Agrobacterium-Mediated CRISPR Transformation: A Revolutionary Toolkit for Plant Biotechnology and Crop Improvement

This article comprehensively explores the fusion of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation with CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, a powerful combination revolutionizing plant genetic engineering.

Agrobacterium-Mediated CRISPR Transformation: A Revolutionary Toolkit for Plant Biotechnology and Crop Improvement

Abstract

This article comprehensively explores the fusion of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation with CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, a powerful combination revolutionizing plant genetic engineering. Aimed at researchers and biotechnologists, we detail the foundational biology of Agrobacterium, present step-by-step methodological protocols for diverse plant species, and address key challenges in optimizing efficiency. The content provides a comparative analysis with other delivery methods, highlights validation techniques for confirming edits, and discusses the significant implications of this technology for developing resilient, high-yielding crops to address global food security challenges.

The Biological Synergy: Unraveling the Agrobacterium and CRISPR Partnership

Agrobacterium tumefaciens is a soil-borne phytopathogen that causes crown gall disease in plants through the transfer of a segment of its tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid, known as T-DNA, into the host plant genome [1]. This natural genetic engineering capability has been harnessed by scientists, who disarmed the pathogenic genes to create a versatile vector system for plant genetic transformation [1]. The engineered A. tumefaciens now serves as a fundamental tool for introducing foreign genes into plants, enabling advancements in crop improvement, functional genomics, and synthetic biology [1]. This Application Note details recent methodological advances and protocols that leverage A. tumefaciens for stable transformation and CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing across diverse plant species.

Application Notes: Methodological Advances and Comparative Analysis

Recent research has significantly expanded the capabilities of A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation, particularly for challenging species and applications. The table below summarizes key advances in transformation protocols for various plant species.

Table 1: Recent Advances in Agrobacterium tumefaciens-Mediated Transformation and Gene Editing

| Plant Species | Key Innovation | Transformation Efficiency/Editing Rate | Application | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tomato (S. lycopersicum cv. Micro-Tom) | Integration of flow cytometric ploidy analysis | 60% diploidy in regenerated plants (40% polyploidy without screening) | Stable transformation with genetic stability for breeding | [2] |

| Fraxinus mandshurica | CRISPR/Cas9 system targeting plant growth points | 18% editing in induced clustered buds | Functional gene validation (e.g., FmbHLH1 in drought tolerance) | [3] |

| Green Arabidopsis suspension cells | Optimized co-cultivation on solid medium with surfactant | Nearly 100% transient transformation efficiency | High-throughput analysis and recombinant protein production | [4] |

| Sweet Potato, Potato | RAPID method using injection into meristems | High efficiency, shorter duration than traditional methods | Stable transformation without tissue culture | [5] |

| Sunflower | Established transient systems (infiltration, injection, ultrasonic-vacuum) | >90% transient transformation efficiency | Rapid in vivo gene function validation (e.g., HaNAC76) | [6] |

| Elymus nutans (Alpine grass) | First stable transformation system | 19.23% editing efficiency for EnTCP4 | Gene editing for delayed flowering and enhanced drought tolerance | [7] |

Choosing the Right Tool:A. tumefaciensvs.A. rhizogenes

While A. tumefaciens is the workhorse for stable plant transformation, the related bacterium A. rhizogenes is often used to generate transgenic "hairy roots" for functional studies, particularly in root biology and for species recalcitrant to A. tumefaciens transformation [8] [9]. However, a critical consideration is that stable transgenic plants regenerated from A. rhizogenes often exhibit abnormal phenotypes due to the integration of root-inducing (Ri) plasmid genes.

Table 2: Comparison of Agrobacterium Species for Genetic Transformation

| Feature | A. tumefaciens | A. rhizogenes |

|---|---|---|

| Native Plasmid | Tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid | Root-inducing (Ri) plasmid |

| Primary Use | Stable transformation of whole plants | Generation of composite plants with transgenic hairy roots |

| Typical Strain Examples | LBA4404, EHA105, AGL1, GV3101 | K599, MSU440 |

| Stable Plant Phenotype | Generally normal growth and morphology | Frequent abnormalities: dwarfism, wrinkled leaves, reduced fertility [8] |

| Suitability for Breeding | High, after selection of diploid transformants [2] | Low, due to frequent morphological defects [8] |

Protocols for Plant Transformation and Gene Editing

A Highly Efficient Transformation Protocol for Plant Suspension Cells

This protocol, optimized for photosynthetic Arabidopsis suspension cells, achieves near 100% transformation efficiency and is adaptable for other cell culture systems [4].

Key Reagent Solutions

- Agrobacterium Strain: AGL1 (hypervirulent strain)

- Vector: Standard binary vector (e.g., pICH86988 with GFP)

- Plant Material: Photosynthetic Arabidopsis suspension cells in mid-exponential phase (PCV 15-20%)

- Media: AB-MES medium for Agrobacterium growth; MS1 or ABM-MS for co-cultivation

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Agrobacterium Preparation: Inoculate AGL1 from a glycerol stock into YEB medium with appropriate antibiotics (e.g., 50 µg/mL carbenicillin, 25 µg/mL kanamycin). Grow for 20-24 hours at 28°C, 160 rpm.

- Induction: Dilute the pre-culture in AB-MES medium (pH 5.5) containing 200 µM acetosyringone to an OD600 of 0.2. Incubate for 16-20 hours until OD600 reaches 0.3-0.5.

- Harvesting: Centrifuge the bacterial culture at 6800 × g for 10 min. Resuspend the pellet in ABM-MS medium to a final OD600 of 0.8.

- Co-cultivation (Solid Medium Method):

- Wash Arabidopsis suspension cells twice with ABM-MS medium and adjust the Packed Cell Volume (PCV) to 70%.

- Mix 1 mL of washed plant cells with 30 µL of the concentrated Agrobacterium suspension and 200 µM acetosyringone.

- Plate 0.5 mL of the mixture onto solid ABM-MS medium containing 0.8% plant agar and 0.05% (w/v) Pluronic F-68 surfactant.

- Air-dry plates under a laminar flow hood for 10 minutes before sealing.

- Incubate at 24°C under continuous light for 2 days.

- Analysis and Regeneration: After co-cultivation, wash cells with ABM-MS medium containing 250 µg/mL ticarcillin to remove Agrobacterium. The transformed cells can be analyzed for transient expression or transferred to regeneration media for stable line selection.

Figure 1: Workflow for High-Efficiency Transformation of Plant Suspension Cells. The protocol leverages optimized Agrobacterium strain, induction medium, and solid-phase co-cultivation with surfactant to achieve near 100% efficiency [4].

CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing System for Fraxinus mandshurica

This protocol establishes a CRISPR/Cas9 system for a woody plant species without a mature tissue culture system, using growth points as transformation targets [3].

Key Reagent Solutions

- Agrobacterium Strain: EHA105

- Vector: pYLCRISPR/Cas9P35S-N with target sgRNAs

- Plant Material: Sterile plantlets of Fraxinus mandshurica grown from embryos

- Selection Agent: Kanamycin (40-50 mg/L determined as lethal concentration)

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Target Selection and Vector Construction: Design and clone three specific sgRNA targets into the CRISPR/Cas9 vector. Transform the vector into A. tumefaciens EHA105.

- Plant Material Preparation: Germinate sterile F. mandshurica embryos for 7 days on WPM solid medium.

- Agrobacterium Infection:

- Grow the recombinant Agrobacterium in LB medium to an OD600 of 0.5-0.8.

- Centrifuge the bacterial suspension and resuspend the pellet in infection medium.

- Immerse the growth points of the sterile plantlets in the bacterial suspension for 15-30 minutes.

- Co-cultivation and Selection:

- Transfer the infected plantlets to co-cultivation medium and incubate in the dark for 2 days.

- Transfer to selection medium containing kanamycin (40 mg/L) and 250 mg/L cefotaxime to suppress Agrobacterium growth.

- Subculture every 2 weeks until adventitious buds form.

- Regeneration and Screening:

- Induce clustered buds by supplementing media with 0.5 mg/L 6-BA and 0.05 mg/L NAA.

- Screen regenerated buds for edits using PCR and sequencing.

- Induce homozygous plants from the gene-edited chimeric buds using the clustered bud system.

