Advanced Detection Methods for CRISPR-Induced Mutations in Plants: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current methodologies for detecting and validating CRISPR-induced mutations in plants, tailored for researchers and biotechnology professionals.

Advanced Detection Methods for CRISPR-Induced Mutations in Plants: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the current methodologies for detecting and validating CRISPR-induced mutations in plants, tailored for researchers and biotechnology professionals. It covers the foundational principles of CRISPR editing outcomes, explores a range of detection techniques from conventional PCR to advanced isothermal amplification and high-throughput sequencing, and addresses common challenges in optimization and specificity. The content further delves into rigorous validation protocols and comparative analyses of different methods, emphasizing their application in ensuring regulatory compliance and advancing precise molecular breeding. By synthesizing the latest research and development in the field, this guide serves as an essential resource for the accurate characterization of gene-edited plants.

Understanding CRISPR Editing Outcomes and Detection Imperatives in Plants

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic research by providing scientists with unprecedented precision in genome editing. This technology operates as molecular scissors, creating targeted double-strand breaks (DSBs) in DNA at specific locations guided by RNA sequences. However, the CRISPR-Cas9 machinery itself does not perform the genetic modification; it merely creates the initial cut. The actual genetic editing occurs through the cell's endogenous DNA damage repair (DDR) pathways, which join the two cut ends together, leading to various genetic outcomes including knockouts, precise point mutations, or knockins [1] [2].

When DNA damage occurs, a series of DDR pathways are activated to sense and fix the disrupted sequences. These pathways are essential for maintaining genomic integrity across all organisms. Although DNA damage can affect one or both DNA strands, DSBs are particularly significant in CRISPR/Cas9 applications because they represent the type of damage intentionally created by the system [1]. Researchers strategically leverage these endogenous DNA repair pathways to generate genetically edited organisms, furthering the study of human disease, agricultural improvement, and the development of new therapeutics [1] [3] [4].

The two primary repair pathways for DSBs are non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homology-directed repair (HDR). Additionally, alternative pathways such as microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) and single-strand annealing (SSA) play significant roles in repair outcomes, especially in the context of CRISPR-mediated gene editing [5]. Understanding the intricate interplay between these pathways is crucial for optimizing CRISPR experiments, particularly in plant research where detection of successful mutations requires careful consideration of these repair mechanisms.

DNA Repair Pathways in CRISPR-Mediated Genome Editing

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): The Efficient but Error-Prone Pathway

Non-homologous end joining represents the dominant and most efficient DSB repair pathway in most eukaryotic cells, including plants. This pathway operates throughout the cell cycle and functions by quickly rejoining broken DNA ends without requiring a homologous template. The process begins with the recognition of DSBs by the Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer, which then recruits and activates DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit (DNA-PKcs). After processing of the DNA ends by various nucleases and polymerases, the DNA ligase IV complex catalyzes the final ligation step [4] [6].

The speed of NHEJ comes at the cost of precision—this pathway often leads to small insertions or deletions (INDELs) at the repair site. A commonly observed phenomenon accompanying DSBs is the creation of very small single-stranded overhangs that can create regions of "microhomology" to guide repair. Unfortunately, imprecise repair frequently results in the loss or gain of a small number of nucleotides, effectively knocking out the gene of interest due to INDEL formation resulting in loss of function, frameshift mutations, or creation of a premature stop codon [1].

For researchers aiming to create gene knockouts, especially in plant models, NHEJ is often the preferred pathway due to its high efficiency. The consistent generation of small (1-10 base pair) INDEL errors can disrupt gene function, making NHEJ ideal for gene knockout studies where the goal is to inactivate or disrupt a gene [1] [3]. To generate knockouts using NHEJ, researchers typically need Cas9 nuclease, single guide RNAs (sgRNA), and PCR primers for validation via sequencing [1].

Distinguishing Features of NHEJ:

- Template-independent repair mechanism

- Functions throughout the cell cycle

- High efficiency but error-prone

- Generates insertions/deletions (INDELs)

- Ideal for gene knockout studies

- Faster repair kinetics compared to HDR [1] [4] [7]

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): The Precise but Inefficient Pathway

Homology-directed repair represents a precise DNA repair mechanism that utilizes homologous sequences as templates for accurate DSB repair. Unlike NHEJ, HDR requires a DNA template containing homologous sequences to the regions flanking the DSB—this can be a sister chromatid, a donor homology plasmid, or single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs). In CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, researchers design a donor template that includes the DNA sequence they want to insert, flanked by homology arms that match the ends of the cut DNA [1] [2].

The HDR process initiates with 5' to 3' DNA end resection to generate single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhangs. The MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 (MRN) complex plays a crucial role in this initial step. Subsequently, replication protein A (RPA) binds to and protects the ssDNA overhangs before being replaced by RAD51 with the assistance of mediator proteins such as BRCA2. The RAD51-ssDNA filament then invades the homologous donor template, leading to DNA synthesis using the donor as a template. Finally, the newly synthesized DNA is resolved and integrated [4] [6].

HDR offers unparalleled accuracy for generating precise genetic modifications, making it the pathway of choice for knockins, point mutations, and tagging genes with fluorescent proteins for tracking gene expression. However, HDR has significantly lower efficiency compared to NHEJ, as it only occurs during specific phases of the cell cycle (S and G2) where homologous DNA is naturally available. Another important consideration when designing a gene edit with HDR is ensuring the homology arms are as close to the DSB as possible [1] [2].

Distinguishing Features of HDR:

- Template-dependent repair mechanism

- Primarily active in S and G2 cell cycle phases

- Low efficiency but high precision

- Enables precise knockins and specific mutations

- Requires donor DNA template with homology arms

- Essential for precise genome editing applications [1] [2] [7]

Alternative Repair Pathways: MMEJ and SSA

Beyond the primary NHEJ and HDR pathways, alternative repair mechanisms significantly influence CRISPR editing outcomes, particularly in plant systems. Microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) represents an error-prone repair pathway that relies on short microhomology sequences (2-20 base pairs) flanking the DSB. During MMEJ, these microhomologous regions anneal, resulting in deletions of the intervening sequence. The key enzyme driving MMEJ is DNA polymerase theta (POLQ), which makes this pathway a potential target for modulation [5] [6].

Single-strand annealing (SSA) constitutes another error-prone repair pathway that requires longer homologous sequences (typically >30 base pairs) for repair. SSA depends on the RAD52 protein, which mediates the annealing of complementary single-stranded DNA sequences. This pathway typically results in deletions of the sequence between the homologous regions [5].

Recent research has demonstrated that these alternative pathways contribute substantially to imprecise repair outcomes in CRISPR-mediated gene editing. A 2025 study revealed that even with NHEJ inhibition, various patterns of imprecise repair persist in CRISPR-mediated knock-in, largely due to MMEJ and SSA activity. Specifically, suppressing either MMEJ (using POLQ inhibitors) or SSA (using Rad52 inhibitors) reduces nucleotide deletions around the cut site, thereby elevating knock-in accuracy [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Major DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways

| Pathway | Template Required | Key Proteins | Fidelity | Cell Cycle Phase | Main Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHEJ | No | Ku70/80, DNA-PKcs, XLF, XRCC4, Ligase IV | Error-prone | All phases | INDELs (insertions/deletions) |

| HDR | Yes (homologous) | MRN complex, BRCA1, BRCA2, RAD51, RAD52 | High-fidelity | S and G2 | Precise repair/knockin |

| MMEJ | No (microhomology) | PARP1, POLQ, FEN1, Ligase I/III | Error-prone | S and G2 | Deletions using microhomology |

| SSA | Yes (direct repeats) | RAD52, ERCC1, XPF | Error-prone | S and G2 | Deletions between repeats |

Quantitative Comparison of NHEJ and HDR Efficiency and Outcomes

Understanding the quantitative differences between NHEJ and HDR is crucial for designing CRISPR experiments and interpreting results, particularly in plant research where detection methods must be tailored to expected mutation profiles. The efficiency disparity between these pathways is substantial, with NHEJ typically dominating the repair landscape.

Experimental data from human cell studies demonstrate that NHEJ-mediated repair occurs with significantly higher frequency than HDR across most cell types. In standard conditions without pathway modulation, NHEJ accounts for approximately 75-85% of DSB repair events, while HDR typically represents only a minor fraction [4] [6]. This efficiency gap presents a major challenge for applications requiring precise edits.

Recent research has quantified the impact of various modulation strategies on HDR efficiency. A 2025 study investigating CRISPR-mediated endogenous tagging in human cells reported that inhibition of the NHEJ pathway using Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 increased knock-in efficiency approximately 3-fold for both Cpf1-mediated knock-in (from 5.2% to 16.8%) and Cas9-mediated knock-in (from 6.9% to 22.1%) [5]. This study also demonstrated that even with NHEJ inhibition, the proportion of perfect HDR events remained below 50% among all integration events, highlighting the significant contribution of alternative repair pathways to imprecise integration.

