Beyond the Lab Bench: Revolutionizing Plant Biotechnology with Floral Dip and CRISPR

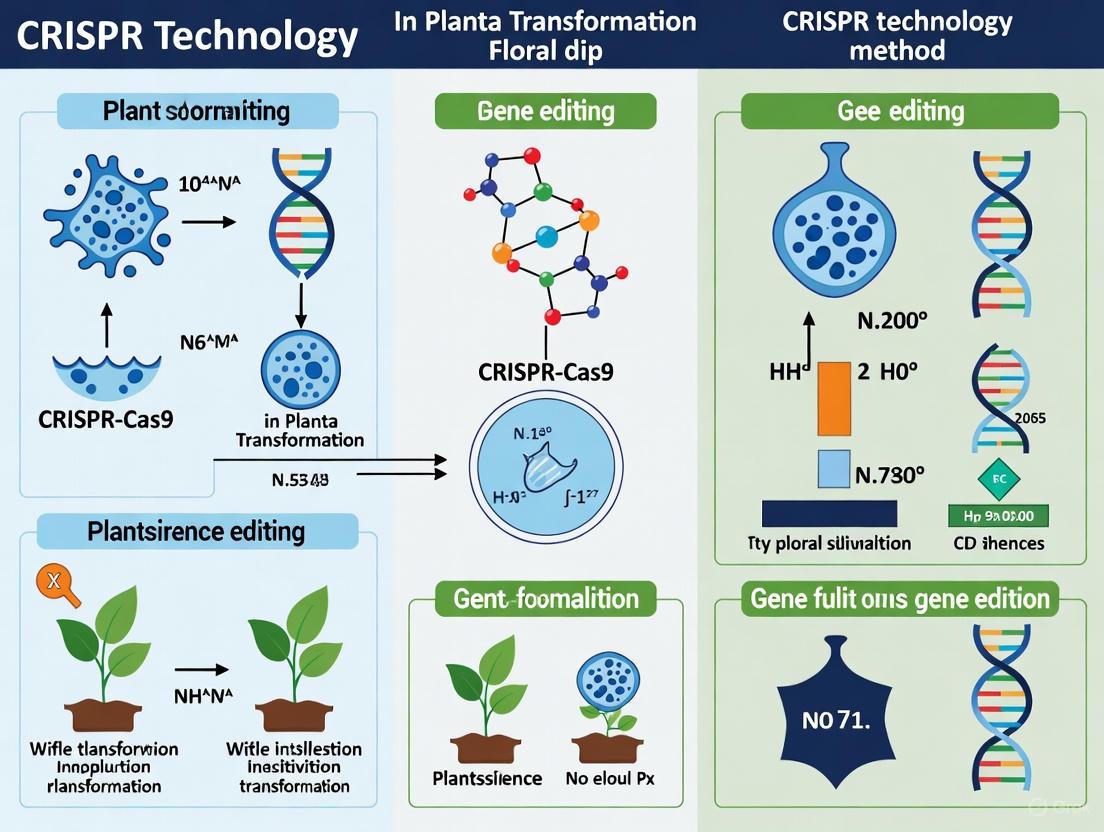

This article explores the powerful synergy between in planta transformation, particularly the floral dip method, and CRISPR-Cas genome editing.

Beyond the Lab Bench: Revolutionizing Plant Biotechnology with Floral Dip and CRISPR

Abstract

This article explores the powerful synergy between in planta transformation, particularly the floral dip method, and CRISPR-Cas genome editing. Tailored for researchers and scientists, it provides a comprehensive overview from foundational principles to cutting-edge applications. We delve into the methodology of tissue-culture-free transformation, address common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and present a comparative analysis of delivery systems. The content synthesizes the latest research to illustrate how these combined technologies are accelerating the development of improved crops and offering new tools for biomedical research, ultimately paving the way for a more efficient and accessible future in plant bioengineering.

Understanding In Planta Transformation: Bypassing the Tissue Culture Bottleneck

In planta transformation represents a paradigm shift in plant genetic engineering, offering a technically simple, genotype-independent alternative to conventional in vitro methods. This approach, particularly through techniques like the floral dip method, is revolutionizing functional genomics and crop breeding by enabling stable genetic modifications without the need for extensive tissue culture. Within the context of modern CRISPR/Cas9 research, in planta strategies facilitate high-throughput genome editing, allowing for the rapid analysis of gene functions and the development of novel traits in a wide range of plant species. This application note details the principles, protocols, and key advantages of in planta transformation, providing researchers with a framework for its implementation in advanced genetic studies.

In planta stable transformation encompasses a heterogeneous group of methods for the direct, stable integration of foreign DNA into a plant's genome and the subsequent regeneration of transformed cells into whole plants without relying on callus culture [1]. The defining feature of these techniques is the execution of genetic transformation with no or minimal tissue culture steps, a stark contrast to conventional methods that depend on in vitro regeneration from single transformed cells [2] [1]. This minimalism makes in planta strategies particularly suited for the era of CRISPR-Cas9 and high-throughput genome editing, as they are often considered genotype-independent, less prone to somaclonal variations, and accessible to laboratories with limited resources [1]. The most celebrated example of this approach is the Arabidopsis thaliana floral dip method, a protocol that has significantly contributed to the establishment of Arabidopsis as a premier model organism in plant biology [1].

A Comparative Analysis: In Planta Versus Conventional Transformation

The core of the paradigm shift lies in the fundamental differences between in planta and conventional in vitro transformation/regeneration techniques. The following table summarizes the key distinctions:

Table 1: A comparative analysis of in planta and conventional transformation methods.

| Feature | In Planta Transformation | Conventional In Vitro Transformation |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Culture Requirement | No or minimal steps [1] | Essential and extensive |

| Technical Simplicity | High; often does not require sterile conditions or complex media [1] | Low; requires strict sterility and specialized media formulations |

| Genotype Dependence | Largely genotype-independent [1] | Highly genotype-dependent; many species and cultivars are recalcitrant |

| Regeneration Pathway | Direct regeneration from differentiated explants (e.g., meristems, gametes) [1] | Indirect regeneration via an intervening callus phase |

| Risk of Somaclonal Variation | Low | High, due to the callus phase |

| Typical Duration | Shorter | Longer, due to multiple in vitro stages |

| Infrastructure & Cost | Lower; affordable and easy to implement [1] | Higher; requires specialized tissue culture facilities |

| Applicability to Minor Crops | High; suited for a wide range of species [1] | Low; often limited to transformable models and major crops |

Beyond the technical simplifications, in planta methods align perfectly with modern genome-editing tools like CRISPR/Cas9. The direct transformation of plant cells within the intact organism can simplify the recovery of edited progeny and, in the case of DNA-free editing using preassembled CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoproteins (RNPs), may help to circumvent GMO regulations since no transgene is integrated [3] [4].

Classifying In Planta Transformation Techniques

In planta methods can be categorized based on the type of explant targeted for transformation. The following workflow illustrates the decision process for selecting and executing a primary in planta method, specifically the floral dip technique for CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing.

Diagram 1: A workflow for in planta transformation and CRISPR genome editing.

This diagram outlines the primary categories of in planta transformation [1]:

- Germline Transformation: Targets the haploid female (ovule) or male (pollen) gametophytic cells before fertilization. The floral dip method is a prime example that transforms the female gametes.

- Zygote/Embryo Transformation: Targets the progenitor stem cell (zygote) formed from the fusion of gametes or the developing embryo.

- Meristem Transformation: Targets the shoot apical meristem (SAM) or adventitious meristems, which are regions of active cell division.

Experimental Protocol: Floral Dip CRISPR/Cas9 Genome Editing

The following is a detailed protocol for implementing the floral dip method to create CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutations in Arabidopsis thaliana, adaptable to other suitable species.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential reagents for floral dip CRISPR/Cas9 transformation.

| Reagent / Material | Function and Specification |

|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 Vector | A binary vector containing a plant codon-optimized Cas9 gene and a sgRNA expression cassette targeting the gene of interest [4]. |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | A disarmed strain (e.g., GV3101) used as a vehicle to deliver the T-DNA containing the CRISPR machinery into plant cells [4]. |

| Infiltration Medium | A solution containing half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) salts, 5% (w/v) sucrose, and 0.01-0.05% (v/v) surfactant (e.g., Silwet L-77) to reduce surface tension [1]. |

| Plant Material | Healthy, well-watered plants with numerous immature floral buds (approximately 2-4 weeks after bolsing for Arabidopsis). |

| Selection Agents | Antibiotics or herbicides for selecting transformed T1 seeds, depending on the selectable marker gene used in the T-DNA (e.g., Kanamycin, Basta/glufosinate). |

Step-by-Step Workflow

- Vector Construction and Agrobacterium Preparation: Clone a sgRNA specific to your target gene into a binary CRISPR/Cas9 vector. Introduce the resulting plasmid into an appropriate Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain. Grow a fresh, single colony of the transformed Agrobacterium in a selective liquid medium (e.g., YEP with appropriate antibiotics) to an optical density at 600 nm (OD₆₀₀) of approximately 0.8 [4].

