Beyond the Lab: A Practical Framework for Validating Plant Sensor Accuracy in Precision Agriculture

This article provides researchers and agricultural scientists with a comprehensive framework for validating the accuracy of plant and soil sensors against traditional laboratory methods.

Beyond the Lab: A Practical Framework for Validating Plant Sensor Accuracy in Precision Agriculture

Abstract

This article provides researchers and agricultural scientists with a comprehensive framework for validating the accuracy of plant and soil sensors against traditional laboratory methods. It covers the foundational principles of sensor technologies, outlines rigorous methodological approaches for side-by-side testing, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and presents a structured validation protocol for comparative analysis. The content synthesizes current research and practical case studies to guide professionals in establishing reliable, data-driven protocols for integrating sensor technology into precision agriculture and research, ensuring data integrity and actionable insights.

Understanding the Sensor and Lab Landscape: Core Principles and Technologies

The adoption of plant sensors and precision agriculture technologies has created a paradigm shift in crop management, moving farming from intuition-based decisions to data-driven agriculture. However, the reliability of these decisions hinges entirely on one critical factor: the demonstrated accuracy and validation of sensor data against established reference methods. In both research and commercial applications, understanding the performance characteristics, limitations, and appropriate validation methodologies for these technologies is fundamental to their effective deployment. This guide provides a structured comparison of sensor technologies and the experimental frameworks needed to validate their measurements against traditional laboratory analyses, providing researchers with practical protocols for verifying sensor accuracy across multiple agricultural applications.

Sensor Technology Comparison: Performance Characteristics and Validation Data

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Agricultural Sensors

The following table summarizes key performance data and validation findings for several plant and soil sensor technologies, based on recent experimental studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of Agricultural Sensor Technologies

| Sensor Technology | Measured Parameters | Reported Accuracy/Performance | Validation Method | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Stress Detection Sensors [1] | Acoustic emissions, stem diameter, stomatal pore area, stomatal conductance | Clear indicators within 24 hours of drought stress at 50% water content of control; sap flow, PSII quantum yield, top leaf temperature showed no early signs [1] | Comparison with controlled irrigation conditions and plant physiological status [1] | Performance varies significantly by parameter measured; some expected indicators did not respond in early stress phases [1] |

| Color-Changing Proline Sensors [2] | Proline concentration (stress biomarker) | Qualitative color change (yellow to bright red) with quantitative potential via scanning; indicates water, heat, or soil metal stress [2] | Laboratory comparison of color intensity with proline concentrations extracted from plant tissue [2] | Destructive testing requiring leaf sample removal and ethanol extraction; qualitative without additional equipment [2] |

| Canopy Reflectance Sensors [3] | Crop nitrogen status | Sensor-based sidedress reduced N application by 33 lb/acre vs. grower practice while maintaining yields [3] | N reference strips in fields; yield mapping at harvest [3] | Requires calibration and correct growth stage timing (V8-V12 for corn) [3] |

| Soil Moisture Sensors [4] | Volumetric Water Content (VWC), Soil Water Potential (SWP) | Research-grade accuracy with proper installation; insensitive to salts, temperature, and soil texture when calibrated [4] | Gravimetric soil sampling and laboratory analysis [4] | Accuracy dependent on proper installation, soil contact, and calibration; potential drift over time [4] |

| Satellite-Based Sensors [3] | Canopy reflectance for N status | Average N savings of 56 lb/acre with yields nearly identical to grower practice [3] | Comparison with ground-truthed sensor data and yield results [3] | Dependent on weather conditions (cloud cover) and has a spatial resolution coarser than some proximal sensors [3] |

Sensor Technology Adoption and Performance Trends

Beyond individual sensor performance, broader adoption trends highlight the growing role of validated sensing systems in agriculture. By 2025, over 80% of large farms are expected to adopt advanced data analytics for crop management, creating a substantial reliance on sensor-derived data [5]. The integration of these technologies is driving significant efficiency gains, with farmers utilizing sensors for irrigation optimization reducing water use by up to 30% while simultaneously improving crop yields [6]. For nitrogen management specifically, precision sensor approaches have demonstrated the ability to reduce application rates by an average of 33-56 pounds per acre while maintaining yields and increasing profitability [3]. These trends underscore why rigorous validation is increasingly critical as agricultural decisions become more automated and data-driven.

Experimental Design for Sensor Validation

Core Validation Methodology Framework

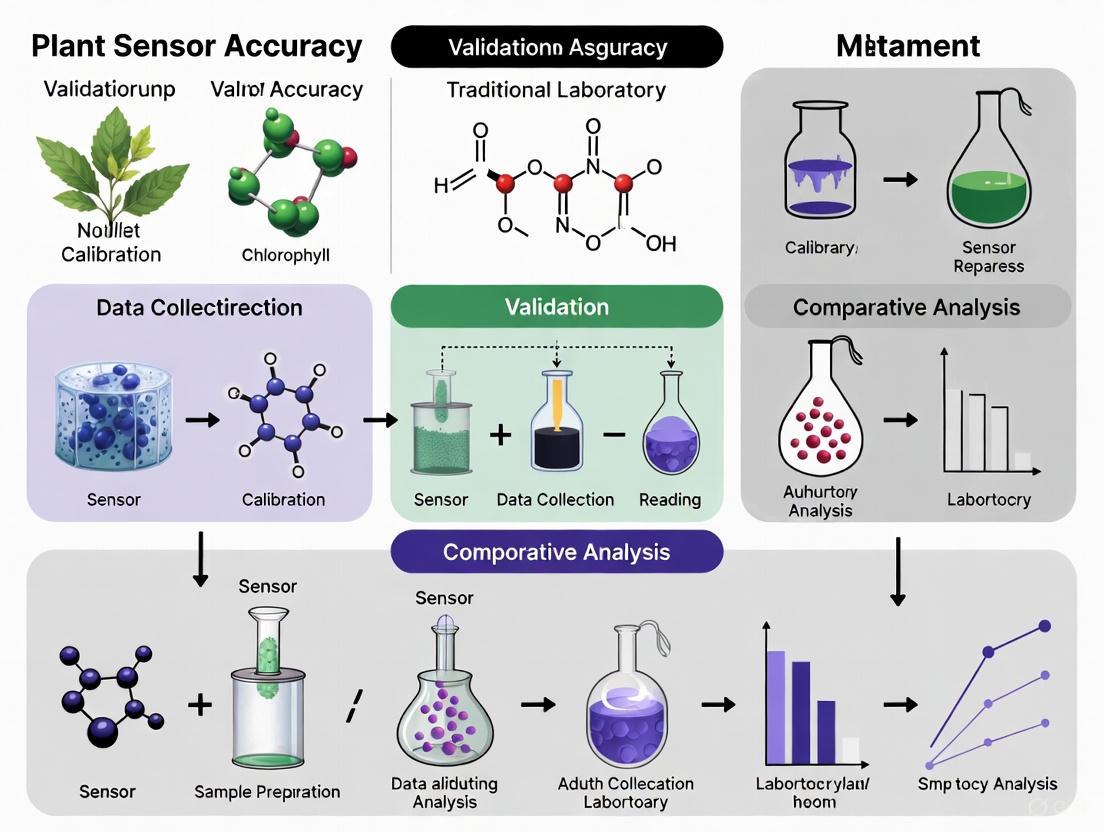

Validating sensor accuracy requires a structured experimental approach that compares sensor readings with established laboratory reference methods under controlled conditions. The workflow below outlines the key stages in this validation process.

Detailed Validation Protocols for Key Sensor Categories

Protocol 1: Validation of Plant Stress Sensors Against Physiological Benchmarks

This protocol validates sensors measuring early drought stress, using the methodology from the greenhouse tomato study [1].

- Experimental Setup: mature, high-wire tomato plants grown in rockwool; control group (full irrigation) vs. treatment group (water withheld for 2 days); water content in slabs monitored and maintained at 50% of control for stress induction [1].

- Test Sensors: acoustic emission sensors, stem diameter variation sensors, stomatal pore area imagers, stomatal conductance meters, sap flow sensors, PSII quantum yield meters, leaf temperature sensors [1].

