Advanced CRISPR-Cas9 Protocols for Efficient Plant Transformation: A Comprehensive Guide from Design to Validation

This article provides a comprehensive guide to CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing protocols for plant transformation, tailored for researchers and scientists.

Advanced CRISPR-Cas9 Protocols for Efficient Plant Transformation: A Comprehensive Guide from Design to Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing protocols for plant transformation, tailored for researchers and scientists. It covers foundational principles of CRISPR-Cas9 mechanisms and prerequisite genomic tools, detailed methodologies for stable and transient transformation across diverse plant species, advanced strategies for optimizing editing efficiency and troubleshooting common challenges, and robust techniques for validating edits and analyzing outcomes. By integrating the latest research and practical protocols, this resource aims to empower plant biotechnologists in developing improved crops with enhanced traits such as yield, disease resistance, and stress tolerance.

Core Principles and Prerequisites for Plant Genome Editing

The CRISPR-Cas9 system, derived from a bacterial adaptive immune mechanism, has revolutionized genetic engineering by providing an efficient, precise, and relatively easy genome editing tool [1]. This technology has initiated a new chapter in genetic engineering, enabling researchers to introduce targeted modifications in living cells across diverse organisms, including plants [2] [1]. For plant transformation research, CRISPR-Cas9 offers unprecedented opportunities to accelerate functional genomics studies and crop improvement programs by facilitating the development of plants with enhanced traits such as disease resistance, improved nutritional profiles, and better adaptability to environmental stresses [3] [4].

The fundamental CRISPR-Cas9 system consists of two key components: a DNA-binding domain made of a single guide RNA (sgRNA) and a DNA-cleaving domain comprising the Cas9 endonuclease protein [2]. These components work in concert to identify specific DNA sequences and introduce double-stranded breaks (DSBs) at predetermined genomic locations [1]. The cellular repair mechanisms that address these breaks then enable the introduction of desired genetic modifications [1]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of the CRISPR-Cas9 mechanism, with detailed protocols and resources tailored for plant researchers engaged in transformation studies.

The Core Components of the CRISPR-Cas9 System

Cas9 Nuclease: The Molecular Scissors

The Cas9 protein, most commonly derived from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9), is a large multi-domain DNA endonuclease (1368 amino acids) that functions as the catalytic engine of the system [1]. Structurally, Cas9 consists of two primary lobes: the recognition (REC) lobe and the nuclease (NUC) lobe [1]. The REC lobe, containing REC1 and REC2 domains, is responsible for binding the guide RNA [1]. The NUC lobe contains three critical domains: RuvC and HNH, which each cleave one DNA strand, and the PAM-interacting domain, which confers specificity for the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence essential for target recognition [1].

The PAM sequence, a short conserved DNA sequence downstream of the cut site, is a critical component of target recognition [1]. For SpCas9, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where N can be any nucleotide base [1]. The Cas9 nuclease becomes activated upon binding to both a valid PAM sequence and a complementary target DNA sequence specified by the guide RNA [1].

Table 1: Key Cas Protein Variants and Their Characteristics

| Cas Protein | Source Organism | PAM Sequence | DSB Pattern | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | 5'-NGG-3' | Blunt ends | Most widely used; requires G-rich PAM |

| Cas9 D10A | Engineered mutant | 5'-NGG-3' | Single-strand nick | Nickase; reduced off-target effects when used in pairs |

| Cas9 H840A | Engineered mutant | 5'-NGG-3' | Single-strand nick | Nickase; cleaves non-target strand |

| A.s. Cas12a (Cpfl) | Acidaminococcus sp. | 5'-TTTV-3' | Staggered ends with 5' overhangs | Shorter gRNA; useful for AT-rich regions |

Guide RNA: The Targeting System

The guide RNA is a synthetic hybrid molecule that combines two natural RNA components: the CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) [2] [1]. The crRNA contains a 20-nucleotide guide sequence that is complementary to the target DNA sequence, providing the targeting specificity, while the tracrRNA serves as a binding scaffold for the Cas9 nuclease [1]. For experimental use, these are typically combined into a single guide RNA (sgRNA) molecule through a synthetic hairpin-like loop (linker-loop) [1].

The guide RNA can be delivered in two primary formats, each with optimized lengths determined through empirical studies:

- Two-part gRNA system: Consists of separate crRNA (36 nucleotides optimal length) and tracrRNA (67 nucleotides optimal length) components [5]

- Single guide RNA (sgRNA): Combined molecule with an optimal length of 100 nucleotides [5]

The design of the target-specific spacer sequence is arguably the most critical factor determining CRISPR-Cas9 efficiency and specificity [2]. For plant genomes, which often exhibit high complexity, polyploidy, and repetitive sequences, careful gRNA design is particularly essential to maximize on-target activity while minimizing off-target effects [2].

Comprehensive gRNA Design Strategy for Plant Systems

Principles of Efficient gRNA Design

Designing highly specific gRNA with minimal off-target activity is a prerequisite for successful gene editing in plants [2]. The goal is to achieve the highest possible on-target activity while minimizing off-target effects, which can cause unwanted phenotypes including cell death [5]. The target sequence must be adjacent to a PAM sequence (NGG for SpCas9), but the PAM itself should not be included in the gRNA design [5].

Several factors must be considered during gRNA design, particularly for complex plant genomes like wheat, which has a hexaploid structure with three sub-genomes and a high proportion of repetitive DNA sequences (more than 80%) [2]. These complexities increase the possibility of off-target mutations and decrease editing specificity [2]. Key considerations include GC content (optimal 40-80%), avoidance of repetitive sequences, and ensuring uniqueness of the target across all sub-genomes in polyploid species [2].

Table 2: gRNA Design Parameters for Optimal Editing Efficiency

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Impact on Efficiency | Tool/Resource |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC Content | 40-80% | GC content outside this range decreases efficiency | IDT gRNA design tool [5] |

| gRNA Length | 20 nucleotides | Shorter sequences negatively impact on-target activity | IDT guidelines [5] |

| PAM Position | Immediate 5' of NGG | Essential for Cas9 recognition and cleavage | Cas9 specificity [1] |

| Off-target Potential | Minimal similarity | Reduces unintended editing events | BLAST analysis [2] |

| Secondary Structure | Minimal self-complementarity | Ensures gRNA availability for target binding | RNA folding tools [2] |

A Stepwise Protocol for gRNA Design in Plants

The process of designing gRNA for CRISPR-Cas9-SDN1 genome editing in plants can be divided into three phases: gene verification, gRNA designing, and gRNA analysis [2].

Phase 1: Gene Identification and Verification

- Gene Selection: Identify promising negative regulator genes through literature review of genome editing, RNAi, or TILLING studies [2]. The target gene should ideally have tissue-specific expression rather than pleiotropic effects [2].

- Sequence Retrieval: Obtain the gene sequence and chromosomal location using databases such as Ensembl Plants and KnetMiner [2].

- Homology Analysis: Use BLAST analysis to determine editing ability across various sub-genomes and identify potential off-target sites [2]. Assess similarity between the identified gene and genes in other plant species and sub-genomes using Clustal Omega software [2].

- Cultivar-Specific Considerations: For species with pan-genome resources (e.g., wheat), consult databases that incorporate presence-absence variations, structural variants, and diverse allelic forms across cultivars to enable precise cultivar-specific gRNA design [2].

Phase 2: gRNA Design and Selection

- Target Site Identification: Scan the target gene for sequences matching 5'-N(19-21)-NGG-3' [2].

- Specificity Validation: Verify target uniqueness across the entire genome using BLAST analysis against genomic and cDNA databases [2].

- Efficiency Prediction: Utilize bioinformatic tools to rank potential gRNAs based on predicted efficiency scores [2].

- Multi-gRNA Strategy: For polyploid species, design gRNAs that target all homoeologs simultaneously, or design specific gRNAs for each homoeolog if differential editing is desired [2].

Phase 3: gRNA Validation and Optimization

- Secondary Structure Analysis: Validate gRNA by testing its potential secondary structure, Gibbs free energy, and propensity to base pair within itself [2].

- Vector Compatibility: Check sequence similarity to the cloning binary vector to be used in the study [2].

- Experimental Validation: For critical applications, design multiple gRNAs (typically 3-5) for empirical testing to identify the most effective variant [2].

