insects as secondary consumers/protein source [23] |

Experimental Workflow for BLSS Component Integration

The following diagram outlines a systematic experimental workflow for evaluating the integration of new biological components into a BLSS:

BLSS Component Testing Workflow

This workflow emphasizes the iterative nature of BLSS development, where biological components must be evaluated at multiple levels of integration before being validated for space applications [10] [19]. The process highlights the importance of ground-based testing in high-fidelity analogs before proceeding to space-based validation, acknowledging the significant differences between terrestrial and space environments that can affect biological performance [19].

The successful implementation of Bioregenerative Life Support Systems for long-duration space missions depends on the sophisticated integration of producers, consumers, and decomposers into a stable, self-sustaining artificial ecosystem. Current research has established a strong foundation in producer biology, with significant knowledge gaps remaining regarding the integration of consumer organisms and the optimization of decomposition processes under space conditions. Future BLSS development will require enhanced focus on multifunctional species that can fulfill multiple roles within the system, advanced monitoring and control systems for maintaining ecological balance, and rigorous testing under space-relevant environmental conditions. By applying ecological principles to engineered systems, BLSS research promises to enable long-term human presence in space while simultaneously advancing our understanding of sustainable life support on Earth.

The pursuit of long-duration human space exploration necessitates technologies that can sustainably support life millions of miles from Earth. Environmental Control and Life Support Systems (ECLSS) encompass the technologies required to maintain a habitable environment for astronauts, providing essential functions including atmosphere revitalization, water recovery, and waste management [24]. Within this domain, two primary philosophical and technical paradigms have emerged: Physicochemical Life Support Systems (PCLSS) and Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS) [24]. A deeper understanding of the theoretical progression from early concepts to modern implementations is crucial for guiding future research and deployment.

The fundamental distinction between these paradigms lies in their core operating principles. PCLSS relies on physical and chemical processes to recycle air, water, and waste. These systems, which are currently operational aboard the International Space Station, are characterized by high efficiency, reliability, and rapid processing times. However, they are not indefinitely sustainable due to their dependence on consumable materials and limited capacity for food production [24]. In contrast, BLSS utilizes biological organisms—such as plants, algae, and microbes—to regenerate life-sustaining resources from waste products. Although these systems can operate more slowly and require more volume, they hold the promise of long-term sustainability and reduced resupply requirements, making them essential for missions to the Moon and Mars [24] [3].

A significant subtype of BLSS is the Closed Ecological Life Support System (CELSS). This framework represents an ambitious endeavor to create a self-sustaining, closed-loop ecosystem within a spacecraft by integrating a diverse array of living and non-living elements. A CELSS aims to mimic Earth's biosphere, where natural processes create a harmonious, self-regulating environment that recycles air, water, and waste while producing food [24]. The historical development of these concepts shows a strategic evolution, with NASA's early CELSS program and subsequent BIO-PLEX initiative paving the way for current advancements, most notably demonstrated by the China National Space Administration's (CNSA) Beijing Lunar Palace, which has sustained crews for extended durations [3].

Core Theoretical Principles and System Components

The CELSS Framework: Mimicking Earth's Biosphere

The CELSS framework is fundamentally rooted in ecological engineering, aiming to replicate the closed-loop material cycles of Earth's biosphere on a small scale. The core theoretical principle is the creation of a closed-material loop where waste products from one subsystem become resources for another, minimizing or eliminating the need for external inputs [24]. This approach goes beyond mere life support; it seeks to create a complex, synergistic system where biological and physicochemical components interact to create a robust and resilient habitat.

Early theoretical work and simulation models, including mass-balance studies, were critical for understanding the stoichiometry of such systems. These models detailed the flows of carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, and nitrogen necessary for the production of plant biomass (both edible and inedible), human consumption, and the processing of human waste [25]. For instance, a steady-state system with wheat as a sole food source was modeled to calculate the precise daily fluxes of these elements required to support a human, thereby defining the theoretical foundation for closed-system operation [25]. The CELSS approach leverages ecosystem archetypes, such as wetland marshes, which are proficient at multiple ecosystem services including air purification, water filtration, and carbon sequestration within anoxic sediments [24].

The Evolution to BLSS/BLiSS: A Modular, Hybrid Approach

The evolution from CELSS to modern Bioregenerative Life Support Systems (BLSS or BLiSS) reflects a pragmatic shift from attempting to replicate entire ecosystems to engineering manageable, highly reliable biological components. The modern BLSS theory often embraces a modular, loop-connected architecture [3]. This is exemplified by the European Space Agency's MELiSSA (Micro-Ecological Life Support System Alternative) program, which is based on interconnected compartments, each housing specific organisms (e.g., nitrifying bacteria, photosynthetic algae, higher plants) that utilize waste from other compartments as essential resources [12]. This compartmentalization enhances system control and stability.

