A Practical Guide to Visual CRISPR Screening: Using GFP Reporters for Efficient Transformat Selection and Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing visual screening of CRISPR transformants using GFP markers.

A Practical Guide to Visual CRISPR Screening: Using GFP Reporters for Efficient Transformat Selection and Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing visual screening of CRISPR transformants using GFP markers. It covers the foundational principles of CRISPR-GFP reporter systems, from basic mechanisms to advanced screening setups. The content details practical methodologies for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-based enrichment and high-throughput screening workflows. Critical troubleshooting sections address common challenges like low transfection efficiency and unexpected GFP expression. The guide also explores rigorous validation strategies to confirm editing outcomes, comparing GFP-based methods with other validation techniques. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging applications, this resource aims to enhance the efficiency and reliability of CRISPR screening campaigns in both basic research and therapeutic development.

GFP as a Visual Reporter in CRISPR Screening: Principles and System Design

The convergence of Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) technology with CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has revolutionized molecular biology, enabling real-time visual tracking of editing events within living cells. While GFP has been historically used as a quantitative reporter of gene expression [1], its adaptation into CRISPR systems provides researchers with a powerful tool to screen for successful transformants efficiently. These fluorescent CRISPR reporters function by linking a visible signal—the emission of green light—to the successful activity of the Cas9 nuclease or the precise incorporation of an edit via homology-directed repair. This direct visual feedback is invaluable for applications ranging from functional genomic screening to the development of cell and gene therapies, allowing scientists to bypass labor-intensive cloning and sequencing steps during initial screening phases. This article details the core mechanisms of these systems and provides standardized protocols for their implementation.

Core Mechanisms of CRISPR-GFP Reporter Systems

CRISPR-GFP reporters operate primarily through two ingenious molecular designs that couple the DNA cleavage or repair outcome to the functional expression of the fluorescent protein.

Frameshift-Based Detection of NHEJ

The most common mechanism involves the detection of Cas9-induced double-strand breaks that are repaired via the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway. In this setup, the coding sequence for a fluorescent protein like GFP or mCherry is cloned out-of-frame [2] [3]. Upstream of this fluorescent protein is a CRISPR target site—a copy of the genomic sequence that the sgRNA is designed to cut.

In the unedited state, the reporter is transcribed and translated, but due to the frameshift, the fluorescent protein is not produced, or only a non-functional peptide is made. When the Cas9/sgRNA complex successfully cleaves the reporter construct, the cellular NHEJ repair machinery introduces small insertions or deletions (indels) at the break site. A fraction of these indels will result in a frameshift mutation that places the fluorescent protein back into the correct reading frame. Consequently, the cell fluoresces, serving as a visual proxy for successful Cas9 cutting and NHEJ activity at the intended genomic locus [2] [3]. Systems like GEmCherry2 are engineered based on this principle, with optimizations such as the removal of alternative start codons to minimize background fluorescence [3].

HDR-Specific Reporter Systems

For applications requiring precise homology-directed repair (HDR), more sophisticated reporters like SRIRACCHA have been developed. This system uses a stably integrated reporter gene containing a puromycin resistance gene followed by the target site and an out-of-frame H2B-GFP reporter [3]. When a donor DNA template is co-transfected along with Cas9 and the sgRNA, a successful HDR event at the reporter locus uses the donor to correct the frame, leading to GFP expression. This HDR event in the reporter indicates that a parallel precise editing event is likely to have occurred at the endogenous genomic target [3]. A key advantage of the SRIRACCHA system is its reversibility, allowing for the removal of the reporter cassette after the desired mutant has been identified [3].

Table 1: Comparison of Key CRISPR-GFP Reporter Systems

| Reporter System | Core Mechanism | Repair Pathway Detected | Key Feature(s) | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GEmCherry2 [3] | Out-of-frame mCherry | NHEJ | Low background; rapid sgRNA validation | Quantifying Cas9/sgRNA cutting efficiency |

| Dual Fluorochrome Reporter [2] | Out-of-frame GFP; iRFP transfection control | NHEJ | 17 target sites for multiplexing; enables enrichment of edited cells | Editing challenging cells (e.g., primary patient samples) |

| SRIRACCHA [3] | Out-of-frame H2B-GFP with donor template | HDR | Reversible integration; enriches for precise edits | Isolating cells with precise HDR-based genome edits |

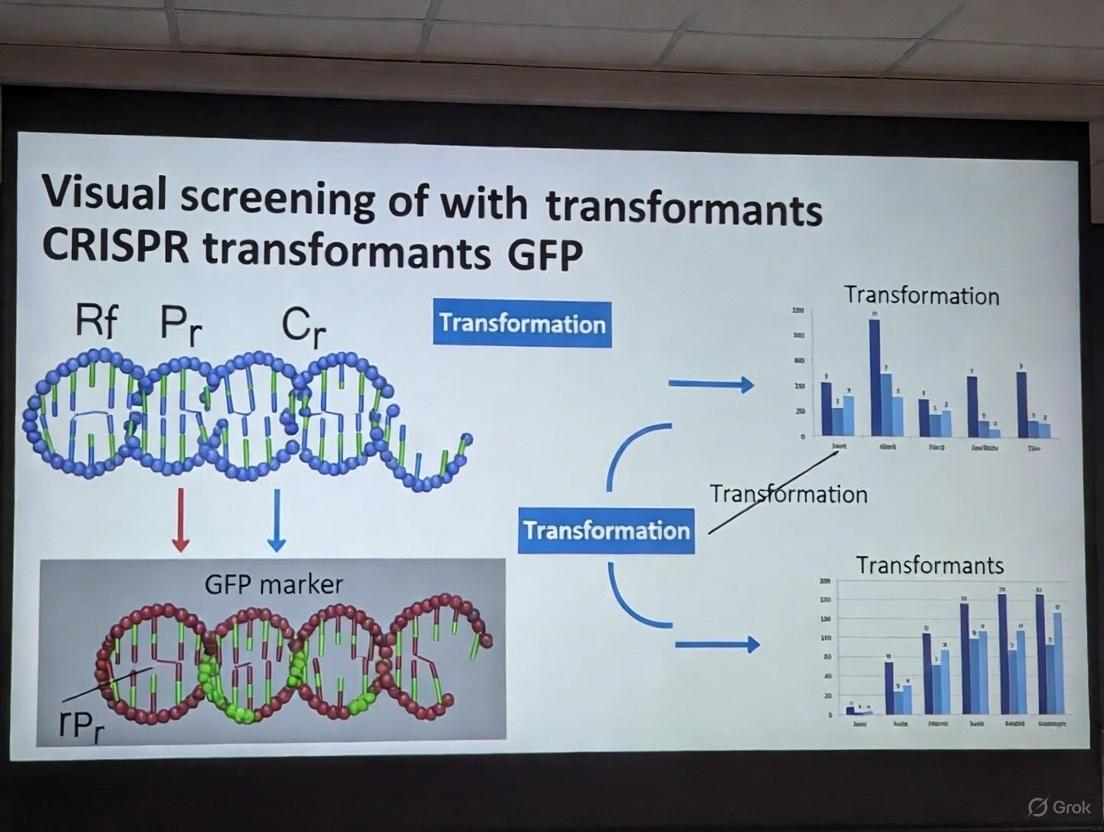

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of the frameshift-based NHEJ reporter system:

Application Notes & Protocols

Protocol: Using a Frameshift GFP Reporter to Enrich KO Cells

This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully enriched CRISPR-edited patient-derived xenograft (PDX) cells, which are notoriously difficult to culture in vitro [2].

Key Materials:

- Cells: A cell line stably expressing Cas9 (e.g., NALM-6 used in the study).

- Reporter Plasmid: A dual-fluorochrome reporter construct (e.g., constitutively expressing iRFP-720 and an out-of-frame, destabilized GFP).

- sgRNA Vector: A lentiviral vector expressing your target sgRNA and a marker like mTagBFP.

Procedure:

- Stable Cell Line Generation: Lentivirally transduce your Cas9-expressing cells with the dual-fluorochrome reporter plasmid. Use flow cytometry to sort for iRFP-positive cells, establishing a polyclonal reporter cell line [2].

- Transduction with sgRNA: Transduce the reporter cell line with the lentiviral sgRNA vector. Aim for a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) to ensure single integrations and mimic conditions for challenging primary cells [2].

- Incubation and Expression: Culture the transduced cells for 3-5 days to allow for CRISPR cutting, repair, and GFP expression.

- Flow Cytometry and Sorting: Analyze the cells using a flow cytometer. First, gate for mTagBFP-positive cells (indicating sgRNA presence). Within this population, identify and sort the mTagBFP-iRFP-GFP triple-positive cells [2].