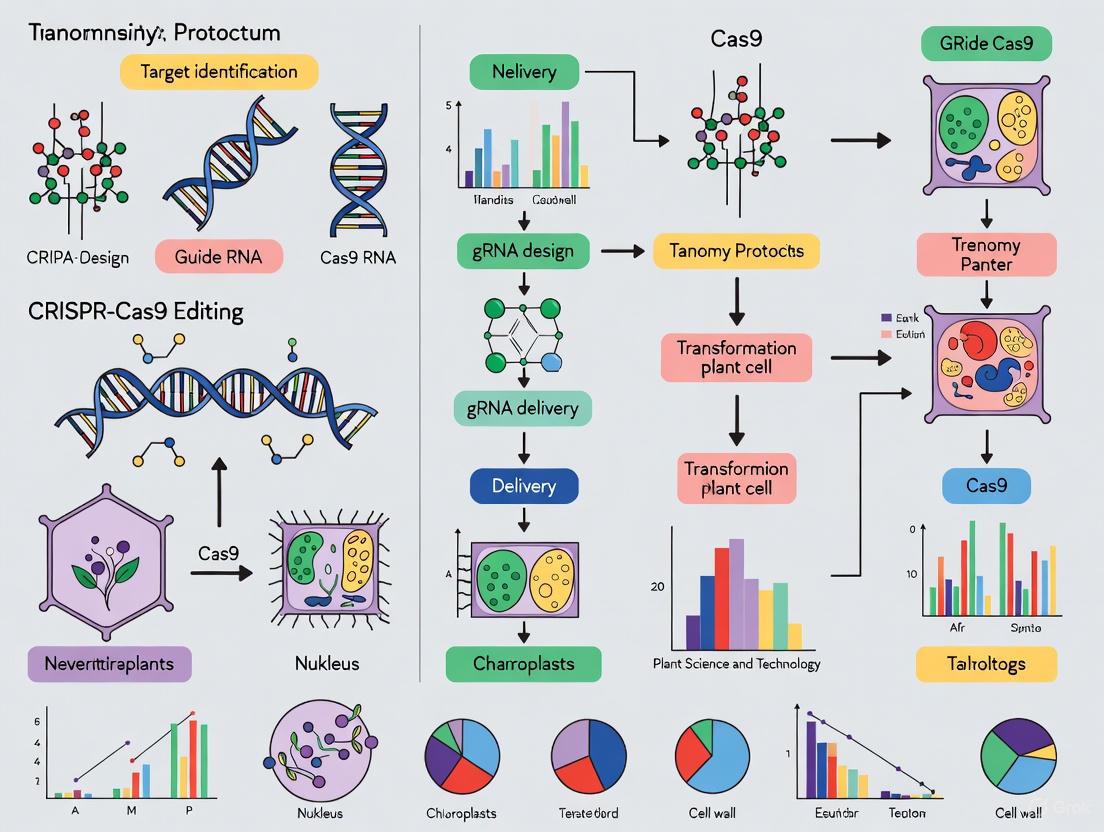

Figure 1: gRNA Design Workflow for Plant CRISPR Systems. This diagram illustrates the comprehensive process for designing effective guide RNAs for plant genome editing, from initial gene selection through experimental validation.

DNA Repair Mechanisms in CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing

Double-Strand Break Repair Pathways

After the CRISPR-Cas9 complex introduces a double-stranded break at the target site, cellular repair mechanisms are activated to repair the damage [1]. The Cas9 nuclease creates DSBs 3 base pairs upstream of the PAM sequence, generating predominantly blunt-ended breaks [1]. Two primary cellular repair pathways address these breaks: Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) [1].

Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) is an error-prone repair mechanism that functions throughout the cell cycle by directly ligating the broken DNA ends without requiring a template [1]. This process often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the cleavage site, which can disrupt gene function through frameshift mutations or premature stop codons, effectively creating gene knockouts [1]. In plants, NHEJ is the predominant DSB repair pathway and is highly efficient for generating gene knockouts [6].

Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) is a precise repair mechanism that requires a donor DNA template with homology to the sequences flanking the DSB [1]. HDR is most active during the late S and G2 phases of the cell cycle and can execute precise gene insertions or replacements by using donor DNA templates containing the desired sequence modifications flanked by homology arms [1]. While HDR offers precision, its efficiency in plants is typically much lower than NHEJ due to competition between the pathways and the infrequency of HDR in somatic plant cells [6].

Table 3: Comparison of DNA Repair Pathways in CRISPR-Cas9 Editing

| Parameter | Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) |

|---|---|---|

| Template Requirement | No template required | Requires homologous donor template |

| Repair Precision | Error-prone (indels) | Precise (specific sequence changes) |

| Efficiency in Plants | High (predominant pathway) | Low (1.12% or less in potato protoplasts) [6] |

| Primary Application | Gene knockouts | Precise gene insertion or replacement |

| Cell Cycle Phase | All phases | Late S and G2 phases |

| Outcome | Random insertions/deletions | Precise, predictable edits |

Optimizing HDR in Plant Systems

HDR remains challenging in plant systems due to its inherently low efficiency in gene editing applications [6]. However, several strategies can improve HDR outcomes:

Donor Template Design: Use single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) donors with 30-97 nucleotide homology arms, which have shown success in potato protoplasts [6]. The target orientation (complementary to the gRNA) generally outperforms the non-target orientation [6].

RNP Delivery: Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex delivery of Cas9 and gRNA enables faster editing onset, reduces off-target effects, and eliminates the risk of random plasmid integration [7].

HDR Enhancement Strategies: Although chemical inhibitors of NHEJ pathways have shown success in animal systems, their efficacy in plants remains limited [6]. Instead, focus on optimizing donor template structure and delivery methods.

Protocol for HDR Donor Design [7]:

- Homology Arm Length: Design ssDNA donors with 30-40 nucleotide homology arms on each side for optimal efficiency in plant systems [6].

- Blocking Mutations: Incorporate silent mutations in the PAM sequence or seed region of the target site to prevent re-cleavage of successfully edited alleles [7].

- Strand Selection: When using ssDNA donors, the target strand (complementary to the gRNA) generally shows higher HDR efficiency than the non-target strand [7].

- Chemical Modifications: Consider adding phosphorothioate (PS) linkages to the ends of ssDNA donors to improve stability and HDR frequency [7].

Figure 2: DNA Repair Pathways After CRISPR-Cas9 Cleavage. This diagram illustrates the two primary cellular repair mechanisms that address double-strand breaks introduced by CRISPR-Cas9, leading to different editing outcomes.

Experimental Protocol for Plant Transformation

CRISPR-Cas9 Construct Assembly and Plant Transformation

The following protocol adapts established methods for tomato and grapevine transformation to provide a generalizable approach for dicot plants [8] [4].

Part 1: Vector Construction using Golden Gate Cloning [8]

- Select appropriate CRISPR backbone vector based on plant species and selection requirements (e.g., pGreen or pCAMBIA backbones) [9].

- Clone gRNA expression cassette into the vector using BsaI restriction sites for modular assembly [9]. For multiplex editing, assemble multiple gRNAs with tRNA spacers [4].

- Choose promoter for Cas9 expression: For dicot plants, the 35S promoter generally shows strong expression, though the RPS5a promoter may offer improved efficiency in some species [4].

- Select optimized Cas9 variant: Use plant-codon optimized Cas9 with intronic sequences (e.g., zCas9i) and two nuclear localization signals (NLS) for enhanced editing efficiency [4].

- Include visual selection marker: Incorporate DsRed2 or similar fluorescent protein under appropriate promoter for efficient screening of transformed tissues [4].

Part 2: Agrobacterium-mediated Plant Transformation [8]

- Prepare explant material: Surface-sterilize cotyledons or other explant tissues from sterile seedlings.

- Agrobacterium co-cultivation:

- Grow Agrobacterium strain EHA105 or GV3101 harboring the CRISPR construct overnight at 28°C

- Resuspend bacteria to OD₆₀₀ = 0.5-1.0 in liquid co-cultivation medium

- Immerse explants in bacterial suspension for 10-30 minutes

- Transfer to co-cultivation medium and incubate at 26°C for 2-3 days in darkness

- Selection and regeneration:

- Transfer explants to selection medium containing appropriate antibiotics (e.g., kanamycin) and bacteriostatic agents (e.g., timentin or cefotaxime)

- Subculture every 2-3 weeks onto fresh selection medium

- Monitor for fluorescent marker expression to identify successfully transformed tissues

- Plant regeneration:

- Transfer putative transgenic calli to shoot induction medium

- Develop shoots for 4-8 weeks, then transfer to root induction medium

- Acclimate regenerated plantlets to greenhouse conditions

Part 3: Molecular Analysis of Transformed Plants

- Genomic DNA extraction from putative transgenic plant leaves

- PCR amplification of target region and selection marker genes

- Sequence verification of edited loci through Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing

- Off-target analysis by examining potential off-target sites identified during gRNA design

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Plant CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Considerations for Plant Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Variants | SpCas9, zCas9i, hCas9 | DNA cleavage enzyme | Plant-codon optimized versions (zCas9i) show higher efficiency [4] |

| gRNA Format | sgRNA, 2-part crRNA:tracrRNA | Targets Cas9 to specific genomic loci | sgRNA (100 nt) most common; 2-part system offers chemical modification options [5] |

| Delivery Method | Agrobacterium, RNP complexes | Introduces editing components to cells | RNP delivery reduces off-target effects; Agrobacterium enables stable transformation [7] |

| Donor Templates | ssODN, dsDNA with homology arms | Provides template for HDR repair | ssDNA with 30-40 nt homology arms effective in plants [6] |

| Selection Markers | DsRed2, NPTII, HPT | Identifies successfully transformed tissues | Fluorescent markers enable early visual screening [4] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | IDT HDR Design Tool, Ensembl Plants, BLAST | gRNA design and specificity analysis | Essential for addressing complex plant genomes with high repetition [2] [7] |

Advanced Applications in Plant Research

CRISPR Activation (CRISPRa) for Gain-of-Function Studies

Beyond gene knockouts, CRISPR technology has been adapted for transcriptional activation through CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) systems [3]. Unlike conventional CRISPR editing that introduces double-stranded breaks, CRISPRa employs a deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) fused to transcriptional activators to upregulate target gene expression without altering the DNA sequence [3]. This approach offers unique opportunities for gain-of-function studies, particularly when studying gene families with functional redundancy where knockouts may fail to reveal phenotypic changes [3].

