Benchmarking Plant Phenotyping Algorithms: Validating Automated Methods Against Manual Measurements for Robust Crop Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive framework for benchmarking automated plant phenotyping algorithms against traditional manual measurements, a critical step for validating these tools in crop breeding and agricultural research.

Benchmarking Plant Phenotyping Algorithms: Validating Automated Methods Against Manual Measurements for Robust Crop Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for benchmarking automated plant phenotyping algorithms against traditional manual measurements, a critical step for validating these tools in crop breeding and agricultural research. It explores the foundational need to overcome the bottlenecks of labor-intensive, subjective manual phenotyping. The article details methodological advances in high-throughput techniques, from 3D sensing and deep learning to novel training-free skeletonization algorithms. It further addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges, including data redundancy and sensor limitations, and presents a comparative analysis of validation studies that benchmark self-supervised versus supervised learning methods. This synthesis is designed to equip researchers and scientists with the knowledge to critically evaluate and implement reliable, scalable phenotyping solutions.

From Rulers to Algorithms: The Imperative for Automated Phenotyping

In the pursuit of global food security, crop breeding stands as a critical endeavor, increasingly reliant on advanced genetic analysis techniques. However, a significant constraint has emerged: the phenotyping bottleneck. This term refers to the critical limitation imposed by traditional, manual methods of measuring plant traits, which have become incapable of keeping pace with the rapid advancements and scale of genomic research [1]. While whole-genome sequencing has ushered agriculture into a high-throughput genomic era, the acquisition of large-scale phenotypic data has become the major bottleneck hindering functional genomics studies and crop breeding programs [2].

Plant phenotyping encompasses the quantitative and qualitative assessment of a plant's morphological, physiological, and biochemical properties—the visible expression of its genetic makeup interacting with environmental conditions [3]. These measurements are essential for understanding gene function, selecting desirable traits, and developing improved crop varieties. Manual phenotyping methods are notoriously labor-intensive, time-consuming, prone to human error, and often require destructive sampling [3]. They are inherently low-throughput, limiting the number of plants that can be evaluated and constraining the statistical power of breeding experiments. Furthermore, manual measurements introduce subjectivity and inconsistency, compromising data quality and reproducibility across different research groups and over time [4]. This bottleneck ultimately slows progress in crop improvement, delaying the development of high-yielding, climate-resilient varieties urgently needed to address the challenges of a growing global population and climate change.

Quantitative Comparison: Manual vs. Automated Phenotyping

The limitations of manual phenotyping and the advantages of automated approaches become starkly evident when comparing their performance across key metrics. The following table synthesizes quantitative and qualitative differences based on recent research and technological evaluations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison Between Manual and Automated Phenotyping Methods

| Performance Metric | Manual Phenotyping | Automated/High-Throughput Phenotyping |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput (plants/day) | Low (tens to hundreds) [3] | High (hundreds to thousands) [3] |

| Trait Measurement Accuracy | Subjective, variable, and often lower, especially for 3D traits [4] | Highly accurate and consistent (e.g., millimeter accuracy in 3D) [5] |

| Data Objectivity | Prone to human bias and error [3] | Fully objective and algorithm-driven [4] |

| Destructive Sampling | Often required for key traits [3] | Primarily non-destructive, enabling longitudinal studies [5] [3] |

| Labor Cost & Time | Very high, major bottleneck [6] [1] | Significantly reduced after initial investment [7] |

| Complex 3D Trait Extraction | Difficult or impossible (e.g., plant architecture, leaf area) [4] | Readily achievable via 3D point clouds [4] [5] |

| Temporal Resolution | Low, limited by labor | High, enables monitoring of diurnal patterns and growth [5] |

A compelling case study demonstrating this performance gap comes from the development of the TomatoWUR dataset. Researchers noted that manual measurements of 3D phenotypic traits, such as plant architecture, internode length, and leaf area, are "biased, time-intensive, and therefore limited to only a few plants" and are "difficult to extract manually" [4]. In contrast, automated digital phenotyping solutions using 3D point clouds overcome these limitations, providing a means to extract these traits accurately and efficiently from a large number of plants [4].

Benchmarking Frameworks and Experimental Protocols

The transition to automated phenotyping necessitates robust, standardized methods to validate new technologies and algorithms against traditional measurements. Benchmarking frameworks are essential to ensure that automated data is both accurate and biologically meaningful.

The PhEval Framework for Algorithm Benchmarking

In the domain of rare disease diagnosis, a parallel challenge exists in benchmarking variant and gene prioritisation algorithms (VGPAs). The PhEval framework was developed to provide a standardized, empirical framework for this purpose, addressing issues of reproducibility and a lack of open data [8] [9]. While focused on human medicine, PhEval's core principles are directly applicable to plant sciences. It provides:

- Standardized Test Corpora: Openly available, standardized datasets from real-world cases.

- Tooling Configuration Control: Managed execution of algorithms with controlled parameters to ensure fair comparisons.

- Output Harmonization: Transformation of diverse algorithm outputs into a uniform format for consistent evaluation [8].

Adopting a similar framework in plant phenotyping would solve analogous problems of data availability, tool configuration, and reproducibility, enabling transparent and comparable benchmarking of phenotyping algorithms.

General Workflow for Validating Automated Phenotyping Systems

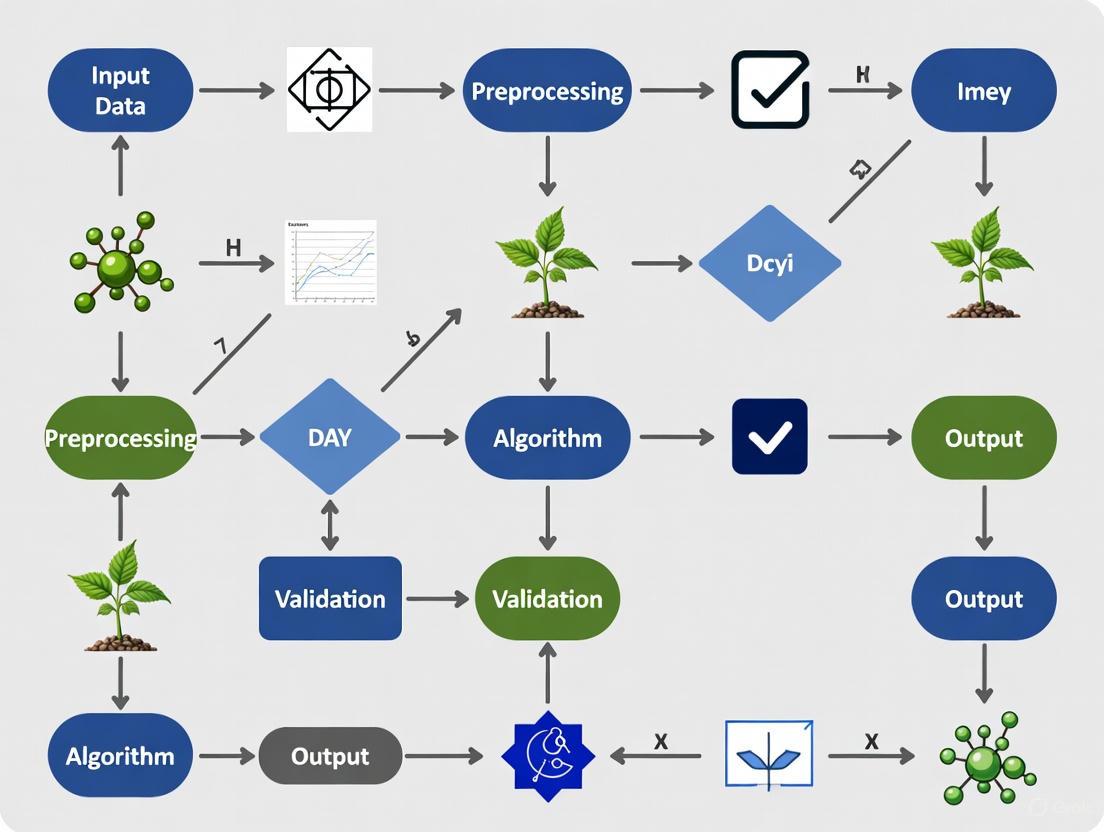

The validation of a new automated phenotyping system or algorithm typically follows a structured experimental protocol. The workflow below generalizes the process for benchmarking a new system against manual measurements.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

Define Target Traits and Plant Cohort: The experiment begins by clearly defining the phenotypic traits to be measured (e.g., leaf area, plant height, biomass) and selecting a plant cohort that captures the expected range of variability for these traits [4] [10].

