Beyond the Noise: Strategies for Robust Sensor Reliability in Low-Data Biomedical Research

This article addresses the critical challenge of ensuring sensor data reliability in low-data scenarios, a common hurdle in preclinical and clinical drug development.

Beyond the Noise: Strategies for Robust Sensor Reliability in Low-Data Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of ensuring sensor data reliability in low-data scenarios, a common hurdle in preclinical and clinical drug development. It provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and scientists, covering the foundational causes of data scarcity, advanced methodological approaches like machine learning for accuracy enhancement, practical troubleshooting for ultralow-level signals, and robust validation techniques. By synthesizing strategies from sensor technology, AI, and data analysis, this guide aims to empower professionals to generate trustworthy, actionable data from limited samples, thereby accelerating and de-risking the R&D pipeline.

The Low-Data Conundrum: Understanding Sensor Reliability Challenges in Biomedical Research

Core Concepts and Definitions

What constitutes a "low-data scenario" in biomedical research?

A low-data scenario occurs when the ability to collect data is physically, ethically, or economically constrained. This primarily encompasses two research contexts:

- Rare Disease Studies: The European Union defines a disease as rare if it affects not more than 5 in 10,000 people. In the United States, a rare disease is one that affects fewer than 200,000 people [1]. The limited patient population naturally restricts sample sizes for clinical trials and biomarker discovery.

- Sparse Clinical Sampling: Situations where frequent biological sampling is impractical, such as when using invasive procedures, monitoring rapidly changing biomarkers, or dealing with expensive analytical techniques.

What are biomarkers and how are they classified?

In medicine, a biomarker is a measurable indicator of the severity or presence of a disease state. More precisely, it is a "cellular, biochemical or molecular alteration in cells, tissues or fluids that can be measured and evaluated to indicate normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacological responses to a therapeutic intervention" [2].

Biomarkers are clinically classified by their application [2] [3] [4]:

- Diagnostic Biomarkers: Used to identify or confirm the presence of a disease or a specific disease subcategory. Example: Levels of Glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) aid in diagnosing traumatic brain injury [2] [4].

- Prognostic Biomarkers: Provide information about the patient's overall disease outcome, regardless of treatment. Example: The presence of a

PIK3CAmutation in metastatic breast cancer is associated with a lower average survival rate, independent of the therapy used [4]. - Predictive Biomarkers: Help assess the likelihood of benefiting from a specific therapy. Example:

EGFRmutation status in non-small cell lung cancer predicts a significantly better response to gefitinib compared to standard chemotherapy [3]. - Pharmacodynamic Biomarkers: Markers of a specific pharmacological response, crucial for dose optimization studies in early drug development [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Low-Data Scenario Challenges

FAQ: How does disease prevalence affect clinical trial sample size?

Q: My research involves a rare disease. How will the low prevalence impact the required sample size for a clinical trial?

A: Disease prevalence has a direct and significant impact on the feasible sample sizes for clinical trials, especially in Phase 3. The following table summarizes the relationship observed from an analysis of clinical trials for rare diseases [1]:

| Prevalence Range (EU Classification) | Typical Phase 2 Trial Sample Size (Mean) | Typical Phase 3 Trial Sample Size (Mean) |

|---|---|---|

| <1 / 1,000,000 | 15.7 | 19.2 |

| 1-9 / 1,000,000 | 26.2 | 33.1 |

| 1-9 / 100,000 | 33.8 | 75.3 |

| 1-5 / 10,000 | 35.6 | 77.7 |

Key Insight: For very rare diseases (prevalence <1/100,000), Phase 3 trials are often similar in size to Phase 2 trials. Larger Phase 3 trials become more feasible only for less rare diseases (prevalence ≥1/100,000) [1].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Precisely Define Prevalence: Determine the exact prevalence of your condition of interest using databases like Orphadata [1].

- Adjust Expectations: Acknowledge that classical frequentist trial designs requiring hundreds of patients may not be feasible.

- Explore Alternative Designs: Consider adaptive trial designs, Bayesian methods, or

N-of-1trials that are better suited for small populations.

FAQ: How can I improve the reliability of sensor data in low-data environments?

Q: The sensor data I collect from wearable devices is often noisy. What are the common errors and how can I correct them to improve reliability for my analysis?

A: Sensor data quality is paramount, especially when sample sizes are small and each data point is valuable. The following table classifies common sensor data errors and solutions [5]:

| Error Type | Description | Common Detection Methods | Common Correction Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outliers | Data points that deviate significantly from the normal pattern of the dataset. | Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | PCA, ANN, Bayesian Networks |

| Bias | A consistent, systematic deviation from the true value. | PCA, ANN | PCA, ANN, Bayesian Networks |

| Drift | A gradual change in the sensor's output signal over time, not reflected in the measured property. | PCA, ANN | PCA, ANN, Bayesian Networks |

| Missing Data | Gaps in the data series due to sensor failure, transmission errors, or power loss. | - | Association Rule Mining, imputation techniques |

| Uncertainty | Data that is unreliable or ambiguous due to environmental interference or sensor-skin coupling effects. | Statistical process control | Signal processing algorithms, adaptive calibration |

Key Insight: For non-invasive sensors, the sensor-skin coupling effect is a major source of error. Variations in skin thickness, moisture, pigmentation, and texture can alter the sensor's readings, leading to measurement uncertainties [6].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Error Identification: First, characterize the primary type of error affecting your data using the methods listed above.

- Implement Detection Algorithms: Apply detection algorithms like PCA or ANN to flag erroneous data segments.

- Apply Correction Techniques: Use appropriate correction methods. For physical sensors, advanced calibration techniques and biocompatible interface materials can mitigate sensor-skin coupling effects [6].

FAQ: What are the key statistical considerations for biomarker discovery with limited samples?

Q: I am discovering a novel prognostic biomarker from a small set of patient tissue samples. What are the key statistical pitfalls and best practices?

A: Working with limited samples increases the risk of overfitting and false discoveries. Rigorous statistical practices are non-negotiable [3].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Pre-specify the Analysis Plan: Define the biomarker's intended use, primary outcome, and statistical hypotheses before conducting the analysis to avoid data-driven, non-reproducible results [3].

- Control for Multiple Comparisons: When testing multiple biomarkers or hypotheses, use methods that control the False Discovery Rate (FDR) to reduce false positives [3].

- Prevent Bias with Blinding and Randomization:

- Blinding: Ensure the personnel generating the biomarker data are unaware of the clinical outcomes to prevent assessment bias.

- Randomization: Randomly assign specimens to testing plates or batches to control for technical "batch effects" [3].

- Validate in an Independent Cohort: Any discovered biomarker must be validated in a separate, independent set of patients to confirm its performance [3].

Experimental Protocols for Low-Data Scenarios

Protocol for Biomarker Discovery and Validation

This protocol outlines a rigorous statistical framework for biomarker development when sample sizes are constrained [3].

Objective: To discover and analytically validate a biomarker for a specific clinical application (e.g., diagnosis or prognosis) using a limited cohort.

Workflow:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Define Intended Use and Population: Clearly state the biomarker's purpose (e.g., prognostic) and the target patient population [3].

- Acquire Archived Specimens: Obtain a well-characterized set of archived specimens that directly represent the target population. The number of samples and "events" (e.g., disease recurrence) must provide adequate statistical power [3].

- Pre-specify Analysis Plan: Before data collection, document the primary outcome, statistical hypotheses, and criteria for success. This prevents results from being influenced by the data [3].

- Generate Biomarker Data with Blinding and Randomization:

- Blinding: Keep laboratory personnel unaware of clinical outcomes to prevent bias.

- Randomization: Randomly assign cases and controls to testing batches to minimize technical batch effects [3].

- Statistical Analysis and Discovery:

- For a prognostic biomarker, test the main effect of the biomarker on the outcome (e.g., using a Cox regression model for survival).

- For a predictive biomarker, a randomized trial is required. Test the interaction between the treatment and the biomarker in a statistical model [3].

- Use metrics like Sensitivity, Specificity, and Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) for evaluation [3].

- Independent Validation: Confirm the biomarker's performance in a separate, independent cohort of patients. This is a critical step to ensure generalizability [3].

Protocol for Mitigating Sensor-Skin Coupling Effects

This protocol addresses data reliability issues arising from the interface between non-invasive sensors and the skin, a common problem in continuous monitoring [6].