- Validation: The sorted GFP-positive population is highly enriched for cells with successful knockout (KO) at the genomic target. Validate editing efficiency via downstream methods like droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) or capillary immunoassay for protein loss [2].

Protocol: Rapid Generation of Homozygous Fluorescent Reporter Knock-In Pools

Generating knock-in reporter cell lines traditionally relies on tedious single-cell cloning. This protocol uses a single-plasmid system and FACS to rapidly create biallelic knock-in cell pools, preserving parental cell heterogeneity [4].

Key Materials:

- Single-Plasmid Construct: A vector combining the sgRNA (often under a doxycycline-inducible promoter) and the donor DNA template for HDR.

- Donor DNA Design: The donor should contain the fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP) sequence linked to the C-terminus of the endogenous target gene via a T2A "self-cleaving" peptide sequence. The start codon of the fluorescent reporter should be removed to prevent false positives from random integration [4].

Procedure:

- Electroporation: Deliver the single-plasmid construct into your target cells (e.g., mammalian cell lines like MEC or JHH5) using electroporation. The study used parameters of 870 V, 35 ms pulse width, and 2 pulses with the Neon Electroporation System [4].

- Induction and Culture: After electroporation, culture cells in medium containing 2 µg/mL doxycycline for 2 days to induce sgRNA expression. Then, replace with standard medium and culture for an additional ~10 days to allow for HDR and degradation of transiently expressed donor DNA [4].

- Fluorescence Detection and Sorting: After the culture period, use flow cytometry to detect and sort cells that are positive for the knock-in fluorescent reporter.

- Establishment of Stable Pools: Culture the sorted fluorescent cells to establish a stable knock-in cell pool. This pool will consist of a mixture of monoallelic and biallelic knock-in cells. The researchers noted that this method significantly reduces the rate of random integration compared to a dual-plasmid system [4].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Issues in CRISPR-GFP Reporter Assays

| Problem | Potential Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High background fluorescence | Alternative translation initiation; random integration of donor DNA. | Use optimized reporters like GEmCherry2 [3]; remove the start codon from the fluorescent reporter in the donor DNA [4]. |

| Low editing efficiency in GFP+ cells | Inefficient sgRNA; poor HDR efficiency. | Use the reporter to first validate and rank sgRNA efficiency [3]; use a single-plasmid system to improve HDR [4]. |

| Low signal-to-noise ratio in flow cytometry | Weak fluorescence from the reporter protein. | Use bright, stable fluorescent proteins like eYGFPuv [5] or link the GFP to a histone (H2B) for nuclear concentration [3]. |

| Poor enrichment of edited cells | Linker sequence issues leading to false negatives. | Incorporate a 48 bp glycine linker between the Cas9 target site and the GFP to prevent disruption of the GFP coding region during large deletions [2]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of CRISPR-GFP reporter assays requires a suite of well-characterized reagents. The table below lists key materials and their functions.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-GFP Reporter Assays

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Reporter Plasmid | Provides the visual readout for editing. | GEmCherry2 (for NHEJ) [3]; SRIRACCHA (for HDR) [3]; Dual iRFP/GFP reporter [2]. |

| Cas9 Expression System | Provides the nuclease for DNA cleavage. | Stable cell line, transfected plasmid, or ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. |

| sgRNA Expression Vector | Guides Cas9 to the specific genomic locus. | Can be cloned into vectors with fluorescent markers (e.g., mTagBFP) for tracking transduction [2]. |

| HDR Donor Template | Serves as a repair template for precise knock-in. | Designed with ~500-800 bp homology arms and a T2A-linked fluorescent protein without its start codon [4]. |

| Flow Cytometer / Cell Sorter | Essential for quantifying and isolating fluorescent cells. | Used for both analyzing editing efficiency and enriching positive populations [2] [4]. |

| Integrase-Deficient Lentivirus (IDLV) | Delivery method for transient expression of editing components without genomic integration. | Minimizes random integration risks; ideal for hard-to-transfect cells [4]. |

Within CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing, the efficient screening and isolation of successfully transformed cells is a critical step. Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) reporter systems serve as a powerful tool for this visual screening, enabling researchers to rapidly identify edited cells. A fundamental design choice in developing these systems lies in the configuration of the GFP cassette: whether to use a promoter-driven or a promoterless construct. This article details the design considerations, experimental protocols, and key applications for both systems, providing a framework for their use in the visual screening of CRISPR transformants.

The core distinction between these systems hinges on the presence or absence of a dedicated promoter sequence upstream of the GFP gene. This choice dictates the experimental workflow, the interpretation of results, and the types of biological questions that can be addressed.

The logical relationship and primary applications of these two systems are summarized in the following diagram:

Promoter-Driven GFP Systems

In this conventional approach, the GFP gene is placed under the control of a strong, constitutive promoter (e.g., CMV, EF1α, or 35S in plants). This design ensures robust, continuous expression of GFP in any cell that has successfully incorporated the transgene, independent of the genomic integration site or the status of the target gene.

- Advantages: The system provides a bright, easily detectable signal that facilitates the rapid screening of positive transformants. It is particularly useful for tracking transfection efficiency and ensuring the presence of the CRISPR construct in cells [6].

- Disadvantages: A significant drawback is that GFP expression confirms only the presence of the vector, not successful on-target gene editing. Furthermore, the persistent presence of the transgene, including the fluorescent marker, can be undesirable for downstream applications or clinical use. A promoter-driven system can also lead to aberrant expression, as suggested by studies showing unexpected GFP expression even in the absence of a canonical promoter [7].

Promoterless GFP Systems

Promoterless designs place the GFP coding sequence without an upstream promoter. Expression is typically made dependent on a specific genomic event, such as successful Homology-Directed Repair (HDR) that places GFP in-frame with an endogenous, active promoter.

- Advantages: This system directly reports on a successful editing outcome. It enables the precise knock-in of a reporter and allows for the enrichment of cells that have undergone the desired HDR event, thereby reducing false positives from random integration [2] [4]. It is also instrumental in studying the activity of endogenous promoters.

- Disadvantages: The signal can be weaker and more variable, as it is subject to the regulation of the endogenous promoter. The design and construction are more complex, requiring careful consideration of homology arms and in-frame fusion. There is also evidence that GFP may exhibit low-level, aberrant expression even without a promoter, which could contribute to background noise [7].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The choice between promoterless and promoter-driven systems involves trade-offs in editing efficiency, signal strength, and false-positive rates. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from published studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Promoterless and Promoter-Driven GFP Reporter Systems

| System Type | Reported Editing Efficiency | Key Functional Outcome | False Positive/Background Signal Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promoter-Driven | 75-90% (Transient) [6] | Visual confirmation of transfection/transduction; Isolation of transgene-free mutants in subsequent generations [6]. | Potential for aberrant expression without promoter; confirms vector presence, not editing [7]. |

| Promoterless (HDR-dependent) | Up to 80% enrichment of edited alleles [2] | Successful knock-in and reporting on endogenous gene activity; Effective enrichment of HDR-edited cells [2] [4]. | Lower random integration; requires specific frameshift for activation in surrogate assays [2]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Using a Promoter-Driven GFP System to Identify CRISPR Transformants

This protocol is adapted from applications in plant and mammalian systems [6].

1. Materials:

- CRISPR/Cas9 vector with a constitutive promoter (e.g., 35S, CMV) driving GFP expression.

- Target cells (e.g., Arabidopsis, strawberry, soybean, or mammalian cell lines).

- Transformation/transfection reagents (e.g., Agrobacterium for plants, electroporation/lipofection for mammalian cells).

- Fluorescence microscope or flow cytometer.

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: Delivery. Introduce the CRISPR/Cas9-GFP vector into your target cells using the standard method for your system.

- Step 2: Screening (T0). After an appropriate incubation period (e.g., 2-7 days), screen cells or tissues for GFP fluorescence. GFP-positive events indicate successful delivery of the vector.

- Step 3: Mutation Analysis. Genotype the GFP-positive transformants using PCR/restriction enzyme digestion or sequencing to confirm on-target mutations at the genomic locus of interest.

- Step 4: Isolating Transgene-Free Mutants (T1/T2). Allow the primary transformants (T0) to self-cross or propagate. In the next generation (T1/T2), screen for individuals that show the expected mutant phenotype but lack GFP fluorescence. These are potential transgene-free mutants, as the CRISPR cassette has segregated away [6].

Protocol: Using a Promoterless GFP System to Enrich HDR-Edited Cells

This protocol is based on a dual-fluorochrome surrogate reporter system used in patient-derived xenograft (PDX) leukemia cells [2] [4].

1. Materials:

- Reporter Vector: Construct containing a constitutive red fluorescent protein (e.g., iRFP720) and an out-of-frame, promoterless GFP. The target sgRNA sequence is cloned upstream of GFP.

- CRISPR Components: Cas9 and sgRNA expression constructs.

