A Comprehensive CRISPR-Cas9 Protocol for Monocot Plants: Advanced Genome Editing in Rice and Maize

This article provides a detailed guide for researchers and scientists on applying CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in monocot plants, specifically rice and maize.

A Comprehensive CRISPR-Cas9 Protocol for Monocot Plants: Advanced Genome Editing in Rice and Maize

Abstract

This article provides a detailed guide for researchers and scientists on applying CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in monocot plants, specifically rice and maize. It covers foundational mechanisms and advantages of CRISPR-Cas9 over traditional methods, then delves into practical protocols for vector design, multiplex editing, and efficient delivery systems like Agrobacterium and biolistics. The guide includes thorough troubleshooting for common issues such as off-target effects and low efficiency, and concludes with robust validation techniques and a comparative analysis of editing outcomes. This protocol aims to empower the development of climate-resilient, high-yielding crop varieties to address global food security challenges.

Understanding CRISPR-Cas9 Systems and Their Superiority for Monocot Genome Editing

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) system represents a revolutionary genome-editing technology derived from the adaptive immune system of bacteria, such as Streptococcus pyogenes [1] [2]. In nature, this system protects bacteria from invading viruses and plasmids by capturing and storing fragments of foreign DNA within the host's CRISPR locus. These fragments are then transcribed and processed into short CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs), which guide Cas nucleases to cleave complementary foreign DNA sequences upon future invasions [1].

Molecular biologists have repurposed this system into a powerful and versatile tool for precise genome engineering in eukaryotic cells, including plants [3]. The core engineered system consists of two key components: the Cas9 endonuclease, which creates double-stranded breaks (DSBs) in DNA, and a synthetic single-guide RNA (sgRNA), which is a fusion of crRNA and a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) [2]. The sgRNA directs Cas9 to a specific genomic locus by base-pairing with a 20-nucleotide target sequence adjacent to a short Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), which is 5'-NGG-3' for the commonly used SpCas9 [1] [4].

The precision and programmability of the CRISPR/Cas9 system have made it an indispensable tool for functional genomics and crop improvement, particularly in monocot cereals like rice and maize which are vital for global food security [1] [5].

Core Mechanism and Application Workflow

The fundamental mechanism of CRISPR/Cas9 action involves the creation of a targeted DSB in the genome, which is subsequently repaired by the cell's endogenous DNA repair machinery. The two primary repair pathways are Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) and Homology-Directed Repair (HDR).

- NHEJ is an error-prone process that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the break site. When these indels occur within the coding sequence of a gene, they can cause frameshift mutations that lead to premature stop codons and effectively knock out the gene's function [1] [2].

- HDR is a more precise pathway that uses a homologous DNA template to repair the break. By co-delivering a designed donor repair template (DRT), researchers can harness HDR to introduce specific nucleotide changes or insert new sequences, achieving gene knock-in or precise base editing [2].

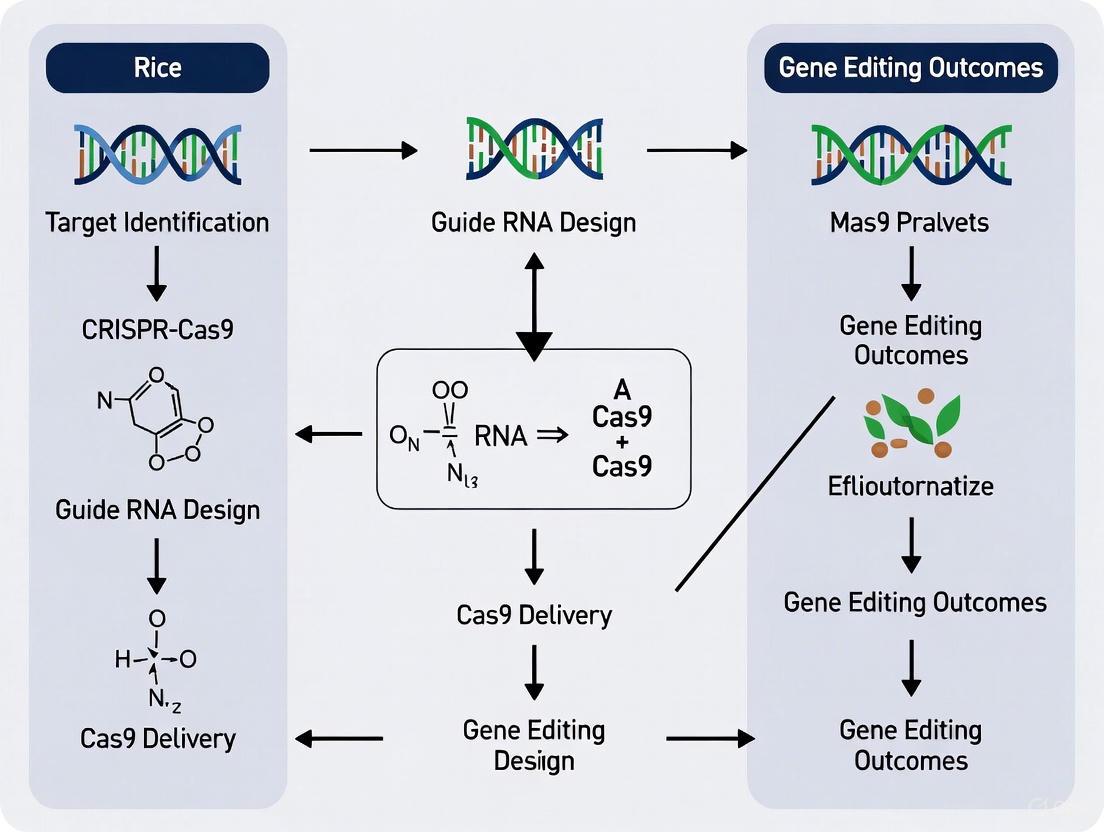

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from sgRNA design to the analysis of edited monocot plants, integrating the core mechanism with practical application steps.

Experimental Protocols for Monocots

The following protocols provide a detailed framework for implementing CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in monocot plants like rice and maize.

Basic Protocol 1: CRISPR/Cas9 Guide RNA Target Selection

This protocol is critical for ensuring high on-target activity and minimal off-target effects [1].

- Sequence Retrieval: Obtain the full genomic sequence of the target gene from a reference database (e.g., Rice Genome Annotation Project for rice, MaizeGDB for maize). Include exon, intron, and promoter regions.

- Target Site Identification: Scan the sequence for all instances of the PAM sequence (5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9). The 20 nucleotides immediately 5' to each PAM are potential sgRNA target sequences.

- Specificity and Efficiency Scoring:

- Use web-based tools like CRISPR-P 2.0 (for rice, maize, wheat), CHOPCHOP, or Cas-Designer to score and rank potential sgRNAs [1] [4].

- Prioritize sgRNAs with high efficiency scores (often correlated with GC content between 40-80%) and no or minimal putative off-target sites in the genome.

- For polyploid species (e.g., wheat), ensure the sgRNA sequence is perfectly conserved across all homoeoalleles or design specific sgRNAs for each allele [1].

- Validation: Design PCR primers flanking the selected target site (amplicon size ~300-500 bp). Amplify and sequence the target region from the specific cultivar being used to confirm the absence of natural polymorphisms that could affect sgRNA binding [1].

Basic Protocol 2: Construction of a Binary Plasmid Vector

This protocol outlines the assembly of a T-DNA vector for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation [1] [4].

- Oligonucleotide Annealing:

- Design complementary oligonucleotides corresponding to the selected 20-nt sgRNA target sequence, adding the appropriate 5' overhangs for your chosen cloning method (e.g., BsaI sites for Golden Gate assembly).

- Phosphorylate and anneal the oligos to form a double-stranded DNA fragment.

- sgRNA Cassette Cloning: Ligate the annealed oligo duplex into a shuttle vector containing a monocot-specific Pol III promoter (e.g., OsU6 or OsU3 for rice, ZmU6 for maize) driving the sgRNA scaffold [4].

- Multiplexing (Optional): For targeting multiple genes, assemble multiple sgRNA expression cassettes using methods like Golden Gate cloning or a polycistronic tRNA-gRNA system (tRNA-based processing) [2] [4].

- Final Vector Assembly: Transfer the assembled sgRNA cassette(s) into a binary T-DNA vector that contains the following components [4]:

- A codon-optimized Cas9 gene under the control of a strong monocot Pol II promoter (e.g., Maize Ubiquitin 1 (ZmUbi1) for constitutive expression).

- A plant selection marker (e.g., Hygromycin phosphotransferase, Hpt) driven by a separate constitutive promoter.

- Sequence Verification: Confirm the final plasmid sequence by Sanger sequencing, paying special attention to the sgRNA target sequence and assembly junctions.

Support Protocol: Plant Transformation and Regeneration

This protocol is for generating genome-edited plants via Agrobacterium [1].

- Vector Mobilization: Introduce the verified binary vector into an Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain suitable for monocot transformation (e.g., EHA105, AGL1) by electroporation or freeze-thaw method.

- Plant Material Preparation: Isolate immature embryos or seed-derived calli from the target rice or maize cultivar. This serves as the explant for transformation.