Objective: To enhance the reliability and accuracy of non-invasive sensor data by mitigating errors introduced by variable skin properties.

Workflow:

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Characterize the Sensor-Skin Interface: Systematically analyze how key skin properties—such as skin thickness, moisture levels, melanin content (pigmentation), and texture—affect the specific sensor's readings (e.g., magnetic or optical) [6].

- Develop a Biocompatible Interface: Create sensor interfaces using advanced biomaterials that maintain consistent contact and minimize variability across different skin types [6].

- Implement Adaptive Calibration: Develop calibration procedures that can dynamically adjust to individual user physiology. This may involve user-specific baselines or real-time correction algorithms [6].

- Integrate Advanced Signal Processing: Apply algorithms to filter noise, correct for drift, and extract clean physiological signals from the raw sensor data. Techniques may include motion artifact removal and baseline wander correction [6].

- Bench Testing and Validation: Rigorously test the sensor system under controlled conditions that simulate different skin types and environmental challenges to validate performance improvements [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for research in low-data scenarios, particularly focusing on biomarker and sensor reliability [2] [6] [3].

| Category | Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biomarker Types | Genetic Mutations (e.g., EGFR, KRAS) | Serve as predictive biomarkers for targeted therapies in cancer [3] [4]. |

| Proteins (e.g., GFAP, UCH-L1) | Used as diagnostic biomarkers for specific conditions like traumatic brain injury [2] [4]. | |

| Autoantibodies (e.g., ACPA) | Act as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis [2]. | |

| Sensor Types | Giant Magnetoimpedance (GMI) Sensors | Highly sensitive magnetic sensors suitable for detecting weak physiological signals like heart rate [6]. |

| Tunnel Magnetoresistance (TMR) Sensors | Offer high sensitivity for non-invasive cardiac monitoring, capable of recognizing essential signals without averaging [6]. | |

| Analytical Methods | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | A statistical method commonly used for detecting and correcting sensor faults like outliers, bias, and drift [5]. |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | Used for both detecting complex sensor faults and imputing/correcting missing or erroneous data [5]. | |

| Specimen Types | Liquid Biopsy (ctDNA) | A minimally invasive source for biomarker discovery and monitoring, crucial when tissue biopsies are not feasible [3]. |

| Archived Tissue Specimens | A critical resource for retrospective biomarker discovery studies in rare diseases where prospective collection is difficult [3]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Improving Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)

1. Problem Definition: A low Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) makes it difficult to distinguish your true signal from background noise, jeopardizing data integrity. SNR is defined as the ratio of signal power to noise power and is often expressed in decibels (dB) [7] [8].

2. Quantitative Diagnosis: First, measure your SNR to quantify the problem. A common method is to select a region of data where no signal is present, calculate the standard deviation (which represents the noise level, N), and then divide the height of your signal (S) by this noise level [9]. The table below outlines what different SNR values mean for system connectivity and data reliability.

Table: SNR Values and System Performance

| SNR Value | Interpretation & Reliability |

|---|---|

| Below 5 dB | Connection cannot be established; signal is indistinguishable from noise [8]. |

| 5 dB to 10 dB | Below the minimum level for a connection [8]. |

| 10 dB to 15 dB | Minimally acceptable level; connection is unreliable [8]. |

| 15 dB to 25 dB | Poor connectivity [8]. |

| 25 dB to 40 dB | Good connectivity and reliability [8]. |

| Above 40 dB | Excellent connectivity and reliability [8]. |

| ≥ 5 (Linear Scale) | The "Rose Criterion" for imaging; minimum to distinguish image features with certainty [7]. |

3. Improvement Protocols:

- Increase Signal Strength: If possible, amplify the source of your desired signal.

- Reduce Noise: Shield cables and components from electromagnetic interference, use stable power supplies, and control environmental factors like temperature [10].

- Utilize Filtering: Apply digital signal processing filters (e.g., low-pass, band-pass) to remove noise outside the frequency band of your signal.

- Averaging: For repeated measurements, average the results to reduce random noise [9].

Guide 2: Identifying and Compensating for Sensor Drift

1. Problem Definition: Sensor drift is a gradual, often subtle change in the sensor's output over time, causing a discrepancy between the measured and actual physical value [11] [12]. It is a natural phenomenon that affects all sensors and primarily impacts accuracy, not necessarily precision [12].

2. Root Causes:

- Environmental Factors: Exposure to extreme temperatures, humidity, pressure, or airborne contaminants [11] [13] [12].

- Aging and Wear: Long-term use, mechanical stress (vibration, shock), and aging of internal components or electrolytes [11] [13].

- Power Supply Variations: Instability in the supply voltage can alter the sensor's operating point [13].

3. Mitigation and Compensation Protocols:

- Regular Calibration: The primary method to correct for drift. Schedule calibrations based on sensor criticality and vendor guidelines [12].

- Hardware Compensation: Utilize temperature compensation circuits, thermistors, or optimized bridge designs to counteract drift at the component level [13].

- Software Compensation: Employ algorithms to correct data in post-processing.

- Polynomial Fitting: Models the nonlinear relationship between the drift (e.g., due to temperature) and the sensor output [13].

- Machine Learning: Tools like APERIO DataWise can train models on historical data to detect and alert on drift anomalies in real-time, even in complex multi-sensor systems [11].

- Sensor Redundancy: Install multiple sensors with staggered calibration schedules to ensure at least one calibrated sensor is always active [12].

Table: Sensor Drift Troubleshooting Checklist

| Checkpoint | Action |

|---|---|

| Physical Inspection | Check for contamination, damage, or loose connections [10]. |

| Environmental Check | Verify temperature, humidity, and EMI are within sensor specifications [10] [13]. |

| Power Supply Check | Ensure stable, clean power to the sensor [10]. |

| Signal Test | Use a multimeter or oscilloscope to check for unstable output or distortion [10]. |

| Calibration History | Review records to see if the sensor is past its calibration due date [12]. |

Guide 3: Managing Sensor Cross-Sensitivity and Interference

1. Problem Definition: Cross-sensitivity (or cross-interference) occurs when a sensor responds to the presence of a gas or substance other than its target analyte, potentially leading to false readings or alarms [14] [15].

2. Types of Interference:

- Positive Response: The sensor gives a reading that suggests the target gas is present when it is not, or in a higher concentration [15].

- Negative Response: The presence of an interfering gas reduces the sensor's response to the target gas. This is particularly dangerous as it can mask a hazardous condition [15].

3. Mitigation Protocols:

- Consult Cross-Sensitivity Tables: Always refer to manufacturer-provided tables to understand potential interferents. The values are estimates and can vary with sensor age and environmental conditions [14] [15].

- Use Gas Filters: Install chemical filters that absorb or block common interferents before they reach the sensor [15].

- Optimize Sensor Selection: Choose sensors with known low cross-sensitivity to gases expected in your application environment.

- Data Fusion and Calibration: Use sensor arrays and advanced algorithms to discern the target gas signal from interference. In some cases, calibration using a surrogate gas is necessary [15].

Table: Example Electrochemical Sensor Cross-Interference (% Response) [14]

| Target Sensor | CO (100ppm) | H₂ (100ppm) | NO₂ (10ppm) | SO₂ (10ppm) | Cl₂ (10ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Monoxide (CO) | 100% | 20% | 0% | 1% | 0% |

| Hydrogen Sulfide (H₂S) | 5% | 20% | -40% | 1% | -3% |

| Nitrogen Dioxide (NO₂) | -5% | 0% | 100% | -165% | 45% |

| Chlorine (Cl₂) | -10% | 0% | 10% | -25% | 100% |

Note: A negative value indicates a suppression of the sensor signal. [14]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most important thing I can do to ensure sensor data reliability? Implement a robust and regular calibration schedule, as all sensors drift over time. For critical applications, use redundant sensors calibrated at different times to ensure continuous reliable data [12].

Q2: In low-data scenarios, how can I be confident that a detected peak is a real signal and not noise? A widely accepted rule is the signal-to-noise ratio criterion. If the height of a peak is at least 3 times the standard deviation of the background noise (SNR ≥ 3), there is a >99.9% probability that the peak is real and not a random noise artifact [9].