Figure 2: CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing Workflow for Fraxinus mandshurica. This system enables functional gene validation in a recalcitrant woody species by targeting growth points and using a clustered bud regeneration system [3].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium Strains | Delivery vehicle for T-DNA; different strains have varying host ranges and virulence. | LBA4404: Classic disarmed strain [2]. EHA105: Hypervirulent derivative of EHA101, good for monocots and recalcitrant species [3]. AGL1: Hypervirulent, recA- for improved plasmid stability [4]. |

| Binary Vectors | Carry gene of interest between T-DNA borders and selection markers for plants and bacteria. | pCAMBIA1301: GUS reporter, hygromycin resistance [2]. pYLCRISPR/Cas9P35S-N: Modular system for multiplex gRNA expression [3]. |

| Selection Agents | Select for transformed plant tissues and control Agrobacterium growth post-co-cultivation. | Hygromycin B: For plant selection (pCAMBIA1301) [2]. Kanamycin: Common for plant and bacterial selection [3]. Timentin/Cefotaxime: Antibiotics to eliminate Agrobacterium after co-cultivation [3]. |

| Virulence Inducers | Activate Agrobacterium vir genes to enhance T-DNA transfer efficiency. | Acetosyringone: Phenolic compound; use at 100-200 µM in co-cultivation medium [4]. |

| Surfactants | Enhance Agrobacterium contact with and penetration into plant tissues. | Silwet L-77: For vacuum infiltration and immersion [6]. Pluronic F68: For suspension cell transformation, reduces shear stress [4]. |

Agrobacterium tumefaciens has evolved from a known plant pathogen to an indispensable vector for plant genetic engineering. The continued refinement of transformation protocols—embodied by the methods for suspension cells, recalcitrant woody species, and tissue culture-free systems—has dramatically expanded the range of tractable plant species. The integration of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing with Agrobacterium-mediated delivery, as demonstrated in Fraxinus mandshurica and Liriodendron hybrids, represents the current state-of-the-art, enabling precise functional genomics and molecular breeding. These advances ensure that A. tumefaciens will remain a cornerstone technology for fundamental plant research and agricultural biotechnology.

Agrobacterium tumefaciens is a soil-borne phytopathogen that naturally causes crown gall disease in plants. Its unique capability for inter-kingdom DNA transfer has been harnessed by researchers to develop Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (AMT), an indispensable tool in plant biotechnology for transgene insertion into target cells [10] [11]. The natural disease process involves the transfer of a segment of bacterial DNA (T-DNA) from its Tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid into the plant genome, where the expression of encoded genes leads to tumor formation and the production of specialized nutrients called opines that the bacterium utilizes [12]. In laboratory settings, Agrobacterium strains are "disarmed" through the removal of these oncogenic genes while retaining the DNA transfer machinery, enabling researchers to insert user-defined DNA sequences into diverse plant, fungal, and even mammalian cell lines [10]. The simplicity of customizing the sequence between the T-DNA borders has made AMT a foundational technology for agricultural biotechnology, bioenergy crop engineering, and synthetic biology [10].

Core Components of the AMT System

The AMT system relies on the coordinated function of several core components that work together to deliver DNA into plant cells. These components include the T-DNA border sequences, virulence (Vir) proteins, and the Type IV Secretion System (T4SS).

Table 1: Core Components of the Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation System

| Component | Type | Key Function | Molecular Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-DNA Borders | DNA sequence (25 bp imperfect direct repeats) | Define the DNA segment (T-DNA) to be transferred into the plant genome [13] | Recognized and nicked by the VirD1/VirD2 complex [13] |

| VirD1 | Protein (Topoisomerase) | Assists VirD2 in recognizing and nicking the T-DNA border sequences [13] | Works in conjunction with VirD2 to initiate T-DNA processing [13] |

| VirD2 | Protein (Relaxase) | Covalently binds to the 5' end of the nicked T-DNA; pilots the T-DNA complex into the plant nucleus [13] | Acts as a pilot protein, with nuclear localization signals guiding the complex [13] |

| VirE2 | Protein (ssDNA-binding protein) | Coats the single-stranded T-DNA (ssT-DNA) after nicking, protecting it from nucleases [13] | Forms a protective sheath around the ssT-DNA during transfer [13] |

| VirE3, VirD5, VirF | Protein (Effectors) | Suppress plant defense responses and aid in the integration process [12] [14] | Act as host-targeted effector proteins to create a favorable environment for infection [12] |

| Type IV Secretion System (T4SS) | Multi-protein complex | Forms a channel bridging the bacterial and host membranes for T-DNA/protein transfer [12] | Encoded by the vir regulon on the Ti plasmid [12] |

The T-DNA and its Border Sequences

The Transferred DNA (T-DNA) is the segment of DNA that is mobilized and integrated into the host plant genome. In native Ti plasmids, the T-DNA contains genes for phytohormone biosynthesis and opine metabolism. In engineered binary vectors, this region is replaced with user-defined sequences, such as selectable marker genes, genes of interest, or CRISPR/Cas9 machinery [10]. The T-DNA is delineated by left and right border (LB and RB) sequences, which are 25-base-pair imperfect direct repeats that are essential for the transfer process [13]. The right border is critical for polar T-DNA transfer initiation.

Virulence (Vir) Proteins and their Functions

The Virulence (Vir) proteins are encoded by the vir regulon on the Ti plasmid and are induced by specific plant phenolic compounds like acetosyringone [12]. These proteins are responsible for processing and transferring the T-DNA. The VirD1/VirD2 complex recognizes and nicks the T-DNA borders. VirD2 remains covalently attached to the 5' end of the resulting single-stranded T-DNA (ssT-DNA) copy, serving as a pilot protein [13]. The ssT-DNA is then coated with VirE2, a single-stranded DNA-binding protein that protects it from degradation [13]. Additional effector proteins, such as VirE3, VirD5, and VirF, are co-transferred to suppress host defenses and manipulate the host cellular environment to facilitate successful transformation [14].

Diagram 1: The Core AMT Process, illustrating the sequence from plant signal perception to T-DNA integration.

The AMT Process: From Bacterial Cell to Plant Genome

The process of AMT is a sophisticated, multi-step journey that can be broken down into several key stages, as visualized in Diagram 1.

Signal Perception and Vir Gene Induction

The process initiates when Agrobacterium perceives signal molecules exuded by wounded plant tissues, such as acetosyringone and other phenolic compounds [12]. These signals are detected by the bacterial membrane-bound receptor VirA, which then phosphorylates and activates the transcriptional regulator VirG. Activated VirG binds to vir box promoters, inducing the expression of the entire vir regulon [12].

T-DNA Processing and T-Complex Formation

Following vir gene induction, the VirD1/VirD2 endonuclease complex introduces a nick at the 25-bp T-DNA border sequences [13]. VirD2 remains covalently attached to the 5' end of the liberated single-stranded T-DNA (ssT-DNA). The ssT-DNA is then stripped away from the Ti plasmid and coated with numerous molecules of the single-stranded DNA-binding protein VirE2. This forms the mature T-complex, a linear, single-stranded DNA molecule protected by VirE2 and piloted by VirD2 at its 5' end [13].

Transfer Through the Type IV Secretion System (T4SS) and Nuclear Import

The T-complex, along with several Vir effector proteins (e.g., VirE3, VirD5, VirF), is transported into the plant cytoplasm through a Type IV Secretion System (T4SS) [12]. This T4SS is a multi-protein channel that spans both the bacterial and plant membranes. Inside the plant cell, the T-complex is guided to the nucleus. VirD2 contains functional nuclear localization signals (NLSs) that facilitate nuclear import, while some VirE2 molecules interact with the plant importin α protein, further promoting the nuclear uptake of the T-complex [13].

Genome Integration

Once inside the nucleus, the T-DNA is uncoated and integrated into the plant genome. The integration mechanism is not fully understood, but it is known to exploit the plant's DNA repair pathways [15]. Traditionally, T-DNA integration was thought to rely primarily on the plant's non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) pathway, which repairs double-strand breaks in a potentially error-prone manner, leading to random insertions [15]. However, recent research highlights that with precise engineering, the process can be directed toward homology-directed repair (HDR) for precise gene targeting [13].

Advanced Engineering of Agrobacterium for Improved Transformation

Recent innovations have focused on overcoming the biological limitations of native Agrobacterium systems to enhance transformation efficiency, particularly in recalcitrant species.

Binary Vector Copy Number Engineering

A groundbreaking advancement involves engineering the binary vector copy number within Agrobacterium. The copy number of a binary vector is controlled by its origin of replication (ORI). Recent research used a high-throughput growth-coupled selection assay and directed evolution to identify mutations in the RepA protein (which regulates replication) that increase plasmid copy number [10] [11].

Table 2: Impact of Binary Vector Copy Number Engineering on Transformation Efficiency

| Origin of Replication (ORI) | Engineering Approach | Documented Improvement | Tested Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| pVS1 | Directed evolution of RepA to generate higher-copy-number mutants [10] | 60-100% increase in stable transformation efficiency [10] [11] | Arabidopsis thaliana [10] |

| RK2 | Directed evolution of RepA to generate higher-copy-number mutants [10] | Improved transient transformation efficiency [10] | Nicotiana benthamiana [10] |

| pSa | Directed evolution of RepA to generate higher-copy-number mutants [10] | Improved transient transformation efficiency [10] | Nicotiana benthamiana [10] |

| BBR1 | Directed evolution of RepA to generate higher-copy-number mutants [10] | Improved transient transformation efficiency [10] | Nicotiana benthamiana [10] |

| pVS1 (for fungal transformation) | Directed evolution of RepA to generate higher-copy-number mutants [10] | 390% increase in transformation efficiency [10] [11] | Rhodosporidium toruloides (oleaginous yeast) [10] |

Introducing these higher-copy-number mutants into binary vectors significantly improved transient transformation in Nicotiana benthamiana and stable transformation in Arabidopsis thaliana and the oleaginous yeast Rhodosporidium toruloides, demonstrating the profound impact of backbone engineering on AMT outcomes [10] [11].