- Preparation of Dip Solution: Pellet the bacterial culture by centrifugation and resuspend it in the infiltration medium to a final OD₆₀₀ of ~0.8. Add the surfactant (e.g., 0.02-0.05% Silwet L-77) just before use. The solution should be used immediately.

- Plant Transformation (Floral Dip): Submerge the above-ground parts of the plant, focusing on the inflorescences with developing floral buds, into the dip solution for 2-3 minutes. Gently agitate to ensure thorough infiltration [1].

- Post-Transplantation Care and Seed Harvest: Lay the dipped plants on their sides and cover them with transparent plastic wrap or a dome to maintain high humidity for 16-24 hours. Afterwards, return the plants to normal growth conditions. Allow the plants to mature and set seeds. Harvest the seeds from the dipped plants once fully dried; these are the T1 generation seeds.

- Selection and Screening of Transformed Plants: Sow the T1 seeds on soil or selection medium containing the appropriate antibiotic or herbicide. Resistant plants are potential transformants. For CRISPR edits, genomic DNA should be extracted from the resistant T1 plants and the target region PCR-amplified. The PCR products can be analyzed by Sanger sequencing, followed by tracking of indels by decomposition (TIDE) analysis, or by next-generation sequencing to identify mutation events [4].

Case Study: Application of CRISPR/Cas9 in Torenia via In Planta Transformation

A compelling application of this paradigm shift is the modification of flower color in the ornamental plant Torenia fournieri using CRISPR/Cas9. Researchers targeted the flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H) gene, a key enzyme in the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway [4].

- Objective: To create loss-of-function mutations in the F3H gene to alter flower pigmentation from violet to white or pale blue.

- Method: A plant codon-optimized Cas9 and a F3H-specific gRNA were assembled in a binary vector and introduced into Agrobacterium. Standard Agrobacterium-mediated transformation was performed, likely involving tissue culture, which successfully generated transgenic T0 plants [4].

- Results and Efficiency: The system was highly efficient, with approximately 80% of the regenerated transgenic lines (15 out of 24) exhibiting a clear phenotype of faint blue (almost white) flowers. Sequence analysis confirmed the presence of indels (insertions/deletions) in the F3H target sequence of these lines, confirming that the phenotype was a result of targeted mutagenesis [4]. The edited plants were acclimatized and grown in a greenhouse, where the modified flower color remained stable.

Table 3: Quantitative results from the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutation of the F3H gene in Torenia [4].

| Phenotype of T0 Lines | Number of Lines | Mutation Rate | Example Mutations Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| Faint Blue (White) | 15 | ~63% | Single-base insertions, deletions, -32 bp deletion |

| Violet (Wild-Type) | 4 | ~17% | No mutation in target sequence |

| Pale Violet | 3 | ~12.5% | Mixed sequences (WT and +1A alleles) |

| Variegated/Unstable | 1 | ~4% | Not specified |

| Mixed (Violet/Faint Blue) | 1 | ~4% | Not specified |

This case study powerfully demonstrates how in planta transformation, coupled with CRISPR/Cas9, provides a precise and efficient tool for functional genomics and the development of novel traits in floricultural crops, bypassing the limitations of traditional breeding.

The floral dip method stands as one of the most transformative protocols in plant molecular biology, fundamentally reshaping genetic research in the model organism Arabidopsis thaliana and beyond. This innovative Agrobacterium-mediated transformation technique, first systematically described by Clough and Bent (1998), revolutionized plant genetic engineering by eliminating the need for complex tissue culture procedures. By simply dipping developing inflorescences into an Agrobacterium tumefaciens suspension containing a surfactant, researchers could directly generate transgenic seeds through normal plant reproduction processes. The method's exceptional simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and efficiency have propelled Arabidopsis to its status as the premier model organism in plant biology [1] [5]. Within the broader context of in planta transformation—a heterogeneous group of techniques aiming for direct stable integration of foreign DNA into plant genomes without callus culture—the floral dip method remains the most widely recognized and successfully implemented approach [1]. As plant biology enters the era of CRISPR-Cas9 and high-throughput genome editing, the principles underlying floral dip have inspired new simplified transformation strategies that seek to overcome the genotype-dependent limitations that have long hindered progress in many plant species, particularly recalcitrant crops and perennial grasses [6] [7].

Core Mechanism and Workflow of the Floral Dip Method

Biological Principles and Target Tissues

The floral dip method achieves genetic transformation by targeting the female reproductive organs (gynoecium) within developing flowers, particularly the developing ovules [5]. During the dipping process, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, carrying engineered T-DNA vectors, infiltrates the floral tissues through the action of surfactants that reduce surface tension. The primary transformation event occurs in the female gametophyte (egg cell) before fertilization, resulting in transgenic seeds that develop after the dipped flowers self-pollinate [1]. This direct transformation of reproductive cells bypasses the need for somatic cell transformation followed by regeneration, which constitutes the major bottleneck in conventional transformation protocols. The success of this method relies on precise timing—dipping must occur when flowers are at the optimal developmental stage, with immature floral buds but before silique development [8].

Standardized Protocol and Workflow

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages in a standardized floral dip transformation protocol:

The foundational protocol for Arabidopsis thaliana has been optimized through numerous studies. Key improvements include the elimination of the media exchange step—direct dipping into Agrobacterium culture supplemented with surfactant and sucrose is equally effective and significantly less laborious [9]. The standard protocol utilizes Silwet L-77 at concentrations of 0.01-0.05% as a surfactant to ensure proper infiltration of the bacterial suspension into floral tissues [8] [9]. Optimal bacterial density (OD₆₀₀) typically ranges from 0.5 to 1.0, with higher densities potentially causing phytotoxicity [8]. Following dipping, plants are maintained under high humidity conditions for 1-2 days to facilitate recovery and transformation efficiency, then grown to seed maturity under standard conditions.

Optimization Parameters: Quantitative Analysis

Extensive research has identified critical parameters that significantly influence transformation efficiency across plant species. The following table summarizes key optimization variables and their impact on transformation success:

Table 1: Critical Optimization Parameters for Floral Dip Transformation

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Impact on Efficiency | Species-Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Density (OD₆₀₀) | 0.3-0.8 | Higher densities may cause phytotoxicity; lower densities reduce T-DNA delivery [8] | Descurainia sophia: OD₆₀₀=0.6 optimal; OD₆₀₀=1.2 caused wilting and death [8] |

| Surfactant Concentration | 0.01-0.05% Silwet L-77 | Critical for infiltration; excess causes tissue damage [8] [9] | Descurainia sophia: 0.03% optimal; 0.05-0.10% dramatically reduced efficiency [8] |

| Sucrose Concentration | 5-10% | Osmotic support for bacterial survival during inoculation [9] | Standard in Arabidopsis and Brassicaceae family extensions [8] [9] |

| Plant Developmental Stage | Bolting with immature flowers | Determines accessibility to female gametophyte targets [8] | Critical for all species; varies by flowering timeline [8] [7] |

| Acetosyringone | 0-200 μM | Induces vir gene expression; species- and strain-dependent [8] | Descurainia sophia: No addition superior to 100 μM [8] |

Additional significant factors include the Agrobacterium strain selection, plant genotype, and environmental conditions during and post-transformation. The use of alternative growth media such as YEBS without resuspension has been successfully demonstrated, further simplifying the protocol [9]. For selection, chromatography sand saturated with antibiotic-containing media provides a sterile, low-cost alternative to agar-based selection systems [9].

Expansion Beyond Arabidopsis: Applications Across Plant Families

The remarkable success of floral dip in Arabidopsis has motivated extensive efforts to adapt this method to other plant species, particularly within the Brassicaceae family and beyond:

Brassicaceae Family Applications

The floral dip method has been successfully extended to multiple species within the Brassicaceae family, leveraging phylogenetic proximity to Arabidopsis. A recent landmark study established an efficient floral dip protocol for Descurainia sophia (flixweed), a medicinal plant in the Brassicaceae family [8]. Through systematic optimization, researchers achieved transformation efficiencies of approximately 1.5% using an Agrobacterium suspension with OD₆₀₀=0.6 and 0.03% Silwet L-77 without acetosyringone [8]. Furthermore, the method successfully delivered CRISPR-Cas9 components targeting the phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene, producing mutant plants with expected albino phenotypes within 2.5 months, thus validating the system for genome editing applications [8]. The protocol has also been successfully implemented in various Brassica species, including B. rapa, B. napus, and B. carinata [8].