Apply Manual and Automated Protocols in Parallel: The same set of plants is subjected to both traditional manual measurements and the novel automated system.

- Manual Protocol: This involves measurements using tools like leaf meters, calipers, and rulers. For some traits like biomass, this step is destructive [5] [3].

- Automated Protocol: This involves non-destructively imaging the plants using the system under validation (e.g., 3D laser scanner, multi-view RGB camera system) [4] [5].

Data Processing and Trait Extraction: The raw data from both methods is processed. Manual data is digitized. Automated data is processed through algorithms for tasks like segmentation and skeletonization to extract the same target traits [4] [5].

Statistical Comparison and Validation: The trait values from the automated system are statistically compared against the manual reference data. Key analyses include:

- Correlation Analysis: Calculating Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficients to assess the strength of the linear relationship.

- Error Analysis: Determining metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) or Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) to quantify accuracy.

- Bland-Altman Plots: Assessing the agreement between the two methods and identifying any bias [5].

This rigorous process ensures that automated systems are validated against established standards before deployment in high-throughput breeding pipelines.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Technologies Driving High-Throughput Phenotyping

The breakthrough in overcoming the phenotyping bottleneck is driven by a suite of advanced technologies that enable the non-destructive, high-throughput capture of plant form and function. The table below details the essential "research reagent solutions" in the modern phenotyping toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High-Throughput Phenotyping

| Technology/Solution | Primary Function | Key Applications in Phenotyping |

|---|---|---|

| 3D Laser Scanning (Laser Triangulation) | Captures high-resolution 3D surface geometry by projecting a laser line and triangulating its reflection [5]. | Precisely measuring plant architecture, leaf area, and biomass in controlled environments [5]. |

| Structure-from-Motion (SfM) Photogrammetry | Reconstructs 3D models from multiple overlapping 2D RGB images by finding corresponding points [5]. | Creating 3D models of plants and canopies in field conditions; often deployed on UAVs [5]. |

| Multi-Spectral/Hyperspectral Imaging | Captures reflected light across specific wavelengths, revealing information beyond human vision [7]. | Assessing photosynthetic performance, chlorophyll content, nitrogen status, and early stress detection [1] [7]. |

| Thermal Imaging | Measures surface temperature by detecting infrared radiation [7]. | Monitoring plant water status and detecting drought stress [1]. |

| Standardized Datasets (e.g., TomatoWUR, RiceSEG) | Provide annotated, ground-truthed data for training and validating machine learning algorithms [4] [10]. | Benchmarking and developing novel algorithms for segmentation, skeletonization, and trait extraction [4] [10]. |

| Automated Phenotyping Platforms (e.g., LemnaTec) | Integrated systems that combine imaging sensors, conveyors, and software to automate the entire imaging workflow [7]. | High-throughput screening of thousands of plants in controlled environments for genetic studies and breeding [7]. |

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) is a pivotal addition to this toolkit. Computer vision and deep learning algorithms automate the analysis of the vast image datasets generated, performing tasks like image segmentation, organ classification, and trait prediction with minimal human intervention [7]. This addresses a secondary bottleneck in data analysis and unlocks deeper insights from complex phenotypic data.

The evidence is clear: manual phenotyping methods constitute a critical bottleneck that hinders the pace of crop breeding. Their limitations in throughput, accuracy, and objectivity are being decisively overcome by automated, high-throughput phenotyping technologies. The adoption of standardized benchmarking frameworks, rigorous experimental validation protocols, and an integrated toolkit of imaging sensors and AI-driven analytics is transforming phenotyping from a constraint into a catalyst for discovery.

This digital transformation in phenotyping is fundamental to bridging the long-standing phenotype-genotype gap [2]. By providing rich, high-dimensional phenotypic data that matches the scale and precision of modern genomic data, researchers can more effectively dissect the genetic bases of complex traits. This acceleration is crucial for developing the next generation of high-yielding, resource-efficient, and climate-resilient crops, paving the way for a new Green Revolution capable of meeting the agricultural demands of the future.

Plant phenotyping, the quantitative assessment of plant traits, serves as a crucial bridge between genomics, plant function, and agricultural productivity [11] [12]. As high-throughput, automated phenotyping technologies rapidly evolve, establishing robust validation benchmarks against traditional manual measurements becomes essential for scientific progress and agricultural innovation. These benchmarks ensure that novel algorithms and sensors provide accurate, reliable data for breeding programs and functional ecology studies [4] [13]. This guide objectively compares trait measurements across methodologies, providing researchers with a standardized framework for validating phenotyping algorithms.

Core Plant Traits for Benchmarking

Validation studies typically focus on plant traits that capture key aspects of plant form, function, and ecological strategy. The table below summarizes essential benchmark traits, their biological significance, and common measurement approaches.

Table 1: Key Plant Traits for Phenotyping Validation Studies

| Trait Category | Specific Trait | Biological Significance | Traditional Measurement | Automated/AI-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Architectural Traits | Plant Height | Indicator of ecological strategy, growth, and biomass [13]. | Manual ruler measurement [14]. | 3D point cloud analysis from LiDAR, SfM, or laser triangulation [5] [12]. |

| Leaf Area | Directly related to light interception and photosynthetic capacity. | Destructive harvesting or leaf meters [5]. | Image analysis of 2D projections or 3D surface reconstruction [4] [5]. | |

| Leaf Angle & Length | Influences light capture and canopy structure [14]. | Protractor and ruler. | Skeletonization algorithms connecting keypoints on leaves [14]. | |

| Biochemical & Physiological Traits | Specific Leaf Area (SLA) | Core component of the "leaf economics spectrum," indicating resource use strategy [13]. | Destructive measurement of fresh/dry leaf area and mass. | Predicted from spectral reflectance and environmental data via ensemble modeling [13]. |

| Leaf Nitrogen Concentration (LNC) | Linked to photosynthetic capacity and nutrient status [13]. | Laboratory analysis of destructively sampled leaves (e.g., mass spectrometry). | Predicted from hyperspectral imaging and environmental data [13] [12]. | |

| Structural & Biomechanical Traits | Wood Density | Measure of carbon investment; trade-off between growth and strength [13]. | Archimedes' principle on wood samples. | Not commonly measured via imaging; often inferred or used for model validation. |

| Plant Skeleton & Architecture | Underpins the extraction of other traits like internode length and leaf-stem angles [4]. | Manual annotation from images. | 3D point cloud segmentation and skeletonisation algorithms [4] [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmark Validation

Rigorous validation requires carefully designed experiments that compare novel algorithms against manual, ground-truthed measurements. The following protocols from recent studies provide reproducible methodologies.

Protocol 1: 3D Plant Architecture and Skeletonisation

This protocol is based on the creation and use of the TomatoWUR dataset for evaluating 3D phenotyping algorithms [4].

- Plant Material & Growth: Grow tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum) under controlled conditions until they reach a desired developmental stage.

- 3D Data Acquisition: Place a single plant inside an imaging cabin equipped with multiple cameras (e.g., fifteen cameras) from different angles. Use the shape-from-silhouette method to generate a high-resolution 3D point cloud of the plant.

- Reference ("Manual") Measurements:

- Annotated Point Clouds: Manually label each point in the cloud according to the plant organ it represents (e.g., stem, leaf, petiole).

- Reference Skeletons: Manually trace and digitize the plant's architecture, including main stem and leaf midribs, to create reference skeletons.

- Physical Trait Measurements: Using calipers and rulers, manually measure traits like plant height, internode length, and leaf length. Leaf area can be measured destructively using a leaf area meter.

- Algorithm Testing: Process the 3D point clouds with the phenotyping algorithms to be validated. The output will typically include segmented point clouds, computed skeletons, and extracted trait values.

- Validation & Benchmarking: Quantitatively compare the algorithm's output against the manual reference data. Key performance metrics include segmentation accuracy, skeleton similarity measures, and statistical analysis (e.g., R², root-mean-square error) between manually measured and algorithm-derived traits [4].

Protocol 2: Leaf-Level Phenotyping via Skeletonisation

This protocol validates training-free skeletonisation algorithms for extracting leaf morphology, as demonstrated in studies on orchid and maize plants [14].