- Target cells (e.g., NALM-6 cell line or primary PDX cells).

- Flow cytometer for cell sorting (FACS).

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: Co-transfection/Transduction. Deliver the promoterless GFP reporter vector along with the Cas9 and sgRNA constructs into the target cells.

- Step 2: Enrichment and Analysis. After 48-72 hours, analyze the cells by flow cytometry.

- First, gate for red fluorescent (iRFP720+) cells to select a population that has successfully taken up the reporter construct.

- Within this population, identify and sort the double-positive (iRFP720+/GFP+) cells. The expression of GFP indicates that a frameshift mutation has occurred at the target site, restoring the GFP reading frame and serving as a surrogate for Cas9 activity [2].

- Step 3: Validation. Validate the sorted cells by genotyping the endogenous target locus (e.g., via droplet digital PCR) to confirm a high frequency of indels. Protein analysis (e.g., Western blot) can confirm knockout of the target gene [2].

The workflow for this promoterless enrichment system is illustrated below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential reagents and their functions for implementing the described GFP reporter systems.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for GFP Reporter Systems

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Reporter System | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutive Promoters (e.g., CMV, EF1α, 35S) | Drives strong, ubiquitous expression of GFP for tracking vector presence. | Visual screening of positive transformants in T0 generation [6]. |

| Dual-Fluorochrome Surrogate Reporter | Combines a constitutive marker (iRFP) with an out-of-frame GFP to enrich for nuclease-active cells. | Enriching CRISPR-edited PDX cells where HDR efficiency is low [2]. |

| T2A Self-Cleaving Peptide | Enables the co-translation of a gene of interest and GFP from a single transcript, often used in promoterless knock-in strategies. | Creating precise fluorescent reporter knock-in cell pools without a start codon on GFP [4]. |

| Integrase-Deficient Lentiviral Vector (IDLV) | Delivers transgenes transiently without genomic integration, minimizing random insertion. | Delivering CRISPR/sgRNA/donor DNA for HDR with reduced background [4]. |

| Native Visual Screening Reporter (NVSR) | Uses endogenous genes (e.g., FveMYB10 for anthocyanin) as a visible marker instead of GFP. | Identifying transgenic lines in plants without foreign fluorescent protein genes [8]. |

Both promoterless and promoter-driven GFP reporter systems are invaluable for the visual screening of CRISPR transformants, yet they serve distinct purposes. The promoter-driven approach offers a straightforward method for confirming transfection and initial transformation, and is highly effective for subsequently isolating transgene-free edited lines. In contrast, the promoterless strategy provides a more direct functional readout, enabling the precise enrichment of cells that have undergone the desired genome editing event, such as HDR, while minimizing false positives from random integration. The optimal design is dictated by the specific experimental goals, whether that is maximizing throughput and simplicity or ensuring precision and accurate reporting of endogenous gene activity.

In visual screening of CRISPR transformants using GFP markers, the selection of the genomic integration site is a fundamental determinant of success. A well-chosen locus ensures consistent, high-level expression of the GFP reporter, enabling reliable detection and selection of successfully edited cells without disrupting essential cellular functions. Targeting high-expression "safe harbor" loci, such as the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) gene, provides a strategic solution to the common challenges of variable transgene expression and unpredictable phenotypic effects associated with random integration. This protocol details the rationale and methods for identifying and utilizing these optimal sites, with GAPDH serving as a primary model, to enhance the efficiency and reliability of CRISPR-based visual screening workflows.

Rationale for High-Expression Loci

Defining a Safe Harbor Locus for Visual Screening

A ideal locus for visual reporter integration exhibits several key characteristics:

- High and Stable Expression: The locus should reside within a transcriptionally active genomic region to drive sufficient GFP expression for easy detection across all transfected cells, minimizing false negatives.

- Neutrality for Cell Fitness: Integration at the site should not disrupt the function of essential genes or critical regulatory elements, thereby avoiding deleterious effects on cell growth, metabolism, or phenotype, which could confound experimental results.

- Open Chromatin Architecture: A chromatin environment that is more accessible to transcription machinery favors consistent and robust transgene expression.

The GAPDH locus exemplifies these properties. As a classic housekeeping gene constitutively expressed at high levels throughout the cell cycle, it provides a powerful endogenous promoter for driving GFP expression [9]. Furthermore, research has demonstrated that the precise integration of a transgene into the GAPDH locus via CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homologous recombination can be achieved without impairing the expression of the endogenous GAPDH gene itself, confirming its status as a safe harbor [9].

Established Safe Harbor Loci for CRISPR/GFP Work

While GAPDH is a robust choice, researchers have successfully targeted other loci for stable transgene expression. The table below summarizes several validated safe harbor loci.

Table 1: Established Genomic Safe Harbor Loci for Transgene Integration

| Locus Name | Organism | Key Characteristics | Application in CRISPR/GFP |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | Pig, Human, Mouse | High-expression housekeeping gene; integration shown not to affect endogenous gene expression [9]. | Knock-in of promoterless GFP cassettes; reliable visual marker detection. |

| Rosa26 | Mouse, Pig | Ubiquitously expressed genomic locus with high transcriptional activity; widely validated as a safe harbor [9]. | A standard site for landing various transgenes, including GFP reporters. |

| pH11 | Pig | Locus supports integration and expression of large transgenes (>9 kb) [9]. | Suitable for complex expression cassettes requiring high expression. |

| AAVS1 | Human | Safe harbor locus on human chromosome 19; known for open chromatin structure. | Common target for human cell line engineering with fluorescent reporters. |

Quantitative Data on Locus Performance

The effectiveness of a target locus is ultimately quantified by editing efficiency and reporter expression strength. The following table consolidates key performance metrics from published studies.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Selected Loci and Enhancement Strategies

| Parameter | Locus/System | Performance Metric | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knock-in Efficiency | GAPDH Locus | Successful GFP knock-in and expression confirmed [9]. | Porcine fetal fibroblasts (PFFs). |

| Editing Enhancement | CRISPR/Cas9-RAD51 | ~2.5-fold increase in knock-out efficiency vs. standard CRISPR/Cas9 [10]. | HEK293T cells (targeting GAPDH). |

| System Efficiency | Plasmid-based (EPIC) | Average of 41.9% correct transformants [11]. | Candida auris protoplasts. |

| Editing Validation | GFP-to-RFP Conversion | >95% GFP-negative population indicating highly efficient Cas9 cleavage [12]. | Human gastric organoids (TP53/APC DKO). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: GFP Knock-in at the GAPDH Locus in Porcine Cells

This protocol is adapted from a study demonstrating the use of the GAPDH locus as a safe harbor for foreign gene knock-ins [9].

I. Research Reagent Solutions Table 3: Essential Reagents for GAPDH GFP Knock-in

| Reagent | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| PX330 Plasmid | CRISPR/Cas9 vector for expressing sgRNA and Cas9 nuclease [9]. |

| GAPDH-gRNA Oligos | Oligonucleotides encoding the sgRNA targeting the GAPDH locus. |

| pCDNA3.1-GAPDH-GFP-KI-donor | Donor vector containing a promoterless 2A-GFP cassette flanked by ~900 bp homology arms for the GAPDH locus [9]. |

| Lipofectamine 2000 | Transfection reagent for delivering plasmids into PK15 and 3D4/21 cell lines. |

| Electroporation Buffer | For transfection of primary porcine fetal fibroblasts (PFFs). |

| G418 (Geneticin) | Selective antibiotic for enriching transfected cells. |

II. Step-by-Step Workflow

- sgRNA Design and Cloning: Design an sgRNA to target the 3' end of the porcine GAPDH coding sequence, just before the stop codon. Anneal the oligonucleotides and ligate them into the BbsI site of the PX330 vector [9].

- Donor Vector Construction: Construct a donor plasmid containing a promoterless 2A-GFP sequence. This cassette must be flanked by homology arms (900 bp recommended) that are homologous to the sequences immediately upstream and downstream of the GAPDH target site. This design ensures that GFP is expressed only upon correct in-frame integration, driven by the endogenous GAPDH promoter [9].

- Cell Transfection:

- For PK15 and 3D4/21 cell lines: Co-transfect the PX330-GAPDH-sgRNA plasmid and the donor vector at a 1:1 ratio using Lipofectamine 2000.

- For Primary PFFs: Use electroporation (175 V/20 ms) to co-deliver the plasmids.

- Selection and Expansion: At 48 hours post-transfection, add G418 (700 µg/mL) to the culture medium for 3 days to select for cells that have incorporated the donor vector.

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): Harvest the selected cells and use FACS to isolate a pure population of GFP-positive cells. These cells can then be expanded for further analysis [9].

- Validation:

- Immunofluorescence (IF): Confirm the co-localization of GFP and GAPDH signals using specific antibodies.