Ternary Vector Systems and Virulence Tuning

Ternary vector systems represent a powerful strategy to enhance AMT. This approach involves introducing a third plasmid, alongside the binary vector and the disarmed Ti plasmid, which carries accessory virulence genes or plant immune suppressors [14]. Overexpression of specific Vir proteins, such as VirE2, VirD1, VirD2, and VirF, via this system has been shown to increase stable transformation efficiency by 1.5- to 21.5-fold in recalcitrant crops like maize, sorghum, and soybean [14]. This strategy effectively "tunes" the virulence of the Agrobacterium strain, overcoming intrinsic transformation barriers in many plants.

Exploiting Diverse Agrobacterium Strains

Most laboratory transformations rely on a limited set of disarmed Agrobacterium strains (e.g., C58, EHA105, AGL-1, LBA4404) [12]. However, wild Agrobacterium strains exhibit immense natural diversity. Screening novel wild strains or complementing the virulence machinery of standard laboratory strains with genes from wild strains has proven effective in improving T-DNA delivery and reducing explant necrosis in various plant species, including citrus, lettuce, and tomato [12]. Mining this natural diversity provides a rich resource for expanding the host range of efficient AMT.

Application Notes & Protocols: AMT for CRISPR Delivery

The fusion of AMT with CRISPR/Cas technology has revolutionized precision breeding. The following protocols outline key methodologies for implementing and enhancing AMT for CRISPR delivery in plants.

Protocol: CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Targeted T-DNA Integration in Arabidopsis

This protocol describes a method that uses the NHEJ pathway for targeted T-DNA integration, which is reported to be more rapid and efficient than traditional HDR-based methods [15].

Application: Gene activation and male germline-specific gene tagging in Arabidopsis thaliana [15]. Key Reagents: Agrobacterium strain (e.g., EHA105 or GV3101), Binary vector with CRISPR/Cas9 expression cassette, T-DNA donor construct. Methodology:

- Vector Construction: Clone the sgRNA sequence targeting the desired genomic locus into a binary vector containing the Cas9 nuclease. The T-DNA donor construct should contain the gene of interest (e.g., CaMV35S promoter for activation tagging or reporters like MGH3::mCherry for germline tagging) flanked by the appropriate T-DNA borders [15].

- Plant Transformation: Transform Arabidopsis using the floral dip method [15].

- Selection and Screening: Select transformed seeds on appropriate antibiotics. Screen for targeted integration by PCR and confirm through sequencing and phenotypic analysis (e.g., early flowering for FT gene activation) [15].

Protocol: Synergistic CRISPR/Cas9-Vir Protein System for HDR (CvDTL System)

This advanced protocol leverages a fusion of Cas9 with VirD2 and other Vir proteins to significantly enhance HDR efficiency in tobacco and rice [13].

Application: High-efficiency precise genome editing via HDR in model and crop plants [13]. Key Reagents: Agrobacterium strain, psgRNA-CvD vector (expressing Cas9-VirD2 fusion), pVirE2 vector, pVirD1 vector, Donor DNA linked to the complex (Donor Linker) [13]. Methodology:

- Strain Preparation: Engineer Agrobacterium to contain the following:

- The psgRNA-CvD vector expressing the Cas9-VirD2 fusion and the sgRNA.

- The pVirE2 vector for VirE2 expression.

- The pVirD1 vector for VirD1 expression [13].

- Donor Template Design: The donor repair template is covalently linked to the Cas9-VirD2 complex, forming the CvDTL system. This ensures the donor is co-delivered to the DSB site [13].

- Plant Transformation and Analysis: Infect plant explants (tobacco or rice). The HDR frequency with the CvDTL system was shown to be 52-fold higher than control systems, achieving remarkable improvements for endogenous genes like ALS, PDS, and NRT1.1B [13].

Protocol: Agrobacterium rhizogenes-Mediated Hairy Root Transformation for Gene Editing in Woody Plants

This protocol is designed for rapid functional genomics in recalcitrant woody species like Liriodendron hybrid, bypassing the need for a stable tissue culture system [9].

Application: Rapid functional analysis and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in woody plants [9]. Key Reagents: Agrobacterium rhizogenes strain K599 (demonstrated highest efficiency), Binary vector with CRISPR/Cas9 constructs, Sterile seedlings. Methodology:

- Explants Preparation: Use two-month-old sterile Liriodendron hybrid seedlings as explants [9].

- Bacterial Culture and Infection: Grow A. rhizogenes K599 to an OD600 of 0.6-0.8. Resuspend in transformation solution (2 mM MES-KOH, pH 5.4, 10 mM CaCl2, 120 μM acetosyringone, 2% sucrose, 270 mM mannitol). Infect apical bud incisions by dipping or injection [9].

- Co-cultivation and Hairy Root Induction: Co-cultivate for 2 days. Transfer to hormone-free MS medium to induce hairy roots. This system achieved a transformation efficiency of up to 60.38% [9].

- Screening and Validation: Screen hairy roots for fluorescence if using a reporter. Extract DNA to confirm mutagenesis of the target gene (e.g., LhAQP1) via sequencing [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Agrobacterium-Mediated CRISPR Transformation

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use-Case | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Copy Binary Vectors | Increases the dose of T-DNA and CRISPR machinery within Agrobacterium, boosting delivery probability. | Improving stable transformation efficiency in Arabidopsis and yeast. | [10] |

| Ternary Vectors (Accessory Vir Plasmids) | Overexpresses specific Vir genes (VirE2, VirD1, etc.) or defense suppressors to enhance T-DNA transfer and integration. | Overcoming transformation recalcitrance in maize, soybean, and sorghum. | [14] |

| Cas9-VirD2 Fusion System (CvD/CvDTL) | Tethers the DNA repair template to the Cas9 nuclease via VirD2, co-delivering them to the DSB site to dramatically boost HDR. | Achieving precise gene knock-ins or nucleotide substitutions in tobacco and rice. | [13] |

| Agrobacterium rhizogenes Strain K599 | Induces transgenic hairy roots from wound sites, enabling rapid in vivo functional analysis in difficult-to-transform species. | Rapid gene validation and CRISPR editing in woody plants like Liriodendron. | [9] |

| pYLCRISPR/Cas9P35S-N Vector | A modular binary vector system for easy cloning of multiple sgRNAs under plant U6 promoters for multiplexed genome editing. | Targeted mutagenesis of drought-responsive genes in Fraxinus mandshurica. | [16] |

Application Notes: Current Landscape in Plant Research

The CRISPR/Cas9 system has revolutionized plant functional genomics and crop breeding by enabling precise, targeted modifications to DNA. Its application, particularly through Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, has become a cornerstone for introducing desirable traits such as disease resistance, stress tolerance, and improved nutritional quality. The following table summarizes quantitative efficiencies from recent, successful genome-editing initiatives across a diverse range of plant species.

Table 1: Efficiency Metrics of Recent CRISPR/Cas9 Applications in Plants

| Plant Species | Target Gene | Transformation Method | Editing Efficiency | Key Quantitative Outcome | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East African Highland Banana | Phytoene desaturase (PDS) | Agrobacterium-mediated | Up to 100% (in cultivar Nakitembe) | 47 edited events regenerated; complete albinism confirmed pathway disruption [17] | |

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | Not Specified | Agrobacterium-mediated (cotyledon co-culture) | High Efficiency | Production of ≥10 Cas-positive independent lines from 100 cotyledons [18] | |

| Fraxinus mandshurica | FmbHLH1 | Agrobacterium-mediated (growth points) | 18% | 18% of induced clustered buds were gene-edited; confirmed drought tolerance role [16] | |

| Brassica carinata | Not Specified | PEG-mediated Protoplast Transfection | 40% (Transfection) | Achieved 64% protoplast regeneration frequency [19] | |

| Pea (Pisum sativum) | PsPDS | PEG-mediated Protoplast Transfection | Up to 97% (in protoplasts) | Validated gRNA efficiency prior to stable transformation [20] | |

| Oil Palm | Various Agronomic Traits | Agrobacterium-mediated | Low (0.7%-1.5%) | Noted as a major challenge for this monocot tree species [21] |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing Agrobacterium-mediated CRISPR/Cas9 transformation, from vector construction to the regeneration of edited plants.

Protocol 1: Tomato Transformation and Regeneration

This protocol is adapted from a method that uses the Golden Gate cloning system and cotyledon co-culture to achieve high efficiency in tomato [18].

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Tomato Transformation

| Research Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Golden Gate Cloning System | A modular DNA assembly system used to efficiently construct the CRISPR/Cas9 expression vector with multiple sgRNA expression cassettes. |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | A soil bacterium engineered to deliver the T-DNA portion of its plasmid, which contains the CRISPR/Cas9 construct, into the plant cell's genome. |

| Cotyledon Explants | The seed leaves of young tomato seedlings are ideal targets for Agrobacterium co-culture due to their high regenerative capacity. |

| Selective Media (Antibiotics) | Used post-transformation to eliminate untransformed Agrobacterium and to select for plant cells that have integrated the T-DNA (which typically includes a selectable marker gene). |

| Acetosyringone | A phenolic compound secreted by wounded plant cells that induces the Agrobacterium Vir genes, enhancing the efficiency of T-DNA transfer. |

Step-by-Step Method 1. CRISPR/Cas9 Construct Assembly

- Design sgRNAs specific to the target gene.