- Image Acquisition: Capture high-resolution RGB images of plants (e.g., orchids, maize) from top-down (vertical) and side (front) views using industrial cameras. Ensure a clean, contrasting background.

- Image Pre-processing: Isolate leaf regions from the background using color thresholding and morphological operations.

- Manual Phenotype Measurement: For a subset of leaves, manually measure key phenotypes such as leaf length and leaf angle using image analysis software or physical tools. This serves as the ground truth.

- Algorithmic Skeletonisation: Apply the spontaneous keypoints connection algorithm:

- Keypoint Detection: Within each segmented leaf region, generate random seed points. Do not use predefined keypoints.

- Keypoint Connection: For plants with irregular leaf morphology, use an orientation-guided local search with an adaptive angle-difference threshold to iteratively trace keypoints and form the skeleton. For regular morphologies, fit the skeleton by minimizing curvature.

- Trait Extraction: Calculate phenotypic parameters like leaf length and angle directly from the generated skeleton polylines.

- Validation: Assess the algorithm's performance by calculating the average curvature fitting error and leaf recall rate. Compare the algorithm-derived trait values against the manual measurements to determine accuracy [14].

The logical workflow for validating a phenotyping algorithm, from data collection to final benchmarking, is summarized in the diagram below.

Successful benchmarking relies on high-quality data and standardized software tools. The following table details key resources for plant phenotyping validation studies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Phenotyping Validation

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Validation | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| TomatoWUR Dataset | Annotated Dataset | Provides 3D point clouds, manual annotations, and reference skeletons to quantitatively evaluate segmentation and trait extraction algorithms. [4] | https://github.com/WUR-ABE/TomatoWUR |

| TRY Plant Trait Database | Global Trait Database | Serves as a source of observed trait distributions and global averages to assess the ecological realism of predicted trait values. [15] | http://www.try-db.org |

| PhEval Framework | Benchmarking Software | Provides a standardized framework for the reproducible evaluation of phenotype-driven algorithms, controlling for data and configuration variability. [8] | - |

| Open Top Chambers (OTCs) | Experimental Apparatus | Used in field experiments to simulate climate warming and test trait responses to environmental gradients, providing a real-world validation scenario. [16] | - |

| High-Resolution 3D Sensors | Sensing Equipment | Generate precise geometric data for non-destructive plant architecture measurement, serving as a ground-truthing source or high-quality input for algorithms. [5] | Laser Triangulation, Structure-from-Motion |

The transition from manual to digital plant phenotyping demands robust, standardized validation frameworks. This guide has outlined the key traits—from 3D architectural features like plant height and leaf angle to physiological metrics like SLA—that form the cornerstone of these benchmarks. By adhering to detailed experimental protocols and leveraging communal resources like annotated datasets and benchmarking tools, researchers can ensure their phenotyping algorithms produce accurate, biologically meaningful, and comparable results. This rigor is fundamental for advancing trait-based ecology, accelerating crop improvement, and building a more predictive understanding of plant biology in a changing climate.

In the field of plant sciences, the capacity to generate genomic data has far outpaced the ability to collect high-quality phenotypic data, creating a significant bottleneck in linking genotypes to observable traits. High-throughput phenotyping (HTP) has emerged as a powerful solution to this challenge, offering distinct advantages over traditional manual methods. This guide benchmarks modern phenotyping algorithms and sensor-based platforms against conventional measurements, demonstrating how HTP enables non-destructive, dynamic, and objective data acquisition to accelerate agricultural research and breeding programs.

Core Advantages Over Traditional Methods

→ Non-Destructive Data Acquisition

High-throughput phenotyping facilitates repeated measurements of the same plants throughout their life cycle without causing damage. This non-destructive nature preserves sample integrity for long-term studies and eliminates the need for destructive sampling that can skew experimental results. Technologies such as visible light imaging, hyperspectral imaging, and fluorescence imaging have been successfully applied in evaluating plant growth, biomass, and nutritional status while keeping plants intact for continuous monitoring [17].

→ Dynamic Growth Monitoring

Unlike manual methods limited to snapshots at key growth stages, HTP enables continuous tracking of phenotypic changes. This dynamic observation capability is particularly valuable for capturing time-specific biological events and developmental patterns. Research shows that dynamic phenotyping contributes significantly to genome-wide association studies (GWAS) by helping identify time-specific loci that would be missed with single-time-point measurements [17].

→ Objective and Quantitative Data

Manual phenotyping methods often rely on visual scoring that is subjective and prone to human error and bias. In contrast, HTP provides quantitative, numerically-based trait characterization derived from spectra or images, ensuring standardized and reproducible measurements across different operators, locations, and timepoints [17]. This objectivity is crucial for multi-environment trials and long-term breeding programs.

Comparative Performance Data

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Phenotyping Methods for Key Agronomic Traits

| Trait Category | Specific Trait | Traditional Method | HTP Method | Performance Advantage | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canopy Structure | Canopy Height | Manual ruler measurement | LiDAR scanning | Limits of Agreement: -2.3 to 1.8 cm vs manual: -7.1 to 8.9 cm [18] | Field sorghum trials across multiple growth stages [18] |

| Leaf Area | Leaf Area Index (LAI) | Destructive sampling | LAI-2200 & Lidar | Lower variance: F-test p < 0.01 [18] | Repeated measurements in staggered planting experiments [18] |

| Architecture | 3D Plant Architecture | Manual measurements | 3D point clouds | Enables extraction of complex traits: internode length, leaf angle [4] | TomatoWUR dataset with 44 annotated point clouds [4] |

| Disease Assessment | Disease Severity | Visual scoring | Hyperspectral imaging | Objective quantification, reduces subjectivity [19] | Automated disease severity tracking in grapevine [20] |

| Dynamic Traits | Growth Rate | Limited timepoints | Continuous imaging | Identifies time-specific loci in GWAS [17] | Non-destructive monitoring throughout plant life cycle [17] |

Table 2: Statistical Superiority of HTP in Experimental Studies

| Statistical Metric | Traditional Phenotyping | High-Throughput Phenotyping | Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Points per Day | 10-100 plants [21] | 100s-1000s of plants [21] | Greenhouse and field screening |

| Trait Correlation (r) | Appropriate for method validation | Misleading for method comparison [18] | Statistical framework analysis |

| Variance Comparison | Higher measurement variance | Significantly lower variance, F-test recommended [18] | Canopy height and LAI measurement |

| GWAS Performance | Standard power for large-effect loci | Similar or better performance, detects small-effect loci [17] | Genetic architecture studies |

| Temporal Resolution | Days to weeks | Minutes to hours [17] | Growth dynamic monitoring |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

Protocol 1: Validation of Canopy Height Measurements

- Equipment: LiDAR scanner (e.g., UST-10LX, Hokuyo) vs. manual measuring tape

- Experimental Design: Repeated measurements of the same sorghum plants at multiple growth stages across three years (2018, 2019, 2020) [18]

- Statistical Analysis: Comparison of bias and variances using two-sample t-test for bias and F-test for variance ratio [18]

- Key Consideration: Multiple repeated measurements of the same subject are required for proper variance comparison [18]

Protocol 2: 3D Plant Architecture Phenotyping

- Data Acquisition: 15-camera system to create 3D point clouds using shape-from-silhouette methodology [4]

- Reference Data: Manual measurements of plant height, internode length, and leaf area for validation [4]

- Processing Pipeline: Point cloud segmentation → skeletonization → plant-traits extraction [4]

- Validation Metric: Comparison with manual reference measurements using comprehensive evaluation software [4]

Protocol 3: Automated Leaf Phenotyping

- Imaging System: Industrial cameras (e.g., Daheng MER2-1220-32U3C) for multi-view image acquisition [14]

- Algorithm: Training-free spontaneous keypoint connection for leaf skeletonization [14]

- Performance Metrics: Curvature fitting error (e.g., 0.12 average achieved), leaf recall (e.g., 92% achieved) [14]

- Validation: Comparison with manually annotated datasets for phenotypic parameter accuracy [14]