A key theoretical advancement in modern BLSS is the move toward hybrid systems that integrate the best features of both bioregenerative and physicochemical technologies. While biological systems excel at regenerating air, water, and producing food, some physical systems offer more precise, rapid control over certain environmental parameters [24]. For example, a BLSS might use plants for oxygen production and carbon dioxide removal but employ a physical system for rapid temperature and humidity control, which lacks efficient biological solutions [24]. This hybrid approach balances the long-term sustainability of biological systems with the predictability and control of physicochemical systems, thereby mitigating the risks associated with either approach used in isolation.

Comparative Analysis of System Components

The theoretical differences between PCLSS, BLSS, and CELSS become concrete when examining how each addresses the core components of a life support system. The table below provides a detailed comparison of the methodologies employed by each paradigm for critical life support functions.

Table 1: Comparison of Component Technologies Across Life Support System Paradigms

| Component | PCLSS (e.g., ISS) | BLSS | CELSS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atmosphere Control & Supply | Gas storage tanks, adsorption/scrubbing; careful monitoring [24]. | Control of photosynthesis rate in plants/algae; limited trace gas removal [24]. | Control of photosynthesis; soil bed reactors act as microbial air filters for enhanced gas processing [24]. |

| Oxygen Generation | Electrolysis of water [24]. | Photosynthesis by plants in growth chambers or algae in photobioreactors [24]. | Photosynthesis by plants and algae within a diverse ecosystem; must account for oxygen consumption by decomposers/animals [24]. |

| Carbon Dioxide Removal | Adsorption using materials like zeolite [24]. | Absorption by plants/algae during photosynthesis [24]. | Absorption via photosynthesis; wetlands excel at sequestering carbon in anoxic underwater biomass [24]. |

| Water Recovery | Physical filtration and chemical treatment of wastewater, including urine distillation [24]. | Use of liquid waste as dilute fertilizer for plants/algae; mechanical and biological filtration [24]. | Application of waste to wetlands; filtration through integrated mechanical and biological systems [24]. |

| Waste Management | Solid waste stored for disposal; liquid waste processed via Water Recovery System (WRS) [24]. | Composting or breakdown by aerobic/anaerobic bacteria in digesters; resulting compost used for plant growth [24]. | Use of wetlands as natural recyclers of human solid and liquid waste [24]. |

| Food Production | Supply of pre-packaged meals with long shelf life [24]. | Grown in controlled agricultural environments (e.g., hydroponics, aeroponics) [24]. | Produced within interconnected ecosystems; supports symbioses (e.g., aquaculture) for recycling inedible biomass [24]. |

Quantitative Frameworks and Modeling

The design and prediction of BLSS behavior rely heavily on quantitative modeling to ensure mass balance and system stability. Early foundational work established the biochemical stoichiometry for key processes, calculating the daily mass flows of elements required to sustain a human in a closed system. The following table summarizes the mass balance for a simplified wheat-based system, which formed the basis for more complex dynamic simulations [25].

Table 2: Example Mass Balance for a Wheat-Based BLSS (grams/person/day) [25]

| Component | Formula | Human Intake | Human Output | To Waste Processor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon | C | 301.66 | - | 301.66 |

| Hydrogen | H | 42.75 | - | 42.75 |

| Oxygen | O | 476.06 | - | 476.06 |

| Nitrogen | N | 11.46 | - | 11.46 |

| Other (Ash) | - | 19.97 | - | 19.97 |

| Water (H₂O) | - | 1211.00 | 1211.00 | - |

| Urine Solids | - | - | 56.70 | 56.70 |

| Feces Solids | - | - | 29.48 | 29.48 |

| Wash Water Solids | - | - | 21.77 | 21.77 |

Modern modeling has evolved to incorporate advanced data analysis techniques. Quantitative data analysis, powered by descriptive and inferential statistics, is used to analyze structured, numerical data from system experiments, measuring differences between groups and assessing relationships between variables [26] [27]. Furthermore, machine learning models are now being applied to predict the behavior of complex biological systems. For example, hybrid models like SA-CNN-BiLSTM (Self-Attention Convolutional Neural Network-Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory) demonstrate high accuracy in forecasting environmental variables such as water quality, achieving a coefficient of determination (R²) of 0.955 in dissolved oxygen prediction [28]. These models efficiently extract deep features from time-series data and use attention mechanisms to weight key time steps, reducing prediction errors and providing a sophisticated tool for managing the dynamic nature of BLSS [28].