CRISPRa has been successfully applied in plants to enhance disease resistance by upregulating defense-related genes [3]. For example, in tomato, CRISPRa was used to upregulate the PATHOGENESIS-RELATED GENE 1 (SlPR-1), enhancing plant defense against Clavibacter michiganensis infection [3]. Similarly, upregulation of the SlPAL2 gene through targeted epigenetic modifications led to enhanced lignin accumulation and increased defense [3].

Multiplex Genome Editing for Complex Traits

For polygenic traits controlled by multiple genes, multiplex genome editing enables simultaneous modification of several target loci [9]. Advanced CRISPR toolkits facilitate the assembly of one or more gRNA expression cassettes with high efficiency using modular cloning systems [9]. This approach is particularly valuable for addressing genetic redundancy in polyploid crops or for engineering complex metabolic pathways [9].

The CRISPR-Cas9 system provides plant researchers with a powerful and precise tool for genetic engineering, with applications ranging from basic functional genomics to applied crop improvement. Successful implementation requires careful attention to gRNA design, appropriate selection of CRISPR components, and optimization of transformation protocols for specific plant species. By following the comprehensive guidelines and protocols outlined in this application note, researchers can leverage CRISPR-Cas9 technology to address fundamental questions in plant biology and develop improved crop varieties with enhanced agricultural traits.

In plant biotechnology, the CRISPR-Cas9 system has emerged as a revolutionary tool for functional genomics and crop improvement, enabling researchers to develop climate-resilient varieties of major staple crops such as wheat, rice, and maize [10]. This RNA-guided endonuclease technology facilitates precise genomic modifications through targeted double-strand breaks (DSBs), which are subsequently repaired via endogenous cellular mechanisms [11]. The system's core components include the Cas9 nuclease and a single-guide RNA (sgRNA), with the latter conferring sequence specificity through complementary base pairing to the target DNA site, which must be adjacent to a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) with the sequence NGG [11] [12].

The efficacy and precision of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing are fundamentally dependent on prior access to high-quality genome sequences and comprehensive structural annotations [13]. These genomic resources enable accurate sgRNA design by providing precise coordinates of functional elements, thereby minimizing off-target effects while maximizing editing efficiency. For plant species, this requirement presents unique challenges due to complex genome architectures, including high ploidy levels, extensive repetitive content, and substantial intron-exon structures [14]. This application note delineates the essential prerequisites of genome sequencing and annotation within the context of CRISPR-Cas9 protocols for plant transformation research, providing detailed methodologies and resources to support successful genome editing outcomes.

Genome Annotation Methodologies for Plant Research

Genome annotation encompasses two distinct bioinformatics processes: structural annotation, which identifies the physical locations and structures of functional elements (genes, transcripts, exons, coding sequences, and untranslated regions), and functional annotation, which assigns putative functions, gene symbols, and Gene Ontology terms to these elements [13]. For CRISPR-Cas9 applications, structural annotation is particularly critical as it directly informs target site selection.

Major Annotation Approaches

Current state-of-the-art genome annotation strategies fall into three primary categories, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and input requirements [13]:

Table 1: Comparison of Genome Annotation Approaches

| Method | Underlying Approach | Primary Output | Key Input Requirements | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model-Based (BRAKER) | Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) | Protein-coding genes | Protein sequences from related species (e.g., OrthoDB) and/or RNA-seq data | Annotating proteomes without closely related reference genomes |

| RNA-seq Assembly (Stringtie-TransDecoder) | Transcriptome assembly from splice graphs | Complete transcripts (including UTRs) | Paired-end RNA-seq reads and protein BLAST database | Comprehensive transcriptome annotation when RNA-seq is available |

| Annotation Transfer (TOGA, Liftoff) | Liftover of annotations via whole-genome alignment | Homologous features from reference genome | High-quality annotated genome from closely related species | Rapid annotation when high-quality reference exists |

Decision Framework for Annotation Method Selection

The choice of an appropriate annotation strategy should be guided by research objectives, data availability, and evolutionary considerations. The following workflow provides a systematic approach for selecting the optimal annotation method:

Figure 1: Decision workflow for selecting appropriate genome annotation methods based on available data and research objectives [13].

Special Considerations for Plant Genomes

Plant genomes present unique challenges for annotation and subsequent CRISPR applications due to their distinctive characteristics [13]:

- High Repetitive Content: Many plant genomes contain substantial repetitive elements that can complicate assembly and annotation. For example, the Garra rufa genome has 51.95% of its sequence masked by WindowMasker [15], illustrating the repetitive nature of some genomes.

- Complex Genome Organization: Polyploidy and extensive gene families are common in plants, requiring specialized annotation approaches.

- Annotation Transfer Limitations: Whole-genome alignment between plant species can be challenging due to evolutionary divergence, making annotation transfer methods less reliable than for animal genomes.

For these reasons, empirical validation of genome annotations through RNA-seq data is strongly recommended for plant CRISPR projects, even when using annotation transfer approaches [13].

Experimental Protocols for Genome Annotation

Structural Annotation Using BRAKER2 Pipeline

The following protocol outlines the steps for generating structural annotations using the BRAKER2 pipeline, which employs a combination of GeneMark-ET and AUGUSTUS to predict protein-coding genes [13].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genome Annotation

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Purpose | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Assembly (FASTA) | Target for annotation | Institutional sequencing core or public repositories |

| OrthoDB Protein Set | Evolutionary-informed protein sequences for homology hints | OrthoDB database |

| RNA-seq Reads (FASTQ) | Transcriptional evidence for splice site prediction | NCBI SRA or in-house sequencing |

| BRAKER2 Software | Automated annotation pipeline | GitHub repository |

| BUSCO Dataset | Assessment of annotation completeness | BUSCO website |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Preparation

- Obtain genome assembly in FASTA format (e.g.,

assembly.fasta) - Download taxonomically appropriate protein sequences from OrthoDB

- Format the protein database using BLAST+

- Obtain genome assembly in FASTA format (e.g.,

Protein Alignment

- Align protein sequences to the genome using ProtHint

- Convert alignments to hints for AUGUSTUS

Gene Prediction

- Execute BRAKER2 with protein hints

- Run command:

braker.pl --genome=assembly.fasta --prot_seq=proteins.faa --cores=8 --species=YourSpecies - Generate output in GFF3 format

Quality Assessment

- Assess annotation completeness using BUSCO

- Run command:

busco -i annotation.gff -l actinopterygii_odb10 -o busco_results -m genome

Annotation Transfer Using Liftoff

For researchers with access to a high-quality annotated reference genome from a closely related species, annotation transfer offers a rapid alternative [13]:

Generate Whole-Genome Alignment

- Align reference and target genomes using minimap2 or LASTZ

Execute Annotation Transfer

- Run Liftoff to transfer annotations:

liftoff -g reference.gff target_assembly.fasta reference_assembly.fasta -o transferred_annotations.gff

- Run Liftoff to transfer annotations:

Validate Transferred Annotations

- Check for complete BUSCO scores compared to reference

- Manually inspect key gene families of interest

Integration with CRISPR-Cas9 Experimental Design

High-quality genome annotations directly inform multiple aspects of CRISPR-Cas9 experimental design in plants, significantly enhancing the probability of successful editing outcomes.

sgRNA Design and Target Selection

Comprehensive genome annotations enable strategic sgRNA design through the identification of:

- Exon-Intron Boundaries: sgRNAs should preferentially target exonic regions, particularly first exons downstream of start codons, to maximize probability of functional knockouts [16]

- Functional Domains: Annotations facilitate targeting of critical protein domains for complete loss-of-function mutations

- Sequence Uniqueness: Annotations enable BLAST searches to ensure sgRNA specificity and minimize off-target effects

For example, in tomato genome editing protocols, sgRNAs are designed within the first exon closer to the start codon to ensure disruption of the functional protein [16].