Table 2: Quantitative Outcomes of DNA Repair Pathways in CRISPR-Mediated Editing

| Repair Pathway | Typical Efficiency | Common Mutational Signature | Impact on Gene Function | Optimal Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHEJ | High (75-85% of repairs) | Small INDELs (1-20 bp) | Frameshifts, premature stop codons, gene knockouts | Gene disruption studies, functional knockout screening |

| HDR | Low (1-20% of repairs) | Precise sequence integration | Defined sequence changes, gene correction, protein tagging | Precise mutation introduction, gene correction, epitope tagging |

| MMEJ | Intermediate (5-15% of repairs) | Deletions flanked by microhomology | In-frame deletions, exon skipping, gene disruption | Less characterized, often contributes to imprecise editing |

| SSA | Low (<10% of repairs) | Large deletions between repeats | Major genomic rearrangements, gene disruption | Less characterized, contributes to imprecise integration |

The fidelity of each repair pathway also varies substantially. NHEJ typically produces INDELs ranging from 1-20 base pairs, with a predominance of deletions over insertions. HDR, when successful, achieves precise integration with near-perfect fidelity when appropriate donor templates are provided. The alternative pathways MMEJ and SSA produce more substantial deletions—MMEJ typically creates deletions of 10-100 base pairs flanked by microhomology regions, while SSA can generate large deletions exceeding hundreds of base pairs between homologous repeats [5].

In plant systems, these quantitative relationships are particularly important for designing detection methods, as the expected distribution of mutation types must be considered when selecting analytical approaches. For instance, techniques focused on detecting small INDELs (such as T7E1 assay or fragment analysis) will capture predominantly NHEJ events, while methods for verifying precise integration (such as PCR with verification sequencing) are necessary for confirming HDR outcomes.

Experimental Protocols for Studying DNA Repair Pathways in CRISPR Editing

Protocol for Assessing HDR Efficiency in Plant Systems

A standardized protocol for evaluating HDR efficiency in plant models involves the following key steps:

Design and Synthesis of Editing Components: Design sgRNAs targeting the gene of interest, ensuring high on-target activity and minimal off-target potential. Synthesize Cas9 nuclease (as protein, mRNA, or encoded in a delivery vector) and in vitro transcribed sgRNAs. Design donor DNA templates with homology arms (typically 90-1000 bp, depending on the system) flanking the desired insertion sequence [5] [4].

Delivery of CRISPR Components: For plant systems, common delivery methods include:

- Agrobacterium-mediated transformation: Clone Cas9, sgRNA, and donor template into appropriate binary vectors and transform using standard Agrobacterium protocols [4] [8].

- PEG-mediated protoplast transformation: Deliver CRISPR ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes directly to protoplasts along with donor DNA [8].

- Virus-induced genome editing (VIGE): Utilize viral vectors to deliver editing components, as demonstrated in tomato with TRV-based systems [8].

Pathway Modulation: To enhance HDR efficiency, apply pathway-specific modulators:

- NHEJ inhibition: Use small molecule inhibitors such as Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 or NU7026 [5] [6].

- MMEJ inhibition: Apply ART558, a specific inhibitor of POLQ [5].

- SSA inhibition: Utilize D-I03, a Rad52 inhibitor [5]. Treatment typically occurs for 24 hours immediately following delivery of editing components, based on evidence that HDR primarily occurs within this timeframe after Cas9 delivery [5].

Detection and Quantification: After appropriate culture duration (typically 4-7 days for initial assessment):

- Extract genomic DNA from edited tissue

- Amplify target regions using PCR with flanking primers

- Analyze editing efficiency using sequencing-based methods (Sanger sequencing with decomposition tools or next-generation sequencing)

- For HDR-specific detection, use restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) if the edit introduces or removes a restriction site, or employ allele-specific PCR [5] [4].

Validation: Confirm precise editing through Southern blotting, long-read sequencing (PacBio or Nanopore), or functional assays specific to the edited gene [5].

Protocol for Comparative Analysis of Multiple Repair Pathways

A comprehensive 2025 study established a robust protocol for simultaneously analyzing contributions of multiple repair pathways to CRISPR editing outcomes:

Experimental Setup:

- Utilize hTERT-immortalized RPE1 cells or plant protoplasts for editing experiments

- Apply a cloning-free endogenous tagging method with donor DNA prepared by PCR using primers containing 90-base homology arms

- Form RNP complexes by mixing recombinant Cas nucleases with in vitro transcribed guide RNAs

- Deliver RNPs and donor DNA via electroporation (for cells) or PEG-mediated transformation (for protoplasts) [5]

Pathway Inhibition Conditions:

- Control: No pathway inhibitors

- NHEJ inhibition: Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2

- MMEJ inhibition: ART558 (POLQ inhibitor)

- SSA inhibition: D-I03 (Rad52 inhibitor)

- Combination treatments: NHEJi + MMEJi or NHEJi + SSAi [5]

Outcome Analysis:

- Perform long-read amplicon sequencing using PacBio technology 4 days post-editing

- Conduct genotyping using computational frameworks like knock-knock for precise classification of repair outcomes

- Categorize sequencing reads into specific repair outcomes: WT, indels, perfect HDR, or subtypes of imprecise integration [5]

Data Interpretation:

- Quantify the percentage of perfect HDR events under each inhibition condition

- Calculate the reduction in specific imprecise repair patterns (large deletions, asymmetric HDR, etc.)

- Determine statistical significance of pathway modulation on editing precision [5]

This protocol enables researchers to comprehensively map how each repair pathway contributes to final editing outcomes and identify optimal inhibition strategies for improving precise editing efficiency.

Pathway Visualization and Molecular Mechanisms

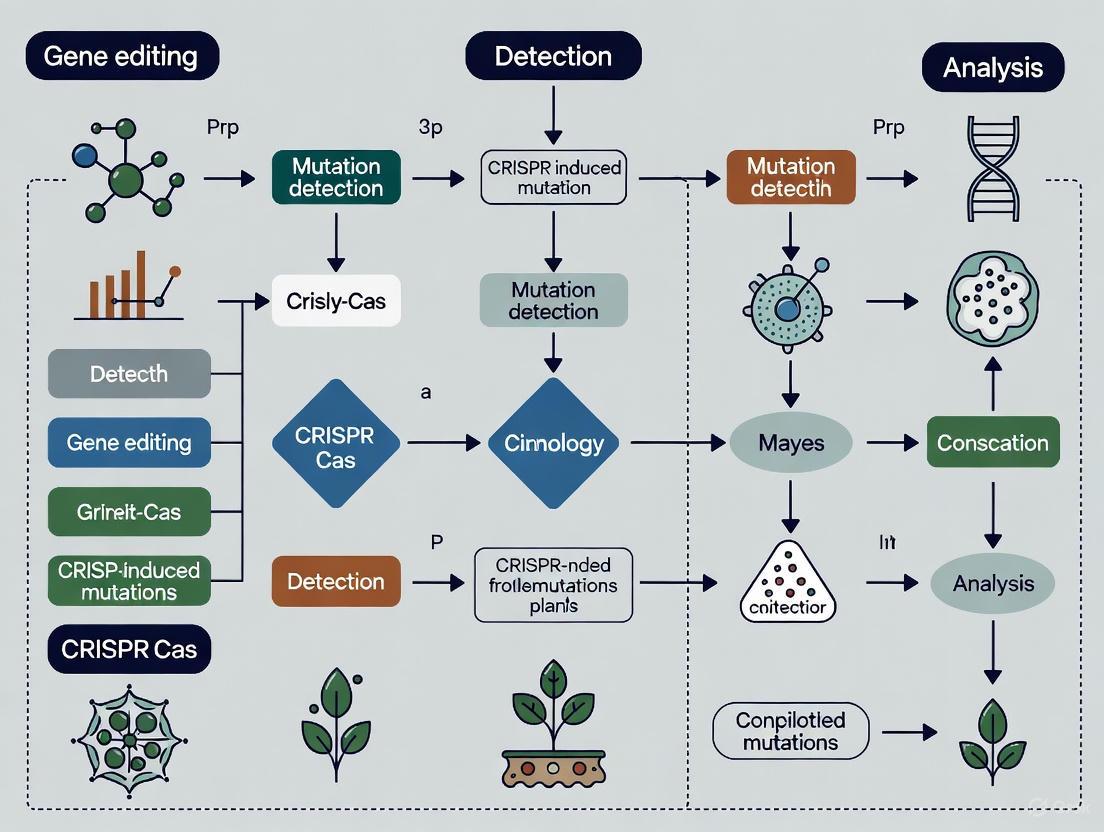

The following diagrams illustrate the key molecular pathways involved in CRISPR-mediated DNA repair, providing visual reference for understanding the complex interactions between different repair mechanisms.