Experimental Research and Novel Biological Components

A Methodology for Evaluating Novel Biofilters

Research into new biological components is vital for advancing BLSS capabilities. A recent study investigating aquatic bryophytes (mosses) as biofilters and resource regenerators provides a robust experimental protocol [12].

Research Objective: To characterize the potential of three aquatic moss species—Taxiphyllum barbieri (Java Moss), Leptodictyum riparium, and Vesicularia montagnei (Christmas Moss)—as multifunctional biological components in BLSS, assessing their photosynthetic performance and biofiltration efficiency [12].

Experimental Protocol:

- Species Selection & Cultivation: Acquire semi-axenic cultures of the three moss species and maintain them in controlled aquatic environments [12].

- Environmental Conditions: Subject the species to at least two distinct controlled condition sets to evaluate adaptability (e.g., Condition A: 24°C and 600 μmol photons m⁻²s⁻¹; Condition B: 22°C and 200 μmol photons m⁻²s⁻¹) [12].

- Performance Metrics:

- Gas-Exchange: Measure rates of CO₂ uptake and O₂ production to quantify atmospheric regeneration capacity [12].

- Chlorophyll Fluorescence: Use parameters such as Fᵥ/Fₘ to assess the functional status and maximum quantum efficiency of Photosystem II, indicating plant health and photosynthetic performance [12].

- Antioxidant Activity: Analyze antioxidant profiles to evaluate the physiological resilience of the mosses to stress [12].

- Biofiltration Efficiency: Quantify the removal rates of specific contaminants from water, including nitrogen compounds (e.g., total ammonia nitrogen) and heavy metals (e.g., Zinc) [12].

- Data Analysis: Employ statistical analysis (e.g., descriptive statistics, ANOVA) to identify significant differences in performance between species and conditions, determining the most suitable candidates for BLSS integration [12].

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials for Bryophyte BLSS Research

| Item | Function in Research Context |

|---|---|

| Semi-axenic moss cultures (T. barbieri, L. riparium, V. montagnei) | Provides the foundational biological material for testing; axenic status reduces confounding variables from other microbes [12]. |

| Controlled Environment Growth Chambers | Enables precise manipulation and maintenance of environmental variables such as temperature, light intensity, and photoperiod [12]. |

| Pulse-Amplitude Modulated (PAM) Fluorometer | The key instrument for measuring chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, providing a non-invasive assessment of photosynthetic health and efficiency [12]. |

| Gas Exchange System | Measures the rates of carbon dioxide absorption and oxygen production by the mosses, directly quantifying their air revitalization potential [12]. |

| Analytical Chemistry Equipment | Used to quantify the concentration of specific contaminants (e.g., ammonia, heavy metals) in water before and after moss treatment to determine biofiltration efficiency [12]. |

Key Findings and Research Outcomes

The experimental results demonstrated a clear divergence in specialist functions among the species, highlighting the value of biodiversity in BLSS design. Taxiphyllum barbieri exhibited the highest photosynthetic efficiency and pigment concentration, marking it as a primary candidate for oxygen regeneration [12]. In contrast, Leptodictyum riparium showed the most effective removal of nitrogen compounds and heavy metals like Zinc, suggesting a complementary role as a specialized water purifier [12]. Vesicularia montagnei contributed valuable data on adaptability. These findings support the utilization of a consortium of bryophytes, rather than a single species, to enhance the overall efficiency and functional robustness of closed-loop ecological systems [12].

System Architecture and Functional Relationships

The logical relationships between human inhabitants, biological components, and engineering systems within a BLSS can be visualized as a network of interdependent processes. The following diagram outlines the core functional workflow and material flows of a generalized BLSS.

The experimental methodology for evaluating biological components, such as aquatic mosses, involves a structured workflow from preparation to data analysis. The diagram below details this multi-stage experimental protocol.

The theoretical journey from the comprehensive, ecosystem-based CELSS framework to the more modular and pragmatic modern BLSS concepts reflects a maturation of the field. This evolution is guided by quantitative mass-balance models, advanced data analysis, and rigorous experimental research into novel biological components like aquatic bryophytes. The current state of the art points toward hybrid systems that leverage the strengths of both bioregenerative and physicochemical technologies to create robust, reliable, and sustainable life support systems. For future "endurance-class" deep space missions, closing the gap between theoretical models and operational, human-rated systems remains the critical challenge. Strategic investment in integrated ground demonstrations is the necessary next step to mature these essential technologies for sustaining human life beyond Earth [3].

System Architectures and Biological Component Integration