Research Workflow and Experimental Design

Diagram 1: HTP Benchmarking Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for HTP

| Category | Specific Tool/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging Sensors | RGB Cameras | Morphological trait extraction | Plant architecture, growth monitoring [21] |

| Imaging Sensors | Hyperspectral Imaging | Biochemical parameter estimation | Nitrogen content, disease detection [17] [19] |

| Imaging Sensors | LiDAR/Laser Scanners | 3D structure mapping | Canopy height, biomass estimation [18] |

| Platform Systems | LemnaTec 3D Scanalyzer | Automated plant phenotyping | Controlled environment screening [19] |

| Platform Systems | UAV (Drone) Platforms | Field-scale phenotyping | Large population screening [17] |

| Software Tools | TomatoWUR Evaluation Software | 3D phenotyping algorithm validation | Segmentation and skeletonization assessment [4] |

| Software Tools | Deep Learning Models (CNN) | Image analysis and trait extraction | Automated feature learning [19] |

| Reference Datasets | TomatoWUR Dataset | Algorithm benchmarking | 44 annotated 3D point clouds [4] |

| Statistical Tools | Bias-Variance Testing Framework | Method validation | F-test for variance, t-test for bias [18] |

High-throughput phenotyping represents a paradigm shift in how researchers measure plant traits, addressing critical limitations of traditional methods through non-destructive assessment, dynamic monitoring, and objective data collection. The experimental evidence demonstrates that HTP not only matches but often exceeds the performance of manual measurements, particularly for complex architectural traits and dynamic growth processes. As standardized validation protocols and benchmarking datasets become more widely available, the integration of HTP into routine research workflows will accelerate the discovery of genotype-phenotype relationships and enhance breeding efficiency for improved crop varieties.

The Technological Toolkit: Sensors and Algorithms for High-Throughput Phenotyping

The pursuit of high-throughput and non-destructive analysis in plant phenotyping has driven the adoption of advanced three-dimensional sensing technologies. Accurately benchmarking these automated algorithms against traditional manual measurements is a core challenge in modern agricultural and biological research. Among the most prominent technologies for 3D plant modeling are Laser Triangulation (LT), Structure from Motion (SfM), and Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR). Each technique operates on distinct physical principles, leading to significant differences in data characteristics, accuracy, and suitability for specific experimental conditions. This guide provides an objective comparison of these three sensor technologies, framing their performance within the context of plant phenotyping research that requires validation against manual measurements. The comparison is supported by quantitative experimental data and detailed methodological protocols to assist researchers in selecting the appropriate technology for their specific phenotyping goals.

The three sensing modalities offer different pathways to generating 3D point clouds, each with unique advantages and limitations for capturing plant architecture.

Laser Triangulation (LT) is an active, high-precision method. It projects a laser line onto the plant surface, and a camera, positioned at a known angle to the laser, captures the deformation of this line. Through precise calibration, the 3D geometry of the plant is reconstructed from this deformation [5]. LT systems are renowned for their high resolution, capable of achieving point resolutions of a few microns in controlled laboratory environments [5]. However, a fundamental trade-off exists between the resolution and the measurable volume, requiring careful experimental setup.

Structure from Motion (SfM) is a passive, image-based technique. It uses a series of overlapping 2D images captured from different viewpoints around the plant. Sophisticated algorithms identify common features across these images to simultaneously compute the 3D structure of the plant and the positions of the cameras that captured the images [5] [22]. The resolution of the resulting 3D model is highly dependent on the number of images, the camera's resolution, and the diversity of viewing angles [5]. Its primary advantage is its low cost and accessibility, as it often requires only a standard RGB camera.

LiDAR is an active ranging technology that measures distance by calculating the time delay between an emitted laser pulse and its return after reflecting off the plant surface. By scanning the laser across a scene, it generates a dense point cloud [23]. A key advantage for plant phenotyping is its ability to partially penetrate vegetation, allowing for the measurement of ground elevation under canopy and internal plant structures [23]. It is also largely independent of ambient lighting conditions, making it robust for field applications [23].

Table 1: Fundamental Principles of the Three Sensing Technologies

| Technology | Principle Category | Operating Principle | Key Hardware Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laser Triangulation | Active, Triangulation-based | Projects a laser line and uses a camera at a known angle to measure deformation. | Laser line projector, CCD/PSD camera, precision movement system. |

| Structure from Motion | Passive, Image-based | Computes 3D structure from 2D feature matching across multiple overlapping images. | RGB camera (often consumer-grade), processing software. |

| LiDAR | Active, Time-of-Flight | Measures the time-of-flight of laser pulses to determine distance to a surface. | Laser emitter (e.g., 905 nm wavelength), scanner, receiver [24] [25]. |

The following workflow illustrates the typical data processing pipeline from data acquisition to phenotypic trait extraction, common to all three technologies but with method-specific steps.

Diagram 1: Generalized 3D Plant Phenotyping Workflow

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The choice of sensor technology directly impacts the quality, accuracy, and type of phenotypic data that can be extracted. The following table summarizes key performance metrics as established in recent research.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison for Plant Phenotyping

| Performance Metric | Laser Triangulation | Structure from Motion (SfM) | LiDAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Accuracy | Microns to millimeter resolution [5] | 3-12 cm horizontal, 8-25 cm vertical (with GCPs) [23] | 5-15 cm horizontal, 3-8 cm vertical [23] |

| Typical Environment | Controlled laboratory [5] | Laboratory and field (dependent on lighting) [22] | Field and greenhouse; weather-resistant [23] |

| Vegetation Penetration | Limited | Limited | Excellent (can map ground under canopy) [23] |

| Cost (Hardware) | Low-cost to professional systems [5] | Low (consumer camera) to moderate (RTK systems) [23] | High ($180,000 - $750,000 for drone systems) [23] |

| Data Acquisition Speed | Medium (requires movement) | Fast (image capture), Slow (processing) [22] | Very Fast (millions of points/sec) [23] |

| Key Strengths | Very high resolution for organ-level detail. | Low cost, accessible, rich visual texture (RGB). | Weather independence, vegetation penetration. |

| Key Limitations | Trade-off between resolution and volume. | Struggles with uniform textures (e.g., water, snow). | High equipment cost, lower spatial resolution than LT. |

Recent studies have demonstrated the quantitative performance of these technologies in direct application. For instance, a 2025 study on 3D maize plant reconstruction using SfM-derived point clouds achieved high correlation with manual measurements for key traits, with R² values of 0.99 for stem thickness, 0.94 for leaf length, and 0.87 for leaf width [26]. In a separate application, a terrestrial LiDAR sensor using both distance and reflection measurements successfully discriminated vegetation from soil with an accuracy of up to 95%, showcasing its utility for in-field weed detection [24].

The effect of data quality on analysis is critical. Research on LiDAR point density for Crop Surface Models (CSMs) found that reducing the point cloud to 25% of its original density still maintained a model coverage of >90% and a mean elevation of >96% of the actual measured crop height, indicating a degree of robustness to resolution reduction for certain applications [25].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the reproducibility of phenotyping studies, a clear documentation of the experimental methodology is essential. Below are detailed protocols for data acquisition using each technology.

- System Calibration: Pre-calibrate the system by determining the precise relative position and orientation between the laser projector and the camera. This is typically done using a calibration target with known dimensions.

- Sensor Positioning: Fix the relative position of the laser and camera. Move the sensor system (or the plant) along a pre-defined path to ensure complete coverage of the plant. The movement must be precise to maintain data integrity.

- Data Acquisition: Illuminate the plant with the laser line. The camera captures the deformed laser line profile. The 3D coordinates for each point on the laser line are calculated in real-time via triangulation.

- Point Cloud Generation: Merge the individual laser line profiles from all positions into a single, high-resolution 3D point cloud of the entire plant.

- Apparatus Setup: Configure a system comprising a robotic arm, an industrial RGB camera mounted on the arm, a turntable, and diffuse LED lighting to minimize shadows.

- Image Acquisition Planning: Program the robotic arm to move to multiple positions around the plant, ensuring comprehensive coverage from different height levels and viewing angles. A configuration of three height levels with 40 frames each has been shown to be effective.

- Camera Parameter Optimization: Set camera parameters for optimal plant capture. An exposure time of 50 milliseconds and a camera-to-object distance of 16 centimeters are examples of optimized parameters.

- Image Capture: At each position, the turntable rotates the plant, and the camera captures multiple images. This process results in hundreds of overlapping images.

- 3D Reconstruction: Process the image set using SfM-MVS software (e.g., Metashape, RealityCapture). The SfM algorithm solves for camera positions and a sparse point cloud, which the MVS algorithm then densifies into a detailed 3D model.