Assessment of Editing Outcomes

Following CRISPR-Cas9-mediated transformation, genome annotations facilitate molecular characterization of edited plants through:

- High-Resolution Melt (HRM) Analysis: Annotations provide coordinates for designing PCR primers flanking target sites

- Sanger Sequencing: Annotated reference sequences enable alignment and identification of induced mutations

- Variant Effect Prediction: Structural annotations allow prediction of functional consequences of edits (e.g., frameshifts, premature stop codons)

In potato editing protocols, HRM analysis coupled with annotations enables efficient screening of tetraploid mutants without the need for lengthy segregation [14].

Case Study: Fusarium oxysporum Genome Annotation for Virulence Gene Editing

A recent application of annotation-driven CRISPR editing targeted the SIX9 effector gene in Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. cubense race 1 (Foc1), a pathogen causing Fusarium wilt in bananas [17]. The experimental workflow demonstrates the critical role of prior genome annotation:

Figure 2: Workflow for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated editing of Fusarium oxysporum SIX9 effector gene [17].

This study relied on previously annotated Fusarium oxysporum genomes to identify the SIX9 gene as a candidate virulence factor. Researchers then designed two sgRNAs targeting this annotated locus and developed an optimized in vitro protocol to produce highly active Cas9 protein, demonstrating enzymatic activity comparable to commercial standards [17]. The success of this pathogen-focused editing approach underscores the value of comprehensive genome annotation for both plant and pathogen genomics in developing transformative crop protection strategies.

High-quality genome sequences and structural annotations represent foundational prerequisites for effective CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in plants. By enabling precise sgRNA design, informing target selection strategies, and facilitating molecular characterization of edited lines, comprehensive annotations significantly enhance editing efficiency and functional outcomes. As CRISPR technologies continue to evolve toward more sophisticated applications—including base editing, prime editing, and multiplexed interventions—the importance of accurate genomic references will only intensify. Plant researchers should prioritize investment in robust annotation pipelines tailored to their species of interest, as these resources ultimately determine the success and reproducibility of genome editing initiatives aimed at crop improvement and climate resilience.

Within the framework of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing protocols for plant transformation, tissue culture represents the fundamental bridge between genetic manipulation and the recovery of viable, genetically stable plants. While CRISPR-Cas9 systems provide the tools for precise genomic modifications, the success of entire editing initiatives hinges upon the ability to regenerate whole plants from single, transformed cells. This protocol details the establishment of robust regeneration pathways, specifically tailored for use with CRISPR-edited plants, to ensure the efficient recovery of non-transgenic, edited lines. The methodologies outlined herein are critical for converting edited cells into homozygous, transgene-free plants, thereby solidifying the functional genomics and trait improvement pipeline [10] [18].

The Critical Role of Regeneration in CRISPR-Cas9 Workflows

The regeneration phase is the most critical determinant of success and timeline in plant genome editing projects. A typical workflow to obtain an edited, transgene-free plant requires 6–12 months, with the majority of this time dedicated to the tissue culture and regeneration steps [18]. The regeneration protocol must be finely synchronized with the transformation and editing event. Following Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of plant explants with CRISPR-Cas9 constructs, the application of precisely formulated plant growth regulators in the culture media directs cell division and fate. Genetically edited, single cells must undergo dedifferentiation to form a callus, followed by redifferentiation into shoots and roots. The efficiency of this process directly impacts the number of independent edited events recovered, thereby influencing the statistical power of subsequent phenotypic analyses [18] [19]. Furthermore, the selection of regeneration strategy is pivotal for achieving transgene excision. By leveraging the sexual reproduction of regenerated T0 plants, transgene-free T1 progeny carrying the stable knockout mutation can be isolated through molecular screening, fulfilling the promise of CRISPR-Cas9 for non-transgenic plant improvement [18].

Table 1: Key Stages and Durations in a CRISPR-Cas9 Regeneration Pipeline for Tomato

| Stage | Process Description | Key Media/Treatments | Typical Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Explant Preparation & Transformation | Sterilization and co-cultivation with Agrobacterium carrying CRISPR-Cas9 | Acetosyringone induction medium (CIM II) | 2-3 days |

| 2. Callus Induction & Selection | Dedifferentiation of explant tissue into callus; selection of transformed cells | Callus Induction Medium (CIM I, CIM II) with antibiotics | 2-4 weeks |

| 3. Shoot Regeneration | Redifferentiation of callus into shoot primordia | Shoot Induction Medium (SIM I, SIM II) with cytokinins | 4-8 weeks |

| 4. Root Regeneration | Development of roots from shoots | Root Induction Medium (RIM) with auxins | 2-4 weeks |

| 5. Acclimatization & Seed Set | Transfer to soil and growth to maturity in greenhouse | N/A | 8-12 weeks |

| 6. Molecular Screening | Identification of transgene-free edited progeny in T1 generation | PCR, ddPCR, sequencing | 4-8 weeks |

Experimental Protocol: Regeneration of CRISPR-Edited Tomato Plants

The following step-by-step protocol, adapted from a established method for generating knockout lines in tomato, provides a detailed methodology for the regeneration of edited plants, from explant to transgene-free progeny [18].

Materials and Reagents

Biological Materials

- Solanum lycopersicum cv. MoneyMaker (or other suitable cultivar)

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 harboring the CRISPR-Cas9 binary vector (e.g., pZG23C04 or similar)

Media and Solutions Prepare all media according to the recipes listed in Section 3.2. Adjust pH to 5.8 before autoclaving. Add filter-sterilized hormones and antibiotics after the medium has cooled to approximately 50°C.

Media Formulations

Table 2: Detailed Composition of Tissue Culture Media for Tomato Regeneration

| Medium Name | Basal Salt/Vitamin Base | Carbon Source | Solidifying Agent | Growth Regulators | Other Additives (post-sterilization) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ½ MS (Pre-culture) | 2.15 g/L MS + Gamborg B5 vitamins | 10 g/L Sucrose | 8 g/L Agar | - | - |

| CIM I | 4.3 g/L MS + Gamborg B5 vitamins | 30 g/L Sucrose | 5.2 g/L Phytoagar | 1 mg/L 2,4-D, 0.2 mg/L Kinetin | 1 mg/L Thiamine HCl |

| CIM II | 4.3 g/L MS + Gamborg B5 vitamins | 30 g/L Sucrose | 5.2 g/L Phytoagar | 1 mg/L 2,4-D, 0.2 mg/L Kinetin | 1 mg/L Thiamine HCl, 200 μM Acetosyringone |

| SIM I | 4.3 g/L MS + Gamborg B5 vitamins | 30 g/L Sucrose | 5.2 g/L Phytoagar | 2 mg/L trans-Zeatin | 1 mg/L Thiamine HCl, 100 mg/L Kanamycin, 250 mg/L Timentin |

| SIM II | 4.3 g/L MS + Gamborg B5 vitamins | 30 g/L Sucrose | 5.2 g/L Phytoagar | 1 mg/L trans-Zeatin | 1 mg/L Thiamine HCl, 0.1 mg/L IAA, 100 mg/L Kanamycin, 250 mg/L Timentin |

| RIM | 4.3 g/L MS + Gamborg B5 vitamins | 30 g/L Sucrose | 5.2 g/L Phytoagar | 1 mg/L IAA | 50 mg/L Kanamycin, 250 mg/L Timentin |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Explant Preparation and Transformation

- Surface Sterilization: Sterilize tomato seeds in 70% ethanol for 5 minutes, followed by immersion in a 50% sodium hypochlorite solution for 30 minutes. Rinse thoroughly with sterile water [18].

- Germination: Aseptically place seeds on half-strength MS medium and culture in a growth chamber for 14 days.

- Co-cultivation: Excise cotyledons or other explants from seedlings and immerse in an Agrobacterium suspension (OD~600 = 0.5-1.0) prepared in CIM II medium containing acetosyringone. Co-cultivate for 2-3 days in the dark.

Step 2: Callus Induction and Selection

- Transfer explants to CIM I medium containing timentin to suppress Agrobacterium growth. Culture for one week.

- Subsequently, transfer explants to fresh CIM I medium supplemented with both kanamycin (for selection of transformed cells) and timentin. Subculture to fresh medium every two weeks for a total of 2-4 weeks until callus formation is observed.

Step 3: Shoot Regeneration

- Move developed calli to SIM I medium to initiate shoot organogenesis. Maintain cultures under a 16/8 hour light/dark photoperiod.

- After two weeks, transfer developing shoot primordia to SIM II medium to promote further shoot elongation. Subculture every two weeks until shoots are 2-3 cm tall.

Step 4: Root Regeneration and Acclimatization

- Excise elongated shoots and transfer to RIM medium to induce root formation.

- Once a robust root system has developed, carefully remove plantlets from the culture vessels, gently wash off agar, and transfer to sterile soil in small pots.

- Maintain high humidity for the first week by covering pots with transparent domes, gradually reducing humidity to acclimate plants to greenhouse conditions.

Step 5: Molecular Screening for Edited, Transgene-Free Plants

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from leaf tissue of regenerated T0 plants and subsequent T1 progeny.