Challenges and Limitations in Non-Brassicaceae Species

Despite these successes, broader application of the floral dip method faces significant biological constraints. Key limiting factors include flower morphology that creates physical barriers to infiltration, necrotic reactions to Agrobacterium that cause flower abortion, low seed set following treatment, and large plant or flower structures that are not amenable to dipping [8]. These limitations are particularly pronounced in monocot species, which lack the floral architecture that makes Arabidopsis and related Brassicaceae species so amenable to this method [7].

Integration with CRISPR Genome Editing

The fusion of floral dip methodology with CRISPR-Cas genome editing represents a powerful combination for functional genomics and precision breeding. The application of this integrated approach in Descurainia sophia demonstrates its potential for rapid validation of gene function in non-model species [8]. Similar approaches are being explored for accelerated domestication of perennial grain crops, where the ability to edit domestication genes without complex tissue culture would overcome major barriers in species with high ploidy and heterozygosity [7].

To enhance the efficiency of precision genome editing via floral dip, research has focused on improving Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) outcomes. Recent chemical screening approaches have identified histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors such as tacedinaline and entinostat as effective enhancers of HDR efficiency in both plant and mammalian systems [10]. These compounds can be incorporated into the floral dip suspension to modify chromatin accessibility and improve the frequency of precise gene integration events.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Floral Dip Transformation

| Reagent/Category | Function and Application | Specific Examples and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium Strains | T-DNA delivery vector system | GV3101, AGL1, EHA105; strain selection affects host range [8] [5] |

| Surfactants | Enable infiltration of bacterial suspension into floral tissues | Silwet L-77 (0.01-0.05%); concentration must be optimized to balance efficiency and phytotoxicity [8] [9] |

| Selectable Markers | Selection of transformed progeny | Antibiotic resistance (hpt, nptII, aadA) or herbicide resistance (BAR) genes [5] [9] |

| Visual Reporters | Rapid screening of transformation events | GUS (β-glucuronidase), GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein), RUBY (visible red pigment) [8] [5] |

| Developmental Regulators | Enhance transformation efficiency in recalcitrant species | WUS, BBM, GRF-GIF fusions; co-expression can overcome genotype limitations [6] |

Future Perspectives and Emerging Methodologies

The future of floral dip methodology lies in overcoming species-specific limitations through innovative approaches. Developmental regulator-assisted transformation represents a particularly promising avenue, where co-expression of transcription factors such as WUSCHEL (WUS), BABY BOOM (BBM), or GRF-GIF fusions can dramatically enhance regeneration capacity and potentially expand the host range of floral dip protocols [6]. The following diagram illustrates how these innovative approaches are expanding the applications of in planta transformation:

For truly recalcitrant species, particularly monocots, related in planta transformation methods that target different tissues offer complementary approaches. These include the RAPID (Regenerative Activity-dependent In planta Injection Delivery) method, which uses injection to deliver Agrobacterium to meristematic tissues in species with strong regeneration capacity like sweet potato and potato [11]. Other innovative approaches include meristem transformation [5], pollen-mediated transformation [1], and virus-mediated delivery of editing components [7]. Each of these methods shares the fundamental principle of floral dip—bypassing tissue culture to achieve direct transformation—while adapting to the biological constraints of different plant families.

As these technologies mature, the floral dip method and its derivatives will play an increasingly vital role in enabling high-throughput functional genomics and precision breeding across diverse plant species, ultimately supporting the development of sustainable agricultural systems through improved crop varieties [6] [7].

In the realm of plant biotechnology, the concept of targeting germline cells to achieve heritable genetic changes is a cornerstone for advancing both basic research and applied crop improvement. Unlike in animal systems, where the germline is established early in development, plants form germline cells from meristematic tissues late in their life cycle. This biological characteristic provides a unique window for genetic intervention. In planta transformation methods, particularly the floral dip technique, strategically exploit this developmental timing to introduce genetic modifications that are stably passed to subsequent generations. This protocol details the application of CRISPR-based genome editing tools via the floral dip method, enabling the precise alteration of plant germlines without the need for extensive tissue culture. The principles outlined here are framed within the broader thesis that in planta transformation represents a streamlined, genotype-independent pathway for introducing heritable edits, thereby accelerating functional genomics and trait development in a wide range of plant species, including recalcitrant crops and emerging perennial systems [12] [7].

Key Principles of Germline Targeting in Plants

The efficiency of heritable genome editing in plants hinges on a clear understanding of and ability to target the germline. The following principles are fundamental:

- Developmental Timing: In plants, the germline is not set aside during embryogenesis. Instead, it differentiates from floral meristematic cells in the developing flower. Successful transformation requires the delivery of editing components to these specific cells just before or during the early stages of gamete formation [12].

- Precision in DNA Repair: The CRISPR/Cas system induces double-strand breaks (DSBs) in the DNA. The resulting heritable edit is determined by the cell's repair mechanism. Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) is predominantly used for gene knockouts, while homology-directed repair (HDR), though less frequent, can enable precise nucleotide changes or gene insertions [13].

- Stable Integration vs. Transient Expression: For a change to be heritable, the edit must be incorporated into the DNA of a germline cell. This can be achieved either through the stable integration of a T-DNA construct into the plant genome via Agrobacterium, or through the transient expression of CRISPR machinery that creates edits in the germline cells before being degraded, resulting in edited but transgene-free progeny [14].

Quantitative Data on Editing Efficiencies

The success of germline targeting is quantitatively measured by editing efficiency, which varies significantly based on the method, plant species, and target tissue. The table below summarizes key efficiency data from relevant studies.

Table 1: Genome Editing Efficiencies Across Plant Transformation Methods

| Species | Delivery Method | Plant Tissue / Strategy | Editing Efficiency (%) | Key Experimental Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pigeonpea [15] | Agrobacterium-mediated | Apical meristem (in planta) | 8.80% | Potato ubiquitin promoter for Cas9; apical meristem targeting |

| Pigeonpea [15] | Agrobacterium-mediated | Embryonic axis (in vitro) | 9.16% | Use of embryonic axis explants with tissue culture |

| Barley [7] | Virus-induced genome editing (VIGE) | Leaf tissues (in planta) | 17% - 35% (T0) | Pre-existing Cas9-expressing line ('Golden Promise'); virus-delivered gRNA |

| Barley [7] | Biolistics (iPB-RNP) | Mature embryos | 1% - 4.2% (T0), 0.3% - 1.6% (T1) | Direct delivery of pre-complexed Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) |

| Rice [7] | Agrobacterium-mediated | Seedlings | 9% (T0) | CRISPR/Cas9 construct with hygromycin selection |

Experimental Protocol: Floral Dip for CRISPR-Based Germline Editing

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for achieving heritable genetic changes in Arabidopsis thaliana using the floral dip technique, adaptable for other amenable species.

Reagents and Equipment

- Plant Material: Healthy Arabidopsis plants grown to the stage of early bolting, with the first few flowers open.

- Biological Material: Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 carrying a binary vector with the CRISPR/Cas9 construct (e.g., Cas9 gene driven by a constitutive promoter like CaMV 35S or Arabidopsis UBI10, and species-specific gRNA expression cassette [12] [7]).

- Media and Solutions:

- LB Broth and LB Agar with appropriate antibiotics (e.g., kanamycin, rifampicin).

- Infiltration Medium: 5% (w/v) sucrose, 1/2x Murashige and Skoog (MS) salts, 0.05% (v/v) Silwet L-77, pH 5.8 [12].

- Equipment: Conical tubes, vacuum infiltration apparatus or desiccator, growth chambers.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Agrobacterium Culture Preparation:

- Inoculate a single colony of the engineered Agrobacterium into 5 mL of LB medium with antibiotics. Grow overnight at 28°C with shaking (220 rpm).

- The next day, use this culture to inoculate a larger volume (200-500 mL) of LB with antibiotics. Grow until the optical density at 600 nm (OD₆₀₀) reaches 0.8 - 1.0 [12].

- Pellet the cells by centrifugation at 5,000 x g for 15 minutes at room temperature.

- Gently resuspend the pellet in the prepared Infiltration Medium to a final OD₆₀₀ of 0.8.

Plant Preparation:

- Carefully remove any already developed siliques from the plants, as these are too mature to be transformed. The goal is to target floral buds that have not yet undergone gametogenesis.

- Gently wound the main inflorescence and floral buds by making small nicks or by gently bending stems to increase Agrobacterium access to the germline precursor cells [12].

Floral Dip Transformation:

- Invert the above-ground part of the plant and submerge the floral tissues completely into the Agrobacterium suspension in a beaker or container.