CRISPR-Cas9 Induced DNA Repair Pathways

DNA Damage Response Signaling in Plants

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for DNA Repair Studies

Successful investigation of DNA repair pathways in CRISPR editing requires specific research reagents and materials. The following table comprehensively lists essential tools for studying these mechanisms in plant and other biological systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Studying DNA Repair Pathways in CRISPR Editing

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | Cas9, Cpf1 (Cas12a), Cas12b | DSB induction at target sites | Different PAM requirements, cleavage patterns (staggered vs blunt ends) |

| Pathway Inhibitors | Alt-R HDR Enhancer V2 (NHEJi), ART558 (POLQ/MMEJi), D-I03 (Rad52/SSAi) | Modulate specific repair pathways | Enhance HDR efficiency by 2-3 fold when used strategically [5] |

| Donor Templates | dsDNA with homology arms, ssODNs | Template for HDR-mediated precise editing | Homology arm length (90-1000 bp), sequence-validated designs |

| Detection Tools | T7E1 assay, RFLP analysis, NGS platforms, Sanger sequencing | Identify and quantify editing outcomes | Different sensitivity, throughput, and cost profiles |

| Cell/Plant Models | RPE1 cells, Arabidopsis, tomato, rice protoplasts | Experimental systems for editing | Variable editing efficiencies, transformation protocols |

| Delivery Methods | Electroporation, PEG-mediated transformation, Agrobacterium, viral vectors | Introduce editing components into cells | Different efficiency, cost, and technical requirements |

| Analysis Software | knock-knock, CRISPResso2, TIDE | Classify and quantify editing outcomes | Specific algorithms for different repair patterns |

The selection of appropriate reagents depends heavily on the specific research goals. For plant systems, the development of transgene-free editing systems using ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes has gained significant traction, as evidenced by recent advances in crops like citrus, where an in planta genome editing system (IPGEC) enables transgene-free, biallelic editing without tissue culture [8]. Similarly, virus-induced genome editing (VIGE) systems using tobacco rattle virus (TRV) to deliver compact editing enzymes like TnpB have shown promise for achieving heritable edits in tomato [8].

For pathway modulation, the timing of inhibitor application proves critical. Research indicates that treatment duration of 24 hours immediately following CRISPR delivery optimally enhances HDR efficiency, as this window captures the primary period when HDR occurs after Cas9-induced DSBs [5]. Combining multiple inhibitors (e.g., NHEJ and SSA inhibition) can further improve precise editing outcomes by addressing the complex interplay between different repair pathways [5].

The intricate interplay between NHEJ, HDR, and alternative repair pathways in CRISPR-mediated editing has profound implications for detecting and characterizing mutations in plant research. The predominance of error-prone repair pathways like NHEJ means that detection methods must be capable of identifying diverse mutational outcomes beyond precise integrations—including INDELs, deletions flanked by microhomology, and larger genomic rearrangements.

Effective mutation detection in plant CRISPR research requires a multi-faceted approach that considers the quantitative distribution of different repair outcomes. While HDR-based precise edits typically represent a minority of total editing events, their detection requires sensitive methods such as restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) or allele-specific PCR. In contrast, the more abundant NHEJ-mediated mutations can be detected using higher-throughput but less precise methods like T7E1 assay or fragment analysis. For comprehensive characterization of the full spectrum of editing outcomes, next-generation sequencing approaches remain the gold standard, albeit at higher cost and computational requirements [5] [4].

Recent advances in understanding alternative repair pathways like MMEJ and SSA further complicate the detection landscape, as these pathways produce distinct mutational signatures that may be misinterpreted or overlooked with standard detection methods. The demonstration that SSA suppression reduces asymmetric HDR—a specific imprecise integration pattern where only one side of donor DNA is precisely integrated—highlights the need for detection methods with single-nucleotide resolution to accurately characterize editing outcomes [5].

As CRISPR applications in plant research continue to expand—from disease resistance enhancement in crops like rice and tomato to nutritional quality improvement in barley and soybean [8]—the development of refined detection methods that account for the complex behaviors of DNA repair pathways will be essential for accurate characterization of edited lines and regulatory compliance. The strategic modulation of repair pathways through chemical inhibitors or other approaches offers promising avenues for improving the efficiency of desired edits, but simultaneously demands increasingly sophisticated detection capabilities to verify both on-target precision and off-target safety.

The advent of CRISPR-Cas technologies has revolutionized plant functional genomics and crop improvement by enabling precise modifications to DNA sequences. A comprehensive understanding of the spectrum of mutations induced by different CRISPR-Cas systems—ranging from small insertions and deletions (indels) to base edits and large deletions—is essential for selecting the appropriate tools for specific applications. This knowledge is equally critical for choosing effective detection methods to identify and characterize these genetic changes. The complex nature of plant genomes, particularly polyploid species like wheat, further underscores the need for sensitive and accurate screening techniques [9]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of CRISPR-induced mutations in plants, detailing their molecular characteristics, the technologies that generate them, and the experimental protocols required for their detection and validation.

CRISPR systems generate a diverse array of mutations through distinct molecular mechanisms. The choice of CRISPR tool directly determines the type and size of the genetic alteration, which in turn influences the strategic approach for mutation detection.

Table 1: Spectrum of CRISPR-Induced Mutations in Plants

| Mutation Type | CRISPR System | Molecular Mechanism | Typical Size Range | Primary Applications in Plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Indels | Cas9, Cas12a | NHEJ repair of DSBs | 1 bp to <10 bp (Cas9); 6-14 bp (Cas12a) [10] | Gene knockouts, loss-of-function mutations [11] |

| Base Edits | Base editors (Cytidine/ Adenosine deaminase fusions) | Direct chemical conversion of bases without DSBs | Single nucleotide changes | Amino acid substitutions, introducing herbicide resistance [11] |

| Large Deletions | Exonuclease-fused Cas9/Cas12a, paired gRNAs | Exonuclease resection or deletion between distant cuts | >15 bp to hundreds of bp [10] | cis-regulatory element editing, noncoding RNA knockout [10] |

| Precise Insertions | Prime editing, HDR-based approaches | Reverse transcription from pegRNA or donor template | Up to 15 bp demonstrated in rice [11] | Specific amino acid changes, small tag insertions |

The following diagram illustrates the mechanistic pathways leading to these different mutation types:

Mutation Detection Methods: Comparative Analysis

Detecting CRISPR-induced mutations requires methods with varying levels of sensitivity, scalability, and resolution. The optimal choice depends on the mutation type, throughput requirements, and available resources.

Table 2: Comparison of Mutation Detection Methods for CRISPR-Edited Plants

| Detection Method | Detection Principle | Sensitivity | Resolution | Throughput | Best Suited Mutation Types | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR/RNP Assay [9] | CRISPR nuclease cleavage of wild-type PCR products | High (detects 1:20 mutant:wild-type ratio) [9] | Low (presence/absence of mutation) | Medium | Small indels, large deletions | Does not identify exact sequence change |

| Sanger Sequencing [11] | Dideoxy chain termination sequencing | ~15% allele frequency [11] | Nucleotide level | Low | All mutation types | Difficult to deconvolute complex mixtures |

| Next-Generation Sequencing [11] | Massively parallel sequencing | 0.1-1% allele frequency [11] | Nucleotide level | High | All mutation types | Higher cost, bioinformatics expertise required |

| High-Resolution Melting (HRM) [12] | DNA melting curve analysis | Medium | Low (sequence variant detection) | High | SNPs, small indels | Does not identify exact sequence change |

| T7 Endonuclease I Assay [9] | Mismatch cleavage in heteroduplex DNA | Medium | Low (presence/absence of mutation) | Medium | Small indels | Cannot distinguish homozygous mutants from wild-type [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Mutation Detection

PCR/RNP Mutation Detection Protocol

The PCR/RNP method offers a highly sensitive approach for identifying edited mutations without requiring restriction enzyme sites, making it particularly valuable for polyploid plants like wheat where single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) near target sites can complicate analysis [9].

Materials Required:

- Purified CRISPR ribonucleoprotein complexes (SpCas9, FnCpf1, or AsCpf1)

- Target-specific guide RNA (sgRNA for Cas9, crRNA for Cpf1)

- PCR amplification reagents

- Agarose gel electrophoresis equipment

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the target region from plant genomic DNA using gene-specific primers flanking the edited site.