- Mutation Analysis: Use PCR to amplify the target genomic region, followed by Sanger sequencing or next-generation sequencing to identify indel mutations [18] [19].

- Transgene Segregation: Screen T1 progeny for the absence of the Cas9/sgRNA transgene cassette using PCR with primers specific to the HPT (hygromycin) or other selectable marker gene. Plants lacking the transgene but harboring the desired mutation are the final product [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Plant Regeneration Protocols

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Vector System | pZG23C04, pZNH2GTRU6, pZD202-Cas3 [18] [19] | Provides the genetic machinery for genome editing; contains Cas9/Cas3 nuclease, sgRNA expression cassette, and selectable marker. |

| Plant Growth Regulators | 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), Kinetin, trans-Zeatin, IAA [18] | Directs cell fate: auxins like 2,4-D promote callus formation, while cytokinins like zeatin stimulate shoot initiation. |

| Selection Agents | Kanamycin, Hygromycin [18] [19] | Selects for plant cells that have integrated the T-DNA from the binary vector by conferring antibiotic resistance. |

| Antibiotics for Microbiology | Ampicillin, Rifampicin, Gentamicin, Timentin [18] | Used for bacterial culture selection (Amp, Rif, Gen) and plant culture decontamination (Timentin eliminates Agrobacterium post-co-cultivation). |

| Enzymes for Molecular Cloning | BsaI, BbsI, T4 DNA Ligase [18] [9] | Restriction enzymes and ligases for Golden Gate assembly of sgRNA sequences into the CRISPR binary vector. |

| Molecular Validation Kits | PCR Purification Kit, Plasmid DNA Purification Kit, DNeasy Plant Mini Kit [18] | Essential for molecular biology workflows, including vector construction and genomic DNA extraction for genotyping. |

Workflow Visualization: From Explant to Edited Plant

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow, integrating both the molecular and tissue culture stages.

The selection of an appropriate editing tool is a critical first step in designing successful plant genome engineering experiments. CRISPR-based systems have evolved from simple nucleases that create double-strand breaks (DSBs) to more sophisticated base editors that enable precise nucleotide conversions without DSBs [20] [21]. This Application Note provides a structured comparison between Cas nucleases and base editors, offering detailed protocols for their application in plant transformation research. The guidance is tailored for researchers and scientists engaged in plant functional genomics and crop improvement programs, with a focus on practical implementation considerations.

Core Technology Comparison: Mechanisms and Outcomes

Fundamental Editing Mechanisms

Cas Nucleases generate double-stranded breaks (DSBs) at targeted genomic locations [20] [11]. These breaks are primarily repaired through either the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, which often results in insertions or deletions (indels) that disrupt gene function, or the homology-directed repair (HDR) pathway, which requires a donor template for precise edits [20] [21]. The classic example is Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), which recognizes a 5'-NGG-3' protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) and creates blunt-ended DSBs [20] [11].

Base Editors achieve precise nucleotide conversions without creating DSBs by fusing a catalytically impaired Cas nuclease (nickase or dead Cas) to a deaminase enzyme [20] [21]. Cytosine Base Editors (CBEs) mediate C•G to T•A transitions, while Adenine Base Editors (ABEs) mediate A•T to G•C transitions [20] [22]. This approach minimizes unintended indels and is particularly valuable for introducing specific single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or creating premature stop codons [21].

Comparative Analysis of Editing Tools

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Cas Nucleases and Base Editors

| Feature | Cas Nucleases | Base Editors |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Creates DSBs | Chemical conversion of bases without DSBs [21] |

| DNA Repair Pathway | NHEJ, HDR [20] | Base excision repair [21] |

| Typical Editing Outcomes | Indels (insertions/deletions), gene knockouts, large deletions [20] [11] | C→T or A→G transitions (point mutations) [20] [22] |

| Product Purity | Mixed outcomes (indels) [20] | High (typically >90% desired base conversion without indels) [21] |

| PAM Requirement | Yes (e.g., NGG for SpCas9) [20] [11] | Yes (determined by the Cas moiety) [21] |

| Multiplexing Capability | High (via multiple gRNAs) [21] [22] | Moderate |

| Optimal Editing Window | Precise cut site | ~3-5 nucleotide window within the protospacer [20] |

| Delivery Size | ~4.2 kb for SpCas9 | Larger (~5-6 kb) due to added deaminase domains |

| Common Applications | Gene knockouts, gene insertions (with donor), large deletions | SNP introduction, corrective point mutations, creating stop codons [21] |

Decision Framework for Tool Selection

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for selecting between Cas nucleases and base editors based on research objectives and sequence context:

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multiplexed Gene Knockout Using Cas9 Nuclease

Objective: Simultaneously disrupt multiple genes in Nicotiana benthamiana using SpCas9 and tRNA-sgRNA polycistronic vectors [22].

Materials:

- Golden Gate modular cloning toolkit [22]

- pIZZA-BYR-SpCas9 and pBYR2eFa-U6-sgRNA binary vectors [23]

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101

- N. benthamiana plants (4-6 weeks old)

Procedure:

sgRNA Design and Vector Assembly:

Plant Transformation:

- Introduce the final construct into Agrobacterium.

- Infiltrate N. benthamiana leaves using standard procedures.

- Incubate plants for 7 days post-infiltration.

Editing Efficiency Analysis:

- Extract genomic DNA from infiltrated tissue.

- Amplify target regions and quantify editing efficiency using T7E1 assay or amplicon sequencing [23].

Expected Results: Editing efficiencies typically range from 0.1% to >30% across different sgRNA targets [23]. Multiplexing enables simultaneous knockout of up to six genes in a single transformation.

Protocol 2: Precision Base Editing in Rice Protoplasts

Objective: Introduce a specific C-to-T point mutation in the OsEPSPS gene using a cytidine base editor.

Materials:

- Plant-optimized cytidine base editor (e.g., pTarget-AID) [21]

- Rice protoplasts isolated from etiolated seedlings

- PEG transformation solution

Procedure:

Base Editor Design and Delivery:

- Design sgRNA with target cytidine within positions 3-8 of the protospacer.

- Co-deliver base editor and sgRNA constructs to rice protoplasts via PEG-mediated transformation.

Editing Analysis:

- Harvest protoplasts 48 hours post-transformation.

- Extract genomic DNA and amplify target region.

- Detect base conversions using restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) or Sanger sequencing.

Off-Target Assessment:

Expected Results: Typical base editing efficiencies of 1-20% in rice protoplasts with minimal indels (<1%). Product purity can exceed 90% [21].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Plant Genome Editing

| Reagent Type | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Nucleases | SpCas9, SaCas9, StCas9, ScCas9, FnCas12a, LbCas12a [22] | SpCas9 (NGG PAM) most common; SaCas9 (NNGRRT PAM) smaller size; Cas12a (TTTV PAM) creates staggered ends |

| Base Editors | Target-AID (CBE), ABE7.10 [22] | Target-AID for C-to-T conversions; ABE for A-to-G conversions |

| Promoters (Monocot) | OsU3p, OsU6-2p, TaU3p [22] | Drive gRNA expression in monocots |

| Promoters (Dicot) | AtU6-26p [22] | Drives gRNA expression in dicots |

| Delivery Vectors | pIZZA-BYR-SpCas9, pBYR2eFa-U6-sgRNA [23] | Binary vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation |

| Cloning Systems | Golden Gate Modular Toolkit [22] | Enables rapid assembly of multigene constructs |

| Detection Reagents | T7E1, RFLP enzymes, AmpSeq kits [23] | For quantifying editing efficiency |

| Bioinformatics Tools | CRISPOR, CRISPR-P 2.0 [23] [25] | sgRNA design and specificity checking |

Advanced Applications and Emerging Technologies

Expanding Targeting Scope with Engineered Cas Variants

The PAM requirement represents a significant limitation for targeting specific genomic regions. Engineered Cas variants with altered PAM specificities have substantially expanded the targeting scope [20] [22]. SpCas9-NG recognizes NG PAMs instead of NGG, while xCas9 recognizes NG, GAA, and GAT PAMs [20] [22]. ScCas9 from Streptococcus canis recognizes NNG PAMs, further expanding potential target sites [22]. When planning experiments requiring targeting of specific sequences with restricted PAM availability, these variants provide valuable alternatives to wild-type SpCas9.

Editing Efficiency Optimization Strategies

Editing efficiency varies significantly based on genomic context, chromatin accessibility, and sgRNA design. Several strategies can enhance editing efficiency:

- gRNA Design: Select guides with high predicted efficiency scores (e.g., Doench'16 score) [23]

- Regulatory Elements: Use appropriate Pol III promoters (U3/U6) matched to your plant species [22]

- Expression Optimization: Implement egg cell-specific promoters (e.g., DD45) for heritable edits in Arabidopsis [21]

- Delivery Method Selection: Choose between Agrobacterium, biolistics, or nanoparticle-based delivery based on plant species and application [26] [27]

Recent advances in nanoparticle-mediated delivery and viral vectors have shown promising results for improving editing efficiency, particularly in difficult-to-transform species [27].