- Co-cultivation: Inoculate the explants with the Agrobacterium culture harboring the CRISPR/Cas9 vector. Co-cultivate for 2-3 days in the dark to allow T-DNA transfer.

- Selection and Regeneration:

- Transfer the co-cultivated explants to selection media containing the appropriate antibiotic (e.g., hygromycin) to inhibit Agrobacterium growth and select for transformed plant cells.

- Subsequently, transfer putative transgenic calli to regeneration media to induce shoot and root formation.

- Transplanting: Acclimatize regenerated plantlets (T0 generation) to soil in a controlled greenhouse environment.

Basic Protocol 3: Genotyping of Edited Events

This protocol identifies and characterizes mutations in regenerated plants [1].

- DNA Extraction: Extract genomic DNA from leaf tissue of wild-type and T0 regenerated plants using a reliable in-house or commercial kit.

- PCR Amplification: Perform PCR using the pre-validated primers flanking the target site to generate an amplicon.

- Mutation Detection:

- Restriction Enzyme (RE) Assay: If the CRISPR cut site disrupts a native restriction enzyme recognition sequence, digest the PCR product and analyze fragments by gel electrophoresis. The loss of the restriction site indicates a potential mutation.

- Sanger Sequencing: Clone the PCR amplicon into a sequencing vector or sequence the PCR product directly. Direct sequencing of a heterogeneous PCR product will show overlapping chromatograms after the cut site, indicating editing. Cloning and sequencing multiple colonies reveals the spectrum of specific indel mutations in an individual.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): For a high-throughput and quantitative analysis of editing efficiency and mutation patterns, use amplicon sequencing (Amplicon-Seq) [6].

- Transgene Segregation: Advance heterozygous or biallelic T0 mutants to the T1 generation. Screen T1 plants for the desired mutation while testing for the absence of the Cas9/sgRNA transgene to identify transgene-free edited lines [2] [7].

Advanced Delivery Methods: Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes

To avoid the integration of foreign DNA and streamline regulatory approval, direct delivery of pre-assembled Cas9 protein and sgRNA complexes (RNPs) is a highly effective strategy.

- Biolistic RNP Delivery: As demonstrated in maize, RNP complexes can be coated onto gold microparticles and delivered into embryo cells using a gene gun [8]. This method successfully produced mutants with high frequency and significantly reduced off-target effects compared to DNA delivery.

- Sonication-Assisted Whisker Method: A recent innovation in rice uses potassium titanate whiskers and sonication to introduce RNPs into embryonic cell suspensions [6]. This method achieved efficient mutagenesis, with a dominant 1-bp insertion pattern, and allowed for the regeneration of edited plants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below catalogs key materials and reagents required for executing a CRISPR/Cas9 project in monocot plants.

| Item Category | Specific Examples & Details | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), codon-optimized for monocots [4] | Creates double-stranded breaks at target DNA loci. |

| sgRNA Promoters | Monocot-specific RNA Pol III promoters (e.g., OsU3, OsU6a/b/c for rice; ZmU6 for maize) [4] | Drives high-level, constitutive expression of the guide RNA. |

| Cas9 Promoters | Strong constitutive RNA Pol II promoters (e.g., Maize Ubiquitin 1 (ZmUbi1), CaMV 35S) [2] [4] | Drives high-level expression of the Cas9 protein. |

| Selection Markers | Hygromycin phosphotransferase (Hpt), bar gene (phosphinothricin resistance) [4] | Selects for plant cells that have integrated the T-DNA. |

| Delivery Vectors | Binary T-DNA vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation [1] [4] | Delivers Cas9 and sgRNA genetic components into the plant genome. |

| Web-Based Tools | CRISPR-P 2.0, CHOPCHOP, Cas-Designer, WheatCRISPR [1] | Assists in sgRNA design, efficiency prediction, and off-target analysis. |

Quantitative Data from Case Studies in Rice and Maize

The following table summarizes key performance metrics from published CRISPR/Cas9 studies in rice and maize, illustrating the technology's efficiency.

| Crop Species | Target Gene / Trait | Editing Efficiency / Mutation Rate | Key Outcome and Impact | Citation Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice | An-1 (Grain Number) [7] | 17 multi-allelic, 7 bi-allelic, 4 mono-allelic mutants from 312 T0 plants | T4 mutants showed 35.25% increased single plant yield, 34.8% more spikelets per panicle. | [7] |

| Rice | LKR/SDH (Lysine Content) [9] | 19 transgene-positive T0 plants with knockouts | T2 seeds had a ~2-fold increase in lysine content without affecting agronomic traits. | [9] |

| Maize | LIG, MS26, MS45 (Development & Fertility) [8] | 2.4% to 9.7% mutation frequency (DNA-free RNP delivery) | Recovered transgene-free, mutant plants at high frequency, reducing off-target effects. | [8] |

| Rice | OsPDS (Carotenoid Pathway) [6] | 9 out of 22 selected calli (41%) with RNP delivery via whisker method | Successfully isolated genome-edited lines with albino phenotype, confirming RNP activity. | [6] |

Why CRISPR-Cas9 Outperforms ZFNs and TALENs in Rice and Maize

The advent of genome editing technologies has revolutionized genetic engineering in agriculture, offering unprecedented precision in crop improvement. Among these technologies, Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)-associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) has emerged as the most transformative tool for monocot plants like rice and maize. While earlier technologies such as Zinc-Finger Nucleases (ZFNs) and Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs) paved the way for targeted genome editing, CRISPR/Cas9 demonstrates distinct advantages in simplicity, efficiency, and versatility [10] [11]. This article examines the technical and practical reasons why CRISPR/Cas9 outperforms its predecessors in rice and maize research, providing detailed protocols and application notes for researchers leveraging this technology in monocot crop improvement.

Comparative Analysis of Genome Editing Technologies

Fundamental Mechanisms and Design Complexities

ZFNs are fusion proteins composed of a DNA-binding domain—engineered from Cys2-His2 zinc-finger proteins that typically recognize 3-base pair sequences—and the FokI cleavage domain. A significant limitation is that FokI requires dimerization to become active, necessitating the design and optimization of two separate ZFN proteins that bind to opposite DNA strands with correct orientation and spacing (typically 5-7 bp apart) [10] [11]. The context-dependent DNA recognition of zinc fingers complicates design, as individual fingers can influence neighboring binding specificity. Although methods like oligomerized pool engineering (OPEN) and context-dependent assembly (CoDA) have been developed to address these challenges, the protein engineering process remains time-consuming and expensive [10] [11].

TALENs improved upon ZFNs by offering a more straightforward DNA recognition code. Each TALE repeat domain recognizes a single base pair through two hypervariable amino acids known as repeat-variable diresidues (RVDs). The recognition code is simple: NI for adenine, NG for thymine, HD for cytosine, and NN for guanine/adenine [10]. Despite this simpler code, TALEN assembly is technically challenging due to the highly repetitive nature of TALE sequences, which can lead to recombination events in bacterial systems. Like ZFNs, TALENs also utilize the FokI nuclease domain, requiring paired binding sites with proper spacing for effective cleavage [10].

CRISPR/Cas9 represents a paradigm shift from protein-based to RNA-guided DNA recognition. The system consists of two fundamental components: the Cas9 nuclease and a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) that combines the functions of CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) [12] [13]. The sgRNA contains a 20-nucleotide sequence at its 5' end that specifies the target site through Watson-Crick base pairing, followed by a hairpin structure that facilitates Cas9 binding. Target recognition requires the presence of a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM—NGG for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9) immediately downstream of the target sequence [14]. This RNA-based recognition eliminates the need for complex protein engineering, as designing new target specificities requires only the synthesis of a new sgRNA sequence while the Cas9 protein remains constant.

Quantitative Comparison of Editing Features

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Genome Editing Technologies in Rice and Maize

| Feature | ZFNs | TALENs | CRISPR/Cas9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Recognition Mechanism | Protein-based (3 bp per zinc finger) | Protein-based (1 bp per TALE repeat) | RNA-guided (20 nt sgRNA) |

| Nuclease Domain | FokI (requires dimerization) | FokI (requires dimerization) | Cas9 (single protein) |

| Target Design Complexity | High (context-dependent effects) | Moderate (repetitive cloning challenges) | Low (simple sgRNA design) |

| PAM Requirement | None | None | NGG (for SpCas9) |

| Multiplexing Capacity | Limited | Limited | High (multiple sgRNAs) |

| Editing Efficiency in Monocots | Variable (10-30%) [10] | Moderate (30-60%) [10] | High (60-95%) [14] |

| Time Required for Vector Construction | Several weeks | 1-2 weeks | 3-5 days |

| Relative Cost | High | Moderate | Low |

| Off-Target Effects | Moderate | Low | Moderate (design-dependent) |

| Methylated DNA Targeting | Limited | Limited | Efficient [14] |

Key Advantages of CRISPR/Cas9 in Rice and Maize

Enhanced Efficiency and Specificity: CRISPR/Cas9 demonstrates remarkably higher editing efficiency in both rice and maize compared to ZFNs and TALENs. In maize, transformation efficiency with CRISPR/Cas9 ranges from 60% to 95% in transgenic lines, with a high frequency of biallelic mutations that are heritable [14]. This high efficiency is attributed to the constant expression of the Cas9 protein, which requires only the simple redesign of sgRNAs for new targets. The targeting efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9 is notably better than both TALENs and ZFNs [14].