Q3: My gas sensor is alarming, but I suspect cross-interference. What should I do? First, consult the sensor's cross-sensitivity table from the manufacturer to identify likely interferents [14] [15]. Then, if possible, use a different type of sensor or a gas filter to confirm the reading. Never ignore an alarm, but use this process to diagnose whether it is a true positive or a false alarm.

Q4: Can machine learning help with sensor reliability in complex systems? Yes. Machine learning models can be trained on historical sensor data to 'learn' normal behavior and detect subtle, complex anomalies like gradual drift or interference patterns that may not be apparent to human operators, enabling predictive maintenance and timely alerts [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials and Methods for Sensor Reliability Research

| Item / Method | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Precision Calibration Gas | Provides a known-concentration reference for validating and calibrating gas sensors, essential for quantifying drift and accuracy [14]. |

| Temperature & Humidity Chamber | Allows for controlled stress testing of sensors to characterize and model temperature-induced drift and other environmental effects [13]. |

| Signal Generator & Oscilloscope | Used to inject clean, known signals into sensor systems to measure SNR, response time, and signal integrity independently [10]. |

| Shielded Enclosures & Cables | Mitigates the impact of external electromagnetic interference (EMI), a common source of noise that degrades SNR [10]. |

| Radial Basis Function (RBF) Neural Networks | A software compensation method capable of modeling complex, non-linear sensor drift for more accurate post-processing correction than simple linear models [13]. |

| Machine Learning Platform (e.g., APERIO DataWise) | Provides scalable tools for analyzing historical sensor data to identify drift and anomalies across large sensor networks [11]. |

FAQs: Understanding Missing Data in Longitudinal Research

Q1: Why is missing data particularly problematic for longitudinal predictive models? In longitudinal studies, missing data reduces statistical power and can introduce severe bias, distorting the true effect estimates of interest [16]. For predictive models, this means the model learns from an incomplete and potentially unrepresentative picture of the temporal process, compromising its ability to forecast future states accurately [17]. The model's performance becomes unreliable, whether it's predicting disease progression or sensor readings.

Q2: What are the main types of missing data mechanisms? Understanding why data is missing is crucial for selecting the correct handling method. The three primary mechanisms are:

- Missing Completely at Random (MCAR): The missingness is unrelated to any observed or unobserved data. An example is an equipment malfunction due to a power outage [16] [18]. The remaining data is considered a random subset of the full dataset.

- Missing at Random (MAR): The probability of data being missing is related to other observed variables but not the missing value itself. For instance, in a study, older participants might have more missing follow-up data due to mobility issues, which is an observed characteristic [16] [19].

- Missing Not at Random (MNAR): The missingness is related to the unobserved missing value itself. For example, participants in a health study with worse symptoms may be less likely to attend follow-up visits, and the symptom severity is the missing value itself [16] [19]. This is the most challenging type to handle.

Q3: What are the most common technical causes of missing sensor data? In sensor-based research, data gaps often arise from:

- Hardware Limitations: Missed task deadlines in embedded systems due to slow processing or constrained resources [20].

- Battery Drain: Continuous sensing using GPS, accelerometers, or heart rate monitoring consumes significant power, leading to device shutdown [21].

- Network Failures: Intermittent connectivity can prevent data transmission from the sensor to the cloud or data repository [20].

- Sensor Failure: Devices can fail due to challenging deployment environments [20].

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Solving Missing Data Issues

Phase 1: Diagnosis and Assessment

- Problem: Suspected bias in data collection.

- Troubleshooting Step: Check the integrity of randomization. Compare the characteristics (e.g., age, baseline scores) of participants in different groups using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables [22]. Ensure groups are similar at baseline.

- Problem: High volume of missing data points.

- Troubleshooting Step: Quantify the amount and pattern of missing data. Calculate the percentage of missing values for each variable and each time point. Use visualizations to determine if the missingness is monotone (e.g., all data is missing after a participant drops out) or arbitrary [19].

- Problem: Uncertainty about the missing data mechanism (MCAR, MAR, MNAR).

- Troubleshooting Step: Conduct an analysis to test for MCAR. Compare the distributions of observed variables between cases with complete data and cases with any missing data. If they are significantly different, the data is likely not MCAR [18].

Phase 2: Solution Protocols

Below is a structured guide to selecting and applying methods to handle missing data.

Table 1: Method Selection Guide for Handling Missing Data

| Method | Best For | Procedure | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Listwise Deletion [18] | Data that is MCAR and small amounts of missingness. | Remove any observation (participant) that has a missing value on any variable in the analysis. | Easy to implement but wasteful and can introduce bias if data is not MCAR. |

| Multiple Imputation [16] [19] | Data that is MAR. It is a robust, widely recommended method. | 1. Create multiple (e.g., 5-20) complete datasets by filling in missing values with plausible ones predicted from observed data. 2. Analyze each completed dataset separately. 3. Pool the results across all datasets. | Preserves sample size and statistical power. Accounts for uncertainty in the imputed values. Requires specialized software. |

| Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) [23] | Longitudinal data with correlated repeated measures. | A statistical model that uses all available data from each participant without requiring imputation. It accounts for the within-subject correlation of measurements over time. | Effective for analyzing longitudinal data with missing values, particularly when the focus is on population-average effects. |

| Machine Learning Imputation [20] | Complex datasets with nonlinear relationships. | Use algorithms like k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Random Forest, or FeatureSync to predict and fill in missing values based on patterns in the observed data. | Can capture complex interactions but may be computationally intensive and act as a "black box." |

| Last Observation Carried Forward (LOCF) [18] | Specific longitudinal clinical trials (use is declining). | Replace a missing value at a later time point with the last available observation from the same participant. | Simple but can introduce significant bias by underestimating variability and trends. |

Phase 3: Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Mitigating Sensor Data Loss at Source

This protocol aims to minimize missed data readings from IoT sensors using a real-time operating system (RTOS) [20].

- Implementation: Apply a Fixed Priority (FP) task scheduling system combined with Dynamic Voltage and Frequency Scaling (DVFS) and the Cycle Conserving (CC) method (FP-DVFS-CC) on the embedded device.

- Function: This adaptive system prioritizes critical sensor reading tasks and dynamically adjusts the processor's clock rate and voltage to ensure these tasks are completed before their deadlines, thereby minimizing data loss due to processing delays [20].

- Validation: Monitor the rate of missed task deadlines before and after implementation to quantify the reduction in data loss.

Protocol 2: Predictive Image Regression with Masked Loss

This protocol is for handling missing images in a longitudinal medical imaging sequence, such as brain MRI scans [17].

- Model Architecture: Construct a predictive model that combines a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to encode a baseline image and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks to encode time-varying changes.

- LDDMM Framework: Instead of predicting images directly, the model predicts a "vector momentum" sequence in a mathematical space (LDDMM framework) that parameterizes the deformation of the baseline image over time [17].

- Handling Missingness: During training, apply a binary mask to the loss function. This mask ignores the reconstruction error at time points where the image is missing, allowing the model to learn effectively from incomplete sequences [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Mitigating Missing Data

| Item | Function / Solution Provided | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Imputation Software (e.g., in R or Stata) | Creates multiple plausible versions of the complete dataset to account for uncertainty in imputed values. | The gold-standard statistical method for handling data Missing at Random (MAR) in most research analyses [19]. |

| Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) | Provides a modeling framework for longitudinal data that uses all available data points without imputation, accounting for within-subject correlation. | Analyzing repeated measures studies in public health, clinical trials, and social sciences where follow-up data is incomplete [23]. |

| K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) Imputation | A machine learning algorithm that imputes a missing value by averaging the values from the 'k' most similar complete cases in the dataset. | Multivariate datasets where complex, non-linear relationships between variables exist [18] [20]. |

| FP-DVFS-CC Scheduling | A real-time system scheduling approach that minimizes missed data acquisitions in embedded sensor systems by dynamically managing task priorities and processor power. | IoT and sensor-based research where hardware constraints lead to data loss [20]. |

| LDDMM + LSTM with Masking | An advanced imaging analysis framework that predicts future images in a sequence while being robust to missing time points by ignoring them in the loss calculation. | Longitudinal medical imaging studies (e.g., neurology, oncology) with missing scan data [17]. |