- Sensor Configuration: Mount a terrestrial LiDAR sensor (e.g., SICK LMS-111) on a tripod, pointing vertically downwards to scan a vertical plane across the crop inter-row area. Set the angular resolution to 0.25°.

- Data Collection: Scan the field, recording both the distance (range) and the intensity (reflectivity) of the return signal for each laser pulse.

- Ground Truthing: Immediately after LiDAR scanning, take digital photographs of the sampled area and perform manual measurements of plant heights for validation.

- Data Analysis: Use the two-index approach (height from distance measurements and reflectance value) in a binary logistic regression model to classify points as either vegetation or soil.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key hardware and software solutions used in experiments with the featured sensor technologies.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Software for 3D Plant Phenotyping

| Item Name | Function / Application | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Robotic Arm & Turntable | Provides precise, automated multi-view image acquisition for SfM in controlled environments. | Ensuring comprehensive coverage for high-fidelity 3D reconstruction of single plants [22]. |

| RTK-GNSS Drone Module | Provides centimeter-level positioning accuracy for georeferencing aerial data without Ground Control Points. | Enabling high-precision plant height measurement from drones [27]. |

| SfM-MVS Software | Processes overlapping 2D images to generate 3D models. (e.g., Metashape, Pix4D, RealityCapture). | Standard software for creating 3D point clouds and meshes from drone or ground-based images [23] [22]. |

| Semantic Segmentation Models | Deep learning models for automatically segmenting plant point clouds into organs (stem, leaf, etc.). | Automated trait extraction; e.g., DANet for fruit segmentation, PointSegNet for stem-leaf segmentation [26] [28]. |

| Low-Cost LiDAR Sensor (e.g., SICK LMS-111) | Terrestrial 2D/3D scanning for proximal sensing applications in agriculture. | Weed detection and crop row monitoring in field conditions [24]. |

Laser Triangulation, Structure from Motion, and LiDAR each present a compelling set of characteristics for 3D plant modeling. The choice of technology is not a matter of identifying a universal best, but rather of matching the sensor's capabilities to the specific research question. Laser Triangulation is unparalleled for high-resolution organ-level phenotyping in the lab. Structure from Motion offers an accessible and cost-effective solution for a wide range of applications, particularly where visual texture is important. LiDAR is the robust technology of choice for field-based studies where vegetation penetration, weather independence, and speed are critical. As the field advances, the fusion of these technologies with machine learning for automated trait extraction is set to further revolutionize plant phenotyping, enabling more accurate and high-throughput benchmarking against manual measurements.

Plant phenotyping, the quantitative assessment of plant traits, is a cornerstone of crop breeding programs aimed at enhancing yield and stress resistance [29] [30]. Traditional manual methods, however, are labor-intensive, time-consuming, and prone to human error, creating a significant bottleneck for accelerating crop improvement [31]. Image-based plant phenotyping has emerged as a transformative solution, leveraging imaging technologies and analysis tools to measure plant traits in a non-destructive, high-throughput manner [29].

Deep learning has profoundly impacted this field, with most implementations following the supervised learning paradigm. These methods require large, annotated datasets, which are expensive and time-consuming to produce [29] [31]. To circumvent this limitation, self-supervised learning (SSL) methods, particularly contrastive learning, have arisen as promising alternatives. These paradigms learn meaningful feature representations from unlabeled data by generating a supervisory signal from the data itself, reducing the dependency on manual annotations [29] [32].

This guide provides an objective comparison of these deep learning paradigms within the context of benchmarking plant phenotyping algorithms, drawing on recent experimental studies to evaluate their performance, data efficiency, and applicability.

Core Concepts of Deep Learning Paradigms

Supervised Learning

In a typical supervised learning workflow for plant phenotyping, a deep neural network (e.g., a Convolutional Neural Network or CNN) is trained on a large dataset of images, such as PlantVillage or MinneApple, where each image is associated with a label (e.g., disease type, bounding box for plant detection) [32]. The model learns by adjusting its parameters to minimize the difference between its predictions and the ground-truth labels. Transfer learning, which involves initializing a model with weights pre-trained on a large general-domain dataset like ImageNet, is a popular and effective strategy to boost performance, especially when the labeled data for the specific plant task is limited [29] [32].

Self-Supervised & Contrastive Learning

Self-supervised learning is a representation learning approach that overcomes the need for manually annotated labels by defining a pretext task that generates pseudo-labels directly from the data's structure [29] [32]. A common and powerful type of SSL is contrastive learning.

The core idea of contrastive learning is to learn representations by pulling "positive" samples closer together in an embedding space while pushing "negative" samples apart. In computer vision, positive pairs are typically created by applying different random augmentations (e.g., cropping, color jittering) to the same image, while negatives are different images from the dataset [29] [32]. The model, often called an encoder, learns to be invariant to these augmentations, thereby capturing semantically meaningful features. After this pre-training phase on unlabeled data, the learned representations can be transferred to various downstream tasks (e.g., classification, detection) by fine-tuning the model with a small amount of labeled data.

Frameworks like SimCLR and MoCo (Momentum Contrast) have proven highly effective for learning global image-level features [29] [32]. For dense prediction tasks like object detection and semantic segmentation, which require spatial information, Dense Contrastive Learning (DenseCL) has been developed to exploit local features at the pixel level [29].

Benchmarking Performance: A Quantitative Comparison

A comprehensive benchmarking study by researchers at the University of Saskatchewan directly compared supervised and self-supervised contrastive learning methods for image-based plant phenotyping [29] [30] [31]. The study evaluated two SSL methods—MoCo v2 and DenseCL—against conventional supervised pre-training on four downstream tasks.

Table 1: Benchmarking Results on Downstream Plant Phenotyping Tasks (Based on [29])

| Pretraining Method | Wheat Head Detection | Plant Instance Detection | Wheat Spikelet Counting | Leaf Counting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Pre-training | Best Performance | Best Performance | Best Performance | Not Best Performance |

| Self-Supervised: MoCo v2 | Lower Performance | Lower Performance | Lower Performance | Intermediate Performance |

| Self-Supervised: DenseCL | Lower Performance | Lower Performance | Lower Performance | Best Performance |

Table 2: Key Findings on Data Dependency and Representation Similarity (Based on [29] [30])

| Aspect | Supervised Learning | Self-Supervised Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Performance with Large Labeled Data | Generally superior | Often lower |

| Data Efficiency | Lower (requires large labels) | Higher (uses unlabeled data) |

| Sensitivity to Dataset Redundancy | Less sensitive | More sensitive |

| Representation Similarity | Learns distinct high-level features in final layers | MoCo v2 and DenseCL learn similar internal representations across layers |

Key Findings from Benchmarking

- Supervised pre-training generally outperformed self-supervised methods on tasks like wheat head detection, plant instance detection, and wheat spikelet counting. This suggests that when large, annotated datasets are available, supervised learning remains a robust choice [29] [31].

- SSL shows competitive and sometimes superior performance on specific tasks, such as leaf counting, where DenseCL achieved the best result. This indicates that dense SSL methods may be particularly suited for tasks requiring fine-grained spatial understanding [29].

- Domain-specific pre-training maximizes performance. The study found that using a diverse pretraining dataset from the same or a similar domain as the target task (e.g., using crop images to phenotype crops) consistently led to the best downstream performance across all methods [29] [32].

- SSL is more sensitive to redundancy in the pretraining dataset. Imaging platforms like drones often capture images with substantial spatial overlap. The study concluded that SSL methods suffer more from this redundancy than supervised methods, highlighting a critical consideration when building pretraining datasets [29] [31].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for researchers, this section outlines the key methodologies from the cited benchmarking experiments.

Protocol 1: Benchmarking SSL vs. Supervised Learning

This protocol is derived from the large-scale study conducted by Ogidi et al. (2023) [29] [31].

- Pretraining Datasets: Four source domains were used to study the effect of domain specificity:

- ImageNet (general objects)

- iNaturalist 2021 (natural organisms)

- iNaturalist Plants subset (general plants)

- TerraByte Field Crop (TFC) dataset (domain-specific crops)

- Model Pre-training:

- Supervised: Models were pre-trained on the above datasets using standard cross-entropy loss with human-annotated labels.

- Self-Supervised (MoCo v2): Models were pre-trained using the momentum contrast framework to learn global image-level representations.

- Self-Supervised (DenseCL): Models were pre-trained with a dense contrastive loss to learn local, pixel-level features beneficial for detection and segmentation.