- RNP Complex Assembly: Pre-assemble CRISPR RNP complexes by incubating 500 ng of purified Cas protein with guide RNA in appropriate buffer (e.g., NEBuffer 3.1) for 10-15 minutes at room temperature.

- In Vitro Cleavage: Add the RNP complexes to purified PCR products and incubate at 37°C for 2-3 hours to allow complete digestion of wild-type sequences.

- Analysis: Separate cleavage products by agarose gel electrophoresis. Mutant alleles remain uncut due to mismatches with the guide RNA, while wild-type sequences are cleaved into smaller fragments [9].

Critical Parameters:

- RNP dosage must be optimized for each guide RNA based on its cleavage activity

- Extended incubation times (2-3 hours) ensure complete digestion of wild-type amplicons

- This method successfully detected DNA-free tagw2 mutations induced by purified TALEN protein in wheat [9]

High-Throughput Screening Protocol Using NGS and HRM

For large-scale screening of non-transgenic mutant plants, particularly in asexually propagated perennial crops, a combination of NGS and HRM provides an efficient workflow [12].

Materials Required:

- Illumina sequencing platform

- High-resolution melting instrument (e.g., LightScanner, QuantStudio)

- DNA extraction and PCR reagents

- Barcoded primers for multiplexing

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Initial Pooled Screening: Combine leaf tissue from multiple regenerated shoots (e.g., 1:41 mutant-to-wild-type ratio) and extract genomic DNA.

- Target Amplification: PCR-amplify target regions using barcoded primers for multiplexed analysis.

- NGS Analysis: Sequence pooled amplicons to ~60,000-100,000x coverage. Identify potential mutants by elevated nucleotide variant frequency (NVF) at target positions.

- HRM Validation: Screen individual plants from positive pools using HRM analysis to confirm editing events. Mutant samples show distinct melting curves compared to wild-type [12].

Critical Parameters:

- Pooling strategies must be optimized based on expected mutation rates

- NVF elevation at specific nucleotide positions indicates potential mutations

- HRM provides rapid validation without sequencing costs

Detection of Base Editing and Large Deletions

Advanced CRISPR applications require specialized detection approaches to identify precise genetic changes.

Base Editing Detection: Base editors create specific point mutations (C→T or A→G) without double-strand breaks. Detection methods include:

- High-Fidelity Cas9 variants: Can distinguish base-edited mutations from wild-type when used in PCR/RNP assays [9]

- Allele-Specific PCR: Primers specifically designed to amplify edited but not wild-type sequences

- Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism: Introduction or elimination of restriction sites by base editing

Large Deletion Detection: Exonuclease-fused CRISPR systems significantly increase deletion sizes:

- Exonuclease Fusion Systems: Fusion of exonucleases (e.g., sbcB, TREX2) to Cas9 or Cas12a increases deletion sizes >15 bp [10]

- sbcB-Cas12a Fusion: Shows 3.6-fold increase in deletions >15 bp compared to standard Cas12a [10]

- PCR Fragment Analysis: Large deletions can be detected through size differences in PCR amplicons

- Amplicon Sequencing: NGS reveals precise deletion boundaries and microhomology patterns

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful detection of CRISPR-induced mutations relies on specialized reagents and tools optimized for plant genomics applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR Mutation Detection

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Example | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | SpCas9, FnCpf1, LbCas12a | Indel induction, PCR/RNP assays | SpCas9: blunt-end DSBs; Cas12a: staggered-end DSBs with larger deletions [10] |

| High-Fidelity Cas Variants | SpCas9-HF1, HypaCas9 | Base editing detection, reduced off-target effects | Distinguish base-edited mutations from wild-type in PCR/RNP assays [9] |

| Exonuclease Fusions | sbcB-LbCas12a, TREX2-SpCas9 | Large deletion generation | sbcB fusion increases proportion of deletions >15 bp by 3.6-fold [10] |

| Detection Enzymes | T7 Endonuclease I, Purified RNP complexes | Mutation screening | T7EI detects heteroduplex mismatches; RNP cleaves only wild-type sequences [9] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | CRISPResso2, SMAP haplotype-window, TIDE | NGS/Sanger data analysis | SMAP analyzes entire read sequence as allele; TIDE deconvolutes Sanger traces [11] |

The expanding spectrum of CRISPR-induced mutations in plants—from small indels to base edits and large deletions—requires researchers to employ carefully matched detection methodologies. Each detection platform offers distinct advantages: PCR/RNP assays provide sensitivity for identifying edited lines without sequencing, NGS enables comprehensive characterization of complex editing outcomes, and HRM facilitates high-throughput screening. The choice of detection method must align with the specific CRISPR tool employed, the mutation type expected, and the throughput requirements of the research project. As CRISPR technologies continue to evolve toward more precise and complex genome modifications, detection methods will similarly advance to provide researchers with comprehensive tools for validating genetic changes in plant systems.

The Critical Role of Detection in Functional Genomics and Regulatory Compliance

In plant functional genomics, the precision of CRISPR-induced mutations is paramount. Confirming these genetic alterations reliably is a cornerstone of both rigorous research and regulatory compliance. While traditional detection methods like Sanger sequencing have been widely used, emerging CRISPR-based diagnostics offer a new paradigm in sensitivity and specificity. This guide objectively compares the performance of established and novel detection platforms, providing plant scientists with the experimental data and protocols needed to select the optimal tool for validating genome edits in their research.

Comparative Analysis of Detection Method Performance

The following table summarizes the key performance metrics of traditional and novel CRISPR-based detection methods, highlighting their applicability in plant research.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Mutation Detection Methods

| Detection Method | Theoretical Sensitivity | Time to Result | Key Advantage | Key Limitation | Suitability for Plant Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger Sequencing | N/A (Direct sequencing) | Several hours to days [13] | High accuracy for confirming exact sequence changes [13] | Time-consuming; low throughput for screening [13] | High - Gold standard for final validation |

| T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) Assay | Low (Moderate ~ >5% Indel) | Several hours [13] | Detects mismatches in heteroduplex DNA without needing sequencing [13] | Lower sensitivity; requires specialized reagents [13] | Moderate - Useful for initial, low-cost screening |

| Cleavage Assay (CA) | Information Missing | ~4-5 hours [13] | Cost-effective; uses the same RNP complex from editing for validation [13] | Primarily indicates presence/absence of edit, not its nature [13] | High - Efficient pre-screening before sequencing |

| CRISPR/Cas12-based (e.g., DETECTR) | attomolar (aM) level [14] | Hours (e.g., <2 hours) [14] | Ultra-high sensitivity; potential for in-field use [14] | Susceptible to performance drop in non-ideal conditions (e.g., high humidity) [14] | Emerging - Potentially high for pathogen detection in plants |

| CRISPR/Cas13-based (e.g., SHERLOCK) | attomolar (aM) level [14] [15] | Hours [14] [15] | Ultra-high sensitivity; specifically targets RNA [14] [15] | Susceptible to performance drop in non-ideal conditions [14] | Emerging - Potentially high for gene expression studies |

Experimental Protocols for Key Detection Methodologies

Cleavage Assay for Pre-Screening CRISPR Edits

This protocol, adapted from a mouse embryo model for plant research, offers a rapid and cost-effective method to pre-screen for successful gene editing before undertaking more extensive and expensive sequencing.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for the Cleavage Assay

| Essential Material/Reagent | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| dCas9 or Cas9 Nuclease | Core enzyme of the CRISPR system; binds or cleaves the target DNA. |

| Target-Specific crRNA | Guide RNA that directs the Cas protein to the specific genomic locus intended for editing. |

| tracrRNA | Universal RNA that hybridizes with crRNA to form the functional guide RNA (gRNA). |

| Nuclease-Free Duplex Buffer | Provides the ideal ionic conditions for the annealing of crRNA and tracrRNA. |

| Opti-MEM I Medium | A low-serum, specialized medium used for diluting and handling RNP complexes. |

| Agarose Gel Electrophoresis System | Standard molecular biology setup to separate and visualize DNA fragments by size. |

Detailed Workflow:

- gRNA Preparation: In a nuclease-free tube, mix equal amounts (e.g., 0.5 µL each of 100 µM stocks) of crRNA and tracrRNA with 49 µL of Nuclease-Free Duplex Buffer. Anneal the RNA by incubating at 95°C for 3 minutes, then allow it to cool slowly to room temperature over 30 minutes to form the guide RNA (gRNA) complex [13].

- RNP Complex Formation: Dilute a commercial Cas9 protein (e.g., NLS-Cas9) to 1 µM concentration using Opti-MEM I medium. Combine the diluted Cas9 with the annealed gRNA to form the Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex [13].