- For vacuum infiltration: Place the entire container inside a vacuum desiccator. Apply a vacuum of 250-500 mmHg for 5-10 minutes. Slowly release the vacuum to allow the suspension to infiltrate the floral tissues.

- Without vacuum: Simply dip and agitate the plants for 2-5 minutes, ensuring thorough coating.

- Lay the treated plants on their sides and cover them with transparent plastic wrap or a dome to maintain high humidity for 16-24 hours. Then, return the plants to an upright position and grow under standard conditions until seeds mature [12].

Selection and Genotyping of Progeny (T1 Generation):

- Harvest seeds from dipped plants (T0 generation) and surface-sterilize.

- Sow seeds on selective medium (e.g., containing hygromycin or kanamycin) or directly in soil.

- For soil-grown plants, perform PCR genotyping on leaf tissue from 2-3 week old seedlings to identify transgenic T1 plants.

- Sequence the target genomic region in PCR-positive plants to confirm the presence of intended mutations. A diagram of the complete experimental workflow is provided below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of this protocol relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Floral Dip CRISPR

| Item | Function / Rationale | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | The effector protein that creates a double-strand break at the target DNA sequence. | Can be delivered as DNA (within T-DNA), mRNA, or as a pre-complexed Ribonucleoprotein (RNP). RNP delivery can reduce off-target effects [14]. |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | A short RNA sequence that programmably directs Cas9 to the specific genomic locus. | Expressed from a Pol III promoter (e.g., U6 or U3) within the T-DNA. Species-specific promoters (e.g., CcU6_7.1 in pigeonpea) enhance efficiency [15]. |

| Binary Vector | A T-DNA plasmid used in Agrobacterium to transfer the CRISPR components into the plant cell nucleus. | Contains left and right T-DNA borders, a plant selection marker (e.g., hygromycin resistance), and bacterial selection markers [15]. |

| Constitutive Promoter | Drives high-level, continuous expression of the Cas9 nuclease. | Common choices include Cauliflower Mosaic Virus 35S (CaMV 35S) for dicots and maize Ubiquitin 1 (Ubi-1) for monocots. Arabidopsis UBI10 is also highly effective [12]. |

| Silwet L-77 | A surfactant that reduces the surface tension of the infiltration medium, allowing it to coat and penetrate the floral tissues effectively. | Critical for ensuring the Agrobacterium suspension reaches the germline precursor cells. Typically used at 0.05% (v/v) [12]. |

Molecular Mechanisms and Safety Considerations

Understanding the intracellular journey of the CRISPR components and the potential risks is vital for experimental design and interpretation.

From Delivery to Heritable Edit

The following diagram illustrates the molecular pathway from the initial delivery of CRISPR components to the formation of a stable, heritable edit in the plant genome.

Addressing Structural Variations and Genomic Integrity

A critical safety consideration in CRISPR editing is the potential for unintended, large-scale genomic damage beyond small indels. Recent studies reveal that CRISPR/Cas9 can induce structural variations (SVs), including megabase-scale deletions and chromosomal translocations, both at the on-target site and at off-target sites with sequence similarity [13]. These SVs are often missed by standard short-read sequencing but pose significant safety concerns. Strategies to mitigate these risks include:

- Avoiding DNA-PKcs Inhibitors: The use of DNA-PKcs inhibitors to enhance HDR efficiency has been shown to dramatically increase the frequency of these SVs and should be avoided in protocols aiming for clinical translation [13].

- Utilizing High-Fidelity Cas Variants: Engineered Cas9 variants with enhanced specificity can reduce off-target activity [13].

- Comprehensive Genotyping: Employing long-read sequencing or specialized assays (e.g., CAST-Seq, LAM-HTGTS) is recommended to fully assess the genomic integrity of edited lines before further use [13].

The floral dip method represents a powerful and efficient in planta strategy for introducing heritable genetic changes by directly targeting the plant germline. Its success is built upon the precise coordination of plant developmental biology with the molecular action of the CRISPR/Cas9 system. While the protocol is robust for model plants like Arabidopsis, ongoing research into optimizing delivery vectors, tissue-specific promoters, and culture conditions is extending its utility to recalcitrant and perennial crop species [7]. By adhering to the detailed protocols, understanding the quantitative efficiencies, and being mindful of both the molecular mechanisms and potential genomic risks, researchers can reliably employ this technique to advance plant genome engineering and accelerate the development of improved crop varieties.

The discovery of the CRISPR/Cas system has revolutionized plant genomics, serving as a powerful tool for functional gene studies, trait discovery, and accelerated breeding programs across diverse plant species. Over the past decade, this technology has evolved from a basic gene-editing apparatus into a sophisticated toolkit capable of addressing complex agricultural challenges posed by climate change and evolving consumer needs [16]. While highly efficient, the implementation of CRISPR/Cas in plants faces several bottlenecks, including challenges in tissue culture, transformation, regeneration, and mutant detection [16].

This Application Note focuses specifically on validating and implementing CRISPR-Cas technologies within the context of in planta transformation, particularly the floral dip method. This approach bypasses many traditional tissue culture limitations, offering a streamlined pathway for generating transgene-free, gene-edited plants. We provide detailed protocols, optimized parameters, and practical resources to enable researchers to effectively apply these techniques in their plant genome engineering workflows.

Establishing a Floral Dip Transformation System for CRISPR

The floral dip method is a classic Agrobacterium-mediated transformation technique that is simple, convenient, stable, and inexpensive. Originally established in Arabidopsis thaliana, it has been successfully adapted for other Brassicaceae species [8]. The following protocol, optimized for Descurainia sophia, provides a framework that can be adapted for related species.

Protocol: Floral Dip-Mediated Transformation and Genome Editing

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101

- Binary vector carrying CRISPR/Cas9 constructs and desired sgRNAs

- Plant material: Healthy D. sophia plants with developing inflorescences

- Silwet L-77 surfactant

- Acetosyringone (AS) stock solution

- Sucrose

- Hygromycin B (HygB) for selection

- Woody Plant Medium (WPM) or similar growth medium

Experimental Workflow:

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of the floral dip transformation protocol for generating gene-edited plants.

Detailed Procedure:

Plant Growth and Preparation:

- Grow D. sophia plants under controlled conditions (approximately 1.5 months to flowering).

- Use healthy plants with developing inflorescences for transformation.

Vector Construction and Agrobacterium Preparation:

- Clone sgRNAs targeting your gene of interest (e.g., Phytoene Desaturase (PDS) for a visible albino phenotype) into an appropriate CRISPR/Cas9 binary vector.

- Transform the construct into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101.

- Grow the transformed Agrobacterium in liquid culture to an OD₆₀₀ of 0.6.

Floral Dip Transformation:

- Prepare the inoculation solution: Agrobacterium suspension (OD₆₀₀ = 0.6) with 5% sucrose and 0.03% (v/v) Silwet L-77.

- Dip developing inflorescences into the solution for 45 seconds.

- Maintain treated plants in normal growth conditions until seed set.

Selection and Screening:

- Collect seeds from dipped plants.

- Surface-sterilize and plate on selective medium containing Hygromycin B.

- Identify resistant seedlings after approximately two weeks.

Molecular Confirmation and Phenotypic Analysis:

- Confirm transgenic events by GUS staining or GFP fluorescence [8].

- For CRISPR-edited lines, confirm mutations by sequencing the target region.

- Analyze phenotypes (e.g., albino for PDS knockout) in confirmed mutants.

Optimization Parameters for Floral Dip

Critical parameters influencing transformation efficiency were systematically optimized in D. sophia. The table below summarizes the key findings.

Table 1: Optimization of Floral Dip Transformation Parameters in D. sophia

| Parameter | Tested Conditions | Optimal Condition | Effect on Transformation Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium Density (OD₆₀₀) | 0.3, 0.6, 1.2 | 0.6 | High density (OD=1.2) caused flower wilting and death [8]. |

| Surfactant (Silwet L-77) | 0.03%, 0.05%, 0.10% | 0.03% | Higher concentrations (0.05-0.10%) drastically reduced efficiency [8]. |

| Acetosyringone (AS) | 0 μM, 100 μM | 0 μM | Addition of 100 μM AS surprisingly reduced transformation rate [8]. |

| Infection Duration | 45 seconds | 45 seconds | Established as sufficient for effective transformation [8]. |

Alternative Delivery Methods and Validation Platforms

While floral dipping is effective for amenable species, other delivery methods are crucial for a broader range of crops. Protoplast-based systems offer a valuable platform for rapidly validating CRISPR/Cas reagent efficiency before undertaking stable transformation.

Protoplast-Based Validation Protocol

The following diagram outlines a workflow for using protoplasts to validate genome editing constructs, as demonstrated in pea (Pisum sativum L.).