- Downstream Task Fine-tuning: The pre-trained models were transferred to four downstream tasks:

- Wheat head detection

- Plant instance detection

- Wheat spikelet counting

- Leaf counting Fine-tuning was performed on the target task datasets using standard supervised loss functions relevant to each task (e.g., regression loss for counting).

- Evaluation: Model performance was evaluated on held-out test sets for each downstream task using task-specific metrics, such as mean Average Precision (mAP) for detection tasks and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for counting tasks.

Protocol 2: Two-Stage 3D Organ Segmentation

A study by Li et al. (2025) presented a two-stage deep learning method for 3D plant organ segmentation, demonstrating a specialized application [33].

- Data Acquisition and Labeling: 3D point clouds of sugarcane, maize, and tomato plants were captured using sensors like LiDAR. The point clouds were labeled with two classes: stems and leaves.

- Stage 1 - Stem-Leaf Semantic Segmentation:

- The PointNeXt deep learning framework was used for point cloud processing.

- The model was trained with cross-entropy loss with label smoothing and the AdamW optimizer.

- Hyperparameters like MLP channel size and the number of InvResMLP blocks were systematically optimized.

- Stage 2 - Leaf Instance Segmentation:

- The Quickshift++ clustering algorithm was applied to the semantic segmentation outputs to distinguish and identify individual leaf instances.

- Evaluation: Performance was measured using Overall Accuracy, mean Intersection over Union (mIoU), F1 score, precision, and recall, comparing against other state-of-the-art networks like ASIS and JSNet.

Visualization of Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows and logical relationships of the deep learning paradigms discussed.

Diagram 1: Self-Supervised Contrastive Learning Workflow

Diagram 2: Relationship Between Learning Paradigms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Resources for Deep Learning in Plant Phenotyping

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Throughput Imaging Platform | Captures plant images over time; can include RGB, multispectral, or 3D LiDAR sensors. | Generating large-scale, unlabeled datasets for SSL pre-training [29] [33]. |

| Domain-Specific Datasets | Unlabeled or labeled image collections from the plant domain (e.g., crops, leaves). | Used for within-domain pre-training or fine-tuning to maximize model performance [29] [32]. |

| Pre-trained Model Weights | Model parameters already trained on large datasets (e.g., ImageNet, or domain-specific SSL models). | Serves as a starting point for transfer learning, reducing training time and data requirements [29] [32]. |

| Annotation Software | Tools for manually labeling images with bounding boxes, segmentation masks, or counts. | Creating ground-truth data for supervised fine-tuning and evaluation of downstream tasks [29]. |

| Deep Learning Framework | Software libraries like PyTorch or TensorFlow. | Provides the building blocks for implementing and training custom deep learning models [33] [34]. |

| Computational Resources (GPU) | Graphics Processing Units for accelerated model training. | Essential for handling the high computational load of training deep neural networks on large image sets [33]. |

Plant phenotyping, the quantitative assessment of plant traits, is fundamental for advancing plant science and breeding programs. Traditional manual methods are often subjective, labor-intensive, and incapable of capturing complex geometric phenotypes, creating a significant bottleneck in agricultural research [17]. Image-based high-throughput phenotyping has emerged as a powerful alternative, with plant organ skeletonization—the process of reducing a leaf or stem to its medial axis or skeleton—playing a pivotal role in extracting precise geometric traits such as length, curvature, and angular relationships [35].

While deep learning has become a dominant force in this area, these methods typically require extensive manually annotated datasets and substantial computational resources for training, which limits their scalability and accessibility [35] [31]. This guide objectively compares a novel class of model-free, training-free skeletonization algorithms against established manual and deep learning-based methods, framing the evaluation within the broader context of benchmarking plant phenotyping algorithms. We focus on a recently developed spontaneous keypoints connection algorithm that eliminates the need for predefined keypoints, manual labels, and model training, offering a promising alternative for rapid, annotation-scarce phenotyping workflows [35] [14].

Performance Benchmarking: Training-Free vs. Alternative Approaches

To quantitatively evaluate the efficacy of training-free skeletonization, the table below summarizes its performance against manual measurements and supervised deep learning methods based on published experimental results.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Plant Phenotyping Methods

| Method Category | Example Algorithm/System | Key Performance Metrics | Reported Advantages | Reported Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manual Measurement | N/A (Traditional ruler-based) | N/A (Time-consuming, subjective) | Direct measurement, no specialized equipment needed [26] | Labor-intensive; subjective; prone to error; difficult for complex traits [26] [17] |

| Supervised Deep Learning | YOLOv7-pose, AngleNet, PointSegNet | PointSegNet: 93.73% mIoU, 97.25% Precision [26]; High accuracy for specific tasks like ear phenotyping [31] | High accuracy and automation for trained tasks [26] [31] | Requires large annotated datasets; computationally intensive training; limited flexibility for new keypoints [35] [31] |

| Self-Supervised Learning | MoCo v2, DenseCL | Generally outperformed by supervised pre-training on most tasks except leaf counting [36] | Reduces need for labeled data [31] [36] | Performance sensitive to dataset redundancy; may learn different representations than supervised methods [31] [36] |

| Training-Free Skeletonization | Spontaneous Keypoints Connection Algorithm | Avg. leaf recall: 92%; Avg. curvature fitting error: 0.12 on orchid datasets [35] [14] | No training or labels needed; robust to leaf count variability and occlusion; suitable for high-throughput workflows [35] [14] | Performance may depend on initial segmentation quality; less explored for 3D point clouds |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

Robust benchmarking requires standardized protocols and datasets. Below, we detail the experimental methodologies used to validate the training-free skeletonization approach and the datasets employed for evaluation.

The Training-Free Skeletonization Workflow

The spontaneous keypoints connection algorithm operates through a structured, multi-stage process. The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from image acquisition to final phenotype extraction.

The algorithm begins with image acquisition using industrial cameras from multiple views (e.g., vertical and front-view) to capture diverse leaf morphologies [14]. The next step is leaf region isolation, typically achieved through color thresholding and morphological operations to create distinct masks for each leaf [14].

The core of the method involves random seed-point generation within the isolated leaf regions, followed by an adaptive keypoint connection process. This connection is not random; it uses one of two distinct strategies based on the perceived leaf morphology [35] [14]:

- For plants with random leaf morphology (e.g., top-view orchids), the algorithm employs an orientation-guided local search. It uses a threshold for the angle difference among any three consecutive points and iteratively identifies keypoints within circular search neighborhoods, halving the search space at each step to trace the skeleton.

- For plants with regular leaf morphology (e.g., front-view orchids), the algorithm fits the skeleton trajectory by minimizing curvature, constrained by convexity rules to produce a smooth, midrib-consistent polyline.

The output is a set of connected keypoints forming the leaf skeleton, from which geometric phenotypic parameters like length, angle, and curvature are directly calculated [35].

Benchmarking Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

The development of public, annotated datasets has been crucial for objective benchmarking. Key datasets used in this field include:

- Orchid Datasets: Comprising vertical and front-view images of Cymbidium goeringii, used to validate the algorithm on both random and regular leaf morphologies. Performance is measured by leaf recall (92%) and curvature fitting error (0.12) [35] [14].

- TomatoWUR: A comprehensive 3D point cloud dataset of tomato plants, including annotated point clouds, skeletons, and manual reference measurements. It enables quantitative evaluation of segmentation, skeletonisation, and trait extraction algorithms [4].

- Maize Datasets: Publicly available images of individual maize plants used to test the cross-species generalization ability of the spontaneous keypoints algorithm [14].

The transition from 2D images to 3D point clouds represents a significant advancement. While the spontaneous keypoints algorithm was validated on 2D images, other studies highlight the importance of 3D data. For instance, PointSegNet, a lightweight deep learning network, was benchmarked on 3D maize point clouds reconstructed using Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF), achieving a high mIoU of 93.73% for stem and leaf segmentation [26]. This underscores that the choice between 2D and 3D phenotyping—and between training-free and learning-based methods—depends on the required trait complexity and available resources.