Streamlined Experimental Workflow: The simplicity of CRISPR/Cas9 design significantly accelerates research timelines. While ZFN and TALEN approaches require complex protein engineering for each new target, CRISPR/Cas9 only requires the synthesis of a new 20-nucleotide sgRNA sequence. This simplification enables researchers to proceed from target selection to transformation in days rather than weeks [14] [10].

Multiplex Editing Capability: CRISPR/Cas9 enables simultaneous editing of multiple genes by introducing several sgRNAs targeting different genomic loci. This capacity is particularly valuable for manipulating complex polygenic traits in rice and maize, such as yield components, stress tolerance, and metabolic pathways. For example, in rice, multiplex editing has been successfully employed to target multiple disease susceptibility genes simultaneously, creating broad-spectrum resistance to pathogens like blast and bacterial blight [2] [15].

Flexibility in Target Selection: Unlike ZFNs, which have constraints in targetable sequences due to the context dependence of zinc fingers, CRISPR/Cas9 can target virtually any genomic sequence followed by a PAM. The requirement for an NGG PAM occurs approximately every 8-12 base pairs in the rice and maize genomes, providing abundant targeting opportunities [14].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for CRISPR/Cas9 Editing in Rice and Maize

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Systems | Maize Ubiquitin promoter-driven Cas9, Rice Ubiquitin promoter-driven Cas9 | Drives constitutive expression of Cas9 nuclease in monocot tissues [14] [2] |

| sgRNA Expression Constructs | Rice U3 and U6 snRNA promoters, Arabidopsis U6 promoters | Polymerase III promoters for high-level sgRNA expression; U6 prefers 'G' start, U3 prefers 'A' start [14] [2] |

| Delivery Vectors | pCAMBIA-based vectors, Golden Gate assembly systems | Modular vector systems enabling efficient cloning of multiple sgRNAs [14] |

| Transformation Systems | Agrobacterium tumefaciens (EHA105, LBA4404), Biolistic delivery | Agrobacterium-mediated transformation is most established; biolistics useful for recalcitrant genotypes [12] |

| Selectable Markers | Hygromycin phosphotransferase (hpt), Herbicide resistance genes | Selection of transformed tissues during regeneration |

| Modular Assembly Systems | Golden Gate MoClo system, Gibson Assembly | Efficient assembly of multiple sgRNA expression cassettes for multiplex editing [14] [2] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Workflow for CRISPR/Cas9 Vector Construction for Monocots

Step-by-Step Protocol for Vector Construction

Step 1: Target Selection and sgRNA Design

- Identify target gene sequence (300-500 bp region surrounding target site)

- Scan for 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequences

- Select 20-nucleotide target sequence immediately 5' to PAM

- Critical Parameter: Optimal GC content: 40-60%

- Verify uniqueness in genome using tools like Cas-OFFinder

- Design sgRNA with G at position 1 if using U6 promoter [14]

Step 2: Oligonucleotide Design and Preparation

- Forward oligo: 5'-GATN20-3' (add appropriate overhang for your vector)

- Reverse oligo: 5'-AAACN20-3' (reverse complement with overhang)

- Phosphorylate and anneal oligonucleotides

- Recipe: 1 μL each oligo (100 μM), 1 μL T4 Ligase Buffer, 6.5 μL dH2O, 0.5 μL T4 PNK

- Annealing program: 37°C 30 min; 95°C 5 min; ramp to 25°C at 5°C/min [14]

Step 3: Golden Gate Assembly

- Set up reaction: 50-100 ng backbone vector, 1:3 molar ratio of insert, 1 μL BsaI, 1 μL T7 Ligase, 2 μL 10x T4 Ligase Buffer, up to 20 μL dH2O

- Cycling parameters: 25 cycles of (37°C 5 min; 16°C 10 min); 50°C 5 min; 80°C 5 min

- Transform into competent E. coli cells [14] [2]

Step 4: Plasmid Verification

- Screen colonies by colony PCR or restriction digest

- Sequence confirm with U6/T7 promoter primers

- Quality Control: Verify no mutations in Cas9 and sgRNA scaffold regions

Rice Transformation Protocol Using Agrobacterium

Materials:

- Rice cultivars: Nipponbare (japonica) or Kasalath (indica)

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105

- Callus induction medium: N6 salts, 2,4-D (2 mg/L), CHU (N6) vitamins

- Co-cultivation medium: N6 salts, 2,4-D (2 mg/L), acetosyringone (100 μM)

- Selection medium: Hygromycin (50 mg/L) or appropriate selection agent

Procedure:

- Callus Induction: Dehush mature seeds, surface sterilize, place on callus induction medium. Incubate at 26°C in dark for 2-3 weeks.

- Agrobacterium Preparation: Inoculate 10 mL YEP with antibiotics, grow overnight at 28°C with shaking. Centrifuge and resuspend in AAM medium to OD600 = 0.1-0.2, add acetosyringone (100 μM).

- Co-cultivation: Immerse calli in Agrobacterium suspension for 30 min, blot dry, transfer to co-cultivation medium. Incubate at 26°C in dark for 3 days.

- Selection: Transfer calli to selection medium containing antibiotics and selection agent. Subculture every 2 weeks.

- Regeneration: Transfer embryogenic calli to regeneration medium (MS salts, BAP 3 mg/L, NAA 0.5 mg/L). Incubate at 26°C with 16h light/8h dark cycle.

- Rooting: Transfer shoots to rooting medium (½ MS salts, IAA 1 mg/L).

- Molecular Analysis: Extract genomic DNA from regenerated plants, perform PCR amplification of target region, sequence to verify edits. [15] [16]

Application Notes: Successful CRISPR/Cas9 Editing in Rice and Maize

Disease Resistance Engineering in Rice

Rice Blast Resistance:

- Target Genes: Pi21, Bsr-d1, ERF922

- Strategy: Knockout of susceptibility genes

- Protocol: Design two sgRNAs targeting conserved domains of Pi21. Transform using protocol 4.3.

- Results: Mutant lines showed enhanced resistance to Magnaporthe oryzae without yield penalty [15] [17]

Bacterial Blight Resistance:

- Target Genes: SWEET14 (Os11N3)

- Strategy: Disrupt effector binding elements in promoter region

- Protocol: Use dual sgRNAs to create promoter deletions

- Results: Edited lines showed reduced susceptibility to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae [15] [17]

Maize Quality and Yield Improvement

Low Cadmium Accumulation:

- Target Gene: OsNramp5 metal transporter

- Strategy: Complete gene knockout

- Protocol: Single sgRNA targeting second exon

- Results: Mutant lines showed significantly reduced cadmium accumulation without affecting yield [18]

Yield Enhancement:

- Target Genes: OsHXK1, CLE family genes

- Strategy: Promoter editing and gene knockout

- Protocol: Multiplex editing with three sgRNAs

- Results: Edited lines showed improved photosynthesis and yield traits [18]

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Low Editing Efficiency:

- Verify sgRNA expression with Northern blot or RT-PCR

- Test multiple sgRNAs for each target

- Optimize promoter combinations (Ubiquitin for Cas9, U3/U6 for sgRNA)

- Ensure proper PAM recognition and GC content [14]

Off-Target Effects:

- Use computational tools to predict potential off-target sites

- Design sgRNAs with minimal similarity to other genomic regions

- Utilize high-fidelity Cas9 variants

- Perform whole-genome sequencing to verify specificity [13]

No Transformants Recovered:

- Verify vector integrity by restriction digest and sequencing

- Optimize Agrobacterium strain and density

- Test different rice/maize genotypes

- Ensure proper selection agent concentration [14] [15]

CRISPR/Cas9 has unequivocally surpassed ZFNs and TALENs as the genome editing technology of choice for rice and maize research due to its superior efficiency, simplicity, multiplexing capability, and flexibility. The RNA-guided DNA recognition mechanism eliminates the complex protein engineering requirements of earlier technologies, significantly accelerating research timelines and reducing costs. As CRISPR technology continues to evolve with developments like base editing, prime editing, and novel Cas variants, its applications in monocot crop improvement will expand further. The protocols and application notes provided here offer researchers a comprehensive framework for implementing CRISPR/Cas9 editing in rice and maize, enabling rapid genetic gains for enhanced crop productivity and sustainability.

The CRISPR-Cas system has emerged as a revolutionary technology for precise genome editing in monocot plants, enabling targeted modifications to improve agronomic traits, enhance nutritional quality, and boost climate resilience [1]. At the heart of this technology lie three fundamental components: Cas proteins that function as molecular scissors, guide RNAs (gRNAs) that provide targeting specificity, and protospacer adjacent motifs (PAMs) that define targetable genomic locations [19]. Understanding the intricate relationship between these components is essential for designing effective genome editing experiments in cereal crops such as rice and maize. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of these key elements within the context of developing robust CRISPR-Cas9 protocols for monocot plant research, offering practical guidance for researchers and scientists engaged in crop improvement and functional genomics.