Key Steps and Optimized Parameters for Pea Protoplasts:

- Protoplast Isolation: Use fully expanded leaves from 2-4 week-old plants. Optimize enzyme solution composition (e.g., cellulase R-10, macerozyme R-10, mannitol concentration) and enzymolysis time for high yield and viability [17].

- PEG-Mediated Transfection:

- Use 20 µg of plasmid DNA per transfection.

- Employ 20% PEG as the transfection agent.

- Incubate for 15 minutes.

- This optimized condition achieved a 59 ± 2.64% transfection efficiency in pea [17].

- Validation of Editing: Transfect with a CRISPR construct (e.g., targeting PsPDS). Mutation efficiency can be as high as 97% in transfected protoplasts, confirming gRNA functionality before stable transformation [17].

Expanding the CRISPR Toolkit for Specialized Applications

Beyond standard Cas9, new CRISPR systems are continuously expanding plant engineering capabilities.

Table 2: Advanced CRISPR Systems and Their Applications in Plants

| CRISPR System | Key Feature | Documented Application | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 mutant SpRY | Relaxed PAM requirement [18] | Larch editing at various PAM sites [18] | Increases the number of targetable genomic sites. |

| Compact Cas12i (Cas12i2Max) | Smaller size (~1,000 aa); high efficiency [19] | Up to 68.6% editing efficiency in stable rice lines [19] | Enables easier vector delivery and simultaneous editing/regulation. |

| Multi-Targeted Libraries | Genome-wide sgRNAs targeting multiple gene families [19] | Generation of ~1300 tomato lines with distinct phenotypes [19] | Overcomes functional redundancy for complex trait breeding. |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Delivery | Direct delivery of pre-assembled Cas9-gRNA complexes [19] | Production of transgene-free edited carrot plants [19] | Avoids transgene integration, simplifying regulatory approval. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of CRISPR-Cas protocols relies on a core set of research reagents. The following table details essential materials and their functions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Plant CRISPR-Cas Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens (e.g., GV3101, EHA105) | Stable delivery of T-DNA containing CRISPR constructs into plant cells. | Floral dip transformation of D. sophia [8]; stable transformation of Fraxinus mandshurica [20]. |

| CRISPR Binary Vectors (e.g., pYLCRISPR/Cas9) | Carries expression cassettes for Cas nuclease and sgRNA(s). | Constructed for targeting FmbHLH1 in F. mandshurica [20]. |

| Endogenous Promoters | Drives expression of Cas nuclease and gRNAs; can enhance editing efficiency. | LarPE004 promoter from larch drove highly efficient STU-Cas9 system [18]. |

| Silwet L-77 | Surfactant that reduces surface tension, improving Agrobacterium penetration. | Critical for efficient floral dip of D. sophia at 0.03% (v/v) [8]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Facilitates the delivery of plasmid DNA into protoplasts. | PEG-mediated transfection of pea protoplasts for CRISPR validation [17]. |

| Selection Agents (e.g., Hygromycin B, Kanamycin) | Selects for plant cells that have integrated the T-DNA. | Screening of transgenic D. sophia seedlings on Hygromycin B [8]. |

The CRISPR-Cas toolkit has matured into an indispensable resource for plant genome engineering. The floral dip method provides a straightforward and efficient in planta transformation strategy for amenable species, particularly within the Brassicaceae family. For species that are recalcitrant to stable transformation, protoplast-based systems offer a high-throughput alternative for validating editing reagents. Furthermore, the continuous development of novel Cas enzymes and delivery methods, such as ribonucleoprotein complexes and miniaturized Cas proteins, is steadily overcoming previous limitations. By integrating these optimized protocols and reagents, researchers can effectively leverage CRISPR-Cas technologies to accelerate functional genomics and molecular breeding programs in a wide range of plant species.

Why Combine Floral Dip and CRISPR? Synergies for Accelerated Breeding

The convergence of Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated floral dip transformation and CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing represents a transformative synergy in plant biotechnology. This powerful combination enables researchers to bypass the laborious, species-specific tissue culture bottleneck that has traditionally constrained genetic improvement in many crops. By allowing for the direct introduction of CRISPR components into plant germline cells in planta, the floral dip method facilitates the recovery of non-chimeric, stably edited progeny in a single generation. This Application Note details the experimental protocols, key reagents, and strategic advantages of integrating these technologies to accelerate functional genomics and breeding programs, with a specific focus on applications within the Brassicaceae family and beyond.

Plant genetic engineering and genome editing are indispensable for enhancing agronomically essential traits and ensuring future food security [21]. While CRISPR/Cas9 has revolutionized plant bio-technology by providing unprecedented precision in genetic modification, its application has been largely dependent on efficient plant transformation and regeneration systems [21] [22].

Traditional transformation relies on in vitro tissue culture—a complex process involving the isolation of specialized tissues, growth under defined aseptic conditions, and regeneration of whole plants from transformed cells. This approach presents significant challenges:

- Time-Consuming Processes: Transformation of species like rice or tomato can require 6 to 12 months using established protocols [21].

- Technical Complexity: Requires optimization of multiple factors at each stage and maintained sterile conditions [21].

- Unwanted Genetic Variation: Tissue culture can induce somaclonal variation—unwanted genetic changes that are independent of the intended editing [21].

- Genotype Dependence: Many commercial and minor crops remain recalcitrant to genetic transformation, severely limiting scientific progress for essential crops [1].

In-planta transformation methods, particularly floral dip, have emerged as a promising alternative to overcome these limitations. When combined with CRISPR/Cas9, they offer a streamlined pathway for accelerated crop improvement.

The Synergy: Conceptual Framework and Advantages

The combination of floral dip and CRISPR/Cas9 is revolutionary because it integrates two powerful, complementary technologies.

What is Floral Dip Transformation?

The floral dip method is a classic Agrobacterium-mediated transformation technique first established in Arabidopsis thaliana [23]. It involves dipping developing inflorescences into a solution containing Agrobacterium tumefaciens carrying the desired genetic construct. The bacterium transfers the T-DNA, which contains the CRISPR/Cas9 components, into the ovules' female gametophytic cells. This results in the direct generation of transformed seeds in the treated plants, bypassing tissue culture entirely [1] [8].

This method falls under the broader category of in-planta transformation, defined as "a means of plant genetic transformation with no or minimal tissue culture steps" [1]. These methods are characterized by their short duration, high technical simplicity, minimal hormone requirements, and regeneration that does not undergo callus development [21].

The Powerful Synergy with CRISPR/Cas9

The table below summarizes the key synergistic advantages of combining floral dip with CRISPR/Cas9 for plant breeding:

Table 1: Synergistic Advantages of Combining Floral Dip with CRISPR/Cas9

| Feature | Traditional Transformation + CRISPR | Floral Dip + CRISPR | Synergistic Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Culture | Required | Eliminated | Reduces time, labor, cost, and technical expertise [21] [22] |

| Process Duration | 6-12 months for some species | As little as 2.5-3 months [8] | Dramatically accelerates breeding cycles |

| Somaclonal Variation | High risk | Minimized | Produces genetically cleaner edited lines without tissue culture-induced mutations [21] |

| Technical Skill | High (sterile technique) | Moderate to Low | Accessible to more labs, promoting equitable research development [1] |

| Genotype Dependence | High for many crops | Lower (within amenable families) | Facilitates editing of species recalcitrant to tissue culture [1] |

Experimental Protocol: Floral Dip for CRISPR/Cas9 inDescurainia sophia

The following optimized protocol for the genetic transformation and gene editing of Descurainia sophia (a medicinal plant in the Brassicaceae family) demonstrates the practical application of this combined approach [8].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Floral Dip-Mediated CRISPR Transformation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Exemplar Details |

|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | Vector for delivering T-DNA containing CRISPR constructs into plant cells. | Strain GV3101 is commonly used [8]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Binary Vector | Contains gene editing machinery (e.g., Cas9, sgRNA) and selectable marker. | Vectors with plant-specific promoters and hygromycin resistance are typical [8]. |

| Silwet L-77 (0.03% v/v) | Surfactant that reduces surface tension, enabling Agrobacterium to infiltrate floral tissues. | Critical for efficiency; higher concentrations (0.05-0.10%) can be deleterious [8]. |

| Sucrose (5% w/v) | Osmoticum that may facilitate the transfer of T-DNA. | Component of the infiltration medium [8]. |

| Acetosyringone (AS) | Phenolic compound that induces the vir genes of Agrobacterium, enhancing T-DNA transfer. | Optimization is required; 0 μM was optimal for D. sophia [8]. |

| Hygromycin B (HygB) | Selective antibiotic to screen for transformed T1 seedlings. | Used at 50 mg/L in half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium [8]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for floral dip CRISPR.