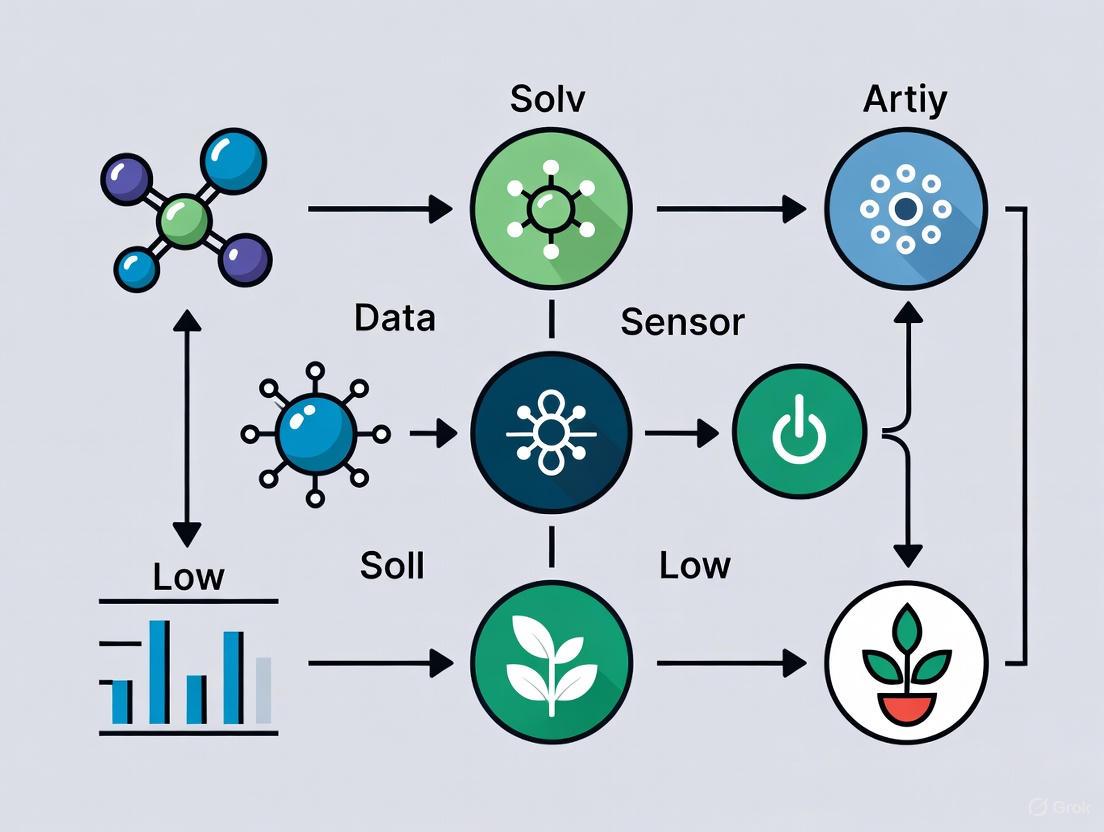

Workflow Diagrams for Missing Data Management

The following diagrams outline a systematic approach to diagnosing and mitigating missing data.

Diagram 1: Diagnostic and Mitigation Workflow for Missing Data. This chart guides the selection of handling methods based on the identified missing data mechanism (MCAR, MAR, MNAR).

Diagram 2: Sensor Data Integrity Pipeline. This diagram illustrates a two-pronged strategy, combining preventative measures in hardware/software with statistical mitigation techniques after data collection to ensure data reliability.

Troubleshooting Guides

Rapid Battery Depletion

Problem: The wearable device's battery depletes faster than the projected operational time, risking critical data loss during long-term monitoring sessions.

Solutions:

- Disable High-Energy Features: Identify and deactivate power-intensive sensors and functions not essential to the current experiment, such as GPS, Wi-Fi, or an always-on display [24]. Background GPS usage alone can reduce battery life by up to 40% [24].

- Adjust Software Settings: Lower screen brightness, reduce screen timeout duration, and enable device-specific power-saving modes to minimize passive drain [24].

- Manage Applications: Uninstall or disable unused applications and background services that consume processor resources and power [24].

- Software Updates: Ensure the device's operating system and applications are updated to the latest versions, as these often include power management optimizations [24].

Inconsistent Sensor Data During Low Power

Problem: Sensor readings (e.g., heart rate, accelerometer) become inaccurate or drop out entirely as battery levels decrease, compromising dataset integrity.

Solutions:

- Optimize Sensor Sampling Rates: If the experimental protocol allows, reduce the frequency at which sensors sample data. A lower sampling rate significantly conserves energy.

- Ensure Proper Device Fit: For optical sensors like heart rate monitors, ensure the device is worn snugly but comfortably on the wrist. Incorrect positioning can affect biometric data accuracy by more than 30% and force the sensor to use more power to acquire a signal [24].

- Clean Sensor Surfaces: Gently clean the sensor surface on the back of the device with a soft, dry cloth to remove sweat, oil, or residue that can interfere with readings and force higher power output [24].

- Implement Pre-Experiment Checks: Establish a protocol to verify battery health and sensor functionality immediately before initiating a data collection run.

Connectivity Failures and Data Syncing Issues

Problem: The wearable device frequently disconnects from data aggregation hubs (e.g., smartphones, base stations), leading to gaps in the collected data stream.

Solutions:

- Re-establish Pairing: Unpair the wearable device from the host system (e.g., smartphone, computer) and then re-pair them to establish a fresh connection [24].

- Verify Proximity and Obstacles: Maintain a clear connection range, typically within 30 feet, and minimize physical obstructions or sources of electromagnetic interference between the device and the host [24].

- Power Cycle Devices: Restart both the wearable device and the host system to resolve temporary software glitches that can disrupt connectivity protocols [24].

- Check Host Power Settings: Ensure the host device's operating system is not restricting background data activity for the companion application, as this can prevent reliable data transfer [24].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the fundamental energy challenges facing wearable devices for research? The core challenge is a significant gap between the energy demands of wearable electronics and the capabilities of current wearable power sources. Consumer wearables like smartwatches require 300–1500 mWh batteries, while most reported flexible batteries feature <5 mWh/cm² energy density. Similarly, low-power microcontrollers need 1–100 mW, but wearable energy harvesters (e.g., from movement or heat) typically harvest <1 mW/cm² [25]. This makes long-term, autonomous operation a major technological hurdle.

Q2: How can I maximize the operational lifespan of my wearable device for a multi-day study? Adopt the "20-80% charging rule" [26]. Avoid letting the battery fully discharge to 0% or consistently charging it to 100%. Keeping the charge within the 20-80% range minimizes stress on the lithium-ion battery, thereby preserving its long-term health and capacity. Furthermore, deactivate all non-essential wireless communications and sensors for the duration of the study.

Q3: Our research involves continuous monitoring. Are energy-harvesting solutions a viable alternative? While promising, current energy harvesters have limitations for rigorous science. They typically provide low areal power (below 5 mW per cm²) and total harvestable energy (often <10 mWh per day), which is insufficient for most low-power wearable applications [25]. Their efficiency is highly dependent on user activity (e.g., constant high-frequency movement), making the energy supply intermittent and unpredictable for a controlled study [25].

Q4: What specific battery technologies are used in cutting-edge wearables like smart patches? Wearable smart patches typically use small, flexible batteries. Common types include [27]:

- Lithium-Polymer (Li-Po) Batteries: Favored for their flexibility and safety.

- Printed Batteries: Ultra-thin and flexible, allowing for integration into the patch substrate.

- Zinc-Air Batteries: Lightweight with high energy density.

Q5: How does battery health impact the accuracy of long-term sensor data collection? A degrading battery can lead to voltage drops and reduced power delivery to sensors. This can manifest as [24] [26]:

- Sensor Drift: Inaccurate or drifting readings from sensors that require stable voltage.

- Data Gaps: Unexpected shutdowns or failure to log data during critical periods.

- Unreliable Connectivity: Weak transmission power causing more data packet loss. Monitoring the battery's State of Health (SoH) is crucial, and a replacement should be considered when SoH drops below 80% [26].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol for Validating Sensor Accuracy Under Power Constraints

Objective: To determine if and how decreasing battery levels affect the accuracy of primary sensors (e.g., photoplethysmography for heart rate).

Materials:

- Wearable device(s) under test.

- Gold-standard reference device (e.g., clinical-grade ECG holter monitor).

- Controlled environment (e.g., lab space).

- Data logging software.

Methodology:

- Fully charge the wearable device and the reference device.

- Fit both devices on the participant according to manufacturer guidelines.