Cas Proteins: The Genome Editing Effectors

Cas proteins are RNA-guided DNA endonucleases derived from microbial adaptive immune systems that create double-strand breaks (DSBs) at specific genomic locations [1]. These proteins have been repurposed as programmable nucleases for genome engineering, with different Cas variants offering distinct properties, PAM requirements, and editing capabilities.

Table 1: Key Cas Protein Variants and Their Properties for Plant Genome Editing

| Cas Variant | Origin | PAM Requirement | Size (aa) | Key Features | Applications in Monocots |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | 5'-NGG-3' | 1368 | High efficiency, widely validated | Gene knockout in rice, maize [20] |

| StCas9 | Streptococcus thermophilus | 5'-NNAGAAW-3' | 1121 | Alternative PAM recognition | Expanded targeting range [1] |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | 5'-NNGRRT-3' | 1053 | Smaller size for viral delivery | In plant systems requiring compact editors [1] |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) | Acidaminococcus sp. | 5'-TTTV-3' | 1307 | T-rich PAM, staggered cuts | Rice, maize genome editing [21] |

| OpenCRISPR-1 | AI-designed | Engineered specificity | N/A | Reduced off-target effects | High-fidelity editing [22] |

For monocot plants, the Cas9 gene is typically codon-optimized for the target species and expressed under the control of strong constitutive promoters such as maize Ubiquitin 1 (ZmUbi1) or rice ACTIN 1 to achieve high expression levels [20]. The addition of nuclear localization signals (NLS) ensures proper targeting of the Cas protein to the nucleus, which is essential for efficient genome editing [20]. Recent advances include the development of Cas9 orthologs with divergent PAM specificities, such as StCas9, NmCas9, SaCas9, and CjCas9, which recognize different PAM sequences and thereby expand the targeting range of CRISPR systems [1]. More recently, the SpG and SpRY variants have been developed, which operate without strict PAM constraints, greatly enhancing the flexibility and resolution of genome editing [1].

Artificial intelligence has further expanded the Cas protein toolbox through designed editors such as OpenCRISPR-1, which exhibits comparable or improved activity and specificity relative to SpCas9 while being 400 mutations away in sequence [22]. These AI-generated editors represent a significant advancement in overcoming the limitations of natural Cas proteins.

gRNA Design: Principles and Strategies for High Efficiency

The guide RNA is a programmable RNA molecule that directs the Cas protein to specific DNA target sequences. It consists of a 20-nucleotide spacer sequence that is complementary to the target DNA and a structural scaffold that facilitates Cas protein binding [1]. Proper gRNA design is critical for editing efficiency and specificity in monocot plants.

Key Considerations for gRNA Design

- GC Content: Target sequences with GC contents higher than 50% demonstrate higher genome-editing efficiencies (88.5–89.6%) compared to those with GC contents lower than 50% (77.2% efficiency) in rice [20].

- Avoidance of successive T's: Sequences containing successive thymine bases (TTTT) should be avoided when sgRNA expression is driven by U3 or U6 promoters as they can function as termination signals [20].

- Seed region positioning: The PAM-proximal 10-12 nucleotides form a "seed region" where mismatches are least tolerated, making this region critical for target specificity [19].

- Off-target potential: gRNAs should be designed to minimize similarity to other genomic regions, ideally differing by at least three mismatches, with at least one mismatch occurring in the PAM-proximal region [23].

Computational Tools for gRNA Design

Several web-based tools are available to assist researchers in designing highly specific gRNAs for monocot plants. These tools leverage reference genomes to identify potential off-target sites and recommend optimal target sequences.

Table 2: Computational Tools for gRNA Design and Their Applications in Cereal Crops

| Tool Name | Web Address | Supported Crops | Key Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas-Designer | https://www.rgenome.net/cas-designer/ | Rice, maize, wheat, sorghum, barley | gRNA selection and off-target analysis | [1] |

| CRISPR-P 2.0 | http://cbi.hzau.edu.cn/cgi-bin/CRISPR2/CRISPR | Rice, maize, wheat, sorghum | gRNA selection, sgRNA secondary structure prediction | [1] |

| CHOPCHOP | https://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/ | Rice, maize, wheat, sorghum | sgRNA scanning for on-target and off-target sites | [1] |

| WheatCRISPR | https://crispr.bioinfo.nrc.ca/ | Wheat | On-target and low off-target activity prediction | [1] |

| CRISPR-Cereal | http://crispr.hzau.edu.cn/CRISPR-Cereal/ | Rice, maize, wheat | sgRNA scanning for on-target and off-target sites | [1] |

It is important to note that sgRNA designing and off-target screening tools are typically based on specific reference genome crop varieties. For maize, the widely used inbred line B73 serves as the reference genome, and there may be sequence differences between the reference and target cultivars [1]. Therefore, validating the target DNA sequence before finalizing sgRNA targets is recommended.

PAM Requirements: The Targeting Constraint

The protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) is a short, specific DNA sequence (typically 2-6 nucleotides) that must be present immediately adjacent to the target sequence for Cas protein recognition and cleavage [1]. Biologically, PAM sequences are vital for the prokaryotic immune system to discriminate between the chromosomal CRISPR locus and viral DNA, thereby preventing autoimmunity [19].

Different Cas proteins recognize distinct PAM sequences, which fundamentally constrains their targeting range. For example, the most commonly used SpCas9 requires a 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequence, where "N" can be any nucleotide [1]. This requirement means that, on average, a potential SpCas9 target site occurs once every 8-12 base pairs in the genome. The development of Cas variants with altered PAM specificities has significantly expanded the targeting space available for genome editing.

PAM Engineering Strategies

Several approaches have been developed to overcome PAM limitations:

- PAM generation/degeneration: For diagnostic applications, SNV-related generation or degeneration of PAMs can be used to discriminate between single nucleotide differences [19]. PAM generation occurs when a single nucleotide variant (SNV) results in the introduction of a PAM sequence, enabling CRISPR-based detection only when the target sequence harbors that specific mutation.

- Engineered Cas variants: Cas9 engineers have developed proteins such as SpG (recognizing NG PAMs) and SpRY (recognizing NRN and to a lesser extent NYN PAMs, where R is A/G and Y is C/T) with relaxed PAM requirements [1].

- AI-designed editors: Protein language models have been used to generate novel Cas proteins with diverse PAM specificities beyond those found in nature [22].

Experimental Protocol: A Workflow for Monocot Genome Editing

The following protocol outlines a comprehensive workflow for implementing CRISPR-Cas genome editing in monocot plants, integrating the key components discussed in this application note.

Step-by-Step Protocol

gRNA Target Selection and Design (Basic Protocol 1)

- Identify target gene sequence: Extract the genomic sequence of the target gene from the appropriate database (e.g., Phytozome for monocots), noting any sequence variations in your specific cultivar.

- Scan for potential target sites: Use computational tools (Table 2) to identify 20-nucleotide target sequences followed by an appropriate PAM (NGG for SpCas9).

- Evaluate target candidates: Select targets with GC content >50%, avoid successive T's, and ensure the seed region (PAM-proximal 10-12 nt) is unique in the genome.

- Check for off-target sites: Use Cas-OFFinder or similar tools to identify potential off-target sites with up to 5 mismatches, giving particular attention to sites with fewer than 3 mismatches total or fewer than 2 mismatches in the seed region [23].

- Design validation primers: Design PCR primers flanking the target site (amplicon size 300-500 bp) for subsequent genotyping analysis.

Construction of Binary Plasmid Vector (Basic Protocol 2)

- Select backbone vector: Choose a binary vector suitable for plant transformation (e.g., pCAMBIA or pGreen-based vectors) [24].

- Clone Cas9 expression cassette: Insert the codon-optimized Cas9 gene under the control of a strong monocot promoter (e.g., ZmUbi1 for maize, OsActin1 for rice).

- Clone gRNA expression cassette: Insert the sgRNA sequence under the control of a Pol III promoter (e.g., OsU6 for rice, TaU3 for wheat) [20] [24].

- For multiplex editing: Assemble multiple gRNA expression cassettes using tRNA or ribozyme-based processing systems [20].

- Verify construct by sequencing: Confirm the integrity of all components, especially the sgRNA spacer sequence.

Plant Transformation and Genotyping (Basic Protocol 3)

- Deliver constructs: Use Agrobacterium-mediated transformation or particle bombardment to introduce the CRISPR construct into plant cells [1].

- Regenerate plants: Select transformed plants using appropriate antibiotics (e.g., hygromycin when using Hpt selection marker) and regenerate whole plants through tissue culture [20].

- Extract genomic DNA: Use a reliable DNA extraction protocol to obtain high-quality genomic DNA from transformed plants [1].

- Screen for edits: Amplify the target region by PCR and analyze for indels using restriction enzyme digestion (if the edit disrupts a restriction site) or sequencing.