1. Plant Growth and Preparation:

- Grow D. sophia plants under standard conditions until the primary inflorescence is ~10-15 cm tall and multiple secondary inflorescences have developed [8].

- Ensure healthy plant status, as vigor significantly impacts transformation success.

2. Agrobacterium Culture Preparation:

- Introduce the CRISPR/Cas9 binary vector (e.g., targeting the Phytoene Desaturase (PDS) gene for a visible albino phenotype) into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101.

- Initiate a culture from a single colony and grow it in appropriate selective liquid medium to the exponential phase (OD₆₀₀ = 0.6). Centrifuge and resuspend the bacterial pellet in the infiltration medium (5% sucrose, 0.03% Silwet L-77) to the optimal density [8].

3. Floral Dip Infiltration:

- Invert the above-ground inflorescences of the plant and submerge them in the Agrobacterium suspension for 45 seconds with gentle agitation [8].

- Lay treated plants on their sides and cover with transparent plastic film or a dome to maintain high humidity for 16-24 hours.

4. Plant Recovery and Seed Harvesting:

- Return plants to normal growth conditions.

- Allow seeds to develop to full maturity on the treated plants. This typically takes approximately two months for D. sophia [8].

- Harvest seeds (T1 generation) from dipped inflorescences and dry them at room temperature for one to two weeks.

5. Selection and Identification of Transformed Plants:

- Surface-sterilize T1 seeds and plate them on half-strength MS medium containing 50 mg/L Hygromycin B (HygB) [8].

- Resistant green seedlings that develop roots are potential transformants, while non-transformed seedlings will be bleached and stunted.

- Transfer resistant seedlings to soil for further growth and analysis.

6. Molecular Confirmation of Genome Editing:

- Extract genomic DNA from putative transformants.

- Use PCR to amplify the targeted genomic region and sequence the products to confirm the presence of CRISPR-induced mutations.

- Tools like Inference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) can be used to analyze the spectrum and efficiency of editing events [8].

Successful Applications and Broader Implementation

Evidence from Model and Crop Plants

The floral dip CRISPR strategy has been successfully validated across multiple species, demonstrating its broad utility.

Table 3: Documented Success of Floral Dip and CRISPR in Various Species

| Plant Species | Family | Target Gene / Trait | Key Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descurainia sophia | Brassicaceae | Phytoene Desaturase (PDS) | Successful knockout, albino phenotype observed in ~2.5 months. | [8] |

| Arabidopsis thaliana | Brassicaceae | Various | The foundational model for the method; used for rapid prototyping of CRISPR systems. | [23] [24] |

| Various Crops | Multiple | N/A | Successfully applied in camelina, cotton, lemon, melon, peanut, rice, soybean, and wheat. | [21] |

Expanding the Toolbox: CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa) via Floral Dip

Beyond gene knockouts, floral dip can deliver more advanced CRISPR tools. CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) employs a deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) fused to transcriptional activators to upregulate endogenous gene expression without altering the DNA sequence—a gain-of-function approach [24].

This is particularly valuable for:

- Studying Gene Redundancy: Where knocking out single genes fails to reveal phenotypes due to compensation by homologous genes [24].

- Enhancing Disease Resistance: For example, upregulating defense-related genes like PATHOGENESIS-RELATED GENE 1 (SlPR-1) in tomato or SlPAL2 to enhance lignin accumulation and defense [24].

- Fine-Tuning Metabolic Pathways: Allowing for quantitative and reversible gene activation in their native genomic context, minimizing pleiotropic effects [24].

The integration of the floral dip method with CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing represents a paradigm shift in plant genetic engineering. This synergy directly addresses one of the most significant bottlenecks in crop improvement—the tissue culture barrier—by offering a simpler, faster, and more accessible pathway to generating edited plants.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this combination accelerates the pipeline from gene discovery to functional validation and trait development. It is particularly powerful for high-throughput functional genomics and for engineering complex traits such as disease resistance and climate resilience. As CRISPR technologies continue to evolve with systems like base editing, prime editing, and CRISPRa, the ability to deliver these tools efficiently via in planta methods like floral dip will be crucial for unlocking the full potential of plant biotechnology and meeting the global challenges of food and nutritional security.

A Practical Guide to Floral Dip CRISPR Workflows and Cutting-Edge Delivery Systems

Standardized Floral Dip Protocol for Arabidopsis and Beyond

The floral dip method is a revolutionary Agrobacterium-mediated transformation technique that has become the cornerstone of modern plant functional genomics. First established in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, this approach has since been successfully adapted to other Brassicaceae species and various dicot plants [8]. Its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and reliability have made it particularly valuable for CRISPR research, enabling rapid analysis of gene function without the bottlenecks of traditional tissue culture-based transformation systems [16] [22].

The fundamental principle underlying floral dip transformation involves utilizing the natural DNA transfer capability of Agrobacterium tumefaciens to introduce foreign genes directly into plant germline cells. Unlike tissue culture methods that require sterile conditions and plant regeneration, floral dip allows for the direct generation of transgenic seeds through a simple dipping procedure, significantly reducing the time and expertise required [25]. This in planta approach has been successfully used to validate CRISPR/Cas constructs, perform targeted mutagenesis, and study gene function in both model and non-model plants [8] [26].

Standardized Floral Dip Protocol for Arabidopsis thaliana

Plant Preparation and Growth Conditions

- Plant Material: Grow healthy Arabidopsis thaliana plants under long-day conditions (16-18 hours light) until flowering initiates (approximately 4-5 weeks after sowing) [27] [25].

- Pre-treatment: Approximately 4-6 days before transformation, clip the primary inflorescence to encourage proliferation of multiple secondary bolts, which increases the number of floral buds available for transformation [27].

- Optimal Stage: Plants are ready for transformation when they have numerous immature flower clusters and minimal fertilized siliques. Remove mature siliques prior to transformation to reduce the number of non-transformed seeds [25].

Agrobacterium Culture Preparation

- Strain Selection: Use Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 or other suitable strains carrying the binary vector with your gene of interest and selection marker [8] [27].

- Culture Growth:

- Culture Harvest: Spin down the Agrobacterium culture by centrifugation and resuspend to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.8 in infiltration medium [27].

Infiltration Medium Preparation

Prepare the infiltration medium containing 5% sucrose [27]. Immediately before use, add the surfactant Silwet L-77 to a final concentration of 0.05% (500 μL/L) and mix thoroughly [27]. Note that some protocols recommend lower concentrations (0.02-0.03%) if toxicity concerns arise [8] [27].

Floral Dip Transformation

- Dipping Procedure: Invert above-ground parts of plants and submerge for 2-3 seconds in the Agrobacterium suspension with gentle agitation [27]. The solution should form a thin film coating the plant surfaces.

- Post-treatment: Place dipped plants under a dome or cover for 16-24 hours to maintain high humidity, protecting them from excessive sunlight during recovery [27].

- Multiple Dipping: For higher transformation efficiency, perform a second dip 5-7 days after the initial treatment [25] [28].

Post-transformation Care and Seed Harvest

- Plant Recovery: Grow plants normally after transformation, supporting loose bolts with stakes or ties [27].

- Seed Collection: Reduce watering as seeds mature. Harvest dry seeds approximately 4-6 weeks after transformation [27] [25].

Selection of Transformants

- Sterilization: Surface-sterilize harvested seeds using vapor-phase or liquid sterilization methods [27].

- Plating: Plate seeds on appropriate selection medium (e.g., 0.5X MS/0.8% tissue culture agar plates) containing the relevant antibiotic (50 μg/mL kanamycin) or herbicide [27].

- Selection Conditions: Cold-treat plated seeds for 2 days, then grow under continuous light (50-100 μE) for 7-10 days [27].

- Transplanting: Transfer resistant seedlings to soil for further growth and analysis [27].

Optimization and Troubleshooting

Critical Parameters for Success

Table 1: Key Parameters for Successful Floral Dip Transformation

| Parameter | Optimal Condition | Effect on Transformation | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Health | Vigorous growth, no stress signs | Healthy plants produce more seeds, increasing transformation chances | [25] |

| Developmental Stage | Many immature flowers, few siliques | Maximizes access to female gametophytes | [27] [25] |

| Agrobacterium Density | OD600 = 0.8 | Sufficient bacteria for infection without plant damage | [27] |

| Surfactant Concentration | 0.03-0.05% Silwet L-77 | Enhances infiltration without phytotoxicity | [8] [27] |

| Sucrose Concentration | 5% | Osmotic support for Agrobacterium | [27] |

| Multiple Dipping | 2 times, 5-7 days apart | Increases transformation efficiency | [25] [28] |

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- Low Transformation Efficiency: Ensure plant vitality, use logarithmic-phase Agrobacterium cultures, optimize surfactant concentration, and implement multiple dipping events [25].