The selection between Cas nucleases and base editors represents a fundamental decision point in plant genome engineering experimental design. Cas nucleases remain the tool of choice for gene knockouts and large-scale modifications, while base editors offer superior precision for single-nucleotide changes. The continued development of engineered Cas variants with expanded PAM compatibilities, improved specificity, and novel functionalities promises to further enhance our capability to precisely modify plant genomes. By following the structured decision framework and optimized protocols outlined in this Application Note, researchers can systematically select the most appropriate editing tools for their specific plant transformation research objectives.

The classification of genome editing applications into SDN-1, SDN-2, and SDN-3 provides a critical framework for researchers navigating the regulatory landscape of plant biotechnology. These categories, defined by Friedrichs et al. (2019), differentiate genome editing techniques based on their molecular mechanisms and outcomes, with direct bearing on regulatory considerations [28]. This classification system helps distinguish between edits that result in small, targeted mutations versus those that incorporate larger DNA sequences, which has implications for risk assessment and regulatory oversight. Within the context of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing protocols for plant transformation, understanding these categories is essential for designing experiments that align with both research objectives and regulatory requirements.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized plant molecular biology by providing powerful tools for precise gene manipulation [16]. This technology utilizes guide RNAs (gRNAs) that direct the Cas9 endonuclease to generate double-stranded breaks (DSBs) at targeted genomic locations [29]. The cellular repair of these breaks then leads to specific mutations. The SDN classification system specifically addresses how these breaks are repaired and whether external DNA templates are used, creating a spectrum of technical approaches with differing regulatory implications.

SDN Classification System: Mechanisms and Applications

Molecular Mechanisms and Technical Distinctions

The SDN categorization is fundamentally based on the DNA repair pathways employed following the creation of a targeted double-strand break. Each category represents a distinct approach to genome editing with specific technical considerations and outcomes.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of SDN Classification Categories

| Classification | Repair Mechanism | Template Required | Typical Outcome | Primary Applications in Plants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDN-1 | Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | No | Small insertions or deletions (indels), gene knockout | Gene silencing, loss-of-function mutations, functional genomics [28] |

| SDN-2 | Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) | Short single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide | Introduction of small, specific point mutations | Precise amino acid changes, fine-tuning gene function [28] |

| SDN-3 | Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) | Large double-stranded DNA vector | Insertion of large DNA sequences (e.g., genes) | Gene insertion, trait stacking, metabolic engineering [28] |

SDN-1 involves the unguided repair of a specific DSB by the Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) pathway [28]. This error-prone repair process often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the target site. These mutations can modify a gene's activity, cause gene silencing, or create a knockout by disrupting the reading frame. SDN-1 is considered an efficient method with many applications already demonstrated in various crops [28]. It is particularly valuable for creating loss-of-function mutations to study gene function or to deactivate undesirable genes.

SDN-2 utilizes a short nucleic acid sequence donor, typically a single-stranded DNA oligonucleotide, to direct the repair of a specific DSB through Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) [28]. The donor template is designed with one or more desired mutations flanked by homology sequences that match the regions on either side of the DSB. This allows for precise, predefined changes to be introduced at the target locus. SDN-2 is more complex than SDN-1 due to the lower efficiency of HDR in plants, but it enables more subtle edits than complete gene knockouts.

SDN-3 employs a larger sequence donor, usually a double-stranded DNA molecule carrying a gene or extended genetic element, to direct the repair of a targeted DSB via HDR [28]. The donor typically features long homology arms (often exceeding 800 base pairs each) that flank the insert, facilitating its integration at the target site. SDN-3 is technically the most challenging approach but allows for the introduction of entirely new functions, such as inserting a gene for disease resistance or enhancing nutritional content.

Visualizing the SDN Classification Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow and decision-making process for selecting and implementing the different SDN categories in a plant genome editing project.

Diagram 1: SDN Category Selection Workflow. This diagram outlines the decision-making process for selecting the appropriate SDN classification based on the desired editing outcome in plant genome editing projects.

Experimental Protocols for SDN-Based Plant Genome Editing

Core Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9 System Assembly and Plant Transformation

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for implementing SDN-1 type editing (gene knockout) in tomato plants, which can be adapted with modifications for SDN-2 and SDN-3 approaches.

Background: Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) serves as an important model organism for crop improvement studies [16]. CRISPR-Cas9 provides an effective tool for uncovering the complex functions of tomato genes. The primary objective of this protocol is to establish a robust strategy for producing knockout lines (SDN-1) in tomato plants, which could be adapted for SDN-2 and SDN-3 approaches with the inclusion of appropriate repair templates.

Key Features [16]:

- Two sgRNAs employed for increased efficiency

- Takes 6–12 months to generate edited transgene-free plants

- Specifically optimized for tomato cv. MoneyMaker

Materials and Reagents:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Plant Transformation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Vector System | pZG23C04, pICH47742::2x35S-5'UTR-hCas9(STOP)-NOST | Carries Cas9 and sgRNA expression cassettes | [16] |

| Cloning Enzymes | BpiI (BbsI), BsaI HF, T4 DNA Ligase | Golden Gate assembly of sgRNAs into vectors | [16] |

| Plant Transformation | Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 | Delivery of CRISPR constructs to plant cells | [16] [30] |

| Selection Agents | Kanamycin, Timentin | Selection of transformed plant tissue | [16] |

| Plant Growth Regulators | trans-Zeatin, 2,4-D, IAA, Kinetin | Direct shoot and root regeneration | [16] |

| Culture Media | CIM I, CIM II, SIM I, SIM II, RIM | Support different stages of plant tissue development | [16] |

Procedure:

sgRNA Design and Cloning:

- Design two sgRNAs targeting the first exon downstream and closer to the start codon of the gene of interest [16].

- Use online tools (e.g., CRISPR-Plant, CRISPOR) to minimize off-target effects [26].

- Assemble sgRNA expression cassettes using Golden Gate cloning with BpiI (BbsI) or BsaI enzymes into the final CRISPR-Cas9 binary vector [16] [30].

Plant Transformation:

- Introduce the assembled plasmid into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 [16].

- Use 7-8 day old tomato cotyledons (S. lycopersicum cv. MoneyMaker) as explants [30].

- Perform co-cultivation with Agrobacterium for 2 days [30].

- Transfer explants to selection media (SIM I) containing kanamycin (100 mg/L) and timentin (250 mg/L) to inhibit Agrobacterium growth [16].

Plant Regeneration [16]:

- Culture explants on Shoot Induction Medium (SIM I and SIM II) with appropriate plant growth regulators (trans-zeatin) to promote shoot formation.

- Transfer developed shoots to Root Induction Medium (RIM) containing auxins to encourage root development.

- Maintain cultures at 25°C with a 16/8 hour light/dark cycle.

Screening and Molecular Characterization:

- Extract genomic DNA from regenerated plantlets.

- Use PCR amplification of the target region followed by restriction enzyme digestion or high-resolution melt (HRM) analysis to detect mutations [14].

- Sequence PCR products to confirm the exact nature of induced mutations [14].

- Screen for transgene-free plants by analyzing segregation in the next generation [16].

Adaptation for SDN-2 and SDN-3 Approaches

For SDN-2 applications, include a single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotide (ssODN) donor template in the transformation procedure. This template should contain the desired point mutation(s) flanked by homology arms (approximately 40-80 bp) matching the sequence on either side of the cleavage site [28].

For SDN-3 approaches, a larger double-stranded DNA donor must be provided. This is typically a vector containing the gene or genetic element to be inserted, flanked by long homology arms (often >800 bp each) corresponding to the sequences surrounding the target site [28]. The delivery of this large donor template can be challenging and may require optimization of concentration and delivery method.

Regulatory Considerations and Concluding Remarks

The SDN classification framework provides a structured approach to categorizing genome editing outcomes that has important implications for regulatory science. Generally, SDN-1 and some SDN-2 applications may face simpler regulatory pathways in many jurisdictions, as the resulting plants may contain only small mutations indistinguishable from those obtained through conventional breeding or chemical mutagenesis, and often contain no foreign DNA [31]. In contrast, SDN-3 approaches typically fall under stricter regulatory oversight similar to traditional transgenic crops, as they involve the insertion of larger DNA sequences, potentially including genes from unrelated species.

The experimental protocols detailed herein for tomato can be adapted to other crop species with modifications to the transformation and regeneration methods. The continuous refinement of CRISPR-Cas9 technology, including the development of base editors and prime editors that can create precise changes without double-strand breaks, further expands the toolbox available to plant scientists [26] [31]. When planning genome editing projects, researchers should consider both the technical feasibility of different SDN approaches and the regulatory implications of their chosen strategy, keeping abreast of evolving policies in their target countries.