- The participant will perform a structured protocol in a controlled environment:

- Resting (seated, 10 minutes)

- Light activity (walking, 10 minutes)

- Moderate activity (jogging, 10 minutes)

- Simultaneously record data from both the wearable and the reference device.

- Pause the experiment and discharge the wearable device to 50% battery, then repeat step 3.

- Pause again, discharge the wearable to 20% battery, and repeat step 3.

- Data Analysis: For each battery level (100%, 50%, 20%), calculate the mean absolute error and correlation coefficient for the sensor data (e.g., heart rate) between the wearable and the gold-standard device.

Experimental Workflow for Sensor Validation

Methodology for Quantifying Energy Usage per Sensor

Objective: To profile the power consumption of individual sensors on a wearable device to inform experimental design.

Materials:

- Wearable device with accessible sensor controls.

- Precision power monitor (e.g., Joulescope or similar).

- Computer for controlling the device and logging power data.

Methodology:

- Place the wearable device in a baseline state: screen off, all wireless radios (Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, GPS) disabled, and all sensors deactivated.

- Using the precision power monitor, record the baseline current draw for 5 minutes to establish a steady baseline power (P_baseline).

- For each sensor (S) of interest:

- Activate only that sensor with a fixed, predefined sampling rate.

- Allow the system to stabilize for 1 minute.

- Record the current draw for 5 minutes and calculate the average power (Ptotal).

- The power attribution for the sensor is Psensor = Ptotal - Pbaseline.

- Deactivate the sensor.

- Repeat step 3 for all relevant sensors and for different sampling rates if applicable.

- Compile results into a table for future reference when planning study configurations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Materials for Wearable Energy and Sensor Reliability Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Precision Power Monitor/Emulator | Measures minute fluctuations in current draw (down to µA) to accurately profile the energy consumption of individual sensors and device states [25]. |

| Clinical-Grade Reference Devices | Provides gold-standard data (e.g., ECG, actigraphy) against which the accuracy of consumer wearable sensors can be validated at different battery levels [28]. |

| Programmable Environmental Chamber | Controls temperature and humidity to test battery performance and sensor stability under various environmental conditions that mimic real-world use. |

| Flexible Battery Cycling Tester | Characterizes the cycle life, capacity, and internal resistance of small-format flexible batteries used in patches and advanced wearables [27]. |

| Data Logging & Analysis Software | Custom scripts (e.g., in Python/R) for synchronizing timestamps, managing large datasets, and calculating metrics like mean absolute error between device outputs. |

Energy Pathway and System Constraints Diagram

Wearable Energy Constraints Pathway

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section addresses common technical challenges in research involving continuous physiological monitoring, focusing on the critical balance between data reliability and power constraints.

FAQ 1: Why does my sensor's data become unreliable during long-term ambulatory studies, and how can I improve it?

- Answer: Data reliability in real-world settings is challenged by environmental factors and device power management. Key strategies include:

- Aggregate Data Streams: Combine multiple sensor readings into a compound score. Research shows a compound physiological score can achieve an acceptable test-retest reliability (r = .60), outperforming individual measures like heart rate (r = .53) or skin conductance level (r = .53) [29].

- Implement Adaptive Sampling: Use power management techniques that dynamically adjust the sensor's sampling rate based on user activity. This reduces power consumption during stationary periods without sacrificing data quality during critical movement [21].

- Plan for Calibration: Calibrate sensors in the specific microenvironment where they will be deployed. Performance can vary significantly between different settings (e.g., a classroom versus a lunchroom), and field calibration using machine learning can drastically improve accuracy [30].

FAQ 2: My wearable sensor drains its battery too quickly for long-term studies. What are the solutions?

- Answer: Rapid battery drain is a major bottleneck caused by continuous sensing and data transmission [31].

- Employ On-Device Processing (Edge Intelligence): Transmit only extracted features or compressed data instead of raw, high-frequency signal streams. One proof-of-concept showed this approach reduced Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) transmission energy by approximately 2 Joules per day [31].

- Utilize Collaborative Inference: Offload complex computational tasks, like running deep learning models for motion artifact detection, from the wearable device to a connected smartphone. This strategy can reduce the wearable's energy consumption for these tasks by over two times [31].

- Adopt Adaptive Power Management: Move beyond static power settings. Frameworks using Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) can personalize power management in real-time, considering user context and behavior to extend battery life by over 36% while maintaining user satisfaction [31].

FAQ 3: How do I choose a sensor with the right specifications for a low-power, high-reliability study?

- Answer: Focus on specifications that directly impact the reliability-power trade-off.

- Sampling Rate: Higher sampling rates (e.g., 100-200 Hz) are needed for complex metrics like Heart Rate Variability (HRV) but consume significantly more power. Determine the minimum viable rate for your research question [31].

- Calibration: Ensure the sensor has robust calibration procedures, both pre-deployment and in the field, to maintain data reliability against a reference standard [32].

- Connectivity: Prefer devices with Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) and efficient data protocols to minimize the power cost of transmission [21].

- Sensor Technology: Understand the inherent strengths of the sensing technology. For example, an electrocardiogram (ECG)-based wearable showed more clinically acceptable limits of agreement for heart rate than photoplethysmography (PPG)-based sensors in a clinical validation study [33].

FAQ 4: My sensor is producing erratic readings or no data at all. What are the first steps to diagnose the problem?

- Answer: Before assuming a hardware failure, perform these basic checks [34] [35]:

- Inspect Cables & Electrodes: Check for visible damage, cracks, or creases in patient cables and leads. Ensure electrodes are within their shelf life and the conductive gel has not dried out [35].

- Verify Power: Confirm the device is properly plugged in or charged. Implement a periodic battery charging schedule [34].

- Check Sensor Placement: Improper placement is a common cause of poor signal. Re-seat sensors according to the manufacturer's instructions and ensure proper skin contact [34].

- Clean the Device: Dust and debris on sensors can interfere with readings. Clean and sterilize the device regularly [34].

- Reboot and Update: A simple restart can resolve software glitches. Ensure the device's firmware and software are up to date [34].

Quantitative Data on Sensor Performance & Power

The tables below summarize key quantitative findings from recent studies, essential for designing experiments and evaluating sensor technologies.

Table 1: Sensor Validity and Reliability in a Clinical Setting (Postanesthesia Care Unit) [33]

This table shows the correlation of two wearable sensors against reference clinical monitors.

| Vital Sign | Sensor Name & Technology | Correlation Coefficient (Validity) | Clinical Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate (HR) | VitalPatch (ECG-based) | 0.57 to 0.85 | Moderate to strong correlation. Limits of Agreement (LoA) were clinically acceptable [33]. |

| Radius PPG (PPG-based) | 0.60 to 0.83 | Moderate to strong correlation [33]. | |

| Respiration Rate (RR) | VitalPatch (ECG-based) | 0.08 to 0.16 | Weak correlation [33]. |

| Radius PPG (PPG-based) | 0.20 to 0.12 | Weak correlation [33]. | |

| Blood Oxygenation (SpO2) | Radius PPG (PPG-based) | 0.57 to 0.61 | Moderate correlation [33]. |

Table 2: Impact of Sampling Rate on Power Consumption [31]

This table illustrates the direct trade-off between data fidelity and power demand in a wearable device.

| Sampling Rate | Daily Indoor Light Exposure Needed for Self-Sustainability | Data Fidelity Suitability |

|---|---|---|

| 50 Hz | 1.45 hours | Basic Heart Rate (HR) estimation [31]. |

| 200 Hz | 4.74 hours | Accurate Pulse Rate Variability (PRV) and Heart Rate Variability (HRV) [31]. |

Table 3: Test-Retest Reliability of Ambulatory Physiological Measures [29]

This table presents the reliability of various measures recorded from healthy participants navigating an urban environment on two separate days.

| Physiological Measure | Test-Retest Reliability (r) |

|---|---|

| Compound Score (PC#1) | 0.60 |

| Skin Conductance Response Amplitude | 0.60 |

| Heart Rate | 0.53 |

| Skin Conductance Level | 0.53 |

| Heart Rate Variability | 0.50 |

| Number of Skin Conductance Responses | 0.28 |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Validating Wearable Sensors Against a Clinical Reference Standard

- Objective: To assess the concurrent validity and reliability of a wearable sensor for specific vital signs in a target patient population [33].