- Plant Damage After Dipping: Reduce Silwet L-77 concentration (0.02% or as low as 0.005%) or lower Agrobacterium density [27].

- High Background During Selection: Avoid plating seeds too densely and do not leave plants on selective plates for extended periods [25].

- Contamination Issues: For alternative selection methods, consider using chromatography sand instead of sterile plates to reduce contamination risks [29].

Adaptation to Other Plant Species

Floral Dip in Descurainia sophia

Recent research has successfully adapted the floral dip method to Descurainia sophia, a medicinal plant in the Brassicaceae family [8]. Key optimized parameters include:

Table 2: Optimized Floral Dip Parameters for Descurainia sophia

| Parameter | Optimal Condition | Transformation Efficiency | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium Density | OD600 = 0.6 | 1.521% | Higher density (OD600 = 1.2) caused wilting | [8] |

| Acetosyringone | 0 μM | 1.521% | 100 μM reduced efficiency to 0.143% | [8] |

| Silwet L-77 | 0.03% | 1.521% | Higher concentrations reduced efficiency | [8] |

| Dipping Duration | 45 seconds | Successful transformation | Shorter than Arabidopsis | [8] |

The successful establishment of floral dip in D. sophia demonstrates the potential for adapting this method to other non-model species within the Brassicaceae family and beyond [8].

Considerations for Species Adaptation

When adapting floral dip to new species, several factors require optimization:

- Developmental Timing: Identify the optimal flowering stage when gametophytes are accessible but not yet fertilized [8].

- Surfactant Tolerance: Determine species-specific tolerance to Silwet L-77 to balance infiltration efficiency with plant health [8].

- Agrobacterium Strain Selection: Test different Agrobacterium strains for compatibility with the target species [25].

- Selection System: Establish efficient selection protocols using antibiotics or herbicides appropriate for the species [8].

Application in CRISPR Research

Floral Dip for CRISPR/Cas Delivery

The floral dip method has been successfully employed to deliver CRISPR/Cas components for targeted genome editing [8] [26]. Recent advances include:

- Temperature-Tolerant Cas12a Variants: Engineering of ttLbCas12a with dramatically improved editing efficiency at plant growth temperatures (22°C), showing 2-7 fold higher efficiency compared to wild-type LbCas12a [26].

- Direct Mutagenesis: Successful knockout of the phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene in D. sophia resulting in albino phenotypes within 2.5 months [8].

- Multiplex Editing: Co-transformation with multiple Agrobacterium strains harboring different gRNAs to target several genes simultaneously [29].

Experimental Workflow for CRISPR Editing

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for CRISPR genome editing using the floral dip method:

CRISPR System Components for Plant Genome Editing

Table 3: Essential CRISPR Components for Floral Dip Transformation

| Component | Function | Examples | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas Nuclease | DNA cleavage at target sites | SpCas9, LbCas12a, ttLbCas12a | [26] |

| Guide RNA | Targets nuclease to specific genomic loci | Single guide RNA, crRNA | [26] |

| Promoter | Drives expression in plant cells | Ubi4-2, Arabidopsis U6-26 | [26] |

| Selection Marker | Identifies transformed plants | Hygromycin B, Kanamycin, Basta | [8] [25] |

| Temperature-Tolerant Variants | Enhanced editing at growth temperatures | ttLbCas12a (D156R mutation) | [26] |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents required for successful floral dip transformation:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Floral Dip Transformation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium Strain GV3101 | T-DNA delivery | Preferred for Arabidopsis and Brassicaceae | [8] [27] |

| Binary Vectors | Carries gene of interest | Gateway, Golden Gate systems available | [25] |

| Silwet L-77 | Surfactant | Critical for infiltration; concentration varies by species | [8] [27] |

| Sucrose | Osmoticum | Standard 5% in infiltration medium | [27] |

| Selection Agents | Transformant identification | Antibiotics (kanamycin) or herbicides (Basta) | [8] [25] |

| CRISPR Systems | Genome editing | Cas9, temperature-tolerant Cas12a variants | [26] |

| Acetosyringone | vir gene inducer | Species-dependent requirement | [8] |

The standardized floral dip protocol has revolutionized plant genetic engineering by providing a simple, efficient, and cost-effective transformation method. Its integration with CRISPR technology has further accelerated functional genomics and crop improvement programs. Future developments will likely focus on:

- Expanding Species Range: Continued adaptation to non-model plants, particularly economically important crops [22].

- Tissue Culture-Free Editing: Developing completely tissue culture-free approaches for a wider range of species [22].

- Enhanced CRISPR Systems: Implementing novel CRISPR platforms with improved efficiency and temperature stability [26] [16].

- Automation and High-Throughput: Scaling floral dip methods for high-throughput functional genomics applications.

The floral dip method remains an indispensable tool for plant researchers, combining simplicity with robust performance for both conventional transformation and advanced genome editing applications.

The floral dip method is a well-established, tissue culture-free technique for plant transformation, primarily used in the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. This in planta approach involves infiltrating developing flowers with Agrobacterium tumefaciens to directly generate transformed seeds, bypassing the slow, genotype-dependent tissue culture stage that is a major bottleneck for many crop species [22]. However, a significant limitation of conventional floral dip is its primary use for delivering transgenic DNA that integrates randomly into the plant genome.

The emergence of miniature CRISPR systems and advanced viral vectors is now poised to overcome this constraint. These novel delivery vehicles enable the direct introduction of genome editing reagents into plants via floral dip, facilitating transgene-free editing and germline inheritance of edits. This technical advance is critical for applying in planta transformation to a wider range of species and for accelerating trait improvement in crops [30] [31].

Miniature CRISPR Systems: Enabling Viral Vector Delivery

The large size of the commonly used CRISPR-Cas9 system presents a fundamental challenge for its delivery via viral vectors, which have strict cargo capacity limitations. The discovery and engineering of ultra-compact RNA-guided endonucleases, such as TnpB, provide a solution [31].

TnpB enzymes are ancestral to Cas enzymes and are exceptionally small (approximately 400 amino acids), yet they retain programmable RNA-guided nuclease activity. Their compact size allows them to be packaged into viral vectors that were previously unsuitable for delivering full CRISPR systems. These systems use a programmable RNA guide, called an omega RNA (ωRNA), to direct the nuclease to a specific DNA target site [31].

Table 1: Comparison of Miniature RNA-Guided Nucleases for Plant Genome Editing

| Nuclease | Size (aa) | Origin | PAM Requirement | Editing Efficiency in Plants | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISYmu1 TnpB | ~400 | Transposon | Not specified in detail | 0.1% - 4.2% (Arabidopsis protoplasts) [31] | Highest average activity in dicots; enabled germline editing via TRV. |

| ISDra2 TnpB | ~400 | Transposon | Not specified in detail | 0% - 4.8% (Arabidopsis protoplasts) [31] | Active in plant cells; lower average efficiency than ISYmu1. |

| ISAam1 TnpB | ~400 | Transposon | Not specified in detail | 0% - 0.3% (Arabidopsis protoplasts) [31] | Minimal editing activity in Arabidopsis. |

Viral Vectors as Delivery Vehicles for In Planta Editing

Plant viruses, which naturally infect and spread systemically within a host, represent ideal delivery vectors for genome editing reagents. Tobacco Rattle Virus (TRV), a bipartite RNA virus, has been successfully engineered to carry the compact ISYmu1 TnpB system [31].

Protocol: TRV-Mediated Delivery of TnpB for Germline Editing

This protocol describes the process for achieving heritable genome edits in Arabidopsis thaliana using a viral vector, without the need for tissue culture.

I. Vector Construction

- Engineer the TRV2 Vector: Clone the gene encoding the ISYmu1 TnpB protein and its cognate omega RNA (ωRNA) guide sequence into the TRV2 plasmid under the control of the pea early browning virus (pPEBV) promoter.

- Design the Expression Cassette: Configure the TnpB and ωRNA as a single transcript. Include a hepatitis delta virus (HDV) ribozyme sequence immediately downstream of the guide region to ensure proper processing and enhanced activity.

- Incorporate a tRNA: Include a tRNAIleu sequence downstream of the HDV ribozyme. This element promotes systemic movement of the virus within the plant and is critical for the transmission of edited alleles to the next generation [31].

II. Plant Material Preparation

- Select Plant Genotype: Use wild-type (WT) Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Col-0. For potentially higher editing efficiencies, consider using mutants with impaired gene silencing (e.g., rdr6) or DNA repair pathways (e.g., ku70).

- Growth Conditions: Grow plants under standard conditions (22°C, long-day photoperiod) until the primary inflorescence is developed and bolting.