- Reference Methods:

- Stomatal Conductance: laboratory porometry on destructively sampled leaves.

- Plant Water Status: pressure chamber measurements of leaf water potential.

- Visual Stress Symptoms: standardized photographic documentation of wilting.

- Data Collection: sensor measurements recorded continuously; reference measurements taken at 4-8 hour intervals over 2-5 day stress period [1].

- Validation Metrics: time from stress initiation to significant sensor response; correlation coefficient between sensor readings and reference measurements; determination of detection thresholds.

Protocol 2: Validation of Soil Moisture Sensors

This protocol validates soil moisture sensor accuracy against the gravimetric reference method, following commercial greenhouse guidance [4].

- Experimental Setup: multiple sensor types (volumetric water content and soil water potential) installed at representative locations avoiding edge effects; sensors installed at root zone depth with good soil contact to prevent air pockets [4].

- Reference Method:

- Gravimetric Sampling: soil cores collected adjacent to sensors (within 15cm depth).

- Laboratory Processing: samples weighed, oven-dried at 105°C for 24-48 hours, reweighed.

- Calculation: gravimetric water content converted to volumetric using bulk density.

- Data Collection: simultaneous sensor readings and soil sampling across moisture gradient (irrigation cycle); minimum of 20 paired samples per sensor type [4].

- Validation Metrics: root mean square error (RMSE); mean absolute error (MAE); coefficient of determination (R²); sensor sensitivity to temperature and soil texture.

Protocol 3: Validation of Nitrogen Status Sensors

This protocol validates canopy reflectance sensors for nitrogen management in corn, based on university extension research [3].

- Experimental Setup: corn field with established nitrogen response strips (high N reference strips); multiple sensor systems tested simultaneously (active canopy sensors, satellite-based sensors) [3].

- Reference Methods:

- Plant Tissue Analysis: leaf sampling at same growth stage (V8-V12) for laboratory nitrogen concentration analysis.

- Yield Mapping: harvest data correlated with sensor readings to determine yield impact.

- Data Collection: sensor readings taken at V8-V12 growth stages; tissue samples collected simultaneously from same locations; yield data at harvest [3].

- Validation Metrics: sufficiency index calculated relative to high N reference; correlation between early-season sensor readings and final yield; economic optimization of N application.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Sensor Validation

Key Research Reagent Solutions and Laboratory Equipment

Table 2: Essential Materials for Sensor Validation Studies

| Item | Function in Validation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Analytical Instruments (HPLC, Spectrophotometer) | Quantifies actual analyte concentrations (proline, nutrients) for comparison with sensor outputs [2] [7] | Biochemical stress marker validation; nutrient sensing |

| Portable Field Lab Kits (soil cores, sampling tools, preservatives) | Collects and preserves samples for subsequent laboratory reference analysis [4] [7] | Soil moisture validation; field-based sensor studies |

| Calibration Standards & Buffers (pH standards, conductivity standards) | Provides known reference points for sensor calibration verification [4] [7] | All sensor validation protocols |

| Environmental Control Systems (growth chambers, irrigation controls) | Maintains precise experimental conditions for controlled stress induction [1] | Drought stress studies; nutrient stress validation |

| Data Logging Systems (multichannel loggers, time-sync software) | Ensures temporal alignment between sensor readings and reference measurements [1] [4] | All validation protocols requiring time-series data |

Technology Integration and Relationship Mapping

Modern agricultural sensing operates within a complex ecosystem where multiple technologies interact to provide comprehensive monitoring capabilities. The following diagram illustrates the relationships between different sensor types, their measured parameters, and the corresponding validation methodologies.

As precision agriculture technologies continue to evolve, the critical need for rigorous validation against traditional methods remains constant. The experimental frameworks presented here provide researchers with structured approaches to verify sensor accuracy across multiple agricultural applications. From drought stress detection to nutrient management, establishing demonstrated performance characteristics through controlled experiments and statistical comparison is fundamental to building confidence in these technologies. As sensor systems become increasingly integrated into automated decision-support systems, this validation foundation will grow even more crucial, ensuring that data-driven agriculture delivers on its promise of improved efficiency, productivity, and sustainability.

The transition from traditional laboratory methods to modern sensor technologies represents a paradigm shift in agricultural and environmental research. Where researchers once relied on destructive, time-consuming gravimetric analysis or lab-based chemical assays, they now have access to a suite of in-situ, real-time monitoring tools. This guide establishes a comprehensive taxonomy of these modern sensing platforms, framing them within the critical context of validation against established laboratory methodologies. We objectively compare the performance, operational parameters, and experimental applications of dielectric moisture probes and spectral analyzers—two foundational categories in the researcher's toolkit—to provide scientists with the evidence needed to select appropriate technologies for their specific validation research.

Sensor Taxonomy and Fundamental Operating Principles

A Hierarchical Classification of Sensing Technologies

Modern plant and soil sensors can be classified based on their measurement target, operating principle, and form factor. The taxonomy below categorizes the primary sensor types relevant to scientific research, emphasizing their relationship to traditional measurement techniques.

Core Measurement Principles

Dielectric Sensing Theory

Dielectric sensors operate by measuring the soil's dielectric permittivity, a property that describes how a material polarizes in response to an electric field [8] [9]. Since water has a exceptionally high dielectric constant (≈80) compared to soil solids (≈3-5) and air (≈1), changes in soil water content directly affect the overall dielectric permittivity measured by the sensor [8] [9]. This physical relationship provides the foundation for volumetric water content (VWC) estimation.

Dielectric sensors are primarily categorized into three types:

- Time Domain Reflectometry (TDR): Measures the travel time of an electromagnetic wave along a waveguide embedded in the soil [10] [9]. The wave's velocity depends on the soil's dielectric permittivity.

- Frequency Domain Reflectometry (FDR) / Capacitance: Measures the resonant frequency of an oscillating circuit that uses the soil as its dielectric medium [10] [9]. The resonant frequency shifts with changes in permittivity.

- Fringe Field Capacitance: Utilizes the fringing electric field between electrodes to measure the soil's capacitance, which correlates with dielectric permittivity [10].

The measurement frequency significantly impacts sensor performance. High-frequency measurements (≥50 MHz) minimize sensitivity to soil salinity by successfully polarizing water molecules while avoiding polarization of dissolved ions, whereas low-frequency sensors are more susceptible to salinity effects [9].

Spectral Sensing Theory

Spectral sensors operate on the principle that specific plant compounds absorb and reflect light at characteristic wavelengths [11] [12]. Chlorophyll, for instance, strongly absorbs light in the blue and red regions of the spectrum while reflecting green and near-infrared (NIR) light [12]. By measuring reflectance at targeted wavelengths, these sensors non-destructively estimate biochemical constituents.

Advanced spectral sensing technologies include:

- Hyperspectral Spectroscopy: Captures reflectance across hundreds of contiguous narrow bands, providing detailed spectral signatures for quantifying chlorophyll, water content, and other biochemicals [11].

- Multispectral Sensors: Measure reflectance at several discrete, strategically chosen wavelengths, offering a cost-effective alternative for specific applications like chlorophyll estimation [12].

- Spectral Indices: Mathematical combinations of reflectance at specific wavelengths (e.g., NDVI, mND705) used to amplify the signal of target parameters while minimizing background interference [11].

Comparative Performance Analysis: Dielectric Soil Moisture Sensors

Accuracy and Precision Across Sensor Models

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Commercial Capacitive Soil Moisture Sensors

| Sensor Model | Price Range (USD) | Measurement Principle | Reported R² | Reported RMSE (% VWC) | Optimal Moisture Range | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEROS 10 | $200-250 [13] | FDR/Capacitance | N/A | Lowest in class [10] | Full range [10] | High cost limits scalability |

| SMT50 | Mid-range | FDR/Capacitance | N/A | Moderate [10] | Full range [10] | Moderate accuracy |

| Scanntronik | Mid-range | FDR/Capacitance | N/A | Moderate [10] | Full range [10] | Moderate accuracy |

| SEN0193 (DFRobot) | $8-10 [13] | FDR/Capacitance | 0.85-0.87 [13] | 4.5-4.9% [13] | 5-50% VWC [13] | Requires soil-specific calibration; variability at high moisture levels [13] |

Validation Methodologies for Soil Moisture Sensors

Reference Method: Gravimetric Analysis

The thermogravimetric method remains the standard for validating soil water content sensors [13]. This destructive but highly accurate method involves:

- Sample Collection: Extracting a known volume of soil from the immediate vicinity of the sensor post-measurement.