- Post-Editing Genomic DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from the CRISPR-edited plant tissue (e.g., leaf disc, callus) using a standard CTAB or silica-column based method. Resuspend the purified DNA in nuclease-free water or TE buffer [13].

- Cleavage Reaction: Set up a new reaction mixture containing the same RNP complex used for the initial genetic editing. Add the extracted genomic DNA from the previous step as the substrate for this assay. Incubate the reaction at 37°C for 30-60 minutes to allow the RNP to cleave any unmodified, wild-type DNA targets [13].

- Result Analysis: Analyze the reaction products via agarose gel electrophoresis. The persistence of an intact DNA band indicates a successfully modified target locus that the RNP can no longer recognize or cleave. The disappearance of the band, or appearance of cleavage fragments, suggests the presence of unedited wild-type alleles [13].

CRISPR-Cas13-based SHERLOCK for RNA Detection

This protocol leverages the collateral activity of Cas13 to detect specific RNA transcripts, which can be used in plant research to validate the knockdown of a gene or the expression of a newly introduced trait.

Detailed Workflow:

- Sample RNA Extraction: Isolate total RNA from the plant tissue of interest using a standard method, ensuring RNA integrity and purity.

- Target Pre-amplification (Optional but common): To achieve high sensitivity, the RNA target is first converted to cDNA via reverse transcription. This is followed by an isothermal amplification step (e.g., RPA or LAMP) that incorporates a T7 promoter. The amplified DNA is then transcribed into RNA, creating numerous copies of the target sequence [15].

- Cas13 Detection Reaction: The amplified RNA is incubated with a Cas13-gRNA complex programmed to recognize the target sequence and a quenched fluorescent reporter RNA. Upon target binding, Cas13's collateral RNase activity is activated, cleaving the reporter molecules and producing a fluorescent signal [15].

- Signal Readout: The fluorescence can be measured quantitatively using a plate reader or visually assessed using a lateral flow dipstick for a simple yes/no result, making it adaptable for various settings [15].

Molecular Mechanisms of CRISPR-Based Detection

The power of CRISPR diagnostics lies in the specific molecular mechanisms of different Cas enzymes. Cas9 is primarily used for editing due to its cis-cleavage (target-specific) activity. In contrast, Cas12 and Cas13 are favored for diagnostics due to their trans-cleavage (collateral) activity, which provides signal amplification [14] [15].

The selection of a detection method is a critical decision that balances sensitivity, throughput, cost, and regulatory needs. For the final confirmation of a plant's genetic sequence, Sanger sequencing remains the definitive standard. However, for efficient screening and potentially for monitoring gene expression changes, newer methods like the Cleavage Assay and CRISPR-based diagnostics like SHERLOCK offer compelling advantages in speed and sensitivity. As plant science continues to advance, integrating these robust detection protocols will be essential for accelerating functional genomics and meeting the evidentiary standards for regulatory compliance.

Navigating Global Regulatory Frameworks for Gene-Edited Plants (SDN-1, SDN-2, SDN-3)

Gene-editing technologies, particularly CRISPR-based systems, have revolutionized plant breeding by enabling precise genomic modifications. These edits are commonly categorized into three main types based on the mechanism involved: SDN-1 (Site-Directed Nuclease 1), which introduces random mutations via non-homologous end joining without a repair template; SDN-2, which uses a supplied DNA template to create specific, predefined nucleotide changes through homology-directed repair; and SDN-3, which introduces larger DNA sequences, such as entire genes, into a specific genomic location [16].

The global regulatory landscape for these technologies is complex and diverse, with significant implications for research, commercialization, and international trade. This guide objectively compares how different regulatory frameworks approach these distinct categories of gene-edited plants, with particular emphasis on the detection methodologies required for compliance and verification. Understanding these frameworks is essential for researchers, developers, and policymakers navigating the pathway from laboratory discovery to commercial application [17].

Global Regulatory Approaches for SDN-1, SDN-2, and SDN-3

International regulations for gene-edited plants have evolved with considerable divergence, largely influenced by pre-existing governance of genetically modified organisms (GMOs). The regulatory approaches can be classified into four main categories based on their stringency and methodology [16].

Table 1: Classification of Global Regulatory Approaches for Gene-Edited Plants

| Approach | How Product is Treated | Applied Regulatory Oversight | Representative Countries/Regions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approach 1 | Regulated as GMO | Full GMO regulations applied | European Union (current), New Zealand [16] |

| Approach 2 | Regulated as GMO | Simplified GMO regulations | China, United Kingdom (under consideration) [18] [16] |

| Approach 3 | Not considered GMO | Exempt from GMO regulations, but requires official confirmation | Japan, Argentina, India, Philippines [18] [16] |

| Approach 4 | Not considered GMO | Exempt from GMO regulations, no prior confirmation required | United States (USDA), Australia [18] [16] |

A crucial differentiator among these frameworks is whether they are process-triggered (focused on the method used to create the plant) or product-triggered (focused on the characteristics of the final plant) [17]. This fundamental distinction explains much of the global variation in regulating SDN-1, SDN-2, and SDN-3 applications.

Table 2: Specific Regulatory Treatment of SDN Types Across Jurisdictions

| Country/Region | SDN-1 | SDN-2 | SDN-3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States (USDA) | Generally exempt from regulation [19] | Exempt if using a template from the plant's gene pool [19] | Subject to regulation [16] |

| European Union | Regulated as GMO [16] | Regulated as GMO [16] | Regulated as GMO [16] |

| Japan | Exempt after confirmation [16] | Exempt after confirmation (case-by-case) [16] | Regulated as GMO [16] |

| Argentina | Exempt after confirmation [16] | Exempt after confirmation (case-by-case) [16] | Regulated as GMO [16] |

| India | Exempt if no foreign DNA [17] | Exempt if no foreign DNA [17] | Regulated as GMO [17] |

| China | Simplified regulation [18] [17] | Simplified regulation [18] [17] | Regulated as GMO [17] |

SDN-3 applications, which involve the insertion of foreign DNA, are almost universally regulated as GMOs across all major jurisdictions [16]. The greatest regulatory divergence lies in the treatment of SDN-1 and SDN-2 products, particularly when the edits mimic what could occur naturally or through conventional breeding, and when the final product contains no foreign DNA [17].

Figure 1: A simplified decision pathway for the regulation of gene-edited plants, showing how the classification (SDN-1, SDN-2, SDN-3) and the presence of foreign DNA or novel traits trigger different regulatory outcomes in various global frameworks.

Detection Methods for CRISPR-Induced Mutations

Robust detection and verification methods are fundamental to enforcing regulations and ensuring product transparency. The technical challenge varies significantly with the type of edit, influencing regulatory feasibility.

Case Study: Detecting a Single-Base Deletion in Tomato

A comprehensive detection strategy for an SDN-1 type gene-edited tomato (with a single-base pair deletion in the SlPL gene for improved shelf life) demonstrates a multi-tiered workflow [20].

Experimental Protocol:

- Initial Screening (LAMP/PCR): Rapid screening via Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) and conventional Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) assays targeting the Cas9 protein gene to identify plants that have undergone the editing process at an early stage [20].

- Verification (Multiplex Real-time PCR): A multiplex TaqMan real-time PCR assay using dual fluorescently labelled probes simultaneously targets the edited and wild-type sequences. This method operates on a principle of negative selection, where the presence of the mutation is confirmed by the absence of a fluorescent signal from the wild-type probe. This sensitive method can detect edits at a level of 0.1% and verifies the specific single-base deletion [20].

- Transgenic Element Check (Real-time PCR): To confirm the non-transgenic nature of the SDN-1 edited line and distinguish it from SDN-3 products, a final real-time PCR is performed targeting common genetic elements (e.g., promoters, terminators) found in globally approved transgenic GM tomato events [20].

Figure 2: A tiered experimental workflow for the detection and verification of an SDN-1 type gene edit in tomato, from initial screening to final confirmation of its non-transgenic status [20].

Comparison of Detection Methodologies

The applicability and complexity of detection methods depend on the nature of the genetic modification.