- Western Blot: Analyze protein lysates from sorted cells with anti-GFP and anti-GAPDH antibodies to verify the expression of both the endogenous GAPDH and the GFP-fusion protein [9].

Protocol 2: Enhancing CRISPR/GFP Workflow Efficiency with RAD51

To overcome variable editing efficiencies, particularly for knock-in strategies, co-expression of the homologous recombination protein RAD51 can be highly beneficial. This protocol is adapted from a study showing elevated CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing efficiency with exogenous RAD51 [10].

I. Research Reagent Solutions Table 4: Essential Reagents for RAD51-Enhanced Editing

| Reagent | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| lentiCRISPR-RAD51-GFP Plasmid | An all-in-one vector constitutively expressing Cas9, a specific sgRNA, and RAD51 via 2A peptides, along with a puromycin resistance marker [10]. |

| Puromycin | Selective antibiotic for cells containing the CRISPR plasmid. |

| T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) | Enzyme for detecting indel mutations and assessing cutting efficiency. |

II. Step-by-Step Workflow

- Vector Construction: Generate an all-in-one CRISPR/Cas9-RAD51 plasmid. This involves cloning an E2A-RAD51-T2A-EGFP cassette into a lentiCRISPR vector, downstream of the Cas9 sequence, creating a quad-cistronic expression system (Cas9-RAD51-EGFP-PuroR) [10].

- Cell Transfection and Selection: Transfect the construct into your target cell line (e.g., HEK293T). After 48 hours, replace the medium and add puromycin to select for successfully transfected cells for 72 hours.

- Efficiency Analysis:

- T7E1 Assay: Harvest genomic DNA from selected cells. Amplify the genomic region surrounding the CRISPR target site by PCR. Denature and reanneal the PCR products to form heteroduplexes. Treat with T7E1 enzyme and analyze the cleavage products by gel electrophoresis. A higher proportion of cleaved bands indicates a higher rate of indel formation, signifying improved editing efficiency [10].

- Sequencing: Clone the PCR products and perform Sanger sequencing on multiple colonies to precisely quantify the editing efficiency and the spectrum of induced mutations [10].

Molecular Mechanism of Targeted Integration

The following diagram illustrates the key molecular steps that occur during homology-directed repair (HDR) for precise GFP cassette integration into a target locus like GAPDH, and how RAD51 enhances this process.

The strategic selection of high-expression, phenotypically neutral loci such as GAPDH is a critical factor for the success of visual screening in CRISPR experiments. The protocols outlined here provide a reliable framework for achieving efficient GFP reporter knock-in and robust expression. Furthermore, the integration of enhancing strategies, like RAD51 co-expression, can significantly increase editing efficiency, reducing screening effort and time. By adopting these targeted approaches, researchers can generate more consistent and interpretable data, thereby accelerating discoveries in functional genomics and drug development.

The efficacy of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing is fundamentally dependent on the coordinated delivery and performance of its two core components: the Cas nuclease and the guide RNA (gRNA). Achieving high editing efficiency requires a careful balance between sufficient Cas9 expression and the use of highly efficient, specific gRNAs. This balance is particularly critical in experiments involving visual screening with fluorescent markers like GFP, where editing outcomes must be accurately and efficiently tracked. This protocol provides detailed methodologies for optimizing CRISPR component delivery and validation, with specific application to visual screening systems. We present optimized parameters for achieving high knockout efficiencies across single and multiple genes, quantitative frameworks for gRNA selection, and practical tools for implementation in research settings.

Core Optimization Strategies

Establishing a High-Efficiency Cas9 Expression System

A doxycycline-inducible spCas9-expressing human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC-iCas9) system provides tunable nuclease expression with significant advantages over constitutive systems. Through systematic optimization of critical parameters, this system achieved remarkable efficiency: 82–93% stable INDELs (Insertions and Deletions) for single-gene knockouts, over 80% for double-gene knockouts, and up to 37.5% homozygous knockout efficiency for large DNA fragment deletions [13].

Key optimized parameters in the hPSC-iCas9 system include:

- Cell tolerance to nucleofection stress: Pre-optimization of cell viability post-electroporation

- Transfection methodology: Use of chemical synthesized and modified sgRNA (CSM-sgRNA) with 2’-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications at both 5’ and 3’ ends to enhance sgRNA stability

- Nucleofection frequency: Implementation of repeated nucleofection 3 days after initial transfection

- Cell-to-sgRNA ratio: Optimization of the relationship between cell numbers and sgRNA quantities [13]

gRNA Design and Validation Framework

gRNA design critically impacts editing efficiency. Experimental validation of three widely used gRNA scoring algorithms demonstrated that Benchling provided the most accurate predictions for sgRNA efficiency [13]. However, algorithm predictions alone are insufficient, as evidenced by the discovery of an ineffective sgRNA targeting exon 2 of ACE2 that exhibited 80% INDELs but retained ACE2 protein expression [13]. This highlights the necessity of experimental validation through Western blotting or functional assays to confirm protein knockout rather than relying solely on INDEL frequency.

Table 1: Comparison of gRNA Design and Optimization Approaches

| Approach | Key Features | Efficiency Outcomes | Validation Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro transcribed sgRNA (IVT-sgRNA) | Standard transcription method | Variable efficiency; subject to degradation | INDEL analysis via T7EI assay or sequencing |

| Chemical synthesized modified sgRNA (CSM-sgRNA) | 2’-O-methyl-3'-thiophosphonoacetate modifications at 5'/3' ends | Enhanced stability and editing efficiency | Protein-level validation (Western blot) |

| Dual-gRNA approach | Two gRNAs targeting same gene or adjacent loci | Up to 80% efficiency for double knockouts; large fragment deletion | PCR confirmation of deletion size |

| Algorithm-predicted gRNAs | Benchling, CCTop, or other prediction tools | Varies by algorithm accuracy | Multi-level validation (INDEL + protein) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Rapid Screening of CRISPR Editing Outcomes Using Fluorescent Protein Conversion

This protocol adapts a system for distinguishing DNA damage repair outcomes by converting enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) to blue fluorescent protein (BFP) through targeted mutation, enabling rapid assessment of gene knockout efficiency [14].

Materials

- eGFP-positive cell line

- CRISPR-Cas9 components (Cas9 + gRNAs targeting eGFP)

- Tissue culture equipment and reagents

- Flow cytometer with appropriate filters for eGFP and BFP

- Nucleofection system or transfection reagent

Methodology

Day 1: Cell Preparation

- Culture eGFP-positive cells to 80-90% confluency in appropriate medium.

- Dissociate cells using 0.5 mM EDTA or appropriate dissociation reagent.

- Count cells and resuspend at desired concentration for transfection.

Day 2: Transfection

- Prepare transfection complexes:

- For RNP delivery: Complex 5μg of purified Cas9 protein with 2μg of sgRNA targeting eGFP (sequence designed to convert eGFP to BFP) for 10 minutes at room temperature.

- For plasmid delivery: Use 2-5μg of plasmid expressing both Cas9 and sgRNA.

- Transfect using optimized method (nucleofection program CA137 for hPSCs or lipid-based transfection for other cell types).

- Plate transfected cells in appropriate growth medium.

Day 3-6: Expression and Analysis

- Allow cells to recover and express edited phenotypes for 72-96 hours.

- Analyze cells using flow cytometry to detect eGFP loss and BFP gain.

- Calculate editing efficiency as percentage of BFP-positive cells or eGFP-negative cells.

- Isolate successfully edited populations using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) if needed [14].

Protocol: Optimized Dual-gRNA Delivery for Enhanced Knockout Efficiency

This protocol describes an optimized approach for delivering two gRNAs simultaneously to enhance knockout efficiency, using FolicPolySpermine nanoparticles as a delivery vehicle [15].

Materials

- FolicPolySpermine nanoparticles (spermine, polyethylene glycol, and folic acid-based)

- Two gRNAs targeting adjacent sites in the gene of interest

- Cas9 expression plasmid or Cas9 protein

- HEK293T cells or other relevant cell line

- Restriction enzymes (FastDigest BpiI) for cloning

- PCR amplification and sequencing reagents

Methodology

Step 1: gRNA Design and Cloning

- Design two gRNAs targeting adjacent regions (within 2.2 kb) of the target gene using http://crispr.mit.edu/ or Benchling.

- Synthesize sense and antisense oligonucleotides for each gRNA, hybridize to form duplexes.

- Clone each duplex into the restriction site of FastDigest BpiI in the PX458 (Addgene #48138) expression plasmid using standard molecular biology techniques.

- Verify successful cloning by colony PCR and direct sequencing.

Step 2: Nanoparticle Preparation and Transfection

- Prepare FolicPolySpermine nanoparticles according to established protocols [15].

- Complex nanoparticles with CRISPR plasmids (2-5μg total DNA) at optimal weight ratios.