- Fresh Weight Measurement: Weighing the soil sample immediately after collection to determine wet mass.

- Drying Process: Oven-drying the sample at 105°C for 24 hours (duration and temperature may vary based on soil organic matter content).

- Dry Weight Measurement: Weighing the soil sample after complete drying to determine dry mass.

- Calculation: Volumetric Water Content (VWC) is calculated as: VWC = [(Fresh Weight - Dry Weight) / Dry Weight] × Bulk Density Correction Factor [13].

Sensor Calibration Protocol

Proper calibration is essential for accurate capacitive sensor measurements. The standard protocol involves:

- Soil Preparation: Preparing multiple soil samples with gravimetrically-determined moisture contents spanning the expected range (from dry to saturated) [13].

- Sensor Installation: Installing sensors in samples with known water content, ensuring consistent insertion depth and soil contact [10].

- Data Collection: Recording sensor output values for each known water content.

- Curve Fitting: Developing a calibration function (typically linear or polynomial) that relates sensor output to reference VWC values [13].

Table 2: Calibration Performance of SEN0193 Sensor Across Different Soil Types

| Soil Type | Calibration R² | RMSE (cm³/cm³) | Study Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loamy Silt | 0.85-0.87 | 0.045-0.049 | Accurate for smart farming with calibration [13] |

| Clay Loam | ≥0.89 | N/A | Polynomial calibration most suitable [13] |

| Red-yellow Latosol | 0.93-0.96 | 0.08 | Highly correlated with water content [13] |

| Regolitic Neosol | 0.89-0.92 | 0.12 | Good performance with calibration [13] |

| Red Latosol | 0.86-0.88 | 0.15 | Acceptable accuracy with calibration [13] |

| Silty Clay | 0.86 | 0.028 | Suitable for measuring changes during irrigation [13] |

Comparative Performance Analysis: Spectral Plant Sensors

Accuracy and Applications in Plant Phenotyping

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Spectral Sensors for Plant Biochemical Assessment

| Sensor Technology | Target Parameter | Validation Method | Reported R² | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperspectral Spectroscopy [11] | Leaf Water Content (LWC) | Destructive sampling & gravimetric analysis | 0.65-0.67 (PLSR) | Real-time plant water status monitoring | Affected by greenhouse lighting conditions |

| Hyperspectral Spectroscopy [11] | Chlorophyll Content | Spectral indices (e.g., mND705) | 0.51-0.70 | Non-destructive chlorophyll estimation | Accuracy varies with light environment |

| AS7265x Multispectral [12] | Chlorophyll Levels | Chemical extraction (reference method) | 0.95 (smooth leaves) 0.75-0.85 (textured leaves) | Plant nitrogen status assessment | Performance varies with leaf morphology |

| AS7262 Multispectral [12] | Chlorophyll Levels | Chemical extraction (reference method) | 0.86-0.93 (smooth leaves) 0.73-0.85 (textured leaves) | Low-cost chlorophyll sensing | Reduced accuracy on textured leaves |

| AS7263 Multispectral [12] | Chlorophyll Levels | Chemical extraction (reference method) | 0.86-0.93 (smooth leaves) 0.73-0.85 (textured leaves) | Low-cost chlorophyll sensing | Reduced accuracy on textured leaves |

Validation Methodologies for Plant Sensors

Chlorophyll Content Validation

The reference method for validating spectral chlorophyll sensors involves destructive chemical extraction and spectrophotometric analysis:

- Leaf Sample Collection: Harvesting leaf discs or known leaf areas from the same tissues measured by the sensor.

- Pigment Extraction: Grinding tissue samples in organic solvents (e.g., 80% acetone, DMF, or ethanol) to extract chlorophyll.

- Spectrophotometric Analysis: Measuring absorbance of the extract at specific wavelengths (typically 647nm and 664nm).

- Calculation: Using established equations (e.g., Arnon's or Lichtenthaler's equations) to calculate chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll concentrations per unit leaf area or fresh weight [12].

Leaf Water Content Validation

The reference method for leaf water content involves gravimetric analysis:

- Fresh Weight Measurement: Weighing leaf samples immediately after collection.

- Turgid Weight Measurement: Hydrating samples to full turgidity (optional for relative water content).

- Dry Weight Measurement: Oven-drying samples at 60-80°C for 24-48 hours until constant weight.

- Calculation: Leaf Water Content (LWC) = [(Fresh Weight - Dry Weight) / Fresh Weight] × 100% [11].

Experimental Workflows for Sensor Validation

Integrated Sensor Validation Protocol

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials and Reagents for Sensor Validation Studies

| Research Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Precision Oven (105°C capability) | Determination of dry weight for gravimetric analysis | Soil moisture and leaf water content validation [13] |

| Analytical Balance (±0.0001g) | Accurate measurement of sample masses | All gravimetric reference methods [13] |

| Acetone (80%) or DMF | Chlorophyll extraction solvent | Chlorophyll content reference method [12] |

| Spectrophotometer | Absorbance measurement of chlorophyll extracts | Quantification of chlorophyll concentration [12] |

| Calibration Containers | Standardized vessels for soil samples | Capacitive sensor calibration [10] |

| Soil Coring Equipment | Extraction of known soil volumes | Bulk density determination and reference samples [13] |

| Leaf Area Meter | Standardization of leaf tissue area | Chlorophyll content per unit area calculations [12] |

This taxonomic comparison demonstrates that both dielectric and spectral sensors can achieve high correlation with laboratory reference methods when proper validation protocols are implemented. Dielectric soil moisture sensors show the highest accuracy with soil-specific calibration, with research-grade sensors like TEROS 10 outperforming low-cost alternatives, though affordable options like the SEN0193 remain viable with appropriate calibration [10] [13]. Spectral sensors exhibit strong performance for chlorophyll assessment, particularly with advanced modeling techniques like PLSR, though their accuracy is influenced by environmental conditions and plant morphology [11] [12].

The validation framework presented provides researchers with a rigorous methodology for evaluating sensor accuracy against traditional laboratory methods. As sensor technologies continue evolving—incorporating nanotechnology, artificial intelligence, and multimodal sensing [14]—the importance of standardized validation protocols becomes increasingly critical for scientific acceptance and appropriate technological deployment.

In the evolving landscape of agricultural and nutritional science, the demand for precise and reliable data is paramount. For researchers validating the accuracy of novel plant sensors or nutritional biomarkers, a fundamental prerequisite is the establishment of a reference point using gold standard laboratory methods. These reference protocols provide the objective ground truth against which new technologies are benchmarked, ensuring data integrity and supporting valid scientific conclusions. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these reference methods for assessing water status, nutrients, and biomarkers, framing them within the critical context of validation research for plant sensors and other emerging tools.

Defining the "Gold Standard" in Scientific Measurement

A "gold standard" method, often termed a reference method, is characterized by its high accuracy, precision, and reliability. It serves as the definitive procedure for measuring a specific analyte, against which all other methods are calibrated and validated [15]. In nutritional assessment, a gold standard biomarker is defined as a biological characteristic that can be objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or responses to an intervention [16] [15]. The validation of any new sensor or assay requires a direct comparison to this accepted reference to quantify its performance, including its sensitivity, specificity, and limits of detection.

Reference Methods for Plant and Soil Water Status

Accurate water status assessment is critical in plant physiology and agriculture. The following table summarizes the key reference methods for measuring water status in plants and soil.