Table 3: Comparison of Detection Methods for Different SDN Types

| SDN Type | Example Methods | Key Challenge | Distinguishability from Natural Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDN-1 | PCR + Capillary Electrophoresis, NGS, RPA | Detecting small InDels without a known reference | Often indistinguishable [20] |

| SDN-2 | PCR-RFLP, Sanger Sequencing, NGS | Verifying a specific, precise nucleotide change | Often indistinguishable [20] |

| SDN-3 | Quantitative PCR (qPCR), LAMP, ELISA | Detecting the presence of foreign genetic elements | Easily distinguishable [20] |

A significant challenge in regulating SDN-1 and SDN-2 products is that the resulting genetic changes are often indistinguishable from natural mutations or those achieved through conventional mutagenesis. This creates a technical and regulatory dilemma, as it makes process-based traceability and enforcement functionally impossible in many cases [17]. In contrast, SDN-3 products, which contain foreign DNA, are readily detectable with well-established methods.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Progress in gene editing and the development of compliant plant varieties rely on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Gene Editing and Detection

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Creates targeted double-strand breaks in DNA. | Generating SDN-1 knockouts in crops like wheat and tomato [8] [21]. |

| CRISPR-dCas9 Activators | Regulates gene expression without altering DNA sequence (CRISPRa). | Gain-of-function studies; activating endogenous disease resistance genes [3]. |

| Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | Delivers editing components in vivo. | Used in medical applications; potential for plant delivery systems [22]. |

| TaqMan Probes | Fluorescently labelled probes for quantitative real-time PCR. | Sensitive verification of single-base edits in tomato [20]. |

| LAMP Assay Kits | Isothermal amplification for rapid, equipment-light detection. | Initial screening for the presence of Cas9 transgenes [20]. |

| Agrobacterium Strains | Delivers T-DNA containing editing machinery into plant cells. | Creating transgene-free edited citrus through an in planta system [8]. |

The global regulatory landscape for gene-edited plants is defined by a fundamental tension between process-based and product-based approaches, leading to a "patchwork" of international regulations [16]. While SDN-3 products are consistently regulated as GMOs worldwide, the treatment of SDN-1 and SDN-2 products varies dramatically, with trends showing a move toward more product-based, flexible frameworks in many countries [16] [17].

The technical capacity for detection plays a critical role in this landscape. Reliable methods, like the multiplex real-time PCR developed for tomato, are essential for regulatory compliance, verification of claims, and food traceability [20]. However, the inherent indistinguishability of many small edits from natural mutations presents a core challenge for process-based regulatory systems, suggesting that a product-based, evidence-driven approach may offer a more scientifically valid and practicable path forward for SDN-1 and SDN-2 technologies [17]. This ongoing evolution underscores the need for continued dialogue and efforts toward international harmonization to balance innovation, safety, and trade.

A Practical Guide to Mutation Detection Techniques: From Lab to Validation

Conventional and High-Resolution Melting (HRM) PCR for Initial Screening

In the rapidly evolving field of plant genetic research, the precise detection of CRISPR-induced mutations presents a significant methodological challenge. As CRISPR technologies advance, enabling increasingly sophisticated edits from simple knockouts to precise nucleotide substitutions, the demand for efficient, accurate, and accessible genotyping methods has grown substantially [3]. While next-generation sequencing (NGS) offers comprehensive detail, its cost and complexity often render it impractical for the initial screening of large plant populations. Consequently, PCR-based methods remain the workhorse for preliminary identification of edited lines [23].

Among these, Conventional PCR and High-Resolution Melting (HRM) PCR have emerged as two prominent techniques for initial mutation screening. Conventional PCR, typically analyzed by gel electrophoresis, identifies edits based on amplicon size differences, while HRM PCR detects sequence variations by analyzing the thermal denaturation profile of PCR products in the presence of saturating DNA dyes [24] [25]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two methods, focusing on their performance, protocols, and suitability for detecting CRISPR-induced mutations in plant research.

Technical Comparison: Conventional PCR vs. HRM PCR

The following table summarizes the core characteristics and performance metrics of Conventional PCR and HRM PCR for mutation screening, drawing on data from clinical, microbiological, and genetic studies that provide measurable outcomes.

Table 1: Performance Comparison for Mutation Screening

| Feature | Conventional PCR | High-Resolution Melting (HRM) PCR |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Amplification of target DNA region followed by size-based separation via gel electrophoresis. | Amplification with saturating DNA dyes, followed by high-resolution analysis of dissociation curves [24]. |

| Mutation Detection Basis | Indels causing significant size changes; cannot detect single-nucleotide changes. | Sequence composition (GC content, length, heterozygosity); sensitive to single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) [24] [26]. |

| Typical Sensitivity | Lower; limited by gel resolution. Often requires >5-10% mutant allele in a wild-type background [27]. | High; can reliably detect down to 5% mutant allele, with some assays reporting limits of 0.8%-5% depending on optimization [27] [28]. |

| Typical Specificity | Moderate; dependent on primer specificity and gel resolution. | Very High; a meta-analysis for EGFR mutation detection reported a pooled specificity of 0.99 [95% CI: 0.99–0.99] [28]. |

| Workflow & Hands-on Time | Longer; requires post-PCR handling (gel casting, loading, staining, imaging) which is time-consuming and increases contamination risk. | Shorter; closed-tube method. PCR and analysis are performed in the same tube, minimizing post-PCR steps and contamination risk [24] [29]. |

| Cost & Accessibility | Lower initial instrument cost; widely accessible. | Higher initial instrument cost (requires real-time PCR with HRM capability); reagents (saturating dyes) are moderately priced [25]. |

| Key Advantage | Simple, low-cost, and provides a direct visual result. | Fast, closed-tube, high sensitivity for SNVs, and non-destructive [24] [28]. |

| Key Limitation | Low throughput, poor sensitivity for small indels and SNVs, and cannot differentiate all sequence variations. | Requires optimized protocols and controls; performance can be affected by DNA quality and concentration [27] [29]. |

Experimental Protocols for Plant Genotyping

This section outlines detailed methodologies for applying both techniques to screen for CRISPR-induced mutations in plant samples.

Protocol 1: Conventional PCR with Gel Electrophoresis

This protocol is adapted from standard nested PCR approaches used in pathogen detection [30].

Step 1: DNA Extraction

- Use a commercial kit (e.g., Qiagen DNeasy Plant Mini Kit) to extract high-quality genomic DNA from leaf tissue of CRISPR-treated and wild-type control plants.

- Quantify DNA concentration using a spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop) and normalize all samples to a working concentration (e.g., 10-50 ng/µL).

Step 2: First-Round PCR

- Prepare a 20 µL reaction mixture containing: 1x PCR buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl₂, 200 µM dNTPs, 200 nM of each forward and reverse primer (flanking the CRISPR target site), 1U of Taq DNA polymerase, and ~10-50 ng of plant DNA template.

- Perform PCR amplification with the following cycling conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 45 s, annealing at 60°C for 45 s, extension at 72°C for 70 s; and a final elongation at 72°C for 10 min [30].

Step 3: Nested PCR

- Dilute the first-round PCR product 1:1000.

- Prepare a second 20 µL reaction mixture similar to the first, using 3 µL of the diluted product as the template and nested primers that bind internally to the first amplicon. This increases specificity and yield.

- Use similar cycling conditions: 95°C for 4 min; 35 cycles of 94°C for 20 s, 60°C for 20 s, 72°C for 45 s; final extension at 72°C for 10 min [30].

Step 4: Gel Electrophoresis & Analysis

- Mix 5-10 µL of the nested PCR product with DNA loading dye and load onto a 2-3% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide or a safer alternative like GelRed.

- Run the gel alongside a DNA ladder at a constant voltage (e.g., 100V) until sufficient separation is achieved.

- Visualize the gel under UV light. CRISPR-induced indels will appear as bands of different sizes compared to the wild-type control.

Protocol 2: HRM PCR Analysis

This protocol is based on optimized HRM applications for SNP genotyping and species identification [30] [24] [26].

Step 1: DNA Extraction and Quantification

- Follow the same procedure as in Protocol 1. Consistent DNA quality and accurate quantification are critical for reproducible HRM results.

Step 2: HRM PCR Reaction Setup

- Prepare reactions in a dedicated real-time PCR plate. A 20 µL reaction should contain: 1x HRM-capable PCR master mix, a saturating dsDNA dye (e.g., EvaGreen or SYTO 9), 200 nM of each forward and reverse primer (designed to produce a 50-150 bp amplicon spanning the edit site), and ~10-20 ng of plant DNA.

- Include wild-type control DNA and a no-template control (NTC) in every run. For homozygous variant discrimination, consider adding a known reference genotype to samples to force heteroduplex formation [24].

Step 3: Real-Time PCR Amplification and Melting

- Run the plate on a real-time PCR instrument with HRM capability (e.g., Roche LightCycler 96, Applied Biosystems QuantStudio).

- Use the following cycling protocol: Polymerase activation at 95°C for 10 min; 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s and annealing/extension at 60°C for 1 min (acquire fluorescence).

- After amplification, proceed directly to the HRM step: Denature at 95°C for 1 min, re-anneal at 40°C for 1 min, and then continuously heat from 65°C to 95°C with a ramp rate of 0.02°C/s while acquiring high-resolution fluorescence data [30] [25].