- Sequence analysis: Use tools like EditR or ICE Analysis to quantify editing efficiency and characterize mutation types [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Monocot CRISPR Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas Expression Systems | Maize-codon optimized Cas9, Human-codon optimized Cas9 | DNA cleavage | Maize-codon optimized Cas9 shows higher efficiency in monocots [24] |

| gRNA Cloning Systems | Golden Gate cloning kits, tRNA-gRNA vectors | gRNA expression | Golden Gate assembly enables efficient multiplexing [25] |

| Promoters for Monocots | ZmUbi1, OsActin1, OsU6, TaU3 | Drive expression of Cas9 and gRNA | OsU6 promoter produces more transcripts than OsU3 in rice [20] |

| Selection Markers | Hpt (hygromycin resistance), Bar (phosphinothricin resistance) | Selection of transformed tissue | Hpt is widely used with ZmUbi1 promoter for monocot selection [20] |

| Delivery Tools | Agrobacterium strains, PEG for protoplasts, Gene gun | Introduction of editing components | Agrobacterium-mediated transformation is most common for stable transformation [20] |

The effective implementation of CRISPR-Cas technology in monocot plants requires careful consideration of the three key components: Cas proteins, gRNA design, and PAM requirements. By selecting appropriate Cas variants with suitable PAM specificities, designing gRNAs with high on-target efficiency and minimal off-target potential, and following optimized experimental protocols, researchers can achieve precise genome editing in cereal crops. The continued development of novel Cas proteins through AI-based design and the refinement of delivery strategies will further enhance the capabilities of genome editing in monocot species, accelerating both basic research and crop improvement efforts.

Application Notes

The development of climate-resilient staple crops is imperative for ensuring global food security in the face of increasing climatic volatility. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has emerged as a powerful tool for rapidly introducing resilience traits into major monocot crops, such as rice and maize, by enabling precise modifications to genes controlling stress responses. Unlike traditional breeding, CRISPR technology facilitates the direct manipulation of elite cultivars without compromising their valuable agronomic backgrounds, offering a faster pathway to climate adaptation [26] [27]. These application notes outline the key experimental findings and provide detailed protocols for implementing these genetic improvements in monocot systems.

A primary application of CRISPR-Cas9 is engineering tolerance to abiotic stresses. Drought resilience, a polygenic trait, can be enhanced by editing transcription factors and other regulatory genes within stress-signaling pathways. Similarly, heavy metal accumulation, a significant food safety concern in contaminated soils, can be mitigated by knocking out specific metal transporter genes [28].

The table below summarizes quantitative data from successful CRISPR-Cas9 interventions in rice and maize for developing climate-resilient traits.

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes of CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Trait Improvement in Monocot Crops

| Crop | Target Trait | Edited Gene(s) | Key Quantitative Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice (TBR225) | Reduced Cadmium (Cd) Accumulation | OsNRAMP5 |

• 78.4-84.5% reduction of Cd in roots• 72.3-83.8% reduction of Cd in shoots• 50.5-66.0% reduction of Cd in grains | [29] |

| Maize | Drought Tolerance | Multiple genes (polygenic) | 5% increased yield under drought stress conditions | [27] |

| Rice | Nutritional Enhancement | Metabolic pathway genes | Sixfold increase in β-carotene content | [27] |

The success of these interventions hinges on robust experimental protocols, from vector design through to the molecular and phenotypic characterization of edited lines, which are detailed in the following section.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Gene Knockout for Reduced Cadmium Accumulation in Rice

This protocol describes a methodology for generating low-cadmium rice lines by knocking out the OsNRAMP5 gene, a major cadmium transporter, in the elite variety TBR225 [29].

I. Materials

- Plant Material: Mature seeds of the rice (Oryza sativa L.) variety TBR225.

- Vector: pCas9/sgRNA-OsNRAMP5 binary vector (e.g., designed as per Anh et al., 2022) [29].

- Bacterial Strain: Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA105.

- Culture Media:

- E. coli: Luria-Bertani (LB) medium with appropriate antibiotics (e.g., Kanamycin).

- A. tumefaciens: YEM medium with antibiotics.

- Callus Induction Medium (CI), Co-cultivation Medium (CC), Selection Medium (SM), Regeneration Medium (RM) [29].

- Cd Treatment Solution: Cadmium chloride (CdCl₂) prepared in deionized water.

II. Methods

Step 1: Vector Construction and Agrobacterium Preparation

- Design sgRNAs to target specific exons of the OsNRAMP5 gene and clone them into the pCas9/sgRNA vector [29].

- Introduce the final binary vector into Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA105 using the heat shock method [29].

- Inoculate a single colony of transformed Agrobacterium in YEM medium with antibiotics and incubate at 28°C with shaking until the OD₆₀₀ reaches ~1.0. Centrifuge and resuspend the bacterial pellet in liquid CC medium supplemented with 100 µM acetosyringone.

Step 2: Rice Transformation and Regeneration

- Callus Induction: Sterilize mature TBR225 seeds and culture on CI medium in the dark at 28°C for 7 days to induce embryogenic calli [29] [30].

- Agrobacterium Co-cultivation: Infect the calli with the prepared Agrobacterium suspension for 15-30 minutes. Blot dry and co-cultivate on solid CC medium with acetosyringone at 28°C in the dark for 3 days [29].

- Selection and Regeneration:

- Transfer the calli to SM containing 30 mg/L hygromycin to select for transformed tissue. Perform multiple selection rounds with subculturing every 10-14 days [29].

- Move resistant, proliferating calli to RM (e.g., MS medium supplemented with 1.0 mg/L NAA, 2.0 mg/L Kinetin, 20% coconut water) to induce shoot formation. Subculture regularly until shoots regenerate [29].

- Transfer developed shoots to root induction medium. Acclimatize well-rooted plantlets (T0 generation) to greenhouse conditions [29].

Step 3: Molecular Analysis of Mutants

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Extract DNA from young leaves of T0 and subsequent generation plants using the CTAB method.

- Mutation Detection: Amplify the target region of the OsNRAMP5 gene by PCR using gene-specific primers. Sequence the PCR products and analyze the chromatograms for insertion/deletion (indel) mutations using alignment software (e.g., TIDE, DECODR) [29].

- Selection of Transgene-Free Lines: Screen T1 generation plants by PCR using primers specific to the HPT (hygromycin resistance) marker gene and the Ubiquitin::Cas9 cassette. Select lines that are homozygous for the OsNRAMP5 mutation but lack the transgenes for further analysis [29].

Step 4: Phenotypic and Agronomic Evaluation

- Cadmium Accumulation Assay: Grow wild-type and mutant lines in pots treated with CdCl₂ solutions (e.g., 0, 30, 300 µM). After 2 months, harvest roots and shoots; harvest grains at maturity. Analyze Cd concentration in tissues using ICP-MS or AAS [29].

- Agronomic Trait Assessment: Under controlled field or greenhouse conditions, compare mutant and wild-type lines for key traits: growth duration, plant height, tiller number, grain yield, and amylose content to ensure no yield penalties [29].

- Micronutrient Analysis: Measure the concentration of essential micronutrients like Iron (Fe) and Zinc (Zn) in grains to confirm that the mutation does not adversely affect nutritional quality [29].

Protocol 2: A Workflow for Developing Drought-Tolerant Cereal Crops

This protocol provides a generalized framework for improving drought tolerance in maize and other cereals, a complex trait that often requires multiplexed editing.

I. Materials

- Plant Material: Immature embryos or other explants from the target cereal crop.

- Vectors: CRISPR-Cas9 vectors suitable for multiplex editing (e.g., using a polycistronic tRNA-gRNA system or multiple single-guRNA vectors).

- Target Genes: Candidates such as AREB1 (ABF2), ERF1, RD26, HSFA2, and other drought-responsive transcription factors [28].

II. Methods

Step 1: Target Identification and Vector Design

- Identify key drought-responsive genes and their promoter regions via literature review and transcriptomic data (e.g., from studies on hierarchical co-expression networks under stress) [28].

- Design multiple sgRNAs targeting several key genes or regulatory nodes simultaneously. Clone these into an appropriate multiplex CRISPR-Cas9 system.

Step 2: Plant Transformation and Line Selection

- Transform the target cereal (e.g., maize) using established Agrobacterium-mediated or biolistic methods for the species.

- Generate T0 plants and advance to the T1/T2 generations to obtain homozygous, stable mutants.

Step 3: Phenotypic Screening for Drought Tolerance

- Controlled Stress Assays: Subject edited and wild-type plants to well-watered and water-deficit conditions. Monitor physiological parameters: relative water content, stomatal conductance, and photosynthetic efficiency [28].

- Field Evaluation: Conduct multi-location field trials to assess yield performance under natural drought conditions [27].

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for developing climate-resilient staples, from gene discovery to field evaluation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential reagents and their applications for CRISPR-based improvement of monocot crops.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Experiments in Monocots

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Vector System | Delivers Cas9 and sgRNA into plant cells. | Binary vector with plant codon-optimized Cas9 (e.g., pCas9/sgRNA-OsNRAMP5); contains plant selectable marker (e.g., HPT for hygromycin resistance) [29]. |

| sgRNA | Guides Cas9 nuclease to the specific target DNA sequence. | Designed to have high on-target activity and minimal off-target effects; typically 20 nt target-specific sequence [29]. |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | Mediates transfer of T-DNA containing CRISPR construct into plant genome. | Strain EHA105; cultured in YEM medium with antibiotics and acetosyringone [29]. |

| Callus Induction Medium | Induces formation of embryogenic calli from explants for transformation. | N6 or MS-based medium with 2,4-D; for mature rice seeds [29] [30]. |

| Selection Antibiotic | Selects for plant cells that have integrated the T-DNA. | Hygromycin B (30-50 mg/L for rice); geneticin (G418) is also commonly used. |

| Acetosyringone | Phenolic compound that induces Agrobacterium virulence genes during co-cultivation. | Used at 100-200 µM in co-cultivation medium to enhance transformation efficiency [29]. |

| PCR & Sequencing Primers | For genotyping to confirm gene edits and identify transgene-free lines. | • Target site-specific primers• HPT-specific primers• Cas9-specific primers• Endogenous control primers (e.g., OsActin) [29]. |

The following diagram maps the logical relationship between a climate stress, the plant's molecular response, and the corresponding CRISPR intervention strategy.