Table 1: Gold Standard Methods for Assessing Water Status

| Measurement Target | Gold Standard Method | Core Principle | Typical Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil Water Content | Gravimetric Method [17] | Direct measurement of water mass loss upon oven-drying. | 1. Collect undisturbed soil core with a specialized auger.2. Immediately weigh to obtain wet mass.3. Dry in an oven at 105°C for 24-48 hours.4. Weigh again to obtain dry mass.5. Calculate water content as: (wet mass - dry mass) / dry mass. |

| Soil Water Potential | Microtensiometer [18] | Measures the tension (potential) with which water is held in soil pores, mimicking plant root extraction. | 1. Install the microtensiometer sensor at desired root zone depth.2. Allow equilibration with soil water.3. Continuously log the water potential (in units like centibars or MPa).4. The sensor provides a direct reading of the energy status of water, which correlates with plant water stress. |

| Plant Drought Stress | Acoustic Emissions & Stem Diameter [1] | Detection of ultrasonic signals from cavitating xylem vessels and micro-variations in stem girth. | 1. Attach acoustic emission sensors and dendrometers (stem diameter sensors) to plant stems.2. Conduct continuous data logging under controlled or field conditions.3. Withhold irrigation to induce stress.4. Analyze the increase in acoustic emission events and decrease in stem diameter, which are clear early indicators of drought stress [1]. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the process of validating a new plant water sensor against these established reference methods.

Reference Methods for Nutrient and Biomarker Assessment

In nutritional science, the choice of a gold standard is often specific to the nutrient or biomarker of interest. The following section outlines reference protocols for key nutrients.

Table 2: Gold Standard Methods for Key Nutrient Biomarkers

| Nutrient / Biomarker | Gold Standard Method | Core Principle | Key Experimental Protocol Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium & Potassium Intake | 24-Hour Urinary Collection [19] | Complete collection of all urine over 24 hours, as ~90% of ingested Na and K is excreted renally. | 1. Participants discard first morning void, then start collection.2. Collect every urine sample for the next 24 hours, including the first void of the next day.3. Keep samples on ice or refrigerated during collection.4. Total volume is recorded, and aliquots are analyzed for Na and K concentration.5. Controlled feeding studies are the ideal design for validation [19]. |

| Protein Intake | 24-Hour Urinary Nitrogen [16] [15] | Measures total nitrogen excreted in urine over 24 hours, as protein is the primary source of nitrogen in the diet. | 1. Follow the same 24-hour urine collection protocol as for Na/K.2. Analyze urinary urea nitrogen and other nitrogenous compounds.3. Nitrogen levels are used to calculate total protein intake. |

| Nutritional Status (General) | Biomarker of Status in Blood/Tissue [15] | Direct measurement of a nutrient or its metabolite in a biological fluid or tissue. | 1. Collect fasting blood samples (e.g., serum, plasma, erythrocytes).2. Process samples using standardized protocols (e.g., centrifuge, aliquot, flash freeze) to ensure analyte stability.3. Analyze using validated, high-specificity assays (e.g., HPLC, MS, ELISA). |

The process of selecting and applying a nutritional biomarker is guided by a rigorous framework, as shown below.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagent and Material Solutions

Executing gold standard protocols requires specific, high-quality materials. The following table details essential research reagents and their functions in these experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Reference Protocols

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Tensiometer / Microtensiometer | Provides direct, continuous measurement of soil water potential, the key metric for plant-available water [18]. |

| Dendrometer | Measures micro-variations in plant stem diameter, a sensitive indicator of plant water status and growth [1]. |

| Acoustic Emission Sensor | Detects ultrasonic signals produced by cavitation in xylem vessels during drought stress, allowing for early stress detection [1]. |

| 24-Hour Urine Collection Kit | Includes containers, ice packs, and temperature-controlled storage for the complete and stable collection of 24-hour urine samples [19]. |

| Standardized Reference Materials | Certified calibration standards (e.g., for Na, K, Nitrogen) used to ensure the accuracy and traceability of analytical instruments like ICP-MS or HPLC. |

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) & AGP Assays | Used to measure inflammatory markers, which is a critical step in adjusting and interpreting nutrient biomarker concentrations (e.g., iron, zinc) to avoid confounding [20] [15]. |

| Enzyme Activity Assay Kits | Functional biochemical biomarkers; measure the activity of nutrient-dependent enzymes (e.g., glutathione peroxidase for selenium) to assess functional nutrient status [15]. |

Gold standard laboratory methods provide the non-negotiable foundation for scientific advancement in plant physiology and nutrition. Protocols like the gravimetric method for soil moisture, 24-hour urinary excretion for sodium and potassium, and specific biomarkers of status for nutrients represent the benchmark for accuracy. As the field moves forward with innovative technologies like wearable plant sensors and omics-based biomarkers, a rigorous validation process against these reference methods is not merely a procedural step but a fundamental requirement for ensuring data reliability, reproducibility, and ultimately, scientific progress.

The integration of smart sensor technology into plant science represents a paradigm shift from traditional laboratory methods towards real-time, in-situ monitoring. These advanced sensors, leveraging micro-nano technology, flexible electronics, and artificial intelligence (AI), enable dynamic tracking of key physiological and environmental parameters [14] [21]. However, the promise of these technologies can only be realized through rigorous validation, ensuring data reliability for critical decision-making in research and application. As computational modeling plays an increasing role in engineering and science, improved methods for comparing computational results and experimental measurements are needed [22]. The process of establishing model credibility involves both verification—ensuring equations are solved correctly—and validation (V&V), which assesses how accurately a model represents the underlying physics by comparing computational predictions to experimental data [23]. This guide objectively compares the performance of emerging plant sensor technologies against traditional laboratory benchmarks, providing a framework for validating sensor accuracy within plant science research.

Core Validation Metrics: Definitions and Interpretations

Validation metrics provide quantifiable measures to compare computational or sensor results with experimental data, sharpening the assessment of accuracy [22]. In the context of plant sensor technology, several key metrics are essential for evaluation.

The Foundation: Understanding the Confusion Matrix

Most classification metrics derive from the confusion matrix, which tabulates predictions against actual outcomes. For binary classification tasks (e.g., disease present/absent), predictions fall into four categories [24] [25]:

- True Positives (TP): Correctly identified positive cases (e.g., correctly detected disease)

- True Negatives (TN): Correctly identified negative cases (e.g., correctly identified health)

- False Positives (FP): Incorrectly flagged positive cases (false alarms)

- False Negatives (FN): Missed positive cases (missed detections)

Key Metric Definitions and Applications

Table 1: Fundamental Validation Metrics for Classification Models

| Metric | Definition | Formula | Interpretation | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Proportion of all correct classifications | (TP+TN)/(TP+TN+FP+FN) [24] | Overall correctness | Balanced datasets; initial assessment [24] |

| Precision | Proportion of positive predictions that are correct | TP/(TP+FP) [24] | Reliability of positive detection | When false positives are costly [24] |

| Sensitivity (Recall) | Proportion of actual positives correctly identified | TP/(TP+FN) [26] [24] | Ability to detect target condition | Plant disease detection; early warning systems [26] |

| Specificity | Proportion of actual negatives correctly identified | TN/(TN+FP) [26] [25] | Ability to identify absence of condition | Confirming health status; minimizing false alarms [26] |

| F1-Score | Harmonic mean of precision and recall | 2×(Precision×Recall)/(Precision+Recall) [25] | Balanced measure of both metrics | Imbalanced datasets; single performance metric [25] |

These metrics are particularly crucial in plant health monitoring, where visual inspection remains a central tenet of surveys. Understanding their values helps interpret the reliability of detection methods [26]. For example, in automated plant disease detection systems that use machine learning to identify symptoms on leaves, these metrics provide quantifiable measures of model performance beyond simple accuracy [27].

Experimental Protocols for Metric Validation

Validating plant sensor performance requires structured experimental designs that generate the necessary data for calculating these metrics. Different scientific fields have established protocols tailored to their specific validation needs.

Precision Assessment in Analytical Methods

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) provides standardized protocols for determining method precision. The EP05-A2 protocol recommends [28]:

- Testing precision at at least two levels across the analytical range

- Running each level in duplicate, with two runs per day over 20 days

- Separating runs by a minimum of two hours

- Including at least ten patient samples in each run to simulate actual operation

- Using different quality control materials than those used for routine assay control

This structured approach allows for separate estimation of repeatability (within-run precision) and within-laboratory precision (total precision), providing a comprehensive view of method reliability [28].