- Methodology:

- Design: Prospective observational study with simultaneous data recording from the wearable sensor and a clinical-grade reference monitor (e.g., Philips IntelliVue) [33].

- Participants: Recruit patients from the relevant clinical cohort (e.g., post-surgery) [33].

- Data Collection: Apply the wearable sensor according to the manufacturer's instructions upon admission to the monitoring unit. Ensure time synchronization between all devices [33].

- Data Processing: Remove the first minute of measurements to allow for stabilization. Pair data points from the wearable and reference monitor using nearest-neighbor interpolation with a minimal time shift [33].

- Data Analysis:

- Validity: Calculate repeated-measures correlation coefficients for each vital sign. Interpret as: <0.5 (weak), 0.5-0.7 (moderate), >0.7 (strong) [33].

- Reliability: Perform Bland-Altman analysis adjusted for repeated measurements to determine the mean difference and 95% Limits of Agreement (LoA) [33].

Protocol 2: Assessing Test-Retest Reliability in Ambulatory Naturalistic Settings

- Objective: To determine the reliability of physiological measures obtained via wearable sensors in real-world environments [29].

- Methodology:

- Design: A within-subjects test-retest study where participants complete the same protocol on two separate days.

- Task: Participants navigate a predefined urban walking route while physiological data (e.g., cardiovascular and electrodermal activity) and location are continuously recorded [29].

- Data Aggregation: Calculate aggregate scores for the physiological measures, for example, using Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The first principal component (PC#1) often accounts for a significant portion of the variance and can yield higher reliability than single measures [29].

- Data Analysis: Compute bootstrapped test-retest reliability (correlation coefficient) for both individual physiological measures and the aggregate scores to compare their consistency across testing days [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Essential Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for Sensor Reliability Research

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Reference-Grade Monitor (e.g., Philips IntelliVue) | Serves as the "gold standard" for validating the accuracy and reliability of the wearable sensor data in a clinical or lab setting [33]. |

| CE Class IIa Certified Wearable Sensors (e.g., VitalPatch, Masimo Radius PPG) | The devices under investigation. Using medically certified devices ensures a baseline level of performance and safety for human subjects [33]. |

| Data Synchronization Tool | Critical for aligning data streams from multiple devices. This can be software that uses the institution's network-synchronized computer time to timestamp all data points [33]. |

| Machine Learning Calibration Framework | Software and algorithms (e.g., boosting regression models) for performing field calibration of low-cost sensors, significantly improving their data reliability against a reference [30]. |

| Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) Enabled Smartphone/Tablet | Acts as a data hub for receiving transmissions from the wearable and, in collaborative inference models, as a processing unit for computationally intensive tasks [31]. |

Diagrams: Workflows & Logical Relationships

Sensor Data Reliability Optimization Pathway

Reliability vs. Availability in System Design

Intelligent Solutions: Leveraging Machine Learning and Strategic Design for Enhanced Accuracy

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common sources of sensor inaccuracy that ML can correct? Machine learning effectively addresses several common sensor issues. Sensor drift is a gradual, systematic deviation from the calibrated baseline over time due to aging, material degradation, or environmental changes [36]. Non-linear responses occur when the relationship between the sensor signal and the target analyte concentration is not linear, often leading to signal saturation at higher concentrations [37]. Furthermore, ML can mitigate complex interferences in samples, such as signal overlap from substances with similar redox potentials, and improve accuracy in low-concentration scenarios where the signal-to-noise ratio is poor [37].

Q2: I have limited data from my experiment. Can ML still be effective for sensor calibration? Yes, strategies exist for low-data scenarios. Leveraging sensor redundancy is a powerful approach; using multiple homogeneous sensors and employing data fusion techniques can compensate for the shortcomings of individual units, effectively enhancing the overall data quality [38]. Furthermore, transfer learning frameworks allow you to leverage knowledge from high-data domains. For instance, an Incremental Domain-Adversarial Network (IDAN) can adapt a model trained on a large, source dataset to perform well on your smaller, target dataset, even in the presence of severe drift [36].

Q3: How do I choose between different ML models for my sensor calibration task? The choice depends on the nature of your sensor problem and data. The table below summarizes suitable models for specific tasks.

| Sensor Issue | Recommended ML Models | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| General Non-linear Drift & Complex Interferences | Automated Machine Learning (AutoML), Random Forest, Support Vector Machines (SVM) [39] [37] [36] | Automates model selection; handles complex, non-linear relationships between sensor signals and reference measurements. |

| Temporal Drift & Sequential Data | Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Networks, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN), Incremental Domain-Adversarial Network (IDAN) [36] [40] | Captures time-dependent patterns and long-term dependencies in sensor data for forecasting and continuous adaptation. |

| High-Dimensional Data from Sensor Arrays | Deep Autoencoder Neural Networks (DAEN), Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [41] [36] | Reduces data dimensionality, extracting essential features while removing non-essential noise. |

Q4: What is a "Self-X" architecture and how does it relate to sensor reliability? A Self-X architecture refers to a system endowed with self-calibrating, self-adapting, and self-healing capabilities, inspired by autonomous computing principles [38]. For sensors, this means the system can dynamically adjust calibration parameters in real-time to counteract drift, noise, and even hardware faults, ensuring reliable measurements with minimal manual intervention. This is often achieved by combining sensor redundancy with machine learning algorithms for continuous performance optimization [38].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Gradual Sensor Drift Over Time

Error Message: "Measurement values show a consistent upward or downward trend over weeks/months, despite unchanged calibration standards."

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Protocol:

- Establish Baseline: Collect a benchmark dataset using a reference-grade instrument or known standards alongside your sensor array during initial deployment [39].

- Monitor Temporal Performance: Segment your sensor data into chronological batches (e.g., by month) to track performance metrics like Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE) over time [36].

- Implement a Drift Compensation Framework: Apply a two-stage ML strategy:

- Real-Time Correction: Use an algorithm like Iterative Random Forest to identify and correct abnormal sensor responses as data comes in [36].

- Long-Term Adaptation: Employ a domain adaptation model like an Incremental Domain-Adversarial Network (IDAN). The IDAN treats different time periods as different "domains" and learns to extract features that are invariant across them, effectively compensating for the temporal drift [36].

Experimental Workflow: ML-Driven Drift Compensation

Problem 2: Non-Linear Sensor Response at High or Low Concentrations

Error Message: "Sensor output plateaus at high analyte concentrations" or "Poor signal-to-noise ratio at low concentrations."

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Protocol:

- Characterize Response Curve: Systematically measure sensor responses across the entire expected concentration range, including very low and high values. This will map the linear and non-linear regions [37].

- Develop a Multi-Range Calibration Model: Do not rely on a single linear model. Implement an Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) framework to automatically select and train separate calibration models for different concentration ranges (e.g., one for low/clean levels and another for high/pollution events) [39].

- Enhance Low-Concentration Sensitivity: For trace-level detection, use ML to optimize sensor design parameters or to process the signal in a way that maximizes the signal-to-noise ratio. For example, ML can be used to guide the fabrication of nanozymes for highly sensitive detection [37].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Reference-Grade Instrument | Provides ground truth data for training and validating ML calibration models [39]. |

| Metal-Oxide Semiconductor (MOS) Sensor Array | A common platform for generating multi-dimensional data for drift studies; provides redundancy [36]. |

| Controlled Gas/Vapor Delivery System | Generates precise concentrations of analytes for characterizing non-linear response and low-concentration accuracy [36]. |

| Tunnel Magnetoresistance (TMR) Sensors | A platform for demonstrating Self-X principles and fault injection for robust benchmarking [38]. |

Problem 3: Signal Cross-Talk in Multi-Analyte Environments

Error Message: "Unpredictable sensor readings when multiple chemicals are present; unable to distinguish target analyte."

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Protocol:

- Profile Interferents: Identify all potential interfering substances that may be present in your sample matrix and could generate a similar electrochemical signal [37].

- Generate a Comprehensive Training Set: Create a dataset where the sensor is exposed to the target analyte at various concentrations, both alone and in mixture with various interferents.

- Train a Multi-Output Classification/Regression Model: Use a machine learning model capable of multi-task learning, such as a multi-branch LSTM network or a random forest. The model learns the unique "electrochemical fingerprint" of each substance, allowing it to deconvolute the combined signal and quantify individual analytes despite cross-interference [37] [36].