- Transfect HEK293T cells (or target cell line) using nanoparticle complexes.

- Include controls transfected with lipofectamine 2000 for comparison.

Step 3: Validation and Analysis

- Harvest cells 72-96 hours post-transfection.

- Extract genomic DNA and perform PCR amplification across the target region.

- Analyze deletion efficiency via gel electrophoresis (size shift) and Sanger sequencing.

- Confirm protein knockout via Western blotting if antibodies are available [15].

Quantitative Framework for gRNA Selection

The following table summarizes key efficiency metrics for different CRISPR delivery and gRNA selection approaches, enabling evidence-based experimental design:

Table 2: Efficiency Metrics for CRISPR Delivery and gRNA Selection Approaches

| Parameter | High-Efficiency Benchmark | Key Factors Influencing Efficiency | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-gene knockout | 82-93% INDELs [13] | gRNA efficiency, Cas9 delivery method, cell type | ICE analysis, TIDE |

| Dual-gene knockout | >80% efficiency [13] | gRNA pairing, distance between targets | PCR, sequencing |

| Large fragment deletion | Up to 37.5% homozygous knockout [13] | Distance between gRNAs (up to 2.2 kb) | PCR product size analysis |

| gRNA prediction accuracy | Benchling most accurate [13] | Algorithm selection, on-target score | Experimental validation |

| Ineffective gRNA detection | 80% INDELs with protein retention [13] | Reading frame shifts, protein domains | Western blot |

Visual Workflows for Experimental Planning

The following diagrams illustrate key experimental workflows and relationships in CRISPR component delivery and screening.

Diagram 1: CRISPR Workflow with Fluorescent Screening

Diagram 2: gRNA Efficiency Balance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Component Delivery and Screening

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Systems | Doxycycline-inducible spCas9 hPSCs | Tunable Cas9 expression; reduces cytotoxicity |

| gRNA Synthesis | Chemical synthesized modified sgRNA (CSM-sgRNA) | Enhanced nuclease resistance; improved stability |

| Delivery Vehicles | FolicPolySpermine nanoparticles | Targeted, efficient CRISPR plasmid delivery [15] |

| Delivery Vehicles | Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) | High-efficiency in vivo delivery; suitable for redosing [16] |

| Fluorescent Reporters | eGFP-to-BFP conversion system | Rapid visual screening of editing outcomes [14] |

| Analysis Algorithms | ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) | Accurate INDEL quantification from sequencing data [13] |

| Analysis Algorithms | Benchling gRNA designer | Predictive scoring of gRNA efficiency [13] |

| Cloning Systems | PX458 (Addgene #48138) | All-in-one Cas9 and gRNA expression vector [15] |

Within the field of molecular biology, particularly in the visual screening of CRISPR transformants, Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) has established itself as a pivotal reporter tool. This application note delineates the specific scenarios where GFP-based screening offers significant advantages over traditional selection methods, such as antibiotic resistance or phenotypic assays. We detail the quantitative performance metrics of GFP screening, provide a comprehensive protocol for its implementation in CRISPR/SpCas9 workflows, and visualize the core methodology. By synthesizing current research, we aim to equip researchers with the knowledge to effectively apply GFP screening to accelerate the isolation of genetically modified cells.

The advent of fluorescent proteins has revolutionized the tracking of gene expression and the selection of engineered cells. While traditional methods often rely on antibiotic selection, which confirms the presence of a resistance marker but not the functional expression of the cargo gene, GFP screening provides a direct, visual, and often quantitative readout of successful genetic modification [1]. In the specific context of CRISPR/Cas9 research, this allows researchers to directly screen for cells that are not only transformed but are also actively expressing the Cas9 machinery, thereby increasing the likelihood of successful editing [17]. However, the technique is not without its limitations, including potential interference with Cas9 activity and challenges in identifying Cas9-free edited progeny. This document explores the balance of these advantages and limitations, providing a framework for researchers to determine when GFP screening is the most effective tool.

Key Advantages and Documented Superiority of GFP Screening

GFP screening provides several distinct advantages that make it superior to traditional methods in many experimental contexts.

Direct, Rapid, and Non-Destructive Visualization

The most significant advantage of GFP is the ability to visually identify positive transformants in real-time without harming the cells. This non-destructive quality allows for the tracking of gene expression kinetics and the easy isolation of live, positive cells for further expansion and analysis. A 2025 study on plant CRISPR systems directly contrasted this with antibiotic selection, finding that screening with GFP or RNA aptamers provided a more direct method for identifying positive T1 transformants than selection with hygromycin resistance alone [17].

Quantitative and High-Throughput Capabilities

GFP serves not just as a qualitative marker but also as a quantitative reporter of gene expression. Flow cytometric measurement of GFP fluorescent intensity has been shown to be directly proportional to both GFP mRNA abundance and the underlying gene copy number, enabling precise assessment of promoter activity [1]. This facilitates high-throughput screening, as demonstrated by automated systems like the QPix 400 series, which can pick over 3,000 colonies per hour based on user-defined fluorescence intensity thresholds, a five-fold increase over manual picking [18].

Enabling Complex Functional Assays

GFP-based readouts can be engineered into sophisticated assays that go beyond simple transformation. For instance, the FAST (Fluorescent Assembly of Split-GFP for Translation Tests) method uses the complementation of GFP1-10 and GFP11 fragments to detect cell-free protein synthesis with a sensitivity of 8 ± 2 pmol of polypeptide, a use case where traditional radioactive labeling would be hazardous and complex [19]. Similarly, split-GFP systems have been adapted to quantify the display of proteins on the microbial cell surface, a task difficult to accomplish with conventional immunoassays that require costly and time-consuming antibody generation [20].

Inherent Limitations and Challenges

Despite its power, GFP screening is not a universal solution and possesses several key limitations that researchers must consider.

Technical Complexity and False Signals

A primary challenge is the potential for false positives and negatives. In the plant CRISPR study, the conventional GFP/Cas9 system had a 40% omission rate, failing to identify many positive transformants that were detected via genomic PCR. This was attributed to the incomplete cleavage of the 2A peptide linking GFP to Cas9, which can impair Cas9 activity and reduce fluorescence [17]. Furthermore, fluorescence can be detected if the fluorescent protein is retained in the cytoplasm, obscuring accurate localization in surface display experiments [20].

Potential for Interference and Stability Issues

The relatively large size of GFP (∼25 kDa) can potentially interfere with the function, folding, or localization of the protein it is fused to. This has spurred the development of smaller RNA aptamer reporters as alternatives [17]. Additionally, GFP fluorescence is dependent on chromophore maturation, which has a slow rate compared to protein folding kinetics, potentially delaying the readout [19]. GFP fluorescence can also be disrupted by certain small-molecule drugs, such as the covalent kinase inhibitors osimertinib, afatinib, and neratinib, which can confound results in drug screening assays [21].

Inability to Directly Isolate Cas9-Free Progeny

In CRISPR workflows, a critical goal is to identify edited organisms that have segregated away from the Cas9 transgene. A GFP signal linked to Cas9 expression makes it impossible to distinguish between a Cas9-positive plant and a Cas9-free, edited plant in the T2 generation, necessitating additional molecular screening to confirm the loss of the transgene [17].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of GFP Screening vs. Traditional Selection in Documented Studies

| Experimental Context | GFP Screening Performance | Traditional Method Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR T1 Transformant Selection | 60% identification accuracy (40% omission rate) | Hygromycin resistance: 100% selection efficiency but includes escapes | [17] |

| Bacterial Colony Picking | >3,000 colonies/hour; selection based on fluorescence intensity | ~600 colonies/hour manually; selection based on visual phenotype | [18] |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis | Sensitivity: 8 ± 2 pmol of polypeptide; non-hazardous | Radioactive labeling: hazardous, technically complex, time-consuming | [19] |

| Microbial Surface Display | One-step, no antibody cost; quantitative via flow cytometry | Immunoassays: costly antibodies, multiple washing steps, hours to complete | [20] |

Application Note: GFP Screening in a CRISPR/SpCas9 Workflow

The following protocol is adapted from a 2025 study that developed an RNA aptamer-assisted CRISPR/Cas9 system, with steps relevant to GFP screening detailed for the isolation of positive Arabidopsis thaliana T1 transformants [17].

Experimental Workflow

The diagram below outlines the key steps for screening CRISPR transformants using a GFP reporter system.

Detailed Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Vector Construction and Transformation

- Clone your gene of interest and the sgRNA(s) into a CRISPR vector where the Cas9 gene is fused in-frame to the GFP reporter gene via a self-cleaving 2A peptide (e.g., P2A, T2A).

- Introduce the constructed vector into your target organism. For Arabidopsis thaliana, use the Agrobacterium-mediated floral dip method [17].