- Use the Golden Gate cloning system to assemble the sgRNA expression cassettes and the Cas9 nuclease gene into a binary vector suitable for Agrobacterium transformation [18].

2. Plant Material Preparation

- Surface-sterilize tomato seeds and germinate on hormone-free media.

- Excise cotyledons from 7-10 day old seedlings and briefly wound them to create infection sites for Agrobacterium.

3. Agrobacterium Preparation and Inoculation

- Transform the assembled binary vector into Agrobacterium tumefaciens.

- Grow a fresh culture of the transformed Agrobacterium to an OD600 of ~0.5-0.8.

- Resuspend the bacterial pellet in a transformation solution containing acetosyringone.

- Immerse the cotyledon explants in the bacterial suspension for 10-30 minutes [18] [16].

4. Co-culture and Regeneration

- Blot the explants dry and co-culture them on solid media for 2-3 days. This allows the Agrobacterium to transfer the T-DNA to the plant cells.

- Transfer explants to regeneration media containing antibiotics to kill the Agrobacterium and select for transformed plant cells.

- Subculture developing shoots to rooting media. With this protocol, 100 cotyledons can yield at least 10 independent, Cas-positive plant lines [18].

Protocol 2: Growth Point Transformation in Fraxinus mandshurica

This protocol was developed for a recalcitrant woody species where traditional tissue culture is challenging, using a growth point transformation method [16].

Step-by-Step Method 1. Target Selection and Vector Construction

- Identify a target gene (e.g., FmbHLH1 for drought tolerance studies) and design sgRNAs.

- Clone sgRNA oligonucleotides into a BsaI-digested pYLCRISPR/Cas9P35S-N vector.

- Transform the final construct into Agrobacterium strain EHA105 [16].

2. Determination of Selective Agent Lethal Concentration

- Germinate sterile embryos on media containing different concentrations of kanamycin.

- The optimal lethal concentration is identified when embryos turn from green to white, indicating death. For Fraxinus mandshurica, this was determined to be within a 20-70 mg/L range [16].

3. Agrobacterium Infection and Co-culture

- Grow Agrobacterium to an optimized OD600 (e.g., 0.5-0.8) and resuspend in an infection buffer.

- Infect the growing points (meristematic tissues) of sterile plantlets with the bacterial suspension.

- Co-culture the infected plantlets to permit T-DNA transfer.

4. Induction of Clustered Buds and Screening

- Transfer plantlets to a clustered bud induction medium supplemented with specific hormones to stimulate the growth of multiple shoots from the edited growth points.

- Screen the induced buds for edits. In the referenced study, 18% of the clustered buds were gene-edited, from which homozygous plants were successfully recovered [16].

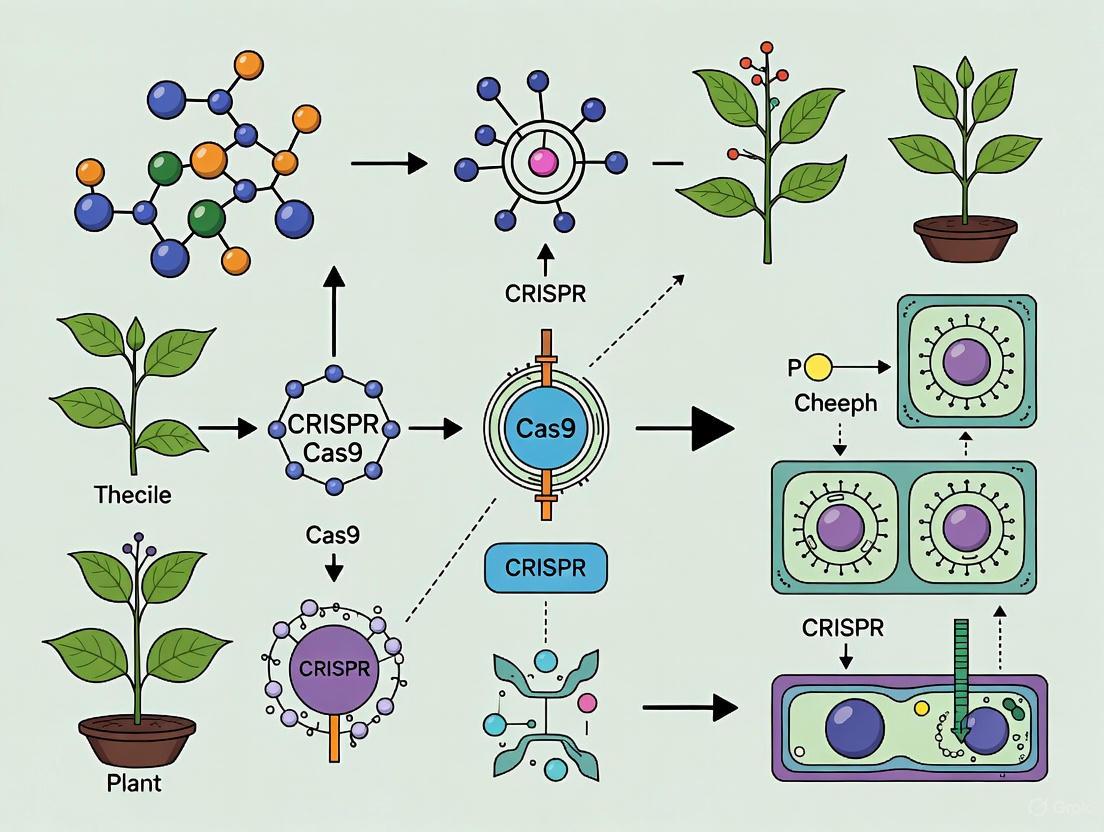

Diagram 1: CRISPR Plant Workflow

Visualization of Methodologies

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between different transformation methods and plant regeneration pathways, highlighting the key distinction between Agrobacterium-mediated and protoplast-based approaches.

Diagram 2: Transformation Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Agrobacterium-mediated CRISPR/Cas9 Plant Transformation

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function |

|---|---|

| Binary Vector System (e.g., pMDC32) | The plasmid backbone that contains the T-DNA region (with Cas9 and sgRNA genes) and the virulence (vir) genes required for transfer into the plant genome. [17] |

| Cas9 Nuclease | The "scissors" – an enzyme that creates double-strand breaks in the DNA at a location specified by the guide RNA. |

| sgRNA (Single Guide RNA) | The "programming" – a chimeric RNA that combines a CRISPR RNA (crRNA) sequence for target recognition and a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) for Cas9 binding. |

| Agrobacterium Strain (e.g., AGL1, EHA105) | The delivery vehicle. Different strains have varying host ranges and transformation efficiencies. [16] [17] |

| Plant Growth Regulators (PGRs) | Hormones (e.g., auxins like NAA, cytokinins like BAP) are critical for inducing cell division, callus formation, and regenerating whole plants from transformed cells. [19] |

| Selection Agents (e.g., Kanamycin) | Allows for the selective growth of only those plant cells that have successfully integrated the transgene (which includes a resistance marker). [16] |

| Acetosyringone | A phenolic compound that activates the Agrobacterium Vir genes, significantly enhancing the efficiency of T-DNA transfer into the plant cell. [16] |

Why Combine Agrobacterium and CRISPR? Advantages for Stable and Transient Editing

The combination of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (AMT) and the CRISPR/Cas system represents a powerful synergy in plant genetic engineering. This partnership leverages the efficient, natural DNA delivery capabilities of the soil bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens with the unparalleled precision of CRISPR-based genome editing. While CRISPR/Cas provides the molecular "scalpel" for making precise cuts in the plant genome, Agrobacterium serves as the "delivery vehicle" that brings this tool into the plant cell. This integration is transforming plant biotechnology by accelerating functional genomics and enabling the development of improved crops with greater precision and efficiency.

The core advantage of this combination lies in its ability to address one of the most significant bottlenecks in plant genetic engineering: the efficient delivery of editing reagents into plant cells, followed by successful regeneration of whole, edited plants. For many crop species, particularly dicotyledonous plants, AMT remains the most efficient, precise, and widely used method for DNA insertion in both public and private sector laboratories [12]. By harnessing this established, biological delivery mechanism for CRISPR/Cas reagents, researchers can achieve high-efficiency editing across a broad range of plant species.

Key Advantages of the Combined System

Enhanced Delivery Efficiency and Broad Host Range

The Agrobacterium-CRISPR system leverages the natural biological machinery of Agrobacterium tumefaciens, which efficiently transfers T-DNA from its tumor-inducing (Ti) plasmid into the plant genome. This mechanism facilitates the delivery of the often large and complex CRISPR/Cas9 constructs directly into plant cells. The system's broad host range is being continuously expanded through the development of novel "domesticated" Agrobacterium strains, engineered from diverse wild-type isolates, which show improved capabilities for transforming previously recalcitrant plant species [12].