Successful implementation and benchmarking of plant phenotyping algorithms rely on a suite of computational and material resources. The following table details key components of the experimental pipeline.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Plant Phenotyping

| Category | Item | Specification / Example | Function in the Pipeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging Hardware | Industrial Cameras | Daheng MER2-1220-32U3C (4024×3036), Hikvision MV-CU060-10GC (3072×2048) [14] | High-resolution image acquisition for 2D phenotyping. |

| 3D Reconstruction | Smartphone / NeRF (Nerfacto) | Consumer-grade smartphones for video capture; Nerfacto for 3D model generation [26] | Cost-effective 3D point cloud generation from multi-view images. |

| Annotation Software | Manual Labeling Tools | Varies by lab (e.g., custom scripts, ImageJ) [37] | Creating ground truth data for training and evaluating supervised algorithms. |

| Reference Datasets | TomatoWUR, Orchid, Maize Datasets | 44 point clouds of tomato plants; multi-view orchid images; maize plant images [4] [14] | Providing standardized data for algorithm development, testing, and benchmarking. |

| Computing Environment | Cloud Computing / Local GPU | OpenPheno's cloud infrastructure; local GPU servers for model training [37] | Executing computationally intensive image analysis and deep learning models. |

| Phenotyping Platforms | OpenPheno | A WeChat Mini-Program offering cloud-based, specific phenotyping tools like LeafAnglePheno [37] | Democratizing access to advanced phenotyping algorithms without local hardware constraints. |

The benchmarking data and experimental protocols presented in this guide demonstrate that training-free, model-free skeletonization approaches represent a viable and efficient alternative to both manual measurements and supervised deep learning models for specific plant phenotyping applications. The spontaneous keypoints connection algorithm, with its 92% leaf recall and absence of training requirements, is particularly suited for high-throughput scenarios where labeled data is scarce, computational resources are limited, or rapid cross-species deployment is necessary [35] [14].

However, the choice of phenotyping tool is not one-size-fits-all. For applications demanding the highest possible accuracy in complex 3D organ segmentation, deep learning models like PointSegNet (achieving 93.73% mIoU) currently hold an advantage, albeit at a higher computational and data annotation cost [26]. The emergence of platforms like OpenPheno, which leverages cloud computing to make various phenotyping tools accessible via smartphone, is a significant step toward democratizing these technologies [37]. Ultimately, the selection of a skeletonization method should be guided by a clear trade-off between the required precision, available resources, and the specific geometric traits of interest, with training-free methods offering a compelling solution for a well-defined subset of plant phenotyping challenges.

The gap between genomic data and expressed physical traits, known as the phenotyping bottleneck, has long constrained progress in plant breeding and agricultural research [38]. While high-throughput DNA sequencing technologies have advanced rapidly, the capacity to generate high-quality phenotypic data has lagged far behind, largely due to reliance on manual measurements that are laborious, time-consuming, and subjective [17]. Traditional methods for assessing critical agronomic traits like leaf area, plant height, and biomass typically require destructive harvesting, making longitudinal studies of plant development impractical at scale [39] [40]. This limitation has driven the development of automated, image-based phenotyping platforms that can non-destructively measure plant traits throughout the growth cycle [19].

Modern phenotyping approaches leverage advanced sensing technologies and computer vision algorithms to transform pixel data into quantifiable traits [38]. These systems range from laboratory-based imaging setups to unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and ground-based platforms that can capture 2D, 3D, and spectral information of plants in various environments [41] [39]. The core challenge lies not only in acquiring plant images but in accurately processing this data to extract biologically meaningful information that correlates strongly with manual measurements [5]. This review benchmarks the performance of current automated phenotyping pipelines against established manual methods, providing researchers with a comparative analysis of their accuracy, throughput, and applicability across different experimental contexts.

Comparative Analysis of Phenotyping Technologies

Automated plant phenotyping technologies can be broadly categorized based on their underlying sensing principles, platform types, and the traits they measure. The following table summarizes the main approaches currently employed in research settings.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Plant Phenotyping Technologies

| Technology | Measured Traits | Accuracy/Performance | Throughput | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laser Triangulation (LT) | Plant height, leaf area, biomass, 3D architecture [5] | Sub-millimeter resolution possible [5] | Laboratory to single plant scale [5] | Limited measurement volume; trade-off between resolution and volume [5] |

| Structure from Motion (SfM) | Canopy height, ground cover, biomass [41] | Strong correlation with manual height (R² = 0.99) [41] | Miniplot to field scale (UAV platforms) [41] | Dependent on lighting conditions and image overlap [5] |

| LiDAR | Canopy height, ground cover, above-ground biomass [39] | High correlation with biomass (R² = 0.92-0.93) [39] | Experimental field scale [39] | Higher cost; complex data processing [39] |

| Structured Light (SL) | Organ-level morphology, leaf area [5] | High resolution and accuracy [5] | Single plant scale [5] | Sensitive to ambient light; limited to controlled environments [5] |

| Multispectral Imaging (UAV) | Leaf Area Index (LAI), biomass, plant health [42] | Good correlation with LAI (R² = 0.67) [41] | High (field scale) [42] | Requires radiometric calibration [42] |

| 3D Mesh Processing | Leaf width, length, stem height [40] | Correlation coefficients: 0.88-0.96 with manual measurements [40] | Single plant scale [40] | Computationally intensive; requires multiple viewpoints [40] |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

UAV-Based Phenotyping for Plant Height and Leaf Area Index

Protocol Overview: The unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) methodology employs either nadir (vertical) or oblique (angled) photography to capture high-resolution images of field plots [41]. A typical experimental setup involves a flight planning software such as Mission Planner, a UAV (e.g., DJI Inspires 2), and high-resolution RGB or multispectral cameras [41] [42].

Detailed Workflow:

- Flight Planning: Establish flight paths with high image overlap (typically >80%) and determine appropriate altitude based on desired ground resolution [41] [42].

- Ground Control: Place ground control points (GCPs) with known coordinates throughout the field using RTK GPS for accurate georeferencing [41].

- Image Acquisition: Capture images at regular intervals throughout the growing season, maintaining consistent lighting conditions when possible [41].

- 3D Reconstruction: Process images using software such as Agisoft Metashape to generate point clouds, digital surface models (DSM), and orthomosaic maps [41].

- Trait Extraction: Calculate plant height by subtracting digital terrain model (DTM) from DSM, and derive Leaf Area Index (LAI) using 3D voxel methods or spectral indices [41].

Performance Validation: A study on maize demonstrated strong agreement between UAV-derived plant height and manual measurements across the growing season [41]. For LAI estimation, oblique photography (slope = 0.87, R² = 0.67) outperformed nadir photography (slope = 0.74, R² = 0.56) when compared to destructive manual measurements [41].

LiDAR-Based Above-Ground Biomass Estimation

Protocol Overview: Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) systems mounted on ground-based platforms like the Phenomobile Lite provide detailed 3D information of plant canopies [39]. This method is particularly valuable for biomass estimation as it directly measures plant structure rather than relying on proxies.

Detailed Workflow:

- System Configuration: Mount LiDAR sensors on a mobile platform at a height suitable for capturing complete canopy information [39].

- Data Collection: Conduct multiple passes over experimental plots, ensuring complete coverage while maintaining consistent speed and trajectory [39].

- Point Cloud Processing: Filter noise and align multiple scans to create a comprehensive 3D representation of the canopy [39].

- Trait Extraction: Calculate biomass using either the 3D voxel index (3DVI) or 3D profile index (3DPI) methods, which quantify plant volume from point cloud data [39].

Performance Validation: In wheat trials, LiDAR-derived biomass estimates showed strong correlation with destructive measurements across eight developmental stages (3DPI: r² = 0.93; 3DVI: r² = 0.92) [39]. The system also accurately measured canopy height (r² = 0.99, RMSE = 0.017 m) and ground cover, demonstrating particular advantage over NDVI at high ground cover levels where spectral indices typically saturate [39].

3D Mesh Processing for Organ-Level Phenotyping

Protocol Overview: For detailed organ-level measurements, 3D mesh processing techniques reconstruct complete plant models from multiple images taken from different viewpoints [40]. This approach enables non-destructive measurement of individual leaves and stems.

Detailed Workflow:

- Multi-View Image Acquisition: Capture images of plants from multiple angles (e.g., 64 images at 5.6° intervals) using a controlled setup with rotating platform [40].

- 3D Reconstruction: Generate 3D mesh models using software such as 3DSOM or Phenomenal [40] [43].

- Mesh Segmentation: Apply algorithms to partition the mesh into morphological regions corresponding to individual organs [40].

- Trait Extraction: Calculate organ-specific traits including leaf length, width, area, and stem height from the segmented mesh [40].