Experimental Workflow: Multi-Analyte Signal Deconvolution

The following table summarizes quantitative improvements achieved by ML-based calibration methods as reported in recent studies.

| ML Method / Strategy | Sensor Type / Context | Key Performance Improvement |

|---|---|---|

| AutoML Calibration Framework [39] | Indoor PM2.5 Sensors | Achieved R² > 0.90 with reference; RMSE and MAE roughly halved. |

| Multi-Sensor Redundancy & Dimensionality Reduction [38] | TMR Angular Sensors | Reduced Mean Absolute Error (MAE) by over 80% (from ~5.6° to as low as 0.111°). |

| Incremental Domain-Adversarial Network (IDAN) [36] | Metal-Oxide Gas Sensor Array | Achieved robust and good classification accuracy despite severe long-term drift. |

| ML for Low-Concentration Detection [37] | Electrochemical Pb²+ Sensor | Enhanced sensitivity, enabling simple, rapid detection of trace heavy metals. |

Overcoming Ultralow Concentration Challenges with AI-Optimized Sensor Design

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) at Ultralow Concentrations

Problem: Sensor outputs are noisy and unreliable, making it difficult to distinguish the true signal from background interference when detecting targets at parts-per-billion (ppb) or parts-per-trillion (ppt) levels [42].

Solutions:

- Hardware Optimization: Integrate low-noise amplifiers and use shielded circuitry to minimize electrical interference [42].

- Signal Processing: Apply digital signal processing techniques, such as time-based averaging or filtering, to extract meaningful signals from noisy data [42].

- Sensor Redundancy: Employ redundant sensing systems to confirm the presence of real signals across multiple sensors, reducing false positives [42].

- AI-Enhanced Denoising: Use machine learning models, trained on known signal patterns, to intelligently filter noise and enhance signal clarity.

Guide 2: Correcting for Cross-Sensitivity and Interference

Problem: The sensor responds to non-target molecules, leading to inaccurate readings and false positives in complex chemical environments [42] [43].

Solutions:

- Material Design: Utilize chemically selective coatings or membranes on the sensor surface. For instance, functionalizing SnO2 nanonetworks with Au and Pd nanocatalysts can enhance selectivity for specific target gases [43].

- AI-Driven Pattern Recognition: Deploy sensor arrays and use deep learning algorithms (e.g., Residual Networks) to analyze the complex response patterns and uniquely identify the target analyte amidst interferents. This approach has achieved over 99.5% classification accuracy for multiple target gases [43].

- Multi-Sensor Data Fusion: Combine inputs from different types of sensors and use AI models to correlate the data, improving overall selectivity.

Guide 3: Managing Data Scarcity for AI Model Training

Problem: It is challenging to acquire large, labeled datasets for training machine learning models, which is a common scenario in novel ultralow-level detection research [43].

Solutions:

- Data Augmentation: Use techniques like SpecAugment and dynamic time warping (DTW)-based upsampling to artificially expand the size and diversity of your training dataset [43].

- Transfer Learning: Start with a pre-trained model from a related domain and fine-tune it with your smaller, specific dataset.

- Synthetic Data Generation: Generate realistic synthetic data using simulations or generative models to supplement real experimental data.

- Stable Sensor Platforms: Invest in highly reliable sensor platforms with minimal coefficient of variation (CV). A low CV (e.g., below 5%) ensures dataset reproducibility and makes data augmentation more effective [43].

Guide 4: Ensuring Sensor Stability and Reproducibility

Problem: Sensor performance drifts over time or varies between fabrication batches, leading to inconsistent and unreliable data [42] [43].

Solutions:

- Controlled Fabrication: Employ precise fabrication methods like glancing angle deposition (GLAD) to create highly uniform sensor nanostructures [43].

- Systematic Aging: Implement a controlled aging process to stabilize the sensor's surface dynamics and adsorption-desorption equilibria before deployment [43].

- Environmental Control: Calibrate and operate sensors in environments with stable temperature and humidity, or use real-time compensation algorithms to correct for environmental drift [42].

- Regular Calibration: Use NIST-traceable standards and dynamic dilution systems to maintain calibration accuracy at ultralow concentrations [42].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the key performance metrics for AI-optimized sensors at ultralow concentrations?

The table below summarizes key quantitative benchmarks for AI-optimized electrochemical aptasensors, demonstrating significant improvements over conventional sensors [44].

| Performance Metric | Conventional Aptasensors | AI-Optimized Aptasensors |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 60 - 75% | 85 - 95% |

| Specificity | 70 - 80% | 90 - 98% |

| False Positive/Negative Rate | 15 - 20% | 5 - 10% |

| Response Time | 10 - 15 seconds | 2 - 3 seconds |

| Data Processing Speed | 10 - 20 minutes per sample | 2 - 5 minutes per sample |

| Calibration Accuracy | 5 - 10% margin of error | < 2% margin of error |

FAQ 2: How can I validate that my AI model's predictions accurately reflect real-world performance?

Validation should follow rigorous engineering practices [45]:

- Holdout Validation: Reserve a portion of your historical experimental data to test the model's predictions against known outcomes.

- Cross-Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation to ensure the model's robustness and reliability [43].

- Explainability: Use AI platforms with built-in explainability features to understand why the model made a particular prediction, which builds trust and helps identify potential flaws [45].

- Physical Verification: Ultimately, use targeted physical tests to confirm critical AI-generated predictions, maintaining physical testing as the final reference [45].

FAQ 3: What is the impact of AI on reducing physical testing requirements?

Case studies from industry show that AI can significantly reduce development time and costs. For example, Nissan's use of the Monolith AI platform to predict test outcomes has already led to a 17% reduction in physical bolt-joint testing. The company anticipates this approach could halve development test time for future vehicle models by prioritizing only the most informative tests [45].

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for data reliability in AI-driven sensor research?

Maintaining high data reliability is essential for training effective AI models [46].

- Track Key Metrics: Monitor metrics like duplicate rate, error rate, stability index, and schema adherence rate.

- Implement Data Validation: Use automated checks to validate data for errors and inconsistencies before it is processed or stored.

- Conduct Regular Audits: Perform completeness audits and stability assessments to proactively identify and resolve data drift or gaps.

- Establish Data Governance: Create clear policies and standards for data management to ensure consistency and accountability.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Highly Uniform SnO2 Herringbone-like Nanocolumns (HBNCs) for Reliable Sensing

This protocol outlines the methodology for creating a stable sensor platform with a coefficient of variation (CV) below 5%, which is foundational for generating high-quality datasets for AI [43].

Methodology:

- Substrate Preparation: Use a substrate with interdigitated electrodes (IDEs). Align the substrate so the long fingers of the IDEs are parallel to the intended deposition direction.

- Glancing Angle Deposition (GLAD): Place the substrate in an e-beam evaporator. Use the GLAD method to deposit sequential layers of SnO2, controlling the substrate rotation, deposition angle, and temperature to form the herringbone-like nanocolumn structure.

- Catalyst Functionalization: Decorate the SnO2 HBNCs with catalytic metal nanoparticles (e.g., Au or Pd) by depositing thin metal films (e.g., 1 nm thick) onto the nanostructures followed by thermal annealing to form nanoparticles.

- Systematic Aging: Subject the fabricated sensors to a controlled aging process to stabilize their surface dynamics and ensure reproducible performance before use in experiments.

Protocol 2: AI Model Training for Gas Classification Using Sensor Array Data

This protocol describes the process for training a deep learning model to classify gases based on data from a reliable sensor array [43].

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Expose the fabricated sensor array to various target gases (e.g., acetone, hydrogen, ethanol, carbon monoxide) at different concentrations and under varying humidity conditions. Record the sensor response signals.

- Data Augmentation: Augment the collected dataset to increase its size and variability. Apply techniques such as:

- SpecAugment: A spectrogram-based augmentation method.

- Dynamic Time Warping (DTW)-based Upsampling: Warps the time series to generate new, realistic signal variations.

- Model Selection and Training: Implement a deep learning model, such as a Residual Network (ResNet), for classification. Train the model on the augmented dataset.

- Model Validation: Validate the model's performance using k-fold cross-validation. Assess the classification accuracy on unseen test data to confirm that it generalizes well, with goals of achieving over 99.5% accuracy [43].