Step 2: Primary Selection and Screening

- After transformation, harvest T1 seeds and plate on solid MS medium containing the appropriate antibiotic (e.g., hygromycin) to select for transformants.

- Grow seedlings under standard conditions for 7-10 days.

- Screen the antibiotic-resistant seedlings for GFP fluorescence using a fluorescent stereomicroscope with a standard GFP filter set (Ex/Em: ~488/507 nm).

- Note: The user-defined fluorescence threshold is critical. The QPix 400 system, for example, allows setting a minimum Mean Fluorescence Intensity (e.g., >40,000) for automated picking [18].

Step 3: Validation and Downstream Analysis

- Carefully collect the GFP-positive seedlings and transfer them to soil for expansion.

- Extract genomic DNA from leaf tissue of the expanded positives.

- Perform PCR amplification of the target genomic region and validate editing efficiency via sequencing (e.g., Sanger or NGS).

- Critical Limitation Check: Be aware that fluorescence indicates Cas9 expression, not necessarily successful editing. Furthermore, the 2A peptide linkage may be incomplete, leading to false negatives and reduced Cas9 activity [17]. Always confirm edits molecularly.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for GFP Screening in CRISPR Workflows

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Protocol | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/GFP Vector | Expresses Cas9, sgRNA, and GFP reporter. | Plasmid with Cas9-P2A-GFP fusion; available from Addgene. P2A peptide allows co-translational cleavage. |

| Selection Antibiotic | Primary selection for transformants. | Hygromycin for plants; Ampicillin or Kanamycin for bacterial systems. |

| Fluorescence Microscope | Visualization and manual picking of GFP+ cells/colonies. | Requires standard GFP filter set (Ex ~488 nm, Em ~507 nm). |

| Automated Colony Picker | High-throughput, quantitative screening of colonies. | QPix 400 Series with fluorescence module; allows setting intensity thresholds [18]. |

| Split-GFP Components | For detecting protein expression, display, or interactions. | GFP1-10 (25 kDa) and GFP11 (16 aa) fragments; used in FAST and surface display assays [19] [20]. |

| Fluorescence-Compatible Plates | For quantitative assays in cell culture or liquid samples. | Black-walled, clear-bottom plates for reading in plate readers. |

GFP screening outperforms traditional selection methods by providing direct, quantitative, and non-destructive visualization of gene expression, which is invaluable for high-throughput workflows and functional assays in CRISPR research. Its primary advantages lie in speed, visual confirmation, and the rich quantitative data it provides. However, limitations such as the potential for false negatives due to fusion protein issues, the inability to screen for Cas9-free edits, and the size of the GFP protein itself necessitate a complementary approach. Researchers are advised to use GFP screening as a powerful first-pass filter but to always couple it with robust molecular validation techniques to confirm genuine genetic edits.

Implementing GFP-Based CRISPR Screens: From FACS to High-Throughput Workflows

In the field of functional genomics and drug discovery, CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing has revolutionized target identification and validation. A critical step in this process is the rapid and accurate assessment of DNA repair outcomes following CRISPR-induced DNA breaks. Fluorescence-based screening pipelines provide a powerful solution, enabling researchers to distinguish between different gene editing results efficiently and at scale [22].

This protocol details the establishment of a fluorescence-based screening pipeline using an enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (eGFP) to Blue Fluorescent Protein (BFP) conversion system. The core principle leverages the fact that successful gene editing alters the fluorescent phenotype of cells, allowing for straightforward differentiation between various DNA repair outcomes. This method is particularly valuable for high-throughput assessment of gene editing techniques, which is crucial for pharmaceutical and biotechnology research [14].

The system is designed to distinguish between two primary DNA repair pathways:

- Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), which typically results in gene knockout (loss of fluorescence).

- Homology-directed repair (HDR), which can lead to precise gene correction or mutation (shift from green to blue fluorescence) [14].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of this screening pipeline relies on several crucial reagents and their specific functions, as outlined in the table below.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Their Functions in the Fluorescence Screening Pipeline

| Reagent / Component | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| eGFP Reporter Cell Line | Provides the chromosomal target for CRISPR-Cas9 editing; successful editing alters its fluorescent signal [14]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | RNA-guided endonuclease that creates a precise double-strand break in the DNA at the target eGFP locus [22]. |

| sgRNA Targeting eGFP | Directs the Cas9 nuclease to the specific sequence within the eGFP gene that is to be modified [14]. |

| HDR Donor Template | A DNA template containing the desired BFP mutation; used by the cell's repair machinery to convert eGFP to BFP [14]. |

| Fluorogenic Proteins (e.g., tdTomato-tDeg) | Engineered fluorescent proteins that become stable and fluorescent only upon binding to a specific RNA aptamer (e.g., Pepper), drastically reducing background noise in imaging applications [23]. |

| Pepper-fused sgRNA | A modified sgRNA that incorporates the Pepper RNA aptamer; it recruits and stabilizes the fluorogenic protein, enabling high-contrast imaging of genomic loci [23]. |

| dCas9 (Nuclease-deficient Cas9) | A catalytically "dead" Cas9 that can target genomic DNA without cutting it; serves as a platform for fluorogenic CRISPR (fCRISPR) imaging systems [23]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and key decision points of the fluorescence-based screening protocol, from cell preparation to final analysis.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Protocol for Screening CRISPR-Cas9 Outcomes via eGFP to BFP Mutation

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for distinguishing between NHEJ-induced gene knockout and HDR-induced gene mutation in a cell population [14].

Table 2: Step-by-Step Protocol for Fluorescence-Based Screening

| Step | Procedure | Key Parameters | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cell Preparation | Culture and maintain eGFP-positive cells. Ensure high viability and optimal confluency (e.g., 70-80%) before transfection. | Cell line of choice, growth medium, cell viability >95%. | To provide a uniform, healthy population of cells expressing the target eGFP gene. |

| 2. Transfection | Co-transfect cells with plasmids encoding: a) Cas9 nuclease, b) sgRNA targeting the eGFP gene, and c) HDR donor template for BFP conversion. | Use optimized transfection reagent or method (e.g., lipofection, electroporation). Controls (e.g., sgRNA only) are essential. | To deliver the gene editing machinery and donor template into the cells to initiate the DNA break and repair process. |

| 3. Incubation & Expression | Incubate transfected cells for a sufficient period (e.g., 48-72 hours) to allow for DNA repair, expression, and maturation of the new fluorescent protein (BFP). | Standard cell culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂). BFP maturation time. | To enable the cellular repair mechanisms (NHEJ or HDR) to act and for the resulting fluorescent phenotypes to manifest. |

| 4. Analysis & Sorting | Analyze cells using flow cytometry or fluorescence microscopy. Measure fluorescence in eGFP and BFP channels. | Use appropriate laser/filter sets for eGFP (Ex/~488nm, Em/~510nm) and BFP (Ex/~405nm, Em/~450nm). | To identify and quantify the proportions of cells that have undergone successful HDR (BFP+), NHEJ (non-fluorescent), or no editing (eGFP+). |

| 5. Data Interpretation | Calculate editing efficiencies based on the population shifts in fluorescence. | % BFP+ cells = HDR efficiency; % non-fluorescent cells = NHEJ efficiency. | To quantitatively assess the outcomes and efficacy of the gene editing procedure. |

Advanced Imaging with Fluorogenic CRISPR (fCRISPR)

For high-contrast imaging of genomic loci, such as visualizing the site of CRISPR action, a fluorogenic CRISPR (fCRISPR) system is recommended. This method offers superior signal-to-noise ratio compared to conventional methods using constitutively fluorescent proteins [23].

System Design: The fCRISPR system employs three components:

- dCas9: Catalytically dead Cas9 for targeting without cutting.

- Modified sgRNA: The sgRNA scaffold is engineered with inserted Pepper RNA aptamers in the tetraloop and stem-loop 2.

- Fluorogenic Protein: A fluorescent protein (e.g., tdTomato) fused to an unstable degron domain (tDeg). This protein is rapidly degraded unless bound to the Pepper aptamer.

Imaging Procedure:

- Co-transfect cells with plasmids expressing the Pepper-fused sgRNA, dCas9, and the tdTomato-tDeg fluorogenic protein.

- The dCas9:sgRNA complex binds the target genomic DNA.

- The Pepper aptamer on the sgRNA recruits and binds the tdTomato-tDeg protein, concealing its degron. This binding stabilizes the protein and activates its fluorescence specifically at the target locus.

- Image the cells using standard fluorescence microscopy. The fCRISPR system produces bright, specific puncta against a very low background, as unbound fluorogenic proteins are degraded [23].

Data Analysis and Presentation

Effective presentation of quantitative data is crucial for interpreting screening results. The following table and descriptions outline standard methods for data summarization and visualization.