Step-by-Step Protocols for Efficient Editing and Multiplexing in Rice and Maize

In CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing for monocot plants like rice and maize, the strategic selection of promoters for expressing the Cas nuclease and guide RNAs (gRNAs), combined with the precise design of the gRNAs themselves, is a fundamental determinant of editing success. These choices directly impact transformation efficiency, editing specificity, and the potential for off-target effects. This application note provides a detailed protocol for constructing high-efficiency CRISPR vectors tailored for rice and maize, framed within the context of optimizing these core components. It consolidates current best practices and experimental data to guide researchers in making informed decisions during vector design.

Promoter Selection for Cas9 and gRNA Expression

The choice of promoter is critical for driving robust and controlled expression of the Cas nuclease and gRNAs. Constitutive, tissue-specific, and endogenous promoters each offer distinct advantages.

Constitutive and Ubiquitous Promoters

Constitutive promoters are widely used for their strong, consistent expression across most plant tissues. The table below summarizes the performance of commonly used and novel promoters in rice and maize.

Table 1: Promoter Performance in Monocot Genome Editing

| Promoter Name | Origin/Type | Target Crop | Expression Pattern | Editing Efficiency & Notes | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zm.UbqM1 | Maize Ubiquitin | Maize | Constitutive | Drives strong Cas9 expression; standard for maize transformation. | [31] |

| CaMV 35S | Cauliflower Mosaic Virus | Rice | Constitutive | Common but may lead to ectopic expression and off-target effects. | [32] |

| OsRPS5-H1 | Rice Ribosomal Protein | Rice | Strong activity in meristematic/embryonic tissues | ~50% albino phenotype when targeting OsPDS; comparable or superior to 35S/Ubi. | [32] |

| OsRPS5-H2 | Rice Ribosomal Protein | Rice | Strong activity in meristematic/embryonic tissues | Lower activity than OsRPS5-H1, but still functional. | [32] |

| Computational Pol III | Computationally Derived (U6/U3) | Maize | gRNA expression | 27 of 37 novel promoters performed similarly to endogenous U6 control. | [31] |

Application Note: For Cas9 expression, the maize ubiquitin promoter (Zm.UbqM1) is a robust choice in maize [31], while the OsRPS5 promoters present a potent alternative to the 35S promoter in rice, potentially reducing off-target effects while maintaining high efficiency [32]. For gRNA expression, the use of endogenous RNA Polymerase III (Pol III) promoters like U6 and U3 is standard. Recent advances show that computationally derived Pol III promoters can significantly expand the toolkit for multiplex editing in maize, allowing simultaneous targeting of up to 27 unique sites in a single plant by avoiding recombination between identical sequences [31].

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Promoter Efficiency in Rice Protoplasts

This protocol is adapted from studies testing the efficacy of novel promoters, such as OsRPS5, using a transient expression system in rice protoplasts [32].

Materials:

- Plasmid Constructs: Reporter vector (e.g.,

proOsRPS5-H1:GFP,proOsRPS5-H2:GFP) and positive/negative control vectors. - Rice Protoplasts: Isolated from embryogenic callus or suspension cells.

- Enzyme Solution: For cell wall digestion (e.g., Cellulase RS, Macerozyme R-10).

- MMg Solution: (0.4 M mannitol, 15 mM MgCl₂, 4 mM MES, pH 5.7).

- PEG Solution: (40% PEG 4000, 0.2 M mannitol, 0.1 M CaCl₂).

- WI Solution: (0.5 M mannitol, 20 mM KCl, 4 mM MES, pH 5.7).

Procedure:

- Protoplast Isolation: Incubate finely chopped rice callus in enzyme solution for 6-8 hours in the dark with gentle shaking. Filter the digest through a nylon mesh (40-75 μm) and collect protoplasts by centrifugation.

- Transfection: a. Aliquot ~2 x 10⁵ protoplasts per transformation. b. Add 10-20 μg of plasmid DNA to the protoplast pellet. c. Add an equal volume of PEG solution, mix gently, and incubate at room temperature for 15-20 minutes. d. Stop the reaction by adding 3-4 volumes of WI solution. e. Wash the protoplasts once with WI solution and resuspend in a suitable culture medium.

- Incubation and Analysis: Incubate transfected protoplasts in the dark for 16-48 hours.

- For GFP reporter assays, observe GFP fluorescence using a fluorescence microscope. The relative fluorescence intensity indicates promoter strength [32].

- For editing efficiency, extract genomic DNA from protoplasts after 48 hours. Amplify the target region by PCR and analyze indel formation by amplicon sequencing or the T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) assay.

Guide RNA (gRNA) Design and Selection

The design of the gRNA is paramount for ensuring high on-target activity and minimizing off-target effects.

Principles for Optimal gRNA Design

- Target Site Selection: The 20-nucleotide spacer sequence must be unique to the target gene and immediately precede a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM). For the commonly used Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), the PAM is 5'-NGG-3' [1].

- Efficiency Prediction: gRNA efficiency can be predicted using web-based tools that consider factors like GC content, nucleotide composition, and position-specific scoring matrices [1].

- Off-Target Assessment: It is critical to check the entire genome for sequences with high similarity to the chosen gRNA, especially those with 1-3 mismatches and a valid PAM. Mismatches in the "seed region" (8-12 bases proximal to the PAM) are generally more disruptive to off-target binding [1].

Computational Tools for gRNA Design in Cereals

Several bioinformatics tools are specifically tailored for cereal crops, which often have large, complex genomes.

Table 2: Bioinformatics Tools for gRNA Design and Analysis in Cereal Crops

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Supported Cereal Crops | Key Feature | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-P 2.0 | gRNA selection & designing | Rice, Maize, Wheat, Sorghum | Includes sgRNA secondary structure prediction. | [1] |

| CRISPOR | gRNA designing, efficiency prediction, off-target analysis | Rice, Maize, Wheat, Sorghum, Barley | Comprehensive tool with multiple genome support. | [1] |

| CHOPCHOP | gRNA scanning for on/off-target sites | Rice, Maize, Wheat, Sorghum | User-friendly web interface. | [1] |

| CRISPR-Cereal | gRNA scanning for on/off-target sites | Rice, Maize, Wheat | Specifically designed for cereal crops. | [1] |

| Cas-OFFinder | Off-target analysis | Rice, Maize, Wheat, Sorghum, Barley | Specialized for exhaustive off-target search. | [1] |

Application Note: Before finalizing a gRNA, it is highly recommended to validate the target DNA sequence in the specific cultivar being used. Differences between the reference genome (e.g., B73 for maize) and the target cultivar can lead to failed editing. This is done by designing flanking PCR primers, amplifying the genomic region from the cultivar, and confirming the sequence via Sanger sequencing [1].

Experimental Protocol: gRNA Validation and Genotyping Edited Plants

After vector construction and plant transformation, genotyping is essential to confirm successful gene editing.

Materials:

- Plant Genomic DNA: Extracted from wild-type and putative edited lines.

- PCR Reagents: Taq polymerase, dNTPs, primers flanking the target site.

- Gel Electrophoresis Equipment.

- T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) or equivalent surveyor nuclease.

- Sanger Sequencing or High-Throughput Sequencing facilities.

Procedure [33]:

- DNA Extraction: Use a reliable protocol (e.g., CTAB method) to extract high-quality genomic DNA from leaf tissue.

- PCR Amplification: Design primers that amplify a 400-800 bp fragment surrounding the gRNA target site. Perform a standard PCR protocol.

- Mutation Detection:

- T7 Endonuclease I (T7EI) Assay: a. Denature and reanneal the PCR products to form heteroduplex DNA if indels are present. b. Digest the heteroduplex DNA with T7EI enzyme, which cleaves at mismatched sites. c. Analyze the products on an agarose gel. Cleaved bands indicate successful mutation.

- Restriction Enzyme (RE) Digestion: If the edit is designed to create or destroy a restriction site, digest the PCR product with the corresponding RE and analyze the fragment pattern on a gel.

- High-Resolution Analysis:

- Sanger Sequencing: Clone the PCR amplicons and sequence multiple clones, or directly sequence the PCR product to decipher heterogeneous edits.