- Temporal Tracking: Implement algorithms such as PhenoTrack3D to track individual organs over time using sequence alignment approaches [43].

Performance Validation: In cotton plants, 3D mesh-based measurements showed mean absolute errors of 9.34% for stem height, 5.75% for leaf width, and 8.78% for leaf length when compared to manual measurements [40]. Correlation coefficients ranged from 0.88 to 0.96 across these traits [40]. For temporal organ tracking in maize, PhenoTrack3D achieved 97.7% accuracy for ligulated leaves and 85.3% for growing leaves when assigning correct rank positions [43].

Workflow Visualization of Automated Phenotyping Pipelines

Generalized High-Throughput Phenotyping Workflow

Generalized High-Throughput Phenotyping Workflow

Organ-Level Temporal Tracking Pipeline

Organ-Level Temporal Tracking Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Equipment for Automated Phenotyping

| Item | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Agisoft Metashape | Generate 3D point clouds, orthomosaic maps, and digital surface models from UAV imagery [41] | Plant height estimation, canopy structure analysis [41] |

| Phenomenal Pipeline | 3D plant reconstruction and organ segmentation from multi-view images [43] | Organ-level trait extraction in maize and sorghum [43] |

| Deep Plant Phenomics | Deep learning platform for complex phenotyping tasks (leaf counting, mutant classification) [38] | Rosette analysis in Arabidopsis, disease detection [38] |

| Ground Control Points (GCPs) | Geo-referencing and accuracy validation of aerial imagery [41] [42] | Spatial alignment of UAV-captured field imagery [41] |

| Multispectral Sensors (e.g., Airphen) | Capture reflectance data across multiple spectral bands [42] | Vegetation indices calculation, stress detection [42] |

| LiDAR Sensors | Active 3D scanning of plant canopies [39] | Biomass estimation, canopy height measurement [39] |

| Radiometric Calibration Panels | Convert digital numbers to reflectance values [42] | Standardization of multispectral imagery across dates [42] |

| KAT4IA Pipeline | Self-supervised plant segmentation for field images [44] | Automated plant height estimation without manual labeling [44] |

The comprehensive comparison of automated phenotyping technologies against traditional manual methods reveals a consistent pattern: well-designed automated pipelines can match or exceed the accuracy of manual measurements while providing substantially higher throughput and temporal resolution [17] [39]. For key agronomic traits, the correlation between automated and manual measurements is consistently strong, with R² values typically exceeding 0.85-0.90 for well-established traits like plant height and biomass [39] [40].

The choice of appropriate phenotyping technology depends heavily on the experimental context and target traits. For field-scale high-throughput screening, UAV-based platforms with RGB or multispectral sensors offer the best balance of coverage and resolution [41] [42]. For detailed organ-level studies in controlled environments, 3D mesh processing pipelines provide unprecedented resolution for tracking individual leaf growth over time [43] [40]. Ground-based LiDAR systems excel at accurate biomass estimation without destructive harvesting [39].

As these technologies continue to mature, the integration of machine learning and computer vision approaches is steadily overcoming earlier limitations related to complex field conditions and occluded plant organs [44] [38]. The emerging capability to automatically track individual organs throughout development represents a significant advance toward closing the genotype-to-phenotype gap [43]. These developments in high-throughput phenotyping are poised to accelerate plant breeding programs and enhance our understanding of gene function and environmental responses in crops.

Navigating Pitfalls: Key Challenges in Optimizing Phenotyping Algorithms

The adoption of self-supervised learning (SSL) is transforming high-throughput plant phenotyping, offering a powerful solution to one of the field's most significant bottlenecks: the dependency on large, expensively annotated datasets. SSL enables models to learn directly from unlabeled data, making it particularly valuable for extracting meaningful information from the complex 3D point clouds used in modern plant analysis. However, the performance of these SSL models exhibits a critical dependency on dataset quality, with data redundancy emerging as a pivotal factor influencing model efficiency, generalizability, and ultimate success in phenotyping tasks. Within plant phenotyping, redundancy can manifest as repetitive geometric structures in plant architecture, oversampled temporal sequences of plant growth, or highly similar specimens within a breeding population. This review objectively compares the performance of emerging SSL approaches against traditional and supervised alternatives, examining their sensitivity to data redundancy within the specific context of benchmarking plant phenotyping algorithms against manual measurements.

Technical Background

Self-Supervised Learning in Plant Phenotyping

Self-supervised learning is a machine learning paradigm that allows models to learn effective data representations without manual annotation by creating pretext tasks from the structure of the data itself [45] [46]. For plant phenotyping, this typically involves using unlabeled plant imagery or 3D point clouds to generate supervisory signals, such as predicting missing parts of an image or identifying different views of the same plant [46]. The core advantage of SSL is its ability to leverage vast amounts of readily available unlabeled data, thus bypassing the annotation bottleneck that often constrains supervised approaches [4].

The application of SSL is particularly relevant for 3D plant phenotyping, where annotating point clouds for complex traits like plant architecture, internode length, and leaf area is notoriously time-intensive and requires specialized expertise [4]. For instance, the TomatoWUR dataset, which includes annotated 3D point clouds of tomato plants, was developed to address the critical shortage of comprehensively labeled data for evaluating 3D phenotyping algorithms, highlighting the resource constraints that SSL seeks to overcome [4].

The Problem of Data Redundancy

Data redundancy refers to the presence of excessive shared or repeated information within a dataset that fails to contribute meaningful new knowledge for model training [47] [48]. In the context of plant phenotyping, this could involve:

- Spatial Redundancy: Multiple images or point clouds of the same plant from nearly identical viewpoints

- Temporal Redundancy: Sequential growth images with minimal phenotypic change between time points

- Genetic Redundancy: Images of highly similar plant varieties or genetically identical specimens under similar conditions

High redundancy negatively impacts model training by reducing feature diversity, potentially causing models to overfit to common but uninformative patterns and perform poorly on new, diverse data [48]. As one illustrative example, if training a classifier to distinguish between cats and dogs, 100 pictures of the same dog (high redundancy) contribute less useful information than 100 pictures of different dogs (low redundancy) [47]. This principle directly applies to plant phenotyping, where diversity of specimens, growth conditions, and imaging angles is crucial for developing robust models.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Performance Metrics for Plant Phenotyping Algorithms

The evaluation of plant phenotyping algorithms, particularly those employing SSL, relies on standardized metrics that quantify their accuracy in extracting biological traits. The following table summarizes key performance indicators reported across multiple studies:

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics in Plant Phenotyping Studies

| Algorithm/Dataset | Task | Primary Metric | Reported Performance | Benchmark Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant-MAE [46] | 3D Organ Segmentation | Mean IoU (%) | >80% (Tomato, Cabbage) | Surpassed PointNet++, Point Transformer |

| Plant-MAE [46] | 3D Organ Segmentation | Precision/Recall/F1 | >80% across all metrics | Exceeded baseline Point-M2AE |

| Spontaneous Keypoints Connection [14] | Leaf Skeletonization | Leaf Recall Rate (%) | 92% (Orchid dataset) | Training-free, no manual labels |

| Spontaneous Keypoints Connection [14] | Curvature Fitting | Average Error | 0.12 (Orchid dataset) | Geometry-accurate phenotype extraction |

| SSL for Cell Segmentation [49] | Biomedical Segmentation | F1 Score | 0.771-0.888 | Matched or outperformed Cellpose (0.454-0.882) |

Performance benchmarks against manual measurements remain crucial for validation. For instance, the spontaneous keypoints connection algorithm achieved a 92% leaf recall rate on orchid images while enabling precise calculation of geometric phenotypes without manual intervention [14]. Similarly, comprehensive datasets like TomatoWUR include manual reference measurements specifically to validate and benchmark automated 3D phenotyping algorithms, ensuring their biological relevance [4].

SSL Approaches to Redundancy Reduction

Different SSL frameworks employ distinct strategies to mitigate the effects of data redundancy, with significant implications for their performance in plant phenotyping applications:

Table 2: SSL Approaches to Redundancy Reduction in Phenotyping

| SSL Method | Core Mechanism | Redundancy Handling | Demonstrated Advantages | Limitations/Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant-MAE [46] | Masked Autoencoding | Reconstruction of masked portions of plant point clouds | State-of-the-art segmentation across multiple crops/environments | Lower recall for rare organs (e.g., tassels) due to class imbalance |