After analysis, data should be summarized by group (e.g., different experimental conditions or editing outcomes). A key numerical summary is the difference between means (or medians) of the compared groups [24].

Table 3: Generalized Structure for Presenting Quantitative Data from a Screening Experiment

| Experimental Group | Mean Editing Efficiency (%) | Standard Deviation | Sample Size (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Condition A | Value | Value | Value |

| Condition B | Value | Value | Value |

| Difference (A - B) | Value | -- | -- |

Data Visualization Techniques

Choosing the right graph is essential for comparing quantitative data across different groups [24]:

- Boxplots: The best general choice for displaying distributions and comparing medians, quartiles, and ranges between multiple groups. They readily show outliers and the overall spread of data [24].

- 2-D Dot Charts: Ideal for small to moderate amounts of data, as they show individual data points, preventing the loss of detail that can occur with summary graphics like boxplots. Points are often jittered or stacked to avoid overplotting [24].

- Back-to-Back Stemplots: A good option for small datasets when comparing only two groups, as they preserve the original data values [24].

Application in Drug Discovery

This fluorescence-based screening pipeline is highly applicable in pharmaceutical research. It can be used to:

- Identify and validate new biological targets for precision medicines through functional genomic screening [22].

- Understand drug resistance and sensitivity mechanisms ahead of clinical trials by performing positive selection screens for genes that confer resistance to a cytotoxic agent [22].

- Define gene essentiality in specific cancer cell lines, creating a landscape of gene dependency which can inform therapeutic strategies (a classic negative selection screen) [22].

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) has become an indispensable tool for modern biological research, particularly in the field of CRISPR-based genetic engineering. The ability to isolate specific cellular populations based on fluorescent markers such as Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) enables researchers to study gene function, protein localization, and cellular responses with remarkable precision. Within the context of CRISPR transformant screening, FACS provides a powerful method for identifying successfully edited cells, characterizing editing efficiencies, and isolating transgene-free progeny for downstream applications. This application note details established protocols and strategic considerations for effective FACS-based enrichment of GFP-positive and GFP-negative populations, with a specific focus on applications in CRISPR-Cas9 visual screening. The integration of these techniques is crucial for advancing functional genomics and accelerating the development of genetically engineered organisms for both basic research and therapeutic purposes.

Key Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows for standard GFP-based sorting and for addressing the common challenge of cellular autofluorescence.

Core FACS Workflow for CRISPR Screening

Gating Strategy to Exclude Autofluorescence

Critical Reagents and Equipment

The success of FACS-based enrichment relies on a well-characterized set of reagents and instruments. The following toolkit outlines essential components.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for FACS-Based GFP Sorting

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GFP Reporter Construct | Visual marker for CRISPR delivery and success; co-expressed with Cas9 | Can be linked via 2A self-cleaving peptide or expressed from a separate promoter [17] |

| Cell Dissociation Reagent | Generation of high-quality single-cell suspension | Accutase is preferred over trypsin as it dislodges cells without damaging surface proteins [25] |

| Viability Stain | Discrimination and exclusion of dead cells | Propidium Iodide or DAPI; critical for improving sort purity and downstream cell health |

| FACS Buffer | Maintains cell viability and prevents clumping during sort | PBS + 1% FBS + 2.5 mM EDTA + 25 mM HEPES [26] [25] |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter | Instrument for analyzing and physically separating cells | Standard commercial FACS machines (e.g., BD Influx) are suitable; no custom FADS required [27] [28] |

| Sort Collection Tubes | Receives sorted cell populations while maintaining sterility and viability | Tubes pre-filled with collection medium (e.g., PBS + 1% FBS or culture medium) [25] |

Comparative Performance of Enrichment Strategies

Different screening and enrichment strategies offer distinct advantages in terms of efficiency, accuracy, and applicability. The quantitative data below compares several approaches.

Table: Quantitative Comparison of Fluorescence-Based Sorting Strategies

| Method / System | Reported Enrichment Efficiency | Key Advantages | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional GFP/Cas9 | 40% omission rate in T1 transformant identification [17] | Established, widely used protocol | General CRISPR screening in plant and mammalian cells [17] |

| RNA Aptamer (3WJ-4×Bro/Cas9) | 78.6% increase in T1 mutation rate vs. GFP/Cas9; 30.2% improved Cas9-free mutant sorting [17] | Higher accuracy; avoids fluorescent protein interference with Cas9 activity | Plant genome editing, particularly for selecting transgene-free edited lines [17] |

| Autofluorescence-Restrictive Gating | Up to 7-fold enrichment of true eGFP+ cells vs. standard protocol [26] | Effectively excludes false positives from intrinsically autofluorescent cells (e.g., RPE) | Gene therapy assessment in hard-to-transduce, autofluorescent cell types [26] |

| MACS Pre-enrichment | Can increase target cell frequency >30-fold before FACS [29] | Higher cell yield (91-93% vs. ~30% for FACS); faster for multiple samples [28] | High-yield preliminary enrichment when ultimate purity is not required [28] [29] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Basic Protocol: Standard FACS for GFP+ CRISPR Transformants

This protocol is adapted from established methods for sorting live mammalian cells based on surface and intracellular markers [25].

Materials:

- Library of mutant cells (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9 transfected)

- Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS)

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS, without Ca²⁺ or Mg²⁺)

- Accutase cell detachment solution

- FACS Buffer: PBS + 1% FBS

- Viability stain (e.g., Propidium Iodide)

- Sterile cell strainer (50 μm pore size)

- Sterile flow cytometry and collection tubes

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Plate the mutant cell library a day before sorting to ensure optimal cell health and confluency. On sorting day, harvest adherent cells by aspirating media, washing with PBS, and adding Accutase (1 mL/10-cm dish). Incubate at 37°C for 5-10 minutes until cells detach. Neutralize with complete media. For suspension cells, gently pipette to dissociate clumps [25].

- Washing and Counting: Transfer cell suspension to a conical tube and centrifuge at 300 × g at 4°C for 10 minutes. Aspirate supernatant and resuspend cells in complete media. Count live cells using a hemocytometer and Trypan Blue exclusion.

- Viability Staining: Wash cells twice with ice-cold PBS. Resuspend the final cell pellet in FACS Buffer containing a viability stain (e.g., Propidium Iodide) according to the manufacturer's recommendation. Incubate on ice for 15-30 minutes, protected from light.

- Final Resuspension and Filtration: Centrifuge cells and resuspend in FACS Buffer at a concentration of 1–2 × 10⁷ cells/mL. Gently pipette to disrupt clumps. Pass the cell suspension through a sterile 50 μm cell strainer into a sterile flow cytometry tube to remove any remaining aggregates.

- FACS Sorting: Keep samples on ice and protected from light. Use the unlabeled and single-color controls to set up the instrument and compensate for fluorescence spillover. Implement a sequential gating strategy: (1) FSC-A vs. SSC-A to gate on cells and exclude debris, (2) FSC-H vs. FSC-W to select single cells, (3) viability dye-negative to select live cells, and finally (4) GFP-positive vs. GFP-negative to define the target populations. Sort the desired populations into collection tubes containing an appropriate recovery medium.

- Post-Sort Processing: Return collected cells to sterile culture conditions as soon as possible. It is critical to validate the sort purity by re-analyzing an aliquot of the sorted cells and to confirm the CRISPR editing efficiency via genomic PCR, T7E1 assay, or sequencing.

Alternate Protocol: Sorting GFP+ Cells from Autofluorescent Populations

This protocol is crucial for working with inherently autofluorescent cells, such as Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE) cells, which accumulate autofluorescent granules like lipofuscin [26].

Materials: (In addition to Basic Protocol materials)

- Specific antibodies for potential cell surface markers (optional)

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation and Staining: Follow Steps 1–3 of the Basic Protocol to generate a single, viable cell suspension.

- Advanced Gating Strategy: The key differentiator is the use of a more sophisticated gating approach to distinguish true GFP signal from autofluorescence.

- After selecting for single, live cells, create a plot of the GFP signal (typically FITC or Alexa Fluor 488 channel) versus the signal from a fluorescent channel adjacent to GFP (e.g., PE or PE-Texas Red).

- Autofluorescent granules will typically emit signals detectable in both channels, appearing along a diagonal in this plot.

- True GFP-positive cells will be positive for GFP but low for the adjacent channel, forming a distinct population that can be gated accordingly [26].

- Sorting and Validation: Proceed with sorting as in the Basic Protocol. Post-sort validation is especially critical in this context to confirm that the sorted "GFP-positive" population is indeed enriched for the target cells and not for highly autofluorescent untransfected cells.

Troubleshooting and Technical Considerations

- Low Cell Viability Post-Sort: Ensure the FACS buffer contains EDTA and protein (e.g., FBS, BSA), all solutions are ice-cold, and the time from cell harvesting to final collection is minimized. Maintaining sorted cells on ice after collection is also vital [25].