Practical Transformation Methods and Trait Engineering Applications

Agrobacterium-mediated stable transformation remains a cornerstone technique in plant biotechnology, enabling the precise integration of foreign DNA into plant genomes. Within modern functional genomics and breeding programs, this method has become indispensable for delivering CRISPR-Cas9 components, facilitating advanced genome editing in a wide range of plant species [10] [32] [33]. The natural ability of Agrobacterium tumefaciens to transfer T-DNA from its Ti plasmid to plant cells provides a highly efficient system for generating transgenic plants with stable, single-copy insertion events, which are crucial for consistent transgene expression and regulatory compliance [34] [33]. This application note details current vector systems and optimized protocols that leverage Agrobacterium-mediated transformation for CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, supported by quantitative efficiency data and standardized methodologies for reproducible results across diverse plant species.

Vector Systems for Agrobacterium-mediated Transformation

Conventional and Gateway Binary Vectors

Traditional binary vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation contain the necessary components for T-DNA transfer: left and right border sequences, multiple cloning sites for gene insertion, selectable marker genes for plants, and bacterial resistance markers. These vectors replicate in both E. coli and Agrobacterium, facilitating molecular cloning and plant transformation workflows [34] [35].

The Gateway Technology has significantly streamlined vector construction through site-specific recombination, eliminating dependence on restriction enzymes. This system uses BP and LR Clonase enzyme mixes to efficiently shuttle genes of interest from Entry clones into various Destination vectors [35]. A key advantage is the ccdB negative selection system, which prevents growth of non-recombinant colonies after the LR reaction, ensuring high cloning efficiency. When using vectors with identical antibiotic resistance markers, the differential replication origins (e.g., ColE1 for E. coli and pVS1 for Agrobacterium) enable successful selection. The pENTR vector cannot replicate in Agrobacterium, allowing for direct transformation of LR reaction mixtures and selective recovery of the desired binary vector in this host [35].

CRISPR-Cas9 Expression Vectors

Specialized binary vectors have been developed to express the CRISPR-Cas9 system in plants. These typically feature:

- A plant codon-optimized Cas9 gene driven by constitutive promoters such as CaMV 35S or maize Ubiquitin1 [32] [33]

- RNA polymerase III promoters (e.g., AtU6, TaU3, TaU6) to drive single-guide RNA (sgRNA) expression [33]

- Multiple cloning sites for inserting sgRNA expression cassettes to enable multiplexed genome editing

- Optional donor DNA templates for homology-directed repair (HDR)

The pYLCRISPR/Cas9 system has been successfully deployed in wheat, rice, and tomato, demonstrating the versatility of these vector platforms across diverse crops [32] [33].

Quantitative Transformation Efficiencies Across Plant Systems

Transformation efficiency varies significantly across plant species, cultivars, and experimental conditions. The table below summarizes reported efficiencies for different plant systems using Agrobacterium-mediated transformation.

Table 1: Transformation Efficiencies in Various Plant Systems

| Plant Species | Genotype/Cultivar | Target Gene | Transformation Efficiency | Key Factors | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus carbonarius (Fungus) | - | ayg1 (conidial pigment) | High (Method-dependent) | Agrobacterium strain selection critical | [36] |

| Common Wheat | Fielder | DA1 | 54.17% (T0 mutation rate) | Agrobacterium strain EHA105; immature embryos | [33] |

| Tomato | M82 | ALC | 72.73% (T0 mutation rate) | Hypocotyl explants; 35S promoter for Cas9 | [32] |

| Carrot | - | - | >85% | Somatic embryogenesis; 2,4-D hormone | [37] |

| Japonica Rice | Taichung 65 | - | High (Protocol-optimized) | Meropenem for bacterial control; mature embryos | [34] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Streamlined Cloning Protocol Using Gateway Technology

This protocol enables efficient cloning of genes into binary vectors for Agrobacterium transformation, specifically addressing challenges when vectors share identical antibiotic resistance markers [35].

Materials

- pENTR/D-TOPO cloning kit

- Gateway-compatible binary vector (e.g., pMDC series)

- Chemically competent E. coli (TOP10, DH5α)

- Chemically competent Agrobacterium (EHA105, EHA101)

- LB and YEP media with appropriate antibiotics

- Gateway LR Clonase enzyme mix

Procedure

Entry Clone Construction

- Design gene-specific primers with CACC overhang at the 5' end of the forward primer

- Amplify the gene of interest using high-fidelity DNA polymerase

- Purify the PCR product and set up TOPO cloning reaction

- Transform into competent E. coli and select on kanamycin plates

- Verify positive clones by colony PCR and sequencing

LR Reaction for Binary Vector Construction

- Set up LR recombination reaction mixing Entry clone with Destination vector

- Transform the entire LR reaction mixture into competent Agrobacterium cells

- Plate on YEP medium with appropriate antibiotic (e.g., kanamycin)

- Isolate single colonies and verify recombinant binary vectors by PCR

Critical Note: The pENTR vector cannot replicate in Agrobacterium, so only cells containing the recombined binary vector will grow, providing effective selection even when antibiotic resistance markers are identical [35].

Agrobacterium-mediated Transformation of Japonica Rice

This optimized protocol for japonica rice cv. Taichung 65 enables production of transgenic plants within approximately 90 days using mature embryos [34].

Materials

- Mature seeds of japonica rice cv. Taichung 65

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA101 or EHA105

- Binary vector with gene of interest and selection marker (e.g., hygromycin resistance)

- Sterilization solution: 70% ethanol, 1% NaClO with Tween 20

- Co-cultivation medium: N6-based with sucrose, glucose, casamino acid, proline

- Selection medium: Hygromycin B with meropenem

- Regeneration medium: N6-based with hormones

Procedure

Callus Induction from Mature Seeds

- Sterilize mature seeds in 70% ethanol (30 sec) followed by 1% NaClO (15 min)

- Rinse 5 times with sterile water

- Culture seeds on callus induction medium in dark at 25°C for 3-4 weeks

- Select friable, yellowish-white embryogenic calli for transformation

Agrobacterium Preparation and Infection

- Grow Agrobacterium harboring binary vector in LB medium with appropriate antibiotics

- Resuspend bacteria in co-cultivation medium to OD~600~ = 0.1

- Immerse selected calli in bacterial suspension for 30 minutes

- Blot dry on sterile filter paper and transfer to co-cultivation medium

- Incubate in dark at 25°C for 2-3 days

Selection and Regeneration of Transgenic Plants

- Transfer co-cultivated calli to selection medium containing hygromycin and meropenem

- Subculture every 2 weeks onto fresh selection medium

- Transfer developing calli to regeneration medium under light (5000 lux)

- Transfer regenerated shoots to rooting medium

- Acclimate plantlets in greenhouse conditions

Key Optimization: Using meropenem instead of carbenicillin or cefotaxime for Agrobacterium elimination significantly improves shoot regeneration rates in rice [34].

CRISPR-Cas9 Mutagenesis in Common Wheat

This protocol demonstrates successful Agrobacterium-mediated delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 to common wheat, achieving high mutation rates in the T~0~ generation [33].

Materials

- Common wheat cultivar Fielder

- Binary vector pYLCRISPR/Cas9Pubi-B with sgRNA expression cassette

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105

- Immature wheat embryos (14-16 days post-anthesis)

Procedure

Vector Design and Construction

- Design sgRNAs targeting genes of interest (e.g., Pinb, waxy, DA1)

- Clone sgRNA expression cassettes under TaU6 or TaU3 promoters

- Assemble final CRISPR/Cas9 construct using binary vector system

Wheat Transformation

- Collect immature wheat spikes at 14-16 DPA

- Surface sterilize with 75% ethanol (30 sec) and 1% NaClO (15 min)

- Isolate immature embryos and incubate with Agrobacterium suspension for 5 min

- Co-cultivate on medium for 2 days in darkness at 25°C

- Remove embryonic axes and transfer scutella to callus induction medium

- Implement progressive selection and regeneration as described [33]

Mutation Analysis

- Extract genomic DNA from T~0~ transgenic plants

- PCR-amplify target regions and sequence products

- Analyze sequencing chromatograms for indel mutations

- Screen for off-target effects in highly homologous genomic regions

Efficiency Note: This protocol achieved 54.17% mutation frequency in T~0~ wheat plants with no detected off-target mutations, demonstrating the precision of Agrobacterium-mediated CRISPR-Cas9 delivery [33].