Validation Metrics for Computational Models

For computational models, validation metrics based on statistical confidence intervals provide quantitative comparisons between computational results and experimental data. These metrics can be applied when system response quantities are measured over a range of input variables [22]. The process involves:

- Data Collection: Measuring the system response quantity across the range of interest

- Interpolation/Regression: Creating a function that represents the experimental data

- Confidence Interval Construction: Building intervals around the experimental curve

- Metric Calculation: Assessing how computational results fall within these intervals

This approach provides an easily interpretable metric for assessing computational model accuracy while accounting for experimental measurement uncertainty [22].

Plant Health Survey Validation

A recent study on visual inspections for acute oak decline symptoms demonstrated an empirical approach to quantifying sensitivity and specificity [26]:

- Design: 23 trained surveyors assessed up to 175 labelled oak trees for three symptoms

- Gold Standard: Comparisons against an expert who monitored the same trees annually for over a decade

- Analysis: Calculation of sensitivity and specificity for each surveyor and symptom

- Extension: Bayesian modeling to estimate sensitivity and specificity without gold-standard data

This protocol revealed large variations in sensitivity and specificity between individual surveyors and between different symptoms, highlighting the importance of standardized validation [26].

Comparative Performance: Sensor Technologies vs. Traditional Methods

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Plant Monitoring Technologies

| Technology Type | Typical Applications | Reported Strengths | Common Limitations | Validation Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wearable Plant Sensors [14] [21] | Real-time monitoring of physiological parameters (e.g., H2O2, salicylic acid) [14] | In-situ, continuous monitoring; high temporal resolution [14] [21] | Signal cross-sensitivity; limited long-term stability [21] | Interface with dynamic plant surfaces; environmental interference [21] |

| Hyperspectral Imaging [27] | Disease detection; nutrient status assessment | Non-invasive; large area coverage; rich spectral data [27] | High cost; complex data processing; atmospheric interference [27] | Calibration across conditions; distinguishing similar spectral signatures [27] |

| Electronic Noses (Gas Sensing) [21] | Detection of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) | Real-time monitoring; non-destructive; high sensitivity [21] | Sensitivity to environmental factors; calibration drift [21] | Reproducibility across devices; humidity/temperature compensation [21] |

| Traditional Laboratory Methods (e.g., chromatography) [29] | Reference measurements for chemical analytes | High precision and accuracy; well-established protocols [29] | Destructive sampling; low temporal resolution; labor intensive [21] | Sample representativeness; preparation artifacts; cost for large samples [29] |

The data reveals that while novel sensors excel in temporal resolution and in-situ capability, traditional methods maintain advantages in precision and established reliability. For instance, chromatography-mass spectrometry methods can be rigorously validated through structured protocols involving repeated calibration curves across multiple days [29], providing a gold standard against which sensor performance can be measured.

Visualization of the Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for validating plant sensor accuracy against traditional methods, incorporating the key metrics and experimental approaches discussed:

Figure 1: Plant Sensor Validation Workflow. This diagram illustrates the comprehensive process for validating plant sensor accuracy against traditional laboratory methods, from data acquisition through final performance assessment.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Sensor Validation Studies

| Material/Reagent | Function in Validation | Application Context | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards [29] | Calibration and accuracy verification | Chromatographic methods; sensor calibration | Purity certification; stability; matrix matching |

| Quality Control Materials [28] | Precision assessment across runs | Monitoring assay performance over time | Commutability with patient samples; stability |

| Sensor Substrates [14] | Platform for sensor fabrication | Flexible/wearable plant sensors | Biocompatibility; mechanical properties; adhesion |

| Nanomaterials (e.g., SWNTs) [14] | Signal transduction and enhancement | Nanosensors for plant biomarkers | Functionalization; selectivity; potential phytotoxicity |

| Data Fusion Algorithms [21] | Integrating multiple sensor inputs | Multimodal sensing systems | Computational demands; interpretation complexity |

The validation of plant sensor technology requires a multifaceted approach that objectively quantifies performance across multiple metrics. While advanced sensors show tremendous promise for real-time plant monitoring, their adoption must be grounded in rigorous comparison against traditional methods using standardized protocols. Accuracy, precision, sensitivity, and specificity each provide distinct insights into different aspects of sensor performance, with the appropriate emphasis depending on the specific application. No single metric tells the complete story—effective validation requires a comprehensive approach that considers the interplay of all these measures alongside practical implementation factors. As the field advances, continued refinement of validation frameworks will be essential for bridging the gap between technological promise and reliable application in plant science research.

Designing a Rigorous Validation Study: Protocols and Best Practices

The integration of real-time plant monitoring sensors into smart agriculture represents a paradigm shift from traditional, destructive laboratory methods towards dynamic, in-situ data acquisition [21]. These sensors, leveraging advancements in flexible electronics, nanomaterials, and artificial intelligence, enable the continuous tracking of key physiological and environmental parameters [21]. However, their transition from controlled laboratory demonstrations to robust, field-deployable solutions is impeded by challenges including limited long-term stability, signal cross-sensitivity, and a lack of standardized validation frameworks [21]. This guide provides a structured blueprint for a controlled side-by-side experiment, designed to objectively quantify the accuracy and reliability of novel plant sensors against established laboratory benchmarks. The core objective is to furnish researchers with a methodological foundation to rigorously evaluate sensor performance, thereby bridging the critical gap between innovative development and practical, reliable application in precision agriculture and pharmaceutical botany.

Experimental Design and Hierarchy of Evidence

A well-constructed research design is the framework for planning, implementing, and analyzing a study to ensure its findings are trustworthy and meaningful [30]. Quantitative research designs exist in a hierarchy of evidence, largely determined by their internal validity—the extent to which the results are free from bias and errors, ensuring that observed effects are truly due to the variables being studied [30].

For validating plant sensor accuracy, a quasi-experimental design is often the most feasible and rigorous approach. This design attempts to establish a cause-effect relationship between the measurement method (sensor vs. laboratory) and the resulting data [31]. It involves intervening by deploying the sensors and comparing their outputs to a control—the laboratory standard. While a true experiment with random assignment is the gold standard, it is often impractical for field-based agricultural research [32]. A quasi-experimental design provides a robust alternative for comparing the new technology against the traditional method under controlled conditions [31].

Table 1: Key Elements of the Quasi-Experimental Research Design

| Element | Application in Sensor Validation | Role in Establishing Validity |

|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | The measurement method (e.g., Real-time Sensor vs. Laboratory Analysis) | The factor manipulated to observe its effect on the dependent variable. |

| Dependent Variable | The quantified value of the target parameter (e.g., sap flow rate, hormone concentration). | The outcome that is measured and compared between the two methods. |

| Hypothesis | The real-time sensor measurements will not significantly differ from laboratory measurements beyond a predefined margin of error. | A specific, testable prediction about the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. |

| Control | The use of traditional, laboratory-grade analytical methods as a benchmark. | Provides a baseline against which the new sensor technology is evaluated. |

Baseline Logic for Experimental Reasoning

The experimental reasoning for this validation study follows a baseline logic inherent in single-subject or single-system designs, which is highly applicable to testing on individual plants [33]. This logic comprises four key elements:

- Prediction: The anticipated result that the sensor readings will deviate from laboratory values without calibration or intervention.

- Affirmation of the Consequent: When the sensor is deployed (the intervention), a change in measurement accuracy is observed and is potentially linked to the sensor technology.

- Verification: Demonstrating that the relationship is controlled by the measurement method, for instance, by showing that sensor data, without calibration, consistently differs from the verified laboratory baseline.

- Replication: Reintroducing the comparison across multiple plant subjects, time points, or environmental conditions. If the results are consistently similar, it strengthens the proof of the sensor's reliability (or lack thereof) [33].

This process depends on a steady-state strategy, where experimental conditions are introduced only after stable patterns are established, confirming that any changes in measurement accuracy are due to the specific conditions being tested [33].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the overarching workflow for the side-by-side validation experiment, from initial setup to final data synthesis.

Detailed Methodology for Key Experiments

Physical Growth Monitoring

This protocol validates sensors designed to measure physical deformation and growth.

- Objective: To compare sensor-measured stem diameter micro-variations against laboratory caliper measurements.