Stable Integration for Heritable Modifications

A primary application of Agrobacterium-delivered CRISPR systems is to achieve stable, heritable genetic modifications. The T-DNA, containing genes for the Cas nuclease and guide RNA(s), integrates into the plant genome. This stable integration ensures that the editing machinery is present throughout plant development and is passed to subsequent generations, enabling the creation of homozygous edited lines. This is crucial for the introduction of durable traits such as disease resistance, abiotic stress tolerance, and improved nutritional quality.

Flexibility for Transient Expression and DNA-Free Editing

Beyond stable transformation, the system is highly adaptable for transient expression strategies. In these approaches, the CRISPR/Cas genes are delivered by Agrobacterium but do not integrate into the plant genome. This can result in mutagenesis at the target site while producing edited plants that are transgene-free, which can simplify regulatory approval [22]. Techniques such as agroinfiltration allow for rapid validation of guide RNA efficiency and gene function analysis within days, significantly speeding up the research pipeline [23] [6].

Compatibility with Advanced Vector Systems

The Agrobacterium delivery platform is highly compatible with sophisticated CRISPR vector systems. The development of ternary vector systems has been a transformative innovation, marking a significant advantage over traditional binary vectors. These systems incorporate accessory virulence genes and immune suppressors on a separate plasmid, which work synergistically with the standard binary vector to overcome intrinsic transformation barriers in recalcitrant crops. This approach has enabled 1.5- to 21.5-fold increases in stable transformation efficiency in species like maize, sorghum, and soybean [14]. Furthermore, ternary vectors can be fused with morphogenic regulators such as WUSCHEL (WUS) and BABY BOOM (BBM) to dramatically enhance regeneration, effectively addressing two major bottlenecks simultaneously [14] [24].

Application Notes: From Theory to Practice

Quantitative Impact of Advanced Agrobacterium Systems

The table below summarizes performance improvements achieved through advanced Agrobacterium and delivery systems, based on recent research.

Table 1: Performance Enhancements of Advanced Transformation Systems

| System/Technique | Application / Species | Key Improvement | Efficiency Gain |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ternary Vector Systems [14] | Stable Transformation (Maize, Sorghum, Soybean) | Accessory virulence genes & immune suppressors | 1.5 to 21.5-fold increase in stable transformation |

| Flow Guiding Barrel (FGB) [25] | Biolistic DNA delivery (Onion epidermis) | Optimized gas and particle flow dynamics | 22-fold increase in transient transfection |

| Flow Guiding Barrel (FGB) [25] | Biolistic RNP delivery (Onion epidermis) | Enhanced protein and RNP delivery | 4.5-fold increase in editing efficiency |

Inducible BrrWUSa [24] |

Shoot Regeneration (Turnip) | Chemically-induced morphogenic regulator | Increased regeneration from 0% (control) to 13% |

Case Studies in Diverse Crops

The utility of Agrobacterium-mediated CRISPR delivery is demonstrated by its success across a wide range of crops, overcoming species-specific challenges.

East African Highland Bananas (EAHBs): Researchers achieved highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of the phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene in triploid bananas, a crop notoriously difficult to improve through conventional breeding. Using Agrobacterium strain AGL1 for transformation, they regenerated edited plants with up to 100% albinism rates in one cultivar, confirming high editing efficiency. This established a robust platform for targeted improvement of this vital staple food crop [17].

Turnip (Brassica rapa var. rapa): A major breakthrough was achieved by addressing the critical bottleneck of shoot regeneration. Scientists developed a system using an estradiol-inducible

BrrWUSagene to promote shoot formation. This strategy enabled the generation of fertile,BrrTCP4b-edited plants, which exhibited a ~150% increase in leaf trichome number. This represented a foundational advance for functional genomics in this previously transformation-recalcitrant species [24].Common and Tartary Buckwheat: Optimized Agrobacterium-mediated methods for both transient and stable transformation have been established. These protocols enabled not only the functional analysis of genes but also the metabolic engineering of bioactive compounds, such as the successful production of gramine in infiltrated leaves, showcasing the system's versatility for pathway engineering [23].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Stable Transformation and Genome Editing in Recalcitrant Dicots

This protocol is adapted from successful systems in turnip and banana, utilizing morphogenic regulators to boost regeneration [17] [24].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Agrobacterium Strain: AGL1 [17] or GV3101 [23].

- Binary Vector: Contains a CRISPR/Cas9 expression cassette (e.g., pMDC32Cas9NktPDS [17]) and an inducible morphogenic regulator (e.g., pER8-BrrWUSa [24]).

- Plant Material: Sterile hypocotyl explants or embryogenic cell suspensions (ECS).

Methodology:

- Vector Construction: Clone gene-specific sgRNA(s) into a CRISPR/Cas9 binary vector. A second T-DNA containing a development regulator (e.g.,

WUS,BBM) under a chemical-inducible promoter is recommended. - Agrobacterium Preparation: Transform the binary vector into the Agrobacterium strain. Grow a single colony in liquid medium with appropriate antibiotics to an OD₆₀₀ of 0.5-0.8. Pellet the bacteria and resuspend in inoculation medium.

- Explant Inoculation & Co-cultivation: Immerse explants (e.g., turnip hypocotyl segments) in the Agrobacterium suspension for 15-30 minutes. Blot dry and co-cultivate on solid medium for 2-3 days in the dark.

- Callus Induction & Selection: Transfer explants to callus-induction medium containing the inducer (e.g., 2 μM estradiol for

BrrWUSa), antibiotics to suppress Agrobacterium, and a selection agent (e.g., kanamycin) to select for transformed plant cells. - Shoot Regeneration: After 2-4 weeks, transfer embryogenic calli to shoot-induction medium, again supplemented with the inducer and selection agent.

- Rooting and Regeneration: Once shoots develop, transfer them to rooting medium without the inducer to allow for normal development. Acclimatize resulting plantlets to greenhouse conditions.

- Genotyping: Extract genomic DNA from regenerated plants. Use PCR to amplify the target region and sequence the products to identify mutations.

Protocol 2: Rapid Transient Assay for Gene Function Validation

This protocol, used in sunflower and buckwheat, allows for rapid testing of CRISPR efficiency or transient gene expression within days, bypassing tissue culture [23] [6].

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Agrobacterium Strain: GV3101 [23] [6].

- Binary Vector: Contains the gene of interest or CRISPR/Cas reagents driven by a strong constitutive promoter.

- Infiltration Buffer: MS basal salts, MES, sucrose, and surfactants (e.g., 0.02% Silwet L-77).

Methodology:

- Agrobacterium Culture: Grow Agrobacterium harboring the binary vector to an OD₆₀₀ of 0.8-1.0. Pellet and resuspend in infiltration buffer to a final OD₆₀₀ of 0.8.

- Plant Material Preparation: Use young, fully expanded leaves of soil-grown plants (e.g., 4-6 day old sunflower seedlings or young buckwheat leaves).

- Agroinfiltration:

- Syringe Infiltration: For small-scale tests, use a needleless syringe to press the bacterial suspension into the abaxial side of the leaf.

- Vacuum Infiltration: For high-throughput or whole-seedling transformation, submerge the plant tissue in the bacterial suspension and apply a vacuum (e.g., 0.05 kPa for 5-10 min) before releasing it to allow the suspension to infiltrate the tissue [6].

- Incubation: Maintain infiltrated plants in the dark for 1-3 days to suppress plant defense responses and enhance transgene expression.

- Analysis: Harvest infiltrated tissue after 3-7 days for downstream analyses such as DNA extraction (to check for edits), protein extraction, or metabolic profiling.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Agrobacterium-CRISPR Workflows

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Ternary Vector System [14] | A 3rd plasmid with accessory vir genes/defense suppressors to enhance T-DNA delivery. | Boosting transformation in recalcitrant monocots and dicots. |

| Chemically-Inducible Morphogenic Regulators (e.g., pER8-WUS, pER8-BBM) [24] | Genes that boost regeneration only when induced, avoiding developmental defects. | Improving shoot regeneration in transformation-recalcitrant species like turnip. |

| Agrobacterium Strains (AGL1, GV3101, EHA105) [12] [23] [17] | Disarmed laboratory strains with differing chromosomal backgrounds and virulence plasmids. | Strain selection can be critical for optimizing T-DNA delivery in specific plant hosts. |

| Virulence Inducers (e.g., Acetosyringone) [12] | Phenolic compounds that activate the vir regulon of Agrobacterium. | Added during co-cultivation to maximize T-DNA transfer efficiency. |

| Surfactants (e.g., Silwet L-77) [6] | Reduces surface tension, allowing infiltration buffer to penetrate leaf stomata and air spaces. | Essential for efficient agroinfiltration in transient transformation assays. |

System Workflow and Decision Framework

The following diagram illustrates the core workflows for stable and transient Agrobacterium-mediated CRISPR transformation, highlighting key decision points and components like the ternary system.