- Poor Sort Purity: Always include control samples (untransfected/unlabeled cells) to accurately set sorting gates. The use of a viability dye is non-negotiable for excluding dead cells, which often exhibit non-specific fluorescence and stick to live cells, causing contamination. Re-analysis of a sorted sample aliquot is the best practice to confirm purity.

- Low Yield/High Cell Loss: FACS is inherently a lower-yield method compared to magnetic sorting (MACS), with reported cell losses around ~70% for FACS versus 7–9% for MACS [28]. If high cell numbers are the priority for downstream applications, consider a pre-enrichment step with MACS where possible, or ensure you begin with a sufficiently large input cell number.

- Sample Transfer Time: For samples being processed off-site, shorter transfer times significantly improve FACS success. One study on multiple myeloma samples showed a 77.1% success rate for transfer times <2 hours, compared to 67.8% for longer times [30].

In CRISPR-based functional genomics, the design of sgRNA libraries and the achievement of sufficient sgRNA coverage are fundamental to screening success. Library design determines the comprehensiveness and specificity of genetic perturbations, while coverage ensures that screening results are statistically robust and reproducible. These factors are particularly crucial in visual screening systems utilizing fluorescent markers like eGFP, where precise editing outcomes must be accurately quantified across large cell populations. Optimal library design and coverage enable researchers to distinguish between different DNA repair outcomes, identify key genetic regulators, and unravel complex biological mechanisms in disease contexts such as cancer [31] [32] [33].

The integration of visual reporters like eGFP provides a powerful tool for rapid assessment of editing efficiency. In these systems, successful homology-directed repair (HDR) can convert eGFP to blue fluorescent protein (BFP), while non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) typically results in loss of fluorescence, creating a dual-readout system that enables high-throughput screening of editing outcomes [14] [32]. This approach allows researchers to simultaneously evaluate both gene knockout and specific gene correction events, providing critical insights for developing genome editing therapies.

Principles of sgRNA Library Design

Library Size and Composition

Effective sgRNA libraries balance comprehensiveness with practical feasibility. Genome-wide libraries systematically target thousands of genes, while focused libraries interrogate specific pathways or gene sets. The number of sgRNAs per gene represents a critical design parameter, with traditional libraries employing 4-10 sgRNAs per gene to ensure effective perturbation [33]. However, recent advances demonstrate that smaller, more optimized libraries can perform equivalently or superior to larger conventional libraries.

Table 1: Comparison of CRISPR Library Designs and Performance

| Library Name | sgRNAs per Gene | Library Size | Performance Notes | Optimal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brunello [33] | 4 | Standard | Balanced performance | General genome-wide screening |

| Yusa v3 [33] | 6 | Large | Comprehensive but lower efficacy in some tests | Applications requiring maximum coverage |

| Vienna-single [33] | 3 | Reduced by 50% | Stronger depletion of essential genes than larger libraries | Cost-sensitive studies; limited cell material |

| Vienna-dual [33] | 3 pairs | Reduced by 50% | Strongest performance in essentiality and drug-gene interaction screens | Enhanced knockout efficiency needed |

| MinLib [33] | 2 | Minimal | Potential best performance per guide | Extreme library compression required |

Recent benchmarking studies reveal that libraries with fewer sgRNAs per gene, when selected using principled criteria like Vienna Bioactivity CRISPR (VBC) scores, can outperform larger conventional libraries. The top3-VBC library (3 guides per gene) demonstrated stronger depletion of essential genes than the Yusa v3 6-guide library, highlighting that guide quality supersedes quantity [33]. This library compression enables more cost-effective screens with reduced reagent and sequencing costs, increased throughput, and improved feasibility for applications with limited material such as organoids or in vivo models.

Dual vs. Single Targeting Strategies

Dual-targeting libraries, where two sgRNAs target the same gene, can enhance knockout efficiency through deletion of the inter-sgRNA genomic region. Evidence indicates that dual-targeting guides produce stronger depletion of essential genes and weaker enrichment of non-essential genes compared to single-targeting approaches [33]. However, this strategy may trigger a heightened DNA damage response due to creating twice the number of double-strand breaks, potentially introducing confounding fitness effects in certain screening contexts.

The performance advantage of dual-targeting appears most pronounced when pairing less efficient guides with more efficient ones, effectively compensating for variable guide efficacy. Interestingly, the benefit of dual-targeting was largely absent when using the highly efficient Vienna-single library guides, suggesting that the approach provides maximal benefit when guide efficacy is suboptimal [33]. The distance between gRNA pairs, either in absolute terms or relative to gene length, shows no clear correlation with efficacy, contradicting earlier reports [33].

Calculating and Achieving Sufficient sgRNA Coverage

Coverage Fundamentals and Requirements

Coverage refers to the number of cells representing each sgRNA in a library, determining the statistical power to detect phenotypic effects. The established gold standard for genome-wide knockout screens is 250x coverage—meaning each unique sgRNA is represented in at least 250 cells [34]. This threshold ensures sufficient representation to distinguish true phenotypic effects from stochastic noise.

Coverage requirements directly determine library size and screening scale. For a genome-wide library targeting ~20,000 human genes with 4 sgRNAs per gene, achieving 250x coverage requires delivering sgRNAs to at least 20 million cells (20,000 genes × 4 sgRNAs × 250 cells) [34]. This substantial cell requirement presents significant challenges for in vivo screens or models with limited cell availability.

Table 2: Coverage Requirements and Computational Tools

| Parameter | Standard Requirement | Minimum Viable | Calculation Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coverage per sgRNA | 250x [34] | Variable by screen type [34] | Statistical power to detect phenotype |

| Cells for genome-wide screen (4 sgRNAs/gene) | 20 million [34] | Lower with optimized libraries [33] | (20,000 genes × 4 sgRNAs × 250 cells) |

| Guide efficacy prediction | VBC scores [33] | Rule Set 3 [33] | Correlation with log-fold changes |

| Performance assessment | Chronos algorithm [33] | MAGeCK [33] | Gene fitness estimates across time series |

Strategies for Optimizing Coverage

Innovative approaches can reduce coverage requirements while maintaining screening quality:

Library Compression: Using minimal libraries with 2-3 highly effective sgRNAs per gene dramatically reduces cell requirements. The Vienna library (3 guides/gene) achieves 250x coverage with approximately 15 million cells for genome-wide screening—a 25% reduction compared to standard 4-guide libraries [33].

Pooled Screening Across Organisms: For in vivo applications where target cells are limited, distributing a genome-wide library across multiple animals can achieve sufficient coverage. One approach divides the library into sub-libraries, each delivered to a separate organism [34]. Alternatively, delivering the complete library to multiple animals increases aggregate coverage while introducing inter-organism variability [34].

Retrospective Coverage Analysis: Analysis of T cell screening data suggests that fitness phenotypes may be detectable below the 250x standard, indicating that required coverage is screen-specific [34]. Factors influencing minimum requirements include cell population heterogeneity and phenotypic selection strength.

Protocol: eGFP to BFP Mutation Reporter System for Assessing Editing Outcomes

Experimental Workflow and Principles

The eGFP to BFP mutation reporter system provides a visual method to simultaneously quantify HDR and NHEJ outcomes in CRISPR-edited cells. This system utilizes a lentivirally delivered eGFP construct integrated into the cellular genome. Designed sgRNAs target the eGFP sequence, while HDR templates introduce specific nucleotide substitutions that convert eGFP to BFP. Successful HDR generates blue fluorescent cells, while NHEJ produces non-fluorescent cells, enabling quantitative assessment of editing outcomes via flow cytometry [14] [32].

Step-by-Step Methodology

Generation of eGFP-Positive Cell Lines

Materials:

- HEK293T cells (or other relevant cell lines)

- Lentiviral vectors: pMD2.G, pRSV-Rev, pMDLg/pRRE, pHAGE2-Ef1a-eGFP-IRES-PuroR [32]

- Polyethylenimine (PEI) transfection reagent

- Complete DMEM medium with 10% FBS

- Puromycin selection antibiotic

Procedure:

- Cell Culture Preparation: Thaw and culture HEK293T cells in complete DMEM medium. Maintain cells below 80% confluency with regular passaging every 3-4 days using trypsin-EDTA detachment [32].

- Lentivirus Production: Co-transfect HEK293T cells with the lentiviral packaging plasmids (pMD2.G, pRSV-Rev, pMDLg/pRRE) and the pHAGE2-Ef1a-eGFP-IRES-PuroR transfer plasmid using PEI transfection reagent [32].

- Viral Harvest and Transduction: Collect viral supernatant 48-72 hours post-transfection. Filter through 0.45μm membrane and transduce target cells with viral supernatant supplemented with 8μg/mL polybrene.