Step 4: Melting Curve Analysis

- Use the instrument's HRM software to normalize and shift the melting curves.

- Analyze the data using difference plots, which highlight subtle curve shape differences compared to the wild-type control. Samples with CRISPR edits will display distinct melting curve profiles, allowing for genotyping.

The workflow below visualizes the key procedural differences between the two methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of these screening methods relies on specific reagents and instruments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Screening | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Saturating DNA Dyes (e.g., EvaGreen, SYTO 9) | Fluorescently label dsDNA during HRM PCR without inhibiting PCR or redistribating during melting. Essential for generating high-fidelity melting curves [24]. | Distinguishing between wild-type and edited SlWRKY29 gene in tomato based on melting temperature (Tm) shifts [3]. |

| HRM-Capable Real-Time PCR System | Instrument platform that provides precise temperature control and high-resolution fluorescence data capture during the melting phase. | Roche LightCycler 96 used for malaria species differentiation; Applied Biosystems QuantStudio series [30] [25]. |

| Optimized Primer Pairs | Short, specific primers generating amplicons of 50-150 bp. Critical for HRM sensitivity, as shorter amplicons maximize Tm differences from single-base changes [24]. | Primers targeting the Strumpellin gene for discriminating Leishmania species via HRM [26]. Primers designed close to the CRISPR target site. |

| DNA Size Ladder | A molecular weight marker for gel electrophoresis, allowing estimation of PCR product size and identification of size shifts caused by indels. | Used in conventional nested PCR to confirm the expected size of amplicons and detect larger insertions or deletions [30]. |

| Internal Temperature Standards | Synthetic oligonucleotides with defined melting temperatures used in highly multiplexed HRM assays to calibrate and normalize temperature data across wells, improving genotyping accuracy [24]. | Improving genotyping accuracy for lactose intolerance (LCT) SNP analysis by bracketing the target Tm [24]. |

Both Conventional PCR and HRM PCR are viable for the initial screening of CRISPR-induced mutations in plants, yet they serve different needs and resource environments. Conventional PCR with gel electrophoresis remains a valuable, low-cost tool for detecting large indels when the budget is constrained and the required sensitivity is low. In contrast, HRM PCR offers a superior, closed-tube solution for high-throughput settings where sensitivity, specificity, and the ability to detect single-nucleotide variants are paramount. Its application is particularly crucial as CRISPR technologies advance beyond simple knockouts to facilitate precise base editing, where the screening method must be capable of discerning the most subtle genetic alterations. The choice between them ultimately depends on the specific editing objectives, scale of the project, and available laboratory resources.

In plant genome editing research, accurately detecting and quantifying CRISPR-induced mutations is crucial for evaluating the efficiency of guide RNAs (gRNAs) and the success of editing experiments [31]. Among the various techniques available, enzyme-based detection methods remain widely used due to their accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and minimal equipment requirements. The Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) assay and the T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) assay are two fundamental enzyme-based techniques for identifying successful genome editing events [32]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two methods, situating them within the broader context of detection methods for CRISPR-induced mutations in plant research, and summarizes key experimental data to help researchers select the appropriate technique for their specific applications.

Principle of Operation and Workflow

T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) Assay

The T7EI assay operates by recognizing and cleaving mismatched DNA heteroduplexes formed when edited and wild-type DNA strands hybridize [32]. After CRISPR-Cas9 induces a double-strand break, the cell's error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) repair pathway often introduces small insertions or deletions (indels) at the target site. When PCR amplicons from this heterogeneous pool of DNA are denatured and reannealed, heteroduplexes form between wild-type and indel-containing strands, creating structural mismatches. The T7EI enzyme specifically recognizes and cleaves these mismatched sites, producing DNA fragments of predictable sizes that can be separated and visualized via gel electrophoresis [33].

Experimental Protocol for T7EI Assay:

- DNA Extraction: Isolate genomic DNA from CRISPR-treated plant tissue (e.g., agroinfiltrated Nicotiana benthamiana leaves) [31].

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the target region using gene-specific primers that flank the CRISPR target site [32].

- Heteroduplex Formation: Denature and reanneal the PCR products to allow formation of heteroduplexes between wild-type and mutant strands.

- T7EI Digestion: Incubate the heteroduplex DNA with T7 Endonuclease I enzyme (commercially available from suppliers such as New England Biolabs) [32].

- Analysis: Separate the digestion products using agarose or polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Stain with Ethidium Bromide or GelRed and image the gel to visualize cleavage bands [32].

- Efficiency Calculation: Quantify editing efficiency by comparing band intensities using densitometric analysis software with this formula: Editing efficiency (%) = [1 - √(1 - (b + c)/(a + b + c))] × 100, where a is the integrated intensity of the undigested PCR product, and b and c are the intensities of the cleavage products [32].

Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) Assay

The RFLP assay detects CRISPR edits through the disruption or creation of restriction enzyme recognition sites at the target locus [33]. Successful genome editing alters the DNA sequence, which can eliminate a pre-existing restriction site or create a novel one. After PCR amplification of the target region, digestion with an appropriate restriction enzyme produces different fragment patterns for wild-type and edited alleles when separated by gel electrophoresis. Traditional RFLP is limited by the natural occurrence of restriction sites, but this limitation can be overcome using RGEN-mediated RFLP (using CRISPR-derived RNA-guided engineered nucleases), where the Cas9-gRNA complex itself serves as the restriction enzyme [33].

Experimental Protocol for RFLP Assay:

- DNA Extraction and PCR: Extract genomic DNA and amplify the target region as described for the T7EI assay [31].

- Restriction Digestion: Incubate PCR products with an appropriate restriction enzyme (for conventional RFLP) or with pre-assembled RGEN complexes (for RGEN-RFLP) [33]. For RGEN-RFLP, complex recombinant Cas9 protein with in vitro transcribed guide RNAs complementary to the DNA sequences of interest.

- Electrophoresis: Separate digested fragments by gel electrophoresis and visualize as above.

- Efficiency Calculation: Editing efficiency is calculated based on the ratio of digested to undigested fragments. For heterozygotes, expect three bands (two cleaved and one uncleaved); for homozygous mutants, expect complete loss of cleavage [33].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow and fundamental difference in how these two assays detect mutations:

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Comparison of Key Parameters

When benchmarked against targeted amplicon sequencing (AmpSeq) as the gold standard, both RFLP and T7EI assays show distinct performance characteristics [31]. The following table summarizes their comparative performance based on recent plant genome editing studies:

Table 1: Performance Comparison Between T7EI and RFLP Assays

| Parameter | T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) Assay | Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Recognizes and cleaves mismatched heteroduplexes [32] | Detects loss or creation of restriction enzyme sites [33] |

| Accuracy | Semi-quantitative, tends to underestimate efficiency, especially at high editing rates [31] [33] | More accurate for detecting specific mutations, particularly with RGEN-RFLP [33] |

| Sensitivity | Limited sensitivity for low-frequency edits (<5%) and homozygous biallelic mutants [31] [33] | Can detect homozygous mutants; sensitivity depends on enzyme efficiency [33] |

| Quantification Capability | Semi-quantitative with densitometric analysis [32] | Semi-quantitative to quantitative with appropriate controls [33] |

| Throughput | Medium, requires optimization of heteroduplex formation [31] | Medium to high, especially for known mutations [33] |

| Cost | Low to moderate [31] | Low (conventional RFLP) to moderate (RGEN-RFLP) [31] [33] |

| Advantages | Does not require sequence-specific restriction sites; works for various indels [32] | Distinguishes homozygous from heterozygous mutants; not affected by sequence polymorphisms [33] |

| Limitations | Cannot detect homozygous biallelic mutants with identical sequences; affected by sequence polymorphisms [33] | Limited by availability of restriction sites (conventional RFLP) [33] |

Key Experimental Findings

Comparative analysis in plant systems reveals significant methodological differences. A comprehensive benchmarking study analyzing 20 sgRNA targets in Nicotiana benthamiana found that both T7EI and RFLP showed variations in quantified editing frequency when compared to the AmpSeq benchmark [31]. The study noted that T7EI assays are particularly challenged when analyzing heterogeneous plant populations resulting from transient expression-based editing approaches [31].