A significant bottleneck in plant biotechnology and functional genomics is the recalcitrance of many plant species to genetic transformation, which severely limits the application of advanced breeding techniques like CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing [26]. While model plants such as tobacco and rice are readily transformed, many agronomically important species, particularly legumes, remain stubbornly resistant to standard Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (AMT) protocols [26]. This recalcitrance hinders crop improvement efforts and fundamental research into plant biology. Overcoming this challenge requires a multi-faceted approach, focusing on both the biological agent of transformation—Agrobacterium—and the molecular components of the editing system itself. This Application Note outlines current strategies and detailed protocols designed to expand the host range for efficient and reliable transformation, framed within the broader context of enhancing Agrobacterium-mediated CRISPR transformation in plants.

The Challenge of Transformation Recalcitrance

Transformation recalcitrance is widespread, with efficiency often falling below 15% for many species [26]. Table 1 highlights the stark contrast between transformation-susceptible and recalcitrant plants. This low efficiency is a critical barrier because generating a high number of transformation events is essential for CRISPR-Cas9 workflows; it allows researchers to select the best-edited candidates free of undesirable off-target mutations [26].

Table 1: Comparison of Stable Transformation Efficiencies Across Plant Species

| Plant Name | Type | Typical Explant | Transformation Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lotus japonicus | Susceptible Legume | Seeds | 94 [26] |

| Alfalfa | Susceptible Legume | Leaflets | 90 [26] |

| Nicotiana tabacum | Susceptible Model | Leaf | 100 [26] |

| Soybean | Susceptible Legume | Seeds | 34.6 [26] |

| Vigna radiata (Mung Bean) | Recalcitrant Legume | Cotyledonary node | 4.2 [26] |

| Vigna unguiculata (Cowpea) | Recalcitrant Legume | Cotyledonary node | 3.09 [26] |

| Citrus sinensis | Recalcitrant Tree | Epicotyl segments | 8.4 [26] |

Solutions: Engineering the Engineer and Optimizing the System

Overcoming recalcitrance involves optimizing both the delivery vector (Agrobacterium) and the CRISPR-Cas9 components. Below are key strategies.

Mining Natural Agrobacterium Diversity

Most laboratory AMT relies on a limited set of disarmed strains derived from a small number of wild isolates (e.g., C58, Ach5) [12]. However, natural Agrobacterium populations possess immense genetic diversity, and screening novel wild strains can identify variants with superior virulence for specific recalcitrant hosts [12]. For instance, screening strain collections for citrus transformation identified a novel strain with improved T-DNA delivery and reduced explant necrosis [12].

Engineering Enhanced Agrobacterium Strains

Modern genomic and genetic tools enable direct engineering of Agrobacterium to improve its transformative capabilities. Key approaches include:

- Modifying Virulence Proteins: Complementing laboratory strain virulence genes (e.g., virC, virD4, virD5) with alleles from highly virulent wild strains can enhance T-DNA delivery [12].

- Suppressing Plant Defense Responses: Engineering strains to modulate plant hormone signaling or reactive oxygen species (ROS) production can mitigate plant defense responses that often block transformation in recalcitrant species [27].

Optimizing CRISPR-Cas9 Components

The design of the CRISPR-Cas9 system itself profoundly impacts editing efficiency. Key parameters to optimize include:

- sgRNA GC Content: Higher GC content in the single guide RNA (sgRNA) sequence correlates with increased editing efficiency. A study in grapevine showed efficiency increased proportionally with sgRNA GC content, with 65% GC yielding the highest efficiency [28].

- Codon Optimization of Cas9: The expression level of the Cas9 nuclease, influenced by its codon usage, is linked to editing efficiency. However, strong overexpression is unnecessary and a balanced expression is optimal [29].

- sgRNA Processing: The sequence and structure at the 5' end of the sgRNA are critical. Mismatches at the 5' end can have a strong deleterious effect on CRISPR/Cas9 efficiency [29].

Table 2: Key Parameters for Optimizing CRISPR/Cas9 Editing Efficiency

| Parameter | Influence on Efficiency | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA GC Content | Positive correlation; higher GC (e.g., 65%) yields higher efficiency [28]. | Design sgRNAs with GC content >50%. |

| Cas9 Expression | Moderate correlation; both low and very high expression can be suboptimal [28] [29]. | Use a promoter and codon optimization for balanced, stable expression. |

| Plant Genotype/Variety | Significant effect; efficiency is host-genotype dependent [28]. | Identify and use highly transformable cultivars within a species. |

| sgRNA 5' End Sequence | Critical; mismatches are highly deleterious [29]. | Ensure perfect complementarity at the 5' end of the sgRNA to the target. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Screening Novel Agrobacterium Strains for Improved Transformation

Objective: To identify wild Agrobacterium strains with enhanced transformation capability in a recalcitrant plant species.

Materials:

- Collection of wild-type Agrobacterium strains (e.g., from public repositories)

- Recalcitrant plant explants (e.g., cotyledonary nodes, embryonic calli)

- Standard laboratory Agrobacterium strain (e.g., EHA105, GV3101) as control

- Binary vector with a fluorescent reporter (e.g., GFP)

Method:

- Strain Preparation: Introduce the standard GFP binary vector into each wild strain and the control strain via electroporation or freeze-thaw transformation [12].

- Plant Co-cultivation: Inoculate the target explants with each Agrobacterium strain suspension following standard protocols for the plant species.

- Transient Assay: After co-cultivation, monitor explants for transient GFP expression using fluorescence microscopy at 2-4 days post-infection.

- Necrosis Scoring: Simultaneously, visually assess and score explants for necrosis or browning, which indicates a defense response [12].

- Stable Transformation Assessment: Transfer explants to selection media and record the number of resistant calli or shoots that develop stable GFP expression over subsequent weeks.

Expected Outcome: Identification of one or more wild strains that demonstrate significantly higher transient expression and/or stable transformation frequency, and/or lower induction of necrosis, compared to the standard laboratory control strain.

Protocol: Optimized CRISPR-Cas9 Transformation for Recalcitrant Plants

Objective: To achieve high-efficiency genome editing in a recalcitrant plant by optimizing sgRNA design and transformation conditions.

Materials:

- Binary vector system for CRISPR-Cas9 (e.g., pP1C.4 with plant-optimized Cas9)

- Recalcitrant plant suspension cells or explants (e.g., '41B' grape cells)

- Agrobacterium strain (standard or newly identified improved strain)

Method:

- sgRNA Design: Select multiple target sites within the gene of interest. Use online tools (e.g., Grape-CRISPR) to design sgRNAs with varying GC contents (aim for a range from 25% to 65%) and check for potential off-target sites [28].

- Vector Construction: Assemble the CRISPR-Cas9 constructs, cloning each sgRNA into the binary vector under a suitable promoter (e.g., AtU6) [28].

- Plant Transformation: Transform the plant material using the optimized Agrobacterium-mediated protocol for the specific host. For suspension cells, use a co-cultivation method [28]. For tomato, follow a cotyledon co-culture protocol [18].

- Molecular Analysis: Extract genomic DNA from resistant cell masses or regenerated shoots. Use PCR to amplify the target region and assay for mutations via T7 endonuclease I (T7EI) assay or restriction enzyme (RE) digestion [28].

- Efficiency Calculation: Calculate editing efficiency as the percentage of independently transformed lines showing mutation patterns at the target locus.

Expected Outcome: sgRNAs with higher GC content (e.g., 65%) will demonstrate a measurably higher mutation rate in the target gene compared to those with low GC content.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Expanding Transformation Host Range

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Novel Wild Agrobacterium Strains | Provides a source of diverse T-DNA transfer machinery (Vir proteins) to overcome host-specific defense barriers [12]. |

| "Disarmed" Ri Plasmid Strains | Serves as a alternative transformation vehicle; Ri plasmids (from A. rhizogenes) can sometimes promote transformation in hosts resistant to standard Ti-plasmid strains [12]. |

| Binary Vectors with Codon-Optimized Cas9 | Ensures high and stable expression of the Cas9 nuclease in the plant cell nucleus, which is crucial for efficient induction of double-strand breaks [28] [29]. |

| sgRNAs with High GC Content | Increases the stability and efficiency of the Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complex, leading to higher rates of targeted mutagenesis [28]. |

| Acetosyringone | A phenolic compound added to the co-cultivation medium to induce the expression of the Agrobacterium vir genes, thereby enhancing T-DNA transfer [27]. |

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key biological pathways involved in developing a transformation protocol for a recalcitrant plant species, integrating the strategies discussed above.

From Theory to Practice: Protocols and Crop Transformation Case Studies

The efficacy of Agrobacterium-mediated transformation for delivering CRISPR components into plants is fundamentally dependent on the design of the vector system. These systems serve as the vehicle for transferring genes of interest into the plant genome. Binary vectors have been the long-standing workhorse for this purpose. However, many commercially valuable crops and wild plant relatives remain recalcitrant to genetic transformation due to biological barriers. The recent development of ternary vector systems marks a significant advancement, overcoming these limitations by incorporating accessory virulence genes and immune suppressors that enhance the transformation process [30]. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these systems and protocols for their use in CRISPR-based plant genome engineering.