- High-Throughput Sequencing: For a comprehensive and quantitative view of all mutation types and their frequencies, sequence the PCR amplicons using next-generation sequencing (NGS). This is the gold standard for characterizing edited lines [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Vector Construction in Monocots

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Vector | Source of Cas9 nuclease | Vectors with maize Ubiquitin (Zm.UbqM1) or rice OsRPS5 promoters. |

| gRNA Cloning Vector | Backbone for gRNA insertion | Vectors like pRGEB32 using OsU3 or OsU6 promoters [34]. |

| Web-Based gRNA Design Tools | In-silico gRNA selection & off-target scoring | CRISPR-P 2.0, CRISPOR, CRISPR-Cereal [1]. |

| Pol III Promoters | Drive gRNA expression | Use diverse, computationally derived U6/U3 promoters for multiplexing in maize [31]. |

| Gateway Cloning System | Modular assembly of multigene constructs | Efficiently assemble CRISPR vectors with multiple gRNAs [33]. |

| Agrobacterium Strain | Plant transformation | e.g., EHA105, LBA4404 for rice/maize transformation. |

The efficient construction of CRISPR/Cas9 vectors for rice and maize hinges on a synergistic optimization of promoter choice and gRNA design. Employing crop-optimized promoters like OsRPS5 in rice or computationally derived Pol III promoters in maize, alongside rigorous, tool-assisted gRNA selection and validation, provides a robust framework for achieving high-efficiency genome editing. The protocols detailed herein for promoter testing, gRNA validation, and plant genotyping offer a reliable pathway for researchers to generate high-quality edited lines for functional genomics and trait improvement in these vital monocot crops.

Golden Gate Cloning for Assembling Large Multiplex Guide RNA Arrays

The development of CRISPR-Cas9 technologies has revolutionized functional genomics and genetic engineering. In monocot plants such as rice and maize, where transformation remains expensive and tedious, the ability to target multiple genes simultaneously from a single transformation event provides significant practical advantages [35]. Multiplexed guide RNA (gRNA) arrays enable researchers to introduce complex genetic perturbations, edit multiple regulatory elements, and engineer metabolic pathways more efficiently than sequential targeting approaches.

Golden Gate cloning has emerged as a particularly powerful method for assembling these multiplex gRNA arrays. This technique utilizes Type IIS restriction enzymes, which cleave outside their recognition sites, creating unique overhangs that facilitate the ordered, seamless assembly of multiple DNA fragments in a single reaction [36]. The method's insensitivity to tandem repeats makes it ideally suited for constructing the highly repetitive gRNA arrays that challenge traditional cloning methods [35]. Within the Golden Gate ecosystem, the Modular Cloning (MoClo) system provides a standardized, hierarchical framework that is especially well-suited for building large multiplexed Cas9 guide arrays for plant systems [35] [37].

This application note details protocols for using Golden Gate cloning to assemble large multiplex gRNA arrays specifically for CRISPR-Cas9 applications in rice and maize research, complete with detailed methodologies, performance data, and implementation guidelines.

Key Architectural Strategies for gRNA Arrays

The selection of an appropriate genetic architecture for gRNA expression is fundamental to successful multiplex editing. Table 1 compares the primary strategies used in plant systems.

Table 1: Comparison of gRNA Array Expression Architectures

| Architecture | Processing Mechanism | Key Features | Example Capacity | Organisms Demonstrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Pol III Promoters | Independent transcription | High fidelity; avoids processing requirements | Up to 5 guides [38] | Yeast, plants |

| Cas12a-processed Array | Native Cas12a endoribonuclease | Single transcript; self-processing | 5 targets cleaved + 10 regulated [39] | Human cells, plants, yeast, bacteria |

| tRNA-gRNA Array | Endogenous RNase P and Z | Uses endogenous enzymes; no heterologous proteins needed | High (49 guides in rice) [40] | Plants, yeast, bacteria |

| Ribozyme-flanked gRNAs | Hammerhead & HDV ribozymes | Self-cleaving; compatible with Pol II promoters | Variable | Multiple eukaryotes |

| Csy4-processed Array | Heterologous Csy4 endonuclease | Precise cleavage; requires co-expression of Csy4 | 12 sgRNAs [39] | Mammalian cells, yeast, bacteria |

Materials and Reagents

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2 catalogs the key reagents required for implementing Golden Gate assembly of multiplex gRNA arrays.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Golden Gate Assembly of gRNA Arrays

| Item | Function/Role | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes | Digest DNA outside recognition sites to create unique overhangs | BsaI-HFv2 (common for MoClo), BpiI (isoschizomer of BbsI) [35] |

| DNA Ligase | Joins DNA fragments with complementary overhangs | T4 DNA Ligase [35] |

| MoClo Toolkit | Standardized parts for hierarchical assembly | Addgene Kit #1000000044; includes Level 0, 1, and 2 vectors [35] [37] |

| Plant MoClo Parts | Species-specific genetic elements | MoClo Plant Parts Kit (Addgene #1000000047); includes plant promoters, UTRs, CDS, terminators [37] |

| gRNA Scaffold | Constant portion of guide RNA | Various MoClo-compatible sgRNA scaffolds [35] |

| Promoter Parts | Drive gRNA expression | Maize U6, Rice U6, OsU6, ZmU3 promoters [35] |

| Binary Vectors | Final plant transformation vectors | Gateway-compatible vectors with Cas9 (e.g., pMCG1005) [35] |

| High-Fidelity Polymerase | Amplify DNA parts with minimal errors | Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase [35] |

Step-by-Step Assembly Protocol

Step 1: Designing gRNA Spacers and Array Architecture

Begin by designing spacer sequences (typically 20 nt) targeting genomic loci of interest using established gRNA design tools. For promoter editing approaches like High-efficiency Multiplex Promoter-targeting (HMP), design 8 sgRNAs distributed across a 2-kb promoter region to generate a spectrum of mutations [41]. To prevent re-cutting of the array during assembly, ensure no internal BsaI or other Type IIS recognition sites exist within spacer sequences using tools like NEBioCalculator.

Step 2: Creating Level 0 Parts

Level 0 parts constitute the basic building blocks: promoters, spacer sequences, and sgRNA scaffolds. For amplicon-based parts, design primers with appropriate overhangs:

- Forward Primer Structure: 5'-ttGGTCTC[a]GGAG[spacer-specific overhang]-3'

- Reverse Primer Structure: 5'-ttGGTCTC[g]ATGG[spacer-specific overhang]-3'

The lowercase sequences represent the BsaI recognition site (GGTCTC), while bracketed nucleotides determine fusion sites for directional assembly [35].

Step 3: Assembling Level 1 gRNA Expression Units

Assemble the three Level 0 parts (promoter, spacer, and sgRNA scaffold) into a Level 1 vector using Golden Gate reaction:

- 50 ng each Level 0 part

- 50 ng Level 1 acceptor vector

- 1× T4 DNA Ligase Buffer

- 0.5 μL BsaI-HFv2

- 1.0 μL T4 DNA Ligase

- Nuclease-free water to 10 μL

Thermocycling conditions:

- 37°C for 5 minutes (digestion)

- 16°C for 10 minutes (ligation)

- Repeat for 25 cycles

- 50°C for 5 minutes

- 80°C for 10 minutes

Transform into competent E. coli and select with appropriate antibiotics [35].

Step 4: Assembling Level 2 Multiplex Arrays

Assemble multiple Level 1 gRNA units into a Level 2 array using the same Golden Gate principle. The hierarchical nature of MoClo enables theoretically unlimited array size, with demonstrated success for arrays targeting up to 49 loci in rice [40]. Use a destination vector with a different antibiotic resistance than Level 1 vectors for selection.

Step 5: Transfer to Binary Vector and Plant Transformation

For plant transformation, transfer the final Level 2 array into a binary Agrobacterium vector (e.g., pMCG1005) using Gateway LR Clonase recombination [35]. Transform into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA101 and proceed with standard transformation protocols for maize or rice.

Performance Data and Validation

Table 3 summarizes quantitative performance metrics from published implementations of Golden Gate-assembled gRNA arrays in plant systems.

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Golden Gate-Assembled gRNA Arrays in Plants

| Application | Array Size | Editing Efficiency | Key Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice promoter editing (HMP) | 8 sgRNAs targeting Hd1 promoter | 59-88% mutation efficiency per target; 43% of lines had >50 bp deletions | Quantitative variation in heading date (73-107 days) correlated with Hd1 expression | [41] |

| Ultra-multiplex rice genome editing | 49 sgRNAs in single vector | High co-editing efficiency observed | Demonstration of large-scale parallel editing capability | [40] |

| Maize multiplex editing | Variable (protocol focused) | Effective multiplex editing demonstrated | Reliable method for complex array assembly | [35] |

| Yeast BioBrick assembly | 6 gRNAs targeting marker genes | Up to 5 simultaneous perturbations achieved | Alternative assembly method for comparison | [38] |

Applications in Monocot Research

The ability to assemble large gRNA arrays has enabled sophisticated genetic engineering approaches in rice and maize:

Fine-Tuning Agronomic Traits: Promoter editing of heading date genes (Hd1, Ghd7, DTH8) in rice has generated quantitative variation, allowing breeders to precisely adapt flowering time for specific environments [41].

Metabolic Pathway Engineering: Simultaneous targeting of multiple pathway genes enables comprehensive rewiring of metabolic networks without sequential modification.