- Materials:

- Plant wearables with integrated flexible strain sensors [21].

- High-precision digital calipers (laboratory standard).

- Data logger.

- Procedure:

- Select a cohort of 20 plants of the same developmental stage.

- Attach the strain sensors to the plant stems, ensuring mechanical adaptation to the plant surface interface [21].

- Program sensors to record resistance/capacitance measurements at 15-minute intervals for 14 days.

- Simultaneously, at 8-hour intervals, carefully take caliper measurements at the exact sensor location on a subset of 5 plants, which are then destructively sampled.

- Correlate the electrical signals from the sensors (e.g., resistance changes) with the physical displacement measurements from the calipers.

Chemical Signaling Sensing

This protocol validates sensors for detecting sap-borne chemicals, such as phytohormones.

- Objective: To compare in-situ electrochemical sensor readings of salicylic acid concentration with benchmark analyses from High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC).

- Materials:

- Electrochemical sensors utilizing molecular recognition elements (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) [21].

- HPLC system with UV detection.

- Micro-syringes for sap extraction.

- Procedure:

- Induce a systemic acquired resistance response in 15 plants by pathogen-associated molecular patterns.

- Implant or affix electrochemical sensors into the vascular tissue of the plants.

- Continuously monitor the amperometric or potentiometric signal.

- At 2, 6, 12, 24, and 48 hours post-induction, destructively harvest 3 plants.

- Collect sap from the stems and analyze salicylic acid concentration using HPLC.

- Normalize the sensor signal from the remaining plants against the HPLC-derived concentration values from the harvested plants to create a calibration curve.

Environmental Stress Response

This protocol validates multi-modal sensors that capture plant responses to abiotic stress.

- Objective: To correlate a sensor fusion data output (humidity, leaf temperature, sap flow) with integrated laboratory measures of plant water status.

- Materials:

- Multi-parameter sensor system (e.g., combining humidity, temperature, and sap flow sensors) [21].

- Pressure bomb for measuring leaf water potential (laboratory standard).

- Chlorophyll fluorimeter for measuring photosynthetic efficiency.

- Procedure:

- Subject a group of 10 plants to progressive water deficit.

- Record data from all sensor channels every hour.

- Daily, take measurements from all plants using the pressure bomb and chlorophyll fluorimeter.

- Use multivariate statistical models (e.g., multiple regression) to predict the laboratory-measured water potential and photosynthetic efficiency using the real-time sensor data streams as predictors.

Data Presentation and Analysis

The core of the validation lies in the systematic comparison of quantitative data generated from the side-by-side experiments.

Table 2: Sensor vs. Laboratory Performance Data for Salicylic Acid Monitoring

| Time Post-Induction (hours) | HPLC Reference (µg/g) | Sensor Reading (µg/g) | Absolute Difference | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 0.2 | 13.3 |

| 6 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.5 | 0.3 | 7.9 |

| 12 | 12.1 ± 1.1 | 11.5 ± 1.4 | -0.6 | -5.0 |

| 24 | 8.5 ± 0.7 | 9.2 ± 0.9 | 0.7 | 8.2 |

| 48 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | -0.2 | -6.9 |

Table 3: Statistical Comparison Metrics Across Different Sensor Types

| Target Parameter | Reference Method | Validation Metric | Result | Inference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stem Diameter | Digital Caliper | Pearson's r (Correlation) | r = 0.95, p < 0.01 | Strong positive correlation |

| Sap Flow Rate | Thermodynamic Model | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | 0.12 mL/min | Good agreement with reference |

| Leaf Chlorophyll | HPLC Analysis | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | 0.15 µg/cm² | High accuracy |

| Vapor Pressure Deficit | Psychrometer | Coefficient of Determination (R²) | R² = 0.89 | Sensor explains 89% of variance |

Signaling Pathways and Plant-Sensor Interaction Logic

Understanding the biological context and the technological interface is crucial for interpreting validation data. The following diagram maps the logical relationship between plant stress, the resulting physiological signals, the sensing mechanism, and the final validated data output.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for executing the controlled validation experiments described in this guide.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Plant Sensor Validation

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Flexible Strain Sensors | Continuous monitoring of physical growth and deformation. | Composed of conductive materials (e.g., carbon nanotubes, graphene) whose resistance/capacitance changes linearly with deformation [21]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Selective recognition and binding of target chemical analytes (e.g., specific phytohormones). | Synthetic polymers with cavities complementary to the target molecule in shape, size, and functional groups, serving as artificial antibodies [21]. |

| Aptamer-based Biosensors | Highly specific detection of metabolites and pathogens. | Short, single-stranded DNA or RNA molecules that bind to a specific target; integrated into electrochemical or optical sensors [21]. |

| Electrochemical Transducers | Conversion of a chemical or biological event into a quantifiable electrical signal. | Devices (e.g., electrodes) that measure changes in current (amperometry) or potential (potentiometry) resulting from redox reactions at their surface [21]. |

| Nano-enhanced Substrates | Amplification of detection signals for trace-level analytes. | Materials (e.g., for Surface Plasmon Resonance or Raman spectroscopy) that enhance the local electromagnetic field, improving sensitivity and limit of detection [21]. |

| Biodegradable/Edible Substrates | Sustainable sensor encapsulation and deployment. | Materials such as silk proteins or plant-based polymers that host the electronic components, minimizing environmental impact and plant tissue damage [21]. |

For researchers validating plant sensor accuracy against traditional laboratory methods, the integrity of the entire research endeavor hinges on two critical pillars: deploying sensors in a way that captures representative data and installing them correctly to ensure data fidelity. The choice between a novel, in-situ sensor and a standard laboratory technique is only as sound as the deployment strategy behind it. Representative sampling ensures that the collected data accurately reflects the spatial and temporal variability of the environment or population being studied, while proper installation minimizes measurement error and ensures the sensor's performance aligns with its laboratory-based specifications. This guide provides a structured approach to these processes, supported by experimental data and best practices from current research.

The Critical Role of Representative Sampling

Deploying a limited number of sensors across a large area, such as multiple fields or a diverse greenhouse, presents a significant challenge. A non-systematic approach can lead to biased data that misrepresents the true conditions. Cluster analysis has emerged as a robust, data-driven methodology to address this issue.

A Cluster Analysis Approach to Sampling

This method involves grouping potential sensor deployment sites into clusters based on key factors that are likely to influence the sensor's measurements. The goal is to create groups of sites that are internally similar but externally different from other groups. By then sampling a few sites from each cluster, researchers can achieve a subset that captures the full diversity of the population.

- Methodology: For a study on gas, water, and environmental sensors, clusters of nearly 300 potential sites were created using known site characteristics. A few sites were then selectively chosen from each cluster for sensor installation [34].

- Verification: The success of this approach was verified by analyzing the resulting sensor data, which showed clear variations across the different clusters. The data demonstrated that the cluster-based sampling successfully captured the environmental differences influenced by the initial grouping factors [34].

- Application: This method is generalizable to plant sensor research. Potential clustering factors could include soil type, microclimate, plant species, plant health status, or topography. This ensures that sensors are not all placed in, for instance, only the most fertile or most stressed areas, but rather provide a complete picture of the experimental conditions.