RGEN-RFLP analysis demonstrates a critical advantage over T7EI: it successfully distinguishes compound heterozygous (-/-) clones from heterozygous (+/-) clones, while T7EI fails to make this distinction [33]. In quantitative experiments mixing wild-type and mutant DNA, RFLP cleavage was proportional to the wild-type to mutant ratio, while T7EI correlation was poor, especially at high mutation percentages where complementary mutant sequences form homoduplexes [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of T7EI and RFLP assays requires specific reagents and materials. The following table details essential components for establishing these methods in plant genome editing research:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Enzyme-Based Detection Methods

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application in Both/ Specific Assays |

|---|---|---|

| PCR Reagents (polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, primers) | Amplification of target genomic region surrounding CRISPR cut site | Both assays [31] [32] |

| T7 Endonuclease I | Recognizes and cleaves mismatched heteroduplex DNA | T7EI assay specifically [32] |

| Restriction Enzymes or RGEN Components (Cas9 protein, guide RNA) | Digests DNA at specific recognition sequences | RFLP assay (conventional or RGEN-based) [33] |

| Gel Electrophoresis System (agarose, buffers, staining dye, imaging) | Separation and visualization of DNA fragments | Both assays [32] [33] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from plant tissues | Both assays [31] |

| Densitometry Software | Quantification of band intensities for efficiency calculation | Both assays [32] |

Both T7EI and RFLP assays provide valuable, accessible methods for initial screening of CRISPR editing efficiency in plant research. The T7EI assay offers the advantage of not requiring specific restriction sites and can detect various indels, making it suitable for preliminary screening. However, it has significant limitations in accurately quantifying editing efficiency and cannot detect homozygous biallelic mutants with identical sequences. The RFLP assay, particularly in its RGEN-based format, provides more reliable detection of different zygosity states and is not confounded by sequence polymorphisms near the target site. When selecting between these methods, researchers should consider the specific requirements of their experiment, including the need for quantitative accuracy, sensitivity threshold, and available resources. For critical applications requiring precise quantification, these enzyme-based methods are increasingly being supplemented or replaced by more quantitative approaches such as digital PCR or targeted amplicon sequencing [31].

The rapid advancement of CRISPR technologies in plant research has necessitated the development of robust, sensitive, and specific detection methods for verifying editing success. This guide compares the performance of multiplex TaqMan real-time PCR against other prominent techniques for identifying single-nucleotide mutations. While TaqMan assays offer proven quantitative capabilities and compatibility with standardized protocols, emerging data-driven approaches and alternative chemistries present compelling advantages for complex multiplexing and cost-effective applications. The choice of method ultimately depends on the specific requirements of the research, including the need for quantification, throughput, scalability, and the number of targets detected simultaneously.

The precision of CRISPR-Cas9 and other new genomic techniques (NGTs) allows for the creation of plant variants with targeted single-nucleotide changes, such as point mutations and small indels [34]. However, these subtle modifications present a significant challenge for molecular detection. Unlike traditional transgenesis, which introduces foreign DNA sequences, the edits in site-directed nuclease (SDN)-1 and SDN-2 category plants can be as small as a single base pair, making them difficult to distinguish from wild-type sequences or natural variations [35] [34]. Robust detection and identification methods are crucial for multiple aspects of plant research: validating editing success in early transformation events, screening subsequent generations for stable inheritance, and complying with regulatory requirements for traceability in many countries [35] [34].

Among the available techniques, probe-based real-time PCR methods, particularly multiplex TaqMan assays, are widely used due to their robustness and quantitative nature. This guide objectively compares the performance of advanced multiplex TaqMan protocols with other detection alternatives, providing a clear framework for scientists to select the optimal method for their specific application.

Methodological Comparison of Detection Techniques

Various methods have been developed to identify CRISPR-induced mutations, each with distinct strengths and limitations. The table below provides a high-level comparison of the most prominent techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Detection Methods for CRISPR-Induced Mutations

| Method | Key Principle | Best For | Multiplexing Capacity | Sensitivity & Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiplex TaqMan qPCR | Hydrolysis probes (e.g., TaqMan) with different fluorescent dyes enable simultaneous target detection [36] [37]. | Quantitative detection and validation of known, specific SNPs or indels [34]. | Moderate (up to 4-6 targets per reaction with distinct dyes) [38] [37]. | High specificity from dual priming (primers + probe); sensitivity down to ~10-100 copies [36] [34]. |

| qPCR with HRM Analysis | Intercalating dye (e.g., SYBR Green) and post-amplification melting curve analysis detect sequence-dependent Tm shifts [39] [40]. | Rapid, cost-effective screening for unknown edits within a targeted amplicon [40]. | Low (single target per reaction, but can detect multiple mutation types). | High sensitivity (can detect 1% mutant in wild-type background); specificity depends on amplicon design [40]. |

| LNA-Modified qPCR | Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) primers or probes increase hybridization stringency to discriminate single-base differences [34]. | Achieving absolute specificity for challenging single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [34]. | Low to Moderate (similar to standard TaqMan). | Very high specificity for SNP detection; successful in differentiating edited from wild-type alleles [34]. |

| Data-Driven Analysis (ML + qPCR) | Machine learning (ML) algorithms analyze amplification or melting curves to classify multiple targets beyond the fluorescence channel limit [38]. | Highly multiplexed detection using standard hardware and chemistry without probe constraints [38]. | High (limited by software, not hardware). | Promising high accuracy; performance depends on training data and model [38]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methods

Development of a Multiplex TaqMan Real-Time PCR Assay

A validated protocol for developing a multiplex TaqMan assay for mobile colistin resistance (mcr) genes illustrates a generalizable work-flow [36]:

- Primer and Probe Design: Download all available gene family sequences (e.g.,

mcr-1tomcr-10). Use sequence alignment software (e.g., CLC Sequence Viewer) to identify conserved regions without mutation points. Design primers and TaqMan-MGB probes using specialized software (e.g., Primer Express), applying degenerate bases if necessary for variant coverage [36]. - Assay Optimization: Before multiplexing, optimize each primer-probe set individually in a single-plex reaction. Use a recombinant plasmid as a template to optimize primer concentration (100–500 nM), probe concentration (50–500 nM), and annealing temperature (56.6–62.6°C). Select optimal conditions based on Ct values, fluorescence signal intensity, and amplification efficiency (ideally 90–110%) [36].

- Multiplexing and Validation: Combine optimized primer-probe sets into a single reaction. The

mcrgene assay, for example, used 8 sets of primers and probes distributed across 4 reaction tubes. Evaluate the multiplex system for sensitivity (limit of detection of 10² copies/μL), specificity (no cross-reactivity with non-target strains), and reproducibility (low intra- and inter-assay variation) [36].

qPCR-HRM for Mutation Screening in Rice

A protocol for identifying CRISPR/Cas9-edited rice plants using qPCR coupled with High-Resolution Melting (HRM) analysis offers a sensitive, non-probe-based alternative [40]:

- DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification: Extract genomic DNA from plant material. Perform qPCR with primers flanking the edited region using a saturating intercalating dye like SYTO-9.

- High-Resolution Melting: After amplification, slowly heat the amplicons from 65°C to 95°C while continuously monitoring fluorescence. The dye dissociates as the double-stranded DNA melts, producing a unique melting curve for each sequence variant.

- Analysis: Identify edited plants by comparing the melting curve profiles (shape and Tm) of samples to wild-type controls. This method can detect varied edits, including single-base insertions or deletions, with a sensitivity low enough to identify mutants in pooled samples [40].

Performance Data and Technical Considerations

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following table summarizes experimental data from published studies, providing a basis for comparing the quantitative performance of different methods.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data from Application Studies

| Method & Application | Sensitivity / Limit of Detection (LOD) | Specificity / Accuracy | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| TaqMan qPCR for NGT Arabidopsis [34] | Reliable detection with 20,000 template copies; standard curve from 20,000 to 2 copies [34]. | Challenges in absolute specificity; wild-type cross-reactivity at high Cq values [34]. | Efficiency of ~95.4%; LNA-modified primers improved SNP discrimination over unmodified TaqMan probes. |

| SYBR Green Multiplex for SARS-CoV-2 [39] | 97% specificity, 93% sensitivity vs. commercial TaqMan kit [39]. | Specificity confirmed via melting curve analysis with distinct peaks for N, E, and β-actin genes [39]. | Cost-effective alternative (~$2-6 per sample); performance validated on 180 clinical samples. |

| qPCR-HRM for CRISPR Rice [40] | Low relative limit of detection (LOD) of 1% for mutant detection [40]. | High resolution for identifying single-base indels and various mutation types [40]. | Successfully identified mutants in pooled samples; effective for high-throughput screening. |

| Dual-Probe TaqMan qPCR [41] | Comparable to single-probe assays across a 6-log dynamic range [41]. | Additive fluorescence, improving signal strength; reduced risk of false negatives from probe-binding failures [41]. | The second probe increased fluorescence signal by 15-60% without compromising Cq or efficiency. |

Technical Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram maps the logical process for selecting the most appropriate detection method based on experimental goals and constraints.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of these detection methods relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Mutation Detection Assays