Genetic Circuit Implementation: Layered gRNA arrays can implement complex logic circuits for sophisticated control of gene expression.

Troubleshooting and Optimization

- Low Assembly Efficiency: Ensure all internal Type IIS sites are eliminated from parts and vectors. Increase cycling numbers (up to 50 cycles) for complex assemblies.

- Array Instability: Use recombination-deficient E. coli strains for propagation. Minimize repetitive sequence homology where possible.

- Variable gRNA Activity: Shuffle different Pol III promoters (maize U6, rice U6 variants) to avoid transcriptional interference [35].

- Low Plant Editing Efficiency: Verify promoter compatibility with target species and optimize gRNA design using species-specific tools.

Golden Gate cloning provides a robust, scalable platform for assembling large multiplex gRNA arrays that significantly enhance CRISPR-Cas9 capabilities in monocot plants. The hierarchical MoClo framework, with its standardized parts and assembly syntax, enables researchers to build complex genetic constructs targeting dozens of loci simultaneously. This protocol outlines a comprehensive approach from initial design to final validation, empowering plant biotechnologists to implement sophisticated multiplex genome editing applications in rice and maize. As CRISPR technologies continue to evolve, Golden Gate assembly remains a cornerstone method for constructing the complex genetic arrays that drive advanced plant synthetic biology and precision breeding.

The application of CRISPR/Cas9 technology in monocot plants, such as rice and maize, represents a frontier in modern crop improvement research. A critical factor determining the success of genome editing initiatives is the efficiency of delivering the CRISPR/Cas9 components into plant cells. For researchers and scientists focused on monocots, the primary delivery strategies have consolidated around Agrobacterium-mediated transformation, biolistic delivery, and the use of pre-assembled Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. Each method presents a unique profile of advantages and limitations concerning editing efficiency, technical complexity, and regulatory outcomes, particularly the generation of transgene-free edited plants. This application note provides a comparative analysis of these three core delivery mechanisms, offering structured protocols and data to inform experimental design in monocot CRISPR/Cas9 research.

Comparative Analysis of Delivery Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages of Agrobacterium, Biolistics, and RNP delivery methods, providing a foundation for selection.

Table 1: Overview of CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery Methods for Monocot Plants

| Delivery Method | Key Features | Typical Editing Efficiency | Major Advantages | Major Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agrobacterium-mediated | T-DNA delivery of Cas9/gRNA expression cassettes [42] [43] | ~10% (Wheat T0) [42]; >70% (Maize T0) [43] | Lower copy number integration; High efficiency in amenable genotypes; Heritable mutations [42] [43] | Limited host range; Requires tissue culture; Integrated transgene [44] |

| Biolistics (DNA) | Physical co-delivery of DNA plasmids [45] | 5.2% (Wheat T0 in planta) [45] | Genotype-independent; Broad applicability; No bacterial vector requirement [46] | Complex integration patterns; Higher off-target potential; Tissue damage [47] [45] |

| RNP Complexes | Direct delivery of pre-assembled Cas9 protein and gRNA [47] [8] | 2.4%-9.7% (Maize T0 DNA-free) [8]; 47% mutant recovery from callus [47] | DNA-free; Minimal off-target effects; Rapid activity; No transgene integration [47] [48] [8] | Technical challenges in delivery; Lower biallelic frequency in some systems [47] [8] |

A crucial consideration in method selection is the potential for generating plants without integrated transgenes. Agrobacterium and biolistic DNA delivery typically result in transgenic T0 plants, though the transgene can be segregated out in subsequent generations [42] [45]. In contrast, RNP delivery, as well as transient expression from biolistic DNA, enables the direct recovery of non-transgenic edited plants [47] [45] [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Agrobacterium-mediated Transformation in Wheat

This protocol is adapted from an established method for generating edited wheat mutants for grain regulatory genes [42].

Key Reagents:

- Binary Vector: Contains a wheat codon-optimized Cas9 driven by a maize ubiquitin promoter and guide RNA(s) driven by wheat U6 promoters (e.g., TaU6.3) [42].

- Agrobacterium tumefaciens Strain: AGL1 or similar, transformed with the binary vector.

- Plant Material: Immature embryos of the wheat cultivar 'Fielder'.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Vector Construction: Clone the specific gRNA sequence(s) targeting your gene of interest into the BsaI site of the binary vector pTagRNA4 [42].

- Agrobacterium Preparation: Culture the transformed Agrobacterium in liquid medium to an OD₆₀₀ of ~0.8. Pellet and resuspend the cells in induction medium.

- Explant Inoculation: Immerse immature wheat embryos in the Agrobacterium suspension for 30 minutes, then co-cultivate on solid medium for 2-3 days.

- Selection and Regeneration: Transfer embryos to selection medium containing antibiotics to suppress Agrobacterium and select for transformed plant cells. Promote callus formation and subsequent shoot regeneration.

- Molecular Analysis: Extract genomic DNA from T0 plant leaves. Use PCR to amplify the target region and sequence the amplicons to identify indel mutations.

Biolistic Delivery of RNP Complexes in Maize

This DNA-free protocol demonstrates high-frequency mutagenesis and reduced off-target effects in maize [47] [8].

Key Reagents:

- Cas9 Protein: Purified S. pyogenes Cas9 protein.

- sgRNA: In vitro transcribed and purified sgRNA targeting the gene of interest.

- Plant Material: Immature maize embryos of genotype Hi-II or B104.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- RNP Complex Assembly: In a tube, combine 5 µg of Cas9 protein with a 2-3 molar excess of sgRNA. Incubate at 25°C for 15 minutes to form the RNP complex [8].

- Particle Preparation: Coat 0.6µm gold microparticles with the pre-assembled RNP complexes. This can be done by precipitating the RNP onto the particles in the presence of spermidine and PEG [47].

- Bombardment: Use a helium-driven gene gun to bombard the RNP-coated particles directly into the scutellar cells of immature maize embryos.

- Regeneration without Selection: Culture the bombarded embryos on plant regeneration medium without selectable agents, leveraging the high editing frequency of RNPs [8].

- Screening: Extract DNA from regenerated plantlets (T0) and screen for mutations at the target locus using sequencing or a mismatch detection assay (e.g., T7E1).

In Planta Biolistic Delivery (Transient Expression) in Wheat

This protocol enables genome editing without the need for callus culture, using transient expression in shoot apical meristems (SAM) [45].

Key Reagents:

- DNA Plasmids: Separate plasmids expressing Cas9 (driven by a maize ubiquitin promoter), the sgRNA, and a GFP reporter gene.

- Plant Material: Mature wheat seeds (e.g., cultivar 'Fielder').

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Seed Preparation: Imbibe mature wheat seeds in water for 16-24 hours. Excise the embryo and carefully make an incision to expose the SAM.

- Particle Coating: Mix the three plasmids (Cas9, sgRNA, GFP) in equimolar ratios and coat onto 0.6-1.0µm gold particles.

- Meristem Bombardment: Bombard the SAM-exposed embryos using a gene gun with specific pressure settings (e.g., 1,550 psi).

- Selection of Transformed Tissues: 24-48 hours post-bombardment, screen embryos for transient GFP expression within the SAM using a fluorescence microscope. Select only GFP-positive embryos for further growth [45].

- Plant Growth and Progeny Screening: Grow selected embryos into mature T0 plants and self-pollinate. Screen the T1 progeny for heritable mutations, as the T0 plants are often chimeric.

Workflow and Decision Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the key decision-making pathway for selecting and implementing a CRISPR/Cas9 delivery method in monocot plants.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of the protocols above requires a suite of specialized reagents. The table below lists key solutions and their critical functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery in Monocots

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Vector | Drives the expression of the Cas9 nuclease in plant cells. | pE(R4-R3)ZmUbiOsCas9ver3 (for maize/rice); uses maize ubiquitin promoter for high expression in monocots [45]. |

| gRNA Cloning Vector | Allows for the insertion and expression of the target-specific guide RNA. | pTagRNA4 (for wheat); contains wheat U6 promoter (e.g., TaU6.3) [42]. |

| Binary Vector (for Agrobacterium) | Plasmid for Agrobacterium containing T-DNA borders for transfer into plant genome. | pLC41 (Japan Tobacco); Gateway-compatible vector for assembling expression cassettes [42]. |

| Purified Cas9 Protein | Essential component for RNP assembly; enables DNA-free editing. | Recombinant S. pyogenes Cas9, often fused with a Nuclear Localization Signal (NLS) [47] [8]. |

| In Vitro Transcription Kit | For synthesis of sgRNA for RNP complex assembly. | Produces sgRNA free of DNA template contamination [47]. |

| Gold Microcarriers (0.6-1.0 µm) | Microprojectiles for biolistic delivery of DNA or RNP complexes. | The size is critical for efficient penetration into plant cells [47] [45]. |

| Plant Hormone Media | For induction of callus and subsequent regeneration of shoots and roots. | Media contain auxins (e.g., 2,4-D) for callogenesis and cytokinins for organogenesis [42] [45]. |

| Selection Agents | To eliminate non-transformed tissues and select for cells with delivered DNA. | Antibiotics (e.g., hygromycin) or herbicides (e.g., bialaphos) coupled with a resistance gene in the delivered DNA [42] [47]. |