Quantitative Sensor Performance Comparison

Selecting a sensor requires a clear understanding of its performance characteristics. The following table summarizes experimental data for various sensors used in plant and environmental monitoring, providing a direct comparison of their capabilities.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Select Sensor Technologies

| Sensor Technology | Key Measured Parameter | Performance Data | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acoustic Emission [1] | Early drought stress | Significant indicator within 24 hrs of water withdrawal; reacts at 50% water content of control. | Mature tomato plants in greenhouse; rockwool substrate. |

| Stem Diameter Variation [1] | Early drought stress | Significant indicator within 24 hrs of water withdrawal; reacts at 50% water content of control. | Mature tomato plants in greenhouse; rockwool substrate. |

| Stomatal Dynamics [1] | Stomatal pore area & conductance | Significant indicator within 24 hrs of water withdrawal; reacts at 50% water content of control. | Mature tomato plants in greenhouse; rockwool substrate. |

| Graphene/Ecoflex Strain Sensor [35] | Plant growth patterns & mechanical damage | High sensitivity (Gauge Factor = 138); 0.1% strain detection limit; reliable for >1,500 cycles. | Attached to plant leaves/stems for real-time monitoring. |

| Sap Flow Sensor [1] | Whole-plant transpiration | Did not reveal signs of early drought stress in mature tomato plants. | Mature tomato plants in greenhouse; rockwool substrate. |

| PSII Quantum Yield Sensor [1] | Photosynthetic efficiency | Did not reveal signs of early drought stress in mature tomato plants. | Mature tomato plants in greenhouse; rockwool substrate. |

| Top Leaf Temperature Sensor [1] | Leaf surface temperature | Did not reveal signs of early drought stress in mature tomato plants. | Mature tomato plants in greenhouse; rockwool substrate. |

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Validation

To ensure that sensor data is reliable and comparable to laboratory standards, rigorous experimental protocols must be followed. These methods are adapted from sensor lab best practices and environmental monitoring guidelines.

Controlled Target Setup for Functional Tests

- Purpose: To validate a sensor's functional detection capabilities (e.g., presence, motion, response to stress) under controlled conditions [36].

- Protocol: Use mechanical actuators, guided walks, or in the case of plant sensors, standardized stimuli like controlled water deprivation to simulate a specific event [36] [1]. For plant drought stress, this involves withholding irrigation for a defined period (e.g., two days) and monitoring the substrate water content [1].

- Ground-Truth Capture: Employ independent systems to validate sensor readings. In plant studies, this could involve destructive sampling for physiological measurements (e.g., leaf water potential) or using non-visual methods like pressure mats to corroborate the sensor's output [36].

Environmental Robustness Testing

- Purpose: To evaluate how environmental variables like temperature, humidity, and air currents affect sensor accuracy and drift [36].

- Protocol: Place sensors in an environmental chamber that can systematically vary temperature and humidity. For outdoor sensors, tests should include resistance to water, acids, and alkalis to simulate field conditions like pesticide exposure or rain [35].

- Data Analysis: Measure the sensor's accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity across the tested environmental range to quantify its operational limits [36].

Collocation for Sensor Evaluation

- Purpose: To assess the accuracy of a new sensor by comparing its data with that from a regulatory-grade or established reference instrument [37].

- Protocol: Operate the sensor under evaluation alongside the reference monitor at the same location and for a defined period under real-world conditions. This is crucial for validating air quality sensors but is equally applicable for environmental parameters relevant to plants [37].

- Data Comparison: Compare the time-series data from both devices, looking for agreement in trends and magnitudes. Systematic differences can be used to calibrate the new sensor.

Sensor Deployment and Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for deploying sensors and validating their data, integrating the concepts of representative sampling and experimental testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful sensor deployment relies on a suite of tools and materials beyond the sensors themselves. The following table details key solutions and their functions in a typical deployment and validation study.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Sensor Deployment and Validation Research

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Environmental Chambers | Systematically vary temperature and humidity to test sensor robustness and identify failure modes [36]. |

| Laser-Processed Graphene/Ecoflex Composite | Serves as a highly sensitive, stretchable, and waterproof sensing material for detecting subtle plant deformations like stem swelling or leaf curling [35]. |

| Reference Monitors (FRM/FEM) | Provide regulatory-grade data for collocation studies, serving as the "ground truth" against which new sensor accuracy is evaluated [37]. |

| Controlled Growth Substrates (e.g., Rockwool) | Enable precise and uniform control of root zone conditions (e.g., water content) for creating standardized plant stress scenarios in validation experiments [1]. |

| Prescription Maps (from Drone Imagery) | Geospatial maps of canopy vigor or other traits used to direct variable-rate application systems, validating that sensor-triggered actions are spatially accurate [38]. |

| Statistical Test Plans | Pre-defined experimental designs including sample sizes, run counts, and confidence intervals to prevent biased conclusions and ensure statistical power [36]. |

Best Practices for Proper Sensor Installation

The physical placement and installation of a sensor are just as critical as its selection. Poor installation can introduce significant error, invalidating even the most carefully designed sampling strategy.

- Ensure Free Air Flow: Sensors must be placed to allow for free flow of the medium they are measuring. Avoid locations where buildings, fences, trees, or other equipment can obstruct air movement or create biased measurements [37].

- Avoid Localized Sources and Sinks: Position sensors away from hyperlocal pollution sources (e.g., building exhausts, dusty roads) or sinks (e.g., vegetation that filters particulate matter or reacts with ozone) that are not representative of the area of interest [37].

- Consider Height and Security: For environmental and exposure studies, place sensors approximately 3-6 feet above the ground, near the typical breathing zone. The location should also be secure to prevent tampering or theft, while considering the installer's physical safety during maintenance [37].

- Verify Power and Communications: Ensure the site can support the sensor's power needs (e.g., AC power, solar panels) and communication protocols (e.g., cellular, Wi-Fi). Areas with public safety power shutoffs may benefit from backup solar power to maintain data continuity [37].

- Plan for Ground-Truthing: Design the installation to facilitate ground-truth capture. This means ensuring that the sensor is placed in a way that allows for concurrent, independent measurements (e.g., manual plant physiology readings) without interfering with its operation [36].

The validation of novel plant sensors against traditional laboratory methods is a multi-faceted process where confidence in the results is built upon a foundation of rigorous deployment and installation. By adopting a systematic, cluster-based approach to sampling, researchers can ensure their data is representative of the true population variance. Furthermore, by adhering to strict experimental protocols for validation and following field-tested best practices for installation, the data acquired can be trusted for critical research and development decisions. This holistic approach to sensor deployment and data acquisition is indispensable for advancing the reliability and adoption of new sensing technologies in plant science and precision agriculture.

For researchers validating plant sensor accuracy against traditional laboratory methods, maintaining sample integrity from field collection to laboratory analysis is paramount. The chain-of-custody (CoC) process provides the documented foundation that ensures analytical results from traditional lab methods are reliable enough to serve as validation benchmarks for emerging sensor technologies. Deviations during this initial phase often lead to costly re-testing or invalid results that can compromise entire validation studies [39]. In the context of agricultural and environmental research, proper CoC procedures track samples from the moment of collection through transport, receipt, and final analysis, creating an unbroken chain of accountability that supports the validity of analytical results [40].

This guide compares CoC approaches for soil and plant tissue samples, providing experimental protocols and data presentation formats essential for researchers who must synchronize field sampling with laboratory analysis. Proper CoC documentation is not merely administrative—it establishes the legal defensibility of data and ensures compliance with regulatory standards from agencies such as the EPA and FDA [39]. For research comparing novel plant wearable sensors to traditional methods, robust CoC protocols provide the credibility foundation that allows innovative monitoring technologies to gain scientific acceptance.

Chain-of-Custody Fundamentals: A Comparative Framework

Core Components of Effective CoC Systems

A robust chain-of-custody program requires several interconnected components that work together to preserve sample integrity. The fundamental elements include comprehensive documentation, proper sample handling procedures, and continuous tracking mechanisms [41]. These components maintain an unbroken record of sample possession and handling conditions throughout the entire analytical process.

Documentation Requirements: CoC forms must capture specific information including sample identification numbers, collection location coordinates, date and time stamps, collector signatures, and detailed descriptions of sampling methods used [40]. For soil and plant tissue research, additional metadata such as GPS coordinates, soil horizon depth, plant developmental stage, and environmental conditions at collection time provide crucial contextual information for data interpretation.

Sample Integrity Controls: Proper preservation techniques prevent analyte degradation during transit, which is especially critical for volatile compounds or labile parameters in plant tissues [39]. Temperature controls, chemical fixation, and adherence to specified holding times are essential for maintaining sample stability. Monitoring devices such as temperature loggers placed within shipping coolers provide objective evidence of proper handling conditions during transport [39].

Transfer Protocols: Each person handling samples must sign transfer documents, noting the condition of samples upon receipt and any observations about potential contamination or damage [40]. This creates clear responsibility for samples at every stage and prevents unauthorized access that could compromise sample integrity.