System Architectures: A Comparative Analysis

The core distinction between binary and ternary systems lies in their configuration and capabilities for facilitating T-DNA transfer from Agrobacterium to plant cells.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Binary and Ternary Vector Systems

| Feature | Binary Vector System | Ternary Vector System |

|---|---|---|

| System Configuration | Two plasmids: a helper plasmid (vir genes) and a binary vector (T-DNA) [31]. | Three plasmids: a helper plasmid, a binary vector (T-DNA), and an accessory plasmid (additional vir genes/immune suppressors) [30]. |

| Key Components | - Binary Vector: T-DNA with cargo (e.g., Cas9, gRNAs).- Helper Plasmid: Provides VirD1/VirD2 for T-DNA excision, VirE2 for single-stranded DNA protection [31]. | Includes all binary components, plus:- Accessory Plasmid: Contains virE1, virE2, virG, etc. [30]. |

| Primary Mechanism | The helper plasmid provides the essential vir genes in trans to mobilize the T-DNA from the binary vector into the plant cell [31]. | The accessory plasmid provides a supplemental suite of vir genes and/or immune suppressors that synergistically enhance T-DNA transfer and integration [30]. |

| Transformation Efficiency | Standard efficiency; sufficient for well-established model species and easily transformable crops. | Reported 1.5- to 21.5-fold increases in stable transformation efficiency in recalcitrant species like maize, sorghum, and soybean [30]. |

| Host Range | Effective for a range of dicot and some monocot species. | Expanded host range, enabling transformation of previously recalcitrant crops and undomesticated wild relatives [32] [30]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow differences between the two systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Delivery

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Agrobacterium-Mediated CRISPR Delivery

| Reagent / Component | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| dCas9 Effectors (CRISPRa/i) | Catalytically "dead" Cas9 fused to transcriptional activators (e.g., VP64, VPR) for CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) or repressors (e.g., KRAB) for CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) [33] [34]. Allows for transient gene regulation without altering DNA sequence. |

| CRISPR-Cas9/-Cas12a | The core editing machinery. Cas9 (Type II) and Cas12a (Type V, formerly Cpf1) are the most commonly used nucleases for inducing double-strand breaks [33] [35]. Selection depends on PAM requirement and desired cleavage pattern (staggered vs. blunt ends). |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) Scaffolds | Synthetic RNA molecules (sgRNA) that direct the Cas nuclease to the target genomic locus. Engineered scaffolds like MS2 and SunTag can recruit effector domains for enhanced transcriptional modulation [33] [34]. |

| Morphogenic Regulators | Transcription factors (e.g., BABY BOOM, WUSCHEL) delivered transiently to enhance regeneration potential, particularly in recalcitrant species [30]. |

| T-DNA Binary Vector | The plasmid containing the left and right border sequences that flank the "transfer DNA" (T-DNA), which is integrated into the plant genome. It carries the cargo (Cas transgene, gRNA expression cassettes) [31]. |

| Ternary Accessory Plasmid | A supplementary plasmid carrying additional vir genes (e.g., virE1, virE2, virG) or plant immune suppressors. It is co-resident in the Agrobacterium strain and provides enhanced virulence functions in trans [30]. |

| Plant Selection Agents | Antibiotics (e.g., kanamycin, hygromycin) or herbicides used in culture media to select for plant cells that have successfully integrated the T-DNA, which contains a corresponding resistance gene. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Protocol 1: Assembling a Multiplex CRISPR T-DNA Construct for Binary Vectors

This protocol details the cloning of multiple gRNA expression units into a single binary vector for coordinated editing of several genomic loci, a key strategy for addressing genetic redundancy in plants [32].

- Step 1: gRNA Design and Selection. For CRISPR knockouts, design gRNAs with high on-target efficiency and minimal off-target effects against all redundant gene family members (e.g., MLO genes for powdery mildew resistance) [32]. For transcriptional regulation with CRISPRa/i, design gRNAs targeting promoter or enhancer regions of the gene of interest [33] [36].

- Step 2: Choosing an Assembly Strategy. Select a method for expressing multiple gRNAs:

- tRNA-based System: Utilize endogenous tRNA processing systems by designing gRNA sequences flanked by tRNA genes. The cellular machinery will cleave the primary transcript into individual, functional gRNAs [32].

- Ribozyme-based System: Use self-cleaving ribozymes (e.g., Hammerhead ribozyme) flanking each gRNA unit to process a single transcript into multiple gRNAs.

- Polycistronic gRNA Array: Engineer a single transcript with multiple gRNA sequences separated by direct repeats, which are processed by the native Cas system of enzymes like Cas12a [32].

- Step 3: Golden Gate Assembly. Employ Golden Gate cloning using Type IIS restriction enzymes (e.g., BsaI, BbsI). These enzymes cut outside their recognition sequence, allowing for the seamless, directional, and simultaneous assembly of multiple gRNA modules into a single destination binary vector.

- Step 4: Transformation and Verification. Transform the final assembled plasmid into Agrobacterium and verify the integrity of the T-DNA region via colony PCR and Sanger sequencing before plant transformation.

Protocol 2: Utilizing a Ternary Vector System for Recalcitrant Species

This protocol outlines the use of a ternary system to transform plant species that are notoriously difficult to modify using standard binary vectors.

- Step 1: Prepare the Agrobacterium Strain. Co-transform or sequentially transform the Agrobacterium strain (e.g., LBA4404, EHA105) with the three essential plasmids:

- The Helper Plasmid (e.g., pTi-SAKON) providing the core Vir functions.

- The Binary Vector containing your CRISPR T-DNA construct from Protocol 1.

- The Ternary Accessory Plasmid (e.g., pVIR9) carrying supplemental vir genes.

- Step 2: Validate Plasmid Co-residence. Isolate the Agrobacterium colony and perform plasmid extraction followed by restriction digest or PCR to confirm the presence of all three plasmids.

- Step 3: Co-cultivation with Plant Explants.

- Prepare the bacterial suspension to an optimal density (OD₆₀₀ typically 0.2-0.6) in a suitable liquid medium.

- Immerse explants (e.g., immature embryos, leaf discs) in the suspension for 10-30 minutes.

- Blot the explants dry and co-cultivate on solid medium for 2-3 days in the dark.

- Step 4: Selection and Regeneration. Transfer explants to selection media containing the appropriate antibiotic and plant growth regulators to initiate callus formation and subsequent shoot regeneration. The ternary system's enhanced efficiency should yield a greater number of resistant calli and regenerative events compared to a binary system control [30].

- Step 5: Molecular Analysis of T₀ Plants.

- Genotyping: Use high-throughput amplicon sequencing (amplicon-seq) or long-read sequencing technologies to characterize the full spectrum of edits, including large deletions and structural rearrangements that can occur with multiplex editing [32].

- Transgene Detection: Perform PCR to confirm the presence of the Cas9 transgene.

- Off-Target Analysis: Employ methods like DISCOVER-Seq to identify and assess potential off-target effects [31].

The following workflow provides a visual summary of the key experimental steps in this protocol.

The strategic design of vector systems is paramount to the success of Agrobacterium-mediated CRISPR transformation in plants. While binary vectors provide a robust foundation, ternary vector systems represent a transformative innovation, effectively expanding the host range and increasing efficiency. The integration of these advanced delivery tools with sophisticated CRISPR applications—from multiplex gene editing to precise transcriptional control—is reshaping plant biotechnology. This empowers researchers to tackle complex polygenic traits and accelerate the de novo domestication of wild species, thereby contributing to the development of more resilient and high-performing crops.

In plant genetic engineering, the choice of explant—the tissue fragment used to initiate a culture—is a foundational decision that critically influences the success of Agrobacterium-mediated CRISPR transformation. This process requires both efficient delivery of genetic material and the subsequent ability of transformed cells to regenerate into whole plants. Explants from specific developmental stages, such as hypocotyls, embryos, and meristems, are often preferred because they contain populations of meristematic or juvenile cells with high regenerative potential. The trend in modern plant biotechnology is moving toward explants and methods that bypass lengthy tissue culture processes, thereby accelerating functional genomics research and crop improvement programs [37] [38]. This document provides a detailed guide on the selection and use of these key explants, framed within the context of a broader thesis on optimizing plant transformation.

Explant Characteristics and Comparative Analysis

Different explants offer unique advantages and are suited to specific plant species and transformation goals. The table below summarizes the key characteristics, regeneration pathways, and research applications of hypocotyls, embryos, and meristems.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of key explants for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation.

| Explant Type | Developmental Origin & Characteristics | Common Regeneration Pathway | Example Species & Efficiency | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypocotyl | The embryonic stem between root and cotyledons; contains juvenile, highly proliferative cells. | Callus-mediated organogenesis, indirect shoot regeneration. | Sugarbeet: 36% shoot regeneration from calli [39]. Pepper: Used in efficient transformation system [40]. | High cell division activity; readily forms callus; amenable to co-culture with Agrobacterium. |

| (Mature/Immature) Embryo | Mature: dormant embryo from dry seed. Immature: harvested from developing seed pre-maturity. | Direct or indirect organogenesis; somatic embryogenesis. | Apple: Somatic embryos as excellent receptors [41]. Rice: Mature embryos, 3.5%-6.5% transformation efficiency [38]. | Genotype-independent potential (mature); high embryogenic potential (immature); ideal for monocots. |

| Meristem | The undifferentiated, totipotent tissue in shoot and root apices; includes axillary buds. | Direct organogenesis, avoiding a callus phase. | Perennial ryegrass: 14.2%-46.65% efficiency via SAAT [38]. Cotton: In planta root transformation [42]. | Reduces somaclonal variation and chimerism; enables in planta transformation strategies. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The following section provides step-by-step methodologies for utilizing hypocotyls and establishing somatic embryogenesis, as derived from recent, optimized studies.