Visualization of Agrobacterium-mediated Transformation Workflow

Figure 1: Agrobacterium-mediated Plant Transformation Workflow. This diagram outlines the key stages from vector preparation to molecular confirmation of transgenic plants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Agrobacterium-mediated Transformation

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium Strains | T-DNA delivery to plant cells | EHA101, EHA105, AGL1, LBA4404 [36] [34] [33] |

| Binary Vectors | Carrying gene of interest between T-DNA borders | pMDC series, pYLCRISPR/Cas9Pubi-B [33] [35] |

| Selection Antibiotics | Selection of transformed plant tissues | Kanamycin, Hygromycin B [34] [35] |

| Agrobacterium Suppressors | Eliminating bacterial overgrowth after co-cultivation | Meropenem, Carbenicillin, Cefotaxime [34] |

| Plant Growth Regulators | Inducing callus formation and regeneration | 2,4-D (somatic embryogenesis), Cytokinins, Auxins [37] |

| Gateway Cloning System | Efficient vector construction without restriction enzymes | pENTR/D-TOPO, LR Clonase enzyme mix [35] |

Agrobacterium-mediated stable transformation continues to evolve as an essential platform for plant genome engineering, particularly with the integration of CRISPR-Cas9 technologies for precise genome editing. The protocols and vector systems detailed in this application note provide researchers with standardized methodologies that have demonstrated high efficiency across diverse plant species, from model plants to agriculturally important crops. As plant biotechnology advances toward more sophisticated applications, these foundational transformation techniques will remain crucial for functional genomics, trait development, and the creation of climate-resilient crops to address global agricultural challenges.

Within the broader scope of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing protocols for plant transformation research, transient transformation systems are indispensable tools for rapid functional genomics analysis. Unlike stable transformation, which integrates transgenes into the plant genome, transient transformation involves temporary gene expression, enabling quick assessment of gene editing efficiency and function before committing to lengthy stable transformation and regeneration processes. Two predominant systems—protoplast isolation and hairy root assays—provide versatile platforms for validating CRISPR constructs, studying gene function, and characterizing cellular processes. This document details the application, optimization, and methodology of these systems, providing structured protocols and quantitative data to support researchers in plant biotechnology and drug development who seek to implement these approaches for accelerated genome editing workflows.

Protoplast-Based Transient Transformation Systems

Protoplasts are plant cells that have had their cell walls removed enzymatically, creating a versatile platform for transient expression assays. The polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated transformation of protoplasts enables efficient delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 components, including plasmid DNA, in vitro transcripts, and pre-assembled ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes [38]. This system is particularly valuable for rapid validation of guide RNA (gRNA) efficiency and nuclease activity before embarking on stable transformation. Applications extend to subcellular localization, protein interaction studies, transcriptional regulation analysis via dual-luciferase assays, and multi-omics research [39]. A significant advantage of RNP delivery is the generation of transgene-free edited plants, addressing regulatory concerns associated with genetically modified organisms [38].

Quantitative Data from Optimization Studies

Recent optimization studies across diverse plant species have yielded critical quantitative data for protocol establishment. The tables below summarize key parameters for protoplast isolation and transformation.

Table 1: Optimized Protoplast Isolation Parameters Across Plant Species

| Plant Species | Optimal Enzyme Composition | Optimal Osmoticum (Mannitol) | Incubation Conditions | Yield (Protoplasts/g FW) | Viability | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncaria rhynchophylla | 1.25% Cellulase R-10 + 0.6% Macerozyme R-10 | 0.8 M | 5 h, 26°C, 40 rpm | 1.5 × 10⁷ | >90% | [39] |

| Banana (Cavendish) | 1.25% Cellulase R-10 + 0.6% Macerozyme R-10 | 0.8 M | 5 h, 26°C, dark | Not specified | >90% | [38] |

| Wheat (cv. Roblin) | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | ~60% Transfection Efficiency | [40] |

Table 2: Optimized PEG-Mediated Protoplast Transformation Parameters

| Parameter | Uncaria rhynchophylla [39] | Banana [38] | Wheat [40] |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEG Concentration | 40% | 50% | Not specified |

| Plasmid DNA Amount | 40 µg | Not specified | Not specified |

| Transformation Duration | 40 min | 30 min | Not specified |

| Incubation Temperature | 24°C (overnight) | Not specified | Not specified |

| Transformation Efficiency | 71% | 5.6% | ~60% |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: PEG-Mediated Transformation of Protoplasts with CRISPR/Cas9 RNPs

Principle: This protocol describes the isolation of mesophyll protoplasts from leaf tissue and their subsequent transfection with pre-assembled CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes via PEG-mediated transformation. The method is adapted from established procedures in banana [38] and Uncaria rhynchophylla [39].

Materials:

- Plant Material: Young, fully expanded leaves from in vitro plantlets or healthy greenhouse-grown plants.

- Enzyme Solution: Comprising Cellulase R-10, Macerozyme R-10, and osmoticum (e.g., 0.6 M mannitol or 0.8 M D-mannitol) in an appropriate salt solution (e.g., MMG solution: 0.6 M mannitol, 15 mM MgCl₂, 4 mM MES, pH 5.7).

- Washing Solution (WS): 0.6 M mannitol, 20 mM KCl, 4 mM MES, pH 5.7.

- PEG Solution: 40% (w/v) PEG 4000 in MMG solution or 0.6 M mannitol and 0.1 M CaCl₂.

- CRISPR Reagents: Purified Cas9 protein and synthesized target-specific sgRNA.

Procedure:

- Protoplast Isolation: a. Slice leaves into thin strips (0.5–1.0 mm) using a sharp razor blade. b. Submerge tissue in the pre-warmed enzyme solution. c. Incubate in the dark for 4-6 hours at 26°C with gentle shaking (e.g., 40 rpm). d. Gently release protoplasts by swirling the flask. Filter the mixture through a 70-100 μm nylon mesh to remove undigested debris. e. Centrifuge the filtrate at 100 × g for 5 minutes to pellet protoplasts. Carefully remove the supernatant. f. Resuspend the pellet in WS and centrifuge again. Repeat this wash step. g. Resuspend the final protoplast pellet in an appropriate volume of MMG solution. Count protoplasts using a hemocytometer and adjust the density to 2 × 10⁵ cells/mL.

RNP Complex Assembly: a. Pre-assemble the RNP complex by mixing purified Cas9 protein with a molar excess of sgRNA in a suitable buffer. b. Incubate the mixture at 25°C for 15-30 minutes to allow complex formation.

PEG-Mediated Transformation: a. Aliquot 2 × 10⁵ protoplasts (in 100 μL MMG) into a round-bottom tube. b. Add the pre-assembled RNP complex (e.g., 10-20 μg Cas9 protein with corresponding sgRNA). c. Add an equal volume of 40% PEG solution (e.g., 100 μL) dropwise, gently mixing after each addition. d. Incubate the transformation mixture at room temperature for 30-40 minutes. e. Carefully stop the reaction by gradually adding 4-5 volumes of WS with gentle mixing. f. Centrifuge at 100 × g for 5 minutes to pellet the transfected protoplasts. Remove the supernatant. g. Resuspend the protoplasts in an appropriate culture medium and incubate in the dark at 24-26°C for 48-72 hours to allow for genome editing to occur before analysis.

Mutation Analysis: a. Extract genomic DNA from transfected protoplasts after the incubation period. b. Amplify the target genomic region by PCR. c. Analyze editing efficiency using methods such as: - PCR-Restriction Enzyme (PCR-RE) assay if the edit disrupts a restriction site [38] [40]. - T7 Endonuclease I or Surveyor nuclease assay. - Sanger sequencing of cloned PCR amplicons or deep amplicon sequencing for a quantitative assessment [38].

Figure 1: Workflow for Protoplast Isolation and RNP Transformation. This diagram outlines the key steps for establishing a transient CRISPR/Cas9 system in plant protoplasts, highlighting critical optimized parameters from recent studies [38] [39].

Hairy Root-Based Transient Transformation Systems

Hairy root transformation utilizes the natural DNA transfer capability of Agrobacterium rhizogenes (Rhizobium rhizogenes). This soil-borne bacterium infects wounded plant sites and transfers T-DNA from its Root-Inducing (Ri) plasmid into the plant genome, leading to the development of genetically transformed "hairy roots" [41]. This system provides a rapid and convenient means to obtain transgenic roots within a few weeks, making it particularly valuable for studying root biology, root-microbe interactions, and the production of root-derived secondary metabolites. When combined with CRISPR/Cas9, it serves as a powerful platform for functional gene validation in roots, especially in species where stable plant regeneration is difficult or time-consuming. The system has been successfully applied in 26 different plant species, including legumes like soybean and peanut, for CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome editing [41].

Key Agrobacterium rhizogenes Strains and Vector Components

The choice of A. rhizogenes strain and CRISPR vector design are critical for successful genome editing in hairy roots.

Table 3: Widely Used Agrobacterium rhizogenes Strains for Hairy Root Transformation [41]

| Strain | Also Known As | Origin/Source | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATCC15834 | LBA9340, 15834, AR15834 | Isolated from rose | One of the first wild-type strains widely used; contains pRi15834 plasmid. |

| A4 | ATCC43057 | Isolated from rose | Wild-type strain; contains pRiA4 plasmid; gave rise to derivative A4RS. |

| A4RS | - | Derivative of A4 | Resistant to rifampicin and spectinomycin; lacks pArA4a plasmid; frequently used. |