III. Agroflood Inoculation

- Prepare Agrobacterium Culture: Transform A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 with both the engineered TRV2 plasmid and the necessary TRV1 plasmid. Grow cultures to an optimal density (OD600 = 0.6-0.8).

- Induce Virulence: Resuspend the bacterial pellet in an infiltration medium (e.g., containing 5% sucrose and 0.03% Silwet L-77). Acetosyringone may be omitted, as it was shown to reduce transformation efficiency in some floral dip optimizations [8].

- Inoculate Plants: Use the agroflood method. Submerge the above-ground parts of the plant, focusing on the inflorescence, for approximately 45 seconds [8] [31].

- Post-Inoculation Care: Cover plants with a dome or transparent lid to maintain high humidity for 16-24 hours. Return plants to standard growth conditions.

IV. Phenotypic Screening and Seed Harvest

- Screen for Somatic Editing: At approximately 3 weeks post-inoculation, screen leaves for the appearance of white speckles or sectors, which indicate biallelic mutations if a visual marker gene like PHYTOENE DESATURASE (PDS) is targeted.

- Harvest T1 Seeds: Allow the treated plants to set seeds. Harvest seeds from inoculated plants individually or in pools.

V. Genotypic Analysis of Progeny

- Germinate T1 Seeds: Sow the harvested T1 seeds on soil.

- Identify Edited Lines: Extract DNA from leaf tissue of T1 seedlings. Use PCR amplification followed by next-generation amplicon sequencing (amp-seq) to detect and quantify mutation frequencies and characterize the repair profiles (typically deletion-dominant) in the subsequent generation (T2) [31].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key experimental steps from vector preparation to the analysis of edited plants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Viral Vector-Mediated In Planta Editing

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Role in the Protocol | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TnpB-ωRNA Expression Vector | Engineered viral vector (TRV2) carrying the compact nuclease and its guide RNA. | Plasmid with pPEBV promoter driving a single transcript of ISYmu1 TnpB-ωRNA [31]. |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens Strain | Bacterial vehicle for delivering the viral vector plasmids into plant cells. | Strain GV3101; optimized for plant transformation [8] [31]. |

| Infiltration Medium | Aqueous solution for suspending bacteria and facilitating plant infiltration. | Contains 5% sucrose and surfactant Silwet L-77 (0.03-0.05% v/v) [8] [31]. |

| Silwet L-77 Surfactant | Reduces surface tension, allowing the suspension to coat and penetrate plant tissues effectively. | Critical for efficiency. Concentration must be optimized; excess can be deleterious [8]. |

| tRNAIleu Sequence | A genetic element incorporated into the viral vector to enhance systemic movement and germline transmission. | Enables edits to reach reproductive tissues and be passed to the next generation [31]. |

| HDV Ribozyme | Self-cleaving RNA sequence that ensures proper processing of the ωRNA guide from the primary transcript. | Significantly boosts TnpB editing activity in planta [31]. |

The combination of miniature CRISPR systems like TnpB with engineered viral vectors represents a transformative advancement for in planta genome editing. This integrated methodology successfully addresses the dual challenges of delivery and transgene removal, core limitations of traditional plant transformation.

The experimental protocols and reagents outlined here provide a roadmap for researchers to implement this technology. By leveraging the natural infection cycle of viruses and the compact nature of TnpB, it is now feasible to achieve heritable, transgene-free mutations in a single generation through simplified methods like agroflood inoculation. This paves the way for rapid functional gene validation and trait development in a wider array of crop species, moving beyond the constraints of tissue culture and accelerating crop improvement programs. Future efforts will focus on expanding the host range of viral vectors and discovering or engineering even more efficient and specific miniature nucleases.

The floral dip method, a cornerstone of plant molecular biology, was instrumental in establishing Arabidopsis thaliana as a premier model organism [1]. This revolutionary in planta technique, which involves the simple dipping of flowering plants into an Agrobacterium tumefaciens solution, eliminated the need for complex and time-consuming tissue culture procedures [1]. However, a significant bottleneck persisted in plant science: the recalcitrance of most commercial and minor crops to genetic transformation, which severely limited the application of advanced breeding techniques in a wide range of species essential for global food security [1].

The advent of CRISPR-Cas genome editing has brought the potential of in planta transformation back to the forefront. CRISPR provides the precision for targeted genetic modifications, while in planta strategies offer a genotype-independent, technically simple, and affordable route for stable transformation, devoid of or with minimal tissue culture steps [1]. This powerful synergy is now overcoming historical limitations, enabling researchers to expand the host range of transformable species, from major staples like potato and sweet potato to non-model organisms previously intractable to genetic engineering [11] [32]. This Application Note details the latest success stories and provides detailed protocols for implementing these cutting-edge techniques.

Success Stories in Diverse Species

Recent advances have demonstrated that the combination of CRISPR and in planta methods is not a theoretical ideal but a practical reality with validated successes across diverse plant types.

Key Advances in Crops and Non-Model Species

The following table summarizes breakthrough applications of in planta transformation and CRISPR editing in a variety of species, highlighting the key genetic targets and achieved outcomes.

Table 1: Success Stories of In Planta Transformation and CRISPR in Various Species

| Species | Transformation/Editing Method | Gene(s) Targeted/Edited | Key Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sweet Potato, Potato, Bayhops | RAPID (Reconstructive-Activity–Dependent In Planta Injection Delivery) | Not Specified (Proof-of-Concept) | Stable transgenic plants obtained via vegetative propagation; higher efficiency and shorter duration than traditional methods. [11] | |

| Citrus | In Planta Genome Editing System (IPGEC) | CsPDS | High-efficiency, transgene-free, biallelic editing in soil-grown seedlings of commercial cultivars, avoiding tissue culture. [33] | |

| Tomato | Virus-Induced Genome Editing (VIGE) | Not Specified | Heritable genome editing achieved with up to 100% efficiency in progeny using a tissue culture-free method. [33] | |

| Barley & Soybean | CRISPR-Cas9 | Protease inhibitor genes (CI-1A etc.) | Enhanced protein digestibility in edited lines, improving nutritional quality for food and feed. [33] | |

| Parhyale (Crustacean) | CRISPR-Cas9 | Multiple developmental genes | Repeated years of siRNA knockdown phenotypes in just six months, accelerating functional genomics in a non-model organism. [32] | |

| Nematostella vectensis (Sea Anemone) | CRISPR-Cas9 | Genes for stinging cell (cnidocyte) development | Enabled the mapping of gene regulatory networks underlying the evolution of novel cell types. [32] | |

| Diverse Non-Model Animals | CRISPR-Cas9 | Various developmental genes | Revolutionized comparative developmental biology studies at the Marine Biological Laboratory embryology course. [32] |

Analysis of Success Factors

The success stories in Table 1 share several common factors that were critical to overcoming species-specific barriers:

- Bypassing Tissue Culture: Methods like RAPID [11] and IPGEC [33] directly target meristematic cells or seedlings in soil, avoiding the slow and genotype-dependent callus regeneration phase. This is particularly vital for perennial crops and elite cultivars that are often recalcitrant to in vitro regeneration [22].

- Leveraging Regeneration Capacity: The RAPID method explicitly exploits the plant's innate active regeneration capability, using injected meristems to generate nascent tissues that are then vegetatively propagated to create stable transgenic plants [11].

- Innovative Delivery Systems: The use of engineered viruses (e.g., Tobacco Rattle Virus for TnpB delivery [33]) and optimized Agrobacterium strains (e.g., K599 and C58C1 for Salvia miltiorrhiza [33]) has been crucial for achieving efficient editing in new hosts.

- Tool Compactness and Efficiency: The development of smaller Cas effectors (e.g., CasMINI) and high-fidelity variants helps overcome delivery constraints and reduces off-target effects in genetically complex species [34].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed, actionable protocol for a novel in planta transformation method and general guidelines for adapting CRISPR tools to non-model species.

Protocol: RAPID Method for Sweet Potato, Potato, and Bayhops

The following workflow diagram outlines the key stages of the RAPID protocol, from plant preparation to the generation of confirmed transgenic plants.

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for the RAPID Protocol

| Item | Function/Description | Notes/Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | Transformation vector delivery. | Strain selection should be optimized for the host species. |

| Binary Vector with Transgene | Contains gene of interest and selection markers. | For CRISPR, contains Cas9 and sgRNA expression cassettes. |

| Infiltration Medium | Liquid medium for Agrobacterium suspension. | Typically contains acetosyringone to induce Vir genes. |

| Syringe with Needle | For physical delivery into meristem tissues. | Needle gauge (e.g., 1-mL syringe) is critical for success. |

| Plant Growth Facilities | Controlled environment for plant growth and recovery. | |

| Selection Agents (Optional) | Antibiotics or herbicides to identify transformants. | May not be required if relying on phenotypic screening. |