Protocol: Hypocotyl-Based Transformation and Regeneration

This protocol, adapted from sugarbeet and pepper transformation systems, outlines the process from explant preparation to plant regeneration [40] [39].

1. Explant Preparation and Inoculation: - Plant Material: Surface-sterilize seeds and germinate in vitro on hormone-free MS medium for 10-14 days until hypocotyls are elongated. - Explant Excission: Cut hypocotyls into segments approximately 1 cm in length. - Agrobacterium Preparation: Inoculate an Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain (e.g., GV3101) carrying the binary vector with the gene of interest (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9 construct and visual marker like RUBY) in liquid culture. Grow to an OD₆₀₀ of 0.4-0.6 [39]. - Inoculation: Immerse hypocotyl segments in the Agrobacterium suspension. For enhanced efficiency, apply a brief vacuum infiltration (e.g., -0.06 MPa for a few minutes) to improve bacterial entry [40].

2. Co-culture and Callus Induction: - Co-culture: Blot-dry the explants and transfer to a co-culture medium (often solid MS medium with acetosyringone). Incubate in the dark at 24 ± 2°C for 2-3 days. - Callus Induction (CIM): Transfer explants to a Callus Induction Medium (CIM). A standard formulation includes MS salts, sucrose (30 g/L), agar (7-8 g/L), cytokinin (e.g., 2.0 mg/L BAP), and auxin (e.g., 0.1 mg/L IAA or NAA). Include antibiotics to eliminate Agrobacterium (e.g., Timentin) and a selective agent (e.g., Kanamycin at 75-100 mg/L). Culture in the dark for 3-4 weeks, with sub-culturing every 2 weeks [40] [39].

3. Shoot and Root Regeneration: - Shoot Induction (SIM): Upon callus formation, transfer embryogenic calli to a Shoot Induction Medium. This medium typically has a reduced cytokinin concentration (e.g., 0.5 mg/L Zeatin riboside or BAP) and may include gibberellic acid (GA₃, 0.17 mg/L) to promote shoot elongation. Culture under a 16-hour photoperiod. - Root Induction (RIM): Once shoots elongate to 2-3 cm, excise them and transfer to a Root Induction Medium. This is typically a half- or full-strength MS medium with an auxin such as Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) at 1-2 mg/L [40]. - Acclimatization: After root development, carefully transfer plantlets to soil in a controlled environment with high humidity for hardening.

Protocol: Establishing Somatic Embryogenesis for Transformation

Somatic embryos are bipolar structures that can germinate directly into plants, offering high genetic stability. This protocol is based on successful systems in apple and other woody plants [41] [43].

1. Induction of Embryogenic Callus: - Explant Selection: Use juvenile tissues such as immature zygotic embryos, leaf bases, or cotyledons. For apple, young leaves from in vitro shoots are effective explants [41]. - Culture on Induction Medium: Culture explants on an auxin-rich medium. A common formulation is MS medium supplemented with a synthetic auxin like 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) at 1-2 mg/L. Pro-embryogenic masses will form from the explant over 4-8 weeks.

2. Transformation and Maturation of Somatic Embryos: - Transformation: Infect the embryogenic callus with Agrobacterium carrying the desired construct, following a similar inoculation and co-culture process as for hypocotyls. - Maturation: After selection on antibiotic-containing medium, transfer the transformed embryogenic tissue to a maturation medium. This medium often has a reduced auxin concentration or is auxin-free, and may contain abscisic acid (ABA) to promote the development of cotyledonary-stage somatic embryos. - Regeneration: Mature somatic embryos are transferred to a germination medium (low-salt medium like GD or half-strength MS without plant growth regulators) where they develop into plantlets.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents and their critical functions in explant-based transformation protocols, as identified from the cited research.

Table 2: Key research reagents and their functions in transformation protocols.

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in the Protocol | Example Usage & Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Murashige & Skoog (MS) Basal Medium | Provides essential macro and micronutrients for explant growth and development. | Used as the base for all culture media (CIM, SIM, RIM) [40] [39]. |

| Plant Growth Regulators (Zeatin, BAP, IAA, 2,4-D) | Direct cell fate: cytokinins promote shoot formation; auxins promote root and callus formation. | Zeatin riboside (2 mg/L) in CIM; IBA (2 mg/L) in RIM [40]; 2,4-D for somatic embryogenesis [41]. |

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) | Ethylene inhibitor; prevents ethylene-induced senescence and improves shoot regeneration. | 4 mg/L in callus induction medium for pepper transformation [40]. |

| RUBY Reporter | A visual, pigment-based marker (produces betalain, red color) for detecting transformation without specialized equipment. | Used to visually identify transformed callus and shoots in pepper and sugarbeet [40] [39]. |

| Timentin / Carbenicillin | Antibiotics used to suppress or eliminate Agrobacterium after co-culture. | Commonly used at 300-500 mg/L in post-co-culture media [40] [39]. |

| Developmental Regulators (e.g., GRF-GIF, WOX, BBM) | Transcription factors that enhance plant regeneration capacity and transformation efficiency. | Overexpression of SlGIF1 improved pepper transformation [40]. MdWOX4 enhanced somatic embryogenesis in apple [41]. |

Regulatory Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Understanding the molecular networks that control cell fate is key to improving regeneration. Key pathways involve auxin signaling and specific transcription factors.

Diagram 1: Gene regulation in somatic embryogenesis.

The developmental potential of explants is governed by complex internal signaling networks. A critical pathway for somatic embryogenesis, as elucidated in apple, begins with auxin signaling activating key transcription factors like MdARF5 [41]. This factor directly binds to and activates the promoter of MdWOX4, a WUSCHEL-RELATED HOMEOBOX gene. MdWOX4 promotes the formation of embryogenic cells, which proceed through somatic embryo development and ultimately regenerate into whole plants. This knowledge allows researchers to enhance regeneration by overexpressing these developmental regulators in recalcitrant explants.

Integrated Workflow for Explant Transformation

The journey from explant to a regenerated, genetically modified plant involves a series of critical and sequential steps.

Diagram 2: Transformation and regeneration workflow.

The strategic selection of hypocotyls, embryos, or meristems as explants is a cornerstone of successful Agrobacterium-mediated CRISPR transformation. As plant functional genomics and precision breeding advance, the optimization of explant-specific protocols will remain paramount. Future perspectives point toward the increased use of developmental regulators to boost regeneration and the development of in planta delivery methods that further reduce dependence on tissue culture, thereby enabling the transformation of a wider range of species, including recalcitrant woody plants [37] [38] [43]. The protocols and data summarized here provide a actionable framework for researchers to advance their work in plant genetic engineering.

A Step-by-Step Agrobacterium Co-cultivation and Transformation Protocol

Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation is a cornerstone of modern plant biotechnology, enabling the stable integration of foreign genes into plant genomes. Within the broader scope of thesis research on Agrobacterium-mediated CRISPR transformation, a robust and reproducible co-cultivation protocol is paramount. This process, where Agrobacterium transfers T-DNA into plant cells, is a critical determinant of transformation success [44]. This application note provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for Agrobacterium co-cultivation and transformation, designed to be adaptable across diverse plant species while emphasizing the context of delivering CRISPR-Cas9 components for genome editing.

The co-cultivation phase involves the intimate association of Agrobacterium with plant explants under conditions that induce the bacterial virulence (vir) gene system [44]. Key parameters such as bacterial density, duration of co-cultivation, and the presence of phenolic elicitors like acetosyringone must be meticulously optimized to maximize T-DNA delivery while maintaining explant viability [45] [46]. The following sections outline a generalized, optimized protocol, summarize key quantitative data, and provide a specialized workflow for CRISPR plant engineering.

Key Experimental Parameters and Reagents

Optimizing physical and chemical parameters during co-cultivation is essential for high transformation efficiency. The table below consolidates optimized conditions from recent studies on various plant species.

Table 1: Optimized Co-cultivation Parameters for Different Plant Species

| Plant Species | Agrobacterium Strain | Optical Density (OD₆₀₀) | Acetosyringone (μM) | Co-cultivation Duration (Days) | Transformation Frequency | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Clover | EHA105 | 0.5 | 20,000 | 4 | 1.92 - 3.47% | [45] |

| Sorghum | AGL1 | 0.7 | 100 | 3 | Up to 33% | [47] |

| Wheat | AGL1 / AGL0 | Not Specified | 200 | 2-3 | >100 transgenic lines | [46] |

| Tomato | GV3101 | Not Specified | 200 | 2-3 | ~10% (Cas-positive lines) | [18] [48] |