Research Workflow and Signaling Pathways

AI-Optimized Sensor Research Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for developing and optimizing sensors for ultralow-concentration detection.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| SnO2 Herringbone-like Nanocolumns (HBNCs) | The primary metal oxide semiconductor sensing material. Its high surface area and tunable porosity enhance gas diffusion and reaction kinetics [43]. |

| Gold (Au) & Palladium (Pd) Nanocatalysts | Functionalization agents that decorate the SnO2 surface. They enhance selectivity and sensitivity toward specific target gases by modifying surface reactions [43]. |

| Interdigitated Electrodes (IDEs) | A microelectrode system used to measure changes in the electrical properties (e.g., resistance) of the sensing material upon exposure to analytes [43]. |

| NIST-Traceable Calibration Standards | Certified reference materials used to calibrate sensors accurately at parts-per-billion (ppb) and parts-per-trillion (ppt) levels, ensuring measurement traceability [42]. |

| Electrochemical Redox Probes (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) | Molecules used in electrochemical aptasensors that produce a measurable change in current or impedance when the aptamer binds to its target, enabling detection [44]. |

| Dynamic Dilution Systems | Instrumentation that generates precise, ultralow concentration gas mixtures from higher-concentration sources for sensor calibration and testing [42]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My wireless sensor network for environmental monitoring has up to 50% missing data due to power and network failures. Which imputation method should I use to save my dataset?

A1: For datasets with high missingness (e.g., 30-50%), especially from sensor failures, methods that leverage spatial correlation or combine spatial and temporal information are most robust [47]. Matrix Completion (MC) techniques have been shown to outperform others in large-scale environmental sensor networks with high missing data proportions [47]. For a quick, initial solution, a Random Forest-based method (MissForest) can also be effective, as it generally performs well across various datasets [47].

Q2: I suspect the missing data in my clinical trial is "informative"—patients dropping out due to side effects. How can I test this and what is a robust analytical strategy?

A2: Your suspicion points to data that may be Missing Not at Random (MNAR). To assess this, you can use logistic regression models to check if the odds of study discontinuation are associated with observed baseline characteristics or treatment groups [48]. For a robust analysis, do not rely solely on a primary method that assumes data is Missing at Random (MAR). Instead, perform sensitivity analyses using multiple imputation methods that incorporate a hazard ratio parameter (θ) to model different post-discontinuation risks. This allows you to see if your trial's conclusions hold under various plausible MNAR scenarios [48].

Q3: After using Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE), how do I know if my imputations are plausible?

A3: You should never treat imputed data as real without diagnostics. Use graphical tools to compare the distribution of observed versus imputed data [49]. Key functions in R (if using the mice package) include:

densityplot(): To overlay kernel density plots of observed and imputed data. The distributions should be similar [49].stripplot(): To see the distribution of individual data points for smaller datasets [49].bwplot(): To create side-by-side boxplots for larger datasets [49]. Significant discrepancies between the red (imputed) and blue (observed) distributions suggest a potential problem with your imputation model or that the data may be MNAR [49].

Q4: For predictive modeling in drug discovery, is it acceptable to use simple imputation methods like mean imputation?

A4: While imputation can be more useful in prediction than in inference, simple methods like mean imputation are still not recommended [50] [51]. Mean imputation distorts the variable's distribution, creates an artificial spike at the mean, biases the standard error, and weakens correlations with other variables [51]. For predictive modeling, more sophisticated methods like MissForest or MICE are preferred as they preserve the relationships between variables and result in better model performance [47] [50].

Q5: My final chart needs to show imputed vs. observed data, but my colleague is colour blind. What are the best practices for colour in data visualisation?

A5: Effective colour use is critical for accessibility. Adhere to the following guidelines [52]:

- Do Not Rely on Colour Alone: Use different point shapes or line types in addition to colour to distinguish between groups (e.g., imputed vs. observed) [52].

- Check Contrast Ratios: Ensure a minimum contrast ratio of 3:1 for graphical elements and 4.5:1 for text against the background. Use online tools like the WebAIM Colour Contrast Checker [52].

- Test in Greyscale: Preview your charts in black and white to ensure the information is still comprehensible without colour [52].

- Use Accessible Palettes: For sequential data, use a single-hue palette with varying lightness. For categorical data (like imputed vs. observed), use colours that are distinguishable to all major forms of colour blindness [53] [52].

Experimental Protocols for Imputation

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Workflow for Evaluating Imputation Methods on Sensor Data

This protocol is adapted from a large-scale study on microclimate sensor data [47].

1. Objective: To empirically evaluate and select the best imputation method for a spatiotemporal sensor dataset with significant missing data. 2. Materials:

- A dataset from a Wireless Sensor Network (WSN), such as the CNidT garden sensor dataset (4,400 sensors, 15-minute intervals) [47].

- Computing environment with R or Python and necessary libraries (e.g.,

micein R,scikit-learnin Python). 3. Procedure: - Step 1: Data Preprocessing. Clean the data and identify a subset of sensors with complete data to serve as a ground truth.

- Step 2: Induce Missingness. Artificially remove data from the complete subset in different patterns and proportions (e.g., 10%, 20%, up to 50%) to simulate random sensor failure. For a more realistic test, use a "masked" scenario that replicates the actual missing data patterns found in your incomplete sensors [47].

- Step 3: Apply Imputation Methods. Run a suite of imputation methods on the dataset with induced missingness. The evaluated methods should include [47]:

- Temporal: Mean Imputation, Spline Interpolation.

- Spatial: k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), MissForest, MICE, MCMC.

- Spatiotemporal: Matrix Completion (MC), M-RNN, BRITS.

- Step 4: Performance Evaluation. Compare the imputed values against the held-out true values using metrics like Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) [47].

- Step 5: Model Selection. Select the method with the lowest error metrics and best performance in the most relevant missingness scenario for your application.

Protocol 2: Sensitivity Analysis for Informative Censoring in Clinical Trials

This protocol is based on methodologies for handling informative dropout in time-to-event data [48].

1. Objective: To assess the robustness of a clinical trial's primary finding to assumptions about missing data. 2. Materials:

- A time-to-event dataset (e.g., time to intervention for a mood episode).

- Statistical software capable of multiple imputation and survival analysis (e.g., R, SAS). 3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Primary Analysis. Conduct your primary time-to-event analysis (e.g., Cox model), censoring patients at their discontinuation time. This assumes non-informative censoring (MAR) [48].

- Step 2: Multiple Imputation for Sensitivity Analysis.

- For patients who discontinued, use multiple imputation to draw their failure times from a conditional survival distribution.

- Incorporate a hazard ratio parameter (θ) that specifies the relative risk of an event after discontinuation compared to staying on the trial. A range of θ values (e.g., from 1.0 to 3.0) should be tested to represent varying degrees of risk post-discontinuation [48].

- Step 3: Analyze and Combine. Analyze each of the multiply imputed datasets using the standard method for right-censored data and combine the results using Rubin's rules [48].

- Step 4: Interpret. Plot the treatment effect estimate (e.g., hazard ratio) against the different θ values. The conclusion of your trial is considered robust if the treatment effect remains significant across a plausible range of θ values [48].

Performance Data and Research Reagents

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Imputation Methods on Wireless Sensor Data [47]

This table summarizes the relative performance of various methods when applied to a large-scale sensor dataset, with "+++" being the best and "+" being the worst.

| Method | Imputation Strategy | Typical Use Case | Performance (RMSE/MAE) for Random Missings | Performance for Realistic "Masked" Missings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matrix Completion (MC) | Spatial & Temporal (Static) | Large-scale networks, high missingness | +++ | +++ |

| MissForest | Spatial Correlations | General-purpose, mixed data types | ++ | ++ |

| MICE | Spatial Correlations | Data with complex relationships | ++ | + |

| M-RNN/BRITS | Deep Learning (Temporal) | Complex time-series patterns | +/++ | +/++ |

| KNN Imputation | Spatial Correlations | Simple, small datasets | + | + |

| Spline Interpolation | Temporal Correlations | Single sensors, low missingness | + | + |

| Mean Imputation | Temporal Correlations | Baseline only; not recommended | + | + |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Resources for Imputation Research

| Item / Resource | Function in Research |

|---|---|

R mice Package |

A core library for performing Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE), including diagnostics and pooling [49] [51]. |

Python scikit-learn |

Provides simple imputers (e.g., SimpleImputer, KNNImputer) and machine learning models that can be leveraged in custom imputation pipelines. |