Comparative Analysis: Traditional Paper-Based vs. Digital CoC Systems

The transition from paper-based to digital CoC systems represents a significant advancement in sample tracking technology. The table below compares key aspects of both approaches for soil and plant tissue sampling workflows:

Table: Comparison of Traditional Paper-Based and Digital Chain-of-Custody Systems

| Feature | Traditional Paper-Based CoC | Digital CoC Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Data Integrity | Prone to transcription errors, illegible handwriting, and physical damage [39] | Real-time synchronization with automated error checking [39] |

| Sample Tracking | Manual entries on standardized forms [42] | Barcode/QR code scanning with instant database updates [39] [41] |

| Geolocation Data | Manual coordinate entry with potential errors | GPS integration automatically records exact collection coordinates [39] |

| Accessibility | Physical forms travel with samples, risk of loss | Cloud-based platforms enable real-time remote monitoring [40] |

| Audit Trail | Paper trail requiring manual compilation | Comprehensive electronic audit trails with timestamps [41] |

| Implementation Cost | Lower initial investment, higher long-term labor costs | Higher initial setup, reduced labor requirements and error correction |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Well-established but vulnerable to challenges | Increasingly accepted with proper validation [41] |

Digital CoC systems integrated with Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) demonstrate particular advantages for research applications requiring high temporal resolution or large sample volumes. For plant sensor validation studies, digital systems provide the precise timestamps and environmental condition tracking necessary for correlating sensor readings with traditional laboratory analyses [39].

Experimental Protocols for Soil and Plant Tissue Sampling

Standardized Field Collection Procedures

Establishing consistent field sampling protocols minimizes variability before samples reach the laboratory, ensuring analytical results truly represent field conditions rather than collection artifacts [39]. The following protocols provide methodologies suitable for research comparing sensor data to traditional laboratory analyses.

Soil Sample Collection Protocol

Site Preparation: Clearly mark sampling locations using GPS technology, recording exact coordinates with <3-meter accuracy. Document surrounding conditions including vegetation cover, slope, and recent weather events [43].

Equipment Preparation: Use pre-cleaned, non-contaminating tools (stainless steel soil corers, plastic trowels). Prepare sample containers in advance with pre-printed labels containing unique identifiers. Triple-rinse containers with sample water when collecting for water quality analysis [44].

Collection Procedure: For composite sampling, collect multiple subsamples from within a defined area according to experimental design. For soil nutrient analysis, standardize collection depth based on crop root zone (typically 0-15cm for shallow-rooted plants, 0-30cm for deeper-rooted crops) [39]. Place samples in appropriate containers, excluding stones and debris.

Preservation and Packaging: Immediately place samples in cooled containers. For certain analyses, chemical preservatives may be required (e.g., sulfuric acid for specific nutrient analyses) [44]. Implement strict safety protocols when using preservatives, including appropriate personal protective equipment.

Plant Tissue Sample Collection Protocol

Plant Selection: Identify plants representing the population of interest, avoiding edge plants or those showing unusual characteristics unless specifically targeted. Document developmental stage using standardized phenological scales [39].

Tissue Collection: For most nutrient analysis, collect recently matured leaves from the current growing season. Use clean cutting instruments to avoid contamination. For sensor validation studies, collect tissue from locations adjacent to sensor placement to ensure direct comparability.

Handling and Preservation: Place samples immediately in labeled paper bags for drying or in cooled containers for fresh tissue analysis. For volatile organic compound analysis, use specialized containers that minimize headspace and preserve chemical signatures [45].

Documentation: Record precise collection time, environmental conditions (temperature, humidity, light intensity), and plant health observations. For sensor validation, document simultaneous sensor readings to enable direct comparison.

Method Validation and Verification Protocols

For laboratory results to serve as reliable benchmarks for sensor validation, the analytical methods themselves must be properly validated. The distinction between method validation and verification is crucial for research laboratories [46]:

Method Validation: A comprehensive process required when developing new analytical methods or modifying existing ones. Validation proves an analytical method is acceptable for its intended use through assessment of accuracy, precision, specificity, detection limit, quantitation limit, linearity, and robustness [46].

Method Verification: A confirmation that a previously validated method performs as expected under specific laboratory conditions. Verification is typically employed when adopting standard methods in a new lab or with different instruments [46].

For sensor validation studies, the comparison of methods experiment is particularly relevant for assessing systematic errors between traditional laboratory methods and sensor outputs [47]. The following protocol outlines key considerations:

Table: Experimental Parameters for Method Comparison Studies

| Parameter | Minimum Requirement | Optimal Practice | Application to Sensor Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Number | 40 patient specimens [47] | 100-200 specimens [47] | Include samples spanning expected concentration range |

| Analysis Replicates | Single measurements [47] | Duplicate measurements [47] | Multiple sensor readings during sample collection |

| Time Period | 5 days [47] | 20 days [47] | Seasonal variations for environmental sensors |

| Concentration Range | Medically important decision levels [47] | Entire working range [47] | Full operational range of sensors |

| Data Analysis | Linear regression, correlation coefficient [47] | Deming or Passing-Bablok regression for r<0.975 [48] | Accounting for different error structures between methods |

The comparison of methods experiment should be designed to estimate systematic errors that occur with real samples. For plant sensor validation, this means analyzing the same sample population both with the sensors and traditional laboratory methods, then estimating systematic differences at critical decision concentrations [47].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table: Essential Research Materials for Soil and Plant Tissue Analysis

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | CoC Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Containers | 250mL preserved and non-preserved bottles [44], sterile containers, volatile organic compound (VOC) vials | Maintain sample integrity between collection and analysis | Pre-labeling, preservation requirements, container material compatibility |

| Preservation Reagents | Sulfuric acid, other chemical preservatives [44], desiccants for dry samples | Prevent analyte degradation during transport and storage | Safety documentation, handling procedures, compatibility with analytical methods |

| Tracking Systems | Pre-printed labels, barcodes, QR codes, RFID tags [39] [40] | Sample identification and tracking throughout analytical process | Unique identifier systems, scanability after field exposure, data integration with LIMS |

| Field Equipment | Soil corers, GPS devices, thermometers, cutting tools, personal protective equipment | Standardized sample collection and documentation | Calibration records, cleaning protocols between samples, maintenance logs |

| Shipping Materials | Coolers, ice packs, leak-proof containers, absorbent materials [44] | Maintain temperature control and prevent contamination during transport | Temperature monitoring documentation, packaging integrity verification |

| Documentation Tools | Chain of Custody forms (paper or digital) [42] [43], field notebooks, digital cameras | Record sampling conditions, handling procedures, and transfers | Completeness requirements, signature chains, correction procedures |

Workflow Visualization: Traditional vs. Sensor-Integrated Approaches

Traditional Chain-of-Custody Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential workflow for traditional chain-of-custody procedures in soil and plant tissue analysis:

Traditional Chain-of-Custody Workflow

Sensor-Integrated Validation Workflow

For research validating plant wearable sensors against traditional laboratory methods, the chain-of-custody workflow incorporates parallel data streams:

Sensor-Integrated Validation Workflow

Comparative Data Analysis and Interpretation

Statistical Approaches for Method Comparison

When comparing traditional laboratory methods with sensor outputs, appropriate statistical analysis is essential for meaningful interpretation. The comparison of methods experiment is specifically designed to estimate systematic errors between measurement techniques [47]. For sensor validation studies, the following statistical approaches are recommended:

Graphical Analysis: Create difference plots (Bland-Altman plots) displaying the difference between sensor readings and laboratory results on the y-axis versus the laboratory reference result on the x-axis. This visualization helps identify potential constant or proportional systematic errors [47].

Regression Statistics: For data spanning a wide analytical range, linear regression statistics provide estimates of both constant error (y-intercept) and proportional error (slope). The systematic error at critical decision concentrations can be calculated using the regression equation: Yc = a + bXc, where SE = Yc - Xc [47].

Correlation Assessment: While the correlation coefficient (r) is commonly calculated, it is more useful for assessing whether the data range is wide enough to provide good estimates of slope and intercept rather than judging method acceptability [47]. Values of 0.99 or larger generally indicate adequate concentration range for regression analysis.

Performance Acceptance Criteria